Abstract

Objective:

To develop self-reported short forms for the Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) Profile.

Design:

Short forms based on the item parameters of discrimination and average difficulty.

Setting:

A support network for burn survivors, peer support networks, social media, and mailings.

Participants:

Burn survivors (N=601) older than 18 years.

Interventions:

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures:

The LIBRE Profile.

Results:

Ten-item short forms were developed to cover the 6 LIBRE Profile scales: Relationships with Family & Friends, Social Interactions, Social Activities, Work & Employment, Romantic Relationships, and Sexual Relationships. Ceiling effects were ≤15% for all scales; floor effects were <1% for all scales. The marginal reliability of the short forms ranged from .85 to .89.

Conclusions:

The LIBRE Profile-Short Forms demonstrated credible psychometric properties. The short form version provides a viable alternative to administering the LIBRE Profile when resources do not allow computer or Internet access. The full item bank, computerized adaptive test, and short forms are all scored along the same metric, and therefore scores are comparable regardless of the mode of administration.

Keywords: Burn injury, Item response theory, Outcome measurement, Psychometrics, Questionnaires, Rehabilitation

Burn survivors face a wide range of burn-related challenges, including physical and psychological issues that potentially impact their ability to reintegrate into society. Physical issues such as joint stiffness, chronic pain, chronic itch, temperature intolerance, scarring, inability to sweat, and fatigue may limit a person’s ability to be active and to join in community events.1,2 Psychological issues may result from the burn survivor’s altered appearance or from an abrupt and unexpected decrease in independence. Anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress are common in almost 50% of burn survivors, with 20% to 30% of adult burn survivors reporting moderate-to-severe psychological and/or social difficulties.3,4 Any of these conditions alone could isolate the burn survivor, but the combination can make recovery especially difficult. Body image, return to work, and sexual function are some of the psychosocial areas that have so far been covered in burn research.2,3,5–8

Individuals with facial disfigurements, such as a face burn, avoid social situations as a way to deal with difficult emotions.5 Dissatisfaction with body image is a common issue for burn survivors and is linked to depression symptoms and social issues.5 Burn survivors report attracting unwanted stares and comments from strangers because of their burn scars. This stigmatization is thought to result in negative body image, anxiety, and depression.2 Although some survivors return to work eventually, ~50% to 60% need a change in employment and 28% of all burn survivors never return to work at all.3,8 Barriers include being self-conscious about appearance, fear of leaving home, and fear of the workplace.6 Burn survivors of both sexes also experience decreased sexual satisfaction, which may relate to the emotional and physical ramifications of the burn injury.3,9

Although some of these issues have previously been identified, burn survivors continue to report that there is a lack of social support and treatment options. Until now, there has not been a measure focused exclusively on the social impact of burn injury. Studies, clinical observations, and burn survivor feedback have all identified the social and psychological difficulties encountered during the rehabilitation process.3,5,10 The ability to measure these difficulties would allow the clinician and patient to have a directed discussion about treatment, optimizing and personalizing a burn survivor’s recovery.10–13

The Burn Specific Health Scale has a limited domain structure that does not examine psychosocial aspects in depth.14 The Burn Outcomes Questionnaire (BOQ) developed by Shriners Burn Hospital and the American Burn Association measures outcomes based on specific age ranges. This measure includes the BOQ0–4, which focuses on children younger than 5 years,15 the BOQ5–18 for children aged 5 to 18 years,16 the BOQ11–18 for adolescents aged 11 to 18 years,17 and the Young Adult Burn Outcome Questionnaire for adults aged 19 to 30 years.18 In addition, generic function and quality of life assessments are limited in their applicability to burn survivors because patients with burns face a complex and unique constellation of impairments that involve multiple domains. These domains deserve acknowledgment and recognition by condition-specific instruments focusing on burn survivors.14

The Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) Profile is a new self-reported measure of social participation for burn survivors. Items were initially developed based on a comprehensive literature review as well as focus groups with clinical experts and burn survivors. We administered the initial group of 192 items to a convenience sample of 601 burn survivors who were 18 years or older, survived a burn that was at least 5% of the total body surface area or burns to 1 of 4 critical areas (face, hands, feet, genitals), were living in the United States or Canada, and were able to read and understand English. Details of the sample are available elsewhere.19–21

Initial analyses included an exploratory factor analysis to examine the factor loading patterns in all 192 items, confirmatory factor analysis to confirm unidimensionality of each domain, and calibration of the items using the 2-parameter graded response item response theory (IRT) model.22–24 We also examined differential item functioning (DIF) to identify whether people at the same estimated ability level in a content domain respond differently to the same item based on another variable. DIF testing was conducted on the basis of age, sex, race, and time since burn injury using a 2-step IRT-based DIF method and examined the difference in item characteristic curves using the weighted area between the expected score curves to examine DIF impact. Items that demonstrated DIF were retained with calibrations specific to the relevant characteristic.25–27

