Abstract

Adoptive cell therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) is gaining momentum and demonstrating durable responses in patients with advanced melanoma. Although increasingly considered as a treatment option for select patients with melanoma, TIL therapy is not yet approved by any regulatory agency. Pioneering studies with first-generation TIL therapy, undertaken before the advent of modern melanoma therapeutics, demonstrated clinical efficacy and remarkable long-term overall survival, reaching beyond 20 months for responding patients. TIL therapy is a multistep process of harvesting patient-specific tumor-resident T cells from tumors, ex vivo T-cell expansion, and re-infusion into the same patient after a lymphodepleting preparative regimen, with subsequent supportive IL2 administration. Objective response rates between 30% and 50% have consistently been observed in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma, including those who have progressed after modern immune checkpoint inhibitors and BRAF targeted agents, a population with high unmet medical need. Although significant strides have been made in modern TIL therapeutics, refinement strategies to optimize patient selection, enhance TIL production, and improve efficacy are being explored. Here, we review past and present experience, current challenges, practical considerations, and future aspirations in the evolution of TIL therapy for the treatment of melanoma as well as other solid tumors.

Introduction

In the last decade, the melanoma treatment landscape has dramatically transformed with approvals for immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) antibodies targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death receptor-1 (PD-1), as well as small-molecule inhibitors targeting the B-Raf proto-oncogene (1, 2). These treatment modalities improve long-term survival of patients and reduce the risk of relapse in the adjuvant setting (3). Unfortunately, despite these advances, most patients experience disease progression (4). As such, there remains a substantial unmet need to identify effective therapies for treatment-refractory disease.

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) has emerged as an alternative immunotherapy strategy in melanoma that focuses on harnessing the antitumor abilities of tumor-resident antigen-specific T cells (5–7). The highest overall response rate (ORR, 49%) among patients with advanced melanoma after failure of an approved front-line therapy has been demonstrated with TIL therapy (8). Single-center studies have been critical in laying the foundation for TIL therapy in advanced melanoma (9). Historically, these trials were undertaken in specialized institutions with on-site cell therapy manufacturing facilities (10, 11). Recently, with the expansion of cell therapy technologies, commercial enterprises have established off-site manufacturing facilities that have widened access to TIL therapy with the potential to benefit more patients (12). Accumulated data generated from multicenter, international programs support commercial approval of TIL therapy for the treatment of advanced melanoma, shifting this intervention from an academic pursuit offered at a few select centers to a viable therapeutic option available internationally. Here, we discuss clinical experiences with TIL therapy, the rationale to support future combination with ICIs and other agents, practical considerations for an approved TIL product, and the next generation of therapeutic TILs.

Clinical Experiences

Intrinsic and acquired resistance to front-line ICIs is common and driven by multiple factors (13). Resistance, with a high likelihood of recurrent disease in patients receiving adjuvant ICIs, further emphasizes the need for effective treatments in this ICI-refractory population (14). A variety of immune-activating adoptive cell therapy approaches are being tested in the hope of overcoming these resistance mechanisms (15, 16).

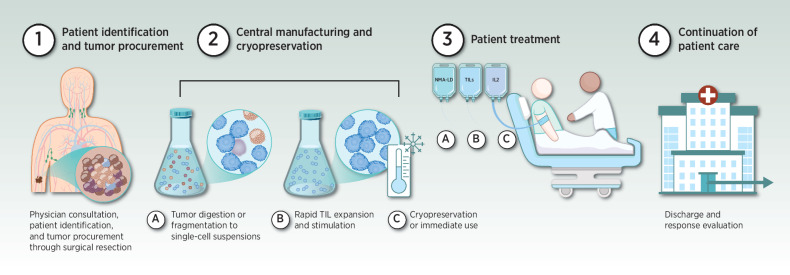

TIL therapy requires harvest of autologous T cells from tumor material by surgical resection, stimulation ex vivo by coculture with cytokines and expansion, to generate the TIL infusion product (15). TILs are infused back into the same patient after non-myeloablative lymphodepletion (NMA-LD) with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, enabling preferential engraftment of the TIL population (17). Post-TIL infusion, IL2 is administered to facilitate in vivo expansion of the infused T cells (18), followed by a short recovery period to support resolution of IL2-related toxicities (Fig. 1; ref. 19).

Figure 1.

Overview of TIL therapy. Current TIL therapy begins with physician consultation, patient identification, and tumor procurement through surgical resection (step 1). Tumors are then transported centrally to a manufacturing facility or processing hub. TILs are manufactured beginning with digestion and culture or fragmentation of tumors, which yields a suspension of T cells, followed by stimulation and rapid expansion. Manufacturing of unmodified TIL is relatively quick (3 weeks) compared with modified or neoantigen-enriched TIL, which could take several months. The final TIL product is cryopreserved (step 2). TILs are held for later use or immediately transferred to the treatment site. The patient receives NMA-LD for 5 to 7 days, followed by a one-time intravenous infusion of TILs, and supportive IL2 therapy for 3 to 5 days (step 3 A, B, C). The patient is discharged following resolution of chemotherapy and IL2-related toxicity before being evaluated for response (step 4).

Pioneering work in this field was performed by Rosenberg and colleagues beginning in the 1980s, demonstrating the patient-specific antitumor activity of cultured TILs in vivo (20), with clinical effectiveness in diverse cancers (21). Because of the first signal of clinical responses (22, 23), a series of single-center phase I to III clinical trials have demonstrated reproducible efficacy (ORRs, 34%–56%; PFS, 3.7–7.5 months; OS, 15.9–21.8 months) of TIL therapy in metastatic melanoma despite differences in patient characteristics, lymphodepletion regimens, IL2 administration, TIL manufacturing process, and TIL dose (refs. 8, 10, 11, 19, 24–27; Table 1). These encouraging results have stimulated centers worldwide to conduct studies which define the role of TIL therapy in melanoma management and have been summarized previously (15, 16). Here, we focus on the studies that have shifted from an academic single center institution to a centralized manufacturing process to enable broad access to TIL therapy through registrational studies with the intent for regulatory approval.

Table 1.

Clinical efficacy of select TIL therapy trials in melanoma.

| Trial | No. of prior therapies, % | Intervention/Pts, n/ disease stage | Lymphodepletion/ IL2 regimen | TIL preparation | TIL product/ IL2 doses received | Efficacy outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosenberg et al. 1994 (127) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Schwartzentruber et al. 1994 (128) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dudley et al. 2002 (23) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dudley et al. 2010 (129) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rosenberg et al. 2011 (9) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Radvanyi et al. 2012 (130) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Besser et al. 2013 (38) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Anderson et al. 2016 (25) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Goff et al. 2016 (24) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| van den Berg et al. 2020 (26) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sarnaik et al. 2021 (12) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Seitter et al. 2021 (10) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Levi et al. 2022 (33) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Haanen et al. 2022 (8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: BRAF, B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase; CD, cluster of differentiation; CR, complete response; Cy, cyclophosphamide; d, day; Flu, fludarabine; HD, high-dose; hr, hour; IO, immunotherapy; LD, low-dose; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; mo, months; NE, not estimable; NR, nonresponder; OS, overall survival; s.c., subcutaneous; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; pts, patients; RFS, relapse-free survival; TBI, total body irradiation; wk, week, yr, year.

aIn the cohorts treated in this report, there was no difference between the age of CD8+ enriched young TIL cultures for responding and nonresponding patients.

bThree additional patients received cryopreserved TIL from prior resections.

cOf 101 patients randomly assigned to cohorts 1 or 2, all completed their planned treatment course except two patients in cohort 2 (TBI arm), whose treatment was aborted for progressive disease.

