Abstract

Negative behaviors often are directed toward nursing staff in verbal or physical assaults. Nursing staff on non-psychiatric units may not be prepared to manage such situations and need additional support. Behavioral Emergency Response Teams (BERTs) have been effective in supporting nursing staff faced with patients exhibiting these behaviors.

Keywords: behavioral emergencies, non-psychiatric units, nursing, Brøset Violence Screening, safety, psychosocial and behavioural, teamwork/collaboration

Up to 97% of nurses are exposed to negative behaviors each year (de la Fuente et al., 2019). The American Hospital Association (2018) estimated cost associated with violence in health care for 2016 was $2.7 billion, with $429 million in medical care, staffing, indemnity, and other costs resulting from violence against hospital employees. Patients on non-emergency (non-ED) or non-inpatient psychiatric units (non-IPU) can demonstrate negative or violent behaviors. Nursing staff on these units may not be prepared to manage such situations and need additional support. Although many nurses have completed mandatory violence prevention education courses, this prevention strategy has not influenced nurses’ perception of feeling safe at work (Havaei et al., 2019).

Additionally, misperception may result in patient care neglect, segregation or expulsion of patients, seclusion/isolation, or even unnecessary physical or chemical restraint of patients with mental illness (Havaei et al., 2019). To avoid adverse outcomes, nurses need adequate resources for patient de-escalation. Use of an emergency response team is described in this article.

Background

Violence typically is related to circumstances and environment rather than patient population (Pekurinen et al., 2017). However, nurses care for patients at increased risk of displaying negative and violent behaviors, including patients with traumatic brain injury, postictal psychosis, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and hospital-induced delirium (Mulkey & Munro, 2021). Violent behaviors also may be displayed by family and visitors at times of increased stress. These negative behaviors often are directed toward nursing staff, who may be assaulted verbally or physically (Bean, 2018).

Perceptions related to these occurrences have impacted job satisfaction and patient outcomes negatively (Macfarlane & Cunningham, 2017). Staffing shortages, poor perception of nurse leaders, inefficient communication with the care team, and decreased autonomy are among the reasons nurses may perceive their units to be unstable. When these perceptions are combined with episodes of violent behavior, Macfarlane and Cunningham suggested awareness increases, thereby worsening the perception of violence. Zhao and coauthors (2018) described nurses’ overall experience as negative, with feelings of unpreparedness, frustration, moral distress, and powerlessness. Increasing awareness and staff acknowledgment that these behaviors are considered workplace violence have been shown to increase reporting, leader involvement, and job satisfaction (Duan et al., 2019). Raising awareness through training, prevention and intervention strategies, and leader support helps nurses address violent situations (Arnetz et al., 2017).

Caring for patients and visitors who display escalated behavior in non-IPU or non-ED settings can become arduous if skills and resources to address this behavior are inadequate. Behavioral Emergency Response Teams (BERTs) have effectively supported nursing staff faced with patients who exhibit violent behaviors. Use of BERTs can decrease assaults and restraint usage while increasing nurse confidence (Zicko et al., 2017). Additionally, these teams can reduce negative visitor behavior and prevent escalation, further ensuring staff safety.

Bean (2018) suggested promoting a safe workplace is everyone’s responsibility and highlighted the need for patients and families to behave in a respectful, non-violent manner. Nurses should report incidents and not accept violence as part of the job. Employers should value and invest in an organization-wide culture of safety and adhere to requirements to ensure workplace safety. Health authorities and government should enforce policies and procedures to prevent workplace violence (Havaei et al., 2019).

Patients need personalized care and meaningful activities to minimize triggers for agitation and aggression, and reliance on psychotropic medications should be reduced (Choi et al., 2019). Visible support from leaders and experts in the field and increased nurse knowledge to manage negative and abusive behavior reduce severity and frequency of assaults while increasing staff satisfaction (Zicko et al., 2017). Among benefits of a BERT identified by Zicko and coauthors are the timely consultation and intervention often needed when disruptions from negative behaviors occur. This support includes deescalating the situation to avoid violent behaviors, being a positive role model for crisis intervention skills, promoting staff confidence in responding to similar concerns in the future, providing post-incident debriefing, and offering education. Early de-escalation of negative behavior can reduce the need for restraints, also improving patient outcomes.

