Abstract

The NCCN Guidelines for Anal Carcinoma provide recommendations for the management of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal or perianal region. Primary treatment of anal cancer usually includes chemoradiation, although certain lesions can be treated with margin-negative local excision alone. Disease surveillance is recommended for all patients with anal carcinoma because additional curative-intent treatment is possible. A multidisciplinary approach including physicians from gastroenterology, medical oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, and radiology is essential for optimal patient care.

Summary

The NCCN Anal Carcinoma Guidelines Panel believes that a multidisciplinary approach including physicians from gastroenterology, medical oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, and radiology is necessary for treating patients with anal carcinoma. Recommendations for the primary treatment of perianal cancer and anal canal cancer are very similar and include continuous infusion 5-FU/mitomycin-based RT, capecitabine/mitomycin-based RT, or 5-FU/cisplatin-based RT (category 2B for 5-FU/ cisplatin) in most cases. The exceptions are small, well-differentiated perianal lesions and superficially invasive lesions, which can be treated with margin-negative local excision alone. Follow-up clinical evaluations are recommended for all patients with anal carcinoma because additional curative-intent treatment is possible. Patients with biopsy-proven evidence of locoregional progressive disease after primary treatment should undergo an APR. Following complete remission of disease, patients with a local recurrence should be treated with an APR with a groin dissection if there is clinical evidence of inguinal nodal metastasis, and patients with a regional recurrence in the inguinal nodes can be treated with an inguinal node dissection, with consideration of RT with or without chemotherapy if no prior RT to the groin was given. Patients with evidence of extrapelvic metastatic disease should be treated with up to 2 lines of systemic therapy. The panel endorses the concept that treating patients in a clinical trial has priority over standard or accepted therapy.

Overview

An estimated 8,580 new cases (2,960 men and 5,620 women) of anal cancer involving the anus, anal canal, or anorectum will occur in the United States in 2018, accounting for approximately 2.7% of digestive system cancers.1 It has been estimated that 1,160 deaths due to anal cancer will occur in the United States in 2018.1 Although considered to be a rare type of cancer, the incidence rate of invasive anal carcinoma in the United States increased by approximately 1.9-fold for men and 1.5-fold for women from the period of 1973 through 1979 to 1994 through 2000 and has continued to increase since that time (see “Risk Factors,” online, in these guidelines at NCCN.org).2–4 According to an analysis of SEER data, the incidence of anal squamous carcinoma increased at a rate of 2.9% per year from 1992–2001.5

This discussion summarizes the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) for managing squamous cell anal carcinoma, which represents the most common histologic form of the disease. Other groups have also published guidelines for the management of anal squamous cell carcinoma.6 Other types of cancers occurring in the anal region, such as adenocarcinoma or melanoma, are addressed in other NCCN Guidelines: anal adenocarcinoma and anal melanoma are managed according to the NCCN Guidelines for Rectal Cancer and the NCCN Guidelines for Melanoma, respectively. The recommendations in these guidelines are classified as category 2A except where noted, meaning that there is uniform NCCN consensus, based on lower-level evidence, that the recommendation is appropriate. The panel unanimously endorses patient participation in a clinical trial over standard or accepted therapy.

Management of Anal Carcinoma

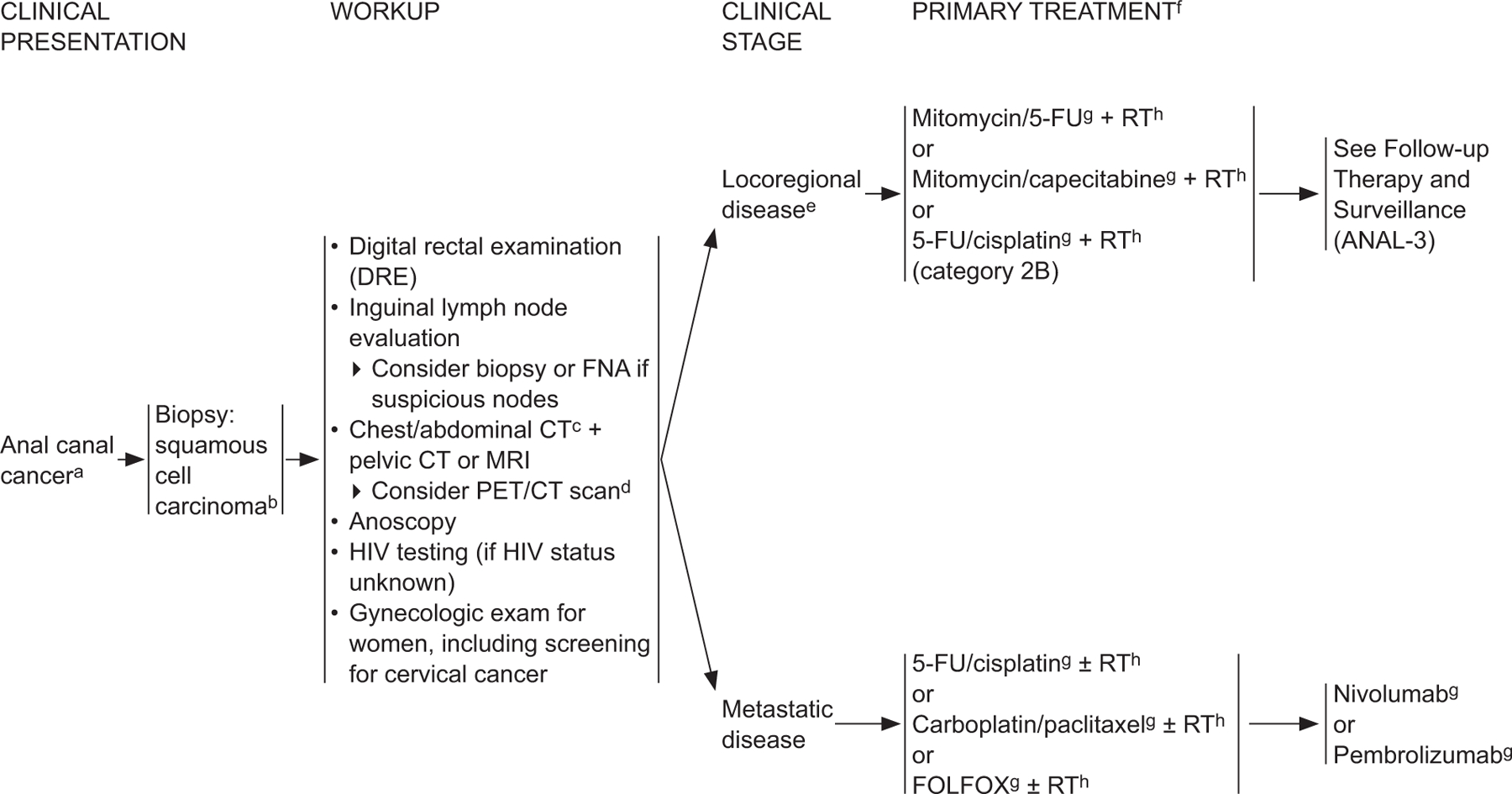

Clinical Presentation/Evaluation

Approximately 45% of patients with anal carcinoma present with rectal bleeding, and approximately 30% have either pain or the sensation of a rectal mass.7 After confirmation of squamous cell carcinoma by biopsy, the recommendations of the NCCN Anal Carcinoma Panel for the clinical evaluation of patients with anal canal or perianal cancer are very similar.

The panel recommends a thorough examination/evaluation, including a careful digital rectal examination (DRE), an anoscopic examination, and palpation of the inguinal lymph nodes, with fine-needle aspiration and/or excisional biopsy of nodes found to be enlarged by either clinical or radiologic examination. Evaluation of pelvic lymph nodes with CT or MRI of the pelvis is also recommended. These methods can also provide information on whether the tumor involves other abdominal/pelvic organs; however, assessment of T stage is primarily performed through clinical examination. A CT scan of the abdomen is also recommended to assess possible disease dissemination. Because veins of the anal region are part of the venous network associated with systemic circulation,8 chest CT scan is performed to evaluate for pulmonary metastasis. Gynecologic exam, including cervical cancer screening, is suggested for female patients due to the association of anal cancer and HPV.9

HIV testing should be performed if the patient’s HIV status is unknown, because the risk of anal carcinoma has been reported to be higher in people living with HIV (PLWH).10 Furthermore, 1 of every 7 people in the United States who are infected with HIV are not aware of their infection status,11 and infected individuals who are unaware of their HIV status do not receive the clinical care they need to reduce HIV-related morbidity and mortality and may unknowingly transmit HIV.12 HIV testing may be particularly important in patients with cancer, because identification of HIV infection has the potential to improve clinical outcomes.13 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends HIV screening for all patients in all health care settings unless the patient declines testing (opt-out screening).14

PET/CT scanning can be considered to verify staging before treatment. PET/CT scanning has been reported to be useful in the evaluation of pelvic nodes, even in patients with anal canal cancer who have normal-sized lymph nodes on CT imaging.15–20 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 retrospective and 5 prospective studies calculated pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity for detection of lymph node involvement by PET/CT to be 56% (95% CI, 45%–67%) and 90% (95% CI, 86%–93%), respectively.16 A more recent meta-analysis of 17 clinical studies calculated the pooled sensitivity and specificity for detection of lymph node involvement by PET/CT at 93% and 76%, respectively.21 The use of PET or PET/CT led to upstaging in 5% to 38% of patients and down-staging in 8% to 27% of patients. The authors reported that treatment plan modifications occurred in 12% to 59% of patients and were namely changes in radiation doses or fields. Another systematic review and meta-analysis found PET/CT to change nodal status and TNM stage in 21% and 41% of patients, respectively.22 The panel does not consider PET/CT to be a replacement for a diagnostic CT.

