Abstract

Severe allergic reactions following SARS-COV-2 vaccination are generally rare, but the reactions are increasingly reported. Some patients may develop prolonged urticarial reactions following SARS-COV-2 vaccination. Herein, we investigated the risk factors and immune mechanisms for patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergy and chronic urticaria (CU). We prospectively recruited and analyzed 129 patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccine–induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions as well as 115 SARS-COV-2 vaccines–tolerant individuals from multiple medical centers during 2021–2022. The clinical manifestations included acute urticaria, anaphylaxis, and delayed to chronic urticaria developed after SARS-COV-2 vaccinations. The serum levels of histamine, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17 A, TARC, and PARC were significantly elevated in allergic patients comparing to tolerant subjects (P-values = 4.5 × 10−5–0.039). Ex vivo basophil revealed that basophils from allergic patients could be significantly activated by SARS-COV-2 vaccine excipients (polyethylene glycol 2000 and polysorbate 80) or spike protein (P-values from 3.5 × 10−4 to 0.043). Further BAT study stimulated by patients’ autoserum showed positive in 81.3% of patients with CU induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccination (P = 4.2 × 10−13), and the reactions could be attenuated by anti-IgE antibody. Autoantibodies screening also identified the significantly increased of IgE-anti–IL-24, IgG-anti–FcεRI, IgG-anti–thyroid peroxidase (TPO), and IgG-anti-thyroid–related proteins in SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients comparing to SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls (P-values = 4.6 × 10−10–0.048). Some patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced recalcitrant CU patients could be successfully treated with anti-IgE therapy. In conclusion, our results revealed that multiple vaccine components, inflammatory cytokines, and autoreactive IgG/IgE antibodies contribute to SARS-COV-2 vaccine–induced immediate allergic and autoimmune urticarial reactions.

Keywords: Anti-TPO IgG, Autoreactive antibodies, Chronic urticaria, SARS-COV-2 vaccine, PEG

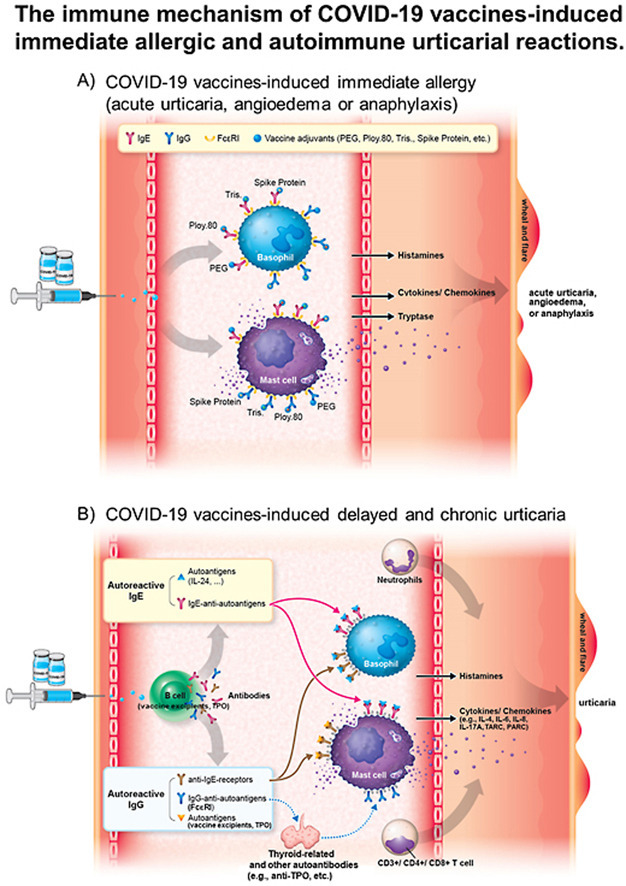

Graphical abstract

The immune mechanism of COVID-19 vaccines-induced immediate allergy and urticaria. A). The excipient or component of COVID-19 vaccines (such as PEG 2000, poly 80, tris, or spike protein) can be directly recognized by IgE antibodies, which coupled with their receptor-FcεRI on the mast cells or basophils, resulting in mast cell/basophil degranulation and triggering immediate allergic reactions. B). The excipient or component of COVID-19 vaccines can be recognized by B cells or presented to the T cells, resulting in autoreactive IgG/IgE antibodies production and increased cytokine/chemokine release. Moreover, IgG/IgE autoantibodies against self-antigens (e.g., IL24, TPO, etc.), may promote mast cell or basophil degranulation and cause delayed and chronic urticarial reactions. Abbreviation: IgE, immunoglobulin E; IL-24, Interleukin-24, PEG, polyethylene glycol; poly 80, polysorbate 80; TPO, thyroid peroxidase antibody, tris, tromethamine.

Abbreviations

- 95% CI

95% confidence intervals

- Anti-TPO IgG Ab

Anti-Thyroid Peroxidase Immunoglobulin G Antibody

- Anti-THRA

anti-thyroid hormone receptor alpha

- Anti-TYMS

anti-thymidylate synthetase

- CCL17

C–C Motif Chemokine Ligand 17

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CSU

chronic spontaneous urticaria

- CU

chronic urticaria

- CXCL9

CXC motif chemokine ligand 9

- ENDA

European Network for Drug Allergy

- EAACI

European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HD

healthy donors

- IRB

institutional review board

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- IFN-γ

interferon-gamma

- LAT

lymphocyte activation test

- MIG

monokine induced by gamma interferon

- MIP-1β

macrophage inflammatory protein-1β

- PARC

pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- Poly 80

polysorbate 80

- OR

odds ratio

- RBD

receptor-binding domain

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SEM

standard error of mean

- SD

standard deviation

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SPT

skin prick test

- Tris

tromethamine

- TARC

thymus and activation-regulated chemokine

- UAS7

urticaria activity score over 7 days

1. Introduction

The new coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic resulted in an unprecedented fast development of vaccines for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Many SARS-COV-2 vaccines make use of novel vaccine platforms and were firstly to be used in such large numbers. The mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) [1] and Moderna (mRNA-1273) [2] contain mRNA encoding the spike protein trimer receptor-binding domain (RBD) subunit of the SARS-CoV-2 virus [3]. The vaccine developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca (AZD1222) [4] makes use of a recombinant adenovirus with DNA encoding the spike protein. Furthermore, several protein subunit or inactivated vaccines are available, including the Medigen/Novavax (MVC-COV1901) [5] and Sinovac (CoronaVac) [6], respectively. A number of studies have confirmed the ability of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to provide robust protection against SARS-CoV-2 by generating neutralizing antibodies or memory B cells [[7], [8], [9]].

Allergic and hypersensitivity reactions to SARS-COV-2 vaccines have been reported [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]], with several excipients in the vaccine formulations being the potential cause of these allergic or hypersensitivity reactions. Severe allergic responses to vaccines are generally rare, with approximately <2% of individuals after receiving SARS-COV-2 mRNA vaccine [[14], [15], [16], [17],19,20]. However, the incidence of severe immediate allergic reactions to SARS-COV-2 vaccines was higher than that of other vaccines [15,17,19,20]. In addition to local reactions (COVID-19 arm), urticaria and/or angioedema is one of the most common cutaneous reactions induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines [10,11]. Both mRNA vaccines (such as BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273) contain polyethylene glycol (PEG) 2000. The use of PEG in vaccines is used to protect the nanoparticles from degradation. Furthermore, the mRNA-1273 vaccine contains tromethamine, and the AZD1222 vaccine contains polysorbate 80, which all may be regarded as the causing components of allergic and hypersensitivity reactions [12,16,18]. Furthermore, mild allergic and cutaneous reactions to these vaccines are not considered a contraindication to revaccination [14,[21], [22], [23]], and risk factors for immediate anaphylactic shock to SARS-COV-2 vaccines include previous immediate allergic reactions to insect bites, food, drug [17], vaccine or one of the vaccine excipients in other formulations that are either injected or taken orally [18].

A growing number of patients are reported to develop immediate allergic and urticarial reactions after SARS-COV-2 vaccination with variable prolonged and chronic courses. However, the pathomechanism behind the development of the symptoms remain largely unclear. Mast cells are considered the critical immune cells responsible for immediate allergic and urticarial reactions, as they release histamine and inflammatory cytokines to induce various immune responses [24]. For the immune mechanism of autoimmune chronic urticaria (CU), it has been reported that mast cell degranulation can be triggered by IgE, IgG anti-IgE, or IgG anti-FcεRI (an IgE receptor) [25,26]. Most of autoimmune CU patients is correlated with IgE antibodies against autoantigens (such as thyroid peroxidase [TPO], IL-24, etc.) while <10% of autoimmune CU patients is mediated by IgG, IgM, or IgA autoantibodies that induce mast cells degranulation [25,26]. Furthermore, the low sensitivity of ex vivo testing (such as skin prick test [SPT], intradermal skin test or basophil activation test [BAT]) for patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic reactions have been reported previously [[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]], suggesting that the immune mechanisms underlying the allergic and urticarial reactions induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines are complicated. To date, no early diagnosis markers and useful methods have been identified for patients developed prolonged urticaria after SARS-COV-2 vaccination.

