Abstract

Mice immunized with peritoneal exudate cells (PEC; used as antigen-presenting cells [APC]) that are pulsed ex vivo with cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide, a glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), exhibit increased survival times and delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions when they are infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. These responses are GXM specific. The present study revealed that GXM-APC immunization enhanced development of anticryptococcal type-1 cytokine responses (interleukin-2 [IL-2] and gamma interferon) in mice infected with C. neoformans. The enhancement was not GXM specific, because immunization with GXM-APC and immunization with APC alone had similar effects. GXM-APC (or APC) immunization caused small increases in the expression of type-2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-5), but the increases were not always statistically significant. IL-10 levels were not regulated by immunization with GXM-APC or APC. GXM-APC prepared with PEC harvested from mice injected with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) enhanced type-1 cytokine responses, while GXM-APC prepared with PEC induced with incomplete Freund's adjuvant were ineffective. The CFA-induced PEC had an activated phenotype characterized by increased numbers of F4/80+ cells that expressed CD40, B7-1, and B7-2 on their membranes. The immunomodulatory activity of the CFA-induced APC population was not attributed to their production of IL-12 because GXM-APC prepared with peritoneal cells harvested from IL-12 knockout mice or their wild-type counterparts were equally effective in augmenting the type-1 response. Blocking of IL-12 in the recipients of GXM-APC early after APC infusion revealed that early induction of IL-12 secretion was not responsible for the immunomodulatory response elicited by GXM-APC. These data, considered together with previously reported data, reveal that the protective activity of GXM-APC immunization involves both antigen-specific and nonspecific activities of GXM-APC.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a ubiquitous yeast-like organism that is found in the soil worldwide (12). It is believed that the portal of entry of the organism is the lung, where it is usually eliminated in immunologically normal hosts (24). In immunocompromised hosts and in a few apparently normal hosts, the organism is not cleared and eventually spreads to other organs (12, 24). C. neoformans has a predilection for the brain, where it causes a meningoencephalitis that is fatal if not treated. There is a great amount of variation in the virulence of individual cryptococcal isolates (4, 13), and these variations may be one of several reasons that explain why some immunologically normal individuals develop cryptococcosis.

We studied a highly virulent isolate of C. neoformans and found that normal mice infected with this isolate develop a generalized form of immunosuppression as a result of their infection (6, 27). Immune responses to this isolate are characterized by a short period of immune responsiveness followed by profound unresponsiveness (4). One aspect of the immunosuppressive response can also be induced in normal mice by injection of purified cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide, a glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) (6–8, 22, 27). Recently, we reported that it is possible to specifically inhibit the induction of the GXM-induced immunosuppressive response when mice are immunized with antigen-presenting cells (APC) that have first been incubated ex vivo with soluble GXM (GXM-APC) (5). In addition, mice immunized with GXM-APC survive longer and maintain delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses for a longer period after they are infected with C. neoformans. Sham-immunized (levan-APC) mice are not protected and lose DTH reactions in a manner similar to that of mice infected without prior APC treatment (5). The present investigation was undertaken to determine if GXM-APC immunization enhances survival and DTH reactions by influencing the expression of type-1 (interleukin-1 [IL-1] and gamma interferon [IFN-γ]), type-2 (IL-4 and IL-5), or immunosuppressive (IL-10) cytokines in infected mice. The role that IL-12 plays in the induction of the cytokine and DTH responses was examined, as well as the influence of the state of activation of the peritoneal exudate cell (PEC) population used to prepare GXM-APC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL/6J, CBA/J, and C57BL/6-IL12tm1Jm (IL-12 p40 knockout) female mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine. CBA/J mice were used in experiments when they were 8 to 10 weeks old, and all other mice were used in experiments when they were 12 to 14 weeks old. The mice were housed in the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Animal Facility, which is accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Reagents.

Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), HEPES, penicillin-streptomycin, l-glutamine, 2-mercaptoethanol, sodium pyruvate, essential vitamins, and nonessential amino acids were purchased from GIBCO BRL (Grand Island, N.Y.). HyClone (Ogden, Utah) was the supplier of fetal bovine serum (FBS). Concanavalin A (ConA), RPMI 1640, and complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.) was the supplier of recombinant mouse IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-5 and of the paired monoclonal antibodies specific for these cytokines that were used in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). Neutralizing anti-IL-12 used for in vivo treatment was also purchased from PharMingen. IL-10 was measured with PharMingen OptEIA kits. Purified rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) was purchased from ICN Biomedicals Inc. (Aurora, Ohio). Flow cytometry reagents purchased from PharMingen included fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-mouse B220 and FITC-labeled rat IgG2a isotype control. Caltag (Burlingame, Calif.) was the supplier of tricolor-labeled anti-mouse F4/80, phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-mouse CD40, PE-labeled anti-mouse B7-1, PE-labeled anti-mouse B7-2, tricolor-labeled rat IgG2b isotype control, and PE-labeled mouse IgG2a isotype control.

Fungal strains.

The isolate of C. neoformans used for infection of mice in these experiments was NU-2, originally obtained from the spinal fluid of a patient at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Isolate 184A was used for preparation of cryptococcal skin test antigen (CneF) and was obtained from Juneann Murphy, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

Maintenance of endotoxin-free conditions.

To ensure that endotoxin contamination was not a factor in our experiments, all procedures were performed under conditions that minimized endotoxin contamination. Endotoxin-free plasticware was used whenever possible, and glassware was heated for 3 h at 180°C. All reagents contained less than 1 endotoxin unit (EU) of endotoxin/ml (minimal detectable level) in the chromogenic Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (Whittaker Bioproducts, Inc., Walkersville, Md.).

Preparation of cryptococcal antigens.

