Abstract

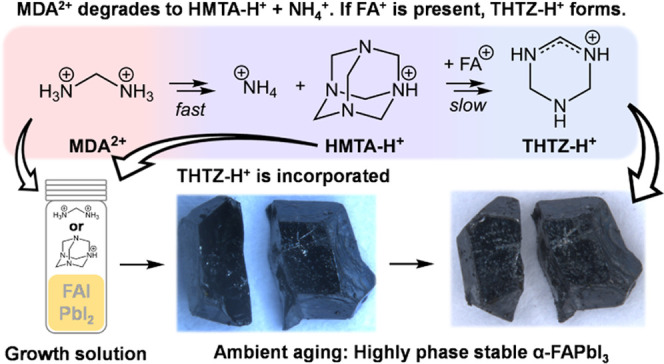

Formamidinium lead triiodide (FAPbI3) is the leading candidate for single-junction metal–halide perovskite photovoltaics, despite the metastability of this phase. To enhance its ambient-phase stability and produce world-record photovoltaic efficiencies, methylenediammonium dichloride (MDACl2) has been used as an additive in FAPbI3. MDA2+ has been reported as incorporated into the perovskite lattice alongside Cl–. However, the precise function and role of MDA2+ remain uncertain. Here, we grow FAPbI3 single crystals from a solution containing MDACl2 (FAPbI3-M). We demonstrate that FAPbI3-M crystals are stable against transformation to the photoinactive δ-phase for more than one year under ambient conditions. Critically, we reveal that MDA2+ is not the direct cause of the enhanced material stability. Instead, MDA2+ degrades rapidly to produce ammonium and methaniminium, which subsequently oligomerizes to yield hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA). FAPbI3 crystals grown from a solution containing HMTA (FAPbI3-H) replicate the enhanced α-phase stability of FAPbI3-M. However, we further determine that HMTA is unstable in the perovskite precursor solution, where reaction with FA+ is possible, leading instead to the formation of tetrahydrotriazinium (THTZ-H+). By a combination of liquid- and solid-state NMR techniques, we show that THTZ-H+ is selectively incorporated into the bulk of both FAPbI3-M and FAPbI3-H at ∼0.5 mol % and infer that this addition is responsible for the improved α-phase stability.

Introduction

Hybrid organic–inorganic metal–halide perovskites are recognized as one of the most promising emerging semiconducting materials for optoelectronic applications due to their excellent properties, including tunable band gaps,1 high absorption coefficients,2 and long charge-carrier diffusion lengths.3 Among the ABX3 lead–halide perovskites reported to date, FAPbI3 (FA+ is formamidinium, HC(NH2)2+)4 has the narrowest achievable band gap, allowing for the highest theoretical photovoltaic power conversion efficiency (PCE) in a single-junction architecture.5 For this reason, the majority of recent world-record PCE perovskite photovoltaics have employed FAPbI3-based materials as their photoabsorbing layer.6−9 However, under ambient conditions, the cubic α-phase of FAPbI3 is thermodynamically unstable with respect to transformation to a photoinactive hexagonal δ-phase polytype. Despite this, the phase transition is kinetically inhibited under ambient conditions permitting metastable α-FAPbI3 to persist for hours, days, and even months, depending strongly on processing conditions and the atmospheric conditions in which the processed material is stored.10,11 The phase stability of FAPbI3 thin films and single crystals is necessary for their practical use. Significant efforts are directed at finding approaches to suppress the α-to-δ phase transition. In particular, smaller A-site cations have been used to stabilize the perovskite lattice by alloying with FA+. Most frequently used are MA+ (but which has been shown to introduce an unfavorable thermal instability12,13) and the alkali-metal Cs+,1415 often in conjunction with I–, Br–, and Cl– X-site alloying. Although promising, such approaches can introduce undesirable properties. Band gap increases induced by structural changes due to the inclusion of smaller cations16 are undesirable for single-junction photovoltaics. Furthermore, compositional inhomogeneities in the mixed-ion perovskites introduced during growth can render materials susceptible to ion segregation17,18 and non-radiative recombination losses19 under operation. It is therefore highly valuable to develop strategies to improve the stability of FAPbI3 without diminishing its valuable properties.

In 2019, Min et al.20 reported highly efficient α-FAPbI3 solar cells based on polycrystalline thin films by incorporating a small amount of methylenediammonium dichloride (MDACl2, 3.8 mol %) into the precursor solution while maintaining the inherent band gap of FAPbI3. The authors attribute the high-certified PCE of 23.7% to the addition of MDACl2 and report that MDA2+ leads to structural stabilization of α-FAPbI3 via partial replacement of FA+ with MDA2+ alongside Cl– incorporation at interstitial sites. Subsequently, Kim et al.21 propose that concurrent substitution of 3 mol % of Cs+ and MDA2+ on FA+ sites lowers the lattice strain and trap density in perovskite solar cells. In more recent works—again from Seok and co-workers—MDA2+ was twice used alongside FAPbI3 to achieve the highest yet-reported certified efficiency for perovskite solar cells, 25.5%9 and subsequently 25.7%.8,22

In order to isolate the role of MDACl2, we here study the effect of its addition to the precursor solution during the growth of FAPbI3 single crystals (denoted FAPbI3-M). We find that the highly acidic MDA2+ cation is unstable in solution, degrading rapidly into ammonium and hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA). However, this degradation is further complicated by the presence of FA+ in the precursor solution, a reaction which can interrupt the degradation pathway and instead lead to the formation of tetrahydro-1,3,5-triazinium (THTZ-H+). We find that of all the degradation products formed, it is THTZ-H+ that is present in FAPbI3-M crystals. We show that FAPbI3-M crystals grown possess vastly improved α-phase stability (>1 year in the air) and significantly reduced defect density.

Results and Discussion

Single-Crystal Growth and Optoelectronic Performance

We grow the single crystals via the inverse temperature crystallization method.23,24 The control FAPbI3 single crystals are prepared by dissolving equimolar FAI and PbI2 in γ-butyrolactone (GBL). Crystal growth is directed by the addition of an appropriate seed crystal to this precursor solution. Heating to 95 °C leads to growth of the seed into an α-FAPbI3 single crystal between 2 and 4 mm in length. For the FAPbI3-M single crystals, we add 3.8 mol % (with respect to the Pb content) of MDACl2 to the FAPbI3 perovskite precursor solution. We note that in contrast to Min et al.,20 we do not add MACl to any of our precursor solutions, as we aim to isolate and investigate the effect of MDACl2 on FAPbI3-phase stability. Further details on crystal growth are discussed in Supporting Note 1. We heat the single crystals in a vacuum oven at 180 °C for 30 min to remove residual solvent on the crystal surface. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) confirms the three-dimensional (3D) perovskite phase in each case, with crystal structures solved in the Pm3̅m cubic space group, as previously reported.25 Crystal data and structure refinement statistics are shown in Table S1. We discuss our SCXRD measurements in detail in Supporting Note 2, including our observation of a pronounced difference in the degree of twinning detected in FAPbI3 crystals grown in the presence of different additives.

