Abstract

Due to the results of the COVID-19 epidemic on health, the positive effect of social distancing has been highlighted. Nevertheless, the effect of housing layouts on resident’s perceived behavioral control over social distancing in shared open spaces have been rarely investigated in the context of pandemic. Filling this gap, the current study examines the moderating effect of perceived behavioral control on the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress. Data from 1349 women residing in 9 gated communities during the Iranian national lockdown were collected. The results of ANOVA indicate that there is a significant difference between various housing layouts in terms of residents’ perceived behavioral control. Respondent in courtyard blocks layout reported higher perceived behavioral control over social distancing than in linear and freestanding blocks. The findings of structural equation modeling identified perceived behavioral control as a buffer against the effect of social isolation on psychological distress.

Keywords: Residential environments, Housing layout, Social isolation, Psychological distress, Perceived behavioral control, PLS

Introduction

The global outbreak of coronavirus disease, which began in 2019, has a tremendous impact on quality of life and health of all people (Díaz de León-Martínez et al., 2020). This pandemic has had a direct impact on recent sustainability notions, emphasizing the resilience of systems and their ability to recover from disruptions (Tahvonen & Airaksinen, 2018). Sustainability in urban planning began with a focus on development management, compact areas, and decentralization (Khavarian-Garmsira et al., 2021). The current pandemic has raised doubts regarding the desirability of compact urban development and defined planning aims to promote urban life and citizens' well-being (Hakovirta & Denuwara, 2020; Megahed & Ghoneim, 2020).

Well-being is linked not just to the environment through the dangers of pollution exposure, but also to mental health (Díaz de León-Martínez et al., 2020). COVID-19 became a global pandemic and caused a variety of precautionary measures, including national quarantines and stay-at-home orders (Olszewska-Guizzo et al., 2021). Social isolation and loneliness have been linked to poorer mental health outcomes such as cognitive decline, anxiety, depression, and psychological distress in previous studies (Brooks et al., 2020; Gorenko et al., 2021; Pakenham et al., 2020). The effects of environmental factors on people’s health have been extensively researched (Hadavi, 2017; Wells & Harris, 2007) but their relationship to COVID-19 is still a work in progress (Viezzer & Biondi, 2021). As a result, we must find ways to mitigate the pandemic’s adverse mental health effects and the resulting lockdowns in residential areas (Allam & Jones, 2020).

While pandemic-related restrictions compelled people to stay home with their families or cohabitants, the physical and built environment has a direct impact on human health, both within the structures in which we live and through the open spaces that connect these buildings (Jens & Gregg, 2021). An increasing amount of data supports the importance of access to open and green spaces in promoting urban sustainability and improving human health (Ahmadpoor & Shahab, 2020; Gascon et al., 2015; Kim & Miller, 2019; Olszewska-Guizzo et al., 2020). The study of access to and utilization of open spaces while maintaining social distance is becoming increasingly important in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The theory of planned behavior provides a theoretical framework for investigating how the multidimensional idea of accessibility might explain and predict people's behavioral intentions to use shared open spaces.

During the COVID-19 epidemic, fewer studies are looking into the impact of housing layout, perceived behavioral control over social distancing, and people's mental health. Due to constraints on outside activities, it is critical in the COVID-19 context to reduce the crowding of shared open spaces where people spend their time (Kim & Kang, 2021). This emphasizes the need of attempting to increase control over social distancing and separation in these spaces. The issue's practical implication is that perceived behavioral control over social distancing can be altered by the built environment’s characteristics. It is necessary to have a good grasp of how people's mental health is affected by experiences of physical distancing in different housing layouts. By conducting empirical research in Mashhad, Iran, and studying the link between social isolation and psychological distress, this study intends to fill current gap in the literature. The first goal of this research was to compare perceived behavioral control over social distancing in different housing layouts. Second, it is hypothesized that perceived behavioral control to maintain social distance in shared open spaces will moderate the effect of social isolation on psychological distress.

Literature review

Social isolation and mental health during pandemic

Subjective well-being is defined as the recognition of one’s skills, coping with general life stress, working effectively and productively, contributing to society, and forming satisfactory relationships with others (Hatun & Kurtça, 2022). While well-being is described as a combination of feeling well and functioning effectively, it also includes dealing with negative emotions, which are a part of life. For instance, psychological distress as an indicator of mental health and well-being is largely defined as a state of emotional suffering characterized by symptoms of depression and anxiety (Baxter et al., 2021).

