Abstract

Dance movement psychotherapy can be physically and psychologically beneficial for children with autism spectrum disorder. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic required therapy to take place online. However, tele-dance movement psychotherapy with children with autism spectrum disorder has yet to be studied. This mixed methods study involving qualitative research and movement analyses entailed providing tele-dance movement psychotherapy to children with autism spectrum disorder and their parents, during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, and exploring its potential benefits and challenges. The parents who completed the programme reported positive outcomes including the child's social development, enjoyment, improved understanding of their child, insight and ideas, as well as relationship-building. Movement analyses using the Parent Child Movement Scale (PCMS) lent greater insight into these developments. All of the parents reported challenges in participating in tele-dance movement psychotherapy. These were related to screen-to-screen interactions, home, and physical distance. There was a relatively high attrition rate. These findings highlight the challenges of tele-dance movement psychotherapy with children with autism spectrum disorder and the unique benefits of meeting in person whilst the positive outcomes may indicate that tele-dance movement psychotherapy can be beneficial, perhaps particularly as an interim or adjunct form of therapy. Specific measures can be taken to enhance engagement.

Keywords: Dance movement psychotherapy, autism spectrum disorder, teletherapy, creative arts therapies, children, coronavirus disease 2019, family-centred, parent-child, qualitative<studies, mixed methods<studies

Introduction

Autism

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autism spectrum condition, refers to a neurodevelopmental condition that is characterised by (a) social communication atypicality and (b) restricted/repetitive sensory behaviours and/or interests. 1 In the United Kingdom, where this study was conducted, the diagnosis of ASD in children is estimated to be around 1.6%. 2 The prevalence rate of children with ASD has increased by 132% from 2010/2011 to 2018/2019, based on annual censuses of schools in the United Kingdom in a longitudinal study. 3

The words ‘autism spectrum’ denote the variation amongst individuals with ASD. This variation can include symptom severity and other factors, such as intelligence; for example, an estimated 60%–70% of people on the autism spectrum have learning disabilities. 4 Others do not, and some have at least average or above-average IQ (Intelligence Quotient). It is estimated that around 70% of people with ASD have an additional condition, often unrecognised, 5 including mental health conditions, neurodevelopmental conditions, and other conditions.

Dance movement psychotherapy and children with ASD

Given the heterogeneous nature of ASD, alongside overarching social communication atypicality, dance movement psychotherapy (DMP) may have a unique role due to its focus on body movement as an instrument of communication and expression. 6 First, body movement plays a substantive role in communication. 7 Up to 30% of people with ASD are non-speaking (completely, temporarily or in certain contexts), 8 hence the opportunity to communicate non-verbally may be an important one. Secondly, body movement is present even in fetal development, making it the first language spoken between mother and child. This speaks to its primacy in communication. Thirdly, the developmental nature of movement allows interaction with children of varying physical and psychosocial developmental stages.9,10

Taken together, DMP, which uses both verbal and non-verbal means of communication, assessment, and intervention, 6 can build a bridge to reach individuals on the spectrum. This is in contrast to other interventions that require a certain level of verbal and cognitive capacity. Commonly prescribed treatments for individuals with ASD with co-existing mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, are Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and emotion recognition training. 11 However, many individuals with ASD struggle to engage with these treatments as they predominantly involve talking and thinking about emotions, which can often be challenging given that an estimated 60%–70% of people with ASD have co-occurring learning disabilities 4 whilst an estimated 30% are non-verbal or limited verbally. 8

Furthermore, typical of creative arts therapies, DMP focuses on utilising an individual's strengths and abilities to promote healing and growth, which is a strengths-based approach, increasingly used in the field of autism. Lastly, in contrast to many other interventions, DMP is a relational process. 6 By default, it works directly with one of the core challenges in ASD, that of socialisation. It also provides an avenue for the individual with ASD to be seen and heard within a meaningful context, and not merely to be acted upon.

A narrative review 12 on this topic reveals that DMP can indeed be beneficial for children with ASD psychologically and physically. A systematic review 13 suggested that DMP can improve social skills in individuals with ASD, particularly through mirroring interventions, but more evidence-based studies are needed. Another recent systematic review 14 echoed this, reporting that the quality of studies need to be improved but DMP can potentially promote wellbeing in several ways. Taken together, these reviews highlight the potential of DMP and the need for further research.

Tele-DMP with children with ASD

At the time of the study, the coronavirus pandemic made it challenging to conduct DMP due to the health risk involved in meeting up physically. This was confounded by the difficulty of maintaining social distancing with children due to their usual levels of physical interaction. A solution that did not require meeting up in person was teletherapy, a form of telehealth, which refers to the delivery of healthcare services from a distance.

Although there was no literature on tele-DMP and children with ASD at the time, a systematic review 15 examining a range of telehealth services and ASD, including diagnostic assessments, early intervention, and language therapy suggested that children with ASD, their families, and teachers may benefit from using telehealth. Meanwhile, a more recent systematic review 16 on telehealth interventions for children with ASD reported that telehealth programmes are very acceptable, comparable to face-to-face interventions, and can train implementers in interventions.

A qualitative study 17 was conducted to identify the feasibility, essential requirements, and potential barriers to delivering therapy support in allied health services to children with ASD via video-conferencing. Amongst other findings, the authors reported that collaboration between families and teachers was considered essential, and autism-specific knowledge was deemed beneficial by families. However, barriers included scheduling and delivery of interventions requiring physical support.

