Abstract

We aim to infer bioactivity of each chemical by assay endpoint combination, addressing sparsity of toxicology data. We propose a Bayesian hierarchical framework which borrows information across different chemicals and assay endpoints, facilitates out-of-sample prediction of activity for chemicals not yet assayed, quantifies uncertainty of predicted activity, and adjusts for multiplicity in hypothesis testing. Furthermore, this paper makes a novel attempt in toxicology to simultaneously model heteroscedastic errors and a nonparametric mean function, leading to a broader definition of activity whose need has been suggested by toxicologists. Real application identifies chemicals most likely active for neurodevelopmental disorders and obesity.

Keywords: Bayesian hierarchical model, bioactivity profiles, chemical screening, heteroscedasticity, latent factor models, ToxCast/Tox21

1. Introduction

Screening and regulating hazardous chemicals is of great importance and urgency especially as massive numbers of new chemicals are introduced every year. The traditional animal or in vivo testing paradigms are infeasible due to financial and time constraints (Dix et al. 2007; Judson et al. 2010); in addition, it is desirable to minimize animals used in any testing procedure for ethical reasons. Many organizations, such as the World Health Organization’s Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety, European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), and United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) screen chemicals to measure their potential toxicity and develop alternatives to animal testing.

As a high-throughput screening (HTS) mechanism has been developed based on in vitro assays and a large number of chemicals, EPA and ECHA have had opportunities to operate relatively low-cost and rapid chemical screening programs. For instance, Toxicity Forecaster (ToxCast) and Toxicology in the 21st Century (Tox21) from EPA are designed to identify chemicals that likely induce toxicity in humans and prioritize them for further testing (Judson et al. 2010), using HTS methods. ECHA also promotes similar approaches expediting chemical risk prioritization and assessment for the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals regulation (ECHA 2017). For the rest of this paper, we use the EPA’s ToxCast/Tox21 data as a representative of general HTS data. To the authors’ knowledge, ToxCast/Tox21 is the largest in size among existing HTS data in toxicology. Furthermore, it has universal coverage of molecules that many regions including Canada, Japan, and European Union as well as the United States have approved for clinical use (Tice et al. 2013).

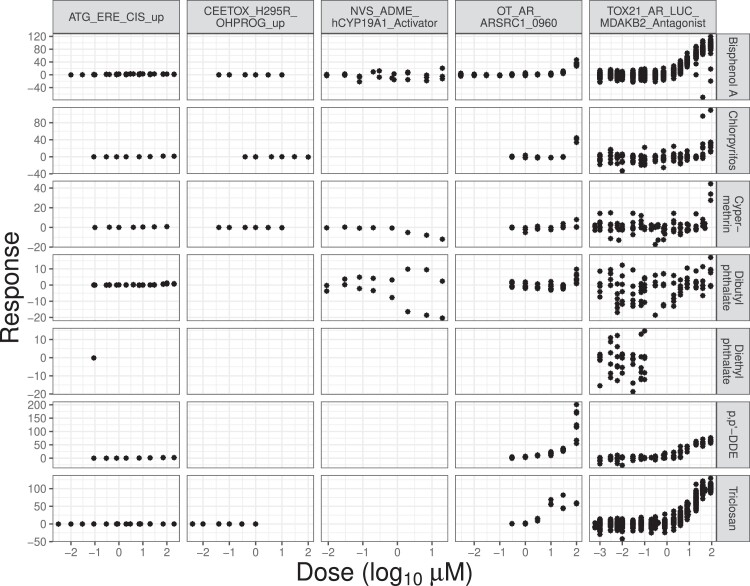

The ToxCast/Tox21 program tests thousands of chemicals against numerous high-throughput assay endpoints. If a chemical exposure leads to biological reactions in an assay, we say the chemical is active for the assay. One of the main goals of these tests is to identify bioactivity profiles of chemicals—either active or inactive—across different assays through various endpoints. However, missingness poses a challenge. Although the HTS mechanism has provided a relatively cheap and quick way to conduct millions of tests, it is still only possible to test a small minority of all (chemical, assay endpoint) combinations at irregular doses. This leads to many combinations with few observations or even none as shown in Figure 1 and online supplementary material, Figure 7. Figure 1 displays the observed measurements for selected chemicals and assay endpoints from the ToxCast/Tox21 data, and online supplementary material, Figure 7 illustrates the overall structure of the data, colour-coded by the number of observations. Here, an observation is the result from an experiment where a chemical is applied to an assay at a certain dose. We confirm from the figures that the number of observations largely fluctuates across (chemical, assay endpoint) cells; many cells are empty, some have few observations, while others have multiple replicates at a finer grid of doses.

Figure 1.

Detailed illustration of the ToxCast/Tox21 data structure. Sample data for seven chemicals on rows and five assay endpoints on columns. Each cell contains a set of test results of a single chemical against one assay endpoint, which forms functional data on a dose–response curve.

We arrange the HTS data as matrix-structured functional data, with rows of the matrix corresponding to different chemicals, columns to different assay endpoints, and cells containing sparse dose–response measurements. Our inferential contribution is to construct a complete matrix of the same dimension in which each cell contains a binary indicator for activity using the incomplete and sparse HTS data matrix. Traditional matrix completion focuses on the problem of filling in missing elements of a large matrix based on observations on a small proportion of cells. Typically, the observed cells contain a scalar that is assumed to be measured without error. We are instead faced with a latent binary matrix completion problem. This can be viewed as a matrix-structured multiple hypothesis testing problem for assessing dose–response relationships.

There have been many Bayesian approaches to multiple hypothesis testing (Li & Zhang 2010; Scheel et al. 2013; Scott & Berger 2006, 2010; Thomas et al. 2009; Wilson et al. 2014). Bayesian approaches are attractive due to their automatic adjustment for multiplicity (Scott & Berger 2006, 2010) by treating hyperparameters controlling model size as unknown and informed by the data. In the typical framework, hypotheses are considered exchangeable a priori. For example, variable selection cases have hypotheses and in which is an indicator of whether the th variable is included for , and is a global parameter controlling model size. A variety of more elaborate nonexchangeable priors have been proposed for , designed to include ‘prior covariates’ informing (Thomas et al. 2009) and known structure among covariates represented by an undirected graph (Li & Zhang 2010).

There has also been some consideration of matrix-structured multiple testing. In relation to dose–response curves, Wilson et al. (2014) test for dose effects on the mean using a generalized linear mixed effects model. The mean effect indicator for a (chemical , assay endpoint ) pair follows a Bernoulli distribution with . Then is further structured with an assay endpoint random effect, chemical-level fixed effect and a probit link: where is the chemical-level covariate and is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution. However, it is nontrivial to find informative chemical-level covariates in this context. In their ToxCast/Tox21 application, Wilson et al. (2014) found their covariate, chemical solubility, was not significant in explaining , resulting in a simplified model with only random effects for assay endpoints.

