Oxaliplatin administration induces long-lasting hyperalgesic priming, an effect mediated, at least in part, through nociceptor Gαi1 and Gαo, as well as protein kinase Cɛ.

Keywords: Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, CIPN, Oxaliplatin, Stress, Hyperalgesic priming, Gi/o-GPCR subtypes

Abstract

Stress plays a major role in the symptom burden of oncology patients and can exacerbate cancer chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), a major adverse effect of many classes of chemotherapy. We explored the role of stress in the persistent phase of the pain induced by oxaliplatin. Oxaliplatin induced hyperalgesic priming, a model of the transition to chronic pain, as indicated by prolongation of hyperalgesia produced by prostaglandin E2, in male rats, which was markedly attenuated in adrenalectomized rats. A neonatal handling protocol that induces stress resilience in adult rats prevented oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming. To elucidate the role of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal and sympathoadrenal neuroendocrine stress axes in oxaliplatin CIPN, we used intrathecally administered antisense oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) directed against mRNA for receptors mediating the effects of catecholamines and glucocorticoids, and their second messengers, to reduce their expression in nociceptors. Although oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming was attenuated by intrathecal administration of β2-adrenergic and glucocorticoid receptor antisense ODNs, oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was only attenuated by β2-adrenergic receptor antisense. Administration of pertussis toxin, a nonselective inhibitor of Gαi/o proteins, attenuated hyperalgesic priming. Antisense ODNs for Gαi1 and Gαo also attenuated hyperalgesic priming. Furthermore, antisense for protein kinase C epsilon, a second messenger involved in type I hyperalgesic priming, also attenuated oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming. Inhibitors of second messengers involved in the maintenance of type I (cordycepin) and type II (SSU6656 and U0126) hyperalgesic priming both attenuated hyperalgesic priming. These experiments support a role for neuroendocrine stress axes in hyperalgesic priming, in male rats with oxaliplatin CIPN.

1. Introduction

Pain caused by bodily insults such as infection, surgery, or chemotherapy diminishes as the underlying condition resolves and injured tissue heals or chemotherapy treatment is completed. However, in a number of these patients, a transition occurs from acute to chronic pain.16,65 In patients receiving cancer chemotherapy, ∼25 to 30% experience chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), with pain persisting for months or years after discontinuation of treatment,17,63 indicating that chemotherapy can produce long-lasting adverse alterations in pain pathways.

Stressful life events influence a variety of diseases through activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) and sympathoadrenal neuroendocrine stress axes.85 Repeated environmental stressors, especially when unpredictable, induce persistent hyperalgesic states, including hyperalgesic priming, a preclinical model of the transition from acute to chronic pain.4,26,31,35,41,45,79 We and others have demonstrated, in preclinical26,79 and clinical54,55,57,74 studies, the impact of stress and role of the neuroendocrine stress axes in CIPN pain. We have shown that rats exposed to unpredictable sound stress, using an experimental protocol that produces a chronic increase in plasma epinephrine and corticosterone,40,41 develop hyperalgesic priming,23,40 a neuroplastic change in nociceptors that markedly prolongs hyperalgesia produced by inflammatory mediators, prototypically prostaglandin E2 (PGE2),38 by a PKCɛ-dependent mechanism.40 We have also shown that the stress-induced neuroplasticity underlying hyperalgesic priming requires concerted action of glucocorticoids and catecholamines, acting at their cognate receptor, on nociceptors, to produce a switch in coupling of receptor G-protein signaling from Gs to Gi.23 Given the marked impact of stress on oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia79 and on nociceptor neuroplasticity,23,40,41,49 in this study, we evaluated the role of stress in hyperalgesic priming induced by oxaliplatin, including evaluation of the contribution of Gαi/o subunits, Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, and Gαo, and a second messenger involved in hyperalgesic priming, PKCε.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental animals

Experiments were performed on 230- to 430-g male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Hollister, CA). Animals were housed in a controlled environment in the animal care facility at the University of California, San Francisco, under a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with food and water available ad libitum. Experimental protocols, approved by the UCSF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, adhered to the guidelines of the American Association of Laboratory Animal Care, the National Institutes of Health, and the Committee for Research and Ethical Issues of the International Association for the Study of Pain, for the use of animals in research. In the design of experiments, a concerted effort was made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. Because of the marked sexual dimorphism in the second messenger mechanisms of hyperalgesic priming,29,36,42 the additional extensive parallel experiments will be performed in female rats in a separate study.

2.2. Mechanical nociceptive threshold testing

Mechanical nociceptive threshold was quantified using an Ugo Basile Analgesy-meter (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL), which applies a linearly increasing mechanical force to the dorsum of a rat's hind paw, as described previously.83 Rats were placed in cylindrical acrylic restrainers designed to provide ventilation and allow for hind leg extension through lateral ports, for the assessment of nociceptive threshold, with minimal stress. To acclimatize rats to the testing procedure, they were placed in restrainers for ∼40 minutes before starting each training session (3 consecutive days of training) and for ∼30 minutes before experimental manipulations. Nociceptive threshold was defined as the force, in grams, at which a rat withdrew its paw. Baseline nociceptive threshold was determined from the mean of 3 readings obtained before injections of test agents. Each experiment was performed on a different group of rats, and only 1 paw per rat was used in each experiment.

2.3. Drugs

The following compounds were used in the present experiments: oxaliplatin, cordycepin 5′-triphosphate sodium salt (protein translation inhibitor), SU6656 (Src family kinase inhibitor), U0126 (MAPK/ERK inhibitor), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, direct-acting nociceptor-sensitizing agent commonly used to probe for the presence of hyperalgesic priming33,36,60), corticosterone, epinephrine bitartrate, and pertussis toxin (nonselective Gαi/o-protein inhibitor), purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The stock solution of PGE2 was prepared in 100% ethanol (1 μg/μL), and dilutions were made with physiological saline (0.9% NaCl) to produce the concentration used in experiments (100-ng PGE2/5 μL; 2% final ethanol concentration). All other drugs were dissolved in 100% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) and further diluted in saline containing 2% Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich). For all experiments, the final concentrations of DMSO and Tween 80 were 2%. All drugs were injected intradermally on the dorsum of 1 hind paw, in a volume of 5 μL, using a 30-gauge hypodermic needle adapted to a 50-μL Hamilton syringe (Reno, NV). To avoid mixing of distilled water and experimental drugs in the syringe, the injection of cordycepin, SU6656, U0126, and pertussis toxin was preceded by a hypotonic shock (2 μL of distilled water, separated in the syringe by a bubble of air) to facilitate entry of membrane-impermeable compounds into the nerve terminal. Dose selection was based on previous studies that established effectiveness at their targets when injected intradermally on the dorsum of the hind paw.3,8,22,23

2.4. Oxaliplatin chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy hyperalgesic priming

Oxaliplatin was administered (2 mg/kg dissolved in 0.9% saline, 1 mL/kg) through a tail vein. To evaluate for the presence and time course of hyperalgesic priming, on days 21, 42, and 60 after oxaliplatin administration, hyperalgesia induced by PGE2 (100 ng/5 μL, i.d.) was evaluated; PGE2 hyperalgesia >4 hours indicates the presence of hyperalgesic priming.62

2.5. Surgical adrenalectomy

Under 3% isoflurane anesthesia, rats underwent bilateral excision of their adrenal gland (adrenalectomy), which removes both the medulla and cortex. After shaving their abdomen, anesthetized rats were placed on a thermal blanket, and their skin was swabbed with povidone-iodine solution in the area of the surgical field. To provide perioperative analgesia, rats were given meloxicam subcutaneously (5 mg/kg, s.c.), and bupivacaine was infiltrated into the skin preoperatively, in the area to be incised (5-8 mg/kg, i.d.). In each rat, bilateral flank wall incisions were made, and adrenal glands were visualized and excised; 5-0 silk suture was used to separately close the abdominal wall and skin incisions. Sham adrenalectomy, in which the adrenal glands were located and manipulated, but not excised, was performed in control rats.

2.6. Stress hormone replacement in adrenalectomized rats

To maintain basal levels of plasma corticosterone during the experimental period (∼25 days), adrenalectomized rats were supplied with corticosterone (25 µg/mL) and 0.45% saline in their drinking water (ad libitum) starting at the time of their adrenalectomy surgery. This stress hormone-replacement protocol simulates the phasic (circadian) corticosterone rhythm, normalizes basal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and catecholamine levels,44,79 and prevents the weight loss observed in adrenalectomized rats that did not receive corticosterone replacement.1 To replace both hormones at levels observed in stressed rats, Alzet osmotic minipumps (Durect Corp, Cupertino, CA) delivered epinephrine at a rate of 5.4 μg/0.25 μL/hour, which produces plasma levels of 720 pg/mL in rats,82 and corticosterone was administered by a slow-release pellet, 100 mg of fused corticosterone, which produces a plasma corticosterone level of 32.6 mg⁄dL.81 Pumps and slow-release pellets, implanted subcutaneously in the interscapular region, delivered stress hormones over a period of 28 days. Oxaliplatin (2 mg/kg, i.v.) was injected 1 day after rats were submitted to adrenalectomy and hormone implants.

