Abstract

Age at exposure is a major modifier of radiation-induced carcinogenesis. We used mouse models to elucidate the mechanism underlying age-related susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis. Radiation exposure in infants was effective at inducing tumors in B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice. Loss of heterozygosity analysis revealed that interstitial deletion may be considered a radiation signature in this model and tumor number containing a deletion correlated with the susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis as a function of age. Furthermore, in Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox mice, deletions of both floxed Apc alleles in Lgr5-positive stem cells in infants resulted in the formation of more tumors than in adults. These results suggest that tumorigenicity of Apc-deficient stem cells varies with age and is higher in infant mice. Three-dimensional immunostaining analyses indicated that the crypt architecture in the intestine of infants was immature and different from that in adults concerning crypt size and the number of stem cells and Paneth cells per crypt. Interestingly, the frequency of crypt fission correlated with the susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis as a function of age. During crypt fission, the percentage of crypts with lysozyme-positive mature Paneth cells was lower in infants than that in adults, whereas no difference in the behavior of stem cells or Paneth cells was observed regardless of age. These data suggest that morphological dynamics in intestinal crypts affect age-dependent susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis; oncogenic mutations in infant stem cells resulting from radiation exposure may acquire an increased proliferative potential for tumor induction compared with that in adults.

Morphological dynamics in intestinal crypts affect age-dependent susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis; oncogenic mutations in infant stem cells resulting from radiation exposure may acquire an increased proliferative potential for tumor induction compared with that in adults.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

It is well-established that exposure to ionizing radiation increases cancer risk. The Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident, which exposed millions of individuals to radioactive contaminants (dose range, 11.0–41.556 Gy), resulted in an increased incidence of thyroid cancer in children (1). Epidemiological studies on the Japanese survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings (dose range, 0–4 Gy) indicated that cancer risk was associated with age at the time of exposure (2–4). Although radiation-induced cancer risk is higher in children compared with adults for all solid cancers, the specific risk with increasing age at the time of exposure is dependent on the origin of the tumor. The relative risk was reduced markedly for thyroid cancer with increasing age at the time of exposure but increased for lung cancer, and was highest around menarche for breast cancer (2,4,5). Therefore, it is important to determine the basis for age-dependent sensitivity to radiation-induced carcinogenesis in individual organs with respect to radiation protection. The application of animal models is indispensable for identifying the mechanism of age-dependent cancer risk (6,7).

The ApcMin/+ (multiple intestinal neoplasia) mouse, which represents a human intestinal cancer model, has a heterozygous germline nonsense mutation in the Apc gene on chromosome 18 (Chr18). The inactivation of the remaining normal Apc allele by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) causes the development of multiple intestinal tumors (8). The ApcMin/+ mouse is a useful in vivo system for identifying the mechanism of radiation-induced tumorigenesis and its age dependence for several reasons. First, the ApcMin/+ mouse is susceptible to environmental factors, such as radiation and chemical agents (9–12). Second, it has a susceptible age window to tumor induction by exogenous mutagens, in which the pre-weaning period after birth is the most susceptible interval to tumorigenesis (10,11). Finally, there are differences in the LOH pattern on Chr18 between spontaneous- and radiation-induced tumors in ApcMin/+ mice, and the interstitial chromosome losses around Apc were identified as a typical LOH pattern following radiation tumorigenesis (13). This indicates that the identification and quantification of the radiation signature by LOH analysis on Chr18 in ApcMin/+ mice may yield evidence for elucidating the age-dependent mechanism of radiation-induced carcinogenesis concerning age.

According to the current model of intestinal carcinogenesis in adult mammals, tumor development is thought to begin with the acquisition of a somatic mutation in an intestinal stem cell within a crypt. Identification of epithelial stem cells in the intestinal tract using conditional gene-targeting technology in mice has confirmed that stem cells are located at the crypt base, representing the origin of intestinal neoplasia (14). The Apc-deficient oncogenic stem cells exhibit increased Wnt signaling and have a clonal advantage as supercompetitors over their wild-type counterparts by inhibiting the proliferation of neighboring wild-type stem cells and inducing their differentiation (15,16). This suggests that the loss of Apc function in stem cells is important as an initial step of carcinogenesis. In addition, recent genetic lineage tracing, single-cell RNA sequencing and three-dimensional (3D) organoid/spheroid culture studies have indicated that there are differences in the location and characteristics of stem and/or precursor cells between the fetal and adult intestines. The stemness properties are malleable during development, in which the stem cell identity of the adult type is induced and the crypt-villus unit of the gut is established during the postnatal periods until weaning (17–20). However, it is unclear whether the behavior of damaged oncogenic stem cells induced by radiation exposure varies with age in the intestine. Therefore, it is important to identify the signature of genomic alterations in the tumors caused by irradiation at different ages, and how it correlates with the susceptibility to radiation-induced tumor risk as a function of age at the time of exposure (21).

Here, we used mouse models with germline or inducible loss of the Apc gene to elucidate the underlying mechanism of age-dependent susceptibility to the tumorigenic effects of radiation by focusing on stem cell dynamics and crypt morphogenesis.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6)-ApcMin/+, B6.129P2-Lgr5tm1(cre/ERT2)Cle/J (Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2), B6.129P2-Apc < tm1Rsmi>/RfoJ (Apcflox/flox) and B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J (R26-TdTomato) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were backcrossed to B6 strain. B6-Chr18MSM mice were kindly provided by Dr T. Shiroishi from the National Institute of Genetics (Mishima, Japan). B6-Chr18MSM mice are a consomic strain established from B6 and MSM/Ms (MSM) mice, in which Chr18 of the B6 strain has been replaced with the corresponding chromosome of the MSM strain. B6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Kanagawa, Japan). It has been reported that intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice is strongly affected by the genetic background (10,22). To investigate the pattern of LOH on Chr18 by using microsatellite markers in radiation-induced tumors from ApcMin/+ mice on B6 background, we generated B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice by crossing B6-ApcMin/+ females and B6-Chr18MSM males. In B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice, only one Chr18 carrying the Apc + gene is derived from the MSM strain, and the rest are from the B6 strain. B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox were generated by crossing Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2 and Apcflox/flox mice. To clarify the difference in tamoxifen usage between neonates and adults, we created a B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox; R26-tdTomato mouse model and measured the number of initial Apc mutant cells in the crypts after tamoxifen treatment. This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Hiroshima University Animal Research Committee. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments at Hiroshima University. All mice were maintained according to the guidelines of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science of Hiroshima University, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Irradiation

Mice were irradiated with an acute dose of 2 Gy gamma rays in a Gammacell 40 Exactor research irradiator equipped with a 148 TBq 137Cs source (Best Theratronics, Ottawa, Canada). Irradiation was carried out at a dose rate of 181 mGy/min using a lead attenuator. The total absorbed dose was calibrated using a GD-302M glass dosimeter (AGC Techno Glass Co., Ltd, Shizuoka, Japan).