The often physical nature of DMP may indeed pose a challenge in this regard. A recent study 18 on tele-DMP with neurotypical children and older adults in lockdown in Italy illustrated its use in connecting people in times of isolation during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. The feedback given by elementary school teachers in this study was that tele-DMP helped the children connect with their bodies and with what was beyond the confines of their rooms, supporting the development of web skills in interacting from a distance.

Such findings highlighted the potential of tele-DMP in this context but also its challenges. This study was designed to explore the potential benefits and challenges of tele-DMP with children with ASD. Given the physical nature of DMP and the diversity of children on the spectrum, their parents were enlisted to accompany their children in DMP. The research questions were: 1) What are the potential benefits of tele-DMP for children with ASD and their parents, and 2) What would be the challenges of tele-DMP with children with ASD and their parents?

Methods

Ethics

This study obtained ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong(reference number: EA2004019) andInformed, written consent was obtained from parents. Pseudonyms were used in the reporting of the study to protect the confidentiality of participants.

Sampling and recruitment

Relevant special educational needs schools were invited to participate in the study. Of the interested schools, one was chosen, an all-ages (5–19 years old) school in North London for students with a primary diagnosis of ASD. The criteria for participating in this study were that children should have a formal diagnosis of ASD and be between the ages of 5–11. This age range was set as the aim was to explore the intervention with primary-school-aged children, who may have a special window of opportunity to develop in relation with their parents. Whilst the children could be non-verbal or have limited verbal capacity, their parents should be verbal. For both parents and children, they could be of any gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic background. Suitable families who met the criteria and who could potentially commit to therapy were identified with the help of the key stage headteacher. Using purposive sampling, information sheets detailing the purpose of the study and informed consent forms were distributed by the school to suitable parents. Of the families that met the criteria, seven were interested and five signed up for the study.

Participants

Five families signed up for this study. The demographics of the parents and their children with ASD are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of the participants.

| Participants (parent and child) | Parent's age (years); gender | Marital status | Level of education | Employment | Child's age (years); gender | Verbal capacity | Co-occurring conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A and B | 34; Female | Divorced | Tertiary | Unemployed | 9; Male | Limited verbally | Severe learning disabilities |

| C and D | 36; Female | Single | Tertiary | Part-time employment | 7; Male | Non-verbal | Severe learning disabilities |

| E and F | 51; Female | Single | Tertiary | Unemployed | 6; Female | Limited verbally | Moderate to severe learning disabilities Fragile-X gene |

| G and H | 38; Female | Married | Tertiary | Unemployed | 7; Male | Limited verbally | Sensory processing disorder |

| I and J | 46; Female | Married | Tertiary | Self-employed | 9; Male | Limited verbally | Moderate to severe learning disabilities |

The tele-DMP sessions

The tele-DMP sessions took place online using Zoom video conferencing. Sessions involving the parent-child dyads altogether were scheduled once a week for 6 weeks and took place online, with the parent-child dyads in their homes and the therapist-researcher in hers. Sessions lasted from 45 minutes to an hour. They were led by the researcher, a registered dance movement psychotherapist.

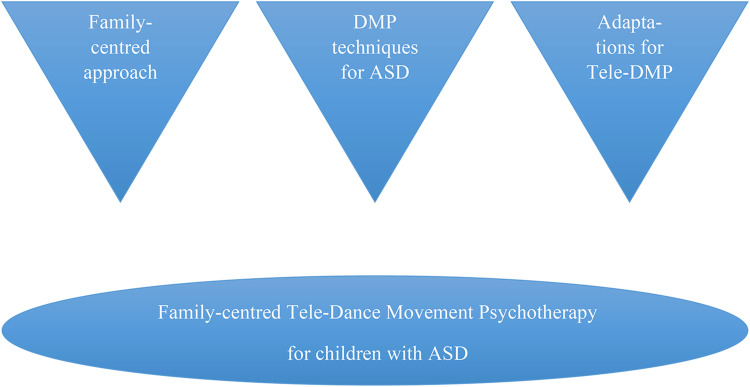

Therapy was formed and informed by several components, namely the family-centred approach; DMP techniques based on literature and the therapist-researcher's work experience; as well as adaptations for tele-DMP based on a groundwork study 19 conducted beforehand. The chart in Figure 1 summarises this.

Figure 1.

Therapy components.

Working from a family-centred approach, the therapist-researcher sought the parents’ feedback after every session and where suitable, their suggestions were incorporated in the next session, as a form of working collaboratively. This fine-tuning based on the parents’ feedback enhanced the parents and children's engagement. As an example, to improve their participation, the parents requested sessions solely for themselves, without their children, in order to experience first-hand the therapeutic activities and improve their knowledge before trying it out with their children. The parents also suggested their children's favourite songs to motivate them.

The interventions were developed based on the therapist-researcher's work experience with children with ASD, corroborated by research studies. These included techniques such as ‘meeting the child where they are at’,20,24 mirroring12,13,25,29 attunement, 30 improvisation, as well as developmental movement or Relationship Play. 9 Importantly, a consistent structure was used across every session to provide a sense of predictability for these children with ASD who might have struggled with changes and the new context of interaction.