In order to account for mechanistic similarities among chemicals and/or assay endpoints as well as to tackle sparsity of the data, we require a more sophisticated hierarchy that borrows information across both rows and columns of the matrix. Tansey et al. (2019) propose hierarchical functional matrix factorization methods to infer dose–response curves, approximating the row and the column space using low-dimensional latent attributes. However, their model lacks a formal testing framework. Furthermore, they assume a matrix data structure in which all cells have the same number of replicates at the same number of unique doses, which might not be guaranteed in HTS data. The ToxCast/Tox21 data have different numbers of unique doses within a column and varying numbers of replicates at each dose within a cell.

We adapt low-rank approximations addressing matrix completion problems (Koren et al. 2009; Mnih & Salakhutdinov 2008; Purushotham et al. 2012; Tansey et al. 2019) to a multiple hypothesis testing framework and extend them for more general data structures. This hierarchical Bayesian matrix completion (BMC) approach for hypothesis testing is particularly useful for sparse data. We construct with a latent factor model, assuming that low-dimensional latent attributes account for associations relevant to the mean effect among chemicals or assay endpoints. A posterior summary matrix of naturally prioritizes chemicals and enables out-of-sample prediction of bioactivity for chemicals not yet tested on certain endpoints, which significantly reduces the amount of in vitro testing data that are needed.

Other important characteristics of HTS data are irregular dose–response shapes and heteroscedasticity. Many previous studies placed monotone nondecreasing shape restrictions on dose–response curves (Neelon & Dunson 2004; Ritz 2010; Wilson et al. 2014) and did not consider heteroscedasticity. Our approach is strongly motivated by evidence that disruption in centrality or dispersion of intricately controlled biological pathways observed in vitro can lead to in vivo toxicity and ultimately connect to detrimental health effects (Klaren et al. 2019; Knapen et al. 2020). Accordingly, a novel attempt in toxicology simultaneously to model heteroscedastic errors as well as any nonconstant shapes of the mean completes BMC. This leads to a broader definition of activity as any changes in mean and variance of dose–response curves. These considerations provide a more holistic perspective on active chemicals than previous research.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 further explains motivating aspects for a model applicable to HTS data. Section 3 summarizes the ToxCast/Tox21 data of relevance to neurodevelopmental disorders and obesity. Then, the BMC approach is described throughout section 4. We compare the performance of BMC with existing methods on simulated data sets and show results using our HTS data in section 5, highlighting chemicals that pose greater risks for obesity and neurodevelopment endpoints. Potential areas of future research are discussed in section 6. The data and the code to reproduce all analyses in the paper are available at https://github.com/jinbora0720/BMC.

2. Motivating aspects and relevant literature

2.1. Hierarchical structures

A simple approach for matrix-structured data would be to consider each cell independently. The EPA has developed an R package tcpl (Filer et al. 2017) to facilitate independent dose–response modelling of the ToxCast data. This R package provides three default models: a constant model at zero, a three-parameter Hill model, and a five-parameter gain–loss model for each (chemical, assay endpoint) combination separately. Unfortunately, independently inferring dose–response relationships does not have predictive power: it cannot predict activity for cells having no data. Further, it is likely to have low power and high variance in estimation due to the intrinsic sparsity of the ToxCast/Tox21 data shown in Figure 1 and online supplementary material, Figure 7. In the ToxCast/Tox21 data, the median number of unique doses tested for each pair is eight, and about 30% of them are without replicates. Therefore, hierarchical methods for borrowing information are crucial.

2.2. Splines without shape restrictions

In estimating dose–response curves, researchers have often forced parametric or monotone restrictions on shapes of the curves to increase interpretability. The EPA’s default models currently available through the tcpl package heavily depend on parametric assumptions and are restricted to positive responses to reduce the parameter space, requiring an inverse transformation to fit negative responses. In addition, Wilson et al. (2014) model dose–response functions by piecewise log-linear splines with constrained parameters to ensure responses are monotone and nondecreasing. In the ToxCast/Tox21 data, it appears difficult to standardize shapes of the dose–response curves (Figure 1). Furthermore, we observe some examples of decreasing trends between certain assay endpoints (e.g., TOX21_ERa_LUC_BG1_Agonist as shown in online supplementary material, Figure 8) and multiple chemicals. Thus, we propose a nonrestricted spline model robust to any shapes of dose–response curves, given that both upturns and downturns in dose–response functions are suggestive of potential toxicity.

2.3. Heteroscedastic variances

Toxicological HTS data have innate heteroscedasticity. Such heteroscedasticity is inevitable because dose effects are variable by nature, with variability often amplified at high doses. Differences in the ability of assays to absorb chemical doses further inflate this variability. Wilson et al. (2014) attempted to reduce such heteroscedasticity by log transforming the data. However, data transformations may be hard to justify theoretically (Leslie et al. 2007) and may be insufficient practically. In genetics, multiple studies have been conducted to detect genetic loci that affect heteroscedastic errors of quantitative traits of interest (Paré et al. 2010; Rönnegård & Valdar 2012; Yang et al. 2012). It is widely appreciated that analysing differences in variance could reveal a previously unknown genetic influence and alternative biological relevance. Although detection of heteroscedastic variances is routinely considered in genetic analysis (Corty & Valdar 2018), it has not been of main interest in chemical toxicity analysis. Without data transformations, we consider heteroscedasticity as another source of information. Fortunately, the ToxCast/Tox21 data have been thoroughly characterized with respect to sources of variability (Hsieh et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2014), and the performance metrics in Huang et al. (2014) indicate that the data have low technical error (e.g., plate-to-plate variation for controls) relative to the heteroscedasticity signals we report. We design an indicator for heteroscedasticity and provide posterior probabilities for the variance effect.

3. Data

This paper uses data from the ToxCast/Tox21 project (invitroDBv3.2, released on March 2019), available at https://epa.figshare.com/articles/ToxCast/Tox21˙Database˙invitroDB˙for˙Mac˙Users/6062620. We focus on a subset of the ToxCast/Tox21 data that contain assay endpoints relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders and obesity, along with chemicals tested over those assay endpoints. As a result of selection criteria for chemicals and assay endpoints described in the online supplementary material, Section 8, 30 chemicals evaluated across 131 assay endpoints are studied for neurodevelopmental disorders. These create in total 3,930 cells, from which 2,024 cells (51.5%) are missing. For obesity, we use the same 30 chemicals evaluated across 271 assay endpoints. Among the total 8,130 cells, 3,274 cells (40.3%) contain no data.