In this study, we investigated the risk factors and immune mechanisms for patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions. We further provide effective therapeutic strategy for patients with recalcitrant CU induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines, and assessed the recurrent rate for patients experienced immediate allergic reactions and prolonged urticaria induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines for sequential vaccination.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients enrollment

A total of 129 patients with immediate allergic and urticarial reactions induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines, including anaphylaxis, angioedema, urticaria, urticarial dermatitis, and chronic urticaria (CU; symptoms>6 weeks; resistant to antihistamine) were enrolled from the Taiwan Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reaction consortium (multiple medical centers including Linkou, Taipei, Keelung, Taoyuan, and Tucheng Chang Gung Memorial Hospitals, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, and National Cheng Kung University Hospital) in Taiwan during 2021–2022. The clinical course, dosage, SARS-COV-2 vaccine duration, drug/vaccine allergy history, systemic involvement, and mortality were also recorded. The Naranjo algorithm was used to assess the causal vaccine for adverse reaction [35]. Clinical features of immediate allergy and anaphylaxis were classified according to previous classification [36,37]. We also utilized Brighton Collaboration criteria for definitions of the allergic reactions following vaccinations [38,39]. All patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions were assessed by at least two dermatologists. In addition, 115 subjects who had at least received second dose of SARS-COV-2 vaccines for more than 8 weeks without evidence of any cutaneous reactions were enrolled as tolerant controls.

All enrolled patients provided written consent to protocols that were approved by Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of each hospital based on Taiwan's law and regulations (IRB No. 202000512A3, 202101436B0, 202101404B0A3, and 202102216A3). Informed consent was obtained from all patients and tolerant subjects.

2.2. BAT tested for patients’ autoserum

The protocol was used as described by Curto-Barredo et al. [40]. Health tolerant subject's blood (50 μl) was obtained in an EDTA tube and mixed with 20 ng/mL IL-3, and 50 μl of serum from patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccine-induced chronic urticaria (CU), tolerant subjects, patients with non-vaccine induced chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), or anti-FceRI monoclonal antibody (positive control). Fresh blood samples were obtained from the same healthy donor for all tests. Samples were washed and basophil activation was assessed through measurement of CD63 expression, as described under BAT methods. For the ex vivo anti-IgE inhibitor assay, patients' serum samples were pretreated with the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab at a dose reflecting a 1-fold physiological therapeutic level (3.75 μg/mL) for 40 min, after which samples were incubated for 40 min at 37 °C with healthy donor EDTA blood. Samples were washed and basophil activation was assessed through measurement of CD63 expression, as described under BAT methods in the Methods section of the Supplementary information.

2.3. IgE anti-IL-24 autoantigen measurements

The presence of IgE antibodies directed at IL-24 were assessed using ELISA. Briefly, 250 ng of human IL-24 protein (1965-IL-025/CF, R&D Systems; Minneapolis, USA) was added in 50 μL of coating buffer (0.1 mol/L carbonate [pH 9]; Sigma) per well in an ELISA plate (ThermoFisher, Massachusetts, USA) to coat at 4 °C overnight. After blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in tris-buffered saline with 0.5% Tween 20 detergent (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature, patients' sera were added and incubated at 4 °C overnight, followed by three washes with TBST. Thereafter, the IgE expression was measured using an anti-human IgE Fc antibody (ab99806, Abcam), based on the manufacturer's protocol. Sera from SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial patients were measured duration the active stage of cutaneous reactions period, while the those from tolerant subjects were obtained for more than 8-week after vaccination.

Additional information regarding methods to basophil activation test (BAT), cytokine/chemokine evaluation, interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-based lymphocyte activation test (LAT), anti-PEG, anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein IgG/IgE, anti–FcεRIα IgG, protein array analysis for IgG antibodies against autoantigens, B cell culture, and urticaria activity score over 7 days (UAS7) evaluation are provided in the Methods section in the Supplementary information.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The Fisher's exact test was used to assess differences between groups in clinical characteristics. Fisher's exact test, and odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by using RStudio-1.2.1335 (Northern Ave, Boston, MA). The sex-matched analysis was further performed to investigate the trends and associations among various risk factors or laboratory data, including gender, anti-TPO IgG, total IgE, d-dimer, ORs, etc. Age, cytokine/chemokine evaluation, BAT, LAT/B cell culture results, and IgG/IgE antibody levels were analyzed by comparing between two variables using the two-tailed Student's t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics

We enrolled a total of 129 patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergy and urticaria as well as 115 SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant subjects (Table 1 ). Representative images of different SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced angioedema, urticaria, urticarial dermatitis, and chronic urticaria are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, available online with this article. The mean age of the allergic group was 47.4 ± 18.2 and that of the tolerant control group was 47.5 ± 15.1 years. Out of the 129 patients with allergic reactions after SARS-COV-2 vaccinations, 42 (32.6%) had immediate allergic reactions within 24 h of the vaccinations. Delayed urticaria after 24 h were experienced by 87 patients (67.4%). Among patients with immediate allergic reactions, there was 41 patients (31.8%) with acute urticaria, nine patients with angioedema (7.0%), two patients with bronchospasm, and five patients with acute urticaria accompanied by anaphylaxis (3.9%) in response to the SARS-COV-2 vaccines. For most allergic patients, the mRNA-1273 vaccine (48.1%) was the culprit of the allergic reactions, followed by the AZD1222 vaccine for 34.1% of patients, BNT162b2 in 14.0% of cases, MVC-COV1901 in 2.3% of cases, and CoronaVac in 1.6% of cases. The onset of the allergic reactions was at the first dose for most patients (62.0%), while 21.7% of patients experienced this response upon the second dose, and 16.3% upon the third dose. The majority in the allergic group was female (69.8%, P = 0.024) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions as well as SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls.

| Characteristics | SARS-COV-2 vaccines- induced immediate allergy and urticaria n = 129 | SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls n = 115 |

OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 47.4 ± 18.2 | 47.5 ± 15.1 | – | 0.926a |

| Phenotypes, n (%) | – | |||

| Immediate allergic reactions (within 24 h) | 42 (32.6%) | |||

| Acute urticaria | 41 (31.8%) | – | – | |

| Angioedema | 9 (7.0%) | – | – | |

| Bronchospasm | 2 (1.6%) | – | – | |

| Anaphylaxis | 5 (3.9%) | – | – | |

| Delayed urticarial reactions (after 24 h) | 87 (67.4%) | – | – | |

| Culprit/Received SARS-COV-2 vaccine, n (%) | – | |||

| AZD1222 | 44 (34.1%) | 27 (23.5%) | – | |

| mRNA-1273 | 62 (48.1%) | 40 (34.8%) | – | |

| BNT162b2 | 18 (14.0%) | 19 (16.5%) | – | |

| MVC-COV1901 | 3 (2.3%) | 3 (2.6%) | – | |

| CoronaVac | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| AZD1222 + mRNA-1273 | – | 17 (14.8%) | – | |

| AZD1222 + BNT162b2 | – | 5 (4.3%) | – | |

| MVC-COV1901 + mRNA-1273 | – | 3 (2.6%) | – | |

| Inducing dosage of SARS-COV-2 vaccination, n (%) | – | |||

| 1st dose | 80 (62.0%) | 0 (0%) | – | |

| 2nd dose | 28 (21.7%) | 67 (58.3%) | – | |

| 3rd dose | 21 (16.3%) | 48 (41.7%) | – | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 90 (69.8%) | 64 (55.7%) | 1.8 (1.1–3.1) | 0.024 |

| Allergy history and underlying disorders, n (%) | ||||

| Drug hypersensitivity | 6 (4.7%) | 4 (3.5%) | 1.4 (0.4–4.9) | 0.753 |

| Food allergy | 5 (3.9%) | 11 (9.6%) | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) | 0.118 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 8 (6.2%) | 11 (9.6%) | 0.6 (0.2–1.6) | 0.349 |

| Asthma | 4 (3.1%) | 2 (1.7%) | 1.8 (0.3–10.1) | 0.687 |

| Eczema or atopic dermatitis | 4 (3.1%) | 8 (7.0%) | 0.4 (0.1–1.5) | 0.236 |

| SLE | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.9 (0.1–14.4) | 1.000 |

| CUb | 7 (5.4%) | 4 (3.5%) | 1.6 (0.5–5.6) | 0.547 |

| Thyroid disease | 6 (4.7%) | 1 (0.9%) | 5.6 (0.7–46.9) | 0.124 |

| Laboratory data, positive n (%) | ||||

| Anti-TPO Ab | 23 (17.8%) | 5 (4.3%) | 4.8 (1.8–13.0) | 0.001 |

| ANA | 9 (7.0%) | 4 (3.5%) | 2.1 (0.6–7.0) | 0.264 |

| TSH | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.9 (0.1–6.4) | 1.000 |

| CRP | 13 (10.1%) | 7 (6.1%) | 1.7 (0.7–4.5) | 0.351 |

| Increased total IgE | 36 (27.9%) | 12 (10.4%) | 3.3 (1.6–6.8) | 6.5 × 10−4 |

| D-dimer | 32 (24.8%) | 6 (5.2%) | 6.0 (2.4–15.0) | 1.6 × 10−5 |

| Leukocytosis | 11 (8.5%) | 7 (6.1%) | 1.4 (0.5–3.8) | 0.625 |

| Eosinophilia | 14 (10.9%) | 7 (6.1%) | 1.9 (0.7–4.8) | 0.253 |

| Basophilia | 6 (4.7%) | 4 (3.5%) | 1.4 (0.4–4.9) | 0.753 |

Thyroid disease contains hyperthyroidism, Graves' disease, and thyroid cancer.