2.7. Receptor and second messenger antisense treatment

To investigate the role of the β2-adrenergic receptor, glucocorticoid receptor, PKCε, Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, and Gαo in hyperalgesic priming induced by systemic administration of oxaliplatin, antisense (AS) and mismatch (MM), or sense (SE) (for Gαi/o proteins) oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) were administered intrathecally for 3 consecutive days. This procedure produces not only reversible inhibition of the expression of the relevant proteins in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons but also modulation of nociceptive behavior.80 Immediately before their intrathecal administration, antisense and sense ODNs were lyophilized and reconstituted to a concentration of 6 μg/μL in 0.9% saline. To administer ODNs (120 μg/20 µL), rats were briefly anaesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane and a 30-gauge hypodermic needle inserted into the subarachnoid space, on the midline, between the L4 and L5 vertebrae. The intrathecal site of injection was confirmed by the elicitation of a tail flick, a reflex that is evoked by subarachnoid space access and bolus injection.53 The efficacy of this robust and reproducible method for intrathecal ODN administration53,76 is enhanced by a direct communication between the subarachnoid space and DRG in rats,39 facilitating access of ODNs to DRG cell bodies,46 as well as to central terminals of nociceptors. Antisense/mismatch/sense ODNs, synthesized by Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA), were validated in previous studies. Oligodeoxynucleotide antisense sequences (5′-3′) were

β2-adrenergic receptor antisense: AAA GGC AGA AGG ATG TGC; mismatch sequence: ATA GCC TGA TGG AAG TCC.21

Glucocorticoid receptor antisense: TGG AGT CCA TTG GCA AAT; mismatch sequence: TGA AGT TCA GTG TCA ACT.21

PKCε antisense: GCC AGC TCG ATC TTG CGC CC; mismatch sequence: GCC AGC GCG ATC TTT CGC CC.61

Gαi1 antisense: AGA CCA CTG CTT TGT A; sense sequence: GGG GGA AGT AGG TCT TGG.6,32,70,75,78,86

Gαi2 antisense: CTT GTC GAT CAT CTT AGA; sense sequence: GGG GGA AGT AGG TCT TGG.32,70,75,78,86

Gαi3 antisense: AAG TTG CGG TCG ATC AT; sense sequence: GGG GGA AGT AGG TCT TGG.32,70,75,78,86

Gαo antisense: CGC CTT GCT CCG CTC; sense sequence: GGG GGA AGT AGG TCT TGG.32,70,75,78,86

2.8. Stress resilience induced by neonatal handling

To produce stress resilience in adult rats, we used a well-established model, neonatal handling.48,52 This protocol involves removing dams from their litters, daily from postnatal day 2 to 9, and gently handling, touching, and stroking pups for 15 minutes, after which litters were returned to the care of their dams, in their home cages. On postnatal day 21, pups were weaned, and females were culled. Male rats were housed 3 per cage to be used in experiments as adults.

2.9. Data analysis

In all experiments, the dependent variable was mean change in mechanical nociceptive paw-withdrawal threshold, expressed as percentage change from preintervention baseline. As specified in figure legends, the Student t test, or 1- or 2-way repeated-measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc test, was performed to compare the magnitude of the hyperalgesia induced by oxaliplatin in the different groups or to compare the effect produced by different treatments on the prolongation of PGE2-induced hyperalgesia (evaluated 4 hours after injection) with the duration of PGE2 hyperalgesia in control groups. Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA) was used for the graphics and to perform statistical analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

3. Results

3.1. Oxaliplatin induces persistent hyperalgesic priming

To evaluate the role of stress in oxaliplatin CIPN, we first characterized 2 key features of CIPN pain, lowered mechanical nociceptive threshold (ie, hyperalgesia) and hyperalgesic priming (ie, prolongation of PGE2-induced hyperalgesia), in male rats.

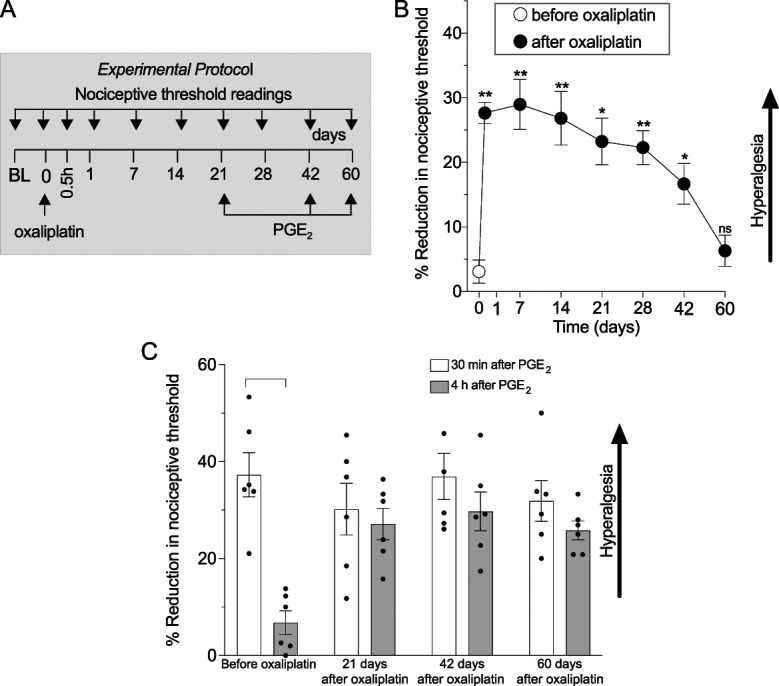

When compared with the effect of vehicle (saline), oxaliplatin (a single injection of 2 mg/kg/i.v., day 0) produced a time-dependent decrease in mechanical nociceptive threshold (hyperalgesia) peaking 7 days after administration (∼30% decrease in mechanical nociceptive threshold) (Figs. 1A and B). This mechanical hyperalgesia was relatively stable for 28 days and was still present 42 days after administration of oxaliplatin.

Figure 1.

Oxaliplatin induces long-lasting mechanical hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming in male rats. Male rats received a single intravenous injection of vehicle (0.9% saline) or oxaliplatin (2 mg/kg), and mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated before their administration (day 0) and on days 1, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42, and 60 after administration. Oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming was evaluated on days 21, 42, and 60. (A) The experimental protocol, with timing of treatments and nociceptive threshold measurements. (B) Oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia that lasted 42 days; *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (C) PGE2 (100 ng/5 μL, i.d.) was injected on the dorsum of 1 hind paw, and the mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated 30 minutes and 4 hours later to test for hyperalgesic priming. Hyperalgesic priming was evaluated before oxaliplatin and again 21, 42, and 60 days after oxaliplatin administration. PGE2-induced hyperalgesia at 30 minutes, and before administration of oxaliplatin, PGE2-induced hyperalgesia was no longer present at the fourth hour (30 minutes vs 4 hours, P = 0.0005, Student paired 2-tailed t test, t5 = 8.134). However, after treatment with oxaliplatin, the hyperalgesia induced by PGE2 was still present at the fourth hour 21, 42, and 60 days after oxaliplatin (for each time point, 30 minutes vs 4 hours, P = NS). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

To test for the presence for hyperalgesic priming, PGE2 was injected intradermally, 21, 42, and 60 days after administration of oxaliplatin, and the mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated at the same site 30 minutes and 4 hours later. Hyperalgesia induced by PGE2 was prolonged, compared with preoxaliplatin treatment, at all 3 time points after administration (ie, 21, 42, and 60 days) of oxaliplatin (Fig. 1C), indicating the persistence of hyperalgesic priming unattenuated.7,28,36 Importantly, on day 60, at which time oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was no longer present, hyperalgesic priming remained unattenuated.

3.2. Adrenalectomy prevents oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming

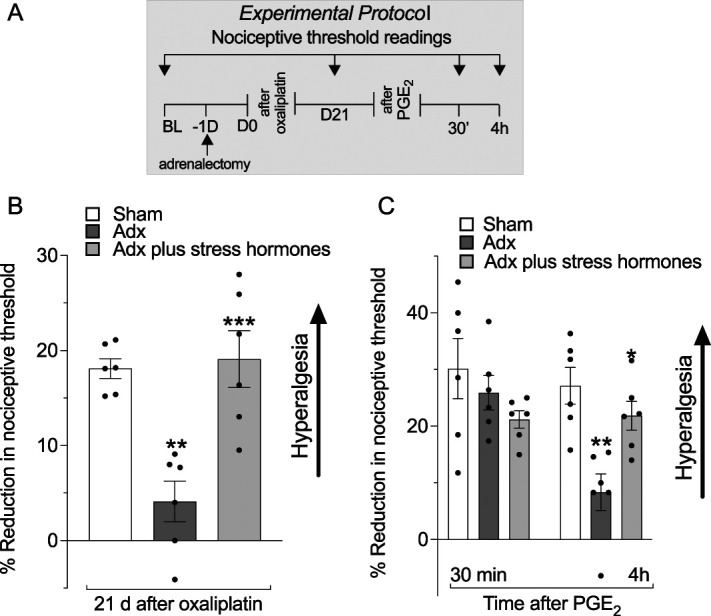

To evaluate the role of neuroendocrine stress axes in oxaliplatin CIPN chronic pain (hyperalgesic priming), we evaluated the impact of surgical adrenalectomy (Fig. 2A), which eliminates the final common pathway of the HPA (adrenal cortex) and sympathoadrenal (adrenal medulla) stress axes on hyperalgesic priming induced by oxaliplatin.