The 6 scales of the LIBRE Profile are Relationships with Family & Friends, Social Interactions, Social Activities, Work & Employment, Romantic Relationships, and Sexual Relationships. The scales contain questions and statements with 3 response categories. The first were agreement responses: Strongly Agree, Agree, Neither Agree nor Disagree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree, Not Applicable. The second was a frequency scale: Never, Almost Never, Sometimes, Often, Always, N/A. And the third type of category was related to degree: Not at All, A Little Bit, Somewhat, Quite a Bit, Very Much, Not Applicable. Person IRT scores are transformed to a T-score distribution where the mean was 50 and SD 10 based on the average of the overall sample of burn survivors used for the calibration phase of the study (T score=person score×10+50). Lower scores correspond to poorer performance on the scale.

The LIBRE Profile was originally developed for administration through computerized adaptive testing (CAT). CAT draws on items from the entire instrument, applying an algorithm to choose which items to pose to the participant on the basis of previous responses. The advantage of this administration is that it achieves accurate and precise scores while administering fewer questionnaire items than does a traditional full-length measure.13,28 However, not every clinical setting is able to use CAT because of limited computer resources or expertise.12,29 For this reason, we set out to develop fixed short forms—a subset of questions from the larger instrument—which can be administered and scored on paper.

This article discusses the development and assessment of the psychometric properties of the IRT-based LIBRE Profile-Short Forms (SFs). The LIBRE Profile-SF will allow more people to have access to the tool who do not have the ability to administer the CAT tool. This study was approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board.

Methods

Sample

The LIBRE Profile-SFs were developed using the data from the same sample of 601 burn survivors who provided the information for the development of the initial LIBRE Profile.

Strategy for SF construction

For the candidate items in each LIBRE Profile item bank, we used IRT methods to select questions for SF inclusion based on high item discrimination, large score range coverage, matching between the item score range and the sample distribution, and a distribution of average item difficulty across the continuum of a scale. Item characteristic curves reflect the relation between each item and the latent trait that is being assessed. The item discrimination parameter reflects the steepness (slope) of the item characteristic curve. The higher the discrimination parameter for an item, the more that item is able to distinguish among subjects at a similar latent trait level.30,31 Items that displayed DIF were not candidates for the LIBRE Profile-SF.

We calculated the target test information (TIF) value for the whole SF that would be needed to achieve the acceptable reliability of ≥.80. TIF was weighted by the outpatient sample distribution (using the formula I=∫info(Θ)g(Θ)d Θ, I) to select items with information matched to the score range of the sample. The information value (I) was calculated for each item, and then for all possible 2-item combinations, using the item with the highest I, and each of the other items. The 2 items with the highest I were then selected, and the process was repeated for 3 items. This process was repeated until all possible items were exhausted.

Statistical analysis

After we arrived at the final items for each SF, we examined their content compared with that of all the items of each of the 6 scales. We calculated the internal consistency reliability of all SFs to determine the number of items in the final accepted SF.

Using the item parameters obtained from the full item bank analysis, we scored the SF for each respondent and calculated the proportion of the sample at the ceiling and floor of the 2 administration methods for each scale. Last, we compared the marginal reliability (calculated by score variance-average or squared SE/score variance) and information provided (called the TIF) for each SF and the full item bank across the entire score distribution for each content domain. To facilitate scoring the SFs, we generated conversion tables of the summed raw scores and the scale T scores. For each raw score, we collected all likelihoods of the response patterns yielding the same raw score and formed the joint likelihood and then used the expected a posteriori method to calculate the scale score based on the joint likelihood.32

Finally, to provide an example of 1 way LIBRE Profile scores can be displayed in the future, we generated a sample item map illustrating where a person’s score lies relative to the item content across the Relationships with Family & Friends short form scale.

Results

The sample includes 601 burn survivors (table 1); 329 (54.74%) were women; the mean age at survey administration was 44.55±15.98 years; the mean total body surface area burned was 40.45%; and the mean time since burn injury was 15.36 years.

Table 1.

SampLe demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (y) | 44.55±15.98 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 329 (54.74) |

| Male | 271 (45.09) |

| Missing | 1 (0.17) |

| Race | |

| White | 481 (80.03) |

| Black/African American | 57 (9.48) |

| Other | 54 (8.99) |

| Missing | 9 (1.50) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |

| Yes | 41 (6.82) |

| No | 552 (91.85) |

| Missing | 8 (1.33) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 4 (0.67) |

| High school/GED | 244 (40.60) |

| Greater than high school | 349 (58.07) |

| Missing | 4 (0.67) |

| Time since burn injury | 15.36±16.18 |

| Total body surface area burned | 40.45±23.65 |

NOTE. Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

Abbreviation: GED, General Equivalency Diploma.