Over the past several decades, researches have documented the long-term health effects of social relationships. Social relationships affect health and well-being via fulfilling a variety of physical, emotional, and cognitive needs. By reducing the opportunity for these needs to be met (Holt-Lunstad & Stoptoe, 2022) social isolation is a significant threat to the health and well-being (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2003; Olszewska-Guizzo et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2016; York Cornwell & Waite, 2009). Researches have increasingly focused on social isolation as being comprised of two separate constructs identified as objective and subjective social isolation. Objective social isolation represents the tangible aspects of social isolation represented by physical separation from and an absence or deficiency of interaction with other people. Subjective social isolation, however, is defined as an individual’s perceptions and quality of his/her relationships with members of his/her social networks, as well as perceived integration and involvement in social networks (Valtorta et al., 2016). Based on previous findings, both social isolation due to physical distancing (e.g., Hyun-soo & Jung, 2021) and subjective social isolation (e.g., Taylor et al., 2016) are associated with greater levels of psychological distress.

Individual pathology is conditioned by social dynamics, according to a traditional Durkheimian approach, and large-scale social crises may have a negative impact on individual health and well-being by reducing social integration (Durkheim, [1897] 1951, cited by Berkman et al., 2000). The threat of COVID-19 predicted both decreased people’s subjective well-being and increased distress. In the Iranian context, some research (e.g., Zandifar & Badrfam, 2020) highlighted the role of unpredictability, uncertainty, seriousness of the disease, and social isolation in contributing to stress and mental morbidity. Similarly, there is considerable evidence of associations between social isolation and psychological distress during pandemic (e.g., Gorenko et al., 2021; Hyun-soo & Jung, 2021).

The theory of planned behavior (TPB)

The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and its extension, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), are the most well-known theories for predicting human behavioral intentions (Rhodes et al., 2006) and subsequent behaviors in a variety of disciplines, including social psychology and environmental studies (Armitage & Conner, 2001).

The motive that leads to engagement in a particular behavior, behavioral intention, is essential to the TRA model (Ajzen, 2002). According to this concept, attitude and subjective norm are two important aspects determining a person's desire to behave, and behavioral intention then influences actual behavior performance. The amount to which an individual senses public social pressure—from others such as friends and family members—towards the propriety of performing the conduct is referred to as subjective norm (Rossi & Armstrong, 1999). The primary premise of TRA is that individuals have control over their actions (Armitage & Conner, 2001). Internal elements like knowledge and abilities, as well as external factors like convenience, can constrain or facilitate a behavior (Wan & Shen, 2015). TPB, as a condensed theory proposed by Ajzen (1991), incorporates the most critical aspects in understanding various behaviors. The TRA model now includes a new feature called Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC). The perceived ability and ease with which an individual can do a given activity is referred to as PBC (Wang et al., 2015, p. 86). The efficacy of TPB in explaining behaviors has been well-proven (Armitage & Conner, 2001). TPB has also been applied in predicting behaviors to use urban green spaces by Wan and Shen (2015). The use of public facilities is related to perceived accessibility because every individual or household perceives access to urban facilities such as shared open spaces (Zondag & Pieters, 2005). Subjective measures are essential because the willingness to act or avoid action results from a collective evaluation of objective attributes (Wang et al., 2015).

Housing policies and layouts in Iran

Unlike European and North American countries, many rapidly growing cities in developing countries have high residential densities already. In the context of Iranian cities, the emergence of high-density developments has been accompanied by the heterogeneity of urban residents who demand diverse living spaces due to their varied social-cultural structures. During the last thirty years, encouraging the construction of apartment buildings in the form of enclave communities for specific groups (public servants) was the main housing policy and gated communities gradually became a marketing opportunity for private housing developers concerning the middle-income group (Mousavinia, 2022). According to the limited size of dwelling units, and based on the history of Iranian life relayed on the private yard; open spaces provide an opportunity to encourage social activities. Open spaces are vital components of housing layout including balconies, gardens, and communal areas. They can be used to define the borders between dwellings and the separation between neighboring houses in addition to allowing the penetration of sunlight and fresh air (Payami Azad et al., 2018). There are three dominant types of housing layout in Iranian gated communities: centralized courtyard, freestanding, and linear blocks (Einifar & Ghazizadeh, 2011).

Courtyard blocks (apartments in periphery blocks with shared open space)

In this layout, semi-private courtyards are introduced into the center of the blocks where residents, for example, can relax and children can play. Such a space allows apartment residents access to outdoor space which is managed for the block as a whole.

Freestanding blocks

This housing layout provides new and unconstrained open spaces around the homes offering air and light. Today this arrangement still remains relevant in particular where people tend to live in apartments, and a demand for outdoor private garden space is less prevalent. On certain sites freestanding blocks provide the most effective mechanism for achieving the desired density of development.

