Abstract

Introduction:

Metastatic uveal melanoma is associated with poor prognosis and few treatment options. Tebentafusp recently became the first FDA-approved agent for metastatic uveal melanoma.

Areas covered:

In this review, we describe the mechanism of action of tebentafusp as well as preclinical data showing high tumor specificity of the drug. We also review promising early phase trials in which tebentafusp demonstrated activity in metastatic uveal melanoma patients with an acceptable toxicity profile that included cytokine-mediated, dermatologic-related, and liver-related adverse events. Finally, we summarize findings from a pivotal phase III randomized trial in which tebentafusp demonstrated significant improvement in overall survival in comparison with investigator choice therapy.

Expert opinion:

Tebentafusp has transformed the treatment paradigm for metastatic uveal melanoma and should be the preferred frontline agent for most HLA-A*0201 positive patients. However, patients with rapidly progressing disease or high tumor benefit may not derive the same benefit. Areas of future study should focus on its role in the adjuvant setting as well as strategies to improve efficacy of tebentafusp in the metastatic setting.

Keywords: gp100, Immune-mobilizing monoclonal T cell receptor against cancer, Immunotherapy, Tebentafusp, Uveal Melanoma

1. INTRODUCTION

Although uveal melanoma (UM) is a rare disease with an incidence of 5.1 per million in the US, it comprises 85% of cases of primary ocular malignancies[1]. Local therapies, which include enucleation and globe-sparing approaches such as brachytherapy and proton beam therapy, effectively manage the primary tumor in over 95% of cases[2]. However, up to 50% of patients will develop metastatic disease, most commonly to the liver, lung, bone, and skin. The risk can be even higher based on certain clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular features [3,4] . The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) system, which uses tumor size, ciliary body involvement, and extraocular extension to categorize patients by stage, predicts increased risk of metastasis in higher stage disease[5]. Five-year metastasis-free survival is estimated as 97% for stage I disease and 25% for stage IIIC disease[6]. Combining AJCC tumor classification with cytogenetics analysis improves prognostication[7]. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Project classifies UM into class A, B, C, or D based on the presence or absence of chromosome 3 monosomy and chromosome 8q gain[8,9]. Class A patients, which show disomy 3 and 8, have the best prognosis while those with Class B, C, or D disease have increased risk of metastasis[8-10]. DecisionDx-UM, which is a 15-gene expression panel, uses next-generation sequencing to classify tumors as class 1 or class 2. Five-year risk of metastatic disease for class 2 tumors is over 70%[11].

For patients who develop metastatic uveal melanoma, prognosis is poor and median survival is estimated at 12 months[12-16]. A meta-analysis of 29 trials for metastatic uveal melanoma between 2000 and 2016 identified a 1-year overall survival (OS) of 43% regardless of prior treatment[16]. For some patients with oligometastatic liver disease, surgical resection and other regional approaches such as intra-arterial chemotherapy, hepatic artery chemoembolization, immunoembolization,radioembolization, isolated hepatic perfusion, and percutaneous hepatic perfusion can improve disease control, though careful patient selection is critical and survival benefit is largely unclear[17-24] Until recently, advances in systemic treatments have not been shown to meaningfully improve survival[13]. Chemotherapeutic agents such as dacarbazine, temozolomide, and cisplatin have not demonstrated significant clinical activity[25]. Unlike its cutaneous counterpart, metastatic uveal melanoma is also largely refractory to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Single-agent checkpoint inhibitors have had disappointing clinical trial results. In one phase II trial, single-agent ipilimumab led to a 1-year OS of 22%, which was the primary endpoint; it did not lead to any partial or complete responses, and median OS was 6.8 months[26]. A phase II trial of single-agent tremelimumab, which had a primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) at 6 months, led to a 9.1% 6-month PFS rate, no responses, and an OS of 12.8 months[27]. A retrospective review of patients treated with PD-1 or PD-L1 blockade yielded an objective response rate (ORR) of 3.6% and median OS of 7.6 months[28].

Dual checkpoint blockade has had modest success. In the phase II PROSPER trial, which had a primary endpoint of ORR, the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab led to an ORR of 18%, a median OS of 19.1 months, and one-year OS rate of 56%[29]. The phase II GEM-1402 trial had a primary endpoint of 12-month OS, which was 52% with nivolumab and ipilimumab[30]. ORR was 11.5% and median OS was 12.7 months[30]. While these outcomes were more promising than those of single agent immunotherapy trials, they are still comparable to historical survival data for patients who are treated for metastatic disease[15]. They also remain considerably worse when compared to outcomes of checkpoint inhibitor therapy for cutaneous melanoma[31,32]. Uveal melanoma has a low tumor mutation burden, relatively low PD-L1 expression, and tends to metastasize to an immunosuppressive liver environment, which may explain its relative insensitivity to checkpoint blockade[33-35].