This structure involved an upbeat warm-up, a more explorative segment involving mirroring and attuning between parents and children, and lastly a more instructive segment of Relationship Play. 9 Relationship Play, developed by Veronica Sherborne, is a method of working with the two main objectives of helping children develop awareness of self and awareness of others through body movement that is based on normal developmental movement experiences. 9

Additionally, due to the newness of tele-DMP with children with ASD, a groundwork study 19 was conducted by the therapist-researcher, in which dance movement therapists who had used tele-DMP with children and adolescents with ASD were interviewed. These findings informed the interventions in this study too. As an example, difficulty in picking up bodily cues through the screen was mentioned by other therapists and experienced in this pilot study as well. As such, a more directive approach was taken, with the therapist giving instructions and observing whilst also verbally checking in with the parents at the end of each song/exercise/segment to understand better what had happened.

The parents were encouraged to actively participate in sessions and to practise newly learnt skills throughout the week. Alongside this, they were asked to journal their experiences and reflections throughout the week to optimise their learning and engagement.

Assessment and data analyses

This mixed-methods study gathered both qualitative and arts-based data in the form of movement observation. These were analysed accordingly.

Qualitative analysis

Prior to the commencement of the therapy, the parents were invited to online individual, semi-structured interviews. Similarly, at the end of the 6-week programme, parents who had completed the programme were intereviewed. Parents who had dropped out after the first two weeks of therapy were also interviewed to better understand their reasons. All of this qualitative data was analysed using Thematic Analysis (TA), ‘a method for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data’. 31 As the children in this study all had moderate to severe learning disabilities, they were not interviewed due to the potential lack of cognitive capacity. However, their responses to the programme were observed and informed the interventions, from week to week.

The TA used in this study was epistemologically grounded in phenomenology32,33 which focuses on understanding people's everyday experiences of reality in detail, to understand the issue at hand. Using the individual interviews as data items, themes were identified in a ‘bottom up’, inductive, data-driven way, 31 as the openness of this approach was considered suitable for exploring the novel phenomenon of tele-DMP with children with ASD.

Movement observation

Movement observation was based on the Zoom-video recorded sessions. The primary method of observation used to observe specific changes in nonverbal interaction was the Parent Child Movement Scale (PCMS). 34 The PCMS assesses the physical-emotional relationship between parent and child through key parameters such as personal space, self-regulation, movement diversity, synchrony, shared enjoyment, and mutuality. Observations of parent-child dyads engaged in creative processes, such as dance and movement, can reveal specific characteristics of the dyad35,36 which are often unconscious and non-verbal, lending insight into the relationship. 37 The scale also allows observation of the relative contribution of each partner to the relationship. The developers of the scale have validated the scale and proposed it as a tool for measuring the quality of parent-child interactions during as brief an observation as 5 min.

Within the main framework of the PCMS, the therapist-researcher also employed the use of Laban Movement Analysis (LMA 38 ) to consider the movements in more detail. The LMA is a common method of movement observation used in DMP and allows association between movement patterns and psychological characteristics.

In this study, movement observations were done at the start of therapy (Session 1), in the middle (Session 3) and at the end (Session 6). The segment of therapy observed was the segment that was a constant in every session, namely Relationship Play, 9 typically occurring in the last 10–15 min of each session. This was done by the therapist-researcher and by a trainee psychotherapist, independently, with each person writing general notes as well as scoring using the PCMS. Where there were differences in scores, these were discussed to come to a concensus. The general notes were also discussed together. These movement observations were then analysed alongside the results of the qualitative analyses to lend insight into the parents and children's experiences.

Results

Of the five parent-child dyads who signed up, three pairs dropped out following the first two weeks, leaving two pairs who completed the 6-week intervention. Using inductive Thematic Analysis, 31 themes were developed from interview transcripts with parents who had completed the programme as well as those who had dropped out early.

Themes pertaining to the potential benefits of tele-DMP were derived from interviews with the parents of the children who had completed the programme. These were (a) the child's social development, including development of web skills, (b) enjoyment, (c) improved understanding of their child, (d) insight and ideas, and (e) relationship-building. Meanwhile, themes relating to the challenges were (f) the screen-to-screen mode, (g) home as a location for therapy and (h) physical distance. These themes are described in detail below, with one quote illustrating each theme. The full list of quotes for each theme are listed on the left hand side of Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Qualitative and movement analyses highlighting the benefits and challenges of tele-DMP in this context.

| Benefits | |

|---|---|

| Qualitative analysis (TA,31) |

Movement analyses (PCMS,34 with LMA,38) |

Potential benefits

Theme 1: The child's social development

Both parents who completed the programme (E, I) reported development of web skills in their children (F, J). Their reflections touched on their children's interest in the camera, with I depicting the contrast between what she expected and what took place, as well her child's engagement in earlier sessions versus later sessions:

I never thought he’d take much notice of being on camera and he really did … as each session went on, particularly the last two, he was conscious of being on screen, I mean he quite enjoyed being on screen (I)

Besides the development of web skills, it is possible also that her son, J, experienced social development in general. The same interview question was posed before and after the 6-week programme: ‘If you close your eyes now and think of your child's movement, what image/word comes to mind?’ Her responses revealed a change:

Jumping, jumps a lot when he's excited, when he's frustrated, annoyed, upset, when he wants calming … Go to: definitely jumping (I, pre-intervention)

Swaying side to side and rocking backwards and forwards is definitely his go to physical movement, definitely centres him … and he responds when you go in sync with him (I, post-intervention)

This shift in movement can be interpreted through the lenses of two key forms of movement observation in DMP: the Kestenberg Movement Profile (KMP 10 )and LMA. 38 In KMP's Tension Flow Rhythms, jumping is associated with masculine energy (the outer genital rhythm) whilst swaying is associated with feminine energy (the inner genital rhythm). Meanwhile, in LMA's planes of movement, jumping occurs on the Vertical plane and is linked to asserting oneself whilst swaying occurs on the Horizontal plane and relates to relating with others. As such, the observed shift in movement after therapy may suggest social development in the child.

