Abstract

Apostasia shenzhenica belongs to the subfamily Apostasioideae and is a primitive group located at the base of the Orchidaceae phylogenetic tree. However, the A. shenzhenica mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) is still unexplored, and the phylogenetic relationships between monocots mitogenomes remain unexplored. In this study, we discussed the genetic diversity of A. shenzhenica and the phylogenetic relationships within its monocotyledon mitogenome. We sequenced and assembled the complete mitogenome of A. shenzhenica, resulting in a circular mitochondrial draft of 672,872 bp, with an average read coverage of 122× and a GC content of 44.4%. A. shenzhenica mitogenome contained 36 protein-coding genes, 16 tRNAs, two rRNAs, and two copies of nad4L. Repeat sequence analysis revealed a large number of medium and small repeats, accounting for 1.28% of the mitogenome sequence. Selection pressure analysis indicated high mitogenome conservation in related species. RNA editing identified 416 sites in the protein-coding region. Furthermore, we found 44 chloroplast genomic DNA fragments that were transferred from the chloroplast to the mitogenome of A. shenzhenica, with five plastid-derived genes remaining intact in the mitogenome. Finally, the phylogenetic analysis of the mitogenomes from A. shenzhenica and 28 other monocots showed that the evolution and classification of most monocots were well determined. These findings enrich the genetic resources of orchids and provide valuable information on the taxonomic classification and molecular evolution of monocots.

Keywords: Apostasia, mitochondrial genome, phylogenetic analysis, monocots

1. Introduction

Mitochondria are organelles that play a crucial role in plant productivity and development by being responsible for energy conversion, biosynthesis, and signal transduction [1]. The plant mitogenome is complex and diverse in terms of size, structure, number of repeats, and coding genes [2]. In addition, it has extensive horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and RNA-editing mechanisms that ensure mitochondrial function and stable gene expression [3,4]. Most seed plants inherit chloroplasts (cp) and mitochondria (mt) from their maternal parent. This genetic mechanism reduces the influence of paternal lines, making it easier to study genetics [5,6]. Thus, cp genomes and mitogenomes have been extensively analysed to understand taxon classification and evolution [7]. However, compared to plastid genomes, mitogenomes with lower evolutionary rates are more suitable for studying the phylogenetic relationships of families, orders, or higher taxonomic elements.

Monocots are one of the most diverse, ecologically important, and economically important terrestrial plant lineages with approximately 77 families and 85,000 species, accounting for 21% of angiosperms [8,9]. Despite their remarkable species diversity, only 30 monocots, including three orchids (Gastrodia elata, Platanthera zijinensis, P. guangdongensis) [10,11] mitogenomes have been published in the NCBI GenBank database due to the complexity of mitogenome structure and sequence, which limited the study and utilization of these excellent crops. At present, the phylogenetic relationships of monocots are mainly studied in cp genomes and mitochondrial gene segments, and the phylogenetic relationship of mitogenome is still unclear [12,13]. Therefore, it is extremely important to provide further evidence for the systematic relationship between monocot lineages using mitogenome.

Orchidaceae is the largest family of angiosperms and monocots with over 700 genera and approximately 28,000 species [14]. Apostasia is one of the two genera that form the subfamily Apostasioideae, which is a primitive group located at the base of the Orchidaceae phylogenetic tree [15]. Moreover, Apostasia has special morphology that demonstrates “primitive” traits similar to those of Curculigo crassifolia, are considered the closest to the “pseudoorchids” speculated by Darwin. This makes them ideal for studying orchids and phylogenetic evolution [16]. Therefore, we conducted a mitogenome study of A. shenzhenica to provide genetic resources for further studies on the evolution of Orchidaceae. Meanwhile, we combine the available mitogenomes of monocots to provide further evidence for the phylogenetic relationships of monocots.

In this study, we used second-generation sequencing techniques to de novo assemble the mitogenome of A. shenzhenica and systematically analysed gene content, repetitive sequences, selective pressure, and RNA editing sites. We investigated the gene transfer between the chloroplast and mitogenomes of A. shenzhenica. In addition, we explored the phylogenetic relationships among A. shenzhenica and 28 monocot species using the mitogenome, which provided valuable information on the taxonomic classification, molecular evolution, and breeding of monocots.

2. Results

2.1. Mitogenome Structure and Gene Content

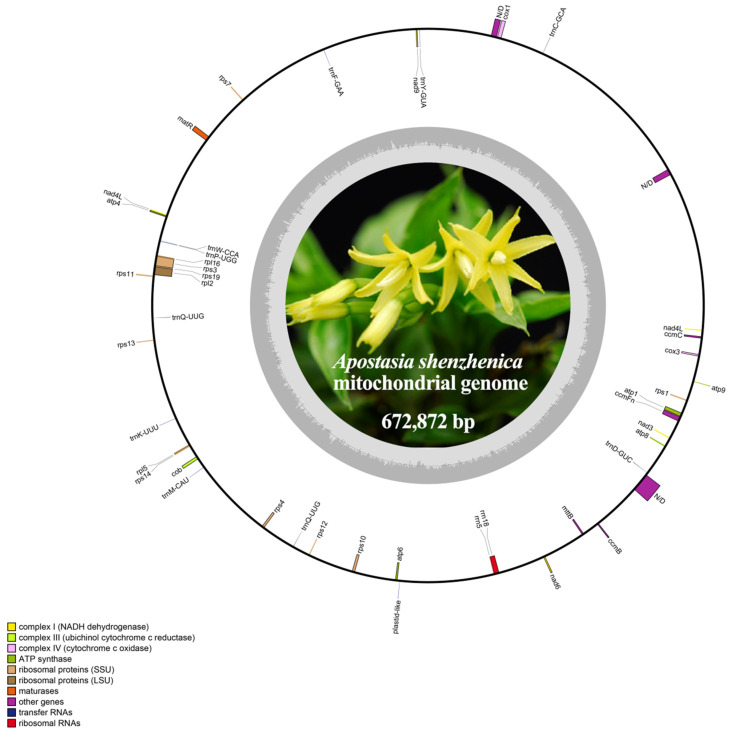

The genome sequence of A. shenzhenica was uploaded to GenBank (accession number: OQ645347). We assembled a 672,872 bp length mitogenome of A. shenzhenica using 18 Gb Illumina sequencing data and manually displayed a circular structure (Figure 1). The nucleotide composition of the mitogenome was 27.8% A, 27.8% T, 22.3% G, 22.1% C, and 44.4% GC. In addition, we identified 54 mitochondrial genes in the A. shenzhenica mitogenome, including 36 protein-coding genes, two rRNA genes, and 16 tRNA genes (Table 1 and Table S1). Protein-coding genes (PCGs) accounted for 4.21% of the total mitogenome, whereas tRNA and rRNA genes accounted for only 0.17% and 0.31%, respectively. The rest of the mitogenome contained noncoding sequences, such as introns, intergenic spacers, and potential pseudogenes. There were 57 repeat pairs with a length of >50 bp, occupying 1.38% (9298 bp) of the mitogenome. Interestingly, two copies of nad4L genes were detected.

Figure 1.

Map of the mitogenome of A. shenzhenica. The genes inside and outside the circle are transcribed in the clockwise and counterclockwise directions, respectively. Genes belonging to different functional groups are shown in different colors. The innermost darker gray corresponds to GC-content, while the lighter gray corresponds to AT content.

Table 1.