Tumor induction

B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice were observed daily after irradiation and killed by exposure to CO2 at 19–24 weeks of age. The concentration of hemoglobin (Hgb) in the peripheral blood was measured using a hygrometer (PCE-310, PCE Instruments, Erma, Tokyo, Japan). B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox were injected intraperitoneally with tamoxifen (MERCK, Japan) at 0.1 to 10 mg/ml (10 μl/g body weight) at 3 weeks or mice over 8 weeks old of age. After 3 months of tamoxifen injection, mice were killed by exposure to CO2 at 16 or over 21 weeks of age. The small intestine was removed, slit longitudinally, rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and divided into three segments: duodenum, jejunum and ileum. We randomly collected approximately 3–5 tumors from each mouse regardless of the tumor size or location. Samples from intestinal tumors were picked up, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until further analysis. The rest of the small intestine was then fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin. Tumors were counted following alkaline phosphatase staining and scored under a dissecting microscope.

Scoring the number of crypts

The crypt number per mouse was defined by multiplying the total number of crypts per area and the total area of the intestine. The small intestinal tract was partitioned into three parts and the total area of each part was measured. Square pieces (5 mm × 5 mm) were cut out from each part of the intestine, washed with PBS, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C. After fixation, samples were immersed in tissue-clearing reagent CUBIC-L (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Japan) overnight, rinsed several times with PBS, nuclei were then counter-stained with 4ʹ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1 μM) (Merck, Japan) and the tissues were immersed in tissue-clearing reagent CUBIC-R (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Japan). Automated imaging was performed on a high content screening system Opera Phenix® (PerkinElmer, Germany) using a water 20X/1.0 NA objective and confocal optical mode. The total number of crypts per area was counted manually from images analyzed by Harmony software package (Perkin Elmer). Crypts undergoing cleavage (crypt fission) were counted as two crypts.

LOH analysis

Genomic DNA from fresh frozen intestinal adenomas and normal intestinal tissue of B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice were extracted and purified using QIAamp DNA micro kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. LOH analysis was performed using microsatellite markers along mouse Chr18. The details of the primer sets used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online. Briefly, genomic DNA from the normal and tumor samples was amplified by PCR for each set of primers. LOH analysis at the Apc locus was performed as previously described (22). Quantification of the PCR products was performed by MultiNA (SHIMADZU, Japan).

Histological analysis

B6-wild-type of mice were killed by exposure to CO2, and the distal part of the intestine was removed immediately. The tissue was rinsed with PBS and fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin for about 12 h. The tissue samples were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned (3 μm thick) and stained with Hematoxylin and eosin or Alcian blue-PAS for histological visualization of sulfated and carboxylated acid mucopolysacccharides/sialomucins.

Preparation and immunostaining of 3D whole-mount tissue

Mice were killed by exposure to CO2, and the intestine was removed immediately. Tissue samples, 5 mm × 5 mm from the distal part of the intestine were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C. The samples were immersed in tissue-clearing reagent CUBIC-L overnight, then rinsed several times with PBS, permeabilized by 1% Triton-X in PBS for 2 h, followed by blocking solution for 2 h (1% bovine serum albumin, 3% normal goat serum, 0.2% Triton-X in PBS). Primary antibodies were diluted in working buffer (0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.3% normal goat serum, 0.2% Triton-X100 in PBS) as follows: anti-Olfm4 (1:500, Abcam, UK), anti-Lysozyme (1:500, Abcam, UK) and Rhodamine-labeled phalloidin (1:500, Thermo Fisher, Japan). Samples were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 days at 4°C on a circular motion shaker at 70 rpm. The samples were then washed three times with PBS-T (0.1% Tween®20 in PBS) and incubated with secondary antibody goat-anti-rabbit Alexa Flour 488 (1:400, Thermo Fisher, Japan) and goat-anti-rabbit Alexa Flour 555 overnight at 4°C. Finally, samples were washed three times with PBS, and nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI in PBS. The specimens were then transferred to 96-well plates, and immersed in tissue-clearing reagent CUBIC-R in preparation for image acquisition. Automated imaging was performed on a high content screening system Opera Phenix® using a water 20X/1.0 NA objective and confocal optical mode and Z-stacks were taken at 0.8 μm steps. Images were analyzed by Harmony software package.

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (Kruskal–Wallis) using Graph Pad Prism software package or chi-square test using the StatMate III software package (ATMS), and a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Age-dependence on radiation-induced tumorigenesis in B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice

To examine the age-dependence effect on radiation-induced tumorigenesis in mice, B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice were divided into six groups and each group was exposed to whole-body γ-irradiation at a dose of 2 Gy at different ages (Figure 1A). All animals were killed at 19–24 weeks of age before the mice were moribund. As shown in Figure 1B, tumor induction following γ-irradiation was dependent upon age at the time of exposure. The number of tumors per mouse increased above the spontaneous level following exposure of mice to γ-irradiation from postnatal day 1 (P1) to P41, with a peak at P11 and P21, whereas exposure at a dose of 2 Gy on P61 did not affect tumor induction in B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice. The ileum was the predominate site for tumor formation of the intestine in all groups, although the group irradiated on P1 showed a different tumor distribution (Supplementary Table 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Given that the development of intestinal adenoma causes anemia, we also measured Hgb concentration in the peripheral blood and the weight of the spleen was an indicator of extramedullary hematopoiesis (Supplementary Table 3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The mean Hgb level decreased and the relative spleen weight increased in the P1, P11 and P21 compared with the nonirradiated group (Supplementary Table 3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Based on the Hgb levels and the relative spleen weight, the frequency of mice with anemia (Hgb level < 5g/dl) was significantly higher in the P1, P11 and P21 irradiated groups compared with the nonirradiated group.

Figure 1.

