Abstract

Sleep is crucial for brain development. Sleep disturbances are prevalent in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Strikingly, these sleep problems are positively correlated with the severity of ASD core symptoms such as deficits in social skills and stereotypic behavior, indicating that sleep problems and the behavioral characteristics of ASD may be related. In this review, we will discuss sleep disturbances in children with ASD and highlight mouse models to study sleep disturbances and behavioral phenotypes in ASD. In addition, we will review neuromodulators controlling sleep and wakefulness and how these neuromodulatory systems are disrupted in animal models and patients with ASD. Lastly, we will address how the therapeutic interventions for patients with ASD improve various aspects of sleep. Together, gaining mechanistic insights into the neural mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances in children with ASD will help us to develop better therapeutic interventions.

Highlights

-

•

Sleep disturbances are prevalent in children with ASD and are positively correlated with the severity of ASD core symptoms.

-

•

Mouse models are valid tools to understand the mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances and related symptoms in ASD.

-

•

Elucidating neuromodulatory mechanisms underlying sleep problems in ASD will offer insights to novel therapeutic strategies.

1. Sleep disturbances in children with ASD

ASD occurs in approximately 1% of children (Elsabbagh et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2011). About 40–80% of children with ASD suffer from sleep disturbances including delayed sleep onset, frequent night awakenings, and short sleep episodes (Richdale and Schreck, 2009; Souders et al., 2009). Their sleep problems occur at the same time as the development of ASD symptoms in early childhood (Verhoeff et al., 2018). Children with ASD show an increase in sleep problems throughout development, whereas typically developing (TD) children sleep better as they grow up (Richdale and Prior, 1995; Sivertsen et al., 2012; Verhoeff et al., 2018).

Sleep questionnaires, such as the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), are used in most studies to identify sleep disturbances in ASD patients. This questionnaire specifically has questions categorized into eight sections: (1) Bedtime resistance; (2) Sleep onset delay; (3) Sleep duration; (4) Sleep anxiety; (5) Night wakings; (6) Parasomnias; (7) Sleep disordered breathing; and (8) Daytime sleepiness. Children with ASD were reported to have greater bedtime resistance, delayed sleep onset, shorter sleep duration, sleep anxiety, increased sleep fragmentation, parasomnias, and early morning awakenings (Chen et al., 2021; Giannotti et al., 2008; Hodge et al., 2014; Honomichl et al., 2002; Irwanto et al., 2016; May et al., 2015; Mazurek and Petroski, 2015; Tudor et al., 2015; van der Heijden et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2016). Other sleep questionnaires and subjective measurements of sleep patterns such as sleep diaries reported similar sleep disturbances (Anders et al., 2012; Cotton and Richdale, 2006; Dominick et al., 2007; Gail Williams et al., 2004; Goldman et al., 2012; Hirata et al., 2016; Humphreys et al., 2014; Krakowiak et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2006; Mutluer et al., 2016; Patzold et al., 1998; Richdale and Prior, 1995; Schreck et al., 2004; Sivertsen et al., 2012; Taira et al., 1998; van der Heijden et al., 2018). Objective sleep measures such as actigraphy or polysomnography are more informative to determine the exact sleep problems. Comparative studies, using a mixture of both sleep questionnaires and polysomnography/actigraphy, have identified symptoms such as early morning awakenings, multiple night awakenings, variations in total sleep time, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep latency, insomnias, delayed sleep onset, daytime sleepiness and decreased sleep efficiency in children with ASD compared with TD children of the same age (Aathira et al., 2017; Allik et al., 2006; Baker et al., 2013; Buckley et al., 2010; Carmassi et al., 2019; Diomedi et al., 1999; Elia et al., 2000; Fletcher et al., 2017; Giannotti et al., 2011; Godbout et al., 2000; Goldman et al., 2009; Goodlin-Jones et al., 2008; Hering et al., 1999; Malow et al., 2006; Miano et al., 2007; Richdale et al., 2014; Takase et al., 1998; Veatch et al., 2016; Wiggs and Stores, 2004). Children with ASD were also shown to exhibit significantly lower slow-wave activity following sleep onset suggesting that dysregulation of sleep homeostasis may contribute to their sleep disturbances (Arazi et al., 2020). Other factors also contribute to sleep problems in children with ASD including an evening chronotype, poor sleep hygiene, medication use, family history of sleep problems as well as comorbid disorders and symptoms such as epilepsy, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), asthma, anxiety and depression symptoms, poor growth, poor vision, suppressed appetite, and upper respiratory problems (Gail Williams et al., 2004; Hirata et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2006; van der Heijden et al., 2018).

Sleep disturbances can worsen ASD symptoms (Anders et al., 2012; Goldman et al., 2009; MacDuffie et al., 2020a, MacDuffie et al., 2020b; Richdale et al., 2014; Schreck et al., 2004). However, the causal relationship between sleep problems and the related symptoms is not well understood. Children with ASD who are good sleepers generally did not differ from TD peers in their sleep architecture and displayed fewer affective problems and better social interactions compared with bad sleepers with ASD (Malow et al., 2006). On the other hand, children with ASD who are bad sleepers displayed more severe behavioral symptoms such as inattention, hyperactivity, repetitive behaviors and problems in sociability compared with good sleepers with ASD (Aathira et al., 2017; Goldman et al., 2009). The sleep problems in children with ASD were shown to be decreased when their anxiety, as reported by the parents, was low (Fletcher et al., 2017). Furthermore, sleep problems and sensory sensitivities in ASD children are positively correlated (Linke et al., 2021). Increased sleep latency was shown to be associated with an over-connectivity between the thalamus and auditory cortex measured during natural sleep in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the activity of the auditory cortex was elevated in children with ASD suggesting an abnormal thalamocortical functional connectivity, potentially contributing to sleep problems and sensory sensitivities in ASD (Linke et al., 2021). ASD patients display disrupted coordination between slow oscillations and sleep spindles in the electroencephalogram (EEG) during stage 2 (N2) non-REM (NREM) sleep, and a spindle density deficiency during N3 NREM sleep in polysomnography recordings, suggesting abnormal thalamocortical interactions and thalamic reticular nucleus dysfunction in ASD patients, which consequently influences memory consolidation during sleep (Mylonas et al., 2022).

Taken together, sleep disturbances during development may have a long-lasting impact on behaviors in children. Sleep problems in children with ASD are associated with increased autism scores such as deficits in social skills and stereotypic behavior, indicating that sleep problems and ASD symptoms may be related. Longitudinal studies to examine how sleep patterns change over time in children with ASD, and how such changes are related to the other behaviors will be important to understand the link between sleep and ASD symptoms throughout development.

2. Sleep disturbances in mouse models of ASD

Animal models provide useful tools to investigate the causal role of genetic mutations and environmental factors in symptoms of ASD (Crawley, 2012). A variety of mouse models incorporating genetic abnormalities associated with ASD patients have been generated and used to understand the mechanisms underlying ASD symptoms and to test pharmacological targets to treat core symptoms of ASD. About 10–20% of patients with ASD have an identified genetic etiology such as chromosomal rearrangements, mendelian disorders (Fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome), mutations in synaptic genes (that encode for SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains protein 3 [Shank3] and synaptic Ras GTPase activating protein [SynGAP]) and copy number variations (such as 16p11.2 deletion) (Levy et al., 2011; Marshall et al., 2008; Pinto et al., 2010; Sanders et al., 2011; Sebat et al., 2007). Data from clinical cohorts with identified genetic etiology and transgenic animal models may provide key insights into the role of ASD-related genes in sleep pathology. Sleep disturbances in rodent models of ASD have been thoroughly reviewed in previously published papers (Doldur-Balli et al., 2022; Wintler et al., 2020). In this review, we will focus on sleep disturbances in 16p11.2 deletion, Syngap1, Shank3, and Fragile X messenger ribonucleoprotein (Fmr1) KO mouse models of ASD that have been well characterized to have sleep disturbances.

2.1. 16p11.2 deletion

The 16p11.2 copy number variation is observed in about 1% of ASD cases (Kumar et al., 2008; Weiss et al., 2008) and was shown to be associated with short sleep duration and frequent arousals during sleep (Hanson et al., 2010; Kamara et al., 2021; Tabet et al., 2012).

The 16p11.2 chromosomal region is highly conserved in the mouse chromosome (Blumenthal et al., 2014), and the copy number variation in this region was thus modeled in mice. Mice hemizygous for the 16p11.2 deletion (16p11.2+/−) exhibit hyperactivity, heightened anxiety, impaired learning and memory, reduced ultrasonic vocalizations, and sensory and motor abnormalities (Angelakos et al., 2017; Arbogast et al., 2016; Grissom et al., 2018; Horev et al., 2011; Lynch et al., 2020; Portmann et al., 2014; Pucilowska et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2015a, Yang et al., 2015b). 16p11.2+/− deletion in male mice is associated with sleep deficits including reduced NREM sleep (Angelakos et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2018) and longer wake bout duration, while no differences were found in female 16p11.2+/− mice (Angelakos et al., 2017). Another study showed that REM sleep is reduced in male 16p11.2+/− mice due to attenuated initiation and maintenance of REM sleep episodes (Lu et al., 2018). In 16p11.2+/− mice, whole-cell patch clamp recordings demonstrated that the excitability of GABAergic neurons in the ventral medulla (vM) projecting to the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG) is reduced (Lu et al., 2018). Given that the vM neurons and their projections to the vlPAG promote REM sleep (Weber et al., 2015), their reduced excitability may explain REM sleep impairments in 16p11.2+/− mice.