According to a systematic review and meta-regression, the proportion of patients who are node-positive by pretreatment clinical imaging has increased from 15.3% (95% CI, 10.5%–20.1%) in 1980 to 37.1% (95% CI, 34.0%–41.3%) in 2012 (P<.0001), likely resulting from the increased use of more-sensitive imaging techniques.23 This increase in lymph node positivity was associated with improvements in overall survival (OS) for both the lymph-node–positive and the lymph-node–negative groups. Because the proportion of patients with T3/T4 disease remained constant and therefore disease is not truly being diagnosed at more advanced stages over time, the authors attribute the improved OS results to the “Will Rogers effect.” This suggests that the average survival of both groups increases as patients with worse-than-average survival in the node-negative group migrate to the node-positive group, in which their survival is better than average. Thus, the survival of individuals has not necessarily improved over time, even though the average survival of each group has. Using simulated scenarios, the authors further conclude that the actual rate of true node-positivity is likely <30%, suggesting that it is possible some patients are being misclassified and overtreated with the increased use of highly sensitive imaging.

Primary Treatment of Nonmetastatic Anal Carcinoma

In the past, patients with invasive anal carcinoma were routinely treated with an abdominoperineal resection (APR); however, local recurrence rates were high, 5-year survival was only 40% to 70%, and the morbidity with a permanent colostomy was considerable.7 In 1974, Nigro et al24 observed complete tumor regression in some patients with anal carcinoma treated with preoperative 5-FU–based concurrent chemotherapy and radiation (chemoRT) including either mitomycin or porfiromycin, suggesting that it might be possible to cure anal carcinoma without surgery and permanent colostomy. Subsequent nonrandomized studies using similar regimens and varied doses of chemoRT provided support for this conclusion.25,26 Results of randomized trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of administering chemotherapy with radiation therapy (RT) support the use of combined modality therapy in the treatment of anal cancer.27 Summaries of clinical trials involving patients with anal cancer have been presented,28,29 and several key trials are discussed subsequently.

Chemotherapy:

A phase III study from the EORTC compared the use of chemoRT (5-FU plus mitomycin) to RT alone in the treatment of anal carcinoma. Results from this trial showed that patients in the chemoRT arm had an 18% higher rate of locoregional control at 5 years and a 32% longer colostomy-free interval.30 The United Kingdom Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research (UKCCCR) randomized ACT I trial confirmed that chemoRT with 5-FU and mitomycin was more effective in controlling local disease than RT alone (relative risk, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.42–0.69; P<.0001), although no significant differences in OS were observed at 3 years.31 A recently published follow-up study on these patients shows that a clear benefit of chemoRT remains after 13 years, including a benefit in OS.32 The median survival was 5.4 years in the RT arm and 7.6 years in the chemoRT arm. There was also a reduction in the risk of dying from anal cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67; 95% CI, 0.51–0.88, P=.004).

A few studies have addressed the efficacy and safety of specific chemotherapeutic agents in the chemoRT regimens used in the treatment of anal carcinoma.33–35 In a phase III Intergroup study, patients receiving chemoRT with the combination of 5-FU and mitomycin had a lower colostomy rate (9% vs 22%; P=.002) and a higher 4-year disease-free survival (DFS; 73% vs 51%; P=.0003) compared with patients receiving chemoRT with 5-FU alone, indicating that mitomycin is an important component of chemoRT in the treatment of anal carcinoma.35 The OS rate at 4 years was the same for the 2 groups, however, reflecting the ability to treat patients with recurrent disease with additional chemoRT or an APR.

Capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine prodrug, is an accepted alternative to 5-FU in the treatment of colon and rectal cancer.36–39 Capecitabine has therefore been assessed as an alternative to 5-FU in chemoRT regimens for nonmetastatic anal cancer.40–43 A retrospective study compared 58 patients treated with capecitabine with 47 patients treated with infusional 5-FU; both groups also received mitomycin and radiation.42 No significant differences were seen in clinical complete response, 3-year locoregional control, 3-year OS, or colostomy-free survival between the 2 groups. Another retrospective study compared 27 patients treated with capecitabine to 62 patients treated with infusional 5-FU; as in the other study, both groups also received mitomycin and radiation.41 Grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities were significantly lower in the capecitabine group, with no oncologic outcomes reported. A phase II study found that chemoRT with capecitabine and mitomycin was safe and resulted in a 6-month locoregional control rate of 86% (95% CI, 0.72–0.94) in patients with localized anal cancer.44 Although data for this regimen are limited, the panel recommends mitomycin/capecitabine plus radiation as an alternative to mitomycin/5-FU plus radiation in the setting of stage I through III anal cancer.

Cisplatin as a substitute for 5-FU was evaluated in a phase II trial, and results suggest that cisplatin-containing and 5-FU–containing chemoRT may be comparable for treatment of locally advanced anal cancer.34

The efficacy of replacing mitomycin with cisplatin has also been assessed. The phase III UK ACT II trial compared cisplatin with mitomycin and also looked at the effect of additional maintenance chemotherapy following chemoRT.45 In this study, more than 900 patients with newly diagnosed anal cancer were randomly assigned to primary treatment with either 5-FU/mitomycin or 5-FU/cisplatin with radiotherapy. A continuous course (ie, no treatment gap) of radiation of 50.4 Gy was administered in both arms, and patients in each arm were further randomized to receive 2 cycles of maintenance therapy with 5-FU and cisplatin or no maintenance therapy. At a median follow-up of 5.1 years, no differences were seen in the primary endpoint of complete response rate in either arm for the chemoRT comparison or in the primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) for the comparison of maintenance therapy versus no maintenance therapy. In addition, a secondary endpoint, colostomy, did not show differences based on the chemotherapeutic components of chemoRT. These results show that replacement of mitomycin with cisplatin in chemoRT does not affect the rate of complete response, nor does administration of maintenance therapy decrease the rate of disease recurrence after primary treatment with chemoRT in patients with anal cancer.

Cisplatin as a substitute for mitomycin in the treatment of patients with non-metastatic anal carcinoma was also evaluated in the randomized phase III Intergroup RTOG 98–11 trial. The role of induction chemotherapy was also assessed. In this study, 682 patients were randomly assigned to receive either: 1) induction 5-FU plus cisplatin for 2 cycles followed by concurrent chemoRT with 5-FU and cisplatin; or 2) concurrent chemoRT with 5-FU and mitomycin.33,46 A significant difference was seen in the primary endpoint, 5-year DFS, in favor of the mitomycin group (57.8% vs 67.8%; P=.006).46 Five-year OS was also significantly better in the mitomycin arm (70.7% vs 78.3%; P=.026).46 In addition, 5-year colostomy-free survival showed a trend toward statistical significance (65.0% vs 71.9%; P=.05), again in favor of the mitomycin group. Because the 2 treatment arms in the RTOG 98–11 trial differed with respect to use of either cisplatin or mitomycin in concurrent chemoRT and in inclusion of induction chemotherapy in the cisplatin-containing arm, it is difficult to attribute the differences to the substitution of cisplatin for mitomycin or to the use of induction chemotherapy.28,47 However, because ACT II demonstrated that the 2 chemoRT regimens are equivalent, some have suggested that results from RTOG 98–11 suggest that induction chemotherapy is probably detrimental.48

Results from ACCORD 03 also suggest that there is no benefit of a course of chemotherapy given before chemoRT.49 In this study, patients with locally advanced anal cancer were randomized to receive induction therapy with 5-FU/cisplatin or no induction therapy followed by chemoRT (they were further randomized to receive an additional radiation boost or not). No differences were seen between tumor complete response, tumor partial response, 3-year colostomy-free survival, local control, event-free survival, or 3-year OS. After a median follow-up of 50 months, no advantage to induction chemotherapy (or to the additional radiation boost) was observed, consistent with earlier results. A systematic review of randomized trials also showed no benefit to a course of induction chemotherapy.50

A recent retrospective analysis, however, suggests that induction chemotherapy preceding chemoRT may be beneficial for the subset of patients with T4 anal cancer.51 The 5-year colostomy-free survival rate was significantly better in patients with T4 cancer who received induction 5-FU/cisplatin compared with those who did not (100% vs 38% ± 16.4%; P=.0006).

