Abstract

Background

The availability of clear emergency nurses’ competencies is critical for safe and effective emergency health care services. The study regarding emergency nurses’ competencies remained virtually limited.

Purpose

This study aimed to explore the emergency nurses’ competencies in the clinical emergency department (ED) context as needed by society.

Methods

This qualitative study involved focus group discussions in six groups of 54 participants from three EDs. The data were analysed using grounded theory approach including the constant comparative, interpretations, and coding procedures; initial coding, focused coding and categories.

Results

This study revealed 8 core competencies of emergency nurses: Shifting the nursing practice, Caring for acute critical patients, Communicating and coordinating, Covering disaster nursing roles, Reflecting on the ethical and legal standards, Researching competency, Teaching competencies and Leadership competencies. The interconnection of the 8 core competencies has resulted in 2 concepts of extending the ED nursing practice and demanding the advanced ED nursing role.

Conclusion

The finding reflected the community needs of nurses who work in ED settings and the need for competency development of emergency nurses.

Keywords: clinical competency, emergency care services, emergency department, emergency nursing, grounded theory, nurses, qualitative

Introduction

Globally, the need for emergency care services is predicted to remain high as seen by the crowding phenomenon in emergency departments (EDs).1,2 This has impacted the decreasing quality of both care and treatment, the increased adverse event rate and the increased mortality rate in EDs.3–5 Some low- and middle-income countries are struggling while some high-income countries have been adaptive and developed some workarounds to solve these pressing concerns.6

Indonesia relates the high demand for emergency care services to the significant incidence of severe cases and the high population size. This disease burden has illustrated the high prevalence of severe cases linked to a significant need for emergency care services. This issues is indicated in seven cases of the top 10 leading causes of death in Indonesia in 2019 that is Stroke, Ischemic heart disease, COPD, Diabetes, Cancer, Hypertensive heart disease, Road traffic injury.7,8

Additionally, Indonesia’s geographical conditions result in a high risk of experiencing natural disasters.9,10 These conditions impact the complexity of the nursing work in EDs. Concurrently, this is reflected in the need for competent emergency nurses to support safe and quality health services provided in the form of daily emergency care services and their response in disaster situations. Nurses in an emergency care context, as the “backbone” of the healthcare system, are critical in reducing mortality and morbidity within emergency populations.11

The high number of ED visits indicated 2 million ED visits or 202 per 1000 people from 118 ED in Jakarta in 2020.12 The majority of patients that attend hospital ED had general medical problems (63%), and 15.2% reported life-threatening conditions, such as trauma and cardiovascular diseases.13 The average number of ED visits was 116.37 patients per day in a top referral hospital in West Java.14 Nursing activities in the ED include triage, initial assessment, management of acute and critical patients as a team member and treating injuries that threaten a patient’s life. This is echoed in some of the global settings.15–19 A link was found between the complexity of the ED nursing practice and the competency needs of emergency nurses. Nurses working in ED are recommended to complete postgraduate studies to ensure safe practice and patient care quality.20

The additional emergency nursing training in the Indonesian education system is mostly focused on short courses, such as basic cardiac life support and basic trauma life support. The emergency nursing practice in Indonesia remained characterised by the presence of 3-year diploma nurses as part of their educational background. On average, only approximately 50% of emergency nurses are educated to professional levels or have a bachelor’s degree.18

Therefore, safe and effective emergency care services have been linked to the availability of clear nurse competency.21 Competencies are generally understood as a complex integration of knowledge, professional judgement, skills, abilities, attitudes and values, as well as special attributes that define the profession and professional skills.22–26 A lack of attention to professional competencies can raise questions and problems in nursing activities.21 The World Health Organization indicated the importance of strengthening nurses with relevant professional competency.27 Clear competency for nurses who work in ED settings is critical as it describes the required essential abilities to accomplish the nurses’ role in an emergency setting. It also provides direction for curriculum development and improves nursing education quality.24 The core competencies of emergency nurses are linked to the scope of practice standards in each country.20 Understanding emergency nurses’ competencies and how they can address the demand of society is crucial. However, standard competencies and practices for emergency nursing in the Indonesian ED context remained lacking.18,28