Figure 2.

Role of neuroendocrine stress axes in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and priming. Male rats were submitted to sham bilateral adrenalectomy (adrenal intact animals), bilateral adrenalectomy only, or bilateral adrenalectomy plus stress hormone (epinephrine and corticosterone) replacements. Mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated before oxaliplatin administration (day 0) and again on day 21 after oxaliplatin administration. On day 21, after measurement of mechanical threshold, PGE2 (100 ng/paw) was injected intradermally to assess for hyperalgesic priming (ie, prolongation of PGE2-induced hyperalgesia). Mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated 30 minutes and 4 hours after PGE2. (A) The experimental protocol, with timing of treatments and nociceptive threshold measurements. (B) When the magnitude of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was evaluated on day 21, it was markedly attenuated in the oxaliplatin-treated adrenalectomized rats, compared with the adrenal intact group. However, in the adrenalectomized rats replaced with stress hormones, oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was of similar magnitude to that observed in adrenal intact rats, supporting a contribution of stress hormones to oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, treatment F(2,15) = 14.45; **P < 0.01: sham adrenalectomy group vs adrenalectomy group, ***P < 0.001: adrenalectomy group vs adrenalectomy plus stress hormone replacement (n = 6, 1-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). (C) PGE2-induced hyperalgesia at 30 minutes, in all groups, that was no longer present at the fourth hour, in adrenalectomized rats. However, PGE2-induced hyperalgesia was still present 4 hours after its injection in the sham adrenalectomized group (adrenal intact animals) and in the adrenalectomized group that received replacement stress hormones, in support of a contribution of stress hormones to oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, treatment F(2,15) = 14.45; **P < 0.01: sham adrenalectomy group vs adrenalectomized group, ***P < 0.001: adrenalectomy group vs adrenalectomy plus stress hormone replacement (n = 6, 1-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM, time F(1,30) = 5.922; treatment F(2,30) = 6.024; interaction F(2,30) = 4.143, **P < 0.01: sham adrenalectomy group vs adrenalectomy group, *P < 0.05: adrenalectomized group vs adrenalectomy plus stress hormones group (n = 6 rats/group), 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. Adx, adrenalectomized; ANOVA, analysis of variance; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

As we have previously shown,79 oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia is markedly attenuated in adrenalectomized (Adx) rats evaluated 21 days after administration (Fig. 2B). We now show that in adrenalectomized rats receiving replacement of nonstress levels of corticosterone plus epinephrine, mechanical hyperalgesia was not statistically different from that seen in sham adrenalectomized rats (Fig. 2B). We also observed that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming was also absent in adrenalectomized rats because there was no prolongation of PGE2 hyperalgesia measured 4 hours after its administration. In adrenalectomized rats receiving replacement corticosterone and epinephrine to produce levels seen in stressed rats,79 oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming was reinstated (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that the hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming, the persistent form of CIPN pain, are strongly dependent on stress hormones at stress levels.

3.3. Contribution of nociceptor β2-adrenergic and glucocorticoid receptors to oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming

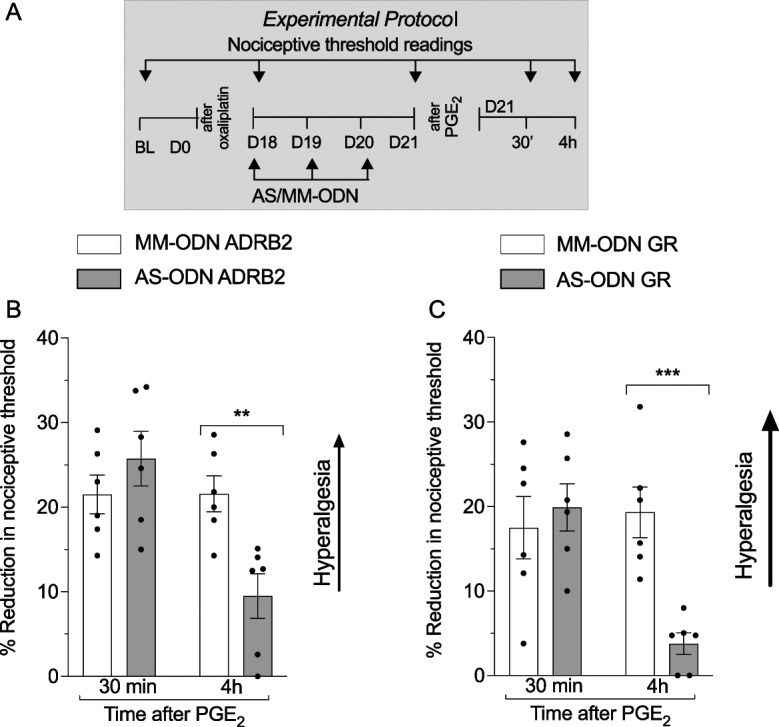

We have previously shown79 that male rats receiving intrathecal oligodeoxynucleotides antisense to glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and β2-adrenergic receptor (ADRB2) mRNA, to attenuate their level in nociceptors,21 both reversed oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia when measured on day 21. We now show that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming was also markedly attenuated in rats receiving AS-ODNs (80 μg/20 μL administered intrathecally daily for 3 days starting 18 days after administration of oxaliplatin) (Fig. 3A), against ADRB2 mRNA (Fig. 3B) or against GR (Fig. 3C). Thus, ongoing GR and ADRB2 signaling is essential to produce oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming.

Figure 3.

Role of the β2-adrenergic and glucocorticoid receptor in oxaliplatin-induced priming. Male rats received a single intravenous injection of oxaliplatin (2 mg/kg) on day 0, and starting on day 18, MM-ODNs or AS-ODNs (both 120 μg/20 μL, gray bar) to ADRB2 or GR mRNA were injected intrathecally for 3 consecutive days. On day 21 after administration of oxaliplatin, ∼17 hours after the last ODN injection, mechanical nociceptive threshold was measured, and PGE2 (100 ng/5 μL) was injected intradermally. Thirty minutes and 4 hours after injection of PGE2, the mechanical nociceptive threshold was again measured to assess for hyperalgesic priming. (A) The experimental protocol providing timing of treatments and nociceptive threshold measurements. (B) When the magnitude of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was evaluated on day 21, an inhibition in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia (t10 = 2.321, *P = 0.0427: ADRB2 AS-ODN–treated group vs ADRB2 MM-ODN–treated group, unpaired Student t test) and the prolongation of PGE2 hyperalgesia were observed in ADRB2 AS-ODN–treated group (time F(1,20) = 9.624; treatment F(1,20) = 2.274; interaction F(1,20) = 9.768, **P < 0.01: ADRB2 AS-ODN–treated group vs ADRB2 MM-ODN–treated group, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 rats/group). These findings support the suggestion that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming are β2-adrenergic receptor-dependent. (C) When the magnitude of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was evaluated on day 21, no differences between the GR AS-ODN–treated and MM-ODN–treated groups were observed (t10 = 1.794, P = 0.1100: GR AS-ODN–treated group vs GR MM-ODN–treated group, unpaired Student t test). However, an inhibition of the prolongation of PGE2-induced hyperalgesia was observed in the GR AS-ODN–treated group, when compared with the GR MM-ODN–treated group (time F(1,20) = 6.420; treatment F(1,20) = 5.427; interaction F(1,20) = 10.10, ***P < 0.002: GR AS-ODN–treated group vs GR MM-ODN–treated group, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 rats/group). These findings indicate that although oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia is glucocorticoid receptor-independent, in oxaliplatin-induced priming, this receptor plays a significant role. ADRB2, β2-adrenergic receptor; ANOVA, analysis of variance; AS, antisense; BL, antisense; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; ODN, oligodeoxynucleotide; ; MM, mismatch; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

3.4. Stress resilience prevents oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming

To further evaluate the contribution of the HPA and sympathoadrenal stress axes to oxaliplatin CIPN, neonatal rats were exposed to a protocol that produces resilience to stress in the adult30,50,67 (Fig. 4A). We have previously shown79 that neonatal handling (daily, on postnatal days 2-9), which produces a stress-resilience phenotype in adult rats,5 prevented oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia in 8-week-old (adult) rats. We now show that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming was also absent in neonatally handled adult rats because hyperalgesia was not present 4 hours after PGE2 administration (Fig. 4B). These data provide evidence that early life events associated with stress impact the chronification of oxaliplatin CIPN, as observed by a significant prevention in the induction of hyperalgesic priming.