2.2. Syngap1 mutations

The synaptic Ras-GTPase-activating protein, SynGAP, is enriched in the postsynaptic density, and mutations in this gene are associated with abnormal dendritic spine maturation (Clement et al., 2012). Clinical studies have shown that SYNGAP1 mutations are closely associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. SYNGAP1 mutations are estimated to account for 0.5–1% of intellectual disability cases (Berryer et al., 2013; Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study, 2015; 2017). SYNGAP1 mutations also contribute to sleep problems, including initiating and maintaining sleep (Berryer et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2015; Prchalova et al., 2017; Vlaskamp et al., 2019). Sleep promoting therapeutics, discussed in detail below in section IV, such as melatonin, clonidine, or trazodone have been reported to improve sleep in patients with SYNGAP1 mutations (Vlaskamp et al., 2019).

Syngap1+/− mice exhibit reduced social novelty preference, cognitive deficits, susceptibility to seizures, increased locomotor activity, impaired memory, increased startle reflex, decreased sensitivity to pain, impaired motor function, and structural abnormalities in dendritic spines during development (Berryer et al., 2016; Clement et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2009; Muhia et al., 2010, 2012; Nakajima et al., 2019; Ozkan et al., 2014). Syngap1+/− mice were shown to spend less time in REM sleep compared with wild-type (WT) littermates (Angelakos and Abel, 2017). Following 6 h of sleep deprivation, NREM sleep was elevated in Syngap1+/− mice with a blunted increase in the delta power, suggesting an impaired homeostatic response following sleep deprivation (Angelakos and Abel, 2017). A higher baseline delta power in Syngap1+/− mice compared with WT controls may contribute to the blunted slow wave activity during the sleep rebound. Seizure activity is another symptom observed in clinical cohorts with SYNGAP1 mutations (Berryer et al., 2013; Carvill et al., 2013; Mignot et al., 2016; Parker et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2020; von Stülpnagel et al., 2015), which has been reproduced in Syngap1+/− mice (Sullivan et al., 2020). In Syngap1+/− mice, myoclonic seizures predominantly occur during NREM sleep at P60. From P60 to P120, the average seizure duration significantly increased due to the emergence of multiple seizure phenotypes. Furthermore, Syngap1+/− mice spent more time asleep during the light phase compared with the WT mice. Overall, Syngap1+/− mice exhibit a progressive worsening of sleep and epilepsy with age (Sullivan et al., 2020).

2.3. Shank3 mutations

The Shank gene family encodes scaffolding proteins located in the postsynaptic density of glutamatergic synapses, which are important for synaptic function and development (Sala et al., 2015). Mutations in the Shank gene family account for approximately 1% of ASD cases (Leblond et al., 2014). Disruptions in Shank genes, particularly Shank3 polymorphisms, are implicated in pathophysiological changes in neurodevelopment such as Phelan-McDermid syndrome and ASD in humans (Anderlid et al., 2002; Boccuto et al., 2013; Boeckers et al., 2002; Bonaglia et al., 2001; Bro et al., 2017; Costales and Kolevzon, 2015; Durand et al., 2007; Gauthier et al., 2009; Moessner et al., 2007; Naisbitt et al., 1999; Smith-Hicks et al., 2021; Soorya et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2003) and social deficits and repetitive behaviors in mice (Peça et al., 2011). Phelan-McDermid syndrome patients carrying a Shank3 deletion exhibit delayed sleep onset and frequent night awakenings particularly during adolescence (Ingiosi et al., 2019).

Shank3ΔC/ΔC mice, whose exon 21 is deleted, spend less time asleep and have fragmented sleep during juvenile (P25-41), adolescent (P42-56) and adult stages compared with WT littermates (Ingiosi et al., 2019; Lord et al., 2022; Medina et al., 2022). During P23-59, Shank3ΔC/ΔC mice showed an increase in REM sleep due to an increased frequency of REM sleep episodes during the light phase relative to WT (Medina et al., 2022). Similar to Shank3ΔC/ΔC mice, a homozygous InsG3680 mutation in the Shank3 gene (Shank3 InsG3680 knock-in mice) (Zhou et al., 2016) caused a reduction of NREM sleep, especially during the light phase (Bian et al., 2022). While Shank3 heterozygotes (Shank3WT/ΔC) do not exhibit significant differences in their sleep architecture during juvenile and adolescent stages, sleep disruption during early development (P14-21) and post-adolescence (P56-63) impaired sociability and social novelty preference, respectively (Lord et al., 2022). Similarly, increasing NREM sleep in Shank3 InsG3680+/+ mice during this critical developmental period (P35-42) by the injection of flupirtine, a selective KCNQ2/KCNQ3 potassium channel opener, or opto- and chemogenetic inhibition of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) improved sleep and restored social novelty preference in adulthood (Bian et al., 2022). Therefore, sleep disruptions in Shank3WT/ΔC mice during development exacerbated social behavioral deficits, which could be mitigated through improved sleep.

2.4. Fmr1 knockout

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) is caused by loss of function mutations in the Fragile X messenger ribonucleoprotein 1 gene (Fmr1) that encodes the RNA binding protein FMRP (O'Donnell and Warren, 2002; Verkerk et al., 1991). 2–5% of children with ASD have FXS (Hagerman et al., 2005; Kaufmann et al., 2004). FXS patients exhibit sleep disturbances such as frequent night waking, trouble falling asleep, delayed onset to REM sleep, disrupted cyclic alternating pattern, daytime sleepiness, restless sleep and sleep apnea (Kidd et al., 2014; Kronk et al., 2009, 2010; Miano et al., 2008; Musumeci et al., 1995; Richdale, 2003).

Fmr1 KO mice exhibit a reduction in REM sleep due to decreased frequency of REM sleep episodes during 1-h recordings at the light phase (Boone et al., 2018) while the overall time spent in REM sleep throughout the light and dark phase is unknown. Abnormal sleep architecture in Fmr1 KO mice may depend on the developmental stage of these mice. Fmr1 KO mice do not exhibit any differences in the amount of sleep compared with WT mice at P21 while they sleep less during the light phase at P70 and P180 (Saré et al., 2017), suggesting that sleep deficits may arise in adulthood. Furthermore, Fmr1 KO mice exhibit sensory hyperexcitability, susceptibility to seizures, decreased synaptic pruning in the hippocampus, cognitive impairments, changes in functional connectivity of hippocampal or neocortical circuits, and an abnormal size of the hippocampus (Berry-Kravis, 2002; Boone et al., 2018; Chen and Toth, 2001; Gibson et al., 2008; Gonçalves et al., 2013; Haberl et al., 2015; Hall et al., 2013; Hays et al., 2011; Hessl et al., 2004; Kates et al., 1997; Molnár and Kéri, 2014; Musumeci et al., 1988, 1999, 2000; Pfeiffer and Huber, 2007; Testa-Silva et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2014). In line with previous studies describing aberrant hippocampal activity and impaired memory in Fmr1 KO mice and FXS patients (Haberl et al., 2015; Hall et al., 2013; Hessl et al., 2004; Kates et al., 1997; Molnár and Kéri, 2014; Pfeiffer and Huber, 2007; Seese et al., 2014; Testa-Silva et al., 2012), Fmr1 KO mice exhibit an increase in the duration and a lower peak frequency in sharp-wave ripples during NREM sleep and quiet wake (Boone et al., 2018), which may consequently impair memory consolidation (Ego-Stengel and Wilson, 2010; Girardeau et al., 2009; Jadhav et al., 2012).

Taken together, the neural mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances in these animal models of ASD remain to be investigated. Elucidating neural circuits and molecular mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances will help to improve sleep in ASD patients and further reveal whether improving sleep quality could be beneficial for attenuating related behavioral symptoms.

3. Neuromodulators implicated in sleep disturbances in ASD

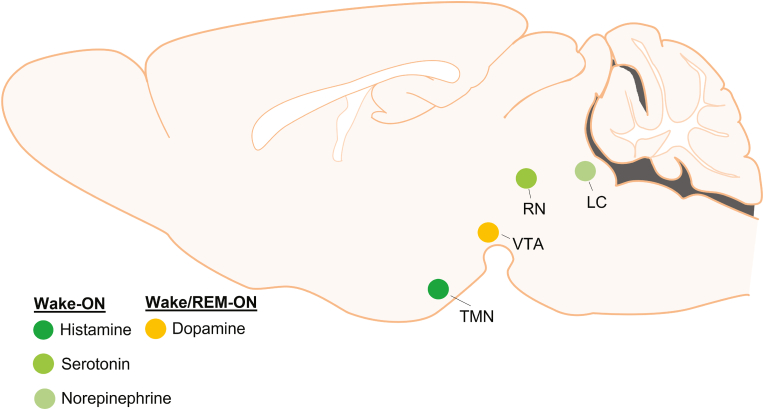

Sleep, wakefulness and transitions between them are regulated by reciprocal interactions between sleep- and wake-regulatory neurons that are distributed throughout the brain (Saper and Fuller, 2017; Scammell et al., 2017; Weber and Dan, 2016). Nuclei regulating sleep comprise the preoptic area (POA), including the ventrolateral and median preoptic area, the lateral hypothalamus, and the parafacial zone in the brainstem (Anaclet et al., 2014; Kroeger et al., 2018; Sherin et al., 1996; Suntsova et al., 2002; Szymusiak et al., 1998; Takahashi et al., 2009). Conversely, wakefulness is thought to be regulated by arousal centers such as the histaminergic tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN), serotonergic dorsal raphe nuclei (DRN), the dopaminergic ventral tegmental area (VTA), and the noradrenergic locus coeruleus (LC) (Fig. 1), many of which innervate and inhibit sleep-active nuclei. While the interactions of these brain regions control sleep and wakefulness, the release of melatonin from the pineal gland regulates the timing of sleep onset.

