Abstract

Purpose

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway aberrations are common in human breast cancer. Furthermore, PIK3CA mutations are commonly associated with resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) or anti-estrogen receptor (ER) agents in HER2 or ER positive (HER2+/ER+) breast cancer. Hence, deciphering the underlying mechanisms of PIK3CA mutations in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer would provide novel insights into elucidating resistance to anti-HER2/ER therapies.

Methods

In this study, we systematically investigated the biological consequences of PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer by uniquely incorporating mRNA transcriptomic data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and proteomic data from reverse-phase protein arrays.

Results

Our integrative bioinformatics analyses revealed that several important pathways such as STAT3 and VEGF/hypoxia were selectively altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer. Protein differential expression analysis indicated that an elevated eIF4G might promote tumor angiogenesis and growth via regulation of the hypoxia-activated switch in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. We observed hypo-phosphorylation of EGFR in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer versus HER2+ PIK3CAwild-type (PIK3CAWT). In addition, ER and PIK3CAH1047R might cooperate to activate STAT3, MAPK, AKT, and Hippo pathways in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. A higher YAPpS127 level was observed in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients than that in an ER+PIK3CAWT subgroup. By examining breast cancer cell lines having both microarray gene expression and drug treatment data from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer and the Stand Up to Cancer datasets, we found that the elevated YAP1 mRNA expression was associated with the resistance of BCL-2 family inhibitors, but with the sensitivity to MEK/MAPK inhibitors in breast cancer cells.

Conclusions

In summary, these findings shed light on the functional consequences of PIK3CAH1047R-driven breast tumorigenesis and resistance to the existing therapeutic agents in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer.

Keywords: PIK3CA, Bioinformatics, Synergistic interactions, HER2, ER, Breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in the United States and other parts of the world. According to the cancer statistics in 2016, a total of 246,660 new breast cancer cases and 40,450 deaths in the United States were estimated [1]. Furthermore, breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease and has been categorized into three main therapeutic groups: (i) human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2 or HER2) amplified, having significant clinical benefit from anti-HER2 therapies; (ii) estrogen receptor-positive (ER+, luminal), responding to targeted hormonal therapies; and (iii) basal-like or triple-negative breast cancer (lacking expression of the ER, HER2, and progesterone receptor). In addition, breast cancer often arises by the accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations that alter various signaling pathways (i.e., PI3K/AKT), resulting in dysregulation of downstream molecular events and heterogeneous changes at the gene and/or protein expression level [2–6].

Approximately 40 % of HER2-positive (HER2+) breast cancer cases harbor activating mutations in PIK3CA, especially at two “hotspots”: E542K and E545K (exon 9) in the helical domain and H1047R (exon 20) in the kinase domain [7, 8]. Two recent studies independently reported that PIK3CAH1047R induced multi-potency and multi-lineage mammary tumors and further causes breast tumor heterogeneity [9, 10]. Hanker et al. studied the synergistic interaction between PIK3CA mutation and HER2 in HER2+ breast cancer using the HER2+PIK3CAH1047R mouse model [11]. The authors found that mutant PIK3CA and HER2 could synergistically accelerate HER2-driven transgenic mammary tumors and induce resistance to combinatorial therapies of anti-HER2 agents. The CLEO-PATRA trial found that PIK3CA mutations were associated with a poor progression-free survival in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and chemotherapy [12]. Further, Loibl et al. found that PIK3CA mutations were associated with lower rates of pathological complete response to anti-HER2 therapies in HER2+ breast cancers [13]. However, disease-free survival and overall survival rates were not significantly different in the patients with mutant PIK3CA from the PIK3CAwild-type (PIK3CAWT) [13]. Altogether, although PIK3CA mutations show some inconsistent clinical utility, the biological validity of the data raises the interesting hypothesis that combining PI3K inhibitors with anti-HER2 therapeutic agents may be more effective for patients harboring PIK3CA mutations in HER2+ breast cancer [3, 14, 15].

Although PIK3CA mutations commonly occur in HER2+ breast cancer, PIK3CA is more frequently mutated in luminal breast cancer [7, 8]. Furthermore, dysregulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway often contributes to the resistance of anti-endocrine agents in breast cancer [16–18]. For example, Miller et al. found that a hyper-activation of the PI3K pathway promoted the escape from hormone dependence in ER+ breast cancer in the long-term estrogen deprivation breast cancer cell lines [16]. Sabine et al. evaluated the effects of PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer patients who received anti-endocrine therapies in the Exemestane Versus Tamoxifen-Exemestane pathology study covering more than 4000 patients [17]. Interestingly, while PIK3CA mutations were found in approximately 40 % of luminal breast cancer patients, they could not serve as an independent predictor of the outcome to anti-endocrine therapies. Therefore, there is a strong need to decipher molecular events contributing to the responses of anti-endocrine therapies in PIK3CA-mutant and ER+ breast cancer.

The recent release of multi-omics data from large-scale cancer genomics projects such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) allowed us to systematically study the signaling pathways altered by PIK3CA mutations in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer [7, 19, 20]. Furthermore, TCGA projects provided the reverse-phase protein assay (RPPA) profiling using a panel of proteins and phosphoproteins. This RPPA has been applied to hundreds of tumors across multiple cancer types, including breast cancer [21]. An integrative bioinformatics approach combining the transcriptomic and protein expression data from TCGA and RPPA, as well as the related clinical information, would be effective for uncovering the biological consequences of PIK3CA mutations in the breast cancer patients who have developed the resistance. Such knowledge would aid in developing more efficient anti-HER2, anti-endocrine, or combinatorial therapeutics for breast cancer in the post-genomic era [22].

In this study, we proposed an integrative bioinformatics framework to study functional consequences of PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer by uniquely exploiting protein expression from RPPA [21] and RNA-seq data from the TCGA breast cancer project [7, 8]. We hypothesized that PIK3CAH1047R might synergistically cooperate with HER2/ER to activate the specific signaling pathways that contributed to breast tumorigenesis or to the resistance of anti-HER2 or anti-endocrine therapies in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer. We found that EGFR was hypo-phosphorylated in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients compared to the HER2+PIK3CAWT group. In addition, ER and PIK3CAH1047R might cooperate to activate STAT3, MAPK, AKT, and Hippo pathways. By further integrating microarray gene expression and drug treatment data in breast cancer cell lines, we found that an elevated mRNA expression of YAP1 was associated with the resistance or sensitivity of several existing targeted cancer agents. In summary, these findings provided novel insights into the functional consequences of PIK3CAH1047R-driven tumorigenesis and drug resistance, enabling the timely development of targeted therapies in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Data collection and pre-processing

Gene expression

We downloaded read count data for 1097 breast primary tumors from TCGA [7, 8] (http://cancergenome.nih.gov, January, 2015) using the R package in TCGA-Assembler [23]. We obtained clinical data for breast cancer samples from the original clinical dataset (clinical_patient_piblic_brca.txt) as described in previous studies [7, 8]. According to the current clinical guideline jointly issued by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the College of American Pathology, a breast tumor is called ER positive if the corresponding nuclear staining is ≥1 %, otherwise called ER negative. For HER2, a breast tumor with an immunohistochemistry (IHC) value of 0 or 1+ is called “negative”, while IHC level 3+ is called “positive.” The detailed descriptions were provided in previous studies [7, 8]. We also collected microarray gene expression data for breast cancer cell lines from two sources: (i) genecentric RMA-normalized mRNA expression data across 53 breast cancer cell lines was extracted from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database (version: updated in October, 2012) [24, 25]; and (ii) microarray gene expression profiles across 45 breast cancer cell lines were collected from the Stand Up to Cancer (SU2C) database [26]. Gene-level expression values in SU2C were computed using aroma.affymetrix with quantile normalization and a log-additive probe-level model based on the HuEx-1_0-stv2,DCCg,Spring2008 chip definition file, as described in the previous study [26].

Protein expression

Protein or phosphoprotein (protein/phosphoprotein) expression data measured by the RPPA approach were extracted from TCPA [21]. Normalized values based on replicate-based normalization were used for protein differential expression analyses.

Drug pharmacological data

We downloaded drug pharmacological data from two previous studies [25, 26]. First, Garnett et al. [25] assayed 48,178 drug-cell line combinations with a range of 275 to 507 cell lines per drug for more than 130 anticancer drugs. The pharmacological data across cell lines based on the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was converted to the natural log micromolar [25, 26]. Second, Heiser et al. tested 74 therapeutic drugs against 45 different breast cancer cell lines [26]. The pharmacological data across cell lines based on the concentration of 50 % of maximal inhibition of cell proliferation (GI50) was converted to −log10(GI50).

Gene co-expression weighted protein interaction network

We constructed a protein interaction network (PIN) for YAP based on protein–protein interactions as done in our previous studies [27–29]. We calculated the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) value for each gene–gene pair using the RNASeq-V2 data and mapped the PCC value onto the above PIN to build a co-expression weighted PIN for YAP, as described previously [27–31]. The co-expression weighted network graph was drawn using Cytoscape (v2.8.1) [32].

Gene and protein/phosphoprotein differential expression analyses

We used the edgeR package [33] for gene differential expression analyses based on RNAseq read count data for primary breast cancer and matched normal tissues collected from the TCGA breast cancer project [7, 8]. We defined a significantly up-regulated gene using cutoff: log2(FC) > 1 and adjusted P value (q) < 0.01. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to perform the protein/phosphoprotein differential analyses based on normalized RPPA protein expression data collected from TCPA [21].

