Abstract

Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) strains are important human pathogens which are capable of causing diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and the potentially fatal hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). An important virulence trait of certain STEC strains, such as those belonging to serogroup O157, is the capacity to produce attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions on enterocytes, a property encoded by the locus for enterocyte effacement (LEE). LEE contains the eae gene, which encodes intimin, an outer membrane protein which mediates the intimate attachment of bacteria to the host epithelial cell surface, and eae is routinely used as a marker for LEE-positive STEC strains. However, the O157:H− STEC strain 95SF2 carries eae but did not produce A/E lesions on HEp-2 cells, as judged by a fluorescent actin staining assay. In this assay, 95SF2 adhered poorly to the HEp-2 cells, and those that did bind exhibited abnormal cell division. In contrast, the O157:H7 STEC strain EDL933 adhered strongly and produced typical A/E lesions. We have demonstrated that 95SF2 carries a defective LEE regulatory gene, ler, with a single base change with respect to that published for ler of EDL933, resulting in an Ile57-to-Thr substitution. Ler shows homology to H-NS-like regulators, which are modulators of transcription, and the mutation occurs in a domain implicated in oligomerization. 95SF2 was able to adhere and produce A/E lesions on HEp-2 cells when EDL933 ler was expressed from a multicopy plasmid. Conversely, introduction of a plasmid carrying 95SF2 ler into EDL933 abolished adherence and capacity to form A/E lesions. Studies with eae deletion derivatives of 95SF2 and EDL933 demonstrated that the ler-mediated adherence to HEp-2 cells is largely independent of intimin. We have also demonstrated that EDL933 ler, but not 95SF2 ler, increases the level of intimin in O157 STEC.

Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) strains are important human pathogens, causing diarrhea and hemorrhagic colitis, which can lead to systemic complications, such as the potentially fatal hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) (26). Many STEC strains belong to a family of attaching and effacing (A/E) intestinal pathogens (40). The prototype for A/E bacteria is the nontoxigenic enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), which is a leading cause of infantile diarrhea in developing countries (14). A/E lesions are characterized phenotypically by localized destruction of the apical microvilli of intestinal epithelial cells resulting from rearrangement of the cytoskeleton and by intimate attachment of bacteria to the enterocyte surface. The genetic determinant is the chromosomally encoded pathogenicity island called the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) (36). LEE encodes a type III secretion system (24) and E. coli secreted proteins (Esp) which deliver effector molecules to the host cell and disrupt the host cytoskeleton (27, 32). LEE also carries eae and tir, which encode intimin and Tir, respectively. Intimin is an outer membrane protein required for intimate attachment to epithelial cells (25); Tir is the intimin receptor, which is produced by the bacteria and then translocated into the host cell membrane (28).

The genes required for the generation of A/E lesions need to be coordinately expressed in response to environmental stimuli. Until recently, however, very little was known about the regulation of LEE in EPEC and STEC. Previously, the per locus of EPEC was shown to transcriptionally activate eae of LEE and the bundle-forming pilus (bfp) operon of the EAF plasmid (10, 19, 51). However, Per has now been shown to be a global regulator of LEE, as it induces the production of a novel transcriptional activator, Ler (LEE-encoded regulator) (38). The genes of LEE are organized into four polycistronic operons, LEE1 through LEE4 (38). Using lacZ fusions, per was shown to directly activate only LEE1. LEE1 contains ler (previously known as orf1) (18, 46), and the product of ler then transcriptionally activates LEE2, LEE3, and, to a lesser extent, LEE4 (38). Thus, in EPEC, Per and Ler collectively form a regulatory cascade that activates the expression of LEE genes. This dual regulatory control is similar to the regulatory cascade of VirF and VirB that activates the Shigella flexneri type III secretion system and secreted molecules (2, 15). EPEC Ler is similar to the salmonella DNA structural protein and transcriptional regulator, H-NS-like protein (18). H-NS modulates the expression of many environmentally regulated genes and is one of the most abundant DNA-binding proteins in enterobacteria. The mechanism of eae and tir regulation in A/E bacteria is less clear at this stage. Neither eae nor tir is contained on the polycistronic operons of LEE described earlier. Per activates the expression of eae in EPEC, but it appears to activate indirectly or requires additional factors (19, 38, 51). However, no per homologue has been detected in STEC (19), although it is possible that an analogous regulator exists.

The majority of STEC isolates associated with serious human gastrointestinal infections carry eae, although a number of cases of severe STEC disease complicated by HUS (including one recent outbreak) have been attributed to eae-lacking STEC strains (44, 45). In addition, the presence of eae in STEC strains does not always directly correlate with the ability to adhere to intestinal epithelial cells in vitro (43). Moreover, Wieler et al. (56) have reported that not all eae-positive STEC strains isolated from cattle were capable of producing A/E lesions in vitro, as judged by the fluorescent actin staining (FAS) assay. In previous studies we have examined the adherence properties of STEC strains associated with an outbreak of HUS caused by contaminated fermented sausage (42). These included an O111:H− strain, 95NR1, and an O157:H− strain, 95SF2, both of which were eae positive and exhibited a similar capacity to adhere to Henle 407 cells in a low-dose 3-h assay (43). In the present study, these strains were examined for capacity to produce A/E lesions on HEp-2 cells using a 6-h FAS assay. While 95NR1 was shown to be A/E positive, 95SF2 did not adhere in significant numbers and did not produce lesions in this assay. We show here that 95SF2 carries a defective ler gene with a single base change with respect to that published previously for ler of the A/E positive O157:H7 STEC strain EDL933 (46).

However, 95SF2 is able to adhere and produce A/E lesions in a FAS assay when EDL933 ler is expressed from a multicopy plasmid. While we show that ler increases the level of intimin in O157 STEC, the inability of 95SF2 to adhere in a FAS assay was shown to be independent of intimin. Thus, the product of ler appears to enhance intimin-independent adherence in O157 STEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and cloning vectors.

E. coli cloning hosts used were DH5α (supE44 ΔlacU169 [φ80 lacZ ΔM15] hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1) and SM10λpir (thi thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tc::Mu Km). STEC strains 95NR1 (O111:H−) and 95SF2 (O157:H−) were isolated from the Women's and Children's Hospital, North Adelaide, South Australia, Australia, as described previously (40). STEC strain EDL933 (O157:H7) has also been described previously (45). All E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (unless otherwise indicated) at 37°C, supplemented with 50 μg of ampicillin or kanamycin ml−1, where appropriate. Vectors pGEM-7Zf(+) and pGEM-Teasy were obtained from Promega Biotech, Madison, Wis. These vectors are essentially the same, with the exception that pGEM-Teasy has single 3′ T overhangs and exists only in the linear form, and so pGEM-7Zf(+) was used as a negative control in experiments described here. Phagemid pBluescript KS was obtained from Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif. M13 minimal medium was prepared as described by Miller (39) and supplemented prior to use with MgSO4, glucose, and thiamine-HCl to final concentrations of 0.2 mg ml−1, 0.5% (wt/vol), and 50 μg ml−1, respectively.

