Abstract

Mice deficient in phox (gp91phox−/−) or NOS2 (NOS2−/−) were infected with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) to evaluate the importance of these pathways in the eradication of HGE bacteria. NOS2−/− mice had delayed clearance of the HGE agent in comparison to control or gp91phox−/− mice, suggesting that reactive nitrogen intermediates play a role in the early control of HGE.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is a newly recognized vector-borne infectious disease of increasing importance in the United States and Europe (3, 6, 16, 22). Prominent clinical manifestations of disease include fever, headache, and myalgias (23). HGE bacteria primarily infect neutrophils and survive within membrane-bound vacuoles known as morulae (23). A promyelocytic cell line (HL-60) has been used to culture HGE organisms in vitro, and bone marrow precursors have been infected with the HGE agent, stimulating further research (9, 10, 14). Mice can also be infected with HGE bacteria, facilitating in vivo studies of pathogenesis and immunity (2, 11, 21). Immunocompetent mice develop an infection in which the HGE agent is usually detected during the first 10 days of infection and is then generally cleared from the bloodstream (2, 20, 21). Sometimes, however, ehrlichiae can be detected by PCR at later intervals after challenge (2, 20, 21).

Two important microbicidal pathways of phagocytes are the production of reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) by respiratory burst oxidase (phox) and reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI) by inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) (4, 7). Mice deficient in phox (gp91phox−/−) or NOS2 (NOS2−/−) have also demonstrated the importance of these enzymes in host defense against a variety of pathogens (5, 18, 19). Recent data suggest that HGE bacteria use several strategies to survive within the hostile environment of the neutrophil. Morulae do not fuse with lysosomes, providing one mechanism of persistence (17, 24). HGE bacteria also inhibit the formation of ROI through selective downregulation of the gp91phox component of the NADPH oxidase complex (1). HGE in mice deficient in phox or NOS2 was investigated to understand the role of ROI and RNI in granulocytic ehrlichiosis.

Granulocytic ehrlichiosis in gp91phox−/− or NOS2−/− mice.

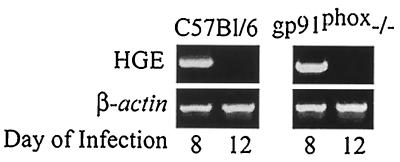

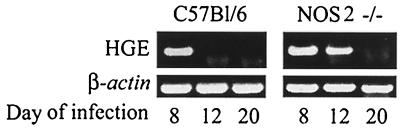

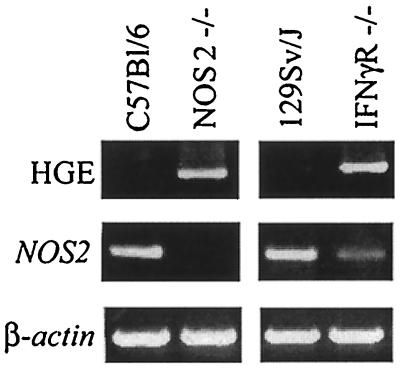

Mice were infected with HGE bacteria and then examined for infection at intervals up to 20 days. For infection, blood (0.1 ml) from C.B.17 SCID mice infected with ehrlichiae (donors) was intraperitoneally injected into wild-type (control), gp91phox−/−, or NOS2−/− mice (20). SCID mice had morulae in 10% of the neutrophils, thereby ensuring challenge with a constant number of organisms to each experimental mouse. Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was then used to assess levels of viable ehrlichiae in the splenocytes. cDNA was prepared from total RNA isolated from pooled splenocytes of groups of five control and experimental mice, and PCR was performed using 16S rRNA primers (5′-TGT AGG CGG TTC GGT AAG TTA AAG-3′ and 5′-GCA CTC ATC GTT TAC AGC GTG-3′) that amplify a 250-bp fragment specific for HGE (20). In the first experiment, both gp91phox−/− (5) and control mice had detectable bacteria on day 8 (Fig. 1). Ehrlichiae were no longer detectable by PCR in either the control or gp91phox−/− animals on day 12, demonstrating substantial clearance of the pathogen at this point. In a second study, NOS2−/− mice (15) had appreciable HGE on day 12 and then cleared the HGE agent on day 20, indicating a delay in bacterial clearance (Fig. 2). Since signaling of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) through its receptor results in induction of NOS2 (12), HGE infection in mice lacking the IFN-γ receptor (IFN-γR−/−) was also evaluated (13). At 12 days ehrlichiae were detected in NOS2−/− and IFN-γR−/− mice but not in control animals (Fig. 3). Moreover, NOS2 mRNA levels were markedly reduced in the IFN-γR−/− mice, suggesting that NOS2-mediated early clearance of HGE bacteria is dependent upon IFN-γ.

FIG. 1.

HGE infection in gp91phox−/− mice. At 8 and 12 days, splenocytes from HGE-infected gp91phox−/− and control mice (five animals per group) were isolated and pooled, and RT-PCR was performed using HGE-specific primers. One of three studies with similar results is shown.

FIG. 2.

HGE infection in NOS2−/− and control mice. At 8, 12, and 20 days, RT-PCR analysis using HGE specific primers was performed. Five mice were used in each group. One of four experiments with similar results is shown.

FIG. 3.

Effect of HGE infection on NOS2 levels in IFN-γR−/− mice. At 12 days splenocytes were analyzed for HGE bacteria and NOS2 induction by RT-PCR. One of three studies with similar results is shown.

