This cross-sectional study characterizes otologic disease among participants with primary ciliary dyskinesia from the Ear-Nose-Throat Prospective International Cohort.

Key Points

Question

What are the characteristics of otologic disease among patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD)?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 397 adult and pediatric participants, baseline data from a large multicenter cohort of patients with PCD showed frequent reports of ear pain and reduced hearing, with age as the main factor associated with hearing impairment. Otitis media with effusion was the most common otoscopic finding, and adults often presented with tympanic sclerosis following history of previous ear infections.

Meaning

Because otologic disease is an important yet underreported part of PCD’s clinical expression, otologic assessments should be recommended for all age groups as part of regular clinical follow-up.

Abstract

Importance

Otologic disease is common among people with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), yet little is known about its spectrum and severity.

Objective

To characterize otologic disease among participants with PCD using data from the Ear-Nose-Throat Prospective International Cohort.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional analysis of baseline cohort data from February 2020 through July 2022 included participants from 12 specialized centers in 10 countries. Children and adults with PCD diagnoses; routine ear, nose, and throat examinations; and completed symptom questionnaires at the same visit or within 2 weeks were prospectively included.

Exposures

Potential risk factors associated with increased risk of ear disease.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The prevalence and characteristics of patient-reported otologic symptoms and findings from otologic examinations, including potential factors associated with increased risk of ear inflammation and hearing impairment.

Results

A total of 397 individuals were eligible to participate in this study (median [range] age, 15.2 [0.2-72.4] years; 186 (47%) female). Of the included participants, 204 (51%) reported ear pain, 110 (28%) reported ear discharge, and 183 (46%) reported hearing problems. Adults reported ear pain and hearing problems more frequently when compared with children. Otitis media with effusion—usually bilateral—was the most common otoscopic finding among 121 of 384 (32%) participants. Retracted tympanic membrane and tympanic sclerosis were more commonly seen among adults. Tympanometry was performed for 216 participants and showed pathologic type B results for 114 (53%). Audiometry was performed for 273 participants and showed hearing impairment in at least 1 ear, most commonly mild. Season of visit was the strongest risk factor for problems associated with ear inflammation (autumn vs spring: odds ratio, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.51-3.81) and age 30 years and older for hearing impairment (41-50 years vs ≤10 years: odds ratio, 3.33; 95% CI, 1.12-9.91).

Conclusion and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study, many people with PCD experienced ear problems, yet frequency varied, highlighting disease expression differences and possible clinical phenotypes. Understanding differences in otologic disease expression and progression during lifetime may inform clinical decisions about follow-up and medical care. Multidisciplinary PCD management should be recommended, including regular otologic assessments for all ages, even without specific complaints.

Introduction

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, inherited disease that occurs when pathogenic variants in disease-causing genes affect ciliary structure or function.1 Motile ciliary dysfunction results in a wide range of symptoms from different organ systems.2,3,4,5 Although the clinical phenotype is heterogeneous, PCD most commonly affects upper and lower airways because ciliary motility is crucial for clearing respiratory secretions.6,7,8,9,10 During childhood, many patients with PCD experience recurrent episodes of acute otitis media from defective ciliary function in the eustachian tube and middle ear, which impairs mucociliary clearance and predisposes patients to repeated bacterial infections.11,12 Many patients develop bilateral otitis media with effusion (OME) as the disease progresses, yet the prevalence of OME varies among studies.13,14 In many otherwise healthy children, OME resolves spontaneously by age 8 years but persists beyond this age among children with PCD and needs active management.15,16,17,18,19,20,21 Indeed, recurrent otitis media and OME results in conductive hearing loss.16,22 Developing severe hearing impairment early in life is also complicated by delayed speech-language development.23

Retrospective medical record review studies of children provide the most current knowledge about PCD-associated ear problems; however, test result and symptom records are not standardized.24,25,26 In these studies, acute ear problems appear to improve with age—probably because of eustachian tube anatomical changes and its changing angle with respect to the base of the skull. In an earlier French study, although acute otitis media improved with age, OME reportedly remained frequent among adults and showed no spontaneous improvement.13 Even so, patients with specific ultrastructural defects were reported to have a higher prevalence of recurrent otitis media.13 However, little is known about age-related changes, such as progression of hearing loss during lifetime or risk factors possibly associated with increased frequency of symptoms.13,16

Using data from a large, prospective international cohort, we characterized otologic disease among patients with PCD. Specifically, we describe the prevalence and characteristics of patient-reported otologic symptoms and findings from otologic examinations of children and adults with PCD, and we identify potential factors associated with increased risk of ear disease, specifically ear inflammation and hearing impairment.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We analyzed data from the Ear-Nose-Throat (ENT) Prospective International Cohort of patients with PCD (EPIC-PCD), an observational, multicenter, clinical cohort set up in February 2020 and hosted at the University of Bern in Switzerland27; EPIC-PCD includes clinical information about patients of all ages with PCD diagnosed by European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines and followed at participating centers.28 We excluded patients without at least 1 ENT follow-up visit during a year-long period. For this analysis, we included cross-sectional baseline data from all enrolled participants with clinical examinations by ENT specialists and who completed symptom questionnaires at the same visit or within 2 weeks, with data entered in the study database by July 31, 2022.

Human research ethics committees for all participating centers reviewed and approved EPIC-PCD according to local legislation. We obtained written informed consent or assent in accordance with national data protection laws from participants 14 years or older (with small variations according to local legislation) or from parents or caregivers for younger participants. We report using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.29

Patient-Reported Symptoms

Participants or parents completed the standardized, PCD-specific FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire, which is part of the FOLLOW-PCD data collection form, during participants’ scheduled follow-up visits at participating centers.30 The FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire includes detailed questions about frequency and characteristics of upper and lower respiratory symptoms during the past 3 months as well as health-related behaviors such as active and passive smoking and living environment. There are age-specific questionnaire versions for adults, adolescents aged 14 to 17 years, and parents or caregivers of participants 14 years and younger. The FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire was originally developed in English, German, and Greek, then translated into the languages of participating centers using a standard procedure.