Purification of O157 intimin and preparation of anti-intimin (α-O157Int).

Intimin of O157 was purified using the QIAexpressionist His6 fusion protein system (Qiagen Inc.). The His6 tag was fused to the N-terminal region of intimin, removing 40 amino acids of the intimin N terminus to delete any potential signal sequence that may lead to cleavage of the His6 tag (19). O157 eae was PCR amplified using oligonucleotides MO7 (5′-GATAGGATCCGAATTCATTTGCAAATGGTG-3′) and MO8 (5′-AGCTAAGCTTATTCTACACAAACCGCAT-3′), which incorporate BamHI and HindIII restriction sites (underlined), respectively. The PCR product then was digested with BamHI/HindIII and ligated into the BamHI and HindIII sites of pQE-31 (Qiagen). This mix was transformed into E. coli SG 13009(pREP4) (20), and clones were selected by plating on kanamycin and ampicillin. pQE-31 carrying eae was designated pJCP716, and the fusion of the His6 tag to the N terminus was confirmed by sequencing. For large-scale purification of the His6-O157 intimin fusion protein, log-phase cultures (0.25 to 1 liter) of SG 13009(pJCP716) in LB broth were induced by the addition of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (2 mM) and grown for a further 3 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 5 ml of 6 M guanidine-HCl–0.1 M disodium hydrogen orthophosphate–0.01 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) per g (wet weight) and stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The cell lysate was then centrifuged (10,000 × g for 25 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a 4-ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid column preequilibrated with 5 column volumes of buffer A (0.5 M NaCl, 15 mM imidazole) at a rate of 15 ml per h. The column was washed with 10 column volumes of buffer A, 5 column volumes of buffer B (8 M urea, 0.1 M disodium hydrogen orthophosphate, 0.01 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]), and 4 column volumes of buffer C (8 M urea, 0.1 M disodium hydrogen orthophosphate, 0.01 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.3], 0.25 M NaCl, 5 mM imidazole). Intimin was eluted from the column using a 0 to 500 mM imidazole gradient, and 3-ml fractions were collected and stored at 4°C for analysis by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). After analysis, the appropriate fraction was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against a decreasing concentration of urea, with dialysis continuing for a further 4 h in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.5. Glycerol (50%, vol/vol) was added to the refolded intimin protein, which was then stored at −15°C.

BALB/c mice were immunized with three doses of 10 μg of purified intimin in Freund's adjuvant at 2-week intervals. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture 2 weeks after the last immunization, and serum was stored at 4°C.

FAS assay and confocal microscopy.

The FAS assay used was a modification of that described by Knutton et al. (31) and was performed in triplicate. HEp-2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) buffered with 20 mM HEPES supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin ml−1, 100 μg of streptomycin ml−1, and 2 mM l-glutamine. The HEp-2 cells were then used to seed 1.0-cm-diameter coverslips in 24-well trays and were incubated until the monolayer was semiconfluent. Monolayers were washed to remove all antibiotics and were infected with the various strains diluted in DMEM to a density of 2 × 105 CFU ml−1. After 3 h at 37°C, the cells were washed three times with Dulbecco's PBS and fresh medium was added. The cells were incubated for an additional 3 h at 37°C and washed three times with Dulbecco's PBS and then fixed in PBS–3.7% formaldehyde. The cells were permeabilized by treatment with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min, washed with PBS, and stained with rabbit antiserum specific for the respective O-antigen type (Oxoid) (diluted 1:100) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The coverslips were washed and incubated at 37°C for 1 h with a combination of goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-Texas Red conjugate (diluted 1:100; Molecular Probe [Quantum Scientific]) and phalloidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (diluted 1:200; Sigma Chemical Co.). The coverslips were mounted on glass slides with Moviol containing 2% (vol/vol) antibleach (Sigma) and sealed with clear nail polish. The cells were examined with a Bio-Rad MRC600 confocal microscope with a krypton-argon laser. Confocal images were processed using Confocal assist software.

Construction of Δeae derivatives of 95SF2 and EDL933.

Two fragments flanking eae were generated by two separate PCRs using chromosomal DNA from either 95SF2 or EDL933 as template. Fragment 1 was 1.87 kb long and was generated using oligonucleotides 3005 (5′-CTTCAGATATCACGGAAGC-3′) and 3006 (5′-CTGAAGCTTGTGCCGGGTCCGGGT-3′), which incorporate EcoRV and HindIII restriction sites (underlined), respectively. Fragment 2 was 2.0 kb long and was generated using oligonucleotides 3007 (5′-GTCAAGCTTCCTGGGGTTAATGTT-3′) and 3008 (5′-TCACCCGGGCATGTTGCCAAACATC-3′), which incorporate HindIII and SmaI restriction sites (underlined), respectively. Fragment 1 was digested with EcoRV/HindIII, and fragment 2 was digested with HindIII/SmaI. These two fragments were then coligated into the SmaI site pCVD442 (15). The ligation of these two fragments at the HindIII site generates an in-frame deletion of O157 eae, such that 2,716 nucleotides (nt) are removed from the open reading frame, fusing the DNA encoding the 12 N-terminal amino acids of intimin with that encoding 17 amino acids of the C terminus. The resultant construct, pJCP714, was electroporated into SM10λpir, and transformants were selected with ampicillin. pJCP714 was then conjugated from SM10λpir into STEC O157. Overnight cultures of donor and recipient strains were mixed at a ratio of 1:10, and the cells were pelleted by gentle centrifugation. The pellet was gently resuspended in 200 μl of broth and spread onto a cellulose acetate membrane filter (0.45-μm pore size; type HA; Millipore Corp.) on LB agar and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. The cells were resuspended in 10 ml of saline, and aliquots were plated onto M13 minimal agar plates (which select for the STEC recipient strain). The mutant construction strategy is based on that described by Donnenberg and Kaper (12) but with some variations. An overnight culture of an exconjugate was plated onto LB agar (supplemented with 6% sucrose, but without NaCl) and incubated overnight at 30°C. Ampicillin-sensitive colonies were selected and screened by PCR. Δeae O157 mutants produced a 0.15-kb PCR product using oligonucleotides eaeF (5′-CTCATCTAACTCATTGTGGG-3′) and eaeR (5′-AAAATATAATATATTTTTAGCCGG-3′). The in-frame deletion was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Construction of plasmid-borne ler.

