Abstract

Human gingival fibroblasts were challenged with Treponema pectinovorum and Treponema denticola to test three specific hypotheses: (i) these treponemes induce different cytokine profiles from the fibroblasts, (ii) differences in cytokine profiles are observed after challenge with live versus killed treponemes, and (iii) differences in cytokine profiles are noted from different gingival fibroblast cell lines when challenged with these treponemes. Three normal gingival fibroblast cell cultures were challenged with T. pectinovorum and T. denticola strains, and the supernatants were analyzed for cytokine production (i.e., interleukin-1α [IL-1α], IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, gamma interferon, macrophage chemotactic protein 1 [MCP-1], platelet-derived growth factor, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor). Unstimulated fibroblast cell lines produced IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1. T. pectinovorum routinely elicited the greatest production of these cytokines from the fibroblast cell lines, increasing 10- to 50-fold over basal production. While T. denticola also induced IL-6 and IL-8 production, these levels were generally lower than those elicited by challenge with T. pectinovorum. MCP-1 levels were significantly lower after T. denticola challenge, and the kinetics suggested that this microorganism actually inhibited basal production by the fibroblasts. No basal or stimulated production of the other cytokines was observed. Significant differences were noted in the responsiveness of the various cell lines with respect to the two species of treponemes and the individual cytokines produced. Finally, dead T. pectinovorum generally induced a twofold-greater level of IL-6 and IL-8 than the live bacteria. These results supported the idea that different species of oral treponemes can elicit proinflammatory cytokine production by gingival cells and that this stimulation did not require live microorganisms. Importantly, a unique difference was noted in the ability of T. pectinovorum to induce a robust MCP-1 production, while T. denticola appeared to inhibit this activity of the fibroblasts. While the general cytokine profiles of the fibroblast cell cultures were similar, significant differences were noted in the quantity of individual cytokines produced, which could relate to individual patient variation in local inflammatory responses in the periodontium.

Periodontal disease is clinically identified as an inflammation of the soft tissues and loss of connective tissue attachment and bone, surrounding the teeth, resulting from accumulation of bacteria in a biofilm within the subgingival sulcus (9). Depending on the quality and quantity of inflammation, including the characteristics of the immune cells and soluble mediators of cell communication and inflammation, associated irreversible tissue destruction represents the transition from gingivitis to periodontitis.

Numerous bacterial genera and species have been identified in the oral cavity (26). Presumably, they each play different, and potentially unique, roles in the ecosystem that develops within this niche in the oral cavity. Numerous investigations have noted a succession of bacterial species, which develop in an orderly fashion in the supragingival and subgingival areas of the gums and teeth (26, 42). If the biofilm remains undisturbed, the bacterial mass accumulates and the bacteria multiply and metabolize in this ecology. This biofilm structure or its individual components contribute to disruption of the epithelial tissue of the gingiva. As this occurs, serum exudes from the tissues into the sulcus and becomes available to the bacteria as nutrients, thus changing the local environment. As the environmental conditions of these ecosystems change, different species of bacteria are selected and emerge in the ecology. Among the proposed virulent species, which appear later in plaque maturation, are the spirochetes (21). Thus, spirochetes in the subgingival plaque are frequently correlated with periodontal disease and tissue destruction (40). The spirochetes are generally isolated during inflammation and disease, in contrast to healthy sites where few or no treponemes are isolated (41). Treponema pectinovorum and Treponema denticola are both gram-negative anaerobic spirochetes that are associated with adult and juvenile periodontitis (21, 26, 40, 42). Generally, these species are isolated from the subgingival plaque along with a substantial variety of other genera and species that comprise the complex biofilm and create a milieu of nutrient and waste product interdependencies.

The periodontium is a complex tissue structure comprised of resident cells, including epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and bone, as well as inflammatory cells of various types, which emigrate from the microvasculature of the gingiva in response to plaque accumulation (38). All of these cells can respond to challenges by bacteria and their products (30, 44). In the presence of initial stimulation, resident cells in the gingival tissue (i.e., epithelium and gingival fibroblasts) release various cell communication signals in the form of chemical cytokines. This in vivo process has been confirmed by the detection of various pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the gingival crevicular fluid (44). While there is an ever-increasing list of cytokines that provide for normal cell communication, some of these have been more closely linked with periodontitis (11, 16, 25, 30–33, 35, 46, 52), including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Additionally, various other cytokines have been implicated in chronic inflammatory diseases, including: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF [13]), gamma interferon (IFN-γ [8]), macrophage chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1 [3, 53]), and IL-10 (5). However, the primary cellular source for individual cytokines, as well as the potency and specificity of individual bacterial stimuli in periodontitis, remains to be determined.

Numerous host cells, including gingival fibroblasts, have the ability to respond to receptor stimulation by the production of a variety of substances that include paracrine and autocrine cytokines and growth factors. We have noted that both T. pectinovorum and T. denticola bind to gingival fibroblasts at a similar density, but they do not appear to compete for binding sites (49). One interpretation of this finding is that these two related bacteria bind to different receptors on the cells. Since different receptors often signal specific cytokine responses it could be predicted that these two treponemes could elicit different types of cytokine production. Definition of the profile of cytokines resulting from bacterial stimulation of gingival fibroblasts should result in a clearer understanding of host-bacterium interactions in the periodontium, which can lead to a breakdown of the local tissue homeostasis. In these experiments we evaluated the pattern of cytokines produced by human gingival fibroblasts (HGFs) when challenged with T. denticola and T. pectinovorum. Three specific hypotheses were tested: (i) T. denticola and T. pectinovorum induce different cytokine profiles produced by gingival fibroblasts, (ii) differences in cytokine profiles result when gingival fibroblasts are challenged with live versus killed treponemes, and (iii) variations in cytokine profiles are observed with different gingival fibroblast cell lines when challenged with these treponemes. We suggest that these differences reflect interactions with different surface receptors on gingival fibroblasts and could impact upon the characteristics of the local inflammatory milieu at the site of colonization by each of these microorganisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