Theme 2: Enjoyment

Both of the parents who completed the programme (E, I) mentioned how their children (F, J) and themselves, enjoyed the programme:

All the movement where we had to go, you know, into each other, on top, underneath, and everything, she was ‘Wow’ (E)

Theme 3: Improved understanding of their child

The parents who completed the programme (E, I) discussed their enhanced understanding of their respective children (F, J) in terms of their feelings, movement behaviours, and preferences. Both parents reported becoming more aware of non-verbal communication:

Sometimes she points, but she doesn’t do it properly, but now I know where to look … And if she wants something, she will point or look at it … Now I understand her more (E)

Therapy also allowed both parents the chance to become acquainted with their children's preferences:

Yeah and actually with eye contact, he probably finds that too intense, like, ‘Why are you staring at me’? You know, whereas with my other children, eye contact is more. I think they’d much rather I look at them when I’m talking to them … (I)

Theme 4: Insight and ideas

Both parents who completed the programme (E, I) also reported gaining insight, which stimulated movement ideas for learning and communication through body language or the body:

Now, during our home refurbishment, I let F touch paint, for example, so she understands ‘No touching’… You don’t just use words, but trying and touching … Trying, touching, you know, showing, repeating (E)

The programme also provided affirmation to one parent who believed that she had already been doing some of what was learnt in therapy without knowing why:

It's nice as a parent to sort of discover you’ve done something instinctively, not necessarily know why you’re doing it but you know it works (I)

Theme 5: Relationship-building

Therapy helped build the parents’ relationships with their children. Both parents who completed the programme (E, I) mentioned that it provided a precious bonding opportunity:

The movement that we do together, into each other, for example. When she's on me and everything, that's getting our relationship stronger (E)

Additionally, one parent, E, revealed that her relationship with her daughter, F, had been boosted due to improved understanding:

Oh, it makes me feel better because before, not being able to understand her, she would get upset, and I would try not to get upset, but I got upset at the end as well … Now when I understand her more, I think the relationship between me and her is getting better … (E)

Challenges

Theme 6: The screen-to-screen mode

Participants mentioned a range of reactions to the screen-to-screen interaction. Besides the positive effects reported by parents who completed the programme (E, I), participants reported that this form of interaction was indeed novel to them and unfamiliar. The parents (E, I) highlighted that both them and their children needed additional time to get used to it:

I remember that first session was really hard because it's like ‘I’m looking at the screen, I can see people I know randomly dancing with me’… I think he found the whole thing really like ‘What is going on?’ (I)

Additionally, engagement with therapy was reported to be challenging as screen-to-screen interaction was not motivating in general, both to children (C, E) and parents (I):

I liked what I saw of the programme but after the first session, we had to drop out. He just does not like being on Zoom. It was hard to engage him (C)

In sum, the screen-to-screen mode of therapy offered new experiences and the potential to develop web skills but it was also challenging for some, affecting participation.

Theme 7: Home

Another issue brought up by the parents was the location of therapy. First, participants viewed the home as being unsuitable for this purpose because home is associated with rest. This may have influenced parents’ attitudes, as noted by parent I, seen in their requests to change the dates and times of therapy, and those of their children's:

It's home for him, you know, he wants to rest and be able to do what he wants (G)

Secondly, scheduling proved to be an issue as well:

… It was difficult waking D up on a Saturday morning … Especially after a long week of home-schooling during lockdown (C)

A third issue with therapy being held at home was distractions and disruptions:

It was hard getting him on Zoom and managing his siblings who were in the same room. They wanted to take part. And even though they knew they could, they felt silly because they thought it was meant for him … (C)

In short, participants’ homes proved to be a challenging environment for therapy for myriad reasons.

Theme 8: Physical distance

Participants reported that the physical distance of each family from the therapist and other families was difficult. The challenges included multitasking and motivating their child. The parents mentioned these in comparison with what they thought therapy in person would have afforded:

Yeah, if he’d seen some of his friends with their families … and we’d done the exercises altogether, he’d be more likely to go away and do it on his own (G)

Both parents who completed therapy (E, I) found that it was difficult to both listen to the therapist and attend to their children at the same time. In particular, it was difficult to hold the attention of their children when the therapist was explaining or demonstrating activities. As such, during the course of the programme, they requested sessions solely for themselves as parents, in order to help them in the sessions with their children. They also requested songs that they knew would engage their children.

Participants (C, E) also said that if the programme were to be conducted in person in the future, they would like to take part (again, in the case of E):

From what I saw, I really liked it. Do let me know if you’re holding studies in the future, I’d love to be involved. It was just really hard this time (C)

In brief, screen-to-screen therapy was challenging for the parents because it required them to multitask and motivate their children without the physical presence and help of the therapist and other members of the group.