Cryptococcal culture filtrate antigen (CneF) was prepared from C. neoformans isolate 184A by the method of Buchanan and Murphy (11). The preparation used in this investigation had a protein content of 252.3 μg/ml as determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.) and a carbohydrate concentration of 5 mg/ml as determined by the phenol-sulfuric acid assay (14). When tested in the Limulus assay, this lot of CneF gave a reaction equivalent to 12.9 EU of endotoxin/ml, and when added to spleen cell cultures, it contributed 0.64 EU per ml of culture. Because the extract contains a high concentration of GXM, which gives a positive reaction in the Limulus assay due to its glucuronic acid content (26), this Limulus reactivity is considered to be due to the glucuronic acid rather than to endotoxin contamination.

Cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide (GXM) was prepared as described previously (8). This lot of polysaccharide gave a reaction equivalent to 11.4 EU of endotoxin/ml of a GXM solution containing 10 μg of polysaccharide/ml. Much of this reactivity can be attributed to the high glucuronic acid content of GXM. However, if one were to consider all of the reactivity to be due to endotoxin, we would be adding approximately 1 ng of endotoxin to our APC suspensions. To test for the ability of GXM to influence the state of activation of the APC, GXM was tested for its ability to modulate cytokine mRNA levels of PECs induced with CFA (method described below). RNA extracts obtained from PECs incubated in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS in the presence or absence of 10 μg of GXM per ml for 5 h were assayed for cytokine mRNA levels by a commercially available RNase protection kit (PharMingen). The results of this analysis showed that the polysaccharide did not augment or inhibit PEC mRNA expression of IL-12 p35, IL-12 p40, IL-10, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-6, IFN-γ, or migration inhibition factor (MIF) compared to expression by PECs that were incubated for 5 h in medium without GXM stimulation.

Preparation of GXM-APC.

Normal donor mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.5 ml of CFA or incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA). Five days later, PECs were harvested with Dulbecco's PBS containing 1% FBS. The cells were washed twice and resuspended at 5 × 106 cells/ml of RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 100 U of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. GXM was added to a portion of the cells at a final concentration of 10 μg per ml. Control APC were incubated in medium without the addition of antigen. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the cells were washed three times in PBS and resuspended at 107 viable cells/ml. After an additional three washes with PBS, the cells were used to immunize recipient animals. For all immunizations, recipient animals were given 5 × 106 GXM-APC or control APC intravenously.

Experimental protocol.

Animals were injected with GXM-APC or with APC alone 7 days prior to infection with 104 (cytokine analysis) or 105 (DTH analysis) C. neoformans (NU-2) organisms as indicated. Some experiments included APC donors that had a deletion of the IL-12 p40 gene (IL-12 knockout). Controls included naïve animals that were infected without previous treatment with APC and sham-infected, normal mice that were not immunized and were given 25 μl of PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Initial kinetic analysis of C57BL/6 mice showed that peak cytokine responses occurred on the 10th to 15th day after infection with 104 NU-2 cells. Due to fluctuations in the kinetics of the infectious process, analysis of cytokine responses was routinely performed on the 10th and 15th days after infection so that the peak response would not be missed. The data presented represent the peak cytokine responses obtained for individual experiments. Some experiments included treatment of recipient mice with 100 μg of neutralizing anti-IL-12 or 100 μg of rat immunoglobulin 1 h before injection of GXM-APC or untreated APC. The dose of monoclonal anti-IL-12 was proven to neutralize 4-h serum IL-12 levels in mice injected with 10 μg of endotoxin as described by Wysocka et al. (31). In some experiments, the ability of CneF to elicit an anticryptococcal DTH response was tested in mice 16 days (C57BL/6 mice) or 21 days (CBA/J mice) after intratracheal infection with 105 NU-2 cells. During infection with the NU-2 cryptococcal isolate, mice develop a transient DTH response that is followed by DTH unresponsiveness (4). GXM-APC administration prolongs the responsive state. Previous investigations with C57BL/6 mice (5) and CBA/J mice (4) established the time points of the unresponsive phase for each of the two mouse strains when the mice were infected intratracheally with 105 NU-2 cells. In C57BL/6J mice the unresponsive phase usually occurs by the 15th day of infection, while CBA/J mice become unresponsive by the 20th day of infection. The time of assay of the DTH response was chosen to ensure that infected control mice had entered the unresponsive phase.

In vitro stimulation of cytokine synthesis by spleen cells.

Spleen cells were harvested from individual mice, and single-cell suspensions were prepared by pressing the spleens through a sterile 60-mesh wire screen into sterile PBS containing 1% FBS. The cells were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in Bretcher's medium (RPMI 1640 containing 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 25 mM HEPES, 5 × 10−3 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% essential vitamins, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 10% FBS). Spleen cells at a concentration of 5 × 106/ml were stimulated with cryptococcal CneF (at a final dilution of 1:20) or cultured without stimulation to determine the constitutive or background level of cytokine secretion. Positive controls consisted of cells stimulated with 10 μg of ConA/ml. Cultures were incubated at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and supernatant fluids were collected 24 and 48 h after the initiation of culture.

Quantitation of cytokine levels in culture supernatants.

ELISA for detection of IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-5 in tissue culture supernatants were constructed using commercially available paired monoclonal antibodies for each cytokine (PharMingen) according to our previously described method (4). IL-10 levels were determined according to the manufacturer's protocol by using PharMingen's OptEIA IL-10 kit. IL-2 levels were measured in 24-h supernatant fluids, and all other cytokines were measured in 48-h supernatant fluids. The minimal levels of detection of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IFN-γ assays were 31.9, 6.25, 25, 31.3, and 125 pg/ml, respectively.

Elicitation of the anticryptococcal DTH response.

Hind footpads of mice were measured with a gauge micrometer (Starrett, Athol, Mass.). PBS (30 μl) was injected into the left footpad, and CneF (30 μl) was injected into the right footpad. The footpads were measured again 24 h later. The increase in footpad thickness was calculated as the difference in swelling between 0- and 24-h measurements. Specific DTH reactivity was calculated as the difference between the swelling of the CneF-injected footpads and the swelling of the PBS-injected footpads.