4. Model

4.1. Matrix completion

Primary interest lies in differentiating active and inactive chemicals. First, we conduct multiple hypothesis testing of whether the dose–response curve is constant or not across chemicals and assay endpoints. We introduce latent binary indicators , with denoting that the average dose–response curve is not constant for the (chemical , assay endpoint ) pair. Let vector represent chemical ’s mean effect profile across assay endpoints for . We assume that chemicals and assay endpoints explain dose effects on the mean via low rank latent features, for which we exploit a sparse Bayesian factor model (Bhattacharya & Dunson 2011). Since each takes values, we impose a generalized factor model using a probit link

| (1) |

A data-augmented form rewrites equation (1) as

| (2) |

In the factor model, is an overall intercept, represents the coefficient of the th latent pathway for the th chemical to have the mean effect, and for the th assay endpoint to have the mean effect for and . The inequality is reasonable, assuming that not every assay endpoint or chemical forms an idiosyncratic latent pathway for the mean effect. BMC lets either be treated as factor loadings and as latent factors or vice versa, depending on researchers’ interests. Provided that one is interested in latent covariance structure among chemicals with regards to the mean effect, a standard factor model puts a multivariate standard normal prior on latent factors . Integrating out from equation (2) yields where has as its th row. This factor model provides a low-dimensional representation of the underlying covariance structure of chemicals.

We employ a multiplicative gamma process shrinkage prior on factor loadings as in Bhattacharya and Dunson (2011):

| (3) |

| (4) |

This prior choice is supported by Judson et al. (2010) who elucidate relationships between chemicals and published pathways: chemicals activate various human genes and pathways, but the number of activated pathways varies widely across chemicals. The multiplicative gamma process shrinkage prior tends to shrink columns of a loading matrix towards zero through the ’s. At the same time, it is possible to strongly shrink only a subset of elements in a certain column through local shrinkage parameters ’s, retaining sparse signals. We assume for the global parameter and recommend to use an informative prior because the information for is largely available from other studies.

Second, we simultaneously test if heteroscedasticity exists or not. Let indicate changes in the variance of the response with dose, which we denote as variance activity. Assuming that mean activity and variance activity are likely to be related, we set another factor model for using the factor loadings and the latent factors from the mean activity: in which and are a scalar. Equivalently,

| (5) |

Notice that for positive indicates that the th chemical likely to activate the th assay endpoint in the mean is also likely to activate it in variance. If then heteroscedasticity for each pair is determined by a global parameter . The vector has a prior distribution of .

4.1.1. Multiplicity adjustment

In our matrix-structured multiple testing, we have cells, each of which has two hypothesis tests: whether is 0 or 1 and is 0 or 1. Multiplicity is corrected by learning global parameters and from the data. The intuition is that, as or increase while the number of true 1’s in and remain constant, and will concentrate around large negative values, leading to probabilities near zero after applying . Consider the following posterior distribution for assuming no missing cells,

As , and because most of will be negative. Hence, the posterior of will concentrate at large negative values. Similar arguments apply for . We show that our model properly adjusts for multiplicity via simulation studies in Section 5.1.

4.2. Dose–response functional data analysis

4.2.1. Splines without shape restrictions

Let be a test dose (in log base 10 scale in micromolar ) of the th measurement for a (chemical , assay endpoint ) pair, and let be the corresponding response. Consider the model where the error distribution is for , , and . Nonconstant dose–response curves are estimated when . We model the dose–response function using cubic B-splines with degrees of freedom, which is equivalent to estimating in with the B-spline basis matrix of size . We normalize responses and centre columns of the B-spline basis matrix by pairs prior to any analyses in order to exclude the intercept. As Figure 1 suggests dose–response functions share more similarities within an assay endpoint than between different assay endpoints. This suggests a formulation in which spline coefficients of different chemicals have a common prior covariance matrix for the same assay endpoint. Thus, the prior distributions of spline coefficients and their hyperparameters are with fixed and , where is a Wishart distribution in -dimensions with . We suggest the following default choices for our application. For assay endpoint-specific covariance matrices, is determined as the empirical covariance of the ordinary least-squares estimates for chemical-assay endpoint pairs. The degrees of freedom parameter is chosen to be so that is loosely centred around . While it may seem natural to borrow information also across chemicals, in fact, two chemicals having similar mean activity profiles often have dramatically different dose–response curves. Hence, we are reluctant to borrow information in this manner.

4.2.2. Heteroscedastic variances

Online supplementary material, Figure 9 illustrates that ranges of responses may vary substantially by assay endpoints. This suggests modelling errors with assay endpoint-specific variances. Moreover, we are motivated to capture heteroscedasticity to explain another dimension of chemical activity. We use a log-linear model on so that and . Here, we separate variance into an assay endpoint-specific variability and a part that changes with dose. Reparametrizing with gives the final model equation

| (6) |

The assay endpoint-specific variances have an inverse-Gamma distribution a priori: , , fixed. In our application, we suggest fixing the hyperparameters at 1 and at the sample variance of the response variable to have the prior distribution weakly centred around a simple estimate from data.

We assume a spike-and-slab prior for coefficients such that if with fixed , and if . In our case, we found that ensuring a large enough value for that appropriately covers the data range improves estimation of and . Provided that conditional standard deviations of responses given doses can be proxies for in equation (6), a range of ’s is obtained. The variance parameter of is then determined as the square of the range divided by 4, which makes 2 SD intervals for cover its sample range. We finally fix at the maximum of the above value and the sample variance of the response variable. Combined with , this allows the prior distributions of two variance parts—the assay endpoint-specific and the heteroscedastic variance—to place enough probability on the observed variability from the data.

In conclusion, equation (6) is the final model in which is an indicator specifying whether the th chemical activates the th assay endpoint in the mean, is an indicator if the th chemical activates the th assay endpoint in variance, is a dose–response function, the exponential term allows for modelling heteroscedastic residual variance, and measurement error is modelled with normal distributions having assay endpoint-specific variances. We suggest a new metric for activity including mean perturbation as well as variance perturbation, which is computed as .

4.3. Posterior computation

Our posterior samples are obtained using Metropolis–Hastings steps within a partially collapsed Gibbs sampler. Most of the parameters have conjugate posterior distributions which lead to a straightforward update. Details are provided in the online supplementary material, Section 11. The code for the sampler to automate any relevant analyses is readily available to other researchers at https://github.com/jinbora0720/BMC.

5. Results

5.1. Simulations

Simulation studies were conducted to evaluate the performance of BMC in learning latent correlation structures among chemicals and predicting activity probabilities. Two broad scenarios of simulations were examined corresponding to data simulated from BMC (Simulation 1) or an alternative (Simulation 2). For predictive performance, BMC was compared with three variations in the prior structure of . Instead of a latent factor model, we assume simpler structures a priori as follows:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

We call models with equations (7)–(9) BMC, BMC, and BMC, respectively. BMC assumes that each chemical has its own intrinsic mean effect probability, while BMC assumes that each assay endpoint has its own mean effect probability. These three variations assume a simpler structure for the heteroscedasticity indicator such that and . For estimation performance, the proposed model is compared with the zero-inflated piecewise log-logistic model (ZIPLL) (Wilson et al. 2014) and tcpl (Filer et al. 2017). The ZIPLL code at https://github.com/AnderWilson/ZIPLL utilizes a Bayesian hierarchical approach whose testing framework for the mean effect adopts equation (7). Since the code does not allow missing pairs in the data, we only use ZIPLL for estimation and not prediction. The tcpl models are currently used by EPA and treat dose–response curves independently.