The normal ranges of the laboratory data were described as: anti-TPO Ab <5.6 IU/mL; ANA negative (<1:40); TSH: 0.27–4.2 μIU/mL; total IgE: adult<100 KU/L; D-Dimer <0.55; Cut-off<0.5; probability of exclusion of PE/DVT is 95% mg/L FEU; CRP <5 mg/L; leukocytosis: WBC male >10.6 and female >11 1000/μL; eosinophilia: >500/μL; basophilia >1%.

Abbreviation: ANA, antinuclear IgG antibody; Anti-TPO Ab, anti-thyroid peroxidase IgG antibody; CRP, C-reactive protein; CU, chronic urticaria; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

*P values were calculated by Fisher's exact test and obtained from comparison of SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial patients with relevant SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls.

This P values were calculated by Student's t-test.

The CU history was occurred before vaccination and there was no any symptom for 6 months before vaccination.

Among our enrolled patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions, patients had a history of drug hypersensitivity in 4.7%, food allergy in 3.9%, allergic rhinitis in 6.2%, asthma in 3.1%, eczema or atopic dermatitis in 3.1%, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in 0.8%, previous chronic urticaria (CU) history in 5.4%, and thyroid disease in 4.7% of cases. There is no statistical different of allergy history and underlying disorders in SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced allergic patients comparing to tolerant subjects (Table 1).

We then compared laboratory data between the allergic and tolerant groups. The levels of anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) IgG antibodies (odd ratio [OR] = 4.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.8–13.0, P = 0.001), total IgE (OR = 3.3, 95% CI = 1.6–6.8, P = 6.5 × 10−4), and D-dimer (OR = 6.0, 95% CI = 2.4–15.0, P = 1.6 × 10−5) were found to be significantly higher in patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced allergic reactions than in tolerant subjects (Table 1). Furthermore, the levels of anti-TPO IgG, total IgE, and D-dimer were still significant in SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced allergic patients compared with sex-matched tolerant subjects (Supplementary Table 1).

3.2. Identification of culprit compounds of SARS-cov-2 vaccines by ex vivo basophil activation test (BAT)

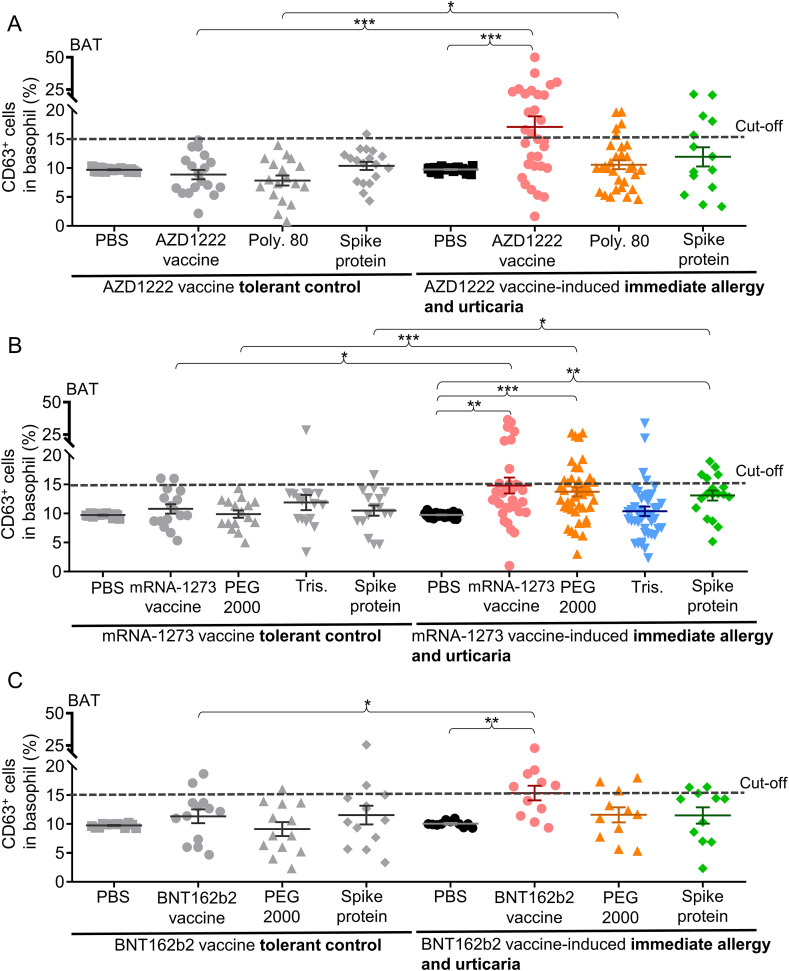

The ex vivo BAT was firstly used to identify the culprit compounds in various SARS-COV-2 vaccines causing immediate allergic and urticarial reactions in our cohort of patients (Fig. 1 ). Basophils from AZD1222 vaccine-induced reactivity patients were significantly activated against the AZD1222 vaccine itself (activated CD63+basophils: 17.1 ± 1.8%, P = 1.9 × 10−4) and polysorbate 80 (CD63+basophils: 10.6 ± 0.8%, P = 0.022; sensitivity = 16.1%) compared to tolerant subjects (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

The results of ex vivo BAT for patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions.

A, the percentage of activated CD63+ basophils after treatment with AZD1222 (AstraZeneca) vaccine, poly 80, spike protein, or solvent control (PBS) for 31 patients with AZD1222 vaccine-induced allergy and 18 AZD1222 vaccine-tolerant controls. B, the percentage of activated CD63+ basophils after treatment with mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccine, PEG 2000, Tris, spike protein, or solvent control for 43 patients with mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced allergy and 16 mRNA-1273 vaccine-tolerant controls. C, the percentage of activated CD63+ basophils after treatment with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) vaccine, PEG 2000, spike protein, or solvent control for 11 patients with BNT162b2 vaccine-induced allergy and 12 BNT162b2 vaccine-tolerant controls. Dotted lines represent the cut-off point (>5%) for all BAT data. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0 0.01, and ***P < 0 0.001 calculated by 2-tailed Student's t-test.

Abbreviation: BAT, basophil activation test; SARS-COV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; PEG 2000, polyethylene glycol 2000; poly 80, polysorbate 80; Tris, tromethamine; SEM, standard error of mean.

Allergic patients induced by the mRNA-1273 vaccine had significantly more basophil activation than tolerant controls in response to the mRNA-1273 vaccine (CD63+ basophils: 14.8 ± 1.4%, P = 0.015), PEG 2000 (CD63+basophils: 13.8 ± 0.8%, P = 3.5 × 10−4; sensitivity = 30.2%, 13 positive results in 43 patients), and the spike protein (CD63+basophils: 13.1 ± 0.9%, P = 0.043) (Fig. 1B). Four patients also had basophil activation against tromethamine (tris). For allergic patients to the BNT162b2 vaccine, a significant increase in basophil activation for the BNT162b2 vaccine was found (CD63+basophils: 15.4 ± 1.3%, P = 0.030) (Fig. 1C), but not for PEG 2000 (sensitivity = 27.3%, 3 positives in 11 patients).

We further performed SPT for five patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced acute urticaria accompanied by anaphylaxis, but all these five patients showed negative results against SARS-COV-2 vaccine or its excipients (data not shown).

3.3. Immune mediators involved in patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergy and delayed urticaria

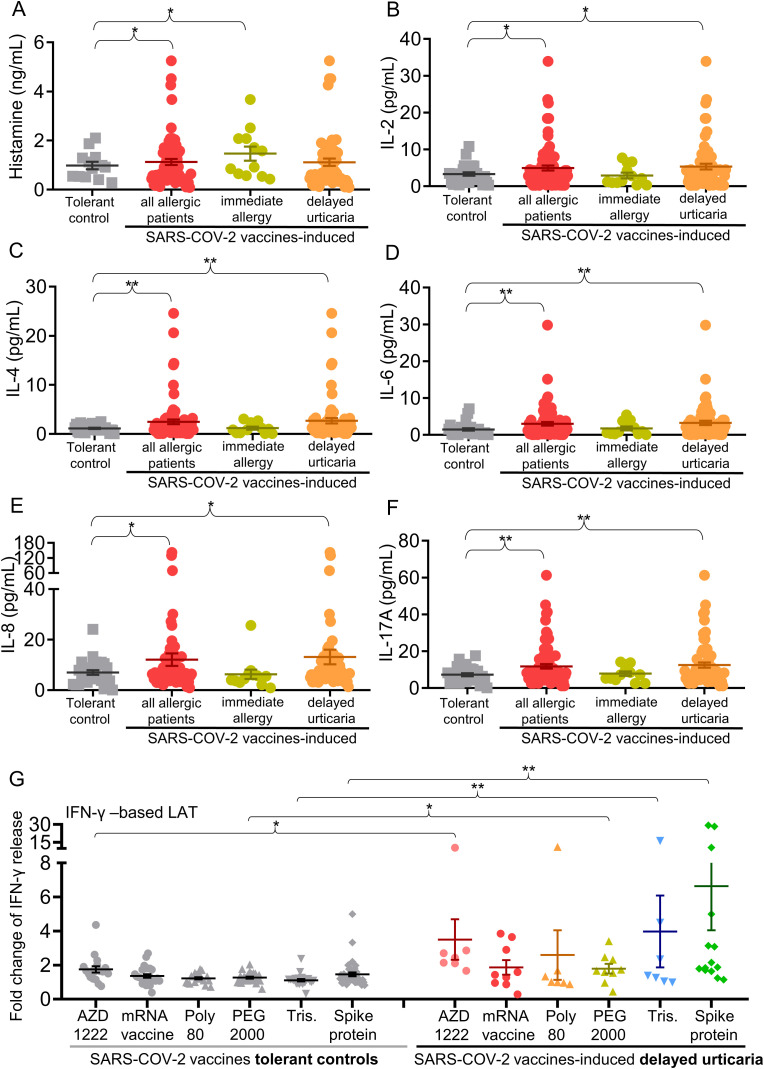

We screened 20 different inflammatory proteins, cytokines, and chemokines in the blood of patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergy and urticaria. Compared to tolerant subjects, all allergic patients had significantly higher serum levels of histamine, interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-17 A (1.4 – 2.2-fold increase; P-values = 0.002–0.039) (Fig. 2 A–F). Serum histamine level was significantly increased in immediate allergic patients (P = 0.034) (Fig. 2A), while IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-17 A levels were increased in patients with delayed urticaria induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines (P = 0.002–0.031) (Fig. 2B–F).