The effect of age at exposure on radiation-induced tumorigenesis in B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice. (A) Experimental scheme. B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice were divided into six groups and exposed to whole-body irradiation at a dose of 2 Gy at various ages after birth. The mice were then killed at approximately19–24 weeks of age [the nonirradiated group (n = 15) and five irradiated groups with irradiation at P1 (n = 11), P11 (n = 12), P21 (n = 11), P41 (n = 11) and P61 (n = 11)]. (B) Relationship between radiation-induced tumor number per mouse and age at the time of exposure in B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice. The mean number of intestinal tumors per mouse is shown. A Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate the differences in medians among the groups. *P < 0.05 versus the nonirradiated control group. (C) Microsatellite DNA (MIT)-based LOH analysis in spontaneous and radiation-induced intestinal tumors from B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice. The pattern of LOH was detected in this study. Duplication: allelic loss observed at all consecutive markers with normal copy number. Deletion: allelic loss only at interstitial markers around the Apc gene, in which the copy number reduction with distal markers was retained. Unidentified: neither LOH with copy number reduction on Chr18. (D) Proportion of individual LOH patterns in each group (Duplication; white, Unidentified; gray and Deletion; dark). (E) Relationship between age at exposure and the number of tumors containing each type of LOH. Solid line shows the mean of the nonirradiated control group and the Dash lines show the 95% confidence intervals.

To confirm the age-dependent sensitivity to radiation-induced tumorigenesis, B6/B6-F1 ApcMin/+ mice at P14 or P49 of age were exposed to whole-body γ-irradiation at a dose of 2 Gy and then killed at 24 weeks of age. Irradiation with 2 Gy on P14 exhibited increased intestinal tumor formation by a factor of 2.3 (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). No significant change in intestinal tumorigenesis was observed following irradiation at P49 in B6/B6-F1 ApcMin/+ mice, suggesting that there is a window of susceptibility to tumor formation following irradiation in B6/B6-F1, in addition to, B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice. Thus, the preweaning stage after birth is the most susceptible period.

LOH analysis of Chr18 in the intestinal tumors of B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice

The inactivation of the remaining normal Apc allele by LOH results in the development of multiple intestinal tumors in ApcMin/+ mice. Haines et al. suggested that the pattern of LOH on Chr18 in radiation-induced intestinal tumors is different from that of spontaneous tumors in ApcMin/+ mice (13). To examine the pattern of LOH on Chr18 and to identify a radiation signature that may define age-dependent susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis, we evaluated microsatellite-based LOH on Chr18 in B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice (Figure 1C; Supplementary Figure 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The tumors were classified into the following three types: duplication, deletion and unidentified (Figure 1C; Supplementary Figure 2, available at Carcinogenesis Online). A duplication event showed LOH at all consecutive markers on Chr18 with normal gene copy numbers for Chr18 (data not shown). A deletion resulted in interstitial losses around the Apc locus with distal markers retained. The remaining tumors showed no LOH at all microsatellite markers, which we designated as unidentified. In the nonirradiated group, a duplication was detected in approximately two-thirds of the tumors analyzed, whereas the remaining were unidentified (Figure 1D and E). An interstitial deletion was detected in tumors from the irradiated groups, but not in the nonirradiated group (Figure 1D and E). The proportion of tumors containing a deletion decreased with increasing age (Figure 1D). The number of tumors bearing an interstitial deletion per mouse increased significantly at P1, P11 and P21 and also increased, but not significantly, in the groups irradiated at P41 (Figure 1E). Interestingly, a correlation was observed between the number of tumors induced by radiation and the number of tumors containing an interstitial deletion as a function of age at the time of exposure. Concerning the number of tumors containing a duplication per mouse, there was no difference between the nonirradiated and irradiated groups, except on day 1, when the duplication-containing tumor number per mouse was lower. Radiation exposure did not affect the number of tumors containing the unidentified genotype per mouse.

Age-dependent tumorigenicity of Apc-deficient stem cells in B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox mice

An interstitial deletion detected in tumors from B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice is probably caused by radiation exposure in intestinal stem cells. To determine age-dependent tumorigenicity in stem cells that have lost Apc function, we used the B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox mouse model in which deletion of the floxed Apc allele in Lgr5-expressing stem cells can be induced spatiotemporally by tamoxifen treatment. Various concentrations of tamoxifen (0.1, 1 and 10 mg/ml) were injected into B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox mice at 3 weeks or over 8 weeks of age (Figure 2A). The mice treated with the highest concentration of tamoxifen at 3 weeks were killed because they were moribund at 1 month following tamoxifen treatment, whereas the rest were killed after 3 months of tamoxifen treatment. Tumor incidence was significantly higher in B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox mice at 3 weeks of age following tamoxifen (1 and 10 mg/ml) injection compared with that of adult mice of at least 8 weeks of age (Figure 2B). Next, to clarify the difference in tamoxifen usage between neonates and adults, we used a B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox; R26-tdTomato mouse model and measured the number of initial Apc mutant Lgr5-positive cells after tamoxifen treatment. After 1 day of tamoxifen treatment, no difference in the mean volume of tdTomato-positive cells per crypt was observed between 3-week-old and 8-week-old mice (Supplementary Figure 3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). After 2 weeks of tamoxifen treatment, the volume of tdTomato-positive cells per crypt was higher in 3-week-old mice than that in 8-week-old mice (Supplementary Figure 3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). These data suggest that oncogenic stem cells are more likely to acquire a proliferative potential, which results in tumor induction in the infant’s intestine compared with that in the adult intestine.

Figure 2.

Age-dependent tumorigenicity of Apc-deficient Lgr5-expressing stem cells in B6-Lgr5-CreERT2, Apcflox/flox mice. (A) Experimental scheme. Various concentrations of tamoxifen (0.1, 1 and 10 mg/ml) were injected into mice at 3 weeks and over 8 weeks of age in B6-Lgr5-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox mice. (B) Tumorigenicity of Apc-deficient Lgr5-expressing stem cells induced by tamoxifen treatment at different ages in the B6-Lgr5-CreERT2, Apcflox/flox mice. The mean number of intestinal tumors per mouse is shown. A Student’s t-test was used to evaluate differences in medians among groups.

