Abstract

A murine model that closely resembles human cerebral malaria is presented, in which characteristic features of parasite sequestration and inflammation in the brain are clearly demonstrable. “Young” (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice infected with Plasmodium berghei (ANKA) developed typical neurological symptoms 7 to 8 days later and then died, although their parasitemias were below 20%. Older animals were less susceptible. Immunohistopathology and ultrastructure demonstrated that neurological symptoms were associated with sequestration of both parasitized erythrocytes and leukocytes and with clogging and rupture of vessels in both cerebral and cerebellar regions. Increases in tumor necrosis factor alpha and CD54 expression were also present. Similar phenomena were absent or substantially reduced in older infected but asymptomatic animals. These findings suggest that this murine model is suitable both for determining precise pathogenetic features of the cerebral form of the disease and for evaluating circumventive interventions.

Human cerebral malaria (CM) is a serious neurological condition that can lead to coma and death. Its principal feature is endothelial damage associated with the sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum schizonts within the microvasculature of the brain (24). However, studying CM in humans is difficult because of the inability to correlate pathological changes precisely with the clinical features. This is an important prerequisite in the treatment of CM. Therefore, there is an obvious need for experimental models that bear close similarity to human CM in order to understand the precise mechanisms leading to coma and death and for the development of therapeutic regimens. The phenomenon has been extensively studied in experimental animals in order to find a system that closely resembles CM in humans. Primate models, particularly that of Plasmodium coatneyi infections in rhesus monkeys (21), have given encouraging results but are limited by practical and financial constraints. Murine models are more suitable for experimental studies, but thus far it has always been suggested that the findings do not resemble those seen during human CM exactly. In both human and mouse, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF)-induced upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules has been invoked as a factor in pathology involving the sequestration of cells within the microvasculature of the brain and other major organs of the body (15, 16). However, other studies have suggested that there are differences between the two species, with a preference for leukocyte sequestration in the mouse (14) rather than for parasitized red blood cell sequestration, as seen in humans (1).

In our previous studies on the role of cytokines during various blood-stage malaria infections (12), we observed that Plasmodium berghei ANKA infections in “young” 8-week-old (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice frequently resulted in neurological symptoms and early death (de Souza et al., unpublished observations). These characteristic CM-associated symptoms were less common in “older” (15 to 20 weeks) animals. These observations have now been extended further and show that this model of murine malaria does indeed bear a strong resemblance to human CM, including the characteristic feature of parasite sequestration within the microvasculature of the brain. Furthermore, the associated immunopathological changes (e.g., rupture of blood vessels, hemorrhage, and edema) add further evidence to suggest that the pathogenesis of CM is not merely due to mechanical microvascular obstruction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

(BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice were bred at Biological Services, Royal Free and University College London Medical School, from parental stocks obtained from the National Institute for Medical Research, Mill Hill, London, United Kingdom. Mice of both sexes were used at various ages between 8 and 20 weeks.

Parasite infection and follow-up.

P. berghei ANKA parasites (from N. Wedderburn, Royal College of Surgeons, London, United Kingdom) from liquid nitrogen stocks were subjected to at least one in vivo passage prior to use in experimental infection. Mice of different ages were infected intravenously (i.v.) with 104 parasitized red blood cells. Parasitemias were estimated on Giemsa-stained blood films from day 3 onwards, and the animals' states of health were closely monitored for neurological symptoms.

Production of P. berghei-specific antiserum for immunohistochemistry.

Fifteen mice 8 to 10 weeks old were vaccinated subcutaneously twice with 25 μg of P. berghei semipurified antigen plus Provax (kindly provided by IDEC Pharmaceuticals) as adjuvant 2 weeks apart, as described previously for Plasmodium yoelii antigens (11). Three weeks later, these animals and five unvaccinated controls were challenged i.v. with 104 parasitized red blood cells, and their parasitemias were monitored from day 5 onwards. Parasitemias of both vaccinated and unvaccinated groups were patent on day 5. Four control mice died on day 9, and one died on day 20. While 9 of 15 of the vaccinated group failed to control their infection and died (3 on day 10 and 6 on day 17), 6 animals resolved their parasitemia and recovered on day 21. These animals were bled 3 days later for immune serum, which was absorbed with normal mouse liver and red blood cells, filtered (0.45-μm pore size; Millipore), aliquoted, and stored at −20°C.

Brain sections for histology and immunohistopathology.

CM-positive (CM+) mice displaying neurological symptoms were sacrificed, usually between days 6 and 8 after infection, and their brains were removed carefully, examined, and stored in liquid nitrogen prior to sectioning for immunohistopathological analysis. Uninfected normal control and CM-negative (CM−) mice were sacrificed at the same time. Animals were killed by mild terminal anesthesia to prevent accidental damage caused by cervical dislocation. Routine frozen histological sections 7-μm thick were prepared on glass slides, fixed in acetone, air dried, and stored for 1 to 2 days at −20°C to enable tissue adherence to the slides.

(i) Detection of parasites.

Parasites were detected on brain sections with either Giemsa stain or a specific anti-P. berghei ANKA antibody. Sections for Giemsa stain were fixed in methanol and treated identically as for blood films.

A modified indirect immunofluorescence technique similar to the slide fluorescence assay described for determining antiparasite antibody titers on schizont-coated slides (10) was adapted for confirming the presence of parasites in the brain. Sections were incubated at room temperature first in a 1:200 dilution of immune serum for 1 h. After three washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–0.2% bovine serum albumin–0.5% Tween, sections were incubated in a 1:100 dilution of a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig; Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) containing Evan's blue for 45 min. After three washes, sections were mounted and examined under UV incident light microscopy. Brightly fluorescing parasites were observed against a red background (due to the Evan's blue), which enabled the identification of brain tissue and other cells. Normal mouse serum or PBS was used as a control.

(ii) Detection of pathological markers.

The presence of two pathological markers, ICAM-1/CD54 and TNF, was investigated using a standard indirect immunocytochemical technique. Primary monoclonal rat anti-mouse ICAM-1/CD54, 10 ng/ml (KAT-1 clone; Southern Biotechnology Associates), or hamster anti-mouse TNF, 15 μg/ml (Pharmingen), were used with a rabbit anti-rat IgG biotinylated secondary antibody, 1:100 (Dako). Binding was detected with a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate, 1:100 (Pharmingen), and 3,3-diaminobenzidine, 1 mg/ml (Sigma), as a substrate. Nuclei were visualized with hematoxylin stain.