We first investigate the impact of MDACl2 on the electronic properties of the FAPbI3 single

crystals. To investigate the charge transport through the single crystals,

we deposit gold electrodes on the crystals and perform pulsed-voltage

space-charge-limited-current (PV-SCLC) measurements in which the dark

current–voltage (J–V) characteristics are measured under vacuum, shown in Figure 1a.26 The pulsed J–V traces of

both samples show an Ohmic region at low voltages, where the slope,  , equals 1. From this region, we estimate

a dark DC conductivity of 8.5 × 10–6 and 5.3

× 10–6 S m–1 for FAPbI3 and FAPbI3-M crystals, respectively. We have previously

shown that if the density of traps is larger than the density of static

ionic space charge, the J–V curve deviates from being linear into a regime where m is larger than 2.26−28 From the voltage point at which this occurs, (Vons), we can calculate a lower bound trap density

(nt) via:

, equals 1. From this region, we estimate

a dark DC conductivity of 8.5 × 10–6 and 5.3

× 10–6 S m–1 for FAPbI3 and FAPbI3-M crystals, respectively. We have previously

shown that if the density of traps is larger than the density of static

ionic space charge, the J–V curve deviates from being linear into a regime where m is larger than 2.26−28 From the voltage point at which this occurs, (Vons), we can calculate a lower bound trap density

(nt) via:  , where ε0 is the vacuum

permittivity, L the crystal thickness, e the electron charge, and εr is the low-frequency

dielectric constant of the material, reported as 49.4 for FAPbI3.29 We assume the same value for

εr for FAPbI3-M. We find that adding MDACl2 to the precursor solution significantly reduces the trap

density from a lower bound of 1.1 × 1012 cm–3 for FAPbI3 to 4.3 × 1010 cm–3 for FAPbI3-M.

, where ε0 is the vacuum

permittivity, L the crystal thickness, e the electron charge, and εr is the low-frequency

dielectric constant of the material, reported as 49.4 for FAPbI3.29 We assume the same value for

εr for FAPbI3-M. We find that adding MDACl2 to the precursor solution significantly reduces the trap

density from a lower bound of 1.1 × 1012 cm–3 for FAPbI3 to 4.3 × 1010 cm–3 for FAPbI3-M.

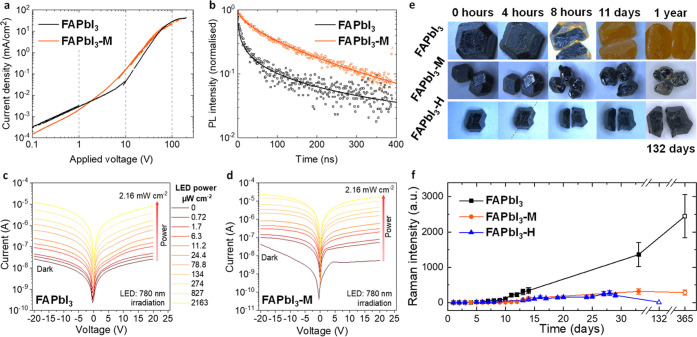

Figure 1.

Single-crystal optoelectronics and stability. (a) PV-SCLC measurements for FAPbI3 and FAPbI3-M single crystals; (b) time-resolved photoluminescence measurements of FAPbI3 and FAPbI3-M. Current density–voltage curves in a N2 environment of (c) FAPbI3 and (d) FAPbI3-M single-crystal photodetectors with Ag electrodes. (e) Optical microscope images of grown FAPbI3, FAPbI3-M, FAPbI3-H crystals. The crystals are cleaved after 4 h. The crystals were kept in glass vials under ambient conditions (dark, relative humidity ∼30 to 80%) throughout the measurement period. (f) Temporal evolution of δ-phase Raman peak intensity for FAPbI3, FAPbI3-M, FAPbI3-H single crystals. The single crystals were kept in the air for the first 33 days. The long-term data at 132 and 365 days (no fill) correspond to vial-stored crystals.

The improvement in optoelectronic quality of these FAPbI3-M single crystals is supported by time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) measurements (depicted in Figure 1b). Fitting the TRPL decay traces reveals a significant increase in a lifetime from 47 ns for the FAPbI3 single crystal to 121 ns for the FAPbI3-M single crystal at a fluence of 18 nJ cm–2. More details on this measurement and the fitting are given in the Supporting Note 3. To assess if FAPbI3-M crystals also improve optoelectronic devices, we fabricate photodetectors from the single crystals. Figure 1c,d shows the current density curve of FAPbI3 and FAPbI3-M single-crystal detectors. We observe a higher photoconductivity for FAPbI3-M photodetectors and an improved ON/OFF ratio (Supporting Figure S7).

Significantly, we also find that FAPbI3-M crystals possess substantially greater α-phase (black) stability in ambient air than neat FAPbI3. By visible light microscopy, we observe the growth of trace regions of a δ-phase (yellow) on the crystal surface of both materials after only a few hours of storage in the air (Figure 1e). For FAPbI3-M, the degradation does not propagate significantly on the surface or into the bulk, as seen when we cleave the crystals after several hours. Notably, FAPbI3-M crystals remain predominantly in their α-phase after one year of storage in ambient air. By contrast, FAPbI3 crystals display complete phase transformation to the photoinactive δ-phase within a few days (Figure 1e and Supporting Figure S8).

To quantitatively track the phase stability of the crystals, we monitor the absolute Raman intensity of the best resolved δ-phase peak (at a Raman shift of 108 cm–1) under ambient conditions. As Figure 1f shows (complete Raman spectra shown in Figure S9), neat FAPbI3 undergoes detectable δ-phase formation after 7 days. This onset occurs at 11 days for FAPbI3-M. In Raman spectra of the same crystals after 1 year of storage in air-filled vials, we detect (2.5 ± 0.5) × 103 and (0.25 ± 0.06) × 103 δ-phase peak counts for FAPbI3 and FAPbI3-M, respectively. Peak intensity is proportional to the fraction of the probed surface layer in the δ-phase. Notably, the thickness of the probed layer for α-phase FAPbI3 is estimated to be ∼100 nm via the absorption coefficient (ca. 105 cm–1 at the Raman laser wavelength of 532 nm).30 Thus, the onset of the δ-phase peak in Figure 1f corresponds to the degradation of only the top surface of the crystals. We obtain complementary degradation data of the bulk crystal by carrying out the same Raman measurement on the exposed interior of freshly cleaved crystals, different from those presented in Figure 1f. Cleaving a FAPbI3-M crystal after 285 days of aging gives a peak intensity ratio of Ibulk/Isurface = 0.10 ± 0.03 for the δ-phase peak. This confirms that the observed δ-phase formation occurs predominantly in a thin surface layer of FAPbI3-M crystals, while the bulk remains largely unaffected. By contrast, the neat FAPbI3 crystal is entirely converted to the δ-phase.