Globally, the health care services need of each country and the scope of practice of emergency nurses vary although references regarded the core competencies of emergency nurses. Studies related to the core competency of emergency nurses in the Indonesian context have never been conducted, until now. Therefore, this study aims to explore the core competencies of emergency nurses, which are needed by society, as described in the context of ED in Indonesia to elucidate the apparent gap in knowledge.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A qualitative method with a grounded theory (GT) analysis approach was utilised, it was chosen as it allows the researcher to use multiple data sources. The data were analysed using Charmaz and Glaser coding procedures which included open coding, focused coding and concepts or categories; and implemented constant comparative process, interpretations, theoretical sensitivity and theoretical sampling.28,29

Participants

The study was conducted from November 2017 to January 2019. Data were collected in 2018 in three EDs that are part of three general hospitals with different levels of facilities and resources located in three cities in West Java, Indonesia. The three EDs included one from a top referral hospital (class A) and two from class B hospitals. Purposive sampling was utilised, and the participants were recruited based on the following selection criteria: 1) Nurses who had been working in EDs for a minimum of 2 years; 2) Nurses who were willing to share their experiences regarding their activities and their perceived role as nurses working in the emergency care services and 3) Nurses willing to participate in a focus group discussion (FGD). The exclusion criterion was nurses who had difficulty expressing and communicating opinions. A total of 54 emergency nurses were recruited from the selected EDs, and they sufficiently contributed. This ensured the full exploration of the phenomenon under research.

Data Collection

The data collection process included the FGD procedures with emergency nurses from three ED General Hospitals and interviews with the three relevant nursing directors. Permission to undertake this research was obtained from the three directors of the respective hospitals and three nursing directors. The researcher approached the three emergency nurses’ managers and emergency nurses were invited to participate through the dissemination of information regarding this study by nurse managers at each ED and posters display.

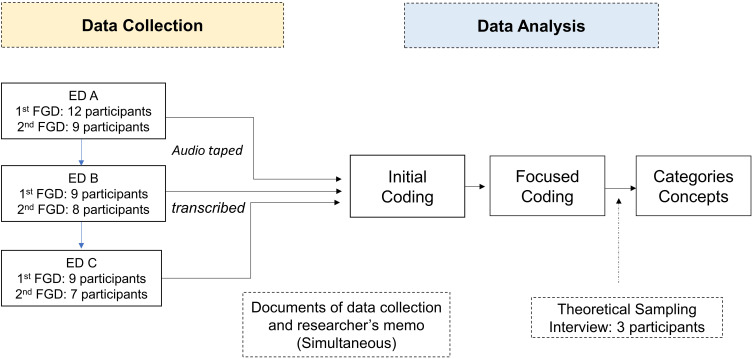

All participants provided their written informed consent before the commencement of the FGD. The first FGD was conducted in ED hospital A with 12 participants, and a moderator was the principal investigator while other research members were observers and FGD minutes. The topic in each FGD included emergency nurses’ daily practice activities, nurses’ roles and emergency nurses’ competencies. The process of the FDGs was written, audio-taped, then transcribed and then initial (open) coding commenced. The first FGD took 115 min. The second FGD involved nine participants and was undertaken in ED hospital A. The FGD process was conducted the same way as the first FGD. The research then moved to the ED at General Hospital B for the third and fourth FGDs and subsequently to the ED at General Hospital-C for the fifth and sixth FGDs, and all FGD processes were conducted the same way as in the previous FGD. The FGDs lasted on average of 100–120 min. The FGDs were conducted in a meeting room in the respective hospitals. This research simultaneously conducted data collection and analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simultaneous data collection and analysis process.

Furthermore, semi-structured interviews with three directors of nursing were conducted during the theoretical sampling phase where the researcher experienced an information gap in the analysis. The interview duration ranged from 30 to 40 min. The demographic information of the participants, such as sex, nursing education background and working experience, was collected using the demographic data sheet before the FGD process. The data generation process was determined to have been sufficient when a certain level or degree of completeness had been achieved in the obtained data.

Data Analysis

The author performed the data analysis in this study, and a verbatim process began using the FGD results. The data were analysed using the Glaser and Charmaz frameworks, including the constant comparative, interpretation and coding procedures (initial coding, focused coding and categories).28,29 The final results of this process were discussed with the whole research team.

