Abstract

Background and Aims

Intraspecific variability in leaf water-related traits remains little explored despite its potential importance in the context of increasing drought frequency and severity. Studies comparing intra- and interspecific variability of leaf traits often rely on inappropriate sampling designs that result in non-robust estimates, mainly owing to an excess of the species/individual ratio in community ecology or, on the contrary, to an excess of the individual/species ratio in population ecology.

Methods

We carried out virtual testing of three strategies to compare intra- and interspecific trait variability. Guided by the results of our simulations, we carried out field sampling. We measured nine traits related to leaf water and carbon acquisition in 100 individuals from ten Neotropical tree species. We also assessed trait variation among leaves within individuals and among measurements within leaves to control for sources of intraspecific trait variability.

Key Results

The most robust sampling, based on the same number of species and individuals per species, revealed higher intraspecific variability than previously recognized, higher for carbon-related traits (47–92 and 4–33 % of relative and absolute variation, respectively) than for water-related traits (47–60 and 14–44 % of relative and absolute variation, respectively), which remained non-negligible. Nevertheless, part of the intraspecific trait variability was explained by variation of leaves within individuals (12–100 % of relative variation) or measurement variations within leaf (0–19 % of relative variation) and not only by individual ontogenetic stages and environmental conditions.

Conclusions

We conclude that robust sampling, based on the same number of species and individuals per species, is needed to explore global or local variation in leaf water- and carbon-related traits within and among tree species, because our study revealed higher intraspecific variation than previously recognized.

Keywords: Intraspecific trait variability, tropical tree, Paracou, water-related traits, virtual and field sampling

INTRODUCTION

Intraspecific variability in leaf water-related traits remains little explored despite its possible importance in the context of increasing drought frequency and severity (Hajek et al., 2016), and there is growing interest in gaining a better understanding of its role in ecological processes (Westerband et al., 2021). In the effort to measure traits across large numbers of species to identify general patterns and trade-offs, functional variability of plants has been analysed frequently at the species and community levels by using mean values (Díaz et al., 2016; Bruelheide et al., 2018). However, recent literature on intraspecific trait variability (ITV) suggests that species have the potential to exhibit extensive ITV (Albert et al., 2011; Siefert et al., 2015; Umaña et al., 2018; Schmitt et al., 2020). For instance, studies on the role of intraspecific variability in community assembly revealed its effects on environmental filtering (Messier et al., 2010; Paine et al., 2011), with shifts in trait values along environmental and resource gradients (Jung et al., 2014; Siefert and Ritchie, 2016). ITV consistently accounts for a significant proportion of the total within- and among-community trait variation (25 and 32 %, respectively) in whole-plant traits and leaf economic traits including leaf chemical traits, specific leaf area and leaf dry matter content (Siefert et al., 2015).

Individuals within a species can have highly variable trait values, even ≤42 % in hydraulic traits (Rosas et al., 2019), and consequently, assigning mean trait values to species without considering the spatial or temporal variability of those traits at the intraspecific scale could lead to inaccuracies. One risk is to exaggerate interspecific variation, underestimating niche overlap and breadth (Violle, 2012), resulting in false assumptions on the underlying mechanisms that shape biodiversity functioning. In addressing the question of ITV, past studies have mainly focused on tree height (e.g. Vieilledent et al., 2010) and vegetative traits such as leaf morphology and leaf nutrient concentration (e.g. Messier et al., 2010). There is a need to investigate ITV in other traits in order to have a more complete understanding of trait covariance patterns, such as plant water-related traits (but see Rosas et al., 2019).

Given that more frequent and intense droughts are predicted in the Amazon Basin (IPCC, 2021), current research regarding the physiological mechanisms underlying the effects of drought focuses on the water relationships of plants, including how they maintain their water balance and turgor (e.g. Levionnois et al., 2020). Water availability conditions the functioning of the plant and, indirectly, its growth, thus being a key determinant to explain the distribution of species at both local and regional scales (Brodribb et al., 2020). Given that physiological responses often involve suites of interrelated traits, because single traits might describe only part of a physiological process (Goud & Sparks, 2018), studies on water-related traits are progressively using a multi-trait approach to provide an integrative understanding of the responses of individuals to their environment (Laanisto & Niinemets, 2015; Guillemot et al., 2022; McCulloh et al., 2023). Indeed, functional traits do not vary independently, but show covariations in ecological strategies among individuals (Schmitt et al., 2020), species (Díaz et al., 2016) and communities (Bruelheide et al., 2018) along economics spectra of leaves (Wright et al., 2004), wood (Chave et al., 2009) or stature recruitment (Rüger et al., 2020). It is therefore crucial to take water-related traits into account to gain a better understanding of ecosystem dynamics in the context of climate change, but individual variation in leaf water-related traits remains underexplored.

Intraspecific trait variation results from genetic variation, through local adaptation, and variation in trait expression within individuals, through phenotypic plasticity (Westerband et al., 2021). ITV is therefore shaped by local adaptation and phenotypic plasticity of traits along abiotic environmental gradients and in response to biotic interactions within species composing the local community (Albert et al., 2011). However, how to make a proper comparison between intra- and interspecific variation in traits remains unclear or neglected, resulting in an inconsistent methodology that prevents a current global understanding of the importance of ITV. Many studies estimate ITV from very few individuals, and there is no consensus regarding the scale at which within- vs. among-species ITV is separated (Westerband et al., 2021). Albert et al. (2011) suggested cases when integrating ITV is necessary and suggested the use of the coefficient of variation (CV) and variance partitioning (VP) using linear mixed models to estimate ITV. Through a literature review, Yang et al. (2020) showed that the CV was a common method to quantify ITV. VP is widely used to determine the contribution of species and individuals to the observed trait variance (Blonder et al., 2017; Ávila-Lovera et al., 2022). But regarding the sampling strategy, the literature remains unclear and, to the best of our knowledge, does not question the effect of sampling design on the correct assessment of among- vs. within-species variability. Researchers are mostly told to focus their efforts on increasing the sample size of individuals per species in order to improve the estimation of ITV per se [e.g. Hulshof et al. (2010) recommended sampling 20 individuals per species]. But the methodology did not question the relationship between sampled species and individuals (i.e. the ratio of species to individuals), despite the importance of sample size in statistical methods such as linear mixed models, thus impeding meta-analyses. Moreover, the reality of the fieldwork and laboratory work can constrain sampling size owing to limitations in time, budget and human resources. Although increased sampling intensity leads to a more accurate estimate of the variance and mean of trait values, missions must also be cost-effective (for a cost–benefit analysis of sampling designs, see Baraloto et al., 2010). We therefore need to choose the most appropriate sampling design in the field depending on the research question, in order to take into account inter- or intraspecific variation, or both.