Targeted therapies have also had little success in treating metastatic uveal melanoma. Selumetinib, a mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) inhibitor, was compared to chemotherapy in a randomized phase II trial with a primary endpoint of PFS. Median PFS was significantly higher with selumetinib compared to chemotherapy (15.9 weeks vs. 7 weeks, p<0.001) but the magnitude of clinical benefit was small. Selumetinib led to an ORR of 14%, and median OS was not significantly different compared to chemotherapy (11.8 months vs. 9.1 months, p=0.09)[36]. In a subsequent phase III trial (SUMIT), selumetinib plus dacarbazine was compared to placebo plus dacarbazine and the primary endpoint was PFS. Median PFS was 2.8 months (selumetinib plus dacarbazine) vs. 1.8 months (dacarbazine alone), which was not a significant improvement (p=0.32). The ORR was 3% with selumetinib plus dacarbazine, and OS was not significantly improved (HR 0.75, p=0.40)[37]. The randomized phase II SelPAC trial, which compared selumetinib plus dacarbazine to dacarbazine alone, met its primary endpoint of PFS, but the PFS improvement was modest (4.8 months vs. 3.4 months, p=0.02). ORR, a secondary endpoint, was 14% (selumetinib plus dacarbazine) and 4% (dacarbazine). Median OS, another secondary endpoint, was not significantly different between the treatment and control arms (9 months vs. 10 months, p=0.469)[38].

Until recently, there were no FDA-approved treatments for metastatic uveal melanoma. Due to disappointing results seen with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapies, there continues to be a significant unmet need for patients with this disease.

2. TEBENTAFUSP: DRUG INTRODUCTION

2.1. Mechanism of action and pre-clinical data

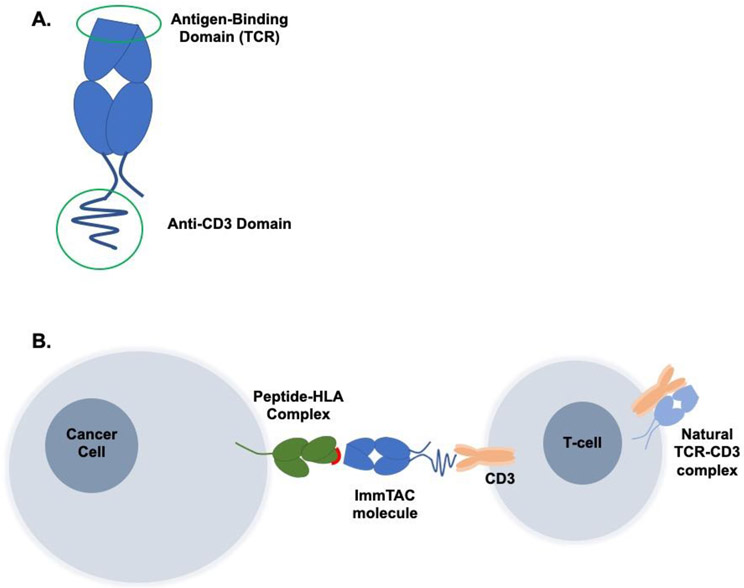

Tebentafusp (IMCgp100) is a first-in-class immune-mobilizing monoclonal T cell receptor against cancer (ImmTAC). ImmTAC molecules are bispecific agents that are engineered to include a high-affinity monoclonal T cell receptor (mTCR) that recognizes a specific peptide-HLA complex, fused to an anti-CD3 single-chain antibody fragment (scFv) that engages T cells (Figure 1)[39]. These molecules have been shown to successfully activate and redirect cytotoxic T cells to kill tumor cells and induce a polyclonal response[40,41].

Figure 1.

A) ImmTAC molecules are bispecific molecules that include an antigen-binding T-cell receptor (TCR) and an anti-CD3 domain. B) The antigen-binding TCR recognizes a specific peptide-HLA complex on the target tumor cell, while the anti-CD3 fragment binds to CD3 on circulating T cells, thus redirecting and activating T cells for tumor cell killing

Tebentafusp consists of a mTCR that recognizes glycoprotein 100 (gp100), a peptide presented by HLA-A*0201 that is highly expressed on uveal melanoma cells[42]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that IMCgp100 has a very high binding affinity for HLA-A-gp100, with a KD of 15pM and an EC50 less than 100pM[40]. It has relatively weak binding to CD3 (with a KD in the nM range), which allows for highly specific tumor cell binding followed by activation and redirection of polyclonal CD8+ and CD4+ T cells to elicit cytotoxic activity against melanoma cells[41]. Beyond T cell cytotoxic activity, IMCgp100 also induces T cells to release broad range of cytokines and chemokines including IL-6, IL-2, and TNF-a, further enhancing its potential anti-cancer immune activity[41]. IMCgp100 activity in T-cell activation was observed at a concentration of 1pM, with maximal response seen at 1nM and off-target effects seen only at concentrations much higher than 1nM, indicating high tumor antigen specificity and a wide therapeutic window[43]. In vitro activity of IMCgp100 correlated with levels of gp100-HLA-A*02 expression[43].

