Abstract

Primary immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is an acquired autoimmune disorder characterized by isolated thrombocytopenia. Most patients with ITP have antiplatelet antibodies of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) subtype which through interaction with platelet and megakaryocyte glycoproteins result in increased platelet destruction and inhibition of platelet production. There are a variety of therapeutic options available for the treatment of ITP including corticosteroids, IVIgG, TPO-RA, rituximab, fostamatinib, and splenectomy. Long-term remissions with any of these therapies can vary widely and patients may require additional therapy. The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) plays a pivotal role in IgG and albumin physiology through recycling pathways. Efgartigimod is a human IgG1-derived fragment that has been modified by ABDEG technology to increase its affinity for FcRn at both physiologic and acidic pH. The binding of efgartigimod to FcRn blocks the interaction of IgG with FcRn facilitating increased lysosomal degradation of IgG and decreasing total IgG levels. Based on the mechanism of action and the known pathophysiology of ITP as well as the efficacy of other therapies such as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), the use of efgartigimod in patients with ITP is attractive. This article will briefly discuss the pathophysiology of ITP, current treatments, and the data available on efgartigimod in ITP.

Keywords: Efgartigimod, immune thrombocytopenia, Neonatal Fc Receptor

Immune thrombocytopenia

Primary ITP is an acquired autoimmune disorder characterized by isolated thrombocytopenia, platelet count <100 × 109/L with no other identifiable cause or underlying disorder that is associated with thrombocytopenia. This is in contrast to secondary ITP which is associated with underlying conditions such as infections, drugs, rheumatologic disorders, or lymphoproliferative disorders. 1 The exact mechanism that leads to autoimmunity in ITP remains unknown, but it includes an imbalance between effector and regulatory cells leading to the disruption of immune tolerance. 2 This loss of self-tolerance results in abnormal T-cell responses and the production of pathogenic autoantibody.3,4 The exact mechanism by which thrombocytopenia develops in ITP remains unclear. Mechanisms that have been described include the recognition of the antigen (Ag) antibody (Ab) complex on the platelet membrane resulting in opsonization by macrophages, primarily in the spleen. In addition, in some patients, the binding of the antibody to antigens on the megakaryocyte membrane can also result in decreased platelet production. 5 Other potential mechanisms of platelet clearance include Ag-Ab complex activation of the classical pathway of complement 6 resulting in C3 deposition on platelets and opsonization by macrophages in the liver or generation of the membrane attack complex and platelet lysis.7,8 Platelet desialylation, which may be augmented by CD 8+ cytotoxic T cells, can also result in platelet clearance in the liver by Ashwell Morel receptors and Kupfer cells. 9 There are data to implicate not only autoantibodies but also direct cytotoxicity mediated by T cells. 10 Sixty percent to as many as 80% of patients with ITP have detectable antiplatelet autoantibodies. 11 These autoantibodies are almost always IgG in adults but can also be IgM and rarely IgA.12,13 Despite the continually expanding understanding of the heterogeneity of the mechanisms of platelet clearance, it remains unknown if patients with ITP have different pathophysiology of disease from the onset or if the mechanism of platelet clearance evolves over time shifting with length of disease.

The clinical presentation in ITP varies widely. Patients may be asymptomatic or experience spontaneous as well as trauma-induced bleeding including epistaxis, gingival bleeding, GI bleeding, ecchymosis, petechia, and rarely life-threatening gastrointestinal and intracerebral bleeding. 14 It is important to note that bleeding risk in patients with ITP is not reliably predicted by the platelet count, 15 making clinical disease severity very difficult to predict. More recently appreciated are the significant impacts ITP has on the quality of life including fatigue, 16 health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures,17,18 as well as anxiety and depression. 18 Treatment goals in ITP have evolved to not only include reducing risk of bleeding by increasing platelet number but also addressing quality of life issues. Complete response (CR) to treatment in ITP has been defined by the International Working group as a platelet count ⩾100,000 × 109/L with no bleeding and response (R) as a platelet count ⩾30,000 × 109 /L and >2-fold increase in platelet count from baseline and no bleeding, both measured on two visits more than 7 days apart. 19 Standards for improvements in HRQoLs have not been established in ITP but a survey of 1507 patients with ITP around the world indicated that the three most important goals of treatment were achieving healthy platelet counts, preventing worsening of ITP and improving energy levels. 20 It is clear that moving forward ITP therapy must be individualized and address more than just platelet counts.