Fig. 1.

Arousal centers in the brain

Wakefulness is regulated by arousal centers such as the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN), ventral tegmental area (VTA), raphe nuclei (RN) and locus coeruleus (LC) that synthesize unique monoamine neurotransmitters including histamine, dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine. Unlike the other neurotransmitters, dopamine neurons are active during wake and REM sleep, whereas others are active wake.

Understanding the neural circuit mechanisms underlying sleep and wake regulation and how they become dysfunctional in children with ASD will provide invaluable insights to discover novel therapeutic strategies to improve sleep and the quality of life in patients and their families. The following sections will highlight neuromodulatory systems controlling sleep and wakefulness, in particular norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, histamine, and melatonin, and how they are impaired in animal models and patients with ASD. Table 1 summarizes the mechanisms of action and effects on sleep for selected receptors that we discuss in this section.

Table 1.

Ligands of G protein-coupled receptors and their effect on sleep.

| Receptor | Downstream Effector | Ligand | Action | Effect on Sleep | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin Receptor | |||||

| MT2 receptor | Gi | UCM924 | Partial Agonist | Reduced NREM latency and increased NREM episode duration in rats | Ochoa-Sanchez et al. (2014) |

| IIK7 | Full Agonist | Reduced NREM latency and increased NREM episode duration in rats | Fisher and Sugden (2009) | ||

| Norepinephrine Receptors | |||||

| α2-adrenoceptor family | Gi | Clonidine | Partial agonist | Reduced REM; Increased NREM delta power sleep in cats | Crochet and Sakai (1999) |

| Reduced REM sleep in cats | Tononi et al. (1991) | ||||

| Reduced REM sleep in humans | Nicholson and Pascoe (1991) | ||||

| Reduced REM sleep in humans | Spiegel and DeVos (1980) | ||||

| Detomidine | Full Agonist | Reduced REM sleep in rats; increased NREM delta power | Hayat et al. (2020) | ||

| Serotonin Receptors | |||||

| 5-HT6 | Gs | WAY-208466 | Full Agonist | Increased wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM in rats (systemic); Reduced REM in rats (intracranial into DRN) |

Monti et al. (2013) |

| 5-HT2 family | Gq | RO-600175 | Full Agonist | Increased wakefulness; reduced NREM and REM sleep in rats (intracranial into DRN) | Monti and Jantos (2015) |

| Ritanserin | Antagonist | Increased NREM sleep in rats | Dugovic and Wauquier (1987) | ||

| Increased NREM sleep in humans | Idzikowski et al. (1986) | ||||

| Increased wakefulness in cats | Sommerfelt and Ursin (1993) | ||||

| 5-HT1A | Gi | 8-OH-DPAT | Full agonist | Increased wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM sleep in rats (systemic) | Dzoljic et al. (1992) |

| Increased NREM sleep, reduced wakefulness in rats (intracranial into DRN) | Monti and Jantos (1992) | ||||

| Increased wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM sleep in rats (systemic) Increased REM sleep in rats (intracranial into DRN) |

Bjorvatn et al. (1997) | ||||

| Ipsapirone | Partial agonist | Increased wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM sleep in rats (systemic) | Monti et al. (1995) | ||

| Increased wakefulness, reduced REM sleep in rats | Tissier et al. (1993) | ||||

| Reduced REM sleep in humans | Driver et al. (1995) | ||||

| Increased NREM EEG delta power in humans | Seifritz et al. (1996) | ||||

| Buspirone | Partial agonist | Increased wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM sleep in rats (systemic) | Monti et al. (1995) | ||

| Increased wakefulness in rats at 3 mg/kg (systemic) Increased wakefulness, abolished REM in rats at 10 mg/kg (systemic) |

Lerman et al. (1986) | ||||

| Gepirone | Partial agonist | Increased wakefulness, reduced NREM and REM sleep in rats (systemic) | Monti et al. (1995) | ||

| Histamine Receptors | |||||

| H1 | Gq | Doxepin | Antagonist | Increased NREM sleep in mice | Y.-Q. Wang et al. (2015) |

| Diphenhydramine | Antagonist | Increased NREM sleep in mice | Y.-Q. Wang et al. (2015) | ||

| Triprolidine | Antagonist | Increased NREM sleep in mice | Parmentier et al. (2016) | ||

| H3 | Gi | Pitolisant | Inverse agonist | Prevents excessive daytime sleepiness in narcoleptic patients | Dauvilliers et al. (2019) |

3.1. Melatonin

Melatonin is a neurohormone synthesized and released in the pineal gland that regulates circadian rhythms of sleep-wake timing and body temperature. Melatonin is secreted in a circadian fashion and is entrained by light exposure: secretion increases at the start of the evening, peaks in the middle of the night (around 3:00 a.m.), and decreases during the early morning (Grivas and Savvidou, 2007). The hypnotic effects of melatonin are thought to occur through activation of the melatonin (MT) receptors: activation of the MT1 receptors is implicated in the regulation of REM sleep and MT2 receptors are involved in regulating NREM sleep (Fisher and Sugden, 2009; Gobbi and Comai, 2019; Ochoa-Sanchez et al., 2011) (Fig. 2A). In particular, knockout mice lacking the MT1 receptors displayed reductions in REM sleep and theta power in the EEG during REM sleep, whereas MT2 receptor knockout mice displayed decreased NREM sleep and delta power in the EEG during NREM sleep (Comai et al., 2013). Furthermore, systemic injections of the selective MT2 receptor partial agonist, UCM924, or agonist, IIK7, in rats reduced the latency to NREM sleep and increased the duration of NREM sleep episodes (Fisher and Sugden, 2009; Ochoa-Sanchez et al., 2014). MT2 receptors are located in NREM sleep-active regions, including the reticular thalamus and preoptic areas, which could explain their role in NREM sleep regulation (Lacoste et al., 2015; Ochoa-Sanchez et al., 2011). Nonetheless, the exact circuit mechanisms by which melatonin promotes different aspects of sleep remain to be elucidated (Gobbi and Comai, 2019).

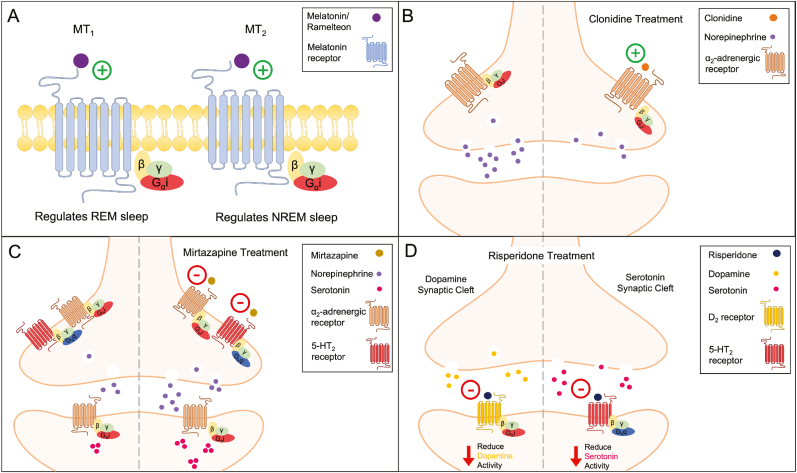

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of Action for Sleep Therapeutics

A. Melatonin and Ramelteon are agonists (plus) on melatonin (MT) receptors. Activation of the Gi coupled MT receptors promotes sleep, with distinct activation of the different subtypes promoting either REM or NREM sleep.

B. Clonidine is a partial agonist (plus) on α2-adrenergic receptors. Activation of these Gi coupled auto-receptors reduces norepinephrine from the synapse.

C. Mirtazapine is an antagonist (negative) on α2-adrenergic and 5-HT2 receptors. Inhibition of the α2-adrenergic auto-receptors increases norepinephrine release from the synapse. In turn, this increase in norepinephrine activates postsynaptic α2-adrenergic receptors on serotonin neurons resulting in elevated serotonin levels.

D. Risperidone is an antagonist (negative) on D2 and 5-HT2 receptors. Inhibition of both Gi coupled receptors reduces dopamine and serotonin levels.

Numerous studies indicate that patients with ASD have abnormal levels of melatonin throughout the day, compared with peers, which may contribute to sleep disturbances (Goldman et al., 2014; Melke et al., 2008; Rossignol and Frye, 2011; Tordjman et al., 2005; Veatch et al., 2015b). In particular, one study reported that adult FXS patients have decreased levels of melatonin (O'hare et al., 1986), which is in contrast to another study reporting increased levels of melatonin in children and adolescence with FXS (Gould et al., 2000). A potential cause for these abnormal levels of melatonin in patients with ASD could be due to mutations of key enzymes in the biosynthesis pathway of melatonin. A genetic screening study demonstrated that the transcript level of acetylserotonin methyltransferase, the last enzyme in the synthesis of melatonin, is reduced in patients with ASD (Melke et al., 2008). Furthermore, patients with ASD demonstrate lower daytime and nocturnal excretion of 6-sulfatoxymelatonin, the main metabolite of melatonin in urine (Tordjman et al., 2005, 2012). An additional cause for these alterations in melatonin level could also be from differences in secretion. It was shown that low melatonin levels observed in ASD patients were positively correlated with decreased volume of the pineal gland (Maruani et al., 2019). Dim light melatonin onset (DLMO) refers to the time in which salivary concentrations of melatonin start to rise, typically occurring 2–3 h before sleep onset (Burgess and Fogg, 2008; Pandi-Perumal et al., 2007; Yavuz-Kodat et al., 2020). Previous studies of patients with ASD did not find differences in DLMO (Goldman et al., 2017), whereas one study found more variability in patients with ASD compared to TD peers (Baker et al., 2017). These findings are in contrast to a more recent study demonstrating that patients with ASD had delayed DLMO (Martinez-Cayuelas et al., 2023). These discrepant results could be due to the inclusion criteria of participants. The former studies focused on adults and adolescents who were taking medications whereas the latter study investigated DLMO in children and adolescents without pharmacological treatment for ASD symptoms. Nonetheless, it remains to be investigated whether abnormal levels of melatonin are caused by impairment in the biosynthesis and/or secretion of melatonin throughout development in patients with ASD.