T. pectinovorum strains ATCC 33768 and S1 (20) and T. denticola strains ATCC 35404, 33520, and GM-1 (50) were grown anaerobically in a Coy anaerobic chamber. The T. pectinovorum strains were grown for 36 h in NOS media supplemented with 3 ml of thymine, 3 ml of cysteine, 5 ml of fatty acids, 20 ml of sodium bicarbonate, and 3 g of pectin per liter (6, 20). T. denticola strains were grown for 48 h in the supplemented NOS medium; however, 50 ml of rabbit serum was added instead of the pectin (6, 20). For the analyses, the bacteria were centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 20 min and washed, and the cells were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.05 M phosphate, pH 7.2). Bacterial cell counts were estimated using a hemocytometer. The purity of the culture was determined by phase-contrast and dark-field microscopic observations.

Formalinized T. pectinovorum was prepared by incubating washed bacteria with 0.5% buffered formal saline overnight on the rotator (11). The following day, the formalinized bacteria were washed with PBS, and the pellet was broken apart by forcing the bacteria through gradually smaller gauge needles. T. pectinovorum was then counted and resuspended at the appropriate dilution in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

HGFs.

Three different cultures of normal HGFs (Gin-4, Gin-7, and Gin-8) (44) were grown to confluency in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, Logan, Utah), antibiotics (penicillin [100/ml] and streptomycin [100/ml]; Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.), and l-glutamine (2 mM; Gibco) at 37°C in 5% CO2 and moist air (44). The cells routinely reached confluency by approximately 4 to 5 days and were passaged by a 1:3 split. All experiments were carried out with gingival fibroblasts at passages <12.

In vitro bacterium–gingival-fibroblast interactions.

The gingival fibroblasts were plated into 24-well microtiter plates at 105 cells/well. They were propagated to confluency (∼5 × 105/well) for 2 days prior to experimentation. The bacteria were resuspended in DMEM and 1% FBS without antibiotics, and 1 ml was added to the test wells. Three different concentrations of bacteria were used for the challenge (5 × 107, 5 × 108, and 5 × 109/ml), and all assessments were made in triplicate. Supernatants were collected at six different time points (1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h following challenge), centrifuged (13,000 × g for 5 min), and frozen in multiple aliquots at −80°C.

ELISA for cytokines.

Two different sequential enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) procedures (43) were performed to detect 10 different host factors: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, GM-CSF, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), MCP-1, IL-1α, IL-10, and IFN-γ. Microtiter plate wells were incubated with 0.2 ml of a 5-μg/ml concentration of mouse monoclonal antibody to each of the cytokines (except PDGF, which utilized a goat polyclonal antibody) in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer as a capture antibody. After 3 to 4 h of incubation at 37°C, the solution was removed and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in PBS was added to block unbound sites in the wells. The plates were stored with the BSA at 4°C at least overnight. Samples were assayed in the sequence of the least to the most prominent cytokine in the fluid to be analyzed based upon our previous studies, as well as the minimal detectable dose of the assays. A pooled recombinant standard of cytokines was used on all the plates. Each of the cytokines in the pooled standard was adjusted to 1,000 pg/0.2 ml and diluted serially twofold to 1.95 pg/0.2 ml. All samples were added to the first plate of the sequence (e.g., anti-IL-1β) in duplicate using 200 μl of the undiluted supernatants per well. The same volume of the pooled standard was added to the ELISA plate. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, each sample well and each standard well was replicate transferred (175 μl) directly from the first plate and mixed with 25 μl of sample diluent in the same location of the second plate in the sequence (e.g., anti-GM-CSF-coated plate) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The first plate was then developed with rabbit antibody (e.g., anti-IL-1β), goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to alkaline phosphatase and p-nitrophenylphosphate as the substrate (43). At the end of the incubation of the second plate in the sequence (e.g., GM-CSF), 175 μl of the samples and standards was replicate transferred to a third plate. The second plate was developed with rabbit antibody (e.g., anti-GM-CSF) and additional reagents as described above. This sequence of events was repeated (e.g., IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-8) throughout the assay until all plates were incubated with the appropriate rabbit antisera. The second cytokine series included IL-10, PDGF, TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-1α, which were analyzed using specific capture and developing antibodies as described above.

The commercial sources of the various reagents were as follows (recombinant standard: monoclonal capture: polyclonal developing reagent): IL-1α (Sigma: Genzyme [Cambridge, Mass.]: Sigma), IL-1β (R&D [Minneapolis, Minn.]: Biosource [Camarillo, Calif.]: Sigma), IL-6 (R&D: Biosource: Sigma), IL-8 (Biosource: Biosource: Endogen [Cambridge, Mass.]), IL-10 (Genzyme: Biosource [i.e., rat]: Genzyme), IFN-γ (R&D: Biosource: Genzyme), TNF-α (Biosource: Genzyme: Genzyme), GM-CSF (R&D: Genzyme: Genzyme), MCP-1 (Sigma: Sigma: Chemicon [Temecula, Calif.]), and PDGF (BioDesign [Kennebunk, Maine]: R&D: Genzyme).

The levels of cytokines in the samples were determined using Dynatech Biolinx software (Dynatech, Chantilly, Va.) with a sigmoidal fit. Intraplate and interplate variability was accepted with a sample duplicate variation of ≤15%, and the standard curve between plates required (i) a maximum optical density of at least 1.0 (no more than 20% variation), (ii) no significant difference (P > 0.05) in the slopes, and (iii) a background of <0.15.