The combination of 5-FU, mitomycin C, and cisplatin has also been studied in a phase II trial, but it was found to be too toxic.52 In addition, a trial assessing the safety and efficacy of capecitabine/oxaliplatin with radiation in the treatment of localized anal cancer has been completed, but final results have not yet been reported (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00093379). Preliminary results from this trial seem promising.53

Cetuximab is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor, whose anti-tumor activity depends on the presence of wild-type KRAS.54 Because KRAS mutations appear to be very rare in anal cancer,55,56 the use of an EGFR inhibitor such as cetuximab has been considered to be a promising avenue of investigation. The phase II ECOG 3205 and AIDS Malignancy Consortium 045 trials evaluated the safety and efficacy of cetuximab with cisplatin/5-FU and radiation in immunocompetent (E3205) patients and PLWH (AMC045) with anal squamous cell carcinoma. Preliminary results from these trials, reported in 2012, were encouraging with acceptable toxicity and 2-year PFS rates of 92% (95% CI, 81%–100%) and 80% (95% CI, 61%–90%) in the immunocompetent and PLWH populations, respectively.57

Longer-term results from E3205 and AMC045 were published in 2017. In a post hoc analysis of E3205, the 3-year locoregional failure rate was 21% (95% CI, 7%–26%) by Kaplan-Meier estimate.58 The toxicities associated with the regimen were substantial, with grade 4 toxicity occurring in 32% of the study population and 3 treatment-associated deaths (5%). In AMC045, the 3-year locoregional failure rate was 20% (95% CI, 10%–37%) by Kaplan-Meier estimate.59 Grade 4 toxicity and treatment-associated death rates were similar to those seen in E3205, at 26% and 4%, respectively. Two other trials that have assessed the use of cetuximab in this setting have also found it to increase toxicity, including a phase I study of cetuximab with 5-FU, cisplatin, and radiation.60 The ACCORD 16 phase II trial, which was designed to assess response rate after chemoRT with cisplatin/5-FU and cetuximab, was terminated prematurely because of extremely high rates of serious adverse events.61 The 15 evaluable patients from ACCORD 16 had a 4-year DFS rate of 53% (95% CI, 28%–79%), and 2 of the 5 patients who completed the planned treatments had locoregional recurrences.62

RT:

The optimal dose and schedule of RT for anal carcinoma also continues to be explored; it has been evaluated in a number of nonrandomized studies. In one study of patients with early-stage (T1 or Tis) anal canal cancer, most patients were effectively treated with RT doses of 40 to 50 Gy for Tis lesions and 50 to 60 Gy for T1 lesions.63 In another study, in which most patients had stage II/III anal canal cancer, local control of disease was higher in patients who received RT doses greater than 50 Gy than in those who received lower doses (86.5% vs 34%, P=.012).64 In a third study of patients with T3, T4, or lymph node–positive tumors, RT doses of ≥54 Gy administered with limited treatment breaks (less than 60 days) were associated with increased local control.65 The effect of further escalation of radiation dose was assessed in the ACCORD 03 trial, with the primary endpoint of colostomy-free survival at 3 years.49 No benefit was seen with the higher dose of radiation. These results are supported by much earlier results from the RTOG 92–08 trial66 and suggest that doses of >59 Gy provide no additional benefit to patients with anal cancer.

There is evidence that treatment interruptions, either planned or required by treatment-related toxicity, can compromise the effectiveness of treatment.19 In the phase II RTOG 92–08 trial, a planned 2-week treatment break in the delivery of chemoRT to patients with anal cancer was associated with increased locoregional failure rates and lower colostomy-free survival rates when compared with patients who only had treatment breaks for severe skin toxicity,67 although the trial was not designed for that particular comparison. In addition, the absence of a planned treatment break in the ACT II trial was considered to be at least partially responsible for the high colostomy-free survival rates observed in that study (74% at 3 years).45 Although results of these and other studies have supported the benefit of delivery of chemoRT over shorter time periods,68–70 treatment breaks in the delivery of chemoRT are required in up to 80% of patients because chemoRT-related toxicities are common.70 For example, it has been reported that one-third of patients receiving primary chemoRT for anal carcinoma at RT doses of 30 Gy in 3 weeks develop acute anoproctitis and perineal dermatitis, increasing to one-half to two-thirds of patients when RT doses of 54–60 Gy are administered in 6–7 weeks.8

Some of the reported late side effects of chemoRT include increased frequency and urgency of defecation, chronic perineal dermatitis, dyspareunia, and impotence.71,72 In some cases, severe late RT complications, such as anal ulcers, stenosis, and necrosis, may necessitate surgery involving colostomy.72 In addition, results from a retrospective cohort study of data from the SEER registry showed the risk of subsequent pelvic fracture to be 3-fold higher in older women undergoing RT for anal cancer compared with older women with anal cancer who did not receive RT.73

An increasing body of literature suggests that toxicity can be reduced with advanced radiation delivery techniques.19,74–84 Intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) uses detailed beam shaping to target specific volumes and limit the exposure of normal tissue.83 Multiple pilot studies have shown reduced toxicity while maintaining local control using IMRT. For example, in a cross-study comparison of a multicenter study of 53 patients with anal cancer treated with concurrent 5-FU/mitomycin chemotherapy and IMRT compared with patients in the 5-FU/mitomycin arm of the randomized RTOG 98–11 study, which used conventional 3D RT, the rates of grade 3/4 dermatologic toxicity were 38%/0% for IMRT-treated patients compared with 43%/5% for those undergoing conventional RT.33,83 No decrease in treatment effectiveness or local control rates was seen with use of IMRT, although the small sample size and short duration of follow-up limit the conclusions drawn from such a comparison. In one retrospective comparison between IMRT and conventional RT, IMRT was less toxic and showed better efficacy in 3-year OS, locoregional control, and PFS.85 In a larger retrospective comparison, no significant differences in local recurrence-free survival, distant metastasisfree survival, colostomy-free survival, and OS at 2 years were seen between patients receiving IMRT and those receiving 3D conformal RT, despite the fact that the IMRT group had a higher average N stage.86

The only prospective study assessing IMRT for anal cancer is the phase II dose-painted IMRT study, RTOG 0529. This trial did not meet its primary endpoint of reducing grade 2+ combined acute genitourinary and gastrointestinal adverse events by 15% compared with the chemoRT/5-FU/mitomycin arm from RTOG 98–11, which used conventional radiation.87 Of 52 evaluable patients, the grade 2+ combined acute adverse event rate was 77%; the rate in RTOG 98–11 was also 77%. However, significant reductions were seen in grade 2+ hematologic events (73% vs 85%; P=.032), grade 3+ gastrointestinal events (21% vs 36%; P=.008), and grade 3+ dermatologic events (23% vs 49%; P<.0001). Clinical outcomes of RTOG 0529 will be reported in the future and are of great interest because of the risk of underdosing (marginal miss) associated with highly conformal RT.87

A retrospective cohort study using the 2014 linkage of the SEER-Medicare database showed that IMRT is associated with higher total costs than 3D conformal radiation (median total cost, $35,890 vs $27,262; P<.001), but unplanned health care utilization costs (ie, hospitalizations and emergency department visits) are higher for those receiving conformal radiation (median, $711 vs $4,957 at 1 year; P=.02).88

Recommendations regarding RT doses follow the multifield technique used in the RTOG 98–11 trial.33 PET/CT should be considered for treatment planning.89 All patients should receive a minimum RT dose of 45 Gy to the primary cancer. The recommended initial RT dose is 30.6 Gy to the pelvis, anus, perineum, and inguinal nodes; there should be attempts to reduce the dose to the femoral heads. Field reduction off the superior field border and node-negative inguinal nodes is recommended after delivery of 30.6 Gy and 36 Gy, respectively. For patients treated with an anteroposterior-posteroanterior rather than multifield technique, the dose to the lateral inguinal region should be brought to the minimum dose of 36 Gy using an anterior electron boost matched to the posteroanterior exit field. Patients with disease clinically staged as node-positive or T2–T4 should receive an additional boost of 9 to 14 Gy. The consensus of the panel is that IMRT is preferred over 3D conformal RT in the treatment of anal carcinoma.90 IMRT requires expertise and careful target design to avoid reduction in local control by marginal miss.19 The clinical target volumes for anal cancer used in the RTOG 0529 trial have been described in detail.90 Also see https://www.rtog.org/ for more details of the contouring atlas defined by RTOG.

For untreated patients presenting with synchronous local and metastatic disease, chemoRT can be considered for local control, as described in these guidelines. For recurrence in the primary site or nodes after previous chemoRT, surgery should be performed if possible, and, if not, palliative chemoRT can be considered based on symptoms, extent of recurrence, and prior treatment.

Surgical Management:

Local excision is used for anal cancer in 2 situations. The first is for superficially invasive anal cancer, which is defined as anal cancer that has been completely excised, with ≤3 mm basement membrane invasion and a maximal horizontal spread of ≤7 mm (T1NX).91 Such lesions are being seen with increasing frequency because anal cancer screening in high-risk populations is becoming more common. These lesions are often completely excised at the time of biopsy, and local surgical resection with negative margins may be adequate treatment. A retrospective study described characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of 17 patients with completely excised invasive anal cancer, 7 of whom met the criteria for classification as superficially invasive.92 Those with positive margins (≤2 mm for anal canal cancer and <1 cm for perianal cancer) received local radiation, and all patients underwent surveillance. After a median follow-up of 45 months, no differences were seen in 5-year OS (100% for the entire cohort) or 5-year cancer recurrence-free survival rates (87% for the entire cohort) between the superficially invasive and invasive groups.

Local excision is also used for T1N0, well-differentiated perianal cancer (also see “Recommendations for the Primary Treatment of Perianal Cancer,” page 864). In these cases, a 1-cm margin is recommended. A retrospective cohort study that included 2,243 adults from the National Cancer Data Base diagnosed with T1N0 anal canal cancer between 2004 and 2012 found that the use of local excision in this population increased over time (17.3% in 2004 to 30.8% in 2012; P<.001).93 No significant difference in 5-year OS was seen based on management strategy (85.3% for local excision; 86.8% for chemoRT; P=.93).

Radical surgery in anal cancer (APR) is reserved for local recurrence or disease persistence (see “Treatment of Locally Progressive or Recurrent Anal Carcinoma,” page 865).

