Abstract

Background

Iron‐deficiency anaemia is highly prevalent among non‐pregnant women of reproductive age (menstruating women) worldwide, although the prevalence is highest in lower‐income settings. Iron‐deficiency anaemia has been associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, which restitution of iron stores using iron supplementation has been considered likely to resolve. Although there have been many trials reporting effects of iron in non‐pregnant women, these trials have never been synthesised in a systematic review.

Objectives

To establish the evidence for effects of daily supplementation with iron on anaemia and iron status, as well as on physical, psychological and neurocognitive health, in menstruating women.

Search methods

In November 2015 we searched CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, and nine other databases, as well as four digital thesis repositories. In addition, we searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) and reference lists of relevant reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs comparing daily oral iron supplementation with or without a cointervention (folic acid or vitamin C), for at least five days per week at any dose, to control or placebo using either individual‐ or cluster‐randomisation. Inclusion criteria were menstruating women (or women aged 12 to 50 years) reporting on predefined primary (anaemia, haemoglobin concentration, iron deficiency, iron‐deficiency anaemia, all‐cause mortality, adverse effects, and cognitive function) or secondary (iron status measured by iron indices, physical exercise performance, psychological health, adherence, anthropometric measures, serum/plasma zinc levels, vitamin A status, and red cell folate) outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures of Cochrane.

Main results

The search strategy identified 31,767 records; after screening, 90 full‐text reports were assessed for eligibility. We included 67 trials (from 76 reports), recruiting 8506 women; the number of women included in analyses varied greatly between outcomes, with endpoint haemoglobin concentration being the outcome with the largest number of participants analysed (6861 women). Only 10 studies were considered at low overall risk of bias, with most studies presenting insufficient details about trial quality.