2.2. Drug Metabolism

Tebentafusp has an estimated half-life of 6-8 hours with a distribution that is primarily limited to the central blood volume (Vss approximately 6-7 L)[44]. It is expected to be catabolized into small peptides and amino acids[45].

3. EARLY PHASE CLINICAL TRIALS

3.1. First-in-man phase I/II trial

Encouraging preclinical data formed the basis for a multicenter, first-in-man phase I/II trial of tebentafusp in metastatic or unresectable melanoma (NCT01211262, Table 1) [46]. This trial included 84 HLA-A*0201 positive patients who mostly had cutaneous (n=61) and uveal (n=19) melanoma and who were treated with a median of 1 prior line of therapy. Weekly (arm 1, n=66) and daily (arm 2, n=18) dosing were explored at a range of doses [arm 1: 5-900 ng/kg dose escalation; arm 2: once daily x 4 days every 3 weeks using 10 to 50mcg per dose]. Hypotension was observed as the dose-limiting toxicity for patients who received 900 ng/kg, so the maximum tolerated weekly dose was 600 ng/kg (or 50 mcg flat dose). The recommended phase II dose for weekly dosing was set at 50 mcg. ORR by RECIST criteria was 8.7% (all partial responses), while 55% of patients had stable disease [46]. Of the patients who received 600 ng/kg or greater (n=26), response rate was higher at 15%, suggesting a dose-response relationship [47-49]. Three uveal melanoma patients achieved a partial response, for an ORR of 16.7% amongst patients with this disease. Median duration of response was 10.5 months, and median survival was 33.4 months. One-year OS rate was 65% (95% CI, 48-78%) and was similar between patients with uveal melanoma and cutaneous melanoma [46].

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical Trials

| Trial | Phase | Study Interventions | Study Size | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01211262 | I/II | IMCgp100 weekly IV fixed dosing (Arm 1) vs. IMCgp100 daily IV dosing (Arm 2) | N = 84 | [46] |

| NCT02570308 | I/II | Three-week step-up dosing regimen with 20 mcg for week 1, 30 mcg for week 2, then dose escalation for week 3, with 68 mcg as the identified R2PD for week 3 | N = 42 (Phase I) N = 127 (Phase II) |

[44,51] |

| NCT03070392 | III | Tebentafusp (20 mcg D1, 30 mcg D8, 68 mcg thereafter) vs. Investigator’s choice systemic therapy | N = 378; Tebentafusp (N = 252) vs. Placebo (N = 126) | [53] |

Tebentafusp was well-tolerated, and toxicities were mostly cytokine-mediated or dermatologic (Table 2). Cytokine release syndrome (CRS), considered to be an on-target, on-tumor toxicity, was seen in 60% of patients, though cases were generally mild and no grade ≥3 cases were reported [46]. Dermatologic toxicities, which are considered on-target, off-tumor, manifested as rash (68%) and pruritis (70%). Common grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) were rash (26%) and lymphopenia (13%), which was thought to be an on-target effect specific to melanocytic gp100 and peripheral T-cell redirection. Eight percent of patients experienced grade ≥3 hypotension [46]. Toxicities were usually reversible within 24 hours, and most were limited to the first two weeks of treatment.

Table 2.

Summary of Adverse Events for Patients who received Tebentafusp on Clinical Trial

| Trial | Phase | Any Grade Adverse Events n (%) |

Grade ≥3 Adverse Events n (%) |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NCT01211262 N=84 |

I/II | Dermatologic | Rash: 57 (68) Pruritis: 59 (70) Skin exfoliation: 24 (29) Dry skin: 23 (27) Erythema: 19 (23) |

Rash: 22 (26) Pruritis: 1(1) Skin exfoliation: 0 (0) Dry skin: 0 (0) Erythema: 0 (0) |

[46] |

| Cytokine Release Syndrome | CRS: 50 (60) Other CRS-related: 8 (10) |

CRS: 0 (0) Other CRS-related: 8 (10) |

|||

|

NCT02570308 N=42 |

I | Dermatologic | Rash 13 (31) Rash generalized: 9 (21.4) Pruritis: 30 (71.4) Skin exfoliation: 5 (11.9) Dry skin: 27 (64.3) Erythema: 17 (40.5) Pigment Change: 18 (42.8) |

Rash 2 (4.8) Rash generalized: 1 (2.4) Pruritis: 2 (4.8) Skin exfoliation: 0 (0) Dry skin: 0 (0) Erythema: 2 (4.8) Pigment Change: 0 (0) |

[44] |

| Cytokine Release Syndrome | CRS: 38 (90) CRS requiring tocilizumab: 0 (0) CRS requiring supplemental oxygen: 1 (2) |