For otologic symptoms, the questionnaire specifically asks about ear pain, ear discharge, and hearing problems. Questions about symptom frequency are based on a 5-point Likert scale: daily, often, sometimes, rarely, and never. We also asked if each reported symptom was unilateral or bilateral and inquired about ENT symptom seasonal variation. We recorded missing answers as “don’t know” or “never” depending on available answer categories for questions.

ENT Examinations

For planned, clinical reasons, regardless of study participation, participants underwent ENT assessments as part of scheduled follow-up visits at participating centers. The ENT specialists assessed ears by otoscopy, tympanometry, and audiometry. We recorded use of hearing aids and presence of tympanostomy tubes. We recorded tympanometry results using the Jerger description of tympanogram type: type A as normal middle ear status; type B perhaps indicative of OME, tympanic perforation, or sclerosis; types AD and AS as increased and decreased membrane mobility, respectively; and type C as evidence of negative pressure in the middle ear—usually signaling retracted membrane.31 We grouped types AD and AS under type A. We recorded audiometry results using type and World Health Organization (WHO) hearing loss grades.32 Because EPIC-PCD is observational, embedded in routine clinical care and management, and follows local procedures and protocols, no additional examinations were performed for the purposes of the study. As a result, some assessments were unavailable for participants. Local ENT specialists determined if tympanometry and audiometry were necessary. Using the ENT module from the FOLLOW-PCD form, ENT examinations were recorded in a standardized way.30 We recorded and present missing information from ENT assessments as missing data.

Medical History and Other Relevant Data

We extracted and recorded detailed diagnostic information and information on situs abnormalities and cardiac defects from medical records at baseline using the corresponding module from FOLLOW-PCD. We entered all data in the study database using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture [Vanderbilt University]) hosted by the Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Bern.33 Definite PCD diagnosis was confirmed by presence of hallmark ultrastructural defects seen in transmission electron microscopy (TEM) or by identification of biallelic pathogenic mutations in PCD genes according to ERS guidelines. Participants with 1 or more of the following were categorized as having probable PCD: (1) abnormal high-speed videomicroscopy analysis findings, (2) nasal nitric oxide value indicative for PCD, (3) nonhallmark defect identified by electron microscopy, (4) pathologic immunofluorescence finding, or (5) genetic findings suggestive of PCD.

Statistical Analysis

We described study population characteristics, prevalence, and frequency of patient-reported symptoms, as well as findings from ENT examinations for the whole cohort and separately for the following age groups: 0 to 6, 7 to 14, 15 to 30, 31 to 50, and older than 50 years. Medians and IQRs were used for continuous variables and numbers and proportions for categorical variables. We compared prevalence and frequency of symptoms and prevalence of clinical findings between males and females and by age using χ2 and t tests and calculated the Cramér V and its biased-corrected 95% CI.

We created 2 composite outcome scores representing ear disease: (1) problems associated with ear inflammation (ear inflammation score) and (2) hearing impairment (hearing score). For the ear inflammation score, we included (1) any reported ear pain or ear discharge, (2) presence of tympanostomy tubes, (3) otitis media, and (4) tympanic perforation during otoscopic examination; we scored each as either 0 (absence) or 1 (presence), and total score ranged from 0 to 4. For the hearing score, we included (1) reported hearing problems (0-4, indicating never to daily) and (2) audiometry results (0-4, indicating normal to profound hearing impairment), with the total score ranging from 0 to 8. We assessed potential factors associated with increased risk of higher ear inflammation or hearing scores using multivariable, ordinal logistic regression models, considering age, age at diagnosis, sex, study center, smoking exposure, season of completed questionnaires, frequency of nasal symptoms reported in questionnaires, and presence of nasal polyps during nasal examinations. We selected factors included in the model based on discussions with clinical specialists and data availability by using directed acyclic graphs. Because age at diagnosis showed strong collinearity with age, we could not include both variables in the main models. We tested if including age at diagnosis instead of age made any difference; because there were no differences, we kept age in the final models. After exploring linear and nonlinear effects of age as a continuous variable, we included age groups at 10-year intervals. Due to sample-size restrictions, we could not include centers in the final analyses. We therefore ran separate models, including study center as the only explanatory variable. As a sensitivity analysis and to test the robustness of findings, we described separately patient-reported ear symptoms and otoscopic examination findings and ran the 2 regression models in the subgroup of patients with definite PCD diagnosis according to the ERS guidelines. Lastly, in a subgroup of participants with TEM results, we repeated both regression models and included only age and ciliary ultrastructural defects to assess if ciliary ultrastructural defect was a risk factor for ear problems. We performed all analyses using Stata, version 15 (StataCorp).

Results

Demographic, Diagnostic, and Medical History Characteristics

Participants in this study represented 12 centers from 10 countries. In total, 505 patients were asked to participate in EPIC-PCD, of whom 448 (89%) agreed and enrolled in the cohort. From data entered in the database by July 31, 2022, 397 were eligible to participate in this study (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). Their median (range) age was 15.2 (0.2-72.4) years, while 218 (55%) were 18 years or older and 186 (47%) were female (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of EPIC-PCD Participants, Overall and by Age Group.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Cramér V (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 397) | Age 0-6 y (n = 44) | Age 7-14 y (n = 130) | Age 15-30 y (n = 157) | Age 31-50 y (n = 43) | Age >50 y (n = 23) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 15 (9-22) | 4 (2-5) | 10 (8-12) | 16 (15-21) | 38 (34-43) | 57 (56-62) | NA |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 186 (47) | 21 (48) | 58 (45) | 76 (48) | 19 (44) | 12 (52) | 0.05 (0.01-0.05) |

| Male | 211 (53) | 23 (52) | 72 (55) | 81 (52) | 24 (56) | 11 (48) | |

| Age of PCD diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 9 (4-17) | 1 (0-2) | 6 (1-8) | 12 (8-17) | 34 (29-36) | 51 (43-55) | NA |

| Laterality defect | |||||||

| Situs inversus totalis | 142 (36) | 25 (57) | 46 (35) | 60 (38) | 7 (16) | 4 (17) | 0.19 (0.11-0.24) |