Oncogenic pathway activity analyses

To explore the specific oncogenic signaling pathways altered by PIK3CA mutation in different subtypes of breast cancer, we grouped the breast cancer patients into 8 categories: HER2+PIK3CAH1047R, HER2+PIK3CAWT, HER2−PIK3CAH1047R, HER2−PIK3CAWT, ER+ PIK3CAH1047R, ER+PIK3CAWT, ER−PIK3CAH1047R, and ER−PIK3CAWT. We then performed gene differential expression analyses using the edgeR package [33] for the samples in each aforementioned category by comparing normal breast tissues in the same TCGA dataset. The details of significantly mutated genes for each category were provided in Supplementary Table 1. We collected a panel of 52 well-annotated gene signatures that represent the main oncogenic pathways in breast cancer from a previous study [34]. Finally, we performed gene set enrichment analysis for the significantly up-regulated genes in each category across 52 well-annotated gene signatures in breast cancer using Fisher’s exact test.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were conducted using the R package (v3.0.2) (http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

PIK3CA hotspot mutations across subtypes in breast cancer

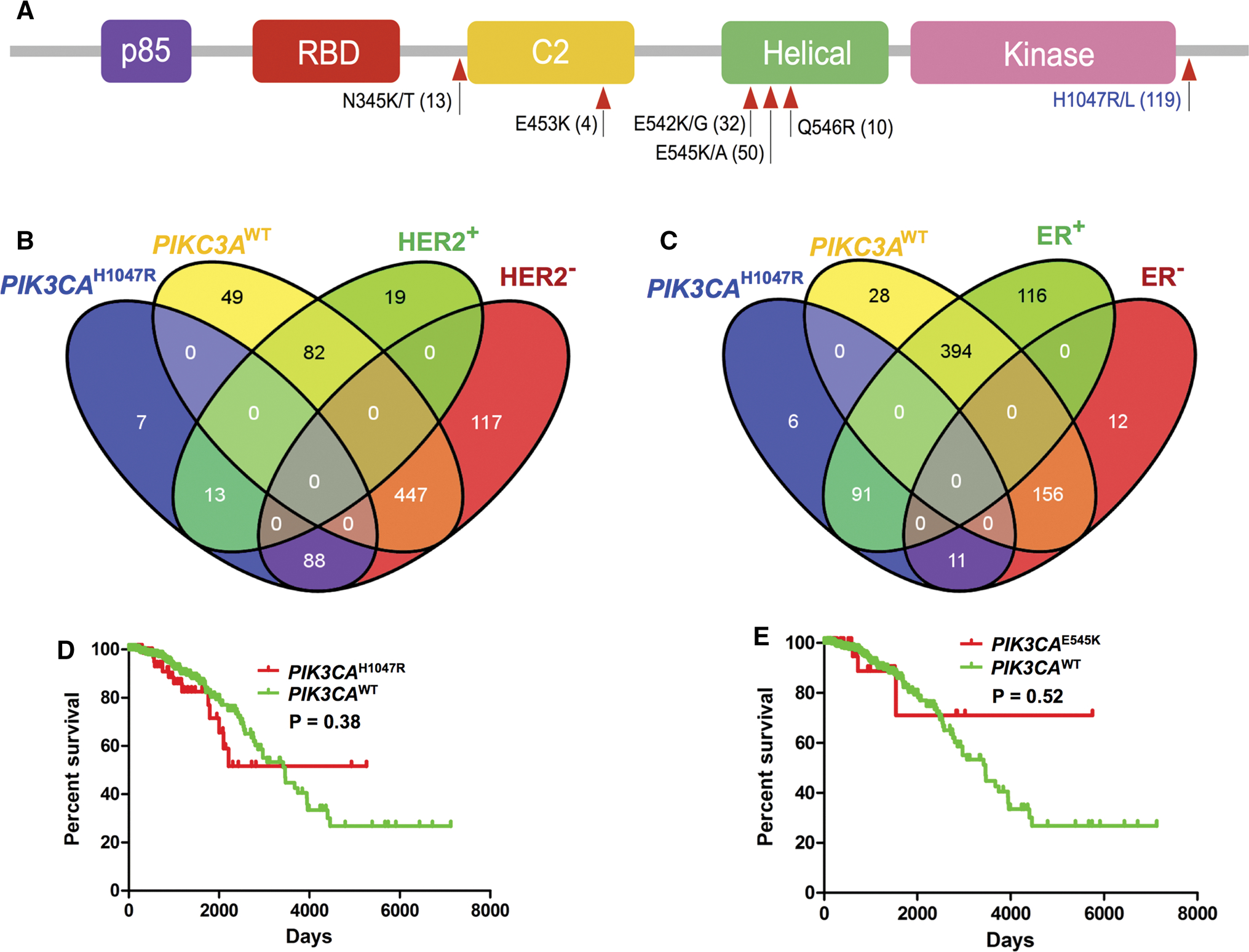

We first surveyed the spectrum of PIK3CA hotspot mutations in breast cancer using TCGA data. Figure 1a shows several hotspot mutations, including N345K/T, E542K/G, and E545K/A in the helical domain, and H1047R/L in the kinase domain. We next checked the PIK3CA mutations in different breast cancer subtypes. Among the 119 patients with the PIK3CAH1047R mutation, 10.9 % (13/119) patients harbored HER2+PIK3CAH1047R, whereas 76.5 % (91/119) patients had ER+PIK3CAH1047R (Fig. 1b, c). We further performed Kaplan survival analysis for PIK3CA mutant versus PIK3CAWT groups. Figure 1d, e showed that there was no significant relationship of overall survival rates between patients with PIK3CAH1047R and PIK3CAWT (P = 0.380), or between PIK3CAE545K and PIK3CAWT (P = 0.522) groups. This result is consistent with a previous study [13]. In addition, there was no significant relationship of overall survival rates for HER2 + or ER + breast cancer patients with or without PIK3CAH1047R or PIK3CAE545K mutations (P > 0.1, Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Spectrum of hotspot mutations in PIK3CA across subtypes of breast cancer. a Spectrum of hotspot mutations of PIK3CA in breast cancer based on The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data (December 2015). b and c Overlap of mutations in PIK3CAH1047R or PIK3CAWT patients with two other subtypes of breast cancer: anti-epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive (HER2+) or negative (HER2−) (b) and estrogen receptor positive (ER+) or negative (ER−) (c). d and e, Kaplan–Meier overall survival rates for breast cancer patients with or without two PIK3CA hotspot mutations (H1047R and E545K) using TCGA data [7, 8]. All P values of Kaplan–Meier survival analysis were performed using a log-rank test

Oncogenic signaling pathways altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer

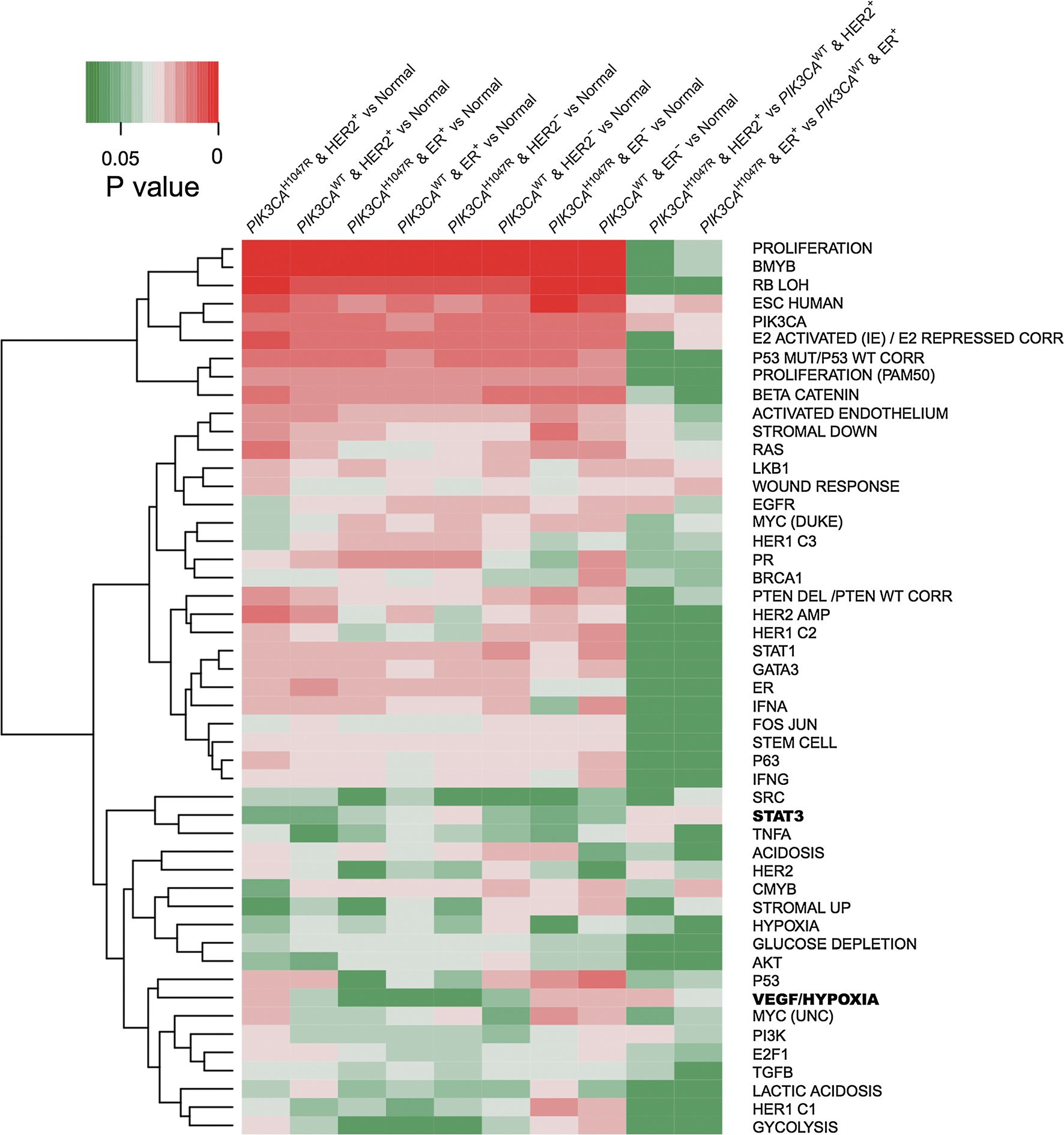

To investigate the signaling pathways altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer, we examined the enrichment of the significantly up-regulated genes across 10 different categories (Supplementary Table 1) using a panel of 52 previously well-defined gene expression signatures in breast cancer [34]. We calculated gene differential expression using RNA-seq read count data generated from the TCGA breast cancer project [7]. We defined the significantly over-expressed genes by q value threshold < 0.01 and log2(FC) > 1, where FC denotes fold change. We then performed gene set enrichment analysis (see “Materials and methods” section) for the 10 significantly up-regulated gene sets (Supplementary Table 1) against the 52 well-defined gene expression signatures (Supplementary Table 2) [34] using Fisher’ exact test. Several well-known breast cancer gene signatures (Supplementary Table 2), such as PIK3CA signaling, proliferation, mutant p53 signaling (P53 MUT), beta catenin activation (βCATENIN), LKB1 signaling, BMYB signaling (BMYB), and loss of RB expression (RB LOH), were found to be significantly active in breast cancer when compared to normal tissues (Fig. 2). Interestingly, Stat3 activation (STAT3), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFA), and vascular endothelial growth factor/hypoxia signaling (VEGF/hypoxia) were selectively altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer (Fig. 2). For example, VEGF/hypoxia (P = 6.8 × 10−3) were selectively activated in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R compared to that of the HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroup. Hypoxia is an important cancer cell metabolism pathway involved in a variety of cancer types or subtypes [35]. For instance, Ghazoui et al. found that a hypoxia metagene mediated the resistance of aromatase inhibitor in breast cancer [36]. In addition, a well-known breast cancer signaling, STAT3, is activated in both HER2+PIK3CAH1047R (P = 0.036) and ER+PIK3CAH1047R (P = 0.060) compared to HER2+PIK3CAWT and ER+PIK3CAWT subgroups respectively. Finally, TNFA is selectively activated in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R (P = 0.015) compared to that of the HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroup. As above, cancer cell metabolism pathway (e.g., VEGF/hypoxia) and tumor necrosis factor alpha pathway altered by PIK3CA mutations might play critical roles in HER2+ breast cancer.

Fig. 2.

Heat map showing oncogenic pathways altered by PIK3CAH1047R across 10 different subgroups of breast cancer. A panel of 52 well-annotated gene signatures representing the main oncogenic pathways in breast cancer was collected from a previous study [34]. The P value indicates the statistical significance of enrichment analysis for the up-regulated genes (Supplementary Table 1) in each subgroup of breast cancer compared to normal breast tissues across 52 well-annotated gene signatures (Supplementary Table 2) using Fisher’s exact test. Gene differential expression analysis was performed based on the breast invasive carcinoma dataset (RNA-seq, read count) from TCGA. The significantly up-regulated genes by cutoff: log2(FC) < 1 and adjusted P value > 0.01 were used for 52 well-annotated gene signature enrichment analyses. Two interesting pathways, VEGF/Hypoxia and STAT3, were highlighted in bold at the right side and discussed in main text

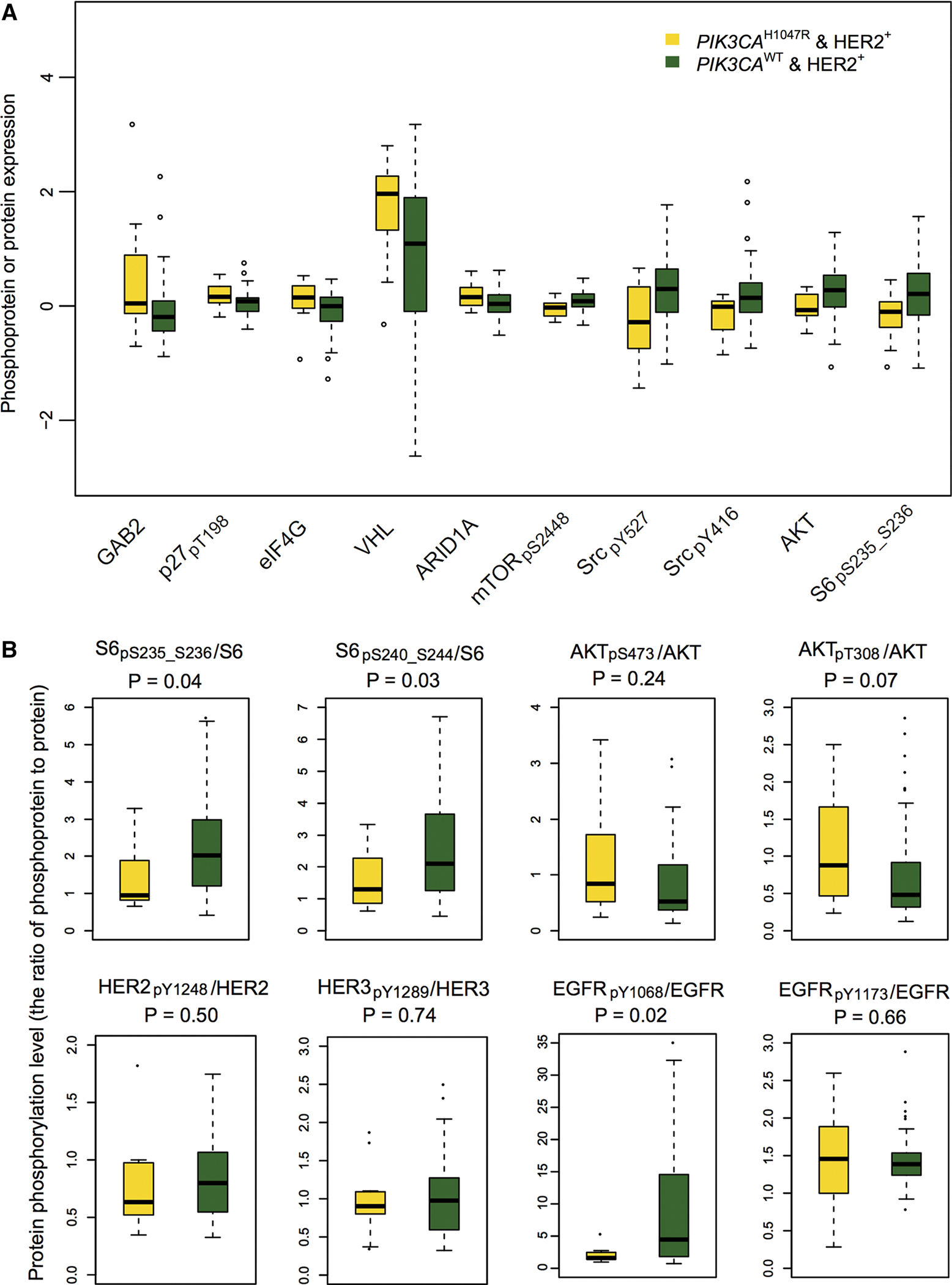

Elevated eIF4G and hypo-phosphorylation of EGFR in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer

We next examined the differentially expressed proteins/phosphoproteins using RPPA data. Figure 3a shows the top 5 up-regulated and down-regulated proteins/phosphoproteins that had the lowest P value in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients compared to the HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroup (Supplementary Table 3). In this study, we labeled the phosphorylation sites in phosphoprotein via subscript text. The top 5 upregulated proteins are GAB2 (P = 0.02, Wilcoxon rank-sum test), p27pT198 (P = 0.02), eIF4G (P = 0.03), VHL (P = 0.03), and ARID1A (P = 0.03). Bocanegra et al. reported that GAB2 plays oncogenic roles by enhancing epithelial cell proliferation and metastasis of HER2-driven murine breast cancer [37]. Larrea et al. found that RSK1 (an effector of PI3K/PDK1 pathway) drives p27pT198 to increase cell motility and metastatic potential of cancer cells [38]. Thus, GAB2 and p27pT198 might have oncogenic roles via PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+ breast cancer. The eIF4G, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma, is a protein mediating the transferring mRNA to the ribosome for translation initiation. Braunstein et al. found that eIF4G orchestrates a hypoxia-activated switch that promotes breast tumor angiogenesis and growth [39]. Furthermore, Fig. 2 indicates that VEGF/hypoxia is selectively altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+ breast cancer. Collectively, PIK3CAH1047R may be associated with an increase of eIF4G expression that subsequently promotes breast tumor angiogenesis and growth by regulating the hypoxia-activated switch in HER2+ breast cancer. More experimental work to validate this hypothesis will be needed in future.

Fig. 3.

Box plots showing the representative differential proteins or phosphoproteins in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R versus HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroups. a Top 5 up-regulated and down-regulated proteins or phosphoproteins (y-axis by protein expression) in HER2+ PIK3CAH1047R patients versus HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroup. b Box plot view showing the ratio of phosphoprotein to total protein level for 5 example proteins (S6, AKT, EGFR, HER2, and HER3) altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+ breast cancer. Protein or phosphoprotein differential analyses in this figure and Fig. 4 were performed based on the normalized RPPA protein expression data collected from TCPA [21]. The phosphorylation sites in phosphoprotein were labeled by subscript text. The P values were calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The detailed data are provided in Supplementary Table 3

The top 5 down-regulated proteins are mTORpS2448 (P = 0.01), SrcpY527 (P = 0.02), SrcpY416 (P = 0.02), AKT (P = 0.02), and S6pS235_S236 (P = 0.03). The details are shown in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 3. While AKT had low protein expression, the ratio of AKTpT308/AKT in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R was marginally higher than that in the HER2+PIK3CAWT group (P = 0.07, Fig. 3b), indicating a weak inactivation of AKT. Interestingly, we found that the ratios of both S6pS235_S236/S6 (P = 0.04) and S6pS240_S244/S6 (P = 0.03) in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients were lower than that in the HER2+PIK3CAWT group. In addition, HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients had a trend toward a decreased protein expression in ERBB family members, such as EGFRpY1068 (P = 0.03), HER3pY1289 (P = 0.04), HER2pY1248 (P = 0.07), and HER2 (P = 0.08), suggesting down-regulation of ERBB pathways in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients versus HER2+PIK3CAWT. Moreover, we found a hypo-phosphorylation of EGFR (P = 0.019) in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients compared to HER2+PIK3CAWT (Fig. 3b). These results suggested that PIK3CAH1047R might reduce the expression of phosphorylated EGFR in HER2+ breast cancer, consistent with PI3K-mediated feedback repression of ERBB family proteins (e.g., HER3) reported previously [40, 41]. Therefore, our result of low expression of ERBB proteins altered by PIK3CAH1047R might partially explain why the current ERBB family inhibitors could not completely block the PI3K pathway in HER2+ breast cancer.