Identifying High-Risk Patients

Although staff education alone is not effective, it may have merit when used as part of a multicomponent approach to patient violence. The first step to prevent escalation of negative behaviors is early identification using a reliable risk assessment procedure. Behaviors may result from boredom or a need for sensory stimulation or relaxation (Mileski et al., 2018). Consideration of physical restraint use also could be a trigger for referral to a BERT; physical restraints typically are applied to manage impulsive behaviors and psychological symptoms (Foebel et al., 2016). With increased awareness of the potential for individual patients to display negative behaviors, nurses have the opportunity to plan and implement prevention strategies (Moursel et al., 2019).

When violence does occur, nurses are the first to try to control the situation, evaluate current interventions, and develop management strategies that ideally avoid physical restraints and minimize unnecessary use of antipsychotics (Bellenger et al., 2019). They play a vital role in monitoring and identifying risky behaviors to prevent crisis. In the demanding environment of an inpatient unit, the process of screening for behaviors likely to precede violence must be quick, reliable, and completed efficiently.

Negative behaviors that escalate to psychiatric and behavioral crises on medical-surgical units pose a major challenge (Bean, 2018). At this point, the patient requires complex, time- and resource-intensive care. Interventions must be appropriate to manage concomitant psychiatric and medical problems, as the risks of poor health and quality outcomes are increased greatly (Danis, 2019; Mackay, 2017). When hospitalized patients exhibit psychiatric and behavioral crisis-level behaviors, there is associated risk for longer lengths of stay, increased hospital cost, patient and staff injuries, nosocomial infections, and restraint use (Beeber, 2018). Restraint use also can lead to further functional decline, poor circulation, cardiac stress, incontinence, muscle weakness, injuries, skin impairment, and depression. Restraint use is associated with escalating psychiatric or behavioral crises and other harmful patient trajectories on medical and surgical units (Choi et al., 2019).

Behavior Checklist

The Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC) is one of the most studied violence risk assessments in the literature (Partridge & Affleck, 2018). The BVC was developed in China in response to an increase in violent behavior toward nurses. Its use increased awareness and helped to predict possible violence. The ease and quickness of use provide a feasible option for nurses to evaluate risks.

The most frequent behavioral changes leading to violent incidents – confusion, irritability, boisterousness, physical threats, verbal threats, and attacks on objects – were included in the BVC (Ghosh et al., 2019). These frequent behaviors are scored on a scale. A score of 0 means the selected behavior was not present, while a score of 1 means present. Each score then is summed to determine a composite score. The BVC composite score indicates the level of behavior severity (0–1 = small risk; 2 = moderate risk; 3–4 = high risk, 5–6 = very high risk). Total score of 2–6 suggests potential for violent behavior and should place staff on alert for threatening behavior (Ghosh et al., 2019).

Behavioral Emergency Response Teams

The concept of the BERT comes from many theories, as the intended outcome is for nursing staff to gain confidence in caring for patients who demonstrate escalated behaviors and to experience increased support from expert staff and leaders, with improved patient outcomes and staff and patient safety (Alexander et al., 2016; Arnetz et al., 2017). Based on Peplau’s Theory of Interpersonal Relations, using the BVC and implementing a BERT should benefit patients and nursing staff (Alexander et al., 2016). Successful de-escalation of negative behavior also would occur through the use of less restrictive methods.

Five operational attributes for BERT success include clearly defined parameters and processes, provision of clinical expertise and knowledge translation activities, person centered philosophy, relationship-oriented approach to stakeholders, and generalizable and sustainable outcomes (Westera et al., 2019). Similar to using a Rapid Response Team (RRT), nurses would follow defined criteria and protocols, dispatching BERTs with a telephone call or page (see Table 1). Experts, such as psychiatric or specially trained nurses, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and hospitalists, are notified and quickly respond to the alert. These experts then assess, communicate, and collaborate to stabilize the patient and determine if more intensive care is required. Mobile behavioral crisis intervention teams have demonstrated improvements in mental health state, reduction in frequency and severity of behaviors, and increased patient and caregiver satisfaction regarding care received (Murphy et al., 2015; Westera et al., 2019).