Genes present in the mitogenome of A. shenzenica.

| Group of Genes | Name | Length | Start Codon | Stop Codon | Amino Acids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex V (ATP synthase) | atp1 | 1524 | ATG | TGA | 507 |

| atp4 | 588 | ATG | TAA | 195 | |

| atp6 | 1194 | ATG | TAA | 398 | |

| atp8 | 474 | ATG | TAA | 157 | |

| atp9 | 225 | ATG | TAA | 75 | |

| Cytochrome c biogenesis | ccmB | 621 | ATG | TGA | 206 |

| ccmC | 762 | ATG | TGA | 254 | |

| ccmFc * | 1389 | ATG | TAA | 463 | |

| ccmFn | 1857 | ATG | TAA | 619 | |

| Complex III (ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase) | cob | 1173 | ATG | TAG | 390 |

| Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) | cox1 | 1584 | ATG | TAA | 527 |

| cox3 | 798 | ATG | TGA | 265 | |

| Maturases | matR | 1926 | ATG | TAG | 641 |

| Transport membrane protein | mttB | 453 | TTG | TAA | 150 |

| Complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) | nad1 | 384 | ATT | TAG | 128 |

| nad3 | 360 | ATG | TAA | 120 | |

| nad4L(2) | 264 | ATG | TAA | 88 | |

| nad5 * | 1452 | ATG | TGA | 483 | |

| nad6 | 618 | ATG | TAA | 205 | |

| nad7 **** | 1185 | ATG | TAG | 392 | |

| nad9 | 573 | ATG | TAA | 190 | |

| Ribosomal proteins (LSU) | rpl2 * | 1572 | ATG | TAG | 522 |

| rpl5 | 555 | ATG | TAA | 184 | |

| rpl16 | 558 | ATG | TAA | 185 | |

| Ribosomal proteins (SSU) | rps1 | 525 | ATG | TAA | 174 |

| rps3 * | 1743 | ATG | TAG | 579 | |

| rps4 | 1032 | ATG | TAA | 343 | |

| rps7 | 447 | ATG | TAA | 149 | |

| rps10 * | 339 | ATG | TAA | 113 | |

| rps11 | 516 | ATG | TAA | 172 | |

| rps12 | 378 | ATG | TGA | 126 | |

| rps13 | 351 | ATG | TGA | 116 | |

| rps14 | 324 | ATG | TAG | 107 | |

| rps19 | 561 | ATG | TGA | 186 | |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn5 | 117 | - | - | - |

| rrn18 | 1994 | - | - | - | |

| Transfer RNAs | tRNA-Phe | 73 | - | - | - |

| tRNA-Lys | 75 | - | - | - | |

| tRNA-Gln | 71 | - | - | - | |

| tRNA-Thr | 71 | - | - | - | |

| tRNA-Met a | 74 | - | - | - | |

| tRNA-Cys | 73 | - | - | - | |

| trnC-GCA | 71 | - | - | - | |

| trnD-GUC a | 74 | - | - | - | |

| trnF-GAA a | 73 | - | - | - | |

| trnK-UUU | 73 | - | - | - | |

| trnM-CAU a | 73 | - | - | - | |

| trnP-UGG a | 74 | - | - | - | |

| trnQ-UUG | 72 | - | - | - | |

| trnQ-UUG | 72 | - | - | - | |

| trnW-CCA | 74 | - | - | - | |

| trnY-GUA | 83 | - | - | - |

Note: Numbers after gene names are the number of copies. The superscripts * and **** represent one and four introns contained, respectively. The superscripts a indicates the chloroplast-derived genes.

The depth of coverage across the entire mitogenome was relatively even, indicating the continuity of our assembly (Figure 1). Overlaps and intervals exist between adjacent genes in the mitogenome. We identified three overlapping sequences. Overlapping sequences were located between rp15 and rps14, rp116 and rps3, and rps19 and rps3. A total of 50 gene spacer regions with lengths ranging from 4 to 67,130 bp were identified. The largest spacer region was between nad5 and trnC-GCA, with a length of 67,130 bp. Furthermore, most PCGs of A. shenzhenica have no introns; six of the annotated genes contained introns, five of them (nad5, ccmFc, rpl2, rps3 and rps10) included an intron and nad7 had four (Table 1). Analysis of the whole mitogenome sequence has putative group II intron segments near each exon. Then, we set the minimum size to 200 bp in Geneious and discovered that these genes have one or more ORFs with unknown function, laying in the middle region between its exons. For example, ccmFc intron has two ORFs with complete start and stop codons.

Except for mttB, which used TTG, most protein-coding genes used ATG as the start codon. In several higher plant mitogenomes, the start codons of the mttB gene were unclear [17,18]. The stop codons used in A. shenzhenica mitochondrial PCGs were TAA (19 genes; atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9, ccmFc, ccmFn, cox1, mttB, nad3, nad4L, nad6, nad9, rpl5, rpl16, rps1, rps4, rps7, rps10, and rps11), TAG (6 genes; cob, matR, nad7, rpl2, rps3, and rps14), and TGA (9 genes; atp1, ccmB, ccmC, cox3, nad5, rps12, rps13, rps19, and psaJ).

2.2. Codon Usage Analysis of PCGs

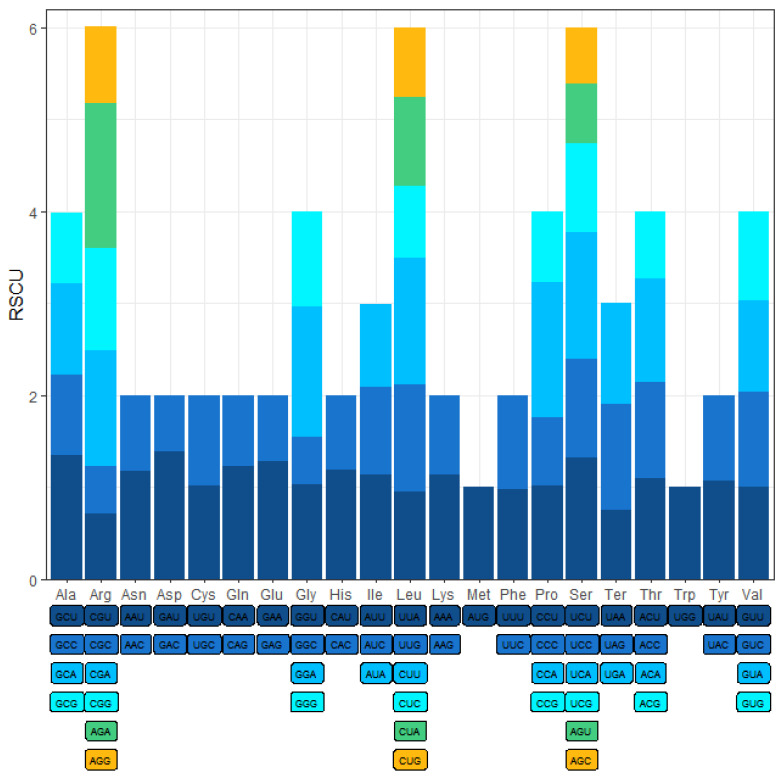

To ATG was the most frequent start codon for 36 protein-coding genes (Table 1); the mttB gene was an exception with the initiating codon TTG. Three stop codons (TAA, TAG, and TGA) were identified. These results indicated that RNA editing from C to U does not occur at the start or stop codon. The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values of A. shenzhenica are displayed in Figure 2. The results showed that the 36 protein-coding gene regions had 9379 codons, excluding termination codons (Table 2). The most frequently used codons were UUC and UUU (for Phenylalanine; Phe) and CUU (for leucine; Leu), whereas CGU and CGC (for Serine; Ser) and GGC (for tryptophan; Trp) were rarely found. This may explain the negative base skew (AT, GC) of the PCGs.

Figure 2.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) in A. shenzhenica mitogenome. Codon families are shown on the x-axis. RSCU values are the number of times a particular codon is observed relative to the number of times that codon would be expected for a uniform synonymous codon usage.

Table 2.

Relative synonymous codon usage and codon numbers of A. shenzhenica mitochondrial PCGs.

| AA | Codon | No. | RSCU | AA | Codon | No. | RSCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phe | UUU | 276 | 0.92 | Ser | UCU | 196 | 1.45 |

| UUC | 327 | 1.08 | UCC | 145 | 1.07 | ||

| Leu | UUA | 135 | 0.71 | UCA | 186 | 1.38 | |

| UUG | 233 | 1.23 | UCG | 140 | 1.04 | ||

| CUU | 233 | 1.23 | Pro | CCU | 95 | 0.75 | |

| CUC | 172 | 0.91 | CCC | 95 | 0.75 | ||

| CUA | 201 | 1.06 | CCA | 190 | 1.5 | ||

| CUG | 166 | 0.87 | CCG | 126 | 1 | ||

| Ile | AUU | 185 | 0.96 | Thr | ACU | 76 | 0.88 |

| AUC | 205 | 1.06 | ACC | 83 | 0.97 | ||

| AUA | 189 | 0.98 | ACA | 98 | 1.14 | ||

| Met | AUG | 214 | 1 | ACG | 87 | 1.01 | |

| Val | GUU | 133 | 0.97 | Ala | GCU | 92 | 1.14 |

| GUC | 141 | 1.03 | GCC | 64 | 0.8 | ||

| GUA | 132 | 0.96 | GCA | 90 | 1.12 | ||

| GUG | 142 | 1.04 | GCG | 76 | 0.94 | ||

| Tyr | UAU | 133 | 0.93 | Cys | UGU | 115 | 0.95 |

| UAC | 154 | 1.07 | UGC | 128 | 1.05 | ||

| Ter | UAA | 156 | 0.81 | Ter | UGA | 199 | 1.03 |

| UAG | 226 | 1.17 | Trp | UGG | 218 | 1 | |

| His | CAU | 120 | 0.98 | Arg | CGU | 56 | 0.55 |

| CAC | 126 | 1.02 | CGC | 58 | 0.57 | ||

| Gln | CAA | 159 | 0.99 | CGA | 117 | 1.14 | |

| CAG | 161 | 1.01 | CGG | 125 | 1.22 | ||

| Asn | AAU | 160 | 1.1 | Ser | AGU | 62 | 0.46 |

| AAC | 131 | 0.9 | AGC | 81 | 0.6 | ||

| Lys | AAA | 245 | 1.1 | Arg | AGA | 168 | 1.64 |

| AAG | 200 | 0.9 | AGG | 91 | 0.89 | ||

| Asp | GAU | 118 | 1.22 | Gly | GGU | 104 | 0.89 |

| GAC | 76 | 0.78 | GGC | 57 | 0.49 | ||

| Glu | GAA | 227 | 1.12 | GGA | 163 | 1.39 | |

| GAG | 178 | 0.88 | GGG | 144 | 1.23 |

9379 codons in A. shenzhenica (used Universal Genetic code).