Besides qualitative analyses, movement analyses were carried out using The PCMS. 34 Table 3 below lists the scores of the parent-child dyads who completed therapy, namely E and her daughter, F, as well as I and her son, J. The scores range from 1 to 5, with a score of 1 indicating a score in need of improvement, 3 being a medium score, and a score of 5 being ideal. 34 The authors of this scale have provided detailed definitions of each score for each parameter (Table 4).

Table 3.

Parent Child Movement Scale (PCMS) 34 scores of the parent-child dyads who completed therapy.

| Movement observation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCMS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal

space: Closeness and maintaining personal space vs. Distance and penetration |

Self-regulation: Flooding and excitement vs. Organising and planning |

Movement

diversity: Reduction and contraction vs. Expressing creativity and freedom of movement (less relevant due to the instructive nature of the activity during which movement observation occurred) |

Shared

enjoyment: Indifference and dissatisfaction vs. Enjoyment of interaction and playfulness |

Synchronisation: Inconsistency in movement to the partner vs. Adjustment in movement to the partner in form, rhythm, intensity |

Mutuality: Child: ability to move between different roles in a relationship Parent: Ability to adjust to and support the child's needs |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Participant | Participant | Participant | Participant | Participant | Participant | ||||||||||||||||||||

| E | F | I | J | E | F | I | J | E | F | I | J | E | F | I | J | E | F | I | J | E | F | I | J | ||

| Session | #1 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| #3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | |

| #6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

Table 4.

Definitions of each score for each parameter of the Parent Child Movement Scale. 34

| Parameter | Description | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Personal space | Penetration or distance vs. interactions of closeness and touch along with maintaining personal space for movement. | (1) Most of the time the body is upright in the vertical

axis, the space between the moving parent and child does

not allow for contact with an outstretched hand, has

practically no eye contact, contracted muscles and

protective bodily movements (covering and hiding body

parts or turning the head or whole body backwards) or,

most of the time the movement invades the partner's

personal space (the space between the centre of the body

and the hand, with the outstretched hand forward)

suggestive of clinging, invasion, adhesion. (3) Maintaining an adjusted but static and unchanging distance. (5) Adjusted and variable distance between parent and child – allows touch and closeness but also provides personal space for movement. |

| Self-regulation | Flooding and excitement versus organising and planning the movement in relation to the other. | (1) The movements do not match the partner's ability or

are strange, bizarre, very complex, fast, fragmented,

many abrupt changes, or excessive use of movements that

symbolise competition and challenge, movements that

require a great deal of effort and training (standing on

one leg, jumping onto a mattress), or gestures of

intimidation (throwing objects, pretending to sleep,

disappearing). (3) The movements are challenging, unadjusted or unpleasant but there is an awareness of the partner's state or most of the time the movements are adjusted except for one case or a single use of competitive movements. (5) Movements that flow, are varied, develop gradually and are in line with the partner's ability. Most of the time there is a delay to verify whether the movement suggested is suitable for the partner. |

| Movement diversity | Reduction and contraction of the body vs. the ability to express creativity and freedom of movement. | (1) The same movement is repeated again and again.

Movement choice is limited, close to the face or the

body, poor use of space, axial or robotic or

unidirectional movements, clinging to one axis

(vertical, horizontal or sagittal), or dropping the body

(like a rag doll) or movement only at the extremities of

the body (hands without the use of a torso), or many

halts in movement (e.g., due to crying, laughing, or

talking for more than a few moments, turning to a

therapist, engaging in objects unrelated to the joint

movement). (3) Sometimes there is varied movement, but it is limited, most of the time the movement is small or, the movement stops but only once. (5) Varied, creative movements, involving different body parts, rounded movements (the inner core takes part and some joints are involved). The whole body participates, without long pauses. There are attempts to develop the movement. |

| Shared enjoyment | Indifference and dissatisfaction vs. the enjoyment of interaction and playfulness. | (1) There is no playfulness, the movement is random,

does not evolve and does not develop into enjoyment, a

flat/apathetic/tension affect can be seen and the mover

is not connected to what s/he is doing, as though

activated (like a puppet on a string). Conveys

unhappiness, hostility, tension, anger, sadness,

impatience, desire to run away. (3) Flashes of movements with a quality of sharing and enjoyment, but in general the playfulness is shallow, the laughter and emotional arousal poor or, the beginning is tense and then there is a partial release. (5) Playfulness, enjoyment, calmness, relaxation and motivation for a shared experience, accompanied by laughter, smiles, manifestations of satisfaction, and a fun, pleasant emotional arousal. |

| Synchronisation | Inconsistency in movement to the partner vs. adjustment in the movement to the partner in form, rhythm and intensity | (1) Inability to track the partner's movements over

time. Inconsistency in the rhythm or intensity of

movement. Need for a lot of outside mediation from the

therapist. (3) Limited ability to track the partner's movements and move accordingly. (5) Accurate and tailored monitoring of partner movements over time. The onlooker has a sense of joint movement. |

| Mutuality | Child's Score: Ability to move between different roles in a relationship | (1) Without transitions between the leading role and the

follower role. (3) Needs considerable intervention from the therapist or the mother to move in one of the roles. (5) The child moves between the leading role and the follower role. |

| Mutuality | Mother's score: The ability to adjust to and support the child's needs | (1) The mother is constantly leading, does not allow the

child to lead, or the mother does not lead at all. In

leadership there is no dialogue, negotiation, more akin

to individual performance, at times, a sense of

helplessness, takeover, ignoring the child, or the

mother is self-centred, detached. The movements that the

mother suggests are completely different from the

movements of the child. (3) Most of the time the partner is only in one role (leading the child or led by the child) and in a small proportion of the time s/he moves to the other role. (5) There is a delay and verification to determine if the child is able to follow the movements of the mother or if child wants to suggest a personal movement. The mother leads the movement while referring to the child's movements and abilities. The mothers increase or decrease their movements. The mothers’ movements are adapted in complexity and speed to the children's abilities |