Fig. 2.

Mast cell and T cell-mediated cytokine expressions involved in patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions.

A-F, serum levels of histamine, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-17 A, were measured in 80 patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions (including 12 patients with immediate allergy and 68 with delayed urticaria) and 28 SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls. Immediate allergy represents the onset of the allergic reactions within 24 h, while the delayed urticaria represents the onset after 24 h. G, IFN-γ-based LAT assay were performed for 15 patients with COVID-19 vaccines-induced delayed urticaria (including 7 patients with AZD1222 vaccine-induced and 8 patients with SARS-COV-2 mRNA vaccine-induced) and 44 with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls (including 18 AZD1222 vaccine-tolerant subjects and 26 SARS-COV-2 mRNA vaccine-tolerant subjects). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0 0.01, calculated by 2-tailed Student's t-test.

Abbreviation: IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL-2, interleukin-2; LAT, lymphocyte activation test; PEG, polyethylene glycol; Tris, tromethamine.

Additionally, all SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced allergic patients had significantly higher chemokine levels of TARC/CCL17, PARC/CCL18, and MIG/CXCL9 compared to tolerant subjects (1.5 – 3.0-fold increase; P = 4.5 × 10−5–0.017) (Supplementary Figs. 2A–C). Serum TARC/CCL17, PARC/CCL18, MIG/CXCL9, and MIP-1β/CCL4 levels were significantly increased in patients with delayed urticaria induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines (P = 2.8 × 10−5–0.043) (Supplementary Figs. 2A–D).

As T cell-mediated cytokines and chemokines were significantly elevated in patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced allergic group comparing to tolerant group (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2), we proposed that T cells might be also involved in pathogenesis of SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced allergic reactions, especially in delayed urticaria. We then performed lymphocyte activation test (LAT) by evaluating the IFN-γ level [41] after vaccines or their components/excipients stimulation (Fig. 2G) for SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced delayed urticarial patients who have negative results for BAT assay. The release of IFN-γ were significantly increased against the AZD1222 vaccine itself (3.5 ± 1.2-fold increase; P = 0.034), PEG 2000 (1.8 ± 0.2-fold increase; P = 0.016), tromethamine (2.4 ± 2.1-fold increase; P = 0.001), and the spike protein (3.4 ± 2.8-fold increase; P = 0.008) (Fig. 2G) in various SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced delayed urticarial patients comparing to tolerant subjects. The finding suggested that SARS-COV-2 vaccines or their components/excipients could also activate T cells and resulted in triggering delayed hypersensitivity or urticarial reactions.

As most of our enrolled allergic patients were women, we also measured the serum estradiol that is known as the enhancer of humoral immunity and seems to regulate the cell proliferation or cytokine production in autoimmune disorders [42,43]. However, there was no significant difference of serum estradiol level between the allergic and tolerant groups (Supplementary Figs. 3A–B).

3.4. An increased level of anti-PEG IgG1 in patients with SARS-cov-2 mRNA vaccines-induced allergy and urticaria

We then screened the serum levels of anti-PEG IgE/IgG levels and anti-spike protein (of SARS-CoV-2) IgE/IgG for patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergy and urticaria. Compared to tolerant subjects, a significant increased anti-PEG IgG level was observed in all allergic patients (P = 0.047) or delayed urticarial patients (P = 0.031) induced by SARS-COV-2 mRNA vaccines (Supplementary Fig. 4A). To further examine the IgG subclass against PEG, we found only anti-PEG IgG1 level was significant increased in all allergic patients (P = 0.0016) or delayed urticarial patients (P = 0.0023) induced by SARS-COV-2 mRNA vaccines (Supplementary Figs. 4C–F). However, there was no statistical difference in serum levels of anti-PEG IgE (Supplementary Fig. 4B) and anti-spike protein IgE/IgG (Supplementary Figs. 5A–B) between the allergic and tolerant groups.

3.5. Risk factors of patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced chronic urticaria (CU)

Among our enrolled allergic patients, we found 57 patients have developed prolonged and chronic urticaria (CU) (symptoms >6 weeks; and all patients were antihistamine-resistant) after SARS-COV-2 vaccinations. The clinical characteristics of SARS-COV-2 vaccine-induced CU patients were shown in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced chronic urticaria and tolerant controls.

| Characteristics | SARS-COV-2 vaccines- induced chronic urticaria (>6 weeks) n = 57 | SARS-COV-2 vaccines tolerant controls n = 115 |

OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 49.9 ± 16.5 | 47.5 ± 15.1 | – | 0.371a |

| Onset time of ADR, n (%) | – | |||

| Acute reactions (within 24 h) | 9 (15.8%) | – | – | |

| Delayed reactions (after 24 h) | 48 (84.2%) | – | – | |

| Culprit/Received SARS-COV-2 vaccine, n (%) | – | |||

| AZD1222 | 13 (22.8%) | 27 (23.5%) | – | |

| mRNA-1273 | 34 (59.6%) | 40 (34.8%) | – | |

| BNT162b2 | 9 (15.8%) | 19 (16.5%) | – | |

| MVC-COV1901 | 1 (1.8%) | 3 (2.6%) | – | |

| CoronaVac | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Mix vaccines | – | 25 (21.7%) | – | |

| Inducing dosage of SARS-COV-2 vaccination, n (%) | – | |||

| 1st dose | 31 (54.4%) | 0 (0%) | – | |

| 2nd dose | 12 (21.1%) | 67 (58.3%) | – | |

| 3rd dose | 14 (24.6%) | 48 (41.7%) | – | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 39 (68.4%) | 64 (55.7%) | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) | 0.137 |

| Allergy history and underlying disorders, n (%) | ||||

| Drug hypersensitivity | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (3.5%) | 0.5 (0.1–4.5) | 1.000 |

| Food allergy | 4 (7.0%) | 11 (9.6%) | 0.7 (0.2–2.3) | 0.776 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 6 (10.5%) | 11 (9.6%) | 1.1 (0.4–3.2) | 1.000 |

| Asthma | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.4 (0.0–8.4) | 1.000 |

| Eczema or atopic dermatitis | 2 (1.7%) | 8 (7.0%) | 0.5 (0.1–2.4) | 0.500 |

| SLE | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 2.0 (0.1–33.2) | 1.000 |

| CUb | 5 (8.8%) | 4 (3.5%) | 2.7 (0.7–10.3) | 0.160 |

| Thyroid disease | 5 (8.8%) | 1 (0.9%) | 11.0 (1.2–96.2) | 0.016 |

| Laboratory data, positive n (%) | ||||

| Anti-TPO IgG Ab | 16 (28.1%) | 5 (4.3%) | 8.6 (3.0–24.9) | 2.1 × 10−5 |

| ANA | 5 (8.8%) | 4 (3.5%) | 2.7 (0.7–10.3) | 0.160 |

| TSH | 2 (3.5%) | 2 (1.7%) | 2.1 (0.3–15.0) | 0.600 |

| CRP | 7 (12.3%) | 7 (6.1%) | 2.2 (0.7–6.5) | 0.234 |

| Increased total IgE | 20 (35.1%) | 12 (10.4%) | 4.6 (2.1–10.4) | 2.7 × 10−4 |

| D-dimer | 12 (21.1%) | 6 (5.2%) | 4.8 (1.7–13.7) | 0.003 |

| Leukocytosis | 4 (7.0%) | 7 (6.1%) | 1.2 (0.3–4.2) | 1.000 |

| Eosinophilia | 5 (8.8%) | 7 (6.1%) | 1.5 (0.4–4.9) | 0.535 |

| Basophilia | 1 (1.8%) | 4 (3.5%) | 0.5 (0.1–4.5) | 1.000 |

| Treatment, n (%) | – | |||

| Anti-histamines | 57 (100%) | – | – | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 30 (52.6%) | – | – | |

| Corticosteroids | 34 (59.6%) | – | – | |

| Azathioprine | 7 (12.3%) | – | – | |

| Cyclosporine | 13 (22.8%) | – | – | |

| Doxepin | 12 (21.1%) | – | – | |

| Omalizumab | 6 (10.5%) | – | – | |

Thyroid disease contains hyperthyroidism, Graves' disease, and thyroid cancer.