In today's modern era of TIL therapy, studies have incorporated efficiencies in production, treatment, and product characterization. Recently, lifileucel (LN-144), comprising autologous, unmodified TIL infusion, has demonstrated encouraging results in patients with unresectable stage III and IV melanoma in the post–PD-1 inhibitor setting (NCT02360579; ref. 12; Table 1). In this multicenter, international, single-arm phase II multicohort study, TILs were unmodified and centrally manufactured in approximately 3 weeks (12). In cohort 2, nearly all 66 patients had progressive disease despite prior anti–PD(L)-1 exposure; the mean number of prior therapies was 3.3; 17 patients were B-RafV600 mutation–positive, of whom 88% had progressed on BRAF targeted agents; 34 patients previously received combination anti–PD-1/anti–CTLA-4, either as front-line therapy (23%) or after failing front-line therapy (29%; ref. 12). For all patients, the ORR was 36% (mOS, 17.4 months), with two complete responses (CR) and 22 partial responses. The best ORR was observed in patients with progressive disease after initial anti–PD(L)-1 therapy (n = 42, ORR = 41%) and was consistent after anti–lymphocyte-activation gene (LAG) 3-containing regimens (12, 28). Recent results from the pivotal cohort 4 of the study (n = 87) demonstrated an ORR of 29% (29). When analyzed together, cohorts 2 and 4 led to a combined ORR of 31%, providing an effective and durable (12-month response rate, 54%) treatment option for heavily pretreated patients with PD-1 refractory melanoma (29). Collectively, lifileucel demonstrated meaningful responses in advanced melanoma and may become the first TIL therapy approved in this setting.

A retrospective analysis of an independent single-site compassionate use program with an alternative unmodified TIL product currently under commercial development reported a response rate of 67% in 21 patients (mOS 21.3 months); the median number of prior therapies was 2 (30). For the 12 patients who received prior anti–PD-1 and anti–CTLA-4 therapy, the response rate was 58% (30). Although responses were rigorously collected with RECIST-compatible assessments in the majority of patients, retrospective analyses of overall response rates in nontrial settings do have limitations. A large-scale, international phase II study (NCT05050006) is currently evaluating an updated version of the manufacturing process for that product, ITIL-168, in patients with advanced melanoma relapsed or refractory to anti–PD-1 therapy (31). Hannen and colleagues reported the first multicenter phase III study of TIL therapy (NCT02278887) where patients with unresectable stage IIIC to IV melanoma were randomized to receive TIL therapy (n = 84) or ipilimumab (n = 84; ref. 8). The majority of patients (86%) were refractory to anti–PD-1 therapy. TIL therapy resulted in improved PFS (median, 7.2 months vs. 3.1 months, respectively), ORR (49% vs. 21%), and OS (median, 25.8 months vs. 18.9 months) compared with ipilimumab (Table 1). Taken together, these results, and the aforementioned findings, support a new era of cell-based personalized therapeutics, demonstrating feasibility of TIL therapy with consistent response rates and opportunities for paradigm-shifting approaches to treating melanoma.

Despite new standards of care (32), retrospective analyses suggest that PD-1 experienced patients may be less responsive to TIL therapy than PD-1 naive patients (10, 33). Among 112 anti–PD-1 naive and 69 anti–PD-1 experienced patients with metastatic melanoma who responded to TIL therapy, those with T cells that recognized at least one tumor neoantigen demonstrated response rates of 56% (CR, 51%) and 41% (CR, 8%), respectively (33). In another retrospective analysis of the experience at the NCI, Seitter and colleagues demonstrated response rates of 56% (mPFS 6.5 months) in PD-1 naive patients and 24% (mPFS 3.2 months) in PD-1 refractory patients (all patients, mOS 20.6 months; ref. 10). Prospective trials are needed to confirm these differences. Given the higher response rates in PD-1 naive patients (Table 1), TIL therapy administered earlier in the treatment sequence may provide a greater benefit. It is unknown whether patients who progress after first-line anti-PD-1 inhibition should consider TIL as a second-line option rather than proceeding immediately to combination ipilimumab/nivolumab therapy. Cumulatively, efficacy of TIL therapy in the setting of anti–PD-1 refractory disease compares favorably to other immunotherapy options which may provide a lower ORR (range, 13%–31%) and shorter PFS (range, 2–5 months; refs. 30, 34–37). Although initial indications suggest that anti–PD-1, anti–LAG-3, and anti–CTLA-4-refractory tumors respond to TIL therapy (9, 28, 38), this question will need to be supported with further research, such as differences in T-cell functionality (39).

Adverse events

Administration of TIL requires trained, experienced staff and access to intensive care unit support (40, 41). The most common toxicities during TIL therapy are attributable to NMA-LD and/or IL2 (15, 16, 41, 42). Expected treatment-emergent adverse events (AE) from NMA-LD include grade 3 or 4 cytopenias in most patients (12, 16), whereas toxicities associated with IL2 are dose- and schedule-dependent (25). IL2-related toxicities are generally predictable, manageable, and transient (11, 42, 43). Administration of supportive high-dose IL2 therapy is medically challenging, and the optimal IL2 dose and schedule is as yet undefined (16, 44). The lifileucel regimen incorporates intravenous bolus IL2 (600,000 IU/kg) every 8 to 12 hours for up to six doses (12), whereas other protocols are utilizing lower doses of IL2 (Table 2). Even so, the T-cell supportive role that IL2 plays in TIL therapy, rather than a directly therapeutic intent, allows for the avoidance of severe IL2-related toxicities through the discontinuation of IL2 at the earliest sign of significant toxicity (12, 42). TIL infusion itself is generally uneventful (41). Rarely, administration can be associated with dyspnea, chills, and fever in the brief period following infusion (15). These AEs have not been correlated with high serum levels of circulating cytokines and should not be confused with cytokine release syndrome commonly reported with other cell therapies like chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy (45). Given the theoretical risk of TIL-mediated neurologic events from infiltration into the central nervous system and complications of IL2 administration for patients with active brain lesions (46), the safety of TILs in patients with brain metastasis is currently being addressed in clinical trials, although early evidence of CNS response has been seen (47).

Table 2.

Select accruing trials of TILs in solid tumors.

| Type of TIL/trial number | Phase/study start date/estimated enrollment, n/sponsor | Tumor type(s) | Select eligibility criteria | Select treatment details | Select primary outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: 1L, first-line; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; ASCC, anal squamous cell carcinoma; ATLAS, Antigen Lead Acquisition System; BRAF, B-raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase; CNS, central nervous system; CPI, checkpoint inhibitor; CSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; Cy, cyclophosphamide; d, day; DC, dendritic cell; DCR, disease control rate; DLT, dose-limiting toxicities; DOR, duration of response; ECGs, electrocardiograms; EC, endometrial cancer; Flu, fludarabine; GI, gastrointestinal; HD, high-dose; HLA, human leukocyte antigens; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HPV, human papillomavirus; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; i.d., intradermal; IO, immunotherapy; IV, intravenous; LD, low-dose; MASE, multiple antigen specific endogenously derived; NY-ESO-1, New York Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma-1; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PARPi, poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death protein-ligand 1; PFS, progression-free survival; PROC, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer; q, every; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; ROS, c-ROS oncogene 1; R/R, relapsed/refractory; sc, subcutaneous; SCCHN, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; TEAE, treatment-related adverse events; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TPS, tumor proportion score; txt, treatment; UC, urothelial carcinoma; US, United States; wk, week; yr, year.

Trial identification and information compiled from ClinicalTrials.gov (accessed June 3, 2022). Trials are placed in order of the most recent study start date.

aTrial is open and not yet enrolling.

bDose level was not specified.

Combining TILs with ICIs

An appealing therapeutic approach to melanoma treatment is the possibility of combining TIL therapy with anti–PD-1 to enhance efficacy and durability of response (48). Evidence indicates that PD-1 regulates the interaction between tumors and autologous T cells, thus, the effects of TIL therapy may be enhanced by blocking immunosuppressive signals in the tumor microenvironment (TME) through checkpoint blockade (49). High PD-1 expression has been observed in tumor-reactive CD8+ T-cell subsets post-TIL therapy (50). Tumor-expressed PD-L1 binds to PD-1 on TILs, which counteracts the T-cell receptor (TCR)-signaling cascade and impairs T-cell activation (51). Inhibiting the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling axis is a feasible strategy to restore and reset immune responses in the TME (52). At a median follow-up of 11.5 months, the phase II IOV-COM-202 study (NCT03645928) of combination lifileucel and pembrolizumab in 10 patients with ICI-naive metastatic melanoma recently reported OR and CR rates of 60% and 30%, respectively (53). Although more patients need to be treated before efficacy can be reliably assessed, this combination is feasible without significant increases in toxicity (53). Common grade ≥3 treatment-emergent AEs were manageable and consistent with those expected from pembrolizumab, NMA-LD, and IL2 (53). One downside to this approach is that it shifts TIL therapy from a one-time dosing strategy to require long-term administration of pembrolizumab (≤2 years; ref. 53). Preclinical (54) and ongoing clinical studies (NCT03374839, NCT02621021) suggest that there are multiple mechanisms by which PD-1 blockade may enhance outcomes with ACT, including effects on both the endogenous T-cell response as well as the cell therapy product.