Flow cytometry.

PECs were harvested by peritoneal lavage and washed three times in PBS. The cells were suspended to a concentration of 107 per ml in PBS containing 1% fetal calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide (PBS-azide). Fc receptors were blocked by treatment of cells with supernatant from the 2.4G2 hybridoma (ATCC HB197, anti-mouse Fcγ) for 15 min at room temperature. After this treatment the cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in a solution containing 10 μg of APC-labeled anti-F4/80 monoclonal antibodies per ml (1 μg/106 cells) and FITC-labeled anti-CD40, anti-B7-1, or anti-B7-2 suspended in PBS-azide. APC- or FITC-labeled isotype controls were included in the analysis of each cell population. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, the cells were pelleted and washed three times with PBS-azide. Finally the cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Two-color fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was carried out in the flow cytometry facility of the William K. Warren Medical Research Institute at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. A Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur four-color system with dual laser excitation was used for analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between experimental groups were evaluated by Student's t test. Data with a P value of 0.05 or lower were considered to be significantly different. Each experiment was performed at least twice.

RESULTS

Immunization with either GXM-APC or untreated APC enhances Th1 cytokine responses in C. neoformans-infected mice.

In a previous publication (5), we reported that immunization with GXM-APC, but not levan-APC, 1 week prior to infection with C. neoformans allowed mice to live longer after they were infected intratracheally. GXM-APC pretreatment allowed the mice to maintain their DTH responses when they were tested 2 weeks after infection, while naïve and levan-APC-pretreated mice had lost DTH reactivity. The prolonged survival of the GXM-APC-pretreated mice was associated with induction of a GXM-specific immune response that influenced the expression of the DTH reaction to a noncapsular cryptococcal skin test antigen.

The present study was designed to determine if GXM-APC, given prior to infection, could influence the development of anticryptococcal type-1 cytokine (IL-2 and IFN-γ), type-2 cytokine (IL-4 and IL-5), or immunosuppressive cytokine (IL-10), responses in CneF-stimulated spleen cells taken from mice infected with C. neoformans. In this investigation, spleen cells taken from experimental mice were restimulated in vitro with cryptococcal CneF antigen. While CneF contains the GXM, galactoxylomannan (GalXM), and mannoprotein fractions of C. neoformans, T-cell responses are directed at the mannoprotein fraction (25). In the present study, we speculated that alterations in the levels of T-cell-derived cytokines would influence the development of DTH reactions in GXM-APC-immunized mice after they were infected with C. neoformans.

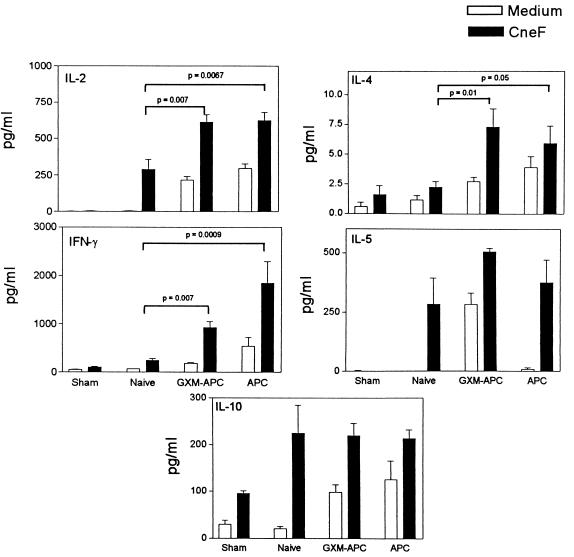

To examine the influence of GXM-APC immunization upon cytokine responses to C. neoformans infection, mice were treated with GXM-APC or APC alone 1 week prior to intratracheal infection with 104 NU-2 cells. Controls consisted of sham-treated mice, which were given 25 μl of PBS intratracheally (sham controls) at the time that other experimental groups were infected. One group of mice (naïve group) was infected without prior immunization. Spleen cells were harvested from individual mice (four to five per group) at days 10 and 15 of infection and were cultured in the presence of medium alone or medium containing CneF (cryptococcal skin test antigen) or ConA. Spleen cell cultures stimulated with ConA provided evidence that the cells remained viable under our tissue culture conditions and that they were capable of secreting each of the cytokines under study (data not shown). Cytokine levels were assayed in 24-h (IL-2) or 48-h (all other cytokines) culture supernatants by cytokine-specific ELISA. Peak cytokine responses occurred at day 10 and are shown in Fig. 1. Both type-1 cytokine (IL-2 and IFN-γ) levels and type-2 cytokine (IL-4 and IL-5) levels were increased in mice infused with GXM-APC, as well as in mice immunized with control APC that were not treated ex vivo with GXM. Statistically significant elevations in type-1 cytokines (IL-2 and IFN-γ) were consistently observed as a result of GXM-APC or APC administration (Fig. 1). Slight increases in type-2 cytokine responses (IL-4 and IL-5) were also consistently observed in repeated experiments, but these responses were not always statistically significant (Fig. 1). In addition, treatment of mice with GXM-APC or APC did not regulate the expression of the elevated IL-10 levels (Fig. 1) known to occur in mice infected with the cryptococcal isolate NU-2 (4). Constitutive (i.e., without CneF stimulation) cytokine secretion was routinely detected when spleen cells were obtained from GXM-APC- or APC-immunized mice, reflecting the in vivo response of the mice to their cryptococcal infection. In this experiment, constitutive secretion of IL-5 was not detected at day 10 but was apparent by day 15 (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Role of GXM-APC or APC immunizations in the development of cytokine responses in mice infected with C. neoformans. Experimental groups included sham-treated mice that were not immunized and were given PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Infected groups included naïve mice that were not immunized and mice immunized 1 week prior to infection with GXM-APC or APC alone. Peak responses shown occurred on day 10 after infection. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for four to five individual C57BL/6 mice.