CRS: 1 (2%) | |||

| Hepatic Toxicity | AST increased: 8 (19) Alkaline phosphatase increased: 8 (19) Hepatic pain: 7 (16.7) Hyperbilirubinemia: 6 (14.3) |

AST increased: 4 (9.5) Alkaline phosphatase increased: 2 (4.8) Hepatic pain: 0 (0) Hyperbilirubinemia: 2 (4.8) |

|||

|

NCT02570308 N=127 |

II | Dermatologic | Rash: 81 (64) Pruritis: 85 (67) |

Rash: 16 (13) | [51] |

| Cytokine Release Syndrome | CRS: 109 (86) | CRS: 5 (4) | |||

| Hepatic Toxicity | Not reported | AST increased: 6 (5) | |||

|

NCT03070392 N=252 |

III | Dermatologic | Rash: 203 (83) Pruritis: 169 (69) Dry skin: 72 (29) Erythema: 56 (23) |

Rash: 45 (18) Pruritis: 11 (4) Dry skin: 0 (0) Erythema: 0 (0) |

[53] |

| Cytokine Release Syndrome | CRS: 217 (89) | CRS: 2 (1) | |||

| Hepatic Toxicity | AST increased: 47 (19) ALT increased: 43 (18) Hyperbilirubinemia: 21 (9) |

AST increased: 11 (4) ALT increased: 7 (3) Hyperbilirubinemia: 5 (2) |

Analysis of post-treatment patient serum samples revealed increased levels of IFN-inducible chemokines CXCL10, CXCL11, IL2, IL6, and IL10, with CXCL10 showing the greatest increase [46]. Induction of serum cytokines appeared to be transient and reached maximal levels 8-24 hours after the dose before returning to baseline. CXCL10, however, remained elevated compared to baseline. Increases in serum CXCL10 and CXCL11 were associated with longer overall survival [46]. Post-treatment tumor biopsies exhibited increased intratumoral CD3+, CD4+, and CD8 T-cells, further confirming the drug’s mechanistic role in T-cell redirection and immune activation [46]. A two-fold increase in PD-L1 expression was in seen in five of nine post-treatment tumor biopsies [46].

3.2. Phase I/II Trial with step-up dosing regimen

Given the dose-response relationship and dose-limiting hypotension/CRS seen early on in the treatment course in the first-in-man trial, a second phase I trial (Table 1) was conducted in an effort to increase the maximum tolerated dose by using a three-week step-up dosing regimen [44]. Nineteen HLA-A*0201 positive patients with advanced uveal melanoma were included in the initial dose expansion cohort. These patients were heavily pretreated and had a median of 4 lines of prior therapy[44,50]. Each patient received 20 mcg of tebentafusp on C1D1, 30 mcg on C1D8, then an escalated dose on C1D15 and thereafter (ranging from 54 mcg to 73 mcg). Each cycle consisted of 4 weeks. Dose-limiting transaminase elevation was observed in 2 of 4 patients treated at the 73 mcg dose, which was deemed not tolerable [44]. The observed transaminase elevations resolved within 1 week without requiring steroids, and all patients were able to tolerate restarting the drug at a reduced dose. None of the six patients treated with 68 mcg experienced a dose-limiting toxicity, so 68 mcg was established as the recommended phase II dose [44]. Notably, the step-up dosing regimen permitted a 36% increase in dose compared with what was tolerable using a flat dosing regimen. Twenty-three patients were included in the subsequent expansion cohort and were treated with 68 mcg on C1D15 and thereafter.

The median number of cycles completed were 7.5 (dose escalation group) and 6 (dose expansion group). ORR was 11.9% (confirmed partial response was observed in 5 patients), and 55% of patients achieved any degree of tumor size reduction. Median OS was 25.5 months, and one-year OS rate was 67% [44], representing a significant improvement over historical survival estimates of 12 months for median OS and around 50% for 1-year OS rate[16].

Common adverse events included pyrexia (90%) pruritis (71%), nausea (74%), and fatigue (71%); 71% of patients experienced a grade ≥3 adverse event, which included hypophosphatemia (14%), hypotension (12%), abdominal pain (12%), fatigue (10%), and AST elevation (10%) [44]. Thirty-eight (90%) patients experienced CRS, and most (90%) cases were grade 1 or 2 (Table 2). CRS was mostly reversible with IV fluids and in some cases required a short course of corticosteroids. Acute transaminase elevation was seen in 9 (21%) patients, usually early in the treatment course in the setting of CRS, whereas chronic LFT elevations were associated with disease progression. Skin toxicities included rash (83%), pruritis (83%), dry skin (64%), and were grade 1 or 2 in 67% of cases. Patients were treated with antihistamines and topical steroids. TRAE’s became less frequent and less severe with repeated dosing[44]. A post-hoc analysis of the 24 patients who experienced rash of any grade within 7 days of the first dose showed that these patients had longer survival compared to patients who did not have rash (HR 0.23, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.54). One-year OS rate was 83% among patients who experienced rash (95% CI, 68 to 98) vs. 44% among patients who did not have rash (95% CI, 21 to 67).