In this study, we initially investigated the most robust strategy to compare local intra- and interspecific trait variability using a virtual experiment. We then used the identified sampling design to assess variation in the values of water- and carbon-related leaf functional traits of individual trees within and among species. We also measured the variation in functional traits among leaves within trees and among measurements within leaves. We analysed the leaf traits of a large number of individuals [105 trees measuring >10 cm in diameter at breast height (DBH)] belonging to ten Neotropical tree species in a highly diverse tropical forest site located within the Amazon Basin. Combining virtual experiments and functional leaf traits, we used CVs and VP using linear mixed models to answer the following questions:

What is the most robust sampling design to compare local intra- and interspecific trait variability?

What is the relative and absolute importance of variation in water- and carbon-related leaf traits within and among species?

What is the relative importance of within-tree leaf variation and measurement error in variation in water- and carbon-related leaf traits?

Mathematically, we expected that a sampling design with an equal number of species and individuals per species (i.e. a ratio of species to individuals equal to one) would reduce the bias in the estimation of the ratio between inter- and intraspecific variation in traits. We hypothesized high intraspecific variability for water- and carbon-related traits, as already demonstrated for carbon-related leaf traits (Schmitt et al., 2020). Nevertheless, water-related leaf traits are often considered to have low intraspecific variability, despite being poorly studied (Westerband et al., 2021). We assumed that within-tree leaf variation and measurement error were low for most leaf traits, with the exception of traits known to vary widely within individuals, such as leaf area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virtual experiment

We tested three strategies virtually, in order to compare local intra- and interspecific trait variability or how sampling design affects the assessment of trait variation across study levels (Supplementary data Fig. S1). We simulated one trait for 100 species with mean trait values sampled according to a ten-centred normal distribution with an interspecies trait variance of one, each including 100 individuals per species with trait values sampled according to a species-centred normal distribution with an intraspecies trait variance of one. We carried out 100 repetitions of three different virtual sampling strategies on virtual data: (1) sampling 100 individuals favouring species variation (25 species with four individuals per species); (2) sampling 100 individuals favouring individual variation (four species with 25 individuals per species); and (3) sampling 100 individuals evenly distributed across species and individuals (ten species with ten individuals per species). We used CVs and VP from linear mixed models to assess intra- and interspecific variation as described below for each sampling strategy and replicate. For each sampling strategy and index, we measured the bias (difference between the observed median and the expected value) and s.d. between replicates.

Study site

The study was conducted in the Guiana Shield, in the coastal region of French Guiana. All trees were sampled at the Paracou field station (5°18ʹN, 52°53ʹW), except for one individual of Virola surinamensis sampled at the agronomy campus in Kourou (5°17ʹN, 52°65ʹW). That individual was used to compare measurement error with within-tree leaf variation. The Paracou field station is characterized by an average annual rainfall of 3041 mm and an average air temperature of 25.71 °C (Aguilos et al., 2018). An exceptionally rich natural tropical forest occupies this lowland area characterized by heterogeneous microtopographic conditions, with numerous small hills generally not exceeding 45 m in elevation (Gourlet-Fleury et al., 2004). The site includes a 6.25 ha plot and a 25 ha plot with trees mapped to the nearest metre and censused (>10 cm DBH) every 5 years since 1991.

Field samplings

Based on the results of the virtual sampling, we conducted a field sampling, in which we compared measurement error, within-tree leaf variation and intra- and interspecific variation in leaf traits (Table 1; Supplementary data Fig. S2). We measured repeatedly ten times, five to ten samples per trait from one individual of Virola surinamensis (Rol. ex Rottb.) Warb at the agronomy campus to compare measurement error with within-tree leaf variation. We measured ten samples per trait from ten individuals of Virola michelii Heckel at the Paracou field stations to compare within-tree leaf variation with intraspecific variation. Finally, we measured one sample per trait from ten individuals per species of ten species to compare intra- and interspecific variation in leaf traits (Table 1; Supplementary data Fig. S2). A sample consisted of one to three leaves depending on the trait, and a measurement concerned either the whole leaf or a portion of the leaf (see Trait measurements subsection below). Measurements on punctual parts of the leaf were randomly distributed three times on either side of the primary vein.

Table 1.

Sampling effort per pair of study levels for each measured trait. The pairs of study levels vary in the number of species, individual trees, samples and measures. For a scheme of the field sampling, see Supplementary data Fig. S2.

| Study levels | Species | Trees | Samples | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra- vs. interspecific variation | 10 | 103 | 103 | 103 |

| Within-tree leaf vs. intraspecific variation | 1 | 4 | 40 | 40 |

| Measurement error vs. within-tree leaf variation | 1 | 1 | 10 | 100 |

We selected ten tree species well spread out in the phylogeny to achieve a good representation of the evolutionary history of trait variations across levels (Supplementary data Fig. S3): Casearia javitensis Kunth, Chrysophyllum prieurii A.DC., Conceveiba guianensis Aubl., Gustavia hexapetala Aubl., Jacaranda copaia subsp. copaia Aubl., Laetia procera (Poepp.) Eichler, Protium stevensonii (Standl.) Daly, Tachigali melinonii (Harms) Zarucchi & Herend, Virola michelii Heckel and Virola surinamensis (Rol. ex Rottb.) Warb. We selected ten individuals per species and minimized the variation in diameter (Supplementary data Table S1) to limit among-individual variability attributable to tree ontogeny and access to light (Schmitt et al., 2020). For each individual, we collected healthy, mature leaves on a branch exposed to light from the upper crown of a canopy tree. For every sample, we assessed the height and the Dawkins index (a light index) for both the sampled tree and the branch (Dawkins, 1958). We kept the samples humidified with moist paper in ziplock bags that were previously exhaled into, such that high CO2 and humidity would render transpiration negligible (Guyot et al., 2012). Samples were placed in the dark and kept in a cooler for transport until measurements back in the laboratory on the same day.

Trait measurements

We measured eight leaf functional traits that relate to resource investment strategies through light interception and carbon assimilation (Wright et al., 2004) or hydraulic functioning (Rosas et al., 2019), with known roles in individual variation (Rosas et al., 2019; Schmitt et al., 2020): leaf area (LA; in centimetres squared), specific leaf area (SLA; in centimetres squared per gram), leaf fresh thickness (LT; in micrometres), leaf chlorophyll content (CC, in grams per centimetre squared), leaf dry matter content (i.e. leaf dry weight divided by fresh weight, LDMC; in grams per gram), leaf saturated water content (LSWC; in grams per gram), leaf water potential at which leaf cells lose turgor (πTLP, in megapascals) and leaf minimum conductance (gmin; in millimoles per metre squared per second).