Enhancement of type-1 cytokine responses and DTH reactions requires that GXM-APC be prepared with activated PECs.

In our previous investigation the immunomodulatory activity of GXM-APC was evaluated by using GXM-APC prepared with PECs obtained from normal mice injected 5 days previously with CFA. Because this adjuvant contains heat-killed mycobacteria, we have assumed, but never proven, that some of the effects of GXM-APC were due to activation of the PEC population by the mycobacteria. Considering that treatment with APC alone increased cytokine responses in the experiments described above, it was important to determine if the same results could be obtained with a PEC population that was obtained without the presence of mycobacteria.

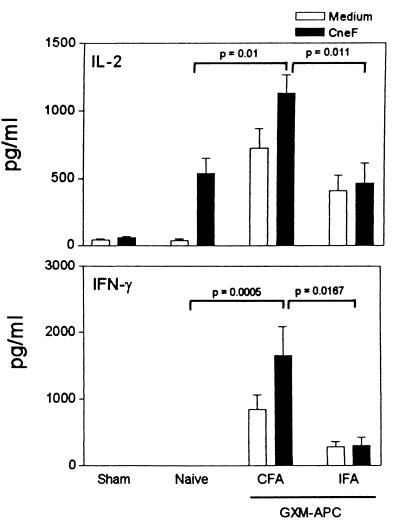

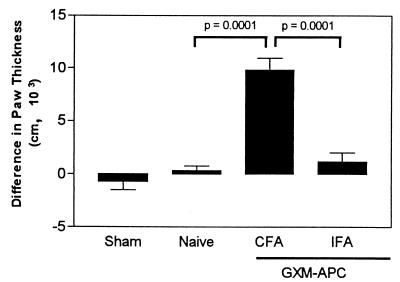

For these experiments, GXM-APC were prepared from PECs obtained from mice that were injected intraperitoneally with CFA and compared to GXM-APC prepared from PECs of mice injected intraperitoneally with IFA. One week after GXM-APC immunization, the mice were infected intratracheally with 104 NU-2 cells. Sham-infected and naïve groups were included. On the 10th and 15th days after infection, the spleens of the mice were removed and cultured in the presence or absence of CneF. IL-2 and IFN-γ levels were assayed in culture supernatants. Peak responses occurred at day 10 and are shown in Fig. 2. Pretreatment of mice with GXM-APC prepared from the PECs that were induced with CFA increased IL-2 and IFN-γ responses, as we observed in previous experiments. However, IL-2 and IFN-γ levels were significantly reduced when the PECs were obtained from mice injected with IFA. The results were confirmed by analysis of DTH reactions in mice immunized with GXM-APC prepared with PECs induced with CFA or IFA. GXM-APC prepared with CFA-induced PECs enhanced DTH reactions in infected mice, whereas GXM-APC prepared from IFA-induced PECs had no effect (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Role of the PEC source in augmenting type-1 cytokine responses in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Experimental groups included sham-treated mice that were not immunized and were given PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Infected groups included naïve mice that were not immunized and mice immunized 1 week prior to infection with GXM-APC prepared with CFA-induced PECs (CFA) or with GXM-APC prepared with IFA-induced PECs (IFA). Peak responses that occurred on day 10 after infection are shown. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for four to five individual C57BL/6J mice.

FIG. 3.

Role of the PEC source in augmenting DTH reactions in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Sham-treated mice were not immunized and were given PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Infected groups included naïve mice and mice immunized with GXM-APC prepared from PECs induced with CFA or from PECs induced with IFA. Mice were skin tested with cryptococcal CneF 16 days after infection. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for six to seven individual C57BL/6J mice.

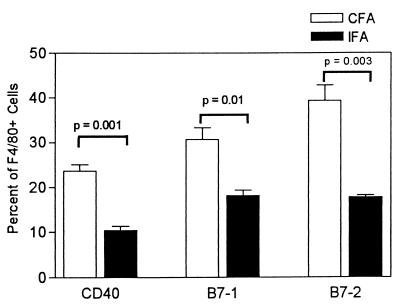

Expression of costimulatory molecules on CFA-induced and IFA-induced PECs.

The PECs induced with CFA and IFA were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine if they expressed markers characteristic of activated cells. Three mice were injected with 0.5 ml of CFA, and three mice were injected with 0.5 ml of IFA. Five days later, PECs were harvested from individual mice and analyzed for the expression of CD40, B7-1, and B7-2 on cells in the exudates that expressed the macrophage marker F4/80. The data are shown in Fig. 4. Among the CFA-induced PEC population, 48.3 ± 3.0% of cells expressed the F4/80 marker, while 33.9 ± 1.7% of the IFA-induced PECs were F4/80+. By light scatter analysis about 80% of the cells in both groups were macrophages (data not shown). In the F4/80-positive subset, the numbers of cells that expressed CD40, B7-1, and B7-2 were statistically greater (P = 0.001, 0.01, and 0.003, respectively) in the PEC population induced with CFA than in the PEC population induced with IFA. The mean fluorescence intensities of the positive cells were not different in CFA- and IFA-induced exudates (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Phenotype of F4/80-positive cells in CFA-induced and IFA-induced PECs. Peritoneal cells were harvested 5 days after injection of 0.5 ml of nonemulsified CFA or IFA. F4/80+ cells from three mice per group were analyzed for the expression of CD40, B7-1, or B7-2 by two-color flow cytometric analysis. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for three individual C57BL/6 mice.

Increased IFN-γ responses in C. neoformans-infected mice are not due to secretion of IL-12 by the activated APC.