Currently available ITP therapy

Steroids

Guidelines suggest first-line therapy for primary ITP includes corticosteroids, either prednisone (0.5–2 mg/kg daily for a tapering course lasting 4–8 weeks) or dexamethasone (40 mg daily for 4 days for 1–4 repeating cycles).1,21 A meta-analysis evaluating prednisone versus dexamethasone in previously treated patients with primary ITP revealed no difference in overall platelet response at 6 months (54% versus 53%) and no difference in the rate of sustained response. 22 The adverse effects of short-term steroids can include glucose intolerance, fluid retention, hypertension, and mood and sleep disturbances. Long-term steroid use can have all of the short-term adverse effects plus increased infection risk, proximal muscle weakness, osteoporosis, weight gain, gastric ulcers, as well as adrenal suppression.

Intravenous immunoglobulin

When patients present with bleeding or need a more rapid platelet response than steroids can provide intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIgG) is often used alone or in combination with steroids as first-line therapy. Commonly utilized dosing of IVIgG is either 400 mg/kg/day × 5 days or 1 g/kg/day × 2 days. A randomized trial evaluating IVIgG showed patients who received a single dose of 1 g/kg were more likely to have a response in platelet count by day 4 compared with those who received a lower initial dose (0.5 mg/kg) 67% versus 21%. 23 Adverse events associated with IVIgG infusions can include allergic reactions, hypertension, hypotension, fever, myalgia, arthralgias, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and rash.

Anti D immunoglobulin

Although less commonly utilized, for nonsplenectomized Rh + patients intravenous anti-RhD immune globulin (50–75 µg/kg) is an alternative option to IVIgG. Response rates and time to response are similar to IVIgG; however, anti-RhD will induce some degree of hemolysis. The hemolysis is mild in most patients but can be severe and precipitate disseminated intravascular coagulation in a small number of patients. 24

Up to 70% of adult ITP patients will develop persistent and chronic ITP that requires additional therapy

Second-line treatment for ITP has not been investigated in head-to-head randomized controlled trials so the recommendations are based on single-arm trials, placebo-controlled trials, or clinical case series.

Splenectomy

Given the spleen’s role in ITP, mediating platelet clearance as well as production of autoantibodies, splenectomy can be an effective treatment. In a systematic review of over 2000 adult patients with ITP who had undergone splenectomy, at 29 months post-splenectomy, 66% of patients had maintained a CR. 25 An additional study of 402 patients showed an 85.6% response rate to splenectomy. 26 Longer-term follow-up demonstrated a 20-year relapse-free survival of 67% for those who had responded to splenectomy. 27 Multiple studies also show that rescue therapy remained effective despite splenectomy. Complications from splenectomy include less than 1% postoperative mortality, an increased risk of infection, particularly with encapsulated organisms, and a risk of venous thromboembolism. 25 Although not used as frequently as in the past, splenectomy remains a safe and effective therapy for certain patients with chronic primary ITP but should be reserved until patients have had diagnosis for at least 1 year.

Rituximab

Anti-CD20 therapy with rituximab has been used as an off-label therapy for ITP for a number of years. In patients treated with 4 weekly doses of rituximab 375 mg/m2, response rates in various trials range from 40% to 70% but the response is rarely sustained and decreases to 21% at 5 years post-therapy.28,29

Thrombopoietin receptor agonist

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RA) are approved as a therapeutic option for ITP based on their ability to mimic the function of native thrombopoietin (TPO) increasing megakaryocyte maturation and platelet production. 30 A large systematic review of TPO-RA in ITP revealed a treatment failure rate of only 21% with a low risk of bleeding and all-cause mortality. 31 Currently, there are three TPO-RAs approved for use in patients with ITP, eltrombopag, and avotrombopag which are orally administered and romiplostim which is parenterally administered via subcutaneous injection. There are relatively few adverse effects of TPO-RAs as a class with thrombosis being the primary serious adverse event (SAE). Although real-world data have reported an increased risk of thrombosis with TPO-RAs, the clinical trial data have not demonstrated an increased risk of thrombosis with TPO-RA in ITP compared with placebo. 32

Fostamatinib

Also approved for the treatment of patients with primary ITP, who have failed other therapy, is fostamatinib, a spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor that impairs the clearance of antibody-coated platelets by the monocyte-macrophage system. Fostamatinib is an oral drug with doses ranging from 100 mg twice daily to 150 mg twice daily. The overall response rate in two phase III trials was 43%. Adverse events were mild to moderate and included GI symptoms, hypertension, and elevation of transaminases.33,34

There is other second and beyond, line treatment for ITP including dapsone, danazol, azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, vinca alkaloids, and cyclophosphamide all with some data to suggest efficacy, particularly in refractory patients.

The varied response rates to all forms of therapy as well as the loss of response to some therapies continue to highlight the multiple mechanisms responsible for thrombocytopenia in ITP. It is not a uniform disease and therapeutic decisions need to begin to be guided by a better understanding of the unique mechanism at play in each individual patient.

Neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)

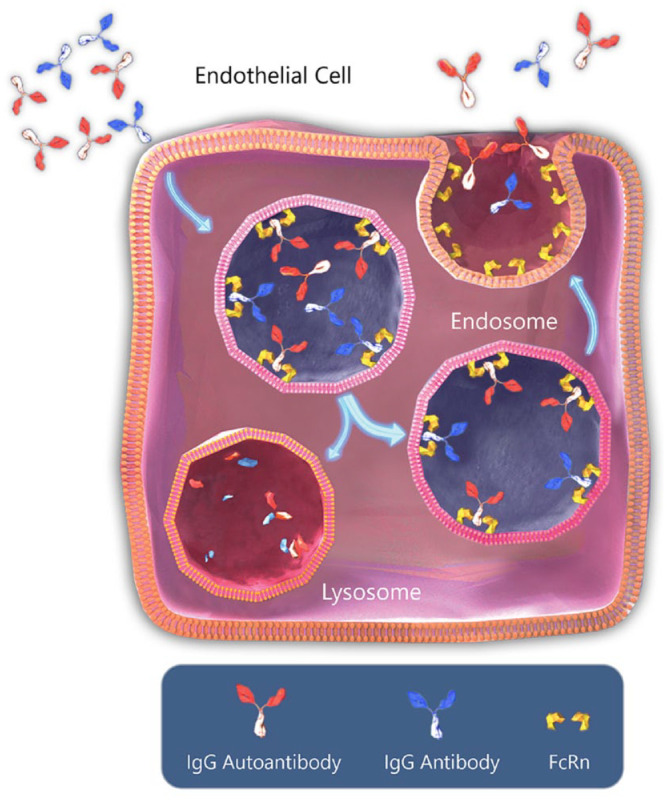

FcRns are found in antigen-presenting cells in multiple organs and tissues, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells. FcRns extend the half-life of serum IgG and albumin by inhibiting their catabolism in lysozymes. As serum is taken into the cells by pinocytosis, cells that express FcRn localize IgG to the endosomal compartment containing the FcRns. Once in the endosome, at acidic pH, the Fc domain of IgG and domains I and III of albumin 35 bind with high affinity to FcRns. The FcRn-bound IgG and albumin are subsequently routed back to the cell surface where a more neutral pH weakens the binding, and the IgG and albumin are then released back into the circulation. (Figure 1) This process contributes to the long half-life of IgG and albumin which is about 3 weeks. The IgG and albumin that are not bound to the FcRn are degraded in the endosome. This recycling process mediated by FcRns plays a role in extending the half-life of pathogenic IgG contributing to the pathology of many IgG-mediated autoimmune disorders. In autoimmune disorders, mediated primarily by IgG autoantibodies, the ability to interact with this pathway and decrease pathogenic IgG levels could provide a strategy for therapeutic intervention.

Figure 1.

Normal IgG recycling via FcRn.

With permission copyright Argenx.

IVIgG has demonstrated efficacy in multiple autoimmune disorders including ITP, AIHA, SLE, and myasthenia gravis. While IVIgG may have multiple mechanisms of action, one proposed mechanism of the activity of IVIgG is, when present in high concentrations, the infused nonspecific IgGs overwhelm the FcRns and allow increased lysosomal degradation of autoantibodies. 36

The observations of the role of FcRn in IgG homeostasis led to the development of a new class of immunoglobulins called Abdegs (antibodies that enhance IgG degradation). These immunoglobulins are engineered with modified Fc regions allowing high affinity binding to FcRns at both acidic and near-neutral pH. Modulating the pH binding range allows this specific class of immunoglobulins to preferentially bind to the FcRn and block the binding of endogenous IgG to FcRns not only in endosomes but also on the cell surface during exocytosis. In preclinical models of a variety of autoimmune diseases, Abdegs demonstrated potential therapeutic activity at doses 25–50 times lower than IVIgG. 37

Efgartigimod

Abdeg technology supplied the framework for the development of efgartigimod, a human IgG1 Fc domain-based novel class of FcRn antagonist. Efgartigimod contains the MST-HN Abdeg mutation that results in a substantially higher affinity for FcRn due to the five amino acid replacements near the FcRn binding site (Figure 2). 38

Figure 2.

Efgartigimod inhibited recycling of IgG.

With permission copyright Argenx.

In the first in human phase I/II study which was randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, 62 healthy volunteers were administered single and multiple ascending doses of efgartigimod and evaluated. Pharmacokinetic data demonstrated the half-life of efgartigimod to be 3–6 days and that specific clearance of serum IgG in the healthy volunteers led to a reduction of total IgG by up to 50% following a single injection and 75% reduction after multiple doses. 39

The role of pathogenic IgG in ITP is well established. Based on the historical use of IgG-depleting treatments like immunoadsorption and plasmapheresis demonstrating a reduction of platelet-associated autoantibodies 40 and increased platelet count in patients with ITP, substantiating the concept of decreasing IgG levels to treat ITP, it was reasonable to propose that the FcRn antagonist efgartigimod would have clinical benefit in patients with ITP.