There are 6 LIBRE Profile-SFs with 10 items each. Table 2 presents the item content of all SFs, the item difficulty, and slope for each item. The average item difficulty was the most narrow for the Romantic Relationships scale (36.7—41.62) and widest for the Social Interactions scale (29.91—42.88). Score ranges (table 3) indicate coverage of almost 3 SDs below the mean on all scales and between 1 and 2 SDs above the mean on all scales.

Table 2.

LIBRE Profile-SFs

| Item | Slope | Item Difficulty | Item Fit (χ2, df, P) | Item Total Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Relationships with Family & Friends | ||||

| Members of my family give me the support that I need. | 2.56 | −0.99 | 24.86, 40, 0.97 | .75 |

| As much as possible, I avoid members of my family. | 2.66 | −1.28 | 23.35, 37, 0.96 | .76 |

| I don’t like the way most family members act around me. | 2.46 | −1.22 | 26.59, 40, 0.95 | .68 |

| Most family members are comfortable being with me. | 2.66 | −1.40 | 21.12, 38, 0.99 | .68 |

| Members of my family enjoy meeting my friends. | 2.13 | −1.03 | 30.33, 39, 0.84 | .66 |

| I don’t get along with my family. | 2.11 | −1.27 | 28.65, 38, 0.86 | .64 |

| I would rather be alone than with my family. | 1.72 | −0.95 | 40.1, 43, 0.6 | .64 |

| I am comfortable being helped by my family. | 1.7 | −1.03 | 37.95, 41, 0.61 | .61 |

| My family is comfortable talking about burns | 1.73 | −0.88 | 44.87, 44, 0.43 | .61 |

| I have many friends in the city where I live. | 1.51 | −0.65 | 48.45, 41, 0.2 | .49 |

| Social Interactions | ||||

| Because of my burns, I feel uncomfortable in social situations. | 4.53 | −0.99 | 15.23, 45, 1 | .84 |

| Because of how my burns look, I am uncomfortable when I meet new people. | 3.84 | −0.87 | 29.77, 45, 0.96 | .81 |

| Because of my burns, I am uncomfortable around strangers. | 3.45 | −0.80 | 50.46, 46, 0.3 | .81 |

| I avoid doing things that might call attention to my burns. | 2.96 | −0.71 | 39.1, 47, 0.79 | .79 |

| I feel like I don’t fit in with other people. | 2.39 | −0.95 | 44.16, 46, 0.55 | .7 |

| I am upset when strangers comment on my burns. | 1.64 | −0.86 | 32.39, 48, 0.96 | .62 |

| I feel embarrassed about my burns. | 3.04 | −0.86 | 36.26, 47, 0.87 | .82 |

| I limit my activities because of how my burns look. | 2.43 | −1.20 | 24.06, 47, 1 | .71 |

| I don’t worry about other people’s attitudes towards me. | 1.24 | −1.05 | 64.95, 50, 0.08 | .5 |

| I can help strangers feel comfortable around me. | 1.36 | −2.01 | 36.59, 46, 0.84 | .52 |

| Social Activities | ||||

| I am upset that my burns limit what I can do with friends. | 2.86 | −0.76 | 37, 36, 0.42 | .75 |

| I am disappointed in my ability to do leisure activities. | 2.54 | −0.75 | 26.63, 37, 0.9 | .76 |

| I am able to do all of my regular family activities. | 2.65 | −1.12 | 29.12, 33, 0.66 | .7 |

| I tire easily when I go out with friends. | 2.38 | −0.77 | 33.03, 37, 0.66 | .72 |

| I am limited in what I can do for my family. | 2.32 | −0.46 | 37.15, 40, 0.6 | .7 |

| My burns limit me being active. | 2.26 | −0.66 | 33.49, 40, 0.76 | .72 |

| I am satisfied with my ability to do things for my friends. | 2 | −0.79 | 44, 41, 0.35 | .69 |

| How much do you enjoy your social life? | 1.47 | −1.04 | 61.42, 41, 0.02 | .61 |

| I avoid outdoor activities because of my burns. | 1.33 | −0.38 | 42.35, 44, 0.54 | .56 |

| I am able to socialize with my friends. | 1.68 | −1.10 | 45.76, 35, 0.11 | .59 |

| Work & Employment | ||||

| Because of my burns I am unable to finish many work tasks. | 4.54 | −1.21 | 10.6, 20, 0.96 | .76 |

| I can keep up with my work responsibilities. | 3.98 | −1.08 | 11.39, 22, 0.97 | .79 |

| Compared to others, I am limited in the amount of work I can do. | 3.05 | −0.97 | 30.51, 24, 0.17 | .76 |

| I have enough energy to complete my work. | 2.95 | −0.70 | 11.82, 23, 0.97 | .75 |