Leaf petioles, rachises and petiolules were removed for SLA, LDMC, LT, LA and CC. Leaf fresh weight was measured with a digital balance at a precision of 0.001 g (Wensar, KD-H600), LT using a micrometre (Digit Outside Micrometre 193-101, Mitutoyo, Japan), LA by analysing scanned images of fresh leaves with ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012), and leaf chlorophyll content was determined with a SPAD-502 instrument converted with an allometric model using the general homographic model for all species (Coste et al., 2010). Leaves were oven-dried for ≥72 h at 60° C before measurement of dry weight to obtain LDMC and SLA. We assessed πTLP using an established linear relationship for tropical trees (Bartlett et al., 2012; Maréchaux et al., 2016) with the osmotic potential at full hydration, which was measured directly with a vapour pressure osmometer (Vapro 5600, Wescor, Logan, UT, USA). Samples were left overnight for rehydration in the refrigerator at 4 °C. We extracted one leaf disc between the midrib and margin with a 5-mm-diameter cork borer, excluding primary and secondary veins (Kikuta and Richter, 1992). The discs were frozen in liquid nitrogen for ≥2 min, punctured 10–15 times with a safety pin and sealed in the osmometer chamber, using the standard chamber wells. We calculated LSWC based on saturated and dry weights (Barrs and Weatherley, 1962). We obtained saturated weights by rehydrating the leaves for 24 h in the dark at a low temperature (4 °C), and dry weights by drying leaves for ≥72 h at 60 °C (Sapes and Sala, 2021). We determined gmin from the consecutive weight loss of desiccating leaves that were sealed with nail polish on cut petioles (Kerstiens, 1996; Sack and Scoffoni, 2011). We weighed the leaves at regular intervals, twice at 15 min intervals and then each 30 min during 3 h. The leaves were left to dry overnight and were weighed twice the next morning. The air temperature and humidity were monitored using a digital thermo-hygrometer (Fisherbrand™ Traceable™ Relative Humidity/Temperature Meters). The slope of the curve of weight loss vs. time was estimated using only the linear part of the regression ( > 0.95), which usually included the points after hours of dehydration, suggesting maximal stomatal closure (Billon et al., 2020). Note that owing to limited resources, our gmin measurements have several caveats: (1) the leaves were not kept in complete darkness; (2) the abaxial side was less exposed than the adaxial side of the leaf; (3) we used only a limited number of points to determine the linear part of the curve; and (4) the vapour pressure deficit was not measured directly. However, our protocol is the same as recently published ones (e.g. Levionnois et al., 2021).

Analyses

We used two complementary analyses to understand the source and magnitude of trait variability: the CV gives an absolute variation of the intraspecific trait with respect to the interspecific mean, whereas the VP with linear mixed models gives a relative variation of each level studied.

We used linear mixed models for every trait and each pair of levels studied: (1) measurement error (i.e. measurement repetitions among leaves sampled on one tree of one species); (2) within-tree leaf variation (i.e. leaf repetitions among several trees within one species); and (3) intra- and interspecific variation (i.e. individual repetitions among species) (Supplementary data Fig. S2). We set as random effects the upper level studied in each pair, subsampling if necessary to obtain a balanced design in each case (i.e. 25 measures repeated among five leaves, 100 leaves among ten individuals, and 100 individuals among ten species). For example, for intra- and interspecific variation, we estimated the among-species variance in our trait of interest from comparison of the observed variance within and among species. In this case, species are considered as random effects:

| (1) |

with each trait value at individual level in each species following a normal distribution centred on species means μspecies of variance σ. Species means μspecies themselves follow a normal distribution centred on mean trait value μ of variance σspecies.

We used the CV for every trait per species. The CV is defined as the ratio of the s.d. to the mean (CV1 = σ/μ), expressed as a percentage. The CV is convenient to compare variation of traits among species as it requires no ad hoc assumptions and is unitless. Following Yang et al. (2020), we used Bao’s estimator (CV4), which is best suited after a logarithic transformation.

Finally, given that ontogeny and light access are two key determinants of individual leaf variation, we reproduced the model of Schmitt et al. (2020) to investigate the joint effect of tree size, related to ontogeny and access to light, and topographic position, related to availability of water and nutrients. The DBH (in centimetres) was chosen to control for tree size and access to light. The DBH values of the sampled individuals were extracted from the 2020 inventory of the permanent plots in Paracou (Supplementary data Table S1). The topographic wetness index (TWI) was selected as a proxy for water accumulation and is defined by the cell catchment area (i.e. the cumulative upslope areas draining through the cell) divided by the local slope, thus representing a relative measure of soil moisture availability (Kopecký and Čížková, 2010). The TWI was derived at 1 m resolution from a digital elevation model at 1 m resolution using SAGA-GIS (Conrad et al., 2015) based on a LiDAR campaign conducted in 2015.

All traits were normalized using the natural logarithm of the absolute value of the trait {ln[abs(Trait)]}. We used R v.3.6 for all statistical analyses (R Core Team, 2020).

RESULTS

Virtual assessment of sampling strategies

We tested virtually the most robust strategy to compare intra- and interspecific trait variability, and both the CV and the VP were estimated best with unbalanced sampling favouring individuals (the difference between the observed median and the true value for CV and VP respectively was bCV = 0.2 % and bVP = −0.3 %; Fig. 1), but balanced sampling was very close and had less uncertainty (s.d.CV = 0.9 % and s.d.VP = 14.4 %). Unbalanced sampling favouring species biased the CV and the VP towards lower values of intraspecific variation (bCV = −0.4 % and bVP = −1.9 %). Consequently, balanced sampling seemed the best strategy to assess trait variation in the community among and within species, with both CV and VP, and was used for the field sampling.

Fig. 1.

Effect of the sampling strategy on coefficient of variation (CV) and variance partitioning in the virtual experiment. (A) Coefficients of variation were calculated using Bao’s estimator and obtained 100 times for every sampling strategy. (B) Variance partitioning was calculated using linear mixed models and obtained 100 times for every sampling strategy. Sampling strategies included four individuals in 25 species (unbalanced sampling favouring species), 25 individuals in four species (unbalanced sampling favouring individuals) and ten individuals in ten species (balanced). The dashed line represents the true value based on the full community of 100 individuals in 100 species. Labels indicate biases (b, difference between the observed median and the true value) and the s.d. between replicates. The percentage of variance of species is represented in red and that of individuals in green.