The ler genes were PCR amplified from EDL933 and 95SF2 chromosomal DNA using oligonucleotides M31 (5′-CCTCCAGCTCAGTTATCGTT-3′) and M32 (5′-ATAACATTCCGGGTTGGTGA-3′). The 2.4-kb PCR products were ligated to pGEM-Teasy, transformed into DH5α, and selected using ampicillin. The constructs generated from EDL933 and 95SF2 were designated pJCP710 and pJCP711, respectively. The EcoRI fragment of pJCP710 was isolated and ligated into the EcoRI site of pBluescript KS to generate pJCP712. The EcoRI sites of pJCP710 lie 893 bp upstream of the start codon of ler and downstream in the vector polylinker. pJCP713 was generated as described for pJCP710, except oligonucleotide M35 (5′-TTTGATGAAATAGATGTGTCC-3′) was used instead of M32.

Detection of intimin by Western immunoblotting.

Cultures of bacteria were grown to an A600 of 0.6 to 0.8, and bacterial cultures were adjusted to comparable optical densities prior to gel loading. Whole-cell lysates were prepared by centrifugation of 1 ml of the culture and resuspending in 100 μl of SDS sample buffer. Protein samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE (34), and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blot analysis as described elsewhere (41). Filters were probed with α-O157Int antiserum obtained as described above (diluted 1:2,000), followed by goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G conjugated to alkaline phosphatase as described previously (41).

RESULTS

A/E adherence phenotype and intimin induction in eae-positive STEC strains.

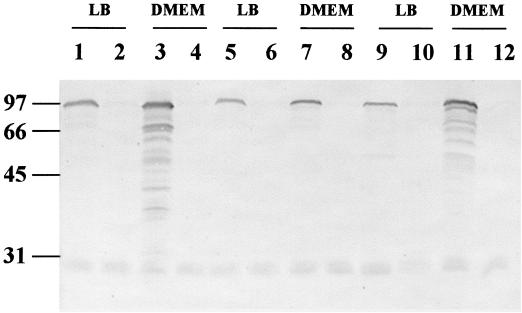

Initial experiments compared the capacities of the eae-positive STEC strains 95SF2, 95NR1, and EDL933 to produce A/E lesions on HEp-2 cells, using the FAS assay, as described in Materials and Methods. Both 95NR1 and EDL933 produced typical A/E lesions, but none were observed for cells infected with 95SF2. Moreover, in spite of the previously observed capacity of 95SF2 to adhere to Henle 407 cells, very few adherent bacteria were observed on the HEp-2 cell surface, and those that did adhere exhibited an abnormal, filamentous phenotype (result not shown). We then examined the possibility that the failure of 95SF2 to adhere to cultured HEp-2 cells in the FAS assay is related to the level of intimin produced by the bacteria. In EPEC, intimin is known to be induced during log-phase growth, and the level increases when cells are grown in tissue culture medium such as DMEM (30). Therefore, to ensure maximal expression of intimin in the STEC strains under study, cells were grown to mid-log phase in either LB broth or DMEM. Cell lysates were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis using mouse antiserum raised against intimin of STEC 95SF2 (α-O157Int). The deduced amino acid sequence of intimin of 95SF2 is 99.9% identical to that of EDL933, while intimin of 95NR1 exhibits 88.6% identity (55). LB culture lysates of all three STEC strains contained similar levels of an immunoreactive species of the expected size (Fig. 1, lanes 1, 5, and 9). Interestingly, DMEM culture lysates of 95NR1 and EDL933 contained significantly increased levels of the immunoreactive species relative to the respective LB culture lysates, and there was evidence of proteolytic degradation (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 11). However, no such increase in the level of intimin expression was observed in the DMEM culture lysate of 95SF2 relative to the LB culture lysate (Fig. 1, lane 7). The absolute specificity of the antiserum for intimin was confirmed by the absence of immunoreactive species in either LB or DMEM culture lysates of derivatives of each of the STEC strains carrying eae in-frame deletion mutations (constructed as described in Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1, lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12). Thus, although 95SF2 does produce baseline levels of intimin, it is unable to up-regulate expression when grown in DMEM.

FIG. 1.

Western immunoblot analysis of STEC strains grown in either LB broth or DMEM (as indicated). Cells were harvested at mid-log phase, and whole-cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and probed with α-O157Int antiserum. The mobilities of protein size markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated at left. Lanes 1 and 3, O111:H− STEC 95NR1; lanes 2 and 4, 95NR1Δeae; lanes 5 and 7, O157:H− STEC 95SF2; lanes 6 and 8, 95SF2Δeae; lanes 9 and 11, O157:H7 STEC EDL933; lanes 10 and 12, EDL933Δeae.

DMEM appears to mimic an environmental cue for A/E-producing bacteria, and the levels of several EPEC and STEC secreted proteins (Esp), which are crucial for generation of these lesions, also increase when cells are grown in DMEM (5, 17, 23). It is plausible, therefore, that the lack of induction of intimin in 95SF2 grown in DMEM may reflect a defect in the regulatory pathway which responds to environmental signals. It is also possible that the baseline level of intimin expression seen in 95SF2 is sufficient and that inability of 95SF2 to generate A/E lesions is due to failure to produce one or more of the Esp proteins. 95SF2 was originally isolated from a patient with HUS who was also infected with an O111:H− STEC indistinguishable from 95NR1 (42), raising the possibility of in trans complementation in vivo. HEp-2 cells were therefore coinfected with both 95SF2 and 95NR1 and examined by FAS assay. The coinfection was performed in duplicate, and the fixed cells were also incubated with either anti-O111 or anti-O157 serum, which was then detected by a second antibody conjugated to Texas Red, in order to distinguish between the two STEC strains. 95NR1 cells produced a positive FAS response, but 95SF2 was still unable to adhere significantly and did not produce A/E lesions (result not shown). Thus, coincubation of 95NR1 with 95SF2 was unable to complement the defect in 95SF2 in trans.

Sequence analysis of 95SF2 ler.