Treatment of Anal Cancer in PLWH:

As discussed in the full version of these guidelines (see “Risk Factors,” available online at NCCN.org), PLWH have been reported to be at increased risk for anal carcinoma.27,94–97 Some evidence suggests that antiretroviral therapy may be associated with a decrease in the incidence of high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia and its progression to anal cancer.98,99 However, the incidence of anal cancer in PLWH has not decreased much, if at all, over time.95,97,100,101

Most evidence regarding outcomes in PLWH with anal cancer comes from retrospective comparisons, a few of which found worse outcomes in PLWH.102,103 For example, a recent cohort comparison of 40 PLWH with anal canal cancer and 81 HIV-negative patients with anal canal cancer found local relapse rates to be 4 times higher in PLWH at 3 years (62% vs 13%) and found significantly higher rates of severe acute skin toxicity for PLWH.103 However, no differences in rates of complete response or 5-year OS were seen between the groups in that study. Most studies, however, have found outcomes to be similar in PLWH and HIV-negative patients.104–111 In a retrospective cohort study of 1,184 veterans diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the anus between 1998 and 2004 (15% of whom tested positive for HIV), no differences with respect to receipt of treatment or 2-year survival rates were observed when the group of PLWH was compared with the group of patients testing negative for HIV.106 Another study of 36 consecutive patients with anal cancer including 19 immunocompetent and 17 immunodeficient (14 PLWH) patients showed no difference in the efficacy or toxicity of chemoRT.110 A recent population-based study of almost 2 million patients with cancer, including 6,459 PLWH, found no increase in cancer-specific mortality for anal cancer in PLWH.112 Although the numbers of PLWH in these studies have been small, the efficacy and safety results appear similar regardless of HIV status.

Overall, the panel believes that PLWH who have anal cancer should be treated as per these guidelines and that modifications to treatment of anal cancer should not be made solely on the basis of HIV status. Additional considerations for PLWH who have anal cancer are outlined in the NCCN Guidelines for Cancer in PLWH (available at NCCN.org), including the use of normal tissue-sparing radiation techniques, the consideration of nonmalignant causes for lymphadenopathy, and the need for more frequent post-treatment surveillance anoscopy for PLWH. Poor performance status in PLWH and anal cancer may be from HIV, cancer, or other causes. The reason for poor performance status should be considered when making treatment decisions. Treatment with antiretroviral therapy may improve poor performance status related to HIV.

Recommendations for the Primary Treatment of Anal Canal Cancer:

Currently, concurrent chemoRT is the recommended primary treatment for patients with nonmetastatic anal canal cancer. Mitomycin/5-FU or mitomycin/capecitabine is administered concurrently with radiation.33,41–43 Alternatively, 5-FU/cisplatin can be given with concurrent radiation (category 2B).113 Most studies have delivered 5-FU as a protracted 96- to 120-hour infusion during the first and fifth weeks of RT, and bolus injection of mitomycin is typically given on the first or second day of the 5-FU infusion.8 Capecitabine is given orally, Monday through Friday, for 4 or 6 weeks, with bolus injection of mitomycin and concurrent radiation.41,43

An analysis of the National Cancer Database found that only 61.5% of patients with stage I anal canal cancer received chemoRT as recommended in these guidelines.114 Patients who were male, elderly, had smaller or lower-grade tumors, or who had been evaluated at academic facilities were more likely than others to be treated with excision alone. In a separate analysis of the National Cancer Database, 88% of patients with stage II/III anal canal cancer received chemoRT.115 Males, blacks, those with multiple comorbidities, and those treated in academic facilities were less likely to receive combined modality treatment.

RT is associated with significant side effects. Patients should be counseled on infertility risks and given information regarding sperm, oocyte, egg, or ovarian tissue banking before treatment. In addition, female patients should be considered for vaginal dilators and should be instructed on the symptoms of vaginal stenosis.

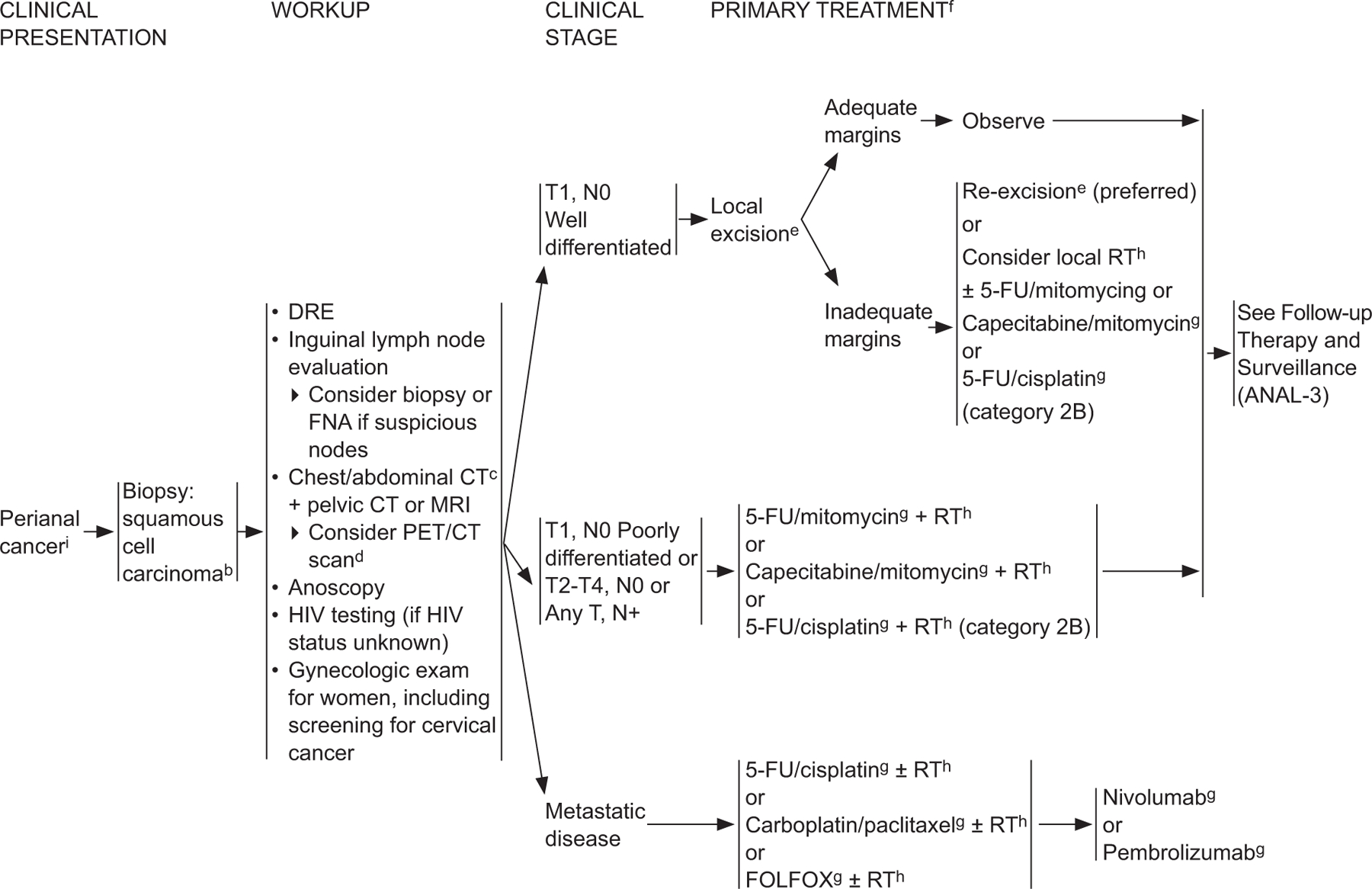

Recommendations for the Primary Treatment of Perianal Cancer:

Perianal lesions can be treated with either local excision or chemoRT depending on the clinical stage. Primary treatment for patients with T1, N0 well-differentiated perianal cancers is by local excision with adequate margins. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons defines an adequate margin as 1 cm.116 If the margins are not adequate, re-excision is the preferred treatment option. Local RT with or without continuous infusion 5-FU/mitomycin, mitomycin/capecitabine, or 5-FU/ cisplatin (category 2B) can be considered as alternative treatment options when surgical margins are inadequate. For all other perianal cancers, the treatment options are the same as for anal canal cancer (see previous sections).33,41–43,113

Treatment of Metastatic Anal Cancer

It has been reported that the most common sites of anal cancer metastasis outside of the pelvis are the liver, lung, and extrapelvic lymph nodes.117 Because anal carcinoma is a rare cancer and only 10%–20% of patients with anal carcinoma present with extrapelvic metastatic disease,117 only limited data are available on this population of patients. Despite this fact, evidence indicates that systemic therapy has some benefit in patients with metastatic anal carcinoma.

First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Anal Cancer:

Older studies showed that chemotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine-based regimen plus cisplatin benefited some patients with metastatic anal carcinoma, and metastatic disease is often treated with 5-FU/cisplatin.113,117–120 The efficacies of other regimens have also been assessed for the metastatic setting.119,121–123 In the 2018 version of these guidelines, the panel added carboplatin plus paclitaxel as an option for initial treatment of patients with metastatic anal cancer. This regimen has been assessed in several small, retrospective studies, in which it was found to be safe with evidence of durable responses.119,122,123 The ongoing phase II International Multicentre InterAACT study (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02051868) is comparing this regimen to cisplatin plus 5-FU in patients with unresectable locally recurrent or metastatic anal squamous cell carcinoma.

The panel also added FOLFOX as an option for metastatic anal cancer in 2018. The safety of FOLFOX in patients with anal cancer has been demonstrated in a case report.124 Despite the limited data for FOLFOX in this setting, the panel added it based on consensus and its current use as a standard option at many NCCN Member Institutions.