The normal ranges of the laboratory data were described as: anti-TPO Ab <5.6 IU/mL; ANA negative (<1:40); TSH: 0.27–4.2 μIU/mL; total IgE: adult<100 KU/L; D-Dimer <0.55; cut-off<0.5; probability of exclusion of PE/DVT is 95% mg/L FEU; CRP <5 mg/L; leukocytosis: WBC male >10.6 and female >11 1000/μL; eosinophilia: >500/μL; basophilia >1%.

Anti-histamines include diphenhydramine, ketotifen, levocetirizine, dexchlorpheniramine, fexofenadine, etc.

Abbreviation: ADR, adverse drug reaction; ANA, antinuclear IgG antibody; Anti-TPO Ab, anti-thyroid peroxidase IgG antibody; BAT, basophil activation test; CRP, C-reactive protein; CU, chronic urticaria; PEG, polyethylene glycol; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

*P values were calculated by Fisher's exact test and obtained from comparison of SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced chronic urticarial patients (symptoms >6 weeks; resistant to antihistamine therapy) with relevant SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls.

This P values were calculated by Student's t-test.

The CU history was occurred before vaccination and there was no any symptom for 6 months before vaccination.

Out of these CU patient, 9 (15.8%) patients had acute reactions within 24 h of the vaccinations, and delayed reactions after 24 h were experienced by 48 patients (84.2%). The mRNA-1273 vaccine (59.6%) was the culprit of the CU, followed by the AZD1222 vaccine for 22.8% of patients, and BNT162b2 in 15.8% of cases. The onset of the CU was at the first dose for most patients (54.4%), while 21.1% of patients experienced this response upon the second dose, and 24.6% upon the third dose. There is no statistical different of allergy history between SARS-COV-2 vaccines-CU and control groups. Interestingly, we identified that patients with underlying thyroid disease (e.g., hyperthyroidism, Graves' disease and thyroid cancer) (OR = 11.0, 95% CI = 1.2–96.2, P = 0.016), elevated anti-TPO IgG (OR = 8.6, 95% CI = 3.0–24.9, P = 2.1 × 10−5), and total IgE levels (OR = 4.6, 95% CI = 2.1–10.4, P = 2.7 × 10−4) were significantly found in more patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU than in tolerant controls (Table 2).

We then analyzed the differences between SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients and non-CU patients, and found that the elevated anti-TPO IgG (P = 0.010; Supplementary Table 2), higher TNF-α and lower TARC levels (P < 0.05; Supplementary Figs. 6A and 6B) were observed in SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients comparing to non-CU patients.

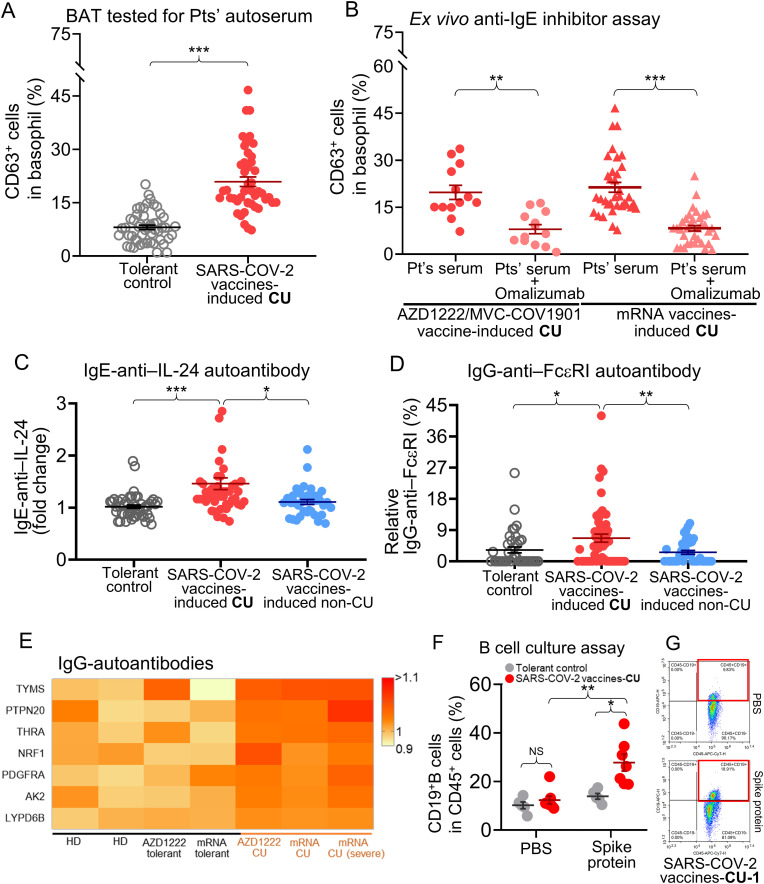

3.6. Autoantibodies against autoantigens in patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced autoimmune CU

Next, we performed an BAT stimulated by patients' autoserum (Fig. 3 A) which was reported as a useful ex vivo detection method for patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) [40]. We found significantly higher CD63+basophil expression in the SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU group than in the tolerant groups (CD63+basophils: 20.9 ± 1.3%, positive in 81.3% of SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients, P = 4.2 × 10−13 compared to tolerant controls) (Fig. 3A). When samples were pretreated with anti-IgE antibody-omalizumab, the percentage of activated basophils was significantly lower than when untreated patients’ samples from those reacting to the AZD1222/MVC-COV1901 vaccine were used (CD63+ basophils: 19.8 ± 2.3% and 8.0 ± 1.5%, before and after omalizumab treatment, respectively; P = 0.004) and mRNA SARS-COV-2 vaccines (CD63+basophils: 21.4 ± 1.7% and 8.0 ± 0.8%, before and after omalizumab treatment, respectively; P = 5.7 × 10−9) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Autoreactive antibodies involved in pathomechanism of patients with chronic urticaria induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines.

A, comparison of the percentage of activated CD63+ basophils as assessed by BAT assay which stimulated with patients' serum from available 48 patients who experienced CU induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines and 51 SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant subjects. B, an ex vivo anti-IgE inhibitor (omalizumab) assay were performed by BAT assay stimulated with different SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients' serum with or without pretreatment of omalizumab. C, anti-IL-24 IgE levels were measured for 48 patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU (symptom >6 weeks), 32 patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced non-CU (symptom ≤6 weeks), and 51 SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant subjects. D, anti-FcεRI IgG levels were measured for 48 patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU, 32 patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced non-CU, and 51 SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant subjects. E, the heatmap plot shows a significant increase of IgG autoantibodies against several proteins (autoantigens), such as TYMS, PTEN20, THRA, etc., in pooled 6 serum samples from patients with different SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU, SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant subjects, and non-received SARS-COV-2 vaccine HD. F, an ex vivo B cell culture assay of spike protein stimulation was performed for 7 patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU (including 2 patients with AZD1222 vaccine-induced and 5 patients with SARS-COV-2 mRNA vaccine-induced) and 4 with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls. G, subsets of CD3+CD19+ B cells detected by flow cytometry for the SARS-COV-2 vaccine-induced CU-1 patient after spike protein stimulation for 1 week was shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0 0.01, and ***P < 0 0.001 calculated by 2-tailed Student's t-test.

Abbreviation: AK2, Adenylate Kinase 2; BAT, basophil activation test; chronic urticaria; HD, healthy donors, LYPD6B, LY6/PLAUR Domain Containing 6 B; NRF1, Nuclear Respiratory Factor 1; PDGFRA, platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha; PTEN20, phosphatase and tensin homolog 20; Pts', patients'; THRA, thyroid hormone receptor alpha; TYMS, thymidylate synthetase.

We screened patient serum for anti-IL-24 IgE, anti-TPO IgE, and anti-Fc epsilon receptor (FcεRI) IgG levels, which are reported to be upregulated in patients with CSU [[44], [45], [46]]. The anti-IL-24 IgE (1.5 ± 0.4-fold increase; P = 6.1 × 10−6) and anti-FcεRI levels (relative 6.7 ± 1.2% increase, P = 0.022) in the SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU group were significantly higher than those in the SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant controls and non-CU patients (Fig. 3C and D, respectively), but not for anti-TPO IgE level (Supplementary Fig. 7). We further screened for IgG anti-autoantigens using an immunome protein microarray, which showed a significant increase of IgG autoantibodies against several autoantigens, such as thymidylate synthetase (TYMS), thyroid hormone receptor alpha (THRA) (all P = 0.048), etc., in patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccine-induced CU as compared to tolerant controls and non-received SARS-COV-2 vaccine healthy donors (HD) (Fig. 3E).

The B cell culture assay was also performed for SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients and SARS-COV-2 vaccines tolerant controls. After stimulation with spike protein for 1 week, we found the CD19+B cells from SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients (percentage of CD19+ B cells: 27.9 ± 2.9%, 2.2-fold increase, P = 0.006) were significantly increased compared to tolerant subjects (Fig. 3F and G), but no statistical difference of CD19+IgD+, CD19+IgM+, and CD19+IgD+IgM+ cells were found between these two groups (Supplementary Figs. 8A–D).

