Abstract

Aims:

To examine existing community-institutional partnerships providing health care services to people experiencing homelessness by addressing social determinants of health (SDOH) at multiple socioecological levels.

Design:

Integrative Review

Data sources:

PubMed (Public/Publisher MEDLINE), CINAHL (The Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature database), and EMBASE (Excerpta Medica database) were searched to identify articles on health care services, partnerships, and transitional housing.

Review Methods:

Database search used the following keywords: public-private sector partnerships, community-institutional relation, community-academic, academic community, community university, university community, housing, emergency shelter, homeless persons, shelter, and transitional housing. Articles published until November 2021 were eligible for inclusion. The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Quality Guide was used to appraise the quality of articles included in the review by two researchers.

Results:

Seventeen total articles were included in the review. The types of partnerships discussed in the articles included academic-community partnerships (n=12) and hospital-community partnerships (n=5). Health services were also provided by different kinds of health care providers, including nursing and medical students, nurses, physicians, social workers, psychiatrists, nutritionists, and pharmacists. Health care services spanning from preventative care services to acute and specialized care services and health education were also made possible through community-institutional partnerships.

Conclusion:

There is a need for more studies on partnerships that aim to improve the health of homeless populations by addressing social determinants of health at multiple socioecological levels of individuals who experience homelessness. Existing studies do not utilize elaborate evaluation methods to determine partnership efficacy.

Impact:

Findings from this review highlight gaps in the current understanding of partnerships that seek to increase access to care services for people who experience homelessness.

Keywords: health services, transitional housing, community institutional partnership, homelessness, shelter, community-academic partnership, partnership, prevention, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Homelessness is a global challenge. Over 1.6 billion people live in inadequate housing conditions worldwide, and more than 100 million people have no housing at all (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2020). About 15 million people are forcefully evicted annually and are often pushed into homelessness by a multitude of different factors ranging from economic to social and environmental factors (UN Habitat, 2022). In the United States, 3.5 million people experience homelessness at any given year (National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, 2011). The experience of homelessness is defined as lacking a regular or adequate nighttime residence (Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2018). This definition also includes residence in emergency or transitional housing and living in a residence that is a public/private place not meant for inhabitation (street dwelling, abandoned home dwelling). In 2020, 580,000 people experienced homelessness on a single night (Henry et al., 2020). According to the National Health Care for Homeless Council (2019), people who experience homelessness have higher rates of illness and have a decreased lifespan of 12 years compared to the general U.S. population.

People who experience homelessness are inundated with numerous health challenges (Weinreb, Nicholson, Williams, & Anthes, 2007). Compared to those who do not experience homelessness, the U.S. homeless population has a higher prevalence of mental health disorders (Padgett, 2020), chronic health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and asthma (National Health Care for the Homeless Council, 2019), as well as physical abuse, sexual abuse, and childhood neglect (National Network to End Domestic Violence, 2018). The provision of preventative, primary, and specialty health services is critical to address the complex health needs of this vulnerable population. However, access to health services is a major concern (Davies & Wood, 2018).

Homeless populations face numerous barriers to care, including lack of stable housing, health insurance, transportation, stable social networks, childcare coverage, and consistent information reception by mail and telephone (White & Newman, 2015; Jagasia et al., 2022). Providing on-site health services in shelter settings reduces barriers and challenges to accessing health services. In particular, transitional housing settings and shelters serve as optimal locations to provide health services to people who experience homelessness because more than half the homeless population live in emergency shelters and transitional housing programs (Henry et al., 2020). Housing is an essential component of improving the health of people who experience homelessness because medical services cannot be fully effective when individuals are constantly compromised by external harsh conditions (National Health Care for the Homeless Council, 2019). Integrating health services into transitional housing programs may also bridge homeless populations to valuable health services and resources that address their complex health needs.

Nurses are important providers of health services in community settings due to their ability to collaborate across many health sectors (Porter-OʼGrady, 2018). The nursing roles of advocacy and care delivery are essential components of health delivery to marginalized populations to ensure that people who experience homelessness undergo healthy transitions into permanent housing programs. As such, nurses must continue to promote care delivery to homeless populations so that much-needed safe and quality health care services are available and accessible.

BACKGROUND

Addressing health for individuals experiencing homelessness in the United States requires both the recognition of social determinants of health and the identification of interventions, systems, and policies that best promote care access and engagement. Consistent with Healthy People 2030, social determinants of health (SDOH) are defined as “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks” (Gomez et al. 2021). In addition to SDOH, the experience of homelessness can be viewed through a socioecological lens to identify and address multiple dimensions that influence health. As mentioned previously, there are varying interconnected pathways related to homelessness. Providing shelter is a critical component of addressing homelessness, but the inclusion of additional SDOH at multiple levels of the socioecology such as individual knowledge, social support, safety, access to services and resources, and policies that protect health are critical to addressing the needs of this population.

When conceptualizing the conditions of people experiencing homelessness, many intersections arise. Health and homelessness have been intrinsically linked; individuals who face high health burdens (i.e. HIV, diabetes, depression, psychiatric disorders) are also disproportionately affected by higher rates of homelessness (Fazel et al., 2014). Inability to obtain affordable housing and inconsistency of stable income are also linked to increased rates of homelessness. Substance use disorders may also escalate the risk of first-time homelessness in previously housed individuals (Thompson Jr. et al., 2013).

Exposure to household violence is a major risk factor for homelessness, particularly for women. Studies surveying homeless populations reveal that women and children experiencing homelessness are 80% more likely to have prior experiences of domestic violence compared to those without experiences of violence (Aratani, 2009; Ervin et al., 2022). For young people, history of mental or behavioral health challenges, school or academic issues, traumatic experiences, and nonheterosexual sexual orientation intensify risk for homelessness (Grattan et al., 2022). Structural racism also plays a major role in the mentioned intersections, with African American and Indigenous peoples experiencing homelessness at higher rates than White people (Jones, 2016). Historic and present racial inequities continue to perpetrate systemic injustices in housing, employment, health care access, resource allocation, and exposure to violence, all affecting acute and chronic health outcomes. The many intersections of homelessness are directly tied to SDOH. Promoting health access in this population must address current health issues while considering past adversity and the root causes of current problems.

