Abstract

Objective

To develop an interactive, living map of family medicine training and practice; and to appreciate the role of family medicine within, and its effect on, health systems across the world.

Composition of the committee

A subgroup of the College of Family Physicians of Canada’s Besrour Centre for Global Family Medicine developed connections with selected international colleagues with expertise in international family medicine practice and teaching, health systems, and capacity building to map family medicine globally. In 2022, this group received support from the Foundation for Advancing Family Medicine’s Trailblazers initiative to advance this work.

Methods

In 2018 groups of Wilfrid Laurier University (Waterloo, Ont) students conducted broad searches of relevant articles about family medicine in different regions and countries around the world; they conducted focused interviews and then synthesized and verified information, developing a database of family medicine training and practice around the world. Outcome measures were age of family medicine training programs and duration and type of family medicine postgraduate training.

Report

To approach the question of how delivery of the family medicine model of primary care can affect health system performance, relevant data on family medicine were collated—the presence, nature, duration, and type of training and role within health care systems. The website https://www.globalfamilymedicine.org now has up-to-date country-level data on family medicine practice around the world. This publicly available information will allow such data to be correlated together with health system outputs and outcomes and will be updated as necessary through a wiki-type process. While Canada and the United States only have residency training, countries such as India have master’s or fellowship programs, in part accounting for the complexity of the discipline. The maps also identify where family medicine training does not yet exist.

Conclusion

Mapping family medicine around the world will allow researchers, policy makers, and health care workers to have an accurate picture of family medicine and its impact using relevant, up-to-date information. The group’s next aim is to develop data on parameters by which performance in various domains can be measured across settings and to display these in an accessible form.

Résumé

Objectif

Élaborer une carte interactive et vivante de la formation et de la pratique en médecine familiale, et évaluer le rôle de la médecine familiale dans les systèmes de santé partout dans le monde, de même que ses effets sur ces systèmes.

Composition du comité

Un sous-groupe du Centre Besrour pour la médecine familiale mondiale du Collège des médecins de famille du Canada a établi des relations avec certains collègues internationaux ayant une expertise dans la pratique et l’enseignement de la médecine familiale, dans les systèmes de santé et dans le renforcement des capacités, pour cartographier mondialement la médecine familiale. En 2022, ce groupe a reçu une aide financière dans le cadre de l’initiative des grands pionniers de la recherche de la Fondation pour l’avancement de la médecine familiale pour poursuivre ces travaux.

Méthodes

En 2018, des groupes d’étudiants de l’Université Wilfrid Laurier à Waterloo (Ontario) ont effectué de vastes recensions d’articles pertinents concernant la médecine familiale dans différents pays et régions du monde; ils ont mené des entrevues ciblées, puis ils ont résumé et vérifié l’information pour élaborer une base de données sur la formation et la pratique de la médecine familiale dans le monde. Les paramètres de mesure étaient l’âge des programmes de formation en médecine familiale, ainsi que la durée et le type des formation postdoctorales en médecine familiale.

Rapport

Pour aborder la question de savoir comment le recours au modèle des soins primaires en médecine familiale peut influer sur le rendement du système de santé, des données pertinentes ont été colligées, notamment la présence, la nature, la durée, et le type de formation, et le rôle au sein des systèmes de santé. Le site Web https://www.globalfamilymedicine.org renferme maintenant des données actualisées, par pays, sur la pratique de la médecine familiale partout dans le monde. Ces renseignements publiquement accessibles permettront la corrélation de ces données avec les extrants et les résultats des systèmes de santé, et ils seront actualisés au besoin, au moyen d’un processus de type wiki. Alors que le Canada et les États-Unis n’ont que des programmes de résidence, des pays comme l’Inde ont des programmes de maîtrise ou de bourses de recherche, en partie pour tenir compte de la complexité de la discipline. La carte indique aussi les régions où la formation en médecine familiale n’existe pas encore.

Conclusion

La cartographie de la médecine familiale dans le monder permettra aux chercheurs, aux décideurs et aux travailleurs de la santé d’avoir un portrait exact de la médecine familiale et de ses impacts à l’aide de renseignements pertinents et actualisés. Le groupe a comme prochain objectif d’élaborer des données sur des paramètres pouvant permettre de mesurer le rendement dans divers domaines et dans divers contextes, et de les présenter sous une forme accessible.

