Abstract

Morphine withdrawal evokes neuronal apoptosis through mechanisms that are still under investigation. We have previously shown that morphine withdrawal increases the levels of pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a proneurotrophin that promotes neuronal apoptosis through the binding and activation of the pan-neurotrophin receptor p75 (p75NTR). In this work, we sought to examine whether morphine withdrawal increases p75NTR-driven signaling events. We employed a repeated morphine treatment-withdrawal paradigm in order to investigate biochemical and histological indicators of p75NTR-mediated neuronal apoptosis in mice. We found that repeated cycles of spontaneous morphine withdrawal promote an accumulation of p75NTR in hippocampal synapses. At the same time, TrkB, the receptor that is crucial for BDNF-mediated synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus, was decreased, suggesting that withdrawal alters the neurotrophin receptor environment to favor synaptic remodeling and apoptosis. Indeed, we observed evidence of neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampus, including activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and increased active caspase-3. These effects were not seen in saline or morphine-treated mice which had not undergone withdrawal. To determine whether p75NTR was necessary in promoting these outcomes, we repeated these experiments in p75NTR heterozygous mice. The lack of one p75NTR allele was sufficient to prevent the increases in phosphorylated JNK and active caspase-3. Our results suggest that p75NTR participates in the neurotoxic and proinflammatory state evoked by morphine withdrawal. Because p75NTR activation negatively influences synaptic repair and promotes cell death, preventing opioid withdrawal is crucial for reducing neurotoxic mechanisms accompanying opioid use disorders.

Keywords: caspase-3, glutamate receptors, JNK, opioid use disorders, p75NTR, TrkB

Introduction

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is characterized by negative emotional states, as well as cognitive and learning deficits in both children exposed to opioids in utero (Yeoh et al. 2019) and adults (Gruber et al. 2007, Schmidt et al. 2017, Kroll et al. 2018). Human and animal studies have shown that opioid abuse promotes abnormal gray matter volume (Younger et al. 2011), neuronal apoptosis (Hu et al. 2002a, Mao et al. 2002, Bajic et al. 2013, Tramullas et al. 2007), oxidative stress (Abdel-Zaher et al. 2013) and overall changes in neural plasticity (Welsch et al. 2020). In addition, heroin dependence appears to alter the functional connectivity strength between brain networks responsible for cognitive control (Zhai et al. 2015). The hippocampus has been considered a key brain area for cognitive and social behavior (Nadel et al. 2013, Rubin et al. 2014, Anacker & Hen 2017). Remarkably, loss of cognitive function and synaptic remodeling observed in OUD occur despite the increased expression of the brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus of animals (Rouhani et al. 2019, Alvandi et al. 2017) or in human serum (Heberlein et al. 2011). Thus, the molecular mechanisms whereby opioid abuse reduces cognitive abilities remain to be fully understood.

Opioid abusers frequently undergo cycles of withdrawal. Opiate withdrawal has been shown to decrease the number and complexity of dendritic spines in brain reward circuitry neurons including the ventral tegmental area (Russo et al. 2009, Spiga et al. 2003), and enhance long-term depression (LTD) in the hippocampus (Han et al. 2015). Moreover, repeated opioid withdrawal impairs cognition and promotes neuronal apoptosis (Tramullas et al. 2007). However, despite numerous animal and human studies, much less is known about how opioid withdrawal reduces cognition and decision-making tasks. We have previously shown that morphine withdrawal reduces the enzymatic processing of pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), leading to a decrease in the availability of mature BDNF (Bachis et al. 2017). Unprocessed extracellular proBDNF can lead to activation of the pan neurotrophin receptor p75NTR (Hempstead 2002). This receptor and its signaling pathways, including the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the Ras homolog family member A (RhoA) pathways (Bhakar et al. 2003, Kaplan & Miller 2000, Yamashita et al. 1999), promote cell death (Yoon et al. 1998, Friedman 2000), axonal collapse and degeneration (Park et al. 2010, Yamashita & Tohyama 2003), synaptic simplification (Teng et al. 2005), and facilitate LTD (Woo et al. 2005). Moreover, lack of or reduced mature BDNF has been suggested to be one of the causes of the neuropathology observed in various neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s (Howells et al. 2000, Toda et al. 2003), Huntington’s disease (Ciammola et al. 2007), and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) (Bachis et al. 2012). Thus, morphine withdrawal may induce neuronal apoptosis and synaptic simplification by a mechanism that is p75NTR related.

The goal of this study was to explore novel mechanisms that could explain the negative impact on cognitive tasks observed in heroin abusers (Guerra et al. 1987, Papageorgiou et al. 2004). We sought to provide conclusive evidence that p75NTR is one of the key mechanisms underlying the ability of morphine withdrawal to induce neuronal apoptosis. We found that morphine withdrawal but not chronic morphine increases p75NTR in synaptosomes from the hippocampus, concomitantly with an increase in phosphorylated JNK and active caspase-3. All these changes were prevented in p75NTR+/− mice. Altogether, we provide novel evidence that morphine withdrawal, through p75NTR, activates a key downstream signaling pathway that leads to the initiation and advance of neuronal apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

Morphine sulfate was received from the National Institutes of Drug Abuse (National Institute of Health, Division of Neuroscience & Behavioral Research, Research Triangle Park, NC). Morphine was diluted in saline and then sterilized by filtration. All other chemicals were commercially obtained.

Animals.

Male mice on the C57BL/6N genetic background (n=52) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Frederick, MD) and maintained in the Division of Comparative Medicine’s Research Resource Facility at Georgetown University Medical Center. Mice p75NTR−/− on the C57BL/6N background were obtained from Dr. Lino Tessarollo at National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD) and crossed in our vivarium for at least 5 generations with wild type (WT) littermates. These mice have a targeted mutation of the p75NTR allele in which the extracellular ligand-binding domain (exon III) is knocked out (Lee et al. 1992). For our study we used p75NTR+/− (heterozygous) male mice (n=32). All studies were initiated once the animals reached 14 weeks of age (18–24 gr). Only males were used because we did not obtain enough p75NTR−/− or p75NTR+/− females to conduct the experiments. Otherwise, no animals were excluded before initiating the experiments and no exclusion criteria were pre-determined. All animals were weighed once daily just prior to subcutaneous (s.c.) injections of morphine or saline and at each additional injection during the withdrawal cycle. Experimenters and veterinary staff examined animals each day for outward signs of extreme distress that would require euthanasia to minimize animal suffering, but no mouse in the study met these criteria. Over the course of the study, all animals had ad libitum access to water and food (Purina Chow, cat.no. 5001, Purina Co.) and were housed three to four per cage in Lab Products SuperMouse 750 Ventilated Cages (Lab Products Inc., Seaford, DE). Mice were anesthetized with a single intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (cat.no. 5700864, Akorn Inc., Lake forest, IL) and xylazine (cat.no. 59399-110-20, Akorn Inc.) solution (80/10 mg/kg) and euthanized by intracardially perfused with ice-cold phosphate buffer saline (PBS). We elected to use a ketamine/xylazine cocktail due to its very swift onset of action and minimal acute stress which would otherwise interfere with our endpoints.

For biochemistry, the hippocampus was dissected on ice and snap frozen until homogenization. For immunohistochemistry, the whole brain was removed and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, and then transferred to 30% sucrose in PBS for at least 48 hr. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Georgetown University Medical Center (protocol no. 2018–1189).

Animal treatments.

No randomization method was used to allocate the animals in the study. All animals in a single cage were assigned arbitrarily to experimental or control groups. For the timeline outlining the experimental design and the animal groups see Figure 1. Mice received s.c. injections of either saline (n=13 WT; n=8 p75NTR+/−) or escalating doses of morphine (n=13 WT; n=8 p75NTR+/−), starting from 10 mg/kg and ending with 50 mg/kg, two times per day (8 AM and 8 PM) over the course of five days (Table 1). The injection site was alternated between the loose skin of the neck and either flank. Mice were euthanized (see above) 2 hr after the last injection. A group of mice received escalating doses of morphine (n=13 WT; n=8 p75NTR+/−) and were then allowed to undergo spontaneous withdrawal for 72 hr (Table 1). They then received a single injection of morphine (50 mg/kg) and allowed again to undergo spontaneous withdrawal for another 72 hr. The single injection treatment every 72 hr was repeated three times (Table 1). Control mice received saline (n=13 WT; n=8 p75NTR+/−) at the same times and frequency of morphine. All animals were euthanized (see above) 72 hr after the last morphine or saline injection. All analyses were conducted by experimenters blinded to treatment groups.

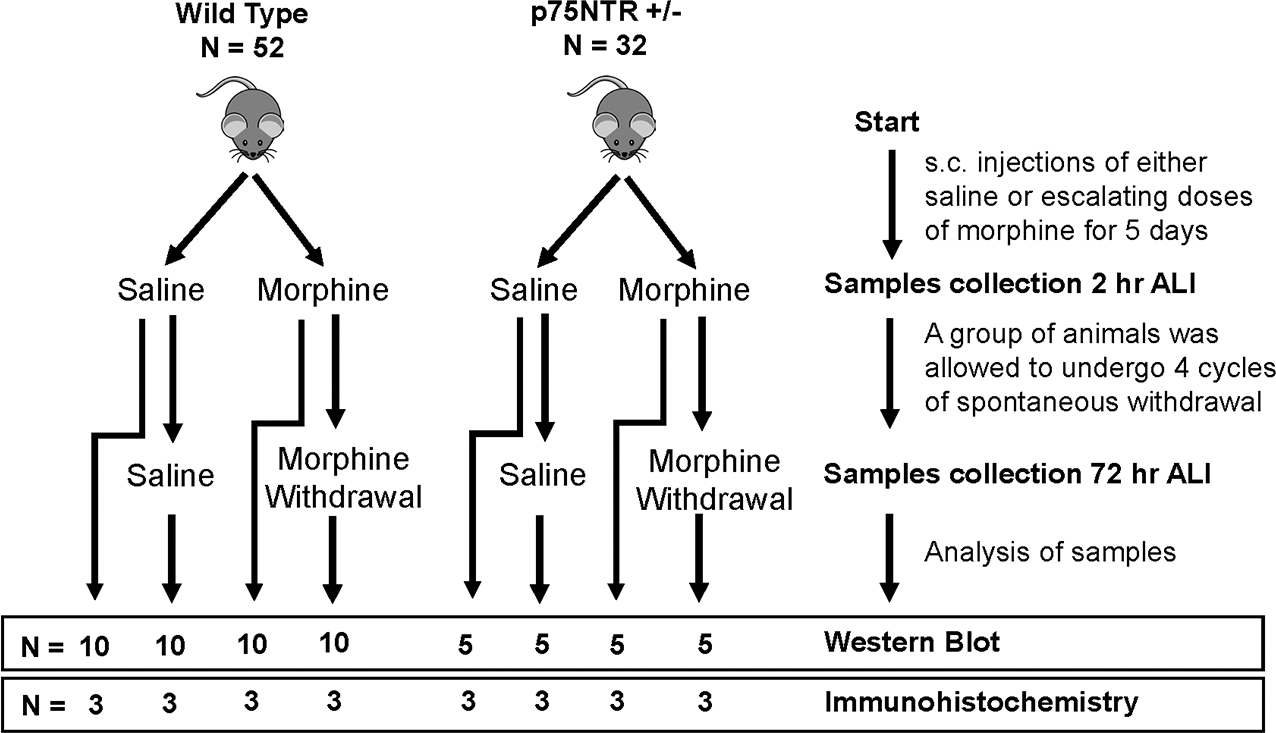

Figure 1.