3.2. Norepinephrine

The locus coeruleus (LC) is the primary site for the synthesis of norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) in the brain and its neurons project throughout the brain (Plummer et al., 2020; Waterhouse et al., 2022). Noradrenergic LC neurons are well characterized for their roles in regulating arousal and related behaviors (Poe et al., 2020). They are most active during wakefulness, particularly in response to salient, novel, or stressful stimuli, less active during NREM sleep and silent during REM sleep (Antila et al., 2022; Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981; Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005; Berridge et al., 2012; Bouret and Sara, 2004; Chandler et al., 2019; Clayton et al., 2004; Eschenko and Sara, 2008; Jacobs, 1986; Kjaerby et al., 2022; McCall et al., 2015; Osorio-Forero et al., 2021; Poe et al., 2020; Rajkowski et al., 1994; Rasmussen et al., 1986; Sara, 2009; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008; Vankov et al., 1995; Zitnik, 2016).

Recent studies have identified the role of noradrenergic LC neurons in regulating the sleep microarchitecture (Antila et al., 2022; Kjaerby et al., 2022; Osorio-Forero et al., 2021). During NREM sleep, the noradrenergic LC neurons are rhythmically activated in synchrony with an infraslow (∼minute) rhythm in the spindle band (10–15 Hz) of the EEG (Lecci et al., 2017), and their activation is accompanied by microarousals (MAs) and suppression of sleep spindles (Antila et al., 2022; Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981; Kjaerby et al., 2022; Swift et al., 2018). Opto- or chemogenetic activation of the noradrenergic LC neurons leads to transitions from NREM sleep to arousals, as well as a suppression of sleep spindles and REM sleep (Antila et al., 2022; Carter et al., 2010; Kjaerby et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2021; Osorio-Forero et al., 2021; Swift et al., 2018; Yamaguchi et al., 2018). In contrast, opto- or chemogenetic inhibition of noradrenergic LC neurons increase NREM sleep and sleep spindles (Carter et al., 2010; Kjaerby et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2021; Osorio-Forero et al., 2021; Yamaguchi et al., 2018). Injection of α2-adrenergic receptor agonists, including clonidine and detomidine, led to a decrease in REM sleep in cats (Crochet and Sakai, 1999; Tononi et al., 1991), rats (Hayat et al., 2020), and humans (Nicholson and Pascoe, 1991; Spiegel and DeVos, 1980) as well as an increase in delta power during NREM sleep (Crochet and Sakai, 1999; Hayat et al., 2020; Tononi et al., 1991). These findings demonstrate a significant role of the LC in regulating arousal as well as the sleep microarchitecture.

The noradrenergic system is thought to be dysregulated in patients with ASD (London, 2018). Serum norepinephrine levels are higher in ASD compared with TD children (Lake et al., 1977). Furthermore, dysregulation of the noradrenergic system has been shown to modulate attentional deficits in children with ASD (Bast et al., 2018). In particular, nighttime awakenings, delayed sleep onset, and insomnia were attenuated after clonidine administration (further described in section IV) indicating that heightened noradrenergic signaling may contribute to sleep problems in children with ASD (Ingrassia and Turk, 2005; Ming et al., 2008; Schnoes et al., 2006). Notably, a decrease in sleep spindle activity has been reported in ASD. Polysomnography studies show that adolescents with ASD exhibit fewer sleep spindles during N2 NREM sleep (Limoges et al., 2005), a lower amplitude and intensity of fast sleep spindles (Merikanto et al., 2019), and disrupted coordination between cortical slow-oscillations and sleep spindles, which is a measure of thalamocortical communication (Mylonas et al., 2022). Given the important role of the LC in regulating spindles, it remains to be determined whether the decrease in sleep spindles in children with ASD is due to elevated noradrenaline levels. In 16p11.2 ± mouse model of ASD, innervation of noradrenergic fibers is significantly reduced in the motor cortex, and pharmacogenetic activation of LC-NE neurons was shown to rescue their delayed motor learning (Yin et al., 2021). It remains to be investigated whether changes in noradrenergic signaling contribute to sleep disturbances in 16p11.2 deletion mice. These findings provide insights into a potential role of the LC noradrenergic system in regulating sleep problems and related symptoms in children and animal models with ASD.

3.3. Serotonin

The largest group of serotonergic neurons is found in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN). Early electrophysiology studies in cats demonstrated that most serotonergic DRN neurons exhibit the highest activity during wakefulness and become less active during NREM sleep and nearly silent during REM sleep (Cespuglio et al., 1981; Lydic et al., 1987; McGinty and Harper, 1976; Puizillout et al., 1979; Trulson and Jacobs, 1979). Microdialysis studies in freely moving rats and cats showed that serotonin levels in the brain are highest during waking, lower during NREM sleep, and lowest during REM sleep (Portas et al., 1996, 1998; Portas and McCarley, 1994). These findings have been confirmed by fiber photometry recordings (Oikonomou et al., 2019). Pharmacological manipulations of the serotonin system have demonstrated a direct role of serotonin in sleep and wakefulness (full review Portas and Grønli, 2008, summarized in Table 1). Systemic or intracranial injections of the serotonin receptor 6 (5-HT6) agonist WAY-208466 or 5-HT2C receptor agonist RO-600175 into the DRN of rats increased wakefulness and reduced NREM and REM sleep (Monti et al., 2013; Monti and Jantos, 2015). In contrast, ritanserin, an antagonist of 5-HT2 receptors, promoted sleep in both humans and rats, but induced wakefulness in cats (Dugovic and Wauquier, 1987; Idzikowski et al., 1986; Sommerfelt and Ursin, 1993). Agonists of 5-HT1A receptors decreased wakefulness when injected into the DRN, but increased wakefulness when injected systemically. These conflicting results could be due to differences in the receptor expression between the various species or the delivery method of drugs (systemic versus intracranial), given that a variety of serotonin receptors are broadly distributed in the gastrointestinal tract (Mawe and Hoffman, 2013). Optogenetic manipulation and in vivo electrophysiological recordings were used to investigate the role of serotonin neurons in regulating sleep and wakefulness. Long term (1 h) optogenetic stimulation of serotonergic DRN neurons reduced NREM sleep and increased wakefulness (Ito et al., 2013). Serotonergic DRN neurons have different firing patterns, including tonic (∼1–6 Hz) (McGinty and Harper, 1976) and burst (up to ∼30 Hz) activity depending on whether animals are exposed to rewards, aversive stimuli, or motor tasks (Cohen et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2014; Schweimer and Ungless, 2010; Veasey et al., 1995). Tonic optogenetic stimulation (3 Hz) of serotonergic DRN neurons in mice enhanced NREM sleep, whereas burst stimulation (25 Hz) increased wakefulness. Both stimulation protocols reduced REM sleep (Oikonomou et al., 2019). These findings demonstrate that serotonergic DRN neurons have distinct effects on sleep and wakefulness depending on their activity pattern.

Many studies suggest a link between serotonin and ASD (Muller et al., 2016). Elevated levels of serotonin in the blood were observed in ASD patients (Schain and Freedman, 1961). Hyperserotonemia, a condition in which blood serotonin levels are above the 95th percentile of normal levels, is estimated to be present in more than 25–30% of the ASD population (Gabriele et al., 2014; Hranilovic et al., 2007; Mulder et al., 2004). Compared with siblings, patients with ASD have elevated levels of serotonin in the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum and lower levels in the thalamus and frontal cortex (Chugani et al., 1997). Postmortem studies found that both 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A receptors along with the serotonin transporter, SERT, have decreased affinity for serotonin binding in ASD patients (Makkonen et al., 2008; Nakamura et al., 2010; Oblak et al., 2013). Furthermore, genetic studies in patients with ASD have identified polymorphisms in genes involved in the synthesis of serotonin, serotonin transporters, and serotonin receptors (Anderson et al., 2009; Devlin et al., 2005). A study in mice further supports these findings: The SERT amino acid variant, Ala56, induced hyperserotonemia in mice and increased repetitive behavior while reducing social behavior (Veenstra-VanderWeele et al., 2012). Recent studies have begun linking genetic mutations of the serotonin system with sleep disturbances in ASD patients and hyperserotonemia, suggesting a role of serotonin in sleep problems of ASD. Large-scale exome sequencing data show that mutations in the genes, chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein-8 (CHD8) and protein-7 (CHD7) are leading risk factors for ASD, and individuals with mutations in these genes suffer from difficulties with sleep initiation and maintenance (Bernier et al., 2014; Coll-Tané et al., 2021; Cotney et al., 2015; Satterstrom et al., 2020; Stessman et al., 2017). Knock-down of the CHD8/CHD7 ortholog, kismet, in Drosophila decreased sleep maintenance and led to a hyperserotonemia state, both of which are phenotypes that are also observed in patients with ASD (Coll-Tané et al., 2021). Furthermore, kismet mutants treated with α-methyl-DL-tryptophan (αMTP), a serotonin synthesis inhibitor, throughout development rescued sleep fragmentation (Coll-Tané et al., 2021). Shank3 deficient mice have higher mRNA levels of SERT in the hippocampus, hypothalamus, and frontal cortex at P5. In adult mice, the expression of SERT is significantly higher than WT mice in the hippocampus but significantly lower in the frontal cortex (Bukatova et al., 2021), suggesting altered serotonergic neurotransmission occurs during development in Shank3 deficient mice. Furthermore, in 16p11.2 deletion mice, dysregulation of the serotonergic system was shown to contribute to hyperactivity, reduced sociability and coping response to acute stress (Mitchell et al., 2020; Panzini et al., 2017). The role of serotonergic transmission in sleep disturbances in these animal models remains to be investigated. Together, these results provide important insights into our understanding of the role of the serotonergic system in sleep problems of ASD.