| I get tired too quickly at my job. | 2.64 | −1.00 | 40.43, 23, 0.01 | .77 |

| I am satisfied with how much I can do at my job. | 3.32 | −0.95 | 15.22, 22, 0.85 | .78 |

| I get unwanted attention from my coworkers. | 1.72 | −0.59 | 32.56, 24, 0.11 | .54 |

| I am satisfied with my work. | 1.71 | −0.96 | 20.58, 22, 0.55 | .61 |

| At my job, I can do everything for work that I want to do. | 2.29 | −1.27 | 16.85, 24, 0.85 | .7 |

| My emotions make it difficult for me to go to work. | 1.94 | −0.85 | 32.12, 24, 0.12 | .6 |

| Romantic Relationships | ||||

| Things between my partner and me are going well. | 3.73 | −0.89 | 7.3, 17, 0.98 | .79 |

| My partner is very loving to me. | 3.43 | −0.98 | 8.33, 19, 0.98 | .79 |

| My partner makes me happy. | 3.58 | −1.11 | 6.25, 16, 0.99 | .78 |

| I have a partner who meets many of my emotional needs. | 3.17 | −0.84 | 4.86, 17, 1 | .78 |

| I am comfortable talking openly with my partner. | 3.41 | −0.92 | 7.05, 18, 0.99 | .78 |

| My partner makes me feel needed. | 2.52 | −0.96 | 10.79, 18, 0.9 | .73 |

| I trust my partner with my deepest thoughts and feelings. | 2.34 | −0.88 | 14.27, 17, 0.65 | .71 |

| My partner is fun to be with. | 2.95 | −0.60 | 11.25, 16, 0.79 | .74 |

| My partner gets on my nerves all of the time. | 1.88 | −1.33 | 11.22, 20, 0.94 | .62 |

| I am afraid to share with my partner what I dislike about myself. | 1.4 | −0.86 | 22.34, 18, 0.22 | .49 |

| Sexual Relationships | ||||

| I avoid sexual contact because of my burns. | 2.86 | −1.14 | 18.69, 25, 0.81 | .69 |

| I am able to do the kinds of sexual activities that I like. | 2.06 | −1.05 | 43.32, 31, 0.07 | .69 |

| I am not interested in sex anymore. | 3.05 | −1.02 | 15.37, 27, 0.96 | .74 |

| I am satisfied with the amount of emotional closeness during sexual activity. | 2.08 | −0.95 | 16.87, 29, 0.96 | .71 |

| I think nobody finds me sexually attractive. | 1.89 | −0.93 | 25.13, 32, 0.8 | .7 |

| Sex is fun for me. | 3.24 | −0.89 | 15.82, 27, 0.96 | .78 |

| I have trouble becoming sexually excited. | 2.63 | −0.67 | 32.17, 27, 0.23 | .74 |

| I think that my partner enjoys our sex life. | 2.53 | −0.61 | 17.76, 25, 0.85 | .79 |

| I feel that our sex life really adds a lot to our relationship. | 1.94 | −0.52 | 20.86, 29, 0.86 | .71 |

| I am satisfied with my frequency of sexual activity. | 1.63 | −0.49 | 41.01, 33, 0.16 | .7 |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for full item bank and short forms

| Domain | Mode | n | Short Form Score Range | Marginal Reliability | %Ceiling Effects | %Floor Effects | %Item Bank Information Covered by Short Form |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Relationships with Family & Friends | Full item bank | 598 | 17.87–68.00 | .91 | 1.67 | 0 | 54.99 |

| Short form | 598 | .85 | 6.33 | 0.17 | |||

| Social Interactions | Full item bank | 600 | 18.76–66.52 | .93 | 3 | 0 | 42.94 |

| Short form | 600 | .89 | 5.16 | 0.33 | |||

| Social Activities | Full item bank | 594 | 20.13–68.60 | .87 | 6.73 | 0 | 75.46 |

| Short form | 594 | .86 | 7.49 | 0.17 | |||

| Work & Employment | Full item bank | 318 | 22.33–64.69 | .88 | 11.64 | 0 | 63.07 |

| Short form | 318 | .85 | 13.75 | 0.31 | |||

| Romantic Relationships | Full item bank | 378 | 21.65–65.39 | .92 | 2.12 | 0 | 51.60 |

| Short form | 378 | .87 | 10.82 | 0.26 | |||

| Sexual Relationships | Full item bank | 378 | 20.85–68.45 | .89 | 3.44 | 0 | 76.90 |

| Short form | 378 | .86 | 7.57 | 0 | |||

Table 3 presents the comparisons of several key psychometric properties of the 2 measures: the full item bank and SF subset of items. The marginal reliability of the full item bank ranged from .87 to .93. For the SFs, marginal reliability ranged from .85 to .89. Ceiling effects were ≤15% for all scales; floor effects were all <1%.