To assess the pharmacodynamic response to tebentafusp, serum cytokine profiles were assessed pre-treatment and at 8 hours and 12-24 hours after the first and third doses [44]. The greatest increases relative to baseline were seen for CXCL10, CXCL11, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, and interferon (IFN)y, with most (60-95%) patients showing a greater than 10-fold increase. Most rises in serum markers were transient, but CXCL10 and CXCL11 levels remained elevated relative to baseline. Changes in serum biomarkers were not associated with longer OS. Below median (<6 fold) increases in IL-10, however, was associated with greater tumor shrinkage, consistent with the immunosuppressive role of IL-10 [44]. Six patients had pre-treatment and during-treatment tumor biopsies available. On-treatment biopsy samples had a higher concentration of CD3+ T cells and an increase in CD4+ and CD8+ immune cells compared to baseline biopsy samples [44].

A subsequent phase II trial treated a total of 127 HLA-A*0201 positive patients, including 23 patients from the previously described phase I expansion cohort, with the recommended phase II dosing regimen (Table 1) [51]. All patients had received at least 1 prior therapy for metastatic disease, and 58% had elevated LDH. Most (70%) patients had an ECOG score of 0. Patients were treated with weekly IV tebentafusp (20 mcg on C1D1, 30 mcg on C1D8, 68 mcg on C1D15 and thereafter). The primary endpoint was ORR, and secondary endpoints included safety, OS, and PFS. At a median follow-up of 19.6 months, ORR was low at 5%, with 6 patients achieving a partial response by RECIST criteria. Median duration of response was 8.7 months (95% CI: 5.6-24.5). Although ORR was low, 44% of patients had a reduction in target lesions. Median PFS was 2.8 months (95% CI: 2-3.6), median OS was 16.8 months (95% CI, 12.9-21.3), and the 12-month OS rate was 62% (95% CI: 53-70%).

Common TRAEs included cutaneous and cytokine-mediated events, consistent with predicted on-target effects (Table 2) [51]. They included pruritis (67%), pyrexia (80%), chills (64%), and grade ≥3 AEs included maculopapular rash (13%), hypotension (8%), and increased AST (6%). TRAEs were manageable; they also occurred less frequently and were less severe after the third dose. Patients who developed rash within a week of starting the drug (64% of patients) had better survival outcomes, with median survival of 22.5 months compared to 10.3 months among patients who did not develop rash [51].

Despite promising overall survival, there was a low rate of overall response by RECIST criteria, indicating that radiographic assessment may underestimate survival benefit [51]. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) levels, which are associated with treatment response in other disease settings, were measured at baseline and at weeks 5 and 9 on treatment using a custom panel of mutations commonly found in uveal melanoma from Natera Inc. [52]. In data presented at ESMO in 2021, 116 patients had evaluable ctDNA at baseline, and 99 patients had evaluable ctDNA at baseline and at week 9. Baseline ctDNA levels correlated significantly with tumor size [52]. At week 9, 70% of patients had any ctDNA reduction and 14% of patients achieved ctDNA clearance. ctDNA reduction was associated with greater mean tumor shrinkage, less tumor growth, and was significantly associated with better overall survival (p<0.0001). Among patients with a best radiographic response of progressive disease, those with a ≥ 0.5 log reduction in ctDNA by week 9 had improved OS compared to those with < 0.5 log ctDNA reduction. Among the patients who achieved complete ctDNA clearance, most had either stable (57%) or progressive (29%) disease on imaging, and 100% were alive at 1 year [52].

4. RANDOMIZED PHASE III TRIAL

An open-label randomized phase III trial was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of tebentafusp in patients with previously untreated metastatic uveal melanoma[53]. 378 HLA-A*0201-positive patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive first-line tebentafusp or investigator choice of therapy (single-agent pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, or dacarbazine). The single-agent control arm was used because the trial was designed before data from the dual checkpoint blockade trials (GEM-1402 and PROSPER) were known and because of concerns for toxicity with dual checkpoint blockade[29,30]. Patients were stratified according to LDH. Inclusion criteria included HLA-A*0201 positivity, lack of prior systemic or liver-directed treatment, ECOG of 0 or 1, and measurable disease by RECIST 1.1 criteria. Exclusion criteria included CNS metastases, treatment with steroids for autoimmune disease, or receipt or other systemic immunosuppressive treatment. The primary endpoint of the study was OS in both the intention-to-treat population and in the prespecified population of patients who developed a rash of any grade within 1 week after treatment initiation. Secondary endpoints included disease control, ORR, and PFS.