Figure 4.

Neonatal handling-induced stress resilience attenuates oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming in adult rats. Male rats were submitted to neonatal handling and as adults received oxaliplatin. (A) The experimental protocol providing timing of treatments and nociceptive threshold measurements. (B) Neonatal handling prevented oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia, when compared with control adult rats that received oxaliplatinneonatal handling, oxaliplatin vs oxaliplatin, ****P<0.0001, Student unpaired 2-tailed t test, t=6.883, and a marked inhibition in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming. Data are shown as mean ± SEM neonatal handling, oxaliplatin vs oxaliplatin, at 4 h, **P<0.005, using 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test (n = 6 paws per group). ANOVA, analysis of variance; NH, neonatal handling (resilient); PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

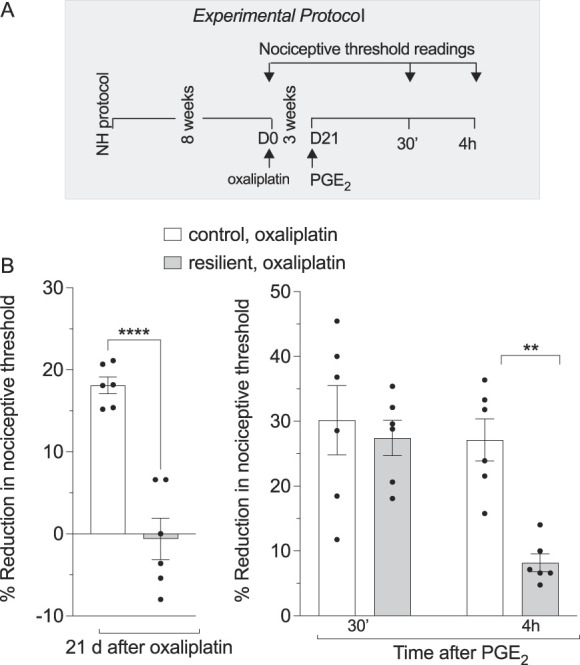

3.5. Role of G-protein αi/o subunits in hyperalgesic priming

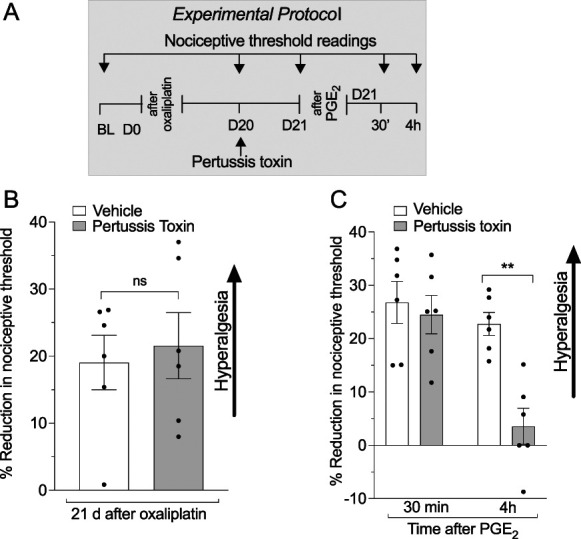

Given that the β2-adrenergic receptor can be coupled to multiple Gαi/o proteins13,51 that, in turn, signal through different second messengers, we initially evaluated the effect of pertussis toxin (PTX), which irreversibly inhibits all Gαi/o subunits, on oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming, administered 20 days after oxaliplatin. Although pertussis toxin had no effect on oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia (Figs. 5A and B), it completely reversed oxaliplatin-induced prolongation of PGE2 hyperalgesia (hyperalgesic priming) (Fig. 5C), suggesting the involvement of Gi proteins in the chronic form of oxaliplatin CIPN.

Figure 5.

Role of GPCR Gi/o subunits in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming. Male rats received a single intravenous injection of oxaliplatin (2 mg/kg), and the mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated before oxaliplatin administration (day 0) and again on day 20 after its administration. On day 20, after measurement of mechanical nociceptive threshold, vehicle (saline) or pertussis toxin, which inactivates diverse Gαi/o subunits, was injected intradermally (1 µg/5 µL). On day 21, ∼17 hours after pertussis toxin injection, mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated, and PGE2 (100 ng/paw) was then injected intradermally. In these experiments, mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated 30 minutes and 4 hours after injection of PGE2 to assess for hyperalgesic priming. (A) The experimental protocol providing timing of treatments and nociceptive threshold measurements. (B) When the magnitude of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was evaluated on day 21, no difference between the pertussis toxin–treated and vehicle-treated groups was observed (t10 = 0.3922, P = 0.6817: pertussis toxin–treated group vs vehicle-treated group, unpaired Student t test). (C) However, inhibition of the prolongation of PGE2 was observed in the pertussis toxin–treated group, when compared with the vehicle-treated group (time F(1,20) = 14; treatment F(1,20) = 10.38; interaction F(1,20) = 6.415, **P < 0.01: for pertussis toxin–treated group vs vehicle-treated group, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 rats/group). These findings indicate that although oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia is Gαi/o-GPCR subunit-independent, they contribute to oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming. ANOVA, analysis of variance; BL, baseline; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; Gα/o, G-protein subunit α/o; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

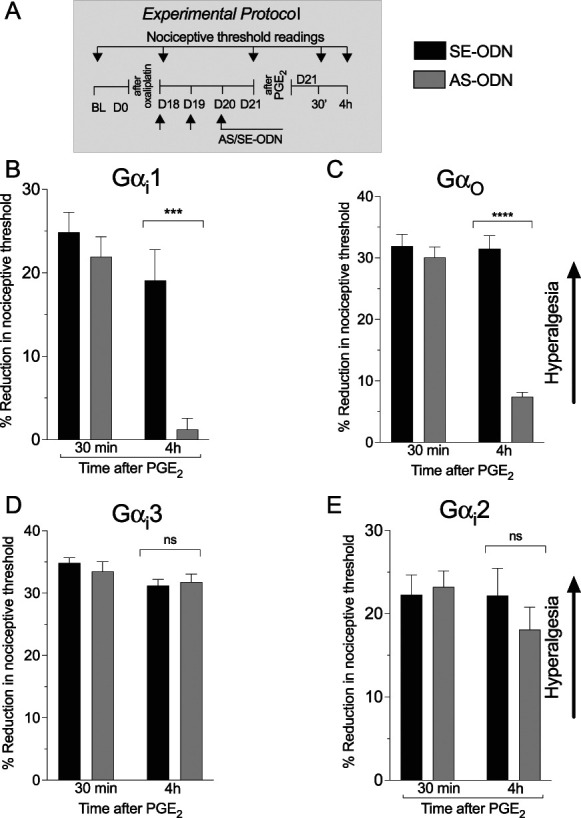

To evaluate the role of individual Gαi/o subunits in oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesic priming, we used intrathecal administration of oligodeoxynucleotides antisense to Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, or Gαo mRNA to selectively attenuate each Gαi/o subunit. Rats were treated intrathecally with AS-ODN or SE-ODN to Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, or Gαo mRNA, daily for 3 days, beginning 18 days after oxaliplatin administration (Fig. 6A). On, day 21, ∼17 hours after the third injection of ODNs, PGE2 was injected intradermally, and the mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated, at the injection site, 30 minutes and 4 hours later. Hyperalgesic priming (ie, PGE2 hyperalgesia at the fourth hour) was absent in rats treated with Gαi1 (Fig. 6B) and Gαo (Fig. 6C) mRNA but was present in rats treated with ODN antisense to Gαi3 and Gαi2 mRNA (Figs. 6D and E). These data indicate that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming is Gαi1- and Gαo-dependent and Gαi3- or Gαi2-independent.

Figure 6.