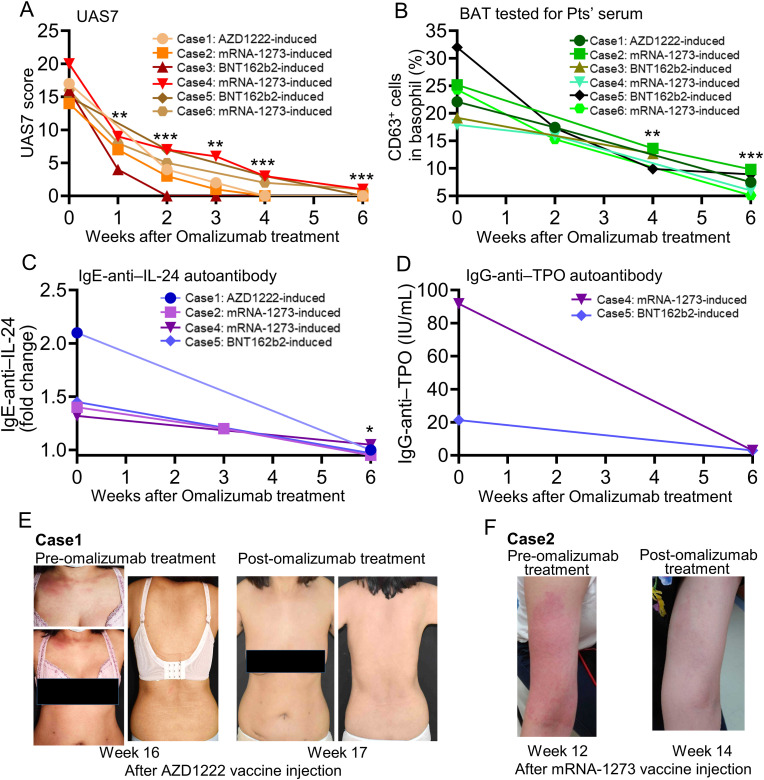

3.7. Management of severe and recalcitrant CU induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccinations by using omalizumab

To evaluate the treatment outcomes, we reported efficacy of combined therapy with oral antihistamines (including diphenhydramine, ketotifen, levocetirizine, etc.), hydroxychloroquine, and one conventional immunosuppressant (e.g., cyclosporine, azathioprine or oral corticosteroids) for most CU patients induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines (Table 2). However, a small number of CU patients (10.5%) were resistant to the conventional therapy. We further utilized the anti-IgE antibody (omalizumab) to treat six patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced recalcitrant CU who had symptoms >12 weeks and were resistant to antihistamines and multiple immunosuppressants. We evaluated the disease activity and severity after omalizumab treatment by UAS7 [47,48](described in the supplement test of Supporting information) which is the recommended evaluation method for patients with CSU [49] based on the current EAACI guideline. Our result showed that patients' UAS7 scores rapidly decreased within the first two weeks of omalizumab treatment and remained low for up to six weeks (Fig. 4 A). Furthermore, the ex vivo BAT tested for patients’ autoserum, anti-IL-24 IgE, and anti-TPO IgG levels also showed a significant decrease after omalizumab treatment, with a normal range of activation measured at week five or six (Fig. 4B–D). The clinical presentation of the two patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccine-induced CU before and after omalizumab treatment were shown in Fig. 4E–F.

Fig. 4.

Anti-IgE therapy (omalizumab) could be used to treat patients with recalcitrant chronic urticaria induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines.

A, the UAS7 scores, B. results of BAT stimulated with patients' serum for six patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced recalcitrant CU before and after an anti-IgE therapy with omalizumab were shown. C, the anti-IL-24 IgE and D, anti-TPO IgG levels for patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced recalcitrant CU were also measured (for patients with high levels before omalizumab treatment) before and after omalizumab treatment, respectively. E, this patient with AZD1222 vaccine-induced (Case 1) recalcitrant CU was resistant to antihistamine, cyclosporine, and oral corticosteroids for more than 12 weeks after vaccination. An anti-IgE blockade therapy (omalizumab) was then administered for this patient (at 16-weeks after vaccination), and the result showed a dramatic skin and symptoms improvement within 1 week. F, this patient with mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced recalcitrant CU (Case 2) was resistant to antihistamine and oral corticosteroids for more than 12 weeks after vaccination. Omalizumab was used to treat with this patient (at 12-weeks after vaccination), and the result showed a dramatic skin and symptoms improvement within 2 weeks. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0 0.01, and ***P < 0 0.001 calculated by 2-tailed Student's t-test.

Abbreviation: anti-TPO, anti-thyroid peroxidase; BAT, basophil activation test; CU, chronic urticaria; Pts', patients'; UAS7, urticaria activity score over 7 days.

3.8. The follow-up of subsequent vaccinations for patients experienced SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions

We tracked whether patients had experienced SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic reactions and chronic urticaria received any subsequent SARS-COV-2 vaccinations (Supplementary Fig. 9). From the enrolled 108 SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced allergic patients, 95 (including 39 patients had developed CU) were included in the study to assess the effects of follow-up (second or third dose) vaccination. Out of 24 patients had not perform ex vivo test, 20 decided to receive further SARS-COV-2 vaccination. Nine patients received another SARS-COV-2 vaccine as the follow-up, the other eleven patients that had experienced mRNA SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced hyperreactivity still received the same type of SARS-COV-2 vaccine again but was premedicated with oral antihistamines or corticosteroids. However, four patients (20%, 4/20) further relapsed itchy and skin rash (Supplementary Fig. 9, left).

In the group of 71 patients with a positive result of ex vivo allergy test (by vaccine itself or its excipients), eight refused further vaccination. Out of the remaining 63 patients received subsequent SARS-COV-2 vaccination by changing to alternative SARS-COV-2 vaccine or performing premedications. One (1.6%, 1/63) patient who were pretreated with oral antihistamines and corticosteroids before vaccination still relapsed severe and chronic urticaria, and a total of 4 patients (6.3%, 4/63) further relapsed cutaneous adverse reactions (Supplementary Fig. 9, right).

4. Discussion

Immediate allergy and urticaria are one of most common adverse reactions induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines and may cause public vaccine hesitancy [50] for following vaccination. In this study, we assessed the clinical characteristics and immune mechanisms of patients with immediate allergic and autoimmune urticarial reactions induced by different SARS-COV-2 vaccines. The ex vivo BAT analysis showed basophils were significantly activated by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine, PEG 2000 or spike protein for patients with allergic reactions to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines, whereas those from patients with AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine-related allergy were activated by AstraZeneca vaccine and polysorbate 80, but not for tolerant subjects. This study firstly determined that the spike protein and the excipient of mRNA-1273 vaccine-tromethamine were also as one of the culprit allergen(s) for patients with immediate allergic and urticarial reactions induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines by ex vivo BAT and LAT assay.

We found an elevation of mast cell/T cell-mediated cytokines and chemokines were involved in the SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions, and higher serum levels of T cell-related cytokines (such as IL-2, IL-4, and IL-17 A) and chemokines (e.g., TARC/CCL17, PARC/CCL18, and MIG/CXCL9) were mainly found in patients with delayed urticaria induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines. The IFN-γ-based LAT result further showed that SARS-COV-2 vaccines or their components/excipients could significantly increase the T cell-mediated IFN-γ release in SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced delayed urticaria patients (who have negative results for BAT assay) comparing to SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant subjects. To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide the comprehensive immune profiling for patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced allergic reactions, especially in delayed urticaria.

Since the majority of the patients that developed allergic reactions induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines was female, the estrogen receptor and toll-like receptor signaling have been reported to be involved in female patients with autoimmune diseases [43,[51], [52], [53]]. However, in this study, no significant difference of serum estradiol level was found between the allergic and tolerant groups. Additional studies need further investigate the role of toll-like receptor signaling in female patients with allergic reactions induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines. Moreover, we found that anti-PEG IgG1 level was significantly elevated in SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines-induced allergy and delayed urticaria patients comparing to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines-tolerant subjects. We further utilized ex vivo BAT stimulated with patients’ autoserum and showed basophil could be activated in 81.3% of SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU (antihistamine-resistant) patients. A further analysis of autoreactive IgE-autoantibodies (anti-IL-24) and IgG-autoantibodies (e.g., anti-TPO, anti-FcεRI, anti-TYMS and anti-THRA) were significantly increased in these CU patients compared with those in tolerant subjects. Specific IgE and IgG autoantibodies are known to be involved in the pathogenesis of CSU [[44], [45], [46],54]. It has been reported that lower total IgE level [55], and higher IgE-anti-IL-24 [44]/anti-IgG-anti-TPO autoantibodies [[55], [56], [57]] levels are found in autoimmune CSU patients. Autoreactive anti-TPO IgE and IgG autoantibodies or thyroid-related autoantibodies have been suggested to activate mast cells, resulting in mast cell degranulation and histamine release [[58], [59], [60]]. In this study, we identified that patients with underlying thyroid disease showed a higher risk for SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU and upregulated levels of total IgE, IgE-anti-IL24, IgG-anti-TPO (but not IgE-anti-TPO), IgG-anti-FcεRI, IgG-anti-TYMS, and IgG-anti-THRA autoantibodies in patients with CU induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines, suggesting that several patients developed urticarial reactions (especially with prolonged course) after SARS-COV-2 vaccination were through autoreactive autoimmune reactions triggered by SARS-COV-2 vaccines. And, the autoreactive antibodies produced from SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients were different from those in CSU patients.