Linear block arrangements

This arrangement is a configuration of apartments reflecting the fact that orientation of living space to the sun is given a high priority and the houses face each other across a street (Biddulph, 2007).

Study design

Given that residents in a pandemic situation must maintain social distance from others, it is expected that they will react more emotionally to environmental limits. We hypothesized that there is a difference between residents’ perceived behavioral control over social distancing in different housing layouts (H1).

TPB is a flexible model that may be tailored to suit research needs. The fundamental pathways and variables can be modified and expanded to satisfy research needs using this user-friendly model. We investigate the role of perceived behavioral control in the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress using the TPB model. Based on previous studies, it is expected that social isolation has a direct impact on psychological distress (H2). Another goal of this research is to see if perceived behavioral control over social distancing in shared open spaces could help to mitigate the adverse effects of social isolation on psychological distress, thereby acting as a buffer against potential environmental stressors. The effect of social isolation on psychological distress would be moderated by perceived behavioral control over social distancing in shared open spaces (H3).

Methods

Study area

Housing quality and living conditions were substantial predictors of the ward level COVID-19 mortality count (Hu et al., 2021). Also, there is considerable association between housing quality and psychological distress or mental health (Wells & Harris, 2007). The study focused on nine dense gated communities in Mashhad, Iran's second-largest city, with comparable housing quality. The areas were chosen based on middle-income status, housing rate, comparable residential and population density, the amount of green space in the community areas, and various housing layouts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Case study areas

| Housing layout | Photos | Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central courtyard blocks (n = 463) |  |

|

n = 167 |

|

|

n = 142 | |

|

|

n = 154 | |

| Linear blocks (n = 432) |  |

|

n = 154 |

|

|

n = 147 | |

|

|

n = 131 | |

| Freestanding blocks (n = 454) |  |

|

n = 153 |

|

|

n = 156 | |

|

|

n = 145 | |

Participants and data collection

Iran has had five peaks of the Corona pandemic and its associated quarantine. Due to the significant spread of the Delta version of COVID-19, severe lockdown lasted over 10 days, from August 12 to August 21, 2021. People were forced to spend the entire day and night indoors with their family or cohabitants, leaving only for fundamental reasons. Participants were solicited via telegram groups to which inhabitants of the gated residential neighborhoods are members. Respondents received a message with the survey URL and an explanation that participation in the survey was voluntary to complete an online survey questionnaire. They were demanded to take an online survey about mental health outcomes and perceptual characteristics. To assure data quality, human verification and attention checks were used throughout the survey.

Based on previous research on factors associated with psychological well-being, demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, education, household income, employment status, and occupation) were considered potential confounders of the relationship between perceptions and psychological well-being (Cleary et al., 2019; Cutrona et al., 2000). Gender role theories as a reference in health studies suggest that men and women have separate roles due to their differentiated socialization. Gender determines the constraints and opportunities based on sex categories. Additionally, according to the stress process model, the higher proportion of psychological distress among women results from their greater exposure to stressors and their access to fewer resources than men (Bilodeau et al., 2020). Given the cultural context and the role of women in maintaining family order during the epidemic, data were collected from women.

A Participant Information Sheet included information on gender, education background, known mortality cases in neighbors, colleagues, or family members involved, and pre-lockdown emotional-mental health at the start of the questionnaire. The latter was assessed with a single question: “In general, would you describe your emotional and mental health was… before the COVID-19 pandemic”. The responses were graded on a three-point scale (good, fair, and poor). Participants who indicated the number of deaths on the Participant Information Sheet were eliminated from the sample due to known death cases, which may have influenced psychological distress. Based on claimed pre-pandemic mental health, and not living alone, women with at least one child included in the sample. Valid responses were found on all of the variables in a sample of 1349 women (Mage = 34.70, SD = 9.46) with overall response rate of 73%. Table 2 shows the demographics of the sample.

Table 2.