Role of GPCR Gi/o subunits in oxaliplatin-induced priming. Male rats received a single intravenous injection of oxaliplatin (2 mg/kg), and on day 18 after its administration, SE-ODNs (120 μg/20 μL, black bar) or AS-ODNs (120 μg/20 μL, gray bar) against Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, or Gαo, mRNA was injected intrathecally for 3 consecutive days. On day 21, ∼17 hours after the last ODN injection, mechanical nociceptive threshold was measured, and then PGE2 (100 ng/5 μL) was injected intradermally. Thirty minutes and 4 hours after PGE2, the mechanical nociceptive threshold was again measured to assess for hyperalgesic priming. (A) The experimental protocol providing timing of treatments and nociceptive threshold measurements. (B) An inhibition of the prolongation of PGE2 effect was observed in the Gαi1 AS-ODN–treated group, when compared with the Gαi1 SE-ODN group (time F(1,20) = 26.36; treatment F(1,20) = 16.25; interaction F(1,20) = 8.369, **P < 0.01: Giα1 AS-ODN–treated group vs Gαi1 SE-ODN–treated group, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 rats/group). These findings indicate that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming is Gαi1-dependent. (C) An inhibition of the prolongation of PGE2 hyperalgesia was observed in the Goα AS-ODN–treated group, when compared with the Goα SE-ODN–treated group (time F(1,20) = 46.27; treatment F(1,20) = 58.32; interaction F(1,20) = 42.99, **P < 0.0001: Goα AS-ODN–treated group vs Gαo SE-ODN–treated group, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n= 6 rats/group). These findings indicate that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming is Gαo-dependent. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 rats/group). (D and E) The prolongation of PGE2 was present in both Gαi3 (C), Gαi2 (D) AS-ODNs, and their respective SE-ODN–treated groups, with no statistical differences between these 2 groups (C: time F(1,20) = 5.067; treatment F(1,20) = 0.1166; interaction F(1,20) = 0.6648, P = 0.4245 Gαi3 AS-ODN–treated group and SE-treated group; D: time F(1,20) = 1.024; treatment F(1,20) = 0.3675; interaction F(1,20) = 0.9293, P = 0.5601: Gαi2 AS-ODN–treated group and SE-treated group, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 rats/group). These findings support the suggestion that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming is Gαi3- and Gαi2-independent. ANOVA, analysis of variance; AS, antisense; BL, baseline; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; Gα/o, G-protein subunit α/o; ODN, oligodeoxynucleotide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

3.6. Oxaliplatin induces type I and type II priming

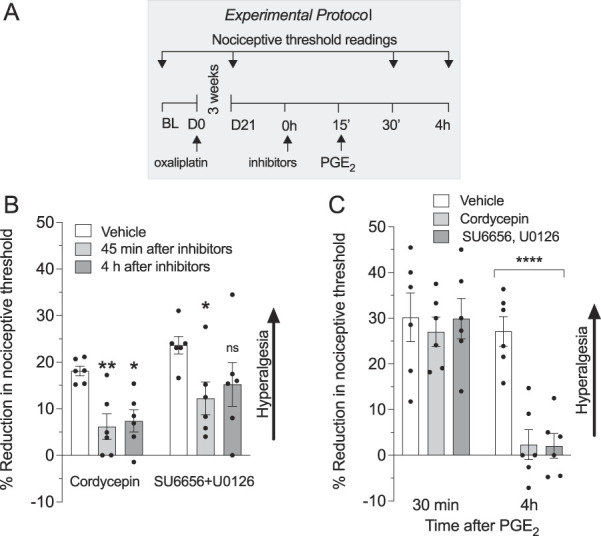

We have classified hyperalgesic priming as having at least 2 mechanistically distinct forms: Type I is dependent on protein translation (ie, it is reversed by injection of cordycepin administered in the vicinity of the nociceptor peripheral or central terminal,27 whereas type II is dependent on the simultaneous activation of Src and MAPK).9 To determine which types of priming are induced by oxaliplatin, on day 21 after administration of oxaliplatin, vehicle, cordycepin, or the combination of an Src and an MAPK inhibitor (SU 6656 and U0126, respectively) was administered intradermally at the site of nociceptive mechanical threshold testing, on the dorsum of the hind paw, followed by injection of PGE2 at the same site. In the groups that received cordycepin or the combination of SU 6656 and U0126, there was a significant attenuation of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia, evaluated 45 minutes after administration of the inhibitors (Figs. 7A and B). Although inhibition of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia persisted, measured 4 hours later in the group of rats receiving cordycepin, hyperalgesia at the fourth hour had partially returned in the group receiving SU 6656 and U0126 (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Oxaliplatin induces type I and II hyperalgesic priming. Male rats received a single intravenous injection of oxaliplatin (2 mg/kg). Twenty-one days later, the protein translation inhibitor, cordycepin (1 µg/20 µL, i.d.) or the combination of an Src kinase inhibitor (SU6656, 1 µg/2 µL, i.d.) and an MAPK inhibitor (U0126, 1 µg/2 µL, i.d.) was administered, on the dorsum of the hind paw at the site of nociceptive threshold testing, followed 15 minutes later by PGE2 (100 ng/5 µL, i.d.) at the same site. In the group that received only oxaliplatin, nociceptive threshold was evaluated before and 21 days after oxaliplatin and again after administration of inhibitors alone or with PGE2. (A) The experimental protocol providing timing of treatments and nociceptive threshold measurements. (B) Both cordycepin and the combination of SU6656 and U0126 attenuate oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia measured on day 21 after administration of oxaliplatin (time F(2, 30) = 8.909, treatment F(1, 30) = 7.235, **P < 0.01: oxaliplatin, vehicle group vs oxaliplatin, cordycepin at 45′, *P < 0.01: oxaliplatin, vehicle group vs oxaliplatin, cordycepin at 4 hours or *P < 0.01: oxaliplatin, vehicle group vs oxaliplatin, SU6656 + U0126 at 45, 1-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). No significant differences between the vehicle-treated group and the group treated with SU6656 plus U0126 were detected at the fourth hour, indicating the transitory effect of this combination of inhibitors on oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia. (C) Hyperalgesic priming, induced by oxaliplatin, is robustly attenuated by cordycepin or by a combination of SU6656 and U0126 because the prolongation of the PGE2 hyperalgesia was observed only in the vehicle-treated group. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 rats/group). These findings support the suggestion that protein translation in nociceptors plays a role in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming. ANOVA, analysis of variance; AS, antisense; BL, baseline; MM, mismatch; PKCε, protein kinase C ε; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

Evaluating for hyperalgesic priming in the oxaliplatin-treated group receiving cordycepin, or in the group receiving the combination of SU 6656 and U0126, hyperalgesia induced by intradermal PGE2 was not present at the fourth hour (Fig. 7C). These findings indicate that oxaliplatin induces both type I and II priming.

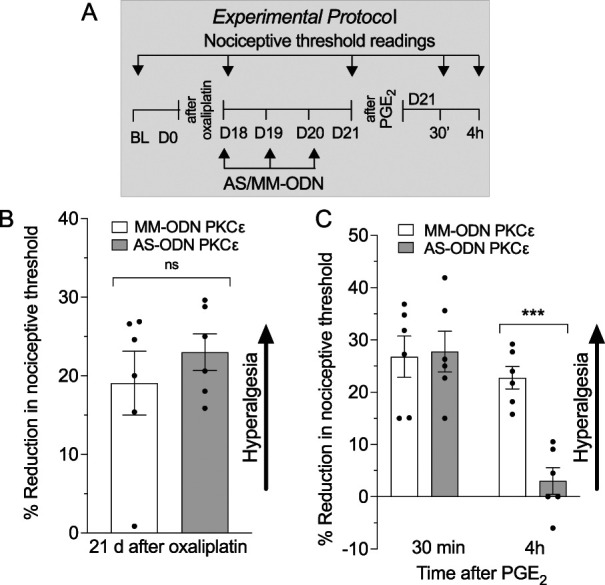

3.7. PKCε antisense attenuated oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming

Induction and expression of type I priming has been shown to be PKCε-dependent.2 Because oxaliplatin induces type I priming to evaluate second messenger signaling in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and priming, we treated groups of rats that had established oxaliplatin CIPN, with an ODN antisense or mismatch to PKCε mRNA.62 Rats received intrathecal injections of ODN antisense or mismatch to PKCε mRNA daily for 3 days, beginning 18 days after administration of oxaliplatin (Fig. 8A). PKCε antisense ODN-treated rats failed to show attenuation of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia (Fig. 8B), consistent with our previous finding with administration an inhibitor of PKCε.37 To evaluate the role of PKCε in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming on day 21, after a third injection of ODNs, PGE2 was injected intradermally, and the mechanical nociceptive threshold was evaluated 30 minutes and 4 hours later, at the same site. Compared with mismatch-treated rats, where PGE2-induced hyperalgesia was present 4 hours after administration, in PKCε antisense ODN-treated rats, hyperalgesia induced by PGE2 was absent (Fig. 8C), indicating PKCε dependence of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming.

Figure 8.