(iii) Ultrastructural studies.

For ultrastructural studies, animals from both the uninfected control and CM+ groups were sacrificed as above, but immediately after opening, the cranial cavity of the brain was flooded with chilled 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The whole brains were then fixed by immersion in the same fixative solution at 4°C. The cerebra and cerebella were cut into 1.5-mm coronal and sagittal slices, respectively, and then fixed for a further 2 h in the same solution; subsequently, and after a brief wash in buffer, for 1 h in 1% aqueous osmium tetroxide. The slices were then dehydrated through graded ethanol solutions and embedded in Agar 100 epoxy resin. Thin sections cut from these blocks were stained with aqueous lead citrate and methanolic uranyl acetate and examined in a Jeol 1200ex electron microscope at 80 kV.

Statistics.

Significance levels were determined by Student's t test for unpaired observations.

RESULTS

Characterization of P. berghei infections in (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice.

Animals that were developing CM were usually identifiable as ill, as judged by coat ruffling and general immobility 24 h prior to developing full CM symptoms and death. After 24 h, the symptoms progressed rapidly (within 2 to 3 h) in clearly defined stages, beginning with partial paralysis, fitting and hyperventilation, coma, and death. Parasitemias at this stage were between 10 and 20% (Fig. 1), with few schizonts detectable on blood films. These diagnostic criteria were consistent with the development of CM, always appearing 6 to 8 days after infection. Age-matched CM− animals had similar parasitemias, but significantly more schizonts were seen on their blood films. These CM− animals do not display the above symptoms but usually progress to severe malaria 7 to 10 days later, with hyperparasitemia, dehydration weight loss, and death due to severe anemia, as judged by grossly reduced red blood cell density on Giemsa-stained blood films.

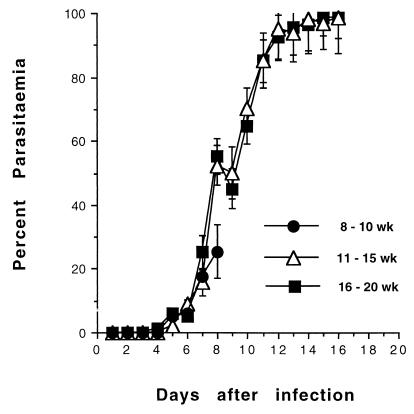

FIG. 1.

Course of P. berghei ANKA infection in (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice. Groups of mice of different ages were injected i.v. with 104 parasitized erythrocytes. Parasitemias from Giemsa-stained tail blood films were monitored from day 3 onwards. Representative parasitemias ± standard error (SE) from groups of 18 to 30 mice from five separate experiments are shown.

Neurological symptoms followed by death were more frequent among younger animals (Table 1). Thus, 8- to 10-week-old mice weighing 18 to 20 g were highly susceptible to CM, with a mortality rate of 98% after 6 to 8 days of infection, although their parasitemias were low. Mice aged 11 to 14 weeks and weighing 25 to 30 g were relatively resistant, with only 32% dying between days 7 and 10. Some of the older animals who did not encounter early death appeared to display CM reversal; they were ill on day 6 but seemed to have reversed their symptoms at 24 h and survived. Mice with these features are known to die later of severe anemia and hyperparasitemia but without CM (25). Mice aged 15 or more weeks and weighing in excess of 35 g were least affected, with 17% succumbing to CM. Some of these animals also displayed CM reversal.

TABLE 1.

Features of PbA infection in (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice of different agesa

| Age (wk) | Mean body wt (g) ± SD | % CM+ (no. positive/total) | Mean day of death ± SD | No. of mice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8–10 | 20.5 ± 8.5 | 98.0 (39/40) | 8.0 ± 1.6 | 40 |

| 11–15 | 29.2 ± 6.5 | 31.8 (7/22) | 10.2 ± 3.7 | 22 |

| 16–20 | 35.5 ± 3.8 | 16.7 (3/18) | 20.0 ± 3.5 | 18 |

Animals were weighed prior to infection with 104 PbA-infected erythrocytes as described in the text. Data are pooled from five separate experiments showing the mean ± SD body weight and day of death. Values in parentheses show actual numbers of animals that developed CM among the total number in each age group; these CM+ animals invariably progress through the stages of paralysis, fitting, and coma.

Gross examination of CM brain.

CM+ animals were sacrificed at the fitting or coma stages described above. Examination of the cranium revealed hemorrhaging under the meninges, along a central area extending from the tip of the cerebral hemisphere down to the cerebellum and medulla oblongata. The latter signs were absent in brains of infected but CM− and normal uninfected animals. Macroscopic signs of edema were obvious, as judged by increased volume and meningeal tension in brains removed from CM+ animals compared with normals, but were also seen in the infected CM− animals.

Immunohistopathology.

