Abstract

Complex disaster situations like the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) create macro-level contexts of severe uncertainty that disrupt industries across the globe in unprecedented ways. While occupational health research has made important advances in understanding the effects of occupational stressors on employee well-being, there is a need to better understand the employee well-being implications of severe uncertainty stemming from macro-level disruption. We draw from the Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress (GUTS) to explain how a context of severe uncertainty can create signals of economic and health unsafety at the industry level, leading to emotional exhaustion through paths of economic and health anxiety. We integrate recent disaster scholarship that classifies COVID-19 as a transboundary disaster and use this interdisciplinary perspective to explain how COVID-19 created a context of severe uncertainty from which these effects unfold. To test our proposed model, we pair objective industry data with time-lagged quantitative and qualitative survey responses from 212 employees across industries collected during the height of the initial COVID-19 response in the United States. Structural equation modeling results indicate a significant indirect effect of industry COVID-19 unsafety signals on emotional exhaustion through the health, but not economic, unsafety path. Qualitative analyses provide further insights into these dynamics. Theoretical and practical implications for employee well-being in a context of severe uncertainty are discussed.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Transboundary disaster, Emotional exhaustion, Health anxiety, Economic anxiety, Generalized unsafety

Many scholars agree that society faces a future of increasing risks, danger, and uncertainty, with impacts spanning all sectors and industries (Botzen et al., 2019; de Ruiter et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2020). Occupational health science has been particularly effective at minimizing recognized risks to employee health and well-being in general, and theoretical advancements have improved our understanding of major risks like disasters and crises (e.g., Hällgren et al., 2018; Schweizer et al., 2022). In addition to being at the core mission of our field, employee well-being is of critical concern because organizations play a major role in society’s ability to respond to and recover from major disruptions as well as return to a sense of normalcy (Lee et al., 2020). Still, despite theoretical and empirical advances, society faces an increased risk of severe, challenging dangers of such complexity that existing approaches are ill-equipped to address (Boin et al., 2018; Schweizer et al., 2022; Wolbers et al., 2021).

In the past few years, the field of occupational health psychology has looked to existing theory to explain how major societal disruptions like the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019) pandemic affect employees (e.g., Knight et al., 2023) and ask what organizations can do to best support employees during times of disaster and crisis (Sinclair et al., 2020). Researchers aiming to investigate and guide efforts to address this pandemic and anticipated future scenarios are still trying to best conceptualize its unique dynamics and unfolding effects on employee well-being. While evidence is clear that employees feel anxious and emotionally exhausted during times of major disasters and crises (e.g., Naushad et al., 2019; Podubinski & Glenister, 2021), our understanding of why or through what mechanisms disasters and crises lead to strain outcomes is just beginning to emerge and requires more attention (Trougakos et al., 2020; Yoon et al., 2021).

In this paper, we build on prior work examining disaster characteristics and psychological effects to argue that our understanding of employee strain in times of disaster can be better understood by considering the backdrop of severe uncertainty, which we define as a particular type of uncertainty (i.e., incomplete or absent awareness or understanding) that (1) prevents us from predicting the likelihood of specific stressors or threats occurring (Comes et al., 2013) and (2) cannot be easily reduced due complex variability existing in relevant human behavior, macro-level dynamics (i.e., social, economic, and cultural processes), and the nature of the disaster or crisis itself (Sword-Daniels et al., 2018; Walker et al., 2003). First, we adopt the Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress (GUTS; Brosschot et al., 2016, 2017, 2018) to explain how industry-level economic (e.g., unemployment rate) and health (e.g., proximity to people and disease) unsafety signals contribute to employee anxiety and emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than maintaining that strain is triggered by exposure to a specific stressor, GUTS posits that the stress response is our default state when faced with general contexts of uncertainty—a state that must be inhibited (by the perception of sufficient environmental safety signals) to prevent strain. Emotional exhaustion, a key component of burnout, reflects a feeling of depletion following chronic stress and hypervigilance (Schaufeli et al., 2009; Thoroughgood et al., 2020).

Specifically, we apply GUTS to explain that, in the context of macro conditions of severe uncertainty caused by COVID-19, employees are more likely to experience anxiety (a negative affective reaction to uncertainty; Grupe & Nitschke, 2013) as a result of industry unsafety signals, which, in turn, contributes to emotional exhaustion. Given the most prominent macro conditions that existed at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic were economic uncertainty (Godinić & Obrenovic, 2020), and health uncertainty (Trougakos et al., 2020), we examine whether economic and health anxieties explain how macro level economic and health unsafety signals, respectively, produce employee emotional exhaustion.

In doing so, we draw from disaster management literature (e.g., Boin, 2019) to describe the characteristics of transboundary disaster and crisis situations that may make people particularly attuned to these industry-level safety signals and more likely to experience anxiety and emotional exhaustion. We posit that understanding the impact of the pandemic requires a deeper consideration of increasingly vulnerable industries and the employees that make up these professions (e.g., teachers, nurses, restaurant staff). Although the experience of dealing with disasters and crises is not new for organizations or organizational scholars (Wolbers et al., 2021), and there have been many advances in our understanding of how organizations and individuals have responded to the pandemic (e.g., Shoss et al., 2021), more insight is needed into potential sources of anxiety and emotional exhaustion during this time.

Overall, we integrate interdisciplinary approaches to present a model of employee well-being in times of disaster characterized by severe uncertainty. To illustrate and test these theoretical mechanisms, we analyze multi-source quantitative and qualitative data collected in two waves during the onset of COVID-19, an exemplar major disaster scenario (Schweizer et al., 2022). As a result, our study contributes to the occupational health literature in several ways. First, we address the gap in our understanding of contexts of occupational uncertainty caused by major disasters and crises, which is especially important as these types of disruptions are expected to increase in the future. Second, we integrate approaches from disaster management and neuroscience disciplines to extend occupational stress theory by describing how disasters affect employee well-being. To do so, we incorporate macro level predictors, addressing a long-standing criticism of stress theories: that they omit important organizational and societal effects on individuals by emphasizing the importance of individual stressor perceptions and minimizing environmental factors (Handy, 1988). Our research therefore provides important insights into how people perceive and respond to the macro-environmental context, which is important for bridging the gap between macro- and micro-organizational research (Hill et al., 2022) and represents an area of study to which our field should be dedicating more attention (Shoss & Foster, 2022).

Further, by examining dual economic and health unsafety paths in predicting employee strain, we adopt recent framing of economic and health areas of pandemic disruption (e.g.,Roccato et al., 2020; Shoss et al., 2021) and expand this approach by seeking to better understand whether salient economic and health unsafety signals relate to emotional exhaustion. Given the severe uncertainty that COVID-19 has produced across financial and health institutions, employees have had to simultaneously deal with both financial and health concerns. Yet, research has yet to confirm whether one source of unsafety is likely to be more important than the other in terms of predicting employee exhaustion. Our study applies GUTS to examine whether economic or health unsafety signals are more likely to relate to employee anxiety early in the pandemic. Finally, from a practical perspective, our research links employee concerns surrounding issues like health and safety in the face of an ongoing and changing pandemic to the experience of emotional exhaustion, which has dominated news reports and raised concerns about workforce well-being (Chen & Smith, 2021).

Theoretical Background

The recently proposed Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress (GUTS; Brosschot et al., 2016, 2017, 2018) offers an explanation that is well-suited to address macro-level causes of employee anxiety and exhaustion given the nuances of the COVID-19 pandemic. In their articulation of GUTS, Brosschot and colleagues posit that stress is a default human response in contexts marked by uncertainty. Specifically, the stress response involves, cognitive, attentional, affective, physiological, and behavioral changes also known “as the sympatho-excitatory response or fight-or-flight response” (Verkuil et al., 2010, p. 91). Rather than something that is triggered by the presence of stressors, the stress response is a default state that can only be inhibited (i.e., “switched off”) when a person perceives sufficient signals of safety from their environment (Brosschot et al., 2016). Notably, safety is defined as the perception of one’s chances of survival, which results from “a process of neurovisceral integration of information from the body’s state and the environment” (Brosschot et al., 2018, p. 8). Safety perceptions are context-specific and vary across individuals but result from similar underlying processes.