Fifty years ago, the Declaration of Alma-Ata highlighted the importance of primary health care systems for patients around the world.1 Since then, there has been growing recognition that the key to improving population health is an integrated health system, effectively combining primary care and essential public health functions.2 Although Starfield and Shi provided evidence that training more primary care practitioners adds cost-effective value to health care systems, particularly in the Global North,2 several large studies failed to identify which individual primary care functions improve health outcomes and access to care.3-5 While there has been progress on measurement and quality indices,6-8 key stakeholders seek robust metrics to measure the growth of family medicine as a principal model of primary care. Key articles to visualize the reach and scope of family medicine9,10 now set the stage for more analytical work.

This project—the introduction of a global family medicine website—was launched in 2018 to respond to a growing need for a living, global, freely accessible platform combining quantitative and qualitative information as a tool for between-country and theme-based comparisons. In this article, we describe our methods and map some of the key lessons learned about family medicine from our work. A separate article will examine regional differences in more detail.

Composition of the committee

Since 2012, the Besrour Centre for Global Family Medicine of the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) has hosted the Besrour Conferences to reflect on its role in advancing the discipline of family medicine globally. The Besrour Papers Working Group, struck at the 2013 conference, was tasked with developing a series of articles to highlight the key issues, lessons learned, and outcomes emerging from the various activities of the Besrour collaboration. Members of this subgroup collaborated with international colleagues with expertise in teaching and family medicine capacity-building to develop this article and create an editable webpage (http://www.globalfamilymedicine.org) mapping global family medicine.

Methods

In 2018, a cohort of 7 Wilfrid Laurier University (Waterloo, Ont) health sciences students directed by one of the authors (N.A.) conducted a broad search of articles about family medicine training and practice around the world, using the search terms family medicine and family medicine training together with individual countries and regions.* Data sources included PubMed; Google Scholar; websites of colleges (eg, the CFPC, the World Organization of Family Doctors [WONCA] and its affiliates), societies, associations, and journals of family medicine; individual universities and hospitals; and other sources recommended by WONCA and CFPC contacts.

This study was approved by the Wilfrid Laurier University Research Ethics Board. After ethics approval, we recruited key informants including international associates of the Besrour Centre at the CFPC, WONCA leadership, authors of key articles, and colleagues of such contacts using snowball sampling. Interviews were conducted in person at the Besrour meeting at Family Medicine Forum or by telephone, Skype, Zoom, or WhatsApp. Some interviewees chose to remain anonymous, while most are identified on the project webpage.

We reviewed further articles suggested by experts, key informants, and interviewees using references from and citations of key articles. We then verified and consolidated the data, circling back to primary data sources and new interviewees suggested by our informants, validating these through our editorial board, who were widely recognized as leaders in the field. More recently, visitors to the project webpage have offered unsolicited and useful updates in line with our desire to create a living document.

To date, 60 family physician leaders, primary health care workers, and policy makers have been interviewed on 1 or more occasions. These informants are from a total of 39 countries in North America and Oceania (n=3), the Caribbean (n=1), Asia (n=9), Western Europe (n=7), Eastern Europe and the Balkans (n=5), Middle East (n=4), Latin America (n=4), and sub-Saharan Africa (n=6).

We also began to gather specific qualitative and quantitative data on health systems and health systems performance indicators from internationally recognized public sources.11

Report

Why does this matter? This article gives a bird’s eye view of family medicine internationally. We now have general comparative information on how family medicine has been developed, how family doctors are trained, and what they do around the world. Between-country comparisons are a rich source of data to examine the value of family medicine within health systems and could inform policy alternatives.