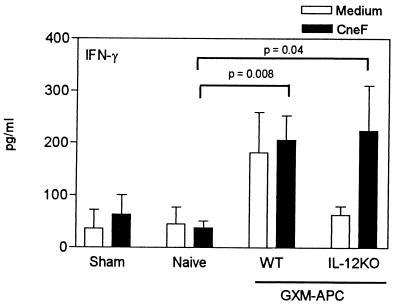

Due to the fact that peritoneal exudates used as the source of APC were elicited with CFA, it was possible that the APC secreted IL-12 and that this was responsible for increasing the type-1 cytokine response in our experiments. This could explain why APC augment cytokine levels in the absence of GXM. To examine this possibility, APC were obtained from mice that have an induced mutation in the IL-12 p40 gene (IL-12 knockout mice). IL-12 knockout mice and their wild-type (IL-12-sufficient) counterparts were injected with CFA. Five days later, PECs were harvested from these mice and used to prepare GXM-APC. The GXM-APC were used to immunize normal, IL-12-sufficient mice, and the recipient mice were infected with C. neoformans 1 week after immunization. Spleen cells were removed 10 and 15 days after infection and were cultured in the presence or absence of CneF. Culture supernatants were assayed for IFN-γ. In the experiment for which results are shown in Fig. 5, peak responses occurred at day 10. IFN-γ responses of mice immunized with GXM-APC derived from wild-type and IL-12 knockout mice were significantly elevated (P = 0.008 and P = 0.04, respectively) compared to responses of naïve mice that were not immunized but were infected with NU-2. IFN-γ levels in CneF-stimulated spleen cell culture supernatants obtained from mice immunized with GXM-APC prepared with PECs from IL-12 knockout mice were not different from those in similar cultures prepared from spleen cells of mice immunized with GXM-APC prepared with IL-12-sufficient APC (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Role of APC-derived IL-12 in augmenting IFN-γ responses in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Experimental groups included sham-treated mice that were not immunized and were given PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Infected groups included naïve mice that were not immunized and mice immunized 1 week prior to infection with GXM-APC prepared from CFA-induced PECs obtained from wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice or from IL-12 knockout (IL-12KO) mice. Peak responses that occurred on day 10 after infection are shown. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for four to five individual C57BL/6J mice.

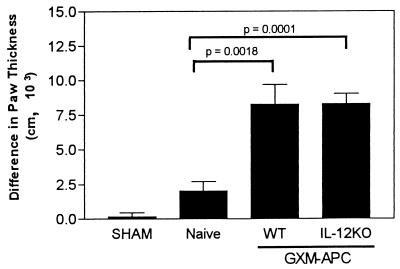

Elevated DTH reactions in C. neoformans-infected mice were not caused by secretion of IL-12 by the APC.

The role of APC-derived IL-12 was further evaluated for its ability to influence the development of the DTH reaction after infection of immunized mice. One week after infusion of the GXM-APC (derived from wild-type or IL-12 knockout mice), the immunized mice were infected with 105 C. neoformans NU-2 organisms intratracheally. Sham-treated control mice were given 25 μl of PBS intratracheally on the day of infection. Naïve controls (not pretreated with GXM-APC) were infected with NU-2. On the 16th day of infection, the mice were skin tested with the soluble cryptococcal skin test antigen (CneF), and their DTH responses were measured 24 h later. The data presented in Fig. 6 reveal that significant increases in DTH reactions occurred when wild-type APC (P = 0.0018) and IL-12 knockout APC (P = 0.0001) were infused 1 week prior to infection with C. neoformans NU-2. The two responses were not significantly different from one another.

FIG. 6.

Role of APC-derived IL-12 in augmenting DTH reactions in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Sham-treated mice were not immunized and were given PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Infected groups included naïve mice and mice that were immunized with GXM-APC prepared from wild-type (WT) PECs or PECs from IL-12 knockout mice (IL-12KO). Mice were skin tested with cryptococcal CneF 16 days after infection. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for four to seven individual C57BL/6 mice.

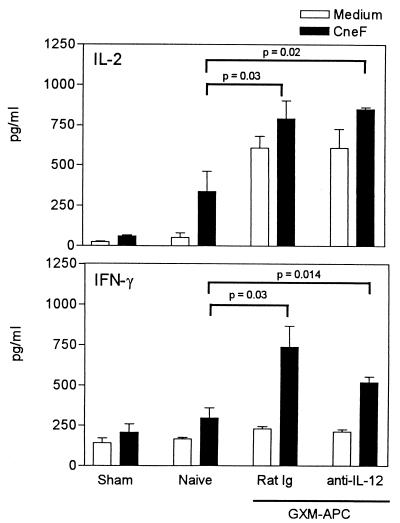

Treatment of recipient mice with anti-IL-12 does not decrease the type-1 cytokine responses that develop in infected mice immunized with GXM-APC.

Although it was apparent that the non-antigen-specific effects of GXM-APC immunization were independent of APC-derived IL-12, it was still possible that the infused APC population induced the production of IL-12 in recipient animals. The induced IL-12 response could then be responsible for increasing type-1 cytokine responses in infected animals. To examine this possibility, recipient mice were treated with 100 μg of anti-IL-12 or 100 μg of normal rat immunoglobulin 1 h prior to infusion of GXM-APC. The dose of anti-IL-12 used in these experiments was previously shown to block increased serum levels of IL-12 induced by administration of endotoxin to mice (data not shown). In these experiments, control groups included sham-infected (PBS given intratracheally) mice and mice that were infected without immunization (naïve). At various times after infection, spleen cells were harvested from experimental animals and cultured in the presence or absence of the cryptococcal CneF antigen. IL-2 and IFN-γ levels were measured in supernatants of control and CneF-stimulated spleen cell cultures. The results of a representative experiment are seen in Fig. 7. In this experiment the peak response occurred at day 10. Treatment of recipient animals with anti-IL-12 just prior to GXM-APC infusion did not diminish the IL-2 or IFN-γ responses that developed in these mice 10 days after they were infected with NU-2. Levels of both IL-2 and IFN-γ were significantly elevated (P = 0.02 and P = 0.01, respectively) in anti-IL-12-treated, GXM-APC-immunized mice compared to those in naïve infected mice. In addition, the levels of these cytokines in anti-IL-12-treated mice were not significantly different from those that developed in GXM-APC-immunized mice that were treated with rat immunoglobulin.