Accordingly, GUTS explains that anxiety can arise in the absence of a concrete or tangible stressor: “[S]tressors are not necessary for the stress response to be released: a lack of information about safety is sufficient. With no such information, generalized unsafety is assumed by the brain, and the default stress response is disinhibited” (Brosschot et al., 2018, p. 3). Indeed, definitions of anxiety present it as a direct response to uncertainty (Grupe & Nitschke, 2013). As a result, a general perception that one’s environment is unsafe can disinhibit a stress response over weeks or longer, contributing to the development of chronic stress as indicated by outcomes such as emotional exhaustion (Bridgland et al., 2021; Schaufeli et al., 2009).

Severe uncertainty produced during disasters and crises often leads to a cascade of compromised contexts, or situations in which individuals likely feel unsafe because of a lack of safety signals (Brosschot et al., 2018). Unfamiliar physical environments, chronic work stress, and financial problems constitute common, salient examples of compromised contexts. According to GUTS, people operating within compromised contexts are likely to experience chronic disinhibition of the stress response which manifests as anxiety. This is because severe uncertainty makes it difficult for individuals to engage in the sensemaking process necessary for stressor appraisal and coping (Christianson & Barton, 2021; Weick et al., 2005). The resulting anxiety involves a constant scanning of the environment for potential threat, which essentially traps one in a pre-primary appraisal stage of sustained vigilance, or an ongoing state of being on high alert (Grupe & Nitschke, 2013). In other words, unless safety signals are perceived, the stress response will not be inhibited; and, unless a clear threat is identified to initiate primary appraisal of the stressor, one cannot transition into secondary appraisal or coping (Brosschot et al., 2017).

Sustained vigilance resulting from the disinhibition of the stress response (which results from environmental uncertainty making it difficult to perceive safety signals) involves both a physiological response (i.e., sympathetic arousal of the autonomic nervous system) and psychological response (i.e., anxiety). Anxiety is an anticipatory (i.e., future-oriented) negative affective reaction to uncertainty and is characterized by concerns over the inability to perceive a positive outcome regarding one’s safety and well-being (Grupe & Nitschke, 2013). This sustained vigilance, manifesting as anxiety, is emotionally taxing. Therefore, according to GUTS, the disinhibition of the stress response in times of severe uncertainty leads to emotional exhaustion because of the anxiety triggered by environmental unsafety.

With GUTS as the theoretical framework used to explain how characteristics of disasters and crises are likely to lead to employee strain, we now describe the features of disaster and crises that are likely to produce this severe uncertainty. In particular, we draw from the disaster management literature to describe how the COVID-19 pandemic shares the features of a transboundary disaster. This novel approach to describing disasters that defy traditional definitions provides an effective lens for understanding how COVID-19 has induced severe uncertainty at a macro level that can influence individual employee well-being.

GUTS, Transboundary Disasters, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

A transboundary disaster lens accounts for the nature of COVID-19 disruption as a catalyst for unprecedented levels of uncertainty across multiple domains of life, which is likely to increase environmental scanning. An emerging line of inquiry has identified transboundary threats as new forms of disaster and crisis scenarios that pose unique difficulties in their mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery and produce conditions of persistent, severe uncertainty (Quarantelli et al., 2018). The transboundary threat construct has garnered agreement around a set of main characteristics (transcendence of geopolitical boundaries; high speed of spread via interconnected, unclear events; varied, ambiguous impacts across multiple levels; and necessity of coordination of complex response efforts) that produce uncertainty to a greater degree than previous forms of disasters and crises (Christianson & Barton, 2021; Schweizer et al., 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic has been defined as a transboundary threat that creates a backdrop of severe uncertainty for organizations and employees (Bryce et al., 2020) because of the ways in which its characteristics depart from those of traditional disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornadoes). Compared to COVID-19, traditional disasters are bound by time and location: individuals and organizations know within days or weeks from an initial identification of a hazard whether they will be directly impacted (Kreps, 1995). Many natural disasters are traditionally defined as time-bound events in the sense that there is a finite period of time in which the disaster and its effects begin and end (Hsu, 2019). For example, during hurricanes, even if we are not entirely sure where the hurricane will make landfall, we do know a general range of windspeeds and storm surge to expect, a length of time to expect impacts, and geographic locations that will versus will not be impacted. We have a specific list of actions to take to prepare and respond, and we know what resources and supplies will be necessary. Within a matter of days, the predicted area of impact is refined, “to reflect a more certain path of the upcoming storm” (Broos et al., 2022, p.4). Given the location and time-bound nature of traditional disasters (e.g., hurricanes, chemical explosions, epidemics; Shaluf, 2007), individuals are able to move rather quickly from an uncertainty phase, in which they may not be fully aware of total direct impacts, to a recovery phase, in which uncertainty is reduced and targeted plans can be made to recover (Quarantelli, 1985).

Severe uncertainty, on the other hand, is characterized by an inability to predict a time frame for when the uncertainty can or will be resolved (Schweizer et al., 2022). COVID-19 bears all the hallmarks of a transboundary disaster: in early 2020, we knew that there was something out there, but we didn’t know when it might come to our geographic location, where it might come from, who would be directly or indirectly impacted, how long it would last, or how to respond to it. COVID-19 crossed geographic, political, and functional boundaries (Allain-Dupre et al., 2020), leading to massive disruptions, including unprecedented supply chain disruptions (Schmalz, 2020), and job loss in previously flourishing industries (e.g., tourism; U.S. Travel Association, 2020). Table 1 provides further evidence of the characteristics of COVID-19 that support its transboundary disaster classification and contribute to severe uncertainty.

Table 1.

Features of COVID-19 as a transboundary disaster contributing to severe uncertainty

| Transboundary disaster criteria | COVID-19 examples |

|---|---|

| 1. Threat jumps international, national/political governmental, and functional (sector to sector) boundaries | “To make matters worse, restrictions on international travel, imposed to prevent the spread of the virus, have impacted on shipping and logistics activities, meaning that even when PPE was available it could not be delivered (Edgecliffe-Johnson, 2020; Peel, 2020)” (Bryce et al., 2020, p. 883) |

| “Moreover, the effects go far beyond those felt by healthcare systems; they stretch across virtually every sector of society—from food systems to education—and have debilitated economies” (Weible et al., 2020, p. 226) | |

| “The effectiveness of the COVID-19 response depended to a significant degree on the prolongation of imposed lockdown measures. The longer these were maintained, the more likely an effective response in terms of reducing patient numbers. But that same effectiveness fed a sense of impatience among citizens and business owners” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 197) | |

| 2. Spreads very quickly accompanied by global awareness of risk due to mass media attention | “The COVID-19 crisis gave rise to an army of amateur virologists and intense public discussion. Looking to the crisis regimes of other countries, public discussions would soon revolve around the question ‘why don’t we do that?’” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 197) |

| “In many ways, national responses to COVID-19 were shaped by international context, whether it was alarm at TV images from Italy, geopolitical posturing between the US President and China, or the way in which national populations adjusted their behavior in view of policy responses elsewhere (such as parents withdrawing their children from school)” (Boin et al., 2020, pp. 199–200) | |

| 3. No known central or clear point of origin initially; possible negative effects are unclear; more pervasive ambiguity than in traditional disasters because information about causes, characteristics, consequences is distributed across the global system | “Little was, initially, known about the virus, its paths of transmission and its health impact” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 190) |