Recognizing these intersections and identifying community institutional partnerships (CIP) that address health factors on multiple levels of the Ecological Model of Health Promotion are essential. Understanding methods that are effective at addressing the needs of the population and identifying gaps in current partnerships can better prepare practitioners and researchers to address the needs of individuals experiencing homelessness. Community institutional partnerships are inclusive of two distinct entities. The first, community, is defined as “a group of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by social ties, share common perspectives, and engage in joint action in geographical locations or settings” (MacQueen et al., 2001). In this review, community is elucidated as a grouping of peoples or organizations not tied to an academic institution whose goal is to address the needs of individuals experiencing homelessness. The second piece of CIP includes the term “institutional,” which comprises of social institutions with organizational characters including academic institutions, state and local public health agencies, health care institutions, and/or funding agencies (McLeroy et al., 1988).

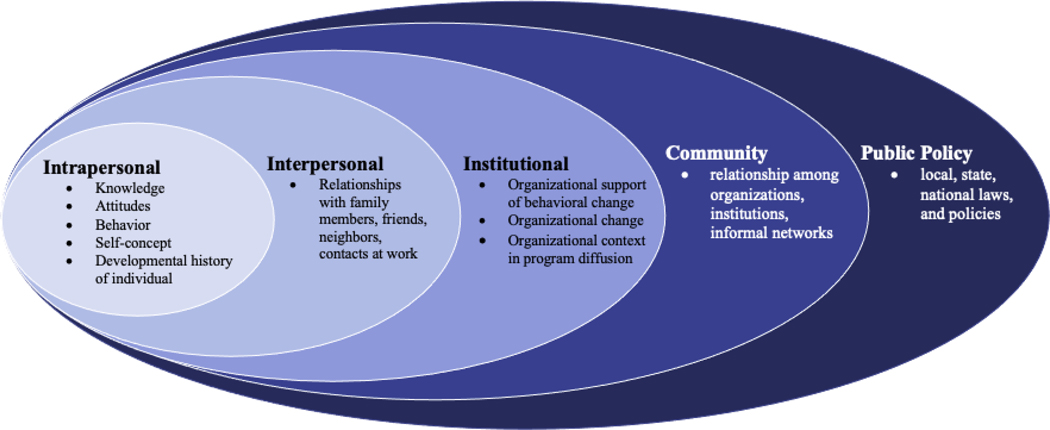

The Ecological Model of Health Promotion (EMHP) has been utilized in many studies relating to experiences of homelessness (Davidson et al., 2016; Rodriguez et al., 2021; Trejos Saucedo et al., 2022) and states that health and behaviors affecting health promotion interventions are influenced by five distinct but connected dimensions shaped by SDOH (McLeroy et al., 1988). The first level, the intrapersonal level, refers to personal factors and identifies intersections placing an individual at high risk of experiencing homelessness. The second level, the interpersonal level, identifies current social and familial supports that influence housing stability. At the institutional level, social institutions, as well as formal and informal roles and regulations of organizations influence homelessness. Community factors relate to the availability of resources and partnerships that promote stable housing. Public policy, the final level, encompasses current city, state, and federal policies as well as housing and health advocacy. Figure 1 highlights the conceptual model that guided the review of the literature and subsequent analysis and synthesis of findings.

Figure 1:

Ecological Model for Health Promotion (from McLeroy et al., 1998)

THE REVIEW

Aims

The aim of this review was to examine existing community-institutional partnerships providing health care services to people experiencing homelessness by addressing social determinants of health (SDOH) at multiple socioecological levels.