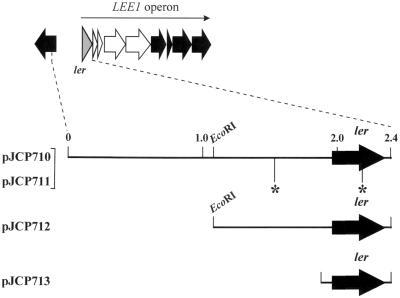

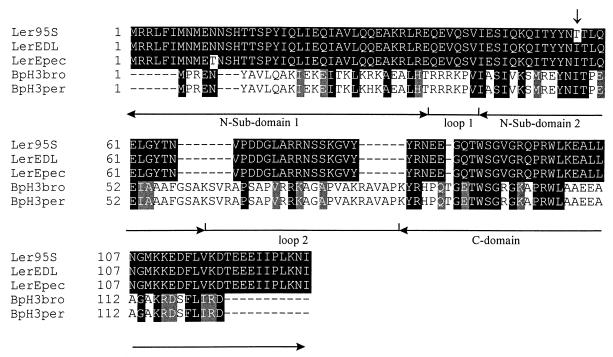

In view of the possibility that STEC 95SF2 has a regulatory defect, we examined the ler gene of this strain. A 2.4-kb fragment containing ler and 1.8 kb of noncoding 5′ flanking DNA from 95SF2 was amplified by PCR and cloned into pGEM-Teasy (generating plasmid pJCP711) (Fig. 2). Comparison of the DNA sequence of the 2.4-kb insert of pJCP711 with that for the homologous region of EDL933 (46) revealed two base changes. One of these (C1593 to T) lies 395 nt upstream of the ATG start codon of ler. The other (T2157 to C) is 170 nt downstream of the initiation codon and results in an Ile57-to-Thr substitution. The positions of the mutations within pJCP711 are shown in Fig. 2. The deduced amino acid sequence of 95SF2 ler was 98% identical to Ler (Orf1) of EPEC (18), and 48 and 47% identical to the BpH3 proteins from Bordetella bronchiseptica (6) and B. pertussis (21), respectively. 95SF2 Ler also shows similarity with H-NS of Erwinia chrysanthemi (50% identity) (GenBank accession number CAA61611), and the H-NS-like StpA DNA-binding proteins of E. coli (48% identity) (59) and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (46% identity) (GenBank accession number O33800). It has recently been shown that despite low sequence homology, BpH3, StpA, and the trans-activator protein HvrA of Rhodobacter capsulatus (9) are structurally and functionally related to H-NS proteins and therefore all belong to the H-NS family (6). The sequence alignment of 95SF2 Ler with Ler of EDL933 and EPEC and the BpH3 proteins of Bordetella show that the Ile57 residue is conserved in all these H-NS-like proteins except for 95SF2 Ler (Fig. 3). Ile57 is also conserved in StpA of E. coli and Salmonella and H-NS of E. chrysanthemi (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the various ler constructs. The position of pJCP710 relative to the LEE1 operon of EPEC LEE (38) is shown at the top. The ler-containing fragments of pJCP710, pJCP712, and pJCP713 were isolated from the STEC strain EDL933. The ler-encoding fragment of pJCP711 was isolated from the STEC strain 95SF2. Asterisks denote the location of the nucleotide differences between pJCP710 and pJCP711. The sizes of the fragments are shown in kilobases.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of STEC 95SF2 Ler with other H-NS-like proteins. The alignment of the amino acid sequences was performed using CLUSTAL (22). Identical residues are shaded black; residues with similar properties are shaded grey. Gaps (dashes) have been introduced by the program to optimize the alignment. The arrow denotes the Ile57-to-Thr conversion of 95SF2 Ler. The N- and C-terminal subdomains of BpH3 are indicated below the consensus. Abbreviations: Ler95S, STEC 95SF2 Ler; LerEDL, STEC EDL933 Ler; LerEpec, EPEC Ler; BpH3bro, B. bronchiseptica BpH3; BpH3per, B. pertussis BpH3.

H-NS consists of an N-terminal oligomerization domain (54, 57) and a C-terminal DNA-binding domain (49). It has recently been proposed that these domains can be further subdivided, and the subdomains of BpH3 are shown in Fig. 3. The N-terminal domain is made up of two subdomains, separated by a loop (loop 1), and the N-terminal domain is linked to the C-terminal domain by a second loop (loop 2) (6). Loop 2 is a protease-sensitive linker (11). Based on the model presented by Bertin et al. (6), amino acid 57 of Ler lies in the second subdomain of the N-terminal oligomerization domain, and so the Ile57-to-Thr substitution in 95SF2 Ler may interfere with oligomerization.

Phenotypic characterization of O157 STEC strains 95SF2 and EDL933 carrying various ler constructs.