| “A key gap in our knowledge of SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission is the role of animals, and despite a consensus that this virus arose from an animal reservoir, a fundamental and intriguing question is which species?” (Ward, 2020, p. 1) | |

| “The Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, neatly summarized the challenge when he observed that he had to make 100% of the decisions with less than 50% of the required information. Political leaders and policymakers everywhere had to cope with this condition of deep uncertainty (Capano et al., 2020)” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 190) | |

| “The more doctors and researchers learned about the virus, the more perplexed they became (see e.g. Cookson, 2020)” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 191) | |

| 4. Large number of potential and actual victims both directly and indirectly; differs from traditional disasters because # victims is open-ended due to disruptions spanning boundaries | “Initial fatality data suggested that the lives of relatively small groups of people (the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions) depended on the behavior of all others (DW, 2020a; BBC, 2020d)” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 195) |

| “Older adults and those with pre-existing conditions (e.g., asthma) are at higher risk for the more severe impacts. However, everyone is susceptible, and anyone can contract and spread the disease” (Weible et al., 2020, p. 226) | |

| 5. Traditional/existing response solutions & approaches may not always work; requires international organizational involvement early on as opposed to the norm of starting with local planning & management | “Standard advice (see World Health Organization Writing Group, 2006) regarding how to manage pandemics was soon proven insufficient. Policymakers were pressed into taking measures that, in the context of western liberal democracies at least, were seen as both unimaginable and infeasible (such as extensive lockdowns as initially imposed in Wuhan)” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 190) |

| “Most governments found themselves ill-prepared to deal with the COVID-19 crisis” (Boin et al., 2020, p. 193) | |

| 6. Greater degree of emergent response behavior and short-lived informal linkages across groups that may not have coordinated previously; informal social networks form to exchange information but are hard to identify | “International collaboration flourished in response to COVID-19, channeled through the epistemic community of epidemiologists, virologists, and pharmacologists. Such collaboration is enabled by a global network of state agencies, private interests, and international institutions in efforts to coordinate public information activities and global research priorities (Mesfin, 2020). In this transboundary crisis, countries exchange data and experiences to learn about the virus and its effects” (Weible et al., 2020, pp. 228–229) |

The severe uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic limits the ability of organizations and individuals to successfully engage in sense-making processes that Boin (2019) explains are necessary to avoid exhaustion. Indeed, responses to COVID-19 have faced complex challenges, resulting in a high variability in policy effectiveness across nations and general uncertainty about what should be done (Fakhruddin et al., 2020). According to Murugan et al. (2020), surging infection rates, inability of prediction models to accurately project disease transmission, complexities of the disease itself, and variability of global responses make it especially challenging for organizations to initiate informed action. Not surprisingly, emerging research points to a detrimental effect of COVID-19 on indicators of employee and population well-being (Zacher & Rudolph, 2020).

COVID-19 Disruption and Severe Uncertainty at the Macro Level

One defining feature of COVID-19 as a transboundary disaster is the way in which it creates compromised contexts (i.e., environments and situations lacking safety signals; Brosschot et al., 2018) at a societal level, creating shifts in our fundamental understanding of the world around us (Howe et al., 2021). Because transboundary disasters like COVID-19 often illuminate or activate previously hidden or dormant societal vulnerabilities, the effects of transboundary disasters often emerge with an accompanying paradigm shift. Paradigm shifts are psychologically uncomfortable and disruptive, partially because a change in understanding the world around us may force us to discard environmental cues that we had previously accepted as safety signals (Robinson et al., 2021). Our environment becomes compromised, uncertain, and potentially unsafe. In the case of COVID-19, this paradigm shift involves discarding held safety assumptions that it is safe to go to work and be in public with strangers whose health behavior you know nothing about; that occupations within service industries such as healthcare, education, and hospitality enjoy economic security and stability (Howe et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2021).

What happens when a fundamental societal shift occurs in our perception of workplace safety? Because individuals are driven to seek information to evaluate their own safety (Rahmi et al., 2019), they look to signals from their environment in an attempt to reduce uncertainty (Sirola & Pitesa, 2017). It’s likely that individuals looked both within and outside of the workplace in an attempt to gather more information and reduce the severe uncertainty caused by COVID-19. However, industries and organizations were widely unprepared to face COVID-19 (Rouleau et al., 2021), and organizations within specific industries were largely making plans by copying other organizations within that industry, making it harder to convey safety signals to the workforce. Indeed, a Gallup survey early in the pandemic found that employee worry was at its highest point since the 2008 financial crisis (Reinhart, 2020), indicating that organizations may have struggled to reduce perceptions of uncertainty and unsafety. Further, the economic precarity induced by the COVID-19 pandemic increased unemployment and decreased wage growth across industries at different rates (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). Therefore, we would anticipate that employees were likely exposed to, and therefore perceived, different levels of economic and health-related unsafety depending on their industry (Bryce et al., 2020).

Evidence suggests that individuals also relied heavily on the news to gather more information—which appears to have been in greater supply from these outlets than from organizations. Indeed, at the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak, Americans were inundated with COVID-19 news. However, gathering more information does not always mean that uncertainty will be reduced (Walker et al., 2003); in some cases, employee news consumption can even exacerbate uncertainty (Yoon et al., 2021). As the average number of daily news stories published per major media outlet reached approximately 80 by the middle of March 2020, individuals found the coverage “overwhelming and difficult to follow” (Head et al., 2020, p. 1).

Taken together, evidence pertaining to COVID-19 disruption and uncertainty suggests that the features of the pandemic that qualify it as a transboundary disaster have contributed to major disruptions at a societal level that create severe uncertainty. The virus trajectory involved rapid escalation in infection rates over time (The New York Times, 2021), and its economic and health-related impacts have been hard to characterize (Chater, 2020). Boin et al. (2020) described it: “In most crises, uncertainties are quickly reduced through established methods of information collection and analysis…The COVID-19 crisis was unique as it kept generating new uncertainties” (p. 191). As a result, employees were exposed to new economic and health-related signals of unsafety (Hameleers & Boukes, 2021; Roccato et al., 2020; Shoss et al., 2021).

This severe uncertainty may have made it challenging for individuals to perceive safety signals at work. Yet, even as there was uncertainty regarding what, exactly, the effects of COVID-19 might be for employees, one message seemed to be repeated over and over. An analysis of 532 images from 125,696 news articles in top COVID-19 media outlets found that most of the images depicted workplace settings and conveyed the emotion of fear (Head et al., 2020). Industries and workplaces in the context of the pandemic have been consistently conveyed as generally unsafe.

Hypothesized Model

Building from this theoretical perspective, we investigate transboundary disaster-induced unsafety signals that emerge at the industry level and lead to employee anxiety: industry economic unsafety and industry health unsafety. We focus on these two unsafety signals because they are the direct result of the two greatest impacts of the pandemic identified so far—disruptions to human health and disruptions to the economy, both on a global scale (Chakraborty & Maity, 2020). This focus on economic and health unsafety aligns with previous COVID-19 research (Roccato et al., 2020; Shoss et al., 2021) emphasizing the two most salient mechanisms through which COVID-19 unsafety is likely to affect employee emotional exhaustion.