Efgartigimod in ITP

The first trial of efgartigimod in ITP was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase II study in which patients were randomized to receive four weekly doses of either placebo (PBO) or efgartigimod, at a dose of 5 or 10 mg/kg administered intravenously. The study enrolled adult patients (18–85 years), who had a confirmed primary ITP diagnosis using the American Society of Hematology guidelines, 1 and an average platelet count during the screening of ⩽30 × 109/L. Concurrent ITP therapy (oral corticosteroids, oral immunosuppressants, and oral TPO-RA) was allowed during the study provided patients were on a stable dose and dosing frequency for at least 4 weeks prior to screening, and had to be maintained at that dose during the study. The presence/detection of antiplatelet antibodies was not used as an inclusion criterion. 41 Patients were followed for up to 21 weeks.

The primary outcome evaluated in this phase II trial was safety. Secondary outcomes included platelet count responses and bleeding assessments. Additional measures were pharmacodynamic (PD) and pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters, and immunogenicity. Determination of circulating and platelet-bound autoantibodies was performed.

Thirty-eight participants were randomized to receive four weekly infusions of PBO (N = 12) or efgartigimod at a dose of 5 mg/kg (N = 13) or 10 mg/kg (N = 13). Participants were classified as having either chronic ITP (more than 12 months from diagnosis), 28 of 38 (73.7%), persistent ITP (between 3 and 12 months from diagnosis), 8 of 38 (21.1%), or newly diagnosed (within 3 months of diagnosis) 2 of 38 (5.3%). 32 The median duration of ITP was 4.82 years (range 0.1–47.8). The median number of prior ITP treatments was 2.0 (0–10). 23.7% of patients had previously received rituximab, 36.8% had a TPO-RA, and 15.8% had prior splenectomy. The majority of patients were receiving concurrent ITP therapy at study entry 27 of 38 (71.1%), with an inadequate response allowing them to still satisfy entry criteria of average platelet count <30 × 109/L. 32

Over 90% of patients completed the treatment period. Twelve (31.6%) patients who relapsed during the 21-week follow-up period, entered the open-label treatment period, and received four weekly intravenous infusions of efgartigimod at 10 mg/kg. During the double-blind period, 2 of 12 (16.7%) had received efgartigimod at 5 mg/kg, 6 of 12 (50.0%) had received efgartigimod at 10 mg/kg, and 4 of 12 (33.3%) had received PBO. 32

Safety

At least one treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) was observed in 69.2% of patients treated with efgartigimod 5 mg/kg and 84.6% with efgartigimod 10 mg/kg, and 58.3% with PBO during the blinded portion of the study. 32 These TEAEs were mainly mild or moderate in severity and included petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis, rash, hypertension, and headache. During the open-label portion, the most common TEAE was an increase in alanine aminotransferase in 16.7% of patients. 32 There was only one serious TEAE reported which was worsening of ITP and was felt to be unrelated to efgartigimod. In evaluating other safety parameters, there were no clinically relevant changes in vital signs, electrocardiogram parameters, physical examination, or clinical laboratory assessments observed. No deaths were reported.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

Efgartigimod at both 5 and 10 mg/kg resulted in a rapid reduction of total IgG levels, with a maximum mean decrease of 60.4% from baseline on efgartigimod 5 mg/kg and 63.7% decrease from baseline on 10 mg/kg. 32 The total IgG levels in the PBO group remained unchanged. All four IgG subtypes were reduced equally. There were no clinically relevant changes from the baseline of IgA, IgD, IgE, IgM, or albumin. 32

All patients randomized had demonstrable platelet-associated autoantibodies directed against GPIIb/IIIa, GPIb/IX, and GPIa/IIa in antiplatelet antibody eluates although this was not an inclusion criterion. A reduction greater than 40% for at least one type of platelet-associated autoantibody in 66.7% of patients treated with efgartigimod 5 mg/kg, and 70.0% treated with efgartigimod 10 mg/kg was observed. 32