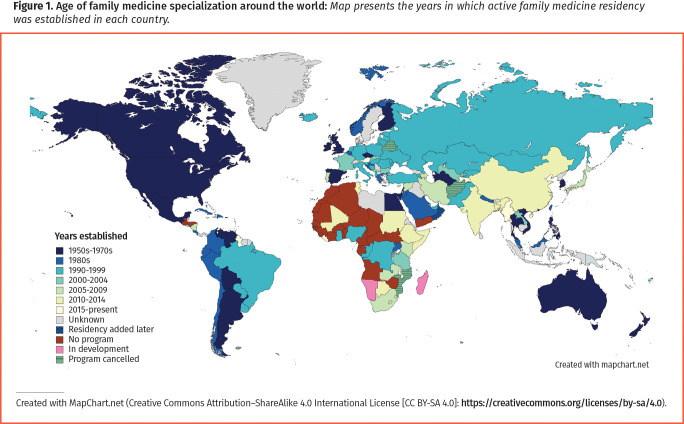

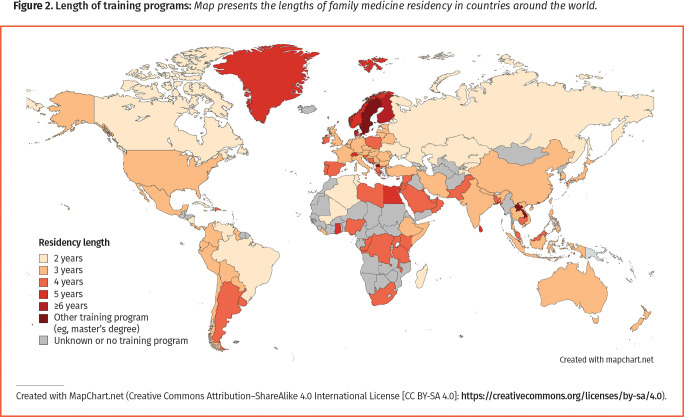

Establishment and length of training in family medicine. The maps (Figures 1 and 2) and Table 1 present information gathered about the establishment and type of postgraduate family medicine and specialization training used by each country. (In many countries, confusingly for North Americans, family medicine is termed general practice, particularly in the British Isles and former British colonies.) Quantitative data gathered included physician resources and residency programs and their age and duration, number of family medicine graduates, outcomes such as mortality and life expectancy, and primary care outputs such as immunization rates. Qualitative data are presented on the webpage as narratives, describing the role of family physicians within health systems and specifics about each country’s programs and their development.

Figure 1.

Age of family medicine specialization around the world: Map presents the year in which active family medicine residency was established.

Figure 2.

Length of training programs: Map presents the length of family medicine residency in countries around the world.

Table 1.

Types of postgraduate family medicine training in various countries and areas

| REGION | TYPE OF POSTGRADUATE TRAINING | NO PROGRAM |

|---|---|---|

| North America and Oceania |

|

NA |

| Asia |

|

North Korea, Mongolia, the Maldives, Uzbekistan, Macau (Hope Family Practice Residency Program) |

| Western Europe |

|

Monaco, Iceland |

| Eastern Europe and the Balkans |

|

Georgia, Kosovo, Belarus, Azerbaijan |

| Middle East and North Africa |

|

Algeria, Yemen |

| Sub-Saharan Africa |

|

Niger, Sierra Leone, Angola, Cameroon, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Mozambique (program cancelled) |

| Non-Hispanic Caribbean |

|

Saint Kitts and Nevis, Grenada, Belize |

| Latin America |

|

Honduras (in development), Guatemala (3-year master’s program) |

FM—family medicine, INGO—international non-governmental organization, NA—not applicable, PUST—postuniversity specialty training.

Discussion

While the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand have many long-standing family medicine programs, much of sub-Saharan Africa has none. Scandinavian countries have among the longest training programs while countries as diverse as Canada, Lebanon, Brazil, Mali, and Laos each have 2-year programs. However, Canada, unique among high-income countries for such short training, is planning on lengthening training to 3 years.12

Cross-jurisdictional data sources are a challenge to aggregate. The nomenclature around family medicine, including names of the degrees along the pathways of training, are variable. The MBBS, MBBCh, and MD degrees can each represent basic medical degrees, while MD can also be a graduate designation equivalent to a PhD in family medicine (namely in the United Kingdom) or specialization (as in India). The final year of medical school, clerkship (known as Praktisches Jahr in Germany), in some countries is known as an internship or service year. Several countries require 1 to 3 years of community work before postgraduate training in family medicine. Diplomas (eg, PGDFM or GDFM in Asia) usually require minimal coursework and are sometimes completed online, but a diploma in family medicine in India requires a 3-year residency. A fellow could have finished a year of coursework or have completed work beyond residency. A master’s degree may be a short route to designation while an MMed in Africa and some Asian countries may be 4 years and a superresidency including PhD-type research. Table 1 summarizes pathways outside of clinical residency including a multiplicity of other conduits (often in Asian countries), such as research and continuing education courses, to qualify for a family doctor designation.

