Abstract

Background

Telemedicine is a quickly developing service that offers more people the access to effective and high-quality healthcare. Societies residing in rural places tend to travel long distances to receive health care, usually have limited access to health care and/or postpone getting health care until a health emergency occurs. However, for telemedicine services to be accessible, a number of prerequisites including the availability of cutting-edge technology and equipment in rural areas must be present.

Objective

This scoping review aims to collect all available data on the viability, acceptability, challenges and facilitators of telemedicine in rural areas.

Methods

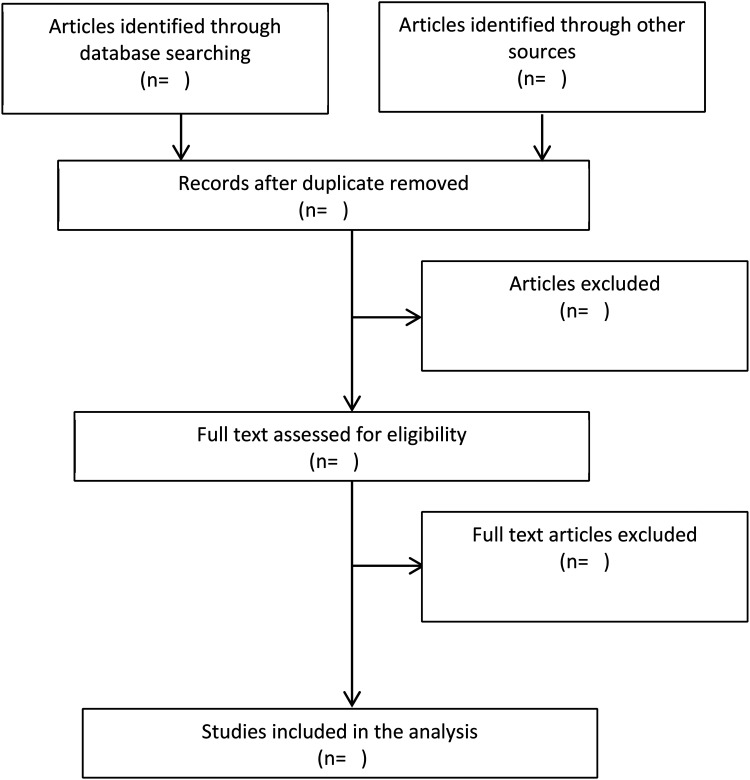

PubMed, Scopus and Medical collection of ProQuest are the databases chosen for an electronic search of the literature. Identification of the title and abstract will be followed by an evaluation of the paper's accuracy and eligibility in a two-fold mode; whereas the identification of papers will be openly and completely described using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) flowchart.

Conclusion

This scoping review would be among the first to offer a thorough evaluation of issues related to the viability, acceptance and implementation of telemedicine in rural areas. In order to improve the conditions of supply, demand and other circumstances relevant to the implementation of telemedicine, the results would be helpful in providing direction and recommendations for future developments in the usage of telemedicine, particularly in rural areas.

Keywords: Feasibility, facilitators, barriers, acceptance, telemedicine, rural community

Introduction

Over the past several decades, technological advancements drastically increased the accessibility and quality of digital health, including Telemedicine. 1 Historically, the predecessor of this technology dates back to the 1920s, when a doctor conducted a consultation with a patient at a dialysis facility using real-time video. 2 The institution of a closed-circuit television connection between Norfolk State Hospital and the Nebraska Psychiatric Institute between the late 1950s and the early 1960s was another well-liked application of hospital-based telemedicine. 3 As per the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), telemedicine is service that tries to work on a patient's health by permitting a two-way, steady intuitive correspondence between a doctor and a patient at a far-off site. 4 Albeit comparative, the terms ‘telehealth’ and ‘telemedicine’ ought not be utilized conversely. Telehealth alludes to ‘the utilization of media communications and data innovation (IT) to give admittance to health evaluation, determination, intercession, counsel, oversight and data across a distance’. 4 While telemedicine includes phone conversations, still image transmission and other forms of communication, along with providing clinical and nonclinical applications over long distances. 2

Rising medical care costs and the requirement for better therapy spurs more emergency clinics to examine more about the advantages of telemedicine. These medical clinics expect to get further developed contact among doctors and far off patients, as well as a superior use of medical care offices. Besides, telemedicine advances better availability, in this way coming about into the patients’ whole adherence to their solution care plans and less medical clinic re-confirmations. The expanded contact by telemedicine stretches out additional in specialist-to-specialist correspondence too through the structure of encouraging groups of people to trade their abilities and give better medical care administrations. 5 Telemedicine has a huge number of advantages towards the patient, the medical care framework and the supplier.6–8