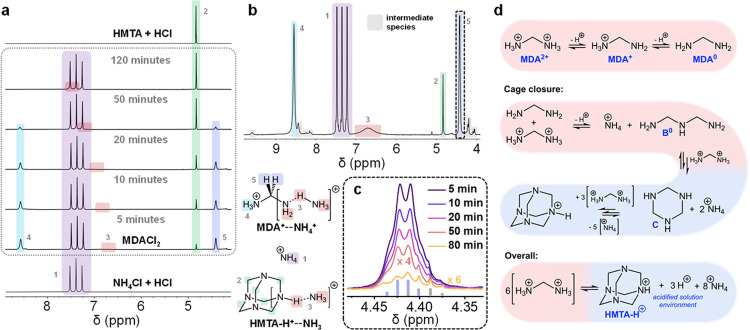

MDA2+ Solution Instability

Having established the substantial advantages of MDACl2 addition for FAPbI3 single-crystal properties, we now investigate the activity of this additive in solution. It has been previously inferred that MDA2+ is incorporated within the cubic ABX3 perovskite lattice on the A-site in solution-processed polycrystalline thin films based on FAPbI3, and thus, A-site cation mixing is thought to be responsible for the enhanced α-phase stability.20,21 However, we find that MDA2+ degrades rapidly in precursor solutions. Figure 2a shows the 1H solution NMR spectra acquired from a solution of MDACl2 dissolved in DMSO-d6 between 5 and 120 min after initial dissolution (expanded spectra shown in Supporting Figure S11). In Figure 2b, we show an expanded view of the earliest of these spectra, emphasizing the presence of a number of signals that appear to correspond to intermediate species that exist only transiently. At the shortest time after dissolution, the 1H NMR spectrum already shows several unexpected species. We attribute the distinctive 1:1:1 triplet at 7.34 ppm to NH4+, with the splitting due to spin–spin coupling of 1H to the quadrupolar (I = 1) 14N nucleus (1J14N–1H = 50.8 Hz). The signal, initially at 7.34 ppm, rapidly shifts and stabilizes at 7.37 ppm, as is typical for ammonium species under varying pH conditions.31 This assignment is confirmed by comparison with the solution 1H NMR spectra of NH4Cl in DMSO-d6 (Supporting Figure S12). 1H–1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY), depicted in Supporting Figure S13, reveals that the two other substantial signals initially present in the 1H solution NMR of MDACl2 solutions are spin–spin coupled and thus correspond to nuclei present in the same species. Figure 2c highlights the coupling of one of these signals (4.42 ppm), which we find is superposed on top of another low-intensity signal, both of which we interpret as quartets. Given C–C bond formation is unlikely under the conditions, the resolution of this spin-coupling along with the chemical shift suggests a CHn environment adjacent to a +NH3 group. In Supporting Note 6, we present the findings from a series of further experiments investigating the evolution of intermediate degradation species and discuss our interpretation. From all these data, we infer that the most likely assignment for the dominant intermediate observed is MDA+ in which the amine group is undergoing rapid chemical exchange with acidic NH4+ in solution (Figure 2b). The accumulation of this species is mechanistically justified. When the charge-dense MDA2+ cation is dissolved in pH neutral, aprotic polar solvents such as dimethylformamide (DMF), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and GBL, it is expected to act as a Brønsted acid, rapidly releasing H+ to become MDA+ and acidifying the solution environment, as shown in Figure 2d. Release of a second acidic H+ is possible, although less favorable in the acidified solution environment. However, this second deprotonation event yields neutral MDA0, a potent nucleophile. The presence of both MDA0 and MDA2+, a strong electrophile, renders both species unstable in solution with respect to the formation of NH4+ and bis(aminomethyl)ammonium (B+). Thus, under these conditions, MDA+ is the most stable form of this species. MDA+ can also act as an electrophile; however, its single charge renders it less reactive than MDA2+. It may also eliminate to produce NH3 and methaniminium, CH2=NH2+. However, elimination reactions are typically slow, and the production of methaniminium—itself a highly reactive electrophile—does not alter the course of the degradation. We propose a complete mechanistic description in Supporting Figure S15.

Figure 2.

Degradation of MDA2+. (a) 1H solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra tracking the evolution of MDACl2 upon dissolution in DMSO-d6. Bottom: spectra acquired from acidified solution of ammonium chloride. Top: spectra acquired from acidified solution of (HMTA). Color scheme correlates detected signals with 1H chemical environments in detected species. (b) Expanded 1H NMR spectrum of 5 min after the initial dissolution of MDACl2 in DMSO-d6. (c) Evolution of 1H NMR quartet signal corresponding to methylene environment in dominant degradation intermediate. (d) Degradation pathway of MDA2+ upon dissolution in a polar solvent. Hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA) and ammonia are represented in their protonated forms in line with our observations and on account of the acidic environment generated in solution as a result of the degradation.

Transient deprotonation of B+ produces B0, another nucleophile, which reacts with further MDA2+ before rapidly cyclizing to form 1,3,5-triazinane (C). Repeated reaction of C with MDA2+ in conjunction with rapid cage-closure, driven entropically by the release of additional NH4+, is expected to lead to the formation of HMTA-H+, as shown in Figure 2d. Experimentally, between 5 and 50 min after the initial dissolution of MDACl2, a singlet signal of increasing intensity is observed in the 1H solution NMR spectra at 4.83 ppm. By 120 min after initial dissolution, the spectrum consists only of this singlet, the 1:1:1 triplet corresponding to ammonium, and a broad singlet at 8.00 ppm. HMTA dissolved in DMSO-d6 at neutral pH shows a singlet at 4.56 ppm (Supporting Figure S16). However, incremental addition of hydrochloric acid to this solution produces a downfield shift of this singlet to 4.83 ppm in line with the reported monoprotic pKaH value for HMTA (4.93),32 confirming the identity of the final product of MDA2+ degradation as HMTA-H+. Integration of the relevant 1H NMR signals confirms the stoichiometric 8:1 ratio of NH4+/HMTA-H+ expected by the proposed degradation route. As observed with MDA+, rapid chemical exchange between the acidic H+ of HMTA-H+ and ammonium leads to a broadened 1H NMR signal at a chemical shift corresponding to the weighted average of the contributing chemical environments (7.45 ppm). We emphasize that despite the bias toward the formation of HMTA-H+ and NH4+, as all reaction steps are mechanistically reversible, it should be expected that the system at dynamic equilibrium will include small quantities of all intermediates. Further, we note that our aim has not been to attempt to stabilize either MDA2+ or MDA+ in solution, which may be achievable, for example, by the addition of excess acid, but that this is certainly an avenue for further investigation.

FAPbI3-MDACl2 Precursor Solution Chemistry

Having identified that HMTA and NH4Cl are the degradation products of MDACl2 in the aprotic organic solvents, we now investigate if either degradation product plays an active role in improving FAPbI3 crystal properties. We first perform the crystal growth as described above but with the separate addition of either HMTA or NH4Cl. Each additive is added in the 8:1 stoichiometry expected when 3.8 mol % MDA2+ degrades entirely to NH4+ (5.07 mol %) and HMTA-H+ (0.63 mol %). FAPbI3 crystals grown with NH4Cl additive alone undergo α-phase degradation at a rate comparable to FAPbI3 single crystals grown without additives. Strikingly, however, FAPbI3 crystals grown in the presence of HMTA (FAPbI3-H) show neither surface degradation nor bulk degradation to the δ-phase (Figure 1e). We quantify the stability of FAPbI3-H using Raman spectroscopy, as we report above for FAPbI3 and FAPbI3-M crystals, and find that, after 132 days of ambient air aging, FAPbI3-H crystals show no evidence (0 counts, background subtracted) of δ-phase formation (Figure 1f).

