Abstract

Background:

We studied the effect of APOE-ε4 status and sex on age of symptom onset (AO) in early- (EO) and late- (LO) onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Method:

998 EOAD and 2562 LOAD from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center were included. We used ANOVA to examine AO differences between sexes and APOE genotypes and the effect of APOE-ε4, sex, and their interaction on AO in EOAD and LOAD, separately.

Results:

APOE-ε4 carriers in LOAD had younger AO and in EOAD had older AO. Female EOAD APOE-ε4 carriers had older AO compared to noncarriers (p < 0.0001). There was no difference for males. Both male and female LOAD APOE-ε4 carriers had younger AO relative to noncarriers (p < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

The observed earlier AO in EOAD APOE-ε4 noncarriers relative to carriers, particularly in females, suggests the presence of additional AD risk variants.

Keywords: APOE-ε4, age of onset, early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, sex

1. Introduction

Apolipoprotein-ε4 (APOE-ε4) is the strongest genetic risk factor for sporadic late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). It causes an earlier age of symptom onset compared to other APOE genotypes [1, 2]. However, it has been suggested that in early-onset AD (EOAD), APOE-ε4 might be counterintuitively associated with later disease onset [3].

Female sex is also a risk factor for developing AD [4]. A recent meta-analysis including individuals 55–85 years of age showed that sex has a maximal AD risk effect between the ages 65 and 75 [5]. However, whether sex and APOE-ε4 status interact to impact age of onset is less clear [6, 7], particularly in EOAD.

Here we examined the association of APOE genotype and sex with age of symptom onset in a large sample of LOAD and EOAD participants from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Our analyses used data from 36 past and present Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADC) who are part of NACC. Data were collected between September 2005 and January 2021 following informed consent as mandated by the respective Institutional Review Boards at each ADC Institution.

This study included all eligible EOAD and LOAD participants (onset-age < or ≥ 65) who had APOE genotyping, full Uniform Data Set (UDS) testing, and primary diagnosis of MCI or dementia due to probable AD for at least three consecutive visits from the NACC database (n = 4693 participants, 22,734 visits). All participants had an MCI or dementia diagnosis from first observation. Participants with autosomal dominant AD or frontotemporal dementia (FTD) mutations, significant comorbid conditions, including severe white matter hyperintensities (Cardiovascular Health Study score 5–8+), psychiatric disorders (except depression), and cognitive disorder due to other neurological, neurodegenerative, or systemic illness, were excluded (n = 1113). Another 20 participants were excluded because their age of onset could not be determined. Our final sample consisted of 3560 (75.9%) participants – 998 EOAD and 2562 LOAD.

2.2. Genotyping

NACC, its partners, and the ADCs work together to track phenotypic data, biologic specimens, and genotypic data from ADC participants (https://naccdata.org/nacc-collaborations/partnerships). Participants in the present study were selected based on the availability of APOE allele data.

2.2. Age of onset

Age of onset was collected during the initial clinical evaluation by a clinician. NACC states that determination of age of onset is “Based on the clinician’s assessment, at what age did the cognitive decline begin? (The clinician must use his/her best judgement to estimate an age of onset).” Therefore, clinical judgement plays a large role in determining age of onset where there is no objective data (e.g., a previously normal cognitive exam), which is the large majority of cases. This clinical judgment relies heavily on patient and informant report of onset of symptoms via thorough clinical interview.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were run in SAS version 9.4. T-tests and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate were used to compare baseline characteristics between EOAD and LOAD subjects. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were used to determine the association of APOE-ε4 status, sex and their interaction with age of onset in EOAD and LOAD, separately.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Demographic data are shown in the Table 1A. Compared to the EOAD group, the LOAD group was less educated (p <.0001) and had a lower rate of the APOE-ε4 allele (p < .0082). The EOAD group had higher rates of dementia diagnosis and lower rates of MCI than did the LOAD group (p < .0001). There were no significant sex differences between groups (p = 0.97). Both groups were near 90% white, non-Hispanic/Latino/a. The LOAD group outperformed the EOAD group on CDR-SB (p = .0084) and MoCA (p = .0006) at their initial visit. Of note, some MoCA scores were MMSE scores converted using crosswalk analysis (n = 2992; see [8] for description of crosswalk data). The LOAD group was more likely to have a positive family history among 1st-degree relatives (p = 0.02).

Table 1.