Telemedicine is a fast-expanding service that provides improved access to high-quality, efficient and cost-effective healthcare, particularly in the middle of the present COVID-19 pandemic. 1 This occurs because both patients and healthcare providers want to prevent the spread of COVID-19, which can be spread both directly and indirectly through droplet and human-to-human transmission and contaminated objects and airborne contagion, respectively.9,10 As per the report from the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Telehealth visiting by Medicare recipients expanded essentially with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among clinicians, health experts had the most elevated expansion in telehealth visits from 1% in 2019 to 38.1% in 2020.10,11 All the more in this way, telehealth visits to experts became as normal as in-person visits towards the finish of 2020. The numeral of Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries making telehealth visits increased by 63-fold (nearly 52.7 million) in 2020 from approximately 840,000 in 2019.10,11

Individuals living in rural communities have restricted admittance to medical services, have significant distances to get medical care, as well as postpone medical care until they experience a health emergency. The restricted admittance to medical services could bring about chronic frailty results, which is in this way a social and financial weight for both the patient and the medical care framework. Telehealth expands the extent of health services, giving the chance to diminish boundaries towards procuring medical care in rural communities. 12 Surely, the existence of telemedicine is anticipated to solve the problem of access to health services in remote areas with inadequate health care experts and resources.13,14

However, for telemedicine services to be provided, several conditions including the realization of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, big data analytics, and mobile technology should first be sustained.15,16 Consequently, this circumstance permits discrepancies in access to telemedicine services between urban and rural populations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, rural youths encountered additional challenges in accessing the technology and connectivity needed for isolated education and telehealth. 17 In addition, the acceptance of telemedicine within the urban and rural communities was also different, whereby the adoption rates increased with the urbanity of the residence. 18

Several studies have been conducted to examine various aspects of the use of telemedicine and telehealth in rural areas. Tsou et al. investigated the effectiveness of using telemedicine in the emergency department. 19 Another study looked at the satisfaction of telemedicine users in rural areas, and two other studies looked at telemedicine use in rural areas in India and the United States.20–22 However, specifically, information about the feasibility and acceptance of telemedicine in rural areas has not been well synthesized and summarized for easy understanding. This review would demonstrate an understanding telemedicine as a help conveyance model in giving word-related treatment, exercise-based recuperation and discourse language treatment to rural population. 20 A review on the utilization of telemedicine in the United States showed that Telehealth standards were related to positive results for the patients and medical services experts, proposing that the model could be doable and successful. 12 Furthermore, this scoping review aims to cover all published information related to the feasibility, acceptability, barriers and facilitation of telemedicine in rural settings.

Method

This paper will use a scoping method for the review by adopting the methodology from Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scoping review protocol. 23 A scoping review is aimed at mapping the important concepts and answering a more extensive research question beyond those pertaining the outcome or experience of an intervention.24–26 Therefore, no patients were involved in this study and patient consent for publication is not required. This review will study the factors related to the acceptance and implementation of telemedicine in rural areas. A total of five steps suggested by Tricco et al. will be adopted in this research; (1) identifying the study question; (2) identifying pertinent previous research; (3) selection using an iterative group technique; (4) charting the data by summarizing quantitative data and qualitative thematic research; and (5) collate, summarize and report the results. 27 However, recommended consultation with stakeholders will not be implemented since it is considered an optional component of scoping reviews.24,27 Moreover, the quality of the article or any bias risk will not be calculated since this study is a scoping review.24,25 Since this is a study protocol, A PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist is completed for only title, abstract, introduction and method section and included in the Supplemental appendix. 28

Formulation of research questions

Scoping review questions are normally expansive and the point of these types of reviews is, to sum up, the scope of confirmations in the space of interest. The next questions were identified; (1) how is the feasibility of telemedicine in rural areas? (2) What are the factors related to the acceptance of telemedicine? (3) What are the potential obstacles and facilitators towards the performance of telemedicine? To develop the focus of the examination and search strategy, the Population, Interest and Context (PICo) framework will be used to analyze the human experience and social phenomena as shown in Table 1. 29 The framework will assist in developing suitable search terms to describe the problem, as well as defining both the inclusion and exclusion criteria. 30

Table 1.