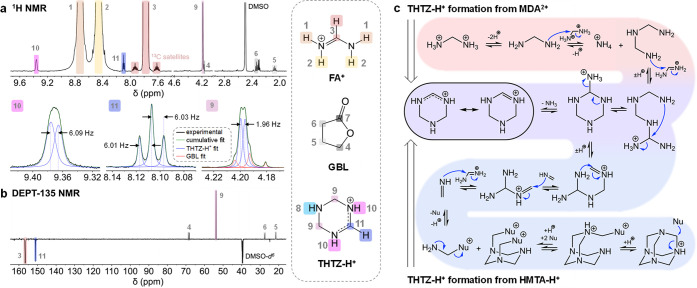

Having established that replacing MDACl2 addition with a corresponding quantity of HMTA mimics the α-phase stability enhancement of FAPbI3-M, we conduct liquid-state 1H and directionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT-135, 1H–13C) NMR spectroscopy (Figure 3a,b, respectively) on solutions of FAPbI3-M crystals dissolved in DMSO-d6. Unexpectedly, we do not detect the presence of HMTA-H+. Instead, in the 1H spectrum, we observe signals at 9.36 (d, 6.09 Hz), 8.10 (t, 6.02 Hz), and 4.19 (d, 1.96 Hz) ppm in 2:1:4 stoichiometry. Analysis of the fine structure of each of these signals suggests spin–spin coupling between nuclei giving rise to the signals at 8.10 and 9.36 ppm, with a J-coupling constant consistent with vicinal 1H–1H coupling trans across a sp2 system (3JH9–H10 ∼ 6 Hz). To confirm this, we carry out 1H–1H COSY (Supporting Figure S17). These data confirm the 3JH9–H10 coupling, while an off-diagonal cross-peak between signals at 9.36 and 4.19 ppm suggests spin–spin coupling and thus atomic proximity between these chemical environments. The DEPT-135 13C spectrum shows a CH/CH3 signal (151.1 ppm) with a chemical shift comparable to the methine of FA+ (156.6 ppm) and a CH2 signal at 53.8 ppm, indicating an electron-depleted sp3 environment. These data are consistent with the presence of tetrahydro-1,3,5-triazinium (THTZ-H+).33 Integration of 1H methine signals in both species indicates that THTZ-H+ is present in solution at ∼0.5 mol % with respect to FA+. From these findings, it is evident that the degradation of MDA2+ is further complicated by the presence of other organic cations in our precursor solutions, in this instance FA+.

Figure 3.

FAPbI3-M single-crystal composition. 1H solution (a) and directionless enhancement by polarization transfer (1H–13C) (DEPT-135) (b) NMR spectra (600 MHz) of FAPbI3-M single crystal dissolved in DMSO-d6. Spectra are referenced to the DMSO signal. Insets below 1H spectra show expansions of signals corresponding to THTZ-H+ with signal fitting and spin–spin coupling constants displayed in Hz. (c) Proposed mechanism for the formation of THTZ-H+ from MDA2+ (top left) or HMTA-H+ (bottom right) via generation of 2 equiv of methanimine and reaction with FA+. Nu corresponds to any available nucleophile in solution, most likely the HMTA additive. Further discussion is presented in Supporting Note 6.

Acquisition of 1H NMR spectra over time upon the addition of 3.8 mol % MDACl2 to a solution of FAI in DMSO-d6 initially shows the formation of only HMTA-H+ and NH4+ (Supporting Figure S18). However, upon aging, a third product gradually evolves, THTZ-H+. From this, we infer that, while HMTA-H+ and NH4+ are the kinetic products of MDACl2 degradation, in the presence of FA+, THTZ-H+ is a slower-forming but thermodynamically favored product. We account mechanistically for the formation of THTZ-H+ from MDA2+ in Figure 3c (highlighted red-purple). MDA0-initiated cage formation (Figure 2d) is interrupted by the addition of FA+. Cyclization with a single FA+ cation leads to THTZ-H+.

That all steps in the reactions of Figure 3c are either substitutions or eliminations and thus mechanistically reversible, which is critical to the activity of MDA2+ in FAPbI3 crystal growth for two reasons. First, reversibility ensures that the whole reaction pathway is in dynamic equilibrium in solution. Thus, although HMTA-H+ formation occurs most rapidly, gradual evolution of a more favorable product by subsequent consumption of HMTA-H+ is possible, as emphasized in Figure 3c (highlighted blue-purple). This explains the gradual formation of THTZ-H+ in solution over time from a solution of MDACl2 and FAI (Supporting Figure S18). Second, the selective removal of any species from such a dynamic system disturbs it from equilibrium, resulting in the production of more of the species removed, in line with Chatelier’s principle.34 Repeated incorporation of THTZ-H+ into the solid state of a growing single crystal depletes its concentration remaining in solution, resulting in the production of further THTZ-H+. By this mechanism, ultimately, all MDA2+ added can be converted to THTZ-H+ via HMTA-H+ and incorporated into a growing single crystal, despite THTZ-H+ only ever being present in solution at very low concentration. As with all mechanistic details presented in this work, however, we emphasize that this scheme should be interpreted as a mechanistic justification only. We have not conducted extensive mechanistic studies and have only identified a relatively small number of the species displayed in the mechanistic schemes. This represents a chemically feasible route between the species we have clearly identified.

Significantly, the analysis above depends on the formation of THTZ-H+ by decomposition of HMTA (via protonation by weakly acidic FA+), as proposed in Figure 3c (highlighted blue). Thus, one test of our proposed mechanism is to confirm this is indeed the case. To do so, we obtain 1H NMR spectra when single crystals grown in the presence of HMTA (FAPbI3-H) or NH4Cl are dissolved in DMSO-d6 (Supporting Figures S20 and S21). In line with the mechanism presented, we find that signals corresponding to THTZ-H+ are observed in the spectra of all crystals grown with either HMTA or MDACl2 present in their precursor solution but not when NH4Cl alone is added. The absence of any signals in these spectra corresponding to ammonium or HMTA confirms that these additives are not included in the materials. We have therefore correlated the enhanced α-phase stability of FAPbI3-M and FAPbI3-H crystals with the presence of THTZ-H+ in solutions of dissolved single crystals.