Blockade of CTLA-4 with ipilimumab promotes antigen presenting cell (APC)-mediated T-cell activation and antitumor responses (55). Compared with patients who do not receive anti–CTLA-4, ipilimumab induces broad and frequent T-cell responses against common tumor antigens and may induce naïve-like tumor-infiltrating T cells (56). A small pilot study (NCT01701674) of combination TIL and ipilimumab for n = 13 patients with metastatic melanoma reported an ORR of 38% with median progression-free survival of 7.3 months (57). As new ICIs are being developed, including the recent approval of the LAG-3 inhibitor relatlimab for melanoma (58), opportunities for combination studies with TIL therapy will expand.

Practical Considerations

Patient selection

Selecting patients likely to benefit from TILs is an area of high interest. As with ICIs, patients who appear to benefit most from TILs have slowly progressing soft tissue disease (59). Anecdotally, Mehta and colleagues reported that patients with high disease burden, including disease in sanctuary sites like the brain, have responded to TILs (47), although these patients are typically excluded from TIL trials. Moreover, shorter exposure to prior anti–PD-1 therapy may maximize the duration of response to TIL treatment (60). Prognostic factors, such as serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase, disease burden, and specific organ involvement (e.g., soft tissue disease versus liver, brain, bone metastases), may ultimately be used to identify patients most likely to achieve additional benefit and long-term survival from TIL therapy (4). Emerging biomarkers may predict response to TIL, including checkpoint expression and tumor mutational burden/tumor recognition, which are currently under investigation (61). In light of the recent data that ICIs should be considered before targeted therapy for BRAF-mutated melanoma (62, 63), on-treatment biomarkers [liquid biopsies, circulating tumor DNA (or ctDNA) monitoring, and immune profiling] may help provide the basis for rational treatment sequencing and optimal patient selection (64).

Banking models

One of the largest challenges of TIL therapy is the time needed to harvest and expand the T-cell population, which inevitably generates delays for patient intervention (65). Typical manufacturing times are currently around 3 weeks (12) to 3 months (66). As such, there is great interest in shortening the wait time from clinical decision to treat with TIL until the product is available for infusion. One approach is TIL harvest at an earlier time point prior to when the product might actually be needed (67). TILs might be stored either as the frozen tumor sample or a manufacturing intermediate and the sample will be ready for rapid completion of manufacturing at the time when clinically indicated (68, 69). Best practices and optimal patients to consider for tumor banking have yet to be established (70). The implications of utilizing TIL banked earlier in the patent's course of disease for subsequent treatment of a dynamic and progressing disease remain unknown. Banking may preserve tumor reactive T cells, however the efficacy of TIL products made from banked tumors could be impacted by changes to the patient's tumor during disease progression or intercurrent anticancer therapies. As access to TIL therapy is anticipated to increase in the near future, a comprehensive effort and approach to establish tumor bank initiatives are warranted (71).

Bridging therapy

A strategy to decrease drop-out rates due to disease progression during TIL production includes the administration of “bridging therapies,” allowing systemic therapy to be given between the time of TIL harvest and lymphodepleting chemotherapy (57, 72). Historically, this has not been built into TIL trial protocols, as dropout rates between 12% and 21.9% demonstrate that some patients experienced disease progression that precluded them from receiving TIL after successful harvest and manufacturing (25, 38, 73). However, groups evaluating modified TIL products requiring a protracted manufacturing period of several months are building the option for bridging into their protocols. To mimic expected clinical practice upon approval, the lifileucel expanded access program is allowing bridging therapy for patients with melanoma (NCT05398640) and so will patients with solid tumors receiving ITIL-168 (NCT05393635). For BRAF-mutant melanoma, BRAF-targeted agents are an attractive bridging option, as they have high response rates but with typically limited durability (74). Stopping these agents, even for patients who are experiencing clinical progression, can lead to tumor flare (75), so bridging with BRAF-targeted agents is an appealing option. For BRAF-wild type disease, while driven by prolonged T-cell activation and restored T-cell proliferation needed for T-cell–mediated immunity, CTLA-4 bridging or priming approaches may be limited by the relatively high incidence of long-lasting toxicity (76). A single cycle of cytotoxic chemotherapy may be an alternative, viable option for these patients (77). Furthermore, particularly in BRAF-wild-type disease, a banking approach before embarking on front-line anti–PD-1-based therapy may be preferable.

Cost and centralization of TIL therapy

Costs of manufacturing and administration of TIL is clearly a major concern for healthcare providers and payers (78). It is anticipated that commercial TIL products will have high overhead costs as a result of start-up activities of a TIL therapy program (79). In the context of other therapies that require chronic administration sometimes over years (78), TIL therapy may potentially offer a cost-effective addition to the melanoma armamentarium as it is a personalized, one-time treatment approach (65). With growing experience, delivering some elements of TIL therapy in an out-patient setting may be feasible and reduce high in-patient costs, but will require a multidisciplinary approach and coordination, especially for logistical and reimbursement issues (80). Current models established by approved cell therapies provide the opportunity to leverage and expand upon such successful programs (81).

Other considerations

Clinical and commercial cell therapy products must meet regulatory requirements of safety, purity, and potency prior to manufacturing release. Of the numerous product release assays, potency assays have attracted significant attention due to the complex and/or not fully characterized mechanisms of action for TIL therapy (82). Clinical activity of a TIL product likely depends on several factors including the diversity and functional avidity of the TCR repertoire, the frequency of antitumor clonotypes in the final product, ability of the infused cells to efficiently traffic to tumors, and the phenotypic differentiation and state of exhaustion of antitumor clones (83). Patient-related factors including the status of the endogenous immune system, performance status, and comorbidities, as well as tumor burden and disease sites may well influence response to therapy (6). Furthermore, features of the tumor itself, including dynamic and heterogenous tumor antigen expression (84), complicates the routine assessment of antitumor activity of TIL products since practicalities of tumor procurement may limit capturing the full spectrum of antigens present in the patient (85). Thus, some tumor-specific T-cell clones present in the TIL product may be improperly designated tumor nonreactive. Finally, a potency assay must be robust, rapid, and reproducible within a GMP quality control environment (82). Common components of modern potency assays designed for products made from bulk, unselected TIL include nonspecific, or, less commonly, tumor-specific activation of TIL assessed by multiparametric assays including cytokine expression, upregulation of surface markers of activation and TIL-mediated tumor cell death (86). Although these assays are tuned to describe a TIL product's functionality in vitro, correlation with clinical responses have yet to be confirmed in prospective clinical trials (9, 12, 87, 88). In summary, given these constraints, development of potency assessment to support registrational trials, commercialization, and licensing of these products lags behind the reproducible clinical efficacy of TIL in melanoma, including in multicenter trials designed to lead to regulatory approval.