The generation of autoreactive IgE of SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients is still poorly understood. SARS-COV-2 vaccinations is known to induce the adaptive immune reactions to achieve their protective effect, but may also stimulate a hyperinflammatory condition. The mRNA-containing lipid nanoparticles had been shown to be able to trigger inflammatory responses, and release a variety of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in animal models [61]. In this study, patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU also showed a hyperinflammatory condition with elevated cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-17 A TARC/CCL17, PARC/CCL18, and MIG/CXCL9. In addition, there have been increasing reports that patients receiving SARS-COV-2 vaccines developed autoreactive antibodies of autoimmune diseases, such as SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, and immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia [62,63]. The reasons for patients developed autoreactive antibodies associated with autoimmune disorders may be due to the genetic susceptibility (such as HLA class II) [63] and cross-reactivity between foreign peptides and homologous endogenous peptides [24,63,64]. Our results revealed the increased levels of autoreactive IgE/IgG antibodies against thyroid related proteins, TPO, and IL-24 in patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU. The TPO and IL-24 antigens had also been reported to have a similar molecular mimicry [65].

A possible solution for these patients could be the use of the anti-IgE biologic agent omalizumab. Here we further found that in an ex vivo inhibition assay, pretreatment with omalizumab significantly reduced basophil activation in SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU samples. Additionally, we show that an anti-IgE therapy-omalizumab could successfully treat SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced recalcitrant CU patients who had failed conventional therapy. Although sample size is limited, expansion of this cohort is therefore warranted.

A low risk has been found in patients with immediate allergic reactions induced by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine who received a second dose [13,22,23], but one previous registry-based study showed that 43% of patients who reported cutaneous reactions after a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine had a recurrence in response to the second dose [11], suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine-induced cutaneous reactions may be through different mechanisms. Patients who experience immediate allergic reactions after a dose of SARS-COV-2 vaccine, receiving fractionated vaccine dose or premedication before subsequent vaccination are suggested to prevent allergic responses [13,18,23,[66], [67], [68], [69]]. In our cohort study, there were approximately 6.3–20% of patients who had experienced SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergy and chronic urticaria further relapsed itchy and skin rash after following vaccination by premedications or alternative SARS-COV-2 vaccination. Performing ex vivo tests may help to identify the main culprit component or excipient of vaccines and cross-reactivity of different vaccines to decrease the incidence of cutaneous reactions induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines.

There are still several limitations for this study, including I) the small sample size of SARS-COV-2 vaccines-tolerant subjects, and some of these enrolled subjects still have fever, chills or fatigue after vaccinations; II) the allergy history and underlying disorders of patients and tolerant subjects relied on the subjects’ statement, and misclassification of diseases might occur for few subjects; III) the blood samples from active stage of patients with SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic reactions were hard to collect, we mainly analyzed the cytokine/chemokine profiles for SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced delayed to chronic urticaria. Moreover, we did not investigate the non-antibody mediated pathway (e.g., MRGPRX2- [70] or complements-mediated pathway [66]) for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines-induced immediate allergic patients.

5. Conclusions

Although the development of severe allergic reactions following SARS-COV-2 vaccination is rare, our study provides an overview of the risk factors, immune profiles and autoreactive antibodies associated with SARS-COV-2 vaccine-induced immediate allergic and urticarial reactions. Increased levels of mast cell/T cell-mediated inflammatory cytokines and autoreactive IgE/IgG antibodies (such as anti-TPO IgG, anti-IL24 IgE, anti-FcεRI IgG, anti-PEG IgG, anti-thyroid-related proteins IgG, etc.) are strongly linked to autoimmune CU induced by SARS-COV-2 vaccines. Omalizumab shows as an effectively biologic agent for treatment with some SARS-COV-2 vaccines-induced CU patients who had failed conventional therapy. Our study provides the comprehensive characteristics and immune profiling that can be applied to improve diagnosis and treatment outcome as well as to reduce the incidence of immediate allergic and autoimmune urticarial reactions induced by vaccines.

Author contributions

CWW: Writing - Original Draft. CWW, CBC, WTT, and YJP: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis. CWW, CBC and CWL: Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization. CBC, CWL, WTC, RCYH, TMC, MHC, JCL, YHH, YCC, JW, KYC, YYWL, and WHC: Resources. WHC: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing.

Ethics approval

Each subject enrolled in this study provided written informed consent, and the study protocol for the de-identified research use of blood samples collections, ex vivo testing, clinical data, and follow-up of subsequent vaccinations was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) and ethics committee of each hospital based on Taiwan's laws and regulations (IRB No. 202000512A3, 202101436B0, 202101404B0A3, and 202102216A3).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC 108-2314-B-182A-104 -MY3, 110-2320-B-182A-014-MY3, 110-2326-B-182A-003-, 111-2326-B-182A-003-, 111-2314-B-182A-113-MY3), and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CORPG3L0471-2).

Data sharing statement

Technical appendix and dataset available from the corresponding author, who will provide a permanent, citable and open access home for the dataset.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the statistical assistance and wish to acknowledge the support of Dr. Chee-Jen Chang, from Research Services Center for Health Information, Chang Gung University, Taiwan for study design and monitor, data analysis and interpretation.