Statistical analyses.

The results were analyzed using a two-tailed Student t test (Minitab, State College, Pa.) to assess the null hypotheses that T. pectinovorum and T. denticola induce HGF secretion of similar proinflammatory mediators and cytokines, that different HGF cell lines respond similarly to challenge with oral treponemes, and that live and killed T. pectinovorum bacteria elicit similar mediators and cytokines from HGFs.

RESULTS

Cytokine responses of gingival fibroblasts to oral treponemes.

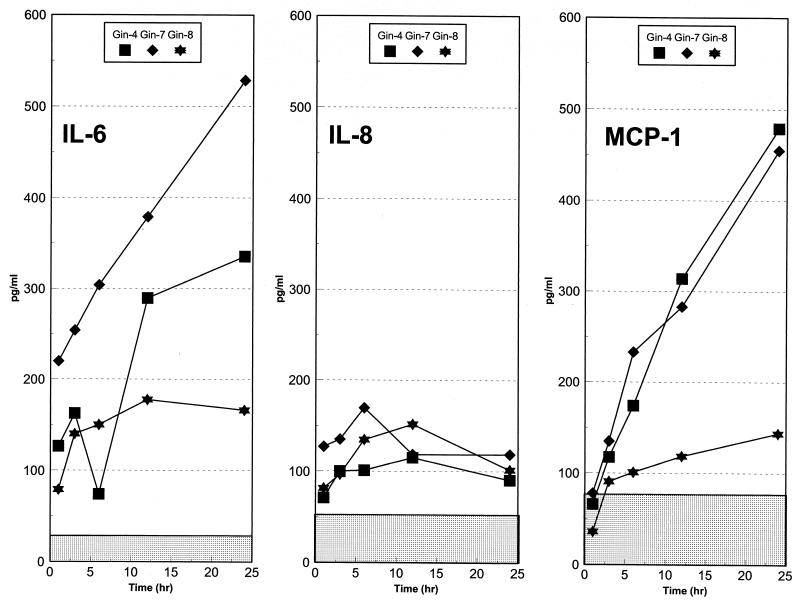

Basal levels of 10 cytokines and/or growth factors were evaluated in HGF cell cultures from three periodontally healthy individuals. During a 48-h in vitro analysis interval, we could detect no production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, PDGF, GM-CSF, IL-1α, IL-10, and IL-1β above the minimum detectable level of the assays. However, the gingival fibroblasts were capable of producing IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 without exogenous challenge. These levels were ca. 200 to 500 pg/ml (IL-6), ca. 110 to 175 pg/ml (IL-8), and ca. 150 to 500 pg/ml (MCP-1) (Fig. 1). Generally, the maximum levels of these cytokines were noted at 12 to 24 h (IL-6 and MCP-1) and 6 to 12 h (IL-8) during the culture period.

FIG. 1.

Basal cytokine production by the gingival fibroblast populations. Ten different cytokines were tested and only IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 were detected in unstimulated cultures. The points denote the mean production levels from triplicate determinations with each cell line. The stippled areas denote the minimum detectable dose for each of the assays. The 48-h data are not presented since the cytokine levels generally dropped, probably due to degradation, and alterations were noted microscopically in the structural integrity of the fibroblasts.

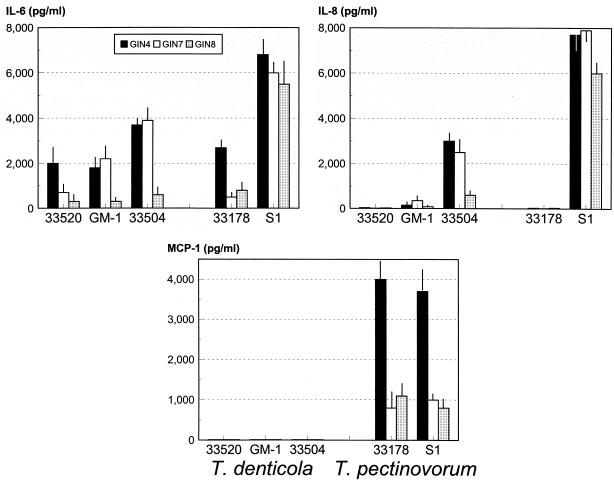

The gingival fibroblasts were then challenged with viable T. denticola and T. pectinovorum. Each of the two T. pectinovorum and three T. denticola strains stimulated the individual fibroblast cell lines to produce elevated levels of IL-6 (Fig. 2), with an eightfold increase (ca. 2,000 to 6,000 pg/ml), although the clinical S1 isolate of T. pectinovorum was uniformly more stimulatory. Examination of IL-8 levels demonstrated a substantial variation among the strains within each species, although at least one isolate stimulated IL-8 levels by 20- to 50-fold (Fig. 2). Again, the T. pectinovorum clinical isolate, S1, exhibited significantly greater induction compared to all of the other strains. Both of the T. pectinovorum strains stimulated MCP-1 by 7- to 10-fold (Fig. 2), while MCP-1 levels were negligible after T. denticola challenge and were significantly lower than even basal levels produced by the gingival fibroblasts. After challenge of all three gingival fibroblast lines with various concentrations of these oral treponemes, no induction of IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, GM-SCF, IFN-γ, PDGF, or IL-10 could be detected.

FIG. 2.

IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 production by three different cell lines (Gin-4, Gin-7, and Gin-8) after challenge with live T. denticola or T. pectinovorum strains. The cells were stimulated with 5 × 109 bacteria. The bars denote the mean level of cytokine detected during a 24-h culture period from triplicate determinations of each cell line, and the vertical line denotes 1 standard deviation.

Characteristics of IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 induction for individual gingival fibroblast cell lines.