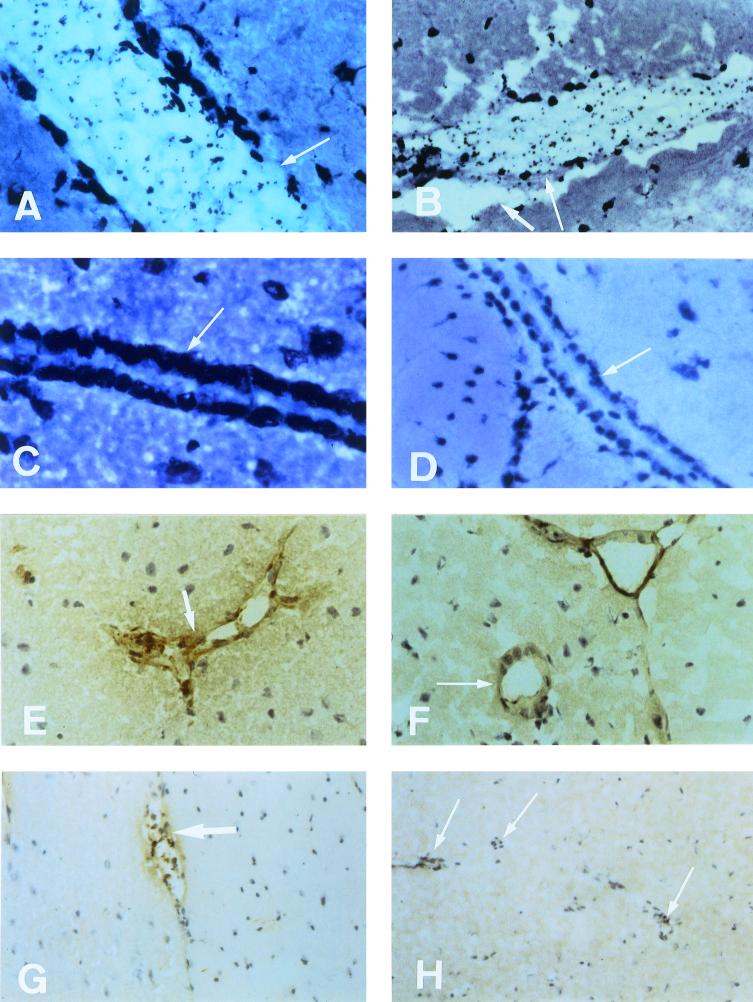

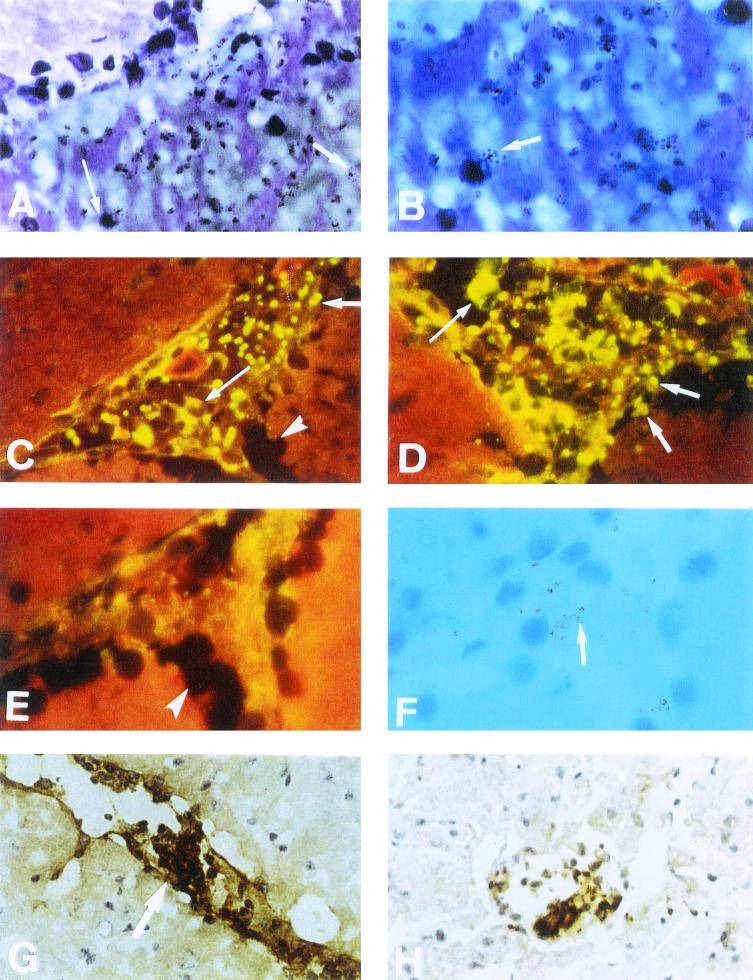

Sagittal sections from the midline region of brains taken from CM+, CM−, and control uninfected mice were stained and examined. Sections were carefully scanned over the entire area, including the cerebrum, cerebellum, corpora, and ventricular system. Intact blood vessels with well-defined endothelial lining were always seen on normal uninfected and CM− brain sections (Fig. 2C to H). In CM+ brain, the vessels with intact endothelia were more difficult to detect (Fig. 2A and B, Fig. 3A to H), due to their generally distended nature, with the lumen packed with adhering parasites and leukocytes and with areas of rupture and hemorrhage. Parasites were detected by Giemsa staining or by immunofluorescence with a P. berghei-specific antiserum. Standard immunohistochemistry was used to confirm the known presence of ICAM-1/CD54 and TNF.

FIG. 2.

Evidence of parasite and leukocyte sequestration in the microvasculature of the brain during experimental murine CM. Representative immunohistopathology of sagittal sections of the cerebrum taken from normal uninfected, CM−, and CM+ animals on the same day after infection. (A and B) Giemsa stain analysis of longitudinal sections of vessels from a CM+ animal taken at the coma stage, showing vascular distension, parasites and leukocytes in the lumen and sequestered (B, long arrow), endothelial damage (A, long arrow), and signs of edema (B, short arrow). (C and D) Giemsa stain analysis of longitudinal sections of vessels from a CM− (C, no parasites visible) and an uninfected normal (D) animal. Arrows show intact endothelium and no vascular distension. (E and F) ICAM-1 staining of vessels from CM− (E) and normal (F) animals. Arrows indicate positive staining within intact endothelia, and no visible parasites in the CM− sample (E). (G and H) TNF staining of vessels from CM− (G) and normal (H) animals. Short arrow shows weak staining and few mononuclear cells in the CM− sample (G); long arrows show various negatively stained vessels in the normal brain sample (H). All panels: magnification, ×40.

FIG. 3.

Evidence of parasite and leukocyte sequestration in the microvasculature of the brain during experimental murine CM. Representative immunohistopathology of sagittal sections of the cerebrum taken from an animal sacrificed at the coma stage. (A) Giemsa stain showing damaged endothelium with schizont (short arrow) and mononuclear cell (long arrow) discharge into the cerebrum. (B) High-power view of hemorrhage site in A showing schizonts (short arrow). (C and D) Cross-section of a plugged blood vessel, near the corpus callosum, showing sequestration of FITC-stained schizonts (short arrow) within the endothelium. Lesion also includes mononuclear cells with attached fluorescing parasites (long arrow). Arrowhead shows cerebral edema. (E) Lack of parasite-specific staining on section stained with control normal mouse serum. Only background fluorescence visible. Arrowhead shows cerebral edema. (F) Transmitted-light view of panel E, showing location of parasites, some attached to mononuclear cells (short arrow). (G) Positive ICAM-1 staining of longitudinal section of a blood vessel. Arrow indicates sequestration and vascular plug containing monocytes and parasites. (H) Positive TNF staining of transverse section of blood vessel, showing damaged endothelium, sequestration of monocytes, and parasites. Arrow shows leakage of parasites from damaged endothelium. Magnifications: A, C, E, F, G, and H, ×40; B and D, ×100.