Changes in the architecture of crypts during intestinal development

During morphogenesis, the identity of adult-type stem cells is induced and the crypt-villus unit of the gut is established (Supplementary Figure 4, available at Carcinogenesis Online) (18,19,23). Thus, we first examined normal development in the unirradiated wild-type mouse intestine to determine the specific characteristics of crypt architecture that may affect susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis as a function of age. Histological analysis revealed that crypts were not detected at P1 and there were clusters of epithelial cells in the inter-villus region (Figure 3A). The crypt structure was initially observed at P11 and the crypt length and width increased until P41, although no difference was observed in crypt size between P41 and P61 (Figure 3A and B). The number of crypts per mouse was quite low at P1 and began to increase at P11 along with intestinal growth. It became constant after P21, whereas the growth of the intestinal crypt continued until P41 (Figure 3C). These data indicate that there is no relationship between the size and number of crypts and sensitivity to radiation-induced tumorigenesis. At P1, we did not observe any Paneth cells that are known as a niche, whereas Villi and PAS-stained goblet cells were already formed at P1. Paneth cells emerged infrequently at the base of the crypt at P11. The number of Paneth cells per crypt increased from P11 to P41 (Figure 3A). After P41, the crypt contained Paneth cells with numerous granules at the base region. At P11 and P21, we observed a bifid crypt (i.e. a crypt with two bases) resulting from crypt fission. These observations indicate that morphological dynamic changes occur in the intestine, such as crypt formation and amplification, during the postnatal periods until weaning and that the crypt architecture during these periods differs from that of adults.

Figure 3.

Developmental changes in crypt number and size during the postnatal stage. (A) Photomicrographs of intestinal tissue sections at the indicated days after birth. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (upper panel) and Alcian Blue-PAS (lower panel). The arrow shows crypt fission. The arrowhead shows granules containing Paneth cells. Scale bars: 20 μm. (B) The crypt length (left figure) and width (right figure) of the intestine at the indicated days after birth. Data are presented as means ± SD from four or five mice. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate differences in medians among groups. *P < 0.05 versus P1 group. †P < 0.05 versus P11 group. §P < 0.05 versus P21 group. (C) Developmental changes in the number of crypts per mouse. Data are presented as means ± SD from three mice. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate differences in medians among groups. *P < 0.05 versus P1 group. The crypt undergoing crypt fission was counted as two crypts.

Next, we stained whole-mounted mouse intestinal tissues with antibodies against Olfm4 to identify stem cells or lysozyme as mature Paneth cell markers. 3D image analysis was performed for quantitation. The Olfm4-positive stem cells were detected in the inter-villus region at P1 and remained in the base of the crypt after P11 (Figure 4A). The Olfm4-positive volume per crypt expanded gradually from P1 until P41 and then plateaued (Figure 4B). We detected Olfm4-positive stem cells in all crypts regardless of age (Figure 4B). Lysozyme-positive Paneth cells were not detected at P1, although a few were detected in the base region of the crypt at P11 (Figure 4A). The lysozyme-positive volume per crypt was constant at a low level until P21 and expanded markedly at P41, whereas there was no difference from P41 to P61 (Figure 4B). The percentage of crypts with lysozyme-positive cells was approximately 20% at P11 and increased to about 80% on P21 (Figure 4B). All crypts contained lysozyme-positive Paneth cells in the bottom regions after P41. Our data indicate that the number of stem and Paneth cells per crypt in infants differs from that in adult mice. The percentage of crypts with lysozyme-positive Paneth cells was lower in infants compared with that in adults.

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of crypt morphogenesis. (A) Immunofluorescence images of intestinal crypts stained with DAPI and antibody against Olfm4 (upper panel) and lysozyme (lower panel) in 3D. Scale bars: 100 μm. (B) Top: 3D volume of Olfm4-positive regions (left) and lysozyme-positive regions (right) per crypt at the indicated days after birth. Data are presented as means ± SD from three mice. Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate differences in medians among groups. *P < 0.05 versus P1 group. †P < 0.05 versus P11 group. §P < 0.05 versus P21 group. Bottom: the proportion of Olfm4-positive crypts (left) and lysozyme-positive crypts (right) at the indicated days after birth. The chi-square test was used to evaluate differences in each group. *P < 0.05 versus P1 group.

Age-dependent frequency of crypt fission and its characteristics

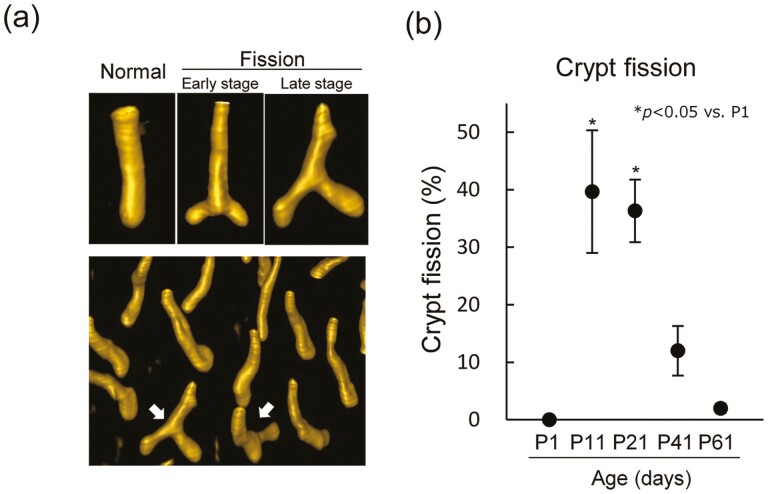

We frequently observed fissioning crypts at P11 and P21 by histological analysis, and the quantitative analysis of crypt fission was performed using whole-mounted tissues stained with phalloidin, which is a F-actin probe and known as a marker for the apical surface of the epithelium that provides information about 3D crypt structure. The regions stained with phalloidin were not detected at P1. After P11, we observed different stages of fission based on the position of bifurcation relative to the crypt base, similar to that reported by Landlands et al. (Figure 5A) (24). During the early stage of crypt fission, the length of the two daughter crypts was short and the branch point was close to the edge of the crypt base. As crypt fission progressed, the length of the daughter crypt became longer and the bifurcation point of fission was further from the crypt base (Figure 5A). We scored the frequency of crypt fission regardless of stage. The frequency was significantly higher at P11 and P21 and then declined with age, whereas only approximately 2% of the crypts underwent fission at P61 (Figure 5B). There was a correlation between sensitivity to radiation-induced tumorigenesis and the frequency of crypt fission as a function of age. The frequency of crypt fission was constant following 2 Gy irradiation in adult mice, whereas it was decreased at 24 h after 2 Gy irradiation in infant mice, but was higher compared with that in adults (Supplementary Figure 5, available at Carcinogenesis Online).