As we assess the impact of family medicine, our data engender more questions. When evaluating the impact of training, do we include shorter and more informal training? Where family medicine is less established, representing a small proportion of primary care, should we explore only micro-level outputs (eg, comparing early graduates to other established primary care providers) to glean the value of training rather than seeking overarching population-based outcomes? We must determine appropriate quality indicators in terms of value of primary care.13 In settings where the family medicine model represents a substantial proportion of primary care, collaboration with other institutions may lead to the development of appropriate parameters to measure health system performance resulting from the impact of primary care models within and between countries, such as the “control knobs” framework.14

There are several limitations to our approach. Our data are dependent on the collective memory of our informants and our editorial board and our interpretation of the interviews, and they are complicated by the variation in official terminology. We may be unaware of nascent or dormant programs, particularly those not represented in the peer-reviewed literature, especially in emerging contexts. Thus, the development of our board and pool of regional experts and fostering of partnerships with WONCA leaders will be critical for the ongoing goal of this project.

Beasley et al asserted that a challenge of developing primary care research was strengthening academic departments, enhancing links to outside researchers, and increasing funding to ensure the relevance of research to vulnerable populations.15 Family medicine is still a young discipline in many parts of the world, and growing it also means growing its scholarship. This includes advancing the understanding of our discipline and assessing whether its myriad pathways and forms represent one of family medicine’s most appealing qualities: the ability to adapt to the needs of local populations.

Conclusion

Herein we have summarized descriptive data on the status of family medicine training and organization around the world. Despite its limitations (convenience sampling and the variability of nomenclature) such an approach is necessary, particularly in nascent or emerging contexts.

Mapping and visual display of information permits a bird’s eye view to quickly identify differences between contexts and points to gaps in data, and thus may assist in developing inferences and hypothesis generation to assist in collaborative learning and redirection of efforts of international partnerships where they may have the greatest yield.

This analysis of family medicine around the world expands our understanding of family medicine training at the country level, describing the evolution of a discipline. While no single pathway guarantees success, this process permits us to identify best practices across contexts to, for example, understand how to improve or expand residency training in countries such as Canada.

In the future, we will meticulously examine the regional pathways to the development and strengthening of family medicine around the world. One of the unalienable facts about our discipline is its variability and adaptability—a fact that makes the opportunity to study and understand it challenging but nonetheless important in this time of global collaboration.

More health performance indicators will be gathered and correlations sought. Parameters by which performance can be measured across settings will help evaluate how the delivery of the family medicine model of primary care can affect health systems and population health, hopefully leading to the improvement of health outcomes in areas without adequate care.

Acknowledgment

Dr Neil Arya was funded as Scholar in Residence at Wilfrid Laurier University from 2018 to 2020, and in 2021 by the Besrour Centre. In 2022, this group received support from the Foundation for Advancing Family Medicine’s Trailblazers initiative to advance this work. Our multitude of informants and our editorial board may be found on the project webpage: https://globalfamilymedicine.org/editorial-board. We particularly thank Dinusha Perera, Ian Tseng, Bruce Dahlman, and Robert Chin-see for updating data on multiple countries. We also acknowledge Wilfrid Laurier University students Althaf Azward, Calandra Li, and Isabella Aversa for their contributions to gathering information. We also thank Rifka Chamali and Sara Daou for their help with the preparation of the manuscript.

Editor’s key points

▸ Family medicine has been recognized by and integrated within health care systems in diverse contexts to varying degrees. Building on previously published work, this study aims to better understand family medicine on national levels throughout the world.

▸ While Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand have many long-standing family medicine programs, much of sub-Saharan Africa has none. Scandinavian countries have among the longest training programs while countries as diverse as Canada, Lebanon, Brazil, Mali, and Laos each have 2-year programs.

▸ Family medicine is still a young discipline in many parts of the world, and growing it also means growing its scholarship. This includes advancing the understanding of our discipline and assessing whether its myriad pathways and forms represent one of family medicine’s most appealing qualities: the ability to adapt to the needs of local populations.

Points de repère du rédacteur

▸ La médecine familiale a été reconnue et intégrée dans les systèmes de santé, et ce, dans divers contextes et à différents degrés. Misant sur des travaux publiés antérieurement, cette étude avait pour objectif de mieux comprendre la médecine famille à l’échelle nationale, dans le monde entier.