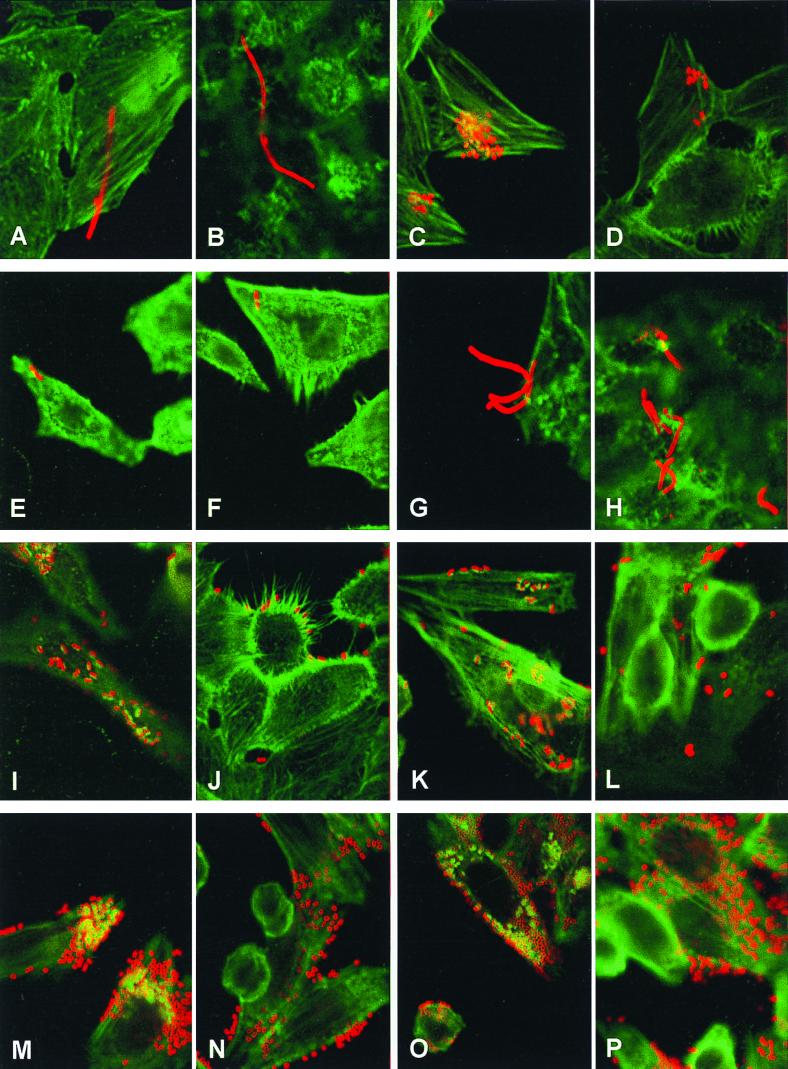

To examine the possibility that the nucleotide differences in the ler region described above account for the abnormal phenotype of 95SF2 in the FAS assay, the analogous ler region from EDL933 was also cloned into pGEM-Teasy, generating pJCP710. Two smaller clones (designated pJCP712 and pJCP713) containing EDL933 ler plus 0.8 and 0.1 kb of 5′ flanking DNA, respectively, were also constructed (Fig. 2). The various ler-containing constructs were electroporated into 95SF2 and EDL933, and the capacities of the transformants to adhere to and produce A/E lesions on HEp-2 cells were assessed. The impact of expression of the various ler constructs in the otherwise isogenic eae deletion derivatives of 95SF2 and EDL933 (designated 95SF2Δeae and EDL933Δeae) was also examined. The growth rate of bacterial cultures harboring the various ler constructs was measured and was comparable to the growth rate of wild-type strains (data not shown). Confocal micrographs of HEp-2 cells infected with the various STEC constructs after FAS assay are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Confocal micrographs showing the interaction of STEC strains with HEp-2 cells (magnification, approximately ×1,900). The red fluorescence shows bacteria and is due to staining with rabbit anti-O157 antigen followed by goat anti-rabbit Texas Red. The green fluorescence shows actin filaments and is due to phalloidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate staining. (A) 95SF2; (B) 95SF2Δeae; (C) EDL933; (D) EDL933Δeae; (E) 95SF2(pJCP711); (F) 95SF2Δeae(pJCP711); (G) EDL933(pJCP711); (H) EDL933Δeae(pJCP711); (I) 95SF2(pJCP710); (J) 95SF2Δeae(pJCP710); (K) EDL933(pJCP710); (L) EDL933Δeae(pJCP710); (M) 95SF2(pJCP713); (N) 95SF2Δeae(pJCP713); (O) EDL933(pJCP713); (P) EDL933Δeae(pJCP713).

The STEC 95SF2 wild-type strain and its Δeae derivative did not bind to the HEp-2 cells in significant numbers (approximately one to five bacteria per HEp-2 cell), and the majority of bacteria that did bind had divided incompletely, producing the filamentous phenotype referred to earlier (Fig. 4A and B, respectively). However, 95SF2 (pJCP710) (carrying EDL933 ler) adhered to HEp-2 cells and produced A/E lesions, characterized by an intense region of polymerized actin (green fluorescence) corresponding in both size and position with adherent bacteria (red fluorescence) (Fig. 4I). It should be noted, however, that not all adherent bacteria produced A/E lesions. Interestingly, 95SF2Δeae(pJCP710) was also able to adhere to HEp-2 (Fig. 4J), which suggests that the pJCP710-mediated adherence does not depend on intimin. However, the numbers of adhered bacteria were slightly less than that of 95SF2(pJCP710), and bacteria often bound to the edges of the HEp-2 cells (Fig. 4J). The phenotypes of 95SF2(pJCP712) and 95SF2Δeae(pJCP712) were the same as those seen in Fig. 4I and 4J, respectively (result not shown).

Interestingly, however, the capacity of 95SF2 to adhere and produce A/E lesions on HEp-2 cells in the FAS assay was greatly enhanced by pJCP713 (Fig. 4M). This plasmid differs from the other EDL933 ler constructs in the length of the 5′ region (100 bp, compared with 1.8 and 0.8 kb for pJCP710 and pJCP712, respectively). The image shown in Fig. 4M represents only one focal plane. However, examination of higher and lower focal planes indicated the presence of adherent bacteria, as well as associated A/E lesions, over almost the entire surface of the HEp-2 cells. This up-regulation of adherence was also intimin independent, as seen with 95SF2Δeae(pJCP713) in Fig. 4N. The fact that pJCP713 can complement the abnormal phenotype of 95SF2 indicates that the amino acid substitution in 95SF2 Ler, rather than the nucleotide substitution 395 nt upstream of ler, is entirely reasonable for the observed effects. 95SF2 containing either cloning vectors pBluescript KS or pGEM-7Zf(+) have the same adherence (FAS) phenotype as that of the wild-type strain (data not shown). The expression of 95SF2 ler from the multicopy plasmid pJCP711 in both 95SF2 and its Δeae derivative did not induce adherence to the HEp-2 cells (Fig. 4E and 4F). While the bacteria shown in these two panels appear normal, others were present in the filamentous form seen in Fig. 4A and B (result not shown).

EDL933 produces A/E lesions, as judged by a positive FAS assay (Fig. 4C). Overall adherence was reduced in EDL933Δeae, and as expected, there were no A/E lesions (Fig. 4D). A similar finding has been reported by McKee et al. (37). The phenotypes of EDL933 and EDL933Δeae carrying either pBluescript KS or pGEM-7Zf(+) were the same as the parental strains (data not shown). EDL933(pJCP710) showed a slight increase in adherence and ability to produce A/E lesions, over and above that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 4K). EDL933Δeae(pJCP710) also showed increased adherence (Fig. 4L) compared to EDL933Δeae. pJCP712 did not significantly enhance the adherence of EDL933 or its Δeae derivative in the FAS assay (data not shown). However, the ability of EDL933 to adhere to HEp-2 cells and produce A/E lesions was greatly enhanced by the presence of pJCP713 (Fig. 4O), an effect similar to that seen with 95SF2(pJCP713) (Fig. 4M). Again, the enhancement of adherence was not intimin dependent, as shown for EDL933Δeae(pJCP713) in Fig. 4P.

Surprisingly, EDL933(pJCP711) (expressing 95SF2 ler) exhibited a 95SF2-like phenotype in the FAS assay. The number of EDL933(pJCP711) cells adhering to HEp-2 was greatly reduced, and these displayed the filamentous phenotype (Fig. 4G) normally associated with 95SF2; A/E lesions were also not observed. The phenotype of EDL933Δeae(pJCP711) was similar to that of EDL933(pJCP711) (Fig. 4H).

The presence of ler increases the level of intimin in STEC O157.