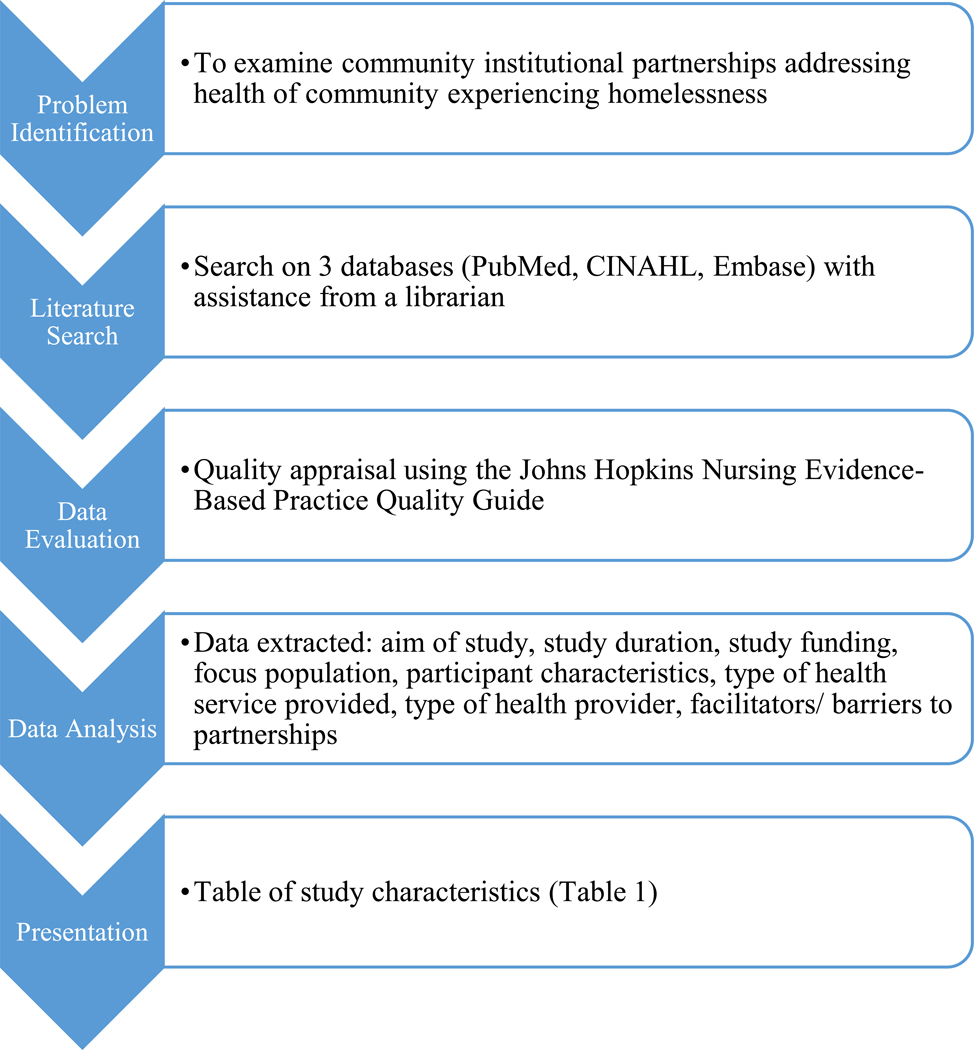

Design

This article utilized an integrative review design. To examine health care provided by community institutional partnerships, both experimental and nonexperimental studies were analyzed. The integrative review stages presented by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) were followed. First, the study team identified the purpose of the review: to examine community institutional partnerships addressing the health of communities experiencing homelessness. This aim was chosen due to the severe health disparities present in homeless populations. Much of the current evidence supports the expansion of health care delivery and the promotion of resources, but examples of this expansion are limited. While the target population, individuals experiencing homelessness, was specific, the sampling frame was broad. The literature search focusing on the intersection of health and community partnerships concerning homeless populations was conducted. For the data synthesis phase, the socioecological model (Figure 1) was used to guide data extraction.

Search methods

To identify health care services provided through partnerships for clients living in transitional housing settings, a comprehensive search of the literature was completed. The search strategy was created with the guidance of a librarian at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing. PubMed (Public/Publisher MEDLINE), CINAHL (The Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature database), and EMBASE (Excerta Medica database) were searched to identify a comprehensive set of articles relating to health care services, partnerships, and transitional housing. The following medical subject headings (MeSH) terms were used: public-private sector partnerships, community-institutional relation, community-academic, academic community, community university, university community, housing, emergency shelter, homeless persons, shelter, and transitional housing. Articles published until November 2021 were eligible for inclusion.

Additional inclusion criteria included a population sample of people experiencing homelessness or living in transitional housing, health services being delivered by a partnership (i.e. academic community partnership, public/private institution partnership), and direct provision of health care services in a housing setting (Table 2). Exclusion criteria included shelters and programs only serving children and services being provided outside the US. All references were uploaded to Covidence, a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of systematic literature reviews (Covidence, 2022). Title and abstract screening followed by full text review were independently conducted by two doctoral students. Disagreements between researchers that arose from the title and abstract screening process were resolved through discussion. Included studies were then extracted and quality assessment was completed following the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Quality Guide.

Table 2:

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| • Discuss partnership between 2 different organizations • Sample population of people experiencing homelessness or living in transitional housing • Health services delivered by a partnership (i.e. Academic community partnership, public/private institution partnership) • Direct provision of health care services in a housing setting. |

• Shelters and programs only serving children • Services provided outside the U.S. |

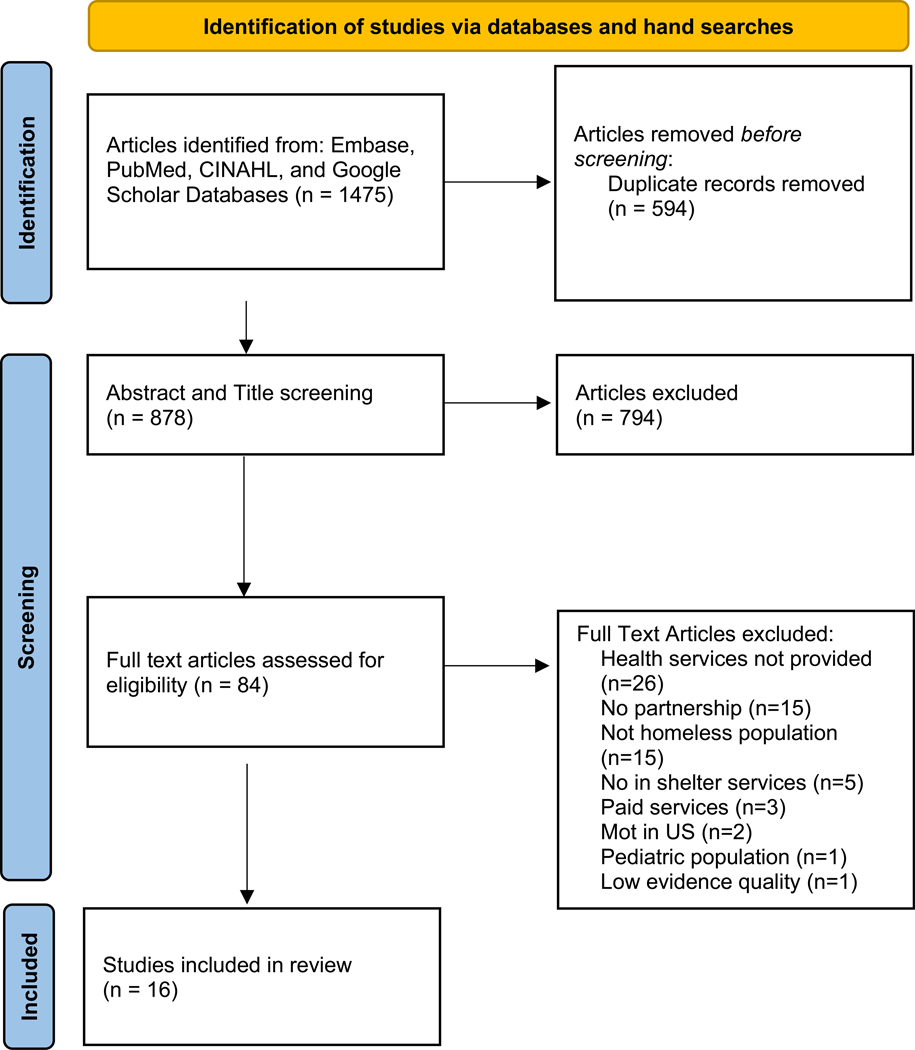

Search outcome

The search yielded a total of 1475 articles from three databases. After the exclusion of duplicates (n=594), 878 articles were eligible for title and abstract screening. A resulting 84 articles were assessed for eligibility through full text review. Articles were excluded for the following reasons: health services not provided (n=26), no partnership (n=15), not homeless population (n=15), No in shelter services provided (n=5), paid services only (n=3), not located in the US (n=2), pediatric population (n=1), low evidence quality (n=1). A final total of 16 articles were included in the review. Figure 2 highlights the search outcomes in further detail.