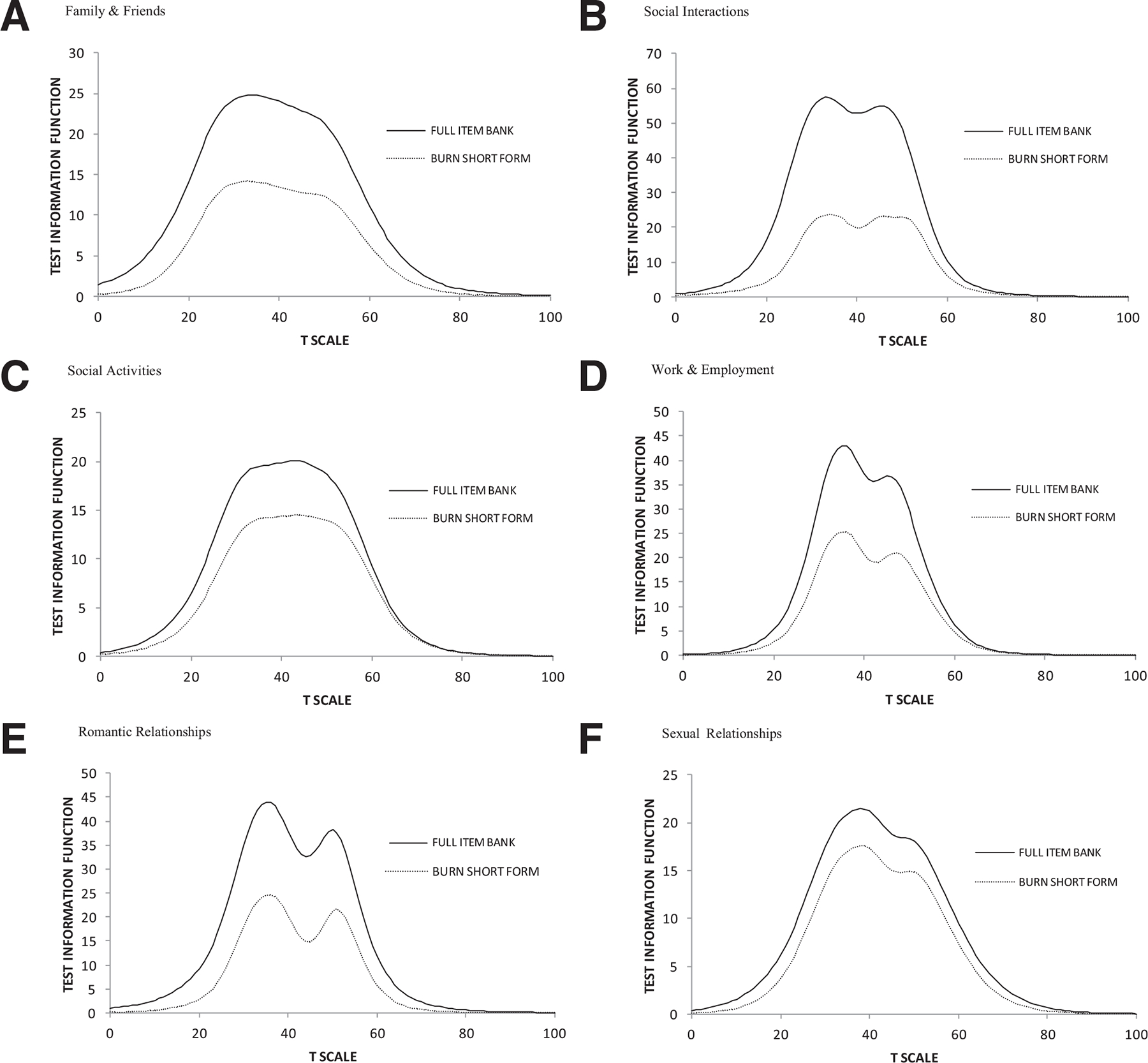

Figure 1 illustrates the TIF of the full item bank compared to the SFs. There is some sacrifice in score precision for each SF compared to the full item bank, but the SFs generate reliability >0.9 for a wide range of scale scores. The peaks of the TIF curves occur at the same score ranges, which is also where most of the scores are located. At a maximum, the Sexual Relationships SF TIF curve covers 76.9% of the full item bank; the least amount of coverage is the Social Interactions SF, which covers only 42.9% of the full item bank TIF curve.

Fig 1.

TIF of the full item bank compared to the SFs.