Timeline outlining experimental design and animal groups. ALI = after last injection. N = number of animals used.

Table 1.

Morphine treatment paradigms. Saline or morphine was administered subcutaneously every 12 hr for 5 days. Chronic morphine = Mice were euthanized (eut) at the fifth day of the treatment, 2 hr after the last injection. Morphine withdrawal = After the last injection of morphine on the fifth day, animals were allowed to undergo spontaneous withdrawal for 72 hr and then received 50 mg/kg of morphine (day 8), followed by spontaneous withdrawal for 72 hr. These cycles of morphine treatment and withdrawal were repeated twice (days 11 and 14). Animals were euthanized (eut) 72 hr after the last injection (day 17). NT = no treatment.

| Paradigm | Day 1 mg/kg |

Day 2 mg/kg |

Day 3 mg/kg |

Day 4 mg/kg |

Day 5 mg/kg |

Day 8 mg/kg |

Day 11 mg/kg |

Day 14 mg/kg |

Day 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic morphine | 8 AM | 10 | 10 | 30 | 50 | 50 (eut 2 hr) | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| 8 PM | 10 | 30 | 30 | 50 | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| Morphine withdrawal | 8 AM | 10 | 10 | 30 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | eut 72 hr |

| 8 PM | 10 | 30 | 30 | 50 | NT | NT | NT | NT | ** |

Hot Plate Assay.

We adapted a protocol from Balter and colleagues in order to measure the degree of thermal sensitivity in our mice throughout our morphine injection schedule (Balter & Dykstra 2012). Mice were tested at the start of their light-dark schedule inside the room in which they were housed to minimize the effect of diurnal corticosterone cycles and anxiety on thermal sensitivity. Briefly, each rodent was exposed to a hot plate analgesia meter (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) set at 52 or 54 °C. An experimenter placed each rodent on the heated surface and recorded the latency (to the nearest 0.1s) for the mouse to display one of three behaviors indicating sensitivity to heat: jumping, licking of the paws, or hind paw flutters. The mouse was then immediately removed from the chamber and allowed to rest in its home cage. To prevent damage to the paws, if the animal did not display these behaviors in the first twenty seconds on the hot plate, the trial was ended and the latency was recorded as 20.0 seconds. Each mouse was exposed once to each of the temperatures in ascending order and each trial was spaced 15 minutes from the previous trial. On days in which the animal underwent morphine or saline injections, the hot plate assay was performed an average of 90 minutes after treatment. Due to the very robust Straub effect and clinical signs of withdrawal encountered with morphine exposure in rodents, we were unable to conduct the behavioral portion of the analyses in a true blinded manner.

Preparation of synaptosomes and Western blot analysis.

Synaptosomes were prepared from hippocampal tissue (n=5 mice per group) using Syn-PER Synaptic Protein Extraction Reagent (cat.no. 87793, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To obtain the whole lysate of proteins, the hippocampal tissue (n=5 mice per group) was homogenized in RIPA buffer (cat.no. 20–188, Millipore) containing Halt protease-phosphatase inhibitors (cat.no. 78442, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein content was determined by BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit (cat.no. 23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Proteins were separated in a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (cat.no. NP0335, Invitrogen) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (cat.no. 1620117, Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in PBS and 0.1% Tween-20 and probed with antibodies against: p75NTR (2μg/ml, cat.no. AF1157, RRID:AB_2298561, R&D Systems), TrkB (1:1000, cat.no. 07–225, RRID:AB_310445, Millipore), p-JNK1/2/3 (1:1000, cat.no. ab76572, RRID:AB_1523840, Abcam), JNK1/2/3 (1:1000, cat.no. ab179461, RRID:AB_2744672, Abcam), active caspase-3 (1:500, cat.no. C8487, RRID:AB_476884, Sigma-Aldrich), NMDA receptor subunit 2B (NR2B, 1:1000, cat.no. ab65783, RRID:AB_1658870, Abcam), AMPA receptor (GluA2/3/4, 1:1000, cat.no. 2460S, RRID:AB_823507, Cell Signaling Technology) and β-actin (1:15000, cat.no. A1978, RRID:AB_476692, Sigma-Aldrich). The levels of β-actin were used as a loading control. Immune complexes were detected by the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody using enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (cat.no. 32106, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The intensity of immunoreactive bands was quantified using ImageJ and expressed as a percentage of the corresponding saline control group after normalization with β-actin.

Immunohistochemistry.

Fixed brains (n=3 per group) were sectioned at 30μm by a sliding microtome (Microm International). Free-floating hippocampal sections (n=3 per animal) were blocked in a blocking buffer (2% bovine serum albumine, 10% normal donkey serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 2 hr and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: p75NTR (5μg/mL, cat.no. AF1157, RRID:AB_2298561, R&D Systems), neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN, 1:1000, cat.no. ab104225, RRID:AB_10711153, Abcam), active caspase-3 (1:1000, cat.no. C8487, RRID:AB_476884, Sigma-Aldrich), glial-fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:10000, cat.no. Z0334, RRID:AB_10013382, Dako). After washing, the sections were incubated with the corresponding secondary fluorescent antibodies (1:2000, Alexa Fluor, Invitrogen) and analyzed using a Leica SP8 Confocal microscope. Sections were also stained with Fluoro-Jade C (cat.no. TR-100-FJ, Biosensis Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All images (n=2 fields per section) were acquired with identical parameters using a Leica SP8 Confocal microscope. Three-dimensional (3D) Z-stack images were obtained using the Z drive. For each field 33 section were captured with an interval of 0.6 μm, and then stacked together using the tile scan feature. Data analyses were performed using the freeware ImageJ software (National Institute of Health). Briefly, each image was analyzed by either measuring the mean gray values to obtain the intensity of fluorescence or by counting the number of positive cells, in selected fields, using identical parameters.

Graphical abstract.

The graphical abstract was created with Biorender (http://www.biorender.com).

Statistical analysis.

The study was not pre-registered and no sample calculation or power analysis was performed. However, an adequate group size was inferred for these experiments based on previous animal studies in our lab with related endpoints. Data were analyzed via either one-way or two-way ANOVA. Tukey’s honestly significant difference was used as a post-hoc measure for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis and figure generation were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). We conducted Shapiro-Wilk normality test on our data sets before proceeding with parametric measures. We elected to use a ROUT analysis with a Q of 5% to identify outliers in our data, but no data points were excluded post-hoc. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM or mean ± SD. A p value of <0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Results

Morphine withdrawal alters the levels p75NTR and TrkB in synaptosomes.

Morphine withdrawal alters the ratio of proBDNF/mature BDNF in the rat brain (Bachis et al. 2017). Therefore, we examined whether chronic morphine treatment or withdrawal also changes the levels of p75NTR and TrkB, the cognate high-affinity receptors for proBDNF and mature BDNF, respectively. Mice received escalating doses of morphine for five days (CM) or saline (SAL 5d) (Fig. 1). No signs of withdrawal were observed in these animals. Another group received escalating doses of morphine and were allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal for 72 hr (WD 72h) prior to the euthanasia as described in Table 1. Control mice received saline (SAL 72h). We found no difference between SAL 5d and SAL 72h; therefore, in this study, these two groups are presented in the figures as SAL. Withdrawal was assessed by examining several signs, including piloerection, wet dog shakes, vocalizations, and anxiety to experimenter contact (data not shown). None of these signs were present in saline-treated animals (data not shown). Because p75NTR and TrkB are mostly synaptic receptors, the levels of p75NTR and TrkB were determined in synaptosomes from the hippocampus of all four groups of animals by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). We observed that while CM did not change the levels of p75NTR when compared to SAL control, WD 72h animals showed a significant increase in the levels of p75NTR when compared to either SAL or CM (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 7.56; p = 0.0075) (Fig. 2B). The opposite was observed for TrkB. Indeed, mice undergoing withdrawal show a statistically significant reduction in the levels of TrkB immunoreactivity, both full-length isoform (TrkB-FL) (Figs. 2a and C) and truncated (TrkB-T1, Fig. 2A), when compared to either SAL or CM. (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 9.19; p = 0.0038).