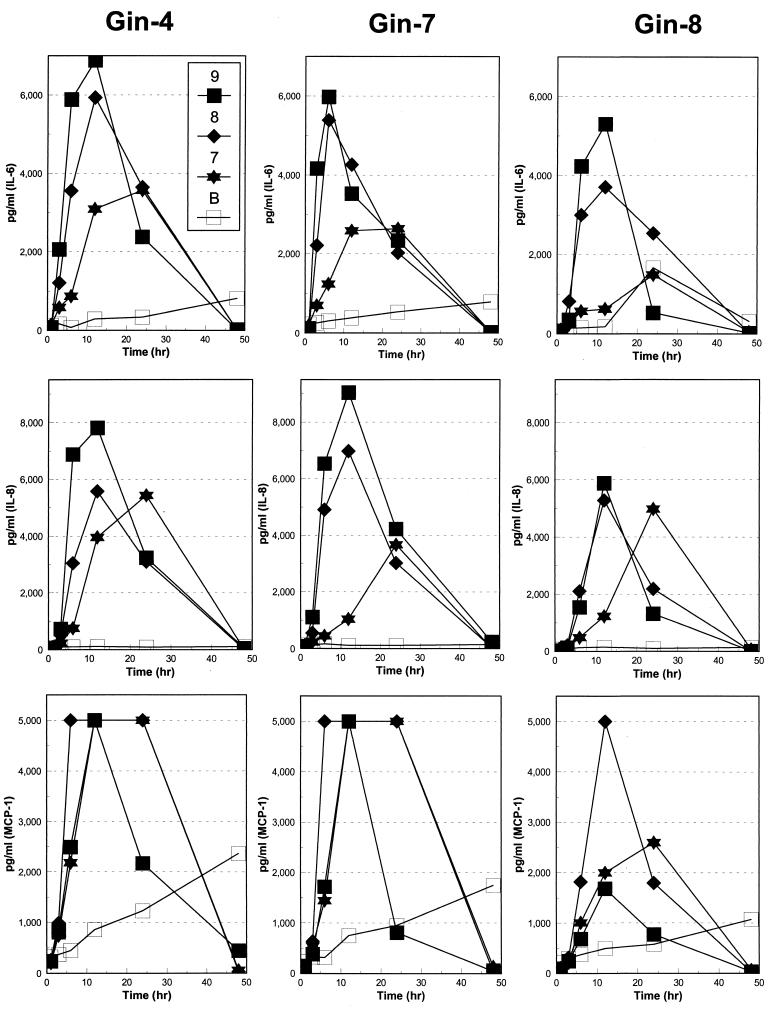

Three different normal gingival fibroblast cell lines were used during this study: Gin-4, Gin-7, and Gin-8. In general, a dose response for each of the three cytokines was noted when the gingival fibroblast cell cultures were stimulated by T. pectinovorum strain S1 (Fig. 3). A significantly elevated IL-6 level was detected from 6 to 24 h (P < 0.003 to P < 0.05) versus basal levels, with the various challenge conditions, with peak levels of IL-6 noted at 6 to 12 h postchallenge. T. pectinovorum induced similar levels of IL-8 production by the gingival fibroblast cells (Fig. 3). The highest dose elicited peak levels by 6 to 12 h (P < 0.006 to P < 0.03 versus basal levels), while the levels at the lowest dose peaked at 24 h (P < 0.0001 to P < 0.05 versus basal levels). MCP-1 was produced following stimulation of all three gingival fibroblast cultures by each of the doses of T. pectinovorum (Fig. 3). The levels were observed by as early as 6 h and routinely peaked at 6 to 12 h. Interestingly, the Gin-8 gingival fibroblast cell population appeared to be routinely less responsive to challenge with the T. pectinovorum strain. We did observe a substantial difference in the basal production of the fibroblast cell lines of MCP-1 (e.g., compare Fig. 1 with Fig. 3). We have noted previously that the gingival fibroblast responses are related to the concentration and the qualities of the FBS used in these type of in vitro studies (11). Thus, we propose that the variances in basal production across experiments are related to the FBS; nevertheless, the stimulated responses appeared to be proportional irrespective of the absolute basal level.

FIG. 3.

IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 basal production (B) or production following challenge of individual gingival fibroblast populations of Gin-4, Gin-7, and Gin-8 with 5 × 107 (■), 5 × 108 (⧫), or 5 × 109 (✶) T. pectinovorum strain S1 bacteria. The points denote the mean levels from triplicate determinations at each time point. The variation of the replicate measures was consistently <12% of the mean.