1. The score for shared enjoyment was the same for mother and child and stems from the shared experience.

2. The definition of mutuality differs between parent and child.

Table 3 shows that the two parent-child dyads (E and her daughter, F; I and her son, J) started out with noticeably different PCMS 34 scores in Session 1, with E and F already reaching high scores from Session 1, whilst I and J struggled in several domains. There was an overall trend toward improvement by Session 6 with E and F maintaining their high scores and parent I improving in the parameters of Personal Space, Self-Regulation, Shared Enjoyment, and Mutuality. Meanwhile, her son, J, improved noticeably in the parameters of Self-Regulation and Mutuality, and to a lesser extent, in Shared Enjoyment and Synchronisation.

Based on the PCMS 34 scores in Tables 3, Table 2 outlines the benefits and challenges of tele-DMP in this study, listing the themes discovered through qualitative analyses alongside movement analyses linking movements to possible psychological development. Within the PCMS framework, LMA 38 was used, where relevant, to consider the details of the movements.

Discussion

Consistent with previous reviews of DMP and ASD,12,14 tele-DMP also facilitated social development for the children in this study. This was seen in face-to-face interactions as well as screen-to-screen. As with a recent study 18 on tele-DMP and neurotypical children during the lockdown, the children with ASD in this study developed web skills in interacting from a distance, to the surprise of their parents. In this sense, it may be worthwhile for parents to offer their children with ASD the chance to take part in interactions that are not face-to-face. Face-to-face encounters often entail a multi-sensorial experience and an element of uncertainty within close physical proximity of the child. Hence, unconventional methods of communication, such as tele-DMP, may have distinct advantages, given the core differences defining autism and common sensory sensitivities.

This online delivery, the DMP programme, and the physical parent-child interaction may each have contributed to the enjoyment reported by the participants. Apart from its intrinsic value, enjoyment has previously been cited as an important concept as it determines activity participation in children with ASD. 39 This small-scale study may indicate that tele-DMP, just like DMP in person, can facilitate enjoyment, engagement, and development in children with ASD, highlighting the value of a strengths-based approach. Additionally, the quality of non-verbal interactions between parents and children with emotional and behavioural difficulties influences the motor arousal of their children.40,41 As such, enjoyable non-verbal interactions may have a role to play in the regulation processes of children with ASD, who may be susceptible to emotional and behavioural difficulties.

The parents in this study also reported improved understanding of their child's feelings, movement behaviours, and preferences, leading to insight and ideas for communicating and learning through body and body language. These benefits partially resonate with previous literature on family-centred practices which have highlighted outcomes such as the development of early social communication skills in children with ASD40,41; improved parent self-efficacy, leading to child development 42 ; and family progress and competence in families with children at risk of ASD. 43 However, the unique contribution of family-centred DMP, which had not been studied prior to this, may be seen in the body and movement-based understanding and communication between parent and child. Taken together, the benefits of this programme may have helped build the parent-child relationship, an outcome reported by the parents as well.

Nonetheless, there were indeed challenges that affected participation. Parents in this study reported that the screen-to-screen interactions were unfamiliar and unmotivating both to them and their children. Due to the nature of autism, which can include restricted behaviours and very often sensory sensitivities as well, the impact of unfamiliarity cannot be discounted. This might have been different if the children had already worked with and built a rapport with the therapist prior to going online. Motivation to interact on the screen could also have been impacted by the pandemic and national lockdown in the United Kingdom at the time of the study. Working and studying from home could have contributed to varying degrees of screen fatigue.

Even without the pandemic, home is often associated with rest and represents a free environment that may not be conducive to participation in therapy. As mentioned in a study on telehealth-based creative arts therapy, ‘the increased comfort can lead a participant to behave in ways that he or she would not if seated in a therapist's office’. 44 These attitudes might have been reflected in the participants’ requests and scheduling difficulties. Likewise, a previous qualitative study on teletherapy with individuals with ASD found that scheduling was an issue. 17 Additionally, as seen in this study, family members staying at home and sharing the same space and resources in lockdown sometimes led to distractions and disruptions in therapy. This would also affect the level of privacy and personal disclosure or engagement, as noted in the abovementioned study on telehealth-based creative art therapy. 44

These findings on the home environment being less suited for therapy may speak to the importance of having a separate therapeutic setting as a holding environment 45 to contain the process of therapy and the feelings of the clients. The holding environment is a psychodynamic term referring to how a parent allows their child to express emotion whilst keeping them safe, and how therapists can create this environment for their clients too. They also echo the findings in a groundwork study by the authors 19 in which the lack of a separate therapeutic space was cited, by various dance movement therapists, as an issue in tele-DMP with children and adolescents with ASD.