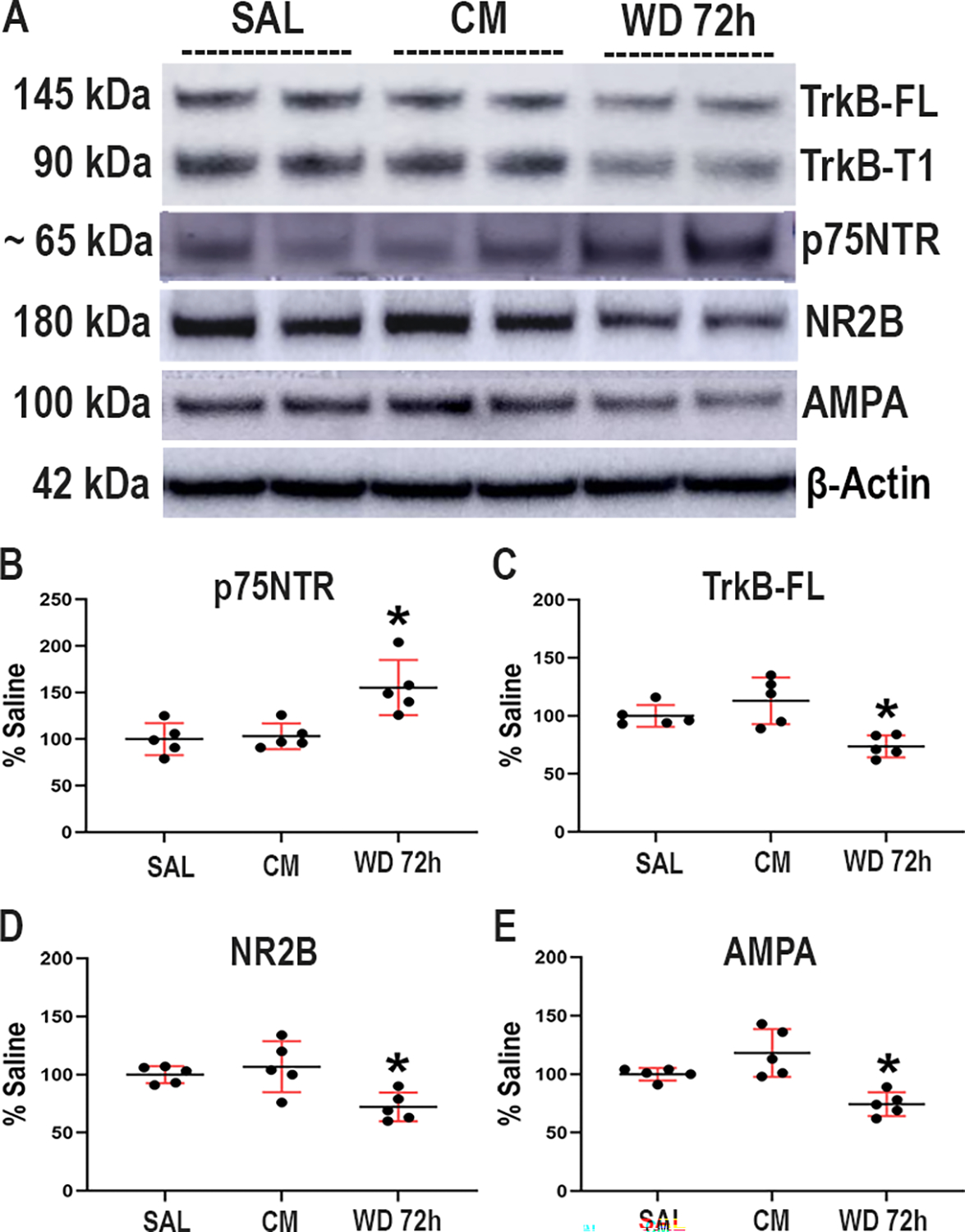

Figure 2.

Morphine withdrawal changes the ratio p75NTR/TrkB in wild type mice. Mice were injected subcutaneously with saline (SAL) or escalating doses of morphine (CM) for 5 days and euthanized 2 hr after the last injection. Another group of animals was allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal and euthanized 72 hr after the last injection (WD 72h) as described in Table 1. A. Representative blot showing the hippocampal levels of TrkB-FL, TrkB-T1, p75NTR, NR2B and AMPA (GluR2–4) subunits. Every band in the blot represents a different sample. B-E. Densitometric analysis expressed as percentage of saline after normalization with β-actin. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of 5 animals per group. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD. * p < 0.05 vs saline.

To investigate whether the effect of withdrawal on p75NTR and TrkB is unique for these receptors, we measured the levels of the synaptic markers NR2B and AMPA GluR2–4 by Western blot. We observed that withdrawal elicits a significant reduction (Figs. 2A, D and E) in the levels of NR2B (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 7.34; p = 0.0083), and GluR2–4 (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 13.29; p = 0.0009). These data suggest that the decrease in TrkB levels elicited by morphine withdrawal could be due to synaptic remodeling.

Morphine withdrawal up-regulates p75NTR immunoreactivity.

To confirm that morphine withdrawal promotes an increase in p75NTR in neurons, serial hippocampal sections from the dentate gyrus were immunostained for p75NTR. Immunoreactivity was found in the molecular and granule layers in all experimental groups (Figs. 3A, B and C). Confocal microscopy analysis of p75NTR immunoreactivity revealed a significant increase of immunofluorescence intensity (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 51) = 7.86; p = 0.0046) in mice undergoing withdrawal for 72 hr compared to saline or morphine-treated animals (Fig. 3D). Moreover, we found an increase in p75NTR immunoreactivity in NeuN positive cells in all experimental groups (Figs. 3A3–4, B3–4 and C3–4). Thus, the histological analysis confirms that morphine withdrawal up-regulates p75NTR protein levels in neurons.

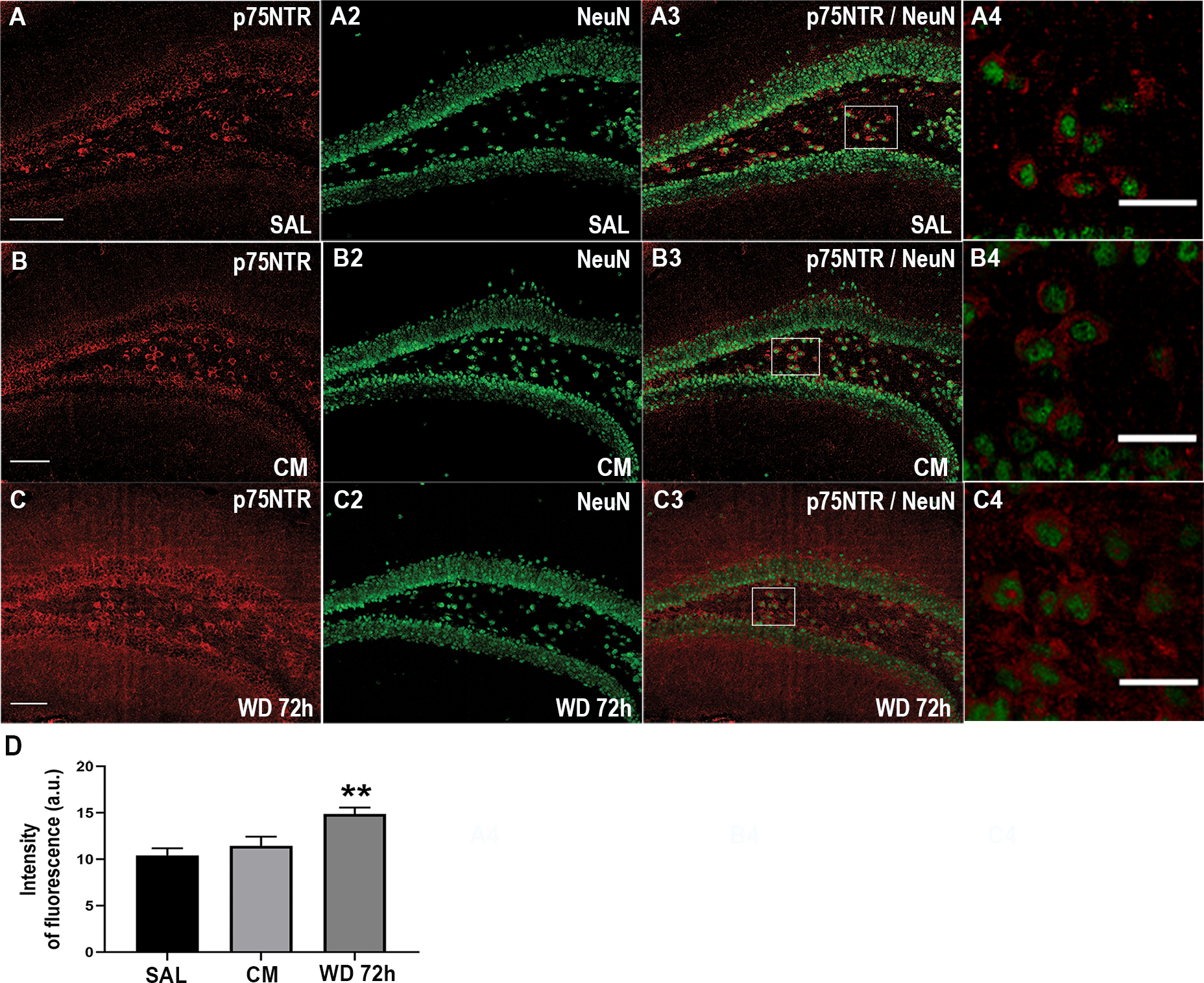

Figure 3.

Morphine withdrawal up-regulates p75NTR immunoreactivity in the hippocampus. Mice were injected subcutaneously with saline (SAL) or escalating doses of morphine (CM) for 5 days and euthanized 2 hr after the last injection. Another group of animals was allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal and euthanized 72 hr after the last injection (WD 72h) as described in Table 1. A-C. Representative confocal microscopy images of serial sections from the dentate gyrus stained for p75NTR and NeuN. A4, B4, C4. Higher magnification of the area indicated by a square in A3, B3 and C3. Scale bar in A, B and C = 100 μm, in A4, B4 and C4 = 10 μm. D. Quantitative analysis of the intensity of p75NTR immunofluorescence, expressed as arbitrary units (a.u.). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of 3 animals (N=3 biological replicates) with 3 technical replicates each (n=3 sections per animal, each of these technical replicates is the mean of 2 fields per section). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD. ** p < 0.01 vs saline.

P75NTR can also be expressed by non-neuronal cells after mechanical injury (Beattie et al. 2002, Brandoli et al. 2001) or by both neurons and astrocytes following status epilepticus (VonDran et al. 2014). Therefore, we stained serial hippocampal sections for the astrocytic marker GFAP (Fig. 4A) and p75NTR (Fig. 4A2). We found that p75NTR did not colocalize with GFAP (Fig. 4A3), supporting our data that morphine withdrawal changes the levels of p75NTR in neurons.