Palliative RT can be administered with chemotherapy for local control of a symptomatic bulky primary.89

Second-Line Treatment of Metastatic Anal Cancer:

A single-arm, multicenter phase 2 trial assessed the safety and efficacy of the anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab in the refractory metastatic setting.125 Two complete responses and 7 partial responses were seen among the 37 enrolled participants who received at least one dose, for a response rate of 24% (95% CI, 15%–33%). The KEYNOTE-028 trial is a multicohort, phase 1b trial of the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab in 24 patients with PD-L1–positive advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal.126 Four partial responses were seen, for a response rate of 17% (95% CI, 5%–37%), and 10 patients (42%) had stable disease, for a disease control rate of 58%. In both trials, toxicities were manageable, with 13% and 17% experiencing grade 3 adverse events with nivolumab and pembrolizumab, respectively.125,126

Although further studies of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are warranted, the panel added nivolumab and pembrolizumab as options for patients with metastatic anal cancer who have progressed on first-line chemotherapy in the 2018 version of these guidelines. Microsatellite instability/mismatch repair testing is not required. Microsatellite instability is uncommon in anal cancer,127 and as discussed previously, responses to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors occur in 20% to 24% of patients.125,126 Anal cancers may be responsive to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors because they often have high PD-L1 expression and/or a high tumor mutational load despite being microsatellite stable.127

The panel also notes that platinum-based chemotherapy should not be given in second line if disease progressed on platinum-based therapy in first line.

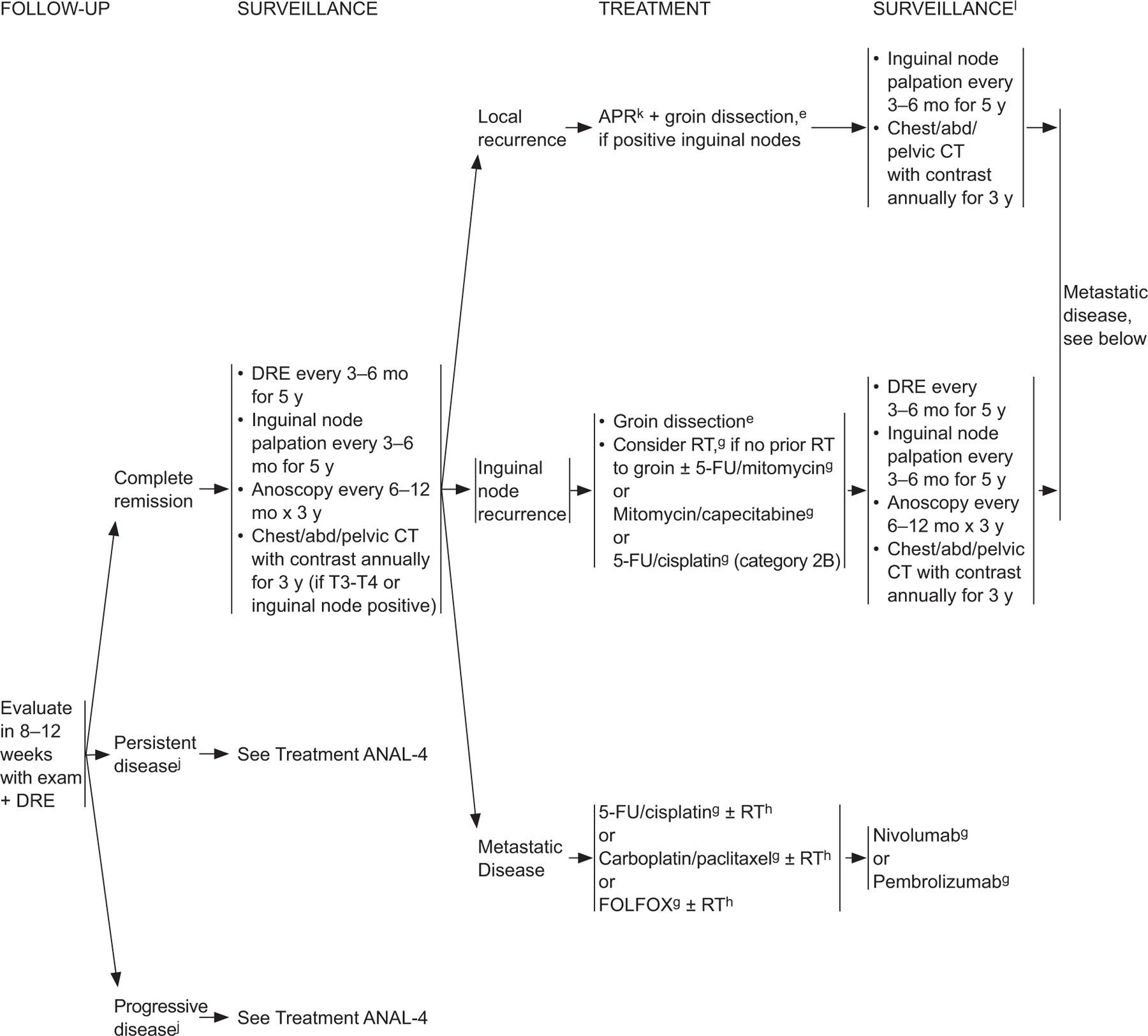

Surveillance Following Primary Treatment

After primary treatment of nonmetastatic anal cancer, the surveillance and follow-up treatment recommendations for perianal and anal canal cancer are the same. Patients are re-evaluated using DRE between 8 and 12 weeks after completion of chemoRT. Following re-evaluation, patients are classified according to whether they have a complete remission of disease, persistent disease, or progressive disease. Patients with persistent disease but without evidence of progression may be managed with close follow-up (in 4 weeks) to see if further regression occurs.

The National Cancer Research Institute’s ACT II study compared different chemoRT regimens and found no difference in OS or PFS.45 Interestingly, 72% of patients in this trial who did not show a complete response at 11 weeks from the start of treatment had experienced a complete response by 26 weeks.128 Based on these results, the panel believes it may be appropriate to follow patients who have not shown a complete clinical response with persistent anal cancer for up to 6 months after completion of radiation and chemotherapy, as long as there is no evidence of progressive disease during this period of follow-up. Persistent disease may continue to regress even at 26 weeks from the start of treatment, and APR can thereby be avoided in some patients. In these patients, observation and re-evaluation should be performed at 3-month intervals. If biopsy-proven disease progression occurs, further intensive treatment is indicated (see “Treatment of Locally Progressive or Recurrent Anal Carcinoma,” on this page).

Although a clinical assessment of progressive disease requires histologic confirmation, patients can be classified as having a complete remission without biopsy verification if clinical evidence of disease is absent. The panel recommends that these patients undergo evaluation every 3–6 months for 5 years, including DRE, anoscopic evaluation, and inguinal node palpation. Annual chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT with contrast is recommended for 3 years for patients who initially had locally advanced disease (ie, T3/T4 tumor) or node-positive cancers.

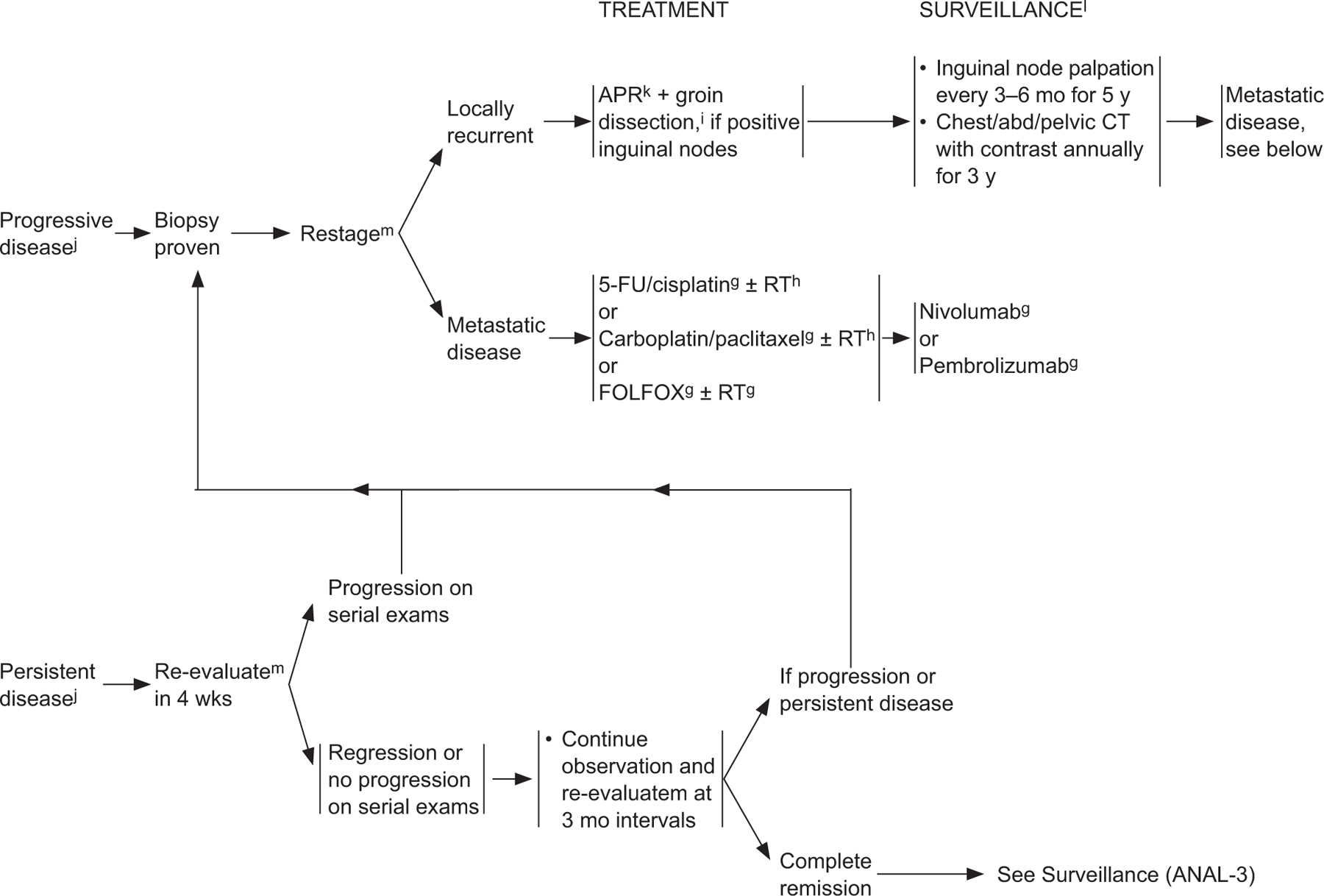

Treatment of Locally Progressive or Recurrent Anal Carcinoma

Despite the effectiveness of chemoRT in the primary treatment of anal carcinoma, rates of locoregional failure of 10% to 30% have been reported.129,130 Some of the disease characteristics that have been associated with higher recurrence rates after chemoRT include higher T stage and higher N stage (also see the section on “Prognostic Factors,” in the full NCCN Guidelines for Anal Cancer at NCCN.org).131