Survey respondents demographic characteristics (N = 1349)

| Measure | Item | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 25–30 | 155 | 11.49 |

| 31–34 | 307 | 22.76 | |

| 35–40 | 324 | 24.01 | |

| 41–44 | 275 | 20.38 | |

| 45–50 | 197 | 14.60 | |

| 51– | 91 | 6.76 | |

| Education | Lower than high school | 66 | 4.89 |

| High school only | 213 | 15.79 | |

| Professional education | 372 | 27.58 | |

| Undergraduate degree | 676 | 50.11 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 22 | 1.63 | |

| Employment status | Employed | 581 | 43.07 |

| Unemployed and not looking | 492 | 36.47 | |

| Unemployed and looking | 276 | 20.46 | |

| Marital status | Married/living with a partner | 631 | 87.88 |

| Widowed/divorce/separated | 87 | 12.12 | |

| Self-reported mental health status before pandemic | Very healthy | 351 | 26.02 |

| Healthy enough | 724 | 53.67 | |

| Fairly healthy | 274 | 20.31 |

Measurement of variables

Dependent variable

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) was employed as a dependent variable in this study as a mental health screening tool. The K6's six items use a 5-point scale (ranging from 0 = never to 4 = always) to assess how often the respondent felt (a) nervous (e.g., ‘‘How often have you felt nervous?’’), (b) hopeless, (c) restless or fidgety, (d) so depressed that nothing could cheer you up, (e) that everything was an effort, and (f) worthless over the previous two weeks (Kessler et al., 2002).

Social isolation

Five previously approved questions were used to assess subjective social isolation: (a) subjective closeness between family members, (d) subjective closeness between friends, (c) a lack of companionship, (d) feeling left out, and (e) feeling alienated from others (Taylor et al., 2016).

Perceived behavioral control over social distancing

PBC can be measured using global questions about how easy or difficult it is to act, or belief-based measures that combine personal beliefs about specific inhibitors to perform the action with perceptions of the inhibitors' power (Rossi & Armstrong, 1999; Wang et al., 2015). The use of belief-based behavioral control measures was evaluated in the current study, as well as the relative ease of getting distance from others in shared open spaces. ‘‘Due to the number of residents, I am not confident that I can keep my distance from others’’ (inverse-scored); ‘‘I feel personal control over social distancing if I wanted to use shared open spaces’’; ‘‘I feel that maintaining social distance in shared open spaces is beyond my control’’ (inverse-scored); ‘‘Due to the open space design, it is difficult to avoid facing others in shared open spaces’’ (inverse-scored); ‘‘The size of the open space makes it easier to keep your distance from others’’; and ‘‘It is mostly up to me whether or not to keep distance to others in shared spaces’’.

Statistical analyses

We conducted an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to distinguish if there were significant differences in people’s perceived behavioral control over social distancing according housing layout (linear, courtyard, and freestanding blocks). To assess the research model and hypotheses, this study used the partial least square (PLS) technique for data analysis with Smart-PLS 3.0 software. A variance-based SEM can be used to estimate complex cause-effect models using latent variables. Adopting the PLS approach allows latent components to be modeled as reflective or formative constructs and has fewer sample size restrictions (Chin, 1998). The researchers employed a hierarchical component model using a two-stage method that included a measurement model and a structural model.

Results

Table 2 provides a summary of the study participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Descriptive statistics

Differences in perceived behavioral control over social distancing

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine if perceived behavioral control over social distancing during the COVID period was different for residents in various housing layouts. The results for the ANOVA analysis indicate a statistically significant difference between groups [F (2,1346) = 184.640, p = 0.000], supporting H1. Participants in courtyard blocks layout reported higher levels of PBC (M = 2.613, SD = 0.025) than those in linear blocks (M = 2.302, SD = 0.026) and freestanding blocks (M = 1.926, SD = 0.024).

Assessment of measurement model

The conceptual model was evaluated and causal linkages were investigated using SEM. The usage of PLS was deemed reasonable and most appropriate according to the research model. In the first stage, the indicator reliability, construct reliability, convergent validity, and assessment of the measurement models were investigated, while the second stage established testing of the structural linkages proposed in the conceptual model.

Table 3 summarizes the measurement model’s findings. Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability (CR) were both more than 0.70, indicating strong internal consistency and reliability (Henseler et al., 2009). The model's capacity to explain the variance of the indicator is known as convergent validity. A criterion of 0.5 for average variance extracted (AVE) is suggested for providing convergent validity. The AVEs were significantly over the needed minimum, showing an acceptable level of convergent validity.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics, alphas, and discriminant validity

| Alpha | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBC | 0.801 | 0.857 | 0.509 |

| PD | 0.838 | 0.881 | 0.555 |

| SI | 0.798 | 0.862 | 0.561 |

M Mean, SD Standard deviation, Alpha Cronbach’s alpha, CR Composite reliability, AVE Average variance extracted, PBC Perceived behavioral control, PD Psychological distress, SI Social isolation

Assessment of structural model

Before presenting structural model, it is useful to briefly note the value of moderation analysis in general. Moderators variables (also known as interaction effects or effect modifiers) address ‘‘it depends’’ type questions and provide insight regarding the circumstances under which two variables are associated or the conditions that affect the nature of the relation. Other language associated with moderators includes ‘‘under what circumstances, for whom or when (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Understanding when the environment influences behavioral outcomes is the prerequisite of making informed policy and intervention decisions.