| Situs ambiguous | 4 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| Situs solitus | 245 (62) | 18 (41) | 82 (63) | 94 (60) | 32 (74) | 19 (83) | |

| Not reported | 6 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 4 (9) | 0 | |

| Cardiovascular malformation | |||||||

| Yes | 34 (9) | 7 (16) | 11 (8) | 14 (9) | 2 (5) | 0 | 0.13 (0.08-0.16) |

| No | 295 (74) | 30 (68) | 104 (80) | 114 (73) | 32 (74) | 15 (65) | |

| Not reported | 68 (17) | 7 (16) | 15 (12) | 29 (18) | 9 (21) | 8 (35) | |

| Diagnosis of PCD | |||||||

| Definite diagnosisb | 262 (66) | 29 (66) | 81 (62) | 102 (65) | 35 (82) | 15 (65) | 0.12 (0.06-0.16) |

| Probable diagnosisc | 123 (31) | 15 (34) | 41 (32) | 52 (33) | 7 (16) | 8 (35) | |

| Diagnosis pendingd | 12 (3) | 0 | 8 (6) | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Ultrastructural defect | |||||||

| TEM not performed/pending | 200 (51) | 22 (50) | 64 (49) | 88 (57) | 18 (42) | 8 (35) | 0.17 (0.12-0.18) |

| Normal ultrastructure | 41 (10) | 9 (20) | 15 (12) | 9 (6) | 5 (12) | 3 (13) | |

| ODA and IDA defect | 62 (16) | 10 (23) | 17 (13) | 27 (17) | 6 (14) | 2 (8.5) | |

| ODA defect | 27 (7) | 1 (2) | 12 (9) | 10 (6) | 2 (4.5) | 2 (8.5) | |

| Microtubular disorganization and IDA | 29 (7) | 2 (5) | 10 (8) | 10 (6) | 2 (4.5) | 5 (22) | |

| Central complex defect | 17 (4) | 0 | 3 (2) | 6 (4) | 7 (16) | 1 (4) | |

| Other nonhallmark defect | 21 (5) | 0 | 9 (7) | 7 (4) | 3 (7) | 2 (9) | |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Current/former smoker | 7 (2) | NA | NA | 4 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 0.14 (0.07-0.19) |

| Smoking in household | 70 (18) | 6 (14) | 24 (18) | 34 (21) | 4 (10) | 2 (4) | |

| No reported active/passive smoking | 320 (80) | 38 (86) | 106 (82) | 119 (76) | 38 (88) | 19 (82) | |

Abbreviations: EPIC-PCD, Ear-Nose-Throat Prospective International Cohort of patients with PCD; IDA, inner dynein arm; NA, not applicable; ODA, outer dynein arm; PCD, primary ciliary dyskinesia; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Cramér V and bias-corrected 95% CIs are based on the χ2 test of independence. Scores range from 0 (no association) to 1 (strong association).

Biallelic pathogenic alteration or hallmark defect identified by TEM.

One or more of the following: abnormal high-speed videomicroscopy analysis findings, nasal nitric oxide value indicative for PCD, nonhallmark defect identified by electron microscopy, pathologic immunofluorescence finding, or genetic findings suggestive of PCD.

Newly recruited patients still under diagnostic investigation.

In total, 142 (36%) participants had situs inversus and 34 (9%) had known cardiac defects. Diagnosis was achieved based on local diagnostic protocols. Nasal nitric oxide measurements were performed on 265 (67%) participants, genetic testing on 281 (71%), TEM on 197 (50%), high-speed videomicroscopy analysis on 227 (57%), and immunofluorescence on 72 (18%) (eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 1). Based on ERS guidelines, with biallelic PCD-causing mutation or hallmark defect identified by TEM, definite PCD diagnosis was confirmed for 252 (63%) participants (Table 1).34 For the remaining participants, 125 (32%) PCD diagnoses were established by a combination of several other tests, including high-speed videomicroscopy analysis, immunofluorescence, and nasal nitric oxide, while the remaining 20 (5%) participants were newly diagnosed with strong clinical suggestion of PCD and diagnostic results pending at enrollment. Median (range) age at diagnosis was 9 (0-76) years.