Drawing from GUTS, it’s likely that industry-level signals of unsafety described above contributed to employee anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic (Brosschot et al., 2016). More specifically, when faced with unsafety signals related to economic well-being during COVID-19, employees are likely to experience economic anxiety; similarly, employees are likely to experience health anxiety when faced with COVID-19 health unsafety signals. This is because COVID-19 created a context of severe uncertainty (Boin et al., 2020), and anxiety is the natural human response to the experience of uncertainty (Brosschot et al., 2016; Grupe & Nitschke, 2013; Hur et al., 2020). The neuroscience literature explains that this serves an evolutionary, adaptive function. According to Grupe and Nitschke (2013), “Uncertainty diminishes how efficiently and effectively we can prepare for the future and thus contributes to anxiety” (p. 488). Grupe and Nitschke also conceptualize anxiety as a state of vigilance in which we scan the environment for information that can be used to identify and address danger or threats. This anxiety, although useful in helping to prepare for potential danger, is psychologically and physiologically taxing and can lead to emotional exhaustion (Fu et al., 2021; McCarthy et al., 2016). In sum, COVID-19-disrupted work environments are contexts characterized by signals of economic and health unsafety that likely translate to anxiety and exhaustion.

Economic Unsafety Path

One path through which transboundary disasters, such as the pandemic, influence employee strain is the economic unsafety path. The economic precarity induced by the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact across almost all industries (evidenced by unemployment rates and decreased wage growth); however, some were hit harder than others (e.g., hospitality/tourism; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). According to GUTS (Brosschot et al., 2017), this industry-level signal is likely to induce anxiety regarding the future of employees’ organizations as they navigate increased uncertainty in a continuously changing economic landscape. Employees who feel that their industry and therefore own organization might be at risk for negative economic consequences may also feel like their organization is unstable (Giorgi et al., 2015). According to GUTS, COVID-19 unemployment rates (compared to rates prior to the start of the pandemic) represent the elimination of a previously existing economic safety signal, and that absence of safety (i.e., unsafety signal) characterizes industries as compromised contexts. Within a compromised context of an industry facing economic uncertainty, employee stress responses are likely to be disinhibited (Brosschot et al., 2018). GUTS argumentation further suggests that employees experiencing this stress response would continue scanning their unsafe environments (i.e., their industry) for information, leading them to experience economic anxiety that is emotionally tiresome. There is initial evidence that employees fearful of the negative impacts of COVID-19 on their employment are more likely to experience emotional exhaustion (Chen & Eyoun, 2021). As a result, industry signals of generalized economic unsafety are likely to lead to employees experiencing anxiety over economic concerns that develops into psychological strain (Brosschot et al., 2018).

Hypothesis 1: Industry economic unsafety signals will be positively related to employee COVID-19 economic anxiety.

Hypothesis 2: Industry economic unsafety will be indirectly and positively related to employee emotional exhaustion via COVID-19 economic anxiety.

Health Unsafety Path

The current pandemic has posed the most significant health concerns to Americans since the AIDS epidemic (Hrynowski, 2020; Jones, 2020). Depending on the nature of one’s employment (e.g., healthcare, food services, entertainment), workers may have faced an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 due to factors such as repeated proximity to the public and direct exposure to individuals who have tested positive for the virus (Kniffin et al., 2021). According to GUTS (Brosschot et al., 2018), this potentially increased risk represents the elimination of a health-related industry-level safety signal that had previously helped to inhibit the stress response prior to the pandemic, and it is a characteristic of industries as compromised contexts. Similar to the logic described above, this industry-level signaling of health unsafety is likely to induce anxiety regarding employee health. COVID-19 is highly transmissible and can manifest in a wide variety of symptoms (Ra et al., 2021); no COVID-19 protocol can truly ensure that someone will absolutely avoid contracting the virus. Evidence from studies of COVID-19 transmission and disease progression indicate that, compared to other viruses like the seasonal flu, COVID-19 has more variability in its incubation period, more variability in symptoms present and whether symptoms will occur, a larger window of contagion in which there may also be asymptomatic transmission, and the presence of long-term effects (CDC, 2022). According to GUTS (Brosschot et al., 2017), lack of clear information on what exactly one can do to avoid, mitigate, or cope with the threat creates an environment of unsafety that is likely to contribute to increased employee COVID-19 health anxiety. This health anxiety disinhibits the stress response, contributing to employee strain.

Hypothesis 3: Industry health unsafety signals will be positively related to employee COVID-19 health anxiety.

Hypothesis 4: Industry health unsafety will be indirectly and positively related to employee emotional exhaustion via COVID-19 health anxiety.

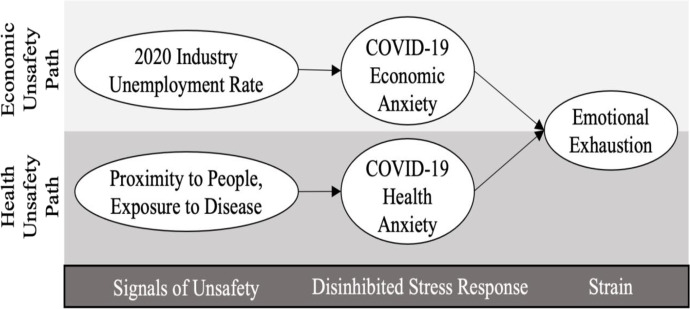

In sum, we argue that industry-level unsafety signals represent the initial catalysts of the psychological process through which severe uncertainty influences employee well-being. Therefore, we take a deductive approach to propose a conceptual model (Fig. 1) informed by GUTS to characterize the employee experience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Proposed model of COVID-19 workplace GUTS

Research Question

While GUTS can explain the general mechanism through which severe uncertainty triggered by a transboundary disaster influences employee well-being, there is one additional nuance to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic that existing theory may not be able to explain well enough to support a formal hypothesis. A great deal of discussion and political activity has been generated around the question of whether it is more important for organizations to address the pandemic’s health-related or economic disruptions, which often appear to involve mutually exclusive strategies (Leibenluft & Olinsky, 2020). Addressing health-related unsafety may involve making changes to business operations (e.g., closures, reducing in-person staff) that create or exacerbate a sense of economic unsafety (e.g., job insecurity). On the other hand, addressing economic unsafety likely involves facilitating business operations in a way that may create or exacerbate a sense of health-related unsafety (e.g., risk of exposure due to avoiding closures). Early in the pandemic, it was unclear which of these concerns should have been prioritized. The vast variability in health vs. economic decisions made within organizations across the world (i.e., the timeline of shutdowns and reopenings) reflect this uncertainty. As a result, and to gain additional insight into this phenomenon, we pose a research question regarding the types of unsafety triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and employee well-being.

Research Question: Which unsafety path (health or economic) will better predict employee emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data for this study came from objective industry indicators as well as employee responses to surveys administered across two time points separated by approximately 2 weeks. This time lag is supported by previous methods guidance advocating time lags much shorter than the 6-month standard in longitudinal research (e.g.,Dormann & Griffin, 2015; Ford et al., 2014) and recent COVID-19-related studies of employee well-being (e.g., Fu et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021; Vaziri et al., 2020). All measures were administered at both time points. Moreover, due to recent calls to study transboundary disasters using multiple methods (Wolbers et al., 2021), the survey included both a quantitative and qualitative data collection component.

We leveraged several recruitment strategies to reach our study sample size. First, employed adults enrolled at a large Southeastern university in the United States were recruited. Additionally, snowball sampling was utilized to reach potential participants through several social media outlets. Our data were collected during the first peak of the U.S. pandemic outbreak and stay-at-home orders, March 2020 through July 2020 (Kates et al., 2020). A total of 212 participants were recruited for this study and 76 participants responded to both time 1 and 2 surveys.

Because of the large dropout, we analyze our study hypotheses using both the cross-sectional and time lagged data. Despite this attrition rate, previous Monte Carlo studies have shown value in time-lagged studies with substantial attrition rates for examining relationships between risk factors and well-being (Gustavson et al., 2012), and our examination of both cross-sectional and time-lagged data—as well as the incorporation of objective industry-level statistics— helps provide greater confidence in the results. Furthermore, we found there were no significant differences in emotional exhaustion between participants who dropped out (M = 3.54, SE = 0.12) and those remained in the study (M = 3.41, SE = 0.15), F(1, 184) = 0.75, p = 0.389, providing additional confidence in our final results.