The same groundwork study by the authors also found that physical distance was an issue. This was echoed by the parents in this study, lending a different perspective to the same phenomenon. Without the holding environment 45 provided by the physical presence of the therapist, as well as other peers in the room, parents felt that they had to invest more effort into engaging and motivating their children.

Another concern voiced by a parent was that the child moving outside of the camera frame made it difficult for the therapist to view what was going on. This may indeed pose a challenge for dance movement therapists, who rely on their observation of their clients’ body movements for assessment and intervention. As noted in a case study 44 on tele-DMP with a veteran in the United States, difficulties in viewing the whole body must be accommodated. These difficulties were also present in this study with children with ASD.

Previous literature has suggested that delivering interventions requiring physical support is a barrier in teletherapy with individuals with ASD. 17 In this study on tele-DMP and ASD, it was found that besides interventions requiring physical support, even those requiring physical presence may not translate as well in teletherapy. This may highlight the unique benefits of simply meeting in person. In contrast to the findings of a systematic review 16 which reported that telehealth interventions are very acceptable and comparable to face-to-face interventions, this study on tele-DMP highlighted the differences between screen-to-screen and face-to-face interventions.

To an extent, the parents were able to attenuate this difficulty by voicing out their concerns to the therapist and making suggestions, such as having extra sessions solely for the parents and song choices for their children. Similarly, previous literature has highlighted how families consider collaboration to be key in teletherapy with individuals with ASD. 17

Should tele-DMP be used in this context, some recommendations can be made based on these challenges. First, additional sessions can be allotted to help children with ASD acclimatise to interacting online. At the same time, the effect of the pandemic on the participants’ relationship to the screen, e.g., screen fatigue, should be considered. Where possible, the therapeutic relationship should be built in person first so that the therapist is a familiar figure to the child.

Secondly, parents can be reminded to set a separate room for teletherapy, where possible, for a more conducive holding environment 45 and to arrange separate activities for other members of the family who are not participating, to avoid disruptions. In addition, to mentally prepare children with ASD for this home-based activity, visual aids such as symbols, weekly calendars, or social stories can be made.

Lastly, as requested by the parents in this study, short, extra sessions can be organised solely for the parents to help them acquaint themselves with meeting online, the structure of the sessions, and to first experience the therapeutic work themselves. In addition, assessments of the parents’ intuitive and trained ability to engage with the activities and to help their children may be useful as well. Therapists can consider shortening the duration of online sessions in cases where the physical distance from the therapist and peers may be less motivating to the child, to lessen the burden on the parents.

These suggestions could optimise the engagement of children with ASD in tele-DMP. In addition, more targeted admission criteria could help reduce the attrition rate. This can be done by pre-screening and admitting parents and children who are able and willing to engage with the screen, perhaps based on their previous experiences of screen engagement. Usability assessments can also be employed to verify the parents’ ability to use the technological tools needed to engage in the intervention effectively.

Limitations

The limitations of this feasibility study include the small sample size, which limits the generalisability of the findings. Furthermore, the inferences drawn about the effects of the intervention must be read bearing in mind the sample loss that occurred during the course of the intervention. Also, the pandemic may have been a confounding factor due to its impact on participants’ behaviours and surroundings. Additionally, the participants were not always visible in the frame of the camera, reducing the opportunities for intervention or observation by the therapist-researcher. Lastly, it should be noted that engagement might have been different had there been a therapeutic relationship in person prior to therapy taking place online.

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that tele-DMP for children with ASD can be beneficial and offer distinct advantages. However, it may be challenging due to the mode of participation. Tele-DMP can be helpful as an interim or adjunct measure when meeting physically is challenging, for example, during times when social distancing has to be observed or participants may not be able to attend therapy in person due to geographical factors or disability. Measures can be taken to optimise the engagement of children with ASD in tele-DMP. Additionally, admission criteria may need to be more stringent to filter participants based on their ability and willingness to engage in screen-to-screen interactions. Meanwhile, the positive outcomes from the intervention may point to the advantages of family-centred DMP with children with ASD, which itself has yet to be studied. This bears implications for practice and research.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the families who took part in this research as well as the school involved for their help in recruiting the participants, The Grove School in North London. We are also grateful to Giorgio Senigagliesi for his help with movement analyses.

Footnotes

Contributorship: Janet TN Moo researched literature, carried out therapy, data collection, data analysis and wrote up the study. Rainbow TH Ho supervised the study from conception. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: The Human Research Ethics Committee of the author's institute (removed for anonymity purposes) approved this study.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Informed, written consent was obtained from parents.