Patient-Reported Ear Symptoms

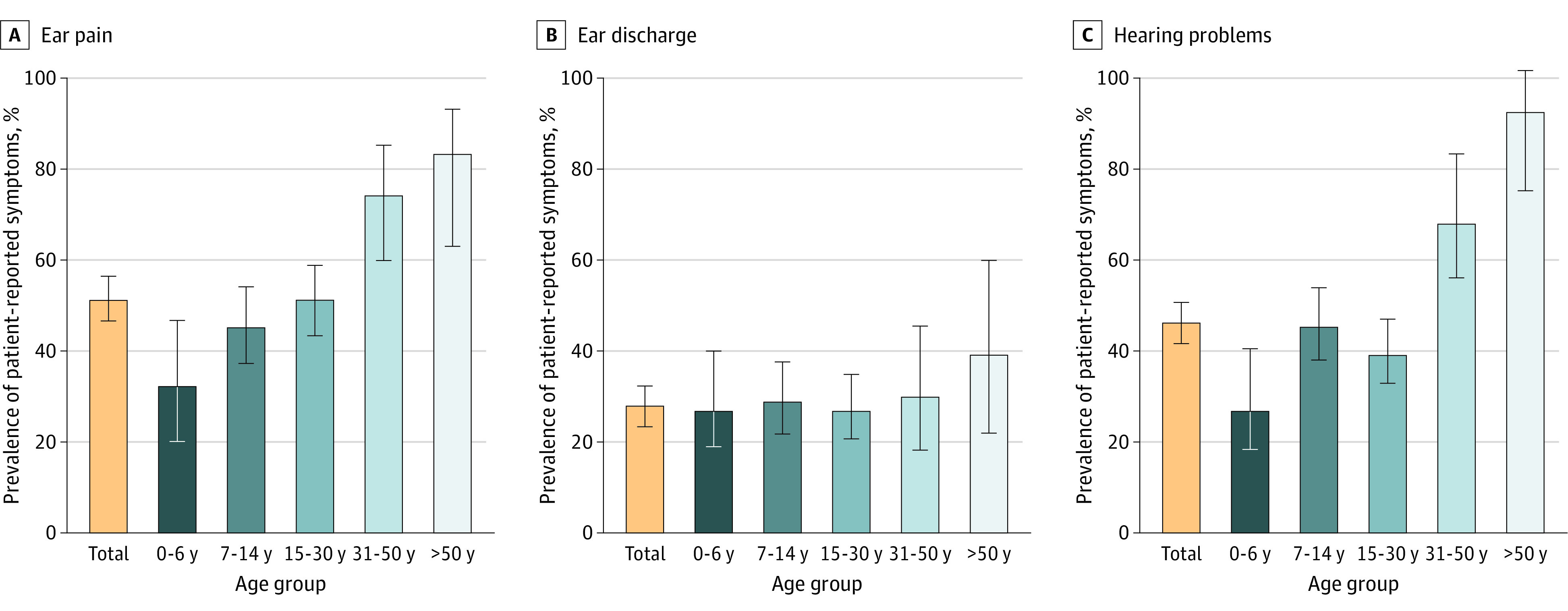

In total, 204 (51%) participants reported ear pain during the past 3 months, usually bilateral (Figure 1), and 52 (13%) participants experienced ear pain daily or often (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Unilateral or bilateral ear discharge was reported by 110 (28%) participants, and 24 (6%) participants characterized it as daily or often. Hearing problems—mostly bilateral—were reported by 183 (46%) participants. Hearing problems were the most common symptom reported frequently (daily or often) by 75 (19%) participants; 124 (31%) participants reported no ear symptoms (eFigure 2 in Supplement 1). Most participants reported that their most troublesome ENT symptoms occurred during winter months, especially during December and January. There was minimal to no association between age and frequency of reported ear discharge (Cramér V, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.08-0.13); however, there was a weak association between age and ear pain (Cramér V, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.11-0.19) and age and hearing problems (Cramér V, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.13-0.24) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Results of reported symptoms were similar in the subgroup of patients with definite diagnosis (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Figure 1. Prevalence of Self- and Parent-Reported Ear Symptoms Among EPIC-PCD Participants, Overall and by Age Group (N = 397).

EPIC-PCD indicates the Ear-Nose-Throat Prospective International Cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Clinical Assessment of the Ears

Of the 397 included participants, 13 (3%) had no otologic clinical assessment performed during their follow-up visit at ENT clinics. Table 2 summarizes findings from otoscopy for 384 participants. Signs of acute ear disease were rare; 6 (2%) participants had acute otitis media at examination with 9 affected ears. Thirty-eight (10%) participants had active ear discharge from 63 ears, and tympanic perforation was recorded for 30 (8%) participants affecting 39 ears. Retracted tympanic membrane was seen in 48 (13%) participants, including 75 affected ears. Otitis media with effusion—the most common finding—was recorded for 121 (32%) participants with 211 affected ears. Lastly, 69 (18%) participants had signs of tympanic sclerosis with 120 affected ears, and 35 (9%) participants had unilateral or bilateral tympanostomy tubes in place at examination (Table 2). From examination findings, retracted membrane and tympanic sclerosis differed by age, and it was more common among adults. Otoscopic findings were similar in the subgroup of patients with definite PCD diagnosis (eTable 5 in Supplement 1).

Table 2. Otoscopic Findings Among EPIC-PCD Participants, Overall and by Age Group.

| Outcome | No. (%)a | Cramér V (95% CI)b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 384) | Age 0-6 y (n = 40) | Age 7-14 y (n = 126) | Age 15-30 y (n = 156) | Age 31-50 y (n = 42) | Age >50 y (n = 20) | ||

| Acute otitis media | |||||||

| Bilateral | 3 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.10 (0.05-0.13) |

| Unilateral | 3 (1) | 0 | 0 | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | |

| None | 364 (95) | 38 (95) | 119 (95) | 146 (94) | 41 (98) | 20 (100) | |

| Not assessed | 14 (4) | 2 (5) | 4 (3) | 7 (4) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Ear discharge | |||||||

| Bilateral | 15 (4) | 1 (3) | 7 (5) | 5 (3) | 0 | 2 (10) | 0.11 (0.08-0.12) |

| Unilateral | 23 (6) | 1 (3) | 10 (8) | 10 (7) | 1 (3) | 1 (5) | |

| None | 341 (89) | 38 (95) | 107 (85) | 139 (89) | 40 (95) | 17 (85) | |

| Not assessed | 5 (1) | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 | |

| Tympanic perforation | |||||||

| Bilateral | 9 (2) | 0 | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 0 | 2 (10) | 0.12 (0.08-0.15) |

| Unilateral | 21 (6) | 1 (3) | 9 (7) | 9 (6) | 2 (5) | 0 | |

| None | 343 (89) | 36 (90) | 110 (88) | 139 (88) | 40 (95) | 18 (90) | |

| Not assessed | 11 (3) | 3 (8) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 0 | 0 | |

| Retracted membrane | |||||||

| Bilateral | 27 (7) | 0 | 7 (5) | 10 (6) | 4 (10) | 6 (30) | 0.18 (0.11-0.21) |

| Unilateral | 21 (5) | 2 (5) | 6 (5) | 9 (6) | 1 (3) | 3 (15) | |

| None | 318 (83) | 33 (83) | 109 (87) | 129 (83) | 37 (88) | 10 (50) | |

| Not assessed | 18 (5) | 5 (13) | 4 (3) | 8 (5) | 0 | 1 (5) | |

| Otitis media with effusion | |||||||

| Bilateral | 90 (23) | 13 (33) | 39 (31) | 26 (17) | 7 (17) | 5 (25) | 0.14 (0.09-0.16) |

| Unilateral | 31 (8) | 2 (5) | 12 (10) | 16 (10) | 0 | 1 (5) | |

| None | 244 (64) | 22 (55) | 66 (52) | 109 (70) | 34 (81) | 13 (65) | |

| Not assessed | 19 (5) | 3 (8) | 9 (7) | 5 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | |

| Tympanic sclerosis | |||||||

| Bilateral | 51 (13) | 0 | 9 (7) | 19 (12) | 14 (33) | 9 (45) | 0.19 (0.13-0.23) |

| Unilateral | 18 (5) | 0 | 5 (4) | 12 (8) | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| None | 277 (72) | 31 (78) | 97 (77) | 113 (72) | 25 (60) | 11 (55) | |

| Not assessed | 38 (10) | 9 (23) | 15 (12) | 12 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 | |

| Tympanostomy tubes | |||||||

| Bilateral | 16 (4) | 2 (5) | 6 (5) | 7 (4) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0.15 (0.08-0.21) |

| Unilateral | 19 (5) | 1 (3) | 4 (3) | 9 (6) | 4 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| None | 338 (88) | 34 (85) | 110 (87) | 138 (89) | 38 (90) | 18 (90) | |

| Not assessed | 11 (3) | 3 (8) | 6 (5) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Hearing aids | 29 (8) | 2 (5) | 16 (13) | 5 (3) | 2 (5) | 4 (20) | 0.19 (0.10-0.25) |

Abbreviation: EPIC-PCD; Ear-Nose-Throat Prospective International Cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia.

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Cramér V and bias-corrected 95% CIs are based on the χ2 test of independence. Scores range from 0 (no association) to 1 (strong association).

Tympanometry was performed for 216 (54%) participants. Examinations showed a normal middle ear status (type A) for both ears among 72 of 216 (33%) participants (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Type B, which is considered abnormal, was the most common tympanogram for 114 (53%) participants, followed by type C for 34 (16%) participants.

Based on local protocols, audiometry testing was performed for 273 (69%) participants and was usually pure tone (n = 205 [75%]) or a combination of pure tone, vocal, and bone conduction audiometry. In total, based on the WHO hearing loss grading system, 154 of 273 (56%) participants had no impairment (Table 3). Of the remaining participants, most had mild unilateral or bilateral impairment. Five participants had severe and 2 had profound impairment in at least 1 ear. Of all participants, 29 had hearing aids; however, 3 participants refused to wear them (Table 2).

Table 3. Audiometric Findings Among EPIC-PCD Participants, Overall and by Age Group.

| Hearing loss gradea | No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 273) | Age 0-6 y (n = 18) | Age 7-14 y (n = 84) | Age 15-30 y (n = 110) | Age 31-50 y (n = 41) | Age >50 y (n = 20) | Affected ears (N = 546) | |

| Normal hearing (≤25 db) | |||||||

| Bilateral | 154 (56) | 7 (39) | 53 (63) | 77 (70) | 17 (41) | 0 | 341 (63) |

| Unilateral | 33 (12) | 1 (6) | 12 (14) | 14 (13) | 4 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Mild hearing loss (26-40 dB) | |||||||

| Bilateral | 55 (20) | 8 (44) | 12 (14) | 13 (12) | 14 (34) | 8 (40) | 158 (29) |

| Unilateral | 48 (18) | 1 (6) | 15 (18) | 17 (15) | 9 (22) | 6 (30) | |

| Moderate hearing loss (41-60 dB) | |||||||

| Bilateral | 7 (3) | 1 (6) | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | 3 (15) | 35 (6) |

| Unilateral | 21 (8) | 1 (6) | 4 (5) | 6 (5) | 5 (12) | 5 (25) | |

| Severe hearing loss (61-80 dB) | |||||||

| Bilateral | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | 6 (1) |

| Unilateral | 4 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 3 (15) | |

| Profound hearing loss (≥81 dB) | |||||||

| Bilateral | 1 (0) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0) |

| Unilateral | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | |

| Could not be performedb | 3 (1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 (0) |

Abbreviations: EPIC-PCD, Ear-Nose-Throat Prospective International Cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia; NA, not applicable.

Hearing loss grades are based on the World Health Organization hearing loss grading system. Categories are not exclusive because participants can have different hearing loss grades in each ear.

In 3 patients, audiometry was recorded as not performed due to technical reasons for 1 of the ears.