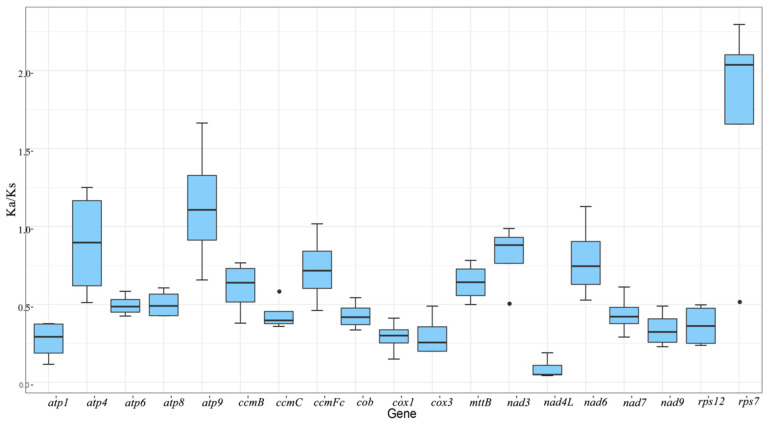

2.3. Substitution Rates of PCGs

The non-synonymous-to-synonymous substitution ratio (Ka/Ks) is important in genetics for assessing the magnitude and direction of natural selection acting on homologous genes among divergent species. It is commonly accepted that Ka/Ks indicates neutral evolution when it equals one, positive selection when it is greater than one, and negative selection when it is less than one.

To investigate the evolutionary rate of mitochondrial genes, we calculated the non-synonymous substitution rate (Ka) and synonymous substitution rate (Ks) for the 19 shared PCGs of A. shenzhenica against the Allium cepa, Gastrodia elata, Hemerocallis citrina, and Asparagus officinalis mitogenomes. As shown in Figure 3, the Ka/Ks ratios were much lower than 1 in the majority of protein-coding genes, indicating the stability of the protein function of these genes during evolution. In contrast, the Ka/Ks ratios of atp9 (1.13) and rps7 (1.72) were greater than 1, implying that these genes were subjected to positive selection. In particular, the Ka/Ks ratios of rps7 in A. shenzhenica and G. elata were significantly higher than 2(2.3), whereas those of H. citrina and A. officinalis were also 2.04 (Table S2), indicating that they may be very crucial for the evolution of A. shenzhenica. According to previous reports, small mitochondrial subunit proteins encoded by the rps7 gene are essential for various biological activities in eukaryotes, such as embryonic development, leaf formation, and reproductive tissue formation [19,20,21].

Figure 3.

The boxplots of Ka/Ks values among 19 PCGs in the A. shenzhenica with four different asparagales. The “X” axis shows the name of protein-coding genes, and the “Y” axis shows the Ka/Ks values. Black dots represent outliers.

Additionally, the ratio of the nad3 (0.81) gene was close to 1, indicating that it experienced neutral evolution because of the divergence of A. shenzhenica and four other Asparagales from its last common ancestor.

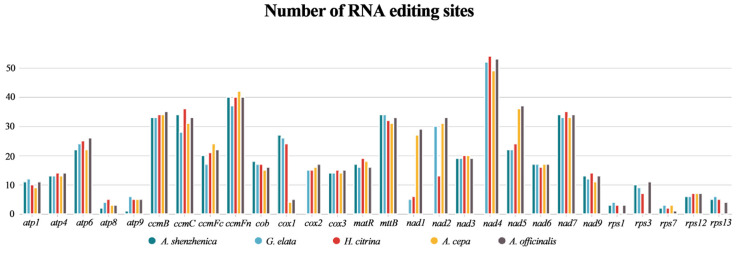

2.4. Prediction of RNA Editing Sites in PCGs

RNA editing refers to the process of altering genetic information at the mRNA level, including the deletion, insertion, or replacement of nucleotides. We used the web-based PREP-Mt tool to predict 416 RNA-editing sites and 100% C-to-U RNA editing in 28 PCGS of A. shenzhenica. Among them, there were 12 site conversions of CCT to TTT and two conversions of CCC to TTC. Moreover, the proportions were 39.9% (166 sites) for the projected first base location of the codon, 64.3% (255 sites) for the expected second base position, and none for the predicted third base position (Table S3). Instead of the lack of RNA editing at this site, the inadequacies of the PREP-Mt prediction methodology are likely to be responsible for the absence of projected RNA editing sites at the silencing site. Therefore, experimental techniques or proteomic data are required to identify RNA editing in silent editing locations [22,23].

The number of RNA editing sites varied greatly among the different genes, and the predicted RNA editing sites encoded by complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) and cytochrome c biogenesis genes (ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc, and ccmFn) were higher on average (Figure 4). Upon comparing the RNA editing sites of the five asparagine species, we found that the nad4 gene encoded the most RNA editing sites, whereas rps7 encoded the least.

Figure 4.

The distribution of RNA editing sites across the 28 PCGs of the mitogenomes of A. shenzhenica with four different asparagales.

2.5. Identification of Repeat Sequences

Repetitive sequences consist of simple sequence repeats (SSRs), tandem repeats, and dispersed repeats sequences. A total of 226 SSRs were discovered in A. shenzhenica mitogenome, including 57 (25.22%) monomers, 57 (25.22%) dimers, 39 (17.26%) trimers, 61 (26.99%) tetramers, 10 (4.42%) pentamers, and two (0.88%) hexamers. Almost 50% of the repetitions of 226 SSRs were either monomers or dimers. Additional analysis of the repetitive units of the SSRs revealed that G/C only occupied 8.8% of the monomers, whereas A/T accounted for 91.2% of the monomers. The high AT content in A. shenzhenica mononucleotide SSRs was consistent with the high AT content (55.6%) of the entire A. shenzhenica mitogenome. Table S4 shows the size and position of the hexamers and pentamers, all of which were found in intergenic spacers.

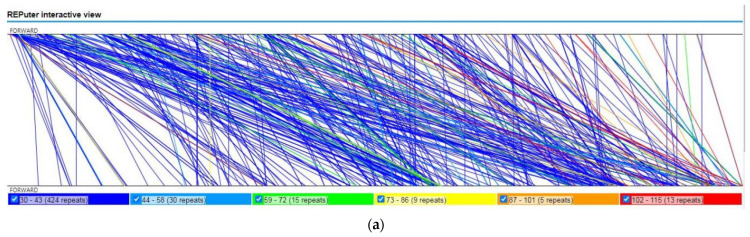

Tandem repeats, also known as satellite DNA, are core repeating units of 1–20 bases that are repeated numerous times. They exist extensively in eukaryotic and certain prokaryotic genomes [24]. The mitogenome of A. shenzhenica contained 13 tandem repeats with a matching degree of more than 95% and lengths ranging from 11 to 62 bp (Table S5). Dispersed repeats in A. shenzhenica mitogenome were observed using the REPuter program [25]. As a result, 979 repeats with lengths equal to or greater than 30 were found, 496 of which were straight, and 483 of which were inverted. The longest straight repetition was 115 bp, and the largest inverted repeat was 153 bp. Figure 5 shows the length distributions of the straight and inverted repeats. The 30–39 bp repetitions were found to be the most prevalent for both repeat types.

Figure 5.