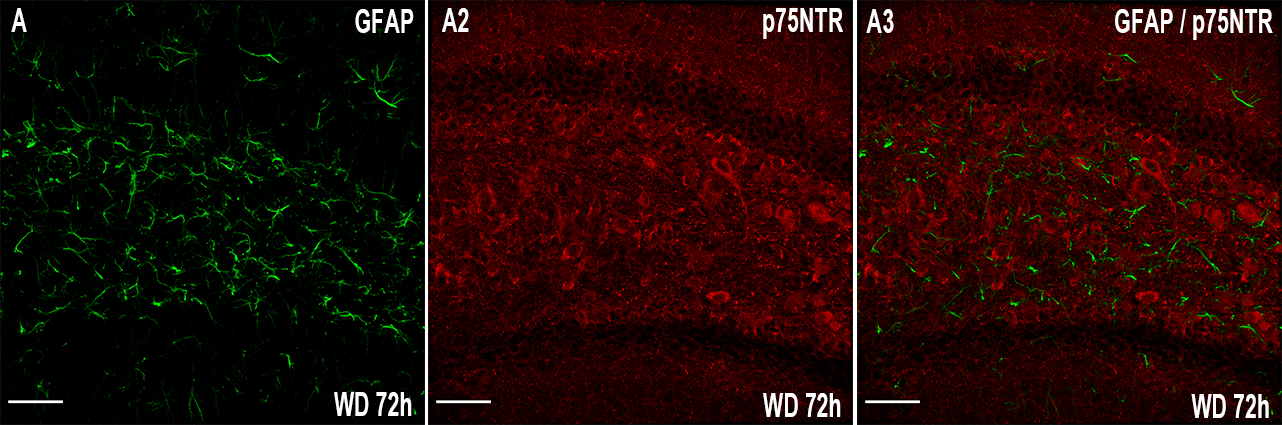

Figure 4.

Morphine withdrawal does not change p75NTR immunoreactivity in astrocytes. Mice were allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal and euthanized 72 hr after the last injection (WD 72h) as described in Table 1. A-C. Representative confocal microscopy images of serial sections from the dentate gyrus stained for GFAP and p75NTR. Scale bar = 50 μm.

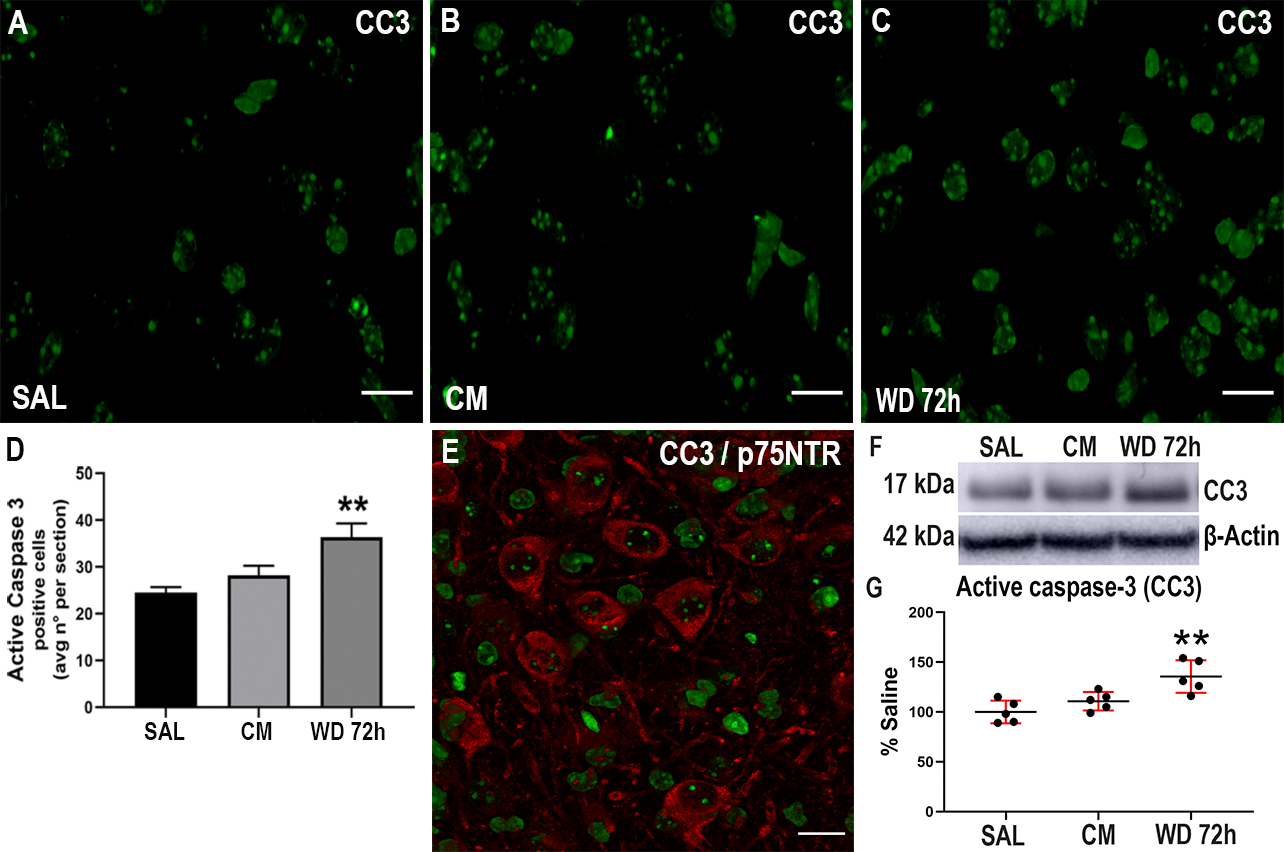

Morphine withdrawal activates apoptosis.

P75NTR activation promotes neuronal apoptosis. To examine whether the increased levels of p75NTR observed in animals undergoing withdrawal were associated with neuronal apoptosis, serial hippocampal sections were stained for active caspase-3 (Fig. 5) and the number of positive cells were counted using Image J software. We found a significant increase (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 51) = 7.51; p = 0.0055) in the number of active caspase-3 positive cells in animals undergoing withdrawal, compared to saline control animals (Fig. 5D). Importantly, we found that several active caspase-3 positive cells were also p75NTR positive (Fig. 5E), supporting the notion that p75NTR can be expressed in adult neurons undergoing apoptosis (Roux et al. 1999). The increase in active caspase-3 was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5F). Indeed, the levels of active caspase-3 were significantly higher in the morphine withdrawal group compared to saline group (Fig. 5G). (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 10.37; p = 0.0024). These data supports the hypothesis that morphine withdrawal induces a proapoptotic state via the activation of p75NTR.

Figure 5.

Morphine withdrawal increases active caspase-3. Mice were injected subcutaneously with saline (SAL) or escalating doses of morphine (CM) for 5 days and euthanized 2 hr after the last injection. Another group of animals was allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal and euthanized 72 hr after the last injection (WD 72h) as described in Table 1. A-C. Representative confocal microscopy images of serial sections from the dentate gyrus stained for active caspase-3 (CC3). Scale bar 20 μm. D. Quantitative analysis of the average number of CC3 positive cells per section. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of 3 animals (N=3 biological replicates) with 3 technical replicates each (n=3 sections per animal, each of these technical replicates is the mean of 2 fields per section). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD. ** p < 0.01 vs saline. E. Representative image of hippocampal sections stained for CC3 and p75NTR. F. Representative blot showing the hippocampal levels of CC3. G. Densitometric analysis expressed as percentage of saline after normalization with β-actin. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of 5 animals per group. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD. ** p < 0.01 vs saline.

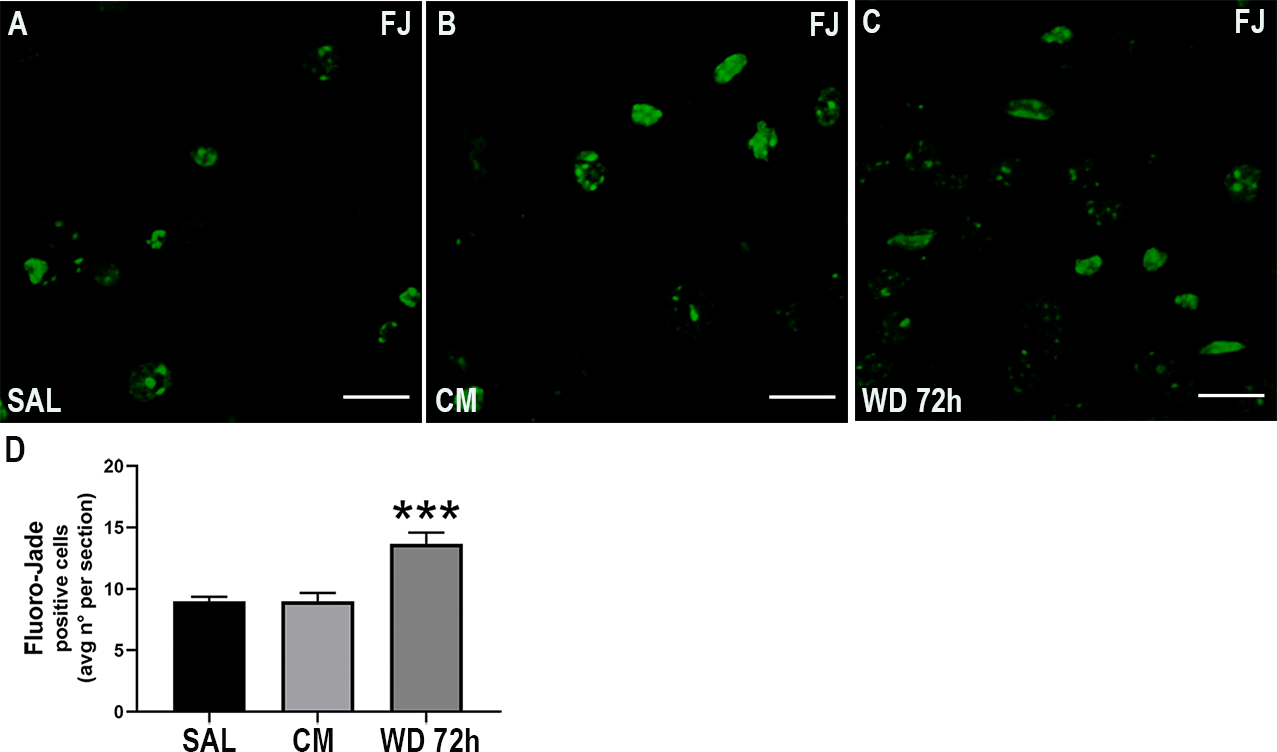

To confirm that withdrawal induces neuronal apoptosis, we stained several sections with Fluoro-Jade C (FJ) which detects degenerating neurons (Fig. 6). We found a significant increase (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 51) = 15.08; p = 0.0003) in the number of FJ positive cells in animals undergoing withdrawal, compared to the other groups (Fig. 6D). These data confirm that morphine withdrawal promotes neuronal degeneration.