Observed variations in leaf traits among species, individuals, leaves and measurements

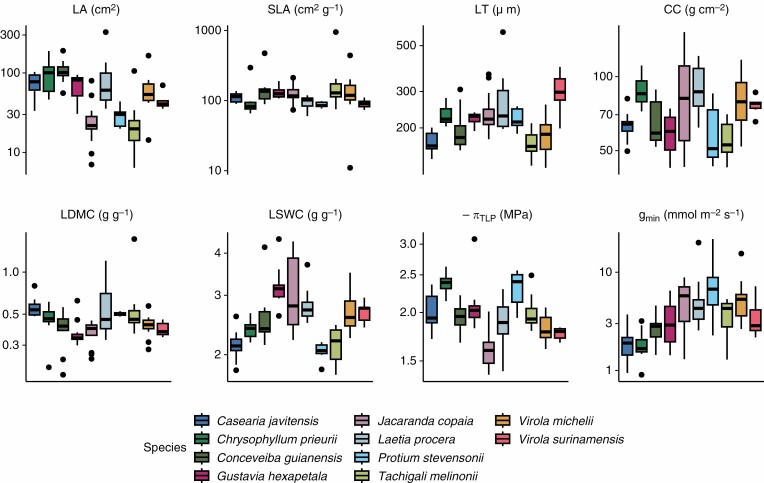

We observed a large variation in tree trait values among the ten species sampled in the field, with a variation of 2.0- to 10.1-fold using the 5th and 95th quantiles of trait distributions (for πTLP and LA, respectively; Fig. 2). Conversely, we observed less variation in sample trait values among trees of the same species sampled in the field, with variation of 1.3- to 4.0-fold using the 5th and 95th quantiles of trait distributions (for πTLP and gmin, respectively; Supplementary data Fig. S4). Finally, we observed little variation in measurement values for traits among leaves of the same individual tree sampled in the field, with 1.1- to 1.4-fold variation using the 5th and 95th quantiles of trait distributions (for πTLP and gmin, respectively; Supplementary data Fig. S5).

Fig. 2.

Variation in individual tree traits among species based on field sampling for each trait with units. Leaf traits include specific leaf area (SLA), leaf dry matter content (LDMC), leaf fresh thickness (LT), leaf area (LA), leaf chlorophyll content (CC), leaf saturated water content (LSWC), leaf water potential at which leaf cells lose turgor (πTLP) and leaf minimum conductance (gmin). The trait values shown on the y-axis are log-transformed to better meet the normality assumption used in the coefficient of variation and in variance partitioning.

The CV of leaf traits across species (Fig. 3) was mostly low to moderate and non-negligible (13–16 %), but high for gmin and LDMC (44 and 33 %, respectively) and low for LT, CC and LA (4, 5 and 8 %, respectively). LDMC showed a strong variation in the CV among species (from 4 % with P. stevensonii to 76 % with T. melinonii).

Fig. 3.

Intraspecific coefficient of variation (CV) for leaf traits across species from field sampling. The CVs were calculated using Bao’s estimator. Leaf traits include specific leaf area (SLA), leaf dry matter content (LDMC), leaf fresh thickness (LT), leaf area (LA), leaf chlorophyll content (CC), leaf saturated water content (LSWC), leaf water potential at which leaf cells lose turgor (πTLP) and leaf minimum conductance (gmin). Points represent species values, with their colour indicating species identity.

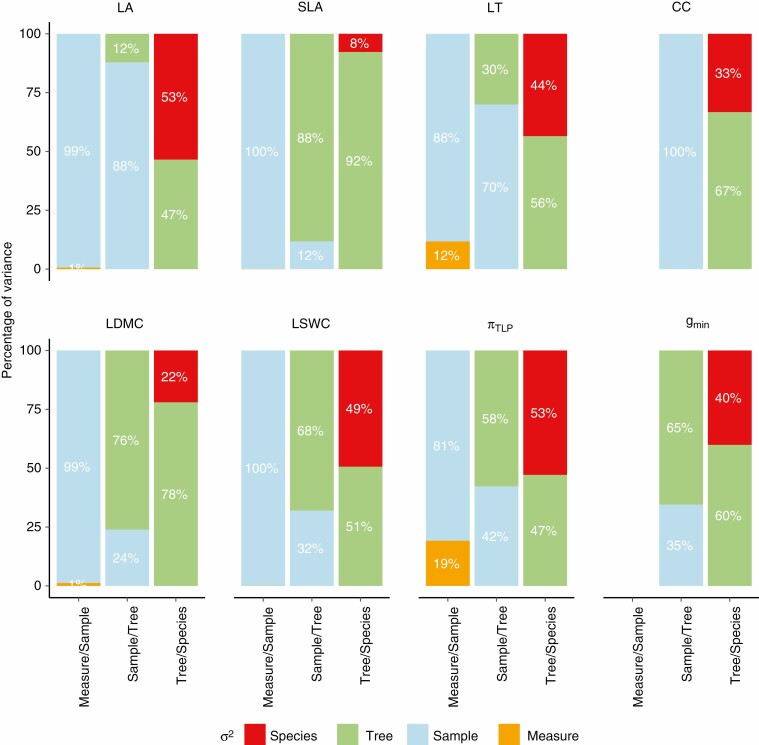

Variance partitioning of leaf traits (Fig. 4) revealed overall both strong interspecific variation (33–53 %), except for SLA and LDMC (8 and 22 %, respectively), and strong intraspecific variation (47–92 %). When sampling only healthy mature leaves on a branch exposed to light, leaf trait intraspecific variation is mostly attributable to the individual tree (55–88 %), except for a strong variability across samples within trees for LA and CC (88 and 100 %, respectively). Leaf trait intrasample variation is almost only attributable to sample (81–100 %), except for a non-negligible measure error within sample for LT and πTLP (12 and 19 %, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Variance partitioning of leaf traits across study levels from field sampling. Variance partitioning was obtained using linear mixed models for every trait and each pair of levels studied: measurement error [i.e. measurement repetitions (orange) among leave samples (blue)], within-tree leaf variation [i.e. leaf sample repetitions (blue) among trees (green)] and intra- and interspecific variation [i.e. individual repetitions (green) among species (red)]. Leaf traits include specific leaf area (SLA), leaf dry matter content (LDMC), leaf fresh thickness (LT), leaf area (LA), leaf chlorophyll content (CC), leaf saturated water content (LSWC), leaf water potential at which leaf cells lose turgor (πTLP) and leaf minimum conductance (gmin).