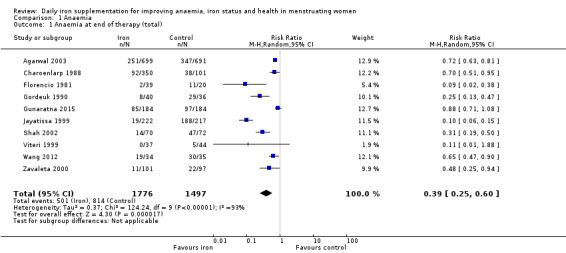

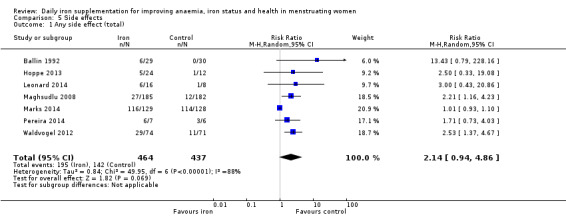

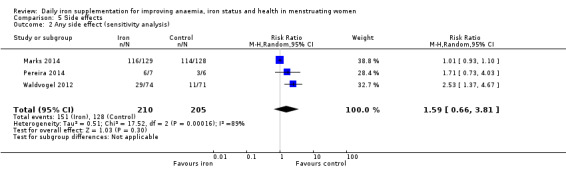

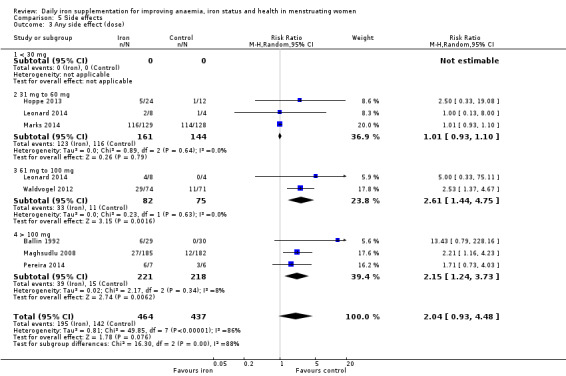

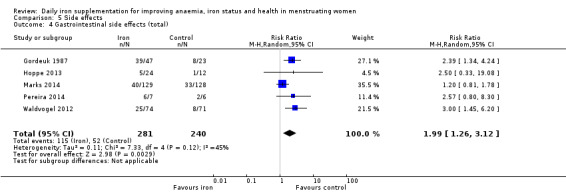

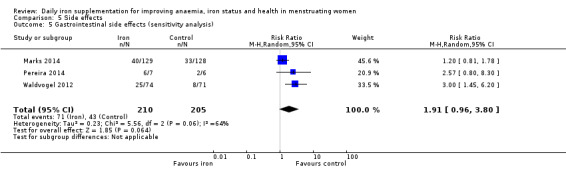

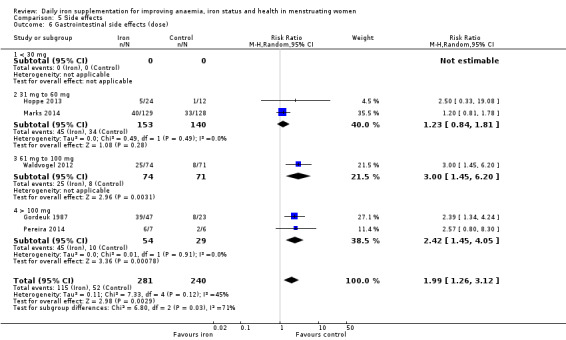

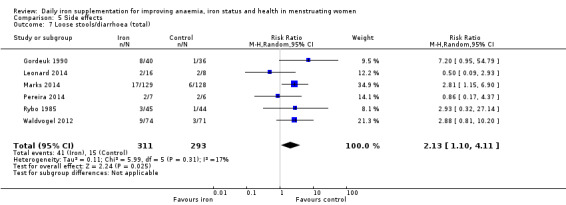

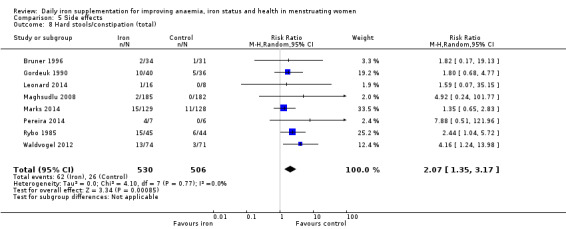

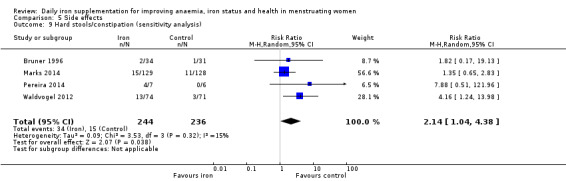

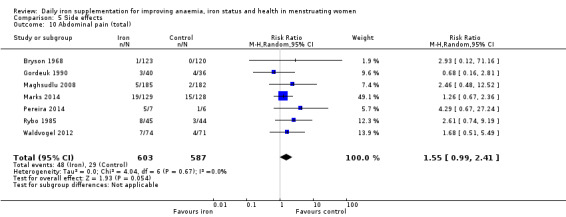

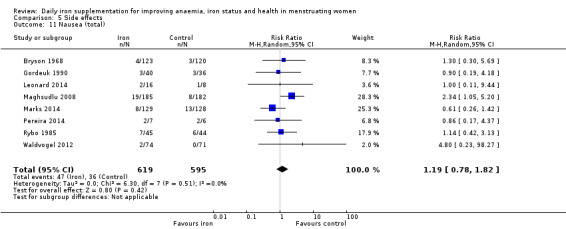

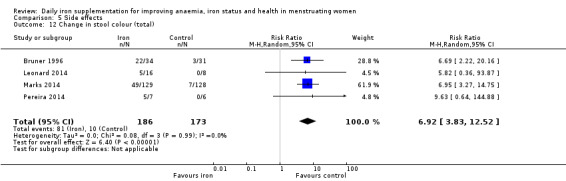

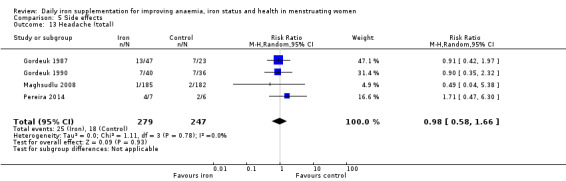

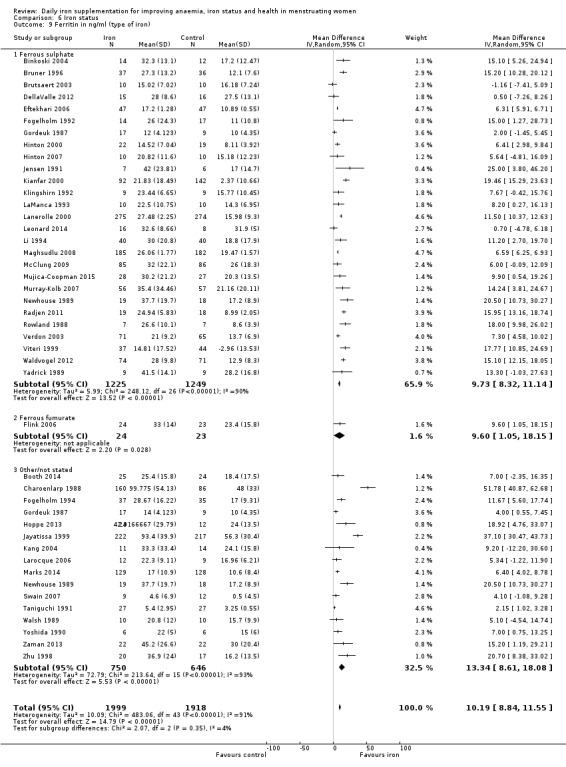

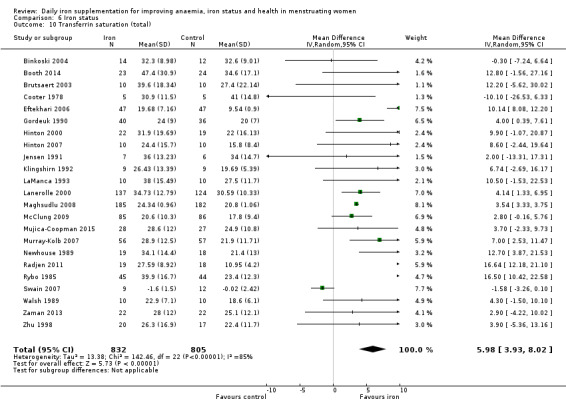

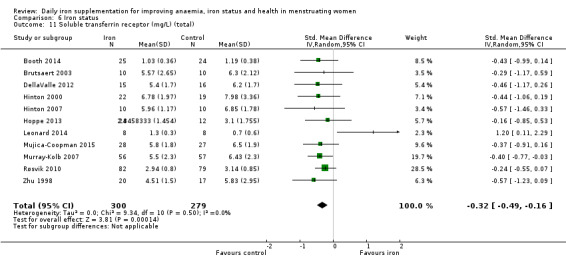

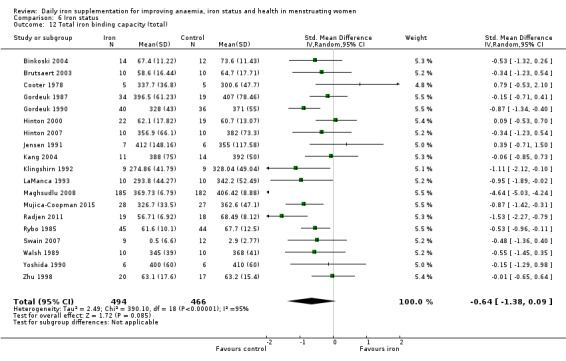

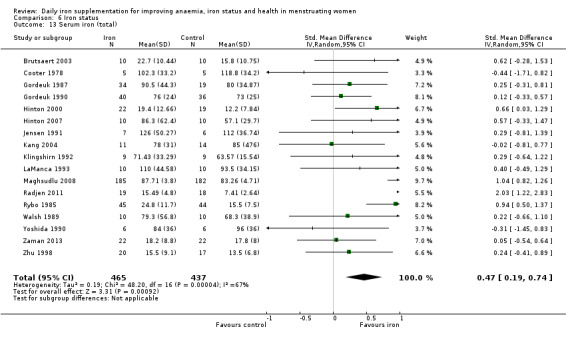

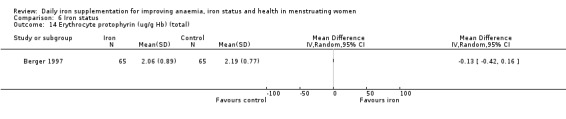

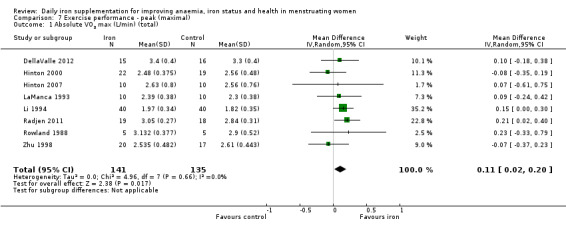

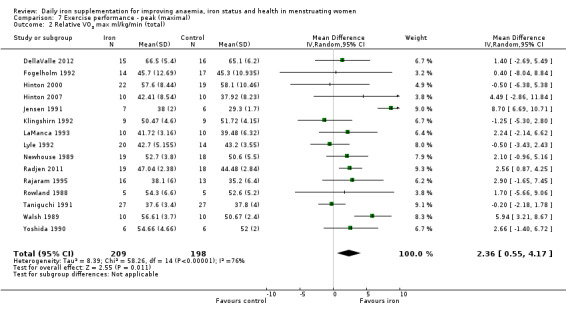

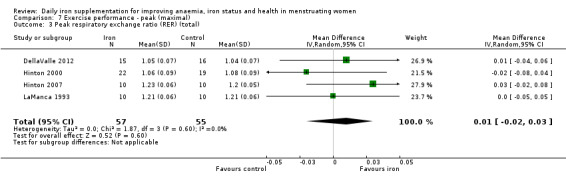

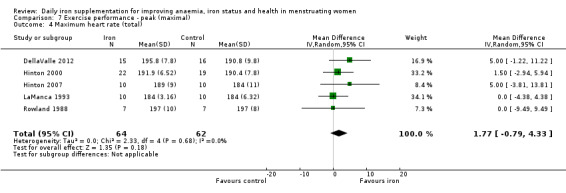

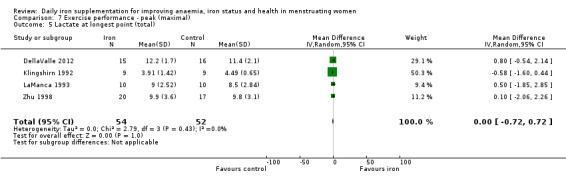

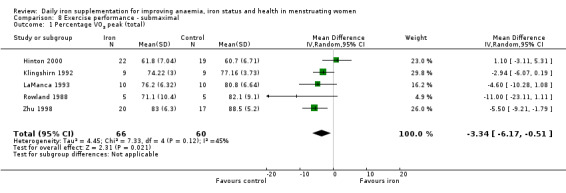

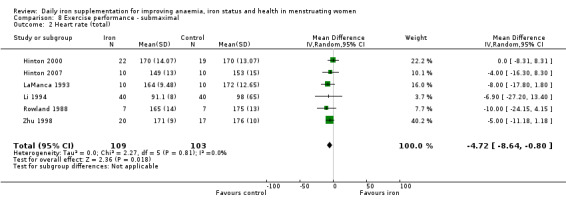

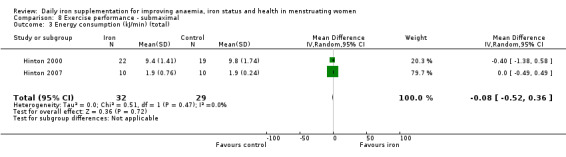

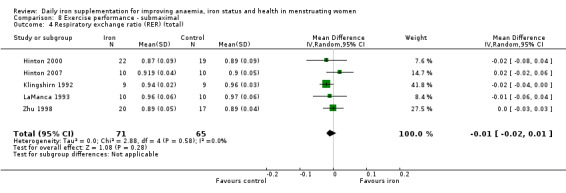

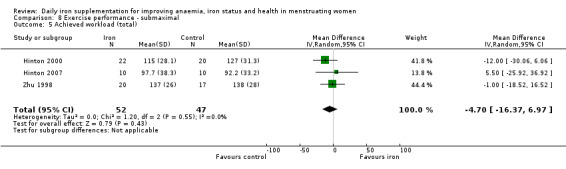

Women receiving iron were significantly less likely to be anaemic at the end of intervention compared to women receiving control (risk ratio (RR) 0.39 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25 to 0.60, 10 studies, 3273 women, moderate quality evidence). Women receiving iron had a higher haemoglobin concentration at the end of intervention compared to women receiving control (mean difference (MD) 5.30, 95% CI 4.14 to 6.45, 51 studies, 6861 women, high quality evidence). Women receiving iron had a reduced risk of iron deficiency compared to women receiving control (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.76, 7 studies, 1088 women, moderate quality evidence). Only one study (55 women) specifically reported iron‐deficiency anaemia and no studies reported mortality. Seven trials recruiting 901 women reported on 'any side effect' and did not identify an overall increased prevalence of side effects from iron supplements (RR 2.14, 95% CI 0.94 to 4.86, low quality evidence). Five studies recruiting 521 women identified an increased prevalence of gastrointestinal side effects in women taking iron (RR 1.99, 95% CI 1.26 to 3.12, low quality evidence). Six studies recruiting 604 women identified an increased prevalence of loose stools/diarrhoea (RR 2.13, 95% CI 1.10, 4.11, high quality evidence); eight studies recruiting 1036 women identified an increased prevalence of hard stools/constipation (RR 2.07, 95% CI 1.35 to 3.17, high quality evidence). Seven studies recruiting 1190 women identified evidence of an increased prevalence of abdominal pain among women randomised to iron (RR 1.55, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.41, low quality evidence). Eight studies recruiting 1214 women did not find any evidence of an increased prevalence of nausea among women randomised to iron (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.82). Evidence that iron supplementation improves cognitive performance in women is uncertain, as studies could not be meta‐analysed and individual studies reported conflicting results. Iron supplementation improved maximal and submaximal exercise performance, and appears to reduce symptomatic fatigue. Although adherence could not be formally meta‐analysed due to differences in reporting, there was no evident difference in adherence between women randomised to iron and control.

Authors' conclusions

Daily iron supplementation effectively reduces the prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency, raises haemoglobin and iron stores, improves exercise performance and reduces symptomatic fatigue. These benefits come at the expense of increased gastrointestinal symptomatic side effects.

Plain language summary

Iron supplementation taken daily for improving health in menstruating women

Review question

What are the effects of iron, taken orally for at least five days a week, on health outcomes in menstruating women (compared with not giving iron)?

Background

Iron deficiency (a shortage of iron stored in the body) and anaemia (low levels of haemoglobin ‐ healthy red blood cells ‐ in the blood) are common problems globally, especially in women. Low levels of iron can eventually cause anaemia (iron‐deficiency anaemia). Among non‐pregnant women, around one third are anaemic worldwide. The problem is seen most commonly in low‐income countries, but iron deficiency and anaemia are more common in women in all contexts. Iron‐deficiency anaemia is considered to impair health and well‐being in women, and iron supplements ‐ tablets, capsules, syrup or drops containing iron ‐ are a commonly used intervention to prevent and treat this condition. We sought to review the evidence of iron, taken orally for at least five days per week, for improving health outcomes in non‐pregnant women of reproductive age (menstruating women).

Search data

The review is current to November 2015.

Study characteristics

We included studies comparing the effects of iron compared with no iron when given at least five days per week to menstruating women. We identified 67 trials recruiting 8506 women eligible for inclusion in the review. Most trials lasted between one and three months. The most commonly used iron form was ferrous sulphate.

Key results

We found evidence that iron supplements reduce the prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency, and raise levels of haemoglobin in the blood and in iron stores. Iron supplementation clearly increases the risk of side effects, for example, constipation and abdominal pain.

Quality of the evidence

We found high quality evidence that iron improves haemoglobin and produces changes in bowel function, but moderate quality evidence that iron reduces the prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency. Evidence of the effects of iron on other outcomes, such as abdominal pain, is of low quality. There are no data on the effects of iron on mortality in this population group.

Further definitive studies are needed to identify whether taking iron supplements orally for at least five days a week has an impact on key, health‐related outcomes.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Daily oral iron supplementation | ||||

|

Patient or population: menstruating women (non‐pregnant women of reproductive age) Settings: all settings Intervention: daily oral iron supplementation Comparison: no daily iron supplementation | ||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Anaemia at end of therapy (total), as defined by trial authors | RR 0.39 (0.25 to 0.60) | 3273 (10) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | Large effect, but downgraded 1 level for risk of bias and 1 level for inconsistency |

| Haemoglobin at end of therapy (total), g/L | MD 5.30 (4.14 to 6.45) | 6861 (51) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | ‐ |

| Iron deficiency at end of therapy (total), as defined by trial authors | RR 0.62 (0.50 to 0.76) | 1088 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | Downgraded 1 level for risk of bias |

| Iron‐deficiency anaemia at end of therapy, as defined by trial authors | ‐ | 55 (1) | ‐ | Meta‐analysis not possible |

| All‐cause mortality, over the course of the study | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured |

| Any adverse side effects (total), as defined and reported by trial authors | RR 2.14 (0.94 to 4.86) | 901 (7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | Downgraded 1 level for imprecision, and 1 level for risk of bias |

| GI side effects (total), events during study, as defined and reported by trial authors | RR 1.99 (1.26 to 3.12) | 521 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | Downgraded 1 level for risk of bias, and 1 level for imprecision |

| Loose stools/diarrhoea (total), events during study, as defined and reported by trial authors | RR 2.13, (1.10 to 4.11) | 604 (6) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High2 | ‐ |

| Hard stools/constipation (total), events during study, as defined and reported by trial authors | RR 2.07 (1.35 to 3.17) | 1036 (8) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High2 | ‐ |

| Abdominal pain (total), events during study, as defined and reported by trial authors | RR 1.55 (0.99 to 2.41) | 1190 (7) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low2 | Downgraded 1 level for risk of bias, and 1 level for imprecision |

| Cognitive function, as measured by trial authors | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Unable to combine the data in a meta‐analysis |

| CI: confidence interval; GI: gastrointestinal; GRADE: Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1Anaemia and iron deficiency are rated as moderate as, although iron benefits both outcomes, further studies are needed to more accurately quantify benefit. 2The quality of evidence for several adverse outcomes (any adverse effect, GI side effects and abdominal pain) were deemed low due to insufficient numbers to determine the true effect of intervention with wide CIs. Diarrhoea and constipation had similar participant numbers, however, the magnitude of the difference between intervention and control arms were larger.

Background

Description of the condition

Over 1.6 billion people worldwide have anaemia, a condition in which haemoglobin production is diminished. Women of menstruating age account for approximately a third of all cases of anaemia across the globe (WHO/CDC 2008). The most recent estimates suggest that 29% of non‐pregnant women worldwide are anaemic (Stevens 2013). Iron deficiency is believed to contribute to at least half the global burden of anaemia, especially in non‐malaria‐endemic countries (Stoltzfus 2001). Iron deficiency is thus considered the most prevalent nutritional deficiency in the world.

Iron deficiency occurs following negative iron balance. As body iron stores are exhausted, the production of red blood cells is impaired, and finally iron‐deficiency anaemia results (Suominen 1998). The major causes of negative iron balance include inadequate dietary iron intake (due to consumption of a diet with a low overall or bioavailable iron content); increased losses of iron due to chronic blood loss (in women, due to menstruation and exacerbated in cases of heavier menstrual bleeding, and by intestinal hookworm infection in individuals living in endemic settings (Hotez 2005)); and increased iron requirements (e.g. during growth or pregnancy). Low dietary iron intake and bioavailability are considered key contributors to the burden of iron deficiency. This is especially so in populations consuming diets that are low in meat sources and high in cereals such as wheat, rice, maize and millet, which are rich in phytates, compounds that bind to iron in the meal preventing its absorption (Sharpe 1950). Other dietary components such as tannins (found in tea) and calcium (contained in milk products) also inhibit iron absorption.

Women beyond menarche and prior to menopause are at especially high risk of iron deficiency due to menstrual blood losses. The onset of menstrual blood losses accompanied by rapid growth, with an associated expansion of red cell mass and tissue iron requirements, means adolescent girls have a particularly high iron need compared with their male counterparts. If this is compounded by inadequate dietary iron intake, they may be at especially high risk of iron deficiency (Dallman 1992). Other important causes of iron deficiency in women include intestinal malabsorptive conditions such as coeliac disease, chronic blood losses due to menorrhagia from uterine pathologies (such as fibroids), frequent blood donation, and benign and malignant gastrointestinal lesions (Goddard 2011). Iron deficiency, with and without anaemia, has also been noted to be prevalent among female athletes and is thought to be due to diets deficient in iron, increased losses due to gastrointestinal tract bleeding, and reduced iron absorption due to subclinical inflammation (Peeling 2008). The risk of iron deficiency may be modified by genetic factors such as inheritance of genes associated with haemochromatosis and polymorphisms in the TMPRSS6 gene (Chambers 2009).

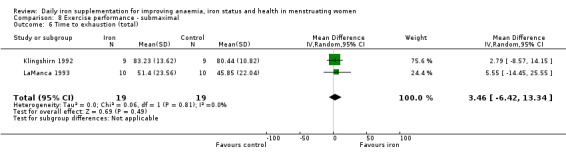

As well as being critical to the production of haemoglobin, iron has a critical role in many other aspects of human physiology as it is involved in a range of oxidation‐reduction enzymatic reactions in the muscle and nervous tissue (Andrews 1999), as well as other organs. Iron deficiency and iron‐deficiency anaemia have been associated with a range of adverse physical, psychological, and cognitive effects. Animal models suggest a role for iron in brain development and function, with iron depletion being associated with dysregulated neurotransmitter levels (Lozoff 2007), and some, but not all, clinical studies have shown associations between iron supplementation and improvement in cognitive performance (Murray‐Kolb 2007) and mood and well being, with a reduction in fatigue (Verdon 2003). Observational studies have suggested that iron deficiency in the absence of anaemia impairs exercise performance in women (Scholz 1997), while some, but not all, interventional studies of iron supplementation among the same population have shown variable improvements in maximal and submaximal exercise performance (Brownlie 2002; LaManca 1993), endurance (Brownlie 2004; Hinton 2000), and muscle fatigue (Brutsaert 2003). There may also be associations between iron status and haemoglobin concentrations and work productivity (Li 1994: Scholz 1997; Wolgemuth 1982). When anaemia is severe, it may cause lethargy, fatigue, irritability, pallor, breathlessness and reduced tolerance for exertion.

Alleviation of iron‐deficiency anaemia among menstruating women is thus considered a major public health priority, both to improve their existing health status and to enhance their health in preparation for future pregnancies (WHO 2009).

Other causes of anaemia important to distinguish from iron deficiency include anaemia of chronic disease (associated with inflammation, which causes iron to be withheld from erythropoiesis (the process by which red blood cells are produced)), functional iron deficiency (associated with renal impairment), genetic conditions of the red cell (haemoglobin, enzymes and membrane), and infectious diseases (including malaria).

Description of the intervention

Strategies to improve iron intake and alleviate iron‐deficiency anaemia include mass and point‐of‐use fortification of foods with iron; dietary diversification to increase iron intake, absorption and utilisation; iron supplementation; and antihelminthic treatment. Supplementation is probably the most widespread intervention practiced clinically and in public health.

Oral iron supplementation, administered once a day or more frequently, is the standard clinical practice of many physicians in the treatment of iron deficiency in women (Goddard 2011). Daily iron and folic acid supplementation for three months should be considered for the prophylaxis of iron deficiency in populations where the prevalence of anaemia exceeds 40% (WHO/UNICEF/UNU 2001). In addition to its haematological effects, the use of folic acid during the periconceptional period helps prevent the risk of neural tube defects in babies (WHO/UNICEF/UNU 2001).

Iron is generally administered as a salt compound in a tablet, capsule, liquid or dispersible formulation. The most commonly prescribed salts are ferrous sulphate, fumarate, and gluconate (Pasricha 2010). Ferrous sulphate is perhaps the most commonly used of these interventions. Iron formulations are commonly combined with vitamin C to improve absorption, or folic acid to improve child outcomes when used before or during pregnancy. Commonly reported side effects of iron supplements include gastrointestinal disturbances (especially constipation and nausea) and dark stools. In those using liquid formulations, tooth staining can occur. Slow or sustained‐release formulations in which iron is surrounded by a coating, aim to alleviate gastrointestinal side effects by delaying delivery of iron to a more distal point in the gastrointestinal tract, but their efficacy has been questioned. Thus, compliance to daily oral iron interventions due to adverse events can be a critical limiting factor to their effectiveness.

How the intervention might work

Iron is absorbed by intestinal cell luminal and basal transporters, bound to proteins and transported to the bone marrow, muscle and other tissue, where it is taken up by specific receptors and used for biological functions or stored (Andrews 1999). Textbooks advise that in an iron‐deficient anaemic individual, haemoglobin concentrations should rise by 1 g/dL per week, with early evidence of red blood cell formation discernible in the peripheral blood after 72 hours of supplementation (Mahoney 2011).

There is an inverse relationship between iron status and the ability to absorb iron. Iron deficiency induces changes in intestinal iron transport that can double absorption of iron from the diet (Thankachan 2008). Thus, as with dietary sources of iron, absorption from supplements depends on the baseline iron status of the individual and the co‐consumption of iron absorption enhancers (such as vitamin C, other acidic foods, and meat) and inhibitors (calcium, phytates and tannins) (Hurrell 2010; Sharpe 1950).

As mentioned above, the ubiquitous presence of iron in the human body is such that its deficiency impairs a number of physiological functions and iron supplementation may thus benefit physical, psychological and cognitive health. Improvements in haemoglobin and myoglobin concentrations may ensure adequate tissue oxygenation and performance (Umbreit 2005). Iron is also present in the brain in relatively large amounts and is involved in neurotransmitter function (Burhans 2005); an adequate supply may contribute to maintaining normal cognitive and psychological health, although the mechanisms are not completely elucidated as yet.