Figure 2:

PRISMA Flow Diagram (Page et al., 2021)

Quality appraisal

The quality of the sixteen included articles was appraised by two researchers using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Quality Guide, which evaluates the methodological quality of studies based on three levels that are determined by different three different levels: high, good, and low quality. Determinations of different levels of quality are made based on the consistency of study results, sufficient sample size, adequate control, definitive conclusions, consistent recommendations, and reference to scientific evidence. In the case of discrepancies with quality appraisal judgement by the two researchers, the researchers met to discuss differences in opinion before reaching a consensus. One article with low evidence quality was not included in the study.

Data abstraction

Data were abstracted by two independent researchers through a pre-designed template. The predesigned template was created by the researchers prior to abstraction and edited to encompass relevant items including the study title, study aim, study design, duration of services, funding source, focus population, population demographics, method of participant recruitment, number of total participants, type of health services provided, health care providers, partnership type, program/intervention outcomes, facilitators of partnerships, barriers to partnerships, future recommendations, and the social determinants of health addressed by the community institutional partnerships. Upholding abstraction rigor, the abstracted data was checked by each researcher independently.

Synthesis

All of the included articles discussed the types of care providers and organizations involved in the partnerships. Thus, partnerships were classified based on types of care providers, and health care services made possible through partnerships were assessed using the ecological level of partnership described by the Ecological Model of Health Promotion (Figure 1).

RESULTS

After full article screening, 16 articles were included in the final review. Many articles (n=12) were rated with level 5 on the evidence hierarchy scale because they were either program evaluations or case reports. Half (n=6) of the level 5 studies had high quality and the other half were rated with good quality because they only exhibited consistent results in a single setting as opposed to multiple settings. The remaining studies (n=4) had level 2 of evidence and consisted of quasi-experimental studies and had high quality evidence by having consistent and generalizable results, sufficient sample size, discussed confounding variables and ways to remediate their effects, and consistent recommendations based on thorough literature reviews.

All studies included in this review took place in the U.S., including Hawaii. Study settings were broad, including rural towns in the Midwest (Dahl 1993) and North Carolina (Yaggy 2006), as well as urban cities in Ohio, New York, Massachusetts, and Texas (Gerberich 2000; Batra 2009; Lincoln 2009; Owusu 2012). The samples in the included studies were also diverse, ranging from health professional students involved in the partnerships rather than the patient population that was served (Arndell 2014; Batra 2009; Dahl 1993; Gerberich 2000), people experiencing homelessness that were provided with health services (Corbin 2000; Lashley 2007; Ragavan 2016; Schick 2020; Yaggy 2006), and both the health professionals involved and the people that received the health services (Lashley 2008; Schoon 2012). Two studies did not specify the number of people served, but provided overall patient encounters, which included multiple visits by the same individual (Omori 2012; McCann 2010). In general, patient sample sizes varied, ranging from 28 to 2000 people experiencing homelessness and student samples ranging between 18–140 students.

The types of partnerships discussed in the articles were academic-community partnerships (n=11) and hospital-community partnerships (n=5). Studies on academic-community partnerships frequently discussed community-service curricula designed to both improve nursing and medical students’ learning in addition to improving the health of people experiencing homelessness within the community. Two articles on academic-community partnerships were program descriptions that did not discuss patient outcomes (Dahl, Gustafson, & McCullagh, 1993; Mund et al., 2008).

Out of the 16 studies, 13 described sustained partnerships that continued at the time of publication and three studies discussed pilot studies or partnerships between organizations and facilities that only occurred at one time (Lashley, 2008; Owusu et al., 2012; Schick et al., 2020). The types of health services provided to homeless populations included preventative care, mental health, acute and chronic medical care, oral health, foot care, HIV care, case management, medication prescriptions, and health education (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author | Partnership Type/ Members | Study Population | Health Providers | Types of Health Services Provided | Outcomes | EMHP Level/ Social Determinants Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arndell 2014 |

Academic & community University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque Health Care for the Homeless |

Men experiencing homelessness in Albuquerque, New Mexico | Medical students, physicians, pharmacy students, pharmacist | Individualized treatment plans by pharmacy and medical students, health education, street outreach | Continued involvement in providing care to homeless populations post-graduation; overall satisfaction by students |

Intrapersonal factors: access to health education/ knowledge Institutional factors: limited access to health services |

| Batra 2009 |

Academic & community Columbia University Medical Center, St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in West Harlem |

People experiencing homelessness in Northern Manhattan, New York | Medical students | Medical history, physical exam, point of care testing (blood glucose, pregnancy tests, urine dipstick, fecal occult blood), written prescriptions, disbursement of medications, lifestyle and health care maintenance counseling, psychiatric screening, direct referrals to physicians | Strengthened student commitment to working with the underserved, increased number of patients, patient visits, follow-up rates | Institutional factors: limited access to health services |

| Corbin 2000 |

Hospital & community Catholic Charities Housing Opportunities, Humility of Mary Housing Inc., St. Elizabeth Health Center |

Healthcare for Caritas Community residents in Youngstown, Ohio | Nurse and physician | General health services provided by the nurse and physicians | Overview of project; outcomes not specified | Institutional factors: homelessness, limited access to health services |

| Dahl 1993 |

Hospital & community Public Health Department, Department of Social Services, Veterans Administration Hospital |