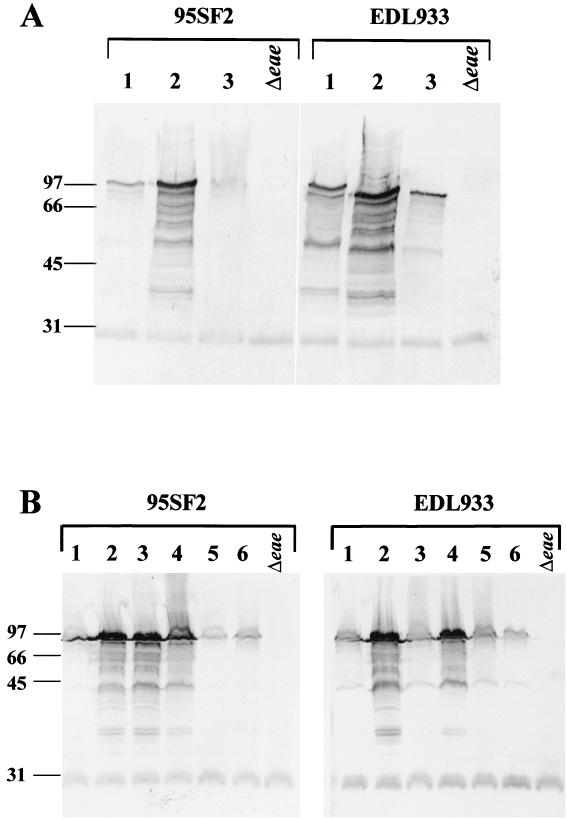

The ler gene clearly plays a significant role in LEE-associated functions, as shown here and elsewhere (36). However, it is not yet known whether ler affects the levels of intimin in O157 STEC. To determine this, O157 strains 95SF2 and EDL933 carrying ler-bearing plasmids were subjected to Western immunoblot analysis. Whole-cell lysates of log-phase cultures were subjected to SDS-PAGE and probed with α-O157Int. Figure 5A clearly shows that the levels of intimin in 95SF2 and EDL933 increase when these strains carry pJCP710 (which carries the gene encoding EDL933 Ler), but this was not seen in cells carrying pJCP711 (the otherwise identical construct which carries the gene encoding 95SF2 Ler).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the intimin levels of STEC strains 95SF2 and EDL933 expressing plasmid-borne ler. α-O157Int antiserum was used to probe Western blots of STEC whole-cell lysates carrying various ler-expressing constructs. The Δeae derivatives of 95SF2 and EDL933 are indicated. The mobilities of protein size markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated at left. (A) Lane 1, pGEM-7Zf(+); lane 2, pJCP710; lane 3, pJCP711. (B) Lane 1, no plasmid; lane 2, pJCP710; lane 3, pJCP712; lane 4, pJCP713; lane 5, pGEM-7Zf(+); lane 6, pBluescript KS.

Both pJCP712 and pJCP713 were able to direct an increase in intimin levels in 95SF2, and the level of induction was similar to that seen with pJCP710 (Fig. 5B). Thus, the inability of 95SF2 to up-regulate intimin expression, as well as its inability to adhere and produce A/E lesions in the FAS assay, can be attributed to the single amino acid substitution in Ler. However, pJCP713, but not pJCP712, increased the intimin levels of EDL933 (Fig. 5B). This correlates with the observations described above for the FAS assay (pJCP712 directed increased adherence of 95SF2 and its Δeae derivative but did not enhance the adherence of EDL933 or its Δeae derivative). H-NS consensus sites (5′-TNTNAN-3′) (48) are located upstream of eae (data not shown); however, it is not known whether these sites are involved with Ler binding. It should also be noted that H-NS binds to AT-rich DNA, which is usually naturally curved (35), and both the region 5′ to eae and the coding region itself are unusually AT rich for E. coli DNA (63 and 65% A+T, respectively). Several copies of the consensus sequence are also located upstream of the enterohemorrhagic E. coli espA gene (5).

DISCUSSION

The capacity to cause A/E lesions on intestinal epithelial cells is considered to be an important accessory factor, if not an essential virulence determinant, of STEC strains such as those belonging to serogroup O157 (40). Production of intimin, encoded by eae, has been a commonly used marker for this capacity. However, generation of A/E lesions requires coordinate regulation of expression of eae and many other LEE-encoded genes. Lesion formation is also believed to be preceded by adherence of the bacterium to the epithelial cell surface. Studies of EPEC strains have demonstrated that the LEE-encoded regulatory protein Ler acts as a direct transcriptional activator of several polycistronic LEE operons (38). However, the role of ler in STEC has yet to be fully defined, and furthermore, up-regulation of eae itself has not been previously demonstrated in STEC.

In the present study, we have examined the molecular basis for the failure of an eae-positive O157 STEC strain (95SF2), isolated from a patient with HUS, to generate A/E lesions on HEp-2 cells in vitro. This strain also exhibited a diminished capacity to adhere to the surface of these cells and displayed an abnormal filamentous phenotype suggestive of a defect in cell division. 95SF2 was capable of producing levels of intimin similar to those of other STEC strains such as 95NR1 and EDL933 (which can form A/E lesions) when grown in LB broth. However, unlike these two strains, 95SF2 did not exhibit increased intimin production when grown in DMEM, implying a defect in a regulatory pathway. Cloning and sequence analysis of 95SF2 ler revealed the presence of a single nucleotide difference with respect to EDL933 ler, resulting in an Ile57-to-Thr substitution. Introduction of EDL933 ler on the multicopy plasmid pJCP710, pJCP712, or pJCP713 into 95SF2 conferred normal cell morphology, increased intimin levels, and the capacity to produce A/E lesions. It also resulted in massively increased adherence of bacteria to the HEp-2 cell surface in the deletion derivative 95SF2Δeae. Introduction of EDL933 ler on a multicopy plasmid also further enhanced adherence and the A/E capacity of EDL933, as well as adherence in the deletion derivative EDL933Δeae. Conversely, introduction of 95SF2 ler on pJCP711 into 95SF2 did not correct any of the phenotypic defects of this strain. Interestingly, introduction of this 95SF2 ler plasmid into EDL933 conferred a phenotype indistinguishable from that of 95SF2, i.e., abnormal filamentous cell morphology, inability to increase intimin levels, lack of adherence to HEp-2 cells, and failure to form A/E lesions.

The data presented here and elsewhere support the proposal that Ler of STEC and EPEC belong to the H-NS family of global regulators (16, 38). Ler shows similarities with the H-NS-like proteins BpH3 of B. bronchiseptica (6) and B. pertussis (21) and the StpA proteins of E. coli (59) and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (GenBank accession number 033800). While members within the enterobacterial H-NS group exhibit strong amino acid conservation (2), H-NS-like proteins (BpH3, StpA, and HvrA) exhibit only weak amino acid conservation with H-NS (6). However, despite the low level conservation of H-NS with that of H-NS-like proteins, they are functionally and structurally related DNA-binding proteins (6). H-NS can be divided into two functional domains: an N-terminal oligomerization domain and a C-terminal DNA-binding domain. The requirement of the N-terminal domain for oligomerization has been demonstrated both in vivo and in vitro (54, 57). The mutation in 95SF2 Ler lies within the N-terminal domain, and while there is virtually no homology between the N-terminal domain of Ler and that of H-NS, we suggest that there may be functional conservation, based on the similarities of Ler with BpH3. Despite the low amino acid conservation of the N-terminal domain of BpH3 compared with H-NS, the N-terminal domain of BpH3 can functionally complement the N-terminal domain of H-NS (6). In addition, the N-terminal domains of BpH3 and H-NS appear to be structurally conserved, and these domains can be cross-linked to form dimers in vitro (6). It is therefore likely that the mutation in 95SF2 lies within an oligomerization domain that is required for the proper functioning of Ler.