Figure 6.

Morphine withdrawal increases the number of degenerating neurons. Mice were injected subcutaneously with saline (SAL) or escalating doses of morphine (CM) for 5 days and euthanized 2 hr after the last injection. Another group of animals was allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal and euthanized 72 hr after the last injection (WD 72h) as described in Table 1. A-C. Representative confocal microscopy images of serial sections from the dentate gyrus showing Fluoro-Jade (FJ) staining. Scale bar 20 μm. D. Quantitative analysis of the average number of FJ positive cells per section. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of 3 animals (N=3 biological replicates) with 3 technical replicates each (n=3 sections per animal, each of these technical replicates is the mean of 2 fields per section). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD. *** p < 0.001 vs saline.

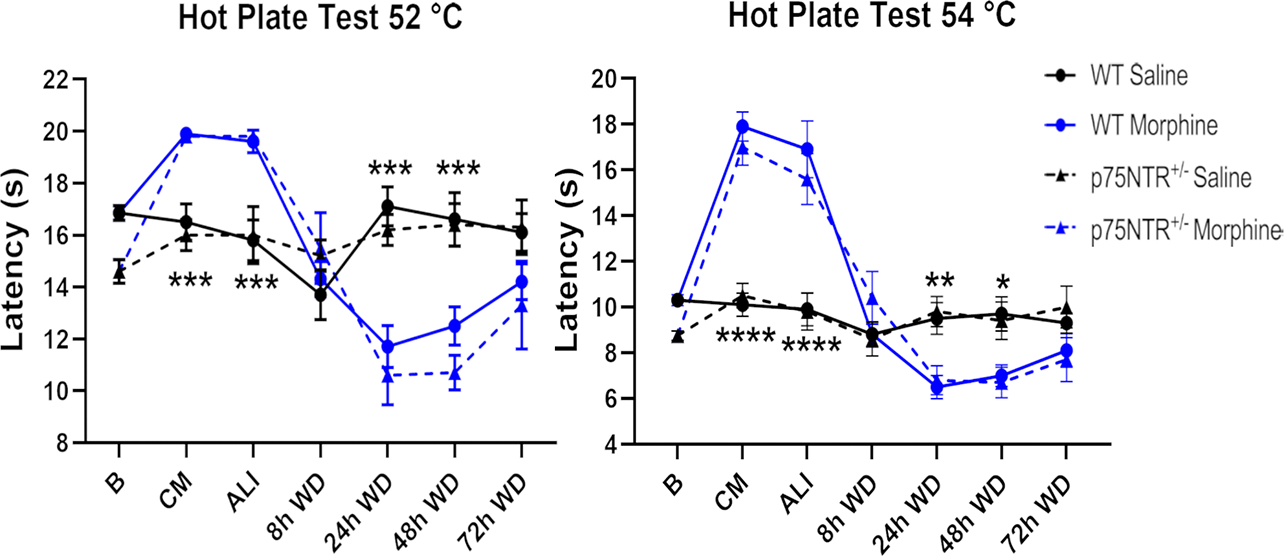

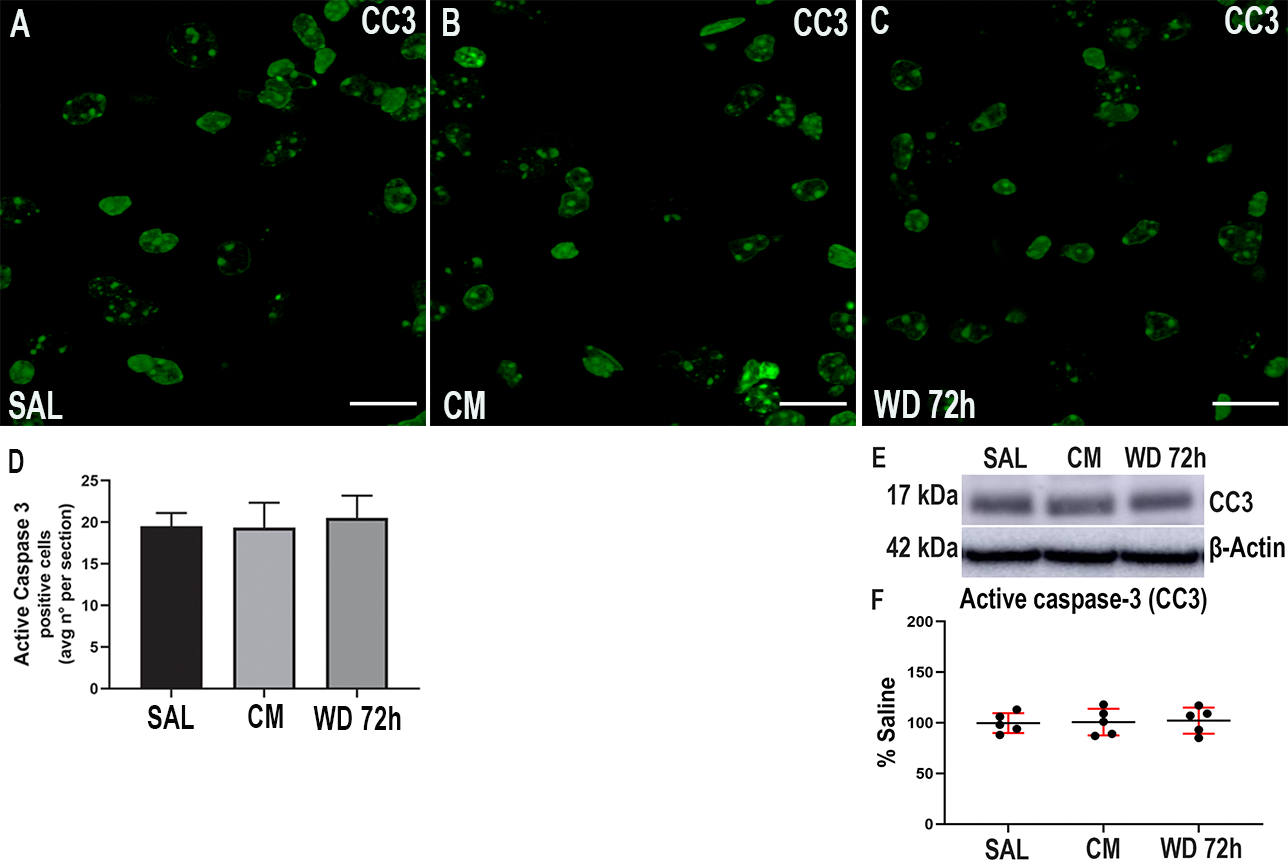

Activation of caspase-3 by morphine withdrawal is prevented in p75NTR+/− mice.

To establish whether p75NTR plays a role in withdrawal-dependent apoptosis, we used p75NTR+/− mice. We elected not to use p75NTR−/− (homozygous knockout) mice because these animals exhibit loss of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (Peterson et al. 1999) and profound deficit in sympathetic and sensory innervation and nociceptive impairment (Hannila & Kawaja 2005, Davies et al. 1993). Because inhibition of p75NTR has been shown to suppressed injury-induced neuropathic pain (Obata et al., 2006) as well as opioid analgesia (Trang et al. 2009), we first tested whether the lack of one p75NTR+/− allele changes sensitivity to thermal stimuli that could mask the pharmacological action of morphine. WT and p75NTR+/− mice treated with morphine or saline were tested for thermal sensitivity using the hot plate test. We found that p75NTR+/− mice have a degree of analgesia similar to WT (Fig. 7). Moreover, the sensitivity to morphine in p75NTR+/− and WT mice was similar (Fig. 7) sugggesting that the removal of only one p75NTR allele does not affect nociceptive transmission. Lastly, withdrawal animals exhibited an increase in thermal sensitivity when compared to controls, confirming a typical sign of withdrawal syndrome.

Figure 7.

Deletion of one p75NTR allele does not affect the sensitivity to thermal stimuli on the hot plate test over the treatment-withdrawal paradigm. Representative graphs showing Wild Type (WT) and p75NTR+/− mice thermal sensitivity at 52 and 54 °C. Baseline sensitivity (B) was established before starting the experiment. Mice were tested 2 hr after saline or chronic morphine (CM) treatment. A group of animals were allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal and tested at 2 hr after the last injection (ALI) and at 8, 24, 48 and 72 hr after the last injection (WD). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 vs saline.

To establish whether there is a correlation between activation of p75NTR and the increased number of active caspase-3 positive cells, we treated p75NTR+/− mice with the same morphine paradigm described in Table 1. We found no difference in active caspase-3 levels between the experimental groups among p75NTR+/− animals (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 51) = 0.03; p = 0.9735) (Figs. 8A–D). These data were replicated by Western blot analysis (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 0.05; p = 0.9516) (Figs. 8E and F). These data suggest that deletion of one p75NTR allele is sufficient to protect against the neurotoxicity caused by morphine withdrawal.

Figure 8.

Morphine withdrawal does not change active caspase-3 in p75NTR+/− mice. Mice were injected subcutaneously with saline (SAL) or escalating doses of morphine (CM) for 5 days and euthanized 2 hr after the last injection. Another group of animals was allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal and euthanized 72 hr after the last injection (WD 72h) as described in Table 1. A-C. Representative confocal microscopy images of serial sections from the dentate gyrus stained for active caspase-3 (CC3). Scale bar = 20 μm. D. Quantitative analysis of the average number of positive cells per section. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of 3 animals (N=3 biological replicates) with 3 technical replicates each (n=3 sections per animal, each of these technical replicates is the mean of 2 fields per section). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD. E. Representative blot showing the hippocampal levels of CC3. F. Densitometric analysis expressed as percentage of saline after normalization with β-actin. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of 5 animals per group. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD.

Morphine withdrawal activates JNK.