Figure 5.

Frequency of crypt fission during postnatal development. (A) Immunofluorescence images of intestinal crypts during crypt fission stained with phalloidin. The arrow shows a crypt undergoing fission. (B) Frequency of crypt fission during postnatal development isolated from mice. Graphs show the incidence of crypt fission. Crypts undergoing fission were counted in each group, with 100–200 crypts counted in each mouse. Data are presented as means ± SD from three mice. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate differences in medians among groups. *P < 0.05 versus P1 group.

Next, we used Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mice to visualize crypt fission, stem cells and Paneth cells by 3D image analysis to determine their position and behavior during the process of crypt fission at P11, P21 and P61 (Figure 6A). All crypts contained Lgr5-positive stem cells regardless of age or the process of crypt fission, and the volume began to increase until P41 after birth as shown in Figure 4 (Figure 6A and Supplementary Video S1–S9, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The position of Lgr5-positive stem cells varied depending on the stage of crypt fission and the behavior was the same regardless of age. At the early stage of crypt fission, regardless of age, Lgr5-positive stem cells formed a cluster in the region of bifurcation (Figure 6A and Supplementary Figures 6 and 7, available at Carcinogenesis Online). During the late stage of crypt fission, we observed two independent daughter crypts, in which the Lgr5-positive cells were located on the edge of the crypt base, not at the bifurcation. Zero to four lysozyme-positive Paneth cells were detected at P11 and P21 and were intermingled with Lgr5-positive stem cells in an alternating pattern at P61 (Figure 6A and Supplementary Figure 6, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Regardless of age or stage of crypt fission, Paneth cells were located at the edge of the daughter crypt base, not in the region of bifurcation during the process of crypt fission as reported previously (Supplementary Figures 6 and 7, available at Carcinogenesis Online) (24). Interestingly, as shown by the arrow in Figure 6A, we observed Lgr5-and lysozyme-negative areas in the bottom of the crypt at P11 and P21, but not at P61, which may represent immature Paneth cells. We observed at least one lysozyme-positive Paneth cell or Lgr5-/lysozyme-negative space on the edge of the base during crypt fission at P11 and P21. As shown in Figure 6B, the percentage of crypts with lysozyme-positive Paneth cells during crypt fission was much lower in infants compared with that in adults. This suggests that during the process of crypt fission, there is a difference in the crypt architecture between infants and adults, even though there was no difference in the behavior of the stem cells and Paneth cells.

Figure 6.

Location of Lgr5-positive stem cells and Paneth cells during crypt fission at the indicated days after birth. (A) Immunofluorescence images. Rhodamine phalloidin and the antibody against lysozyme were used to visualize F-actin (yellow) and lysozyme (red), respectively. The Lgr5-positive (GFP-positive) stem cells are shown in green. Pictures are from the side or the top of the crypt. Scale bars: 20 μm. The arrow shows the lysozyme-negative and Lgr5-negative space at the bottom of the crypt. (B) Proportion of the crypts with mature Paneth cells at the edge of the crypt base during crypt fission at P11 and P61.

Discussion

We confirmed that there is a susceptible age window to tumor induction following radiation exposure in B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice as reported previously in the B6/B6-F1 ApcMin/+ mouse model (10). Ellender et al. also analyzed how age at exposure affected susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis using CBA/H/B6-F1 ApcMin/+ mice, wherein mice were euthanized approximately 200 days after irradiation (in utero, 2, 10 and 35 days after birth), that is, mice were euthanized at different weeks of age at the time of euthanasia, and analyzed for tumor multiplicity (11). The highest tumor incidence was observed in mice that were irradiated at 10 days of age. Irradiation may increase the intestinal tumor number most frequently at 2–3 weeks of age, but not at the young adult stage (10). A similar age-dependency was observed for tumors induced by chemical mutagens in ApcMin/+ mice and Apc+/+ wild-type mice (10,11,25–27). Morioka et al. reported that X-ray irradiation at 2 weeks, but not 7 weeks of age, significantly increased tumor incidence in mismatch repair-deficient Mlh1−/− female mice (28). These data suggest that the intestine is most susceptible to tumor induction by exogenous mutagens during the preweaning periods in mice after birth. To determine the relationship between age-dependent sensitivity to radiation-induced tumorigenesis and the pattern of wild-type allele loss of Apc in intestinal tumors of ApcMin/+ mice, we examined microsatellite-based LOH analysis on Chr18 in B6/B6-Chr18MSM-F1 ApcMin/+ mice. We detected an interstitial deletion in the tumors from the irradiated groups, but not in the nonirradiated group. Consistently, Haines et al. reported interstitial deletions in intestinal tumors from 2 Gy X-irradiated AKR/B6-F1 ApcMin/+ mice (7/12, 58%), but not in nonirradiated mice (0/11, 0%). Interestingly, our data revealed that there was a correlation between radiation-induced tumor number and the number of tumors containing interstitial deletions as a function of age at the time of exposure. Thus, interstitial deletions may be considered a reliable radiation signature and a major factor in this model that contributes to the susceptibility of radiation-induced intestinal tumorigenesis depending on age at the time of exposure in ApcMin/+ mice, although we did not elucidate whether it is a universal phenomenon. DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are thought to be the main cause of cell death after radiation exposure (29). If DSBs are not repaired correctly, DSBs can cause genetic and chromosomal abnormalities, such as deletions and translocations (29). Deletion frequency is reportedly increased after radiation exposure in a dose-dependent manner (30). Nonetheless, the reasons why the number of tumors containing interstitial deletions is dependent on age at the time of exposure, with a peak of 2–3 weeks of age, and why interstitial deletions were not detected in the tumors from the irradiated group of adults, such as P61 mice, is unclear. A variety of possible mechanisms have been proposed, which include differences in the stem/progenitor cell number as the target cells for the initiation of tumorigenesis and the fate of damaged oncogenic stem cells through the acquisition of proliferative capacity or elimination pathways (21,31–35).