Clearly, studies here show the plasmid-borne allele of ler is dominant to the chromosomal allele, such that plasmid-borne ler determines whether the cell exhibits a Ler-negative or Ler-positive phenotype. This suggests that the level of protein expression determines the phenotype and that Ler encoded by a gene carried by the plasmid is capable of competing with and/or displacing the endogenous Ler. Thus, while the defective 95SF2 Ler may be able to bind DNA, it may be unable to function due the inability to oligomerize. Functional and nonfunctional Ler would therefore compete for the DNA-binding site. Interestingly, Ler also appears to be involved in cell division, thereby influencing gene expression outside of LEE. This is not entirely surprising, as H-NS proteins are known to modulate the expression of a large number of unrelated genes in enterobacteria, which is reflected by the pleiotropic phenotypes displayed by hns mutants (4, 7, 58).

Studies here show that the overexpression of ler in O157 STEC increases the levels of intimin. Generally, the best-characterized H-NS-regulated genes are negatively regulated by H-NS. However, two-dimensional protein analysis has suggested that there are also many uncharacterized genes which are positively regulated by H-NS (1, 8). Potential H-NS consensus binding sites were located upstream of eae, and these binding sites overlap the predicted −10 and −35 promoter elements. In other instances where the binding site overlaps the promoter, H-NS represses the expression of the gene, presumably by interfering with the binding of the RNA polymerase to the promoter (35, 52, 53). Therefore, the mechanism by which intimin is regulated by Ler is unclear at this stage. Further experiments are needed to establish whether Ler transcriptionally regulates intimin, or alternatively, whether Ler represses the expression of a gene whose product normally degrades intimin.

The region upstream of ler may have a role in the expression of ler itself. Both pJCP710 and pJCP713 carry EDL933 ler but vary in the length of the upstream region (approximately 2.0 kb and 100 bp, respectively). However, pJCP713 produced the greatest enhancement of adherence and A/E lesion formation when expressed in either EDL933 or 95SF2. It is possible that the region upstream of ler contains a negative regulatory element, such that deletion of this region allows greater expression of ler from pJCP713.

While there is a substantial body of evidence that intimin is essential for the intimate attachment of bacteria to epithelial cells at the site of A/E lesions, it is not clear whether intimin is involved in the initial adherence which is believed to precede these events (13). The findings of the present study using otherwise isogenic eae deletion derivatives of 95SF2 and EDL933 unequivocally demonstrate that O157 STEC can adhere efficiently to HEp-2 cells in the absence of intimin and that this is regulated by ler. Ebel et al. (17) have recently shown that the initial binding of STEC to host cells is mediated by filamentous structures, of which EspA is a major component. During an STEC infection, these EspA structures are found predominantly on bacteria that have not yet induced the formation of A/E lesions, and a deletion mutant of espA in an O26:H− STEC strain almost completely abolished adherence to HeLa cells and ability to induce actin rearrangements (17). EspD is essential for the formation of these EspA filaments, and consequently an STEC espD mutant also exhibits impaired attachment to HeLa cells (33). EspA filamentous structures are found on the surface of both EPEC and STEC and are required for the translocation of EspB and Tir into epithelial cells and for the activation of epithelial signal transduction (29, 32, 50). espA is contained within the polycistronic operon LEE4 of EPEC, which is modestly up-regulated by ler (38). It is therefore conceivable that the expression of ler from a multicopy plasmid in STEC up-regulates one or more of the Esp molecules, resulting in the up-regulation of intimin-independent adherence. It has been proposed that while EspA appendages mediate the initial interaction of STEC with the host cell, this is later replaced by the intimate attachment mediated by intimin (17). It should be noted, however, that in EPEC the deletion of espA does not eliminate the ability to adhere to host cells, but A/E lesion formation is abolished (29). We cannot rule out the possibility that ler is up-regulating an alternate adherence factor that is not encoded by the LEE locus.