PICo framework for deciding the eligibility of the scoping review question.

| Population | Health worker and manager, patient, insurance company, government |

|---|---|

| Phenomenon-of-interest | Acceptance and implementation of telemedicine |

| Context | Rural area |

Identifying relevant previous studies (search strategy, data sources)

The initial consultation meeting with the Universitas Indonesia librarian will be held in order to develop a comprehensive search strategy. A scoping search of the literature using PubMed will be performed in order to provide valuable information regarding the amount of literature already available for the review question. 31 Three selected databases, MEDLINE through PubMed, Scopus and Health and Medical collection of ProQuest, will be chosen as a base necessity to ensure sufficient and effective inclusion. Relevant published articles will be obtained using a full keyword search which is to be performed with Boolean AND/OR, whereas for Mesh Term and subheadings PubMed will be used (Table 2).

Table 2.

Example search strategy for the three broad concept categories in PubMed.

| Concept category (combining with AND) | Search terms (combining with OR) |

|---|---|

| Telemedicine | ((“telepathology"[MeSH Terms] OR “teleradiology"[MeSH Terms] OR “telemedicine"[MeSH Terms] OR (“telerehabilitation"[Title/Abstract] OR “mobile health"[Title/Abstract] OR “mhealth"[Title/Abstract] OR “telehealth"[Title/Abstract] OR “telemonitoring"[Title/Abstract] OR “telecare"[Title/Abstract] OR “remote consultation"[Title/Abstract] OR “teleconsultation"[Title/Abstract])) |

| Implementation | (“Patient Acceptance of Health Care"[All Fields] OR “Patient Acceptance of Health Care"[MeSH Terms] OR (“Acceptance"[Title/Abstract] OR “Adoption"[Title/Abstract] OR “behavioral intention"[Title/Abstract] OR “intention to use"[Title/Abstract] OR “effectiveness"[Title/Abstract] OR “Challenge"[Title/Abstract] OR “Barrier"[Title/Abstract] OR “Facilitator"[Title/Abstract] OR “Supporting factor"[Title/Abstract])) |

| Rural area | (“hospitals rural"[All Fields] OR “Rural Population"[All Fields] OR “Rural Health"[All Fields] OR “Rural Health Services"[MeSH Terms] OR (“Rural Population"[Title/Abstract] OR “Rural Health"[Title/Abstract] OR “Rural Health Services"[Title/Abstract] OR “rural"[Title/Abstract] OR “remote area"[Title/Abstract] OR “village"[Title/Abstract]))) AND (y_10[Filter]) |

Study selection process

The determination cycle in this review is two-fold. The primary reviewer (BA and AN) will screen the articles identified in the pursuit at the title and abstract levels, though the other extra reviewers (AN, WM, SS, HY IA) will verify the articles’ accuracy and eligibility before obtaining full texts. Double screening for each phase will be applied in order to avoid systematic (inconsistent in applying the study inclusion criteria) and random (careless mistakes) errors. 32 Screening of results will be managed using Rayyan software. De-duplication will be applied before the screening phase by using Rayyan software. Rayyan software was one of the most accurate software programs for identifying duplicate references. 33

The telemedicine referred to in this study covers three types, namely synchronous, asynchronous and remote monitoring. 34 In this study, rural areas refer to a 2005 World Bank Policy Research Paper that proposes an operational definition of rurality characterized by low population density and remoteness from major cities. 35 The usability of the system characterizes feasibility, whereas acceptability reflects the extent to which people receiving a healthcare intervention consider it appropriate. 36

Targeted articles’ dates were those ranging from 2010 to 2022, written in English language, and having no geographical limitations. According to a study, studies related to the use of technology published prior to 2010 depicted a condition distinct from the current state, for example in terms of technological challenges and knowledge. 37 Moreover, we made a selection based on the English language considering the absence of experts on our team who understand certain languages other than English. Experimental and empirical analyses such as randomized and non-randomized studies, surveys, qualitative descriptive and cohort studies both using quantitative and qualitative designs that reported on any shape of feasibility, acceptance, barriers and facilitators related to the implementation of telemedicine in rural areas are eligible to be included in this review. However, this review will exclude articles with evidence on the related topic but written in non-English languages.

Charting the data

Charting the data is aimed at creating a descriptive synopsis of the results that addressed the scoping review's objectives, and ideally answering the review's questions. Data will be extracted using Microsoft Word and the elements of the extraction will involve (1) Author(s), (2) Year of publication, (3) Origin/country of origin, (4) Aims/purpose, (5) Study population and sample size, (6) study design, (7) implementation process (acceptance), (8) obstacles and facilitators to performance and (9) outcome (feasibility).

Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart was utilized to describe the process of identifying articles in a comprehensive and transparent manner. 28 The search results will be presented using modified preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in a flow diagram (PRISMA-ScR). 28 Figure 1 depicts the selection procedure for the proposed study. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) Framework will be used to generate initial codes. 38 The framework is used because it could identify implementation barriers and facilitators. 39 The evidence extracted from each source will be summarized narratively into key themes.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the selecting process for including analysis in the examination.

Discussion

Results of this scoping review provide a complete picture of the acceptance, challenges and supporting factors in implementing telemedicine in rural areas. This research describes the influential factors in the implementation of telemedicine, both in terms of demand and supply. This study describes the conditions facilitating telemedicine implementation in rural areas from countries with high, middle and low economic levels, as well as from various parts of the world. Therefore, factors related to the implementation of telemedicine in this study could be contextualized with conditions in various countries in order to reduce the tendency of merely describing telemedicine use in only rural areas of high-income countries, where usage is generally higher than in lower-income countries.

Ethical issues will also be summarized as they remain fundamental in health study. However, since the scoping review methodology consists of reviewing and collecting data from publicly available materials, this study will not require ethics approval. Moreover, this protocol has been registered at open science framework with public profile identifier: https://osf.io/wvsk3/. In terms of dissemination activities, the scoping review is to be submitted for publication in a scientific journal. In particular, the study would help future researchers to better the shapes of their future projects using telemedicine, as well as considering this origin of information as a valuable option to answer some researchers’ research questions.

Limitations

Scoping reviews have inherent limits due to their emphasis on providing breadth rather than depth of information about a certain subject. 27 Due to the research team's capabilities, we limited the included studies to English-language publications; consequently, our findings are only applicable to English-language scoping reviews. The context-specific generalizability of review results may be limited because telemedicine is technology-driven and high-income nations are assumed to have greater access to and expertise with the use of technology than LMIC. However, the results should be understood through the pragmatic lens of what is feasible and cheap in the context in which interested parties seek to investigate the use of telemedicine. 37

Conclusion

This study is anticipated to be an important input for both the government and private sector in their success in use of telemedicine that has proven to be an effective technology leading to the increased access of the population to health services. In addition, this study would provide input to researchers’ ability to carry out further research on what had not been studied before but encompassed by this scoping review.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231171236 for Feasibility, acceptance and factors related to the implementation of telemedicine in rural areas: A scoping review protocol by Badra Al Aufa, Ari Nurfikri, Wiwiet Mardiati, Sancoko Sancoko, Heri Yuliyanto, Mochamad Iqbal Nurmansyah, Imas Arumsari and Ibrahim Isa Koire in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank DRPM Unversitas Indonesia for their support for this study.

Footnotes

Contributorship: BA was responsible for conceptualizing the study, collecting the literature, writing the first draft, and the final revision of the review protocol. IA, AN, WM, S, HY assisted in conceptualization, assisted in the literature collection, and approved the final revision of the protocol. MIN was responsible for conceptualizing the study, collecting the literature, writing the first draft, and the final revision of the review protocol. IIK assisted in writing the first draft, and the final revision of the review protocol.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This being a scoping review of publicized literature, ethics approval will not be needed.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Direktorat Riset dan Pengembangan, Universitas Indonesia (The Directorate of Research and Development of Universitas Indonesia) with grant number: NKB-766/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2022.

Guarantor: BA.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD: Badra Al Aufa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7449-6799

References

- 1.Kichloo A, Albosta M, Dettloff K, et al. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Fam Med Community Health 2020; 8: e000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field MJ. (ed.) Telemedicine: A Guide to Assessing Telecommunications in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US), 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Institute of Medicine . The Role of Telehealth in an Evolving Health Care Environment: Workshop Summary. Lustig TA, editor. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Telemedicine [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/telemedicine/index.html.

- 5.Haleem A, Javaid M, Singh RPet al. et al. Telemedicine for healthcare: capabilities, features, barriers, and applications. Sensors Int 2021; 2: 100117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Medical Association . Telehealth Implementation Playbook. 2022.