To determine whether the fate of damaged oncogenic stem cells in the intestines varies with age, we used the B6-Lgr5-eGFP-ires-CreERT2; Apcflox/flox mouse model. Tumor incidence was much higher when tamoxifen was injected into infant mice compared with that of adults, suggesting that susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis may be affected by the proliferative potential of oncogenic stem cells. Oncogenic stem cells are more likely to acquire a proliferative potential, which leads to tumor induction in infant mice, but not in adults. Furthermore, we found that the crypt architecture in the infant’s intestine was immature and different from that in adults concerning crypt size and the number of stem and Paneth cells per crypt, although the crypt-villus unit was already established at P11 as previously reported (Supplementary Figure 4, available at Carcinogenesis Online) (18,19,23). Interestingly, there was a correlation between radiation-induced tumor number and the frequency of crypt fission as a function of age. The frequency of crypt fission was most prevalent in infant mice. Furthermore, during the process of crypt fission, the percentage of the lysozyme-positive mature Paneth cells at the edge was lower in infant mice compared with that in adults, whereas there was no difference in the behavior of the stem cells and the Paneth cells, regardless of age. Thus, the data suggests that there is some association between the immature crypt architecture and the frequency of crypt fission that contributes to the susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis. Yui et al. reported that the fate of stem cells in adult mice was changed to a primitive state during colonic regeneration in a murine dextran sulfate sodium colitis model (36). During recovery from dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis, in which rapid crypt fission and hyperplasia were observed in the intestine, a change of stem cell fate is orchestrated by remodeling the extracellular matrix to regain its normal architecture. This suggests that there is an association between the immature characteristics of the crypt stem cell and the environment prone to crypt fission. Stzepourginski et al. identified CD34 + Gp38 + crypt stromal cells (known as CD34+ CSCs) as a major component of the intestinal epithelial stem cell niche (37). Interestingly, they showed that CD34+ CSCs develop after birth. We also detected CD34+ CSCs in the intestine of 8-week-old but not 2-week-old animals (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 8, available at Carcinogenesis Online). There was an inverse correlation between the frequency of crypt fission and the proportion of CD34+ CSCs in the intestine as a function of age (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 8, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Stzepourginski et al. also showed that the proportion of CD34+ CSCs was changed during intestinal repair after injury, suggesting that intestinal homeostasis and repair require the coordinated action of functionally distinct subsets of mesenchymal cells in adult mice. The importance of stem–stromal interactions mediated by the extracellular matrix has been demonstrated for stem cell maintenance in other organs besides the intestinal tract (21). It has been hypothesized that cancer can be promoted by an abnormal stroma (21,38). While it is unclear whether the regulatory mechanism of crypt fission in infants is identical or different from those of injury-induced crypt fission for regeneration in adults, we presume that oncogenic mutations in intestinal stem cells in an environment prone to crypt fission, such as during intestinal morphogenesis and injury-induced regeneration, may promote the acquisition of proliferative potential, rather than during normal tissue steady-state homeostasis in adults. Future studies will be needed to identify the mechanism that regulates crypt fission and the interaction between stem cells and stromal cells during the process of crypt fission, and how its regulatory pathways affect the susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis.

In the present study, the Olfm4-positive stem cell number did not correlate with susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis. Whereas when the Olfm4-positive stem cell number per crypt/mouse was the lowest at P1 postpartum, we observed the highest percentage of tumors containing interstitial deletions in intestinal tumors from the P1 group compared with that from the other irradiated groups (Figure 1D). This suggests that oncogenic stem cells exposed to irradiation may acquire a proliferative potential at P1, thus radiation exposure at P1 did not result in the highest tumorigenicity because of the low number of target stem cells in the intestine. We hypothesize that the combined effects of stem cell number and the immature crypt architecture/crypt fission may be factors that contribute to susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis. Alternatively, the radiation-induced tumorigenesis mechanism in the irradiated group at P1 might be unique, given that the crypt-villus units are not formed. At present, the radiation-induced tumorigenesis mechanism at P1 irradiation is unknown. Further studies are required to clarify this mechanism.

Miyoshi-Imamura et al. reported that intestinal epithelial cells are more resistant to radiation-induced apoptosis in neonatal and infant mice compared with adults (31). This suggests that radiation-induced damage to cells in the crypts may be cleared more efficiently in adult mice compared with that in neonates and infants (39–43). Apoptosis may be one of the modifying factors contributing to the age-dependent susceptibility to radiation tumorigenesis by eliminating oncogenic stem cells.

We observed body weight loss in P11 and P12 and mean Hgb level reduction in P1, P11 and P21 (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). A negative correlation was observed between tumor number and body weight/Hgb level in the present study (Supplementary Figure 9, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This suggests that tumor burden affects body weight and Hgb level. Interestingly, it has been reported that neonatal irradiation on the day of birth induces long-term effects, such as body weight loss at 7 weeks of age (44). While we were unable to reach any conclusion in the present study, further studies are needed to elucidate if irradiation itself directly affects weight loss and Hgb level reduction observed in this study.

Epidemiological evidence from the Life Span Study of atomic bomb survivors has demonstrated that the excess relative risk for all solid cancers decreases with increasing age at the time of exposure. However, it is not clear whether the effect of age at the time of exposure on radiation-induced carcinogenesis applies to all organs. Rodent models, such as ApcMin/+ mice, provide data for the organ-specific effect of age at the time of exposure to radiation-induced tumorigenesis (6,7,32–34,45,46). The Ptch1 heterozygous mice, which were established as a model of human Gorlin syndrome, are sensitive to radiation-induced medulloblastomas during a narrow window of time centered on the days around birth when the cerebellum size is progressively increasing (7,35). Eker rats represent a model of human tuberous sclerosis that carries a heterozygous germline mutation in the Tsc2 tumor suppressor gene. They are also susceptible to radiation-induced renal carcinogenesis at the time of birth when the kidney is actively growing (32). A radiobiological study in wild-type B6C3H female mice by Sasaki revealed that infant mice are more susceptible to radiation-induced liver tumors, whereas adult mice are more susceptible to radiation-induced myeloid leukemia (46,47). This suggests that there is a susceptible age window for radiation-induced tumorigenesis depending on the organ. We postulate that the morphological dynamics of an organ during development and the environment conducive to stem cell proliferation affect the susceptibility to radiation-induced carcinogenesis. Future studies using animal models will provide insight into the mechanism of age-dependent susceptibility to radiation-induced carcinogenesis in individual organs. Interestingly, it was reported that interstitial deletion was detected in tumors from irradiated groups in animal models that have heterozygous germline mutations in certain tumor suppressor genes, such as Ptch1+/− mice, Eker rats and ApcMin/+ mice (32,35). Based on this evidence, we believe that interstitial deletion might be detected as a radiation signature in tumors induced by exposure during highly susceptible periods to radiation carcinogenesis in the models such as ApcMin/+ mice. Similarly, Morton et al. observed a radiation dose-dependent increase in small deletions from a large-scale integrated genomic landscape analysis of thyroid cancers after the Chernobyl accident with detailed dose estimation (48). Although the identification of radiation signatures, such as driver gene mutations and gene alterations, is currently under investigation in radiation-induced thyroid cancer in children, we hypothesize that radiation-induced deletions in driver genes of stem cells are involved in high susceptibility to radiation-induced thyroid cancer in children. Brenner et al. reported the incidence of breast cancer in the Life Span Study of atomic bomb survivors and described that age at the menarche was a strong modifier of the radiation effect (49). The mammary gland is a highly dynamic organ that undergoes profound changes within its epithelium during puberty and the reproductive cycle (50). These changes are fueled by dedicated stem and progenitor cells (50). Although the detailed mechanism by which irradiation during sensitive periods might stimulate breast cancer development remains unknown, there is more support for changes in tissue composition and stem cell regulation after irradiation. Further studies are required to clarify the mechanism of radiation-induced carcinogenesis during the susceptible period in organs such as the thyroid and mammary glands.