(A) Demographics and (B) APOE-ε4 comparisons between EOAD and LOAD

| A. Demographics | EOAD (n=998) |

LOAD (n=2562) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current age, years, Mean+SD | 62.5 ± 5.9 | 78.3 ± 5.9 | <.0001 |

|

| |||

| Age of onset, Mean+SD | (n=994) 57.5 (5.1) |

(n=2518) 74.1 (5.9) |

<.0001 |

| Female | 549 (55%) | 1411 (55%) | .9724 |

| Hispanic/Latino/a | (n=993) 75 (7.6%) |

(n=2554) 196 (7.7%) |

.9028 |

| Race, N (%) | (n=981) | (n=2524) | .0066 |

| Black or African American | 56 (5.7%) | 223 (8.8%) | |

| White | 873 (89.0%) | 2187 (86.6%) | |

| Other | 52 (5.3%) | 114 (4.5%) | |

| Years of Education, Mean+SD | (n=995) 15.2 ± 3.1 |

(n=2555) 14.7 ± 3.6 |

<.0001 |

| Diagnostic Group, N (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Dementia | 810 (81.2%) | 1912 (74.6%) | |

| MCI | 188 (18.8%) | 650 (25.4%) | |

| 1st degree relative with dementia | (n=936) 577 (61.6%) |

(n=2319) 1529 (65.9%) |

.0205 |

| CDR-SB | 5.0 ± 3.6 | 4.7 ± 3.5 | .0084 |

| MoCA | (n=950) 15.8 ± 5.5 |

(n=2513) 16.5 ± 4.8 |

.0006 |

|

| |||

| B. APOE-ε4 | |||

|

| |||

| APOE-ε4 carriers, N (%) | 655 (65.6%) | 1559 (60.9%) | .0082 |

| Female APOE-ε4 carriers | 364/549 (36.4%) | 872/1411 (34.0%) | |

| Male APOE-ε4 carriers | 291/449 (29.2%) | 687/1151 (26.8%) | |

| APOE genotype, N (%) | <.0001 | ||

| APOE-ε4 / 4 | 225 (22.5%) | 285 (11.1%) | |

| APOE-ε3 / 4 | 413 (41.4%) | 1193 (46.6%) | |

| APOE-ε2 / 4 | 17 (1.7%) | 81 (3.2%) | |

| APOE-ε3 / 3 | 317 (31.8%) | 892 (34.8%) | |

| APOE-ε3 / 2 | 24 (2.4%) | 107 (4.2%) | |

| APOE-ε2 / 2 | 2 (0.2%) | 4 (0.2%) | |

| Age of onset x APOE, Mean+SD | <.0001 | ||

| APOE-ε4 / 4 | 58.4 (4.5) | 71.1 (4.6) | |

| APOE-ε3 / 4 | 57.6 (5.3) | 73.3 (5.5) | |

| APOE-ε2 / 4 | 57.9 (4.7) | 74.4 (6.0) | |

| APOE-ε3 / 3 | 56.6 (5.3) | 75.9 (6.0) | |

| APOE-ε3 / 2 | 58.0 (4.7) | 77.5 (6.7) | |

| APOE-ε2 / 2 | 59.0 (2.8) | 78.8 (7.6) | |

Note: N is noted where data are missing. CDR-SB = Clinical Dementia Rating scale – sum of boxes; EOAD = early-onset Alzheimer’s disease; LOAD = late-onset Alzheimer’s disease; MoCA = Montreal cognitive assessment (of note, some MoCA scores were MMSE scores converted using crosswalk analysis (n = 2992; see [7] for description of crosswalk data).