3.4. Dopamine

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter produced mainly in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra (SN) (Björklund and Dunnett, 2007). Initial electrophysiological recordings in cats and rats demonstrated that the activity of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA and SN is highest during periods of active wakefulness and lower during sleep (Miller et al., 1983; Steinfels et al., 1983; Trulson et al., 1981; Trulson and Preussler, 1984). Genetically modified mice with a deletion of the dopamine transporter (DAT) gene show a reduction in NREM sleep and an increase in wakefulness (Wisor et al., 2001). More recent studies have demonstrated that dopaminergic neurons play an important role in regulating REM sleep (Hasegawa et al., 2022; Monti and Monti, 2007). Acute pharmacological depletion of dopamine levels suppressed NREM sleep and abolished REM sleep (Dzirasa et al., 2006). More recent electrophysiological recordings of dopaminergic VTA neurons demonstrated a burst firing activity during REM sleep (Dahan et al., 2007). These findings were further supported by fiber photometry recordings, which demonstrated that dopaminergic VTA neurons are most active during REM sleep, less active during wakefulness and least active during NREM sleep (Eban-Rothschild et al., 2016). Chemogenetic activation of dopaminergic VTA neurons promoted sustained wakefulness while optogenetic activation induced a rapid transition from sleep to wakefulness (Eban-Rothschild et al., 2016; Oishi et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2017). In contrast, chemogenetic inhibition of dopaminergic VTA neurons promoted sleep (Eban-Rothschild et al., 2016). The dopaminergic VTA neurons regulate REM sleep through various projection targets including the nucleus accumbens (NAc), prefrontal cortex (PFC), and basolateral amygdala (BLA). Using microdialysis in freely moving rats, it was demonstrated that extracellular dopamine levels increased in the NAc and PFC during REM sleep and wake; whereas other neurotransmitters including norepinephrine and glutamate only slightly increased during wake (Léna et al., 2005). Moreover, a recent study using a genetically encoded dopamine sensor demonstrated an increase of dopamine in the NAc during REM sleep but not in the PFC (Hasegawa et al., 2022). Furthermore, dopamine levels in the BLA began to increase prior to the onset of REM sleep and optogenetic activation of VTA dopaminergic projections to the BLA during NREM sleep promoted REM sleep, suggesting that dopaminergic transmission in the BLA plays a pivotal role in transitions to REM sleep (Hasegawa et al., 2022). Lastly, it has been demonstrated that NREM to REM sleep transitions are facilitated by BLA neurons containing the dopamine D2 receptors, as optogenetic inhibition of these neurons increased REM sleep initiation (Hasegawa et al., 2022).

The dopaminergic system is believed to be highly associated with ASD, in particular social deficits (Pavăl, 2017). Human studies demonstrated that genetic mutations of the dopaminergic system, including DAT (Bowton et al., 2014; Hamilton et al., 2013), dopamine receptors (de Krom et al., 2009; Hettinger et al., 2008; Mariggiò et al., 2021), and enzymes of dopamine biosynthesis (Nguyen et al., 2014), are implicated in ASD. Mice with increased neurotransmission of dopamine in the dorsal striatum due to suppression of DAT within the SN promotes autistic-like behaviors such as sociability deficits and repetitive behaviors (Lee et al., 2018). Clinical studies using positron emission tomographic (PET) scanning demonstrated a lower dopaminergic activity in the medial prefrontal cortex of children with ASD suggesting dysfunction of the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic system, a circuit involved in reward processing (Ernst et al., 1997). Furthermore, a functional MRI (fMRI) study demonstrated that the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system is less active in response to monetary incentives in patients with ASD (Dichter et al., 2012a; Dichter et al., 2012b). Many studies support that the dopaminergic system contributes to sleep disturbances in ASD. The gene SLC6A3, which encodes DAT, is a risk gene for both ASD and sleep disorders (Abel et al., 2020). Additionally, restless leg syndrome, often a comorbidity with ASD that may contribute to insomnia, was found to be associated with decreased levels of D2 receptors in the putamen (Kanney et al., 2020; Veatch et al., 2015a). Recently, it has been shown that the dopaminergic system plays a critical role in the development of social interactions in mice as disruption of sleep during adolescence in mice reduces social novelty preference and novelty-dependent responses in dopaminergic VTA neurons in adulthood (Bian et al., 2022). Furthermore, social deficits in Shank3 mutant mice were rescued if NREM sleep was increased either by injections of flupirtine, a selective KCNQ2/KCNQ3 potassium channel opener, or chemogenetic inhibition of dopaminergic VTA neurons during adolescence (Bian et al., 2022). These findings provide an important insight into how dopamine contributes to shape sleep and social interactions during adolescence and how the dopaminergic system becomes dysfunctional in the Shank3 mutant mouse model of ASD.

3.5. Histamine

Histamine is a wake-promoting neurotransmitter found primarily in neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) (Panula et al., 1984; Watanabe et al., 1983, 1984). In mice, histaminergic TMN neurons are most active during wakefulness, in particular during active wake, less active during drowsy states and NREM sleep, and silent during REM sleep (John et al., 2004; Takahashi et al., 2006). Pharmacological studies on histamine receptors also support a role of histamine in wakefulness. Histamine H1 receptor antagonists such as doxepin, diphenhydramine, and triprolidine have been shown to promote NREM sleep in mice (Parmentier et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2015). Pitolisant, an inverse agonist for the histamine H3 auto-receptor, is used to prevent excessive daytime sleepiness in narcoleptic adult patients due to its unique mechanism of action which increase synthesis and release of histamine (Dauvilliers et al., 2013, 2019; Syed, 2016; Szakacs et al., 2017). Chemogenetic activation of histaminergic neurons promotes wakefulness (Yu et al., 2015), while optogenetic inhibition increases NREM sleep (Fujita et al., 2017).

Previous studies suggest that the histaminergic system is dysregulated in ASD. Postmortem brains from patients with ASD showed altered gene expression of histamine N-methyltransferase (HMT), an enzyme involved in the metabolism of histamine, and histamine receptors (H1,H2, and H3) in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Wright et al., 2017). A recent study reported higher plasma histamine levels in children with ASD compared with TD peers (Rashaid et al., 2022). In a rodent model of ASD and children with ASD, histamine antagonists alleviated ASD symptoms, which further supports a link between histamine and ASD. Specifically, ciproxifan, an H3 antagonist ameliorated social interaction deficits and repetitive behaviors observed in the valproic acid-induced mouse model of ASD (Baronio et al., 2015; Taheri et al., 2022). Furthermore, famotidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, and cyproheptadine, an H1 receptor inverse agonist, have been reported to alleviate irritability, lethargy, hyperactivity, and social withdrawal in children with ASD (Akhondzadeh et al., 2004; Linday et al., 2001). While the role of histamine signaling in sleep disturbances of ASD patients or animal models has not been investigated yet, histamine receptor antagonists have been shown to reduce hyperactivity in mouse models of ASD. Pitolisant reduced hyperactivity (Meyza and Blanchard, 2017), while ciproxifan had no effect (Molenhuis et al., 2022) in the BTBR T + Itpr3tf/J mouse model of ASD that exhibits reduced social interactions and repetitive behaviors (Babineau et al., 2013; McFarlane et al., 2008; Silverman et al., 2010). However, in a valproic acid-induced ASD mouse model that was shown to exhibit sleep disturbances (Cusmano and Mong, 2014; Tsujino et al., 2007), DL77, an H3 receptor antagonist, had no effect on hyperactivity (Eissa et al., 2018). Nonetheless, while these studies suggest that antagonizing histamine neurotransmission can improve autism-like phenotypes in these mouse models of ASD, it remains unknown whether the quality of sleep in these mice is also improved.

4. Therapeutics for sleep disturbances in ASD

To date, there are no therapeutic sleeping aids approved by the FDA to attenuate sleep disturbances in children with ASD. The neural mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances in children with ASD are not fully understood, making it challenging to develop targeted therapeutics. In addition, careful considerations on dosing, tolerance, and adverse side effects need to be considered in developing therapeutics for pediatric patient populations. Nonetheless, a common side-effect of therapeutics used to treat stereotypic ASD behavior is sedation. These include FDA approved therapeutics for ADHD, depression, anxiety, irritability and aggression, and none of these drugs are approved for improving sleep. Additionally, sleep promoting agents have been prescribed off-label for this population. It is estimated that 38% of pediatricians recommend sleep therapeutics to children with ASD that experience insomnia, sleep onset delay, or night awakenings (Owens et al., 2003). Behavioral interventions such as education on sleep hygiene and positive reinforcement for sleep behavior are also recommended to be used as a first-line approach prior to pharmacological interventions to treat sleep disturbances in children with ASD (Malow et al., 2012, Malow et al., 2012). The following sections and Table 2 summarize pharmacological approaches to attenuate sleep disturbances in pediatric patients with ASD. Many of these studies are case studies that rely on anecdotal accounts from parents or patients, and are complicated further by different therapeutic regimens to treat ASD symptoms. Given the lack of rigorous controlled clinical trials, careful considerations are required to interpret the findings from these case studies.