In summary, using a mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis, we found that the susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis is associated with age at the time of exposure and that it may be affected by factors, such as the immature crypt architecture and crypt fission, or perhaps by a combination of factors along with stem cell number. Our data suggest that the acquisition of proliferative capacity in mutant stem cells after irradiation is one of the important factors contributing to high susceptibility to radiation-induced tumorigenesis in neonates. Since the role of the microenvironment around stem cells in radiation carcinogenesis remains unknown, we are conducting research to clarify how the stem cell microenvironment is involved in radiation carcinogenesis in neonates and adults.

We speculate that there may be differences in the mechanism of radiation-induced tumorigenesis depending on age at the time of exposure. This is important concerning radiation protection to estimate the effects of age at exposure on susceptibility to radiation-induced carcinogenesis in individual organs and to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank for the assistance with this project technical staff, Jami Maki, Kaori Kunii, Mika Odamoto, Nozomi Fukuda, Mika Morishima, Ryoko Yamasaki, Akiko Sone, Miki Nakamura, Ryo Fukuda and Yuki Sakai in our laboratory. We also thank Shinji Suga, Shingo Sasatani and Mariko Morozumi (Radiation Research Center for Frontier Science Facilities) for their assistance with irradiation. We are also grateful to Dr Ohtsura Niwa, Dr Ryo Kominami, Dr Yuji Masuda, Dr Ritsu Sakata and Dr Hiromi Sugiyama for useful discussions. The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 3D

three-dimensional

- B6

C57BL/6

- Chr18

chromosome 18

- DSB

double strand break

- Hgb

hemoglobin

- LOH

loss of heterozygosity

- Min

multiple intestinal neoplasia

- MSM

MSM/Ms

- P1

postnatal day1

- PSB

phosphate-buffered saline

Contributor Information

Megumi Sasatani, Department of Experimental Oncology, Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan.

Tsutomu Shimura, Department of Environmental Health, National Institute of Public Health, Saitama 351-0197, Japan.

Kazutaka Doi, Center for Radiation Protection Knowledge, National Institute of Radiological Sciences (NIRS), National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST), Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Elena Karamfilova Zaharieva, Department of Experimental Oncology, Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan.

Jianxiang Li, Department of Toxicology, School of Public Health, Medical College of Soochow University, Suzhou, Jiangsu 21512, China.

Daisuke Iizuka, Department of Radiation Effects Research, National Institute of Radiological Sciences (NIRS), National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST), Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Shinpei Etoh, Department of Experimental Oncology, Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan.

Yusuke Sotomaru, Natural Science Center for Basic Research and Development, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan.

Kenji Kamiya, Department of Experimental Oncology, Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8551, Japan.