Efficacy

Analyzing response based on The International Working Group definition of response ‘R’ (platelet count ⩾ 30 × 109/L and < 100 × 109/L, and at least doubling of baseline platelet count confirmed on at least two separate consecutive occasions ⩾ 7 days apart, and the absence of bleeding) and complete response ‘CR’ (platelet count ⩾ 100 × 109/L confirmed on at least two separate consecutive occasions ⩾ 7 days apart, and the absence of bleeding) 19 demonstrated 38.5% of participants in the efgartigimod 5 mg/kg group, 38.5% in the efgartigimod 10 mg/kg group, and two 16.7% in the PBO group achieved either an ‘R’ or a ‘CR’. 32 Three participants, 2 with newly diagnosed ITP in the efgartigimod 5 mg/kg group, and one chronic patient in the efgartigimod 10 mg/kg group had a sustained response throughout the follow-up period (up to day 162). Rescue therapy was administered to 30.8% of participants in the efgartigimod 5 mg/kg group and 23.1% of participants in the efgartigimod 10 mg/kg group during the double-blind period of the study. 32

The main limitation of this phase II study is the short treatment duration, only four weekly doses of efgartigimod making long-term safety and efficacy impossible to evaluate. In addition, the small number of participants and the clinical heterogeneity of the participant population make any observations/conclusions about efficacy challenging although the response rates do suggest a role for FcRn inhibition in the treatment of ITP.

ADVANCE IV

In ADVANCE IV, a phase III, multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial, the efficacy and safety of efgartigimod were evaluated in adults patients (18–85 years of age) with a diagnosis of chronic or persistent ITP supported by a response to at least one prior ITP therapy. 42 Eligibility was based on platelet counts less than 30 × 109/L on 2 separate occasions during the 2-week screening period. Participants were required to have had an inadequate response to two or more prior ITP therapies or one prior and one concurrent therapy. Concurrent therapy with oral corticosteroids, oral TPO RA, oral immunosuppression, dapsone, danazol, and fostamatinib was allowed if at a stable dose and frequency at the time of entry and was maintained throughout the study period. Participants were randomized (2:1 ratio) to receive intravenous (IV) treatment with either efgartigimod 10 mg/kg or matching PBO. Efgartigimod or PBO was administered at the first visit (week 0) then weekly for 3 weeks followed by either weekly or every other week from weeks 4 to 15, with a frequency determined by platelet count response. Dosing was then fixed from week 15 to the end of the trial at week 24. The primary endpoint was evaluated during weeks 19 and 24. Participants who completed the study, at 24 weeks, were eligible to roll over into the open-label extension (OLE), those who did roll into the OLE were followed for 4 additional weeks, total 28 weeks.

A total of 131 participants entered the trial and were randomized to receive either EFG (86 patients) or PBO (45 patients). The two groups were well balanced with mean age 49.3 years, mean duration of ITP diagnosis 10.7 years, 37% of patients in each group had undergone prior splenectomy, and 66.5% of patients in each group had received three or more prior ITP therapies. The discontinuation rate in both groups was similar with 26% of EFG-treated participants and 29% of PBO-treated participants discontinuing treatment mainly due to withdrawal of consent and lack of efficacy. 33

Reasons for discontinuation in the efgartigimod group include adverse event: 3 (3.5%), lack of efficacy: 8 (9.3%), pregnancy: 1 (1.2%), withdrawal of consent: 10 (11.6%) and in the PBO group include, adverse event: 1 (2.2%), lack of efficacy: 5 (11.1%), physician decision: 1 (2.2%), withdrawal of consent: 3 (6.7%), and other: 3 (6.7%). 33

Most of the patients who completed the 24-week study rolled over to the OLE trial (94% of EFG-treated patients and 98% of PBO-treated patients).

Efficacy

The primary endpoint of ADVANCE IV was defined as the proportion of participants with chronic ITP with a sustained platelet count response (⩾50 × 109/L in ⩾4/6 visits during weeks 19–24), in the absence of intercurrent events. 35 The study met the primary endpoint with 21.8% (17/78) of the efgartigimod group achieving a sustained platelet count response compared with 5.0% (2/40) of the PBO group (p = 0.0316). 33 The first of the key secondary endpoints was the number of cumulative weeks of disease control (number of weeks with platelet counts ⩾50 × 109/L) with the efgartigimod group achieving a mean of 6.1 weeks (7.66) compared with the PBO group with a mean of 1.5 weeks (3.23) p = 0.0009. 33 The second key secondary endpoint was sustained platelet count response in all participants (⩾50 × 109/L in ⩾4/6 visits during weeks 19–24) with 25.6% (22/86) of the efgartigimod group compared with 6.7% (3/45) p = 0.0108 in the PBO group achieving this endpoint. 33 The third key secondary endpoint was durable response for at least 6 weeks, which was achieved in 22.1% (19/86) of the efgartigimod group compared with 6.7% (2/45) p = 0.265 of the PBO group. 33 WHO bleeding score improvement was noted in the efgartigimod-treated group, but this was not statistically significant perhaps related to the low number of overall bleeding events in both groups. The response to efgartigimod was rapid with 33 (38.4%) of the efgartigimod group compared with 5 (11.1%) in the PBO group achieving a platelet count of 30 × 109/L at week 1. 33 Ten participants in the efgartigimod group reached a platelet count of at least 100 × 109/L over 3 weeks and were switched to every other week dosing of efgartigimod. Ninety percent of these patients had maintained a sustained platelet count response on every 2-week schedule (Table 1). 33

Table 1.