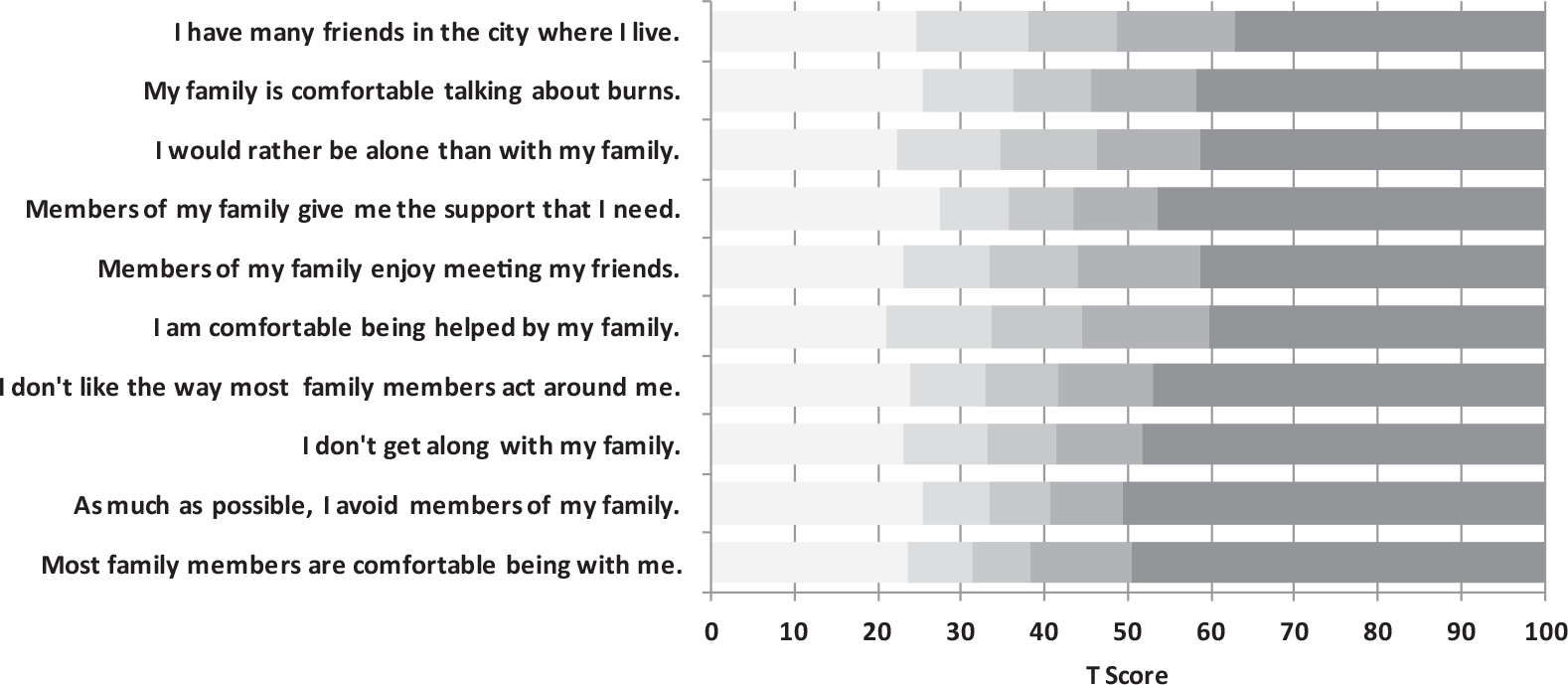

Figure 2 displays 1 possible way scores can currently be interpreted by using the Relationships with Family & Friends scale as an example. The items are ordered from hardest at the top (most difficult) to easiest (least difficulty) along the vertical axis. The responses are ordered along the horizontal axis indicating the T score of that scale. Each shadow bar represents the expected category score range. For example, for the first item (“I have many friends in the city where I live.”), the 5 shadow bars from left to right represent 5 response categories. For the “Strongly disagree” category, the corresponding T score ranges from 0 to 24.7; for “Disagree,” the corresponding T score ranges from 24.7 to 38; for “Neither Agree nor Disagree,” the corresponding T score ranges from 38 to 48.6; for “Agree,” the corresponding T score ranges from 48.6 to 62.7; and for “Strongly Agree,” the corresponding T score ranges from 62.7 to 100. A figure such as this facilitates score interpretation by presenting a person’s score relative to all the item content.

Fig 2.

Sample item map for score interpretation of the Relationships with Family & Friends scale.

Discussion

The LIBRE Profile-SF is made up of six 10-item short forms, 1 for each of the LIBRE Profile scales. The results suggest that the LIBRE Profile-SF can be an accurate and reliable way to measure social participation in burn survivors.

There is some loss of precision with the SF compared with the full item bank. This is expected, because the SFs contain fewer items. However, all the SFs have ceiling effects of <15%, and the marginal reliability ranged from .85 to .89, which is considered credible.30 These findings show that the LIBRE Profile-SF demonstrates appropriate psychometric properties. The differences in scores occur at the extremes, with lower reliability for people who have either very low or very high scores. Therefore, although the LIBRE Profile-SF has fewer items compared to the full item bank, it can also provide an accurate level score as a substitute for the full item bank.