Handling Editor: M.E. Gershwin

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2023.103054.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai L., Gao G.F. Viral targets for vaccines against COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021;21:73–82. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00480-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voysey M., Clemens S.A.C., Madhi S.A., Weckx L.Y., Folegatti P.M., Aley P.K., et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh S.M., Liu M.C., Chen Y.H., Lee W.S., Hwang S.J., Cheng S.H., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of CpG 1018 and aluminium hydroxide-adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 S-2P protein vaccine MVC-COV1901: interim results of a large-scale, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial in Taiwan. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021;9:1396–1406. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00402-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y., Zeng G., Pan H., Li C., Hu Y., Chu K., et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18-59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021;21:181–192. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30843-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson L.A., Anderson E.J., Rouphael N.G., Roberts P.C., Makhene M., Coler R.N., et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1920–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falsey A.R., Sobieszczyk M.E., Hirsch I., Sproule S., Robb M.L., Corey L., et al. Phase 3 safety and efficacy of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:2348–2360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goel R.R., Apostolidis S.A., Painter M.M., Mathew D., Pattekar A., Kuthuru O., et al. Distinct antibody and memory B cell responses in SARS-CoV-2 naive and recovered individuals following mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol. 2021;6 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abi6950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catala A., Munoz-Santos C., Galvan-Casas C., Roncero Riesco M., Revilla Nebreda D., Sola-Truyols A., et al. Cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a cross-sectional Spanish nationwide study of 405 cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022;186:142–152. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMahon D.E., Amerson E., Rosenbach M., Lipoff J.B., Moustafa D., Tyagi A., et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: a registry-based study of 414 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021;85:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabanillas B., Akdis C.A., Novak N. COVID-19 vaccines and the role of other potential allergenic components different from PEG. A reply to: "Other excipients than PEG might cause serious hypersensitivity reactions in COVID-19 vaccines". Allergy. 2021;76:1943–1944. doi: 10.1111/all.14761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krantz M.S., Bruusgaard-Mouritsen M.A., Koo G., Phillips E.J., Stone C.A., Jr., Garvey L.H. Anaphylaxis to the first dose of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: don't give up on the second dose. Allergy. 2021;76:2916–2920. doi: 10.1111/all.14958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson L.B., Fu X., Hashimoto D., Wickner P., Shenoy E.S., Landman A.B., et al. Incidence of cutaneous reactions after messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1000–1002. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sampath V., Rabinowitz G., Shah M., Jain S., Diamant Z., Jesenak M., et al. Vaccines and allergic reactions: the past, the current COVID-19 pandemic, and future perspectives. Allergy. 2021;76:1640–1660. doi: 10.1111/all.14840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borgsteede S.D., Geersing T.H., Tempels-Pavlica Z. Other excipients than PEG might cause serious hypersensitivity reactions in COVID-19 vaccines. Allergy. 2021;76:1941–1942. doi: 10.1111/all.14774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimabukuro T., Nair N. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. JAMA. 2021;325:780–781. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbaud A., Garvey L.H., Arcolaci A., Brockow K., Mori F., Mayorga C., et al. An ENDA/EAACI Position paper; Allergy: 2022. Allergies and COVID-19 Vaccines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimabukuro T. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine - United States, December 21, 2020-January 10, 2021. Am. J. Transplant. 2021;21:1326–1331. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimabukuro T. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine - United States, December 14-23, 2020. Am. J. Transplant. 2021;21:1332–1337. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelso J.M., Greenhawt M.J., Li J.T., Nicklas R.A., Bernstein D.I., Blessing-Moore J., et al. Adverse reactions to vaccines practice parameter 2012 update. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012;130:25–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krantz M.S., Kwah J.H., Stone C.A., Jr., Phillips E.J., Ortega G., Banerji A., et al. Safety evaluation of the second dose of messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccines in patients with immediate reactions to the first dose. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021;181:1530–1533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu D.K., Abrams E.M., Golden D.B.K., Blumenthal K.G., Wolfson A.R., Stone C.A., Jr., et al. Risk of second allergic reaction to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022;182:376–385. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.8515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worm M., Vieths S., Mahler V. An update on anaphylaxis and urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022;150:1265–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hide M., Kaplan A.P. Concise update on the pathogenesis of chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022;150:1403–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolkhir P., Munoz M., Asero R., Ferrer M., Kocaturk E., Metz M., et al. Autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022;149:1819–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bianchi L., Biondi F., Hansel K., Murgia N., Tramontana M., Stingeni L. Skin tests in urticaria/angioedema and flushing to Pfizer-BioNTech SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: limits of intradermal testing. Allergy. 2021;76:2605–2607. doi: 10.1111/all.14839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelso J.M. Misdiagnosis of systemic allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;127:133–134. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustafa S.S., Ramsey A., Staicu M.L. Administration of a second dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine after an immediate hypersensitivity reaction with the first dose: two case reports. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021;174:1177–1178. doi: 10.7326/L21-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park H.J., Montgomery J.R., Boggs N.A. Anaphylaxis after the covid-19 vaccine in a patient with cholinergic urticaria. Mil. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1093/milmed/usab138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Restivo V., Candore G., Barrale M., Caravello E., Graziano G., Onida R., et al. Vol. 9. Vaccines; Basel): 2021. (Allergy to Polyethilenglicole of Anti-SARS CoV2 Vaccine Recipient: A Case Report of Young Adult Recipient and the Management of Future Exposure to SARS-CoV2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rojas-Perez-Ezquerra P., Crespo Quiros J., Tornero Molina P., Baeza Ochoa de Ocariz M.L., Zubeldia Ortuno J.M. Safety of new mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 in severely allergic patients. J Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2021;31:180–181. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sellaturay P., Nasser S., Islam S., Gurugama P., Ewan P.W. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a cause of anaphylaxis to the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2021;51:861–863. doi: 10.1111/cea.13874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vieira J., Marcelino J., Ferreira F., Farinha S., Silva R., Proenca M., et al. Skin testing with Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and PEG 2000. Asia Pac Allergy. 2021;11:e18. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2021.11.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murayama H., Sakuma M., Takahashi Y., Morimoto T. Vol. 6. Pharmacol Res Perspect; 2018. (Improving the Assessment of Adverse Drug Reactions Using the Naranjo Algorithm in Daily Practice: the Japan Adverse Drug Events Study). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown S.G. Clinical features and severity grading of anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004;114:371–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraft M., Renaudin J.M., Ensina L.F., Kleinheinz A., Bilo M.B., Scherer Hofmeier K., et al. Anaphylaxis to vaccination and polyethylene glycol: a perspective from the European Anaphylaxis Registry. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021;35:e659–e662. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blumenthal K.G., Banerji A. We should not abandon the Brighton Collaboration criteria for vaccine-associated anaphylaxis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:17–19. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2022.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas R.E., Spragins W., Lorenzetti D.L. How many published cases of serious adverse events after yellow fever vaccination meet Brighton Collaboration diagnostic criteria? Vaccine. 2013;31:6201–6209. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curto-Barredo L., Yelamos J., Gimeno R., Mojal S., Pujol R.M., Gimenez-Arnau A. Basophil Activation Test identifies the patients with Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria suffering the most active disease. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2016;4:441–445. doi: 10.1002/iid3.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin C.Y., Wang C.W., Hui C.R., Chang Y.C., Yang C.H., Cheng C.Y., et al. Delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions induced by proton pump inhibitors: a clinical and in vitro T-cell reactivity study. Allergy. 2018;73:221–229. doi: 10.1111/all.13235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guery J.C. Estrogens and inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:560–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cutolo M., Capellino S., Sulli A., Serioli B., Secchi M.E., Villaggio B., et al. Estrogens and autoimmune diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006;1089:538–547. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmetzer O., Lakin E., Topal F.A., Preusse P., Freier D., Church M.K., et al. IL-24 is a common and specific autoantigen of IgE in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018;142:876–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ulambayar B., Park H.S. Anti-TPO IgE autoantibody in chronic urticaria: is it clinically relevant? Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2019;11:1–3. doi: 10.4168/aair.2019.11.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schoepke N., Asero R., Ellrich A., Ferrer M., Gimenez-Arnau A., H E., C G., et al. Biomarkers and clinical characteristics of autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria: results of the PURIST Study. Allergy. 2019;74:2427–2436. doi: 10.1111/all.13949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dressler C., Rosumeck S., Werner R.N., Magerl M., Metz M., Maurer M., et al. Executive summary of the methods report for 'the EAACI/GA(2) LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. The 2017 revision and update'. Allergy. 2018;73:1145–1146. doi: 10.1111/all.13414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mlynek A., Zalewska-Janowska A., Martus P., Staubach P., Zuberbier T., Maurer M. How to assess disease activity in patients with chronic urticaria? Allergy. 2008;63:777–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baiardini I., Braido F., Bindslev-Jensen C., Bousquet P.J., Brzoza Z., Canonica G.W., et al. Recommendations for assessing patient-reported outcomes and health-related quality of life in patients with urticaria: a GA(2) LEN taskforce position paper. Allergy. 2011;66:840–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaplan B., Farzan S., Coscia G., Rosenthal D.W., McInerney A., Jongco A.M., et al. Allergic reactions to coronavirus disease 2019 vaccines and addressing vaccine hesitancy: northwell Health experience. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128:161–168 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pollard K.M. Gender differences in autoimmunity associated with exposure to environmental factors. J. Autoimmun. 2012;38:J177–J186. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merrheim J., Villegas J., Van Wassenhove J., Khansa R., Berrih-Aknin S., le Panse R., et al. Estrogen, estrogen-like molecules and autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weindel C.G., Richey L.J., Bolland S., Mehta A.J., Kearney J.F., Huber B.T. B cell autophagy mediates TLR7-dependent autoimmunity and inflammation. Autophagy. 2015;11:1010–1024. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1052206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He L., Yi W., Huang X., Long H., Lu Q. Chronic urticaria: advances in understanding of the disease and clinical management. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2021;61:424–448. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08886-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kolkhir P., Kovalkova E., Chernov A., Danilycheva I., Krause K., Sauer M., et al. Autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria detection with IgG anti-TPO and total IgE. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021;9:4138–41346 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang L., Qiu L., Wu J., Qi Y., Wang H., Qi R., et al. IgE and IgG anti-thyroid autoantibodies in Chinese patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria and a literature review. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2022;14:131–142. doi: 10.4168/aair.2022.14.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kolkhir P., Metz M., Altrichter S., Maurer M. Comorbidity of chronic spontaneous urticaria and autoimmune thyroid diseases: a systematic review. Allergy. 2017;72:1440–1460. doi: 10.1111/all.13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Landucci E., Laurino A., Cinci L., Gencarelli M., Raimondi L. Thyroid hormone, thyroid hormone metabolites and mast cells: a less explored issue. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019;13:79. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Artantas S., Gul U., Kilic A., Guler S. Skin findings in thyroid diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2009;20:158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rocchi R., Kimura H., Tzou S.C., Suzuki K., Rose N.R., Pinchera A., et al. Toll-like receptor-MyD88 and Fc receptor pathways of mast cells mediate the thyroid dysfunctions observed during nonthyroidal illness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:6019–6024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701319104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ndeupen S., Qin Z., Jacobsen S., Bouteau A., Estanbouli H., Igyarto B.Z. The mRNA-LNP platform's lipid nanoparticle component used in preclinical vaccine studies is highly inflammatory. iScience. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.103479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lemoine C., Padilla C., Krampe N., Doerfler S., Morgenlander A., Thiel B., et al. Systemic lupus erythematous after Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine: a case report. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022;41:1597–1601. doi: 10.1007/s10067-022-06126-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen Y., Xu Z., Wang P., Li X.M., Shuai Z.W., Ye D.Q., et al. New-onset autoimmune phenomena post-COVID-19 vaccination. Immunology. 2022;165:386–401. doi: 10.1111/imm.13443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Segal Y., Shoenfeld Y. Vaccine-induced autoimmunity: the role of molecular mimicry and immune crossreaction. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2018;15:586–594. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2017.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanchez A., Cardona R., Munera M., Sanchez J. Identification of antigenic epitopes of thyroperoxidase, thyroglobulin and interleukin-24. Exploration of cross-reactivity with environmental allergens and possible role in urticaria and hypothyroidism. Immunol. Lett. 2020;220:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hung S.I., Preclaro I.A.C., Chung W.H., Wang C.W. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions induced by COVID-19 vaccines: current trends, potential mechanisms and prevention strategies. Biomedicines. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10061260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Warren C.M., Snow T.T., Lee A.S., Shah M.M., Heider A., Blomkalns A., et al. Assessment of allergic and anaphylactic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines with confirmatory testing in a US regional health system. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sokolowska M., Eiwegger T., Ollert M., Torres M.J., Barber D., Del Giacco S., et al. EAACI statement on the diagnosis, management and prevention of severe allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines. Allergy. 2021;76:1629–1639. doi: 10.1111/all.14739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smola A., Samadzadeh S., Muller L., Adams O., Homey B., Albrecht P., et al. Omalizumab prevents anaphylactoid reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021;35:e743–e745. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Porebski G., Kwiecien K., Pawica M., Kwitniewski M. Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor-X2 (MRGPRX2) in drug hypersensitivity reactions. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:3027. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.