The analysis process was initially conducted through the coding procedure as follows: the first FGD transcript was read and reread thoroughly to gain initial insight from the FGD transcription or data. The initial (open) coding commenced by the breaking down of data into analytic pieces, or a sentence that had meaning29 and naming the data segment using significant words or meaning. The coding process refers to data segment categorisation and naming to identify the relationships among the data and produce initial codes.28,30 The initial coding procedure involved the interpretation of the units of meaning, constant comparison, theoretical sensitivity and memo writing. The initial coding procedure was repeated for each of the other five FGD transcripts.

Focused coding was initiated after generating the initial codes from the sixth FGD transcripts. Focused coding refers to the more conceptual codes that were constructed through conceptually grouping the initial codes.29 This study conducted focused coding by categorising the sets of initial codes that indicate similar issues related to the nurse’s competencies in an emergency setting. Furthermore, the theoretical sampling phase was conducted once the focused codes and tentative concepts had been generated and the researcher identified any missing information. Theoretical sampling refers to the process of data generation guided by evolving concepts.30 This was achieved through interviews with the three nursing directors.

Furthermore, at the concept development stage to produced categories, this included a constant comparative process of the codes against of all data and implementation of theoretical sensitivity and interpretation to produce the 2 concepts or categories.

Rigour

The criteria for judging the rigour of this research were drawn from the concepts of work, relevance and modifiability and relationality and reflexivity.29,31,32 Workability in this research was maintained by implementing the GT method.28 Relevance was secured by ensuring conformity between the research question, research methodology and the theoretical perspectives that guided the conduct of this research. Modifiability was assured through the accomplishment of relevance and workability, which together ensured that the theoretical explanations produced in this study accurately depicted the phenomenon under study. Relationality was achieved through the FGD scheduling to be conducted based on participants’ preferences and sharing understandings of key issues. Reflexivity was achieved by the researcher being engaged in the process of critical self-reflection by conducting reflective memo writing throughout the research process for making the researcher’s values, beliefs and knowledge and biases transparent.

Ethical Consideration

Ethics approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee in Indonesia (No. 839/UN6C.10/PN/2017) and from the director of each general hospital and the head of the EDs where the study was conducted. Each participant was provided both verbal and written research descriptions. All participants signed the informed consent form before the FGD process commencement. The authors confirmed that all participant’s informed consent has included publication of anonymized responses.

Results

The majority of study participants had an educational level of three years diploma in nursing followed by a professional degree (Bachelor of Science in Nursing). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants Characteristics

| Participants Characteristics | Frequency (n) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 25 |

| Female | 29 |

| Working Experience | |

| 1–5 years | 15 |

| 5–10 years | 16 |

| > 10 years | 23 |

| Nursing Educational Background | |

| Diploma 3 in Nursing | 4 |

| Bachelor of Science in Nursing / Ners | 46 |

| Master of Nursing | 4 |

| Additional training | |

| Basic life-support | 54 |

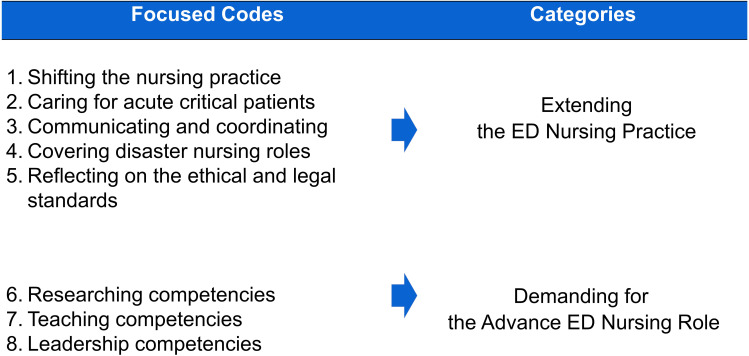

The analysis processes produced eight focused codes that reflected critical issues in emergency nurses’ core competencies in this research context, as indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The concept development process.

Furthermore, the eight focus codes were raised to eight tentative categories in the concept development process. In this case, the interrelationships of the 8-focus code have resulted in two categories (or concepts): extending ED nursing practice and demanding advanced ED nursing roles, as indicated in Figure 2.