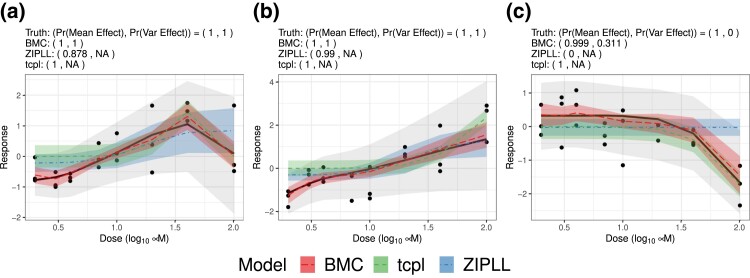

In Simulation 1 in which BMC is the true data generating process, mimicking the ToxCast/Tox21 application, the number of chemicals was set to 30, and the number of assay endpoints to 150. We generate 30 data sets, and in each set we hold out 225 pairs at random, which are 5% of the total cells in the data matrix. The profiles of the mean effect for chemical-assay endpoint pairs were sampled assuming a factor model, which induced a correlation structure among chemicals (online supplementary material, Figure 10). The overall intercept is set at 0. For pairs having dose effects on the mean, dose–response functions were given as one of the three categories: mostly increasing and decreasing at higher doses; monotonically increasing; and decreasing. Figure 2 presents examples of dose–response functions of each category. Heteroscedasticity is assumed to be positively associated with the mean effect, i.e., with . More specific settings of Simulation 1 are described in the online supplementary material, Section 9.

Figure 2.

Dose–response curves (solid line) with fitted mean functions by Bayesian matrix completion (BMC, long dash line), zero-inflated piecewise log-logistic model (dot-dashed line), and tcpl (dashed line) in Simulation 1. The true curve is mostly increasing and decreasing at higher dose in (a) monotonically increasing in (b) and monotonically decreasing in (c). Shaded areas around estimated functions of the same colour represent 95% credible intervals for the average dose–response curves computed by BMC and ZIPLL, and confidence intervals by tcpl. Light grey areas illustrate 95% posterior predictive intervals from BMC for data points.

As illustrated in Figure 2, BMC accurately captures true curves regardless of shapes. It also produces tighter 95% credible intervals (CIs) for the average dose–response curves than competitors. The competitors, ZIPLL and tcpl models, do not seem robust enough to various dose–response curves. In particular, ZIPLL estimates a decreasing trend as constant, which is evident in Figure 2c. For generally increasing curves (a, b), the ZIPLL and tcpl models sometimes miss the true dose–response functions, which becomes more noticeable when heteroscedasticity exists. These results suggest that in some cases, BMC can lead to more precise inferences on values estimated through dose–response curves, such as Emax (greatest attainable response) or AC50 (chemical dose producing half-maximal response in an assay endpoint).

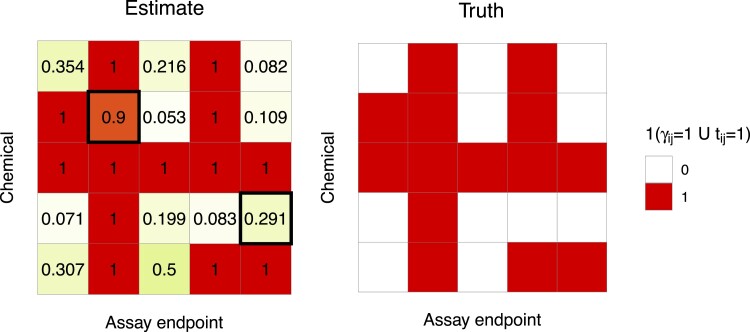

BMC provides precise estimation of the latent correlations among chemicals (online supplementary material, Figure 10). Two factors () generated the truth, and the sampler ran with a guess of three more factors. The multiplicative gamma process shrinkage prior helped recover the true number of factors by shrinking factor loadings of redundant factors to zero (online supplementary material, Figure 11). Figure 3 displays an example of activity profiles. The truth is adequately captured via the estimated and predicted probabilities. Results from a subset of the whole heat map are shown for better visualization. The complete matrices of estimates and the truth are quite similar.

Figure 3.

Heat map of estimated and true profiles of activity from Simulation 1. The figure presents the results from a subset chosen at random. The value in each cell of the left panel is the posterior mean of . Cells with outer lines [(2,2) and (4,5) elements] are held-out pairs for which ’s are predicted.

Table 1 summarizes simulation results when the data generating process is BMC. From BMC-variants, results from BMC are presented because BMC showed slightly better performance over the other two. Note that Area Under the ROC Curves (AUCs) from tcpl in Table 1 and online supplementary material, Table 3 were computed slightly differently than those from other methods. BMC, three variations, and ZIPLL all produce probability of active responses, which can be any value between 0 and 1. In order to evaluate the accuracy of estimates compared with the true values, ROC curves and the corresponding AUCs are computed by changing thresholds between 0 and 1. On the other hand, EPA provides a binary hit-call variable for the mean effect through ToxCast/Tox21. We hereafter refer to this variable (based on the version invitroDBv2) as EPA’s hit-call. The EPA’s hit-call identifies a pair as active if the fitted Hill or gain–loss model have lower Akaike information criterion than a constant model, and both the estimated and observed maximum responses exceed an efficacy cut-off chosen for the assay endpoint. This classification of whether each pair is active or not is directly comparable to the true without changing thresholds. In simulations, assay endpoint-specific cut-offs are set at 0.

Table 1.

Mean and standard errors in parenthesis across 30 simulation results when BMC is the true data generating process

| BMC | BMC | ZIPLL | tcpl | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | 0.423 (0.016) | 0.424 (0.016) | 0.834 (0.028) | 0.696 (0.015) |

| In-sample AUC for | 0.995 (0.001) | 0.991 (0.002) | 0.667 (0.006) | 0.811 (0.008) |

| Out-of-sample AUC for | 0.786 (0.068) | 0.502 (0.043) | — | — |

| In-sample AUC for | 0.999 (0.001) | 0.998 (0.001) | — | — |

| Out-of-sample AUC for | 0.794 (0.068) | 0.503 (0.029) | — | — |

| In-sample AUC for | >0.999 (<0.001) | 0.999 (<0.001) | — | — |

| Out-of-sample AUC for | 0.828 (0.064) | 0.523 (0.053) | — | — |

Note. Root mean squared error (RMSE) and area under the ROC curve (AUC) results for probabilities of mean effect, variance effect, and activity are presented.