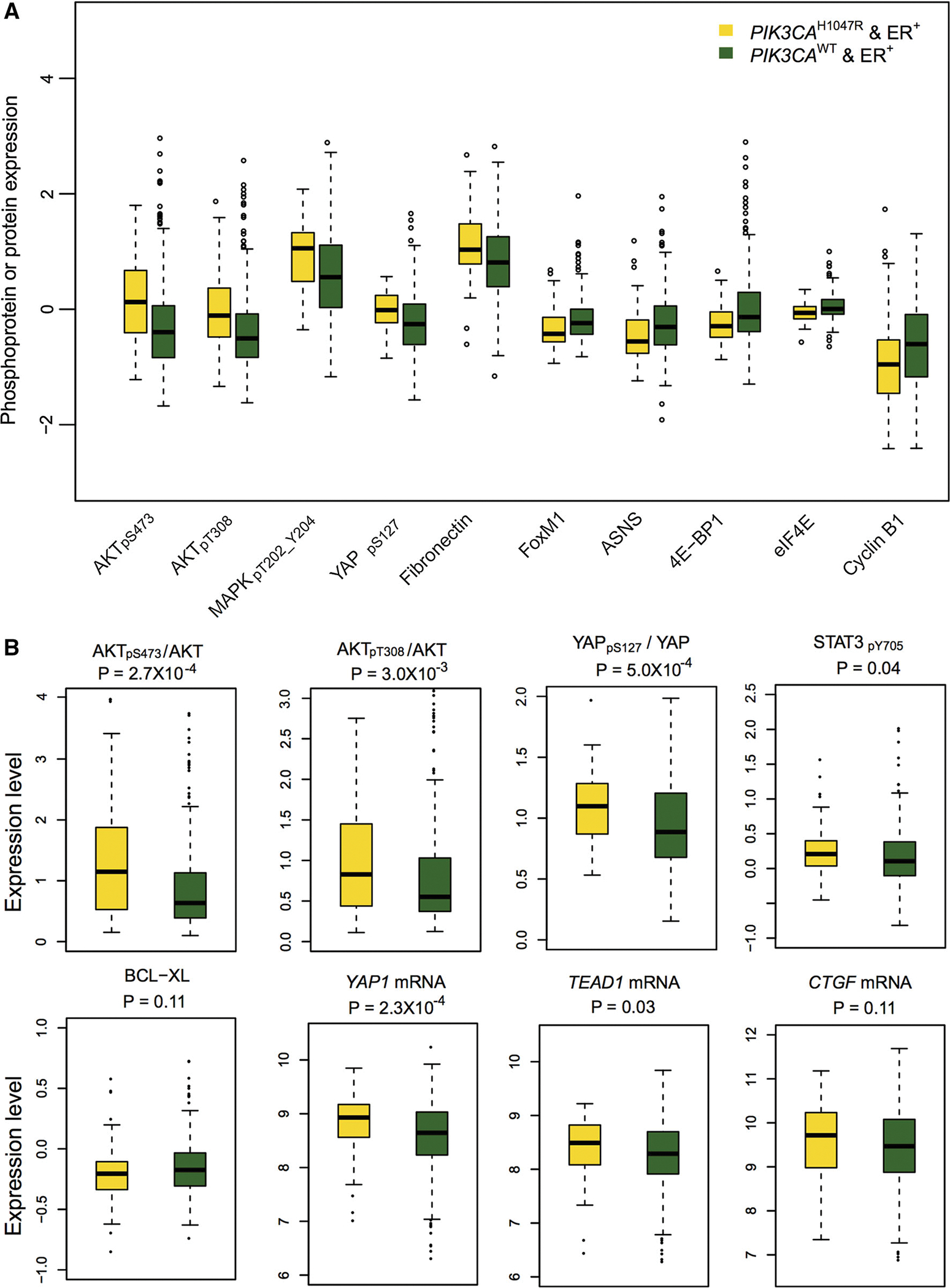

Activation of STAT3, MAPK, and AKT in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer

Next, we examined the differentially expressed proteins between ER+PIK3CAH1047R and ER+PIK3CAWT patients. Figure 4a showed the 10 most differentially expressed proteins based on the P values, including 5 up-regulated (AKTpS473, AKTpT308, MAPKpT202_Y204, YAPpS127, and Fibronectin) and 5 down-regulated (FoxM1, ASNS, 4E-BP1, eIF4E, and Cyclin B1) proteins or phosphoproteins. Interestingly, we found the elevated protein expression of MAPK, STAT3, and AKT in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients compared to ER+PIK3CAWT (Supplementary Table 3). For example, the ratios of both AKTpS473/AKT (P = 2.7 × 10−4, Wilcoxon test) and AKTpT308/AKT (P = 0.003) in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients were significantly higher than that in the ER+PIK3CAWT group, suggesting activation of the AKT pathway, as expected. The transcription factor STAT3 has been reported to be frequently active in breast cancer [42]. Figure 4b indicates an elevated phosphorylation level of STAT3 (STAT3pY705, P = 0.038) in ER+ PIK3CAH1047R patients compared to the ER+PIK3CAWT group. These findings revealed that ER and PIK3CAH1047R might co-activate multiple pathways involving STAT3, MAPK, and AKT in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer.

Fig. 4.

Box plots showing the representative differential proteins in ER+PIK3CAH1047R versus ER+PIK3CAWT subgroups. a The top 5 upregulated and down-regulated proteins or phosphoproteins (y-axis by protein expression) in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients versus ER+ PIK3CAWT subgroup, respectively. b Box plot view showing the ratio of phosphoprotein to total protein level for 2 representative proteins (AKT and YAP), phosphoprotein (STAT3) and protein (BCL-XL) differential expression, and mRNA differential expression for YAP1 and two YAP1 target genes (TEAD1 and CTGF) altered by PIK3CAH1047R in ER+ breast cancer. The phosphorylation sites in phosphoprotein were labeled by subscript text. The P values were calculated by Wilcoxon rank-sum test for protein differential expression analysis and by edgeR software for mRNA differential expression analysis. The detailed data are provided in Supplementary Table 3

An elevated phosphorylation level of YAP in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer

The Hippo pathway is an important kinase cascade signaling hub involved in organ growth and size maintenance, and it plays critical roles in various cancer types [43]. For instance, Hippo signaling inhibits a transcriptional co-activator and oncoprotein YAP/TAZ. Thus, Hippo plays a critical tumor suppressor role in various cancers, such as breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and liver cancer [43, 44]. As shown in Fig. 4a, we found an elevated expression of phosphorylated YAP (YAPpS127, P = 6.2 × 10−5) in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients compared to the ER+ PIK3CAWT group. Moreover, the ratio of YAPpS127/YAP in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients was significantly higher than that in the ER+PIK3CAWT group (P = 5.0 × 10−4). Activation of the Hippo tumor suppressor leads to YAP phosphorylation and cytoplasmic retention of YAP by the 14–3–3 binding and proteasome-dependent degradation [45]. However, when the Hippo pathway is under dysregulation, YAP is free to translocate into nucleus and then activates the transcription process of the genes that promote tumor growth and migration, such as CTGF, ANKRD1, CYR61, and AREG [46]. As shown in Fig. 4b, although YAP1 is slightly over-expressed at the mRNA level (P = 2.3 × 10−4), several target genes (CTGF [P = 0.11] and YEAD1 [P = 0.031]) revealed a weak or non-significant over-expression in ER+PIK3CAH1047R when compared to the ER+PIK3CAWT patients. This observation is consistent with no significant correlation (R = 0.063, P = 0.22 [F statistics]) between mRNA expression of TEAD1 and YAPpS127 expression or a significant positive correlation (R = 0.251, P = 6.1 × 10−5) between mRNA expression of CTGF and YAPpS127 expression in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients (Supplementary Fig. S2). The inconsistent correlation of YAPpS127 expression with its down-regulated gene (CTGF and TEAD1) mRNA expression might be caused by protein’s post-translational modifications or tumor heterogeneity in breast cancer as discussed previously [47]. The previous study has suggested that a high YAP phosphorylation level could be elevated by a highly active Hippo pathway, leading to inactivate transcription of YAP target genes [45]. Hence, our observation of the low transcription activities for several YAP target genes (e.g., CTGF and YEAD1) might be caused by the elevated phosphorylation of YAP. For example, we next observed a slightly low expression (Fig. 4b) of a YAP’s downstream protein, BCL-XL, and a significant negative correlation (R = −0.122 and P = 0.016 [F statistics]) between YAPpS127 expression and BCL-XL protein expression in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients (Supplementary Fig. S2). This is consistent with a previous study [48]. Collectively, the results supported that PIK3CAH1047R might activate the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway in ER+ breast cancer.