(i) Detection of parasites by Giemsa staining.

It was of interest to document Giemsa analysis on brain sections, as this has not been reported previously for murine CM. In general, parasites were not seen in CM− brain sections, including those from animals (from all age groups) that recovered from their CM symptoms, and there was no evidence of vascular distension compared with normal uninfected brain (Fig. 2C and D). However, phagocytic cells with engulfed malarial pigment were visible in vessels of the ventricular system of CM− animals (data not shown); CM+ brain sections showed parasites and leukocytes within blood vessels (Fig. 2A and B) and in hemorrhages detected under low-power microscopy (Fig. 3A). In general, petechial and large hemorrhages containing parasites were always identifiable in distinctive turquoise-colored areas (Fig. 3A and B). Schizonts were clearly seen as typical “bunches of grapes” at higher magnification (Fig. 3B), and they were similar in structure to schizonts normally seen on Giemsa-stained blood films. Unruptured blood vessels within CM+ brains were distended and packed with leukocytes. Some contained engulfed parasites as well as free parasitized erythrocytes in close contact with the endothelium (Fig. 2A and B). Small nonnucleated fragments, probably platelets, were also seen in plugged vessels, and fine granules possibly released by platelets were present in aggregates with leukocytes and parasites (data not shown). Sequestration was evident in both cerebral and cerebellar vessels in CM+ sections.

(ii) Detection of parasites by immunofluorescence.

In addition to Giemsa analysis, an indirect immunofluorescence assay using a specific anti-P. berghei immune serum was used to detect parasites in brain sections. Weak fluorescence was only seen on isolated endothelial cells, not on parasites, on CM brain sections treated with normal mouse serum (Fig. 3E and F) or PBS (data not shown). Furthermore, the anti-P. berghei-specific antiserum did not react with vasculature of normal brain tissue, and besides weak background fluorescence, parasites were not detectable in CM− brain sections (data not shown). The immune serum, of antibody titer 1:16,384 when tested on schizont-coated slides, reacted strongly with parasites on CM+ brain sections when used at a dilution of 1:512 to 1:1,024. Bright fluorescent sequestering and nonsequestering forms of parasite were visible on a red (Evan's blue) background within vascular endothelia of both the cerebrum (Fig. 3C and D) and the cerebellum (data not shown). Additionally, rosette-like structures were seen adhering to the endothelium or existing freely within the vasculature, and this was evident by both transmitted light (Fig. 3F) and fluorescence (Fig. 3C and D) microscopy. These rosettes comprised parasitized red blood cells bound to monocytes. This technique was more sensitive in identifying parasite sequestration phenomena and hemorrhages than Giemsa staining. Thus, it is clear that sequestration of parasites along with leukocytes does occur within the vasculature of the brain during experimental CM in (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice. Similar studies of CM+ brains from C57BL/6 mice did not reveal the above findings (de Souza et al., unpublished).

(iii) TNF and ICAM-1/CD54 expression during CM.

Upregulation of mediators of pathology during CM has been reported previously in both murine (19) and human (33) malaria. Hence, it was important to document these phenomena in this model. Both quantitative and qualitative analyses were carried out. The number of positively stained vessels was estimated from six representative microscope fields (magnification, ×20) per section, from a total of at least six sections per brain sample; brains from three different CM+, CM−, or normal uninfected animals were analyzed. Data were pooled and expressed as the mean percentage ± standard deviation (SD) of positively stained vessels pertaining to the total number of vessels per microscope field analyzed. With respect to ICAM-1, in the postcapillary venules and in the larger-caliber vessels from normal brain, the endothelium was weakly positive in 44% ± 2.1% of the vessels examined but was otherwise intact (Fig. 2F). Relatively weak staining was also seen in 87% ± 2.0% (P < 0.002 compared with normal brain) of vessels in CM− sections, and there was no evidence of endothelial damage (Fig. 2E). However, in CM+ brain sections, strong ICAM-1 staining was seen in 98% ± 1.2% (P < 0.03 and P < 0.0001 compared with CM− and normal brain, respectively) of capillaries and postcapillary venules. The lumens of many of these were occluded with sequestered and nonsequestered leukocytes and parasites, and there were clear signs of endothelial damage (Fig. 3G).

Only 10% ± 0.5% of the vessels in normal brain sections were weakly positive for endothelial TNF expression (Fig. 2H), representing baseline levels of TNF production. Weakly positive staining was also seen in 12.5% ± 0.7% (P < 0.007 compared with normal brain) of vessels in CM− sections, and there was no evidence of endothelial damage (Fig. 2G). Strong positive staining for TNF was detected on leukocytes and parasites and on small granular nonnucleated bodies which were not parasites in 50% ± 4.3% (P < 0.0001 compared with CM− and normal brain) of cerebral and cerebellar vessels displaying endothelial damage in CM+ brain sections (Fig. 3H).

(iv) Ultrastructural studies.

The presence of parasitized erythrocytes and monocytes in both cerebral and cerebellar blood vessels was confirmed by electron microscopy. Here we show the fine structure of the cerebellum from uninfected control and infected mice. Similar changes were seen in the cerebrum (data not shown).

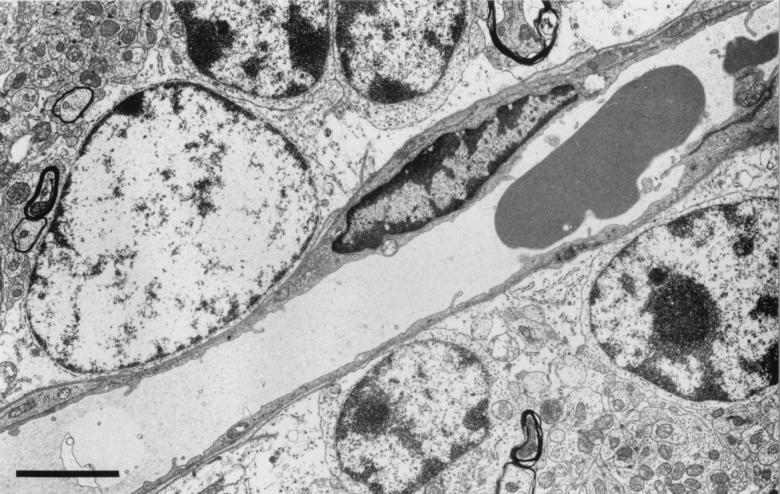

In normal control cerebella, the endothelial cells showed no evidence of activation and the erythrocytes were not in contact with the endothelium (Fig. 4). There was some evidence of anoxic change attributable to the need to fix the brain by surface application in situ prior to its removal. In addition, there were some dark shrunken Purkinje cells and distended glial and neuronal mitochondria, but the tissue was generally well preserved, there were no hemorrhages, and there was little swelling of the perivascular astrocytic endfeet. Few red cells were visible within the parenchymal capillaries.