Table 1 shows that BMC outperforms the other methods overall. In training data sets, BMC approaches (BMC and BMC) have lower RMSEs and higher AUCs compared with tcpl or ZIPLL. Poor performance of ZIPLL in these simulations is partially due to the facts that monotone increasing shape restrictions fail to fit decreasing trends and that ZIPLL does not allow for different ’s. BMC outperforming tcpl may be due to the borrowing of information across chemicals and assay endpoints. Another benefit of BMC is the capability of modelling heteroscedasticity. The AUCs for in Table 1 exhibit highly accurate estimation/prediction performance for detecting potential heteroscedastic variances, which is not available for non-BMC models. Moreover, BMC produces in- and out-of-sample AUCs that are uniformly better than those from BMC. Hence, when the factor model provides a realistic characterization of the dependence structure across assay endpoints and chemicals, it is not suggested to use a simplified model for multiple testing. Less structure in and results in lower out-of-sample AUCs.

Figure 2 illustrates that BMC closely recovers the true curves even in the existence of heteroscedasticity (a, b). To see if there are any unexplained patterns in residuals, plots of the residuals versus fitted values were examined from (a) and (b) (see online supplementary material, Figure 12). The ZIPLL does not consider heteroscedasticity in the model and consequently results in heteroscedastic residuals. In contrast, BMC is able to properly account for heteroscedasticity, and residuals do not show any patterns against fitted values. In addition, BMC nicely differentiates variance changes and mean changes. For instance, the estimated probability of the variance effect is around 0.3, while the probability of the mean effect is 1 in (c).

Simulation 2 generates data from an alternative model, ZIPLL. Despite misalignment in data structure assumed by BMC and by ZIPLL, BMC performs similarly to ZIPLL and outperforms tcpl with respect to RMSE and AUC. The high in-sample AUC for from BMC (0.982) suggests its stable estimation performance even with relatively small number of chemicals and assay endpoints () and model misspecification. We provide a full discussion of Simulation 2 results in the online supplementary material, Section 9.

Another simulation (Simulation 3) is conducted to show how and where multiplicity adjustment occurs. We ran simulations with the number of chemicals and assay endpoints and repeat for increasing , 20, 50, 100. Data were generated assuming BMC is the true model. Throughout the simulations, the number of 1’s in and in are fixed at 20 and 18, respectively. We expect our testing framework to have a strong control over false positives. Table 2 shows that the false positives evaluated at 0.5 remain small and steady as increases. We also observe decreasing posterior means of and towards large negative values as expected. Therefore, we conclude that the multiple testing problem is properly accounted for under BMC. More simulation settings for Simulation 3 are fully described in the online supplementary material, Section 9.

Table 2.

Summary of results for multiplicity simulations with fixed and increasing

| FPs for | FPs for | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0 | 0.209 | 1.824 | |

| 2 | 2 | 0.537 | 0.959 | |

| 6 | 1 | 1.922 | 0.463 | |

| 3 | 2 | 2.481 | 1.032 | |

| 2 | 3 | 3.446 | 1.324 |

Note. False positives (FPs) are computed at the cut-off 0.5 (if the posterior probability exceeds 0.5 then it is taken as a ‘positive’). Posterior mean of and are provided.

In a final set of simulations, we empirically investigate performance of in terms of AUC by varying missingness and correlation structures (Simulation 4). We examine two cases in which chemicals are highly correlated or weakly correlated (see online supplementary material, Figure 16). Missingness varies from 10% to 50% in which the maximum level is chosen to reflect ToxCast/Tox21 data. As expected, out-of-sample AUCs tend to decrease as missingness increases. Despite the decreasing trend, the out-of-sample AUCs remain high (>0.9) even with 50% missingness when chemicals are highly correlated, and the model is well specified. This is due to the fact that BMC properly exploits the correlated structure of chemicals through a latent factor model. However, performance can decline in weak correlation cases as borrowing of information pays less dividends; out-of-sample AUCs are acceptable (>0.7) only up to 30% missingness. These results are summarized in online supplementary material, Tables 4 and 5.

5.2. ToxCast/Tox21 results

This section presents results from the ToxCast/Tox21 data analysis with a focus on endpoints relevant to human neurodevelopmental disorders and obesity. We ran the sampler for 40,000 iterations from which 30,000 were discarded as burn-in, and every 10th sample was saved for the next 10,000 iterations. This long burn-in is to be conservative; trace plots and effective sample sizes for posterior samples indicated good mixing and apparent convergence after 15,000 iterations. We also checked the log-linear assumption for heteroscedastic variances using posterior predictive samples. We computed the empirical coverage of 95% posterior predictive intervals for data points in cells with estimated . The average is 0.961, and the middle 50% of the empirical coverage rates lie in [0.941, 0.989]. Therefore, we conclude that the log-linear variance model provides an adequate fit to the data.

We provide a new mean activity indicator along with for the ToxCast/Tox21 analysis. The is designed to incorporate efficacy cut-offs motivated by the EPA’s hit-call. Efficacy cut-offs are specific to assay endpoints and provide a minimum magnitude for biologically interesting maximal responses. Recall that the EPA’s hit-call is 1 if the Hill or gain–loss model wins over a constant model, and both the estimated and observed maximum responses are larger than an efficacy cut-off for each assay endpoint. The rationale behind the two criteria for EPA’s hit-calls is to incorporate scientific significance through efficacy cut-offs as well as statistical significance. In the ToxCast/Tox21 data, is estimated as with the 95% CI , yielding . This high intercept suggests that many small signals are statistically significant with naive . Hence, we make , that is, is 1 if and the fitted maximum exceeds a cut-off. This is designed to utilize scientific knowledge about big enough signals. In our analyses, we normalize data within each pair, so the cut-offs are also normalized accordingly. We expect to be more conservative than . BMC provides both metrics and so that researchers can have balanced understanding of chemicals’ mean activity based on scientific and statistical significance.

Despite being sensitive to small signals, is much more robust and conservative even though they share the same factor loadings and latent factors. The difference in behaviours is attributable to coefficients. In the ToxCast/Tox21 application, is with 95% CI , and is negative with mean with 95% CI . This negative value may not imply that mean activity and variance activity move in different directions. Rather, we view it as undoing detection of cells with small signals as they are unlikely to be disturbed in variance. This perspective is supported by that converted 0/1’s from posterior means of and achieve strong concordance when higher conversion cut-off is applied to than to .

We discovered that one of the latent factors of assay endpoints is highly related to detection technology (see online supplementary material, Figure 13). Measuring assay endpoints relies on a variety of different technologies for detecting and quantifying analytes; these technologies have different levels of sensitivity to bioactivity. Therefore, it is reasonable that one of the activity-relevant latent factors has a strong connection with detection technology.