Extending ED Nursing Practice

The concept of extending the ED nursing practice explains the condition of widening the ED nursing practice to a more complex level of practice. This issue has pointed to the domain of emergency nurses’ core competencies as indicated by emergency nurses. ED nursing competencies have been understood as required professional knowledge and skills, values and norms to conduct proper nursing practice in an ED context. The five-core competencies domains of emergency nurses’ that are illustrated below will be subsequently discussed.

Shifting the Nursing Practice

We engaged in activities such as patient condition monitoring, CPR (Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation), wound care, suturing procedure, patient transport and other activities related to forensic nursing. (Participant/P1)

Advanced life support, oxygenation and ventilation management and primary and secondary survey (EWS/early warning score) and Triage. (P1)

Triage procedure is one of the emergency nurses’ roles to promptly assess patient condition, and nurses must determine the severity level of patient’ condition within 5 minutes and understand the patient’s cases and condition. (P9)

‘Most of the nurses are unaware of the following roles: collecting forensic data, documenting patient’s data and documenting all the patient’s items on the form.’ (P22)

The knowledge and skills related to professional ED nursing practice are critical. However, our professional knowledge and skills still need to be improved. (P7)

Shifting the nursing practice to a more complex level indicated that the nursing practice in ED settings is often transferred to a more complex level of practice. The FGD indicated that the professional practice domain of emergency nurses has extended to a more complex level of practice (as indicated by the first participant [P1]). Furthermore, competencies, such as the triage procedure, are considered important to be mastered by emergency nurses (P9).

In this case, even in the daily practice of emergency nurses it often shifted to a more specialty practice level. However, their uncertainty of the legality of the triage procedure remained unclear. Moreover, the forensic nursing role was indicated as one area of professional practice where emergency nurses are often involved, and more than half of the emergency nurses explained that they often engage in such activity (P22).

The emergency nurses’ role in forensic nursing is indicated when the nurses evaluate the patient condition. This extends to documenting evidence related to criminal issues and other cases. This is following the existing judicial scope.33 This study revealed that nearly all participants expressed their need to improve their knowledge and skills (P7). Additionally, most of the emergency nurses still felt the importance of improving their knowledge and skills related to emergency nursing practice.17

Caring for Acute Critical Patients

We often engaged in the management of patients with shock and septic shock; heart diseases, stroke and diabetes; trauma and traffic accident; respiratory problems and burns. (Participant 11)

…emergency health services are multi-disciplinary dimension and cooperating and coordinating with medical teams, other nurses and patients and their families are important to gain the best possible result… (P 5)

Caring for acute critical patients is a vital role for emergency nurses. The nurses’ role involves the initial management of acute and critically ill patients to prevent the worsening of the patient’s condition (P 11 and P 5).

This competency domain is under the conditions in Indonesia, where the 10 main causes of premature death in 2019 were related to ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, road injuries and respiratory tract infections with the potential for acute attacks, which are related to the need of emergency services.

Emergency nurses’ competency in patient management is linked to the ability to understand complex cases and high acuity to manage and perform an appropriate intervention to support patients with life-threatening conditions who attended the ED.

Communicating and Coordinating

Coordinating nursing activities, …ED health services and patient care… in a multi-disciplinary team; communicating with medical staffs regarding the condition of the critical patient; communicating with ISBAR tools; implementing culturally sensitive care …with ED teams and patients and families. (Participant 18)

…emergency health services are multi-disciplinary dimension and cooperating and coordinating with medical teams, other nurses and patients and their families are important to gain the best possible result… (P 15)

Emergency care services are characterised by multidimensional aspects and are critical for achieving the best possible clinical outcomes. Therefore, coordination and communication are indicated as the most important determinants of patient safety and quality care in providing healthcare services.15 This research revealed that nearly all participants indicated that communication and coordination are critical for provision of quality health services in the ED (P 18 and P 15).

The above-mentioned data indicated that communication and coordination with all medical staff from various disciplines, with other departments within the hospital and with the patient’s families are critical for achieving best possible clinical outcome for the patients.