An additional consideration when providing supplements at population level is the endemicity of malaria in a given region. Approximately 40% of the world's population is exposed to the malaria parasite and it is endemic in over 100 countries, causing more than a million deaths per year (WHO 2010). Provision of iron in malaria‐endemic areas, particularly to children, has been controversial due to concerns that iron therapy may exacerbate infections, in particular malaria (Okebe 2011; Oppenheimer 2001). It is still not completely clear whether iron produces the same effects among older populations or whether subclinical malaria alters the response to iron supplementation.

Why it is important to do this review

Daily oral supplementation in women has been a longstanding intervention in both public health and clinical fields. Many patients and clinicians ascribe adverse health outcomes (including fatigue and lethargy, impaired cognitive performance and psychological dysfunction) to iron deficiency, even in the absence of anaemia, and attribute improvement in these symptoms to iron supplementation. In addition, many sporting authorities (including the International Olympic Committee (IOC 2009)) recommend screening of female athletes for iron deficiency in order to target the use of iron supplementation, with a view to improving performance. Daily iron and folic acid supplementation for three months should be considered for the prophylaxis of iron deficiency in populations where the prevalence of anaemia exceeds 40%. Iron supplementation has been recommended for preventing anaemia in women of childbearing age, and to optimise pre‐conception iron status (WHO 2011).

Several intervention trials have evaluated improvements in haemoglobin and iron status, as well as non‐haematologic outcomes such as physical, cognitive and psychological health, in menstruating women receiving iron supplementation. However, evaluation of this intervention has not been subject to systematic review and thus it is difficult to estimate the benefits and risks associated with the daily use of iron supplements in menstruating women.

This review will complement the findings of other Cochrane systematic reviews assessing the use of iron supplements alone, or in combination with other vitamins and minerals, in different female populations: intermittent supplementation in children (De‐Regil 2011), iron supplementation among children in malaria‐endemic areas (Okebe 2011), intermittent iron supplementation in menstruating women (Fernández‐Gaxiola 2011), daily and intermittent iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnant women (Peña‐Rosas 2009), multiple micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy (Haider 2006), and iron supplementation during the postpartum period (Dodd 2004).

Objectives

To establish the evidence for effects of daily supplementation with iron on anaemia and iron status, as well as on physical, psychological and neurocognitive health, in menstruating women.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs with either individual‐ or cluster‐randomisation. Quasi‐RCTs are trials that use non‐random systematic methods to allocate participants to treatment groups such as alternation, or assignment based on date of birth or case record number (Higgins 2011a).

We did not include observational study designs (e.g. cohort or case‐control studies) in the meta‐analysis but, where relevant, considered such evidence in the discussion.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Menstruating women, that is, women beyond menarche and prior to menopause who were not pregnant or lactating or had any condition that impeded the presence of menstrual periods, regardless of their baseline iron or anaemia status (or both), ethnicity, country of residence or level of endurance.

We included studies for which results for females between 12 years and 50 years of age (plausible age range for menstruation) could be extracted separately, or in which more than half of the participants fulfilled this criterion.

Exclusion criteria

Studies targeting populations with conditions affecting iron metabolism, intestinal malabsorption conditions, ongoing excessive blood loss (including ongoing blood donations), inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, chronic congestive cardiac failure, chronic renal failure, chronic liver failure or chronic infectious disease.

Studies that were purely evaluating kinetics of erythropoiesis or pharmacology of iron supplements or absorption.

Studies in hospitalised or ill people.

Types of interventions

We considered iron supplements to comprise iron formulations that may or may not have also contained folic acid or vitamin C, since these are commonly included in iron preparations. Doses needed to be given no less than five days a week, regardless of dose and duration of the intervention.

We included, in an overall comparison, effects of daily oral supplementation with iron alone, or in combination with folic acid or vitamin C, versus receiving no supplemental iron. In this review, 'iron supplement' refers to compounds containing iron salts such as ferrous sulphate, ferrous fumarate, ferrous gluconate, carbonyl or colloidal iron. Iron may have been delivered as a tablet (including dispersible forms), capsule, or liquid.

We included (and noted) studies in which iron supplements were given along with cointerventions such as other nutrients (e.g. zinc, vitamin A), deworming, education or other approaches but only if the cointerventions were the same in both the intervention and comparison groups. We did not include studies where additional haemopoietic agents were administered such as exogenous erythropoietin.

We undertook a simple overall comparison (iron versus control) and considered use of cointerventions as subgroups. This enabled us to appraise the overall evidence for intervening with iron supplementation, but differed from what we had proposed in our original protocol (Differences between protocol and review).

Interventions excluded from this review include point‐of‐use fortification with micronutrient powders or lipid‐based foods, mass fortification of staple foods such as wheat or maize flours or condiments, and intermittent iron supplementation, which are evaluated in previous or ongoing Cochrane reviews (see Fernández‐Gaxiola 2011; Pasrischa 2012; Peña‐Rosas 2014; Self 2012).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Anaemia (haemoglobin concentrations below a cut‐off defined by trial authors).*

Haemoglobin (g/L).*

Iron deficiency (as measured by trial authors using indicators of iron status such as ferritin or transferrin).*

Iron‐deficiency anaemia (defined by the presence of anaemia plus iron deficiency, diagnosed with an indicator of iron status selected by trialists).*

All‐cause mortality.*

Adverse side effects (as measured by trial authors such as abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, heartburn, diarrhoea, constipation).*

Cognitive function (as defined by trial authors. For example, for adolescents, school grades, test performance, intelligence testing; for adults not in school, formal tests addressing intelligence, memory, attention, and other cognitive domains). We accepted any measure of cognitive function that has been previously validated as an appropriate test in this domain.*

Outcomes marked with an asterisk (*) are included in Table 1.

Secondary outcomes

Iron status (as reported: ferritin, transferrin saturation, soluble transferrin receptor, soluble transferrin receptor‐ferritin index, total iron binding capacity, serum iron).

Physical exercise performance (as defined by trial authors, in particular peak exercise performance (VO2 max/peak ‐ absolute and relative), submaximal exercise performance (heart rate, percentage VO2 max, energy consumption), and endurance (time)).

Psychological health (e.g. depression as defined by the Center for Epidemiological Studies ‐ Depression (CES‐D) scale (Radloff 1977) or visual analogue scales; fatigue as defined by the trial authors, anxiety as defined by trial authors.

Adherence (percentage of women who consumed more than 70% of the expected doses).

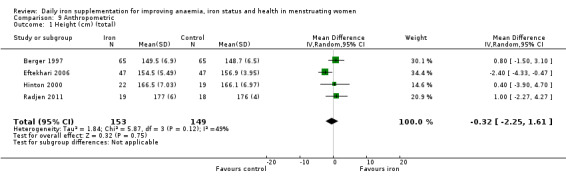

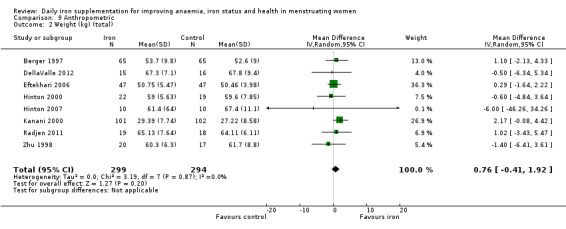

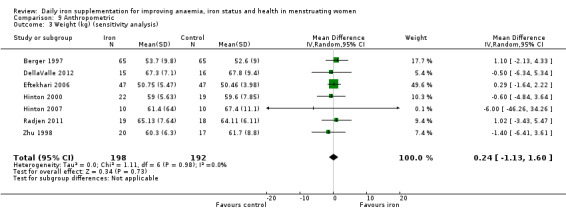

Anthropometric measures (Z scores for height and weight by age for adolescents, and body mass index for adults).

Serum/plasma zinc (μmol/L).

Vitamin A status (serum/plasma retinol (mmol/L) or retinol binding protein (mmol/L)).

Red cell folate (mmol/L).

For populations in malaria‐endemic areas, we reported two additional outcomes.

Malaria incidence.

Malaria severity.

If two outcomes evaluated the same construct (e.g. iron status evaluated with either ferritin or soluble transferrin receptors), we treated them separately.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases in March 2012, November 2014 and again on 12 November 2015.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2015, Issue 10, part of The Cochrane Library), and which includes the specialised register of the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group.

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to November Week 1 2015).

Embase (1980 to 2015 Week 45; Ovid).

CINAHL (1937 to current; EBSCOHost).

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (CPCI‐S; 1937 to current; Web of Science).

Science Citation Index (SCI; 1970 to 10 November 2015; Web of Science).

POPLINE (popline.org; all available years).

We searched the following regional indexes from the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Library on 28 May 2015, and again on 8 December 2015.

Literature in the Health Sciences in Latin America and the Caribbean (LILACS; all available years).

African Index Medicus (AIM; all available years).

Western Pacific Region Index Medicus (WPRIM; all available years).

Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR; all available years).

Index Medicus for South‐East Asia Region (IMSEAR; all available years).

We used the following sources to search for theses on 28 May 2015, and again on 8 December 2015.

WorldCat (worldcat.org; all available years).

DART‐Europe E‐theses Portal (dart‐europe.eu; all available years).

Australasian Digital Theses Program (trove.nla.gov.au; all available years).

Proquest Dissertations and Theses Global (all available years).

The search strategies for each database are reported in Appendix 1. We did not apply any date or language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We searched all available years of the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) on 25 May 2015, and again on 8 December 2015 (apps.who.int/trialsearch). We also screened previously published reviews in order to identify other possible studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We stored all studies identified by our search strategy in Endnote 2015 reference manager software prior to evaluation. Titles and abstracts of obtained studies were screened by two authors (MSYL and SRP) independently. For those studies that were selected as potentially eligible for inclusion, two of the review authors (from CES, JS, MSYL or SRP) assessed whether they met the review's inclusion criteria. We kept records of all eligibility decisions using a digital eligibility form for each study. If study reports contained insufficient information on methods, participants or interventions, we attempted to contact the authors for further information. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between the coauthors.

Data extraction and management

We extracted data from studies using a digital extraction form designed for this review. We first piloted the form on a small number of study reports and modified it as necessary. For eligible studies, two review authors (two from JS, MSYL, CS or SRP) independently extracted data using the form. One author (MSYL) then entered data into Review Manager (RevMan) software (RevMan 2014) and a second author (SRP) checked data entry for accuracy. We resolved discrepancies through discussion between all review authors.

For each study, we collected data on the following domains.

-

Trial methods:

study design;

unit and method of allocation;

masking of participants and outcomes; and

exclusion of participants after randomisation and proportion of losses at follow‐up.

-

Participants:

location of the study;

sample size;

age;

baseline status of anaemia;

baseline status of iron deficiency; and

inclusion and exclusion criteria, as described in Criteria for considering studies for this review.

-

Intervention:

dose of iron;

type of iron compound;

duration of the intervention; and

cointerventions.

-

Comparison group:

use of placebo or no intervention.ppe

-

Outcomes:

primary and secondary outcomes, as outlined in Types of outcome measures.

We recorded outcomes that were both prespecified and not prespecified, although we did not use the latter to underpin the conclusions of the review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For each study, two of the four review authors (CES, JS, MSYL, SRP) used the standard Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool to assess the risk of bias of each included study across the following eight domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, other biases, and overall risk of bias (Higgins 2011b). They applied the following criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between review authors.

1. Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We assessed whether the method used to generate the allocation sequence was described in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it produced comparable groups and rated it as follows.

Low risk of bias: any truly random process (e.g. random number table, computer random number generator).

High risk of bias: any non‐random process (e.g. odd or even date of birth, hospital or clinic record number).

Unclear risk of bias: random sequence generation not stated or insufficient information to deem whether study was at low or high risk of bias.

2. Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We assessed whether the method used to conceal the allocation sequence was described in sufficient detail to determine whether intervention allocations could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment and rated it as follows.

Low risk of bias: telephone or central randomisation, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes used to conceal the allocation sequence.

High risk of bias: open random allocation, unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes used to conceal the allocation sequence.

Unclear risk of bias: not stated or insufficient information to deem whether study was at low or high risk of bias.

3. Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We assessed all measures used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We rated the risk of performance bias associated with blinding as follows.

Low risk of bias: participants and personnel were reported to be blinded in such a manner that they could not determine the groups to which participants belonged.

High risk of bias: participant or personnel were not blinded or blinding was performed in such a manner that it was possible to determine the groups to which participants belonged.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias.

Whilst assessed separately, we combined these assessments into a single evaluation of risk of bias associated with blinding (Higgins 2011b).

4. Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We assessed all measures used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge as to which intervention a participant received and rated it as follows.

Low risk of bias: blinding of outcome assessment or no blinding of outcome assessment but measurement is unlikely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

High risk of bias: no blinding of outcome assessment, where measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding, or where blinding could have been broken.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias.

5. Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We assessed whether incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed and rated it as follows.

Low risk of bias: either there were no missing outcome data, or the missing outcome data were unlikely to bias the results because the study authors provided transparent documentation of participant flow throughout the study, or the proportion of missing data was similar in the intervention and control groups, the reasons for missing data were provided and balanced across intervention and control groups, or the reasons for missing data were not likely to bias the results (e.g. moving house).

High risk of bias: missing outcome data were likely to bias the results. Studies were also considered at high risk of bias if more than 30% of randomised participants were lost to follow‐up and unavailable for final assessment.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information was available to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias.

6. Selective outcome reporting (checking for possible reporting bias)

We evaluated whether reports of the study were free from selective outcome reporting and rated it as follows.

Low risk of bias: where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review were reported.

High risk of bias: where not all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes were reported, one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified, outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used, or the study failed to include results of a key outcome that was expected to have been reported.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient information to deem whether the study was at low or high risk of bias.

7. Other sources of bias

We assessed whether the study was free from other problems that could put it at risk of bias as follows.

Low risk of bias: no other sources of bias appeared relevant to the trial that were not covered in previous categories of bias.

High risk of bias: another source of bias was uncovered.

Unclear risk of bias: insufficient evidence was available to permit a judgement of high or low risk of bias.

8. Overall risk of bias

We summarised the risk of bias at two levels: within studies (across domains) and across studies (for each primary outcome).

For the first, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias in each of the above mentioned domains and whether we considered them likely to impact on the findings. We considered studies to be at low overall risk of bias if they were not at high risk of bias for any category, and were assessed as having low risk of bias for random sequence generation OR low risk of bias for allocation concealment (selection bias), and were also rated at low risk of bias for either blinding (performance or detection bias) or incomplete outcome data (attrition bias). Studies which failed to provide sufficient information (i.e. unclear risk of bias) to enable categorisation of risk of bias were excluded from categorisation as being at low risk of bias. We explored the impact of including only studies at low risk of bias on primary outcomes through a Sensitivity analysis.

For the assessment across studies, we set out the main findings of the review in Table 1. The primary outcomes for each comparison were listed with estimates of relative effects along with the number of participants and studies contributing data for those outcomes. For each primary outcome, we assessed the quality of the evidence across all trials contributing data using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach (Balshem 2011), which involves consideration of within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias. The results were expressed as one out of four levels of quality (high, moderate, low or very low). This assessment was limited to the trials included in this review only. We produced the tables using GRADEpro GDT 2015.