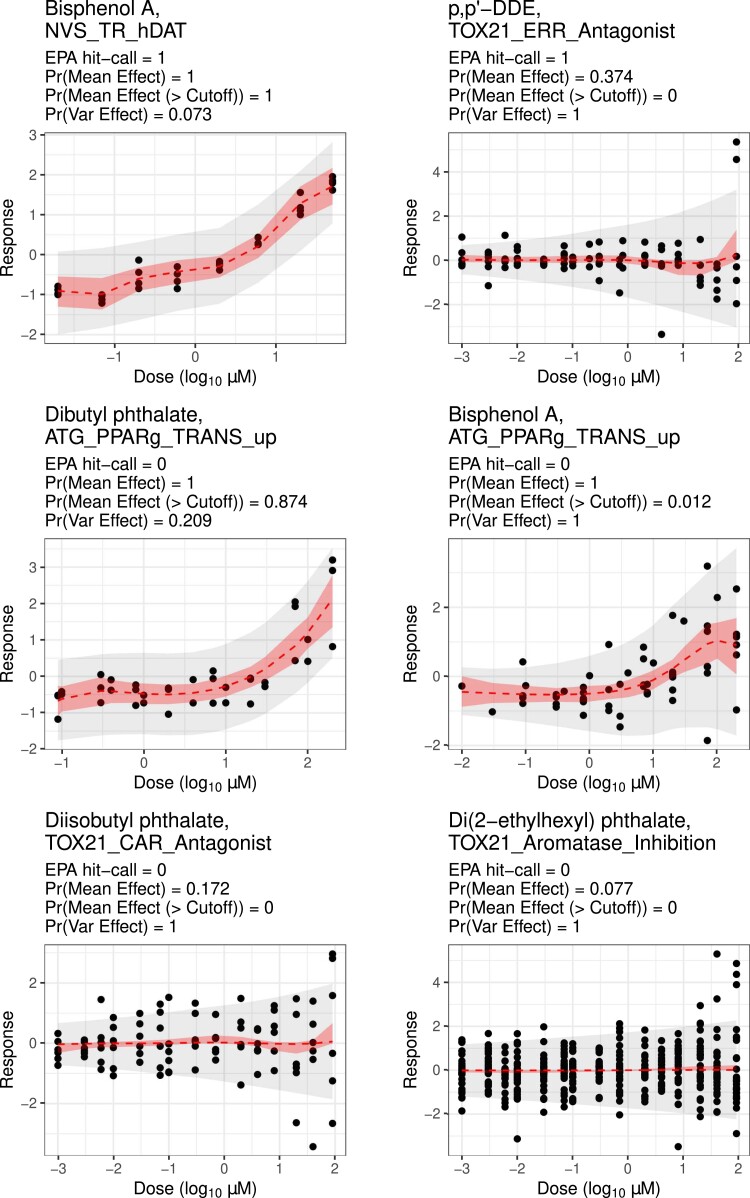

Figure 4 shows estimated dose–response curves from BMC as dashed lines with 95% CIs as shaded areas in red. The light grey shaded areas illustrate 95% posterior predictive intervals for the data points drawn as black dots. ‘Pr(Mean Effect)’ is the mean effect probability for a (chemical , assay endpoint ) pair, which is computed as the posterior mean of . ‘Pr(Mean Effect (> cut-off))’ is a more conservative measure, the probability of mean effects exceeding a cut-off, which is the posterior mean of . Similarly, ‘Pr(Var Effect)’ indicates the variance effect probability whose value is the posterior mean of .

Figure 4.

Fitted results for select chemical-assay endpoint pairs estimated to be active by BMC.

The first row of Figure 4 shows that BMC is able to differentiate dose effects on the mean from dose effects on the variance of dose–response curves. Recall that the EPA’s hit-call is an indication of mean changes. In the left panel, BMC and the EPA agree that mean changes exist, which is supported by an increasing trend. In the right panel, the EPA’s hit-call claims that the average dose–response is not constant. However, BMC estimates that the mean curve is likely to be constant at zero, but with there being clear evidence of heteroscedasticity. Therefore, the first row in Figure 4 suggests that (1) BMC can separate mean and variance effects (at least in some cases); and (2) the EPA’s hit-call might be misled by heteroscedastic variances.

The second row of Figure 4 illustrates some cases where BMC and the EPA’s hit-call disagree, and BMC’s result is more plausible. For both pairs, the EPA’s hit-calls say no activity because their fitted maximum responses by Hill model do not exceed the assay endpoint’s efficacy cut-off (1.174). However, BMC estimates both pairs to be active with high probability. Notice that posterior summaries of and agree on the left panel, while drastically drops compared with on the right. Nonetheless, it is evident that BPA induces heteroscedastic responses. In fact, for these two chemicals, Dibutyl phthalate and BPA, not only do plots show perturbations in dose–response measurements, but also background knowledge supports BMC’s estimates. First, BPA and phthalates are known to disrupt the endocrine system, which potentially results in neurodevelopmental disorders (Tran & Miyake 2017) and obesity (Holtcamp 2012). Second, chemicals activating PPAR (or PPARg) receptors are potential obesogens because PPAR is a master regulator in formulating fat cells (Evans et al. 2004). To be specific, ATG_PPAR_TRANS_up represents an endpoint captured through a human liver cell-based assay. The mechanism of action for obesogens like BPA altering PPAR activity in the liver is well established (Diamante et al. 2021; Marmugi et al. 2012). Therefore, it is not unexpected for BPA and Dibutyl phthalate to be active for the given assay endpoint, ATG_PPAR_TRANS_up.

The third row of Figure 4 shows cases where the EPA’s hit-call can have low power because it misses signals manifest in the variance instead of the mean. Given that phthalates are related to obesity (Holtcamp 2012), we expect disruptive patterns on assay endpoints presenting toxicity of Diisobutyl phthatlate and Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthatlate. However, the EPA’s hit-call suggests that these phthalates are not active at the doses tested. This may be true in terms of mean changes, but variances seem clearly heteroscedastic. Prediction results for held-out pairs are provided in online supplementary material, Section 10.