Solid-State Compositional Analysis of FAPbI3 Single Crystals

When FAPbI3-M or FAPbI3-H single crystals are dissolved, a solution rich in FA+ and with only trace quantities of THTZ-H+ is produced. However, as we have shown, THTZ-H+ formation occurs spontaneously in solutions containing FA+ alongside MDA2+, HMTA, CH2=NH2+, or many intermediates in the decomposition of these. Therefore, the observation of THTZ-H+ in solutions of dissolved crystals does not confirm that this species is present in the crystals in the solid state. Kinetic entrapment of another intermediate species during crystal growth, e.g., CH2=NH2+, might be expected to produce the same solution once dissolved. Nor do our liquid-state experiments provide any evidence of how a new organic species might be incorporated into the perovskite material structurally. Moreover, density functional theory (DFT) calculations assign a steric radius of 2.65 Å for THTZ-H+ (details of our calculations are given in Supporting Note 7). This value is only slightly larger than those for dimethylammonium (DMA+, 2.43 Å), ethylammonium (EA+, 2.42 Å), and guanidinium (GUA+, 2.40 Å). These three cations have all been reported as forming metastable mixed-cation 3D perovskite phases with FA+.35−37 As discussed in Supporting Note 7, these data alone do not allow us to conclude whether THTZ-H+ incorporates the 3D APbI3 perovskite A-site. Therefore, to better investigate the composition of the crystals, we conduct a range of solid-state NMR (ssNMR) measurements.

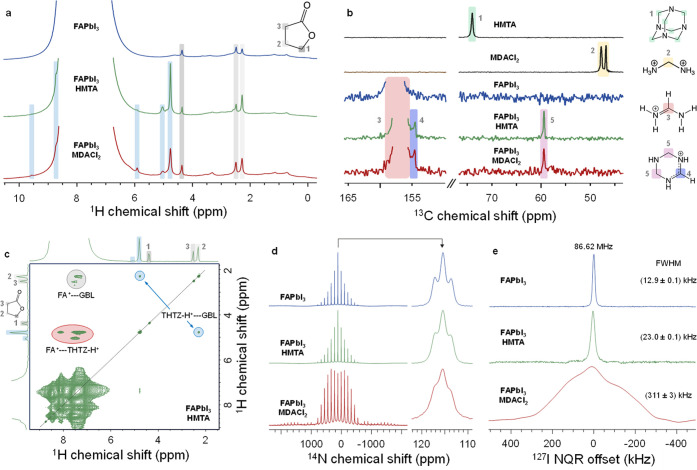

In Figure 4a, we show 1H magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR spectra of FAPbI3, FAPbI3-M, and FAPbI3-H crystals. While the spectra are dominated by intense FA+ signals (6–9 ppm), several additional, well-resolved signals (highlighted in blue) are present in both FAPbI3-M and FAPbI3-H spectra that are not present in neat FAPbI3 crystals. These signals correspond to 1H environments in organic species other than FA+. Although it is not possible to assign these signals based on the 1H spectra alone, we note their close correspondence to those observed in liquid 1H NMR of the same crystals (Figure 3a). Further, we observe clear evidence of GBL in all three crystals, suggesting that small quantities of the processing solvent are entrapped within the crystals, despite prolonged vacuum drying (110 °C, overnight).11,38 By recording quantitative 1H solid-state NMR spectra, and assuming the same number of hydrogen nuclei in FA+ and the additive, we estimate that the new species is present at ∼0.5 mol % in both FAPbI3-M and FAPbI3-H crystals (see Supporting Figure S24 for the integrated regions).

Figure 4.

Solid-state characterization of the FAPbI3 single crystal. (a) 1H MAS (50 kHz) NMR spectra of neat FAPbI3, FAPbI3-H, and FAPbI3-M crystals. Signals highlighted in blue cannot be unambiguously assigned. (b) 13C echo-detected (12 kHz MAS) NMR spectra comparing different FAPbI3 crystals with additives employed in their growth. (c) 1H–1H (50 kHz MAS) spin-diffusion spectrum of FAPbI3-H. (d) 14N (4 kHz MAS) NMR spectra of FAPbI3, FAPbI3-H, and FAPbI3-M crystals (left). The central signal of the spectral envelope is shown in the inset to the right. (e) 127I NQR spectra of FAPbI3, FAPbI3-H, and FAPbI3-M crystals. The color schemes correlate detected signals with chemical environments of relevant nuclei in detected species.

To confirm that the additive detected in the solid state is indeed THTZ-H+, we perform 13C MAS NMR (Figure 4b). As in the case of 1H, we observe new signals (154.5, 59.4 ppm) in FAPbI3-M and FAPbI3-H, which are identical in both materials, but are absent in reference FAPbI3. This result corroborates that the same species is present in FAPbI3-M and FAPbI3-H despite their differing growth environments. The new signals do not correspond to MDACl2 (46.8, 47.7 ppm), HMTA (74.0 ppm), or δ-FAPbI3 (157.3 ppm, Supporting Figure S25). Instead, they closely match those expected for THTZ-H+ as observed via DEPT-135 in solution (151.1, 53.8 ppm) (Figure 3b).

Having detected the presence of THTZ-H+ in the single crystals, we next seek to elucidate its mode of incorporation within the perovskite material. This question is important since THTZ-H+ may be too large to replace FA+ on the A-site, and therefore, how it might interact with the ABX3 material is unclear. We first perform a 1H–1H spin-diffusion (SD) experiment, which relies on the exchange of magnetization between dipolar-coupled protons, which necessarily are in atomic-level contact on the order of tens of Å.39 SD therefore indicates whether the different local 1H environments are present within the same phase, which is the prerequisite for their being dipolar coupled.39Figure 4c shows the 1H–1H SD spectrum of FAPbI3-H. We observe intense cross-peaks between FA+ and THTZ-H+, as well as between GBL and both cations. Thus, we infer that a mixed phase containing THTZ-H+ and FA+ exists in FAPbI3-H and FAPbI3-M rather than an isolated THTZ-H+ secondary phase. Further discussion of the SD experiments regarding structural models of THTZ-H+ incorporation is given in Supporting Note 8.

We next use 14N MAS NMR to establish if the stabilization protocol leads to any detectable change to the local structure of the FA+ cations. It has previously been shown that 14N MAS NMR can be employed as a sensitive technique to probe perovskite lattice distortions from the perspective of A-site cation dynamics.37,40,4114N is a quadrupolar (I = 1) nucleus, and its NMR lineshape is determined by the symmetry of the local environment. In cubic α-FAPbI3, FA+ rapidly reorients on a ps timescale, giving a near-isotropic electric field around the 14N nuclei. The interaction between the small residual electric field gradient (EFG) at the 14N nucleus and the electric quadrupole moment (eQ) of the 14N nuclear spin leads to a relatively narrow FA+ signal linewidth and a narrow envelope of spinning sidebands.42 Incorporation of additive ions in the ABX3 lattice or distortions in the cuboctahedral haloplumbate structure de-symmetrize the A-site, leading to increased anisotropy in FA+ dynamics, an increased EFG at the FA+ 14N nuclei and a broadening of the spectral envelope.37,40,4114N MAS NMR reveals a pronounced broadening of the spectral envelope of FAPbI3-M, which is not observed in the spectra of either FAPbI3-H or neat FAPbI3 (Figure 4d). This implies the incorporation of a new species into FAPbI3-M crystals that is not present under the growth conditions of FAPbI3-H or neat FAPbI3. Considering the consistency between the 13C and 1H ssNMR spectra and the comparable quantities of THTZ-H+ detected in FAPbI3-M and FAPbI3-H crystals, we attribute this broadening to the presence of chloride in FAPbI3-M crystals. To confirm and quantify the presence of chloride, we perform electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) on FAPbI3-M and FAPbI3 crystals. These measurements show that chloride makes up ∼0.8 atom % of total halide content inside the bulk of FAPbI3-M (Supporting Note 9).