The mean age for our final sample was 33.43 (SD = 15.31) and was composed of majority female participants (64%). Furthermore, most participants were White (63%), with 33% of the sample indicating earning over $100,000 per year. Regarding industry breakdown, approximately a quarter of our sample worked in healthcare (23.5%) and food services (24.4%), with the next highest representation in retail (14.5%), then education (12%). The remainder of our sample was distributed among different industries (e.g., hospitality, aviation, finance). The average working hours for participants was 34.64 h per week, with about 74% of our sample being workers also enrolled in college courses while the other 26% were non-student workers.

Measures

Industry-level Unsafety Signals

Objective industry data from archival sources were used to measure unsafety signals indicating industry-level disruption caused by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Because the stress response is largely unconscious (Brosschot et al., 2018), it is more appropriate to measure conditions of the compromised context than self-reported perceptions of safety or unsafety. In fact, GUTS posits that self-report is likely unable to capture the extent to which a compromised context disinhibits the stress response. Additionally, objective, secondary data can help to better triangulate phenomena of interest when paired with data from primary sources for occupational health and well-being research—especially when there is an interest in examining conditions for a population of interest that existed prior to the time at which survey data were collected (Fisher & Barnes-Farrell, 2013). Using objective indicators of phenomena of interest can also enhance generalizability of results, which, in addition to minimizing common method bias, carries a benefit over self-report data of the same phenomena (Fisher & Barnes-Farrell, 2013).

We included two forms of industry unsafety signals: economic and health unsafety. First, we used the 2020 US industry level unemployment rate, while controlling for the 2019 industry level unemployment rate, to capture economic unsafety signals during the early COVID-19 pandemic months. Specifically, a 3-month average from March 2019 through May 2019 as well as from March 2020 through May 2020 was calculated for economic unsafety. By matching participants self-reported industry with industries listed in the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we were able to assign each participant with their respective economic unsafety score (i.e., industry level unemployment).

Second, health unsafety was measured by aggregating two objective measures collected from the Occupation Information Network (O*NET): physical proximity to people (O*NET, 2021b) and exposure to disease (O*NET, 2021a). These two sources of O*NET data were selected because they represent separate rating variables of work context that, when combined, operationalize the health-related unsafety signal created by COVID-19 disruption and severe uncertainty described above: that it is no longer safe to be around other people at work. Both measures use a scale ranging from 0 to 100, and each occupational code is assigned a single score. For physical proximity, scores indicate degree of closeness to others (0 = “I don't work near other people [beyond 100 ft.]”; 50 = “Slightly close [e.g., shared office]”; 100 = “Very close [near touching]”) in response to the question, “To what extent does this job require the worker to perform job tasks in close physical proximity to other people?” (O*NET, 2021b, para. 1). Exposure to disease uses a frequency score, with 0 = “Never”; 50 = “Once a month or more but not every week”; 100 = “Every day”; in response to the question, “How often does this job require exposure to disease/infections?” (O*NET, 2021a, para. 1). An average aggregate score representing total health unsafety was created from these two objective measures. Similar to the economic unsafety data matching process, participants’ self-reported work roles were successfully mapped to O*NET job roles, allowing for each respondent to be assigned a corresponding aggregate health unsafety score.

COVID-19 economic anxiety was captured using the five-item fear of economic crisis scale (Giorgi et al., 2015); an example item is “I am scared that my organization is affected by the economic crisis” (Cronbach’s α = 0.88).

COVID-19 health anxiety was assessed with virus outbreak worry items from Wu et al. (2009) were used to capture (4 items; e.g., “I believe my job is putting me at great risk for exposure to coronavirus”; α = 0.76).

Emotional exhaustion was assessed with the English translation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Halbesleben & Demerouti, 2005) (4 items; e.g., “During my work, I often feel emotionally drained”; α = 0.83). All response options were on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Open-ended Question

In addition to the scales described below, participants were invited to respond to one open-ended question, “Is there anything else you wish to tell us about your workplace's response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak and how you are feeling in response to their actions or inactions?” This question was included to elicit comments that might pertain to economic and health anxieties, experiences that seemed to indicate a sense of safety versus unsafety, as well as positively or negatively valanced narratives, generally. Wording was intentionally neutral to avoid priming participants regarding positive or negative experiences. The intent was to allow them to include any salient experiences (positive or negative) they believed to be worthy of mention while still grounding the content as work relevant.

Analytic Approach

Quantitative

For quantitative data, we first performed a confirmatory factor analysis using maximum likelihood with robust standard errors to compare our proposed measurement model with alternative models using the Satorra-Bentler Scaled Chi-Square test. We tested our proposed three latent factors measurement model against a single factor model. Additionally, we compared our proposed structural model against two alternative structural models to further increase support of our conceptual model.

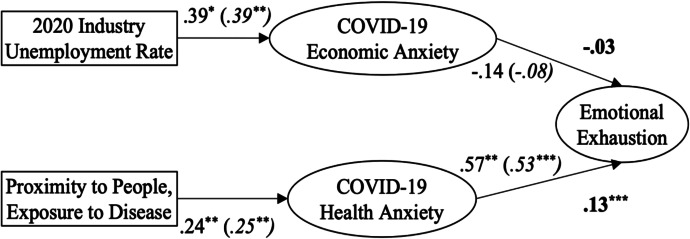

This was followed by formal hypothesis testing using maximum likelihood estimation and 1000 bootstrap draws to examine structural paths and indirect effects using Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). We then conducted a final set of SEM analyses to test the robustness of the hypothesized paths with the full time 1 sample size of 212 respondents. These results were consistent with the model results using both the Time 1 and Time 2 data (see notes in Fig. 2). Below, we present results from analyses using Time 2 emotional exhaustion. Based on Preacher and Hayes (2008) recommendations, bias-corrected confidence intervals were examined to test the significance of indirect effects.

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model results. Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Bold values represent indirect effect coefficients. Italicized values in parentheses represent beta coefficients using full time 1 sample. Fit indices for this model using full sample = χ2 = 927.96, CFI = .92, TLI = .87, RMSEA = .07 [.06, .09], SRMR = .07

As a robustness check, we considered included dummy-coded industry variables as controls. Our model results revealed no significant differences in path coefficients and indirect effects when this industry control variable was included. For parsimony, we report our results without the dummy-coded industry variables.

Qualitative

The use of qualitative data in this study is intended to promote triangulation, or the examination of a research phenomenon using more than one method, which can offer a more holistic view than might be possible using quantitative data alone (Jick, 1979) and is particularly useful in studying disasters (Phillips, 1997). We adopted a complimentary methodological approach in which qualitative data support a primarily quantitative study. Qualitative data in this study therefore “provide interpretive resources for understanding the results from the quantitative research” (Morgan, 1998, pp. 369–370; Bazeley, 2008). In this strategy, because our qualitative data are intended to enhance the understanding of quantitative data, we approach both types of data as being situated within the same theoretical framework (i.e., GUTS applied to COVID-19 as a transboundary disaster creating severe uncertainty) rather approaching the qualitative data as independent sources of socially constructed meaning. With this strategy and rationale, we found it most appropriate to use the coding reliability method of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2021).

Adhering to thematic analysis steps (Braun & Clarke, 2006), the first two authors became familiarized with the qualitative data; generated initial codes that were both consistent with the study’s theoretical framework and representative of the subjective nature of the narrative accounts; organized the codes into themes, reviewed the themes in comparison to the full set of data, defined the themes, and developed the resulting qualitative report. Specifically, open-ended responses to the single survey question at both time points were qualitatively analyzed for comments related to employee experiences and concerns following the health and economic unsafety pathways in the GUTS framework (refer to Fig. 1). After an initial interrater agreement of 86.7% for Time 1 comments and 86.11% for Time 2, a consensus-building meeting was held to review conflicting codes and arrive at consensus for all 143 open-ended responses.