TABLE 1.

Potential Activation Criteria

|

Source: Zicko et al., 2017

Scores greater than 3 on the BVC indicate an increasing chance of violent behavior. Negative or violent behavior as defined by nursing assessment and the BVC identifies the issue and triggers activation of the BERT (Mackay, 2017). When situations result in BERT activation, further investigation to determine opportunities for process improvement should be conducted. This inspection may include chart and incident report review and interviews with staff to determine where processes might be improved. Incorporating the BVC with incident reporting systems aids in promoting the need for intervention, including participant screening, to prevent behavioral escalation (Moursel et al., 2019). Report from in-house security indicating the number of calls for assistance in de-escalating patient behaviors also may be helpful. Evaluating these incidents will serve as a method of validating the effectiveness of BERTs to identify triggers and behavioral patterns, and facilitate design and implementation of strategies to assist with preventing future behavioral escalation (Hutton et al., 2018). When hospitals have behavioral response teams in place, sharing information regarding BERT implementation may assist nurses with developing skills and increasing confidence to address similar future situations (Hutton et al., 2018).

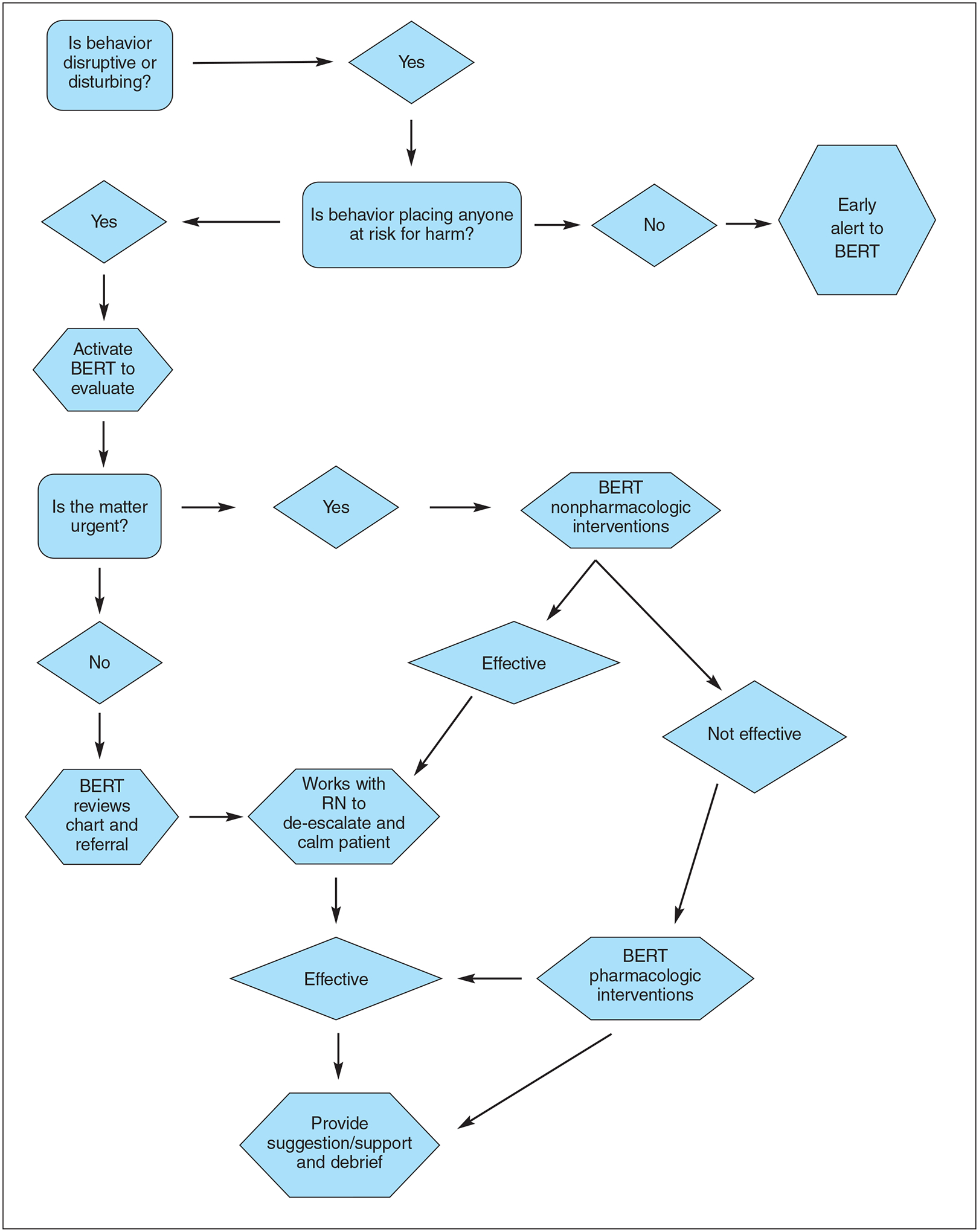

Recruitment of BERT members may prove to be a challenge due to the additional workload and staff time away from the psychiatric unit; additional funding also may be needed for staff who respond as members of the BERT (Choi et al., 2019). In the likelihood that a BERT functions similarly to an RRT, a responder for a particular shift would be needed to assist unit staff with support and respond to calls as required. Location and expectations of the response team would need to be identified initially to ensure all involved are respected, not just for their expertise but also for their time. Using an algorithm to determine need for BERT activation should decrease unnecessary calls (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Behavioral Emergency Response Team (BERT) Process Map

Implementation of BERTs can decrease restraint use, workplace violence, and calls for security, and improve staff confidence in identifying, managing, and de-escalating behavioral symptoms (Zicko et al., 2017). These teams also can increase staff, visitor, and patient safety; improve patient outcomes; increase the perception of leaders’ support for staff; and create an opportunity for staff to recognize potential negative and violent behaviors and establish positive relationships. Several authors have described successful implementation on medical and surgical units, with units often selected due to high census of patients with comorbid mental health conditions and increased staff requests for assistance (Bailey, 2018; Parker et al., 2020; Zicko et al., 2017). Creating a debriefing tool also may facilitate discussions of the incident and improve processes.