Incorporation of THTZ-H+ into the α-FAPbI3 phase might be expected to also result in changes in 14N MAS NMR. However, we detect no significant difference between FAPbI3-H and reference FAPbI3, where spectral broadening due to chloride incorporation is absent. The absence in the spectra of signals corresponding to 14N in incorporated THTZ-H+ suggests that these signals are substantially broadened with intensity spread across a large number of spinning sidebands resulting in their not being detectable. This result suggests that the EFGs at the 14N nuclei of THTZ-H+ are relatively large, most likely due to incorporated THTZ-H+ being static, consistent with its strong coordination to the ABX3 structure.

To better isolate the independent effects of THTZ-H+ and chloride incorporation, we conduct 127I nuclear quadrupole resonance (NQR) spectroscopy on the three materials (Figure 4e). NQR measurements are carried out without an external magnetic field and are a direct measure of the strength of the local EFG. Because the electric quadrupole moment of 127I is remarkably large (−71 Q fm–2, compared to the value for 14N: 2 Q fm–2), small structural changes lead to large changes to the NQR frequency. Interrogation of the full-width half-maxima (FWHM) of the NQR transition at 86.62 MHz shows resolvable differences between all three FAPbI3 materials. We attribute the doubling of the FWHM in FAPbI3-H relative to FAPbI3 to the incorporation of THTZ-H+ into the perovskite structure, which leads to the emergence of a distribution of 127I local environments (static disorder) throughout the bulk. This would not be the case if THTZ-H+ were merely adsorbed on the surface of the crystal or kinetically trapped in a pocket of entrapped precursor solution during crystallization (as is the case during agglomeration and formation of crystal inclusions).43 The formation of a solid solution, whereby THTZ-H+ is distributed homogeneously throughout the bulk, is therefore the only scenario that agrees with the experimental 1H–1H spin-diffusion and 127I NQR data (discussed further in Supporting Note 8). As our steric radius calculations (Supporting Note 7) indicate a substantially larger radius for THTZ-H+ (2.65 Å) than even FA+ (2.24 Å), we preclude interstitial THTZ-H+ as the mode of incorporation, although neither our NMR nor NQR measurements are capable of confirming this explicitly. We therefore propose a substitutional solid solution whereby one or more ions in the α-FAPbI3 structure are replaced by THTZ-H+, consistent with THTZ-H+ being static and strongly coordinated within the ABX3 structure, as inferred from our 14N NMR. The same 127I NQR transition (86.62 MHz) in FAPbI3-M crystals is broadened by approximately an order of magnitude more than FAPbI3-H, in line with additional disordering induced by the incorporation of chloride in addition to THTZ-H+. Previous work assessing the impact of bromide substitution in α-FAPbI3 on 127I NQR broadening suggests approximately a 1% halide substitution, consistent with our EPMA results.44

Conclusions

Precisely determining the composition and structure of complex materials is often crucial, yet highly involved. Here, we have demonstrated that growth of α-FAPbI3 single crystals in the presence of MDACl2, a high-performance additive, leads to significantly reduced trap density and improved ambient α-phase stability. However, by systematically studying the solution growth conditions, we find that MDA2+ degrades rapidly in solution and thus cannot be incorporated into the α-FAPbI3 material, in contrast to previous assumptions. Instead, we show that HMTA-H+ and NH4+ are generated in solution as the majority degradation products. From this informed position, we propose and demonstrate an evolved form of this highly phase-stable material, FAPbI3-H. However, utilizing a multidisciplinary suite of characterization techniques, we find that neither FAPbI3-M nor FAPbI3-H crystals show evidence of incorporation of MDA2+, HMTA-H+, NH4+, or any other intermediates in the degradation of MDA2+. Instead, THTZ-H+ is detected in these crystals. We also discover that chloride is present in FAPbI3-M crystals. However, the comparable α-phase stability of our FAPbI3-H material allows us to isolate that it is THTZ-H+, not chloride, that leads to the improved stability. We rationalize the formation of THTZ-H+ mechanistically and perform experiments confirming that this new cation is distributed homogeneously throughout the single crystals. Using a combination of 1H–1H spin-diffusion solid-state NMR and 127I nuclear quadrupole resonance spectroscopy, we determine that the THTZ-H+ cations are incorporated into the perovskite structure in atomic-level contact with FA+ and leading to an appreciable distortion of the cuboctahedral symmetry. Our work will have direct consequences for the future development of high-efficiency and high-stability perovskite photovoltaic devices.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) U.K. through grants (EP/V010840/1, EP/V027131/1, EP/T028513/1, EP/T025077/1, EP/S004947/1, EP/L01551X/1, EP/R029431, EP/T015063/1, EP/R029946/1, EP/P033229/1) and has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 764787 (PH) and no. 861985 (PEROCUBE). Financial support was also gratefully received from the DFG (CH 1672/3-1), King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Office of Sponsored Research (OSR-2018-CARF/CCF-3079, OSR-2019-CRG8-4095), the Basque Government (PIBA_2022_1_0031 and EC_2022_1_0011) and the Spanish Government (PID2021-129084OB-I00, RTI2018-101782-B-I00, and RED2022-134344). B.M.G. and S.Z. thank the Rank Prize Fund for their support. D.J.K. acknowledges the support of the University of Warwick. The UK High-Field Solid-State NMR Facility used in this research was funded by EPSRC and BBSRC (EP/T015063/1), as well as, for the 1 GHz instrument, EP/R029946/1. B.K.S. acknowledges University College, Oxford, for the Oxford-Radcliffe scholarship. M.J.G. is grateful for access to the X-ray facilities at the Materials Characterization Laboratory at the ISIS Facility. S.S. and M.R.F. accessed computational resources via membership of the UK’s HEC Materials Chemistry Consortium. S.C. acknowledges the Polymat Foundation for a postdoctoral research contract. J.L.D. acknowledges the Polymat Foundation and Ikerbasque, Basque Foundation for Science, for an “Ikerbasque Research Associate” contract. E.Y.-H.H. thanks Xaar for PhD scholarship sponsorship. The authors thank Seth Marder and Steve Barlow for useful discussions related to this work.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are provided in the figures, table, and Supplementary Information. The raw NMR, SCXRD, PV-SCLC, and Raman data as well as input files of the DFT calculations and optimized geometries are available on Oxford University Research Archive.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.3c01531.

Experimental section: materials and synthesis, X-ray diffraction, electrical characterization, photodetectors, Raman spectroscopy, NMR spectroscopy, first principles calculations, electron probe microanalysis (PDF)

Author Contributions

# E.A.D., B.M.G., and P.H. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): H.J.S. is a co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer of Oxford PV Ltd., a company industrialising perovskite PV. A patent has been filed by Oxford University related to this work.