This process yielded five codes nested within two themes: Salient Concern (economic and health anxiety) and Valence (positive, negative, and neutral). Salient concerns involved the content of the open-ended response as pertaining to employee perceptions of economic or health issues. Because participants were able to choose for themselves (a) whether to respond to the open-ended question and (b) whether to respond about positive or negative experiences (rather than being asked to produce an example of economic and/or health concerns), this theme is conceptualized as particularly salient issues present at the time of the survey. Valence involved the latent sentiment of the responses: positive (i.e., expressing positive sentiment about the content described) or negative (i.e., expressing negative sentiment about the content described).

Results

See Table 2 for descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables. The measurement model comparison results revealed our initial measurement model, which included three latent factors, was a better fitting model than a single factor model, where all latent indicators loaded onto a single latent factor. Full fit statistics for all measurement models are presented in Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

| Variable | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Industry health unsafety | 98.86 (41.58) | - | |||||

| 2. Industry economic unsafety | 14.47 (9.99) | -0.29*** | - | ||||

| 3. Pre-COVID industry unemployment | 3.57 (1.65) | -0.35*** | 0.89*** | - | |||

| 4. COVID-19 health anxiety | 2.93 (1.44) | 0.24*** | -0.07** | -0.09** | - | ||

| 5. COVID-19 economic anxiety | 3.25 (1.20) | 0.077** | -0.09 | -0.20** | 0.02* | - | |

| 6. Emotional exhaustion | 3.41 (0.89) | 0.15** | -0.05** | -0.08** | 0.58*** | 0.15 | - |

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Industry health unsafety represents the average aggregate score created from the O*NET variables of physical proximity to people and exposure to disease. Industry economic unsafety represents the average industry unemployment rate from March to May 2020, while the Pre-COVID unemployment rate is the average from March to May 2019

Table 3.

Measurement model fit statistics

| Model | Description | χ2 | df | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | Comparison | TRd | Δdf | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM1 | 3 latent factors | 60.63 | 41 | .025 | .968 | .957 | .046 [.017, .069] | .074 | ||||

| MM2 | 1 latent factor | 317.81 | 44 | < .001 | .556 | .446 | .165 [.148, .183] | .181 | MM1-MM2 | 176.35 | 3 | < .001 |

MM Measurement model. Best fitting model in italics

Structural Equation Modeling

Hypotheses 1 and 3 predicted a positive relationship between industry economic and health unsafety signals and corresponding employee COVID-19 economic and health anxiety, respectively. Both paths were significant in the expected direction (industry economic unsafety predicting employee COVID-19 economic anxiety b = 0.39, p = 0.008; industry health unsafety predicting employee COVID-19 health anxiety b = 0.243, p < 0.001), providing support for Hypotheses 1 and 3.

COVID-19 economic anxiety and health anxiety were modeled as parallel mediators of the relationship between industry unsafety and emotional exhaustion at Time 2 (see Fig. 2). The indirect effect of economic unsafety on emotional exhaustion through economic anxiety was not significant (b = 0.055, p = 0.309, 95% CI = -0.028, 0.206). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was not supported. In contrast, results indicated a significant indirect effect of health unsafety on emotional exhaustion through health anxiety COVID-19 exposure worry (b = 0.139, p = 0.003, 95% CI = 0.059, 0.251), providing support for Hypothesis 4. In terms of the research question, results of structural equation modeling indicate that the health unsafety path better predicts employee emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic in this sample.

Additionally, we formally compared our proposed structural model with various alternative structural models. We first tested our proposed structural model against a model in which direct effects were also modeled from both our exogenous variables (e.g., COVID-19 exposure risk and 2020 unemployment rate) to employee emotional exhaustion. Results from our Satorra-Bentler test revealed there were no significant differences between our proposed structural model and a direct effects model. We further tested our proposed structural model against a model in which our exogenous COVID-19 exposure risk variable was separated into two separate observed indicators (e.g., proximity and exposure to disease). Results from our Satorra-Bentler test revealed the difference between our proposed structural model and a separate indicators model was approaching significance. Taken together these results indicate that our proposed structural model was a good fitting model (Table 4). Although no significant differences were detected at the 0.05 level, 1) our proposed structural model is more parsimonious compared to the alternative structural models and 2) the difference between our proposed model and the separate indicators model did reveal moderately significant differences (p < 0.10).

Table 4.

Structural model fit statistics

| Model | χ2 | df | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | Comparison | TRd | Δdf | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM1 Proposed model | 161.41 | 72 | < .001 | .875 | .847 | .074 [.059, .089] | .111 | ||||

| SM2 Direct effects model | 159.99 | 69 | < .001 | .873 | .838 | .076 [.061, .092] | .112 | SM1-SM2 | 1.26 | 3 | .739 |

| SM3 Reversed mediators model | 171.44 | 72 | < .001 | .861 | .830 | .078 [.063, .093] | .116 |

Qualitative Results

To provide additional insight into our research question, a thematic analysis of open-ended survey responses was conducted (analytic approach described above). There were 107 responses from the first survey and 36 from the second survey. The average word count across participants for Time 1 responses was 45.17 words per participants (response minimum = 2 words; maximum = 322 words; median = 32 words), and 42.06 words per participants (response minimum = 3 words; maximum = 127 words; median = 32.5 words) for Time 2 responses. The prevalence of Salient Concern (health vs. economic focus) and Valence (positive vs. negative sentiment) are summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Valence and focus of qualitative responses

From the first survey, the majority of responses tended to be negative in valence (63.8% negative, 34.3% positive, and 1.9% neutral), indicating that participants were attending to negative cues in their environment that, according to the GUTS theoretical framework, could trigger feelings of unsafety. The focus on the responses indicated that participants were attending to the economic and health unsafety pathways in our application of GUTS (Fig. 1) in approximately equal frequencies (34.3% negative economic-focus and 31.4% negative health-focus); although, when responses focused on both health and safety concerns (N = 10), 60% expressed the salience of health concerns over economic concerns. Comments coded as negative and focused on economics tended to highlight the importance of organizational communication in creating or managing feelings of economic uncertainty, such as when one participant stated “Our department manager has not responded at all. One simple conference call or email to just say I am here for you, thank you for working harder with less staff or an acknowledgement of our fears and confusion would have gone a long way—especially [with] rumors that more lay-offs are coming.” Comments coded as negative and health-focused highlighted the importance of workplace policy, resources, and norms in creating and managing health-related uncertainty, such as when one participant stated “They have not done a lot to ensure our safety in the workplace. Temperatures are taken whenever they feel like it. Mask and gloves are only necessary when the general manager is there, besides that they are not worn properly.”

For the second survey, open-ended responses also tended to be negative in valence (61.11% negative, 36.11%, 2.78% neutral), once again highlighting the potential of environmental cues to trigger feelings of unsafety. The comments tended to be slightly more focused on the economic unsafety pathway of our application of GUTS theory, as 50.0% were coded as economic-focused and 41.67% health-focused. However, when comments referenced both health and economic concerns (N = 5), 80% expressed the salience of health concerns over economic issues. Comments coded as negative and economic in focus tended to focus on ongoing issues related to job stability, such as when one participant stated, “My company is planning on permanently laying off some associates who were placed on furlough due to COVID-19, as they do not believe that we will fully recover our lost revenues in 2020.” Comments coded as negative and health-focused highlighted the importance of workplace policy, but also indicated that employees can still perceive vulnerability even when policy is implemented well. For example, one participant stated “My workplace has split the staff into two teams. Each team works for two weeks and then self-quarantines for two weeks. I feel like my employers have been responsible and considerate. Any anxiety I experience comes from exposure to customers, and my employers have limited that exposure to the best of their ability.”