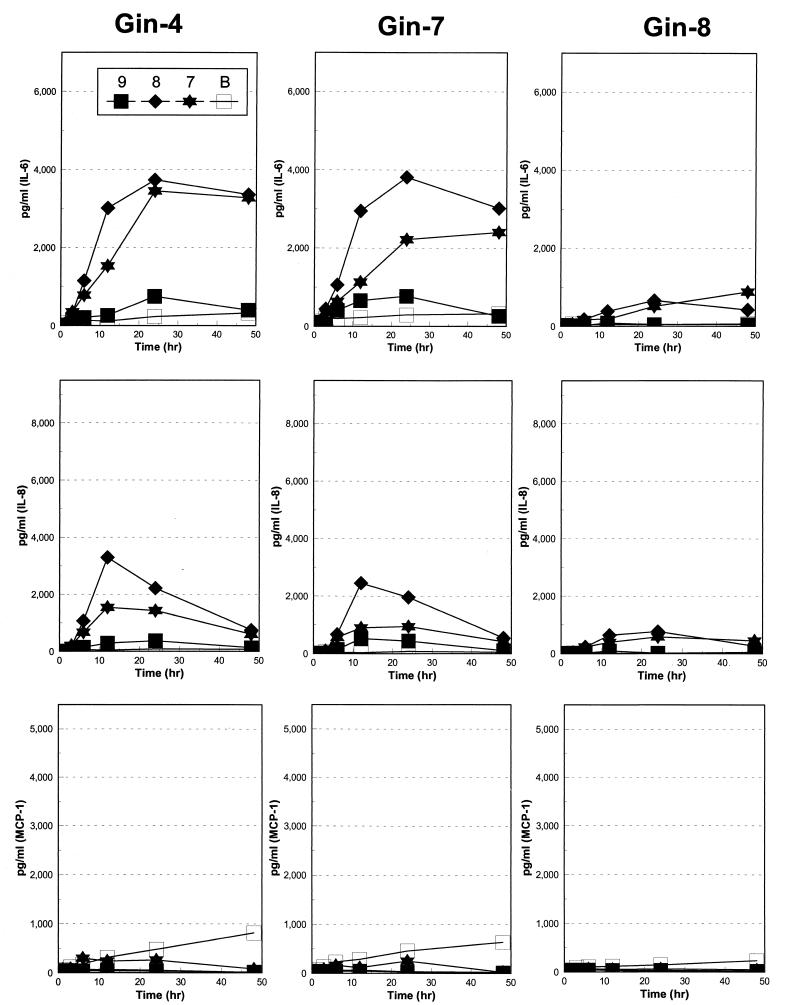

T. denticola 35404 stimulated peak levels of IL-6 (P < 0.019 to P < 0.049) by 24 h after challenge (Fig. 4). As observed with IL-6, IL-8 production reached peak levels by 24 h in a dose-response fashion with all gingival fibroblast cell cultures (Fig. 4). Importantly, both IL-6 and IL-8 levels were significantly lower when comparing the T. denticola challenge to the T. pectinovorum challenge. MCP-1 levels were routinely decreased below basal gingival fibroblast production following challenge with T. denticola (Fig. 4). An inverse relationship of MCP-1 level in the gingival fibroblast cultures to T. denticola dose was observed. As was noted with the T. pectinovorum challenge, the Gin-8 gingival fibroblast population was significantly less responsive with each cytokine to this T. denticola stimulation. Interestingly, the highest dose of T. denticola used for challenge was routinely accompanied by a decreased level of cytokines.

FIG. 4.

IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 basal production (B) or production following challenge of individual gingival fibroblast populations of Gin-4, Gin-7, and Gin-8 with 5 × 107 (■), 5 × 108 (⧫), or 5 × 109 (✶) T. denticola strain 33504 bacteria. The points denote the mean levels from triplicate determinations at each time point. The variation of the replicate measures was consistently <15% of the mean.

Characteristics of cytokine production by gingival fibroblasts following challenge with live versus dead T. pectinovorum.

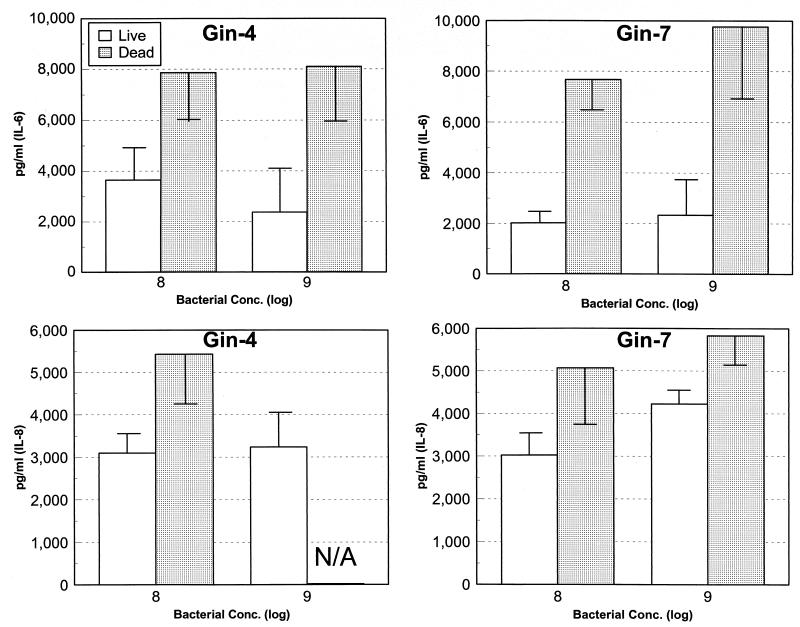

Substantial data has been gathered suggesting that during the progression of periodontitis, large numbers of intact (e.g., viable) bacteria are not routinely detected in the damaged tissue or at the progressing front of the disease (36, 37). Thus, to evaluate whether live treponemes are required to stimulate the gingival fibroblast cell responses, we compared gingival fibroblast reactions to live and dead T. pectinovorum. We targeted IL-6 and IL-8 to discriminate differences in host-bacterium interactions. The results indicate that dead T. pectinovorum induced levels of both cytokines which were approximately twofold greater than those noted with the live microorganisms (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

IL-6 and IL-8 production after challenge of Gin-4 or Gin-7 gingival fibroblast populations with 5 × 108 and 5 × 109 live or dead T. pectinovorum S1 bacteria. The bars denote the mean levels from triplicate determinations at the peak time for each cytokine (e.g., 12 h for treatment with the live bacteria and 48 h for treatment with dead bacteria). The vertical bracket encloses 1 standard deviation. N/A, data not available.