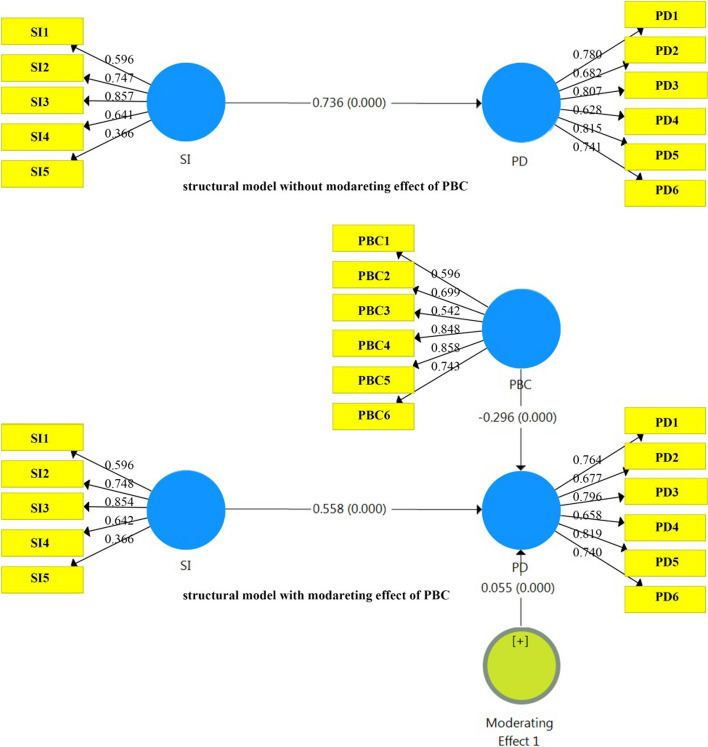

First, baseline model without moderating effect was analyzed. To determine the model's t-values, 5000 bootstrapping samples were utilized, each with the same amount of observations as the original sample to create standard errors and t-values (Hair et al., 2011). With a P-value of less than 0.1, values of t equal to or greater than 1.96 suggest a significant level of the proposed link (Chin, 1998; Hair et al., 2017). Without considering the moderating role of PBC, social isolation was significantly and positively linked with psychological distress (β = 0.736, p < 0.001), supporting H2. Participants who felt isolated from others were more likely to experience psychological distress.

Second, adding the moderating role of PBC in the model (Fig. 1), the significance and magnitude of the path coefficients were used to estimate path links between the latent variables in the model. The results showed that the path from social isolation to psychological distress remained significant (Table 4). A comparison of the beta value in the model excluding perceived behavioral distancing showed that the beta value decreased from 0.736 to 0.558. These findings provided empirical evidence that perceived behavioral control over social distancing moderate the relationship between social isolation and psychological distress, supporting H3. This moderation effect means that the effect of independent variable (SI) on dependent variable (PD) depends upon the levels of a moderator (PBC). In other words, the nature of the relationship between social cohesion and psychological distress differs depending on the values of perceived behavioral control over social distancing.

Fig. 1.

Structural equation modeling- moderating effect of PBC on the relation between SI and PD

Table 4.

Moderating effect of perceived behavioral control over social distancing

| Path c | Mean | SD | T Value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderating effect SI > PD | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.015 | 3.652 | 0.000 |

| PBC → PD | − 0.296 | − 0.296 | 0.022 | 13.142 | 0.000 |

| SI → PD | 0.558 | 0.558 | 0.021 | 26.074 | 0.000 |

The multi-group comparison is based on a non-parametric approach (MGA)

PBC Perceived behavioral control, PD Psychological distress, SI Social isolation

*, **, *** indicate significance at the 5%, 1% and 0.1% levels

Hair et al. (2017) suggested that the structural model could be evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R-square). R2 values of 0.67, 0.33, and 0.19, according to Chin (1998), must be considered for substantial, moderate, and weak estimations, respectively. The R2 value in this study were above the acceptable level, with an acceptable (0.604) value, indicating that the corresponding construct has a good predictive potential.