People experiencing homeless in a rural Midwest town | Nurse, Physician, Resident, dentist, social worker | Health assessment, diagnosis and treatment of acute illnesses and uncomplicated chronic conditions, health education, health screening and immunization, medications, social work evaluation | Focus on model development; outcomes not specified |

Intrapersonal factors: access to health education/ knowledge Institutional factors: limited access to health services Community factors: community support |

| Gerberich 2000 |

Academic & community University of Akron, inner city mission |

Men from a city mission in Akron, Ohio experiencing homelessness | Community health nursing students | Blood pressure measurement, referral to nearby healthcare resources, identification of health concerns, health education | Improved access and self-esteem as stated by patients; service-learning opportunities, autonomy, satisfaction from nursing students |

Intrapersonal factors: access to health education/ knowledge Institutional factors: limited access to health services; economic instability |

| Lashley 2007 |

Academic & community Local research university, inner city mission, city health department |

609 residents in a inner-city mission enrolled in a residential addiction recovery program | Nursing students | TB symptom and HIV risk assessments, TB education program focused on risk factors, methods of transmission, and ways of preventing and controlling spread of tuberculosis |

282 residents received PPD screenings and 327 residents received TB symptom assessments. 30 people were referred for TB treatment and 90% of referred initiated treatment. There was a 33% increase in treatment completion rates compared to a local city health department (11%) | Institutional factors: limited access to health services |

| Lashley 2008 |

Academic & community University dental and nursing schools, inner city mission, local dental care providers |

Residents of an inner-city mission enrolled in a residential addiction recovery program | Nursing students, dental students, residents | Oral screening, health services, education on oral hygiene, oral cancer, basic nutrition | 279 residents received oral health education, 203 screened for oral health problems, and all clients who screened received oral health care |

Intrapersonal factors: access to health education/knowledge Institutional factors: limited access to health services |

| Lincoln 2009 |

Hospital & community Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts Department of Mental Health |

18 Dudley Inn residents | Physician; case managers | Mental health services, substance abuse treatment, referrals to services, and primary care services | Improved housing trajectory, level of engagement, increased connection to services, social networks, and/or supports in the community | Institutional factors: homelessness, limited access to health services |

| McCann 2010 |

Academic & community Marillac House, Rush University Colleges of Nursing, Medicine, and Health Sciences |

Clients of Marillac House (social service agency) in East Garfield Park, Illinois | Nursing students, nursing faculty, residents | Immunizations, physical exams, health screenings, management of acute and chronic illness (hypertension, asthma), referrals to a primary care provider or medical specialists | More than 200 health care visits have been provided to eligible children and adults |

Institutional factors: homelessness, limited access to health services Community factors: community support |

| Mund 2008 |

Hospital & community CitiWide Harm Reduction, Montefiore Medical Center |

Unstably housed substance users with or at-risk for HIV infection | Nurse; physician; community health worker | Medical outreach, comprehensive HIV care, acute care, gynecological care, vaccinations, Hepatitis C Virus testing, assessment, treatment; HIV counseling, testing; referrals to specialty care, health education, supportive counseling, escorts, care coordination, referrals to social services | Program description; outcomes not specified | Institutional factors: limited access to health services; transportation |

| Omori 2012 |

Academic & community John A. Burns School of Medicine, homeless shelters in O’ahu |

Over 2000 residents of homeless shelters in O’ahu | Physicians; Residents; medical students, pharmacist | Acute and chronic medical care, health maintenance and preventive health services, minor procedures, vaccinations, TB testing, laboratory testing and diagnostic imaging, health education, dental assessments, free medications for the uninsured, management of complex health problems, coordination or specialty appointments, lab visits, social work | 7600 patient encounters, improved health quality, decreased hospitalization rates and emergency department visits, high patient satisfaction. Improved clinical skills, attitudes towards caring for the homeless, promotion of future volunteerism, increased patient advocacy skills, knowledge of systems-based practice principles, resource allocation, and cost containment for students |

Intrapersonal factors: limited access to health education/knowledge Institutional factors: access to health services; economic instability Community factors: community support |

| Owusu 2012 |

Academic & community Standford University School of Medicine, the Mission of Yahweh |

19 residents at the Mission of Yahweh, a homeless shelter in Houston, Texas | Physician, medical students | Mental health screenings | Increased scores on knowledge of psychotropic medications (27%), principles of cultural competence (17%), and diagnostic criteria (25%) by shelter staff and clergy based on results of the pre-/post-test questionnaire | Intrapersonal factors: access to health education/knowledge |

| Ragavan 2016 |

Academic & community Transitional housing program, academic medical center |

46 female intimate partner violence survivors residing in a transitional housing program in Northern California | Pre-health, medical, public health, nursing, social work, psychology students; medical residents; nurses, physicians, social workers | Health education (nutrition, communication, health, mindfulness, stress management) | 80% of women attended at least 1 workshop and responded positively to the curriculum. Workshop facilitators found the experience rewarding both professionally and personally | Intrapersonal factors: access to health education/knowledge |

| Schick 2020 |

Academic & community University of Texas, federally qualified health centers, Houston Health Department, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, Texas A&M Center for Population Health and Aging |

28 people in permanent supportive housing in Houston, Texas | Health professionals, certified diabetes educators, community health workers | Diabetes self-management program consisting of an orientation followed by 6 educational sessions 2 hours in length | Significant increase in diabetes knowledge, self-efficacy, and foot self-care. The average hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of the participants significantly decreased from 8.86 to 6.88 |

Intrapersonal factors: access to health education/knowledge Interpersonal factors: social support |

| Schoon 2012 |

Academic & community Inner-city homeless shelter, local university’s department of nursing |

389 clients residing at a homeless shelter in Minnesota | Nurse; nursing students | Foot assessments, foot soak and massage with essential oils, new stockings, health teaching, and referrals to podiatrists. | The foot care clinic added capacity to the shelter clinic services, provided addition of a podiatrist, nutritionist, and diabetic educator for follow-up appointments. Increased participation by shelter clients, shelter guests’ recruitment of other patients. Increased knowledge of causes and conditions of homelessness, clinical experience for students | Institutional factors: limited access to health services |

| Yaggy 2006 |

Hospital & Community Lincoln Community Health Center, Department of Social Services |