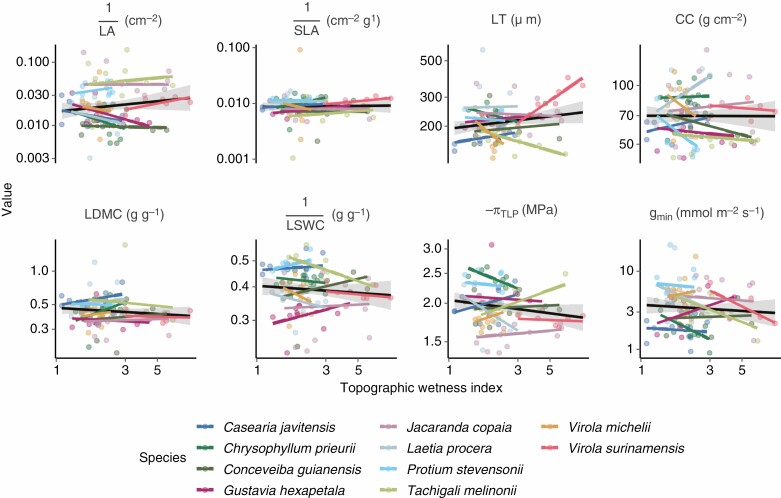

As expected, we found a global positive effect of diameter, related to light access and tree size, on individual trait values within species following a Michaelis–Menten model (Supplementary data Figs S6 and S7), with species faster to reach their mature value (e.g. Jacaranda copaia for πTLP). However, we found no significant effect of topography both among and within species (Fig. 5; Supplementary data Fig. S8). Yet, πTLP and gmin showed species with significant positive or negative within-species association to topography (e.g. T. melinonii with positive variation of πTLP along the TWI; Fig. 5; Supplementary data Fig. S8).

Fig. 5.

Variation of individual tree traits along the topographic wetness index among and within species, based on field sampling for each trait with units. Leaf traits include specific leaf area (SLA), leaf dry matter content (LDMC), leaf fresh thickness (LT), leaf area (LA), leaf chlorophyll content (CC), leaf saturated water content (LSWC), leaf water potential at which leaf cells lose turgor (πTLP) and leaf minimum conductance (gmin). The trait and topographic wetness index values shown on the x- and y-axes are log-transformed. The black line represents the average linear regression between species, and the coloured lines represent the linear regression within each species. See Supplementary data Fig. S8 for the effect of the topographic wetness index on trait values using the model replicated from the study by Schmitt et al. (2020).

DISCUSSION

Using the most robust sampling, based on a balanced number of individuals per species and species, we conclude that robust sampling is needed in future studies to compare global or local variation in leaf water- and carbon-related traits within and among tree species, revealing higher intraspecific variation than previously recognized. We make recommendations for future studies and discuss the drivers and consequences of intraspecific variation.

Recommendations for studies comparing intra- and interspecific trait variability

Choosing the most appropriate sampling design and methodology to compare intra- and interspecific trait variability correctly can be a challenging task owing to limitations in time, budget and human resources. Here, we suggest using robust sampling to explore variation in traits within and among species, based on balanced numbers of individuals per species and species, combined with analyses using CVs and VP based on linear mixed models.

The sampling design will depend mainly on the objective of the study, with a focus on species sample size in community ecology (e.g. Díaz et al., 2016) or a focus on individual sample size in population ecology (e.g. Schmitt et al., 2020). But we argue that studies based on unbalanced sampling designs favouring species or individuals should not make claims about the relative importance of intra- vs. interspecifc trait variability, contrary to what is currently done in the literature (e.g. Le Bagousse-Pinguet et al., 2014). Indeed, studies such as the one by Le Bagousse-Pinguet et al. (2014), with a sampling design favouring species (five individuals for >20 species per grassland), might bias their estimate of intraspecific variability to lower values (Fig. 1), whereas studies such as the one by Schmitt et al. (2020), with a sampling design favouring individuals (17–232 individuals per species for five species), might result in higher uncertainties in their estimate of intraspecific variability (Fig. 1). As a consequence, Le Bagousse-Pinguet et al. (2014) reported low ITV in grasslands, 13.5–33.6 %, for specific leaf area and leaf dry matter content, whereas the data of Schmitt et al. (2020) show high ITV in forests, 60–81 %, for the same traits. Our results suggest that a more robust estimate of ITV for both studies could be obtained by subsampling data in species and individuals per species to obtain a balanced sampling design.

For the virtual experiment, we simulated one trait for 100 species with mean trait values sampled according to a ten-centred normal distribution with an interspecies trait variance of one, each including 100 individuals per species with trait values sampled according to a species-centred normal distribution with an intraspecies trait variance of one. This virtual experiment oversimplifies reality in several respects: (1) most traits observed in this study are positively defined and show a distribution closer to the lognormal distribution than to the normal distribution; (2) the species community mean and variance are defined arbitrarily; and (3) all species have equal intraspecific variance arbitrarily defined, whereas most trait values observed in this study vary differently between species. Nevertheless, most studies transform trait values to meet the normality assumption, which resolves the first oversimplification. Second, using VP, we focused on the ratio of intraspecific to interspecific variation being equal to 1:1, which overestimated intraspecific variation relative to observation in most traits (LT, CC, LDMC and gmin). However, given that the ratio is often unknown, balanced sampling seems to be the most appropriate a priori. Thus, even assuming an oversimplified model, the results show the relevance of balanced sampling for assessing intraspecific variation. Future virtual experiments could modify the ratio to assess the change in bias in different sampling strategies and use varying intraspecific variances.

Once the sampling design is established, the question of the statistical method to estimate ITV arises. If the sampling design is unbalanced, a subsampling can be done associated with bootstrapping to generate uncertainties in the estimate of ITV. As already suggested by Albert et al. (2011), we argue for the use of CVs and VP based on linear mixed models, but in association and not separately as currently done in the literature (e.g. Le Bagousse-Pinguet et al., 2014, among others, report only VP). The CV gives an absolute variation of the intraspecific trait with respect to the interspecific mean, whereas the VP with linear mixed models gives the relative variation of each level studied. Thus, they provide complementary information. For instance, the high individual relative variability with SLA (VP = 92 %) is attributable to the weak absolute variability of species more than intraspecific absolute variability (CV = 8 %). Moreover, the CV and VP allow comparisons of the distribution of trait values from different units as a percentage, offering a way to compare variation among species directly, independently of their abundances (Helsen et al., 2017), thus facilitating meta-analyses.