DISCUSSION

Gingival fibroblasts are the cells comprising the connective tissue surrounding the teeth. Gingival tissues can be removed and, in culture, these fibroblasts proliferate for many generations in vitro. These resident cells of the oral cavity have surface receptors that are used for communication, and it is becoming increasingly apparent that the resident cells of the periodontium play an important role in cytokine production in the local environment. The quality and quantity of these receptors can change in response to the external environment (2, 12, 17, 22, 23, 29). The receptors are generally specific for various macromolecules and, when they are complexed, signals are transduced within the cell. This receptor triggering initiates a series of events in response to the binding process. Certain of these events inside the cell result in the production of cytokines (4). Epithelial cells (3, 8, 39) and fibroblasts (3, 8, 11, 39, 53) can both produce these macromolecules for cell communication and to amplify the immune system to control infections. However, there are minimal data on the interactions of oral spirochetes with these resident cells. The present studies were performed to specifically evaluate the outcome of T. denticola and T. pectinovorum interaction with HGFs. In particular, we emphasized cytokine production as a measure of this interaction. This study shows that neither T. pectinovorum nor T. denticola stimulated IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-10, PDGF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, or TNF-α production by the gingival fibroblasts. The results suggest that (i) the spirochetes do not interact with appropriate receptors on the fibroblasts which are required for triggering synthesis of these cytokines, (ii) gingival fibroblasts are incapable of producing these cytokines, (iii) these cytokines are rapidly degraded or removed by binding to the bacteria or host cells, and/or (iv) the levels produced by the gingival fibroblasts are too low to be detected by the systems utilized here. While our studies do not provide direct proof to select among these options, other studies have identified the capacity of gingival fibroblasts to produce certain of the cytokines (1, 44). While T. denticola exhibits some proteolytic activity, which may contribute to degradation of cytokines, we feel it most likely that these treponemes do not trigger the appropriate surface receptors on the gingival fibroblasts required for an appropriate signal transduction leading to specific cytokine synthesis.

Three cytokines, IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1, were produced by gingival fibroblasts, both constitutively and in significantly increased levels after challenge with T. denticola and/or T. pectinovorum. Three normal gingival fibroblast cell lines, derived from unrelated healthy donors, were stimulated with the treponemes, and with each gingival fibroblast population T. pectinovorum elicited IL-6 levels which were 4- to 10-fold greater than those induced by T. denticola. Interestingly, the largest amount of T. denticola (109) used to challenge the gingival fibroblasts appeared to consistently be associated with lower levels of IL-6 than did smaller T. denticola challenge doses. We have noted previously that IL-6 is particularly susceptible to proteolytic degradation by the trypsin-like enzyme activities of Porphyromonas gingivalis (44). Since T. denticola strains also produce a trypsin-like activity (18), the IL-6 could be proteolytically destroyed at larger amounts of bacterial challenge. In contrast, the T. pectinovorum strains lack this activity. As with IL-6, IL-8 production was three- to fourfold greater with T. pectinovorum than with T. denticola stimulation of the gingival fibroblasts. Additionally, similar to IL-6, larger doses of T. denticola either stimulated less IL-8, accelerated degradation of this chemokine, or bound the molecules to the bacterial surface and eliminated them from the extracellular milieu.

A major difference in the cytokine profiles induced by the two treponemes was the substantial production of MCP-1 induced by T. pectinovorum. In contrast, T. denticola appeared to inhibit basal production of MCP-1 by the gingival fibroblasts, such that by the 48-h time point, the stimulated cultures showed <80 pg/ml, while basal levels of 150 to 500 pg/ml were produced by the unchallenged gingival fibroblasts. These results are consistent with T. pectinovorum potentially interacting via multiple binding sites on the gingival fibroblasts or specifically targeting unique receptors, leading to the production of greater levels and unique cytokines. Importantly, the production of MCP-1, which attracts macrophages to the site of inflammation or infection and can activate these cells (14, 34), implies that both the innate and adaptive immune systems could contribute to the local response to this microorganism. In contrast, T. denticola has developed a strategy to impede this activity of the host response. Additionally, we have principally isolated T. pectinovorum from the subgingival plaque of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients with periodontitis, whereas T. denticola predominates in seronegative periodontitis patients (48). Since macrophages have been identified as a long-lived source of HIV production in humans (7, 10), particularly following activation of the cells (27, 28, 51), the ability of T. pectinovorum to elicit MCP-1 in the local gingival environment could have important ramifications associated with viral activation and production within the periodontal environment. Thus, the association of necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis in HIV-infected patients with a rapid decrease in survival time could reflect this immune stimulation by members of the oral microbiota in this pathogenic ecology.

Three normal gingival fibroblast cell lines from different subjects were tested (Gin-4, Gin-7, and Gin-8). The results indicated variations in responsiveness to bacterial challenge. IL-6 production demonstrated a profile of Gin-4 ≥ Gin-7 > Gin-8 levels when either treponeme was used. Moreover, T. pectinovorum stimulated 4- to 10-fold-greater levels of IL-6 in each cell culture compared to T. denticola. IL-8 production demonstrated a profile of Gin-4 = Gin-7 > Gin-8 responses to both treponemes. As noted with IL-6, Gin-4 and Gin-7 produced approximately 10-fold more IL-8 after T. pectinovorum challenge. In contrast, Gin-8 was generally unresponsive to T. denticola for production of this chemokine. Gin-4 and Gin-7 produced at least twofold more MCP-1 than Gin-8 after T. pectinovorum challenge, while none of the cell lines consistently responded to T. denticola in producing this cytokine. We conclude that gingival fibroblast cell populations derived from different normal subjects react differently to these bacterial challenges and suggest the potential for host variability in responsiveness. Currently, few genetic studies on periodontitis have been performed, although promising evidence suggests some genetic linkage (15, 24, 47), including host response alterations associated with genetic polymorphisms (19, 31, 45). These published studies suggested a genetic contribution to the characteristics of the inflammatory and immune response to oral bacterial challenge and the subsequent expression of periodontal disease. Thus, the local environmental factors (e.g., bacteria) not only impact the immune system but also may alter resident cell (e.g., gingival fibroblast) functions. Our findings suggest variation in gingival fibroblast responsiveness to proposed periodontal pathogens that may be an additional consideration in risk assessment. Studies by Hassell and Harris (15) have also supported population differences in the proliferative capacities of gingival fibroblasts. Whether genetic influences truly impact upon fibroblast functions and responsiveness, as evaluated here, requires additional exploration.