Future Changes and Technologies

Next-generation TILs

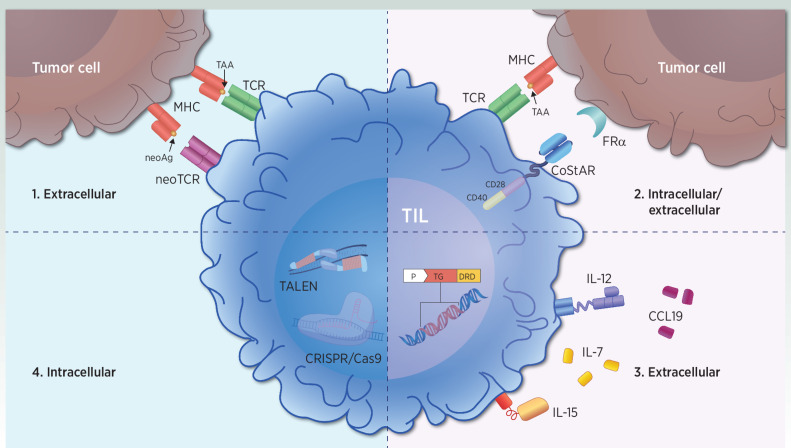

As the field of TIL therapy rapidly evolves, technologic advances are being developed to enhance the antitumor efficacy of the TIL product. The next generation of TILs (Table 3) are based on the pillars of effective immune activation (89). First, TCR recognition of the intratumor clonal neoantigen heterogeneity is a determinant of the adaptive immune response to cancer (Fig. 2, strategy 1; ref. 90). TIL therapies, such as lifileucel and ITIL-168, have shown that an unrestricted TCR repertoire in TIL products can counter tumor heterogeneity and deliver clinical responses (ORRs 36%–67%; refs. 12, 31). Moreover, neoantigen-specific TILs have demonstrated persistence lasting nearly 3 years after TIL infusion (26). Clinical studies of predefined, neoantigen-specific TIL infusion products are underway to create TIL and TCR therapy products with a higher fraction of tumor-specific TCRs (66, 91–94). The possibility to select specific TIL subsets enriched for tumor/neoantigen recognition is a potential strategy to generate specific tumor-reactive TIL (10, 25, 33); trials are ongoing, and data will be forthcoming (Table 2). Phenotypically characterizing the most tumor-reactive cell types to include in TIL products based on surface markers (e.g., PD-1 and CD137; refs. 95, 96) to identify a narrow T-cell subset for TIL therapy use (97) are additional strategies early in development. However, increasing the complexity of the manufacturing process prolongs manufacturing times and risks disease progression and patient withdrawal before accessing treatment (98). The cost–benefit balance to both patients and payers will need to be carefully assessed in prospective studies.

Table 3.

Select list of next-generation therapies targeting T-cell activation.

| TIL therapies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Category | MOA | Company | Strategy |

|

|

|

Achilles Therapeutics |

|

|

|

|

Instil Bio, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

Intima Bioscience, Inc. |

|

|

|

Iovance Biotherapeutics, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

|

Phio Pharmaceuticals |

|

|

|

|

KSQ Therapeutics |

|

|

|

|

Nurix Therapeutics, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

Obsidian Therapeutics |

|

|

|

|

Adaptimmune Therapeutics |

|

| TCR-T therapies | ||||

|

|

|

Adaptimmune Therapeutics |

|

|

|

|

Genocea Biosciences, Inc. |

|

|

|

|

PACT Pharma |

|

|

|

Repertoire Immune Medicines |

|

|

Abbreviations: ACZ, acetazolamide; ATLAS, antigen lead acquisition system; CCL19, chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 19; CISH, cytokine induced SH2 protein; DRD, drug response domains; DeTIL, drug enhanced TIL; eTIL, engineered TIL; Fc, fragment crystallizable; FRα, folate receptor alpha; MAGE-A4, melanoma-associated antigen-A; mb, membrane bound; neoAg, neoantigens; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; NPT, neoantigen-targeted autologous peripheral T-cell therapy; NY-ESO-1, New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1; PDCD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PRAME, preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma; scFv, single-chain fragment variable; TAA, tumor-associated antigens; TCR-T, TCR-engineered T cell; WT1, Wilms tumor 1.

Figure 2.

Strategies to optimize T-cell activation in next-generation TIL. Immune-modulation strategies involve improvements in intracellular and extracellular signaling. Strategy 1. Extracellular T-cell activation occurs via TCR/neoTCR-mediated recognition of TAA or neoAg peptides. Novel therapeutic products select and enrich for pre-existing tumor antigen-specific T cells. Strategy 2. Intracellular and extracellular enhancements of T-cell activation and effector function occur through dual CD28 and CD40 intracellular signaling domain-mediated costimulation upon TCR-mediated antigen recognition. Strategy 3. Extracellular T-cell activation through the local delivery of immunomodulatory molecules such as IL7 and CCL19, as well as cell-anchored IL12, or drug-inducible membrane-bound IL15 expression. Strategy 4. Increasing T-cell fitness and reducing T-cell exhaustion with intracellular strategies such as PDCD-1 knockout with TALEN, and CT-1 knockout with CRISPR/Cas9. CCL, chemokine (C–C motif) ligand; FRα, folate receptor alpha; neoAg, neoantigens; TAA, tumor-associated antigens.

Improved TIL function through synthetic costimulation may mitigate known mechanisms of immune escape and resistance to TIL therapy (Fig. 2, strategy 2; ref. 27). Including a synthetic costimulatory antigen receptor (CoStAR) molecule with dual CD28 and CD40 domains on healthy donor T cells targeting the tumor-associated antigen CEA led to increased T-cell activation and long-term proliferation even in the absence of IL2 (99, 100). Furthermore, the enhancement of cytokine-induced immune activation may be accomplished through the local delivery of cytokines outside of IL2 (Fig. 2, strategy 3; ref. 101). Inclusion of growth-promoting cytokines with TIL products is also being examined. The genetically engineered TIL cytoTIL15 expresses a regulated form of membrane-bound IL15 under the control of carbonic-anhydrase-2 drug response domains, activated by acetazolamide (102). Although the regulated expression of IL15 allows for tunable antigen-independent long-term TIL persistence in a dose-dependent manner (102), secondary effector memory T-cell differentiation may be impaired (103). In addition, T cells with membrane bound IL15 (91), IL7/CCL19 expressing specific peptide enhanced affinity receptor (SPEAR) T cells targeting the tumor antigen MAGE-4 (104), and T cells anchored with IL12 (105, 106) are also under investigation.

Although pitfalls have been encountered when investigating alternative cytokines (107, 108), new therapies may reduce T-cell exhaustion in the TME, which is a defining feature in many cancer types (Fig. 2, strategy 4; ref. 109). To simulate therapeutic effects of PD-1 inhibition, PD-1 silencing with INTASYL-mediated self-delivering siRNA (or PH-762) in TIL products was efficient (85% knockdown), and TILs displayed an activated and improved effector phenotype (110). When using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN)-based gene knockout of the PD-1 gene PDCD-1 in TILs (IOV-4001), T cells exhibited improved in vivo effector function (111, 112); these results prompted clinical investigation in metastatic melanoma (NCT05361174).

Furthermore, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based knockout of the negative TCR-signaling regulator cytokine-induced SH2 (CISH) protein in TIL led to increased TCR avidity, neoantigen recognition, and tumor cytolysis (bioRxiv 2021.08.17.456714; refs. 113–115). KSQ-001, an engineered TIL therapy, was created via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of a novel, and yet undisclosed, intracellular immune checkpoint (cell therapy-1, CT-1) identified in peripheral T cells (116), resulting in polyfunctional and proliferative T cells, which are under clinical development (NCT04426669). Ex vivo treatment of autologous TILs with NX-0255, a potent, small-molecule inhibitor of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Casitas B-lineage lymphoma proto-oncogene-B (CBL-B), resulted in drug enhanced TILs (DeTIL-0255) that were less exhaustive and showed enhanced cytolytic T-cell activity (117), which is being tested in gynecologic malignancies (NCT05107739).

Application beyond melanoma

TIL therapy, with its broad and patient-specific polyclonality (15, 26), has exciting potential to overcome clonal tumor heterogeneity and induce deep and durable remissions in a growing list of treatment-refractory cancers other than melanoma (Table 2). In a single-site phase I study, patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC; including 4 patients with EGFR mutations), who progressed after nivolumab monotherapy received TIL followed by maintenance nivolumab for up to a year and reached an ORR of 23% (118). Twenty-seven patients with cervical carcinoma (CC) who had progressed on standard of care treatments received TIL and achieved an ORR of 44.4% (119). Lifileucel and LN-145, in combination with pembrolizumab, have also shown promise in advanced ICI-naive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC; n = 18, ORR = 38.9%) and advanced untreated CC (n = 14, ORR = 57.1%), respectively (53). The effectiveness of unmodified TILs in renal cell carcinoma (RCC), gynecologic malignancies, and gastrointestinal cancers have shown mixed results, due to difficulties in TIL manufacturing (120, 121), changes in subclonal tumor heterogeneity after prior treatment exposure (122), or a low frequency of tumor reactive TILs (123). In preclinical models, preferential expansion of CD137/PD-1+ TIL may select for rare tumor-reactive TIL, thereby making this treatment modality potentially relevant for cancer types that have not previously demonstrated efficacy with nonselected TIL therapies, including myeloma and colorectal cancer (95, 96, 124, 125). Furthermore, enriched neoantigen-specific TILs have shown promise in treatment-refractory breast cancer when combined with pembrolizumab (n = 6, ORR = 50%; ref. 126). Despite these challenges, TILs are currently being explored in these indications and it is hoped that novel approaches such as those summarized in Table 3 may prove beneficial over time.