Measures of treatment effect

We did not combine dichotomous and continuous data for analysis, and instead considered them separately.

Dichotomous data

We presented the results as average risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

We used the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. Where some studies reported endpoint data and others reported change from baseline data (with errors), we combined these in the meta‐analysis using the MD providing the outcomes were reported using the same scale.

We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI to combine trials that measured the same outcome but used different methods of measurement.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We combined the results from both cluster‐randomised and individually‐randomised studies if there was little heterogeneity between these study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered as unlikely.

If the results from cluster trials were not adjusted by trial authors, we calculated the trials' effective sample size to account for the effect of clustering in the data. We used the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if available), or from another source (e.g. used the ICCs derived from other, similar trials), and then calculated the design effect with the formula provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011).

Studies with multiple intervention groups

For studies with more than two intervention groups (multi‐arm studies), we included the directly relevant arms only. Where we identified studies with various relevant arms, we combined the groups into a single pair‐wise comparison (Deeks 2011) and included the disaggregated data in the corresponding subgroup category. If the control group was shared by two or more study arms, we divided the control group (events and total population) over the number of relevant subgroup categories to avoid double counting the participants.

Cross‐over trials

We only included the first period of any randomised cross‐over trial prior to the wash‐out period or to a change in the sequence of treatments, and treated them as parallel trials.

Dealing with missing data

Missing individuals

We noted the dropout rate for each included study, which can be seen in Characteristics of included studies tables. We reported rates of attrition in the 'Risk of bias' tables (beneath the Characteristics of included studies tables) and included them in the 'Risk of bias' summary graph. We conducted analysis on an available case‐analysis basis: data were included from those participants whose results were known. We considered variation in the degree of missing data as a potential source of heterogeneity.

Missing data

Where key data (e.g. standard deviations) were missing from the report, we attempted to contact corresponding authors (or other authors if necessary) of included studies to request unreported data. Two authors were contacted for further information (Pereira 2014; Waldvogel 2012). If we were not able to obtain this information, we used methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c), to attempt to calculate it (performed in one study Zavaleta 2000). If this could not be achieved, we did not impute it and noted that the study did not provide data for that particular outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed methodological heterogeneity by examining the methodological characteristics and risk of bias of the studies, and clinical heterogeneity by examining the similarity between the types of participants, interventions and outcomes (Deeks 2011).

For statistical heterogeneity, we examined the forest plots from meta‐analyses for heterogeneity among studies and used the I² statistic (Higgins 2003), Tau², and Chi² test for heterogeneity to quantify the level of heterogeneity among the trials in each meta‐analysis.

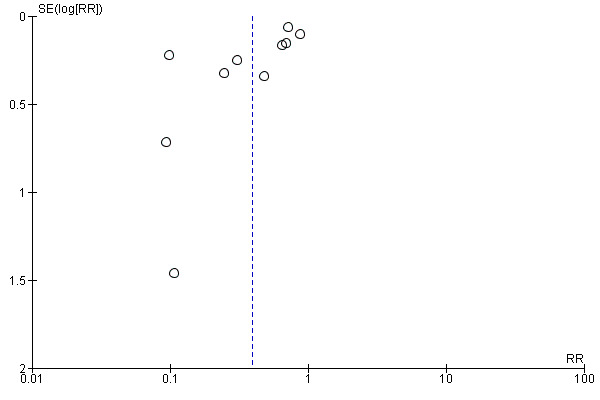

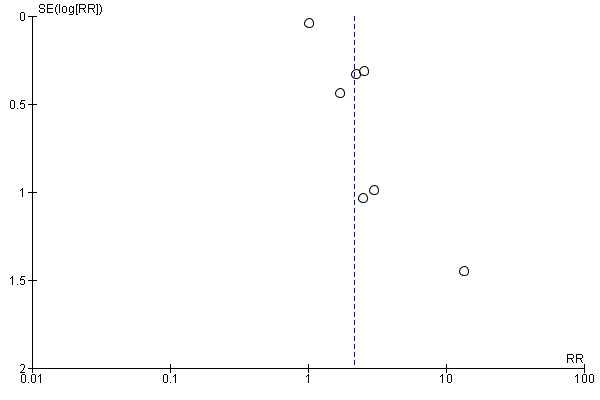

Assessment of reporting biases

Where more than 10 trials contributed data to the primary outcomes, we presented a funnel plot to evaluate asymmetry ‐ a possible indicator of publication bias. Where funnel plot asymmetry was evident, this was formally assessed using Egger's regression test (continuous outcomes) or Peter's or Harbord's test (Sterne 2011); see Differences between protocol and review for more information. This was undertaken using the metan and metabias user‐written modules in Stata 13 (Harbord 2009).

Data synthesis

We conducted a meta‐analysis to obtain an overall estimate of the effect of treatment when more than one study examined similar interventions using similar methods, was conducted in similar populations, and measured similar (comparable) outcomes. We carried out statistical analysis using RevMan 2014.

We used a random‐effects meta‐analysis for combining data, as we anticipated that there was natural heterogeneity between studies attributable to the different doses, durations, populations and implementation/delivery strategies.

Where different studies reported the same outcomes using both continuous and dichotomous measures, we re‐expressed RRs as SMDs or vice versa, and combined the results using the generic inverse‐variance method, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011).

We performed meta‐analyses of dichotomous outcomes using the Mantel‐Haenszel method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed the following subgroup analyses on the primary outcomes only.

Age: adolescents (12 to 18 years), older adults (50 to 55 years).

Nutrient: iron alone or iron + other intervention versus intervention alone, iron plus vitamin C versus vitamin C alone, iron + any cointervention versus that same cointervention alone.

Baseline anaemia status (as defined by trial authors): anaemic, non‐anaemic, mixed or unknown.

Baseline iron status (as defined by trial authors): iron deficient, non‐iron deficient, mixed or unknown.

Baseline iron‐deficiency anaemia status (as defined by trial authors): iron deficient with anaemia, iron deficient without anaemia, non‐iron deficient/unknown status of deficiency.

Daily dose of elemental iron supplementation: less than 30 mg, 30 mg to 60 mg, 61 mg to 100 mg, 101 mg or more elemental iron.

Duration of iron supplementation: 30 days (one month) or less, more than one month to three months inclusive, more than three months.

Malaria endemicity of the setting in which the study was performed: endemic, not endemic, not reported/unknown.

We added a further subgroup analysis post‐hoc: types of iron (ferrous sulphate, ferrous fumarate and others). In addition, we decided to undertake subgroup analysis on the following secondary outcome: ferritin (see Differences between protocol and review).

For meta‐analysis including both endpoint and change scores data, we also conducted a subgroup analysis to separate the effects of the two outcome measures.

We did not conduct subgroup analyses in those outcomes with three or less trials. We explored the forest plots visually and identified where CIs did not overlap to assess differences between subgroup categories. We also formally investigated differences between two or more subgroups (Borenstein 2008).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses examining effects of removing studies at high risk of bias (studies with poor or unclear allocation concealment and either inadequate blinding or high/imbalanced loss to follow‐up) from the analysis. Likewise, for cluster studies reporting outcomes where reliable ICCs could not be obtained, we examined the effects of removing these studies from the analysis.

For additional sensitivity analyses archived for future updates of this review, please see our protocol (Pasricha 2012) and Appendix 2.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

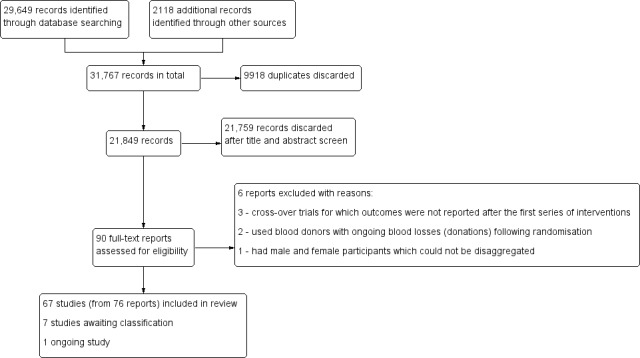

The search strategy identified 31,767 records for possible inclusion, 9918 of which were duplicates. Three studies were published in languages other than English (Machado 2011; Radjen 2011; Wang 2012) ‐ these were translated to English for extraction. After screening, we assessed 90 full‐text reports for eligibility. We included 67 studies (from 76 reports and one personal communication (see DellaValle 2012)), excluded six studies and classified seven studies as awaiting assessment either because we were unable to access the full text for the trials, despite assistance from an academic library, or determine if they were eligible for inclusion. Our search of WHO ICTRP identified one ongoing study, which may be eligible for inclusion when the results become available, although the findings are unlikely to alter the conclusions of this analysis (IRCT201409082365N9).

Figure 1 depicts the process by which we assessed and selected studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Overall, we included 67 trials that recruited a total of 8506 women.

The sample size ranged between 10 and 1390 participants but overall tended to be small: 96% of the studies included fewer than 400 women.

Settings

Studies were conducted in numerous countries of differing cultural and economic background. Included studies in this review were conducted in USA (Binkoski 2004; Bruner 1996; Cooter 1978; DellaValle 2012; Gordeuk 1987; Gordeuk 1990; Hinton 2000; Hinton 2007; Jensen 1991; Kiss 2015; Klingshirn 1992; LaManca 1993; Lyle 1992; McClung 2009; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Rajaram 1995; Rowland 1988; Swain 2007; Viteri 1999; Yadrick 1989; Zhu 1998), Australia (Booth 2014; Leonard 2014; Marks 2014; Walsh 1989; Zaman 2013), United Kingdom (Bryson 1968; Elwood 1966; Elwood 1970; Pereira 2014), Iran (Eftekhari 2006; Kianfar 2000; Maghsudlu 2008), Sri Lanka (Edgerton 1979; Jayatissa 1999; Lanerolle 2000), Sweden (Flink 2006; Hoppe 2013; Rybo 1985), Canada (Larocque 2006; Newhouse 1989), China (Li 1994; Wang 2012), Finland (Fogelholm 1992; Fogelholm 1994), India (Agarwal 2003; Kanani 2000), Israel (Ballin 1992; Magazanik 1991), Japan (Taniguchi 1991; Yoshida 1990), New Zealand (Heath 2001; Prosser 2010), Switzerland (Verdon 2003; Waldvogel 2012), Bolivia (Berger 1997), Brazil (Machado 2011), Chile (Mujica‐Coopman 2015), Korea (Kang 2004), Mexico (Brutsaert 2003), Nepal (Shah 2002), Norway (Røsvik 2010), Peru (Zavaleta 2000), Phillipines (Florencio 1981), Serbia (Radjen 2011), Tanzania (Gunaratna 2015) and Thailand (Charoenlarp 1988).

Only two studies specifically stated being conducted in low socioeconomic settings (Kanani 2000; Zavaleta 2000); however it is likely that other studies were also performed in situations that would include low socioeconomic participants. One study specifically targeted middle‐class participants (as defined by the trial authors) (Agarwal 2003).

Nine studies were performed specifically in an urban setting (Agarwal 2003; Ballin 1992; Bruner 1996; Florencio 1981; Heath 2001; Rybo 1985; Shah 2002; Wang 2012; Zavaleta 2000), four in a rural setting (Berger 1997; Charoenlarp 1988; Edgerton 1979; Gunaratna 2015). One study reports specifically recruiting from both rural and urban settings (Lanerolle 2000). The majority of studies did not specifically state whether the trials were performed in rural or urban settings (Binkoski 2004; Booth 2014; Brutsaert 2003; Bryson 1968; Cooter 1978; DellaValle 2012; Eftekhari 2006; Elwood 1966; Elwood 1970; Flink 2006; Fogelholm 1992; Fogelholm 1994; Gordeuk 1987; Gordeuk 1990; Hinton 2000; Hinton 2007; Jayatissa 1999; Jensen 1991; Hoppe 2013; Kanani 2000; Kang 2004; Kianfar 2000; Kiss 2015; Klingshirn 1992; LaManca 1993; Larocque 2006; Leonard 2014; Li 1994; Lyle 1992; Machado 2011; Magazanik 1991; Maghsudlu 2008; Marks 2014; McClung 2009; Mujica‐Coopman 2015, Murray‐Kolb 2007; Newhouse 1989; Pereira 2014; Prosser 2010; Radjen 2011; Rajaram 1995; Rowland 1988; Røsvik 2010; Swain 2007; Taniguchi 1991; Verdon 2003; Viteri 1999; Waldvogel 2012; Walsh 1989; Yadrick 1989; Yoshida 1990; Zaman 2013; Zhu 1998).

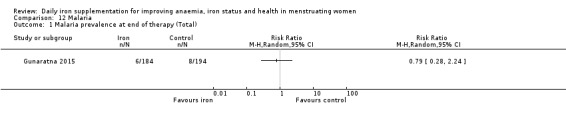

Only two studies specifically reported being performed in a malaria‐endemic area (Charoenlarp 1988; Gunaratna 2015), with the majority not reporting malaria endemicity at the site of the trial.

Participants

Across the included studies a total of 8508 women were included; 4444 in the intervention arm, 4,064 in the control arm. The majority of studies recruited women between the ages of 13 years and 45 years. Three studies included women below 13 years of age: Agarwal 2003: range 10 years to 17 years (mean age not stated); Shah 2002: age range 11 years to 18 years (mean age 15 years); Zavaleta 2000: age range 12 years to 18 years (mean age 15 years). Six studies recruited females older than 45 years (Edgerton 1979: age range 20 years to 60 years (mean age: 35 years); Kiss 2015: age range not reported (mean age: 45.7 years); Machado 2011: age range 20 years to 49 years (mean age: not reported); Røsvik 2010: age range 18 years to 69 years (mean age: 43 years); Swain 2007: age range 21 years to 51 years (mean age: 40 years); Verdon 2003: age range 18 years to 55 years (mean age: 35 years). In these trials, data for participants aged within the target age range could not be extracted separately, although they met our inclusion criteria of comprising more than half of participants within the eligible age range.

Twenty‐six studies recruited women in an educational setting with 12 in secondary education (Agarwal 2003; Ballin 1992; Bruner 1996; Eftekhari 2006; Jayatissa 1999; Kanani 2000; Kianfar 2000; Lanerolle 2000; Larocque 2006; Rowland 1988; Shah 2002; Zavaleta 2000) and 14 in tertiary education (Cooter 1978; DellaValle 2012; Hoppe 2013; Jensen 1991; Klingshirn 1992; Lyle 1992; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Pereira 2014; Rajaram 1995; Taniguchi 1991; Viteri 1999; Yoshida 1990; Zaman 2013; Zhu 1998).

Four studies recruited women through a specific workplace: factory workers (Bryson 1968; Florencio 1981), tea pickers (Edgerton 1979; Li 1994). Ten studies recruited women through sports teams (Cooter 1978; DellaValle 2012; Fogelholm 1992; Kang 2004; Klingshirn 1992; LaManca 1993; Radjen 2011; Rowland 1988; Walsh 1989; Yoshida 1990). Seven studies recruited women through blood donation centres (Gordeuk 1987; Gordeuk 1990; Kiss 2015; Maghsudlu 2008; Marks 2014; Røsvik 2010; Waldvogel 2012); in these studies, women did not undergo further blood donations between enrolment and outcome measurement.