103 seniors living in subsidized housing in Durham, (from table, not text) |

Primary care providers, clinical social workers, geriatric psychiatrist, pharmacist | Primary care (physical assessments, medication review, chronic-disease management), mental health, case management, laboratory and radiology services, discounted medications | 97% of patients with hypertension measured their blood pressure in the past year; 79% had stable blood pressure (140/90). 76% of patients with diabetes had HgA1c taken in past year and 84% of them had it controlled | Institutional factors: limited access to health services; transportation; economic instability |

Health services were provided by a wide variety of different care providers in both the medical and psychosocial fields of practice. A few partnerships consisted of nurses and nursing students as main health care providers (n=3), some partnerships comprised of a team of nurses and physicians (n=2), others had mainly medical students providing care services (n=2), as well as a combination of pharmacists and medical students (n=2) and physicians and case managers (n=1). However, many studies (n=6) described interdisciplinary teams of health care providers that included nursing/medical students, nurses, physicians, social workers, psychiatrists, nutritionists, and pharmacists.

In the studies, three main types of outcomes were measured to determine the efficacy and success of partnerships aimed at improving the health of homeless populations. Outcome measures were either patient-centered (n=6), student-centered (n=4), or included both patient- and student-centered outcomes (n=3). Three articles did not discuss any outcomes that resulted from partnerships between organizations, mainly because they provided brief program descriptions (Corbin, Maher, & Voltus, 2000; Dahl et al., 1993; Mund et al., 2008). Student-centered outcomes included satisfaction with experiences providing care (Arndell, Proffitt, Disco, & Clithero, 2014), commitment to serving the underserved (Batra et al., 2009; Schoon, Champlin, & Hunt, 2012), and increases in psychiatric knowledge (Owusu et al., 2012) and causes of homelessness (Schoon et al., 2012). Outcomes that focused on the patient population consisted of increases in health care visits and screenings (Lashley, 2007, 2008; McCann, 2010), improved knowledge on topics of diabetes and oral health (Lashley, 2008; Schick et al., 2020), management of chronic symptoms of hypertension and diabetes (Yaggy et al., 2006), housing status, and connection to health services (Lincoln et al., 2009). Studies that examined both patient and student outcomes measured decreased hospitalization rates, patient satisfaction, improved clinical skills, and improved self-esteem of both patients and care providers. All studies on partnerships between academic institutions and other organizations revealed that students’ experiences of providing care to people experiencing homelessness were valuable and informed their outlook on care provision in community settings. Further, the partnerships improved the health of the population by increasing the utilization of health services and screenings while decreasing rates of hospitalizations. Two studies in particular utilized community outreach programs to expand their reach of services to not only people within transitional housing settings/shelters but also homeless people in the streets of communities, which proved successful (Batra 2009; Lincoln 2009).

Many partnerships discussed in the articles addressed social determinants of health SDOH) for the homeless population at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, and community levels presented in the socioecological model by McLeroy et al. (1988) (Table 1). Intrapersonal level factors, such as knowledge and access to health services, were provided through individual and group education sessions to guide and inform individual health behaviors (Arndell 2014; Dahl 1993; Gerberich 2000; Lashley 2008; Omori 2012; Owusu 2012; Ragavan 2016; Schick 2020). Interpersonal level determinants of health addressed by partnerships mainly consisted of social support, although perceived social support did not have a significant increase following a diabetes self-management program (Schick 2020). Several institutional-level SDOHs, including limited access to health services, homelessness, economic instability, and barriers to transportation were mitigated by community partnerships through delivery of free services and provision of onsite services at temporary shelters (Mund 2008). At the community level, shared collaborative efforts among multiple organizations increased public awareness of the needs of people experiencing homelessness among larger communities (Dahl 1993; Omori 2012). Two partnerships formed health clinics that integrated health services into existing systems serving the homeless population (Lincoln et al., 2009; McCann, 2010). None of the articles in the review discussed SDOH at the policy and societal levels that addressed the needs of people experiencing homelessness. However, health professional students providing care to homeless populations demonstrated increased awareness of social injustices among marginalized populations, which could potentially influence policy formation in the future (Schoon 2012). Greater efforts are needed to improve health promotion programs at the public policy level to promote universal access to health services for people who experience homelessness.

DISCUSSION

Partnerships between different organizations can remove barriers to care and promote the health of people who experience homelessness. While many studies (n=9) included health outcomes of patients who received health services made possible through community partnerships, strategies measuring the efficacy and impact of partnerships are premature. All studies measured health improvement immediately after health services were provided, and the long-term impact of available services is not discussed in the current literature. Although there are barriers to obtaining long-term data for people experiencing homelessness due to the varying length of stays people may have at shelters, there is a need for larger quantitative studies that examine the health outcomes of people who use the health services made possible by community partnerships. This will allow partnership stakeholders to assess the impact and efficacy of partnerships to inform program development that meet the complex health needs of people who experience homelessness.

All the studies included in the review found that community institutional partnerships improve the health of people who experience homelessness by removing barriers and improving access to health services. However, the sustainability of such programs must be appraised to ensure that programs and services are available to homeless populations long-term. Many of the partnerships outlined in this review were funded by private foundations, universities, or grants, and their operations were contingent upon continued funding (Dahl et al., 1993). In fact, a clinic adopted into a temporary shelter faced challenges with obtaining enough funding from the shelter to continue maintenance of the health clinic to provide continued services to its clients (McCann, 2010). To promote future partnerships and maintain partnerships that present care services to homeless populations, larger governmental institutions must also prioritize these efforts to make them available across the country.