Table 2.

Therapeutics for sleep disturbances in ASD.

| Ligand | Primary Target (s) | Type | Action | Participants | Effect on Sleep | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin Agonists | ||||||

| Melatonin | MT1 receptor MT2 receptor |

Agonist | Full Agonist | n = 107; 2–18 year olds with ASD | Improved sleep in 60% of participants | Andersen et al. (2008) |

| n = 146; 3–15 year olds with NDD, including ASD | Improved total sleep time, reduced sleep latency | Gringras et al. (2012) | ||||

| n = 24; 3–10 year olds with ASD, AS, PDD, PDD-NOS | Reduced sleep latency | Malow et al. (2012) | ||||

| n = 22; 3–16 year olds with ASD | Reduced sleep latency, improved sleep duration; no reduction in night awakenings | Wright et al. (2011) | ||||

| n = 12; 2–15 year olds with ASD, FXS, ASD + FXS, FX premutation | Reduced sleep latency, improved sleep duration, no difference in night awakenings, earlier bedtimes | Wirojanan et al. (2009) | ||||

| n = 11*; 4–16 year olds with ASD | Reduced sleep latency, improved total sleep time; reduced number of night awakenings. *Discontinued at 7 participants when discovered placebo capsules were empty |

Garstang and Wallis, 2006 | ||||

| n = 9; 2–11 year olds with ASD | Reduced sleep latency, improved total sleep duration | Gupta and Hutchins (2005) | ||||

| n = 9; 4–17 year olds with RS | Reduced sleep latency, improved total sleep time, sleep efficiency | McArthur and Budden (1998) | ||||

| n = 6; 19–52 year olds with ASD | Reduced sleep latency, night awakenings; increased total sleep time | Galli-Carminati et al. (2009) | ||||

| n = 2; 7, 13 year old with RS | Reduced sleep latency, improved sleep maintenance | Miyamoto et al. (1999) | ||||

| n = 1; a 17 year old with AS | Improved sleep maintenance; minimized night awakenings | Horrigan and Barnhill (1997) | ||||

| n = 1; a 10 year old with RS | Reduced sleep latency; reduced night awakenings | Yamashita et al. (1999) | ||||

| n = 1; a 14 year old with ASD | Improved sleep duration, daily sleep-wake rhythm | Hayashi (2000) | ||||

| n = 1, a 12 year old with AS | Reduced sleep latency; reduced night terrors, night awakenings | Bottanelli et al. (2004) | ||||

| Melatonin-CR | MT1 receptor MT2 receptor |

Agonist | Full Agonist | n = 160, 4–10 year olds with ASD | Reduced sleep latency, improved total sleep time; reduced night awakenings | Cortesi et al. (2012) |

| n = 50, 2–18 year olds with NDD including ASD (cross-over trial) | Improved total sleep duration, reduced sleep latency | Wasdell et al. (2008) | ||||

| n = 47, 2–18 year olds with NDD including ASD (open-label phase) | Improved sleep efficiency, longer sleep episodes | Wasdell et al. (2008) | ||||

| n = 25; 2–9 year olds with ASD | Improved sleep onset, sleep duration, night-time awakenings, parasomnias and daytime sleepiness | Giannotti et al. (2006) | ||||

| Melatonin-PedPRM | MT1 receptor MT2 receptor |

Agonist | Full Agonist | n = 125, 2–17 year olds with ASD (96.8%) or SMS (3.2%) | Improved total sleep time, reduced sleep latency; reduced sleep disturbances | Gringras et al. (2017) |

| n = 125, 2–17 year olds with ASD (96.8%) or SMS (3.2%) | Improved sleep duration, reduced sleep latency | Schroder et al. (2019) | ||||

| n = 95, 2–17 year olds with ASD, neurogenic disorders | Improved total sleep time, reduced sleep latency, improved sleep quality; reduced night awakenings | Maras et al. (2018) | ||||

| n = 80, 2–17 year olds with ASD (96%) or SMS (4%) | Improved sleep disturbances, quality of sleep, caregiver satisfaction with children sleep patterns | Malow et al. (2021) | ||||

| Ramelteon | MT1 receptor MT2 receptor |

Agonist | Full Agonist | n = 3; 9–12 year olds with ASD | Improved latency to persistent sleep, total sleep time | Kawabe et al. (2014) |

| n = 2; 7, 18 year olds with ASD | Reduced sleep latency, improved sleep maintenance; reduced night awakenings | Stigler et al. (2006) | ||||

| α-Agonists | ||||||

| Clonidine | α2A-adrenoreceptor α2B-adrenoreceptor |

Agonist | Partial agonist | n = 19; 4–16 year olds with ASD, PDD, AS | Reduced sleep latency; reduced night awakenings | Ming et al. (2008) |

| n = 6; 6–14 year olds with ASD, PDD | Reduced sleep latency; Increased total sleep duration; reduced night awakenings | Ingrassia and Turk (2005) | ||||

| Guanfacine | α2A-adrenoreceptor α2B-adrenoreceptor α2C-adrenoreceptor |

Agonist Agonist Agonist |

Partial agonist Full Agonist Partial agonist |

n = 80; 3–18 years old with ASD, AS, PDD-NOS | Improved insomnia in 24% of patients | Posey et al. (2004) |

| Guanfacine-ER | α2A-adrenoreceptor α2B-adrenoreceptor α2C-adrenoreceptor |

Agonist Agonist Agonist |

Partial agonist Full Agonist Partial agonist |

n = 62; 5–14 year olds with ASD | No effect | Politte et al. (2018) |

| n = 1; 10 year old with ASD | Reduced sleep latency, improved sleep maintenance | Propper (2018) | ||||

| Antihistamines | ||||||

| Niaprazine | H1 receptor 5-HT2 receptor α1-adrenoreceptor |

Antagonist | – | n = 25; 2–20 year olds with ASD | Improved sleep disorders in 52% of patients | Rossi et al. (1999) |

| Antidepressants | ||||||

| Mirtazapine | α2C-adrenoreceptor α2A-adrenoreceptor α2B-adrenoreceptor 5-HT2C receptor 5-HT2A receptor |

Antagonist | – | n = 26; 3–23 year olds with ASD, AS, RS, PDD | Improved sleep quality | Posey et al. (2001) |

| n = 26; 5–17 year olds with ASD | No reduction in problematic sleep habits compared to placebo | McDougle et al. (2022) | ||||

| n = 1; 13 year old with ASD | Improved sleep | Nguyen and Murphy (2001) | ||||

| n = 1; 13 year old with ASD | Reduced sleep latency | Coskun and Mukaddes (2008) | ||||

| n = 1; 11 year old with ASD | Reduced sleep problems (combined with Aripiprazole) | Akbas and Akca (2018) | ||||

| n = 1; 15 year old with ASD | Improved sleep | Naguy et al. (2019) | ||||

| Trazodone | 5-HT2A receptor 5-HT2C receptor |

Antagonist | – | n = 1; 8 year old with ASD | Improved sleep | Rapin, 2001 |

| 1 year follow-up of Rapin (2001) | Continued to help with sleep | Parker and Hartman (2002) | ||||

| n = 1; 9 year old with AS | Reduced sleep latency | Bloomfield et al. (2015) | ||||

| Fluoxetine | SERT | Inhibitor | Inhibition | n = 1; 16 year old with ASD | Reduced insomnia | Cawkwell et al. (2016) |

| Fluvoxamine | SERT | Inhibitor | Inhibition | n = 1; 8 year old with AS | Reduced sleep disturbances | Furusho et al. (2001) |

| Paroxetine | SERT | Inhibitor | Inhibition | n = 1; 7 year old with ASD/PDD | Improved sleep | Posey et al. (1999) |

| Amitriptyline | H1 receptor M4 receptor M2 receptor M3 receptor M5 receptor SERT NET |

Antagonist Inhibitor |

– Inhibition |

n = 1; 6 year old with ASD | Improved sleep | Pollard and Prendergast (2004) |

| Antipsychotics | ||||||

| Risperidone | 5-HT2A receptor D2 receptor 5-HT1D receptor 5-HT1B receptor |

Antagonist | Inverse agonist – – – |

n = 56; 5–17 year olds with ASD | Improved sleep quality | Kent et al. (2013) |

| n = 23; 3–13 year olds with ASD, PDD-NOS, late-onset ASD | Improved sleep quality and/or duration | Capone et al. (2008) | ||||

| n = 11; 6–34 year olds with ASD | Reduced sleep latency, improved staying asleep | Horrigan and Barnhill (1997) | ||||

| n = 11; 7–17 year olds with ASD, PDD-NOS | Reduced sleep disturbances | Zuddas et al., 2000 | ||||

| n = 6; 3–13 year olds with ASD | Reduced sleep disturbances | Vercellino et al. (2001) | ||||

| n = 1; 16 year old with ASD | Upon withdrawal of risperidone, sleep worsened | Feroz-Nainar et al. (2006) | ||||

| n = 1; 10 year old with ASD | Improved sleeping throughout the night | Ivanov et al. (2006) | ||||

| n = 1; 3 year old with PDD | Improved sleep; reduced night awakenings | Doan (1998) | ||||