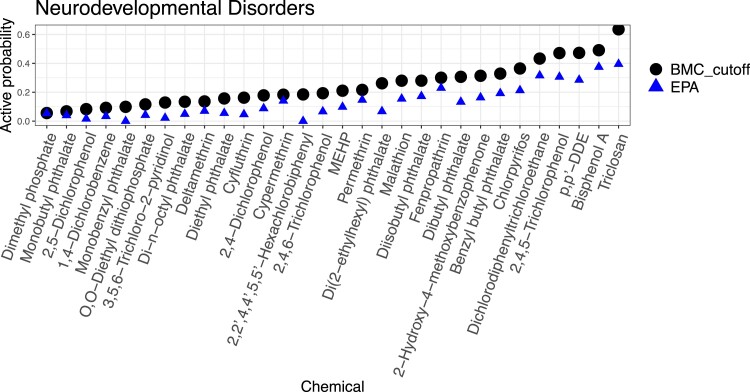

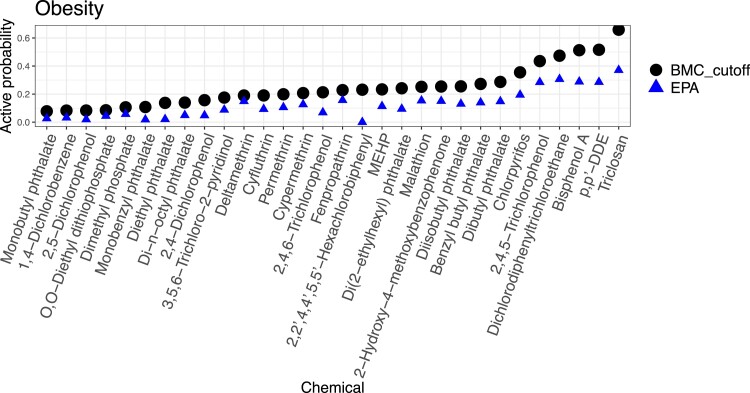

Figures 5 and 6 show chemicals in order of average activity probability with cut-offs, , over assay endpoints related to neurodevelopmental disorders and obesity, respectively. Top five chemicals that are most likely to disrupt biological processes associated with the two diseases are Triclosan, -DDE, BPA, Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), and 2,4,5-Trichlorophenol. In the figures, we notice that the rankings of chemicals by BMC and by the EPA’s hit-call show only subtle differences. But, the actual probabilities computed by BMC are uniformly higher than average hit-calls from EPA. This is because (1) BMC’s active probabilities include heteroscedasticity, while EPA’s hit-call detects the mean activity only; and (2) BMC improves power of tests by borrowing information across multiple chemicals and assay endpoints. Since these bioactivity rankings are based on the data that are currently available, it will be informative to revisit such rankings as data expand.

Figure 5.

Chemical ranks by the average active probability from BMC (dots) and the average hit-call from EPA (triangles) over assay endpoints related to neurodevelopmental disorders.

Figure 6.

Chemical ranks by the average activity probability from BMC (dots) and the average hit-call from EPA (triangles) over obesity-related assay endpoints.

To study sensitivity of rankings to the choice of chemicals, we expanded our analysis to 326 chemicals. They consist of the original 30 chemicals and those screened in Phase I of the ToxCast that have been exclusively used in other toxicity studies including Martin et al. (2010) and Wilson et al. (2014). Within this larger collection, relative positions of the 30 chemicals remained intact with a few exceptions. BPA and Triclosan were positioned lower in the larger set, while Cyfluthrin and MEHP were positioned higher. One of explanations for these shifts is an altered correlation structure among chemicals. The Phase I chemicals are mostly pesticides, and the four chemicals might have different relationships with pesticides from what they had with the 30 chemicals in terms of the mean effect.

One can construct a list of assay endpoints highly likely to be activated by the most active chemicals regarding disease outcomes of interest. Then the assay endpoints in the list are expected to have important implications in progression for the diseases. The ToxCast/Tox21 data include both agonist and antagonist assays, and thus the activated probability encompasses agonist and antagonist directions. Such lists for neurodevelopmental disorders and obesity are available in online supplementary material, Figures 14 and 15, from which fifteen assay endpoints show impacts on both disease classes.

6. Discussion

We have proposed a Bayesian multiple testing approach for inference on activity of chemicals in settings involving multiple chemicals and assay endpoints and possible heteroscedasticity. Our BMC approach can be applied directly in other settings involving a similar matrix-structured experimental design. For example, this is common in pharmaceutical studies assessing drug activity, which will look for evidence of activity for different health outcomes. Also, in microbial genetics, similar designs are conducted but for different types of bacteria and environmental conditions.

The ultimate goal of many analyses using in vitro data is to make inferences on human health and inform protective regulations. Accordingly, chemicals and assay endpoints studied in the ToxCast/Tox21 application are carefully selected: the chemicals are also measured in human epidemiology studies, and the assay endpoints cover a variety of species and several types of tissue targets. Especially we identified assay endpoints for various pathways relevant to specific disease outcomes across multiple data sources. This identification is a highly valuable and meaningful practice in various fields of science including epidemiology and toxicology in that it is adaptive to other disease outcomes and extendable to different data sources as well.

Using the in vitro data, we were able to rank chemicals based on their active probabilities and find the most disruptive chemicals including, but not limited to, Triclosan, -DDE, BPA, DDT, and 2,4,5-Trichlorophenol. It will be interesting to follow up on these top ranking chemicals for neurodevelopmental disorders and obesity disease outcomes to further elucidate their role in human health. In the future, we may consider including chemicals’ molecular structure information to increase power of hypothesis tests, motivated by several Quantitative structure-activity relationship models (Low-Kam et al. 2015; Moran et al. 2021; Wheeler 2019).

When extending in vitro results to in vivo toxicity, doses need to be carefully considered. All the results presented in the paper should be interpreted in terms of tested doses, so we do not conclude a chemical with a high probability of inactivity is inactive at higher doses than those tested. Simultaneously, it is recommended to ensure that the doses tested in vitro can physiologically occur in animals/humans. This recommendation is reinforced by Klaren et al. (2019) in which in vivo toxicity prediction using in vitro assays performs much better with toxicokinetic modelling. Therefore, future research linking in vitro data and in vivo implications could be greatly assisted by assuring dose applicability in animals/humans as well as widening the range of tested doses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brett Winters for identifying assay endpoints relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders and obesity, Evan Poworoznek for sharing computer code, Kelly Moran for helpful comments, and Matthew Wheeler for help in processing ToxCast/Tox21 data. We deeply appreciate helpful comments from the editor, the associate editor and two referees. We thank the first referee for the suggestion of using a factor model for heteroscedasticity.

Contributor Information

Bora Jin, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA.

David B Dunson, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA.

Julia E Rager, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

David M Reif, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA.

Stephanie M Engel, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Amy H Herring, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA.

Supplementary material

Supplementary data is available online at Journal of the Royal Statistical Society online.

Funding

We are grateful for the financial support of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences through grant nos R01ES027498 and R01ES028804.