Evidence of progression found on DRE should be followed up using biopsy as well as restaging with CT and/or PET/CT imaging. Patients with biopsy-proven locally progressive disease are candidates for radical surgery with an APR and colostomy.130

A recent multicenter retrospective cohort study looked at the cause-specific colostomy rates in 235 patients with anal cancer who were treated with radiotherapy or chemoRT from 1995 to 2003.132 The 5-year cumulative incidence rates for tumor-specific and therapy-specific colostomy were 26% (95% CI, 21%–32%) and 8% (95% CI, 5%–12%), respectively. Larger tumor size (>6 cm) was a risk factor for tumor-specific colostomy, and local excision before RT was a risk factor for therapy-specific colostomy. However, it should be noted that these patients were treated with older chemotherapy and RT regimens, which could account for these high colostomy rates.133

In studies involving a minimum of 25 patients undergoing an APR for anal carcinoma, 5-year survival rates of 39% to 66% have been observed.129,130,134–137 Complication rates were reported to be high in some of these studies. Factors associated with worse prognosis following APR include an initial presentation of node-positive disease and RT doses <55 Gy used in the treatment of primary disease.130

The general principles for APR technique are similar to those for distal rectal cancer and include the incorporation of meticulous total mesorectal excision. However, APR for anal cancer may require wider lateral perianal margins than are required for rectal cancer. A recent retrospective analysis of the medical records of 14 patients who received intraoperative RT during APR revealed that intraoperative RT is unlikely to improve local control or to give a survival benefit.138 This technique is not recommended during surgery in patients with recurrent anal cancer.

Because of the necessary exposure of the perineum to radiation, patients with anal cancer are prone to poor perineal wound healing. It has been shown that for patients undergoing an APR that was preceded by RT, closure of the perineal wound using rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap reconstruction results in decreased perineal wound complications.139,140 Reconstructive tissue flaps for the perineum, such as the vertical rectus or local myocutaneous flaps, should therefore be considered for patients with anal cancer undergoing an APR.

Inguinal node dissection is recommended for recurrence in that area and for patients who require an APR but have already received groin radiation. Inguinal node dissection can be performed with or without an APR depending on whether disease is isolated to the groin or has occurred in conjunction with recurrence or persistence at the primary site.

Patients who develop inguinal node metastasis who do not undergo an APR can be considered for palliative RT to the groin with or without 5-FU/mitomycin, mitomycin/capecitabine, or 5-FU/cisplatin (category 2B for 5-FU/cisplatin), if no prior RT to the groin was given. Radiation therapy technique and doses are dependent on dosing and technique of prior treatment (see the guidelines previously discussed).

Surveillance Following Treatment of Recurrence:

Following APR, patients should undergo re-evaluation every 3–6 months for 5 years, including clinical evaluation for nodal metastasis (ie, inguinal node palpation). In addition, it is recommended that these patients undergo annual chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT with contrast for 3 years. In one retrospective study of 105 patients with anal canal carcinoma who had an APR between 1996 and 2009, the overall recurrence rate after APR was 43%.141 Those with T3/4 tumors or involved margins were more likely to experience recurrence. The 5-year survival rate after APR has been reported to be 60%–64%.141,142

After treatment of inguinal node recurrence, patients should have a DRE and inguinal node palpation every 3–6 months for 5 years. In addition, anoscopy every 6–12 months and annual chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT with contrast imaging are recommended for 3 years.

Survivorship

The panel recommends that a prescription for survivorship and transfer of care to the primary care physician be written.143 The oncologist and primary care provider should have defined roles in the surveillance period, with roles communicated to the patient. The care plan should include an overall summary of treatments received, including surgeries, radiation treatments, and chemotherapy. The possible expected time to resolution of acute toxicities, long-term effects of treatment, and possible late sequelae of treatment should be described. Finally, surveillance and health behavior recommendations should be part of the care plan.

Disease-preventive measures, such as immunizations; early disease detection through periodic screening for second primary cancers (eg, breast, cervical, or prostate cancers); and routine good medical care and monitoring are recommended (see the NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship, available at NCCN.org). Additional health monitoring should be performed as indicated under the care of a primary care physician. Survivors are encouraged to maintain a therapeutic relationship with a primary care physician throughout their lifetime.144

Other recommendations include monitoring for late sequelae of anal cancer or the treatment of anal cancer. Late toxicity from pelvic radiation can include bowel dysfunction (ie, increased stool frequency, fecal incontinence, flatulence, rectal urgency), urinary dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction (ie, impotence, dyspareunia, reduced libido).145–148 Anal cancer survivors also report significantly reduced global quality of life, with increased frequency of somatic symptoms including fatigue, dyspnea, pain, and insomnia.145,149,150 Therefore, survivors of anal cancer should be screened regularly for distress.

The NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship, available at NCCN.org, provide screening, evaluation, and treatment recommendations for common consequences of cancer and cancer treatment to aid health care professionals who work with survivors of adult-onset cancer in the post-treatment period, including those in specialty cancer survivor clinics and primary care practices. The NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship include many topics with potential relevance to survivors of anal cancer, including anxiety, depression, and distress; cognitive dysfunction; fatigue; pain; sexual dysfunction; sleep disorders; healthy lifestyles; and immunizations. Concerns related to employment, insurance, and disability are also discussed.

ANAL-1

aThe superior border of the functional anal canal, separating it from the rectum, has been defined as the palpable upper border of the anal sphincter and puborectalis muscles of the anorectal ring. It is approximately 3 to 5 cm in length, and its inferior border starts at the anal verge, the lowermost edge of the sphincter muscles, corresponding to the introitus of the anal orifice.

bFor melanoma histology, see the NCCN Guidelines for Melanoma*; for adenocarcinoma, see the NCCN Guidelines for Rectal Cancer (elsewhere in this issue).

cCT should be with IV and oral contrast. Pelvic MRI with contrast.

dPET/CT scan does not replace a diagnostic CT. PET/CT performed skull base to mid-thigh.

eSee Principles of Surgery (ANAL-A†).

fModifications to cancer treatment should not be made solely on the basis of HIV status. See NCCN Guidelines for Cancer in People Living with HIV*.

gSee Principles of Chemotherapy (ANAL-B†).

hSee Principles of Radiation Therapy (ANAL-C†).

*To view the most recent version of these guidelines, visit NCCN.org.

†Available online, in these guidelines, at NCCN.org.

ANAL-2

bFor melanoma histology, see the NCCN Guidelines for Melanoma*; for adenocarcinoma, see the NCCN Guidelines for Rectal Cancer (elsewhere in this issue).

cCT should be with IV and oral contrast. Pelvic MRI with contrast.

dPET/CT scan does not replace a diagnostic CT. PET/CT performed skull base to mid-thigh.

eSee Principles of Surgery (ANAL-A†).

fModifications to cancer treatment should not be made solely on the basis of HIV status.

gSee Principles of Chemotherapy (ANAL-B†).

hSee Principles of Radiation Therapy (ANAL-C†).

iThe perianal region starts at the anal verge and includes the perianal skin over a 5-cm radius from the squamous mucocutaneous junction.

*To view the most recent version of these guidelines, visit NCCN.org.

†Available online, in these guidelines, at NCCN.org.

ANAL-3

eSee Principles of Surgery (ANAL-A†).

gSee Principles of Chemotherapy (ANAL-B†).

hSee Principles of Radiation Therapy (ANAL-C†).

jBased on the results of the ACT-II study, it may be appropriate to follow patients who have not achieved a complete clinical response with persistent anal cancer up to 6 months following completion of radiation therapy and chemotherapy as long as there is no evidence of progressive disease during this period of follow-up. Persistent disease may continue to regress even at 26 weeks from the start of treatment. James RD, Glynne-Jones R, Meadows HM, et al. Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (Act II): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2×2 factorial trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:516–524.

kConsider muscle flap reconstruction

lSee Principles of Survivorship (ANAL-D†).

†Available online, in these guidelines, at NCCN.org.

ANAL-4

gSee Principles of Chemotherapy (ANAL-B†).

hSee Principles of Radiation Therapy (ANAL-C†).

jBased on the results of the ACT-II study, it may be appropriate to follow patients who have not achieved a complete clinical response with persistent anal cancer up to 6 months following completion of radiation therapy and chemotherapy as long as there is no evidence of progressive disease during this period of follow-up. Persistent disease may continue to regress even at 26 weeks from the start of treatment. James RD, Glynne-Jones R, Meadows HM, et al. Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (Act II): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2×2 factorial trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:516–524.

kConsider muscle flap reconstruction.

lSee Principles of Survivorship (ANAL-D†)

mUtilize imaging studies as per initial workup.