| n = 1; 5 year old with ASD | Improved sleep | Demb (1996) | ||||

| Aripiprazole | D2 receptor | Agonist | Partial Agonist | n = 32; 5–19 year olds with ASD | Improved sleep in 4/9 with sleep disorders | Valicenti-McDermott and Demb (2006) |

| n = 5; 5–18 year olds with PDD | Improved sleep | Stigler et al. (2004) | ||||

| n = 1; 11 year old with ASD | Reduced sleep problems (combined with Mirtazapine) | Akbas and Akca (2018) | ||||

| Quetiapine | D2 receptor 5-HT2A receptor |

Antagonist | – | n = 11; 13–17 year olds with ASD | Improved sleep disturbances, sleep quality | Golubchik et al. (2011) |

| n = 1; 16 year old with PDD-NOS | Improved sleep during manic state | Vijapura et al. (2014) | ||||

| n = 1; 17 year old with ASD | Improved sleep | Tufan and Kutlu (2009) | ||||

| Ziprasidone | 5-HT2A receptor D2 receptor 5-HT2C receptor |

Antagonist | – – Inverse agonist |

n = 1; 7 year old with ASD | Improved sleep pattern | Goforth and Rao, 2003 |

| Olanzapine | 5-HT2A receptor D2 receptor 5-HT2C receptor |

Antagonist | – – Inverse agonist |

n = 1; 6 year old with ASD | Improved sleep | Hergüner (2010) |

AS: Asperger's Syndrome; PDD: Pervasive Developmental Disorders; PDD-NOS: PDD-Not Otherwise Specified; FXS: Fragile-X Syndrome; RS: Rett-Syndrome; NDD: Neurodevelopmental Disorders; CR: Controlled-Release; PedPRM: Pediatric Prolonged Release Melatonin; SMS: Smith-Magenis Syndrome; ER: Extended Release; M# receptor: Acetylcholine receptor; D# receptor: Dopamine receptor.

4.1. Melatonin analogues

Despite melatonin being a natural supplement that is widely used with low safety concerns, it is not approved by the FDA. Many pediatricians and child psychiatrists recommend melatonin for sleep problems in children, especially with ASD (Bramble and Feehan, 2005). Numerous studies indicate that melatonin improves sleep quality in ASD children by reducing the latency to sleep onset (Aathira et al., 2017; Galli-Carminati et al., 2009; Garstang and Wallis, 2006; Gringras et al., 2012; Gupta and Hutchins, 2005; Jan et al., 2004; Malow et al., 2012; McArthur and Budden, 1998; Miyamoto et al., 1999; Wirojanan et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2011; Yamashita et al., 1999), increasing total sleep duration (Galli-Carminati et al., 2009; Garstang and Wallis, 2006; Gringras et al., 2012; Gupta and Hutchins, 2005; Hayashi, 2000; McArthur and Budden, 1998; Wirojanan et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2011) and decreasing night awakenings (Galli-Carminati et al., 2009; Garstang and Wallis, 2006; Horrigan and Barnhill, 1997; Jan et al., 2004; Yamashita et al., 1999) (Table 2). In addition, controlled-release melatonin has also been successful in reducing sleep disturbances in ASD children. Specifically, this novel therapeutic strategy closely mimics the circadian rhythm of melatonin secretion, with a low dose immediately released and a higher dose released hours later. This type of dosing strategy has been shown to improve sleep onset and total sleep duration while decreasing the number of night awakenings (Cortesi et al., 2012; Giannotti et al., 2006; Wasdell et al., 2008). Studies have also investigated the efficacy and safety of a pediatric prolonged release-melatonin (PedPRM) formulation for children with ASD. PedPRM has been shown to significantly reduce sleep latency and enhance total sleep time, by increasing the duration of sleep episodes and decreasing brief awakenings (Gringras et al., 2017; Schroder et al., 2019). Moreover, long-term treatment of PedPRM (104 weeks) was effective in improving sleep and was well tolerated in pediatric ASD patients with no adverse effect on growth and development (Malow et al., 2021; Maras et al., 2018). In addition to improving sleep, children's disruptive behavior was reduced and the caregivers' quality of life was improved in the PedPRM treated group compared with the placebo-group (Schroder et al., 2019). Ramelteon, an analogue of melatonin that was developed to treat insomnia, was also effective in reducing the latency to sleep and night awakenings while increasing total sleep time in children with ASD (Kawabe et al., 2014; Stigler et al., 2006).

4.2. α2-adrenergic agonists

The α2-adrenergic receptors are auto-receptors that can be located both on the presynapse or postsynapse (Molinoff, 1984). When norepinephrine is released it can bind to presynaptic α2-adrenergic receptors to inhibit further release of norepinephrine (i.e. negative feedback). Agonists of the α2-adrenergic receptors are sympathomimetic agents often used to promote sedation, muscle relaxation, and as an analgesics (Khan et al., 1999). Agonists of α2-adrenergic receptors, such as clonidine (Fig. 2B) and guanfacine, have been used to manage the symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which is often a comorbidity with ASD (Connor et al., 2010; Fankhauser et al., 1992; Hazell, 2007; Jaselskis et al., 1992; Sallee et al., 2009; Wilens et al., 2012). The use of α2-adrenergic agonists in ASD children and adolescents has increased to improve sleep and anxiety symptoms (Fiks et al., 2015).

Clonidine, an anti-hypertensive therapeutic, is the most used medication within this drug class for treating sleep disturbances, including children with ASD (Schnoes et al., 2006) (Table 2). Clonidine decreased the time to fall asleep and helped children with neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD, pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs), and Asperger's syndrome (AS) to stay asleep (Ingrassia and Turk, 2005; Ming et al., 2008). Clonidine is generally well tolerated in children with few adverse side effects such as REM sleep suppression (Pelayo and Dubik, 2008).

The other α2-adrenergic agonist that has been shown to improve sleep in children with ASD is guanfacine (Politte et al., 2018; Posey et al., 2004; Propper, 2018). Guanfacine is a highly selective agonist of the α2A-adrenergic receptor that is used to improve attention in children with ADHD. In terms of its effect on improving sleep in children with ASD, guanfacine treatment led to mixed results. A retrospective study of children with neurodevelopmental disorders indicated that guanfacine attenuated insomnia in 24% of patients, in line with a case study reporting reduced sleep latency and enhanced maintenance (Posey et al., 2004; Propper, 2018). However, a placebo-controlled study did not find an improvement in sleep habits in children with ASD (Politte et al., 2018).

4.3. Antihistamines

First-generation antihistamines were primarily designed to treat allergic rhinitis and other allergies that induce atopic eczema or from food and insect stings. However, a common side-effect of these drugs is sedation due to their ability to readily cross the blood-brain barrier and inhibit H1 receptors in the CNS (Slater et al., 1999). For this reason, many of the common first-generation antihistamines have been repurposed for nighttime sleeping aids. In general, antihistamines are the most common drugs recommended by pediatricians to treat sleep disorders within the pediatric population (Owens et al., 2003; Schnoes et al., 2006).

Diphenhydramine is the most widely used non-prescription antihistamine for sleep disorders. However, the use of diphenhydramine to treat sleep disturbances led to mixed results. A study has shown that diphenhydramine reduced sleep latency, the number of nighttime awakenings, and slightly increased sleep duration in children with sleep disorders (Russo et al., 1976), while more recent studies have demonstrated that it is not effective in treating sleep disturbances (Merenstein et al., 2006; Paul et al., 2004). Nonetheless, the efficacy of diphenhydramine in improving sleep of children with ASD remains to be tested.

Niaprazine has been shown to be effective in treating sleep disturbances of children and adolescents (Montanari et al., 1992; Ottaviano et al., 1991). In particular, niaprazine improved sleep in 52% of children and adolescents with ASD suffering from sleep disorders (Rossi et al., 1999) (Table 2). However, the exact mechanism by which niaprazine promotes sleep is not clear. Although originally thought to act as an antihistamine, niaprazine has been shown to have only a low binding affinity to H1 receptors and is instead more potent as an antagonist of 5-HT2 receptors and α1-adrenoceptors, which may contribute to its sleep-promoting effects (Scherman et al., 1988).

4.4. Antidepressants

It is estimated that 50–69% of children and adolescents with ASD display symptoms of anxiety (Kerns et al., 2021; McDougle et al., 2022). A common treatment regimen for children with ASD to attenuate anxiety symptoms and repetitive behaviors includes the use of antidepressants (McDougle et al., 2022; Posey et al., 2001). Within some classes of antidepressant drugs, sedation is often a common side effect and therefore while not explicitly prescribed for sleep disturbances, antidepressants have shown promising effects in improving sleep disturbances. The effect of antidepressants in promoting sleep may be mediated by the serotoninergic system or a combination of serotonin and norepinephrine (Relia and Ekambaram, 2018).

Mirtazapine is an antidepressant that has been shown to improve sleep in children with ASD. Mirtazapine produces sedative and anxiolytic effects by increasing both norepinephrine and serotonin levels. Specifically, mirtazapine blocks 5-HT2 and α2-adrenergic receptors, leading to increased norepinephrine levels. Norepinephrine in turn activates α2-adrenergic receptors on serotonergic neurons resulting in elevated serotonin levels via disinhibition (Haddjeri et al., 1995; Schatzberg and DeBattista, 2019a) (Fig. 2C). An open-label study and several case reports have suggested that mirtazapine may be beneficial for treating sleep disturbances in children with ASD (Akbas and Akca, 2018; Coskun and Mukaddes, 2008; Naguy et al., 2019; Nguyen and Murphy, 2001; Posey et al., 2001). However, a recent randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study assessed sleep habits with the CSHQ in children with ASD and demonstrated that both mirtazapine and placebo groups reduced sleep problems (McDougle et al., 2022). Nonetheless, it is unclear if these improvements in sleep are indirectly mediated by the drug's effect on managing other behavioral symptoms such as anxiety or a direct effect on attenuating sleep disturbances.