Patients who were randomized to receive tebentafusp were dosed 20 mcg IV on C1D1, 30 mcg IV on C1D8, and 68 mcg IV on C1D15 and weekly thereafter. Among patients randomized to the investigator’s choice control group, 82% (n=103) were assigned to receive pembrolizumab, 13% (n=16) were assigned to receive ipilimumab, and 6% (n=7) were assigned to receive dacarbazine [53]. Crossover was not initially permitted, but after the first interim analysis identified a survival benefit, patients in the control group were permitted to cross over to receive tebentafusp.

Baseline clinical characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups. Median patient age was 64 years in the tebentafusp group and 66 years in the control group. Thirty six percent of patients in the study had elevated LDH, 73% had an ECOG of 0, 44% had both hepatic and extrahepatic metastases, and median time since initial diagnosis was 2.8 years.

The first planned interim analysis was performed after a median follow-up time of 14.1 months, at which time 150 deaths had occurred in the intention-to-treat population [53]. OS rate at 1 year was 73% (tebentafusp group) compared to 59% (control group) in the intention-to-treat population. Median OS was 21.7 months (tebentafusp) compared to 16.0 months (investigator’s choice therapy). The hazard ratio (HR) for death was 0.51 (95% CI, 0.37-0.71), which was statistically significant (p<0.001). In subgroup analyses, the overall survival benefit with tebentafusp was mostly consistent, though there appeared to be less benefit with tebentafusp compared to patients treated with ipilimumab and among patients with either ECOG 1 performance status or larger metastatic lesions (M1b or M1c disease).

Six-month PFS was 31% (tebentafusp) compared to 19% (control), for a HR of 0.73 (95% CI 0.58-0.94) that was significant (p=0.01). ORR was only 9% (95% CI, 6-13) in the tebentafusp group and 5% (95% CI, 2-10) in the control group. Forty-six percent (95% CI, 39-52) of patients who received tebentafusp had disease control (complete response, partial response, or stable disease for 12+ weeks) compared to 27% (95% CI, 20 to 36) in the control group.

While the OS benefit of tebentafusp was both clinically and statistically significant, the PFS benefit was relatively low despite being statistically significant. The rate of radiographic tumor response with tebentafusp was also low at 9%; while numerically higher than the control group, it was not statistically significant. Among patients with radiographic disease progression, those who received tebentafusp still had longer survival than those in the control arm, suggesting a benefit with tebentafusp even in the absence of a radiographic response. This disconnect between radiographic response assessment and OS, seen previously in the early phase trials, is consistent with an immunological pattern of clinical response. A similar pattern of response, for instance, was observed with ipilimumab when compared with a gp100 vaccine for patients with metastatic melanoma. While single-agent ipilimumab led to a relatively low ORR of 10.9%, it significantly improved median OS (10.1 months vs. 6.4 months, HR 0.66, p=0.003)[54].

As in early phase trials, two major types of treatment-related adverse events were observed in the tebentafusp arm (Table 2): cytokine-mediated, including pyrexia (76%), hypotension (38%), and chills (47%), and skin-related, including rash (83%), pruritis (69%), and erythema (23%). There were more grade 3-4 TRAEs seen in the tebentafusp group (44%) than in the control group (17%). Liver-related toxicities were thought to be mostly due to disease progression rather than a drug-related effect. The rate of treatment discontinuation due to treatment-related adverse events was low in both groups (2% in the tebentafusp group, 5% in the control group). No treatment-related deaths were seen in either group. Most adverse events observed in the tebentafusp arm occurred during the first 4 weeks of treatment, and the incidence and severity decreased with each subsequent dose. Hospitalization was uncommonly required to administer the fourth dose and beyond.

Cytokine release syndrome was observed in 89% of patients in the tebentafusp group, but 99% of those patients had at most grade 1-2 symptoms and symptoms mostly occurred within hours of administering the first three doses. Most patients who experienced CRS were treated with a combination of antipyretics and intravenous fluids; although some required systemic glucocorticoids, escalation to tocilizumab and pressors for hypotension was uncommon. Skin toxicities and were usually manageable with acetaminophen, diphenhydramine, and topical steroids.

Based on phase II data suggesting a relationship between appearance of rash and increased survival when treated with tebentafusp, a prespecified OS analysis was performed for the 149 patients treated with tebentafusp who developed rash within a week. These patients had a significantly longer median OS compared to the control group [27.4 months (95% CI, 20.2 to not reached) vs. 16.0 months (95% CI, 9.7-18.4)], p<0.001. However, rash was not a significant independent predictor of OS benefit with tebentafusp in a multivariate Cox model.

The authors concluded that first-line treatment with tebentafusp significantly prolonged overall survival compared to investigator’s choice of treatment with either pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, or dacarbazine. The one-year OS rate of 73% seen with tebentafusp was higher than one year survival rates previously reported with dual checkpoint blockade[29,30] and in meta-analyses of patients treated for metastatic disease[15]. Median OS of the control arm also outperformed historical controls, which further highlights the benefit seen with tebentafusp.