Supplementary Material

References

- Saliba M.; Correa-Baena J. P.; Grätzel M.; Hagfeldt A.; Abate A. Perovskite Solar Cells: From the Atomic Level to Film Quality and Device Performance. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 2554–2569. 10.1002/anie.201703226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wolf S.; Holovsky J.; Moon S. J.; Löper P.; Niesen B.; Ledinsky M.; Haug F. J.; Yum J. H.; Ballif C. Organometallic Halide Perovskites: Sharp Optical Absorption Edge and Its Relation to Photovoltaic Performance. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1035–1039. 10.1021/jz500279b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J.; Hörantner M. T.; Sakai N.; Ball J. M.; Mahesh S.; Noel N. K.; Lin Y. H.; Patel J. B.; McMeekin D. P.; Johnston M. B.; Wenger B.; Snaith H. J. Elucidating the Long-Range Charge Carrier Mobility in Metal Halide Perovskite Thin Films. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 169–176. 10.1039/C8EE03395A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eperon G. E.; Stranks S. D.; Menelaou C.; Johnston M. B.; Herz L. M.; Snaith H. J. Formamidinium Lead Trihalide: A Broadly Tunable Perovskite for Efficient Planar Heterojunction Solar Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 982–988. 10.1039/c3ee43822h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shockley W.; Queisser H. Detailed Balance Limit of Efficiency of P-n Junction Solar Cells. J. Appl. Phys. 1961, 32, 510–519. 10.1063/1.1736034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J. J.; Seo G.; Chua M. R.; Park T. G.; Lu Y.; Rotermund F.; Kim Y. K.; Moon C. S.; Jeon N. J.; Correa-Baena J. P.; Bulović V.; Shin S. S.; Bawendi M. G.; Seo J. Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells via Improved Carrier Management. Nature 2021, 590, 587–593. 10.1038/s41586-021-03285-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J.; Kim M.; Seo J.; Lu H.; Ahlawat P.; Mishra A.; Yang Y.; Hope M. A.; Eickemeyer F. T.; Kim M.; Yoon Y. J.; Choi I. W.; Darwich B. P.; Choi S. J.; Jo Y.; Lee J. H.; Walker B.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Emsley L.; Rothlisberger U.; Hagfeldt A.; Kim D. S.; Grätzel M.; Kim J. Y. Pseudo-Halide Anion Engineering for α-FAPbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells. Nature 2021, 592, 381–385. 10.1038/s41586-021-03406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.; Kim J.; Yun H.-S.; Paik M. J.; Noh E.; Mun H. J.; Kim M. G.; Shin T. J.; Seok S. Il.. Controlled Growth of Perovskite Layers with Volatile Alkylammonium Chlorides Nature 2023, 616724. 10.1038/s41586-023-05825-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min H.; Lee D. Y.; Kim J.; Kim G.; Lee K. S.; Kim J.; Paik M. J.; Kim Y. K.; Kim K. S.; Kim M. G.; Shin T. J.; Seok S. Il Perovskite Solar Cells with Atomically Coherent Interlayers on SnO2 Electrodes. Nature 2021, 598, 444–450. 10.1038/s41586-021-03964-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.; Foley B. J.; Park C.; Brown C. M.; Harriger L. W.; Lee J.; Ruff J.; Yoon M.; Choi J. J.; Lee S. H. Entropy-Driven Structural Transition and Kinetic Trapping in Formamidinium Lead Iodide Perovskite. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601650 10.1126/sciadv.1601650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Yoo J. W.; Hu M.; Lee S.; Seok S. Il. Intrinsic Phase Stability and Inherent Bandgap of Formamidinium Lead Triiodide Perovskite Single Crystals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202212700 10.1002/anie.202212700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenzer J. A.; Hellmann T.; Nejand B. A.; Hu H.; Abzieher T.; Schackmar F.; Hossain I. M.; Fassl P.; Mayer T.; Jaegermann W.; Lemmer U.; Paetzold U. W. Thermal Stability and Cation Composition of Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Perovskites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 15292–15304. 10.1021/acsami.1c01547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conings B.; Drijkoningen J.; Gauquelin N.; Babayigit A.; D’Haen J.; D’Olieslaeger L.; Ethirajan A.; Verbeeck J.; Manca J.; Mosconi E.; De Angelis F.; Boyen H. G. Intrinsic Thermal Instability of Methylammonium Lead Trihalide Perovskite. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500477 10.1002/aenm.201500477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yi C.; Luo J.; Meloni S.; Boziki A.; Ashari-Astani N.; Grätzel C.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Rothlisberger U.; Grätzel M. Entropic Stabilization of Mixed A-Cation ABX3 Metal Halide Perovskites for High Performance Perovskite Solar Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 656–662. 10.1039/C5EE03255E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon N. J.; Noh J. H.; Yang W. S.; Kim Y. C.; Ryu S.; Seo J.; Seok S. Il. Compositional Engineering of Perovskite Materials for High-Performance Solar Cells. Nature 2015, 517, 476–480. 10.1038/nature14133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M. R.; Eperon G. E.; Snaith H. J.; Giustino F. Steric Engineering of Metal-Halide Perovskites with Tunable Optical Band Gaps. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5757 10.1038/ncomms6757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conings B.; Drijkoningen J.; Gauquelin N.; Babayigit A.; D’Haen J.; D’Olieslaeger L.; Ethirajan A.; Verbeeck J.; Manca J.; Mosconi E.; De Angelis F.; Boyen H. G.; Angelis F. De.; Boyen H. G.; Haen J. D.; Olieslaeger L. D.; D’Haen J.; D’Olieslaeger L.; Ethirajan A.; Verbeeck J.; Manca J.; Mosconi E.; De Angelis F.; Boyen H. G. Intrinsic Thermal Instability of Methylammonium Lead Trihalide Perovskite. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500477 10.1002/aenm.201500477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K.; Wei M.; Sargent E. H.; Walker G. C. Grain Transformation and Degradation Mechanism of Formamidinium and Cesium Lead Iodide Perovskite under Humidity and Light. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 934–940. 10.1021/acsenergylett.0c02247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty T. A. S.; Winchester A. J.; Macpherson S.; Johnstone D. N.; Pareek V.; Tennyson E. M.; Kosar S.; Kosasih F. U.; Anaya M.; Abdi-Jalebi M.; Andaji-Garmaroudi Z.; Wong E. L.; Madéo J.; Chiang Y. H.; Park J. S.; Jung Y. K.; Petoukhoff C. E.; Divitini G.; Man M. K. L.; Ducati C.; Walsh A.; Midgley P. A.; Dani K. M.; Stranks S. D. Performance-Limiting Nanoscale Trap Clusters at Grain Junctions in Halide Perovskites. Nature 2020, 580, 360–366. 10.1038/s41586-020-2184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min H.; Kim M.; Lee S. U.; Kim H.; Kim G.; Choi K.; Lee J. H.; Seok S. Il. Efficient, Stable Solar Cells by Using Inherent Bandgap of α-Phase Formamidinium Lead Iodide. Science 2019, 366, 749–753. 10.1126/science.aay7044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G.; Min H.; Lee K. S.; Lee D. Y.; Yoon S. M.; Seok S. Il. Impact of Strain Relaxation on Performance of α-Formamidinium Lead Iodide Perovskite Solar Cells. Science 2020, 370, 108–112. 10.1126/science.abc4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. W.; Tan S.; Seok S. Il; Yang Y.; Park N. G. Rethinking the A Cation in Halide Perovskites. Science 2022, 375, 1–10. 10.1126/science.abj1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak P. K.; Moore D. T.; Wenger B.; Nayak S.; Haghighirad A. A.; Fineberg A.; Noel N. K.; Reid O. G.; Rumbles G.; Kukura P.; Vincent K. A.; Snaith H. J. Mechanism for Rapid Growth of Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskite Crystals. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13303 10.1038/ncomms13303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger B.; Nayak P. K.; Wen X.; Kesava S. V.; Noel N. K.; Snaith H. J. Consolidation of the Optoelectronic Properties of CH3NH3PbBr3 Perovskite Single Crystals. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 590 10.1038/s41467-017-00567-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller M. T.; Weber O. J.; Frost J. M.; Walsh A. Cubic Perovskite Structure of Black Formamidinium Lead Iodide, α-[HC(NH2)2]PbI3, at 298 K. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 3209–3212. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duijnstee E. A.; Ball J. M.; Le Corre V. M.; Koster L. J. A.; Snaith H. J.; Lim J. Toward Understanding Space-Charge Limited Current Measurements on Metal Halide Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 376–384. 10.1021/acsenergylett.9b02720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Corre V. M.; Duijnstee E. A.; El Tambouli O.; Ball J. M.; Snaith H. J.; Lim J.; Koster L. J. A. Revealing Charge Carrier Mobility and Defect Densities in Metal Halide Perovskites via Space-Charge-Limited Current Measurements. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 1087–1094. 10.1021/acsenergylett.0c02599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duijnstee E. A.; Le Corre V. M.; Johnston M. B.; Koster L. J. A.; Lim J.; Snaith H. J. Understanding Dark Current-Voltage Characteristics in Metal-Halide Perovskite Single Crystals. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2021, 15, 014006 10.1103/PhysRevApplied.15.014006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q.; Bae S. H.; Sun P.; Hsieh Y. T.; Yang Y.; Rim Y. S.; Zhao H.; Chen Q.; Shi W.; Li G.; Yeng Y. Single Crystal Formamidinium Lead Iodide (FAPbI3): Insight into the Structural, Optical, and Electrical Properties. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 2253–2258. 10.1002/adma.201505002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.; Jiang L.; Wang G.; Huang Y.; Chen H. Theoretical Insight into the CdS/FAPbI3 Heterostructure: A Promising Visible-Light Absorber. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 4393–4400. 10.1039/D0NJ04827E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gompel W. T. M.; Herckens R.; Reekmans G.; Ruttens B.; D’Haen J.; Adriaensens P.; Lutsen L.; Vanderzande D. Degradation of the Formamidinium Cation and the Quantification of the Formamidinium-Methylammonium Ratio in Lead Iodide Hybrid Perovskites by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 4117–4124. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b09805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi T.; Shimakami N.; Kurashina M.; Mizuguchi H.; Yabutani T. Determination of the Acid-Base Dissociation Constant of Acid-Degradable Hexamethylenetetramine by Capillary Zone Electrophoresis. Anal. Sci. 2016, 32, 1327–1332. 10.2116/analsci.32.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrle H.; Scharf U. Tetrahydro-s-Triaziniumsalz: 1. Mitt. Uber Hydro-s-Triazine. Arch. Pharm. 1974, 307, 51–57. 10.1002/ardp.19743070112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Chatelier H. Loi de Stabilité de l’equilibre Chimique. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1884, 99, 786–789. [Google Scholar]