Our study focused on eight traits separately, but multi-trait approaches are paramount to understand ecological processes because single traits might describe only part of a physiological process (Goud & Sparks, 2018). We repeated the virtual experiment using a multinormal law to generate trait values for eight traits in 100 species, each including 100 individuals. A classic first analysis in multi-trait approaches is the investigation of trait coordination with ordinations such as principal component analyses (e.g. Díaz et al., 2016). We therefore examined the effect of sampling design on the estimation of correlations between pairs of traits (results not shown), resulting in the same recommendation as for single-trait approaches: the most robust sampling design uses balanced sampling of species and individuals per species.

Finally, we explored which sampling design was the most appropriate to compare intra- and interspecific trait variability using field and virtual samplings to test our hypotheses. Common gardens are also a fundamental tool to partition genetic and environmental components of trait variation, which is often difficult and not fully partitionable in the field. Common gardens can test the hypothesis of whether species respond to environmental variations through phenotypic plasticity or local adaptation. If phenotypic differences persist among different genotypes in the same environmental conditions, then genetic bases are driving the responses of species to the environment, potentially revealing local adaptation attributable to an adaptive strategy. Reciprocal transplant experiments, an extension of the common garden approach in which individuals are transplanted between home and away habitats, are the gold standard for detecting local adaptation (Johnson et al., 2022). Along with common gardens, genetic variation can also be analysed directly within and among species using molecular marker analyses (e.g. Schmitt et al., 2021). Whether trait variation is driven by phenotypic plasticity, genetic adaptation, or both, it is influenced by the extent of gene flow and the degree of environmental heterogeneity (Westerband et al., 2021).

Importance and drivers of local intraspecific variation in water- and carbon-related leaf traits

We found that local intraspecific variability was non-negligible for both carbon- and water-related traits, questioning the determinants of ITV unexplained by measurement error or among-sample variation. Ontogeny and light access are two key determinants of individual leaf variation (Roggy et al., 2005; Coste et al., 2009) that could explain part of the observed high ITV. As expected, we found a global positive effect of diameter, related to light access and tree size, on species trait values, with species faster to reach their mature value. Specifically, tree size favoured carbon-conservative strategies (Wright et al., 2004) for carbon-related traits with smaller, thicker and denser leaves, richer in chlorophyll and with a lower SLA, as already shown for ontogeny (Roggy et al., 2005) and light access (Coste et al., 2009).

However, the local effect of topography on water and nutrient availability (Ferry et al., 2010) is also expected to drive functional trait variation (Schmitt et al., 2020), especially in water-related traits (Garcia et al., 2022). Water-related traits are expected to vary mainly along topography within tropical tree species (Garcia et al., 2022), with higher resistance to drought for trees growing on plateaus compared with lowlands. We found no significant effect of topography either among or within species, in accordance with Emilio et al. (2021), but the leaf water potential at which leaf cells lose turgor (πTLP) and the leaf minimum conductance (gmin) had a global segregation of within-species response to topography, opening ways to future studies on the local drivers of ITV in water-related traits.

Finally, other factors might play a role in shaping functional traits within and among species, notably biotic interactions (Fine et al., 2004). In any case, both local microgeographical adaptations (Schmitt et al., 2022) and trait plasticity (Laurans et al., 2012) can drive phenotypic variations, including water- and carbon-related traits, along environments, although the latter is more likely (Bresson et al., 2011). The recent acknowledgment of a higher ITV than previously recognized (Emilio et al., 2021; Westerband et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2022), together with our study, expand its potential importance in ecological processes. The ITV of species has been positively related to niche breadth (Clark, 2010), resulting in larger geographical ranges (Brown, 1984). Therefore, a high ITV could improve the response of species to increasing local and global anthropogenic disturbances (Razgour et al., 2019). Given that we observed non-negligible ITV for water-related traits, it suggests that tropical species from our study might be able to adjust their physiological responses under future droughts and be less vulnerable than what is commonly assumed. On the contrary, underestimating ITV might underestimate the local response of trees to disturbances, such as greater sensitivity to drought in lowlands (Garcia et al., 2022).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following.

Figure S1: virtual experiment scheme. Figure S2: field sampling scheme. Figure S3: phylogeny of selected species. Figure S4: effect of the sampling strategy on correlations of other traits. Figure S5: effect of diameter at breast height on trait values. Figure S6: effect of topographic wetness index among and within species. Figure S7: effect of diameter at breast height on trait values. Figure S8: effect of topographic wetness index among and within species. Table S1: diameter distributions for sampled individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Pascal Petronelli and the Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement (CIRAD) inventory team for their work on tree inventories and botanical identification. Special thanks go to Josselin Cazal, Saint-Omer Cazal, Louise Alvergnat, Matais Bentkowski, Alice Bordes, Roxane Calvaire, Perrine Desvéronnières, Oriane Girard-Reydet, Mouctar Kamara, Sophie Millet and Camille Tourangin for their assistance during sampling in Paracou station. The authors have no conflict of interest. S.S. and M.B. conceived the ideas, designed the methodology, analysed model outputs and led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Contributor Information

Sylvain Schmitt, CNRS, UMR EcoFoG (Agroparistech, Cirad, INRAE, Université des Antilles, Université de la Guyane), Campus Agronomique, 97310 Kourou, French Guiana.

Marion Boisseaux, Université de la Guyane, UMR EcoFoG (Agroparistech, Cirad, CNRS, INRAE, Université des Antilles), Campus Agronomique, 97310 Kourou, French Guiana.

FUNDING

We thank the University of Guyane, the Centre National D’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) and the Collectivité Territoriale de Guyane (CTG) for a PhD grant to M. Boisseaux and acknowledge the support of a grant from Investissement d’Avenir grants of the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) (CEBA:ANR- 10-LABX-25-01).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Functional traits data have been deposited on the TRY initiative (Kattge et al. 2020) under the name hydroITV. DBH, TWI and spatial positions of individuals were extracted from the Paracou Station database, for which access is modulated by the scientific director of the station (https://paracou.cirad.fr). Scripts used for analyses can be found on GitHub (https://github.com/sylvainschmitt/hydroITV).