Zicko and coauthors (2017) used an anonymous pre/post survey to evaluate participants’ knowledge and perception of emergency response activation processes, confidence using behavioral de-escalation techniques and available resources, and intervention effectiveness. The survey also evaluated perceived support in caring for patients with psychiatric diagnoses or exhibiting disruptive or threatening behavior. Results indicated participants’ knowledge increased. Those who were once fearful of potentially violent patients not only gained knowledge but also reported increased confidence in their ability to manage such incidents. In the first 5 months after implementing a behavioral emergency response team, authors identified an 83% reduction in the number of assaults and an 80% reduction in restraint use. Post-survey results also reflected a statistically significant increase in perceived level of support. Authors suggested BERTs should be evaluated based on their impact on staff and patient safety (restraints, security interventions, assaults/injuries) and frequency of calls. Implementation studies have shown a significant decrease in restraint use, security intervention, and assaults on staff (Bailey, 2018, Parker et al., 2020; Zicko et al., 2017).

Nursing Implications

Use of the BERT is intended to de-escalate negative behaviors safely by using skilled experts, such as a psychiatric nurse, psychiatrist, pharmacist, and hospital security or police. Leader support is critical to program success. An algorithm should be used to assist non-ED, non-IPU nurses in determining when to alert the BERT. Use of specialized assessment (e.g., BVT) may alert staff of the potential for violence. Incorporating the BVC in incident reporting systems aids in identifying the need for an intervention to prevent behavioral escalation (participant screening) (Tommasini et al., 2020). Skilled communication should decrease the frequency and severity of negative behaviors (Zicko et al., 2017). Practical goals would be to reduce use of restraints; number of patients requiring transfer to an IPU; number of visitors who need to be trespassed; and injuries to patients, visitors, and staff. Nurses in non-ED and non-IPU areas should become more confident when addressing negative behaviors, thus decreasing the frequency of escalating violence (Havaei et al., 2019).