We subsequently determined differences between cytokine induction by live and dead T. pectinovorum. The results showed that dead bacteria stimulated a greater production of both IL-6 and IL-8 than did live bacteria. Specifically, the live and dead bacteria induced cytokine production, which increased through 12 to 24 h. With live T. pectinovorum, the levels then decreased significantly, while the dead bacteria continued to induce the production of cytokines through 48 h, which was the termination point of these cultures. Furthermore, with live microorganisms, by 48 h the gingival fibroblasts generally exhibited altered cellular structure, suggesting likely deleterious actions on the functions of these cells. The differences could be due to (i) the degradation of the cytokines by fibroblast enzymatic activity, (ii) the degradation of IL-6 and IL-8 by the bacteria, or (iii) the cytokines binding to the bacteria or to increased numbers of receptors on the gingival fibroblasts stimulated by the live microorganisms. Alternatively, the treated spirochetes may exhibit a more rigid structure, thus cross-linking more gingival fibroblast receptors stimulating cytokine production. Additional studies are required to differentiate between these mechanisms and to evaluate the biological significance of this finding. Irrespective of the mechanism, the results suggest that nonviable bacteria or their products can effectively stimulate cytokine production by gingival fibroblasts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant DE-11368 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

We thank S. Walker and L. Kesavalu for technical assistance in preparation of the live and formalin-killed treponemes. We also express our appreciation for contributions by Stanley Holt in the development of the experimental designs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal S, Baran C, Piesco N P, Quintero J C, Langkamp H H, Johns L P, Chandra C S. Synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines by human gingival fibroblasts in response to lipopolysaccharides and interleukin-1β. J Periodontal Res. 1995;30:382–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1995.tb01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastian S, Paquet J L, Robert C, Cremers B, Loillier B, Larrivee J F, Bachvarov D R, Marceau F, Pruneau D. Interleukin 8 (IL-8) induces the expression of kinin B1 receptor in human lung fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:750–755. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkedal-Hansen H. Role of cytokines and inflammatory mediators in tissue destruction. J Periodontal Res. 1993;28:500–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1993.tb02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bliska J B, Galan J E, Falkow S. Signal transduction in the mammalian cell during bacterial attachment and entry. Cell. 1993;73:903–920. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan F M. Interleukin 10 and arthritis. Rheumatology. 1999;38:293–297. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan E C S, Siboo R, Touyz L Z G, Qiu Y-S, Klitorinos A. A successful method for quantifying viable oral anaerobic spirochetes. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993;8:80–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collman RG, Yi Y. Cofactors for human immunodeficiency virus entry into primary macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 3):S422–S426. doi: 10.1086/314797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curfs J H, Meis J F, Hoogkamp-Korstanje J A. A primer on cytokines: sources, receptors, effects, and inducers. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:742–780. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darveau R P, Tanner A, Page R C. The microbial challenge in periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:12–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimitrov D S, Norwood D, Stantchev T S, Feng Y, Xiao X, Broder C C. A mechanism of resistance to HIV-1 entry: inefficient interactions of CXCR4 with CD4 and gp120 in macrophages. Virology. 1999;259:1–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dongari-Bagtzoglou A, Ebersole J L. Production of inflammatory mediators and cytokines by human gingival fibroblasts following bacterial challenge. J Periodontal Res. 1996;31:90–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebersole J L. Immune responses in periodontal diseases. In: Wilson T G, Kornman K S, editors. Fundamentals of periodontics. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence Publishing Co., Inc.; 1996. pp. 109–158. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira M B, Carlos A G. Cytokines and asthma. J Investig Allerg Clin Immunol. 1998;8:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graves D T, Jiang Y. Chemokines, a family of chemotactic cytokines. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6:109–118. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassell T M, Harris E L. Genetic influences in caries and periodontal diseases. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6:319–342. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heasman P A, Collins J G, Offenbacher S. Changes in crevicular fluid levels of interleukin-1β, leukotriene B4, prostaglandin E2, thromboxane B2 and tumor necrosis factor α in experimental gingivitis in humans. J Periodontal Res. 1993;28:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1993.tb02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou L, Ravenall S, Macey M G, Harriott P, Kapas S, Howells G L. Protease-activated receptors and their role in IL-6 and NF-IL-6 expression in human gingival fibroblasts. J Periodontal Res. 1998;33:205–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kesavalu L, Walker S G, Holt S C, Crawley R R, Ebersole J L. Virulence characteristics of oral treponemes in a murine model. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5096–5102. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5096-5102.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornman K S, Crane A, Wang H-Y, di Giovine F S, Newman M G, Pirk F W, Wilson T G, Jr, Higgenbottom F L, Duff G W. The interleukin-1 genotype as a severity factor in adult periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:72–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leschine S B, Canale-Parola E. Rifampin as a selective agent for isolation of oral spirochetes. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;6:792–795. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.6.792-795.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loesche W J. The role of spirochetes in periodontal disease. Adv Dent Res. 1988;2:275–283. doi: 10.1177/08959374880020021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lurton J, Soto H, Narayanan A S, Raghu G. Regulation of human lung fibroblast C1q-receptors by transforming growth factor-beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Exp Lung Res. 1999;25:151–164. doi: 10.1080/019021499270367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malmstrom J, Westergren-Thorsson G. Heparan-sulfate upregulates platelet-derived growth factor receptors on human lung fibroblasts. Glycobiology. 1998;8:1149–1155. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.12.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marazita M L, Burmeister J A, Gunsolley J C, Koertge T E, Lake K, Schenkein H A. Evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance and race-specific heterogeneity in early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1994;65:623–630. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masada M P, Persson R, Kenney J S, Lee S W, Page R C, Allison A C. Measurement of interleukin-1α and -1β in gingival crevicular fluid: implications for the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1990;25:156–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1990.tb01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore W E C, Moore L V H. The bacteria of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 1994;5:66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriuchi H, Moriuchi M, Fauci A S. Induction of HIV-1 replication by allogeneic stimulation. J Immunol. 1999;162:7543–7548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriuchi M, Moriuchi H, Turner W, Fauci A S. Exposure to bacterial products renders macrophages highly susceptible to T-tropic HIV-1. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:1540–1550. doi: 10.1172/JCI4151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogura N, Nagura H, Abiko Y. Increase of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor expression in human gingival fibroblasts by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. J Periodontol. 1999;70:402–408. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page R C. The role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:230–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1991.tb01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pociot F, Molvig J, Wogensen L, Worsaae H, Nerup J. A Taq I polymorphism in the human interleukin-1β (IL-1β) gene correlates with IL-1β secretion in vitro. Eur J Clin Investig. 1992;22:224–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinhardt R A, Masada M P, Daldahl W B, DuBois L M, Kornman K S, Choi J-L, Kalkwarf K L, Allison A C. Gingival fluid IL-1 and IL-6 levels in refractory periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts F A, Hockett R D, Jr, Bucy R P, Michalek S M. Quantitative assessment of inflammatory cytokine gene expression in chronic adult periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1997;12:336–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rollins B J. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1: a potential regulator of monocyte recruitment in inflammatory disease. Mol Med Today. 1996;2:198–204. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)88772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossomando E F, White L. A novel method for the detection of TNF-alpha in gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontol. 1993;64:445–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saglie F R. Bacterial invasion and its role in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. In: Hamada S, Holt S C, McGhee J R, editors. Periodontal disease: pathogens and host responses. Tokyo, Japan: Quintessence Publishing Co., Ltd.; 1991. pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandros J, Papapanou P N, Nannmark U, Dahlén G. Porphyromonas gingivalis invades human pocket epithelium in vitro. J Periodontal Res. 1994;29:62–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1994.tb01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz Z, Dean D D, Boyan B D. The biochemistry and physiology of the periodontium. In: Wilson T G, Kornman K S, editors. Fundamentals of periodontics. Chicago, Ill: Quintessence Publishing Co., Inc.; 1996. pp. 61–107. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shupp, E., M. J. Steffen, and J. L. Ebersole. Cytokines produced by epithelial cells and fibroblasts stimulated with Treponema pectinovorum. J. Dent. Res., in press.