Dose and type of iron interventions

A variety of oral iron formulations were included in this review. The most frequently used was ferrous sulphate (33 studies; Binkoski 2004; Bruner 1996; Brutsaert 2003; DellaValle 2012; Edgerton 1979; Eftekhari 2006; Florencio 1981; Fogelholm 1992; Hinton 2000; Hinton 2007; Jensen 1991; Kianfar 2000; Klingshirn 1992; Lanerolle 2000; Leonard 2014; Li 1994; Lyle 1992; Machado 2011; Magazanik 1991; Maghsudlu 2008; McClung 2009; Mujica‐Coopman 2015; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Newhouse 1989; Pereira 2014; Radjen 2011; Rajaram 1995; Shah 2002; Verdon 2003; Viteri 1999; Waldvogel 2012; Zavaleta 2000; Zhu 1998). One study included two arms: ferrous sulphate and carbonyl iron (Gordeuk 1987). Two studies used carbonyl iron (Gordeuk 1990; Marks 2014). Five studies used ferrous fumarate (Bryson 1968; Cooter 1978; Flink 2006; Fogelholm 1994; Hoppe 2013), and one study used ferric pyrophosphate and ferrous fumurate together (Wang 2012).

Other iron formulations that were used included ferrous carbonate (Elwood 1966; Elwood 1970), ferrous gluconate (Booth 2014; Kiss 2015; Larocque 2006; Zaman 2013), ferric ammonium citrate (Taniguchi 1991), ferrous succinate (Rybo 1985), Niferex ferrous glycine sulphate (Røsvik 2010), amino acid chelate (Heath 2001; Prosser 2010), ferrous sodium citrate (Yoshida 1990), LiquiFer® (Iron polystyrene sulfonate) (Ballin 1992). Twelve studies did not state the specific iron formulation used (Agarwal 2003; Berger 1997; Charoenlarp 1988; Gunaratna 2015; Jayatissa 1999; Kanani 2000; Kang 2004; LaManca 1993; Rowland 1988; Swain 2007; Walsh 1989; Yadrick 1989). Doses of elemental iron varied from 1 mg of elemental iron to approximately 300 mg of elemental iron a day. Duration of iron supplement also varied significantly, ranging from 1 week to 24 weeks.

Excluded studies

We excluded six studies because they did not meet eligibility criteria. Three studies were cross‐over trials that did not report on outcomes at the end of the first parallel intervention period (Brigham 1993; Powell 1991; Schoene 1983). Two studies were undertaken in blood donors in whom further donations during the trial indicated ongoing blood losses (Cable 1988; Simon 1984). In one trial, data from male and female participants could not be disaggregated (Powers 1988).

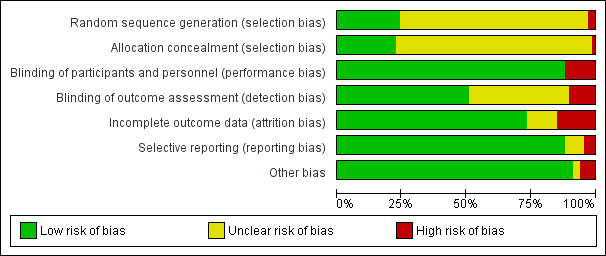

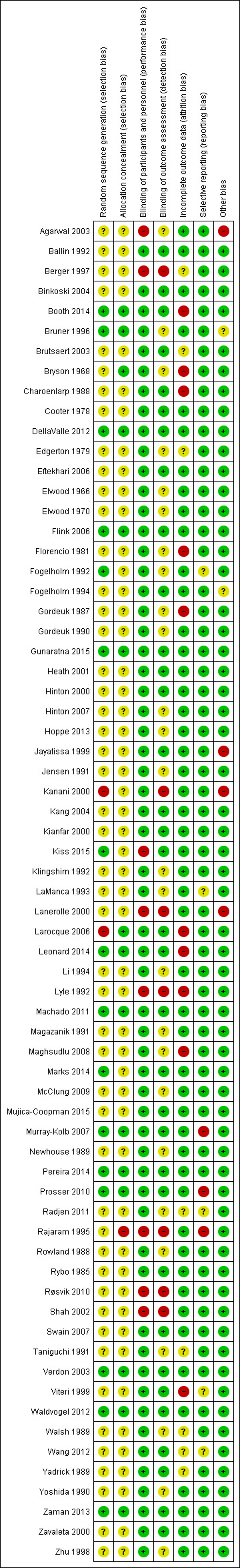

Risk of bias in included studies

Study methods were generally not well described in many of the studies and thus 'Risk of bias' assessment was difficult (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). Using the criteria defined above, only 11 studies were assessed as being at low risk of bias (Bruner 1996; DellaValle 2012; Flink 2006; Fogelholm 1992; Gunaratna 2015; Machado 2011; Marks 2014; Pereira 2014; Verdon 2003; Waldvogel 2012; Zaman 2013). The remaining studies were either assessed as being at high risk of bias or the methods were unclear and thus could not be rated as being at low risk of bias.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Sixteen studies were considered to have generated the random sequence using a method considered to be at low risk of bias (Booth 2014; Bruner 1996; DellaValle 2012; Flink 2006; Fogelholm 1992; Gunaratna 2015; Kiss 2015; Leonard 2014; Machado 2011; Marks 2014; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Pereira 2014; Prosser 2010; Verdon 2003; Waldvogel 2012; Zaman 2013. Sequence generation was considered at high risk of bias in two studies (Kanani 2000; Larocque 2006). In 49 of the included trials, it was unclear how the randomisation sequence had been generated.

Fifteen of the included studies used methods of concealing group allocation that we judged to be at low risk of bias (Booth 2014; Bruner 1996; Bryson 1968; DellaValle 2012; Flink 2006; Gunaratna 2015; Larocque 2006; Leonard 2014; Machado 2011; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Pereira 2014; Prosser 2010; Verdon 2003; Waldvogel 2012; Zaman 2013 ). In one trial, methods were considered at high risk of bias (Rajaram 1995). In the remaining 51 trials, methods were either not described or were unclear.

Blinding

Most trials administered the placebo to blinded participants and relatively few trials reported on methods for blinding outcome assessors. Overall, 59 studies reported blinding of participants and were deemed at low risk of performance bias (Ballin 1992; Binkoski 2004; Booth 2014; Bruner 1996; Brutsaert 2003; Bryson 1968; Charoenlarp 1988; Cooter 1978; DellaValle 2012; Edgerton 1979; Eftekhari 2006; Elwood 1966; Elwood 1970; Flink 2006; Florencio 1981; Fogelholm 1992; Fogelholm 1994; Gordeuk 1987; Gordeuk 1990; Gunaratna 2015; Heath 2001; Hinton 2000; Hinton 2007; Hoppe 2013; Jayatissa 1999; Jensen 1991; Kanani 2000; Kang 2004; Kianfar 2000; Klingshirn 1992; LaManca 1993; Larocque 2006; Leonard 2014; Li 1994; Machado 2011; Magazanik 1991; Marks 2014; Maghsudlu 2008; McClung 2009; Mujica‐Coopman 2015; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Newhouse 1989; Pereira 2014; Prosser 2010; Radjen 2011; Rowland 1988; Rybo 1985; Swain 2007; Taniguchi 1991; Verdon 2003; Viteri 1999; Waldvogel 2012; Walsh 1989; Wang 2012; Yadrick 1989; Yoshida 1990; Zaman 2013; Zavaleta 2000; Zhu 1998). Eight studies were deemed to be at high risk of performance bias: seven as placebo was not used (Agarwal 2003; Berger 1997; Kiss 2015; Lanerolle 2000; Rajaram 1995; Røsvik 2010; Shah 2002), one as diet intervention was not blinded and would have revealed placebo group from intervention group (Lyle 1992).

Thirty‐four studies were deemed to be at low risk of detection bias (Ballin 1992; Binkoski 2004; Booth 2014; Brutsaert 2003; Charoenlarp 1988; Cooter 1978; DellaValle 2012; Eftekhari 2006; Flink 2006; Fogelholm 1994; Gunaratna 2015; Heath 2001; Hinton 2000; Jayatissa 1999; Kang 2004; Kianfar 2000; Kiss 2015; Larocque 2006; Leonard 2014; Machado 2011; Marks 2014; Mujica‐Coopman 2015; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Pereira 2014; Prosser 2010; Rybo 1985; Swain 2007; Verdon 2003; Viteri 1999; Waldvogel 2012; Wang 2012; Yadrick 1989; Zaman 2013; Zavaleta 2000). Twenty‐six studies were deemed unclear for detection bias as the study failed to state whether personnel were blinded or it remained unclear if outcomes would be affected by lack of blinding (Agarwal 2003; Bruner 1996; Bryson 1968; Edgerton 1979; Elwood 1966; Elwood 1970; Florencio 1981; Fogelholm 1992; Gordeuk 1987; Gordeuk 1990; Hinton 2007; Hoppe 2013; Jensen 1991; Klingshirn 1992; LaManca 1993; Li 1994; Magazanik 1991; Maghsudlu 2008; McClung 2009; Newhouse 1989; Radjen 2011; Rowland 1988; Taniguchi 1991; Walsh 1989; Yoshida 1990; Zhu 1998). Seven studies were deemed at high risk of detection bias as assessors may have known which participants belonged to which group due to a lack of placebo or unblinded personnel, with outcomes that may have been influenced by this lack of blinding (Berger 1997; Kanani 2000; Lanerolle 2000; Lyle 1992; Rajaram 1995; Røsvik 2010; Shah 2002).

Incomplete outcome data

While we assessed that the majority of the included trials had acceptable levels of attrition (with loss to follow‐up and missing data being less than 30% and balanced across groups), in nine trials the levels of attrition were high or not balanced across groups (Booth 2014; Bryson 1968; Charoenlarp 1988; Florencio 1981; Gordeuk 1987; Larocque 2006; Leonard 2014; Lyle 1992; Viteri 1999), while attrition was not reported in a further eight trials (Berger 1997, Brutsaert 2003, Edgerton 1979, Radjen 2011, Taniguchi 1991, Walsh 1989; Wang 2012; Yadrick 1989).

Selective reporting

We were not able to fully assess outcome reporting bias as we only had access to published study reports. We assessed publication bias using funnel plots for haemoglobin, anaemia, iron deficiency, ferritin and adverse effects (any effects, any gastrointestinal effects, constipation, loose stools/diarrhoea, and abdominal pain). While we detected no funnel plot asymmetry for haemoglobin or ferritin, we observed evidence of asymmetry for anaemia and ferritin (both indicating the possibility of missing studies reporting a smaller than observed effect on anaemia prevalence from iron). However, there were few studies reporting these outcomes precluding more detailed statistical analysis of these funnel plots. Nevertheless, the possibility of publication bias exists for these key outcomes. Five studies were deemed to be at an unclear risk of selective reporting (Fogelholm 1992; LaManca 1993; Radjen 2011; Viteri 1999; Wang 2012) and three studies were deemed to be at high risk of selective reporting due to outcomes mentioned being analysed but not presented (Murray‐Kolb 2007; Prosser 2010; Rajaram 1995).

Other potential sources of bias

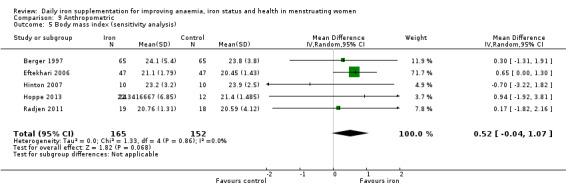

The majority of trials had no clear other sources of bias. Only four studies used a cluster design but did not report the ICC or other relevant data in the manuscript and were thus deemed to be at high risk of other bias (Agarwal 2003; Jayatissa 1999; Kanani 2000; Lanerolle 2000). These papers reported on the following outcomes: haemoglobin and anaemia (Agarwal 2003); haemoglobin, anaemia and ferritin (Jayatissa 1999); haemoglobin, weight and body mass index (Kanani 2000); haemoglobin, ferritin, iron deficiency, transferrin saturation (Lanerolle 2000). We obtained the ICC from external sources (Gulliford 1999): the ICC for haemoglobin was 0.00059, which is low; for example, for a cluster comprising 30 individuals, the design effect would be only 1.017, which implies adjustment of the sample size would only be minor. Likewise, the ICC for ferritin from this source was only 0.00004, which again is unlikely to result in a large design effect and obviates the need for an adjustment of the sample size (Ukoumunne 1999). For weight and body mass index, reported in Kanani 2000, we undertook a sensitivity analysis to evaluate effects of excluding this study (which can be seen in Analysis 9.5).

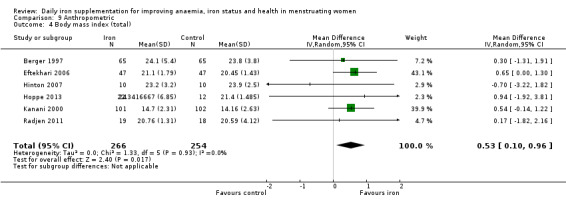

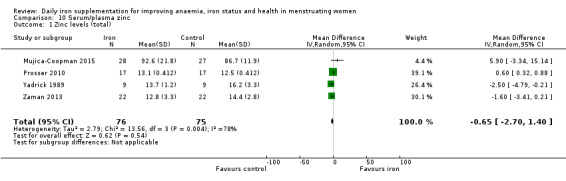

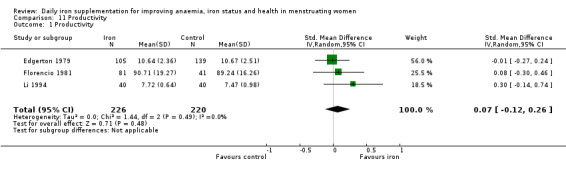

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Anthropometric, Outcome 5 Body mass index (sensitivity analysis).

Of the remaining studies, two were deemed at unclear risk of other bias (Bruner 1996; Fogelholm 1994) as data was only presented in a table making other sources of bias unable to be excluded, and 61 studies (from 71 reports) had no other identifiable potential source of bias and were therefore deemed at low risk (Ballin 1992; Berger 1997; Binkoski 2004; Booth 2014; Brutsaert 2003; Bryson 1968; Charoenlarp 1988; Cooter 1978; DellaValle 2012; Edgerton 1979; Eftekhari 2006; Elwood 1966; Elwood 1970; Flink 2006; Florencio 1981; Fogelholm 1992; Gordeuk 1987; Gordeuk 1990; Gunaratna 2015; Heath 2001; Hinton 2000; Hinton 2007; Hoppe 2013; Jensen 1991; Kang 2004; Kianfar 2000; Kiss 2015; Klingshirn 1992; LaManca 1993; Larocque 2006; Leonard 2014; Li 1994; Lyle 1992; Machado 2011; Magazanik 1991; Maghsudlu 2008; Marks 2014; McClung 2009; Mujica‐Coopman 2015; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Newhouse 1989; Pereira 2014; Prosser 2010; Radjen 2011; Rajaram 1995; Rowland 1988; Rybo 1985; Røsvik 2010; Shah 2002; Swain 2007; Taniguchi 1991; Verdon 2003; Viteri 1999; Waldvogel 2012; Walsh 1989; Wang 2012; Yadrick 1989; Yoshida 1990; Zaman 2013; Zavaleta 2000; Zhu 1998.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

All included trials contributed data to the review but some studies randomised participants to intervention arms that were not relevant to the comparisons we assessed. For these studies we did not include data from all groups in the analyses. Furthermore, some studies did not contain data in an extractable form, or did not contain data in a way in which they could be combined in meta‐analyses. For these studies, we provided a narrative description of the results.