Covering Disaster Nursing Roles

Understanding the role of nurses in disaster conditions… including providing health care services to the disaster victims in ED or the affected communities and recognising the needs of high-risk populations in the disaster event, are crucial. (Participant 35)

…several senior emergency nurses also serve as members of the external disaster team coordinated by the ministry of health. Additionally, most of the emergency nurses are part of the internal disaster team, where nurses provide health services to disaster victims in the ED. In an external position, emergency nurses are assigned to provide health care services at the disaster site as part of the health care team…. (P 8)

Covering disaster nursing roles explains that the emergency nurses’ core competency domain includes the nurses’ capacity to work in disaster conditions in the ED. The emergency nurses must provide an appropriate response to disaster victims who attended to ED or work in disaster locations. This situation requires nurses to work under the nurses’ role according to local resources and organisational structures in the context of disaster. The majority of emergency nurse participants agreed on the condition that emergency nurses still needed the support of knowledge and skills to work in disaster conditions. This was described in the participants’ (P 35 and P 8) quotes.

This study indicated that ED nursing roles are linked to the nurses’ role in disaster events, as indicated in the participants’ quotes above. Most emergency nurses’ in this study have experience in providing care to the affected community in a disaster location, and most of them considered that disaster nursing competencies are important for their role.

Reflecting on the Ethical and Legal Standards

…nurses in the ED, as one the frontline health professionals, must be able to conduct triage procedures. However, the job description… related to the implementation of triage procedure in ED remained unclear. (Participant 16)

Reflecting on the ethical and legal standards is one of the important issues present in the context when it comes to extending the ED nursing practice. This issue is linked to the capacity of emergency nurses when implementing legal issues and ethical principles and norms as part of their decision-making in their daily nursing practice. Emergency nurses’ reflection on ethical and legal standards is illustrated in participants’ (P16) quotes. Emergency nurses felt that the standard procedure regarding triage remained unclear. Emergency nurses recognise that ethical and legal standards are critical in guiding emergency nursing practices.

The interrelation of the five-core competencies domain, as discussed above, has indicated that the key issues of the core competencies of emergency nurses are related to the extending nursing practice in ED.

Demanding for the Advanced ED Nursing Role

This concept of demanding the advanced ED nursing role explains the relationship between the conditions of extending ED nursing practice and the need for emergency nurses’ competency at an advanced level, as indicated in the issues of research, teaching and learning and leadership competency. The advanced nursing role is a more general term for nurses educated in professional education at the postgraduate level. The participants stated the limitations in knowledge and skills to support the nurses’ role related to the included core competencies in the advanced nursing role as indicated below.

Researching Competency

…in this ED, research is usually conducted mainly by postgraduate nursing students, by lecturers in this area, or by emergency nurses at the top referral hospital. This is because a limited number of nursing resources remains… (Participant 35)

Researching competencies are related to the capacity of the nurses in conducting, interpreting and transferring research findings to improve the quality of emergency care services. The FGD revealed that most emergency nurses perceived that their research competencies remained limited as described in participants’ (P 35) quotes.

Research competencies17 are important for improving the quality of emergency healthcare services to achieve the best possible clinical outcomes for patients in the ED. This competency is not only critical for emergency nurses but also for nursing as a profession because this research competency is linked to the development of emergency nursing knowledge and the ownership of knowledge for the profession.

Teaching Competencies

…activities in teaching-learning included activities… coordinating, mentoring and preceptorship for nursing student practicing in the ED… and … as a trainer in an emergency nursing team…. (Participant 19)

Teaching competency refers to the knowledge and skills needed to support the role of emergency nurses in clinical education in connection to patients and their families, as well as in professional development related to the learning process with student nurses and other nurses in the emergency nursing area.23 This teaching competency was described in the participant’s (P 19) quotes.

Nurses must have a minimum formal education at the bachelor (Ners) level in addition to the 3 years of experience working in an ED setting for clinical emergency nurses to be involved in the clinical teaching process in the provision of emergency care services.

This competency is essential to produce quality ED care services for society. The teaching and learning competencies are critical for developing emergency nursing education and are also important to support the advanced nursing role in emergency nursing.