The repeats sequences of A. shenzhenica mitogenome. (a) The synteny between the mitogenome and its forward copy showing the direct repeats. (b) The synteny between the mitogenome and its reverse complimentary copy, showing the inverted repeats. (c) The length distribution of reverse and inverted repeats in A. shenzhenica mitogenome. The numbers on the horizontal axis of the histogram represents the number of repetitions of designated lengths.

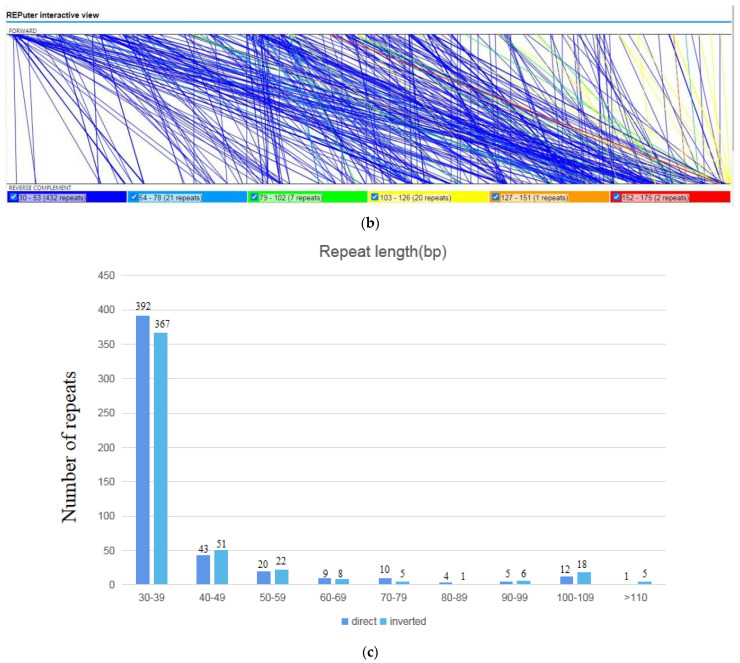

2.6. Characterization of A. shenzhenica Cpgenome Transfer into the Mitogenome

The A. shenzhenica mitogenome sequence was approximately 4.5 times longer than its cp genome (151,676 bp). The fragments ranged from 30 to 4725 bp in sequence identity with their original cp counterparts. A total of 44 fragments with a length of 34,456 bp migrated from the cp genome to the mitogenome of A. shenzhenica, accounting for 5.12% of the mitogenome (Figure 6). Five integrated annotated genes were located on these fragments, including four tRNA genes and one cp genome protein-coding gene, namely, trnM-CAU, trnD-GUC, trnP-UGG, trnF-GAA, and psaj. Our data also demonstrated that some genes, such as ycf2, accD, rrn16, psbB, rpoB, etc., migrated from the cp genome to the mitogenome. However, most of them lost their integrity during evolution, and only fragmentary sequences of these genes can presently be found in the mitogenome (Table 3). Through the chloroplast transfer event segments, we found that most tRNA genes were much more conserved than protein-coding genes, probably because they play important roles in the A. shenzhenica mitogenome.

Figure 6.

Transfer events in the cpgenome and mitogenome of A. shenzhenica. The blue and green outer arcs represent the mitogenome and cpgenome, respectively. Additionally, the inner arcs show the homologous DNA fragments. The scale is shown on the outer arcs, with intervals of 20 kb. The purple bars in the inner circle represent gene density.

Table 3.

Fragments transferred from chloroplast to mitochondria in A.shenzhenica.

| No | Alignment Length | % Identity | Gap Opens | CP Start | CP End | Mt Start | Mt End | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4725 | 98.836 | 11 | 132,666 | 137,368 | 626,018 | 621,308 | ycf2 a |

| 2 | 4725 | 98.836 | 11 | 88,264 | 92,966 | 621,308 | 626,018 | ycf2 a |

| 3 | 3976 | 99.623 | 3 | 56,121 | 60,093 | 28,471 | 32,446 | - |

| 4 | 2006 | 97.906 | 13 | 32,120 | 34,125 | 421,999 | 420,022 | accD a |

| 5 | 2081 | 94.522 | 14 | 86,296 | 88,371 | 495,204 | 493,213 | trnM-CAU, rpl23 a |

| 6 | 2081 | 94.522 | 14 | 137,261 | 139,336 | 493,213 | 495,204 | trnM- CAU, rpl23 a |

| 7 | 1373 | 97.815 | 3 | 36,982 | 38,349 | 631,371 | 632,733 | petA a |

| 8 | 1242 | 99.758 | 0 | 7898 | 9139 | 391,287 | 392,528 | rpoC2 a |

| 9 | 1219 | 99.918 | 0 | 116,093 | 117,311 | 670,487 | 671,705 | rrn23 a |

| 10 | 1076 | 92.937 | 11 | 24,885 | 25,947 | 184,256 | 183,219 | ndhc a |

| 11 | 746 | 100 | 0 | 121,777 | 122,522 | 671,706 | 672,451 | rrn16 a |

| 12 | 685 | 98.102 | 1 | 49,035 | 49,719 | 659,617 | 658,939 | psbB a |

| 13 | 704 | 95.313 | 3 | 3891 | 4589 | 487,500 | 486,810 | rpoB a |

| 14 | 731 | 94.391 | 14 | 38,847 | 39,548 | 174,249 | 173,520 | psbj a |

| 15 | 924 | 87.229 | 19 | 61,059 | 61,968 | 602,745 | 603,612 | trnD-GUC |

| 16 | 616 | 93.831 | 9 | 26,940 | 27,551 | 402,787 | 403,382 | trnM-CAU |

| 17 | 485 | 89.691 | 4 | 6392 | 6871 | 88,407 | 87,960 | rpoCI a |

| 18 | 461 | 89.588 | 12 | 41,276 | 41,728 | 311,079 | 311,516 | trnP-UGG |

| 19 | 382 | 93.455 | 6 | 38,370 | 38,751 | 174,332 | 174,696 | - |

| 20 | 355 | 92.113 | 0 | 33,561 | 33,915 | 264,149 | 264,503 | accD a |

| 21 | 263 | 94.677 | 1 | 2518 | 2780 | 116,752 | 116,501 | rpoB a |

| 22 | 260 | 93.462 | 3 | 6067 | 6325 | 400,045 | 399,792 | rpoCI a |

| 23 | 196 | 97.449 | 0 | 72,669 | 72,864 | 343,153 | 343,348 | psaA a |

| 24 | 887 | 74.183 | 37 | 121,923 | 122,786 | 531,470 | 532,328 | rrn18 b |

| 25 | 179 | 97.207 | 1 | 42,023 | 42,201 | 311,569 | 311,746 | psaj |

| 26 | 196 | 93.367 | 1 | 36,503 | 36,689 | 262,195 | 262,000 | cemA a |

| 27 | 311 | 83.28 | 10 | 23,453 | 23,757 | 210,056 | 209,764 | trnF-GAA |

| 28 | 148 | 93.919 | 1 | 7335 | 7482 | 670,488 | 670,348 | rpoCI a |

| 29 | 111 | 99.099 | 0 | 125,099 | 125,209 | 299,455 | 299,345 | - |

| 30 | 111 | 99.099 | 0 | 100,423 | 100,533 | 299,345 | 299,455 | rps12 a |

| 31 | 105 | 100 | 0 | 119,735 | 119,839 | 105 | 1 | trnA a |

| 32 | 105 | 100 | 0 | 119,163 | 119,267 | 420,021 | 419,917 | trnA a |

| 33 | 105 | 100 | 0 | 120,794 | 120,898 | 457,200 | 457,304 | trnI a |

| 34 | 105 | 100 | 0 | 121,777 | 121,881 | 619,103 | 618,999 | rrn16 a |

| 35 | 129 | 93.023 | 1 | 100,558 | 100,679 | 299,332 | 299,204 | rps12 a |

| 36 | 129 | 93.023 | 1 | 124,953 | 125,074 | 299,204 | 299,332 | - |

| 37 | 127 | 89.764 | 3 | 84,364 | 84,484 | 121,858 | 121,984 | pabA a |

| 38 | 92 | 85.87 | 5 | 99,245 | 99,332 | 392,626 | 392,537 | rps7 a |

| 39 | 92 | 85.87 | 5 | 126,300 | 126,387 | 392,537 | 392,626 | rps7 a |

| 40 | 50 | 100 | 0 | 270 | 319 | 468,564 | 468,613 | - |

| 41 | 50 | 96 | 0 | 38,799 | 38,848 | 174,326 | 174,277 | - |

| 42 | 41 | 97.561 | 0 | 100,397 | 100,437 | 299,481 | 299,441 | rps12 a |

| 43 | 41 | 97.561 | 0 | 125,195 | 125,235 | 299,441 | 299,481 | - |

| 44 | 30 | 100 | 0 | 48,483 | 48,512 | 293,196 | 293,167 | psbB a |

| Total | 34,456 |

Notes: Lowercase a indicates the partial sequence found in mitogenome. Lowercase b indicates the mt-derived genes.