Overall, the qualitative data collected in this study highlight the continued relevance of both the health and economic unsafety pathways when a GUTS framework is applied to the COVID-19 pandemic. More illustrative quotes can be found in Table 5.

Table 5.

Illustrative quotes from qualitative analysis

| Code | Survey 1 responses | Survey 2 responses |

|---|---|---|

| + E |

• My job has allowed me to work from home for a few months now and I am very appreciative. Our business has not been drastically affected by the pandemic luckily • Workplace has kept us informed and everyone that can is working from home. They are also equipping those who traditionally do not work from home with equipment to do so. They could have been a few days earlier but they did eventually make the decision |

• The county is working vigorously on making things easier for teachers and parents since everything was quickly thrown out there • I have been full time at home since March 10th and while other people in my company have seen a huge drop-off in sales, I have had an increase… I am hopeful I will continue to produce and continue to demonstrate growth both personally and professionally |

| -E |

• My work place gave us little to no information, updated us barely through email, and then finally told us we were closing, nothing else unless you called with questions • Our department manager has not responded at all. One simple conference call or email to just say I am here for you, thank you for working harder with less staff or an acknowledgement of our fears and confusion would have gone a long way—especially [with] rumors that more lay offs are coming |

• We have been closed since the beginning and have no word on when we will be reopening • My company is planning on permanently laying off some associates who were placed on furlough due to COVID-19, as they do not believe that we will fully recover our lost revenues in 2020 |

| + H |

• They have closed down the county service building to the public, thereby drastically reducing the number of people that come in and out of the building…That drastically cuts down face-to-face interactions. I was given PPE training through a digital format and the necessary equipment to keep my workspace sanitized and clean • They have been very good with following guidelines and ensuring everyone's safety, including the residents as many are elderly and would not survive the virus. Have provided us with PPE and make sure we…are never within 6 feet of residents |

• I am actually impressed with the PPE that has been provided daily for each employee. I also think [organization] has done a great job regarding keeping employees informed, as well • I had a sore throat and cough and was happy that my employer let me work from home for a few days until I was cleared to come back. I received a coronavirus test the first day I was absent from work • We do have to sign mandatory questions on how we are feeling and if we have come in contact with anyone who has COVID-19. If we say that we have then we go home, no repercussions |

| -H |

• They have not done a lot to ensure our safety in the workplace. Temperatures are taken whenever they feel like it. Mask and gloves are only necessary when the general manager is there, besides that they are not worn properly • I constantly worry that I am taking the virus home with me. I always practice proper PPE, but still feel that I am at a higher risk of getting the virus. A lot of my co-workers do not wear their masks properly and they do not care about COVID-19… |

• I have been able to come back to work and have been working for around a month now, but I feel very exposed • My workplace has split the staff into two teams. Each team works for two weeks and then self quarantines for two weeks. I feel like my employers have been responsible and considerate. Any anxiety I experience comes from exposure to customers, and my employers have limited that exposure to the best of their ability |

| H > E |

• My location probably should have closed when a lot of restaurants closed due to the lock-down… now we are fully back in business, but I still feel concerned of getting it while working • My company has responded almost immediately, even though financially crippling, to the outbreak. All our parks, resorts, stores and even movie productions have closed and halted because of it… yet they have kept nearly all of us…employed and paid (even if not currently working) through it |

• I feel that I have been blessed to still have my job since so many of my coworkers have been furloughed. It still scares me a little that we may be moving too hastily in getting back into our normal routine • Since I am graduating soon with a degree in healthcare, I am not terribly worried. However, I am mostly worried about my fiancé who is a heart surgeon and is with COVID patients daily. I worry about him contracting the disease… I worry that my family may unknowingly spread the disease to others |

| E > H |

• I am slightly afraid of contracting COVID-19 due to my workplace still requiring me to come to work in order to get paid. However, I'm more afraid of not being able to get a paycheck • [Organization] is offering parents/people…some amazing options to make sure that they can hire caregivers during this time. However… I feel pressured to encourage my daughter's daycare to stay open so that I can continue working |

• I feel pretty safe other than losing work and layoffs • So ready for this to end. The longer it goes on the more hysterical people get. We have to learn to live with this virus • A lot of my semi-negative emotion was because I think our government has over reacted and overshot what we should have done… I am more anxious we are economically hurting our hospitals and business and the models were too high in deaths, hospitalizations |

+ Positive;—Negative; E Economic; H Health; H > E Health concern more salient than economic concern; E > H Economic concern more salient than health concern

Discussion

This study explores the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic as a transboundary disaster and its subsequent implications for employee well-being. Leveraging both quantitative and qualitative approaches, our results suggest that employees attend to industry-level unsafety signals related to both health and the economy. These unsafety cues are associated with stress responses in the form of COVID-19 anxiety. This anxiety is related to higher levels of employee emotional exhaustion a few weeks later. These findings, informed by GUTS (Brosschot et al., 2017, 2018), help identify psychological mechanisms through which transboundary threats—and their ensuing severe uncertainty at macro-levels—influence employees.

The results of this study serve to not only advance the field of occupational health but also our understanding of employee well-being during severe uncertainty and the effects of transboundary threats such as the COVID-19 pandemic on employee well-being. Prior to COVID-19, limited research had been conducted on disruptive contexts generally, and none existed on public health disasters (Hällgren et al., 2018), let alone transboundary disasters. Although we have learned a great deal about the nature of COVID-19, helping to address the severe uncertainty faced in the year 2020, much remains unknown. Given that 1 in 4 US workers still believe COVID-19 is a salient health stressor (Saad, 2022), and economic uncertainty continues to loom at a global scale (Chiarelli & Kininmonth, 2022), the findings of our study remain relevant today—as we approach the three-year mark from the onset of the pandemic.

Theoretical Implications

In this study, we drew from the transboundary disaster literature to establish that the COVID-19 pandemic, by definition, is characterized by a context of severe uncertainty. Once this was established, we applied GUTS to explain how unsafety signals in the context of severe uncertainty are likely to affect employee emotional exhaustion. We therefore situate severe uncertainty as a defining contextual factor that demarcates where GUTS, as opposed to other theoretical approaches, becomes particularly useful for predicting and explaining for explaining employee well-being.

From existing research on disaster-related stress and its effects on workplace phenomenon, we might presume that workplace disruption caused by COVID-19 acts as a stressor that contributes to employee strain (Sanchez et al., 1995) and that organizations may provide resources to buffer the effects of that stressor. Because transboundary disasters are characterized by their direct and indirect effects (Quarantelli et al., 2018), the COVID-19 experience does not always have to involve a concrete, tangible stressor. For instance, in transboundary disasters such as COVID-19, employees are situated within a context that may not have clear time-bound indicators of whether they are likely to be exposed to threats nor what the exact nature of that exposure might be. From a GUTS perspective, people look to their environment (i.e., industry disruption) to gauge the threats are possible, with the consequences of severe uncertainty being experienced anxiety and poor well-being.

This study has implications for how theory is applied in times of transboundary disasters and ensuing severe uncertainty. We required a theoretical perspective that would be able to explain how and why macro-level conditions of severe uncertainty would affect employees at an individual level. While these connections of interest might be broadly extrapolated from a stressor-strain model, they do not fit entirely within the spirit of a stressor-strain model, such as the Job Demands-Resources Model (Bakker et al., 2005). This is because job demands, the primary stressor examined in this type of model, are defined as a type of job characteristic that represents “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological effort” (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017, p. 274). In studying severe uncertainty, we are not studying a job demand, per se. Individuals who were never exposed to a specific traumatic event during the pandemic have reported trauma symptoms, confused as to how to cope with something that isn’t tangible (Lonsdorf, 2022). Similarly, employees who did not directly experience common effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., did not lose their job; did not contract the virus from work) were still likely to experience exhaustion (Reston et al., 2022).