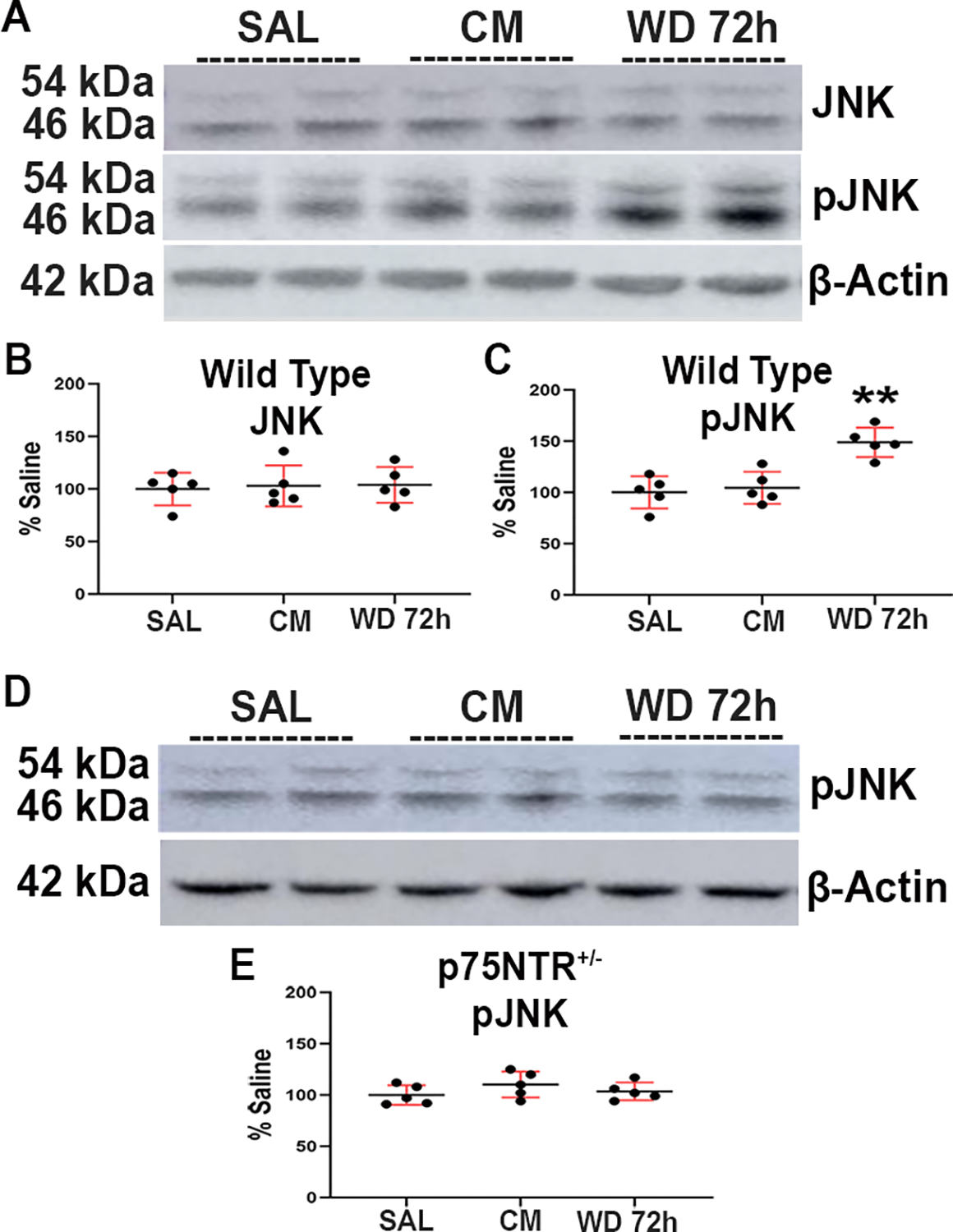

The p75NTR/sortilin complex activates caspases 3, 6 and 9 as well as the JNK pathway (Bhakar et al. 2003, Aloyz et al. 1998). JNK, a stress-activated member of MAP kinase family, has been strongly implicated in inflammatory responses, neurodegeneration, and apoptosis. To determine whether chronic morphine or withdrawal activates p75NTR-associated intracellular signaling that leads to programmed cell death, we measured the levels of JNK isoforms p46JNK and p54JNK by Western blot. No changes in the total JNK were observed among the experimental groups (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 0.07; p = 0.9321) (Figs. 9A and B). We next measured the levels of phosphorylated JNK (pJNK) and we found that animals undergoing withdrawal exhibited a significant increase of pJNK (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 10.67; p = 0.0022) compared to the other experimental groups (Figs. 9A and C). These data suggest that morphine withdrawal activates an intracellular signaling pathway that facilitates neuronal apoptosis.

Figure 9.

Morphine withdrawal increases the levels of pJNK in the hippocampus of wild type mice. Wild type and p75NTR+/− mice were injected subcutaneously with saline (SAL) or escalating doses of morphine (CM) for 5 days and euthanized 2 hr after the last injection. Another group of animals was allowed to undergo 4 cycles of spontaneous withdrawal and euthanized 72 hr after the last injection (WD 72h) as described in Table 1. A. Representative blot showing the hippocampal levels of JNK and pJNK in wild type mice. D. Immunoblot showing the hippocampal levels of pJNK in p75NTR+/− mice. Every band in the blot represents a different sample. B, C, E. Densitometric analysis presented as percentage of saline after normalization with β-actin. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of 5 animals per group. One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD. ** p < 0.01 vs saline.

To investigate whether the increased levels of pJNK were related to p75NTR activation, p75NTR+/− mice were treated with the same morphine paradigm and allowed them to undergo cycles of withdrawal as described in Table 1. Neither CM nor withdrawal changed the levels of pJNK in p75NTR+/− mice (One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD; F (2, 12) = 1.228; p = 0.3273) (Figs. 9D and E). These data suggest that the increased levels of pJNK induced by morphine withdrawal is p75NTR-dependent.

Discussion

OUD is a medical condition defined as the inability to abstain from using opioids despite the development of serious medical consequences. Several reports have shown that chronic use of opioid drugs have a negative impact on cognition (Welsch et al. 2020). Because opioid abusers undergo intermittent periods of withdrawal, impaired cognitive capabilities can be brought about withdrawal-mediated impaired hippocampal function. It has been proposed that opioid withdrawal activates glial cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines (Hutchinson et al. 2009, Garcia-Perez et al. 2017), including IL-1β and TNFα, in several brain areas (Campbell et al. 2013). When pro-inflammatory cytokines are released, they may cause brain damage (Colonna & Butovsky 2017). Likewise, morphine withdrawal increases proBDNF (Bachis et al. 2017), which, through p75NTR, decreases neuronal survival (Teng et al. 2005) and induces pruning of synapses (Orefice et al. 2016). Here, we report that morphine withdrawal increases the levels of p75NTR while reducing TrkB in synaptosomes prepared from the hippocampus. When activation of p75NTR is unopposed by a concomitant activation of TrkB, it evokes neuronal apoptosis and facilitates LTD (Woo et al. 2005). Thus, we propose that the activaton of p75NTR and its downstrem signaling is a new mechanism to explain the ability of morphine withdrawal to promote a pro-apoptotic environment.

In rodents, chronic morphine increases silent synapses and spinogenesis (Ferguson et al. 2013, Robinson et al. 2002); these effects are also mediated by BDNF (Govindarajan et al. 2006, Cabezas & Buno 2011). Clinical studies have suggested a role for BDNF in mediating molecular and behavoral features underlying drug abuse (Li & Wolf 2015). Higher plasma levels of BDNF are associated with increased craving for heroin (Heberlein et al. 2011). In addition, a polymorphism (Val66Met) in the BDNF gene, which regulates the release of BDNF (Egan et al. 2003), has been linked to heroin-seeking behavior (Greenwald et al. 2013). Serum BDNF levels are negatively correlated with the severity of withdrawal signs in alcohol-dependent subjects (Heberlein et al. 2010, Costa et al. 2011). In rodents, BDNF administration into the ventral tegmental area induces an opiate dependent behavioral (Vargas-Perez et al. 2009). Morphine administration increases BDNF expression in different brain areas (Hatami et al. 2007, Rouhani et al. 2019, Bolanos & Nestler 2004), whereas morphine withdrawal decreases BDNF levels by inhibiting its processing from proBDNF (Bachis et al. 2017) or through a histone modification of the BDNF promoter (Mashayekhi et al. 2012). Here we show that withdrawal by up-regulating p75NTR and decreasing TrkB in synapses causes an imbalance in the expression of these two receptors. Such imbalance has been shown to induce the phosphorylation of JNK, a kinase with pro-apoptotic properties for neurons (Yang et al. 1997), and the activation of apoptotic cascades (Brito et al. 2013). Thus, it is not surprising that morphine withdrawal-mediated accumulation of p75NTR in synaptosomes is accompanied by a significant increase of active caspase-3 and activation of JNK, one of the key proapoptotic signaling events activated by p75NTR (Casaccia-Bonnefil et al. 1996, Bhakar et al. 2003). However, our data do not exclude that the activation of others signaling proteins could mediate the effect of p75NTR. It will be important in future experiments to examine additional down-stream targets of p75NTR signaling, including p38MAPK (Pham et al. 2019), or p75NTR gene network (Sajanti et al. 2020) to better understand the role that p75NTR signaling plays in OUD. Overall, our data suggest that morphine withdrawal contributes to increasing neuronal vulnerability to neurodegeneration. It remains to be established whether the extent of apoptosis observed in our studies can lead to an impaired cognitive behavior.

JNK is also activated by pro-inflammatory stimuli including TNF-α (Mohamed et al. 2002). This cytokine is increased during morphine withdrawal but decreased by morphine treatment (Campbell et al. 2013). Moreover, morphine withdrawal reduces the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as CCL5 (Desjardins et al. 2008, Hutchinson et al. 2011, Eisenstein et al. 2006, Campbell et al. 2013). Although we cannot completely rule out the involvment of cytokines in morphine withdrawal induced neuronal apoptosis, our data show that the removal of one p75NTR allele prevents the activation of both JNK and caspase-3 induced by morphine withdrawal. Thus, our data support the notion that p75NTR mediates apoptosis and synaptic simplification not only during development but also in the mature hippocampus (Zagrebelsky et al. 2005).