3.2. Main analyses

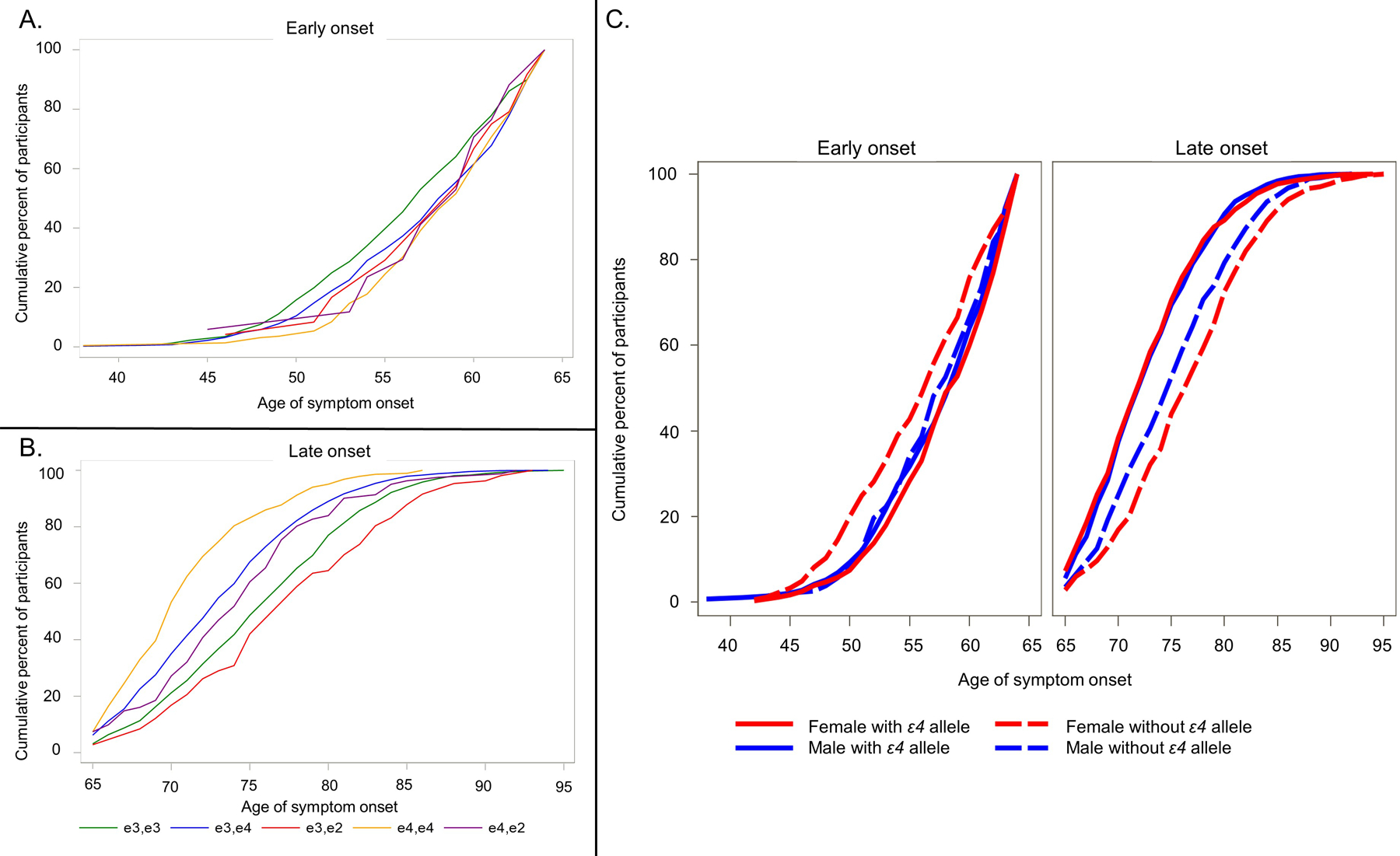

LOAD APOE-ε4 carriers had a significantly younger age of onset compared to noncarriers (73.0 ± 5.5 vs. 76.1 ± 6.1, p = 0.0001). APOE-ε4/4 were the youngest, followed by APOE-ε3/4, APOE-ε2/4, APOE-ε3/3, APOE-ε3/2 and APOE-ε2/2 (Table 1B and Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Cumulative percentage of age of symptom onset in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease by APOE status (B) Cumulative percentage of age of symptom onset in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease by APOE status (C) Cumulative percentage of age of symptom onset in early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease as a function of sex and APOE status

EOAD APOE-ε4 carriers had a significantly older age of onset compared to noncarriers (57.9 ± 5.0 vs. 56.7 ± 5.3, p = 0.0003). In EOAD APOE-ε3/3 were the youngest, followed by APOE-ε3/4, APOE-ε2/4, APOE-ε3/2, APOE- ε4/4 and APOE- ε2/2 (Table 1B and Figure 1B).