FIG. 4.

Fine structure of a capillary in the granule cell layer of the cerebellum from a control uninfected animal. Bar, 3 μm.

A number of consistent pathological features were seen within the cerebella of infected CM+ mice displaying early neurological symptoms. Many penetrating vessels and parenchymal capillaries were congested with red cells, some of which showed reduced density indicative of partial lysis and contained parasites (Fig. 5A). Some vessels contained activated monocytes with numerous protrusions along the cell membrane and increased cytoplasmic vacuolation (Fig. 5B). The capillaries themselves showed occasional free parasites (Fig. 5A), and there was disruption of the endothelial wall (Fig. 6B) and proliferation of the luminal aspect of the endothelial cells (Fig. 6C). Residual plasma within the capillaries generally showed an increased electron density with some evidence of flocculation (Fig. 6D and E), and the perivascular astrocytic endfeet were considerably swollen (Fig. 5A, 5B, and 6E). Hemorrhages into the surrounding tissue were present around both penetrating vessels and parenchymal capillaries, and these also included partially lysed red cells containing parasites (Fig. 6F).

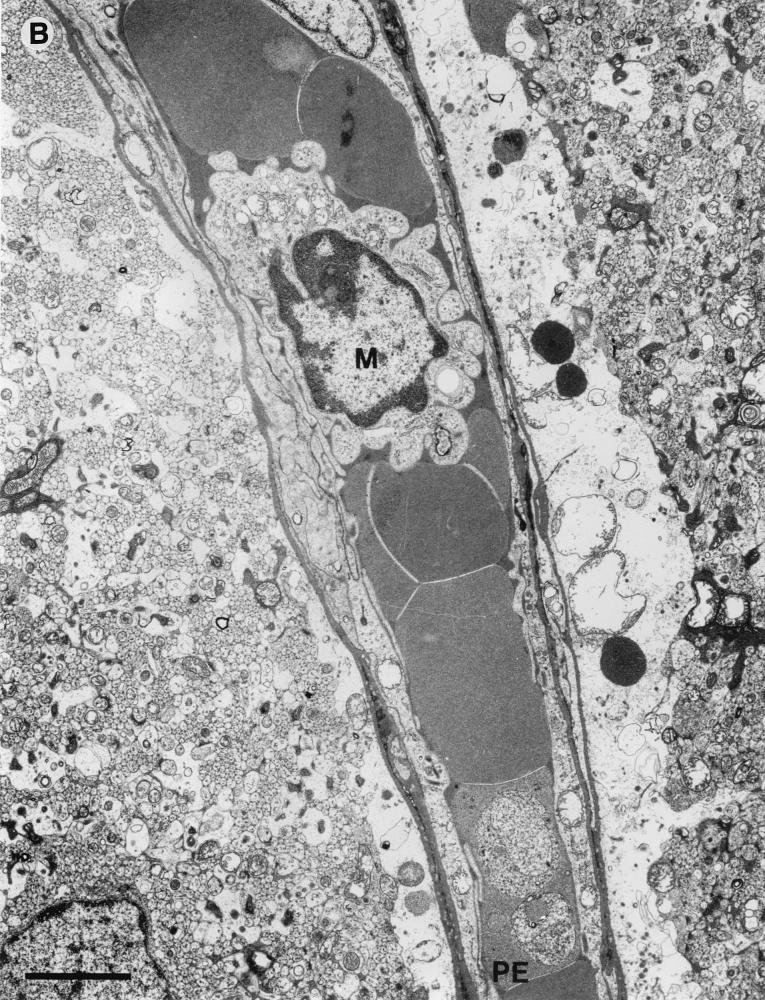

FIG. 5.

Fine structure of postcapillary venules from the brain of a CM+ animal displaying neurological symptoms. (A) Venule from the cerebellum occluded by erythrocytes, one partially lysed and containing a parasite (PE). Bar, 3 μm. (B) Capillary from the cerebellum occluded by erythrocytes, one containing parasites (PE), and an activated monocyte (M) (note membrane protrusions and cytoplasmic vacuolation). Bar, 3 μm.

