Abstract

Extracranial vertebral artery dissection is a cerebrovascular disease that occurs most commonly in young people. A 32-year-old man experienced sudden cervical pain and was diagnosed with left vertebral artery dissection after arterial changes were identified by ultrasonography. The reduction in the size of an intramural hematoma in the left vertebral artery and in the peak systolic velocity were evaluated over time. Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and cerebral angiography are generally performed to diagnose and follow-up extracranial vertebral artery dissection; however, carotid ultrasonography has an advantage over these modalities by enabling the simultaneous observation of vascular morphology and hemodynamics.

Keywords: ultrasonography, vertebral artery dissection

Introduction

Vertebral artery dissection (VAD) is not rare in young people and is a major cause of stroke in this age group. The incidence of extracranial internal carotid artery in Europe and the United States is high, whereas that of intracranial vertebral artery is high in Japan (1,2); however, the incidence of extracranial vertebral artery dissection in the Japanese population is unknown.

A diagnosis of VAD is made based on changes in arterial morphology, which are identified by imaging examinations, including magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), computed tomographic angiography (CTA) (3), and digital subtraction angiography (DSA). These examinations cannot be performed frequently or easily and take a relatively long time to perform. Carotid ultrasonography, however, can be performed relatively easily and be used to evaluate the blood flow velocity as well as vascular morphology.

We herein report a case wherein carotid ultrasonography was useful for visualizing extracranial carotid artery dissection.

Case Report

A 32-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with the sudden onset of pain in the head and neck without any traumatic event. He had previously had high blood pressure but received no antihypertensive treatment. His height was 168 cm, and his weight was 57 kg, with a blood pressure at admission of 141/91 mmHg. Physical and neurological assessments were all normal. A blood analysis showed normal blood cells and normal coagulation activity. A biochemical examination revealed no abnormalities.

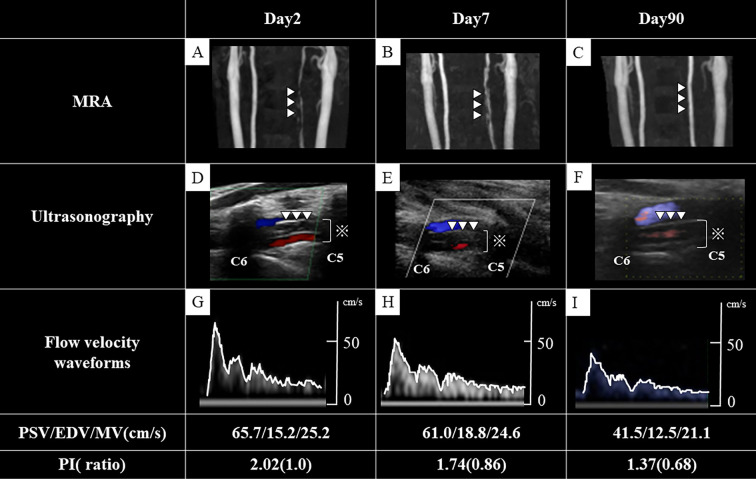

Carotid ultrasonography showed a flap and double lumen in the left vertebral artery (Figure D) and high peak systolic velocity (PSV) (65.7 cm/s) (Figure G). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed no areas of ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhaging, but MRA of the neck showed left vertebral artery stenosis (Figure A). In addition, intramural hematoma was seen in the V2 segment of the left vertebral artery on fat-suppressed T1-weighted imaging. We diagnosed him with extracranial vertebral artery dissection and initiated antihypertensive drugs and analgesic agents to keep his systolic and diastolic blood pressure below 120/70 mmHg.

Figure.

Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). MRA shows the extent of left vertebral artery stenosis and hematoma at presentation (A), improvement on day 7 (B), and normal left vertebral artery wall on day 90 (C). Ultrasonography shows a flap and double lumen in the left vertebral artery (D), vascular lumens (including false lumens; ※), improvement and slight reduction of the hematoma on day 7 (E), and normalization of the blood vessel wall on day 90 (F). Flow velocity waveforms on day 2 (G), day 7 (H), and day 90 (I) show a steady decrease in peak systolic velocity with time. The white lines trace the waveform (G-I).

MRA of the neck acquired seven days later visualized the left vertebral artery more clearly (Figure B). Ultrasonography showed a slight reduction in the size of the intramural hematoma (Figure E) and a reduced PSV (61.0 cm/s) (Figure H). His neck pain decreased and then disappeared during hospitalization, without any ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, and he was discharged on hospital day 8.