Discussion

Subjective well-being has regularly been proved to be an independent predictor of health (Corley et al., 2021). In addition to its terrible physical implications, the COVID-19 pandemic has posed a mental health issue, prompting governments worldwide to impose lockdowns to prevent disease spread. When people's access to work, education, and public spaces is limited, their homes must play a special role in their daily lives and mental health (Meagher & Cheadle, 2020).

In the contemporary setting of COVID-19, little is known about the critical role of housing layout in correlations between perceptual characteristics and the repercussions of social isolation (Melo & Soares, 2020). The current study adds to the body of knowledge by addressing the following issue: During a lockdown, is it possible that having a sense of behavioral control over social distancing from others in public and shared areas could reduce the impact of social isolation on psychological distress?

Results show that courtyard blocks layout performed better in the pandemic situation that can promote relatively better social distancing. This may be because neighborhood context shapes mental health by facilitating emotional support via social networks (Elliott et al., 2014). Centralized communal spaces could increase social support among residents and this support lead individuals think and act more positively towards others, less perceiving others’ presence as a threat. Although, freestanding blocks of about four stories are able to allow residents a more immediate relationship with neighboring spaces (Biddulph, 2007), where management processes are poor such blocks can result in vague and poorly used open spaces between the blocks.

Our data indicated that social isolation is linked to psychological distress, confirming Durkheim’s theory that lack of social integration has negative mental health repercussions (Berkman et al., 2000). Many areas of people’s lives, including levels of physical activity, psychological and physical wellbeing, have been negatively impacted by key policies such as social distancing and self-isolation (Cellini et al., 2020; Corley et al., 2021). This finding demonstrated that, while social distancing techniques may assist safeguard public health, they may have unanticipated negative repercussions for mental health, consistent with evidence identifying loneliness as a risk factor for mental health (e.g., Liu et al., 2020). Cutting off from social networks can make people feel vulnerable and pessimistic about their situation, resulting in negative mood states and discomfort, amplified during a pandemic. Because residents are likely to have already experienced a loss of interpersonal bonds due to the epidemic, the additional social isolation brought on by the mandatory physical separation can exacerbate the psychological toll (Hyun-soo & Jung, 2021).

Recent urban studies have found that psychological well-being has a significant relationship with perceptions of open and green spaces, which may differ from objective measures. Considering the quantity and objectively quantifying green/open space without taking into account how people perceive the space may not provide the full picture of a situation. As a result, we have concentrated on how people feel about social distancing in shared open spaces. The role of perceived behavioral control in the link between social isolation and psychological distress provides empirical support for the influence of perceived behavioral control on the usage of open places during the pandemic. Spending time in public open areas may encourage people to interact with their neighbors, fostering a sense of community and social relationships. Increased social cohesion has been identified as a fundamental driver of psychological wellbeing and as an underlying mechanism in the link between open space and health (Corley et al., 2021; De Vries et al., 2013). Furthermore, neighborhood identification is an essential factor relating to the local environment and has a direct impact on mental health (Fong et al., 2019; Wells & Harris, 2007). The advantages of having an optimistic attitude in life were amplified by community togetherness. This conclusion emphasizes that a home’s appraisal will vary depending on the amount to which particular sorts of psychological needs are addressed or not. Individuals’ ability to directly organize the home environment to allow desirable behaviors can also be an important aspect of maintaining excellent mental health (Meagher & Cheadle, 2020). Effective self-regulation frequently entails engaging in future self-control by establishing an atmosphere that encourages desired behaviors while discouraging undesired ones.

Conclusion

For epidemic diseases, measures that are taken to prevent and control infections include treatment, vaccination, quarantine, and isolation. At the same time, the general connection between social isolation and poor mental health is well-established. In high-density residential environments with apartment dwelling units, it is necessary to avoid crowded open spaces and maintain social distancing in public area so that people can spend little time on limited leisure activities without risk perception. Therefore, the need to arrange and re-arrange open spaces with the appropriate level of safety measures is essential.

In the context of COVID-19 pandemic, little is known about the role of housing layout on social distancing. Our goal was thus to shed additional light on this issue by adopting the construct of perceived behavioral control that deals with situations in which people may lack complete volitional control over the behavior of interest. The findings provide insight concerning the moderating mechanism and the interaction effect of social isolation and perceived behavioral control over social distancing on psychological distress. It has been suggested that when perceived behavioral control over social distancing due to housing layout is low, there is a more robust association between social isolation and psychological distress. This finding informs policymakers to focus on housing layout attributes and on users’ perceptions, attitudes, and subjective norms over social distancing.