References

- Bhattacharya A., & Dunson D. B. (2011). Sparse Bayesian infinite factor models. Biometrika, 98(2), 291–306. 10.1093/biomet/asr013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corty R. W., & Valdar W. (2018). Vqtl: An R package for mean-variance QTL mapping. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics, 8(12), 3757–3766. 10.1534/g3.118.200642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamante G., Cely I., Zamora Z., Ding J., Blencowe M., Lang J., Bline A., Singh M., Lusis A. J., & Yang X. (2021). Systems toxicogenomics of prenatal low-dose BPA exposure on liver metabolic pathways, gut microbiota, and metabolic health in mice. Environment International, 146, 106260. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.106260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix D. J., Houck K. A., Martin M. T., Richard A. M., Setzer R. W., & Kavlock R. J. (2007). The ToxCast program for prioritizing toxicity testing of environmental chemicals. Toxicological Sciences, 95(1), 5–12. 10.1093/toxsci/kfl103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECHA (2017). The use of alternatives to testing on animals for the REACH regulation. European Chemicals Agency. 10.2823/023078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R. M., Barish G. D., & Wang Y.-X. (2004). PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nature Medicine, 10(4), 355–361. 10.1038/nm1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filer D. L., Kothiya P., Setzer R. W., Judson R. S., & Martin M. T. (2017). tcpl: The ToxCast pipeline for high-throughput screening data. Bioinformatics, 33(4), 618–620. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtcamp W. (2012). Obesogens: An environmental link to obesity. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(2), a62–a68. 10.1289/ehp.120-a62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J.-H., Sedykh A., Huang R., Xia M., & Tice R. R. (2015). A data analysis pipeline accounting for artifacts in Tox21 quantitative high-throughput screening assays. Journal of Biomolecular Screening, 20(7), 887–897. 10.1177/1087057115581317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R., et al. (2014). Profiling of the Tox21 10k compound library for agonists and antagonists of the estrogen receptor alpha signaling pathway. Scientific Reports, 4(1), 1–9. 10.1038/srep04958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson R. S., Houck K. A., Kavlock R. J., Knudsen T. B., Martin M. T., Mortensen H. M., Reif D. M., Rotroff D. M., Shah I., Richard A. M., & Dix D. J. (2010). In vitro screening of environmental chemicals for targeted testing prioritization: The ToxCast project. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118(4), 485–492. 10.1289/ehp.0901392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaren W. D., Ring C., Harris M. A., Thompson C. M., Borghoff S., Sipes N. S., Hsieh J.-H., Auerbach S. S., & Rager J. E. (2019). Identifying attributes that influence in vitro-to-in vivo concordance by comparing in vitro Tox21 bioactivity versus in vivo drugmatrix transcriptomic responses across 130 chemicals. Toxicological Sciences, 167(1), 157–171. 10.1093/toxsci/kfy220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapen D., Stinckens E., Cavallin J. E., Ankley G. T., Holbech H., Villeneuve D. L., & Vergauwen L. (2020). Toward an AOP network-based tiered testing strategy for the assessment of thyroid hormone disruption. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(14), 8491–8499. 10.1021/acs.est.9b07205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren Y., Bell R., & Volinsky C. (2009). Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer, 42(8), 30–37. 10.1109/MC.2009.263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie D. S., Kohn R., & Nott D. J. (2007). A general approach to heteroscedastic linear regression. Statistics and Computing, 17(2), 131–146. 10.1007/s11222-006-9013-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., & Zhang N. R. (2010). Bayesian variable selection in structured high-dimensional covariate spaces with applications in genomics. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(491), 1202–1214. 10.1198/jasa.2010.tm08177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Low-Kam C., Telesca D., Ji Z., Zhang H., Xia T., Zink J. I., & Nel A. E. (2015). A Bayesian regression tree approach to identify the effect of nanoparticles’ properties on toxicity profiles. Annals of Applied Statistics, 9(1), 383–401. 10.1214/14-AOAS797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marmugi A., Ducheix S., Lasserre F., Polizzi A., Paris A., Priymenko N., Bertrand-Michel J., Pineau T., Guillou H., Martin P. G., & Mselli-Lakhal L. (2012). Low doses of bisphenol A induce gene expression related to lipid synthesis and trigger triglyceride accumulation in adult mouse liver. Hepatology, 55(2), 395–407. 10.1002/hep.24685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. T., Dix D. J., Judson R. S., Kavlock R. J., Reif D. M., Richard A. M., Rotroff D. M., Romanov S., Medvedev A., Poltoratskaya N., Gambarian M., Moeser M., Makarov S. S., & Houck K. A. (2010). Impact of environmental chemicals on key transcription regulators and correlation to toxicity end points within EPA’s toxcast program. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 23(3), 578–590. 10.1021/tx900325g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnih A., & Salakhutdinov R. R. (2008). Probabilistic matrix factorization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 1257–1264). Curran Associates, Inc.

- Moran K. R., Dunson D. B., & Herring A. H. (2021). Bayesian joint modeling of chemical structure and dose response curves. Annals of Applied Statistics, 15(3), 1405–1430. 10.1214/21-aoas1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelon B., & Dunson D. B. (2004). Bayesian isotonic regression and trend analysis. Biometrics, 60(2), 398–406. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00184.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré G., Cook N. R., Ridker P. M., & Chasman D. I. (2010). On the use of variance per genotype as a tool to identify quantitative trait interaction effects: A report from the women’s genome health study. PLoS Genetics, 6(6), e1000981. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purushotham S., Liu Y., & Kuo C.-C. J. (2012). Collaborative topic regression with social matrix factorization for recommendation systems. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 691–698). arXiv.

- Ritz C. (2010). Toward a unified approach to dose–response modeling in ecotoxicology. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 29(1), 220–229. 10.1002/etc.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnegård L., & Valdar W. (2012). Recent developments in statistical methods for detecting genetic loci affecting phenotypic variability. BMC Genetics, 13(1), 63. 10.1186/1471-2156-13-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheel I., Ferkingstad E., Frigessi A., Haug O., Hinnerichsen M., & Meze-Hausken E. (2013). A Bayesian hierarchical model with spatial variable selection: The effect of weather on insurance claims. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics), 62(1), 85–100. 10.1111/j.1467-9876.2012.01039.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. G., & Berger J. O. (2006). An exploration of aspects of Bayesian multiple testing. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 136(7), 2144–2162. 10.1016/j.jspi.2005.08.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. G., & Berger J. O. (2010). Bayes and empirical-Bayes multiplicity adjustment in the variable-selection problem. The Annals of Statistics, 38(5), 2587–2619. 10.1214/10-AOS792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tansey W., Tosh C., & Blei D. M. (2019). ‘A Bayesian model of dose-response for cancer drug studies’, arXiv, arXiv:1906.04072, preprint: not peer reviewed.

- Thomas D. C., Conti D. V., Baurley J., Nijhout F., Reed M., & Ulrich C. M. (2009). Use of pathway information in molecular epidemiology. Human Genomics, 4(1), 21. 10.1186/1479-7364-4-1-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice R. R., Austin C. P., Kavlock R. J., & Bucher J. R. (2013). Improving the human hazard characterization of chemicals: A Tox21 update. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121(7), 756–765. 10.1289/ehp.1205784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran N. Q. V., & Miyake K. (2017). Neurodevelopmental disorders and environmental toxicants: Epigenetics as an underlying mechanism. International Journal of Genomics, 2017, 7526592. 10.1155/2017/7526592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler M. W. (2019). Bayesian additive adaptive basis tensor product models for modeling high dimensional surfaces: An application to high-throughput toxicity testing. Biometrics, 75(1), 193–201. 10.1111/biom.12942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A., Reif D. M., & Reich B. J. (2014). Hierarchical dose-response modeling for high-throughput toxicity screening of environmental chemicals. Biometrics, 70(1), 237–246. 10.1111/biom.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., et al. (2012). FTO genotype is associated with phenotypic variability of body mass index. Nature, 490(7419), 267–272. 10.1038/nature11401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.