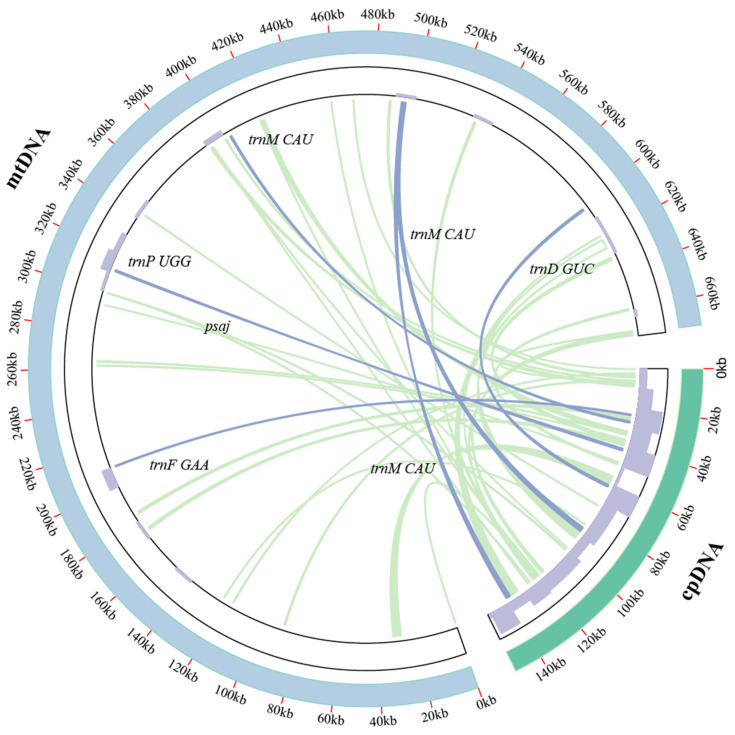

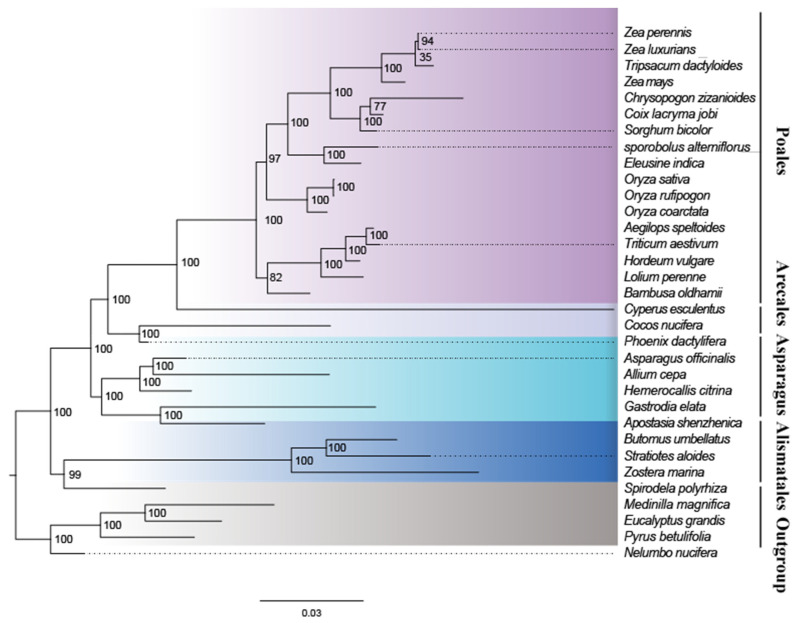

2.7. Phylogenetic Analysis and Gene Loss of Monocotyledon Mitogenomes

To understand the evolution of A. shenzhenica and the monocot mitogenome, we performed phylogenetic analyses on A. shenzhenica and 28 other monocots and four dicots (designated as the outgroup). Table S6 lists the accession numbers for the mitogenomes analysed in this study. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using an aligned data matrix comprising 28 conserved protein-coding genes from these species, as illustrated in Figure 7. The phylogenetic tree strongly supported the separation of monocots and dicotyledonous plants. Moreover, taxa from four orders (Alismatales, Asparagus, Arecales, and Poales) were well clustered. The clustering relationships of taxa in the phylogenetic tree in this study were consistent with those of previous studies examining the evolutionary relationships of these species.

Figure 7.

Maximum likelihood phylogenies of A. shenzhenica within 28 monocots species. The maximum likelihood tree was constructed based on the mitochondrial sequences of 28 conserved protein-coding genes. Colors indicate the families that the specific species belongs to.

As shown in Figure 7, the bootstrap values of most nodes were supported by more than 70%, and 25 nodes were supported by 100%. According to the maximum likelihood (ML) tree, A. shenzhenica and G. elata were classified into one clade (orchid) with a 100% bootstrap value, whereas this clade formed a sister relationship with the other four Asparagales. From the base group upward, the value for the separation of Alismatales from the clade composed of Asparagus, Arecales, and Poales was 100%. The bootstrap value for the separation of Asparagus and Arecales was 100%, and that of the separation of Arecales from the clade composed of Poales was also 100%.

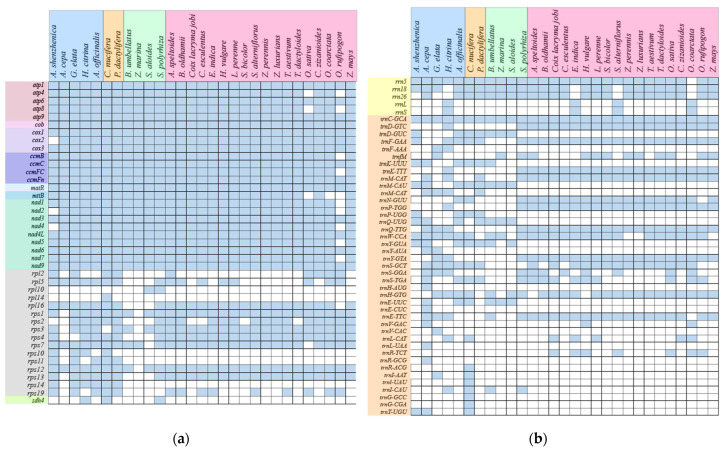

Furthermore, we compared the A. shenzhenica with 28 other monocots mitogenomes and discovered that genes composition of monocots mitogenomes differed. As illustrated in Figure 8a, the majority of mitochondrial protein-coding and rRNA genes are highly conserved, cox2 is only lost in the A. shenzhenica, and rpl10, rpl14, and sdh4 are lost in most monocots. In the evolutionary history of monocots, a considerable number of mitochondrial-derived tRNAs loss events occurred; only trnC-GCA is conservative (Figure 8b). However, most of the tRNAs in Poales are regularly retained.

Figure 8.

Comparison of genes contents between of A. shenzhenica and other 28 monocots species mitogenome. (a). The genes of CDS. (b). The genes of RNA. Blue-colored boxes represent active genes and blank boxes represent gene loss.

3. Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the A. shenzhenica Mitogenome

Most orchids exist as epiphytes in the wild. Orchid roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and seeds have adapted to a wide variety of habitat environments and have evolved unique structures and functions. The advent of rapid and cost-effective genome-sequencing technologies has accelerated our understanding of plant evolution. Mitochondria are the power stations of plants that produce the energy required to carry out life processes. Plant mitogenomes are more complex than the chloroplast genome because of factors, such as complex structures and size variations [10,18]. Our study is the first to report the A. shenzhenica mitogenome and its characterization. Compared with other species of Asparagales, the mitogenome size of A. shenzhenica is moderate. However, the mitogenome size is remarkably smaller than that of G. elata [10], but larger than those of A. cepa, A. officinalis, and H. citrina [26,27,28]. The overall GC content is 44.4%, which is similar to that of other species of Asparagales (42.9–46.7%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of features in A. shenzhenica and other asparagopsis mitogenomes.