ANOVAs showed significant interactions between sex and APOE-ε4 carrier status for both EOAD, p = 0.005, and LOAD, p = 0.0004 (Figure 1C and Supplemental Table 1). In EOAD, female APOE-ε4 carriers were significantly older compared to noncarriers (58.1 ± 4.9 vs. 56.0 ± 5.5, p < 0.0001) but male APOE-ε4 carriers and noncarriers did not differ by age of onset (57.6 ± 5.1 vs. 57.5 ± 4.9, p = 0.700). In LOAD, both male and female APOE-ε4 carriers had younger age of onset relative to noncarriers (males: 73.0 ± 5.3 vs. 75.3 ± 5.9; females 72.9 ± 5.6 vs. 76.8 ± 6.2, ps < 0.0001). However, female APOE-ε4 carriers were significantly younger than male APOE-ε4 carriers (p < .001). Of note, adjusting for race in the models did not result in any differences in the significant interactions between APOE-ε4 and sex on age of onset. As such, we report only the race-unadjusted models.

4. Discussion

As hypothesized, LOAD APOE-ε4 carriers had younger age of onset than noncarriers and the opposite was observed in EOAD – APOE-ε4 carriers were older than noncarriers. However, this latter finding was driven largely by females, suggesting sex also plays an important role in age of symptom onset in EOAD.

Our findings are consistent with the dose-dependent risk effect of the APOE-ε4 allele and the dose-dependent protective effect of the APOE-ε2 allele on age of onset in LOAD [9, 10]. Those at highest risk of AD, APOE-ε4/4, also had the youngest age of onset while those with lowest risk APOE-ε2/2 had the oldest age of onset (although there were only four participants in the latter group). These findings were similar between females and males, suggesting sex does not alter the risk of effect of APOE-ε4 on age of onset in LOAD.

In contrast, a dose-dependent risk effect of APOE-ε4 was not found in EOAD. Instead, the pattern among all genotypes was more mixed than in LOAD and ε4 noncarriers were at overall higher risk for earlier onset. While there appears to be an age window of maximal effects for ε4 carriers, with peak onset for this group between early 60s to 70s, non-ε4 variants show a bimodal distribution [10]. Age of onset in non-ε4 carriers peaks around 57, then drops off and peaks again around 77 years of age. However, this genotype effect in the age range of EOAD appears primarily driven by female sex.

Previous work has shown APOE genotype interacts with sex to impact risk of AD [6], but this appears to be the case only in younger individuals (ages 55–70) [5]. We found sex also impacts age of symptom onset but only in a younger group (i.e., EOAD). Female but not male ε4 carriers showed a significantly older age of onset than noncarriers. This interaction effect has not been previously studied in EOAD to our knowledge. Younger females, particularly those who are amyloid-positive, accumulate tau at faster rates than others [11]. Exploring genetic markers of abnormal tau accumulation could help explain some of these age of onset differences in EOAD. It is also possible that hormonal and metabolic alterations associated with menopause and perimenopause may be interacting with APOE genotype to create differences in symptom onset between ε4 carriers and noncarriers [12] but these studies have yet to be conducted. With respect to our LOAD group, our results are consistent with prior work showing no sex differences in age of onset for APOE-ε4 carriers versus noncarriers [7].

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

We addressed prior limitations in the field by utilizing a large well-characterized sample (n = 3560) and by excluding individuals with significant comorbid pathologies that could contribute independently to cognitive decline and affect disease onset. We further excluded individuals with genetic mutations associated with AD and FTD who have disease onset at young age by virtue of their autosomal dominant mutations.

However, the current study was not without limitations. Age of onset was determined by retrospective self- or informant report, which is less reliable than an objective evaluation. Participants did not have pathologically confirmed AD and as such misdiagnoses might have occurred [13]. Disease severity was distributed differently between EOAD (dementia > MCI) and LOAD (MCI > dementia). This difference is potentially meaningful if disease stage plays a role in associations with APOE-ε4. Our sample contained only individuals from North America who were mostly White, non-Hispanic/Latino/a/x and well-educated, limiting the generalizability of our results. While re-running our analyses adjusting for race did not change the findings, this may have been influenced by the very low sample sizes of other groups compared to the non-White, non-Hispanic/Latino/a group. This is an important limitation as race-based differences in APOE genotype have consistently been shown [3, 6, 7, 14].

4.2. Conclusions

Female APOE-ε4 noncarriers are at greatest risk for younger age of onset of symptoms in EOAD. This suggests the role of still unknown genetic risk factors in the development of AD, particularly at younger ages. Investigation in other large research consortia such as the Longitudinal Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease (LEADS; [15]) are ongoing and can further characterize genetic and other risk factors in EOAD.

Supplementary Material

Research in Context.

Systematic review:

We used defined search terms in traditional search engines (e.g., PubMed) and reference sections from prior related works to identify relevant papers. We reviewed the literature broadly as there are few studies examining the impact of APOE-ε4 and particularly sex, on the age of onset in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD).