Only one out of 16 articles described partnerships that provided health services to homeless survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) (Ragavan, Karpel, Bogetz, Lucha, & Bruce, 2016). This is a significant gap in the literature because many survivors of violence are homeless (Aratani, 2009; Jagasia et al., 2022). Further, IPV survivors are prone to many negative physical and mental health problems that occur because of their abusive partner (Stockman, Hayashi, & Campbell, 2015). The dearth of literature that examines health services made available to IPV survivors through institutional partnerships indicates a need for future research that includes survivors of violence who experience homelessness to ensure they have access to health services that accommodate their complex health needs.

A limitation of this review is that all studies took place in the U.S. This restricts the generalizability of findings to countries outside of the U.S. However, the articles included both women and men (n=16), which may be representative of the U.S. population. The articles also discussed partnerships that primarily created service-learning opportunities for students in health professional programs (Arndell 2014, Batra 2009, Owusu 2012, Schoon 2012). This indicates that community institutional partnerships are frequently initiated to meet school curriculums for students rather than with the singular goal to provide health services to vulnerable populations. Community institutional partnerships are critical, particularly at state levels to decrease disparities in access to care services by region. Another limitation of this review is that articles were not limited by publication year to include as many articles as possible. This resulted in including an article that was published in 1993, which may be archaic and unrepresentative of current practices with health infrastructures (Dahl et al., 1993). However, the article was deemed valuable because it presented a model that assisted the development of future collaborative partnership models.

CONCLUSION

This review identified 16 studies that described partnerships aimed at improving the health of people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. While all studies found that the health services and education made possible through partnerships improved the health and knowledge of the people they served, elaborate long-term evaluation methods are lacking. Future research must focus on using extensive measures to evaluate the efficacy of current partnerships and push for systemic changes such as greater availability of financial systems that decrease health service fees and increase the availability of care services to people that experience homelessness.

Study implications

Nursing practice prioritizes the provision of holistic care to patients and is essential to tackle health disparities faced by people who experience homelessness. Nurses play an important role in the health team and are the backbone of strong partnerships that bring health care services to homeless populations. Globally, over 1.6 billion people live in inadequate housing conditions (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2020). While the articles discussed the SDOH that were addressed by community institutional partnerships at the intrapersonal, organizational, and community levels, none of the studies discussed the impact of partnerships at the public policy level. To improve the health of those with unstable housing, long-term findings on the implications of health services provided to people who experience homelessness are essential to creating effective interventions that improve the health of this population. Future research must shift focus to larger policy implications and financial structures that influence service utilization to further sustain partnerships. Community institutional partnerships must also direct greater focus on the welfare of people who experience homelessness by evaluating how they are affected by health services, rather than mainly seeking to understand the experience of health care staff and students serving the community.

Figure 3:

Integrative Review Steps (from Whittemore & Knafl, 2005)

Summary Statement.

What Is Already Known:

People who experience homelessness encounter countless health challenges

Many factors limit health care access for people who experience homelessness

Intersections between social determinants of health, social and legal systems, and policies that promote health care access and engagement must be considered when promoting the health of people experiencing homelessness in the United States

What This Paper Adds:

Types of community institutional partnerships (CIP) that address health needs of homeless populations include academic-community partnerships (n=11) and hospital-community partnerships (n=5)

Outcome measures determining efficacy of CIPs were patient-centered (n=6), student-centered (n=4), or included both patient- and student-centered outcomes (n=3).

All the studies found that CIPs improved the health of people experiencing homelessness by removing barriers and improving access to health services

Implications For Practice/Policy:

Long-term findings on the implications of health services provided to people who experience homelessness are needed

Future studies must assess the impact of community partnerships at the public policy and societal levels

Community institutional partnerships must direct focus on the welfare of people who experience homelessness by evaluating how they are affected by health services rather than evaluating the experiences of health care staff and students serving the community

Acknowledgements:

E. Jagasia’s time spent on writing this article was supported in part by the National Institutes of Child Health and Development (T32-HD 094687), Interdisciplinary Research Training on Trauma and Violence.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).

No Patient or Public Contribution

The results of the systematic review were solely from the articles reviewed and do not include information from patients, service users, caregivers, or members of the public.

Contributor Information

Jennifer J. LEE, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing.

Emma JAGASIA, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing.

Patty R. WILSON, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing.

References

- Aratani Y. (2009). Homeless children and youth causes and consequences. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02/107-110.pdf.

- Arndell C, Proffitt B, Disco M, & Clithero A. (2014). Street outreach and shelter care elective for senior health professional students: An interprofessional educational model for addressing the needs of vulnerable populations. Education for Health (Abingdon, England), 27(1), 99–102. 10.4103/1357-6283.134361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra P, Chertok JS, Fisher CE, Manseau MW, Manuelli VN, & Spears J. (2009). The columbia-harlem homeless medical partnership: A new model for learning in the service of those in medical need. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 86(5), 781–790. 10.1007/s11524-009-9386-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen RC (2004). Community psychiatry education through homeless outreach. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 55(8), 942. 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin B, Maher D, & Voltus N. (2000). Community networks. Partnerships between Catholic charities and Catholic healthcare organizations. Caritas Communities, Youngstown, OH. Health Progress (Saint Louis, Mo.), 81(2), 58–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl S, Gustafson C, & McCullagh M. (1993). Collaborating to develop a community-based health service for rural homeless persons. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 23(4), 41–45. 10.1097/00005110-199304000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson C, Murry VM, Meinbresse M, Jenkins DM, & Mindtrup R. (2016). Using the social ecological model to examine how homelessness is defined and managed in rural East Tennessee. Nashville: National Health Care for the Homeless Council. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2018. The 2017 annual homeless assessment report (ahar) to congress. part 1: point-in-time estimates of homelessness. Washington: US Department of Housing and Urban Development. [Google Scholar]