We have demonstrated that in STEC, ler plays a crucial role in both the above processes, as well as impacting on gross cell morphology. However, the fact that 95SF2 (in which ler is clearly defective) was one of two STEC strains isolated from a patient with severe HUS and the frequent occurrence of cases of serious gastrointestinal disease and HUS caused by LEE-negative STEC indicate that the precise role and contribution of ler and other LEE genes in the pathogenesis of human disease remain to be elucidated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Matthew Woodrow for assistance with raising antisera and to Luisa van den Bosch for helpful advice with microscopy.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abaibou H, Pommier J, Benoit S, Giordano G, Mandrand-Berthelot M A. Expression and characterization of the Escherichia coli fdo locus and a possible physiological role for aerobic formate dehydrogenase. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7141–7149. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7141-7149.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler B, Sasakawa C, Tobe T, Makino K, Komatsu K, Yoshikawa M. A dual transcriptional activation system for the 230 kb plasmid genes coding for virulence-associated antigens of Shigella flexneri. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:627–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlung T, Ingmer H. H-NS: a modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3151679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barth M, Marschall C, Muffler A, Fischer D, Hengge-Aronis R. Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of ςS and many ςS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3455–3464. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3455-3464.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltrametti F, Kresse A U, Guzman C A. Transcriptional regulation of the esp genes of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3409–3418. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3409-3418.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertin P, Benhabiles N, Krin E, Laurent-Winther C, Tendeng C, Turlin E, Thomas A, Danchin A, Brasseur R. The structural and functional organization of H-NS-like proteins is evolutionarily conserved in gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:319–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertin P, Lejeune P, Laurent-Winther C, Danchin A. Mutations in bglY, the structural gene for the DNA-binding protein H1, affect expression of several Escherichia coli genes. Biochimie. 1990;72:889–891. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(90)90008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertin P, Terao E, Lee E H, Lejeune P, Colson C, Danchin A, Collatz E. The H-NS protein is involved in the biogenesis of flagella in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5537–5540. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5537-5540.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buggy J J, Sganga M W, Bauer C E. Characterization of a light-responsive trans-activator responsible for differentially controlling reaction center and light-harvesting-1 gene expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6936–6943. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.6936-6943.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bustamente V H, Calva E, Puente J L. Analysis of cis-acting elements required for bfpA expression in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3013–3016. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.3013-3016.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cusick M E, Belfort M. Domain structure and RNA annealing activity of the Escherichia coli regulatory protein StpA. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:847–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4310–4317. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4310-4317.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Finlay B B. Interactions between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and host epithelial cells. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:109–114. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnenberg M S. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. In: Blaser M J, Smith P D, Ravdin J I, Greenberg H B, Guerrant R L, editors. Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 709–726. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorman C J, Porter M E. The Shigella virulence gene regulatory cascade: a paradigm of bacterial gene control mechanisms. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:677–684. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorman C J, Hinton J C, Free A. Domain organization and oligomerization among H-NS-like nucleoid-associated proteins in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebel F, Podzadel T, Rohde M, Kresse A U, Krämer S, Deibel C, Guzman C A, Chakraborty T. Initial binding of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli to host cells and subsequent induction of actin rearrangements depend on filamentous EspA-containing surface appendages. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:147–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott S J, Wainwright L A, McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Deng Y, Lai L, McNamara B P, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli E2348/69. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gómez-Duarte O G, Kaper J B. A plasmid-encoded regulatory region activates chromosomal eaeA expression in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1767–1776. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1767-1776.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottesman S, Halpern E, Trisler P. Role of sulA and sulB in filamentation by lon mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:265–273. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.1.265-273.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyard S, Bertin P. Characterization of BpH3, an H-NS like protein in Bordetella pertussis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:815–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3891753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins D G, Sharp P M. CLUSTAL: a package for performing multiple sequence alignments on a microcomputer. Gene. 1988;73:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarvis K G, Kaper J B. Secretion of extracellular proteins by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli via a putative type III secretion system. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4826–4829. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4826-4829.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarvis K G, Giron J A, Jerse A E, McDaniel T K, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli contains a specialized secretion system necessary for the export of proteins involved in attaching and effacing lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7996–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jerse A E, Yu J, Tall B D, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karmali M A. Infection by verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:15–38. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenny B, Finlay B B. Protein secretion by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is essential for transducing signals to epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7991–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenny B, DeVinney R, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Frey E A, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenny B, Lai L-C, Finlay B B, Donnenberg M S. EspA, a protein secreted by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, is required to induce signals in epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knutton S, Adu-Bobie J, Bain C, Phillips A D, Dougan G, Frankel G. Down regulation of intimin expression during attaching and effacing enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adhesion. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1644–1652. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1644-1652.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knutton S, Baldwin T, Williams P H, McNeish A S. Actin accumulation at sites of bacterial adhesion to tissue culture cells: basis of a new diagnostic test for enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1290–1298. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1290-1298.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knutton S, Rosenshine I, Pallen M J, Nisan I, Neves B C, Bain C, et al. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:2166–2176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kresse A U, Rohde M, Guzman C A. The EspD protein of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli is required for the formation of bacterial surface appendages and is incorporated in the cytoplasmic membranes of target cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4834–4842. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4834-4842.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucht J M, Dersch P, Kempf B, Bremer R. Interactions of the nucleoid-associated DNA binding protein H-NS with the regulatory region of the osmotically controlled proU operon of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6578–6586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDaniel T K, Kaper J B. A cloned pathogenicity island from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli confers the attaching and effacing phenotype on E. coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:399–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2311591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKee M L, Melton-Celsa A R, Moxley R A, Francis D H, O'Brien A D. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 requires intimin to colonize the gnotobiotic pig intestine and to adhere to HEp-2 cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3739–3744. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3739-3744.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mellies J L, Elliott S J, Sperandio V, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. The Per regulon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: identification of a regulatory cascade and a novel transcriptional activator, the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator (Ler) Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:296–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paton A W, Manning P A, Woodrow M C, Paton J C. Translocated intimin receptors (Tir) of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli isolates belonging to serogroups O26, O111, and O157 react with sera from patients with hemolytic-uremic syndrome and exhibit marked sequence heterogeneity. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5580–5586. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5580-5586.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paton A W, Ratcliff R, Doyle R M, Seymour-Murray J, Davos D, Lanser J A, Paton J C. Molecular microbiological investigation of an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome caused by dry fermented sausage contaminated with Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1622–1627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1622-1627.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paton A W, Voss E, Manning P A, Paton J C. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from cases of human disease show enhanced adherence to intestinal epithelial (Henle 407) cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3799–3805. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3799-3805.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paton A W, Woodrow M C, Doyle R M, Lanser J A, Paton J C. Molecular characterization of a Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli O113:H21 strain lacking eae responsible for a cluster of cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3357–3361. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3357-3361.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paton J C, Paton A W. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:450–479. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perna N T, Mayhew G F, Posfai G, Elliott S, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Blattner F R. Molecular evolution of a pathogenicity island from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3810–3817. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3810-3817.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riley L W, Remis R S, Helgerson S D, McGee H B, Wells J G, Davis B R, Hebert R J, Olcott E S, Johnson L M, Hargrett N T, Blake P A, Cohen M L. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:681–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303243081203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rimsky S, Spassky A. Sequence determinants for H1 binding on Escherichia coli lac and gal promoters. Biochemistry. 1990;29:3765–3771. doi: 10.1021/bi00467a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shindo H, Iwaki T, Ieda R, Kurumizaka H, Ueguchi C, Mizuno T, Morikawa S, Nakamura H, Kuboniwa H. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of a nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS, from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00079-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor K A, O'Connell C B, Luther P W, Donnenberg M S. The EspB protein of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is targeted to the cytoplasm of infected HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5501–5507. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5501-5507.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobe T, Schoolnik G K, Sohel I, Bustamante V H, Puente J L. Cloning and characterization of bfpTVW, genes required for the transcriptional activation of bfpA in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:963–975. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.531415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tobe T, Yoshikawa M, Mizuno T, Sasakawa C. Transcriptional control of the invasion regulatory gene virB of Shigella flexneri: activation by VirF and repression by H-NS. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6142–6149. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6142-6149.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ueguchi C, Mizuno T. The Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS functions directly as a transcriptional repressor. EMBO J. 1993;12:1039–1046. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ueguchi C, Seto C, Suzuki T, Mizuno T. Clarification of the oligomerization domain and its functional significance for the Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:145–151. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voss E, Paton A W, Manning P A, Paton J C. Molecular analysis of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli O111:H− proteins which react with sera from patients with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1467–1472. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1467-1472.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wieler L H, Vieler E, Erpenstein C, Schlapp T, Steinruck H, Bauerfeind R, Byomi A, Baljer G. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from bovines: association of adhesion with carriage of eae and other genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2980–2984. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.2980-2984.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams R M, Rimsky S, Buc H. Probing the structure, function, and interactions of the Escherichia coli H-NS and StpA proteins using dominant negative derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4335–4343. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4335-4343.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamada H, Yoshida T, Tanaka K-I, Sasakawa C, Mizuno T. Molecular analysis of the Escherichia coli hns gene encoding a DNA-binding protein, which preferentially recognizes curved DNA sequences. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;230:332–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00290685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang A, Belfort M. Nucleotide sequence of a newly-identified Escherichia coli gene, stpA, encoding an H-NS-like protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6735. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.24.6735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]