Funding

Research project on the Health Effects of Radiation organized by Ministry of the Environment, Japan. Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (MEXT) (17K00553, 17H00785, 17H06284, 20K21846, 22H03754, 25281020), and the Nuclear Energy S&T and Human Resource Development Project (JPMX15S15657561). This work was also supported in part by the NIFS Collaborative Research Program (NIFS13KOBA028, NIFS17KOCA0002, NIFS20KOCA004).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Tronko, M., et al. (2017) Thyroid neoplasia risk is increased nearly 30 years after the Chernobyl accident. Int. J. Cancer, 141, 1585–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Preston, D.L., et al. (2003) Studies of mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 13: solid cancer and noncancer disease mortality: 1950–1997. 2003. Radiat. Res., 178, AV146–AV172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ozasa, K., et al. (2012) Studies of the mortality of atomic bomb survivors, Report 14, 1950–2003: an overview of cancer and noncancer diseases. Radiat. Res., 177, 229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grant, E.J., et al. (2017) Solid cancer incidence among the life span study of atomic bomb survivors: 1958–2009. Radiat. Res., 187, 513–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bernier, M.O., et al. (2019) Cohort profile: the EPI-CT study: a European pooled epidemiological study to quantify the risk of radiation-induced cancer from paediatric CT. Int. J. Epidemiol., 48, 379–381g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Imaoka, T., et al. (2017) Age modifies the effect of 2-MeV fast neutrons on rat mammary carcinogenesis. Radiat. Res., 188, 419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pazzaglia, S., et al. (2009) Physical, heritable and age-related factors as modifiers of radiation cancer risk in patched heterozygous mice. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys., 73, 1203–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ren, J., et al. (2019) The application of ApcMin/+ mouse model in colorectal tumor researches. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol., 145, 1111–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shoemaker, A.R., et al. (1998) A resistant genetic background leading to incomplete penetrance of intestinal neoplasia and reduced loss of heterozygosity in ApcMin/+ mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 95, 10826–10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okamoto, M., et al. (2005) Intestinal tumorigenesis in Min mice is enhanced by X-irradiation in an age-dependent manner. J. Radiat. Res., 46, 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ellender, M., et al. (2006) In utero and neonatal sensitivity of ApcMin/+ mice to radiation-induced intestinal neoplasia. Int. J. Radiat. Biol., 82, 141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morioka, T., et al. (2021) Calorie restriction suppresses the progression of radiation-induced intestinal tumours in C3B6F1 ApcMin/+ mice. Anticancer Res., 41, 1365–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haines, J., et al. (2000) Loss of heterozygosity in spontaneous and X-ray-induced intestinal tumors arising in F1 hybrid min mice: evidence for sequential loss of APC+ and Dpc4 in tumor development. Genes Chromosom. Cancer, 28, 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barker, N., et al. (2009) Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature, 457, 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flanagan, D.J., et al. (2021) NOTUM from Apc-mutant cells biases clonal competition to initiate cancer. Nature, 594, 430–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Neerven, S.M., et al. (2021) Apc-mutant cells act as supercompetitors in intestinal tumour initiation. Nature, 594, 436–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mustata, R.C., et al. (2013) Identification of Lgr5-independent spheroid-generating progenitors of the mouse fetal intestinal epithelium. Cell Rep, 5, 421–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guiu, J., et al. (2019) Tracing the origin of adult intestinal stem cells. Nature, 570, 107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yanai, H., et al. (2017) Intestinal stem cells contribute to the maturation of the neonatal small intestine and colon independently of digestive activity. Sci. Rep., 7, 9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sprangers, J., et al. (2021) Organoid-based modeling of intestinal development, regeneration, and repair. Cell Death Differ., 28, 95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niwa, O., et al.; ICRP. 2015) ICRP Publication 131: stem cell biology with respect to carcinogenesis aspects of radiological protection. Ann. ICRP, 44, 7–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luongo, C., et al. (1994) Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer Res., 54, 5947–5952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmidt, G.H., et al. (1988) Development of the pattern of cell renewal in the crypt-villus unit of chimaeric mouse small intestine. Development, 103, 785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Langlands, A.J., et al. (2016) Paneth cell-rich regions separated by a cluster of Lgr5+ cells initiate crypt fission in the intestinal stem cell niche. PLoS Biol., 14, e1002491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shoemaker, A.R., et al. (1995) N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea treatment of multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) mice: age-related effects on the formation of intestinal adenomas, cystic crypts, and epidermoid cysts. Cancer Res., 55, 4479–4485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Claij, N., et al. (2003) DNA mismatch repair deficiency stimulates N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mutagenesis and lymphomagenesis. Cancer Res., 63, 2062–2066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shoemaker, A.R., et al. (1997) Somatic mutational mechanisms involved in intestinal tumor formation in Min mice. Cancer Res., 57, 1999–2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morioka, T., et al. (2015) Ionizing radiation, inflammation, and their interactions in colon carcinogenesis in Mlh1-deficient mice. Cancer Sci., 106, 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deriano, L., et al. (2013) Modernizing the nonhomologous end-joining repertoire: alternative and classical NHEJ share the stage. Annu. Rev. Genet., 47, 433–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nagashima, H., et al. (2018) Induction of somatic mutations by low-dose X-rays: the challenge in recognizing radiation-induced events. J. Radiat. Res., 59, ii11–ii17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miyoshi-Imamura, T., et al. (2010) Unique characteristics of radiation-induced apoptosis in the postnatally developing small intestine and colon of mice. Radiat. Res., 173, 310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Inoue, T., et al. (2020) Interstitial chromosomal deletion of the tuberous sclerosis complex 2 locus is a signature for radiation-associated renal tumors in Eker rats. Cancer Sci., 111, 840–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Imaoka, T., et al. (2019) Prominent dose-rate effect and its age dependence of rat mammary carcinogenesis induced by continuous gamma-ray exposure. Radiat. Res., 191, 245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Imaoka, T., et al. (2009) Radiation-induced mammary carcinogenesis in rodent models: what’s different from chemical carcinogenesis? J. Radiat. Res., 50, 281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tsuruoka, C., et al. (2016) Sensitive detection of radiation-induced medulloblastomas after acute or protracted gamma-ray exposures in Ptch1 heterozygous mice using a radiation-specific molecular signature. Radiat. Res., 186, 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yui, S., et al. (2018) YAP/TAZ-dependent reprogramming of colonic epithelium links ECM remodeling to tissue regeneration. Cell Stem Cell, 22, 35–49.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stzepourginski, I., et al. (2017) CD34+ mesenchymal cells are a major component of the intestinal stem cells niche at homeostasis and after injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 114, E506–E513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barcellos-Hoff, M.H. (1998) The potential influence of radiation-induced microenvironments in neoplastic progression. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia, 3, 165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maskens, A.P., et al. (1981) Kinetics of tissue proliferation in colorectal mucosa during post-natal growth. Cell Tissue Kinet, 14, 467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng, H., et al. (1985) Whole population cell kinetics and postnatal development of the mouse intestinal epithelium. Anat. Rec., 211, 420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Al-Nafussi, A.I., et al. (1982) Cell kinetics in the mouse small intestine during immediate postnatal life. Virchows. Arch. B Cell Pathol. Incl. Mol. Pathol., 40, 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim, B.M., et al. (2007) Phases of canonical Wnt signaling during the development of mouse intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology, 133, 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dehmer, J.J., et al. (2011) Expansion of intestinal epithelial stem cells during murine development. PLoS One, 6, e27070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nash, D.J., et al. (1970) Neonatal irradiation and postnatal behavior in mice. Radiat. Res., 41, 594–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yamada, Y., et al. (2017) Effect of age at exposure on the incidence of lung and mammary cancer after thoracic X-ray irradiation in wistar rats. Radiat. Res., 187, 210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sasaki, S. (1991) Influence of the age of mice at exposure to radiation on life-shortening and carcinogenesis. J. Radiat. Res., 32, 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Doi, K., et al. (2020) Estimation of dose-rate effectiveness factor for malignant tumor mortality: joint analysis of mouse data exposed to chronic and acute radiation. Radiat. Res., 194, 500–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Morton, L.M., et al. (2021) Radiation-related genomic profile of papillary thyroid carcinoma after the Chernobyl accident. Science, 372, eabg2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brenner, A.V., et al. (2018) Incidence of breast cancer in the life span study of atomic bomb survivors: 1958–2009. Radiat. Res., 190, 433–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Samocha, A., et al. (2019) Unraveling heterogeneity in epithelial cell fates of the mammary gland and breast cancer. Cancers, 11, 1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.