†Available online, in these guidelines, at NCCN.org.

Individual Disclosures for Anal Carcinoma Panel

| Panel Member | Clinical Research Support/Data Safety Monitoring Board | Scientific Advisory Boards, Consultant, or Expert Witness | Promotional Advisory Boards, Consultant, or Speakers Bureau | Date Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mahmoud M. Al-Hawary, MD | None | None | None | 4/13/18 |

| Al B. Benson III, MD | None | Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Celgene Corporation; Eli Lilly and Company; EMD Serono, Inc.; Exelixis Inc.; Genentech, Inc.; Genomic Health, Inc.; ImClone Systems Incorporated; Merck & Co., Inc.; Oncosil Medical; sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC; Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Taiho Parmaceuticals Co., Ltd. | None | 2/20/18 |

| Lynette Cederquist, MD | None | None | None | 12/4/17 |

| Yi-Jen Chen, MD, PhD | None | None | None | 6/6/18 |

| Kristen K. Ciombor, MD | AbbVie, Inc.; Amgen Inc.; Array Biopharma Inc.; Bayer HealthCare; Boston Biomedical, Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Daiichi Sankyo Co.; Incyte Corporation; MedImmune Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; NuCana; Pfizer Inc.; and sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC | None | None | 5/16/18 |

| Stacey Cohen, MD | None | None | None | 6/11/18 |

| Harry S. Cooper, MD | None | None | None | 7/4/17 |

| Dustin Deming, MD | Abbott Laboratories; and Merck & Co., Inc. | Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; and Novocure Ltd | None | 8/1/17 |

| Paul F. Engstrom, MD | None | None | None | 6/4/18 |

| Jean L. Grem, MD | Elion Oncology; and ICON | None | None | 5/25/18 |

| Axel Grothey, MD | None | Bayer HealthCare; Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Genentech, Inc.; and Guardant Health Inc. | None | 9/15/17 |

| Howard S. Hochster, MD | None | Amgen Inc.; Bayer HealthCare; Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eleison Pharma; Eli Lilly and Company; Genentech, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; and Taiho Parmaceuticals Co., Ltd. | None | 8/3/17 |

| Sarah Hoffe, MD | None | None | None | 7/27/17 |

| Steven Hunt, MD | None | None | None | 6/1/18 |

| Ahmed Kamel, MD | Boston Scientific Corporation | Boston Scientific Corporation; and Sirtex Medical | Bard Peripheral Vascular; and Boston Scientific Corporation | 3/12/18 |

| Natalie Kirilcuk, MD | None | None | None | 3/21/18 |

| Smitha Krishnamurthi, MD | CytomX Therapeutics, Inc.; and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | None | None | 4/30/18 |

| Wells A. Messersmith, MD | Alexo Therapeutics, Inc.; D3 Pharma Limited; Genentech, Inc.; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Immunomedics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; OncoMed Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Pfizer Inc.; Purdue Pharma LP; and Roche Laboratories, Inc. | Purdue Pharma LP | None | 8/29/17 |

| Jeffrey Meyerhardt, MD, MPH | Ignyta, Inc. | Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd | None | 3/16/18 |

| Mary F. Mulcahy, MD | None | None | None | 4/26/18 |

| James D. Murphy, MD, MS | None | None | None | 4/23/18 |

| Steven Nurkin, MD, MS | None | None | None | 6/3/18 |

| Leonard Saltz, MD | Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. | None | None | 4/4/18 |

| Sunil Sharma, MD | None | Arrien Pharmaceuticals; and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation | ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Blend Therapeutics; Clovis Oncology; Exelixis Inc.; Guardant Health Inc.; and LSK Biopharma | 10/18/17 |

| David Shibata, MD | None | None | None | 10/19/17 |

| John M. Skibber, MD | None | None | None | 4/13/18 |

| Constantinos T. Sofocleous, MD, PhD, FSIR, FCIRSEa | None | Sirtex Medical Inc. | Sirtex Medical Inc. | 8/1/17 |

| Elena M. Stoffel, MD, MPH | Cancer Prevention Pharmaceuticals | None | None | 11/22/17 |

| Eden Stotsky-Himelfarb, BSN, RN | None | None | None | 6/11/18 |

| Alan P. Venook, MD | Halozyme, Inc. | AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; Eisai Inc.; Genentech, Inc.; Roche Laboratories, Inc.; and Taiho Parmaceuticals Co., Ltd. | None | 6/4/18 |

| Christopher G. Willett, MD | Extrinsic Health | Extrinsic Health | None | 9/22/17 |

| Evan Wuthrick, MD | None | None | None | 6/22/17 |

The following individuals have disclosed that they have an Employment/Governing Board, Patent, Equity, or Royalty: Constantinos T. Sofocleous, MD, PhD, FSIR, FCIRSE: Ethicon Inc.

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus.

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

Please Note.

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult the NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way. The full NCCN Guidelines for Anal Carcinoma Panel are not printed in this issue of JNCCN but can be accessed online at NCCN.org.

Footnotes

Disclosures for the NCCN Anal Carcinoma Panel

At the beginning of each NCCN Guidelines panel meeting, panel members review all potential conflicts of interest. NCCN, in keeping with its commitment to public transparency, publishes these disclosures for panel members, staff, and NCCN itself.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Anal Carcinoma Panel members can be found on page 871. (The most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures are available on the NCCN Web site at NCCN.org.)

These guidelines are also available on the Internet. For the latest update, visit NCCN.org.

Contributor Information

Al B. Benson, III, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

Alan P. Venook, UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Mahmoud M. Al-Hawary, University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center.

Lynette Cederquist, UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

Yi-Jen Chen, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Kristen K. Ciombor, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

Stacey Cohen, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

Harry S. Cooper, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Dustin Deming, University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center.

Paul F. Engstrom, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Jean L. Grem, Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center.

Axel Grothey, Mayo Clinic Cancer Center.

Howard S. Hochster, Yale Cancer Center/Smilow Cancer Hospital.

Sarah Hoffe, Moffitt Cancer Center.

Steven Hunt, Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.

Ahmed Kamel, University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Natalie Kirilcuk, Stanford Cancer Institute.

Smitha Krishnamurthi, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center/University Hospitals Seidman Cancer Center and Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute.

Wells A. Messersmith, University of Colorado Cancer Center.

Jeffrey Meyerhardt, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Mary F. Mulcahy, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

James D. Murphy, UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

Steven Nurkin, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Leonard Saltz, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Sunil Sharma, Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah.

David Shibata, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/The University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

John M. Skibber, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Constantinos T. Sofocleous, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Elena M. Stoffel, University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center.

Eden Stotsky-Himelfarb, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins.

Christopher G. Willett, Duke Cancer Institute.

Evan Wuthrick, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute.

Deborah A. Freedman-Cass, NCCN Staff.

Kristina M. Gregory, NCCN Staff.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975–2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:175–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson LG, Madeleine MM, Newcomer LM, et al. Anal cancer incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results experience, 1973–2000. Cancer 2004;101:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson RA, Levine AM, Bernstein L, et al. Changing patterns of anal canal carcinoma in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1569–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiels MS, Kreimer AR, Coghill AE, et al. Anal cancer incidence in the United States, 1977–2011: distinct patterns by histology and behavior. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2015;24:1548–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glynne-Jones R, Nilsson PJ, Aschele C, et al. Anal cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Radiother Oncol 2014;111:330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan DP, Compton CC, Mayer RJ. Carcinoma of the anal canal. N Engl J Med 2000;342:792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings BJ, Ajani JA, Swallow CJ. Cancer of the anal region. In: DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, et al. , eds. Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology, 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frisch M, Glimelius B, van den Brule AJ, et al. Sexually transmitted infection as a cause of anal cancer. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1350–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frisch M, Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1500–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Statistics. HIV.gov Web site Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics. Accessed August 16, 2017.