It is important to keep measures brief so that they can be used in a fast-paced clinical setting. We developed 10-item short forms as an appropriate balance between precision and feasibility. Participants would likely prefer a precise score without spending a lengthy amount of time responding to items. More items in an SF increase the precision of the score, but would also increase the respondent burden. A 10-item SF provides an accurate score and is still feasible to administer. Other SFs could be developed using different items or a different number of items (more or fewer).

The Relationships with Family & Friends SF contains 8 items about family and 2 items about friends as compared with the full item bank that contains 14 family items and 10 friend items, suggesting that scores in that domain are driven by items related to family. Four of the Social Interactions items focus on strangers or meeting new people, reflecting the presence of that aspect of the domain in the full scale. All 3 items in the full item bank of the Social Activities scale that mention burns are included in the SF, which is beneficial to keeping the items relevant to the burn survivor experience. The Work & Employment SF focuses primarily on global satisfaction with work performance (8 of the 10 items), whereas the full item bank has more of a balance between those items (11) and others involving social dynamics in the workplace (8). The full item bank of the Romantic Relationships scale is the largest in the LIBRE Profile (28 items), whereas the Sexual Relationships is one of the smallest (15 items); the item content of both SFs is generally representative of the full scales.

The short forms are meant to be an alternative to CAT for situations where it cannot be administered owing to lack of access to a computer or the Internet. The SFs are scored on the same metric as does CAT. This means the scores of the SFs are comparable with those of CAT on the similar metric. This is important so that results from the 2 instruments can be analyzed within the same context as all other LIBRE Profile scores. Scores will inform patients as to how they are faring within a context of social participation after a burn injury. Currently, scores can be compared with those of other burn survivors from the survey of 601 subjects as part of the original LIBRE Profile calibration study.

Study limitations

Limitations to this study include the sampling method. A convenience sample of 601 burn survivors participated in the calibration phase of the study. Although they represent a wide range of various demographic and clinical characteristics, participants may represent a population that is more likely to be engaged in social support programs. This connection to resources may help to explain some of the ceiling effects observed in the data set. There are also limitations inherent to the graded response IRT model chosen for the LIBRE Profile that are worth noting. In the 2-parameter graded response IRT model, the IRT scores from 2 samples are not directly comparable; to make scores comparable across samples, we had to link the scores onto a common metric.33 However, we feel that this limitation is worth the trade-off because the 2-parameter approach provided us with the better model fit.34 This approach has also been used throughout the literature, including the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System initiative.35,36

Finally, because the LIBRE Profile is still in its early stages of development, there is currently no clinically meaningful guide to facilitate score interpretation beyond the item map example presented here. Although future work will hopefully further this aim, the main guidance for score interpretation is based on the scale and score distribution (with a mean of 50 and an SD of 10).

Conclusions

As a patient-reported outcome measure, the LIBRE Profile-SF can be used to better engage the patient and inform treatment, contributing to a more complete rehabilitation process. The short form version of the LIBRE Profile ensures accessibility when resources are scarce, either on an individual or on a health care facility level. The LIBRE Profile-SF will allow more people to have access to the LIBRE Profile who do not have the ability to administer the CAT tool. To obtain the LIBRE Profile-SF, complete with scoring instructions and conversion tables, e-mail at libre@bu.edu.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (award no. 90DP0055).

List of abbreviations:

- BOQ

Burn Outcomes Questionnaire

- CAT

computerized adaptive testing

- DIF

differential item functioning

- IRT

item response theory

- LIBRE

Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation

- SF

Short Form

- TIF

test information function

Footnotes

Disclosures: none.