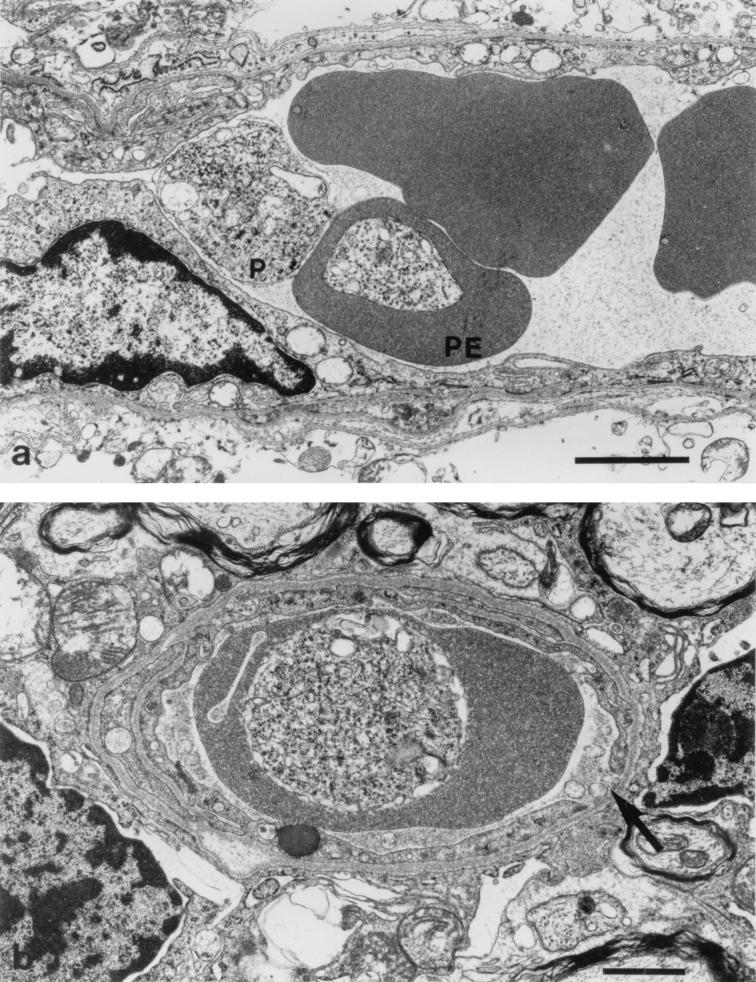

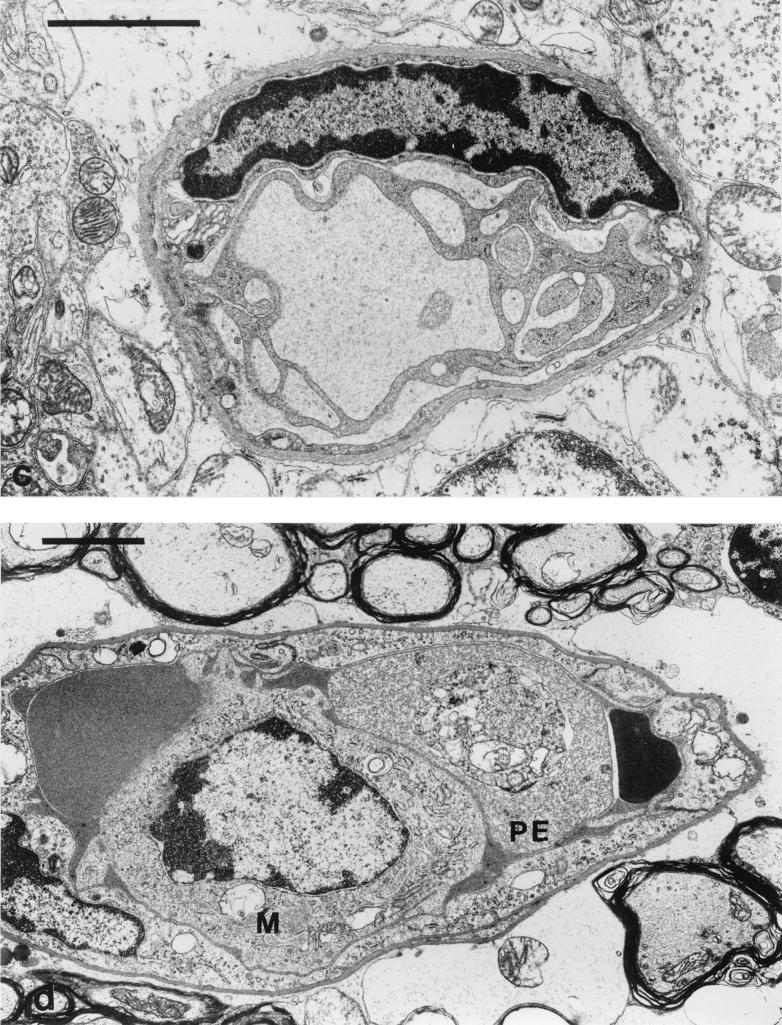

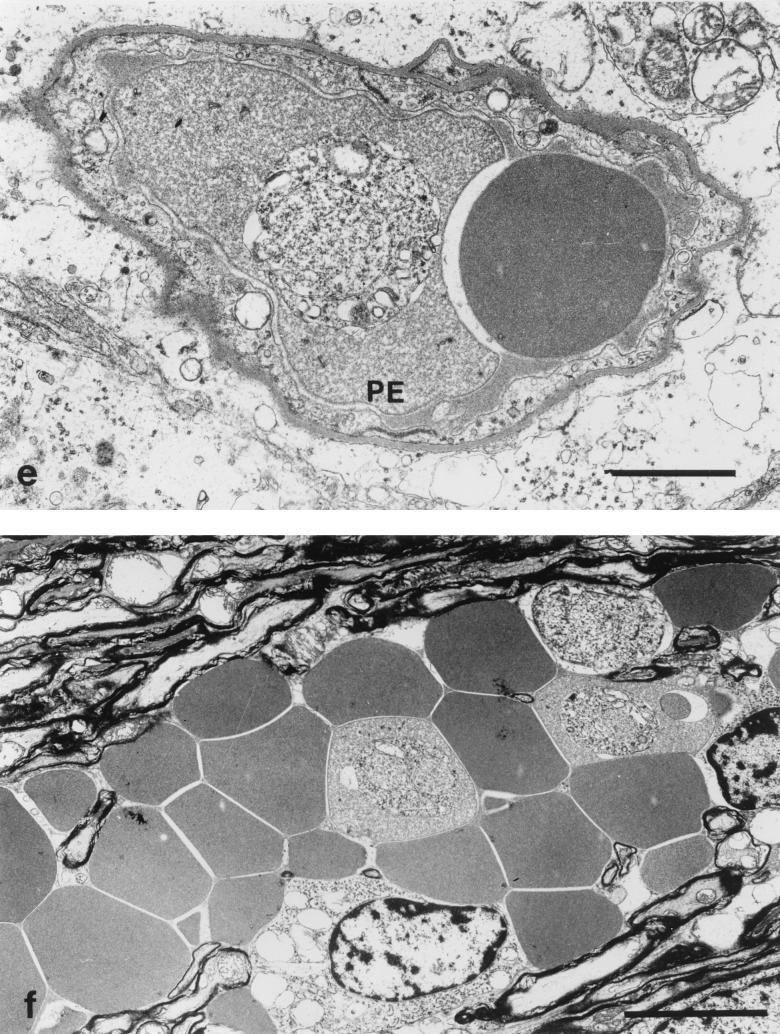

FIG. 6.

Ultrastructural detail of microvascular changes in the brain leading to endothelial damage and hemorrhage during murine CM. (a) Capillary containing erythrocytes, one parasitized (PE), and with one parasite (P) free within the lumen. Bar, 2 μm. (b) Capillary from the cerebellar parenchyma largely occluded by a partially lysed parasitized erythrocyte. Note the break in the endothelial cell lining (arrow). Bar, 1 μm. (c) Capillary in the granule cell layer showing extensive proliferation of the endothelial luminal surface. Bar, 2 μm. (d) Capillary from the cerebellar parenchyma occluded by a monocyte (M) and erythrocytes, one containing a parasite (PE). Bar, 2 μm. (e) Cerebellar capillary largely occluded by erythrocytes, one containing a parasite (PE). Bar, 2 μm. (f) Hemorrhage into the cerebellar parenchyma, with parasites visible within three partially lysed erythrocytes. Bar, 5 μm.