5. POST-MARKETING SURVEILLANCE

The most common adverse events seen with tebentafusp across clinical trials and in clinical practice can be grouped into dermatologic, cytokine release syndrome-related, and liver-related toxicities (Table 2). These toxicities have overlap with the safety profile of other immunotherapies. Table 3 compares the characteristics of ImmTAC molecules to other immunotherapy drug classes that activate and/or engage T cells.

Table 3.

Comparison of Immune-mobilizing monoclonal T-cell receptors (IMMTac) with other Immunotherapies that Engage and/or Activate T cells

| Drug Class |

Drug Examples (FDA- approved) |

Design and Mechanism of Action |

Advantages | Disadvantages | Notable Adverse Events |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune-mobilizing monoclonal T-cell receptor (IMMTac) | Tebentafusp | Bispecific molecule consisting of a monoclonal T-cell receptor (which recognizes a specific HLA-peptide complex) fused to an anti-CD3 antibody. Results in recruitment of polyclona1 T cells to tumor cells | Very high TCR affinity for tumor-specific target antigen (HLA-peptide complex) High specificity for target antigen Access to a broad range of tumor targets: Can be designed to target both intracellular and extracellular antigens presented by HLA |

Restricted to a specific HLA subtype |

|

[66] |

| Bispecific T-cell Engager | Blinatumomab | Bispecific antibody that consists of two separate single-chain variable regions, one that recognizes a tumor-associated antigen (ex. CD19) and another that recognizes the Fc region of the CD3 receptor on T cells. Acts as a linker between T cells and a specific target antigen on tumor cell | Not MHC-specific, so can be used regardless of HLA subtype High specificity for target antigen Targets cell surface antigens |

Fewer potential tumor targets compared to IMMTac platform: Does not target intracellular tumor antigens |

|

[66] |

| Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor | Nivolumab Ipilimumab Pembrolizumab |

Monoclonal antibody that targets PD-1, PD-L1, or CTLA-4 in order to block T cell inhibitory interactions and allow for anti-tumor T cell activity | Broad spectrum of activity with indications across multiple tumor types, mainly solid tumors Durable responses observed |

Causes indiscriminate T cell activation that can lead to immune-related organ toxicities Anti-tumor effect relies on tumor infiltration of T-cells |

|

[67] |

| Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T Cell Therapy | Abecma (idecabtagene vicleucel) Breyanzi (lisocabtagen e maraleucel) Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) Tecartus (brexucabtagene autoleucel) Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) |

Autologous T-cells undergo ex vivo genetic engineering to express a chimeric antigen receptor that includes an extracellular tumor-targeted antibody fragment and intracellular T-cell activating domains. Engineered cells are infused and target tumor cells. | Growing application across hematologic malignancies “Living drug” with both immediate and long-term anti-tumor activity |

Complex production process for ex vivo genetic modification and T cell expansion Requires prolonged inpatient monitoring after autologous T cell infusion High rate of adverse events, some life-threatening Little activity in solid tumors |

|

[68,69] |

6. REGULATORY AFFAIRS

On January 25, 2022, tebentafusp received FDA approval for treatment for HLA-A*02:01-positive adult patients with unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma and is now available for use in the US[55]. The European Commission approved tebentafusp on April 4, 2022 for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma. With this, tebentafusp became the first TCR therapy to be approved in the EU and has received market authorization in all EU member states[56]. As of the time of this publication, there has not been regulatory approval of tebentafusp in Australia, Asia, or Africa.

7. CONCLUSION

Uveal melanoma is a rare cancer with a high risk of metastasis and few effective systemic treatment options. Tebentafusp is a first-in-class ImmTAC; it is a bispecific gp100-HLA-A*02:01-directed T-cell receptor and CD3 T-cell engager that elicits a polyclonal T-cell response against uveal melanoma cells. Preclinical studies of IMCgp100 showed highly specific tumor antigen binding and suggested a wide therapeutic window. Early phase trials of tebentafusp demonstrated a dose-response relationship as well as feasibility and tolerability of an escalating dose regimen. Pharmacodynamic assays demonstrated an increase in serum cytokines after tebentafusp dosing, and evaluation of tumor biopsy samples while on treatment showed increased concentration of T-cells. A phase III trial compared tebentafusp to investigator choice single-agent therapy and found significant PFS and OS benefit. The pattern of clinical response was variable, as some patients with radiographic evidence of progression still had a survival benefit with tebentafusp. Tebentafusp is well-tolerated, with low rates of treatment discontinuation and mostly on-target side effects that can be grouped into dermatologic and cytokine-mediated events. These adverse events usually occur early on in the treatment course and can be effectively managed. The liver-related toxicities observed were thought to mostly be in the setting of disease progression. Based on the promising results of the phase III trial, tebentafusp became the first FDA-approved treatment for metastatic uveal melanoma.