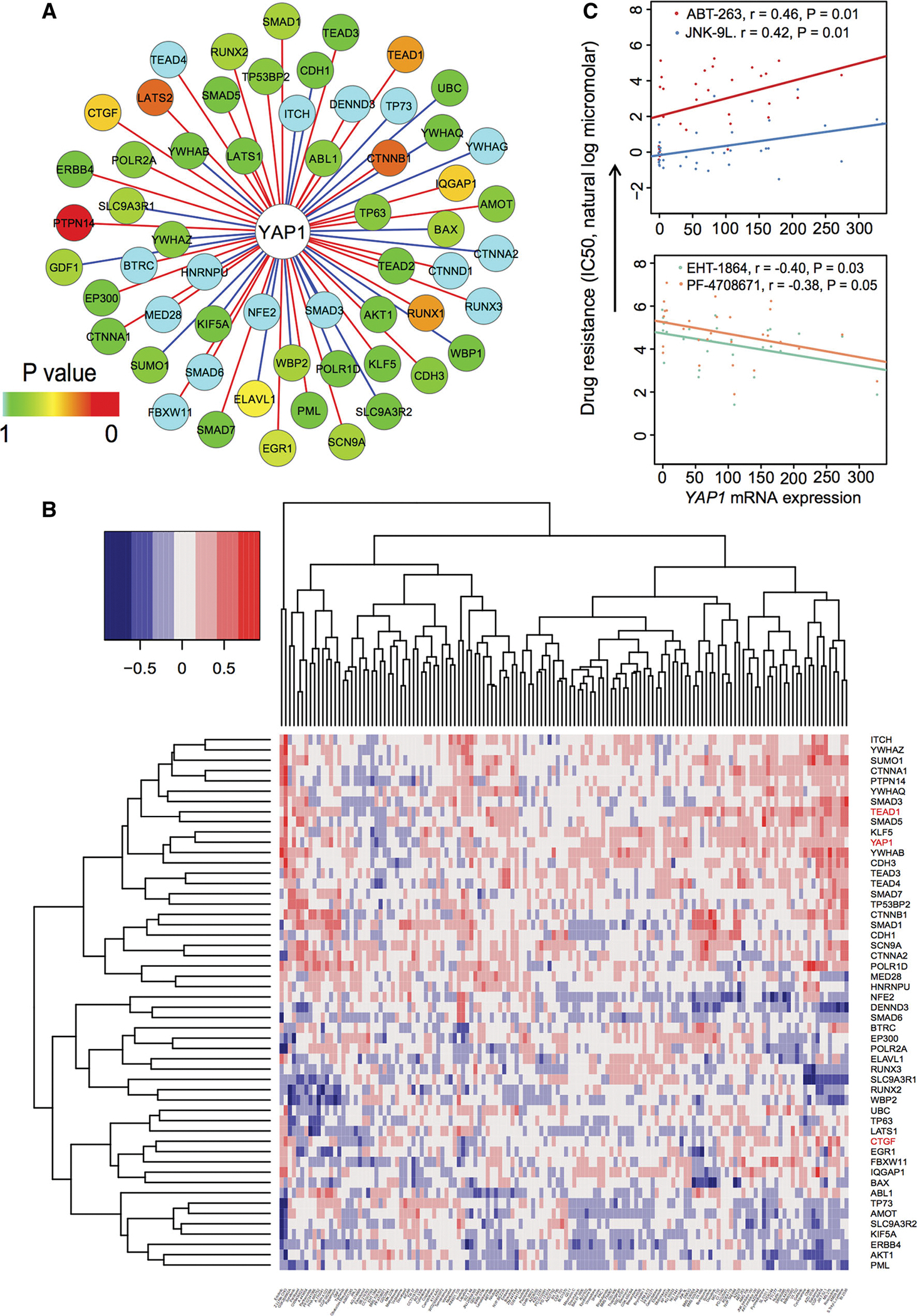

We next constructed a gene co-expression-weighted PIN to further explore the potential downstream events due to the Hippo pathway activation in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. First, we collected protein–protein interactions for YAP from several publicly available databases as described in our previous studies [27–29]. In total, we found 58 interacting proteins that are either experimentally validated or literature-curated for YAP, including physical interactions and phosphorylation reactions (kinase-substrate interactions) as described in our previous studies [27–29, 49, 50]. We then calculated gene co-expression correlation measured by PCC value using RNA-seq data and mapped the PCC value of each gene co-expression pair onto the above PIN as the weight. As shown in Fig. 5a, we found 8 significantly negative co-expressed partners (blue lines) and 24 significantly positive co-expressed partners (red lines) with P value < 0.01 (F statistics). The top 5 positive co-expressed partners with the lowest P-values in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer are PTPN14 (PCC = 0.66, P = 7.9 × 10−13), CTNNB1 (PCC = 0.57, P = 4.0 × 10−9), LATS2 (PCC = 0.57, P = 5.4 × 10−9), RUNX1 (PCC = 0.53, P = 5.5 × 10−8), and TEAD1 (PCC = 0.52, P = 1.8 × 10−7). A previous study showed that PTPN14 is required for the density-dependent control of YAP1 [51]. Guo et al. found LATS2-mediated YAP phosphorylation in hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis [52]. Browne et al. found that RUNX1 is associated with breast cancer progression and invasion [53]. Moreover, TEAD1 was reported as a major YAP1 target gene in breast cancer cell lines [54]. In summary, the elevated YAP1 phosphorylation level is a common feature in a subtype of breast cancer, which may be altered by PIK3CAH1047R in ER+ breast cancer.

Fig. 5.

A gene co-expression-weighted protein interaction subnetwork for YAP1 and the relationship between mRNA expression and drug responses in breast cancer cell lines based on the GDSC dataset [55]. a A gene co-expression-weighted protein interaction subnetwork connecting YAP1 and its 58 interacting proteins. The red edges denote positive co-expression and blue edges denote negative co-expression. The different color keys on nodes represent significance (P values) of gene co-expression measured by F statistics. Gene co-expression analysis was performed based on ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast invasive carcinoma dataset (RNA-seq with V2 RSEM) from TCGA. b Heat map showing the Pearson correlation coefficient (color key) between drug responses and gene mRNA expression for YAP1 and its 58 interacting genes based on the GDSC dataset [55] including 130 drugs’ response data (IC50, the natural log micromolar) and microarray expression across 53 breast cancer cell lines. The labels at the right side are genes and in the bottom are drugs. YAP1 and its two important target genes (TEAD1 and CTGF) were highlighted by red. c Four significant correlation (r: Pearson correlation coefficient) pairs between YAP1 mRNA expression and drug resistance. The P values were performed by F statistics

Elevated YAP1 expression correlates with the resistance of targeted chemotherapy agents in breast cancer cell lines

A previous study reported that the elevated YAP1 expression promotes the resistance to multiple anticancer agents [48]. We next examined the correlation between YAP1 mRNA expression and resistance of anticancer agents in breast cancer cell lines. We collected both drug treatment and gene expression data in 53 breast cancer cell lines from the GDSC database [55]. The heat map in Fig. 5b summarizes the overall correlation of the expression of 59 genes (YAP1 and its 58 interacting partners in Fig. 5a) with their responses (measured by IC50 natural log micromolar) to 132 drugs. Among the 132 anticancer agents, we found that the elevated YAP1 expression was significantly associated with resistance to ABT.263 (r = 0.46, P = 0.01 [F statistics]) and JNK-9L (r = 0.42, P = 0.01) (Fig. 5c). ABT.263 (navitoclax), an oral BCL-2 family inhibitor (BCL-2, BCL-XL and BCL-W), is under clinical investigation for various cancer treatments, including leukemia, lung cancer, breast cancer, and multiple myeloma [56]. Although overexpression of the pro-survival protein BCL-2 is common in breast cancer [57], we found that the BCL-2 family inhibitor (navitoclax) might have a resistance risk in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer due to the low expression of BCL-XL, which is inhibited by the elevated phosphorylation level of YAP (Fig. 4b). We found that the elevated YAP1 expression was associated with the sensitivity of two additional drugs: EHT-1864 (r = −0.40, P = 0.03) and PF-4708671 (r = −0.38, P = 0.05) (Fig. 5c). EHT-1864 is a small molecule inhibitor of RAC family small GTPases (RAC1) [58]. Giehl et al. reported that short-term pharmacological inhibition of RAC1 activity by EHT-1864 reduced the expression of a YAP target gene CTGF in HKC-8 cells [59]. Furthermore, a recent study has suggested that EHT-1864 might be a potential therapeutic molecule in breast cancer [60]. Katz et al. found that EHT-1864 blocked the spread of human breast cancer by downregulating STAT3 activity [61]. In the present study, we observed the elevated protein levels of STAT3, MAPK, and AKT in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer (Fig. 4). Therefore, a RAC family inhibitor, such as EHT-1864, might provide a potential agent or combinatorial therapy by down-regulation of STAT3, MAPK, and AKT pathways in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer.