| Feature | A. shenzhenica | G. elata | A. cepa | A. officinalis | H. citrina |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 672,872 | 1,339,825 | 536,617 | 492,062 | 468,462 |

| GC content (%) | 44.4 | 44.6 | 42.9 | 43.4 | 45.2 |

| Length of protein coding region (%) | 28,332 (4.21%) | 32,801 (2.45%) | 25,203 (4.70%) | 31,749 (6.45%) | 38,758 (8.27%) |

| Length of tRNA genes (%) | 1176 (0.17%) | 1479 (0.11%) | 1871 (0.35%) | 1284 (0.26%) | 1282 (0.27%) |

| Length of rRNA genes (%) | 2111 (0.31%) | 2085 (0.16%) | 5100 (0.95%) | 10,981 (2.23%) | 7300 (1.56%) |

| Number of protein coding genes | 36 | 39 | 27 | 36 | 45 |

| Number of rRNA genes | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| Number of tRNA genes | 16 | 20 | 25 | 17 | 17 |

| Total genes | 54 | 62 | 55 | 59 | 66 |

| Length of >50 repeats (%) | 9298 (1.38%) | 127,244 (9.50%) | 310,943 (57.95%) | 50,419 (10.25%) | 132,110 (28.20%) |

| Longest repeat (bp) | 175 | 1773 | 31,800 | 12,365 | 16,460 |

| Accession Numbers | OQ645347 | MF070084-102 | AP018390 | MT483944 | MZ726801-3 |

Most sequences in the A. shenzhenica mitogenome are non-coding, and protein-coding genes account for 4.21%. Compared to most mitogenomes, protein-coding genes are 2.45% in G. elata, 3.31% in C. comosum, 4.70% in A. cepa, 6.45% in A. officinalis, and 8.27% in H. citrina, which is mainly due to the frequent recombination of repeated sequences in the mitogenome and the integration of foreign sequences during evolution.

3.2. Repeat Sequences, Ka/Ks, and RNA Editing Sites Length of Protein Coding Region (%)

Mitochondrial repeat sequences are essential for intermolecular recombination because they can contribute to extreme mitogenome sizes and structural differences [29,30]. The mitogenome of A. shenzhenica contains 113 repeat sequences longer than 50 bp, accounting for 1.38% of its genome. The maximum length is 175 bp and does not contain medium or large repeats. We suspect that recombination is less frequent in the A. shenzhenica mitochondrion. Moreover, repeats are poorly conserved in plant mitogenomes, even within the same family. As shown in Table 4, the total length of the repeats ranges from 9298 bp (1.38%) in A. shenzhenica to 310,943 bp (57.95%) in A. cepa. Interestingly, the mitogenome of A. cepa is 536,617 bp, and that of A. shenzhenica is 672,872 bp, suggesting that the size of the genome is determined not only by the expansion of repeated sequences, but also by other factors. This mtDNA heteroplasmy may provide more genetic resources for evolutionary selection [31], imparting ecological and genetic fitness to A. shenzhenica during its evolution.

Ka/Ks analysis and comparison of mitogenome features provide a comprehensive understanding of plant mitogenome evolution. In the present study, atp4, atp9, ccmFc, and nad6 undergo positive selection during evolution. Different plant species under conditions involving positive selection pressure during evolution, including atp8, ccmFn, matR, ccmB and mttB, which have also been reported [5,7,22,32]. However, the A. shenzhenica mitogenome is conserved, and most of the PCGs have undergone neutral and negative selection compared to other Asparagales species. In general, most of the results of this investigation are consistent with the previous reports. In addition, nad4L shows the lowest Ka/Ks ratio among A. shenzhenica mitochondrial genes. The nad4L Ka/Ks ratio is < 0.5 in different species [33]. There are two copies of nad4L in A. shenzhenica, and we suspect that this gene plays an important role in A. shenzhenica.

RNA editing, a post-transcriptional mechanism that occurs in higher plant chloroplasts and mitogenomes, aids in protein folding [34,35]. Each organelle is highly lineage-specific in terms of the frequency and the type of RNA editing [36,37,38]. In the earlier studies, Oryza sativa exhibited 491 RNA editing sites in 34 genes [39], and Phaseolus vulgaris showed 486 RNA editing sites in 31 genes [40]. In the present study, we predicted RNA editing sites in 28 PCGs common to G. elata, H. citrina, A. cepa, and A. officinalis mitogenomes. As shown in Figure 4, the number of RNA editing sites predicted in mitogenomes of different Asparagales species is very conserved, from 416 sites in A. shenzhenica to 552 sites in Asparagus officinalis. Of these, 514 are found in G. elata, of which 347 are shared with A. shenzhenica. These results suggest that they share highly conserved PCGs.

3.3. DNA Fragment Transfer Events

Intracellular gene transfer between different genomes (mitochondria, nuclei, and chloroplasts) has been widely examined via sequencing analyses [41,42]. Prior studies have found high levels of nuclear DNA translocation to organelles in monocots [43,44]. Nuclear NDH complex-related genes are lost, along with cp-ndh genes in orchids [45]. However, the cp-ndh gene in A. shenzhenica is not completely lost, and only ndhH, ndhE, ndhF, and ndhG are lost; whether it is transferred to a nuclear gene is unknown.

Horizontal gene transfer from chloroplasts to mitochondria has been reported several times. However, the length and number of transfer fragments vary significantly between species [7]. In our study, we identified 44 fragments that have been transferred from the cp genome (22.72% of the cp genome) to the mitogenome. These included five integrated genes, (four tRNA genes and one protein-coding gene, psaJ). Interestingly, we found that chloroplast transfer fragments were randomly scattered across every region of the chloroplast and not just in the repetitive regions [7].

3.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

A phylogenetic tree based on the entire mitochondrial protein-coding gene sequence was constructed to explore the evolutionary relationships between mitochondria in monocots. Phylogenetic analysis using the mitogenome shows results congruent with those of Petersen [4]. The evolutionary relationships among the four classes of monocots lineages are well resolved in this study. Our study supports mitogenomics as an informational tool to address the systematic relationships among families, orders, or higher taxonomic levels of angiosperms. However, the phylogenetic differentiation of some nodes, such as Zea, Tripsacum dactyloides, chrysopogon zizanioides, and coix lacrymajobi is not well resolved in the present analysis. This suggests that they may have a close genetic relationship or ancestral relationship. An extended sampling of more representative monocots plants, as well as comparisons of mitogenome phylogenetic with plastid DNA, nuclear DNA, and morphology data, are necessary to confidently establish the phylogenetic relationships of monocots.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Sequencing

We obtained plant materials of A. shenzhenica from the Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China. A total DNA of A. shenzhenica was isolated as previously reported [46]. mtDNA was extracted from purified mitochondria using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide technique [47]. For A. shenzhenica, a 250-bp paired-end library and a 3-kb mate-pair library were produced and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform using two alternative techniques. Trimmomatic v0.36 was used to remove low-quality bases and adaptor sequences from the raw Illumina reads [48].

4.2. Mitogenome Assembly and Annotation

We used SPAdes v3.10.1 for de novo assembly of the A. shenzhenica mitogenome [49]. Furthermore, we ran many SPAdes runs with different k-mer values (k = 77, 101, and 127) and utilized QUAST [50] to evaluate and select 127 as the optimal k-mer number for multiple assembly. Finally, we identified only one candidate mitochondrial scaffold, which can be mapped as a circular molecule with a pair of direct repeats at its both ends. Sanger sequencing was used to confirm the connector and filled the seven remaining gaps in this scaffold.

The Geneious [51] program was used to predict mitochondrial protein-coding genes. tRNAscan-SE v1.21 [52] and RNAmmer 1.2 Server [53] were used to identify the tRNA and rRNA genes, respectively. The start/stop codons and exon-intron boundaries of genes were manually corrected. ORFfinder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/, accessed on 30 June 2022) was used to examine ORFs longer than 300 bp inside intergenic sequences, and BlastN [54] was used to identify repetitions with more than 95% identity in each mitogenome. We used a shell script to analyze the Guanine-Cytosine (GC) content and Circos v0.69 to show the circular physical map of all mitogenomes [55]. The RNAweasel program was used to predict Group II introns.

In codon usage analysis, codonW v1.4.4 was used to determine relative synonymous codon use (RSCU) of selected protein-coding genes in the mitogenome [56]. Then, the R package ggplot2 was used for plotting.

4.3. Selective Pressure Analysis

The nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates of each PCG between A. cepa, G. elata, H. citrina, and A. officinalis were estimated. MEGA 6.0 was used to separately align orthologous gene pairs. DnaSP v5.10 was used to calculated Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks values [57]. The ggplot2 v3.3.6 was used to generate a boxplot of paired Ka/Ks values [58].