Our results with the gp91phox−/− mice demonstrate that the course of granulocytic ehrlichiosis is unchanged in the absence of phox. This finding is in agreement with the in vitro observation that HGE bacteria actively inhibit the respiratory burst by downregulating gp91phox, thereby developing a local environment that has reduced levels of ROI (1). gp91phox−/− and control mice can, however, both clear the HGE bacteria after 12 days, suggesting that alternative mechanisms are responsible for the control of progressive infection. Our studies also demonstrate that NOS2 is important for the control of early infection because HGE can be readily detected at 12 days in NOS2−/− mice. Furthermore, IFN-γ is likely to play a role in the NOS2-mediated clearance of HGE bacteria because NOS2 levels were lower in IFN-γR−/− mice. Studies with Trypanosoma cruzi- and Listeria monocytogenes-infected IFN-γR−/− mice have shown similar reductions in NOS2 expression (8, 12). Nevertheless, in both gp91phox−/− and NOS2−/− mice, HGE bacteria were cleared at 12 or 20 days. This demonstrates that neither pathway is necessary for the eradication of persistent infection, perhaps because humoral and cellular responses to HGE can aid bacterial clearance. Indeed, antibodies to HGE bacteria are sufficient to partially protect mice from infection (20). Understanding the host immune response to HGE should enhance our understanding of the pathways that facilitate bacterial clearance and the evolution of HGE infection in mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 51873, the Brown-Coxe Fellowship Program, and a gift from SmithKline Beecham Biologicals. E. Fikrig is the recipient of a Clinical-Scientist Award in Translational Research from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

We thank C. Nathan (Cornell University Medical College) and J. S. Mudgett (Merck Research Laboratories) for providing us with the NOS2−/− mice and Debbie Beck for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerjee R, Anguita J, Roos D, Fikrig E. Infection by the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis prevents the respiratory burst by downregulating gp91phox. J Immunol. 2000;164:3946–3949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunnell J E, Trigiani E R, Srinivas S R, Dumler J S. Development and distribution of pathologic lesions are related to immune status and tissue deposition of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent-infected cells in a murine model system. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:546–550. doi: 10.1086/314902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christova I S, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Bulgaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:58–61. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark R A, Volpp B D, Leidal K G, Nauseef W M. Two cytosolic components of the human neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase translocate to the plasma membrane during cell activation. J Clin Investig. 1990;85:714–721. doi: 10.1172/JCI114496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinauer M C, Deck M B, Unanue E R. Mice lacking reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activity show increased susceptibility to early infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1997;158:5581–5583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dumler J S, Bakken J S. Human ehrlichiosis: newly recognized infections transmitted by ticks. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:201–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang F C. Perspectives series: host/pathogen interactions. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-related antimicrobial activity. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:2818–2825. doi: 10.1172/JCI119473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fehr T, Schoedon G, Odermatt B, Holtschke T, Schneemann M, Bachmann M F, Mak T W, Horak I, Zinkernagel R M. Crucial role of interferon consensus sequence binding protein, but neither of interferon regulatory factor 1 nor of nitric oxide synthesis for protection against murine listeriosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:921–931. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman J L, Nelson C, Vitale B, Madigan J E, Dumler J S, Kurtti T J, Munderloh U G. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heimer R, Andel A V, Wormser G P, Wilson M L. Propagation of granulocytic Ehrlichia spp. from human and equine sources in HL-60 cells induced to differentiate into functional granulocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:923–927. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.923-927.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodzic E, Ijdo J W, Feng S, Katavolos P, Sun W, Maretzki C H, Fish D, Fikrig E, Telford III S R, Barthold S W. Granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the laboratory mouse. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:737–745. doi: 10.1086/514236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holscher C, Kohler G, Muller U, Mossmann H, Schaub G A, Brombacher F. Defective nitric oxide effector functions lead to extreme susceptibility of Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice deficient in gamma interferon receptor or inducible nitric oxide synthase. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1208–1215. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1208-1215.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang S, Hendriks W, Althage A, Hemmi S, Bluethmann H, Kamijo R, Vilcek J, Zinkernagel R M, Aguet M. Immune response in mice that lack the interferon-gamma receptor. Science. 1993;259:1742–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.8456301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein M B, Miller J S, Nelson C M, Goodman J L. Primary bone marrow progenitors of both granulocytic and monocytic lineages are susceptible to infection with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1405–1409. doi: 10.1086/517332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacMicking J D, Nathan C, Hom G, Chartrain N, Fletcher D S, Trumbauer M, Stevens K, Xie Q W, Sokol K, Hutchinson N, et al. Altered responses to bacterial infection and endotoxic shock in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Cell. 1995;81:641–650. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQuiston J H, Paddock C D, Holman R C, Childs J E. The human ehrlichioses in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:635–642. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mott J, Barnewall R E, Rikihisha Y. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and Ehrlichia chaffeensis reside in different cytoplasmic compartments in HL-60 cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1368–1378. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1368-1378.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathan C. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: what difference does it make? J Clin Investig. 1997;100:2417–2423. doi: 10.1172/JCI119782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiloh M U, MacMicking J D, Nicholson S, Brause J E, Potter S, Marino M, Fang F, Dinauer M, Nathan C. Phenotype of mice and macrophages deficient in both phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Immunity. 1999;10:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun W, Ijdo J, Telford S R, Hodzic E, Zhang Y, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Immunization against the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a murine model. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:3014–3018. doi: 10.1172/JCI119855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Telford S R, III, Dawson J E, Katavolos P, Warner C K, Kolbert C P, Persing D H. Perpetuation of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a deer tick-rodent cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6209–6214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dobbenburgh A, van Dam A P, Fikrig E. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in western Europe. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1214–1216. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker D J, Dumler J S. Human monocytic and granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster P, Ijdo J, Chicone L H, Fikrig E. The agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis resides in an endosomal compartment. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:1932–1942. doi: 10.1172/JCI1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]