FIG. 7.

Role of APC-induced IL-12 secretion in augmenting Th1 cytokine responses in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Open bars, spleen cells cultured in medium. Solid bars, spleen cells cultured in medium containing cryptococcal CneF antigen. Experimental groups included sham-treated mice that were not immunized and were given PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Infected groups included naïve mice that were not immunized and mice immunized 1 week prior to infection with GXM-APC. Experimental mice were treated with normal rat immunoglobulin (Rat Ig) or with monoclonal anti-mouse IL-12 (anti-IL-12) 1 h prior to immunization with GXM-APC. Peak responses, which occurred on day 10 of infection, are shown. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for four to five individual C57BL/6J mice.

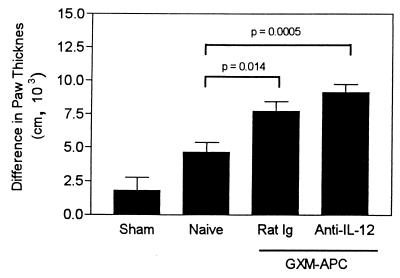

Treatment of recipient mice with anti-IL-12 does not decrease DTH responses that develop in infected mice immunized with GXM-APC.

The effect of administration of anti-IL-12 to GXM-APC-immunized mice was tested for its participation in the augmented DTH reactions found in GXM-APC-immunized mice. The results of a typical experiment are shown in Fig. 8. Blocking of IL-12 activity with anti-IL-12 at the time of immunization with GXM-APC had no effect on the level of DTH reactivity detected 21 days postinfection. DTH reactions were significantly elevated in the anti-IL-12-treated mice (P = 0.0005 compared to reactions in naïve mice), and the responses were not significantly different from DTH reactions detected in GXM-APC-immunized mice treated with normal rat immunoglobulin.

FIG. 8.

Role of APC-induced IL-12 secretion in augmenting DTH reactions in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Sham-treated mice were not immunized and were treated with PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Naïve mice were not immunized but were infected. GXM-APC-immunized mice were treated with normal rat immunoglobulin (Rat Ig) or with monoclonal anti-mouse IL-12 (anti-IL-12) 1 h prior to immunization. Mice were skin tested with cryptococcal CneF 21 days after infection. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for five to seven individual CBA/J mice.

DISCUSSION

We reported previously that a vaccine composed of APC pulsed ex vivo with purified cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide (GXM-APC) enabled mice to survive longer when they were challenged intratracheally with the highly virulent C. neoformans isolate NU-2 (5). The protective effect was not present when the APC were pulsed ex vivo with a non-cross-reacting polysaccharide, levan. In addition, infected mice that were immunized with GXM-APC maintained their DTH responses to a noncapsular cryptococcal antigen longer than mice that were treated with levan-APC or mice that received no pretreatment. In this model, the DTH response was correlated with protective immunity. In the present study, we determined that the GXM-APC immunization regimen enhanced the development of splenic type-1 cytokine responses that developed after the mice were challenged with a cryptococcal infection. Since these cytokine responses are correlated with protective immunity in cryptococcosis (1), we initially speculated that GXM-APC-immunized mice would produce more IL-2 and IFN-γ than APC-immunized mice. However, levels of these type-1 cytokines were significantly elevated in CneF-stimulated spleen cell cultures of GXM-APC-immunized mice as well as in similar spleen cell cultures of mice immunized with APC that were not pulsed with GXM. Generally, both constitutive secretion of cytokine by the cultured spleen cells and CneF-stimulated cytokine levels were increased, reflecting the enhanced response of the immunized groups to subsequent cryptococcal infection.

Because administration of APC prior to infection does not confer protection (5), we must conclude that a second response, specific to GXM, is responsible for allowing the GXM-APC immunized mice to live longer. The only correlate of immunity that we have detected to date is the ability of GXM-APC-immunized animals to maintain their DTH responses longer than APC-immunized mice (5). Because GXM is a pure polysaccharide, CD4+ T cells do not respond to this antigen (unpublished observations). T cells do respond to other protein-containing antigens of C. neoformans, especially the mannoprotein constituents of the organism (25). Therefore, our data suggest that a GXM-specific response plays a role in regulation of the expression of the DTH reactions directed at protein-containing cryptococcal antigens. We previously reported that anti-GXM responses are capable of down-regulating delayed-type reactions to antigens other than GXM by triggering the release of non-antigen-specific regulatory molecules (9). We also reported that GXM-APC immunization inhibits these suppressive responses (5). Therefore, inhibition of the suppressive response would be expected to up-regulate DTH reactions elicited by protein-containing antigens of C. neoformans. Obviously, APC-treated mice did develop a type-1 response after they were infected. However, the APC-induced response does not confer protection (5). We speculate that the immunosuppressive properties of GXM function to inhibit the activity of sensitized T cells in the APC-immunized group. The mechanism for this inhibition could be inhibition of migration of sensitized lymphocytes from the lymphoid tissues (spleen and lymph nodes) to infected tissues or to DTH reaction sites. Alternatively, GXM-specific regulatory cells could inhibit the activity of the immune effector cells after they enter an infected tissue or a DTH reaction site. Mechanisms that regulate contact sensitivity reactions (i.e., delayed-type reactions) to haptens support the hypothesis that one or both of these suggested mechanisms could be functional in mice infected with NU-2 (3).