Leadership Competencies

…the leadership capacity should be owned by the head nurse, or a team leader and CCM (Clinical Care Manager), and a supervisor. Leadership capacity at the individual level must be possessed by all professional nurses who work in ED settings… (Participants 17)

Undertaking rational choices for best results of nursing practices; honest, responsible attitude; control emotions, able to identify self-learning needs and transferring knowledge into practice; responding appropriately in crisis and critical situations. (P 39)

Leadership competencies include the knowledge, skills and values that contribute to the improvement of nursing practice performance. This study revealed leadership competencies both at the individual nurse and group levels, such as the roles of nurses as team leaders, clinical care managers (CCM), supervisors and head nurses in the ED, as described in the participants’ (P 17 and P 39) quotes.

At the group level, leadership is related to the knowledge and skills in a larger area that can empower other nurses, including helping others develop into better nurses.34,35 All nurses in this research, who were in the position of team leader, CCM or nurse supervisor (nurse manager), had an educational background that was at least at the BSN level.

Leadership is concerned with the awareness of understanding and learning regarding both knowledge and skills for personal and professional development at both individual and group levels. All emergency nurses agreed that leadership competencies are important to support their activities.

Discussion

This study focused on an exploration of emergency nursing competencies in the clinical ED context in Indonesia. This research revealed eight core competencies that are needed by emergency nurses in the clinical ED context in Indonesia. Additionally, the interconnection of these eight core competencies has constructed two concepts of extending ED nursing practice and demanding advanced ED nursing roles.

The first concept, extending the ED nursing practice, indicated the five emergency nurses’ competency domains that are linked to skills and knowledge to support nursing practice in ED. These competencies are directly related to the characteristics of emergency care services. Mastery of these five competencies is important to inform safe and quality practice in the provision of emergency care services.

This study result is congruent with the study findings by Jones et al employed comparative analysis of competency standards identified from CENA (College of Emergency Nursing Australasia); NENA (National Emergency Nurses Association) in Canada; CENNZ (the College of Emergency Nurses New Zealand), FEN (the Faculty of Emergency Nursing) in the United Kingdom and ENA (Emergency Nurses Association) in the United States which suggested that emergency nurses’ competency standards consist of five domains of clinical expertise, communication, teamwork, resources and environment and legality.19

The second concept, demanding the advanced ED nursing role, indicated that an emergency nursing role in specialty or advanced nursing has become a need of society today, to support quality emergency care services. The involvement of nurses in advanced practice in emergency and critical care improves the length of stay, time to treatment, mortality, patient satisfaction, and cost savings.36 CNS core competencies including direct care; consultation; leadership; collaboration; coaching, research; ethical decision making.37 This research context has demonstrated the need for advanced ED nursing roles, especially in research, leadership and teaching competencies, which have become a need to support quality emergency nursing practice.

The advanced ED nursing role is characterised by working with both evidence-based and research-based practices when managing complex cases38 and when acting as both an expert nurse and a change agent. This study indicated that the majority of emergency nurses perceived their limitations in leadership, teaching competencies and conducting research. Furthermore, the study finding regarding the research competency, where emergency nurses still perceived inadequacies, was similar to the study of Vand Tamadoni, Shahbazi, Seyedrasooli, Gilani and Gholizadeh, which showed lacking competencies of critical thinking/research and teaching-training.39

This study still indicated the gaps between the competencies required for emergency nurses and the existing conditions where nearly half of the emergency nurses still hold a 3-year diploma in nursing in 2018. This study provides evidence that ED nursing practice needs to be supported by nursing resources that have at least a bachelor’s education as the basis for developing nursing competency at the specialty/advanced level. Emergency nursing, as a specialty practice, is depicted through the nurses’ body of knowledge and skills and the scope of the practice of emergency nurses at the clinical level that is linked to the characteristics of emergency care services roles.40 Furthermore, the concept of extending the ED nursing practice pointed to the importance of the existence of the emergency nurses’ role at the advanced level which is linked to the nurses’ competencies or knowledge and skills at the specialty level. This competency at the specialty level is critical to support quality and safe emergency nursing care services. Further, it is important for developing emergency nursing knowledge and skills.

In the Indonesian context, the specialist’s competency is indicated in Regulation Number 3 regarding the National Higher Education Standards41 which refers to competencies in performing complex types of work in their area of expertise that requires educational preparation at the specialist level. These specialist competencies are at least equivalent to national or international professional competency standards and are focused on clinical expertise.