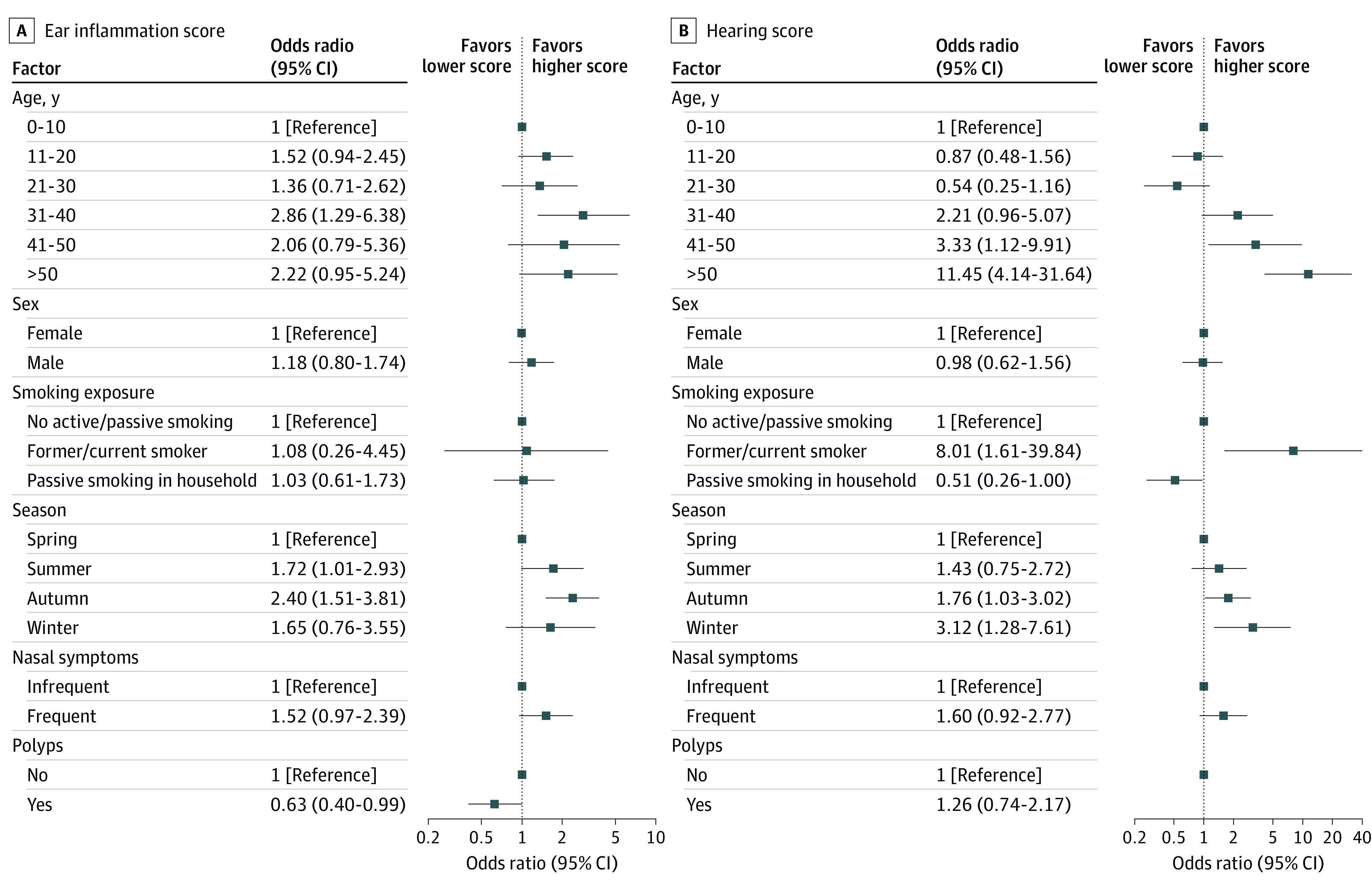

Factors Associated With Ear Disease

There was minimal to no association between age, sex, smoking status, reported runny or blocked nose, and nasal polyps and the ear inflammation score (Figure 2A). The only factor that showed an association was season of study visit; autumn (odds ratio, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.51-3.81) showed a higher risk of problems associated with ear inflammation compared with spring. For hearing, age 30 years and older was associated with higher hearing score, and the risk increased with age (Figure 2B). Active smoking also showed a strong association (odds ratio, 8.01; 95% CI, 1.61-39.84) compared with no active or passive smoking; however, the number of smokers participating in the study was very small (7 [2%] participants). Compared with autumn and winter, participants who visited the clinic in spring or summer had less hearing impairment (Figure 2B). Findings were similar in the subgroup of patients with definite PCD diagnosis (eFigure 3 in Supplement 1). In the subgroup of participants with available TEM results (eFigure 4 in Supplement 1), there were no associations of specific ultrastructural defects with ear problems.

Figure 2. Factors Associated With Ear Inflammation and Hearing Scores Among EPIC-PCD Participants.

A, For the ear inflammation score, any reported ear pain or ear discharge, presence of tympanostomy tubes, otitis media, and tympanic perforation during otoscopy were included, each of which were scored as 0 (absence) or 1 (presence), with a total score ranging from 0 to 4. B, For the hearing score, reported hearing problems (0-4, indicating never to daily) and audiometry results (0-4, indicating normal to profound hearing impairment) were included, with a total score ranging from 0 to 8. EPIC-PCD indicates the Ear-Nose-Throat Prospective International Cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia.

Discussion

This study benefitted from standardized acquisition of patient-reported symptoms and clinical assessments to characterize otologic disease in children and adults with PCD. Ear pain and hearing problems were frequently reported, most commonly by adults 30 years and older. Otitis media with effusion was the most common finding in ear examinations, and many adult participants had signs of tympanic sclerosis, a frequent sequelae of recurrent episodes of otitis media, chronic OME, or tympanostomy tubes insertion. Age appeared the main risk factor associated with hearing impairment.