Although type-2 cytokine responses (IL-4 and IL-5) were consistently increased in spleen cell cultures established from GXM-APC- and APC-treated mice, these increases were modest and were not always statistically significant. We previously reported that increased antibody synthesis could not account for the increased survival observed in GXM-APC-immunized mice (5). The amount of IL-10 detected in supernatants of CneF-stimulated spleen cells was not increased or decreased compared to that from mice that were infected without prior immunization. The inability of the GXM-APC immunization procedure to regulate IL-10 levels reveals a need for future immunoregulatory treatments to include methods of decreasing IL-10 levels in infected hosts. We previously reported that IL-10 contributes to decreased survival of NU-2-infected mice (4) and that immunization with GXM-APC prolongs survival but does not provide complete immunity (5). Part of the reason for the latter observation could be the continued presence of IL-10 in the GXM-APC-immunized mice.

We believe that the nonspecific immunomodulatory activity of the infused APC population and the GXM-specific response are both needed to allow GXM-APC to confer protection. This belief is predicated on the knowledge that IFN-γ is essential for the development of DTH responses (15) and for protection against C. neoformans infection (2, 17). The experiments described in this report show that the infused APC population must be activated before the GXM-APC immunization is effective in increasing DTH and cytokine responses. If IFN-γ responses were not present in lymphoid tissues from these mice, then DTH reactions would not develop, as they have been shown to be dependent upon the development of type-1 responses in models of cryptococcosis (23). For this reason, it is of interest to define the mechanisms that allow the activated APC population to increase the type-1 response; this knowledge will enhance development of future immunotherapies for this infection. As discussed above, the therapies should also contain methods to inhibit IL-10 activity.

The signals provided by the APC population that allow mice to respond to a subsequent cryptococcal infection with improved IFN-γ responses have not been fully defined. However, this investigation showed that the mycobacteria must be present in the CFA used to elicit the APC from normal donor mice, as PECs obtained from IFA-injected peritoneal cavities were not effective. Activated APC are characterized by enhanced expression of a variety of molecules necessary for effective antigen presentation. These include the costimulatory molecules CD40, B7-1 (CD80), and B7-2 (CD86), which are up-regulated on these cells (28). The finding that more cells express these molecules among PECs induced with CFA than among PECs induced with IFA indicated that the state of activation of the infused APC was important for induction of the nonspecific response elicited by the GXM-APC vaccination.

Because other investigators (20) have reported that IL-12 can enhance IFN-γ responses in mice infected with a highly virulent C. neoformans isolate, it seemed probable that IL-12, secreted by the activated APC population, might be responsible for the nonspecific immunostimulatory effects of GXM-APC. Our experiments showed that the infused APC need not secrete IL-12 to exert their stimulatory effects, because APC derived from IL-12-deficient mice were as effective as APC harvested from wild-type, IL-12-sufficient mice in preparing mice to respond to infection with the development of type-1 cytokine responses. The results do not rule out the possibility that the APC may stimulate the cells of recipient mice to secrete IL-12 and that this source of IL-12 is responsible for the immunomodulatory effects of the APC. In this study, treatment of GXM-APC-immunized mice with anti-IL-12 did not alter the immunomodulatory activity of the vaccine. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that IL-12, secreted after the first couple of days after immunization, might play a role in our system, because we did not treat our recipient animals with anti-IL-12 for a prolonged period of time. The activated APC used in these experiments may differ in many ways from nonactivated APC, including levels of other proinflammatory cytokines secreted and levels of costimulatory molecules expressed. One or several of these factors could be responsible for inducing the nonspecific immunostimulatory response found in our experiments.

In high doses, IL-18 provides protection to cryptococcus-infected mice, and in lower doses, IL-12 and IL-18 act in a synergistic manner to enhance immunity in a murine model of cryptococcosis (19, 20). Because the dose of IL-18 required to provide immunity when given as a single agent is 10 μg per day, it seems unlikely that the APC injected in this study would provide this amount of cytokine. Therefore, a synergistic interaction between IL-12 and IL-18 is likely to be responsible for the immunomodulatory effects of the APC treatment. In this study, if IL-12 and IL-18 had been acting in a synergistic manner, treatment with anti-IL-12 should have abrogated the immunomodulatory effect. This was not seen in our experiments.

A third cytokine that we have not yet studied, tumor necrosis factor alpha, is also known to be essential for the induction of protective immunity against cryptococcal infection (18). In addition to secretion of soluble cytokines, membrane-associated molecules of the activated APC, including the costimulatory molecules B7-1, B7-2, and CD40, could provide immunostimulatory effects due to their ability to directly stimulate natural killer cells, which subsequently secrete IL-12 and IFN-γ (16, 21, 31). Our current investigations are directed at determining the role that these factors play in inducing the nonspecific and GXM-specific effects of GXM-APC immunization.