In Indonesia, formal educational preparation in emergency nursing at the postgraduate level or as a master’s degree in nursing is available, although it is limited in terms of access. However, formal educational preparation for specialist nursing roles for emergency nurses is not yet available nor is advanced nursing registration. These conditions have resulted in the presence of issues related to unclear emergency nurse competency standards, a concern regarding ethical and legal issues and the lack of capacity in terms of research, leadership and nurses’ role as an educator.

This study revealed that educational preparation that combines both the Master of Nursing Education and specialist levels in the Indonesian context is crucial for producing emergency nurses with competency following the needs of society, as well as its conformity with international standards. ANA indicated that a nurse specialist in an emergency care setting involves clinical practice, education, research and consultation.42 The implementation of advanced or specialist nursing roles has resulted in the benefit of providing continuously improved results in terms of patient care and the entire health service system.43 The development of specialist nursing roles has internationally gained recognition and provided greater recognition of the nursing profession worldwide.44

The study results indicated that the interconnection between the two concepts of extending the ED nursing practice and demanding the advanced ED nursing role has suggested a community need for emergency nurses as depicted in the eight domains of emergency nurses’ competencies.

Conclusion

New insights generated from this study have provided evidence regarding the eight core competencies needed to support the role of nurses in the ED and have provided an understanding that the interconnection of the eight core competencies means extending the ED nursing practice and demanding the advanced ED nursing role.

These two concepts and the eight core competencies of emergency nurses provide direction for the need to develop the competence of emergency nurses and indicate the community’s need for nurses working in the ED. These eight core competencies are crucial to anticipate the complexity of emergency health services both now and in the future. The study results indicated that the emergency nurses’ competencies at the specialist level have become a demand in today’s society. Therefore, the support from the government is needed for the development of advanced emergency nursing practice through the establishment of professional nursing education.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all nurse participants and ED head nurses for their time and participation in this study.

Funding Statement

This study has received funding from the Minister of Research and Technology and Higher Education, Indonesia.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for each individual was performed by the researcher manually.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee in Indonesia (No. 839/UN6C.10/PN/2017). Approval was also obtained from the director of each general hospital and the head of the EDs where the study was conducted. This research was considered to be low risk as the participants in this research were competent and capable healthcare professionals. Each participant was provided with both a verbal and a written description of the research. All of the participants signed the informed consent form prior to the commencement of the FGD process.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the work reported, whether in the conception, study design, execution, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; contributed in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; provided final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- 1.Boyle A, Coleman J, Sultan Y, et al. Initial validation of the International Crowding Measure in Emergency Departments (ICMED) to measure emergency department crowding. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(2):105–108. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(2):126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.George F, Evridiki K. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient outcomes. Health Sci J. 2015;9:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun BC, Hsia RY, Weiss RE, et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):605–611.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson KD, Winkelman C. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient outcomes: a literature review. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2011;33(1):39–54. doi: 10.1097/TME.0b013e318207e86a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(11):e1196–e1252. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. World Health Organisation; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death. Accessed December 22, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.USAID. Indonesia: disaster response and risk reduction. Available from: https://www.usaid.gov/indonesia/fact-sheets/disaster-response-and-risk-reduction-oct-24-2014. Accessed December 21, 2021.