Our findings reported here show that morphine withdrawal increases p75NTR levels. In contrast, no changes in p75NTR levels were seen in morphine-treated mice. How morphine withdrawal up-regulates p75NTR levels is still under investigation. In the adult CNS, the expression of p75NTR in vivo can be modulated by injury, stimuli, and in various CNS pathologies. For instance, increased p75NTR expression is observed in injured cerebral cortex (Saadipour et al. 2019) or spinal cord (Beattie et al. 2002), or in the hippocampus after seizure (Volosin et al. 2008, VonDran et al. 2014). Anatomically specific up-regulation of p75NTR has also been described in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s (Hu et al. 2002b) and Huntington’s diseases (Suelves et al. 2018), or during alcohol withdrawal (Darcq et al., 2016). One stimulus known to induce p75NTR activation is proBDNF (Riffault et al. 2014). This BDNF species is up-regulated during morphine withdrawal in rats through a decrease of proBDNF-cleaving proteases (Bachis et al. 2017). Thus, proBDNF may likewise mediate the increase of p75NTR in synapses, although we cannot rule out that the increase in p75NTR could be due to the other pro-neurotrophins that bind to p75NTR. We can exclude that the accumulation of p75NTR in synaptosomes is due to an increase of synapses because the levels of TrkB and glutamate receptor subunits are decreased in withdrawal animals. Nevertheless, p75NTR undergoes internalization and axonal transport (Bronfman et al. 2007). Thus, we cannot exclude that morphine withdrawal may affect the internalization of p75NTR. More studies are needed to confirm or refute these mechansims.

In conclusion, morphine withdrawal increases p75NTR in hippocampal synapses. This increase is followed by a sustained activation of the p75NTR signaling pathway, including, but not limited to, pJNK and active caspase-3. p75NTR signaling can counteract TrkB signaling (Song et al. 2010, Chapleau & Pozzo-Miller 2012). This effect may explain why chronic opioid use inhibits neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus (Eisch et al. 2000, Kahn et al. 2005). Moreover, p75NTR activation reduces hippocampal LTP, which is considered the neuronal substrate for learning and memory. Thus, increased p75NTR signaling may be a novel mechanism to explain impaired cognitive functions in opioid abusers during the abstinence syndrome (Rapeli et al. 2006, Yeoh et al. 2019).

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grants R01 NS079172 and R21 NS102121 to IM, and T32 041218 to AS.

Abbreviations used are:

- ALI

after last injection

- AMPAR

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- a.u.