For cluster‐randomised trials we extracted the estimated effective sample size by adjusting the data to account for the clustering effect.

Primary Outcomes

Anaemia

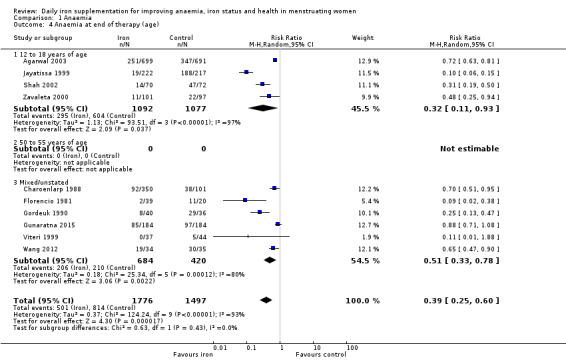

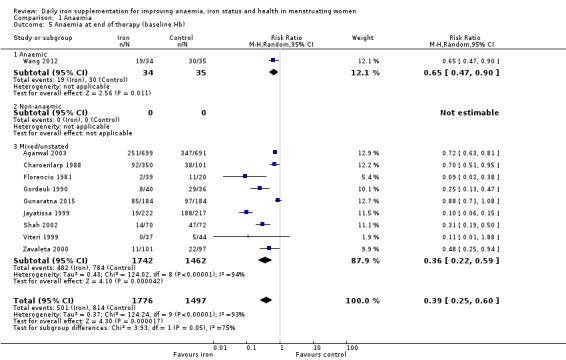

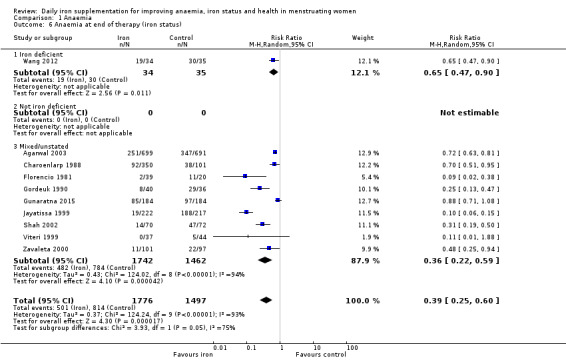

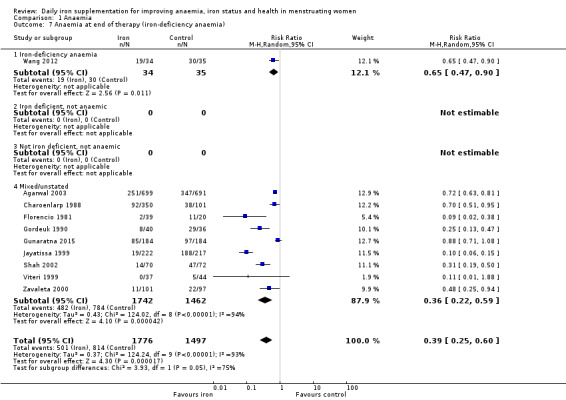

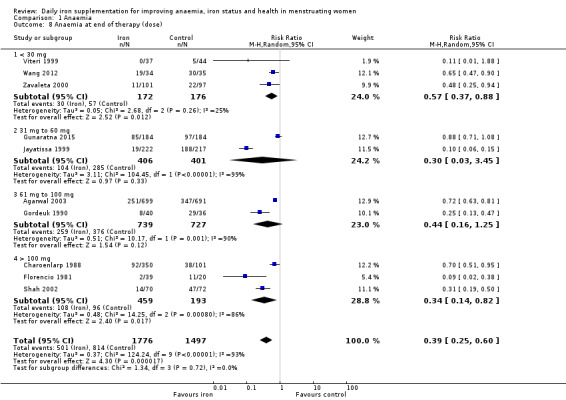

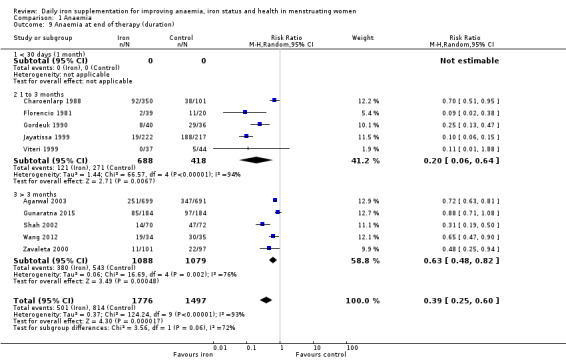

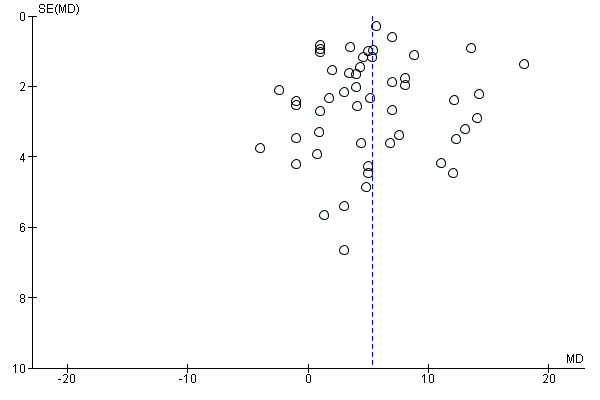

Ten studies, comprising 3273 women, measured anaemia prevalence at the end of intervention (Agarwal 2003; Charoenlarp 1988; Florencio 1981; Gordeuk 1990; Gunaratna 2015; Jayatissa 1999; Shah 2002; Viteri 1999; Wang 2012; Zavaleta 2000). Women receiving iron were significantly less likely to be anaemic at the end of intervention compared to women receiving control (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.60, moderate quality evidence; Analysis 1.1; Table 1). There was variation among trials in terms of the size of the treatment effect (Tau² = 0.37; Chi² = 124.24, df = 9, (P < 0.00001); I² = 93%). Although visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated asymmetry, broadly suggesting missing studies reported smaller effect sizes on anaemia, which may be in keeping with a reporting bias, formal statistical testing using the Harbord and Peters tests did not demonstrate evidence of publication bias (Sterne 2011); see Figure 4.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 1 Anaemia at end of therapy (total).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Anaemia, outcome: 1.1 Anaemia at end of therapy (total).

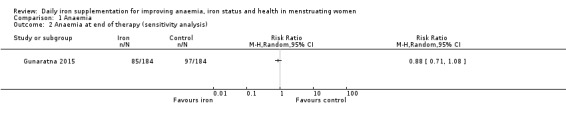

Only one study reporting this outcome was considered at low overall risk of bias (Gunaratna 2015). Analysis of this study did not show a difference between iron and control (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 2 Anaemia at end of therapy (sensitivity analysis).

Subgroup analysis

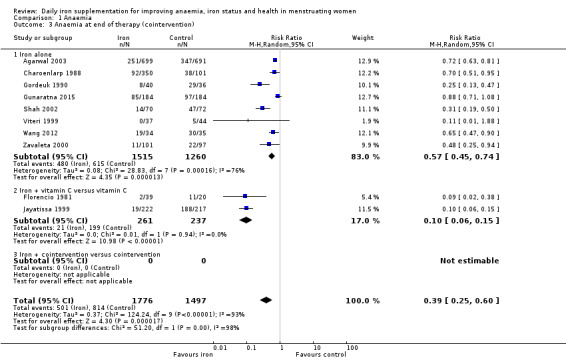

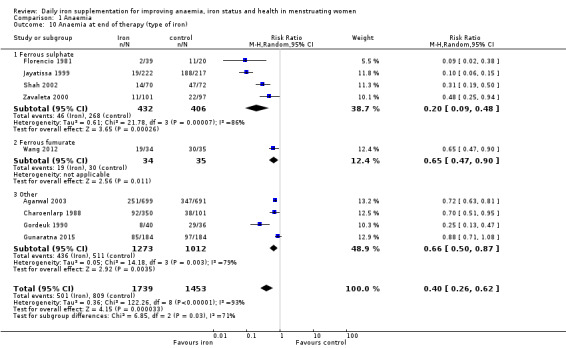

There was evidence of differences between subgroups. Specifically, women in studies comparing iron alone with control experienced a smaller reduction in the prevalence of anaemia (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.74, 8 studies, 2775 women) compared with women randomised to iron + vitamin C versus vitamin C alone (RR 0.10, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.15, 2 studies, 498 women; test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 51.2, df = 1 (P < 0.00001), I² = 98%; Analysis 1.3). There were no differences observed in effect sizes based on age of participants (Analysis 1.4). Although subgroup differences were observed based on baseline anaemia status (Analysis 1.5), iron status (Analysis 1.6), and iron‐deficiency anaemia status (Analysis 1.7), most studies fell into the 'unclassified' subgroup and thus subgroup analyses were not constructive. Significant differences in effect size on risk of anaemia were seen for different doses and durations of iron supplementation, however these were non‐linear with increasing dose (Analysis 1.8) or duration (Analysis 1.9). No studies in malaria‐endemic settings were included. Limited data indicated that ferrous sulphate is more effective than other formulations in reducing prevalence of anaemia (ferrous sulphate: RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.48, 4 studies, 838 women; ferrous fumarate: RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.90, 1 study, 69 women; other formulations: RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.87, 4 studies, 2285 women; test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 6.85, df = 2 (P value = 0.03), I² = 70.8%; Analysis 1.10).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 3 Anaemia at end of therapy (cointervention).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 4 Anaemia at end of therapy (age).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 5 Anaemia at end of therapy (baseline Hb).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 6 Anaemia at end of therapy (iron status).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 7 Anaemia at end of therapy (iron‐deficiency anaemia).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 8 Anaemia at end of therapy (dose).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 9 Anaemia at end of therapy (duration).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Anaemia, Outcome 10 Anaemia at end of therapy (type of iron).

High levels of heterogeneity may be explained by variation in the clinical matrix of study designs (i.e. more than one factor could account for heterogeneity, which cannot be adequately captured by each subgroup analysis. For example, studies used different doses and durations, and recruited participants with different underlying iron status.