Limited data also exists from clinical observations in case reports on the use of other antidepressants to improve sleep in children with ASD (Table 2). Low-doses of trazodone, a 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C antagonist, was shown to relieve symptoms of insomnia, in particular with individuals experiencing depression (Kasper et al., 2005; Munizza et al., 2006; Nierenberg et al., 1994). A case report detailed that trazodone improved sleep in a child with ASD and this improvement was maintained after a one year follow-up (Parker and Hartman, 2002; Rapin, 2001). Another case report demonstrated trazodone decreased sleep latency in a child with AS (Bloomfield et al., 2015). Trazodone has been reported to improve sleep in children with Angelman syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder that has high comorbidity and is often misdiagnosed as ASD (Pereira et al., 2020). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) antidepressants that inhibit the serotonin transporter, SERT, such as fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine improved sleep in children with neurodevelopmental disorders (Cawkwell et al., 2016; Furusho et al., 2001; Posey et al., 2006). Lastly, a case report suggested that amitriptyline improved sleep in a child with ASD (Pollard and Prendergast, 2004), but the exact mechanism is unclear given that this therapeutic inhibits both SERT and H1 receptors, among other targets (full list of targets in Table 2).

4.5. Antipsychotics

Given that symptoms in children with ASD include irritability, aggression, and self-injurious behavior, antipsychotics are often prescribed as an intervention to ameliorate these behaviors (Posey et al., 2008). While often prescribed for these behavioral symptoms, a secondary outcome is improved sleep. Antipsychotics are divided into typical and atypical; the former first-generation agents have an increased risk of tardive dyskinesia even after discontinuation of medication and were therefore replaced by atypical antipsychotics (Schatzberg and DeBattista, 2019a, Schatzberg and DeBattista, 2019b). Nonetheless, both groups of antipsychotics generally block the brain's dopaminergic system, particularly by antagonizing D2 receptors. This may lead to an increase in sleep, as D2 receptor knock-out mice sleep more, a phenotype that is mimicked in WT mice treated with the selective D2 receptor antagonist, raclopride (Qu et al., 2010).

Risperidone, which is used for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with ASD, has also been demonstrated to improve sleep. Risperidone is an antagonist of D2 and 5-HT receptors, including 5-HT2A, 5-HT1D, and 5-HT1B (Schotte et al., 1996) (Fig. 2D). Risperidone shares a similar pharmacological mechanism of action as mirtazapine, but also blocks the dopamine system, making it challenging to fully understand the sleep-promoting properties. Risperidone treatment in children with ASD was shown to decrease latency to fall asleep and increase the amount of sleep (Capone et al., 2008; Kent et al., 2013), which was further corroborated by other studies showing that risperidone attenuated sleep disturbances and reduced night awakenings (Demb, 1996; Doan, 1998; Horrigan and Barnhill, 1997; Ivanov et al., 2006; Vercellino et al., 2001; Zuddas et al., 2000). A case report noted that withdrawal of risperidone worsened sleep in a child with ASD, further supporting the effect of risperidone in improving sleep (Feroz-Nainar et al., 2006).

Aripiprazole, unlike other atypical antipsychotics, is a partial agonist of D2 receptors (Davies et al., 2004; Kikuchi et al., 1995) and used for the treatment of irritability in children with ASD. Studies suggest that aripiprazole can improve sleep in children with neurodevelopmental disorders (Stigler et al., 2004; Valicenti-McDermott and Demb, 2006). One case report demonstrated that aripiprazole in combination with mirtazapine reduced sleep problems in a child with ASD (Akbas and Akca, 2018). Finally, one study demonstrated that switching medication from risperidone to aripiprazole reduced daytime sleepiness in a few children with PDD, suggesting aripiprazole may be a suitable alternative if risperidone induces daytime sleepiness (Ishitobi et al., 2012).

The effects of atypical antipsychotics including quetiapine, ziprasidone, and olanzapine have been reported to improve sleep in children with ASD. Quetiapine, a D2 and 5-HT2A antagonist (Richelson and Souder, 2000), was shown to improve sleep quality in children with ASD (Golubchik et al., 2011). Additional case reports also indicate that quetiapine improved sleep in a child with ASD as well as a child with PDD-NOS during a manic state (Tufan and Kutlu, 2009; Vijapura et al., 2014). Lastly, ziprasidone and olanzapine, both of which are antagonists of 5-HT2A, D2, and 5-HT2C (Richelson and Souder, 2000), have been demonstrated to improve sleep in separate case reports (Hergüner, 2010; Goforth and Rao, 2003). While antipsychotics have been demonstrated to attenuate irritability and agitation in children with ASD, adverse side-effects need to be taken into consideration. A study found that compared with risperidone and aripiprazole, olanzapine treatment leads to more frequent side-effects in children with ASD, including 75% of participants experiencing sleepiness/sedation (Tural Hesapcioglu et al., 2020).

5. Conclusions

40–80% of children with ASD suffer from sleep problems and sleep disturbances have been suggested as a potential predictor of worsening core symptoms of ASD. Because ASD is a complicated biological puzzle that affects many different parts of children's brains, including the arousal and sleep centers detailed above, it is challenging to understand and treat ASD in its entirety. Importantly, good quality sleep alleviates ASD related psychopathologies. Uncovering the causal link between sleep quality and ASD symptoms using state-of-the-art systems neuroscience techniques combined with neuropharmacological approach in mouse models of ASD will elucidate the neural circuits and molecular mechanisms underlying sleep disturbances. To date, there are no therapeutic sleeping aids approved by the FDA to attenuate sleep disturbances in children with ASD. Leveraging the obtained findings to develop novel therapies to treat sleep disorders in turn may offer relief from ASD core symptoms and improve developmental trajectories. Furthermore, these research efforts will raise awareness of the importance of treating sleep disorders in children with ASD, and will transform behavioral therapies combined with drug treatment to enhance the overall treatment of ASD and thus improve the quality of life in patients and their families.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Franz Weber for proofreading the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01-NS-110865), the Whitehall Foundation, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, a NARSAD Young Investigator grant, Simons Foundation Pilot Award, Eagle Autism Challenge Pilot Grant, The McCabe Fund Award, The Hartwell Individual Biomedical Research Award to S. C. and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Strokes individual F31 fellowship (NS118963-01A1) to J.M. We thank the members from Chung and Weber labs for helpful discussion. Figures were created with Motifolio Illustration Toolkit-Neuroscience.

Handling Editor: Mark R. Opp

References

- Aathira R., Gulati S., Tripathi M., Shukla G., Chakrabarty B., Sapra S., Dang N., Gupta A., Kabra M., Pandey R.M. Prevalence of sleep abnormalities in Indian children with autism spectrum disorder: a cross-sectional study. Pediatr. Neurol. 2017;74:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel E.A., Schwichtenberg A.J., Mannin O.R., Marceau K. Brief report: a gene enrichment approach applied to sleep and autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020;50(5):1834–1840. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-03921-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbas B., Akca O.F. Treatment of a child with autism spectrum disorder and food refusal due to restricted and repetitive behaviors. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(5):364–365. doi: 10.1089/cap.2017.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhondzadeh S., Erfani S., Mohammadi M.R., Tehrani-Doost M., Amini H., Gudarzi S.S., Yasamy M.T. Cyproheptadine in the treatment of autistic disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Pharm. Therapeut. 2004;29(2):145–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2004.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allik H., Larsson J.-O., Smedje H. Sleep patterns of school-age children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006;36(5):585–595. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaclet C., Ferrari L., Arrigoni E., Bass C.E., Saper C.B., Lu J., Fuller P.M. The GABAergic parafacial zone is a medullary slow wave sleep-promoting center. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17(9):1217–1224. doi: 10.1038/nn.3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderlid B.-M., Schoumans J., Annerén G., Tapia-Paez I., Dumanski J., Blennow E., Nordenskjöld M. FISH-mapping of a 100-kb terminal 22q13 deletion. Hum. Genet. 2002;110(5):439–443. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders T., Iosif A.-M., Schwichtenberg A.J., Tang K., Goodlin-Jones B. Sleep and daytime functioning: a short-term longitudinal study of three preschool-age comparison groups. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012;117(4):275–290. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-117.4.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen I.M., Kaczmarska J., McGrew S.G., Malow B.A. Melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Child Neurol. 2008;23(5):482–485. doi: 10.1177/0883073807309783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B.M., Schnetz-Boutaud N.C., Bartlett J., Wotawa A.M., Wright H.H., Abramson R.K., Cuccaro M.L., Gilbert J.R., Pericak-Vance M.A., Haines J.L. Examination of association of genes in the serotonin system to autism. Neurogenetics. 2009;10(3):209–216. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelakos, C., & Abel, T. (Unpublished results). SLEEP AND ACTIVITY PROBLEMS IN MOUSE MODELS OF NEURODEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS. University of Pennsylvania.

- Angelakos C.C., Watson A.J., O'Brien W.T., Krainock K.S., Nickl-Jockschat T., Abel T. Hyperactivity and male-specific sleep deficits in the 16p11.2 deletion mouse model of autism. Autism Res.: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research. 2017;10(4):572–584. doi: 10.1002/aur.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antila H., Kwak I., Choi A., Pisciotti A., Covarrubias I., Baik J., Eisch A., Thomas S., Weber F., Chung S. A noradrenergic-hypothalamic neural substrate for stress-induced sleep disturbances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119(45) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2123528119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]