In this paper the GXM-APC treatment is referred to as an immunization because it was given before infection with cryptococci. Our studies with this immunization are intended to study the mechanisms whereby the immunosuppressive consequences of GXM can be regulated and are not intended to promote GXM-APC as a vaccine. We believe that an understanding of these mechanisms and the methods that are effective in inhibiting the response will contribute to the development of future vaccines that include methods to induce this GXM-specific immunoregulatory response. Because regulatory responses directed at the capsule of C. neoformans are able to inhibit protective responses directed at other cryptococcal components such as the mannoprotein fraction (9, 10, 25), methods to inhibit the ability of GXM to down-regulate cell-mediated immunity should be included in any future vaccine design. After the mechanism(s) for the induction of the GXM-specific and nonspecific responses are fully elucidated, it may be possible to design a vaccine that provides appropriate signals without a need for activated APC. Future vaccines should also be designed to increase immune responses directed at other cryptococcal constituents, such as those found in the mannoprotein fraction of cryptococcal culture filtrates. In addition, it is possible that some of these strategies could be included in future immunotherapies for cryptococcosis, such as those provided by activated APC. Such treatments should focus on inhibiting the ability of GXM to inhibit DTH reactions (9), augmenting cell-mediated immunity, and inhibiting IL-10 secretion (4, 29).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-43325 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by a grant from the Presbyterian Health Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguirre K M, Gibson G W, Johnson L L. Decreased resistance to primary intravenous Cryptococcus neoformans infection in aged mice despite adequate resistance to intravenous rechallenge. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4018–4024. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4018-4024.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre K, Havell E A, Gibson G W, Johnson L L. Role of tumor necrosis factor and gamma interferon in acquired resistance to Cryptococcus neoformans in the central nervous system of mice. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1725–1731. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1725-1731.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asherson G L, Colizzi V, Zembala M. An overview of T-suppressor cell circuits. Annu Rev Immunol. 1986;4:37–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackstock R, Buchanan K L, Adesina A M, Murphy J W. Differential regulation of immune responses by highly and weakly virulent Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3601–3609. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3601-3609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackstock R, Casadevall A. Presentation of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide (GXM) on activated antigen presenting cells inhibits the T-suppressor response and enhances delayed-type hypersensitivity and survival. Immunology. 1997;92:334–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackstock R, Hall N K. Nonspecific immune suppression by Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Mycopathologia. 1984;86:35–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00437227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackstock R, Hall N K, Hernandez N C. Characterization of a suppressor factor that regulates phagocytosis by macrophages in murine cryptococcosis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1773–1779. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1773-1779.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackstock R, McCormack J M, Hall N K. Induction of a macrophage-suppressive lymphokine by soluble cryptococcal antigens and its association with models of immunological tolerance. Infect Immun. 1987;55:233–239. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.233-239.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackstock R, Zembala M, Asherson G L. Functional equivalence of cryptococcal and haptene-specific T-suppressor factor (TsF). II. Monoclonal anti-cryptococcal TsF inhibits both phagocytosis by a subset of macrophages and transfer of contact sensitivity. Cell Immunol. 1991;136:448–461. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90366-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackstock R, Zembala M, Asherson G L. Functional equivalence of cryptococcal and haptene-specific T-suppressor factor (TsF). I. Picryl and oxazolone-specific TsF, which inhibit transfer of contact sensitivity, also inhibit phagocytosis by a subset of macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1991;136:435–447. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90365-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchanan K L, Murphy J W. Characterization of cellular infiltrates and cytokine production during the expression phase of the anticryptococcal delayed-type hypersensitivity response. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2854–2865. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2854-2865.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casadevall A, Perfect J R. Cryptococcus neoformans. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis J L, Huffnagle G B, Chen G H, Warnock M L, Gyetko M R, McDonald R A, Scott P J, Toews G B. Differences in pulmonary inflammation and lymphocyte recruitment induced by two encapsulated strains of Cryptococcus neoformans. Lab Investig. 1994;71:113–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubois M, Gilles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fong T A, Mosmann T R. The role of IFN-gamma in delayed-type hypersensitivity mediated by Th1 clones. J Immunol. 1989;143:2887–2893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grewal I S, Flavell R A. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoag K A, Lipscomb M F, Izzo A A, Street N E. IL-12 and IFN-γ are required for initiating the protective Th1 response to pulmonary cryptococcosis in resistant C.B-17 mice. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:733–739. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.6.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huffnagle G B, Strieter R M, McNeil L S, McDonald R A, Burdick M D, Toews G B. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Cryptococcus and Cryptococcosis. 1996. The role of TNF and melanin in modulating the development of protective T-cell-mediated immunity in the lungs to C. neoformans; p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawakami K, Qureshi M H, Zhang T, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Saito A. IL-18 protects mice against pulmonary and disseminated infection with Cryptococcus neoformans by inducing IFN-γ production. J Immunol. 1997;159:5528–5534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawakami K, Tohyama M, Zie Q, Saito A. IL-12 protects mice against pulmonary and disseminated infection caused by Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104:208–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.14723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin-Fontecha A, Assarsson E, Carbone E, Carre K, Ljunggren H-G. Triggering of murine NK cells by CD40 and CD86 (B7-2) J Immunol. 1999;162:5910–5916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan M A, Blackstock R, Bulmer G S, Hall N K. Modification of macrophage phagocytosis in murine cryptococcosis. Infect Immun. 1983;40:493–500. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.493-500.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy J W. Cytokine profiles associated with induction of the anticryptococcal cell-mediated immune response. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4750–4759. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4750-4759.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy J W. Cell-mediated immunity. In: Howard D H, Miller J D, editors. The Mycota. VII. Animal and human relationships. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 67–97. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy J W, Mosley R L, Cherniak R, Reyes G, Kozel T R, Reiss E. Serological, electrophoretic, and biological properties of Cryptococcus neoformans antigens. Infect Immun. 1988;56:424–431. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.424-431.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak T P, Barondes S H. Agglutinin from Limulus polyphemus. Purification with formalinized horse erythrocytes as the affinity adsorbent. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;393:115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson B E, Hall N K, Bulmer G S, Blackstock R. Suppression of responses to cryptococcal antigen in cryptococcosis. Mycopathologia. 1982;80:157–163. doi: 10.1007/BF00437578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santin A D, Hermonat P L, Ravaggi A, Chiriva-Internati M, Cannon M J, Hiserodt J C, Pecorelli S, Parham G P. Expression of surface antigens during the differentiation of human dendritic cells vs macrophages from blood monocytes in vitro. Immunobiology. 1999;200:187–204. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(99)80069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vecchiarelli A, Retini C, Monari C, Tascini C, Bistoni F, Kozel T. Purified capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans induces interleukin-10 secretion by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2846–2849. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2846-2849.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson J L, Charo J, Martin-Fontecha A, Dellabona P, Casorati G, Chambers B J, Kiessling R, Bejarano M-T, Lunggren H-G. NK cell triggering by the human costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. J Immunol. 1999;163:4207–4212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wysocka M, Kubin M, Vieira L Q, Ozmen L, Garotta G, Scott P, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 is required for interferon-γ production and lethality in lipopolysaccharide-induced shock in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:672–676. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]