▸ Alors que le Canada, les États-Unis, le Royaume-Uni, l’Australie et la Nouvelle-Zélande ont tous des programmes de médecine familiale depuis longtemps, une bonne partie de l’Afrique subsaharienne n’en a pas. Les pays scandinaves comptent parmi ceux où les programmes de formation sont les plus longs, alors que dans des pays aussi diversifiés que le Canada, le Liban, le Brésil, le Mali et le Laos, le programme dure 2 ans.

▸ La médecine familiale est encore une jeune discipline dans de nombreuses régions du monde et, pour la développer, il faut aussi développer les connaissances à son sujet. Cela comporte de mieux faire comprendre notre discipline, et d’évaluer si ses trajectoires et ses formes multiples représentent l’une des plus attrayantes qualités de la médecine familiale : la capacité d’adaptation aux besoins des populations locales.

Footnotes

Initial searches were conducted with the aid of a university librarian through medical databases. Searches were scoped using MeSH terms and key words to narrow down the search for desired articles. Initial search strings were as follows:

What is family medicine: ((“family practice”[MeSH terms] OR “physicians, family”[MeSH terms]) AND “physician’s role”[MeSH terms]) AND “job description”[MeSH terms]

How primary care affects health systems performance: (((“primary health care”[MeSH terms] OR “physicians, primary care”[MeSH terms]) AND “quality of life”[MeSH terms]) AND ((“health status indicators”[MeSH terms] OR “global health”[MeSH terms]) OR “population health”[MeSH terms])) AND (“patient outcome assessment”[MeSH terms] OR “outcome and process assessment (health care)”[MeSH terms]).

Contributors

All authors contributed to the literature review and interpretation and to preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

References

- 1.Declaration of Alma-Ata. International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12 September 1978. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B, Shi L.. The medical home, access to care, and insurance: a review of evidence. Pediatrics 2004;113(4 Suppl):1493-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodyear-Smith F, van Weel C.. Account for primary health care when indexing access and quality. Lancet 2017;390(10091):205-6. Epub 2017 May 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2015 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators . Healthcare Access and Quality Index based on mortality from causes amenable to personal health care in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a novel analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2017;390(10091):231-66. Epub 2017 May 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howe A, Arya N.. Policy bite: big data – can we share our own? Brussels, Belgium: World Organization of Family Doctors; 2017. Available from: https://www.globalfamilydoctor.com/news/policybitebigdatacanweshareourown.aspx. Accessed 2023 Apr 6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The PHCPI conceptual framework. Primary Health Care Performance Initiative; 2018. Available from: https://improvingphc.org/phcpi-conceptual-framework. Accessed 2020 Jun 30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Operational framework for primary health care. Transforming vision into action. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund; 2020. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337641. Accessed 2022 Aug 9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arya N, Gibson C, Ponka D, Haq C, Hansel S, Dahlman B, et al. Family medicine around the world: overview by region. The Besrour Papers: a series on the state of family medicine in the world. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:436-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haq C, Ventres W, Hunt V, Mull D, Thompson R, Rivo M, et al. Family practice development around the world. Fam Pract 1996;13(4):351-6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robert Graham Center maps, data, and tools. Washington, DC: Robert Graham Center. Available from: https://www.graham-center.org/maps-data-tools.html. Accessed 2023 Apr 6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.General references. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University; 2019. Available from: https://globalfamilymedicine.org/new-page-1. Accessed 2023 Apr 17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preparing our future family physicians [news]. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2022. Available from: https://www.cfpc.ca/en/news/preparing-our-future-family-physicians. Accessed 2023 Apr 19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olde Hartman TC, Bazemore A, Etz R, Kassai R, Kidd M, Phillips RL Jr, et al. Developing measures to capture the true value of primary care. BJGP Open 2021;5(2):BJGPO.2020.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohammadibakhsh R, Aryankhesal A, Jafari M, Damari B.. Family physician model in the health system of selected countries: a comparative study summary. J Educ Health Promot 2020;9:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beasley JW, Starfield B, van Weel C, Rosser WW, Haq CL.. Global health and primary care research. J Am Board Fam Med 2007;20(6):518-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]