Investigation after BERT activation may include a review of patient records and incident reports, as well as interviews with staff to determine process improvement opportunities (see Table 2). Evaluating these incidents also validates effectiveness of the BERT to identify triggers and behavioral patterns (Ghosh et al., 2019). Implementation of the BERT is likely to improve communication, redirection and reorientation, and if necessary, discontinuation of the behavior using medication or physical restraints (Bellenger et al., 2019). Ultimately, staff should gain greater confidence in the care provided to patients exhibiting negative and violent behaviors.

TABLE 2.

Suggested Outcome Parameters

|

BERT = Behavioral Emergency Response Team

Source: Zicko et al., 2017

The BERT should function similarly to an RRT for medically unstable patients requiring additional assessment and medical management unavailable outside intensive care units (Choi et al., 2019; Danis, 2019). Implementation of the BVC combined with a BERT should provide readily apparent success in improving staff, visitor, and patient safety and increasing positive patient outcomes. Staff satisfaction and perceived support also should occur (Bailey et al., 2018; Parker et al., 2020; Zicko et al., 2017).

Conclusion

Nurses often need to address negative or violent behaviors from patients and visitors in acute care settings (Zhao et al., 2018). These experiences contribute to an unhealthy, unsafe work environment and job dissatisfaction (Zicko et al., 2017). Having a routine process for assessing patient risk for violence is essential for addressing staff, patient, and visitor safety on inpatient nursing units (Wray, 2018). Use of a standardized assessment tool (e.g., BVC) and expert resources can reduce the frequency of negative behavior escalation to violence and injury (Moursel et al., 2019).

Contributor Information

Deborah Dahnke, Duke University Hospital, Durham, NC..

Malissa A. Mulkey, University of North Carolina-REX Hospital, Raleigh, NC; and Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, IN..

REFERENCES

- Alexander V, Ellis H, & Barrett B (2016). Medical-surgical nurses’ perceptions of psychiatric patients: A review of the literature with clinical and practice applications. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 30(2), 262–270. 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Hospital Association. (2018). Cost of community violence to hospitals and health systems. https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-01/community-violence-report.pdf

- Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Russell J, Upfal MJ, Luborsky M, Janisse J, & Essenmacher L (2017). Preventing patient-to-worker violence in hospitals: Outcome of a randomized controlled intervention. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 59(1),18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey K, Paquet SR, Ray BR, Grommon E, Lowder EM, & Sightes E (2018). Barriers and facilitators to implementing an urban co-responding police-mental health team. Health & Justice, 6(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean LS (2018). Violence in the workplace: We aren’t OK. Health Progress, 99(6), 53–55. https://www.chausa.org/publications/health-progress/article/november-december-2018/violence-in-the-workplace-we-aren%27t-ok [Google Scholar]