- 7.Martin RD. Leveraging telecommuting pharmacists in the post-COVID-19 world. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2020; 60: e113–e115. PMID: 32839136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett ML, Ray KN, Souza Jet al. et al. Trends in telemedicine use in a large commercially insured population, 2005-2017. JAMA 2018; 320: 2147–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lotfi M, Hamblin MR, Rezaei N. COVID-19: transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. Clin Chim Acta [Internet] 2020; 508: 254–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suran M. Increased use of medicare telehealth during the pandemic. JAMA 2022; 327: 313–313. PMID: 35076683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samson LW, Tarazi W, Turrini Get al. et al. Medicare Beneficiaries’ Use of Telehealth in 2020: Trends by Beneficiary Characteristics and Location | ASPE. 2021.

- 12.Butzner M, Cuffee Y. Telehealth interventions and outcomes across rural communities in the United States: narrative review. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e29575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen M, D’Agostino D, Gregory P. Addressing rural health challenges head on. Mo Med 2017; 114: 363. PMID: 30228634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbosa W, Zhou K, Waddell E, et al. Improving access to care: telemedicine across medical domains. Annu Rev Public Health 2021; 42: 463–481. PMID: 33798406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jalal S, Nicolaou S, Parker W. Artificial intelligence, radiology, and the way forward. Can Assoc Radiol J 2019; 70: 10–12. PMID: 30691556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jagadeeswari V, Subramaniyaswamy V, Logesh Ret al. et al. A study on medical internet of things and big data in personalized healthcare system. Health Inf Sci Syst 2018; 6: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graves JM, Abshire DA, Amiri Set al. et al. Disparities in technology and broadband internet access across rurality: implications for health and education. Fam Community Health 2021; 44: 44. PMID: 34269696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Amaize A, Barath D. Evaluating telehealth adoption and related barriers among hospitals located in rural and urban areas. J Rural Health 2021; 37: 801–811. PMID: 33180363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsou C, Robinson S, Boyd J, et al. Effectiveness of telehealth in rural and remote emergency departments: systematic review. J Med Internet Res [Internet] 2021; 23: e30632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harkey LC, Jung SM, Newton ERet al. et al. Patient satisfaction with telehealth in rural settings: a systematic review. Int J Telerehabil [Internet] 2020; 12: 53–64. PMID: 33520095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peri SS, Bagchi AD, Baveja A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of telemedicine in reproductive and neonatal health in rural and low-income areas in India. Telemedicine and e-Health [Internet] 2022; 28: 1251–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butzner M, Cuffee Y. Telehealth interventions and outcomes across rural communities in the United States: narrative review. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e29575. PMID: 34435965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth [Internet] 2020; 18: 2119–2126. PMID: 33038124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol: Theory Practice 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13: 141–146. PMID: 26134548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol [Internet] 2016; 16: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467–473. PMID: 30178033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern C, Jordan Z, Mcarthur A. Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. Am J Nurs 2014; 114: 53–56. PMID: 24681476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bettany-Saltikov J. Learning how to undertake a systematic review: part 2. Nurs Stand 2010; 24: 47–56. PMID: 20860325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atkinson LZ, Cipriani A. How to carry out a literature search for a systematic review: a practical guide. BJPsych Adv [Internet] 2018; 24: 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waffenschmidt S, Knelangen M, Sieben W, et al. Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: A methodological systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol [Internet] 2019 [cited 2022 Nov 17]; 19: –9. PMID: 31253092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKeown S, Mir ZM. Considerations for conducting systematic reviews: evaluating the performance of different methods for de-duplicating references. Syst Rev [Internet] 2021 [cited 2022 Nov 17]; 10: –8. PMID: 33485394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mechanic OJ, Persaud Y, Kimball AB. Telehealth Systems. StatPearls [Internet] 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 17]; PMID: 29083614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chomitz KM, Buys P, Thomas TS. QUANTIFYING THE RURAL-URBAN GRADIENT IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2022 Nov 17]. Report No.: 3634. Available from: http://econ.worldbank.org.

- 36.Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet] 2017; 17: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nizeyimana E, Joseph C, Louw QA. A scoping review of feasibility, cost-effectiveness, access to quality rehabilitation services and impact of telerehabilitation: A review protocol. Digit Health 2022; 8: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DEet al. et al. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 2017; 16: 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci [Internet] 2009; 4: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076231171236 for Feasibility, acceptance and factors related to the implementation of telemedicine in rural areas: A scoping review protocol by Badra Al Aufa, Ari Nurfikri, Wiwiet Mardiati, Sancoko Sancoko, Heri Yuliyanto, Mochamad Iqbal Nurmansyah, Imas Arumsari and Ibrahim Isa Koire in DIGITAL HEALTH