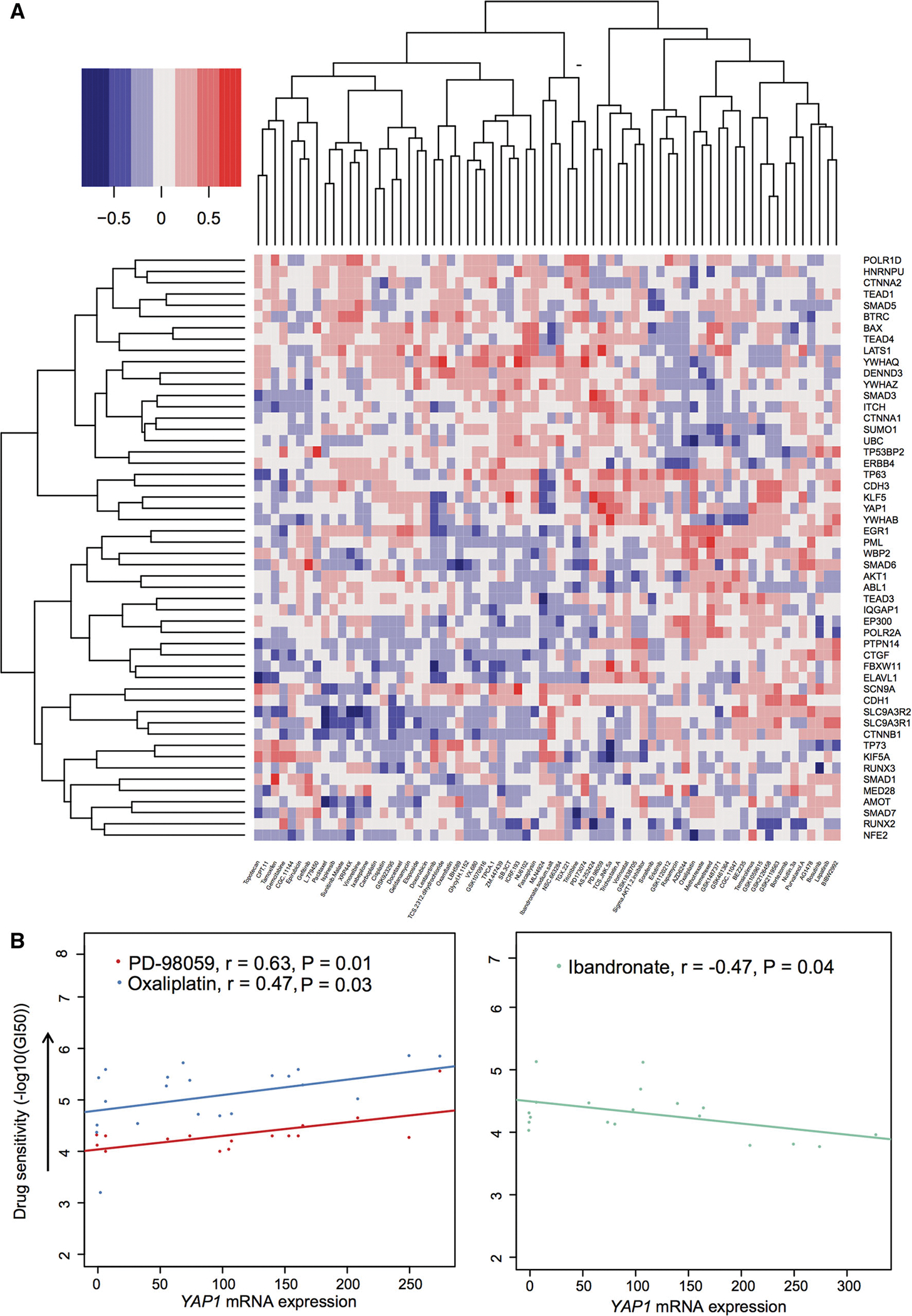

We further examined the correlation of YAP1 expression with the resistance of anticancer agents in breast cancer cell lines using an independent SU2C dataset [26]. We collected 45 different breast cancer cell lines having both 74 therapeutic drug treatments and gene expression profiles from SU2C [26]. The heat map in Fig. 6a displays the correlation between YAP1 mRNA expression and its 58 interacting protein partners and 74 anticancer therapeutic drugs in response (−log10(GI50) value). Figure 6b indicated that the elevated expression of YAP1 was significantly associated with the resistance of ibandronate (r = −0.47, P = 0.04) based on the SU2C dataset. Although ibandronate provides a potential therapy for metastatic breast cancer [62], we found that ibandronate might have a potential risk of drug resistance in ER+ PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. Among the 74 therapeutic drugs we examined, the elevated mRNA expression of YAP1 was found to be significantly associated with sensitivity to PD-98059 (r = 0.63, P = 0.01) and oxaliplatin (r = 0.47, P = 0.03), respectively (Fig. 6b). Oxaliplatin is a platinum-based chemotherapeutic drug for colon cancer and breast cancer [63]. PD-98059, a MEK/MAPK inhibitor, has been widely investigated for various cancer treatments. In addition, Fig. 4a shows a high activation of MAPK in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. Altogether, combining a MEK/MAPK inhibitor with known anti-endocrine agents may enhance tumor repression in ER+ PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer.

Fig. 6.

Relationship between YAP1 mRNA expression and drug responses in breast cancer cell lines based on the SU2C dataset [26]. a Heat map showing the Pearson correlation coefficient (color key) between drug responses and gene expression for YAP1 and its 58 interacting genes based on the SU2C dataset [26] containing 73 drugs’ response data (−log10(GI50)) and microarray expression across 45 breast cancer cell lines. The labels at the right side are genes and in the bottom are drugs. b Three significant correlation (r: Pearson correlation coefficient) pairs between YAP1 mRNA expression and drug sensitivity. The P values were performed by F statistics

Discussion

Drug resistance in current anti-HER2 or anti-ER therapies is a big obstacle in HER+/ER+ breast cancer. Previous studies have shown that HER2 and PIK3CAH1047R cooperate to promote transformation of the mammary epithelium and metastasis and cause breast tumor heterogeneity [9–11]. Furthermore, a hyper-activation of the PI3K pathway helps the escape from hormone dependence in ER+ breast cancer cell lines [16]. However, PIK3CA mutations have shown inconsistent clinical utility for anti-HER2 or anti-endocrine therapeutic agents in HER+/ER+ breast cancer patients, as reported in several large-scale clinical trials [13, 17]. The underlying mechanisms of PIK3CA mutations contributing to the resistance of anti-HER2 or anti-endocrine agents in breast cancer remain unclear. In this study, we developed an integrative bioinformatics approach to investigate the potential synergistic mechanisms of PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer. Through an integration of RNA-Seq, protein expression, drug pharmacological data, and microarray gene expression in breast cancer patients or breast cancer cell lines, we found several interesting molecular events that were potentially altered by PIK3CAH1047R. These results, while requiring further functional and clinical validation, provided useful insights into the functional consequences of PIK3CAH1047R-driven breast tumorigenesis and resistance to known chemotherapeutic agents in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer.

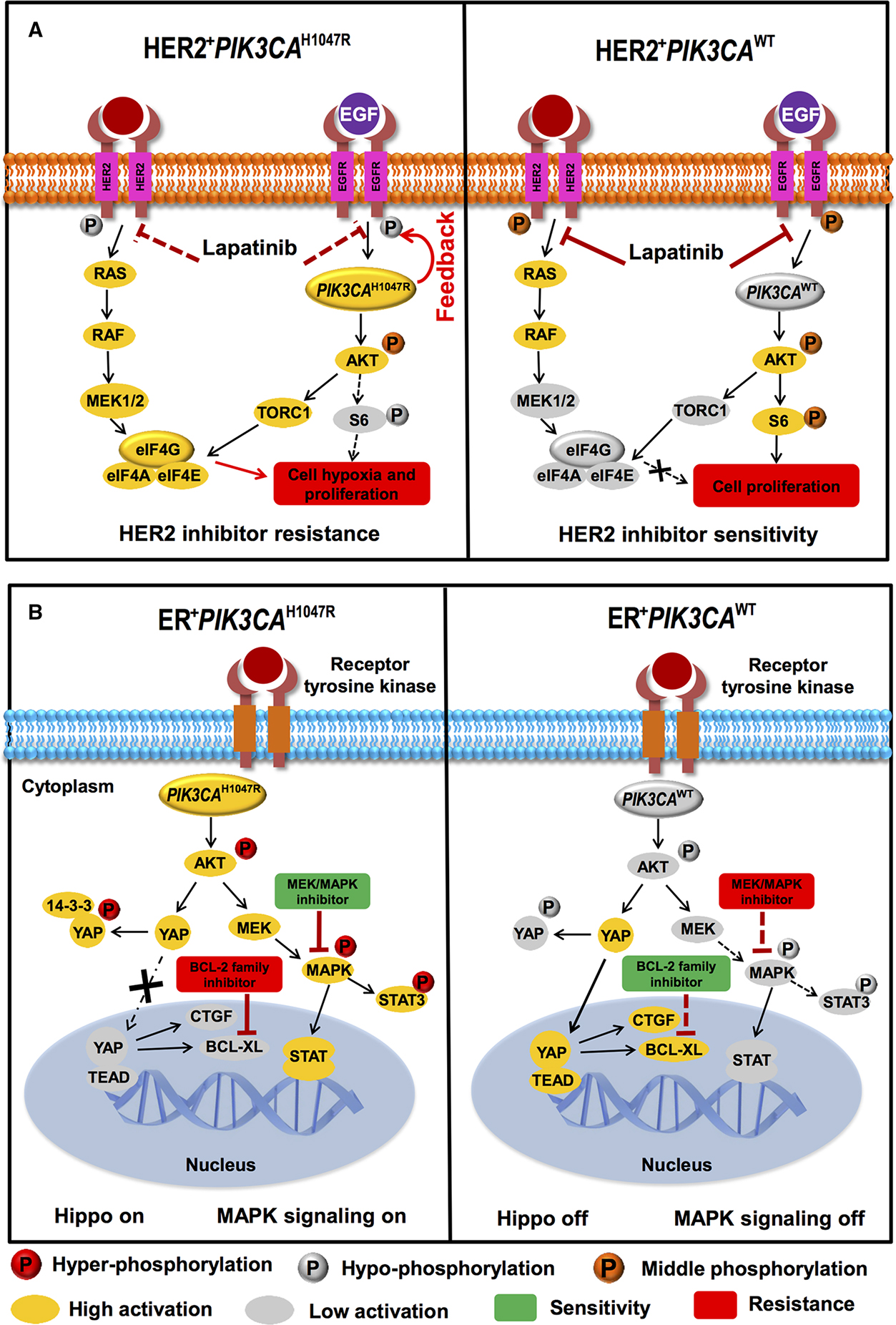

The clinical use of anti-HER2 targeted agents has yielded a substantial and positive impact on the survival of HER2+ breast cancer patients [3]. However, several previous studies reported potential resistance to anti-HER2 therapies in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer [13, 14]. Herein, we found the decreased activation of the ERBB pathway in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. For example, the hypo-phosphorylation of EGFR was observed in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients when compared to the HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroup (Fig. 3b). In addition, we found a weak activation of AKT and a low activation of S6 (Fig. 3a) in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer, consistent with the low activation of the ERBB pathway. One possible mechanism for the decreased activation of the ERBB pathway in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer might be explained by the PI3K-mediated feedback repression of ERBB family proteins (e.g., HER3), as reported in previous studies [40, 41]. We speculated that the decreased expression of ERBB proteins altered by PIK3CAH1047R might contribute to the inconsistent clinical utilities of anti-HER2 therapies (e.g., lapatinib) in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer (Fig. 7a). Thus, a combination of anti-HER2 targeted agents with other targeted agents, such as PI3K/AKT inhibitors, may potentially improve the clinical efficacy in anti-HER2 therapies for HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer patients [11]. Interestingly, we found that VEGF/hypoxia and STAT3 signaling pathways were selectively altered by HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. Furthermore, a hypoxia-activated switch (eIF4G) reveals a higher expression in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients than that in the HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroup. We proposed that the elevated eIF4G might promote cell hypoxia and proliferation in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer [39, 64, 65], as shown in Fig. 7a.

Fig. 7.