- Beeber LS (2018). Disentangling mental illness and violence. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 24(4), 360–362. 10.1177/1078390318783729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellenger EN, Ibrahim JE, Kennedy B, & Bugeja L (2019). Prevention of physical restraint use among nursing home residents in Australia: The top three recommendations from experts and stakeholders. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 14(1), e12218. 10.1111/opn.12218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KR, Omery AK, & Watkins AM (2019). An integrative literature review of psychiatric rapid response teams and their implementation for de-escalating behavioral crises in nonpsychiatric hospital settings. Journal of Nursing Adminstration, 49(6), 297–302. 10.1097/nna.0000000000000756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis C (2019). The role of rapid response nurses in improving patient safety. ProQuest Dissertations Publi shing. [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente M, Schoenfisch A, Wadsworth B, & Foresman-Capuzzi J (2019). Impact of behavior management training on nurses’ confidence in managing patient aggression. Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(2) 73–78 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Ni X, Shi L, Zhang L, Ye Y, Mu H, … Wang Y (2019). The impact of workplace violence on job satisfaction, job burnout, and turnover intention: The mediating role of social support. Health & Quality of Life Outcomes, 17. 10.1186/s12955-019-1164-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foebel AD, Onder G, Finne-Soveri H, Lukas A, Denkinger MD, Carfi A, … Liperoti R (2016). Physical restraint and antipsychotic medication use among nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of the American Medical Direct ors Association, 17(2), 189.e9–14. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M, Twigg D, Kutzer Y, Towell-Barnard A, De Jong G, & Dodds M (2019). The validity and utility of violence risk assessment tools to predict patient violence in acute care settings: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(6), 1248–1267. 10.1111/inm.12645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaei F, MacPhee M, & Lee SE (2019). The effect of violence prevention strategies on perceptions of workplace safety: A study of medical-surgical and mental health nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(8), 1657–1666. 10.1111/jan.13950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton SA, Vance K, Burgard J, Grace S, & Van Male L (2018). Workplace violence prevention standardization using lean principles across a healthcare network. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 31(6), 464–473. 10.1108/IJHCQA-05-2017-0085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane S, & Cunningham C (2017). The need for holistic management of behavioral disturbances in dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(7), 1055–1058. 10.1017/S1041610217000503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay A (2017). The critical role of the psychiatric emergency response team in the adoption of a violence risk assessment tool. ProQuest Dissertat ions Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Mileski M, Baar Topinka J, Brooks M, Lonidier C, Linker K,, & Vander Veen K, (2018). Sensory and memory stimulation as a means to care for individuals with dementia in long-term care facilities. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 13, 967–974. 10.2147/CIA.S153113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moursel G, Cetinkaya Duman Z, & Almvik R (2019). Assessing the risk of violence in a psychiatric clinic: The Broset Violence Checklist (BVC) Turkish version-validity and reliability study. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 55(2), 225–232. 10.1111/ppc.12338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey MA & Munro CL (2021). Calming the agitated patient: Providing strategies to support clinicians. MEDSURG Nurs ing, 30(1), 9–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Irving CB, Adams CE, & Waqar M (2015). Crisis intervention for people with severe mental illnesses. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12. 10.1002/14651858.CD001087.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker CB, Calhoun A, Wong AH, Davidson L, & Dike C (2020). A call for behavioral emergency response teams in inpatient hospital settings. AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(11), 956–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge B, & Affleck J (2018). Predicting aggressive patient behaviour in a hospital emergency department: An empirical study of security officers using the Broset Violence Checklist. Australias Emergency Care, 21(1), 31–35. 10.1016/j.auec.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekurinen V, Willman L, Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, & Välimäki M (2017). Patient aggression and the well-being of nurses: A cross-sectional survey study in psychiatric and non-psychiatric settings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(10), 1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommasini N, Laird K, Cunningham P, & Ogbejesi V (2020). Building a successful behavioral emergency support team. https://www.myamericannurse.com/building-a-successful-behavioral-emergency-support-team/#

- Westera A, Fildes D, Grootemaat P, & Gordon R (2019). Rapid response teams to support dementia care in Australian aged care homes: Review of the evidence. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 39(3), 178–192. 10.1111/ajag.12745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray K (2018). The American Organization of Nurse Executives and American Hospital Association initiatives work to combat violence. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(10, Suppl.), S3–S5. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao SH, Shi Y, Sun ZN, Xie FZ, Wang JH, Zhang SE,…Fan LH (2018). Impact of workplace violence against nurses’ thriving at work, job satisfaction and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27 (13–14), 2620–2632. 10.1111/jocn.14311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zicko JM, Schroeder RA, Byers WS, Taylor AM, & Spence DL (2017). Behavioral emergency response team: Implementation improves patient safety, staff safety, and staff collaboration. Worldviews on Evidence Based Nursing, 14(5), 377–384. 10.1111/wvn.12225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]