LITERATURE CITED

- Aguilos M, Stahl C, Burban B, et al. 2018. Interannual and seasonal variations in ecosystem transpiration and water use efficiency in a tropical rainforest. Forests 10: 14. doi: 10.3390/f10010014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albert CH, Grassein F, Schurr FM, Vieilledent G, Violle C.. 2011. When and how should intraspecific variability be considered in trait-based plant ecology? Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 13: 217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ppees.2011.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Lovera E, Goldsmith GR, Kay KM, Funk JL.. 2022. Above- and below-ground functional trait coordination in the Neotropical understory genus Costus. AoB PLANTS 14: plab073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraloto C, Paine CET, Patiño S, Bonal D, Hérault B, Chave J.. 2010. Functional trait variation and sampling strategies in species-rich plant communities. Functional Ecology 24: 208–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01600.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett MK, Scoffoni C, Ardy R, et al. 2012. Rapid determination of comparative drought tolerance traits: using an osmometer to predict turgor loss point: rapid assessment of leaf drought tolerance. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 3: 880–888. [Google Scholar]

- Barrs HD, Weatherley PE.. 1962. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Australian Journal of Biological Sciences 15: 413–428. [Google Scholar]

- Billon LM, Blackman CJ, Cochard H, et al. 2020. The DroughtBox: a new tool for phenotyping residual branch conductance and its temperature dependence during drought. Plant, Cell and Environment 43: 1584–1594. doi: 10.1111/pce.13750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonder B, Salinas N, Bentley LP, et al. 2017. Predicting trait-environment relationships for venation networks along an Andes-Amazon elevation gradient. Ecology 98: 1239–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresson CC, Vitasse Y, Kremer A, Delzon S.. 2011. To what extent is altitudinal variation of functional traits driven by genetic adaptation in European oak and beech? Tree Physiology 31: 1164–1174. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpr084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Powers J, Cochard H, Choat B.. 2020. Hanging by a thread? Forests and drought. Science 368: 261–266. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JH. 1984. On the relationship between abundance and distribution of species. The American Naturalist 124: 255–279. doi: 10.1086/284267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruelheide H, Dengler J, Purschke O, et al. 2018. Global trait–environment relationships of plant communities. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1: 1906–1917. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0699-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chave J, Coomes D, Jansen S, Lewis SL, Swenson NG, Zanne AE.. 2009. Towards a worldwide wood economics spectrum. Ecology Letters 12: 351–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JS. 2010. Individuals and the variation needed for high species diversity in forest trees. Science 327: 1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.1183506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad O, Bechtel B, Bock M, et al. 2015. System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses (SAGA) v. 2.1.4. Geoscientific Model Development 8: 1991–2007. doi: 10.5194/gmd-8-1991-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coste S, Roggy J-C, Garraud L, Heuret P, Nicolini E, Dreyer E.. 2009. Does ontogeny modulate irradiance-elicited plasticity of leaf traits in saplings of rain-forest tree species? A test with Dicorynia guianensis and Tachigali melinonii (Fabaceae, Caesalpinioideae). Annals of Forest Science 66: 709–709. doi: 10.1051/forest/2009062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coste S, Baraloto C, Leroy C, et al. 2010. Assessing foliar chlorophyll contents with the SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter: a calibration test with thirteen tree species of tropical rainforest in French Guiana. Annals of Forest Science 67: 607–607. doi: 10.1051/forest/2010020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins HC. 1958. The management of natural tropical high-forests with special reference to Uganda. Imperial Forestry Institute Paper 34: 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz S, Kattge J, Cornelissen JHC, et al. 2016. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 529: 167–171. doi: 10.1038/nature16489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emilio T, Pereira H, Costa FRC.. 2021. Intraspecific variation on palm leaf traits of co-occurring species—does local hydrology play a role? Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 4: 1–12. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2021.715266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry B, Morneau F, Bontemps J-D, Blanc L, Freycon V.. 2010. Higher treefall rates on slopes and waterlogged soils result in lower stand biomass and productivity in a tropical rain forest. Journal of Ecology 98: 106–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01604.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fine PVA, Mesones I, Coley PD.. 2004. Herbivores promote habitat specialization by trees in Amazonian forests. Science 305: 663–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1098982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MN, Hu J, Domingues TF, Groenendijk P, Oliveira RS, Costa FRC.. 2022. Local hydrological gradients structure high intraspecific variability in plant hydraulic traits in two dominant central Amazonian tree species. Journal of Experimental Botany 73: 939–952. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goud EM, Sparks JP.. 2018. Leaf stable isotopes suggest shared ancestry is an important driver of functional diversity. Oecologia 187: 967–975. doi: 10.1007/s00442-018-4186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlet-Fleury S, Guehl J.-M, Laroussine O.. 2004. Ecology and management of a neotropical rainforest: lessons drawn from Paracou, a long-term experimental research site in French Guiana. Paris: Elsevier. Retrieved from: http://agritrop.cirad.fr/522004/ [Google Scholar]