Proposed models for illustrating potential molecular mechanisms altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+ (a) or ER+ (b) breast cancer. a Hypo-phosphorylation of EGFR altered by PIK3CAH1047R may correlate with potential resistance of pan-ERBB inhibitors (e.g., Lapatinib) due to PI3K-mediated feedback repression of ERBB family proteins as described in the previous studies [40, 41]. b Elevated phosphorylation level of YAP (“Hippo on”) is a common feature in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer compared to ER+ PIK3CAWT. This may contribute to the potential activation of MAPK and STAT3 pathways and further correlate with the sensitivity of MEK/MAPK inhibitors

Although PIK3CA mutations commonly occur in HER2+ breast cancer, PIK3CA is more frequently mutated in ER+ breast cancer (Fig. 1b, c). Recent studies reported that actionable mutations in the PI3K/AKT pathway often mediate the resistance of anti-endocrine agents in breast cancer [16–18]. Therefore, it is critical to identify the molecular events involved in the resistance of anti-endocrine agents and altered by PIK3CA mutations in ER+ breast cancer. For this purpose, our analyses revealed that ER and PIK3CAH1047R might synergistically activate the Hippo pathway in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. For example, the elevated phosphorylation of YAP was observed in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients compared to the ER+PIK3CAWT subgroup. We speculated that YAP might not easily translocate into nucleus because of its hyperphosphorylation in cytoplasm (Fig. 7b) triggered by the high activation of AKT [45] (Fig. 4b). Our speculation is consistent with the transcriptional inactivation of several tumor growth and migration-related YAP1 target genes (e.g., TEAD1 and CTGF in Fig. 4b) in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, our analyses found that the elevated mRNA expression of YAP1 was significantly associated with the resistance to the BCL-2 family inhibitor (Fig. 5c). Thus, combining BCL-2 inhibitors with anti-endocrine agents might lead to potential risk of resistance in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, the elevated mRNA expression of YAP1 was significantly associated with the sensitivity to a MEK/MAPK inhibitor, PD-98059, in breast cancer cells (Fig. 6b). Hence, combining MEK/MAPK inhibitors with anti-endocrine agents might provide potential alternative therapies in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. Although ER+PIK3CAH1047R tumors are not dependent on the Hippo pathway to promote breast tumorigenesis, the activation of STAT3, MAPK, and AKT (Fig. 4) may drive tumorigenesis in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer (Fig. 7b). Collectively, our data suggested that combining STAT3/MAPK/AKT inhibitors with anti-endocrine agents might help to overcome the resistance of current therapies in ER+PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer.

In addition to PIK3CAH1047R, several helical domain mutations, such as PIK3CAE545K, were frequently mutated in breast cancer [7]. For example, totally 50 patients with PIK3CAE545K have protein expression data based on the released data in the current TCGA breast cancer project [7, 8]. We found both similar and unique patterns of the differentially expressed proteins/phosphoproteins altered by PIK3CAE545K across HER+ or ER+ breast cancer patients via our integrative bioinformatics framework (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The top 5 up-regulated proteins are PR (P = 9.7 × 10−3, Wilcoxon rank-sum test), Fibronectin (P = 0.013), STAT3pY705 (P = 0.030), NDRG1pT346 (P = 0.034), and C.RafpS338 (P = 0.039) in HER2+PIK3CAE545K compared to HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 1). Both PIK3CAH1047R and PIK3CAE545K activate the PI3K pathway, but they show different mechanisms of activation, such as eIF4G. Specifically, a decreased eIF4G expression was altered by PIK3CAE545K compared to the elevated eIF4G level (Fig. 3) altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+ breast cancer. The possible explanation is that different gene regulatory networks or miRNA regulation altered by PIK3CAH1047R or PIK3CAE545K result in different up- or down-regulation of eIF4G. The top 5 up-regulated proteins are Annexin.1 (P = 4.5 × 10−4), YAPpS127 (P = 5.8 × 10−4), Fibronectin (P = 1.1 × 10−3), XBP1 (P = 1.3 × 10−3), and YAP (P = 3.3 × 10−3) in ER+PIK3CAE545K compared to ER+PIK3CAWT subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, the activation of Hippo tumor suppressor pathway may be altered by both PIK3CAE545K and PIK3CAH1047R (Fig. 4) in ER+ breast cancer. Altogether, the integrative bioinformatics framework presented in this study would provide a powerful tool to identify specific pathways altered by particular driver mutations (e.g., PIK3CAH1047R and PIK3CAE545K) in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer.

There are several limitations in our integrative bioinformatics approach. First, we mainly focused on mRNA transcriptome and protein expression analyses. However, recent studies have shown that microRNA (miRNA) regulation or epigenetic changes may also be linked by driver mutations in cancer [27, 66]. Second, high breast tumor heterogeneity and small sample sizes might influence the reliability and power in the statistical tests in the present study. For example, there were only 13 HER2+ PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer patients that had both gene expression and protein expression data, which potentially affected the significance interpretation in gene or protein differential expression analysis. However, as we explained in other studies [66, 67], the panomics data [68] from the same samples or subgroups should be more effective in the integrative analysis like the present study. This is because cancer is highly heterogeneous and simply increasing sample size may introduce noise in genomic analysis. Of note, we found a weak trend of up-regulation of VHL and ARID1A in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R patients compared to the HER2+PIK3CAWT subgroup (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 3). However, several previous studies reported the tumor suppressor roles of both VHL [69] and ARID1A [70] in breast cancer. Third, inconsistencies of the measured drug pharmacological data may have potential data bias in breast cancer pharmacogenomics analyses [71]. Fourth, due to lack of subtype-specific information (like ER or HER2 status) for breast cancer cell lines from GDSC [24, 25] and SU2C [26] datasets, we only performed subtype-specific analysis with or without PIK3CAH1047R mutation for primary breast tumor samples collected from the TCGA project in the present study. Fifth, there is no drug (like PI3K-targeted agents) treatment information for breast cancer patients annotated in TCGA. Hence, the patient survival analysis should be investigated in patients who are treated with therapeutics targeting PI3K in future to comprehensively evaluate the clinical utility of targeting PIK3CA mutation in breast cancer. Finally, the results remain to be experimentally validated in terms of their function and clinical implications.