- 40.Simonson L G, Goodman C H, Morton H E. Quantitative immunoassay of Treponema denticola serovar in adult periodontitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1493–1496. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.7.1493-1496.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smibert R M, Johnson J L, Ranney R R. Treponema socranskii sp. nov., Treponema socranskii subsp. socranskii subsp. nov., Treponema socranskii subsp. buccale subsp. nov., and Treponema socranskii subsp. paredis subsp. nov. isolated from humans with experimental gingivitis and periodontitis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:456–462. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Socransky S S, Haffajee A D, Ximenez-Fyvie L A, Feres M, Mager D. Ecological considerations in the treatment of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis periodontal infections. Periodontol 2000. 1999;20:341–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1999.tb00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steffen M J, Ebersole J L. Sequential ELISA for cytokine levels in limited volumes of biological fluids. BioTechniques. 1996;21:504–509. doi: 10.2144/96213rr04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steffen, M., S. C. Holt, and J. L. Ebersole.Porphyromonas gingivalis induction of mediator and cytokine secretion by human gingival fibroblasts. Oral Microbiol. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Tangada S D, Califano J V, Nakashima K, Quinn S M, Zhang J B, Gunsolley J C, Schenkein H A, Tew J G. The effect of smoking on serum IgG2 reactive with Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in early-onset periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 1997;68:842–850. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.9.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tonetti M S, Freiburghaus K, Lang N P, Bickel M. Detection of interleukin-8 and matrix metalloproteinases transcripts in healthy and diseased gingival biopsies by RNA/PCR. J Periodontal Res. 1993;28:511–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1993.tb02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Dyke T E, Lester M A, Shapira L. The role of the host response in periodontal disease progression: implications for future treatment strategies. J Periodontol. 1993;64:792–806. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.8s.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker S G, Ebersole J L, Holt S C. Identification, isolation, and characterization of the 42-kilodalton major outer membrane protein (MompA) from Treponema pectinovorum ATCC 33768. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6441–6447. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6441-6447.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker S G, Ebersole J L, Holt S C. Studies on the binding of Treponema pectinovorum to HEp-2 epithelial cells. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1999;14:165–171. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.1999.140304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinberg A, Holt S C. Interaction of Treponema denticola TD-4, GM-1, and MS25 with human gingival fibroblasts. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1720–1729. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1720-1729.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wodarz D, Lloyd A L, Jansen V A, Nowak M A. Dynamics of macrophage and T cell infection by HIV. J Theor Biol. 1999;196:101–113. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yamazaki K, Nakajima T, Kubota Y, Gemmell E, Seymour G, Hara K. Cytokine messenger RNA expression in chronic inflammatory periodontal disease. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1997;12:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1997.tb00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu X, Graves D. Fibroblasts, mononuclear phagocytes, and endothelial cells express monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in inflamed human gingiva. J Periodontol. 1995;66:80–88. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]