ORCID iD: Janet TN Moo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0537-2351

Supplemental materials: Underlying research materials in the form of qualitative data analysis can be accessed by emailing the authors.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor B, Jick H, MacLaughlin D. Prevalence and incidence rates of autism in the UK: Time trend from 2004–2010 in children aged 8 years. BMJ Open. 2013; 3: e003219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McConkey R. The rise in the number of pupils identified by schools with autism spectrum disorders (ASD): A comparison of the four countries in the United Kingdom. Support Learn 2020; 35: 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS Digital. Estimating the prevalence of autism spectrum conditions in adults: Extending the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Report, National Health Service, UK, January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Autism Spectrum Disorder in under 19s: Recognition, referral, and diagnosis. Clinical guideline (CG128), 20 Dec 2017. [PubMed]

- 6.Association of Dance Movement Psychotherapy UK. What is Dance Movement Psychotherapy? https://admp.org.uk/dance-movement-psychotherapy/what-is-dance-movement-psychotherapy/(2022, accessed 1 August 2022)

- 7.Birdwhistell RL. Introduction to kinesics: (An annotation system for analysis of body motion and gesture) .Washington DC: Department of State, Foreign Service Institute, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird Get al. et al. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018; 392: 508–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherborne V. Developmental movement for children .2nd ed. London: Worth Publishing, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kestenberg Amighi J, Loman S, Lewis P, et al. The meaning of movement .New York: Brunner Routledge, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Mental health problems in people with learning disabilities: Prevention, assessment and management. NICE guideline (NG54), 14 September 2016. [PubMed]

- 12.Scharoun SM, Reinders NJ, Bryden PJ, et al. Dance/movement therapy as an intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Dance Ther 2014; 36: 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi H, Matsushima K, Kato T. The effectiveness of dance/movement therapy interventions for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Am J Dance Ther 2019; 41: 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aithal S, Moula Z, Karkou V, et al. A systematic review of the contribution of dance movement psychotherapy towards the well-being of children with autism spectrum disorders. Front Psychol 2021; 12: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutherland R, Trembath D, Roberts J. Telehealth and autism: A systematic search and review of the literature. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 2018; 20: 324–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Nocker YL, Toolan CK. Using telehealth to provide interventions for children with ASD: A systematic review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 2021; 10: 82–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson G, Kerslake R, Crook S. Delivering allied health services to regional and remote participants on the autism spectrum via video-conferencing technology: Lessons learned. Rural Remote Health 2019; 19: 5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Re M. Isolated systems towards a dancing constellation: Coping with the COVID-19 lockdown through a pilot dance movement therapy tele-intervention. Body Mov Dance Psychother 2021; 16: 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moo JTN, Ho RTH. (forthcoming 2024). Adapting to COVID-19: Telehealth dance movement psychotherapy with children and adolescents with autism. In Aithal S and Karkou V (eds) Arts therapies research and practice with persons on the autism spectrum: Colourful hatchling. Chapter 11. Routledge.

- 20.Baudino LM. Autism spectrum disorder: A case of misdiagnosis. Am J Dance Ther 2010; 32: 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devereaux C. Educator perceptions of dance/movement therapy in the special education classroom. Body Mov Dance Psychother 2017; 12: 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Partelli D. Aesthetic listening: Contributions of dance/movement therapy to the psychic understanding of motor stereotypes and distortions in autism and psychosis in childhood and adolescence. Arts Psychother 1995; 22: 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samaritter R, Payne H. Through the kinaesthetic lens: Observation of social attunement in autism spectrum disorders. Behav Sci 2017; 7: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torrance J. Autism, aggression, and developing a therapeutic contract. Am J Dance Ther 2003; 25: 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erfer T. Treating children with autism in a public school system. In Levy F. (ed.) Dance and other expressive therapies. When words are not enough. New York: Routledge, 1995, pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoop T. (with Mitchell P). Won’t you join the dance? Palo Alto, CA: National Press Books, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheets-Johnstone M. Why is movement therapeutic? Am J Dance Ther 2010; 32: 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tortora S. The dancing dialogue: Using the communicative power of movement with young children .Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winters AF. Emotion, embodiment, and mirror neurons in dance/movement therapy: A connection across disciplines. Am J Dance Ther 2008; 30: 84–105. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stern DN. The interpersonal world of the infant: A view from psychoanalysis & developmental psychology .New York: Basic Books, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research .London: Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith JA, Osborn M. Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. 2nd ed. London: Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shuper-Engelhard E, Moshe S, Kedem Det al. et al. The parent–child movement scale (PCMS): Observing emotional facets of mother–child relationships through joint dance. Arts Psychother 2021; 76: 101843. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gavron T. Meeting on common ground: Assessing parent-child relationships through the Joint Painting Procedure. Art Ther Am J Art Ther 2013; 30: 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proulx L. Strengthening emotional ties through parent-child-dyad art therapy: Interventions with infants and preschoolers. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavron T, Mayseless O. Creating art together as a transformative process in parent-child relations: The therapeutic aspects of the joint painting procedure. Front Psychol 2018; 9: 2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laban R, Lawrence FC.Effort. London: MacDonald and Evans, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eversole M, Collins D, Karmarkar A, et al. Leisure activity enjoyment of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2016; 46: 10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller-Slough RL, Dunsmore JC, Ollendick THet al. et al. Parent–child synchrony in children with oppositional defiant disorder: Associations with treatment outcomes. J Child Fam Stud 2016; 25: 1880–1888. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts JMA, Prior MA. A review of the research to identify the most effective models of practice in early intervention of children with autism spectrum disorders. Report, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, Hanby DW. Meta-analysis of family-centred helpgiving practices research. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Rev Res 2007; 13: 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coogle CG, Hanline MF. An exploratory study of family-centred help-giving practices in early intervention: Families of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Fam Soc Work 2016; 21: 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy CE, Spooner H, Lee JBet al. et al. Telehealth-based creative arts therapy: Transforming mental health and rehabilitation care for rural veterans. Arts Psychother 2018; 57: 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winnicott D. Playing and reality .London: Routledge, 1971. [Google Scholar]