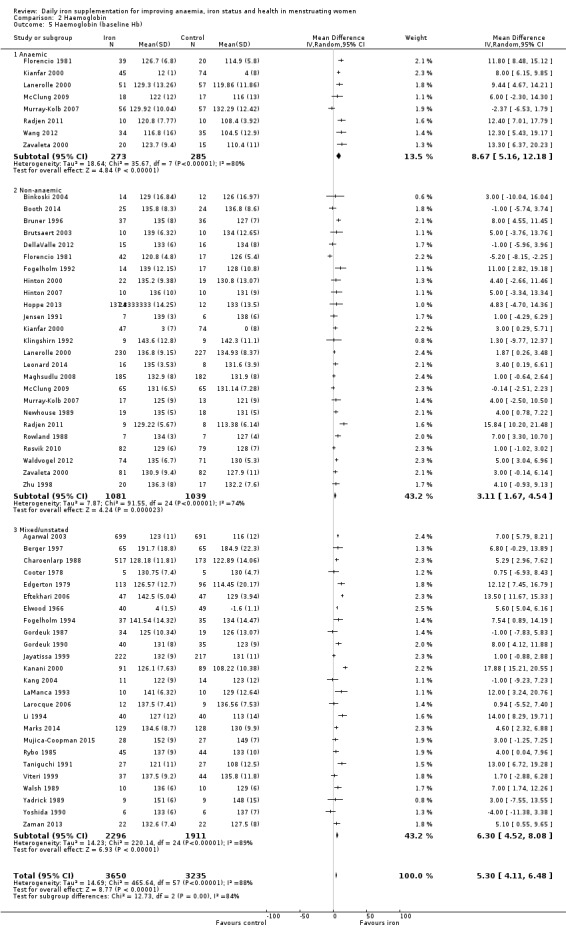

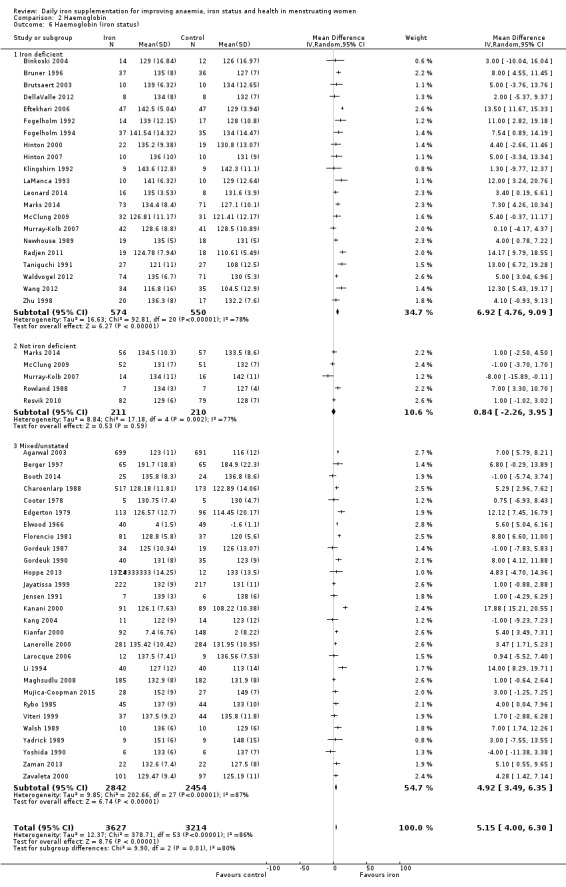

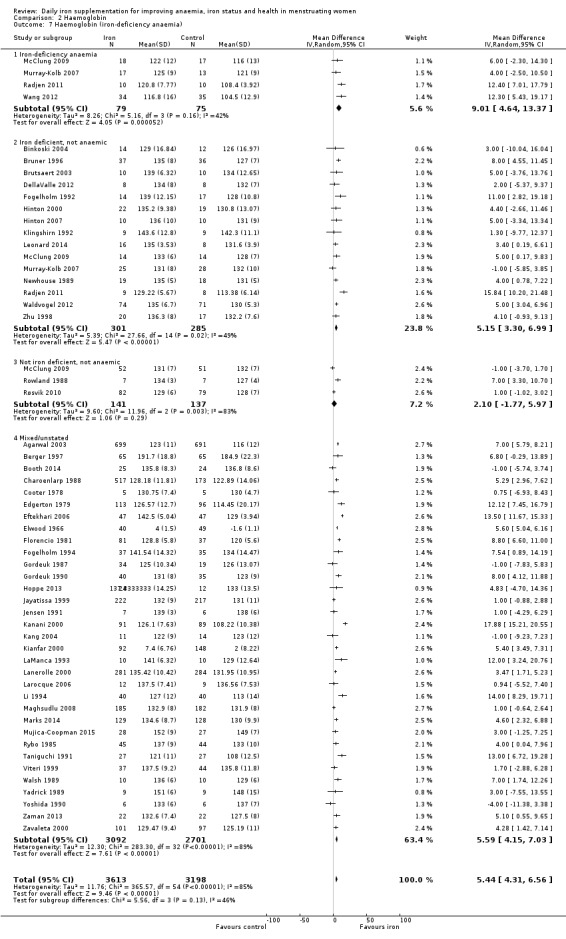

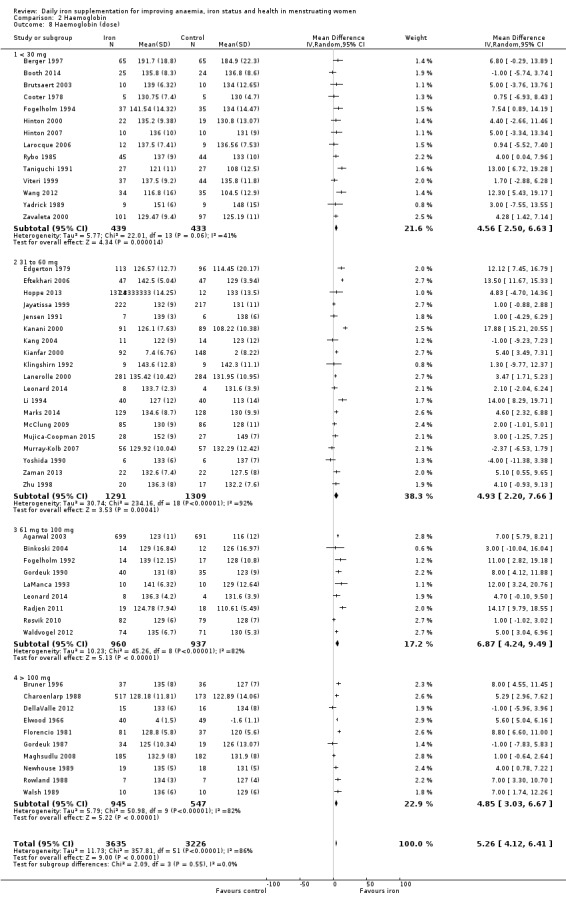

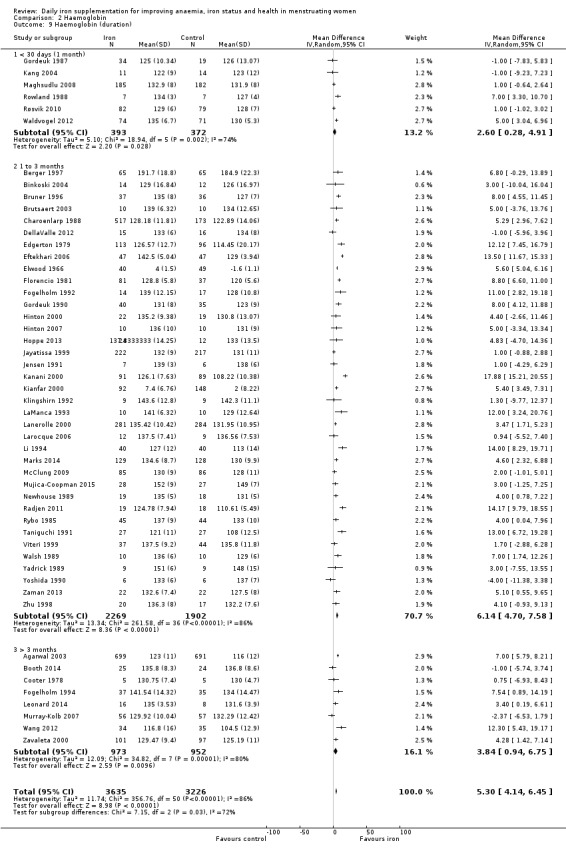

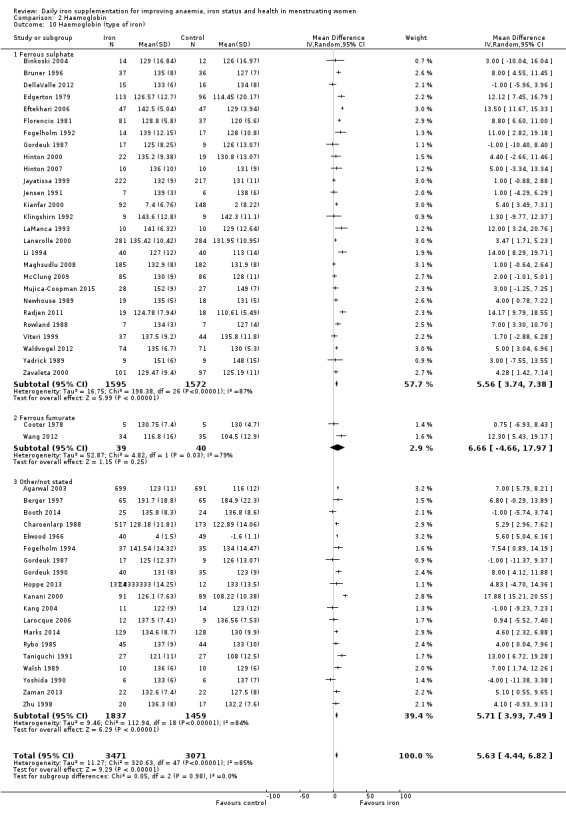

Haemoglobin

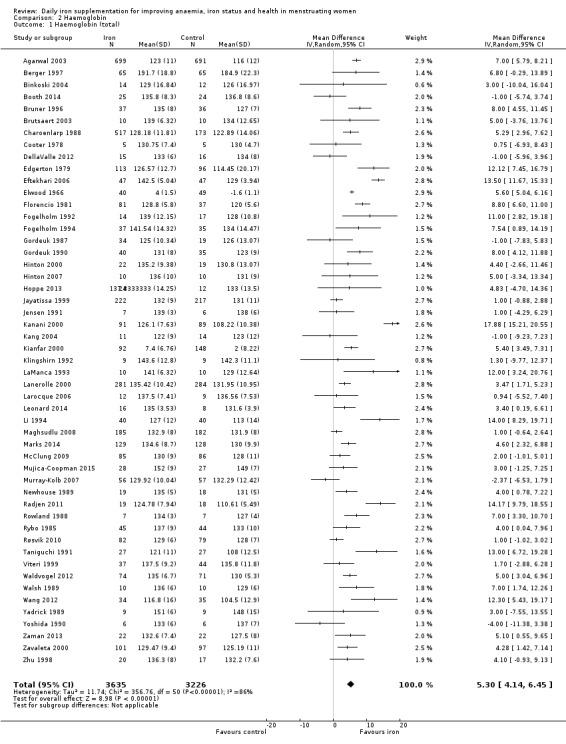

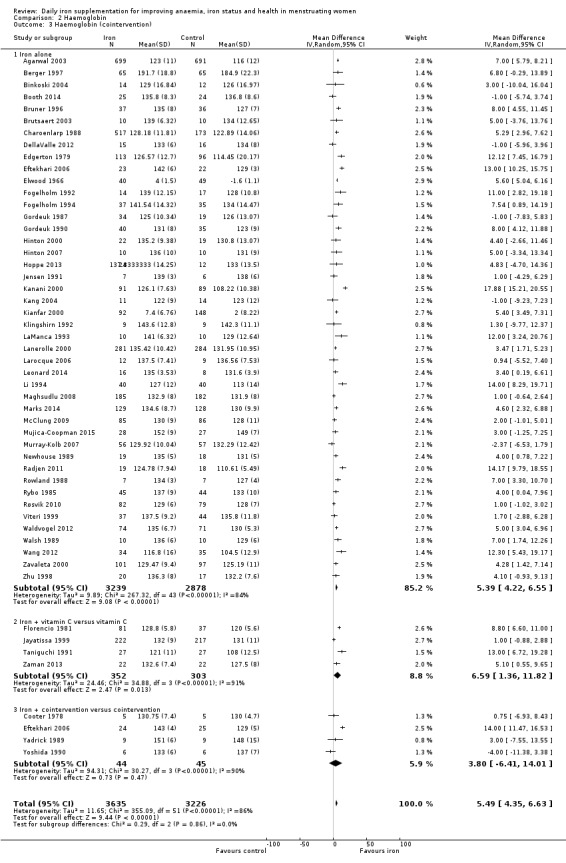

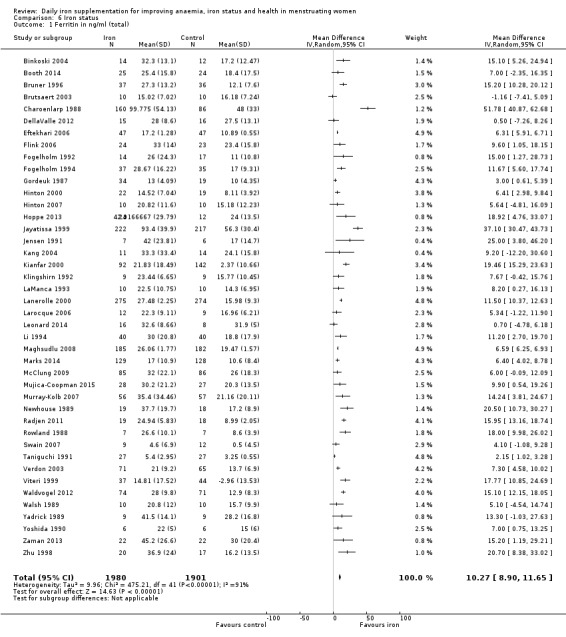

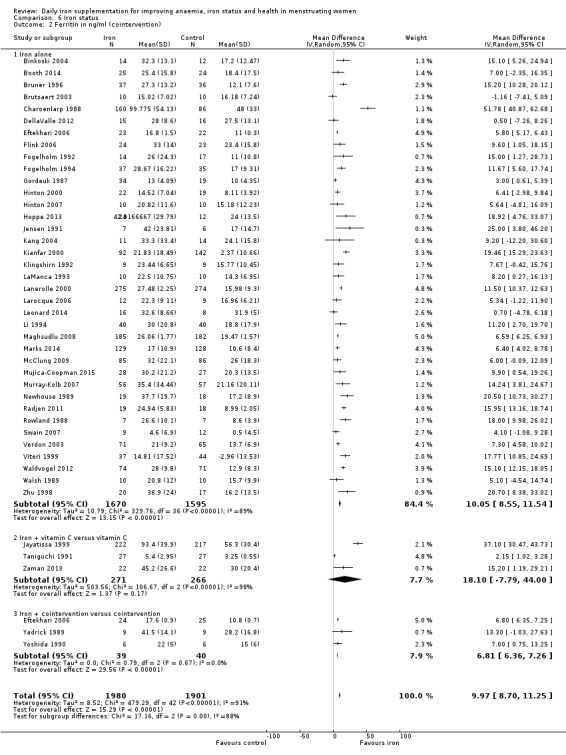

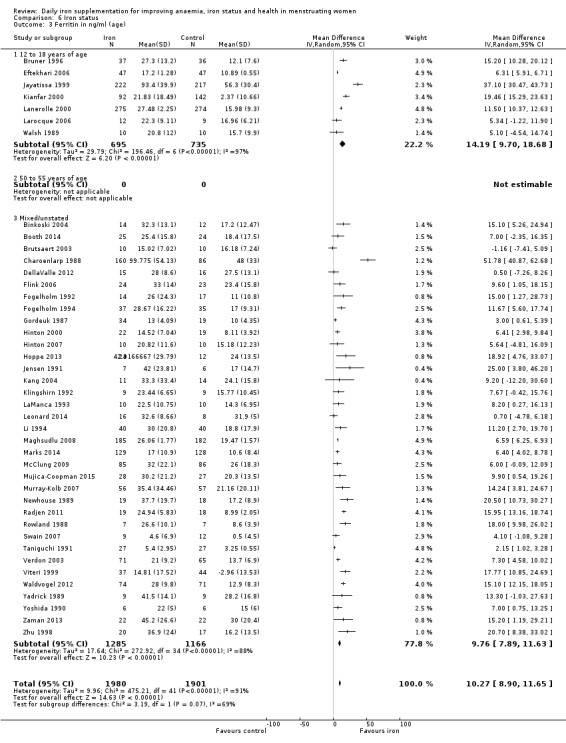

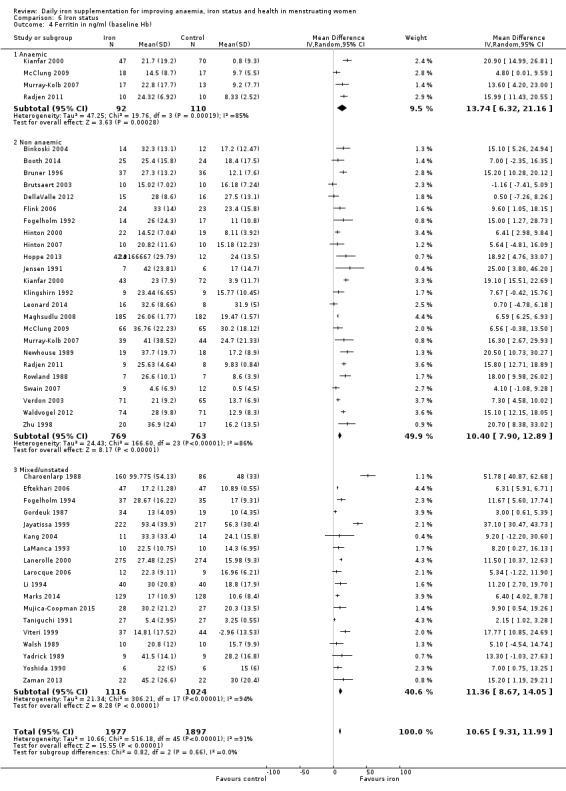

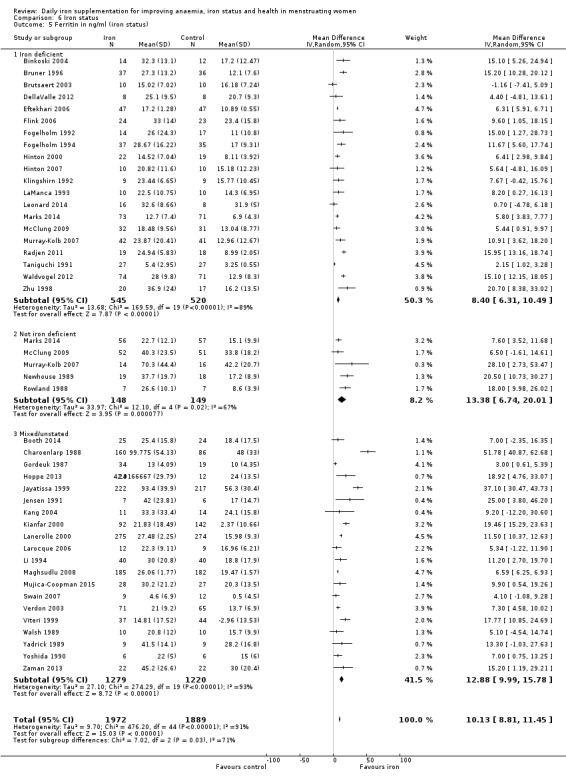

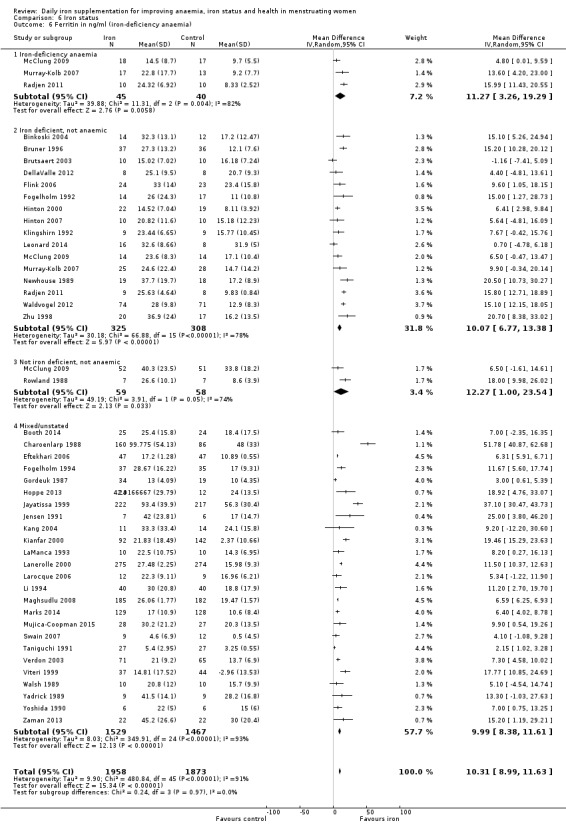

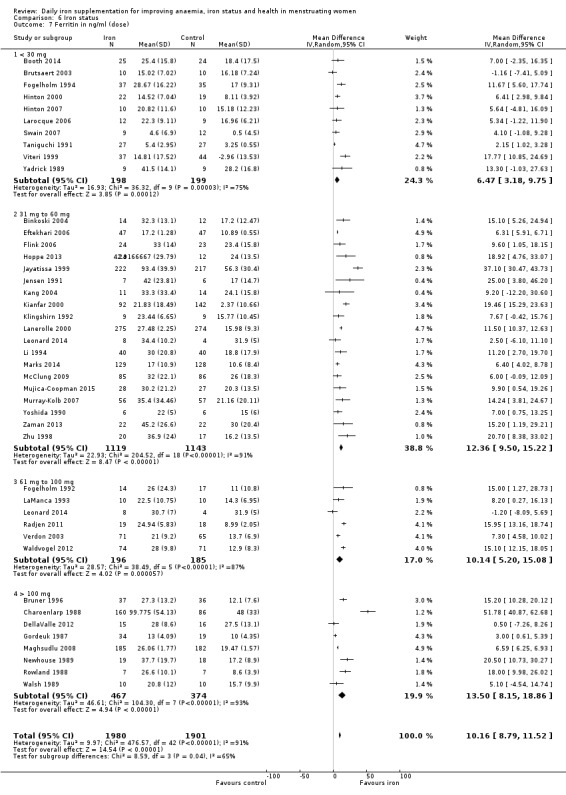

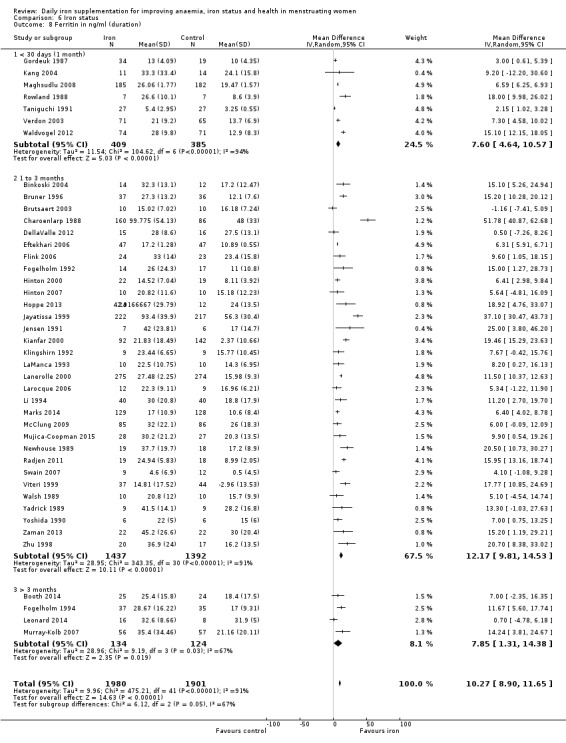

Fifty‐one trials recruiting 6861 women measured haemoglobin concentrations at the end of intervention (Agarwal 2003; Berger 1997; Binkoski 2004; Booth 2014; Bruner 1996; Brutsaert 2003; Charoenlarp 1988; Cooter 1978; DellaValle 2012; Edgerton 1979; Eftekhari 2006; Elwood 1966; Florencio 1981; Fogelholm 1992; Fogelholm 1994; Gordeuk 1987; Gordeuk 1990; Hinton 2000; Hinton 2007; Hoppe 2013; Jayatissa 1999; Jensen 1991; Kanani 2000; Kang 2004; Kianfar 2000; Klingshirn 1992; LaManca 1993; Lanerolle 2000; Larocque 2006; Leonard 2014; Li 1994; Maghsudlu 2008; Marks 2014; McClung 2009; Mujica‐Coopman 2015; Murray‐Kolb 2007; Newhouse 1989; Radjen 2011; Rowland 1988; Rybo 1985; Røsvik 2010; Taniguchi 1991; Viteri 1999; Waldvogel 2012; Walsh 1989; Wang 2012; Yadrick 1989; Yoshida 1990; Zaman 2013; Zavaleta 2000; Zhu 1998). Women receiving iron had a higher haemoglobin concentration at the end of intervention compared with women receiving control (MD 5.30, 95% CI 4.14 to 6.45; heterogeneity: Tau² = 11.74; Chi² = 356.76, df = 50 (P < 0.00001); I² = 86%; high quality evidence; Analysis 2.1; Table 1). There was no obvious funnel plot asymmetry (Figure 5).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 1 Haemoglobin (total).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Haemoglobin, outcome: 2.1 Haemoglobin (total).

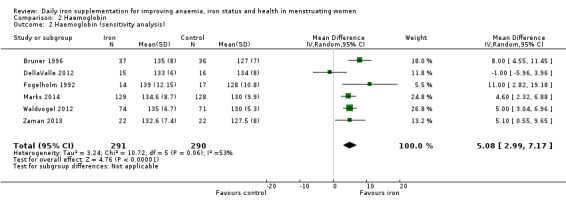

When only studies considered at low overall risk of bias were included in the analysis (six studies; 581 women: Bruner 1996; DellaValle 2012; Fogelholm 1992; Marks 2014; Waldvogel 2012; Zaman 2013), the effect size was similar (MD 5.08, 95% CI 2.99 to 7.17; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 2 Haemoglobin (sensitivity analysis).

Subgroup analysis

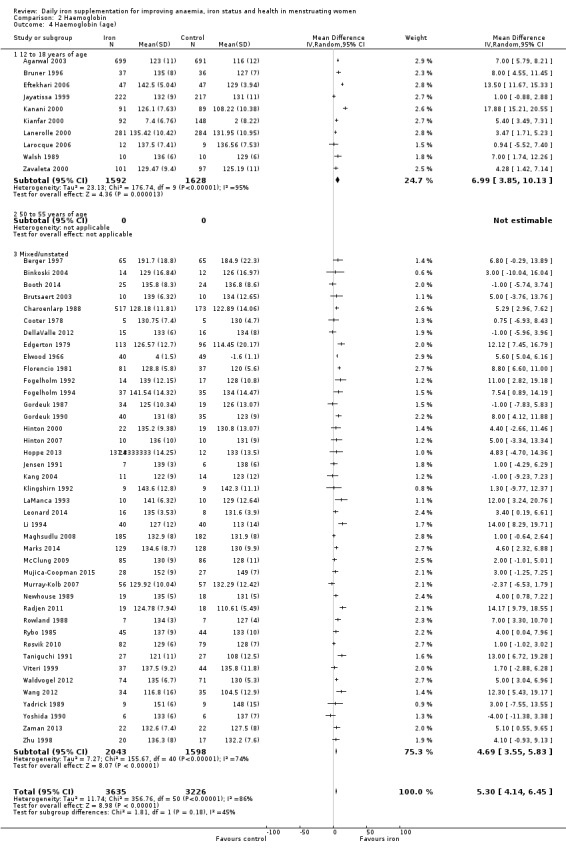

Subgroup analyses may explain the observed heterogeneity. The large number of studies and participants for this outcome provide a rich data set for evaluation of subgroup differences. There was no evidence of a difference in MD between women receiving iron alone or iron with vitamin C or another cointervention (Analysis 2.3). There was no subgroup difference based on age of women (Analysis 2.4). There was a greater increase in haemoglobin in studies among women with baseline anaemia (MD 8.67, 95% CI 5.16 to 12.18, 8 studies, 558 women) or in whom baseline anaemia status was not defined (MD 6.30, 95% CI 4.52 to 8.08, 25 studies, 4207 women) compared with those who were non‐anaemic at baseline (MD 3.11, 95% CI 1.67 to 4.54, 25 studies, 2120 women; test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 12.73, df = 2 (P value = 0.002), I² = 84.3%; Analysis 2.5). Similarly, iron did not improve haemoglobin in iron replete women (MD 0.84, 95% CI ‐2.26 to 3.95, 5 studies, 421 women), but did increase haemoglobin concentration in women who were either iron deficient (as defined by the trial authors) (MD 6.92, 95% CI 4.76 to 9.09, 21 studies, 1124 women) or in whom iron status had not been defined at baseline (MD 4.92, 95% CI 3.49 to 6.35, 28 studies, 5296 women; test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 9.90, df = 2 (P value = 0.007), I² = 79.8%); see Analysis 2.6. There was no subgroup difference in the effect of iron on haemoglobin between women who were iron‐deficient anaemic, non‐anaemic iron deficient, non‐anaemic non‐iron deficient, and undefined (Analysis 2.7). There was no difference in effect from iron on haemoglobin according to dose of iron given (Analysis 2.8). Haemoglobin levels increased more when iron was given for one to three months (MD 6.14, 95% CI 4.70 to 7.58, 37 studies, 4171 women) when compared to less than one month (MD 2.60, 95% CI 0.28 to 4.91, 6 studies, 765 women) or greater than three months (MD 3.84, 95% CI 0.94 to 6.75, 8 studies, 1925 women; test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 7.15, df = 2 (P value = 0.03), I² = 72%; Analysis 2.9). Only one study had been undertaken in a malaria‐endemic area limiting subgroup analyses by malaria endemicity. There was no evidence of subgroup difference between trials using different formulations of iron (ferrous sulphate, ferrous fumarate, and others) (Analysis 2.10).