- Guillemot J, Martin-StPaul NK, Bulascoschi L, et al. 2022. Small and slow is safe: on the drought tolerance of tropical tree species. Global Change Biology 28: 2622–2638. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyot G, Scoffoni C, Sack L.. 2012. Combined impacts of irradiance and dehydration on leaf hydraulic conductance: insights into vulnerability and stomatal control. Plant, Cell and Environment 35: 857–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Kurjak D, Von Wühlisch G, Delzon S, Schuldt B.. 2016. Intraspecific variation in wood anatomical, hydraulic, and foliar traits in ten European beech provenances differing in growth yield. Frontiers in Plant Science 7: 791. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsen K, Acharya KP, Brunet J, et al. 2017. Biotic and abiotic drivers of intraspecific trait variation within plant populations of three herbaceous plant species along a latitudinal gradient. BMC Ecology 17: 38. doi: 10.1186/s12898-017-0151-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulshof CM, Swenson NG.. 2010. Variation in leaf functional trait values within and across individuals and species: an example from a Costa Rican dry forest. Functional Ecology 24: 217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01614.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai P, Pirani A, et al., eds.). Cambridge and New York:Cambridge University Press. In press, 10.1017/9781009157896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LC, Galliart MB, Alsdurf JD, et al. 2022. Reciprocal transplant gardens as gold standard to detect local adaptation in grassland species: new opportunities moving into the 21st century. Journal of Ecology 110: 1054–1071. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.13695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung V, Albert CH, Violle C, Kunstler G, Loucougaray G, Spiegelberger T.. 2014. Intraspecific trait variability mediates the response of subalpine grassland communities to extreme drought events. Journal of Ecology 102: 45–53. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kattge J, Bönisch G, Díaz S, et al. ; Nutrient Network. 2020. TRY plant trait database – enhanced coverage and open access. Global Change Biology 26: 119–188. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstiens G. 1996. Cuticular water permeability and its physiological significance. Journal of Experimental Botany 47: 1813–1832. doi: 10.1093/jxb/47.12.1813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuta SB, Richter H.. 1992. Leaf discs or press saps? A comparison of techniques for the determination of osmotic potentials in freeze-thawed leaf material. Journal of Experimental Botany 43: 1039–1044. doi: 10.1093/jxb/43.8.1039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecký M, Čížková S.. 2010. Using topographic wetness index in vegetation ecology: does the algorithm matter? Applied Vegetation Science 13: 450–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-109x.2010.01083.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laanisto L, Niinemets Ü.. 2015. Polytolerance to abiotic stresses: how universal is the shade–drought tolerance trade-off in woody species? Global Ecology and Biogeography 24: 571–580. doi: 10.1111/geb.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurans M, Martin O, Nicolini E, Vincent G.. 2012. Functional traits and their plasticity predict tropical trees regeneration niche even among species with intermediate light requirements. Journal of Ecology 100: 1440–1452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2012.02007.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bagousse-Pinguet Y, De Bello F, Vandewalle M, Leps J, Sykes MT.. 2014. Species richness of limestone grasslands increases with trait overlap: evidence from within- and between-species functional diversity partitioning. Journal of Ecology 102: 466–474. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levionnois S, Ziegler C, Heuret P, et al. 2021. Is vulnerability segmentation at the leaf-stem transition a drought resistance mechanism? A theoretical test with a trait-based model for Neotropical canopy tree species. Annals of Forest Science 78: 87. doi: 10.1007/S13595-021-01094-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levionnois S, Ziegler C, Jansen S, et al. 2020. Vulnerability and hydraulic segmentations at the stem–leaf transition: coordination across Neotropical trees. New Phytologist 228: 512–524. doi: 10.1111/nph.16723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maréchaux I, Bartlett MK, Gaucher P, Sack L, Chave J.. 2016. Causes of variation in leaf-level drought tolerance within an Amazonian forest. Journal of Plant Hydraulics 3: e004. doi: 10.20870/jph.2016.e004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloh KA, Augustine SP, Goke A, et al. 2023. At least it is a dry cold: the global distribution of freeze–thaw and drought stress and the traits that may impart poly-tolerance in conifers. Tree Physiology 43: 1–15. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpac102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier J, McGill BJ, Lechowicz MJ.. 2010. How do traits vary across ecological scales? A case for trait-based ecology. Ecology Letters 13: 838–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine CET, Baraloto C, Chave J, Hérault B.. 2011. Functional traits of individual trees reveal ecological constraints on community assembly in tropical rain forests. Oikos 120: 720–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2010.19110.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2020. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Razgour O, Forester B, Taggart JB, et al. 2019. Considering adaptive genetic variation in climate change vulnerability assessment reduces species range loss projections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116: 10418–10423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820663116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roggy JC, Nicolini E, Imbert P, Caraglio Y, Bosc A, Heuret P.. 2005. Links between tree structure and functional leaf traits in the tropical forest tree Dicorynia guianensis Amshoff (Caesalpiniaceae). Annals of Forest Science 62: 553–564. doi: 10.1051/forest:2005048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas T, Mencuccini M, Barba J, Cochard H, Saura-Mas S, Martínez-Vilalta J.. 2019. Adjustments and coordination of hydraulic, leaf and stem traits along a water availability gradient. New Phytologist 223: 632–646. doi: 10.1111/nph.15684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüger N, Condit R, Dent DH, et al. 2020. Demographic trade-offs predict tropical forest dynamics. Science 368: 165–168. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L, Scoffoni C.. 2011. Minimum epidermal conductance (gmin, a.k.a. cuticular conductance). PrometheusWiki. https://prometheusprotocols.net/function/gas-exchange-and-chlorophyll-fluorescence/stomatal-and-non-stomatal-conductance-and-transpiration/minimum-epidermal-conductance-gmin-a-k-a-cuticular-conductance/ (25 March 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sapes G, Sala A.. 2021. Relative water content consistently predicts drought mortality risk in seedling populations with different morphology, physiology and times to death. Plant, Cell and Environment 44: 3322–3335. doi: 10.1111/pce.14149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt S, Hérault B, Ducouret E, et al. 2020. Topography consistently drives intra- and inter-specific leaf trait variation within tree species complexes in a Neotropical forest. Oikos 129: 1521–1530. doi: 10.1111/oik.07488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt S, Tysklind N, Hérault B, Heuertz M.. 2021. Topography drives microgeographic adaptations of closely related species in two tropical tree species complexes. Molecular Ecology 30: 5080–5093. doi: 10.1111/mec.16116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt S, Tysklind N, Heuertz M, Hérault B.. 2022. Selection in space and time: Individual tree growth is adapted to tropical forest gap dynamics. Molecular Ecology 1–11. doi: 10.1111/mec.16392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW.. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9: 671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefert A, Ritchie ME.. 2016. Intraspecific trait variation drives functional responses of old-field plant communities to nutrient enrichment. Oecologia 181: 245–255. doi: 10.1007/s00442-016-3563-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefert A, Violle C, Chalmandrier L, et al. 2015. A global meta-analysis of the relative extent of intraspecific trait variation in plant communities. Ecology Letters 18: 1406–1419. doi: 10.1111/ele.12508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña MN, Zipkin EF, Zhang C, Cao M, Lin L, Swenson NG.. 2018. Individual-level trait variation and negative density dependence affect growth in tropical tree seedlings. Journal of Ecology 106: 2446–2455. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.13001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vieilledent G, Courbaud B, Kunstler G, Dhôte JF, Clark JS.. 2010. Individual variability in tree allometry determines light resource allocation in forest ecosystems: a hierarchical Bayesian approach. Oecologia 163: 759–773. doi: 10.1007/s00442-010-1581-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violle C, Enquist BJ, McGill BJ, et al. 2012. The return of the variance: intraspecific variability in community ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 27: 244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerband AC, Funk JL, Barton KE.. 2021. Intraspecific trait variation in plants: a renewed focus on its role in ecological processes. Annals of Botany 127: 397–410. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcab011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright IJ, Reich PB, Westoby M, et al. 2004. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428: 821–827. doi: 10.1038/nature02403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Lu J, Chen Y, et al. 2020. Large underestimation of intraspecific trait variation and its improvements. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 53. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Functional traits data have been deposited on the TRY initiative (Kattge et al. 2020) under the name hydroITV. DBH, TWI and spatial positions of individuals were extracted from the Paracou Station database, for which access is modulated by the scientific director of the station (https://paracou.cirad.fr). Scripts used for analyses can be found on GitHub (https://github.com/sylvainschmitt/hydroITV).