These appearances are interpreted to indicate the existence of extensive hemostasis, with endothelial cell disruption or necrosis leading to hemorrhage, escape of parasitized red cells into the cerebellar parenchyma, and perivascular astrocytic edema with some evidence of endothelial cell activation.

DISCUSSION

Several important observations have been made in these studies. First, this is the first time that a murine CM model has been defined in which parasitized erythrocytes appear in close contact with the microvascular endothelium of the brain, resembling the pattern seen in humans. Second, this model of P. berghei infection using an F1 mouse derived from two strains which have different susceptibility patterns is characterized not only by an age-dependent susceptibility to CM but also by a reversal of CM symptoms, as can occur in humans. Third, the high expression of TNF and ICAM-1 associated with microvascular lesions of CM+ brain, and the associated vascular injury, leakage, and rupture, together with sequestration, confirmed at the electron microscopic level, suggest that our experimental model resembles human CM much more closely than any previous models have done.

To date, experimental murine CM has been extensively studied in resistant (BALB/c) versus susceptible (CBA, C57BL, and A/J) strains of mice (9). We have shown that susceptible and resistant traits coexist in (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice, and we have observed (data not shown) that reversal of symptoms occurs in some older animals. The age-related susceptibility of these mice to CM cannot be explained in immunological terms but requires further investigation. Nevertheless, there are two interesting findings in this strain of mouse. First, mortality due to CM is restricted to younger animals, which would represent a small fraction if the study were based on equal numbers of animals of specified ages. Second, an interesting feature of our model is the reversal of CM in older animals. Both of these features are also found in human P. falciparum malaria (26). In the one strain where resolution has been found before, DBA/2J, the underlying mechanism of CM resolution appears to be related to a vastly reduced degree of monocyte accumulation in the microvasculature of the major organs of the body, including the brain (27).

Previous studies which examined the immunopathology of the brain during murine CM have not shown convincing parasite sequestration (27, 31). Studies using retinal wholemounts instead of brain sections substantiate the view of leukocyte sequestration, but parasites were not seen in the sections (5). Other studies of parasite levels in the brain are either indirect, as judged by mRNA levels (18), or demonstrable apparently in the absence of inflammation (discussed below) and hemorrhage, as seen during the lethal P. yoelii 17XL infection (20). This lack of clear-cut demonstration of parasite sequestration and associated pathology has led to the negative views about murine models for studying the immunopathology of human CM. Our immunofluorescence observations, showing venules plugged with parasites, suggesting that sequestration does occur in (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice, are therefore extremely important. These studies have been further substantiated by ultrastructural analyses, which have confirmed the occurrence of hemostasis and close contact between parasitized erythrocytes, activated leukocytes, and the endothelium. Furthermore, the ultrastructure also shows associated “activation” of endothelium, implying some degree of endothelial injury.

Leukocytes were also present in CM brain lesions of our animals, and we are currently investigating the precise phenotypic characteristics of these cells. Inflammatory changes involving CD4+ T cells (15) are thought to be a characteristic of murine models, but they have also been implicated in human CM (30), with cytokine involvement (3, 22). In addition, there is convincing evidence that links increases in macrophages and microglial cells in human CM brain parenchyma with inflammation and granuloma formation (8). Nonnucleated cells resembling platelets, clumped together with leukocytes, were also detected in our CM lesions. Platelets are thought to play a vital role in CM-related vascular injury, where they appear to fuse with TNF-activated endothelium and enhance the adhesion of leukocytes via LFA-1 interactions (16, 23). Work is currently in progress to clarify the precise role of platelets in the immunopathology seen in our model (collaboration with G. Grau).

Overproduction of inflammatory cytokines TNF, interleukin-1, and gamma interferon upregulate a number of adhesion molecules, including ICAM-1/CD54 (17), CD36, and thrombospondin (28) on vascular endothelia of the major organs of the body, including the brain. These molecules are involved in the pathogenesis of both human and experimental CM. High expression of TNF and ICAM-1 in our CM+ brain sections was seen not just in vascular endothelial cells but also on leukocytes and parasites in CM+ lesions. This provides further supportive evidence that both parasitized erythrocytes and leukocytes contribute to the microvascular lesion during murine CM as well as in humans.

High expression of host adhesion molecules, in particular ICAM-1 (19, 28), on activated vascular endothelia enhances the binding of infected red blood cells. This occurs via receptors on the parasitized red blood cell surface and leads to sequestration phenomena that are typical of cerebral malaria (1). The receptor has been identified on P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes as the large membrane protein PfEMP1 (29), and therefore it should now also be possible to identify the receptor on P. berghei-infected erythrocytes in our murine model. In addition, it has been suggested that rosette formation (32) (between infected and uninfected erythrocytes) and cytoadherence of rosettes to the endothelium via CD36 or CD31 (13) may be contributory factors in human CM. However, rosette formation has not been demonstrated in P. berghei-infected mice, and the phenomenon was not clearly seen in this study. Some rosette-like structures seen fluorescing in the CM+ sections may indicate early stages of phagocytosis. Plugging of the microvasculature by the latter type of structures may have contributed to the clinical symptoms of our CM+ animals, since they were absent in cerebral vessels of our CM− animals. However, this is undoubtedly not the only event, since increased local production of TNF may be the likely cause of parasitized erythrocyte sequestration in the microvasculature and endothelial injury occurring at the same time with leakage of parasites into the environment of the brain, contributing clinically to fitting and coma. These studies support the microvascular hypothesis of CM (2, 30) rather than the nitric oxide theory (4, 7), but it is also possible that the role of nitric oxide itself is mediated at the endothelial level. It has recently been suggested that sequestration, through localized hypoxia, might contribute to endothelial injury by enhancing cytokine-induced inducible nitric oxide synthase (6). Hence, the combination of sequestration and plugging plus endothelial damage leads to rupture as a priming event rather than infarction.

In conclusion, therefore, this study has shown that our murine CM model of P. berghei ANKA infection in (BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1 mice has several features in common with human CM and may be useful in future work unraveling the underlying features of the disease. A detailed understanding of the association between parasite sequestration, endothelial injury, vessel rupture, and cerebral symptoms will greatly assist in the development of effective chemotherapeutic interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust, the British Heart Foundation, and a UCL discretionary grant.