In future, we will perform more reliable bioinformatics analyses in four directions: (i) by integrating miRNA expression and transcriptional factor (TF)-miRNA regulatory networks to identify potential miRNA or TF regulatory networks altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer; (ii) by integrating methylation data from the TCGA breast cancer project to examine the potential epigenetic markers altered by PIK3CAH1047R in different subtypes of breast cancer; (iii) by integrating functional data generated from high-throughput functional screening technologies, such as RNAi and CRISPR-Cas9, to identify driver events altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer; and (iv) by building more comprehensive bioinformatics workflow by integrating genomics data and the quantitative radiomics data generated from the TCGA and The Cancer Imaging Archive (http://www.cancerimagingarchive.net) breast cancer projects to develop quantitative predictive PIK3CA mutant models for precision cancer medicine and patient treatment strategies in breast cancer.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed an integrative bioinformatics approach to investigate the potential synergistic mechanisms of PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+/ER+ breast cancer. We found that cancer cell metabolism-related pathways (e.g., VEGF/hypoxia and STAT3) were selectively altered by PIK3CAH1047R in HER2+ breast cancer. Protein differential analysis suggested that a higher eIF4G expression might promote the increased tumor angiogenesis and growth via regulating the hypoxia-activated switch in HER2+ PIK3CAH1047R breast cancer. We found the lower activities of the ERBB pathway (e.g., hypo-phosphorylation of EGFR) in HER2+PIK3CAH1047R, which may mediate resistance to the pan-ERBB inhibitors in HER2+ breast cancer. Moreover, we found an activation of the MAPK, STAT3, AKT, and Hippo pathways (e.g., the elevated phosphorylation of YAP) in ER+PIK3CAH1047R patients. Finally, an elevated mRNA expression of YAP1 was associated with the resistance to BCL-2 family inhibitors but with sensitivity to MEK/MAPK inhibitors in breast cancer cell lines. In summary, these findings generated some important hypotheses which could help us better understand the biological consequences of PIK3CAH1047R-driven breast tumorigenesis, uncover the resistance mechanisms on existing chemotherapeutic agents in HER2+ or ER+ breast cancer, and develop the enhanced molecular therapeutic strategies in this specific subtype of breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara O’Brien for improving the English in an early version of the manuscript. This work was partially supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (R01LM011177), The Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation, Ingram Professorship Funds (to Z.Z.), and a NIH Breast Cancer SPORE pilot project (to Z.Z.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of Interest No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10549-016-4011-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osmanbeyoglu HU, Pelossof R, Bromberg JF, Leslie CS (2014) Linking signaling pathways to transcriptional programs in breast cancer. Genome Res 24:1869–1880. doi: 10.1101/gr.173039.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arteaga CL, Engelman JA (2014) ERBB receptors: from oncogene discovery to basic science to mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell 25:282–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer IA, Arteaga CL (2016) The PI3K/AKT pathway as a target for cancer treatment. Annu Rev Med 67:11–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062913-051343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young CD, Zimmerman LJ, Hoshino D et al. (2015) Activating PIK3CA mutations induce an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) paracrine signaling axis in basal-like breast cancer. Mol Cell Proteomics 14:1959–1976. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.049783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcotte R, Sayad A, Brown KR et al. (2016) Functional genomic landscape of human breast cancer drivers, vulnerabilities, and resistance. Cell 164:293–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Genome Atlas Network (2012) Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciriello G, Gatza ML, Beck AH et al. (2015) Comprehensive molecular portraits of invasive lobular breast cancer. Cell 163:506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koren S, Reavie L, do Couto JP et al. (2015) PIK3CA induces multipotency and multi-lineage mammary tumours. Nature 525:114–118. doi: 10.1038/nature14669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Keymeulen A, Lee MY, Ousset M et al. (2015) Reactivation of multipotency by oncogenic PIK3CA induces breast tumour heterogeneity. Nature 525:119–123. doi: 10.1038/nature14665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanker AB, Pfefferle AD, Balko JM et al. (2013) Mutant PIK3CA accelerates HER2-driven transgenic mammary tumors and induces resistance to combinations of anti-HER2 therapies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:14372–14377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303204110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baselga J, Cortes J, Im SA, Clark E, Ross G, Kiermaier A, Swain SM (2014) Biomarker analyses in CLEOPATRA: a phase III, placebo-controlled study of pertuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive, first-line metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:3753–3761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.5384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loibl S, von Minckwitz G, Schneeweiss A et al. (2014) PIK3CA mutations are associated with lower rates of pathologic complete response to anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (her2) therapy in primary HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:3212–3220. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.7876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henry NL, Schott AF, Hayes DF (2014) Assessment of PIK3CA mutations in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: clinical validity but not utility. J Clin Oncol 32:3207–3209. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.6132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rexer BN, Chanthaphaychith S, Dahlman K, Arteaga CL (2014) Direct inhibition of PI3K in combination with dual HER2 inhibitors is required for optimal antitumor activity in HER2+ breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res 16:R9. doi: 10.1186/bcr3601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller TW, Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM et al. (2010) Hyperactivation of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase promotes escape from hormone dependence in estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer. J Clin Invest 120:2406–2413. doi: 10.1172/JCI41680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabine VS, Crozier C, Brookes CL et al. (2014) Mutational analysis of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in tamoxifen exemestane adjuvant multinational pathology study. J Clin Oncol 32:2951–2958. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.8272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller TW, Rexer BN, Garrett JT, Arteaga CL (2011) Mutations in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway: role in tumor progression and therapeutic implications in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 13:224. doi: 10.1186/bcr3039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng F, Zhao J, Zhao Z (2015) Advances in computational approaches for prioritizing driver mutations and significantly mutated genes in cancer genomes. Brief Bioinform 17(4):642–656. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao J, Cheng F, Wang Y, Arteaga CL, Zhao Z (2016) Systematic prioritization of druggable mutations in approximately 5000 genomes across 16 cancer types using a structural genomics-based approach. Mol Cell Proteomics 15:642–656. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.053199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Lu Y, Akbani R et al. (2013) TCPA: a resource for cancer functional proteomics data. Nat Methods 10:1046–1047. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blair BG, Wu X, Zahari MS et al. (2015) A phosphoproteomic screen demonstrates differential dependence on HER3 for MAP kinase pathway activation by distinct PIK3CA mutations. Proteomics 15:318–326. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu Y, Qiu P, Ji Y (2014) TCGA-assembler: open-source software for retrieving and processing TCGA data. Nat Methods 11:599–600. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang W, Soares J, Greninger P et al. (2013) Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D955–961. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garnett MJ, Edelman EJ, Heidorn SJ et al. (2012) Systematic identification of genomic markers of drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Nature 483:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nature11005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heiser LM, Sadanandam A, Kuo WL et al. (2012) Subtype and pathway specific responses to anticancer compounds in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:2724–2729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018854108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, Jia P, Cheng F, Zhao Z (2015) Heterogeneous DNA methylation contributes to tumorigenesis through inducing the loss of coexpression connectivity in colorectal cancer. Genes Chromosom Cancer 54:110–121. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng F, Jia P, Wang Q, Zhao Z (2014) Quantitative network mapping of the human kinome interactome reveals new clues for rational kinase inhibitor discovery and individualized cancer therapy. Oncotarget 5:3697–3710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng F, Jia P, Wang Q, Lin CC, Li WH, Zhao Z (2014) Studying tumorigenesis through network evolution and somatic mutational perturbations in the cancer interactome. Mol Biol Evol 31:2156–2169. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng F, Liu C, Shen B, Zhao Z (2016) Investigating cellular network heterogeneity and modularity in cancer: a network entropy and unbalanced motif approach. BMC Syst Biol 10(Suppl 3):65. doi: 10.1186/s12918-016-0309-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vuong H, Cheng F, Lin CC, Zhao Z (2014) Functional consequences of somatic mutations in cancer using protein pocket-based prioritization approach. Genome Med 6:81. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0081-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK (2010) edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gatza ML, Silva GO, Parker JS, Fan C, Perou CM (2014) An integrated genomics approach identifies drivers of proliferation in luminal-subtype human breast cancer. Nat Genet 46:1051–1059. doi: 10.1038/ng.3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masson N, Ratcliffe PJ (2014) Hypoxia signaling pathways in cancer metabolism: the importance of co-selecting interconnected physiological pathways. Cancer Metab 2:3. doi: 10.1186/2049-3002-2-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghazoui Z, Buffa FM, Dunbier AK et al. (2011) Close and stable relationship between proliferation and a hypoxia metagene in aromatase inhibitor-treated ER-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 17:3005–3012. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bocanegra M, Bergamaschi A, Kim YH et al. (2010) Focal amplification and oncogene dependency of GAB2 in breast cancer. Oncogene 29:774–779. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larrea MD, Hong F, Wander SA, da Silva TG, Helfman D, Lannigan D, Smith JA, Slingerland JM (2009) RSK1 drives p27Kip1 phosphorylation at T198 to promote RhoA inhibition and increase cell motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9268–9273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805057106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braunstein S, Karpisheva K, Pola C et al. (2007) A hypoxia-controlled cap-dependent to cap-independent translation switch in breast cancer. Mol Cell 28:501–512. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrett JT, Olivares MG, Rinehart C et al. (2011) Transcriptional and posttranslational up-regulation of HER3 (ErbB3) compensates for inhibition of the HER2 tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:5021–5026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016140108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakrabarty A, Sanchez V, Kuba MG, Rinehart C, Arteaga CL (2012) Feedback upregulation of HER3 (ErbB3) expression and activity attenuates antitumor effect of PI3K inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:2718–2723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018001108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tkach M, Rosemblit C, Rivas MA et al. (2013) p42/p44 MAPK-mediated Stat3Ser727 phosphorylation is required for progestin-induced full activation of Stat3 and breast cancer growth. Endocr Relat Cancer 20:197–212. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan D (2010) The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell 19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haskins JW, Nguyen DX, Stern DF (2014) Neuregulin 1-activated ERBB4 interacts with YAP to induce Hippo pathway target genes and promote cell migration. Sci Signal 7:ra116. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basu S, Totty NF, Irwin MS, Sudol M, Downward J (2003) Akt phosphorylates the Yes-associated protein, YAP, to induce interaction with 14–3–3 and attenuation of p73-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell 11:11–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao B, Li L, Lei Q, Guan KL (2010) The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes Dev 24:862–874. doi: 10.1101/gad.1909210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mertins P, Mani DR, Ruggles KV et al. (2016) Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature 534:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature18003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin L, Sabnis AJ, Chan E et al. (2015) The Hippo effector YAP promotes resistance to RAF- and MEK-targeted cancer therapies. Nat Genet 47:250–256. doi: 10.1038/ng.3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng F, Zhao J, Fooksa M, Zhao Z (2016) A network-based drug repositioning infrastructure for precision cancer medicine through targeting significantly mutated genes in the human cancer genomes. J Am Med Inform Assoc 23:681–691. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng F, Murray JL, Zhao J, Sheng J, Zhao Z, Rubin DH (2016) Systems biology-based investigation of cellular antiviral drug targets identified by gene-trap insertional mutagenesis. PLoS Comput Biol 12:e1005074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang W, Huang J, Wang X, Yuan J, Li X, Feng L, Park JI, Chen J (2012) PTPN14 is required for the density-dependent control of YAP1. Genes Dev 26:1959–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.192955.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo C, Wang X, Liang L (2015) LATS2-mediated YAP1 phosphorylation is involved in HCC tumorigenesis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8:1690–1697 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Browne G, Taipaleenmaki H, Bishop NM, Madasu SC, Shaw LM, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB (2015) Runx1 is associated with breast cancer progression in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice and its depletion in vitro inhibits migration and invasion. J Cell Physiol 230:2522–2532. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J et al. (2008) TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev 22:1962–1971. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N et al. (2012) The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tse C, Shoemaker AR, Adickes J et al. (2008) ABT-263: a potent and orally bioavailable Bcl-2 family inhibitor. Cancer Res 68:3421–3428. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oakes SR, Vaillant F, Lim E et al. (2012) Sensitization of BCL-2-expressing breast tumors to chemotherapy by the BH3 mimetic ABT-737. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:2766–2771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104778108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shutes A, Onesto C, Picard V, Leblond B, Schweighoffer F, Der CJ (2007) Specificity and mechanism of action of EHT 1864, a novel small molecule inhibitor of Rac family small GTPases. J Biol Chem 282:35666–35678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703571200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giehl K, Keller C, Muehlich S, Goppelt-Struebe M (2015) Actinmediated gene expression depends on RhoA and Rac1 signaling in proximal tubular epithelial cells. PLoS One 10:e0121589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosenblatt AE, Garcia MI, Lyons L, Xie Y, Maiorino C, Desire L, Slingerland J, Burnstein KL (2011) Inhibition of the Rho GTPase, Rac1, decreases estrogen receptor levels and is a novel therapeutic strategy in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 18:207–219. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katz E, Sims AH, Sproul D, Caldwell H, Dixon MJ, Meehan RR, Harrison DJ (2012) Targeting of Rac GTPases blocks the spread of intact human breast cancer. Oncotarget 3:608–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cameron D, Fallon M, Diel I (2006) Ibandronate: its role in metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist 11(Suppl 1):27–33. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-90001-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kelland L (2007) The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gupta SC, Singh R, Pochampally R, Watabe K, Mo YY (2014) Acidosis promotes invasiveness of breast cancer cells through ROS-AKT-NF-kappaB pathway. Oncotarget 5:12070–12082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hinnebusch AG (2012) Translational homeostasis via eIF4E and 4E-BP1. Mol Cell 46:717–719. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jiang W, Jia P, Hutchinson KE, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, Zhao Z (2015) Clinically relevant genes and regulatory pathways associated with NRASQ61 mutations in melanoma through an integrative genomics approach. Oncotarget 6:2496–2508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo X, Xu Y, Zhao Z (2015) In-depth genomic data analyses revealed complex transcriptional and epigenetic dysregulations of BRAFV600E in melanoma. Mol Cancer 14:60. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0328-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheng F, Hong H, Yang SY, Wei YQ (2016) Individualized network-based drug repositioning infrastructure for precision oncology in the panomics era. Brief Bioinform. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gossage L, Eisen T, Maher ER (2015) VHL, the story of a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Rev Cancer 15:55–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mamo A, Cavallone L, Tuzmen S et al. (2012) An integrated genomic approach identifies ARID1A as a candidate tumor-suppressor gene in breast cancer. Oncogene 31:2090–2100. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haibe-Kains B, El-Hachem N, Birkbak NJ, Jin AC, Beck AH, Aerts HJ, Quackenbush J (2013) Inconsistency in large pharmacogenomic studies. Nature 504:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature12831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.