Advance primary and secondary endpoints.

| Efgartigimod group(86) | Placebo group(45) | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint

a

(platelet count > 50 × 109/L in >4/6 visits weeks 19–24 in chronic ITP patients |

21.8% (17/78) |

5.0% 2/40 |

| Secondary endpoint

a

(number of weeks with platelet count > 50 × 109/L |

6.1 weeks | 1.5 weeks |

| Secondary endpoint

b

(platelet count > 50 × 109/L in >4/6 visits in weeks 19/24 all patients |

25.6% (22/86) |

6.7% 3/45 |

| Secondary endpoint

b

Sustained response for at least 6 weeks |

22.1% (19/86) |

6.7% (2/45) |

| Time to response

b

Platelet count of 30 × 109/L by week 1 |

38.4% (33/86) |

11.1% (5/45) |

ITP, immune thrombocytopenia.

Chronic population.

Chronic and persistent population.

Evaluation of response based on IWG criteria, which combines the platelet count with bleeding scores, may be a more clinically relevant measure of response. An analysis of response based on IWG criteria demonstrated 51.8% (44/86) of the efgartigimod-treated group achieved a response (either a ‘CR’ or an ‘R’) compared with 20% (9/45) of the PBO group. 33

A subgroup analysis demonstrated that efgartigimod outperformed PBO in all groups evaluated, splenectomy, no splenectomy, ITP therapy at baseline, no ITP therapy at baseline, prior number of therapies, region of the world, age, prior rituximab, and prior TPO therapy. 33

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

The mean IgG levels decreased steadily in the efgartigimod group over the first 4 weeks of treatment. The mean maximum reductions in IgG from baseline remained >60% throughout the trial period. 33 No change from baseline in IgG levels were noted in the PBO group. Evaluation in levels of specific antiplatelet autoantibodies has not been reported in the phase III trial.

Safety

TEAEs were reported in 93% of the efgartigimod group and 95.6% of the PBO group. 33 Serious TEAEs were reported in 8.1% (7/86) of the efgartigimod group and 15.6% (7/45) of the PBO group. Serious TEAEs across both groups included bleeding or bleeding events, 5 infections, 4 and worsening of primary ITP.3,33 There were 15 of 85 (17.4%) TEAEs that were deemed treatment-related in the efgartigimod group and 10 of 45(22.2%) in the PBO group. The most common treatment-related TEAEs which were seen more frequently in the efgartigimod group compared with PBO are asthenia (7% versus 0%), fatigue (4.7% versus 2.2%), headache (16.3% versus 13.3%), hypertension (5.8% versus 0%), and nausea (5.8% versus 4.4%). Relationship to treatment was investigator determined. 33 None of the treatment-related TEAEs were graded as serious.

Adverse events of special interest (AESI) included bleeding events, infection, and infusion-related reactions. Bleeding events were reported in 70.9% (61/86) of the efgartigimod group compared with 86.7% (39/45) of the PBO group. Any infection event was reported in 29.1% (25/86) of the efgartigimod group compared with 22.2% (10/45) of the PBO group. Infections were mild to moderate in severity in both groups. Infusion reactions were reported in 11.6% (10/86) of the efgartigimod group and 11.1% (5/45) of the PBO group. There were no statistical differences in these AESI between the efgartigimod and PBO groups. 33 There were no deaths during the trial.

The primary limitation in ADVANCE IV is that half of the patients continued to receive concomitant protocol-allowed ITP therapies including oral steroids, oral TPO-RA, fostamatinib, nonsteroid immunosuppressants, dapsone, and danazol. The dose of these concomitant therapies as per protocol was maintained for the duration of the study, and therefore it was believed that they had a minimal contribution to response.