Conclusions

TIL therapy is a rapidly evolving modality, which is expected to take its place alongside ICI as part of the growing immunotherapy toolkit used to treat melanoma and other cancer types. In melanoma, data are accumulating that demonstrate significant antitumor efficacy with unmodified TILs. Advancements in our understanding of the TME provide the opportunity to enhance the therapeutic window to achieve the true potential of TIL therapy. Numerous paths to this outcome exist, including process improvements, cell engineering, and combinations with other available agents. Encouragingly, several next-generation cellular therapies are currently under or are rapidly headed for clinical evaluation. The optimal timing and sequencing of TIL therapy needed to maximize efficacy will continue to emerge as a focus in anticipation of TIL approvals. Although challenges exist, attention must focus on achieving regulatory approval of TIL therapy in melanoma and further optimizing this approach, including thorough product manufacturing and characterization, to help establish a new option to extend long-term survival in this disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by Instil Bio, Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Phylicia Aaron, PhD, of Nexus Global Group Science with funding from Instil Bio, Inc.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of publication fees. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authors' Disclosures

A. Betof Warner reports personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, BluePath Solutions, Instil Bio, Lyell Immunopharma, Immatics, Novartis, and Pfizer and personal fees and other support from Iovance Biotherapeutics outside the submitted work. P.G. Corrie reports other support from Instil Bio and Iovance outside the submitted work. O. Hamid reports personal fees from Instil Bio during the conduct of the study as well as personal fees from Alkermes, Amgen, Beigene, Bioatla, BMS, Eisai, Roche Genentech, Georgiaimune, Giga Gen, Grit Bio, GSK, Idera, Immunocore, Incyte, IO Biotech, Iovance, Janssen, Merck, Moderna, Novartis, Obsidian, Pfizer, Regeneron Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Tempus, Vial, and Zelluna and personal fees and other support from Bactonix outside the submitted work; in addition, O. Hamid's institution has research contracts with Arcus, Aduro, Akeso, Amgen, Bioatla, BMS, Cytomx, Exelixis, Roche Genentech, GSK, Immunocore, Idera, Inyte, Iovance, Merck, Moderna, Merck Serono, Nextcure, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Seattle Genetics, Torque, and Zelluna.