Role of PKCε in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and priming. Male rats received a single intravenous injection of oxaliplatin (2 mg/kg), and on day 18 after administration, MM-ODNs (120 μg/20 μL, black bar) or AS-ODNs (120 μg/20 μL, gray bar) against PKCε mRNA were injected for 3 consecutive days. On day 21, ∼17 hours after the last ODN injection, mechanical nociceptive threshold was measured, and PGE2 (100 ng/5 μL) was injected intradermally. Thirty minutes and 4 hours after PGE2, the mechanical nociceptive threshold was again measured to assess for hyperalgesic priming. (A) The experimental protocol providing timing of treatments and nociceptive threshold measurement. (B) When the magnitude of oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was evaluated on day 21, no differences between PKCε AS-ODN– and MM-ODN–treated groups were observed (t10 = 1.839, P = 0.4203: PKCε AS-ODN–treated group vs PKCε MM-ODN–treated group, unpaired Student t test). (C) PGE2 induced significant hyperalgesia at 30 minutes in PKCε AS-ODN– and MM-ODN–treated group that was no longer present at the fourth hour in the PKCε AS-ODN–treated group (time F(1,20) = 19.73; treatment F(1,20) = 8.417; interaction F(1,20) = 10.22, ***P < 0.01: PKCε AS-ODN–treated group vs PKCε AS-ODN MM-ODN–treated group, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n= 6 rats/group). These findings support the suggestion that although oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia is PKCε-independent, PKCε plays a role in oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ODN, oligodeoxynucleotide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

4. Discussion

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is a common, disabling, serious side-effect of most classes of cancer chemotherapy. The highest prevalence rates of CIPN are observed in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy,43,77 with CIPN induced by oxaliplatin present in 60% to 80% of patients11,59,73 significantly impacting their quality of life. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is the most frequent reason for early discontinuation of treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy regimens.66 In addition to being present during chemotherapy treatment, CIPN persists in ∼68% of patients when assessed 1 month after completion of chemotherapy, and in ∼33% of patients when assessed >6 months after treatment, making CIPN pain a common chronic complication of platinum-based chemotherapy in oncology patients.72

We and others have shown that stress and anxiety, present in oncology patients before starting chemotherapy, are clinical risk factors contributing to the incidence, severity, and duration of CIPN pain.14,47,55,56 Furthermore, in preclinical studies, we have shown that stress exacerbates oxaliplatin-induced pain79 and that adrenalectomy, which extirpates the final common pathway of both the HPA and sympathoadrenal neuroendocrine stress axes, reversed oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia, an effect mediated through nociceptor β2-adrenergic and glucocorticoid receptors.79

An acute peripheral pain syndrome develops in about 89% of patients immediately after oxaliplatin administration.58 Although it has been suggested that a chronic phase of CIPN can be distinguished from acute CIPN,15,24 little is known about the mechanisms underlying the distinction between acute and chronic CIPN pain. For example, it has been suggested that lysophospholipids (eg, lysophosphatidylcholine 18:1), which are acutely increased in sciatic nerve and DRG after oxaliplatin administration, may directly contribute to acute oxaliplatin-induced pain.69 Mechanisms underlying chronic oxaliplatin-induced pain remain to be established. This distinction has been demonstrated for patient receiving platinum-based chemotherapy,11,15,87 as well as in preclinical models of platinum-induced CIPN.71,84 In this study, we evaluated for both the presence of hyperalgesic priming induced by oxaliplatin (demonstrated by persistent hyperalgesia in response to pronociceptive inflammatory mediators, prototypically PGE2) that could contribute to chronic chemotherapy-induced pain, and the contribution of neuroendocrine stress axis mediators, their receptors and second messengers, to hyperalgesic priming associated with oxaliplatin CIPN.

In addition to producing mechanical hyperalgesia (that persisted for approximately 42 days after a single administration), we observed that oxaliplatin also induced hyperalgesic priming (prolongation of PGE2 hyperalgesia). Importantly, hyperalgesic priming was still present, unattenuated, 60 days after administration of oxaliplatin, at which time oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia had resolved, providing support for the hypothesis that hyperalgesic priming contributes to chronic oxaliplatin CIPN pain. Hyperalgesic priming, hypothesized to underlie the transition from acute to chronic pain, and the maintenance of chronic pain in preclinical models of other pain syndromes,25,42,68 and our current observation that oxaliplatin induces hyperalgesic priming, are consistent with the suggestion that hyperalgesic priming contributes to chronic CIPN pain, which can persist in patients long after chemotherapy. However, whether PGE2 or some other pronociceptive mediator is driving the hyperalgesia in the setting of chronic CIPN pain remains to be established.

In a prevention protocol, oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming were both markedly attenuated in adrenalectomized rats, compatible with a role of the HPA and/or sympathoadrenal neuroendocrine stress axes in the induction of oxaliplatin CIPN pain. To evaluate the contribution of the HPA and sympathoadrenal stress axis to oxaliplatin CIPN hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming, as well as their role in the maintenance of CIPN hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming, we administered antisense ODNs, intrathecally, to decrease expression of GR and ADRB2 in sensory neurons to evaluate the role of corticosterone and epinephrine, the final mediators of HPA and sympathoadrenal stress axes, respectively, at their cognate receptors on nociceptors. Although oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was attenuated by ODN antisense to ADRB2, but not by GR antisense, as we have previously shown,79 in the present experiments, we found that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming was markedly attenuated by AS-ODNs for both ADRB2 and GR in a reversal protocol. However, whether ADRB2 or GR AS-ODNs transiently attenuate or reverse hyperalgesic priming remains to be established.

To further elucidate the role of the neuroendocrine stress axes in CIPN pain, we determined whether the induction of stress resilience would also attenuate the ability of oxaliplatin to induce CIPN pain. Using a well-validated procedure to produce stress resilience, neonatal handling, which enhances maternal pup-directed care behavior18 resulting in reduced neuroendocrine response to stressors in adult rats,30,50,67 ie, produces a stress-resilience phenotype, we found that adult rats that have been exposed to neonatal handling failed to develop oxaliplatin CIPN hyperalgesia or hyperalgesic priming. This effect of stress resilience is consistent with the effects of adrenalectomy and antisense knockdown of stress axis mediator receptors in sensory neurons, further supporting the hypothesis that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming are neuroendocrine stress axis-dependent.

In terms of the role of hyperalgesic priming in chronic CIPN pain, we have previously identified at least 2 types of priming: Type I is maintained by protein translation in the peripheral and central terminals of nociceptors,27 and type II is maintained by Src and MAPK, also at the peripheral and central terminals of nociceptors.9 To evaluate the type of priming induced by oxaliplatin, we administered cordycepin, a protein translation inhibitor that prevents and reverses type I priming,27 or the combination of an Src (SU6656) and MAPK (U0126) inhibitor,9 which prevents and reverses type II priming. In the present experiments, we found that the prolongation of PGE2 hyperalgesia (indicative of hyperalgesic priming) induced by oxaliplatin was inhibited by cordycepin, as well as by the combination of Src and MAPK inhibitor, indicating that oxaliplatin induces both type I and type II priming.

Induction and expression of type I hyperalgesic priming is PKCε-dependent.62 In this study, we found that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming is also attenuated by knockdown of PKCε, which, together with our observation of the reversal of priming by cordycepin, is consistent with a contribution of type I priming to chronic oxaliplatin-induced CIPN pain. Interestingly, we also observed that oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming is attenuated by the combination of SU6656 and UO126, supporting the suggestion that oxaliplatin also induces type II hyperalgesic priming. We know of no previous reports of both type I and type II priming occurring at the same site, in this case the peripheral terminal of nociceptors. We have, however, observed that both type I and type II priming can be produced by the same agent (subanalgesic doses of fentanyl), but at different terminals, type I at the peripheral terminal and type II at the central.10 What remains to be explained is how interventions that only reverse 1 type of priming (ie, type I or type II) can completely reverse oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming.

Because type II priming is induced by agonists at Gαi/o G-protein-coupled receptor (eg, as we have shown for the action of µ-opioid receptor agonists6), and the contribution of the sympathoadrenal hormone, epinephrine, acting at the ADBR2 is Gαi-dependent,12,19 we evaluated for a role of Gαi/o proteins in hyperalgesic priming induced by oxaliplatin. Although oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia was not affected by pertussis toxin, a nonselective inhibitor of inhibitory guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory proteins (Gi/o proteins), it reversed oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming, supporting the involvement of a Gαi/o protein in the expression of hyperalgesic priming induced by oxaliplatin. To identify which Gαi/o proteins mediate oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming, AS-ODNs were used that have been shown to selectively attenuate Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, or Gαo. As with pertussis toxin, oxaliplatin hyperalgesia was not affected by knockdown of any of these 4 G-protein subunits. However, hyperalgesic priming induced by oxaliplatin, which was inhibited by pertussis toxin, was eliminated by ODN antisense for Giα1 and Gαo; AS-ODNs for Giα2 or Giα3 had no effect. How priming induced by oxaliplatin is dependent on multiple proteins, Giα1 and Goα, remains to be determined. However, microtubules, a primary target of many chemotherapy agents, including oxaliplatin34 that bind (through tubulin) Giα1 with nanomolar affinity,20 play a key role in neuroplasticity, and ODN antisense to Giα1 mRNA disrupts hippocampal-dependent memory because of loss of neuroplasticity.64 Further studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between memory-like neuronal plasticity in nociceptors and the role of Gαi/o proteins in chronic CIPN pain.

In summary, in the present experiments, we have demonstrated that oxaliplatin induces hyperalgesic priming whose duration long exceeds oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesia. Oxaliplatin-induced hyperalgesic priming, which is neuroendocrine stress axis-dependent, is also Gαi/o- and PKCε-dependent. Of note, the stress axes involved in oxaliplatin hyperalgesia (sympathoadrenal) differ from those involved in hyperalgesic priming (HPA and sympathoadrenal). Importantly, lesion of stress axes can attenuate established hyperalgesia and hyperalgesic priming. Our findings provide the basis for development of novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of CIPN pain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Niloufar Mansooralavi for technical help. This work was supported by a grant from National Cancer Institute (CA250017).