Comparison With Other Studies

Because most previous studies were retrospective and information was inconsistently recorded for direct comparisons, prevalence of reported otologic symptoms varied substantially. For instance, in a review summarizing existing literature before 2016, there was important heterogeneity of study design and population selection, such as reporting a prevalence of hearing impairment from 8% to 100%.3 A retrospective study in France included 64 adult patients and reported hearing loss for 53%, ear pain for 14%, and ear discharge for 8%, while 67% had hearing impairment assessed by audiogram.35 Another recent French study showed 71% of 17 adult patients with bronchiectasis and PCD had hearing impairment, of which 24% was conductive.36 Older populations and how symptoms were recorded in medical records possibly explain some differences with these findings. Despite history of recurrent and chronic middle ear disease, there was no record of cholesteatoma for any study participant, which is in accordance with previous literature.37 We reported 38% to 41% prevalence of OME among children 0 to 14 years old, much lower than the more than 90% OME reported in a retrospective study including pediatric patients in France.13 This is expected, as the authors defined OME as any episode during a period of 12 months, while the present results captured OME only at study visit. A recent prospective study among 47 children with PCD in North America reported 38% hearing loss and 19% ear pain.38 Only including children in the study possibly explains differences with the present study, yet a study in the UK reported abnormal audiometry findings for more than 50% of 271 children.39 Prevalence of PCD symptoms may also be underreported by patients and parents because they are accustomed to them. It is also particularly difficult for parents to identify ear symptoms of younger children. It is possible that the way patients are asked about specific symptoms during clinical visits may account for some of the recorded differences among studies. In a survey of 74 children and adults with PCD in Switzerland, which also used the FOLLOW-PCD questionnaire, participants reported similar prevalence and frequency of most otologic symptoms compared with the present study, with just a slightly higher overall prevalence of hearing problems, probably because of older age.38 In comparison with 2019 WHO data on hearing impairment that showed that 20% of the global population was affected, we found a much higher prevalence of hearing impairment among participants with PCD.40 Data from a nationally representative sample in the US (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) showed a 0.6% prevalence of any hearing loss among 20- to 29-year-olds and 63% among people 70 years and older,41 compared with 30% among 15- to 30-year-olds and 100% among people 50 years and older in the present study. In addition, a recent study on the prevalence of presbycusis in an ontologically normal population in Spain reported age-related hearing loss only in individuals older than 60 years, which only reached 100% of the population in those older than 85 years.42 The much higher prevalence of hearing loss in the present population supports that hearing loss among people with PCD increases with age, even taking into account expected age-related increase not associated with PCD.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to combine patient-reported symptoms and clinical examination findings of otologic disease among people with PCD; use data from a well-defined, multicenter PCD cohort; and is the largest to date focusing on upper airways. The standardized, PCD-specific questionnaire and ENT evaluation form enhanced collecting high-quality data; it also allows for comparisons with ongoing and future studies using the same tools. Because EPIC-PCD is nested in routine care, we had a high response rate, and most invited patients agreed to participate in the study; however, patients with fewer ENT problems might have been less willing to participate. Not all assessments were performed for all participants because it was not requested by the study protocol. In turn, this may have resulted in selection bias, as tympanometry and audiometry might have been performed most likely for participants with severe ear disease. Information on the type of hearing loss would allow to better understand the proportion of hearing loss attributed to PCD but was not recorded in this study. However, we found bilateral or unilateral hearing loss in patients of all ages, which cannot be explained solely on age-related hearing impairment. Because recruitment started in early 2020, these results are possibly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on anecdotal evidence, patients with PCD experienced fewer infections due to careful shielding, which possibly led to decreased prevalence of ear problems.43,44 As the cohort continues to be followed up longitudinally, it will be important to study possible changes in symptoms and signs coinciding with relaxing pandemic measures. Because we found season to be a main factor associated with ear inflammation and hearing scores, continued longitudinal follow-up will also allow us to study seasonal variations of ear disease for longer time periods. Although the present study population was large, we still had limited statistical power to study the role of some subgroup characteristics, such as smoking, or different ultrastructural defect and gene groups.

Conclusions

This cross-sectional study demonstrated that in addition to respiratory symptoms, many people with PCD experience ear problems. Although ear infections are less common in adulthood, sequelae from chronic infections remain, and hearing is often impaired, especially among older patients with PCD. Whether this is a part of the natural disease course or preventable by early, proper management remains to be studied. Differences in frequency of ear problems—whether self-reported or identified during clinical examination—highlight differences in disease expression and possibly indicate the existence of clinical phenotypes. Understanding how disease expression differs; how ear, sinonasal, and lower respiratory findings correlate; and how PCD progresses during lifetime should inform clinical decisions about follow-up and medical care. Because people with PCD underestimate and underreport symptoms, it is possible that many do not receive proper monitoring and management. Therefore, multidisciplinary PCD care needs to include routine otologic and audiologic assessments for patients of all ages, even without specific complaints.

eFigure 1. Flowchart of patients with PCD who were invited and participated in EPIC-PCD and the study

eTable 1. Centre and diagnostic information of EPIC-PCD participants, overall and by age group (N=397)

eTable 2. Genetic mutations reported in EPIC-PCD participants with biallelic pathogenic variants or compound heterozygosity (N=192)

eTable 3. Frequency of self- and parent-reported ear symptoms of EPIC-PCD participants, overall and by age group (N=397)

eFigure 2. Venn diagram showing overlap of self- and parent-reported symptoms of EPIC-PCD participants (N=397)

eTable 4. Frequency of self- and parent-reported ear symptoms of EPIC-PCD participants with definite PCD diagnosis, overall and by age group (N=262)

eTable 5. Otoscopy findings of EPIC-PCD participants with definite diagnosis, overall and by age group (N=255)

eTable 6. Tympanometry findings of EPIC-PCD participants, overall and by age group (N=216)

eFigure 3. Factors associated with the A) ear inflammation and B) hearing score among EPIC-PCD participants with definite PCD diagnosis

eFigure 4. Association of ciliary ultrastructural defect with the A) ear inflammation and B) hearing score among EPIC-PCD participants