References

- 1. Dummer R, Flaherty K, Robert C, Arance AM, JWd G, Garbe C, et al. Five-year overall survival (OS) in COLUMBUS: a randomized phase 3 trial of encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients (pts) with BRAF V600-mutant melanoma. J Clin Oncol 39:15s, 2021: (suppl. abstr. 9507). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ugurel S, Röhmel J, Ascierto PA, Becker JC, Flaherty KT, Grob JJ, et al. Survival of patients with advanced metastatic melanoma: the impact of MAP kinase pathway inhibition and immune checkpoint inhibition-Update 2019. Eur J Cancer 2020;130:126–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Curti BD, Faries MB. Recent advances in the treatment of melanoma. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2229–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Michielin O, Atkins MB, Koon HB, Dummer R, Ascierto PA. Evolving impact of long-term survival results on metastatic melanoma treatment. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weiss SA, Wolchok JD, Sznol M. Immunotherapy of melanoma: facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:5191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar A, Watkins R, Vilgelm AE. Cell therapy with TILs: training and taming T cells to fight cancer. Front Immunol 2021;12:690499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee S, Margolin K. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in melanoma. Curr Oncol Rep 2012;14:468–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rohaan MW, Borch TH, van den Berg JH, Met Ö, Kessels R, Geukes Foppen MHet al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy or ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2022;387:2113–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Phan GQ, et al. Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T-cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:4550–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seitter SJ, Sherry RM, Yang JC, Robbins PF, Shindorf ML, Copeland AR, et al. Impact of prior treatment on the efficacy of adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:5289–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borch TH, Andersen R, Ellebaek E, Met O, Donia M, Svane I. Future role for adoptive T-cell therapy in checkpoint inhibitor-resistant metastatic melanoma. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sarnaik AA, Hamid O, Khushalani NI, Lewis KD, Medina T, Kluger HM, et al. Lifileucel, a tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy, in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2656–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schoenfeld AJ, Hellmann MD. Acquired resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2020;37:443–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Comito F, Pagani R, Grilli G, Sperandi F, Ardizzoni A, Melotti B. Emerging novel therapeutic approaches for treatment of advanced cutaneous melanoma. Cancers 2022;14:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rohaan MW, van den Berg JH, Kvistborg P, Haanen J. Adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in melanoma: a viable treatment option. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dafni U, Michielin O, Lluesma SM, Tsourti Z, Polydoropoulou V, Karlis D, et al. Efficacy of adoptive therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and recombinant interleukin-2 in advanced cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1902–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Antony PA, Piccirillo CA, Akpinarli A, Finkelstein SE, Speiss PJ, Surman DR, et al. CD8+ T cell immunity against a tumor/self-antigen is augmented by CD4+ T helper cells and hindered by naturally occurring T regulatory cells. J Immunol 2005;174:2591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, Fisher RI, Weiss G, Margolin K, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Foppen MHG, Donia M, Svane IM, Haanen JBAG. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for the treatment of metastatic cancer. Mol Oncol 2015;9:1918–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM, Leitman S, Chang AE, Vetto JT, et al. A new approach to the therapy of cancer based on the systemic administration of autologous lymphokine-activated killer cells and recombinant interleukin-2. Surgery 1986;100:262–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosenberg SA, Lotze MT, Muul LM, Leitman S, Chang AE, Ettinghausen SE, et al. Observations on the systemic administration of autologous lymphokine-activated killer cells and recombinant interleukin-2 to patients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Topalian SL, Solomon D, Avis FP, Chang AE, Freerksen DL, Linehan WM, et al. Immunotherapy of patients with advanced cancer using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and recombinant interleukin-2: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol 1988;6:839–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science 2002;298:850–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goff SL, Dudley ME, Citrin DE, Somerville RP, Wunderlich JR, Danforth DN, et al. Randomized, prospective evaluation comparing intensity of lymphodepletion before adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2389–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andersen R, Donia M, Ellebaek E, Borch TH, Kongsted P, Iversen TZ, et al. Long-lasting complete responses in patients with metastatic melanoma after adoptive cell therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and an attenuated IL2 regimen. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:3734–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van den Berg JH, Heemskerk B, van Rooij N, Gomez-Eerland R, Michels S, van Zon M, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) therapy in metastatic melanoma: boosting of neoantigen-specific T cell reactivity and long-term follow-up. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tucci M, Passarelli A, Mannavola F, Felici C, Stucci LS, Cives M, et al. Immune system evasion as hallmark of melanoma progression: the role of dendritic cells. Front Oncol 2019;9:1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larkin J, Dalle S, Sanmamed MF, Wilson M, Hassel JC, Kluger H, et al. Efficacy and safety of lifileucel, an investigational autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy in patients with advanced melanoma previously treated with anti-LAG3 antibody. Poster presented at: European Society for Medical Oncology Congress; September 9–13, 2022; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Warner AB. The clinical potential of cellular therapeutics. The American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting. June 3–7, 2022; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pillai M, Jiang Y, Hawkins RE, Lorigan PC, Thistlethwaite F, Thomas M, et al. Clinical feasibility and treatment outcomes with nonselected autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy in patients with advanced cutaneous melanoma. Am J Cancer Res 2022;12:3967–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gastman B, Hamid O, Corrie P, Gibney G, Daniels G, Chmielowski B, et al. 544 DELTA-1: A global, multicenter phase 2 study of ITIL-168, an unrestricted autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy, in adult patients with advanced cutaneous melanoma. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9(Suppl 2):A573–A. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ, Ascierto PA, Matamala L, Gutiérrez EC, et al. Relatlimab and nivolumab versus nivolumab in untreated advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2022;386:24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levi ST, Copeland AR, Nah S, Crystal JS, Ivey GD, Lalani A, et al. Neoantigen identification and response to adoptive cell transfer in anti-PD-1 naive and experienced patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:3042–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buchbinder EI, Dutcher JP, Daniels GA, Curti BD, Patel SP, Holtan SG, et al. Therapy with high-dose Interleukin-2 (HD IL-2) in metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma following PD1 or PDL1 inhibition. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Olson DJ, Eroglu Z, Brockstein B, Poklepovic AS, Bajaj M, Babu S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus ipilimumab following anti-PD-1/L1 failure in melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2647–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. da Silva IP, Ahmed T, Reijers ILM, Weppler AM, Warner AB, Patrinely JR, et al. Ipilimumab alone or ipilimumab plus anti-PD-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma resistant to anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:836–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zimmer L, Apuri S, Eroglu Z, Kottschade LA, Forschner A, Gutzmer R, et al. Ipilimumab alone or in combination with nivolumab after progression on anti-PD-1 therapy in advanced melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2017;75:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Itzhaki O, Treves AJ, Zippel DB, Levy D, et al. Adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma: intent-to-treat analysis and efficacy after failure to prior immunotherapies. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Andersen R, Borch TH, Draghi A, Gokuldass A, Rana MAH, Pedersen M, et al. T cells isolated from patients with checkpoint inhibitor-resistant melanoma are functional and can mediate tumor regression. Ann Oncol 2018;29:1575–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fradley MG, Damrongwatanasuk R, Chandrasekhar S, Alomar M, Kip KE, Sarnaik AA. Cardiovascular toxicity and mortality associated with adoptive cell therapy and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for advanced stage melanoma. J Immunother 2021;44:86–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wolf B, Zimmermann S, Arber C, Irving M, Trueb L, Coukos G. Safety and tolerability of adoptive cell therapy in cancer. Drug Saf 2019;42:315–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang JC. Toxicities associated with adoptive t-cell transfer for cancer. Cancer J 2015;21:506–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weber JS, Yang JC, Atkins MB, Disis ML. Toxicities of immunotherapy for the practitioner. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2092–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pachella LA, Madsen LT, Dains JE. The toxicity and benefit of various dosing strategies for interleukin-2 in metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma. J Advan Pract Oncol 2015;6:212–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Santomasso B, Bachier C, Westin J, Rezvani K, Shpall EJ. The other side of CAR T-cell therapy: cytokine release syndrome, neurologic toxicity, and financial burden. Am Soc Clin Educ Book 2019;39:433–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guirguis LM, Yang JC, White DE, Steinberg SM, Liewehr DJ, Rosenberg SA, et al. Safety and efficacy of high-dose interleukin-2 therapy in patients with brain metastases. J Immunother 2002;25:82–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mehta GU, Malekzadeh P, Shelton T, White DE, Butman JA, Yang JC, et al. Outcomes of adoptive cell transfer with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for metastatic melanoma patients with and without brain metastases. J Immunother 2018;41:241–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Khair DO, Bax HJ, Mele S, Crescioli S, Pellizzari G, Khiabany A, et al. Combining immune checkpoint inhibitors: established and emerging targets and strategies to improve outcomes in melanoma. Front Immunol 2019;10:453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gestermann N, Saugy D, Martignier C, Tillé L, Marraco SAF, Zettl M, et al. LAG-3 and PD-1+LAG-3 inhibition promote anti-tumor immune responses in human autologous melanoma/T cell co-cultures. Oncoimmunol 2020;9:1736792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Donia M, Kjeldsen JW, Andersen R, Westergaard MCW, Bianchi V, Legut M, et al. PD-1+ polyfunctional T cells dominate the periphery after tumor-Infiltrating lymphocyte therapy for cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:5779–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yi M, Niu M, Xu L, Luo S, Wu K. Regulation of PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol 2021;14:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sanmamed MF, Chen L. A paradigm shift in cancer immunotherapy: from enhancement to normalization. Cell 2018;175:313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. O'Malley D, Lee S, Psyrri A, Sukari A, Thomas S, Wenham R, et al. Phase 2 efficacy and safety of autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy in combination with pembrolizumab in immune checkpoint inhibitor-naïve patients with advanced cancers. Oral presentation at: Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer Annual Meeting. November 10–14, 2021; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Davies JS, Karimipour F, Zhang L, Nagarsheth N, Norberg S, Serna C, et al. Non-synergy of PD-1 blockade with T-cell therapy in solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10:e004906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science 1996;271:1734–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bjoern J, Lyngaa R, Andersen R, Hölmich LR, Hadrup SR, Donia M, et al. Influence of ipilimumab on expanded tumour derived T cells from patients with metastatic melanoma. Oncotarget 2017;8:27062–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mullinax JE, Hall M, Prabhakaran S, Weber J, Khushalani N, Eroglu Z, et al. Combination of ipilimumab and adoptive cell therapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for patients with metastatic melanoma. Front Oncol 2018;8:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paik J. Nivolumab plus Relatlimab: First approval. Drugs 2022;82:925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Balch CM, Soong S-J, Gershenwald JE, Thompson JF, Reintgen DS, Cascinelli N, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the american joint committee on cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3622–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Larkin J, Sarnaik A, Chesney JA, Khushalani N, Kirkwood JM, Weber JS, et al. Lifileucel (LN-144), a cryopreserved autologous tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy in patients with advanced melanoma: evaluation of impact of prior anti–PD-1 therapy. Oral presentation at: American Society of Clinical Oncology. June 4–8, 2021; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sha D, Jin Z, Budczies J, Kluck K, Stenzinger A, Sinicrope FA. Tumor mutational burden as a predictive biomarker in solid tumors. Cancer Discov 2020;10:1808–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ascierto PA, Mandala M, Ferrucci PF, Rutkowski P, Guidoboni M, Arance AM, et al. SECOMBIT: The best sequential approach with combo immunotherapy [ipilimumab (I) /nivolumab (N)] and combo target therapy [encorafenib (E)/binimetinib (B)] in patients with BRAF mutated metastatic melanoma: a phase II randomized study. Ann Oncol 2021;32:S1283–S346. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Atkins MB, Lee SJ, Chmielowski B, Ribas A, Tarhini AA, Truong T-G, et al. DREAMseq (doublet, randomized evaluation in advanced melanoma sequencing): a phase III trial—ECOG-ACRIN EA6134. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:36s, (suppl. abstr. 356154). [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tarhini A, Kudchadkar RR. Predictive and on-treatment monitoring biomarkers in advanced melanoma: moving toward personalized medicine. Cancer Treat Rev 2018;71:8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lindenberg MA, Retèl VP, van den Berg JH, Geukes Foppen MH, Haanen JB, van Harten WH. Treatment with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in advanced melanoma: evaluation of early clinical implementation of an advanced therapy medicinal product. J Immunother 2018;41:413–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Epstein M, Pike R, Leire E, Middleton J, Wileman M, Ouboussad L, et al. Abstract 1508: Characterization of a novel clonal neoantigen reactive T cell (cNeT) product through a comprehensive translational research program. Cancer Res 2021;81:1508. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zippel D, Friedman-Eldar O, Rayman S, Hazzan D, Nissan A, Schtrechman G, et al. Tissue harvesting for adoptive tumor infiltrating lymphocyte therapy in metastatic melanoma. Anticancer Res 2019;39:4995–5001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Forget MA, Haymaker C, Hess KR, Meng YJ, Creasy C, Karpinets T, et al. Prospective analysis of adoptive TIL therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: response, impact of anti-CTLA4, and biomarkers to predict clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:4416–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li R, Johnson R, Yu G, McKenna DH, Hubel A. Preservation of cell-based immunotherapies for clinical trials. Cytotherapy 2019;21:943–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gastman B, Agarwal PK, Berger A, Boland G, Broderick S, Butterfield LH, et al. Defining best practices for tissue procurement in immuno-oncology clinical trials: consensus statement from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer Surgery Committee. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Watson P. The importance of tumor banking: bridging no-mans-land in cancer research. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2002;2:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Deniger DC, Kwong ML, Pasetto A, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Langhan MM, et al. A pilot trial of the combination of vemurafenib with adoptive cell therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:351–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dudley ME, Gross CA, Somerville RP, Hong Y, Schaub NP, Rosati SF, et al. Randomized selection design trial evaluating CD8+-enriched versus unselected tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for adoptive cell therapy for patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2152–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Goff SL, Rosenberg SA. BRAF inhibition: bridge or boost to T-cell therapy? Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:2682–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chaft JE, Oxnard GR, Sima CS, Kris MG, Miller VA, Riely GJ. Disease flare after tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer and acquired resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib: implications for clinical trial design. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:6298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Guo C-Y, Jiang S-C, Kuang Y-K, Hu H. Incidence of ipilimumab-related serious adverse events in patients with advanced cancer: a meta-analysis. J Cancer 2019;10:120–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Shah S, Raskin L, Cohan D, Hamid O, Freeman ML. Treatment patterns of melanoma by BRAF mutation status in the USA from 2011 to 2017: a retrospective cohort study. Melanoma Manag 2019;6:MMT31–MMT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Khushalani NI, Truong T-G, Thompson JF. Current challenges in access to melanoma care: a multidisciplinary perspective. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2021e295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kaiser AD, Assenmacher M, Schröder B, Meyer M, Orentas R, Bethke U, et al. Towards a commercial process for the manufacture of genetically modified T cells for therapy. Cancer Gene Ther 2015;22:72–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Berdeja JG. Practical aspects of building a new immunotherapy program: the future of cell therapy. Hematology 2020;2020:579–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Titov A, Zmievskaya E, Ganeeva I, Valiullina A, Petukhov A, Rakhmatullina A, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy beyond CAR T-cells. Cancers 2021;13:743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Guidance for Industry Potency Tests for Cellular and Gene Therapy Products. ( January 2011). Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/potency-tests-cellular-and-gene-therapy-products, Accessed August 17, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wang S, Sun J, Chen K, Ma P, Lei Q, Xing S, et al. Perspectives of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte treatment in solid tumors. BMC Medicine 2021;19:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jacquemin V, Antoine M, Dom G, Detours V, Maenhaut C, Dumont JE. Dynamic cancer cell heterogeneity: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lee MY, Jeon JW, Sievers C, Allen CT. Antigen processing and presentation in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. de Wolf C, van de Bovenkamp M, Hoefnagel M. Regulatory perspective on in vitro potency assays for human T cells used in anti-tumor immunotherapy. Cytotherapy 2018;20:601–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Besser MJ, Shapira-Frommer R, Treves AJ, Zippel D, Itzhaki O, Hershkovitz L, et al. Clinical responses in a phase II study using adoptive transfer of short-term cultured tumor infiltration lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:2646–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Goff SL, Smith FO, Klapper JA, Sherry R, Wunderlich JR, Steinberg SM, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte therapy for metastatic melanoma: analysis of tumors resected for TIL. J Immunother 2010;33:840–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Etxeberria I, Olivera I, Bolaños E, Cirella A, Teijeira Á, Berraondo P, et al. Engineering bionic T cells: signal 1, signal 2, signal 3, reprogramming and the removal of inhibitory mechanisms. Cell Mol Immunol 2020;17:576–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Guo W, Wang H, Li C. Signal pathways of melanoma and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021;6:424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hamilton E, Nikiforow S, Bardwell P, McInnis C, Zhang J, Blumenschein G, et al. 801 PRIME™ IL-15 (RPTR-147): Preliminary clinical results and biomarker analysis from a first-in-human Phase 1 study of IL-15 loaded peripherally-derived autologous T cell therapy in solid tumor patients. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8(Suppl 3):A479–A80. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gillison MNJ, Ulrickson M, Olson D, Stein M, Aggen D, et al. Preliminary data from TiTAN: a study of GEN-011, a neoantigen-targeted peripheral blood-derived T cell therapy with broad neoantigen targeting. Poster presented at: American Association for Cancer Research; April 8–13, 2022; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sennino BCA, Huang E, Mathur J, Ting M, Yuen B, et al. Circulating tumor-specific T cells preferentially recognize patient-specific mutational neoantigens and infrequently recognize shared cancer driver mutations. Poster presented at: American Association for Cancer Research; April 8–13, 2022; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Chmielowski B, Ejadi S, Funke R, Stallings-Schmitt T, Denker M, Frohlich MW, et al. A phase Ia/Ib, open-label first-in-human study of the safety, tolerability, and feasibility of gene-edited autologous NeoTCR-T cells (NeoTCR-P1) administered to patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:TPS3151. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gros A, Robbins PF, Yao X, Li YF, Turcotte S, Tran E, et al. PD-1 identifies the patient-specific CD8+ tumor-reactive repertoire infiltrating human tumors. J Clin Invest 2014;124:2246–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ye Q, Song DG, Poussin M, Yamamoto T, Best A, Li C, et al. CD137 accurately identifies and enriches for naturally occurring tumor-reactive T cells in tumor. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Anadon CM, Yu X, Hänggi K, Biswas S, Chaurio RA, Martin A, et al. Ovarian cancer immunogenicity is governed by a narrow subset of progenitor tissue-resident memory T cells. Cancer Cell 2022;40:545–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bianchi V, Harari A, Coukos G. Neoantigen-specific adoptive cell therapies for cancer: making T-cell products more personal. Front Immunol 2020;11:1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Moon OR, Qu Y, King MG, Mojadidi M, Chauvin-Fleurence C, Yarka C, et al. Antitumor activity of T cells expressing a novel anti-folate receptor alpha (FOLR1) costimulatory antigen receptor (CoStAR) in a human xenograft murine solid tumor model and implications for in-human studies. J Clin Oncol 2022;40(16_suppl):2535. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Sykorova M, Bao L, Chauvin-Fleurence C, Kalaitsidou M, Brocq ML, Hawkins R, et al. 199 Potent T cell costimulation mediated by a novel costimulatory antigen receptor (CoStAR) with dual CD28/CD40 signaling domains to improve adoptive cell therapies. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9(Suppl 2):A210–A. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Bonati L, Tang L. Cytokine engineering for targeted cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2021;62:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Burga R, Khattar M, Lajoie S, Pedro K, Foley C, Ocando AV, et al. 166 Genetically engineered tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (cytoTIL15) exhibit IL-2-independent persistence and anti-tumor efficacy against melanoma in vivo. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9(Suppl 2):A176–A. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Mitchell DM, Ravkov EV, Williams MA. Distinct roles for IL-2 and IL-15 in the differentiation and survival of CD8+ effector and memory T cells. J Immunol 2010;184:6719–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Wang TNJ-M, Rafail S, Carroll M, Wang R, McAlpine C, et al. Identifying MAGE-A4–positive tumors for SPEAR T-Cell therapies in HLA-A*02– eligible patients. Poster presented at: American Association for Cancer Research; April 8–13, 2022; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 105. Jones DS, 2nd, Nardozzi JD, Sackton KL, Ahmad G, Christensen E, Ringgaard L, et al. Cell surface-tethered IL-12 repolarizes the tumor immune microenvironment to enhance the efficacy of adoptive T cell therapy. Sci Adv 2022;8:eabi8075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ahmad GNJ, Ringgaard L, Christensen E, Jaegher D, Suchy J, et al. Adoptive transfer of deep IL-12 primed™ T-cells increases sensitivity to PD-L1 blockade for superior efficacy in checkpoint refractory tumors; J Immunother Cancer 2019;7(Suppl 1):P473. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Heemskerk B, Liu K, Dudley ME, Johnson LA, Kaiser A, Downey S, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with melanoma, using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes genetically engineered to secrete interleukin-2. Hum Gen Ther 2008;19:496–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Zhang L, Morgan RA, Beane JD, Zheng Z, Dudley ME, Kassim SH, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes genetically engineered with an inducible gene encoding interleukin-12 for the immunotherapy of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2278–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Jiang Y, Li Y, Zhu B. T-cell exhaustion in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Death Dis 2015;6:e1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Azoulay-Alfaguter I, Abelson M, Ritthipichai K, D'Arigo K, Hilton F, Machin M, et al. Silencing PD-1 using self-delivering RNAi PH-762- to improve Iovance TIL effector function using Gen 2 manufacturing method. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7(Suppl 1):P149. [Google Scholar]