4.4. Prediction of RNA Editing Sites

The online PREP-Mt server suite (http://prep.unl.edu/, accessed on 10 October 2022) was used to anticipate potential RNA editing sites in A. shenzhenica PCGs and the other four Asparagales mitogenomes (A. cepa, A. officinalis, G. elata, and H. citrina). The cutoff value was set to 0.2 [23] to produce a more accurate prediction. A lower cut-off value predicts more real edit sites, but it increases the likelihood of misidentifying an unedited site as an edited one.

4.5. Analysis of Repeat Structure and Sequence

The MISAv2.1 (https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/, accessed on 1 September 2022) was used to assess the simple sequence repeats (SSRs) of the A. shenzhenica mitogenome [59], with the motif size of one to six nucleotides and thresholds of 10, 5, 4, 3, 3 and 3, respectively. Tandem Repeats Finder v4.09 program [24] (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.submit.options.html, accessed on 1 September 2022) with default parameters was used to find tandem repeats with >6 bp repeat unit. Using the REPuter web server [25] (https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer, accessed on 5 September 2022) with the parameters “Hamming Distance 3, Maximum Computed Repeats 5000, Minimum Repeat Size 30,” dispersed repeats including forward, reverse, palindromic, and complementary repeats were discovered.

4.6. DNA Transfer between the Chloroplast and the Mitochondrion

The A. shenzhenica cp genome (MG772639.1) was obtained from the NCBI Organelle Genome Resources database. BLASTN was used to analyze sequence similarity between the cpgenome and the mitogenome in order to detect transferred DNA fragments, and the e-value cut-off was 1 × 10−5 [60]. The Circos module implemented in TBtools v1.105 was used to visualize the results [61,62,63].

4.7. Evaluating the Phylogenetic Mitochondrial Protein-Coding Genes

We downloaded the mitochondrial protein coding gene sequences of 29 different monocots and four dicotyledons and exported them as FASTA model files. Then, using the annotation module of the Geneious Prime v2022.0.1 platform, the CDS sequences of mitochondrial genes of 33 species were selected, and the exported the data as an excel sheet. Subsequently, the protein coding genes of 28 core protein coding genes (atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9, ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc, ccmFn, cob, cox1, cox2, cox3, matR, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, nad9, rps1, rps3, rps7, rps12, and rps13) were extracted from the mitogenomes of 33 species. Four species (Eucalyptus grandis, Medinella magnetica, Nelumbo nucifera, and Pyrus betulifolia) were used as outgroups. The protein-coding genes of 33 species were aligned by MEGA7.

Using the Concatenate Sequence module of Phylosuite v1.1.16 platform (ref), we converted the protein coding gene matrix into PHY tree format file. The (Maximum Likelihood, ML) phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using RAxML-HPC2 on XSEDE 8.2.12 in CIPRES science Gateway V 3.3 [64]. The ML tree was constructed by using the nucleotide replacement model GTRCAT, using the Bootstrap algorithm, with repeated calculation at 1000 times, and the other parameters were set to default [65]. The MP tree was constructed by heuristic search and the branch exchange algorithm (Tree-Bisection-Reconnection, TBR). All nucleotide characters are equally weighted, and the search was carried out by the method of arbitrary repetition of 1000 times. The reliability of the phylogenetic tree was analyzed by the bootstrap method of 1000 repetitions [66].

5. Conclusions

In this study, we assembled and annotated the A. shenzhenica mitogenome and performed a comprehensive analysis based on the annotated sequences. The draft mitogenome of A. shenzhenica was circular, with a length of 672,872 bp, and it comprised 54 genes, including 36 protein-coding genes, 16 tRNA genes, and two rRNA genes. Upon comparing the mitogenome and cp genome sequences, we discovered 44 fragments that were transferred from the cp genomes to the mitochondrial sequences. Furthermore, we analysed the A. shenzhenica mitogenome for codon usage, sequence repeats, RNA editing, and selection pressure. Moreover, the evolutionary status of the monocots was identified by phylogenetic analysis of the mitogenomes of A. shenzhenica and 28 other monocots. This study provides new insights into the diversity and evolution of orchid mitogenomes. We demonstrate mitochondrial evidence for A. shenzhenica and provide important insights into the evolution of orchids and monocots.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms24097837/s1.