References

- 1.Schneider JC, Qu HD. Neurologic and musculoskeletal complications of burn injuries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2011;22:261–75, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence JW, Mason ST, Schomer K, Klein MB. Epidemiology and impact of scarring after burn injury: a systematic review of the literature. J Burn Care Res 2012;33:136–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blakeney PE, Rosenberg L, Rosenberg M, Faber AW. Psychosocial care of persons with severe burns. Burns 2008;34:433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madianos MG, Papaghelis M, Ioannovich J, Dafni R. Psychiatric disorders in burn patients: a follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom 2001;70:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thombs BD, Notes LD, Lawrence JW, Magyar-Russell G, Bresnick MG, Fauerbach JA. From survival to socialization: a longitudinal study of body image in survivors of severe burn injury. J Psychosom Res 2008;64:205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esselman PC. Community integration outcome after burn injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2011;22:351–6, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackey SP, Diba R, McKeown D, et al. Return to work after burns: a qualitative research study. Burns 2009;35:338–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mason ST, Esselman P, Fraser R, Schomer K, Truitt A, Johnson K. Return to work after burn injury: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res 2012;33:101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bianchi TL. Aspects of sexuality after burn injury: outcomes in men. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997;18:183–6, discussion 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kvannli L, Finlay V, Edgar DW, Wu A, Wood FM. Using the Burn Specific Health Scale-Brief as a measure of quality of life after a burn—what score should clinicians expect? Burns 2011;37:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan CM, Lee AF, Kazis LE, et al. Is real-time feedback of burn-specific patient-reported outcome measures in clinical settings practical and useful? A pilot study implementing the Young Adult Burn Outcome Questionnaire. J Burn Care Res 2016;37:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonough CM, Ni P, Coster WJ, Haley SM, Jette AM. Development of an IRT-based short form to assess applied cognitive function in outpatient rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2016;95:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella D, Gershon R, Lai JS, Choi S. The future of outcomes measurement: item banking, tailored short-forms, and computerized adaptive assessment. Qual Life Res 2007;16(Suppl 1):133–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willebrand M, Kildal M. A simplified domain structure of the Burn-Specific Health Scale-Brief (BSHS-B): a tool to improve its value in routine clinical work. J Trauma 2008;64:1581–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazis LE, Liang MH, Lee A, et al. The development, validation, and testing of a health outcomes burn questionnaire for infants and children 5 years of age and younger: American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children. J Burn Care Rehabil 2002;23:196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daltroy LH, Liang MH, Phillips CB, et al. American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children burn outcomes questionnaire: construction and psychometric properties. J Burn Care Rehabil 2000;21(1 Pt 1):29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer WJ, Lee AF, Kazis LE, et al. Adolescent survivors of burn injuries and their parents’ perceptions of recovery outcomes: do they agree or disagree? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73(3 Suppl 2):S213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan CM, Schneider JC, Kazis LE, et al. Benchmarks for multidimensional recovery after burn injury in young adults: the development, validation, and testing of the American Burn Association/Shriners Hospitals for Children Young Adult Burn Outcome Questionnaire. J Burn Care Res 2013;34:e121–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazis LE, Marino M, Ni P, et al. Development of the Life Impact Burn Recovery Evaluation (LIBRE) profile: assessing burn survivors’ social participation. Qual Life Res 2017;26:2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marino M, Soley-Bori M, Jette AM, et al. Measuring the social impact of burns on survivors. J Burn Care Res 2017;38:e377–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marino M, Soley-Bori M, Jette AM, et al. Development of a conceptual framework to measure the social impact of burns. J Burn Care Res 2016;37:e569–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibbons RD, Bock RD, Hedeker D, et al. Full-information item bifactor analysis of graded response data. Appl Psychol Meas 2007;31:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edelen MO, Reeve BB. Applying item response theory (IRT) modeling to questionnaire development, evaluation, and refinement. Qual Life Res 2007;16(Suppl 1):5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orlando M, Thissen D. Further investigation of the performance of S - X2: an item fit index for use with dichotomous item response theory models. Appl Psychol Meas 2003;27:289–98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langer M. A reexamination of Lord’s Wald test for differential item functioning using item response theory and modern error estimation [dissertation]. Chapel Hill: Univ of North Carolina; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woods CM, Cai L, Wang M. The Langer-improved Wald test for DIF testing with multiple groups evaluation and comparison to two-group IRT. Educ Psychol Meas 2013;73:532–47. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edelen MO, Stucky BD, Chandra A. Quantifying “problematic” DIF within an IRT framework: application to a cancer stigma index. Qual Life Res 2015;24:95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi SW, Reise SP, Pilkonis PA, Hays RD, Cella D. Efficiency of static and computer adaptive short forms compared to full-length measures of depressive symptoms. Qual Life Res 2010;19:125–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinemann AW, Dijkers MP, Ni P, Tulsky DS, Jette A. Measurement properties of the Spinal Cord Injury-Functional Index (SCI-FI) short forms. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:1289–1297.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hays RD, Morales LS, Reise SP. Item response theory and health outcomes measurement in the 21st century. Med Care 2000;38(9 Suppl):II28–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Revicki DA, Cella DF. Health status assessment for the twenty-first century: item response theory, item banking and computer adaptive testing. Qual Life Res 1997;6:595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thissen D, Nelson L, Rosa K, McLeod L. Item response theory for items scored in more than two categories. In: Thissen D, Wainer H, editors. Test scoring. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. p 141–86. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolen MJ, Brennan RL. Test equating, scaling, and linking—methods and practices. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thissen D, Wainer H, editors. Test scoring. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varni JW, Stucky BD, Thissen D, et al. PROMIS Pediatric Pain Interference Scale: an item response theory analysis of the pediatric pain item bank. J Pain 2010;11:1109–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1179–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]