- 111. Natarajan AVA, Wells A, Herman C, Gontcharova V, Onimus K, et al. Preclinical activity and manufacturing feasibility of genetically modified PDCD-1 knockout (KO) tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cell therapy. Poster presented at: American Association for Cancer Research; April 8–13, 2022; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 112. Ritthipichai K, Machin M, Juillerat A, Poriot L, Fardis M, Chartier C. Abstract 1052P: Genetic modification of Iovance's TIL through TALEN-mediated knockout of PD-1 as a strategy to empower TIL therapy for cancer. Ann Oncol 2020;31:S645–S71. [Google Scholar]

- 113. Palmer DC, Webber BR, Patel Y, Johnson MJ, Kariya CM, Lahr WS, et al. Internal checkpoint regulates T cell neoantigen reactivity and susceptibility to PD1 blockade. Med (N Y) 2022;3:682–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Guittard G, Dios-Esponera A, Palmer DC, Akpan I, Barr VA, Manna A, et al. The CISH SH2 domain is essential for PLC-γ1 regulation in TCR stimulated CD8(+) T cells. Sci Rep 2018;8:5336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Palmer DC, Guittard GC, Franco Z, Crompton JG, Eil RL, Patel SJ, et al. Cish actively silences TCR signaling in CD8+ T cells to maintain tumor tolerance. J Exp Med 2015;212:2095–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Schlabach M, Colletti N, Hohmann A, Wrocklage C, Gannon H, Falla A, et al. Abstract 2175: KSQ-001: A CRISPR/Cas9-engineered tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (eTILTM) therapy for solid tumors. Cancer Res 2020;80:2175.32066565 [Google Scholar]

- 117. Whelan S, Gosling J, Mani M, Cohen F, Tenn-McClellan A, Powers J, et al. 98 NX-0255, a small molecule CBL-B inhibitor, expands and enhances tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) for use in adoptive cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2021;9(Suppl 2):A107–A. [Google Scholar]

- 118. Creelan BC, Wang C, Teer JK, Toloza EM, Yao J, Kim S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte treatment for anti-PD-1-resistant metastatic lung cancer: a phase 1 trial. Nat Med 2021;27:1410–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Jazaeri AA, Zsiros E, Amaria RN, Artz AS, Edwards RP, Wenham RM, et al. Safety and efficacy of adoptive cell transfer using autologous tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (LN-145) for treatment of recurrent, metastatic, or persistent cervical carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2538. [Google Scholar]

- 120. Figlin RA, Thompson JA, Bukowski RM, Vogelzang NJ, Novick AC, Lange P, et al. Multicenter, randomized, phase III trial of CD8(+) tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in combination with recombinant interleukin-2 in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Freedman RS, Edwards CL, Kavanagh JJ, Kudelka AP, Katz RL, Carrasco CH, et al. Intraperitoneal adoptive immunotherapy of ovarian carcinoma with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and low-dose recombinant interleukin-2: a pilot trial. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol 1994;16:198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Pich O, Muiños F, Lolkema MP, Steeghs N, Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. The mutational footprints of cancer therapies. Nat Genet 2019;51:1732–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Turcotte S, Gros A, Hogan K, Tran E, Hinrichs CS, Wunderlich JR, et al. Phenotype and function of T cells infiltrating visceral metastases from gastrointestinal cancers and melanoma: implications for adoptive cell transfer therapy. J Immunol 2013;191:2217–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Fernandez-Poma SM, Salas-Benito D, Lozano T, Casares N, Riezu-Boj JI, Mancheño U, et al. Expansion of Tumor-infiltrating CD8(+) T cells expressing PD-1 improves the efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy. Cancer Res 2017;77:3672–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Jing W, Gershan JA, Blitzer GC, Palen K, Weber J, McOlash L, et al. Adoptive cell therapy using PD-1(+) myeloma-reactive T cells eliminates established myeloma in mice. J Immunother Cancer 2017;5:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Zacharakis N, Huq LM, Seitter SJ, Kim SP, Gartner JJ, Sindiri S, et al. Breast cancers are immunogenic: immunologic analyses and a phase II pilot clinical trial using mutation-reactive autologous lymphocytes. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:1741–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Rosenberg SA, Yannelli JR, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, Weber JS, et al. Treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma with autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin 2. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994;86:1159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Schwartzentruber DJ, Hom SS, Dadmarz R, White DE, Yannelli JR, Steinberg SM, et al. In vitro predictors of therapeutic response in melanoma patients receiving tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:1475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Dudley ME, Gross CA, Langhan MM, Garcia MR, Sherry RM, Yang JC, et al. CD8+ enriched "young" tumor infiltrating lymphocytes can mediate regression of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:6122–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Radvanyi LG, Bernatchez C, Zhang M, Fox PS, Miller P, Chacon J, et al. Specific lymphocyte subsets predict response to adoptive cell therapy using expanded autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:6758–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Girda E, Zsiros E, Nakayama J, Whelan S, Nandakumar S, Rogers S, et al. A phase 1 adoptive cell therapy using drug-enhanced, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, DeTIL-0255, in adults with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:TPS5602. [Google Scholar]

- 132. Svane IM, Cervera-Carrascon V, Santos JM, Havunen R, Sorsa S, Donia M, et al. First-in-human clinical trial of an oncolytic adenovirus armed with TNFa and IL-2 in patients with advanced melanoma receiving adoptive cell transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:TPS9590. [Google Scholar]

- 133. Svane IM, Cervera-Carrascon V, Santos JM, Havunen R, Sorsa S, Donia M, et al. First-in-human- clinical trial of an oncolytic adenovirus armed with TNFa and IL-2 in patients with advanced melanoma receiving adoptive cell transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Poster presented at: The American Society of Clinical Oncology. June 3–7, 2022, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 134. Jamal-Hanjani M, Greystoke A, Thistlethwaite F, Summers YJ, Allison J, Cave J, et al. An open-label, multicenter phase I/IIa study evaluating the safety and clinical activity of clonal neoantigen reactive T cells in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (CHIRON). J Clin Oncol 2021;39:TPS9138. [Google Scholar]

- 135. van der Kooij MK, Verdegaal EME, Visser M, de Bruin L, van der Minne CE, Meij PM, et al. Phase I/II study protocol to assess safety and efficacy of adoptive cell therapy with anti-PD-1 plus low-dose pegylated-interferon-alpha in patients with metastatic melanoma refractory to standard of care treatments: the ACTME trial. BMJ Open 2020;10:e044036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. MH Geukes Foppen, Donia M, Borch TH, Ö Met, Blank CU, Pronk L, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing non-myeloablative lymphocyte depleting regimen of chemotherapy followed by infusion of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2 to standard ipilimumab treatment in metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:TPS9592. [Google Scholar]

- 137. Lövgren T, Wolodarski M, Wickström S, Edbäck U, Wallin M, Martell E, et al. Complete and long-lasting clinical responses in immune checkpoint inhibitor-resistant, metastasized melanoma treated with adoptive T cell transfer combined with DC vaccination. Oncoimmunol 2020;9:1792058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Sukumaran S, Kalaitsidou M, Mojadidi M, Yarka C, Ouyang Y, Gschweng E, et al. 198 Costimulatory antigen receptor (CoStAR): a novel platform that enhances the activity of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). J Immunother Cancer 2021;9(Suppl 2):A209. [Google Scholar]

- 139. Palmer D, Webber B, Patel Y, Johnson M, Kariya C, Lahr W, et al. 333 Targeting the apical intracellular checkpoint CISH unleashes T cell neoantigen reactivity and effector program. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8(Suppl 3):A204. [Google Scholar]

- 140. Crowther MD, Westergaard MCW, Debnam P, Anderson V, Pope GR, Schmidt E, et al. Next-generation, inducible IL-7–expressing, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes by lentiviral vector genetic modification for clinical application. Poster presented at: American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy; May 16–19, 2022; Hybrid, Washington DC, USA. [Google Scholar]