- 12.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;39:446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiao EY, Dezube BJ, Krown SE, et al. Time for oncologists to opt in for routine opt-out HIV testing? JAMA 2010;304:334–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55:1–17; quiz CE1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhuva NJ, Glynne-Jones R, Sonoda L, et al. To PET or not to PET? That is the question. Staging in anal cancer. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2078–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldarella C, Annunziata S, Treglia G, et al. Diagnostic performance of positron emission tomography/computed tomography using fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose in detecting locoregional nodal involvement in patients with anal canal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific World Journal 2014:196068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cotter SE, Grigsby PW, Siegel BA, et al. FDG-PET/CT in the evaluation of anal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;65:720–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mistrangelo M, Pelosi E, Bello M, et al. Role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography in the management of anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;84:66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pepek JM, Willett CG, Czito BG. Radiation therapy advances for treatment of anal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trautmann TG, Zuger JH. Positron Emission Tomography for pretreatment staging and posttreatment evaluation in cancer of the anal canal. Mol Imaging Biol 2005;7:309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahmud A, Poon R, Jonker D. PET imaging in anal canal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Radiol 2017;90:20170370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones M, Hruby G, Solomon M, et al. The role of FDG-PET in the initial staging and response assessment of anal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:3574–3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sekhar H, Zwahlen M, Trelle S, et al. Nodal stage migration and prognosis in anal cancer: a systematic review, meta-regression, and simulation study. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1348–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nigro ND, Vaitkevicius VK, Considine B. Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum 1974;17:354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cummings BJ, Keane TJ, O’Sullivan B, et al. Epidermoid anal cancer: treatment by radiation alone or by radiation and 5-fluorouracil with and without mitomycin C. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1991;21:1115–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papillon J, Chassard JL. Respective roles of radiotherapy and surgery in the management of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal margin. Series of 57 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 1992;35:422–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uronis HE, Bendell JC. Anal cancer: an overview. Oncologist 2007;12:524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czito BG, Willett CG. Current management of anal canal cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2009;11:186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glynne-Jones R, Lim F. Anal cancer: an examination of radiotherapy strategies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011;79:1290–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartelink H, Roelofsen F, Eschwege F, et al. Concomitant radiotherapy and chemotherapy is superior to radiotherapy alone in the treatment of locally advanced anal cancer: results of a phase III randomized trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiotherapy and Gastrointestinal Cooperative Groups. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2040–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Epidermoid anal cancer: results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, and mitomycin. UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party. UK Co-ordinating Committee on Cancer Research. Lancet 1996;348:1049–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Northover J, Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D, et al. Chemoradiation for the treatment of epidermoid anal cancer: 13-year follow-up of the first randomised UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial (ACT I). Br J Cancer 2010;102:1123–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ajani JA, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. Fluorouracil, mitomycin, and radiotherapy vs fluorouracil, cisplatin, and radiotherapy for carcinoma of the anal canal: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:1914–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crehange G, Bosset M, Lorchel F, et al. Combining cisplatin and mitomycin with radiotherapy in anal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flam M, John M, Pajak TF, et al. Role of mitomycin in combination with fluorouracil and radiotherapy, and of salvage chemoradiation in the definitive nonsurgical treatment of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal: results of a phase III randomized intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:2527–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hofheinz RD, Wenz F, Post S, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with capecitabine versus fluorouracil for locally advanced rectal cancer: a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Connell MJ, Colangelo LH, Beart RW, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin in the preoperative multimodality treatment of rectal cancer: surgical end points from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project trial R-04. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1927–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Twelves C, Scheithauer W, McKendrick J, et al. Capecitabine versus 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: final results from the X-ACT trial with analysis by age and preliminary evidence of a pharmacodynamic marker of efficacy. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1190–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, et al. Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2696–2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glynne-Jones R, Meadows H, Wan S, et al. EXTRA--a multicenter phase II study of chemoradiation using a 5 day per week oral regimen of capecitabine and intravenous mitomycin C in anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;72:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodman K, Rothenstein D, Lajhem C, et al. Capecitabine plus mitomycin in patients undergoing definitive chemoradiation for anal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;90:S32–S33. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meulendijks D, Dewit L, Tomasoa NB, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with capecitabine for locally advanced anal carcinoma: an alternative treatment option. Br J Cancer 2014;111:1726–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thind G, Johal B, Follwell M, Kennecke HF. Chemoradiation with capecitabine and mitomycin-C for stage I-III anal squamous cell carcinoma. Radiat Oncol 2014;9:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oliveira SC, Moniz CM, Riechelmann R, et al. Phase II study of capecitabine in substitution of 5-FU in the chemoradiotherapy regimen for patients with localized squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. J Gastrointest Cancer 2016;47:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.James RD, Glynne-Jones R, Meadows HM, et al. Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2 × 2 factorial trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gunderson LL, Winter KA, Ajani JA, et al. Long-term update of US GI Intergroup RTOG 98–11 phase III trial for anal carcinoma: survival, relapse, and colostomy failure with concurrent chemoradiation involving fluorouracil/mitomycin versus fluorouracil/cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4344–4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eng C, Crane CH, Rodriguez-Bigas MA. Should cisplatin be avoided in the treatment of locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;6:16–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abbas A, Yang G, Fakih M. Management of anal cancer in 2010. Part 2: current treatment standards and future directions. Oncology (Williston Park) 2010;24:417–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peiffert D, Tournier-Rangeard L, Gerard JP, et al. Induction chemotherapy and dose intensification of the radiation boost in locally advanced anal canal carcinoma: final analysis of the randomized UNICANCER ACCORD 03 trial. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1941–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spithoff K, Cummings B, Jonker D, et al. Chemoradiotherapy for squamous cell cancer of the anal canal: a systematic review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2014;26:473–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moureau-Zabotto L, Viret F, Giovaninni M, et al. Is neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to radio-chemotherapy beneficial in T4 anal carcinoma? J Surg Oncol 2011;104:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sebag-Montefiore D, Meadows HM, Cunningham D, et al. Three cytotoxic drugs combined with pelvic radiation and as maintenance chemotherapy for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (SCCA): long-term follow-up of a phase II pilot study using 5-fluorouracil, mitomycin C and cisplatin. Radiother Oncol 2012;104:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eng C, Chang GJ, Das P, et al. Phase II study of capecitabine and oxaliplatin with concurrent radiation therapy (XELOX-XRT) for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(suppl 15):Abstract 4116. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cetuximab (Erbitux®) [package insert]. Branchburg, NJ: ImClone Systems Inc; 2015. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/125084s262lbl.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- 55.Van Damme N, Deron P, Van Roy N, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor and K-RAS status in two cohorts of squamous cell carcinomas. BMC Cancer 2010;10:189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zampino MG, Magni E, Sonzogni A, Renne G. K-ras status in squamous cell anal carcinoma (SCC): it’s time for target-oriented treatment? Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2009;65:197–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garg M, Lee JY, Kachnic LA, et al. Phase II trials of cetuximab (CX) plus cisplatin (CDDP), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and radiation (RT) in immunocompetent (ECOG 3205) and HIV-positive (AMC045) patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal (SCAC): Safety and preliminary efficacy results [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(suppl 15):Abstract 4030. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garg MK, Zhao F, Sparano JA, et al. Cetuximab plus chemoradiotherapy in immunocompetent patients with anal carcinoma: a phase II Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-American College of Radiology Imaging Network Cancer Research Group trial (E3205). J Clin Oncol 2017;35:718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sparano JA, Lee JY, Palefsky J, et al. Cetuximab plus chemoradiotherapy for HIV-associated anal carcinoma: a phase II AIDS Malignancy Consortium trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olivatto LO, Vieira FM, Pereira BV, et al. Phase 1 study of cetuximab in combination with 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced anal canal carcinoma. Cancer 2013;119:2973–2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deutsch E, Lemanski C, Pignon JP, et al. Unexpected toxicity of cetuximab combined with conventional chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced anal cancer: results of the UNICANCER ACCORD 16 phase II trial. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2834–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levy A, Azria D, Pignon JP, et al. Low response rate after cetuximab combined with conventional chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced anal cancer: long-term results of the UNICANCER ACCORD 16 phase II trial. Radiother Oncol 2015;114:415–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ortholan C, Ramaioli A, Peiffert D, et al. Anal canal carcinoma: early-stage tumors < or =10 mm (T1 or Tis): therapeutic options and original pattern of local failure after radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;62:479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferrigno R, Nakamura RA, Dos Santos Novaes PE, et al. Radiochemotherapy in the conservative treatment of anal canal carcinoma: retrospective analysis of results and radiation dose effectiveness. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;61:1136–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang K, Haas-Kogan D, Weinberg V, Krieg R. Higher radiation dose with a shorter treatment duration improves outcome for locally advanced carcinoma of anal canal. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:895–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.John M, Pajak T, Flam M, et al. Dose escalation in chemoradiation for anal cancer: preliminary results of RTOG 92–08. Cancer J Sci Am 1996;2:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Konski A, Garcia M, Jr., John M, et al. Evaluation of planned treatment breaks during radiation therapy for anal cancer: update of RTOG 92–08. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;72:114–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ben-Josef E, Moughan J, Ajani JA, et al. Impact of overall treatment time on survival and local control in patients with anal cancer: a pooled data analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trials 87–04 and 98–11. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:5061–5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Graf R, Wust P, Hildebrandt B, et al. Impact of overall treatment time on local control of anal cancer treated with radiochemotherapy. Oncology 2003;65:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roohipour R, Patil S, Goodman KA, et al. Squamous-cell carcinoma of the anal canal: predictors of treatment outcome. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allal AS, Sprangers MA, Laurencet F, et al. Assessment of long-term quality of life in patients with anal carcinomas treated by radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 1999;80:1588–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Bree E, van Ruth S, Dewit LG, Zoetmulder FA. High risk of colostomy with primary radiotherapy for anal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baxter NN, Habermann EB, Tepper JE, et al. Risk of pelvic fractures in older women following pelvic irradiation. JAMA 2005;294:2587–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Call JA, Prendergast BM, Jensen LG, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for anal cancer: results from a multi-institutional retrospective cohort study. Am J Clin Oncol 2014;39:8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen YJ, Liu A, Tsai PT, et al. Organ sparing by conformal avoidance intensity-modulated radiation therapy for anal cancer: dosimetric evaluation of coverage of pelvis and inguinal/femoral nodes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;63:274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chuong MD, Freilich JM, Hoffe SE, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy vs. 3D conformal radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2013;6:39–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.DeFoe SG, Beriwal S, Jones H, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for anal carcinoma--clinical outcomes in a large National Cancer Institute-designated integrated cancer centre network. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2012;24:424–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Franco P, Mistrangelo M, Arcadipane F, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with simultaneous integrated boost combined with concurrent chemotherapy for the treatment of anal cancer patients: 4-year results of a consecutive case series. Cancer Invest 2015;33:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kachnic LA, Tsai HK, Coen JJ, et al. Dose-painted intensity-modulated radiation therapy for anal cancer: a multi-institutional report of acute toxicity and response to therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lin A, Ben-Josef E. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for the treatment of anal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2007;6:716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Milano MT, Jani AB, Farrey KJ, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in the treatment of anal cancer: toxicity and clinical outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;63:354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mitchell MP, Abboud M, Eng C, et al. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with concurrent chemotherapy for anal cancer: outcomes and toxicity. Am J Clin Oncol 2014;37:461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]