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 3 Haemoglobin (cointervention).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 4 Haemoglobin (age).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 5 Haemoglobin (baseline Hb).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 6 Haemoglobin (iron status).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 7 Haemoglobin (iron‐deficiency anaemia).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 8 Haemoglobin (dose).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 9 Haemoglobin (duration).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Haemoglobin, Outcome 10 Haemoglobin (type of iron).

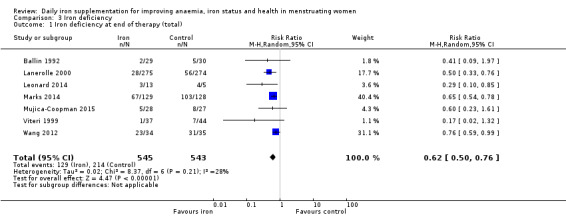

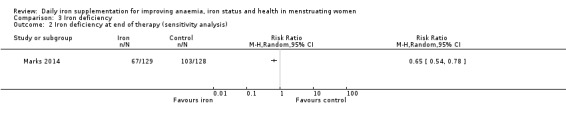

Iron deficiency

Seven studies recruiting 1088 women measured iron deficiency at the end of the intervention (Ballin 1992; Lanerolle 2000; Leonard 2014; Marks 2014; Mujica‐Coopman 2015; Viteri 1999; Wang 2012). Women receiving iron had a reduced risk of iron deficiency compared with women receiving control (RR 00.62, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.76; heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.02; Chi² = 8.37, df = 6 (P value = 0.21); I² = 28%; moderate quality evidence; Analysis 3.1). When only the single study (257 women) at low risk of bias was included (Marks 2014), the effect size was similar (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.78; Analysis 3.2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Iron deficiency, Outcome 1 Iron deficiency at end of therapy (total).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Iron deficiency, Outcome 2 Iron deficiency at end of therapy (sensitivity analysis).

Subgroup analysis

There were too few studies to enable subgroup analysis.

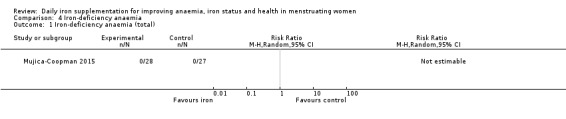

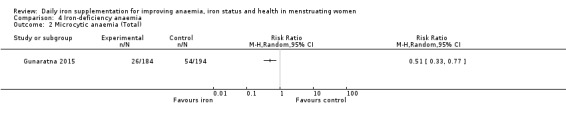

Iron‐deficiency anaemia

Only one study (Mujica‐Coopman 2015), involving 55 women, specifically reported iron‐deficiency anaemia, with no events in either the iron or control groups (Analysis 4.1). One other study (Gunaratna 2015) reported microcytic anaemia and showed a significant reduction with iron therapy compared to controls (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.77, 378 women; Analysis 4.2).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Iron‐deficiency anaemia, Outcome 1 Iron‐deficiency anaemia (total).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Iron‐deficiency anaemia, Outcome 2 Microcytic anaemia (Total).

All‐cause mortality

No studies reported data on all‐cause mortality.

Adverse side effects

Data on adverse effects were generally reported as proportions of populations experiencing side effects. Data were amalgamated using terms defined by the trial authors: 'any side effect' (Ballin 1992; Hoppe 2013; Leonard 2014; Maghsudlu 2008; Marks 2014; Pereira 2014; Waldvogel 2012), 'any gastrointestinal side effect' (Gordeuk 1987; Hoppe 2013; Marks 2014; Pereira 2014; Waldvogel 2012), 'loose stools/diarrhoea' (Gordeuk 1987; Leonard 2014; Marks 2014; Pereira 2014; Rybo 1985; Waldvogel 2012), 'hard stools/constipation' (Bruner 1996; Gordeuk 1990; Leonard 2014; Maghsudlu 2008; Marks 2014; Pereira 2014; Rybo 1985; Waldvogel 2012), 'abdominal pain' (Bryson 1968; Gordeuk 1990; Maghsudlu 2008; Marks 2014; Pereira 2014; Rybo 1985; Waldvogel 2012), 'nausea' (Bryson 1968; Gordeuk 1990; Leonard 2014; Maghsudlu 2008; Marks 2014; Pereira 2014; Rybo 1985; Waldvogel 2012), 'change in stool colour' (Bruner 1996; Leonard 2014; Marks 2014; Pereira 2014), 'reflux/heartburn' (Pereira 2014), and 'headache' (Gordeuk 1987; Gordeuk 1990; Maghsudlu 2008; Pereira 2014).

Any side effects