Author Contributions

S.-R.L., Z.-J.L. and D.-K.L. design; validation; resources; database collecting; writing; preparation. S.-J.K., X.H. and M.-M.Z. analyzed data and edited preliminary drafts. X.-D.T. contributed to methods and several types of software. D.-Y.Z., C.-L.Z. and M.-J.Z. contributed to the visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The entire complete mitogenome sequence with gene annotation has been submitted in the NCBI GenBank under the accession number OQ645347. The sequence data utilized in this study can be found in Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Forestry Peak Discipline Construction Project of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (grant number 72202200205).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Picard M., Shirihai O.S. Mitochondrial signal transduction. Cell Metab. 2022;34:1620–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mower J.P., Sloan D.B., Alverson A.J. Plant mitochondrial genome diversity: The genomics revolution. In: Wendel J.F., Greilhuber J., Dolezel J., Leitch I.J., editors. Plant Genome Diversity Volume 1: Plant Genomes, Their Residents, and Their Evolutionary Dynamics. Springer; Vienna, Austria: 2012. pp. 123–144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang L. Male sterility in maize: A precise dialogue between the mitochondria and nucleus. Mol. Plant. 2020;13:1237. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen G., Seberg O., Davis J.I., Stevenson D.W. RNA editing and phylogenetic reconstruction in two monocot mitochondrial genes. Taxon. 2006;55:871–886. doi: 10.2307/25065682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng Y., He X., Priyadarshani S.V.G.N., Wang Y., Ye L., Shi C., Ye K., Zhou Q., Luo Z., Deng F., et al. Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of Suaeda glauca. BMC Genom. 2021;22:167. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07490-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace D.C., Singh G., Lott M.T., Hodge J.A., Schurr T.G., Lezza A., Elsas L.J., Nikoskelainen E.K. Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Science. 1988;242:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.3201231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni Y., Li J., Chen H., Yue J.W., Chen P., Liu C. Comparative analysis of the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of Saposhnikovia divaricata revealed the possible transfer of plastome repeat regions into the mitogenome. BMC Genom. 2022;23:570. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08821-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Givnish T.J., Evans T.M., Pires J.C., Sytsma K.J. Polyphyly and convergent evolution in Commelinales and Commelinidae: Evidence from rbcL sequence data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1999;12:360–385. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1999.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lughadha E.N., Govaerts R., Belyaeva I., Black N., Lindon H., Allkin R., Magill R.E., Nicolson N. Counting counts: Revised estimates of numbers of accepted species of flowering plants, seed plants, vascular plants and land plants with a review of other recent estimates. Phytotaxa. 2016;272:82–88. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.272.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan Y., Jin X., Liu J., Zhao X., Zhou J., Wang X., Wang D., Lai C., Xu W., Huang J., et al. The Gastrodia elata genome provides insights into plant adaptation to heterotrophy. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1615. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03423-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M.-H., Liu K.-W., Li Z., Lu H.-C., Ye Q.-L., Zhang D., Wang J.-Y., Li Y.-F., Zhong Z.-M., Liu X., et al. Genomes of leafy and leafless Platanthera orchids illuminate the evolution of mycoheterotrophy. Nat. Plants. 2022;8:373–388. doi: 10.1038/s41477-022-01127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen G., Seberg O., Yde M., Berthelsen K. Phylogenetic relationships of Triticum and Aegilops and evidence for the origin of the A, B, and D genomes of common wheat (Triticum aestivum) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2006;39:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Givnish T.J., Zuluaga A., Spalink D., Soto Gomez M., Lam V.K., Saarela J.M., Sass C., Iles W.J., de Sousa D.J.L. Leebens-Mack, J.; et al. Monocot plastid phylogenomics, timeline, net rates of species diversification, the power of multi-gene analyses, and a functional model for the origin of monocots. Am. J. Bot. 2018;105:1888–1910. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng Y.L., Zhou Z., Lan S.R., Liu Z.J. Cymbidium jiangchengense (Orchidaceae; Epidendroideae; Cymbidiinae), a new species from China: Evidence from morphology and DNA sequences. Phytotaxa. 2019;408:77–84. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.408.1.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y., Li Z., Hu Q., Zhai J., Liu Z., Wu S. Complete plastid genome of Apostasia shenzhenica (Orchidaceae) Mitochondrial DNA Part. B. 2019;4:1388–1389. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1591192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang G.Q., Liu K.W., Li Z., Lohaus R., Hsiao Y.Y., Niu S.C., Wang J.Y., Lin Y.C., Xu Q., Chen L.J., et al. The Apostasia genome and the evolution of orchids. Nature. 2017;549:379–383. doi: 10.1038/nature23897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y., Gu M., Liu X., Lin J., Jiang H., Song H., Xiao X., Zhou W. Sequencing and analysis of the complete mitochondrial genomes of Toona sinensis and Toona ciliata reveal evolutionary features of Toona. BMC Genom. 2023;24:58. doi: 10.1186/s12864-023-09150-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Q., Wang Y., Li S., Wen J., Zhu L., Yan K., Du Y., Ren J., Li S., Chen Z., et al. Assembly and comparative analysis of the first complete mitochondrial genome of Acer truncatum Bunge: A woody oil-tree species producing nervonic acid. BMC Plant Biol. 2022;22:29. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robles P., Quesada V. Emerging Roles of Mitochondrial Ribosomal Proteins in Plant Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:2595. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauro V.P., Edelman G.M. The Ribosome Filter Redux. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2246–2251. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.18.4739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schippers J.H.M., Mueller-Roeber B. Ribosomal composition and control of leaf development. Plant Sci. 2010;179:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bi C., Lu N., Xu Y., He C. Characterization and analysis of the mitochondrial genome of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) by comparative genomic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3778. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mower J. PREP-Mt: Predictive RNA editor for plant mitochondrial genes. BMC Bioinform. 2005;6:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao H., Kong J. Distribution characteristics and biological function of tandem repeat sequences in the genomes of different organisms. Zool. Res. 2005;26:555–564. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtz S., Choudhuri J.V., Ohlebusch E., Schleiermacher C., Stoye J., Giegerich R. REPuter: The manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao N., Hu Z., Miao J., Hu X., Lyu X., Fang H., Zhou Y.M., Mahmoud A., Deng G., Meng Y.Q., et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of bunching onion illuminates genome evolution and flavor formation in Allium crops. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:6690. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34491-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harkess A., Zhou J., Xu C., Bowers J.E., van der Hulst R., Ayyampalayam S., Mercati F., Riccardi P., McKain M.R., Kakrana A., et al. The asparagus genome sheds light on the origin and evolution of a young Y chromosome. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1279. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qing Z., Liu J., Yi X., Liu X., Hu G., Lao J., He W., Yang Z., Zou X., Sun M., et al. The chromosome-level Hemerocallis citrina Borani genome provides new insights into the rutin biosynthesis and the lack of colchicine. Hortic. Res. 2021;8:89. doi: 10.1038/s41438-021-00539-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo W., Grewe F., Fan W., Young G.J., Knoop V., Palmer J.D., Mower J.P. Ginkgo and Welwitschia Mitogenomes reveal extreme contrasts in gymnosperm mitochondrial evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1448–1460. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alverson A.J., Wei X., Rice D.W., Stern D.B., Barry K., Palmer J.D. Insights into the evolution of mitochondrial genome size from complete sequences of Citrullus lanatus and Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae) Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:1436–1448. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang J., Liu G., Zhao N., Chen S., Liu D., Ma W., Hu Z., Zhang M. Comparative mitochondrial genome analysis reveals the evolutionary rearrangement mechanism in Brassica. Plant Biol. 2016;18:527–536. doi: 10.1111/plb.12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia C., Li J., Zuo Y., He P., Zhang H., Zhang X., Wang B., Zhang J., Yu J., Deng H. Complete mitochondrial genome of Thuja sutchuenensis and its implications on evolutionary analysis of complex mitogenome architecture in Cupressaceae. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23:84. doi: 10.1186/s12870-023-04054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye N., Wang X., Li J., Bi C. Assembly and comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequence of an economic plant Salix suchowensis. Peer J. 2017;5:e3148. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bi C., Paterson A., Wang X., Xu Y., Wu D., Qu Y., Jiang A., Ye Q., Ye N. Analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii by comparative genomics approaches. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016;2016:5040598. doi: 10.1155/2016/5040598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H., Deng L., Jiang Y., Lu P., Yu J. RNA Editing Sites Exist in Protein-coding Genes in the Chloroplast Genome of Cycas taitungensis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011;53:961–970. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malek O., Lättig K., Hiesel R., Brennicke A., Knoop V. RNA editing in bryophytes and a molecular phylogeny of land plants. EMBO J. 1996;15:1403–1411. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00482.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinhauser S., Beckert S., Capesius I., Malek O., Knoop V. Plant Mitochondrial RNA Editing. J. Mol. Evol. 1999;48:303–312. doi: 10.1007/PL00006473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Notsu Y., Masood S., Nishikawa T., Kubo N., Akiduki G., Nakazono M., Hirai A., Kadowaki K. The complete sequence of the rice (Oryza sativa L.) mitochondrial genome: Frequent DNA sequence acquisition and loss during the evolution of flowering plants. Mol. Gen. Genomics. 2002;268:434–445. doi: 10.1007/s00438-002-0767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong S., Zhao C., Chen F., Liu Y., Zhang S., Wu H., Zhang L., Liu Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of the early flowering plant Nymphaea colorata is highly repetitive with low recombination. BMC Genom. 2018;19:614. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4991-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timmis J.N., Ayliffe M.A., Huang C.Y., Martin W. Endosymbiotic gene transfer: Organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrg1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hazkani-Covo E., Zeller R.M., Martin W. Molecular poltergeists: Mitochondrial DNA copies (numts) in sequenced nuclear genomes. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park S., Ruhlman T.A., Sabir J.S.M., Mutwakil M.H.Z., Baeshen M.N., Sabir M.J., Baeshen N.A., Jansen R.K. Complete sequences of organelle genomes from the medicinal plant Rhazya stricta (Apocynaceae) and contrasting patterns of mitochondrial genome evolution across asterids. BMC Genom. 2014;15:405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin C.S., Chen J.J., Chiu C.C., Hsiao H.C., Yang C.J., Jin X.H., Leebens-Mack J., de Pamphilis C.W., Huang Y.T., Yang L.H., et al. Concomitant loss of NDH complex-related genes within chloroplast and nuclear genomes in some orchids. Plant J. 2017;90:994–1006. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao C., Wu C., Zhang Q., Zhao X., Wu M., Chen R., Zhao Y., Li Z. Characterization of chloroplast genomes from two Salvia medicinal plants and gene transfer among their mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes. Front. Genet. 2020;11:574962. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.574962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson G., Seberg O., Davis J.I., Goldman D.H., Stevenson D.W., Campbell L.M., Michaelangeli F.A., Specht C.D., Chase M.W., Fay M.E., et al. Mitochondrial Data in Monocot Phylologenetics. Aliso A J. Syst. Florist. Bot. 2006;22:52–62. doi: 10.5642/aliso.20062201.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L., Liu Z. Apostasia shenzhenica, a new species of Apostasioideae (Orchidaceae) from China. Plant Sci. J. 2011;29:38–41. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1142.2011.10038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doyle J.J., Doyle J.L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bulletin. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D., et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gurevich A., Saveliev V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., Stones-Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S., Buxton S., Cooper A., Markowitz S., Duran C., et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowe T.M., Eddy S.R. tRNAscan-SE: A Program for Improved Detection of Transfer RNA Genes in Genomic Sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lagesen K., Hallin P., Rodland E.A., Staerfeldt H.H., Rognes T., Ussery D.W. RNAmmer: Consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Camacho C., Coulouris G., Avagyan V., Ma N., Papadopoulos J., Bealer K., Madden T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., Jones S.J., Marra M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19:1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.CodonW. [(accessed on 19 December 2020)]. Available online: http://codonw.sourceforge.net/

- 57.Librado R.J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wickham H. ggplot2. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011;3:180–185. doi: 10.1002/wics.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beier S., Thiel T., Münch T., Scholz U., Mascher M. MISA-web: A web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: A program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Y., Ye W., Zhang Y., Xu Y. High speed BLASTN: An accelerated MegaBLAST search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:7762–7768. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang H., Meltzer P., Davis S. RCircos: An R package for Circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen C., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H.R., Frank M.H., He Y., Xia R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant. 2020;13:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller M.A., Pfeiffer W., Schwartz T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees; Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE); New Orleans, LA, USA. 14–14 November 2010; New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2010. pp. 1–8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stamatakis A., Hoover P., Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 2008;57:758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ronquist F., Teslenko M., van der Mark P., Ayres D.L., Darling A., Höhna S., Larget B., Liu L., Suchard M.A., Huelsenbeck J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The entire complete mitogenome sequence with gene annotation has been submitted in the NCBI GenBank under the accession number OQ645347. The sequence data utilized in this study can be found in Supplementary Materials.