arbitrary units

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CC3

active caspase-3

- CM

chronic morphine

- eut

euthanized

- FJ

Fluoro-Jade

- GFAP

glial-fibrillary acidic protein

- HAND

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder

- HSD

honestly significant difference

- IL-1β

interleukin 1 beta

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- N

number of animals used

- NeuN

neuronal nuclear protein

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

- NR2B

N-methyl D-aspartate receptor subunit 2B

- OUD

opioid use disorder

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- pJNK

phosphorylated JNK

- p75NTR

p75 neurotrophin receptor

- RhoA

Ras homolog family member A

- SAL

saline; s.c.= subcutaneous

- SD

standard deviation

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TrkB

tropomyosin receptor kinase B

- WD

withdrawal

- WT

wild type.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest. The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- Abdel-Zaher AO, Mostafa MG, Farghaly HS, Hamdy MM and Abdel-Hady RH (2013) Role of oxidative stress and inducible nitric oxide synthase in morphine-induced tolerance and dependence in mice. Effect of alpha-lipoic acid. Behav Brain Res, 247, 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloyz RS, Bamji SX, Pozniak CD, Toma JG, Atwal J, Kaplan DR and Miller FD (1998) p53 is essential for developmental neuron death as regulated by the TrkA and p75 neurotrophin receptors. J Cell Biol, 143, 1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvandi MS, Bourmpoula M, Homberg JR and Fathollahi Y (2017) Association of contextual cues with morphine reward increases neural and synaptic plasticity in the ventral hippocampus of rats. Addict Biol, 22, 1883–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker C and Hen R (2017) Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive flexibility - linking memory and mood. Nat Rev Neurosci, 18, 335–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachis A, Avdoshina V, Zecca L, Parsadanian M and Mocchetti I (2012) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 alters brain-derived neurotrophic factor processing in neurons. J Neurosci, 32, 9477–9484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachis A, Campbell LA, Jenkins K, Wenzel E and Mocchetti I (2017) Morphine Withdrawal Increases Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Precursor. Neurotox Res, 32, 509–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajic D, Commons KG and Soriano SG (2013) Morphine-enhanced apoptosis in selective brain regions of neonatal rats. Int J Dev Neurosci, 31, 258–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balter RE and Dykstra LA (2012) The effect of environmental factors on morphine withdrawal in C57BL/6J mice: running wheel access and group housing. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 224, 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie MS, Harrington AW, Lee R, Kim JY, Boyce SL, Longo FM, Bresnahan JC, Hempstead BL and Yoon SO (2002) ProNGF induces p75-mediated death of oligodendrocytes following spinal cord injury. Neuron, 36, 375–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakar AL, Howell JL, Paul CE, Salehi AH, Becker EB, Said F, Bonni A and Barker PA (2003) Apoptosis induced by p75NTR overexpression requires Jun kinase-dependent phosphorylation of Bad. J Neurosci, 23, 11373–11381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolanos CA and Nestler EJ (2004) Neurotrophic mechanisms in drug addiction. Neuromolecular Med, 5, 69–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandoli C, Shi B, Pflug B, Andrews P, Wrathall JR and Mocchetti I (2001) Dexamethasone reduces the expression of p75 neurotrophin receptor and apoptosis in contused spinal cord. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 87, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito V, Puigdellivol M, Giralt A, del Toro D, Alberch J and Gines S (2013) Imbalance of p75(NTR)/TrkB protein expression in Huntington’s disease: implication for neuroprotective therapies. Cell Death Dis, 4, e595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfman FC, Escudero CA, Weis J and Kruttgen A (2007) Endosomal transport of neurotrophins: roles in signaling and neurodegenerative diseases. Dev Neurobiol, 67, 1183–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas C and Buno W (2011) BDNF is required for the induction of a presynaptic component of the functional conversion of silent synapses. Hippocampus, 21, 374–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LA, Avdoshina V, Rozzi S and Mocchetti I (2013) CCL5 and cytokine expression in the rat brain: differential modulation by chronic morphine and morphine withdrawal. Brain Behav Immun, 34, 130–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Carter BD, Dobrowsky RT and Chao MV (1996) Death of oligodendrocytes mediated by the interaction of nerve growth factor with its receptor p75. Nature, 383, 716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapleau CA and Pozzo-Miller L (2012) Divergent roles of p75NTR and Trk receptors in BDNF’s effects on dendritic spine density and morphology. Neural Plast, 2012, 578057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciammola A, Sassone J, Cannella M, Calza S, Poletti B, Frati L, Squitieri F and Silani V (2007) Low brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in serum of Huntington’s disease patients. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet, 144, 574–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M and Butovsky O (2017) Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol, 35, 441–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa MA, Girard M, Dalmay F and Malauzat D (2011) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor serum levels in alcohol-dependent subjects 6 months after alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 35, 1966–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AM, Lee KF and Jaenisch R (1993) p75-deficient trigeminal sensory neurons have an altered response to NGF but not to other neurotrophins. Neuron, 11, 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins S, Belkai E, Crete D, Cordonnier L, Scherrmann JM, Noble F and Marie-Claire C (2008) Effects of chronic morphine and morphine withdrawal on gene expression in rat peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Neuropharmacology, 55, 1347–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH et al. (2003) The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell, 112, 257–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisch AJ, Barrot M, Schad CA, Self DW and Nestler EJ (2000) Opiates inhibit neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 97, 7579–7584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein TK, Rahim RT, Feng P, Thingalaya NK and Meissler JJ (2006) Effects of opioid tolerance and withdrawal on the immune system. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol, 1, 237–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson D, Koo JW, Feng J et al. (2013) Essential role of SIRT1 signaling in the nucleus accumbens in cocaine and morphine action. J Neurosci, 33, 16088–16098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman WJ (2000) Neurotrophins induce death of hippocampal neurons via the p75 receptor. J Neurosci, 20, 6340–6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Perez D, Laorden ML and Milanes MV (2017) Acute Morphine, Chronic Morphine, and Morphine Withdrawal Differently Affect Pleiotrophin, Midkine, and Receptor Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase beta/zeta Regulation in the Ventral Tegmental Area. Mol Neurobiol, 54, 495–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan A, Rao BS, Nair D, Trinh M, Mawjee N, Tonegawa S and Chattarji S (2006) Transgenic brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression causes both anxiogenic and antidepressant effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103, 13208–13213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald MK, Steinmiller CL, Sliwerska E, Lundahl L and Burmeister M (2013) BDNF Val(66)Met genotype is associated with drug-seeking phenotypes in heroin-dependent individuals: a pilot study. Addict Biol, 18, 836–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber SA, Silveri MM and Yurgelun-Todd DA (2007) Neuropsychological consequences of opiate use. Neuropsychol Rev, 17, 299–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra D, Sole A, Cami J and Tobena A (1987) Neuropsychological performance in opiate addicts after rapid detoxification. Drug Alcohol Depend, 20, 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H, Dong Z, Jia Y, Mao R, Zhou Q, Yang Y, Wang L, Xu L and Cao J (2015) Opioid addiction and withdrawal differentially drive long-term depression of inhibitory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Sci Rep, 5, 9666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannila SS and Kawaja MD (2005) Nerve growth factor-mediated collateral sprouting of central sensory axons into deafferentated regions of the dorsal horn is enhanced in the absence of the p75 neurotrophin receptor. J Comp Neurol, 486, 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatami H, Oryan S, Semnanian S, Kazemi B, Bandepour M and Ahmadiani A (2007) Alterations of BDNF and NT-3 genes expression in the nucleus paragigantocellularis during morphine dependency and withdrawal. Neuropeptides, 41, 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein A, Dursteler-MacFarland KM, Lenz B et al. (2011) Serum levels of BDNF are associated with craving in opiate-dependent patients. J Psychopharmacol, 25, 1480–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein A, Muschler M, Wilhelm J, Frieling H, Lenz B, Groschl M, Kornhuber J, Bleich S and Hillemacher T (2010) BDNF and GDNF serum levels in alcohol-dependent patients during withdrawal. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 34, 1060–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hempstead BL (2002) The many faces of p75NTR. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 12, 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells DW, Porritt MJ, Wong JYF, Batchelor PE, Kalnins R, Hughes AJ and Donnan GA (2000) Reduced BDNF mRNA expression in the Parkinson’s Disease substantia nigra. Exp Neurol, 166, 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Sheng WS, Lokensgard JR and Peterson PK (2002a) Morphine induces apoptosis of human microglia and neurons. Neuropharmacology, 42, 829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XY, Zhang HY, Qin S, Xu H, Swaab DF and Zhou JN (2002b) Increased p75(NTR) expression in hippocampal neurons containing hyperphosphorylated tau in Alzheimer patients. Exp Neurol, 178, 104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MR, Lewis SS, Coats BD et al. (2009) Reduction of opioid withdrawal and potentiation of acute opioid analgesia by systemic AV411 (ibudilast). Brain Behav Immun, 23, 240–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MR, Shavit Y, Grace PM, Rice KC, Maier SF and Watkins LR (2011) Exploring the neuroimmunopharmacology of opioids: an integrative review of mechanisms of central immune signaling and their implications for opioid analgesia. Pharmacol Rev, 63, 772–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn L, Alonso G, Normand E and Manzoni OJ (2005) Repeated morphine treatment alters polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule, glutamate decarboxylase-67 expression and cell proliferation in the adult rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci, 21, 493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DR and Miller FD (2000) Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol, 10, 381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll SL, Nikolic E, Bieri F, Soyka M, Baumgartner MR and Quednow BB (2018) Cognitive and socio-cognitive functioning of chronic non-medical prescription opioid users. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 235, 3451–3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KF, Li E, Huber LJ, Landis SC, Sharpe AH, Chao MV and Jaenisch R (1992) Targeted mutation of the gene encoding the low affinity NGF receptor p75 leads to deficits in the peripheral sensory nervous system. Cell, 69, 737–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X and Wolf ME (2015) Multiple faces of BDNF in cocaine addiction. Behav Brain Res, 279, 240–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Sung B, Ji RR and Lim G (2002) Neuronal apoptosis associated with morphine tolerance: evidence for an opioid-induced neurotoxic mechanism. J Neurosci, 22, 7650–7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashayekhi FJ, Rasti M, Rahvar M, Mokarram P, Namavar MR and Owji AA (2012) Expression levels of the BDNF gene and histone modifications around its promoters in the ventral tegmental area and locus ceruleus of rats during forced abstinence from morphine. Neurochem Res, 37, 1517–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed AA, Jupp OJ, Anderson HM, Littlejohn AF, Vandenabeele P and MacEwan DJ (2002) Tumour necrosis factor-induced activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase is sensitive to caspase-dependent modulation while activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) or p38 MAPK is not. Biochem J, 366, 145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel L, Hoscheidt S and Ryan LR (2013) Spatial cognition and the hippocampus: the anterior-posterior axis. J Cogn Neurosci, 25, 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orefice LL, Shih CC, Xu H, Waterhouse EG and Xu B (2016) Control of spine maturation and pruning through proBDNF synthesized and released in dendrites. Mol Cell Neurosci, 71, 66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou CC, Liappas IA, Ventouras EM, Nikolaou CC, Kitsonas EN, Uzunoglu NK and Rabavilas AD (2004) Long-term abstinence syndrome in heroin addicts: indices of P300 alterations associated with a short memory task. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 28, 1109–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KJ, Grosso CA, Aubert I, Kaplan DR and Miller FD (2010) p75NTR-dependent, myelin-mediated axonal degeneration regulates neural connectivity in the adult brain. Nat Neurosci, 13, 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson DA, Dickinson-Anson HA, Leppert JT, Lee KF and Gage FH (1999) Central neuronal loss and behavioral impairment in mice lacking neurotrophin receptor p75. J Comp Neurol, 404, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham DD, Bruelle C, Thi Do H et al. (2019) Caspase-2 and p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) are involved in the regulation of SREBP and lipid genes in hepatocyte cells. Cell Death Dis, 10, 537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapeli P, Kivisaari R, Autti T, Kahkonen S, Puuskari V, Jokela O and Kalska H (2006) Cognitive function during early abstinence from opioid dependence: a comparison to age, gender, and verbal intelligence matched controls. BMC Psychiatry, 6, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffault B, Medina I, Dumon C, Thalman C, Ferrand N, Friedel P, Gaiarsa JL and Porcher C (2014) Pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor inhibits GABAergic neurotransmission by activating endocytosis and repression of GABAA receptors. J Neurosci, 34, 13516–13534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Gorny G, Savage VR and Kolb B (2002) Widespread but regionally specific effects of experimenter- versus self-administered morphine on dendritic spines in the nucleus accumbens, hippocampus, and neocortex of adult rats. Synapse, 46, 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhani F, Khodarahmi P and Naseh V (2019) NGF, BDNF and Arc mRNA Expression in the Hippocampus of Rats After Administration of Morphine. Neurochem Res, 44, 2139–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux PP, Colicos MA, Barker PA and Kennedy TE (1999) p75 neurotrophin receptor expression is induced in apoptotic neurons after seizure. J Neurosci, 19, 6887–6896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin RD, Watson PD, Duff MC and Cohen NJ (2014) The role of the hippocampus in flexible cognition and social behavior. Front Hum Neurosci, 8, 742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo SJ, Mazei-Robison MS, Ables JL and Nestler EJ (2009) Neurotrophic factors and structural plasticity in addiction. Neuropharmacology, 56 Suppl 1, 73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadipour K, Tiberi A, Lombardo S et al. (2019) Regulation of BACE1 expression after injury is linked to the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Mol Cell Neurosci, 99, 103395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajanti A, Lyne SB, Girard R et al. (2020) A comprehensive p75 neurotrophin receptor gene network and pathway analyses identifying new target genes. Sci Rep, 10, 14984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt P, Haberthur A and Soyka M (2017) Cognitive Functioning in Formerly Opioid-Dependent Adults after At Least 1 Year of Abstinence: A Naturalistic Study. Eur Addict Res, 23, 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Volosin M, Cragnolini AB, Hempstead BL and Friedman WJ (2010) ProNGF induces PTEN via p75NTR to suppress Trk-mediated survival signaling in brain neurons. J Neurosci, 30, 15608–15615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga S, Serra GP, Puddu MC, Foddai M and Diana M (2003) Morphine withdrawal-induced abnormalities in the VTA: confocal laser scanning microscopy. Eur J Neurosci, 17, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suelves N, Miguez A, Lopez-Benito S et al. (2018) Early Downregulation of p75(NTR) by Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches Delays the Onset of Motor Deficits and Striatal Dysfunction in Huntington’s Disease Mice. Mol Neurobiol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng HK, Teng KK, Lee R et al. (2005) ProBDNF induces neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTR and sortilin. J Neurosci, 25, 5455–5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda T, Momose Y, Murata M, Tamiya G, Yamamoto M, Hattori N and Inoko H (2003) Toward identification of susceptibility genes for sporadic Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol, 250 Suppl 3, III40–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tramullas M, Martinez-Cue C and Hurle MA (2007) Chronic methadone treatment and repeated withdrawal impair cognition and increase the expression of apoptosis-related proteins in mouse brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 193, 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trang T, Koblic P, Kawaja M and Jhamandas K (2009) Attenuation of opioid analgesic tolerance in p75 neurotrophin receptor null mutant mice. Neurosci Lett, 451, 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Perez H, Ting AKR, Walton CH et al. (2009) Ventral tegmental area BDNF induces an opiate-dependent-like reward state in naive rats. Science, 324, 1732–1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volosin M, Trotter C, Cragnolini A, Kenchappa RS, Light M, Hempstead BL, Carter BD and Friedman WJ (2008) Induction of proneurotrophins and activation of p75NTR-mediated apoptosis via neurotrophin receptor-interacting factor in hippocampal neurons after seizures. J Neurosci, 28, 9870–9879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VonDran MW, LaFrancois J, Padow VA, Friedman WJ, Scharfman HE, Milner TA and Hempstead BL (2014) p75NTR, but not proNGF, is upregulated following status epilepticus in mice. ASN Neuro, 6 (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch L, Bailly J, Darcq E and Kieffer BL (2020) The Negative Affect of Protracted Opioid Abstinence: Progress and Perspectives From Rodent Models. Biol Psychiatry, 87, 54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo NH, Teng HK, Siao CJ, Chiaruttini C, Pang PT, Milner TA, Hempstead BL and Lu B (2005) Activation of p75NTR by proBDNF facilitates hippocampal long-term depression. Nat Neurosci, 8, 1069–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T and Tohyama M (2003) The p75 receptor acts as a displacement factor that releases Rho from Rho-GDI. Nat Neurosci, 6, 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Tucker KL and Barde YA (1999) Neurotrophin binding to the p75 receptor modulates Rho activity and axonal outgrowth. Neuron, 24, 585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Khosravi-Far R, Chang HY and Baltimore D (1997) Daxx, a novel Fas-binding protein that activates JNK and apoptosis. Cell, 89, 1067–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh SL, Eastwood J, Wright IM, Morton R, Melhuish E, Ward M and Oei JL (2019) Cognitive and Motor Outcomes of Children With Prenatal Opioid Exposure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open, 2, e197025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SO, Casaccia-Bonnefil P, Carter B and Chao MV (1998) Competitive signaling between TrkA and p75 nerve growth factor receptors determines cell survival. J. Neurosci, 18, 3273–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younger JW, Chu LF, D’Arcy NT, Trott KE, Jastrzab LE and Mackey SC (2011) Prescription opioid analgesics rapidly change the human brain. Pain, 152, 1803–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagrebelsky M, Holz A, Dechant G, Barde YA, Bonhoeffer T and Korte M (2005) The p75 neurotrophin receptor negatively modulates dendrite complexity and spine density in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci, 25, 9989–9999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai T, Shao Y, Chen G et al. (2015) Nature of functional links in valuation networks differentiates impulsive behaviors between abstinent heroin-dependent subjects and nondrug-using subjects. Neuroimage, 115, 76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]