J. Hearn was supported by a grant from the foundation established by the late Jean Shanks.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aikawa M, Iseki M, Barnwell J W, Taylor D, Oo M M, Howard R J. The pathology of human cerebral malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43:30–37. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berendt A R, Turner G D H, Newbold C I. Cerebral malaria: the sequestration hypothesis. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:412–414. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown H, Turner G, Rogerson S, Tembo M, Mwenechanya J, Molyneux M, Taylor T. Cytokine expression in the brain in human cerebral malaria. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1742–1746. doi: 10.1086/315078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgner D, Xu W, Rockett K, Gravenor M, Charles I G, Hill A V, Kwiatkowski D. Inducible nitric oxide synthase polymorphism and fatal cerebral malaria. Lancet. 1998;352:1193–1194. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60531-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan-Ling T, Neill A L, Hunt N H. Early microvascular changes in murine cerebral malaria detected in retinal wholemounts. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:1121–1130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark I A, Cowden W B. Why is the pathology of falciparum worse than that of vivax malaria? Parasitol Today. 1999;15:458–461. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark I A, Rockett K. The cytokine theory of human cerebral malaria. Parasitol Today. 1994;10:410–412. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deininger M H, Kremsner P G, Meyermann R, Schluesener H J. Focal accumulation of cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and COX-2 expressing cells in cerebral malaria. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;106:198–205. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Kossodo S, Grau G E. Profiles of cytokine production in relation with susceptibility to cerebral malaria. J Immunol. 1993;151:4811–4820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Souza J B, Ling I T, Ogun S, Holder A A, Playfair J H L. Cytokines and antibody subclass associated with protective immunity against blood-stage malaria in mice vaccinated with the C terminus of MSP-1 plus a novel adjuvant. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3532–3536. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3532-3536.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Souza J B, Playfair J H L. A novel adjuvant for use with a blood-stage malaria vaccine. Vaccine. 1995;13:1316–1319. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00025-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Souza J B, Williamson K E, Otani T, Playfair J H L. Early gamma interferon responses in lethal and nonlethal murine blood-stage malaria. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1593–1598. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1593-1598.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez V, Treutiger C J, Nash G B, Wahlgren M. Multiple adhesive phenotypes linked to rosetting binding of erythrocytes in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2969–2975. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2969-2975.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grau G E, Bieler G, Pointaire P, De Kossodo S, Tacchini-Cotier F, Vassalli P, Piguet P F, Lambert P-H. Significance of cytokine production and adhesion molecules in malarial immunopathology. Immunol Lett. 1990;25:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(90)90113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grau G E, Fajardo L F, Piguet P F, Allet B, Lambert P-H, Vassalli P. Tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) as an essential mediator in murine cerebral malaria. Science. 1987;237:1210–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.3306918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grau G E, Tacchini-Cottier F, Vesin C, Milon G, Lou J, Piguet P F, Juillard P. TNF-induced microvascular pathology: active role for platelets and importance of the LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1993;4:415–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hviid L, Theander T G, Elhassan I M, Jensen J B. Increased plasma levels of soluble ICAM-1 and ELAM-1 (E-selectin) during acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Immunol Lett. 1993;36:51–58. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(93)90068-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennings V M, Actor J K, Lal A A, Hunter R L. Cytokine profile suggesting that murine cerebral malaria is an encephalitis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4883–4887. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4883-4887.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaul D, Liu X D, Nagel R L, Shear H L. Microvascular hemodynamics and in vivo evidence for the role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in the sequestration of infected red blood cells in a mouse model of lethal malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:240–247. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaul D K, Nagel R L, Llena J F, Shear H L. Cerebral malaria in mice: demonstration of cytoadherence of infected red blood cells and microrheologic correlates. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:512–521. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawai S, Aikawa M, Kano S, Suzuki M. A primate model for severe human malaria with cerebral involvement: Plasmodium coatneyi-infected Macaca fuscata. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993;48:630–636. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurtzhals J A, Adabayeri V, Goka B Q, Akanmori B D, Oliver-Commey J O, Nkrumah F K, Behr C, Hviid L. Low plasma concentrations of interleukin 10 in severe malarial anaemia compared with cerebral and uncomplicated malaria. Lancet. 1998;351:1768–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lou J, Donati Y R A, Juillard P, Giroud C, Vesin C, Mili N, Grau G E. Platelets play an important role in TNF-induced microvascular endothelial cell pathology. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1397–1405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacPherson G G, Warrell M J, White N J, Looareesuwan S, Warrell D A. Human cerebral malaria: a quantitative ultrastructural analysis of parasitized erythrocyte sequestration. Am J Pathol. 1985;119:385–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monsohinard C, Lou J N, Behr C, Juillard P, Grau G E. Expression of major histocompatibility complex antigens on mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells in relation to susceptibility to cerebral malaria. Immunology. 1997;92:53–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muntendam A H, Jaffar S, Bleichrodt N, van Hensbroek M B. Absence of neuropsychological sequelae following cerebral malaria in Gambian children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996;90:391–394. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(96)90518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neill A L, Hunt N H. Pathology of fatal and resolving Plasmodium berghei cerebral malaria in mice. Parasitology. 1992;105:165–175. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000074072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newbold C, Warn P, Black G, Berendt A, Craig A, Snow B, Msobo M, Peshu N, Marsh K. Receptor-specific adhesion and clinical disease in Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:389–398. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasloske B L, Howard R J. Malaria, the red cell, and the endothelium. Annu Rev Med. 1994;5:283–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.45.1.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patnaik J K, Das B S, Mishra S K, Mohanty S, Satpathy S K, Mohanty D. Vascular clogging, mononuclear cell margination, and enhanced vascular permeability in the pathogenesis of human cerebral malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:642–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rest J. Cerebral malaria in inbred mice. I. A new model and its pathology. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1982;76:410–415. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(82)90203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowe A, Obeiro J, Newbold C I, Marsh K. Plasmodium falciparum rosetting is associated with malaria severity in Kenya. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2323–2326. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.6.2323-2326.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner G D, Morrison H, Jones M, Davis T M, Looareesuwan S, Buley I D, Gatter K C, Newbold C I, Pukritayakamee S, Nagachinta B. An immunohistochemical study of the pathology of fatal malaria: evidence for widespread endothelial activation and a potential role for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in cerebral sequestration. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1057–1069. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]