Conclusion

Data from both trials demonstrated that efgartigimod effectively reduced total IgG levels by up to 60% of baseline values within 4 weeks, and this reduction was maintained for the duration of the trial. There were no new safety signals in the phase III trial confirming the ability to decrease IgG levels safely, continuously in this patient population. The safety profile suggests that decreasing total IgG with efgartigimod did not reach levels associated with an increased risk of infection. 43

In both the phase II and phase III trials, some of the efgartigimod-treated patients showed a relatively rapid increase in platelet counts, while other patients had a delayed time to response. The reasons for this are not well understood, but it has been postulated that due to the known heterogeneity of ITP, there may be differences in the relative contributions of pathogenic autoantibodies between patients. 33

Efficacy in primary ITP patients who had an inadequate response to one or more prior therapies in the phase III trial was demonstrated with 51.8% of participants in the efgartigimod group achieving a response by IWG criteria, including 27.9% complete responders. In the subgroup analysis, sustained platelet count responses favored the efgartigimod-treated patients in all categories evaluated including those subgroups generally considered difficult to treat, participants who had received more than 3 prior therapies for ITP and participants who were older than 65 years. Sustained platelet count responses also favored participants in the efgartigimod group whether or not they had prior splenectomy, prior rituximab, or prior TPO-RA therapy. Participants in the efgartigimod group also spent more weeks with the disease control (platelet count ⩾ 50 × 109/L). Nearly half of the efgartigimod group experienced 3 weeks of disease control compared with 15% of PBO, and 10% of the efgartigimod group had between 20 and 24 weeks of disease control compared with no placebo participants. Weeks spent with disease control clinically translate into more weeks with a decreased likelihood of having a bleeding event. No data have been presented on the impact disease control had on QOL measures in this study.

Future directions

Efgartigimod, with its unique mechanism of action, represents an important treatment option for patients with primary ITP that has not responded well to prior therapies. The rapid response in platelet count seen in some patients receiving efgartigimod, the favorable safety profile, the lack of requirements for vaccines and continued adequate response to vaccines may make efgartigimod an attractive option for studies in first-line or rescue therapy in ITP. The mechanism of action of efgartigimod, reducing levels of total IgG including autoantibody levels leads to a postulation as to whether FcRn inhibition in first-line therapy would impact the immune feedback loop in such a way as to result in longer remissions of ITP. Both of these questions will require additional clinical trials in newly diagnosed patients with longer-term follow-ups.

Advances in understanding the complexity and heterogeneity of ITP continue to occur. With this knowledge, the new goal in ITP therapy should strive for a mechanism to identify the unique pathophysiology of ITP in each individual patient, and define which of the many mechanisms of platelet clearance/ production issues is primarily responsible for the thrombocytopenia at any point in the disease process. Armed with this knowledge, therapy can be directed toward the specific mechanism of platelet clearance/production abnormality ending the current paradigm of trying multiple therapies for ITP until we find one that is effective. Efgartigimod represents a step forward in this endeavor with its unique and specific mechanism of action.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Catherine Broome  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1507-2851