- 9.Emaliyawati E, Ibrahim K, Trisyani Y, Mirwanti R, Ilhami FM, Arifin H. Determinants of nurse preparedness in disaster management: a cross-sectional study among the community health nurses in coastal areas. Open Access Emerg Med. 2021;13:373–379. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S323168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yusvirazi L, Sulistio S, Wijaya Ramlan AA, Camargo Jr CAJ. Snapshot of emergency departments in Jakarta, Indonesia. Emerg Med Australas. 2020;32(5):830–839. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brysiewicz P, Scott T, Acheampong E, Muya I. Facilitating the development of emergency nursing in Africa: operational challenges and successes. Afr J Emerg Med. 2021;11(3):335–338. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2021.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brice SN, Boutilier JJ, Gartner D, et al. Emergency services utilization in Jakarta (Indonesia): a cross-sectional study of patients attending hospital emergency departments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):639. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08061-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yudiah W, Yudianto K, Prawesti A. Fatigue and work satisfaction of emergency nurses in Bandung, West Java, Indonesia. Belitung Nurs J. 2018;4(6):602–611. doi: 10.33546/bnj.558 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammad KS, Arbon P, Gebbie K, Hutton A. Nursing in the emergency department (ED) during a disaster: a review of the current literature. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2012;15(4):235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nugus P, Forero R. Understanding interdepartmental and organizational work in the emergency department: an ethnographic approach. Int Emerg Nurs. 2011;19(2):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ranse J, Shaban RZ, Considine J, et al. Disaster content in Australian tertiary postgraduate emergency nursing courses: a survey. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2013;16(2):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trisyani Y, Windsor C. Expanding knowledge and roles for authority and practice boundaries of emergency department nurses: a grounded theory study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2019;14(1):1563429. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2018.1563429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Usher K, Redman-MacLaren ML, Mills J, et al. Strengthening and preparing: enhancing nursing research for disaster management. Nurse Educ Pract. 2015;15(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones T, Shaban RZ, Creedy DK. Practice standards for emergency nursing: an international review. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2015;18(4):190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karami A, Farokhzadian J, Foroughameri G, Hills RK. Nurses’ professional competency and organizational commitment: is it important for human resource management? PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Nurses Association. Embarking on the Journey: Competency Model. American Nurses Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheetham G, Chivers GE. Professions, Competence and Informal Learning. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukada M. Nursing competency: definition, structure and development. Yonago Acta Med. 2018;61(1):1–7. doi: 10.33160/yam.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalb KA. Core competencies of nurse educators: inspiring excellence in nurse educator practice. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2008;29(4):217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poindexter K. Novice nurse educator entry-level competency to teach: a national study. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52(10):559–566. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20130913-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Global Strategic Directions for Strengthening Nursing and Midwifery 2016–2020. World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suba S, Scruth EA, New A. Era of nursing in Indonesia and a vision for developing the role of the clinical nurse specialist. Clin Nurse Spec. 2015;29(5):255–257. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glaser B. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research (3rd Ed.): Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall WA, Callery P. Enhancing the rigor of grounded theory: incorporating reflexivity and relationality. Qual Health Res. 2001;11(2):257–272. doi: 10.1177/104973201129119082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mills J, Bonner A, Francis K. Adopting a constructivist approach to grounded theory: implications for research design. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12(1):8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00543.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammond B, Zimmermann P. Sheehy’s Manual of Emergency Care. 7th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, Saul JE, Carroll S, Bitz J. Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Q. 2012;90(3):421–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00670.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Day DV, Fleenor JW, Atwater LE, Sturm RE, McKee RA. Advances in leader and leadership development: a review of 25years of research and theory. Leadersh Q. 2014;25(1):63–82. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woo BFY, Lee JXY, Tam WWS. The impact of the advanced practice nursing role on quality of care, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and cost in the emergency and critical care settings: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0237-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists. Clinical nurse specialist core competencies: executive summary 2006–2008. NCCT Force; 2010:1–26.

- 38.Peplau H. Specialization in professional nursing. Clin Nurse Spec. 2003;17(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200301000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vand Tamadoni B, Shahbazi S, Seyedrasooli A, Gilani N, Gholizadeh L. A survey of clinical competence of new nurses working in emergency department in Iran: a descriptive, cross-sectional study. Nurs Open. 2020;7(6):1896–1901. doi: 10.1002/nop2.579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fry M. Overview of emergency nursing in Australasia. Int Emerg Nurs. 2008;16(4):280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2008.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Indonesian Minister of Education and Culture. Regulation No. 3, 2020 National Higher Education Standard. Republic of Indonesia; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winger J, Brim CB, Dakin CL, et al. Advanced practice registered nurses in the emergency care setting. J Emerg Nurs. 2020;46(2):205–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2019.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryant-Lukosius D, Spichiger E, Martin J, et al. Framework for evaluating the impact of advanced practice nursing roles. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48(2):201–209. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loke AY, Fung OWM. Nurses’ competencies in disaster nursing: implications for curriculum development and public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(3):3289–3303. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110303289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]