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Lucas JS, Davis SD, Omran H, Shoemark A. Primary ciliary dyskinesia in the genomics age. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(2):202-216. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30374-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro AJ, Davis SD, Ferkol T, et al. ; Genetic Disorders of Mucociliary Clearance Consortium . Laterality defects other than situs inversus totalis in primary ciliary dyskinesia: insights into situs ambiguus and heterotaxy. Chest. 2014;146(5):1176-1186. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goutaki M, Meier AB, Halbeisen FS, et al. Clinical manifestations in primary ciliary dyskinesia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(4):1081-1095. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00736-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy MP, Omran H, Leigh MW, et al. Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2814-2821. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanaken GJ, Bassinet L, Boon M, et al. Infertility in an adult cohort with primary ciliary dyskinesia: phenotype-gene association. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(5):1700314. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00314-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stannard W, O’Callaghan C. Ciliary function and the role of cilia in clearance. J Aerosol Med. 2006;19(1):110-115. doi: 10.1089/jam.2006.19.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halbeisen FS, Pedersen ESL, Goutaki M, et al. Lung function from school age to adulthood in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2022;60(4):2101918. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01918-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis SD, Rosenfeld M, Lee HS, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: longitudinal study of lung disease by ultrastructure defect and genotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(2):190-198. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0548OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behan L, Dimitrov BD, Kuehni CE, et al. PICADAR: a diagnostic predictive tool for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(4):1103-1112. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01551-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis SD, Ferkol TW, Rosenfeld M, et al. Clinical features of childhood primary ciliary dyskinesia by genotype and ultrastructural phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(3):316-324. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1672OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommer JU, Schäfer K, Omran H, et al. ENT manifestations in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: prevalence and significance of otorhinolaryngologic co-morbidities. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268(3):383-388. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1341-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piatti G, De Santi MM, Torretta S, Pignataro L, Soi D, Ambrosetti U. Cilia and ear: a study on adults affected by primary ciliary dyskinesia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2017;126(4):322-327. doi: 10.1177/0003489417691299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prulière-Escabasse V, Coste A, Chauvin P, et al. Otologic features in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(11):1121-1126. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi K, Kitano M, Sakaida H, et al. Analysis of otologic features of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38(10):e451-e456. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berman S. Otitis media in children. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(23):1560-1565. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506083322307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majithia A, Fong J, Hariri M, Harcourt J. Hearing outcomes in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia—a longitudinal study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(8):1061-1064. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.el-Sayed Y, al-Sarhani A, al-Essa AR. Otological manifestations of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1997;22(3):266-270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1997.00895.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell RG, Birman CS, Morgan L. Management of otitis media with effusion in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia: a literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(12):1630-1638. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen TN, Alanin MC, von Buchwald C, Nielsen LH. A longitudinal evaluation of hearing and ventilation tube insertion in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;89:164-168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolter NE, Dell SD, James AL, Campisi P. Middle ear ventilation in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76(11):1565-1568. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadfield PJ, Rowe-Jones JM, Bush A, Mackay IS. Treatment of otitis media with effusion in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1997;22(4):302-306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1997.00020.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreicher KL, Schopper HK, Naik AN, Hatch JL, Meyer TA. Hearing loss in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;104:161-165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshinaga-Itano C, Sedey AL, Coulter DK, Mehl AL. Language of early- and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics. 1998;102(5):1161-1171. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiyonobu K, Xu Y, Feng G, et al. Analysis of the clinical features of Japanese patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2022;49(2):248-257. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2021.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghedia R, Ahmed J, Navaratnam A, Harcourt J. No evidence of cholesteatoma in untreated otitis media with effusion in children with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;105:176-180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boon M, Smits A, Cuppens H, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: critical evaluation of clinical symptoms and diagnosis in patients with normal and abnormal ultrastructure. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9(1):11. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goutaki M, Lam YT, Alexandru M, et al. ; EPIC-PCD team . Study protocol: the ear-nose-throat (ENT) prospective international cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (EPIC-PCD). BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e051433. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas JS, Barbato A, Collins SA, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(1):1601090. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01090-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806-808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goutaki M, Papon JF, Boon M, et al. Standardised clinical data from patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: FOLLOW-PCD. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(1):00237-2019. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00237-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerger J. Clinical experience with impedance audiometry. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;92(4):311-324. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1970.04310040005002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Report of the Informal Working Group on Prevention of Deafness and Hearing Impairment Programme Planning. World Health Organization . June 1991. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/58839

- 33.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoemark A, Boon M, Brochhausen C, et al. ; representing the BEAT-PCD Network Guideline Development Group . International consensus guideline for reporting transmission electron microscopy results in the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia (BEAT PCD TEM Criteria). Eur Respir J. 2020;55(4):1900725. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00725-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bequignon E, Dupuy L, Zerah-Lancner F, et al. Critical evaluation of sinonasal disease in 64 adults with primary ciliary dyskinesia. J Clin Med. 2019;8(5):619. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexandru M, de Boissieu P, Benoudiba F, et al. Otological manifestations in adults with primary ciliary dyskinesia: a controlled radio-clinical study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(17):5163. doi: 10.3390/jcm11175163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackler RK, Santa Maria PL, Varsak YK, Nguyen A, Blevins NH. A new theory on the pathogenesis of acquired cholesteatoma: mucosal traction. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(suppl 4):S1-S14. doi: 10.1002/lary.25261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zawawi F, Shapiro AJ, Dell S, et al. Otolaryngology manifestations of primary ciliary dyskinesia: a multicenter study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(3):540-547. doi: 10.1177/01945998211019320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubbo B, Best S, Hirst RA, et al. ; English National Children’s PCD Management Service . Clinical features and management of children with primary ciliary dyskinesia in England. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105(8):724-729. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-317687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haile LM, Kamenov K, Briant PS, et al. ; GBD 2019 Hearing Loss Collaborators . Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990-2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):996-1009. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00516-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curhan G, Curhan S. Epidemiology of hearing impairment. In: Popelka GR, Moore BCJ, Fay RR, Popper AN, eds. Hearing Aids. Springer International Publishing; 2016:21-58. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-33036-5_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodríguez-Valiente A, Álvarez-Montero Ó, Górriz-Gil C, García-Berrocal JR. Prevalence of presbycusis in an otologically normal population. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp (Engl Ed). 2020;71(3):175-180. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen ESL, Collaud ENR, Mozun R, et al. COVID-PCD: a participatory research study on the impact of COVID-19 in people with primary ciliary dyskinesia. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00843-2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00843-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen ESL, Collaud ENR, Mozun R, et al. ; COVID-PCD patient advisory group . Facemask usage among people with primary ciliary dyskinesia during the covid-19 pandemic: a participatory project. Int J Public Health. 2021;66:1604277. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2021.1604277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Flowchart of patients with PCD who were invited and participated in EPIC-PCD and the study

eTable 1. Centre and diagnostic information of EPIC-PCD participants, overall and by age group (N=397)

eTable 2. Genetic mutations reported in EPIC-PCD participants with biallelic pathogenic variants or compound heterozygosity (N=192)

eTable 3. Frequency of self- and parent-reported ear symptoms of EPIC-PCD participants, overall and by age group (N=397)

eFigure 2. Venn diagram showing overlap of self- and parent-reported symptoms of EPIC-PCD participants (N=397)

eTable 4. Frequency of self- and parent-reported ear symptoms of EPIC-PCD participants with definite PCD diagnosis, overall and by age group (N=262)

eTable 5. Otoscopy findings of EPIC-PCD participants with definite diagnosis, overall and by age group (N=255)

eTable 6. Tympanometry findings of EPIC-PCD participants, overall and by age group (N=216)

eFigure 3. Factors associated with the A) ear inflammation and B) hearing score among EPIC-PCD participants with definite PCD diagnosis

eFigure 4. Association of ciliary ultrastructural defect with the A) ear inflammation and B) hearing score among EPIC-PCD participants

Data Sharing Statement