- Gholipour S.; Ali A. M.; Correa-Baena J. P.; Turren-Cruz S. H.; Tajabadi F.; Tress W.; Taghavinia N.; Grätzel M.; Abate A.; De Angelis F.; Gaggioli C. A.; Mosconi E.; Hagfeldt A.; Saliba M. Globularity-Selected Large Molecules for a New Generation of Multication Perovskites. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702005 10.1002/adma.201702005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao W. C.; Liang J. Q.; Dong W.; Ma K.; Wang X. L.; Yao Y. F. Formamidinium Lead Triiodide Perovskites with Improved Structural Stabilities and Photovoltaic Properties Obtained by Ultratrace Dimethylamine Substitution. NPG Asia Mater. 2022, 14, 49 10.1038/s41427-022-00395-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki D. J.; Prochowicz D.; Hofstetter A.; Saski M.; Yadav P.; Bi D.; Pellet N.; Lewiński J.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Grätzel M.; Emsley L. Formation of Stable Mixed Guanidinium-Methylammonium Phases with Exceptionally Long Carrier Lifetimes for High-Efficiency Lead Iodide-Based Perovskite Photovoltaics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3345–3351. 10.1021/jacs.7b12860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fateev S. A.; Petrov A. A.; Khrustalev V. N.; Dorovatovskii P. V.; Zubavichus Y. V.; Goodilin E. A.; Tarasov A. B. Solution Processing of Methylammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite from γ-Butyrolactone: Crystallization Mediated by Solvation Equilibrium. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 5237–5244. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b01906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki D. J.; Stranks S. D.; Grey C. P.; Emsley L. NMR Spectroscopy Probes Microstructure, Dynamics and Doping of Metal Halide Perovskites. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 624–645. 10.1038/s41570-021-00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki D. J.; Prochowicz D.; Hofstetter A.; Péchy P.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Grätzel M.; Emsley L. Cation Dynamics in Mixed-Cation (MA)x(FA)1-XPbI3 Hybrid Perovskites from Solid-State NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10055–10061. 10.1021/jacs.7b04930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi A. Q.; Kubicki D. J.; Prochowicz D.; Alharbi E. A.; Bouduban M. E. F.; Jahanbakhshi F.; Mladenović M.; Milić J. V.; Giordano F.; Ren D.; Alyamani A. Y.; Albrithen H.; Albadri A.; Alotaibi M. H.; Moser J. E.; Zakeeruddin S. M.; Rothlisberger U.; Emsley L.; Grätzel M. Atomic-Level Microstructure of Efficient Formamidinium-Based Perovskite Solar Cells Stabilized by 5-Ammonium Valeric Acid Iodide Revealed by Multinuclear and Two-Dimensional Solid-State NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17659–17669. 10.1021/jacs.9b07381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piveteau L.; Morad V.; Kovalenko M. V. Solid-State NMR and NQR Spectroscopy of Lead-Halide Perovskite Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 19413–19437. 10.1021/jacs.0c07338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwin S. J.; Levilain G.; Marziano I.; Merritt J. M.; Houson I.; Ter Horst J. H. A Structured Approach to Cope with Impurities during Industrial Crystallization Development. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 1443–1456. 10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebli M.; Porenta N.; Aregger N.; Kovalenko M. V. Local Structure of Multinary Hybrid Lead Halide Perovskites Investigated by Nuclear Quadrupole Resonance Spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 6965–6973. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.1c01945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are provided in the figures, table, and Supplementary Information. The raw NMR, SCXRD, PV-SCLC, and Raman data as well as input files of the DFT calculations and optimized geometries are available on Oxford University Research Archive.