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Contributor Information

Larissa Staurengo-Ferrari, Email: larissa_ferrari@hms.harvard.edu.

Dionéia Araldi, Email: Dioneia.Araldi@ucsf.edu.

Paul G. Green, Email: Paul.Green@ucsf.edu.

References

- [1].Akana SF, Cascio CS, Shinsako J, Dallman MF. Corticosterone: narrow range required for normal body and thymus weight and ACTH. Am J Physiol 1985;249:R527–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aley KO, Messing RO, Mochly-Rosen D, Levine JD. Chronic hypersensitivity for inflammatory nociceptor sensitization mediated by the epsilon isozyme of protein kinase C. J Neurosci 2000;20:4680–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aley KO, Martin A, McMahon T, Mok J, Levine JD, Messing RO. Nociceptor sensitization by extracellular signal-regulated kinases. J Neurosci 2001;21:6933–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Alvarez P, Green PG, Levine JD. Unpredictable stress delays recovery from exercise-induced muscle pain: contribution of the sympathoadrenal axis. Pain Rep 2019;4:e782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Alvarez P, Levine JD, Green PG. Neonatal handling (resilience) attenuates water-avoidance stress induced enhancement of chronic mechanical hyperalgesia in the rat. Neurosci Lett 2015;591:207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Araldi D, Bonet IJM, Green PG, Levine JD. Contribution of G-protein α-subunits to analgesia, hyperalgesia, and hyperalgesic priming induced by subanalgesic and analgesic doses of fentanyl and morphine. J Neurosci 2022;42:1196–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Araldi D, Ferrari LF, Levine JD. Repeated mu-opioid exposure induces a novel form of the hyperalgesic priming model for transition to chronic pain. J Neurosci 2015;35:12502–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Araldi D, Ferrari LF, Levine JD. Gi-protein-coupled 5-HT1B/D receptor agonist sumatriptan induces type I hyperalgesic priming. PAIN 2016;157:1773–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Araldi D, Ferrari LF, Levine JD. Hyperalgesic priming (type II) induced by repeated opioid exposure: maintenance mechanisms. PAIN 2017;158:1204–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Araldi D, Khomula EV, Ferrari LF, Levine JD. Fentanyl induces rapid onset hyperalgesic priming: type I at peripheral and type II at central nociceptor terminals. J Neurosci 2018;38:2226–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Argyriou AA, Cavaletti G, Antonacopoulou A, Genazzani AA, Briani C, Bruna J, Terrazzino S, Velasco R, Alberti P, Campagnolo M, Lonardi S, Cortinovis D, Cazzaniga M, Santos C, Psaromyalou A, Angelopoulou A, Kalofonos HP. Voltage-gated sodium channel polymorphisms play a pivotal role in the development of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: results from a prospective multicenter study. Cancer 2013;119:3570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Baillie GS, Sood A, McPhee I, Gall I, Perry SJ, Lefkowitz RJ, Houslay MD. beta-Arrestin-mediated PDE4 cAMP phosphodiesterase recruitment regulates beta-adrenoceptor switching from Gs to Gi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:940–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [13].Benovic JL. Novel beta2-adrenergic receptor signaling pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;110:S229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bonhof CS, van de Graaf DL, Wasowicz DK, Vreugdenhil G, Mols F. Symptoms of pre-treatment anxiety are associated with the development of chronic peripheral neuropathy among colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2022;30:5421–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Burgess J, Ferdousi M, Gosal D, Boon C, Matsumoto K, Marshall A, Mak T, Marshall A, Frank B, Malik RA, Alam U. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: epidemiology, pathomechanisms and treatment. Oncol Ther 2021;9:385–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cavaletti G, Alberti P, Frigeni B, Piatti M, Susani E. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2011;13:180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Colvin LA. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: where are we now. PAIN 2019;160(suppl 1):S1–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Couto-Pereira NS, Ferreira CF, Lampert C, Arcego DM, Toniazzo AP, Bernardi JR, da Silva DC, Von Poser Toigo E, Diehl LA, Krolow R, Silveira PP, Dalmaz C. Neonatal interventions differently affect maternal care quality and have sexually dimorphic developmental effects on corticosterone secretion. Int J Dev Neurosci 2016;55:72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Daaka Y, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Switching of the coupling of the beta2-adrenergic receptor to different G proteins by protein kinase A. Nature 1997;390:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dave RH, Saengsawang W, Yu JZ, Donati R, Rasenick MM. Heterotrimeric G-proteins interact directly with cytoskeletal components to modify microtubule-dependent cellular processes. Neurosignals 2009;17:100–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dina OA, Khasar SG, Alessandri-Haber N, Green PG, Messing RO, Levine JD. Alcohol-induced stress in painful alcoholic neuropathy. Eur J Neurosci 2008;27:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dina OA, Gear RW, Messing RO, Levine JD. Severity of alcohol-induced painful peripheral neuropathy in female rats: role of estrogen and protein kinase (A and Cepsilon). Neuroscience 2007;145:350–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dina OA, Khasar SG, Gear RW, Levine JD. Activation of Gi induces mechanical hyperalgesia poststress or inflammation. Neuroscience 2009;160:501–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Farhad K, Brannagan TH. Toxic neuropathy. In: Michael JA, Robert BD, editors. Encyclopedia of the neurological sciences. 2nd ed. Oxford: Academic Press, 2014. p. 511–5. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ferrari LF, Araldi D, Green P, Levine JD. Age-dependent sexual dimorphism in susceptibility to develop chronic pain in the rat. Neuroscience 2018;387:170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ferrari LF, Araldi D, Green PG, Levine JD. Marked sexual dimorphism in neuroendocrine mechanisms for the exacerbation of paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy by stress. PAIN 2020;161:865–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ferrari LF, Bogen O, Chu C, Levine JD. Peripheral administration of translation inhibitors reverses increased hyperalgesia in a model of chronic pain in the rat. J Pain 2013;14:731–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ferrari LF, Bogen O, Levine JD. Role of nociceptor alphaCaMKII in transition from acute to chronic pain (hyperalgesic priming) in male and female rats. J Neurosci 2013;33:11002–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ferrari LF, Khomula EV, Araldi D, Levine JD. Marked sexual dimorphism in the role of the ryanodine receptor in a model of pain chronification in the rat. Sci Rep 2016;6:31221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Francis DD, Meaney MJ. Maternal care and the development of stress responses. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1999;9:128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Green PG, Alvarez P, Gear RW, Mendoza D, Levine JD. Further validation of a model of fibromyalgia syndrome in the rat. J Pain 2011;12:811–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hadjimarkou MM, Silva RM, Rossi GC, Pasternak GW, Bodnar RJ. Feeding induced by food deprivation is differentially reduced by G-protein alpha-subunit antisense probes in rats. Brain Res 2002;955:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hendrich J, Alvarez P, Joseph EK, Chen X, Bogen O, Levine JD. Electrophysiological correlates of hyperalgesic priming in vitro and in vivo. PAIN 2013;154:2207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Higa GM, Sypult C. Molecular biology and clinical mitigation of cancer treatment-induced neuropathy. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2016;10:27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Imbe H, Iwai-Liao Y, Senba E. Stress-induced hyperalgesia: animal models and putative mechanisms. Front Biosci 2006;11:2179–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Joseph EK, Parada CA, Levine JD. Hyperalgesic priming in the rat demonstrates marked sexual dimorphism. PAIN 2003;105:143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Joseph EK, Chen X, Bogen O, Levine JD. Oxaliplatin acts on IB4-positive nociceptors to induce an oxidative stress-dependent acute painful peripheral neuropathy. J Pain 2008;9:463–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Joseph EK, Levine JD. Hyperalgesic priming is restricted to isolectin B4-positive nociceptors. Neuroscience 2010;169:431–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Joukal M, Klusáková I, Dubový P. Direct communication of the spinal subarachnoid space with the rat dorsal root ganglia. Ann Anat 2016;205:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Khasar SG, Burkham J, Dina OA, Brown AS, Bogen O, Alessandri-Haber N, Green PG, Reichling DB, Levine JD. Stress induces a switch of intracellular signaling in sensory neurons in a model of generalized pain. J Neurosci 2008;28:5721–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Khasar SG, Dina OA, Green PG, Levine JD. Sound stress-induced long-term enhancement of mechanical hyperalgesia in rats is maintained by sympathoadrenal catecholamines. J Pain 2009;10:1073–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Khomula EV, Ferrari LF, Araldi D, Levine JD. Sexual dimorphism in a reciprocal interaction of ryanodine and IP3 receptors in the induction of hyperalgesic priming. J Neurosci 2017;37:2032–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kroigard T, Schroder HD, Qvortrup C, Eckhoff L, Pfeiffer P, Gaist D, Sindrup SH. Characterization and diagnostic evaluation of chronic polyneuropathies induced by oxaliplatin and docetaxel comparing skin biopsy to quantitative sensory testing and nerve conduction studies. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:623–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kvetnanský R, Fukuhara K, Pacák K, Cizza G, Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ. Endogenous glucocorticoids restrain catecholamine synthesis and release at rest and during immobilization stress in rats. Endocrinology 1993;133:1411–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].La Porta C, Tappe-Theodor A. Differential impact of psychological and psychophysical stress on low back pain in mice. PAIN 2020;161:1442–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lai J, Gold MS, Kim CS, Bian D, Ossipov MH, Hunter JC, Porreca F. Inhibition of neuropathic pain by decreased expression of the tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel, NaV1.8. PAIN 2002;95:143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lee KM, Jung D, Hwang H, Son KL, Kim TY, Im SA, Lee KH, Hahm BJ. Pre-treatment anxiety is associated with persistent chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in women treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Psychosom Res 2018;108:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Levine S. Infantile experience and resistance to physiological stress. Science 1957;126:405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Li X, Hu L. The role of stress regulation on neural plasticity in pain chronification. Neural Plast 2016;2016:6402942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Liu D, Diorio J, Tannenbaum B, Caldji C, Francis D, Freedman A, Sharma S, Pearson D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. Science 1997;277:1659–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ma X, Hu Y, Batebi H, Heng J, Xu J, Liu X, Niu X, Li H, Hildebrand PW, Jin C, Kobilka BK. Analysis of β2AR-Gs and β2AR-Gi complex formation by NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117:23096–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Macri S, Wurbel H. Developmental plasticity of HPA and fear responses in rats: a critical review of the maternal mediation hypothesis. Horm Behav 2006;50:667–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mestre C, Pélissier T, Fialip J, Wilcox G, Eschalier A. A method to perform direct transcutaneous intrathecal injection in rats. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 1994;32:197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Harris CS, Shin J, Oppegaard K, Conley YP, Hammer M, Kober KM, Levine JD. Determination of cutpoints for symptom burden in oncology patients receiving chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;63:42–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Mastick J, Abrams G, Topp K, Smoot B, Kober KM, Chesney M, Mazor M, Mausisa G, Schumacher M, Conley YP, Sabes JH, Cheung S, Wallhagen M, Levine JD. Associations between perceived stress and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and otoxicity in adult cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Morris CE. Mechanosensitive ion channels. J Membr Biol 1990;113:93–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Oppegaard K, Harris CS, Shin J, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Levine JD, Conley YP, Hammer M, Cartwright F, Wright F, Dunn L, Kober KM, Miaskowski C. Anxiety profiles are associated with stress, resilience and symptom severity in outpatients receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:7825–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Pachman DR, Qin R, Seisler DK, Smith EML, Beutler AS, Ta LE, Lafky JM, Wagner-Johnston ND, Ruddy KJ, Dakhil S. Clinical course of oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy: results from the randomized phase III trial N08CB (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Palugulla S, Dkhar SA, Kayal S, Narayan SK. Oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy in south Indian cancer patients: a prospective study in digestive tract cancer patients. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 2017;38:502–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Parada CA, Reichling DB, Levine JD. Chronic hyperalgesic priming in the rat involves a novel interaction between cAMP and PKCepsilon second messenger pathways. PAIN 2005;113:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Parada CA, Yeh JJ, Joseph EK, Levine JD. Tumor necrosis factor receptor type-1 in sensory neurons contributes to induction of chronic enhancement of inflammatory hyperalgesia in rat. Eur J Neurosci 2003;17:1847–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Parada CA, Yeh JJ, Reichling DB, Levine JD. Transient attenuation of protein kinase C epsilon can terminate a chronic hyperalgesic state in the rat. Neuroscience 2003;120:219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Park SB, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander ML, Kiernan MC. Long-term neuropathy after oxaliplatin treatment: challenging the dictum of reversibility. Oncologist 2011;16:708–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Pineda VV, Athos JI, Wang H, Celver J, Ippolito D, Boulay G, Birnbaumer L, Storm DR. Removal of G(ialpha1) constraints on adenylyl cyclase in the hippocampus enhances LTP and impairs memory formation. Neuron 2004;41:153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Price TJ, Basbaum AI, Bresnahan J, Chambers JF, De Koninck Y, Edwards RR, Ji RR, Katz J, Kavelaars A, Levine JD, Porter L, Schechter N, Sluka KA, Terman GW, Wager TD, Yaksh TL, Dworkin RH. Transition to chronic pain: opportunities for novel therapeutics. Nat Rev Neurosci 2018;19:383–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Prutianu I, Alexa-Stratulat T, Cristea EO, Nicolau A, Moisuc DC, Covrig AA, Ivanov K, Croitoru AE, Miron MI, Dinu MI, Ivanov AV, Marinca MV, Radu I, Gafton B. Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy and colo-rectal cancer patient's quality of life: practical lessons from a prospective cross-sectional, real-world study. World J Clin Cases 2022;10:3101–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Pryce CR, Feldon J. Long-term neurobehavioural impact of the postnatal environment in rats: manipulations, effects and mediating mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2003;27:57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Reichling DB, Levine JD. Critical role of nociceptor plasticity in chronic pain. Trends Neurosci 2009;32:611–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Rimola V, Hahnefeld L, Zhao J, Jiang C, Angioni C, Schreiber Y, Osthues T, Pierre S, Geisslinger G, Ji R-R. Lysophospholipids contribute to oxaliplatin-induced acute peripheral pain. J Neurosci 2020;40:9519–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Rossi GC, Standifer KM, Pasternak GW. Differential blockade of morphine and morphine-6 beta-glucuronide analgesia by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides directed against MOR-1 and G-protein alpha subunits in rats. Neurosci Lett 1995;198:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Sakurai M, Egashira N, Kawashiri T, Yano T, Ikesue H, Oishi R. Oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy in the rat: involvement of oxalate in cold hyperalgesia but not mechanical allodynia. PAIN 2009;147:165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Seretny M, Currie GL, Sena ES, Ramnarine S, Grant R, MacLeod MR, Colvin LA, Fallon M. Incidence, prevalence, and predictors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN 2014;155:2461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Shahriari-Ahmadi A, Fahimi A, Payandeh M, Sadeghi M. Prevalence of oxaliplatin-induced chronic neuropathy and influencing factors in patients with colorectal cancer in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015;16:7603–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Shin J, Harris C, Oppegaard K, Kober KM, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Hammer M, Conley Y, Levine JD, Miaskowski C. Worst pain severity profiles of oncology patients are associated with significant stress and multiple co-occurring symptoms. J Pain 2022;23:74–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Silva RM, Grossman HC, Rossi GC, Pasternak GW, Bodnar RJ. Pharmacological characterization of beta-endorphin- and dynorphin A(1-17)-induced feeding using G-protein alpha-subunit antisense probes in rats. Peptides 2002;23:1101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Song MJ, Wang YQ, Wu GC. Additive anti-hyperalgesia of electroacupuncture and intrathecal antisense oligodeoxynucleotide to interleukin-1 receptor type I on carrageenan-induced inflammatory pain in rats. Brain Res Bull 2009;78:335–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Soveri LM, Lamminmäki A, Hänninen UA, Karhunen M, Bono P, Osterlund P. Long-term neuropathy and quality of life in colorectal cancer patients treated with oxaliplatin containing adjuvant chemotherapy. Acta Oncol 2019;58:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Standifer KM, Rossi GC, Pasternak GW. Differential blockade of opioid analgesia by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides directed against various G protein alpha subunits. Mol Pharmacol 1996;50:293–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Staurengo-Ferrari L, Green PG, Araldi D, Ferrari LF, Miaskowski C, Levine JD. Sexual dimorphism in the contribution of neuroendocrine stress axes to oxaliplatin-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. PAIN 2021;162:907–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Stone LS, Vulchanova L. The pain of antisense: in vivo application of antisense oligonucleotides for functional genomics in pain and analgesia. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2003;55:1081–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Strausbaugh HJ, Dallman MF, Levine JD. Repeated, but not acute, stress suppresses inflammatory plasma extravasation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:14629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Strausbaugh HJ, Green PG, Dallman MF, Levine JD. Repeated, non-habituating stress suppresses inflammatory plasma extravasation by a novel, sympathoadrenal dependent mechanism. Eur J Neurosci 2003;17:805–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Taiwo YO, Bjerknes LK, Goetzl EJ, Levine JD. Mediation of primary afferent peripheral hyperalgesia by the cAMP second messenger system. Neuroscience 1989;32:577–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Toyama S, Shimoyama N, Ishida Y, Koyasu T, Szeto HH, Shimoyama M. Characterization of acute and chronic neuropathies induced by oxaliplatin in mice and differential effects of a novel mitochondria-targeted antioxidant on the neuropathies. Anesthesiology 2014;120:459–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:397–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Wainford RD, Kapusta DR. Functional selectivity of central Gα-subunit proteins in mediating the cardiovascular and renal excretory responses evoked by central α(2) -adrenoceptor activation in vivo. Br J Pharmacol 2012;166:210–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Zajączkowska R, Kocot-Kępska M, Leppert W, Wrzosek A, Mika J, Wordliczek J. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:E1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]