At 90 days after the onset, head and neck MRA showed a normalized vessel wall of the left vertebral artery (Figure C), and ultrasonography showed disappearance of the hematoma (Figure F), normalization of the blood vessel wall, and a decreased PSV (41.5 cm/s) (Figure I).

Discussion

This case demonstrates the usefulness of carotid ultrasonography for evaluating the vascular morphology and flow velocity in a patient with vertebral artery dissection. It can also visualize regression of the false lumen and reductions in the PSV over time.

MRA and carotid ultrasonography showed gradual improvement of VAD over a period of three months. Shibahara et al. observed that 14% of cases of VAD aggravation were identified within 1 month after the onset, and 50% of cases of VAD improvement occurred within 6 months after the onset (4). Therefore, our patient seems to have followed the typical course of VAD.

Administration of antiplatelet agents and/or anticoagulants has been reported as antithrombotic therapy for patients with ischemic symptoms of VAD (5,6); however, we did not administer antithrombotic agents or statins because our patient had only headaches and neck pain, with no signs of ischemic stroke.

MRI is currently recommended as the first-line modality for the diagnosis of cerebral artery dissection due to its non-invasiveness, lack of radiation, high sensitivity, and high specificity (7,8). In addition to MRI, ultrasonography can clearly identify intramural hematoma (9), and duplex color-flow imaging provides the hemodynamic parameters and pathological information of the vessel wall. Therefore, ultrasonography was a useful method for evaluating our patient with extracranial cerebral artery dissection.

The pulsatility index (PI) is a commonly used parameter for the objective assessment of the Doppler waveform. The PI falls with increasing proximal stenosis and rises with increasing peripheral resistance (10). A previous study reported that the ratio of follow-up and baseline PI values was significantly lower in the group with stenosis improvement than in the group without any marked improvement (11). In the present patient, the PI ratio was 0.68, which is consistent with the MRA and ultrasonography findings of improvement of the stenosis.

The PI is calculated as the difference between PSV and end-diastolic velocity (EDV) divided by the time average maximum velocity (TAMV). In the present patient, the decrease in the PSV and TAMV values over time caused the PI ratio to decrease as stenosis improved. In addition to a low PI ratio, decreased PSV and TAMV values may be similarly useful to MRA for assessing stenosis improvement.

Conclusion

Ultrasonography is useful in the diagnosis and follow-up of extracranial VAD. In addition to the PI ratio, the PSV and TAMV values on ultrasonography should be monitored in the follow-up of VAD.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Bejor Y, Daubail B, Debette S, et al. Incidence and outcome of cerebrovascular events related to cervical artery dissection; the Dijon Stroke Registry. Int J Stroke 9: 879-882, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kwon JY, Kim NY, Suh DC, et al. Intracranial and extracranial artery dissection presenting with ischemic stroke: lesion location and stroke mechanism. J Neurol Sci 358: 371-376, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Provenzale JM, Sarikaya B. Comparison of test performance characterisics of MRI, MR angiography, and CT angiography in the diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review of the medical literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol 193: 1167-1174, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shibahara T, Yasaka M, Wakugawa Y, et al. Improvement and aggravation of spontaneous unruptured vertebral artery dissection. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra 3: 153-164, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Markus HS, Hayter E, Levi C, et al. Antiplatelet treatment compared with anticoagulation treatment for cervical artery dissection (CADISS): a randomized trial. Lancet Neurol 14: 361-367, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahmed N, Steiner T, Caso V, et al. Recommendations from the ESO-Karolinska stroke update conference, Stockholm 13-15 November 2016. Eur Stroke J 2: 95-102, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Debette S, Compter A, Laberyrie MA, et al. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of intracranial artery dissection. Lancet Neurol 14: 640-654, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bartels E, Dissection of, the extracranial, vertebral artery. Color duplex ultrasound findings and follow-up of 20 patients. Ultraschall Med 17: 55-63, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lijuan Y, Haitao R. Extracranial vertebral artery dissection: findings and advantages of ultrasonography. Medicine 97: e0067, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baker AR, Evans DH, Prytherch DR. Some failings of pulsatility index and dampimg factor. Ultrasound Med Biol 12: 875-881, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wada S, Koga M, Makita N, et al. Detection of stenosis progression in intracranial vertebral artery dissection using carotid ultrasonography. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 28: 2201-2206, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]