Interpretation:

In a large sample of syndromically diverse patients with sporadic probable AD, our findings highlight the clinical importance of APOE-ε4 and sex in predicting age of onset in AD, particularly in EOAD. Additionally, we provide further evidence of disease variance in the patterns of symptom presentation in EOAD and LOAD.

Future directions:

Investigation in other large research consortia such as the Longitudinal Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Study (LEADS) can help further characterize influences of APOE-ε4 and sex on age of onset in EOAD.

Funding sources:

NIA U01AG6057195 (L.G.A., A.J.P.), NIA P30 AG010133 (L.G.A., A.J.P.), NIA P30 AG072976 (L.G.A.) Alz. Assoc. LDRFP-21–818464 (A.J.P.)

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U24 AG072122. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG066546 (PI Sudha Seshadri, MD), P20 AG068024 (PI Erik Roberson, MD, PhD), P20 AG068053 (PI Marwan Sabbagh, MD), P20 AG068077 (PI Gary Rosenberg, MD), P20 AG068082 (PI Angela Jefferson, PhD), P30 AG072958 (PI Heather Whitson, MD), P30 AG072959 (PI James Leverenz, MD)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest and Disclosures

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

L.G.A. has received personal compensation in the range of $500-$4,999 for serving as a Consultant for NIH, Florida Dept of Health, NIH Biobank, Eli Lilly, and GE Healthcare. L.G.A. has received personal compensation in the range of $500-$4,999 for serving on a Scientific Advisory or Data Safety Monitoring board for Eisai and serving on a Scientific Advisory or Data Safety Monitoring board for Two labs. L.G.A. has received personal compensation in the range of $5,000-$9,999 for serving as a Consultant for Biogen, serving on a Scientific Advisory or Data Safety Monitoring board for IQVIA, and serving on a Scientific Advisory or Data Safety Monitoring board for Biogen. L.G.A. has received personal compensation in the range of $10,000-$49,999 for serving as an Editor, Associate Editor, or Editorial Advisory Board Member for Alzheimer Association. An immediate family member of L.G.A. has stock in Semiring, Cassava Neurosciences, and Golden Seed. The institution of L.G.A. has received research support from Roche, NIA, Alzheimer Association, AVID radiopharmaceuticals, and Life Molecular Imaging.

References

- 1.Bettens K, Sleegers K, and Van Broeckhoven C, Genetic insights in Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology, 2013. 12(1): p. 92–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blacker D, et al. , ApoE-4 and age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease: the NIMH genetics initiative. Neurology, 1997. 48(1): p. 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson Y, et al. , Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele frequency and age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 2007. 23(1): p. 60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riedel BC, Thompson PM, and Brinton RD, Age, APOE and sex: Triad of risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 2016. 160: p. 134–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neu SC, et al. , Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Sex Risk Factors for Alzheimer Disease: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol, 2017. 74(10): p. 1178–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrer LA, et al. , Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA, 1997. 278(16): p. 1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell DS, et al. , The Relationship of APOE epsilon4, Race, and Sex on the Age of Onset and Risk of Dementia. Front Neurol, 2021. 12: p. 735036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polsinelli AJ, et al. , APOE-ε4 carrier status and sex differentiate rates of cognitive decline in early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Corder EH, et al. , Protective effect of apolipoprotein E type 2 allele for late onset Alzheimer disease. Nature Genetics, 1994. 7(2): p. 180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smirnov DS, et al. , Age-at-Onset and APOE-Related Heterogeneity in Pathologically Confirmed Sporadic Alzheimer Disease. Neurology, 2021. 96(18): p. e2272–e2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith R, et al. , The accumulation rate of tau aggregates is higher in females and younger amyloid-positive subjects. Brain, 2020. 143(12): p. 3805–3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valencia-Olvera AC, et al. , Role of estrogen in women’s Alzheimer’s disease risk as modified by APOE. J Neuroendocrinol, 2022: p. e13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Beach TG, et al. , Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 2012. 71(4): p. 266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendrie HC, et al. , APOE epsilon4 and the risk for Alzheimer disease and cognitive decline in African Americans and Yoruba. Int Psychogeriatr, 2014. 26(6): p. 977–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apostolova LG, et al. , The Longitudinal Early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease Study (LEADS): Framework and methodology. Alzheimers Dement, 2021. 17(12): p. 2043–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.