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1507-2851

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Catherine Broome: Conceptualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research funding to institution from Argenx, Alexion, Sanofi, Incyte, and Rigel and honoraria from Sanofi, Argenx, and Alexion.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Neunert C, Terrell DR, Arnold DM, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv 2019; 3: 3829–3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenzie CG, Guo L, Freedman J, et al. Cellular immune dysfunction in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). Br J Haematol 2013; 163: 10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson VS, Jolink AC, Amini SN, et al. Platelets in ITP: victims in charge of their own fate? Cells 2021; 10: 3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Semple JW, Rebetz J, Maouia A, et al. An update on the pathophysiology of immune thrombocytopenia. Curr Opin Hematol 2020; 27: 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang M, Nakagawa PA, Williams SA, et al. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) plasma and purified ITP monoclonal autoantibodies inhibit megakaryocytopoiesis in vitro. Blood 2003; 102: 887–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castelli R, Delilliers LG, Gidaro A, et al. Complement activation in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura according to phases of disease course. Clin Exp Immunol 2020; 201: 258–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Najaoui A, Bakchoul T, Stoy J, et al. Autoantibody-mediated complement activation on platelets is a common finding in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Eur J Haematol 2012; 88: 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peerschke EI, Panicker S, Bussel J. Classical complement pathway activation in immune thrombocytopenia purpura: inhibition by a novel C1s inhibitor. Br J Haematol 2016; 173: 942–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, van der Wal DE, Zhu G, et al. Desialylation is a mechanism of Fc-independent platelet clearance and a therapeutic target in immune thrombocytopenia. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swinkels M, Rijkers M, Voorberg J, et al. Emerging concepts in immune thrombocytopenia. Front Immunol 2018; 9: 880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tani P, Berchtold P, McMillan R. Autoantibodies in chronic ITP. Blut 1989; 59: 44–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cines DB, Wilson SB, Tomaski A, et al. Platelet antibodies of the IgM class in immune thrombocytopenic purpura. J Clin Invest 1985; 75: 1183–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishioka T, Yamane T, Takubo T, et al. Detection of various platelet-associated immunoglobulins by flow cytometry in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2005; 68: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen YC, Djulbegovic B, Shamai-Lubovitz O, et al. The bleeding risk and natural history of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in patients with persistent low platelet counts. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 1630–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slichter SJ, Kaufman RM, Assmann SF, et al. Dose of prophylactic platelet transfusions and prevention of hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 600–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newton JL, Reese JA, Watson SI, et al. Fatigue in adult patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Eur J Haematol 2011; 86: 420–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMillan R, Bussel JB, George JN, et al. Self-reported health-related quality of life in adults with chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol 2008; 83: 150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathias SD, Gao SK, Miller KL, et al. Impact of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) on health-related quality of life: a conceptual model starting with the patient perspective. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008; 6: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood 2009; 113: 2386–2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper N, Kruse A, Kruse C, et al. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) World Impact Survey (iWISh): patient and physician perceptions of diagnosis, signs and symptoms, and treatment. Am J Hematol 2021; 96: 188–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Provan D, Stasi R, Newland AC, et al. International consensus report on the investigation and management of primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2010; 115: 168–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mithoowani S, Gregory-Miller K, Goy J, et al. High-dose dexamethasone compared with prednisone for previously untreated primary immune thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol 2016; 3: e489–e496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godeau B, Caulier MT, Decuypere L, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for adults with autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura: results of a randomized trial comparing 0.5 and 1 g/kg b.w. Br J Haematol 1999; 107: 716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scaradavou A, Woo B, Woloski BM, et al. Intravenous anti-D treatment of immune thrombocytopenic purpura: experience in 272 patients. Blood 1997; 89: 2689–2700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kojouri K, Vesely SK, Terrell DR, et al. Splenectomy for adult patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a systematic review to assess long-term platelet count responses, prediction of response, and surgical complications. Blood 2004; 104: 2623–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vianelli N, Galli M, de Vivo A, et al. Efficacy and safety of splenectomy in immune thrombocytopenic purpura: long-term results of 402 cases. Haematologica 2005; 90: 72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vianelli N, Palandri F, Polverelli N, et al. Splenectomy as a curative treatment for immune thrombocytopenia: a retrospective analysis of 233 patients with a minimum follow up of 10 years. Haematologica 2013; 98: 875–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deshayes S, Khellaf M, Zarour A, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of rituximab in 248 adults with immune thrombocytopenia: results at 5 years from the French prospective registry ITP-ritux. Am J Hematol 2019; 94: 1314–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chugh S, Darvish-Kazem S, Lim W, et al. Rituximab plus standard of care for treatment of primary immune thrombocytopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol 2015; 2: e75–e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuter DJ. The biology of thrombopoietin and thrombopoietin receptor agonists. Int J Hematol 2013; 98: 10–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birocchi S, Podda GM, Manzoni M, et al. Thrombopoietin receptor agonists for the treatment of primary immune thrombocytopenia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Platelets 2021; 32: 216–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Samkari H, Van Cott EM, Kuter DJ. Platelet aggregation response in immune thrombocytopenia patients treated with romiplostim. Ann Hematol 2019; 98: 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bussel J, Arnold DM, Grossbard E, et al. Fostamatinib for the treatment of adult persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia: results of two phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Hematol 2018; 93: 921–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bussel JB, Arnold DM, Boxer MA, et al. Long-term fostamatinib treatment of adults with immune thrombocytopenia during the phase 3 clinical trial program. Am J Hematol 2019; 94: 546–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilsen J, Bern M, Sand KMK, et al. Human and mouse albumin bind their respective neonatal Fc receptors differently. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akilesh S, Petkova S, Sproule TJ, et al. The MHC class I-like Fc receptor promotes humorally mediated autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest 2004; 113: 1328–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel DA, Puig-Canto A, Challa DK, et al. Neonatal Fc receptor blockade by Fc engineering ameliorates arthritis in a murine model. J Immunol 2011; 187: 1015–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ober RJ, et al. Engineering the Fc region of immunoglobulin G to modulate in vivo antibody levels. Nat Biotechnol 2005; 23: 1283–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ulrichts P, Guglietta A, Dreier T, et al. Neonatal Fc receptor antagonist efgartigimod safely and sustainably reduces IgGs in humans. J Clin Invest 2018; 128: 4372–4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snyder HW, Jr, Cochran SK, Balint JP, Jr, et al. Experience with protein A-immunoadsorption in treatment-resistant adult immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 1992; 79: 2237–2245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newland AC, Sánchez-González B, Rejtő L, et al. Phase 2 study of efgartigimod, a novel FcRn antagonist, in adult patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Am J Hematol 2020; 95: 178–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broome CM, McDonald V, Miyakawa Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous efgratigimod in adults with primary immune thrombocytopenia: results of a phase 3, multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial (ADVANCE IV). Blood 2022; 140: 6–8.35797019 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Furst DE. Serum immunoglobulins and risk of infection: how low can you go? Semin Arthritis Rheum 2009; 39: 18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]