- Ervin E, Poppe B, Onwuka A, Keedy H, Metraux S, Jones L, … & Kelleher K. (2022). Characteristics associated with homeless pregnant women in columbus, ohio. Maternal and child health journal, 26(2), 351–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Geddes JR, & Kushel M. (2014). The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. The Lancet, 384(9953), 1529–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez CA, Kleinman DV, Pronk N, Gordon GLW, Ochiai E, Blakey C, … & Brewer KH (2021). Practice full report: Addressing health equity and social determinants of health through healthy people 2030. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 27(6), S249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grattan RE, Tryon VL, Lara N, Gabrielian SE, Melnikow J, & Niendam TA (2022). Risk and Resilience Factors for Youth Homelessness in Western Countries: A Systematic Review. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C), 73(4), 425–438. 10.1176/appi.ps.202000133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry M, De Sousa T, Roddey C, Gayen S, Bednar TJ, Associates A, … Dupree D. (2020). The 2020 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress. [Google Scholar]

- Jagasia E, Lee JJ, & Wilson PR (2022). Promoting community institutional partnerships to improve the health of intimate partner violence survivors experiencing homelessness. Journal of advanced nursing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MM (2016). Does race matter in addressing homelessness? A review of the literature. World medical & health policy, 8(2), 139–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley M. (2007). Nurses on a mission: A professional service learning experience with the inner-city homeless. Nursing Education Perspectives, 28(1), 24–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley M. (2008). Promoting oral health among the inner city homeless: A community-academic partnership. The Nursing Clinics of North America, 43(3), 367–379, viii. 10.1016/j.cnur.2008.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln A, Johnson P, Espejo D, Plachta-Elliott S, Lester P, Shanahan C, … Kenny P. (2009). The BMC ACCESS project: The development of a medically enhanced safe haven shelter. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 36(4), 478–491. 10.1007/s11414-008-9150-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Metzger DS, Kegeles S, Strauss RP, Scotti R, … & Trotter RT (2001). What is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. American journal of public health, 91(12), 1929–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann E. (2010). Building a community-academic partnership to improve health outcomes in an underserved community. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.), 27(1), 32–40. 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mund PA, Heller D, Meissner P, Matthews DW, Hill M, & Cunningham CO (2008). Delivering care out of the box: The evolution of an HIV harm reduction medical program. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19(3), 944–951. 10.1353/hpu.0.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Care for the Homeless Council. (2019). Homelessness & health: What’s the Connection? Fact sheet. Retrieved from https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/homelessness-and-health.pdf

- National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty. (2011). “Simply unacceptable”: Homelessness and the human right to housing in the united states 2011: A report of the national law center on homelessness & poverty. Retrieved from https://homelesslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Simply_Unacceptable.pdf

- National Network to End Domestic Violence. (2018). Domestic Violence, housing, and homelessness. Retrieved from https://nnedv.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Library_TH_2018_DV_Housing_Homelessness.pdf

- Owusu Y, Kunik M, Coverdale J, Shah A, Primm A, & Harris T. (2012). Lessons learned: A “homeless shelter intervention” by a medical student. Academic Psychiatry: The Journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry, 36, 219–222. 10.1176/appi.ap.10040055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK (2020). Homelessness, housing instability and mental health: Making the connections. BJPsych Bulletin, 44(5), 197–201. 10.1192/bjb.2020.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter-OʼGrady T. (2018). Leadership advocacy: Bringing nursing to the homeless and underserved. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 42(2), 115–122. 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragavan M, Karpel H, Bogetz A, Lucha S, & Bruce J. (2016). Health education for women and children: A community-engaged mutual learning curriculum for health trainees. MedEdPORTAL, 12, 10492. 10.15766/mep\_2374-8265.10492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez NM, Lahey AM, MacNeill JJ, Martinez RG, Teo NE, & Ruiz Y. (2021). Homelessness during COVID-19: Challenges, responses, and lessons learned from homeless service providers in Tippecanoe County, Indiana. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick V, Witte L, Isbell F, Crouch C, Umemba L, & Peña-Purcell N. (2020). A community-academic collaboration to support chronic disease self-management among individuals living in permanent supportive housing. Progress in Community Health Partnerships : Research, Education, and Action, 14(1), 89–99. 10.1353/cpr.2020.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoon PM, Champlin BE, & Hunt RJ (2012). Developing a sustainable foot care clinic in a homeless shelter within an academic-community partnership. The Journal of Nursing Education, 51(12), 714–718. 10.3928/01484834-20121112-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KH, Taylor PJ, Bonner A, & Bernadette Martina Van Den Bree M. (2009). Risk factors for homelessness: Evidence from a population-based study violence and psychiatric pathologies view project the wales adoption study view project. Psychiatric Services, 60(4), 465–472. 10.1176/appi.ps.60.4.465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman JK, Hayashi H, & Campbell JC (2015). Intimate partner violence and its health impact on ethnic minority women [corrected]. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 24(1), 62–79. 10.1089/jwh.2014.4879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trejos Saucedo RF, Salazar Marchan CY, Linkowski L, Hall S, Menezes L, Liller K, & Bohn J. (2022). Homelessness in urban communities in the US: A scoping review utilizing the socio-ecological model. Florida public health review, 19(1), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RG Jr, Wall MM, Greenstein E, Grant BF, & Hasin DS (2013). Substance-use disorders and poverty as prospective predictors of first-time homelessness in the United States. American journal of public health, 103 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S282–S288. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN Habitat. (2022). Housing Rights. https://unhabitat.org/programme/housing-rights

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2020). First-ever UN resolution on Homelessness. United Nations. Retrieved September 27, 2022, from https://www.un.org/development/desa/undesavoice/in-case-you-missed-it/2020/03/48957.html#:~:text=Globally%2C%201.6%20billion%20people%20worldwide%20live%20in%20inadequate,group%20with%20the%20highest%20risk%20of%20becoming%20homeless. [Google Scholar]

- White BM, & Newman SD (2015). Access to primary care services among the homeless: A Synthesis of the literature using the equity of access to medical care framework. Journal of Primary Care and Preventative Health, 6(2), 77–87. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2150131914556122\ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, & Knafl K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of advanced nursing, 52(5), 546–553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaggy SD, Michener JL, Yaggy D, Champagne MT, Silberberg M, Lyn M, … Yarnall KSH (2006). Just for us: an academic medical center-community partnership to maintain the health of a frail low-income senior population. The Gerontologist, 46(2), 271–276. 10.1093/geront/46.2.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]