This distinction is important as research has demonstrated that different cognitive appraisals and outcomes occur depending on whether someone is exposed to uncertainty or a tangible threat (e.g., Carleton, 2016; Chen et al., 2018; Freeston & Komes, 2022; Freeston et al., 2020; Reuman et al., 2015). Stressor-strain models like JD-R do not address or account for this distinction or the implications it has for ways to mitigate strain. While stressor-strain models hold that resources can buffer the effects of stressors, they stop short of explaining what resources should be helpful under conditions of severe uncertainty. On the other hand, GUTS inherently addresses environmental uncertainty and explains that it can originate in one’s larger social environment. Severe uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic originates outside of the job context, and the signals of unsafety we study are at the industry level of analysis.

Our application of GUTS to COVID-19 as a transboundary disaster provides a theoretical perspective that might help to explain why other work has found that providing employees with more resources did not predict employee distress, prevent large-scale workforce shifts, or help business owners overcome staffing challenges (Knight et al., 2023; Rosenberg, 2021). According to GUTS, employee strain may be mitigated when the stress response is inhibited by the perception of sufficient safety signals. It is possible that resources provided to help employees better perform their jobs during times of disruption do not sufficiently address or counteract industry-level unsafety signals.

While it was not feasible (due concerns over participant attrition) to collect the additional data needed to robustly compare theoretical approaches in our analyses, we were able to accomplish our goal of applying GUTS as the model that best met our theory needs. The results of this study provide support for further testing of the applicability of GUTS and its explanatory power compared to other models. By a GUTS framework provides more theoretical specificity in terms of how and why environmental signals are likely to contribute to employee strain in contexts of severe uncertainty. When severe uncertainty is not a defining contextual factor, a stressor-strain framework is likely sufficient to explain employee-well-being. However, we hope that future research will continue to examine whether this is the case. It could be that some of the unresolved issues in stressor-strain models might be addressed by considering how job demands may represent unsafety signals and how job resources may represent safety signals. One question for future theoretical development might be whether there is a sort of safety signal threshold for determining whether a stress response is inhibited or disinhibited based on a combination of relevant job characteristics. Moreover, future research might more formally test the impact of the background of severe uncertainty by examining the relationships tested here in non-crisis (i.e., non-transboundary disaster) situations. This might be helpful, for example, to understand how more narrow health crises (e.g., flu outbreaks) may impact worker well-being.

Our findings are consistent with the GUTS concept of general environmental unsafety that can fuel the stress response and contribute to the development of employee strain (Brosschot et al., 2018). Therefore, it appears GUTS can account for the complexities of transboundary disasters as ambiguous, wide-reaching situations that contribute to signals of safety that play a role in employees’ work and non-work lives. The results of this study support GUTS as a framework for explaining how severe uncertainty and contextual unsafety that characterizes transboundary disasters may lead to employee well-being crises such as our current state of employee burnout and workforce disenchantment.

This interdisciplinary lens expands occupational health theory to account for the unique characteristics of transboundary threats, compared to traditional disaster and crisis scenarios. Because the field’s theoretical understanding of employee stress in times of transboundary disasters is likely to inform practice (e.g., in the development of interventions or organizational policies), it is important to expand research on occupational stress to understand employee stress processes during transboundary disasters like COVID-19.

While employee COVID-19 economic anxiety is likely to result from industry-level signals of economic unsafety, our findings suggest that COVID-19 health anxiety triggered by industry-level health unsafety might have been more salient than economic concerns–at least initially. For example, one worker expressed disapproval of their organization’s efforts to stay open: “I think it would be better if we closed our establishment for the outbreak because it is getting a lot worse in our area. By staying open we are basically inviting the virus to infect us.” Perhaps unsafety of one’s physical health carries a stronger sense of immediacy and urgency than unsafety of one’s financial stability. Because GUTS was developed from an evolutionary perspective that emphasizes vigilance toward unsafe conditions as a key survival instinct (Brosschot et al., 2016), it makes theoretical sense that uncertainty related to one’s immediate health may create stronger anxieties in employees, whereas economic conditions might be a bit more distal to their sense of survival. Perhaps over time, depending on ways that organizations respond to health and economic disruptions caused by COVID-19, employees may perceive sufficient safety signals related to their physical health. Then, signals of COVID-19 economic unsafety may be more likely to explain remaining COVID-19 anxiety. In other words, as a sense of physical safety in the workplace is regained, it could be that economic unsafety begins to become more salient. One worker expressed this sentiment: “I am slightly afraid of contracting COVID-19 due to my workplace still requiring me to come to work in order to get paid. However, I'm more afraid of not being able to get a paycheck.”

Another possible explanation for the observed salience of COVID-19 health anxiety over economic anxiety in predicting emotional exhaustion may be that economic unsafety resulting from COVID-19 is so ambiguous that employees struggle to consciously relate their anxiety to economic unsafety. According to GUTS (Brosschot et al., 2018), the disinhibition of the stress response primarily occurs unconsciously, and people can make incorrect attributions to their sense of uneasiness. Because COVID-19 is a public health transboundary disaster, the limited information that does exist is information relevant to one’s physical health. It may therefore be easier to attribute feelings of anxiety to health-related concerns than economic ones.

Still, economic uncertainty represented a salient signal of perceived unsafety in this study. While limited health-related information contributed to severe uncertainty and a sense of health unsafety, this uncertainty may have been even more severe in the consideration of economic unsafety: it’s even more challenging to predict whether COVID-19 economic unsafety might develop into actual economic threat. Along these lines, there were more tangible ways in which organizations can help to produce health-related signals of safety (e.g., creating conditions that signal to employees that the virus is more distant) compared to economic safety signals. As a result, employees’ financial contexts, which are important for perceived safety (Brosschot et al., 2018), are especially likely to be “compromised,” to use the Brosschot et al. terminology–even in the absence of concrete financial threats. One participant’s comments exemplify this economic unsafety: “Our business is closed completely until we don't know when. We still have competitions coming up. our season is ruined and nobody knows what to do or what's going to happen.” Although our findings suggest that health unsafety might be a stronger predictor of emotional exhaustion in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, GUTS would suggest that the challenge of grappling with economic unsafety may still lead to further strain development.

Practical Implications

Because the COVID-19 pandemic is unlikely to be the last time industries and organizations are faced with severe uncertainty, the understanding of mechanisms through which perceptions of macro-level safety affect employee well-being is critical for supporting employees who are asked to perform their work in new and different ways. Recent research has begun to examine the long-term effects of the pandemic, finding that COVID-19 has the potential to elicit post-traumatic stress disorder in employees directly and indirectly exposed to the virus, especially for front-line workers who disproportionately exposed (e.g.,Adeyemo et al., 2022; Bridgland et al., 2021) Therefore, these results have both short- and long-term implications for employees, managers, organizations, and industries facing the context of unsafety brought about by COVID-19 disruption, and potential future transboundary disasters.

Drawing from GUTS principles, the results of this study suggest it’s likely that severe uncertainty compromises the ability of work contexts to contribute to employees’ perceptions of safety, and the anxiety resulting from macro-level signals of unsafety is exhausting. Because mediators represent mechanisms of change that indicate where interventions may be potentially beneficial (O’Rourke & MacKinnon, 2018), these results provide initial insights into not only a possible point of intervention (the unsafety to anxiety path), but also a potential type of intervention (provision of safety signals). Therefore, some of the negative effects of severe uncertainty on employee well-being may be mitigated by finding ways to create safety signals early on.