Limitation and future studies

To promote mental health through the built environment, residential spaces should be planned and managed to accommodate differing preferences and perceptions, particularly among people from various socioeconomic backgrounds. Only individuals with a particular degree of technology skill and internet connection were eligible to participate; the study sample may be biased toward people from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Because the relationship between social isolation and adverse outcomes varies by gender, generalizing the findings should be done with caution. Given that this case study was limited to a small number of socio-demographic and health-related characteristics, as well as gated communities in a specific context, future research should look at the outcomes in other cities and socio-cultural settings. Further research might include operationalization of additional, more precise mediating and moderating mechanisms (such as perceived interior crowding) to provide a more detailed understanding of how housing characteristics along with other intervening mechanisms operate to link social isolation and mental health. Finally, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to make definitive conclusions about causal ordering among variables. Hence, future research would benefit greatly from using longitudinal data to better address the issue of temporal ordering in relation to the mentioned associations.

Acknowledgements

I express my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and editors for their insightful and critical comments, which have improved the quality of the manuscript. I am also grateful to Mrs. Elieh Qara Bashlou for photos of housing complexes.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This research is not based on laboratory data and the satisfaction of all participants has been obtained.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmadpoor N, Shahab S. Realising the value of greenspace: A planners’ perspective on the COVID-19 pandemic. Town Planning Review. 2020;92(1):49–56. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2020.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:665–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allam Z, Jones DS. Pandemic stricken cities on lockdown. Where are our planning and design professionals [now, then and into the future]? Land Use Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman I. The environment and social behavior. Brooks-Cole; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40(4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical consideration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter GL, Tooth LR, Mishra GD. Psychological distress in young Australian women by area of residence: Findings from the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;295(July):390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddulph M. Introduction to residential layout. Architectural Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau J, Marchand A, Demers A. Psychological distress inequality between employed men and women: A gendered exposure model. SSM-Population Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2003;46(3):S39–S52. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin WW. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In: Marcoulides GA, editor. Methodology for business and management. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publisher; 1998. pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary A, Roiko A, Burton NW, Fielding KS, Murray Z, Turrell G. Changes in perceptions of urban green space are related to changes in psychological well-being: Cross-sectional and longitudinal study of mid-aged urban residents. Health & Place. 2019;59:102201. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley J, Okely JA, Taylor AM, Page D, Welstead M, Skarabela B, Redmond P, Cox SR, Russ TC. Home garden use during COVID-19: Associations with physical and mental wellbeing in older adults. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Hessling RM, Brown PA, Murry V. Direct and moderating effects of community context on the psychological well-being of African American women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(6):1088–1101. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries S, Van Dillen SM, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P. Streetscape greenery and health: Stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;94:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de León-Martínez LD, Palacios-Ramírez A, Rodriguez-Aguilar M, Flores-Ramírez R. Critical review of social, environmental and health risk factors in the Mexican indigenous population and their capacity to respond to the COVID-19. Science of the Total Environment. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einifar A, Ghazizadeh SN. The typology of Tehran residential building based on open space layout. Armanshahr. 2011;3(5):35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J, Gale CR, Parsons S, Kuh D, The HALCyon Study Team Neighbourhood cohesion and mental wellbeing among older adults: A mixed methods approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;107:44–51. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2014.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong P, Cruwys T, Haslam C, Haslam SA. Neighbourhood identification and mental health: How social identification moderates the relationship between socioeconomic disadvantage and health. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2019;61:101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gascon M, Triguero-Mas M, Martínez D, Dadvand P, Forns J, Plasencia A, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12:4354–4379. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120404354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorenko JA, Moran C, Flynn M, Dobson K, Konnert C. Social isolation and psychological distress among older adults related to covid-19: A narrative review of remotely-delivered interventions and recommendations. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2021;40(1):3–13. doi: 10.1177/0733464820958550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadavi S. Direct and indirect effects of the physical aspects of the environment on mental well-being. Environment and Behavior. 2017;49(10):1071–1104. doi: 10.1177/0013916516679876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice. 2011;19(2):139–151. doi: 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JFJ, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) 2. Sage Publications Inc.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hakovirta M, Denuwara N. How COVID-19 redefines the concept of sustainability. Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3727. doi: 10.3390/su12093727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatun O, Kurtça TT. Self-compassion, resilience, fear of covid-19, psychological distress, and psychological well-being among Turkish adults. Current Psychology. 2022;24:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02824-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2015;43(1):115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sinkovics, R.R., (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 277–319.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Steptoe A. Social isolation: An underappreciated determinant of physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2022;43:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Roberts JD, Azevedo GP, Milner D. The role of built and social environmental factors in Covid-19 transmission: A look at America’s capital city. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2021;65:102580. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun-soo Kim H, Jung JH. Social isolation and psychological distress during the covid-19 pandemic: A cross-national analysis. The Gerontologist. 2021;61(1):103–113. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jens K, Gregg JS. How design shapes space choice behaviors in public urban and shared indoor spaces—A review. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2021;65:102592. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand S-LT, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalence’s and trends in nonspecific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khavarian-Garmsira AR, Sharifi A, Moradpoure N. Are high-density districts more vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic? Sustainable Cities and Society. 2021;70:102911. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.102911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Miller PA. The impact of green infrastructure on human health and well-being: The example of the Huckleberry Trail and the Heritage Community Park and Natural Area in Blacksburg, Virginia. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2019;48:101562. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2019.101562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Kang SW. Perceived crowding and risk perception according to leisure activity type during COVID-19 using spatial proximity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(2):457. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. Emerging study on the transmission of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) from urban perspective: Evidence from China. Cities. 2020;103:102759. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meagher BR, Cheadle AD. Distant from others, but close to home: The relationship between home attachment and mental health during COVID-19. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megahed NA, Ghoneim EM. Antivirus-built environment: Lessons learned from Covid-19 pandemic. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2020;61:102350. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo MCA, Soares D. Impact of social distancing on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: An urgent discussion. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020;66(6):625–626. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavinia SF. How residential density relates to social interactions? Similarities and differences of moderated mediation models in gated and non-gated communities. Land Use Policy. 2022;120:106303. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nila K, Holt DV, Ditzen B, Aguilar-Raab C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) enhances distress tolerance and resilience through changes in mindfulness. Mental Health & Prevention. 2016;4:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mhp.2016.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewska-Guizzo A, Fogel A, Escoffier N, Ho R. Effects of COVID-19-related stay-at-home order on neuropsychophysiologiacal response to urban spaces: Beneficial role of exposure to nature? Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewska-Guizzo A, Sia A, Fogel A, Ho R. Can exposure to certain urban green spaces trigger frontal alpha asymmetry in the brain? Preliminary findings from a passive task EEG study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17:394. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI, Landi G, Boccolini G, Furlani A, Grandi S, Tossani E. The moderating roles of psychological flexibility and inflexibility on the mental health impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Italy. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020;17:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasion R, Paiva TO, Fernandes C, Barbosa F. The AGE effect on protective behaviors during the COVID-19 outbreak: Sociodemographic, perceptions and psychological accounts. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:561785. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.561785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payami Azad S, Morinaga R, Kobayashi H. Effect of housing layout and open space morphology on residential environments–applying new density indices for evaluation of residential areas case study: Tehran, Iran. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering. 2018;17(1):79–86. doi: 10.3130/jaabe.17.79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes RE, Brown SG, McIntyre CA. Integrating the perceived neighborhood environment and the theory of planned behavior when predicting walking in a Canadian adult sample. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2006;21(2):110–118. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AN, Armstrong JB. Theory of reasoned action vs. theory of planned behavior: Testing the suitability and sufficiency of a popular behavior model using hunting intentions. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 1999;4:40–56. doi: 10.1080/10871209909359156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Cohen D. Proximity to urban parks and mental health. Journal of Mental Health Policy Economics. 2014;17(1):19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahvonen O, Airaksinen M. Low-density housing in sustainable urban planning—Scaling down to private gardens by using the green infrastructure concept. Land Use Policy. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HO, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, Chatters L. Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health. 2016;30(2):229–246. doi: 10.1177/0898264316673511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Hanratty B. Loneliness, social isolation and social relationships: What are we measuring? A novel framework for classifying and comparing tools. British Medical Journal Open. 2016;6:e010799. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viezzer J, Biondi D. The influence of urban, socio-economic, and eco-environmental aspects on COVID-19 cases, deaths and mortality: A multi-city case in the Atlantic Forest. Brazil. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2021;69:102859. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.102859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan C, Shen GQ. Encouraging the use of urban green space: The mediating role of attitude, perceived usefulness and perceived behavioural control. Habitat International. 2015;50:130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Brown G, Liu Y, Mateo-Babiano I. A comparison of perceived and geographic access to predict urban park use. Cities. 2015;42:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2014.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wells NM, Harris JD. Housing quality, psychological distress, and the mediating role of social withdrawal: A longitudinal study of low-income women. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2007;27(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- York Cornwell E, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandifar A, Badrfam R. Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;51:101990. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zondag B, Pieters M. Influence of accessibility on residential location choice. Transportation Research Record. 2005;1902:63–70. doi: 10.3141/1902-08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.