8. EXPERT OPINION

Tebentafusp has changed the landscape of treatment for metastatic uveal melanoma and should be considered for all HLA-A*0201-positive patients. While there was a clear survival benefit with first-line tebentafusp over single agent ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, or dacarbazine, there have been no head-to-head comparisons between tebentafusp and dual checkpoint blockade, which has been commonly used over single agent therapy for this patient population. It is unlikely that another randomized trial will be performed. However, given the proven overall survival benefit and acceptable toxicity profile of tebentafusp that was demonstrated in a large, international, randomized clinical trial, it should be the preferred agent for metastatic disease in most HLA-A*0201 positive patients.

In subgroup analyses of overall survival in the phase III trial, the benefit of tebentafusp was less clear when compared to ipilimumab alone and when looking at patients with ECOG 1 or higher tumor burden (M1b or M1c disease) [53]. Although the hazard ratio for overall survival suggested less benefit for tebentafusp when compared to the ipilimumab subgroup (HR 0.89, CI 0.38-2.31), patients who received ipilimumab (n=40) made up only a minority (15%) of the comparator group, which impairs the reliability of this subgroup comparison. Given the disappointing historical outcomes seen with single-agent checkpoint inhibition, including a phase II trial of ipilimumab in which 1-year OS was 22% and median OS was 6.8 months [57], we believe that the available data collectively support a benefit of tebentafusp over single-agent ipilimumab.

The hazard ratio for overall survival in the subgroup of patients with ECOG 1 also suggested less benefit with tebentafusp (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.39-1.36). Although tebentafusp was well-tolerated, this supports performance status as a general prognostic marker and may also reflect the difficulty of effectively administering a weekly systemic treatment in patients with worse performance status. Subgroup analyses are by no means conclusive, and while we would continue to offer tebentafusp to patients with ECOG 1, performance status should be a consideration in practice when discussing an individual patient’s’ candidacy for tebentafusp.

The subgroup analysis of patients with larger metastatic lesions (AJCC M1b or M1c disease) compared to smaller metastatic lesions (AJCC M1a disease) suggests that tebentafusp may not be as beneficial for patients with high tumor burden and that patients with early metastatic disease may derive the most survival benefit. Furthermore, since ORR was low at 9% in the phase III trial and prior early-phase data showed a median time to response of 7.4 months [44], tebentafusp may not be the best upfront agent for patients with rapidly progressive disease. These data highlight that for some patients who do not have the time to wait for a response on tebentafusp, other therapies are needed. Liver-directed therapies such as chemoembolization have shown benefit in some patients with bulky liver disease [58-60], but the benefit of sequencing liver-directed therapies with tebentafusp has not yet been studied.

Another major limitation of tebentafusp is its exclusive binding in the context of HLA-A*0201, a subtype that is expressed in approximately 50% of Caucasians [61,62]. This restriction highlights an unmet therapeutic need among patients with other HLA subtypes, as there are no FDA-approved treatments to date that apply specifically to this population. IMMTacs targeting gp100 in the context of other relatively common HLA subtypes such as HLA-A*0101 and HLA-A*0301[62,63] would be of utility.

Several questions remain unanswered. For instance, the optimal duration of treatment on tebentafusp is unknown. The median duration of treatment in the phase I trial was 6-7.5 cycles[44] and in the phase II trial was 5.5 months, with 17% of patients remaining on treatment at the time of data cutoff[51]. In all trials, toxicities were generally mild, predictable, and easily managed. Rates of drug discontinuation from toxicity were low, and most adverse events took place early in the treatment course. Until there are further data to suggest otherwise, it may be a reasonable approach to continue tebentafusp until confirmed radiologic progression, as is done with other immunotherapies.

As with other immunotherapies, the optimal method to evaluate treatment response on tebentafusp is unclear. In both the early phase and phase III trials, there was a discordance between survival benefit and radiographic response using RECIST 1.1 criteria, highlighting the shortcomings of traditional measures of response as well as the need for other clinical and laboratory markers of anti-tumor activity. Although development of rash within one week correlated with improved survival in the phase III trial, it was not a significant independent predictor of survival in a multivariable analysis[53]. In phase I trials, below-median increase in IL-10 was associated with greater tumor shrinkage[44] and induction of serum CXCL10 and CXCL11 were associated improved survival[46]. Incidence of CRS after the first dose of tebentafusp also appeared to be associated with greater reduction in tumor size in the first-in-man trial[46,64]. Similar data have not yet been reported from the phase III trial. Reduction in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a promising surrogate for clinical benefit. In the phase II trial, baseline ctDNA level was associated with tumor burden, and reduction of ctDNA with tebentafusp by week 9 of treatment was associated with improved OS even among patients who had radiographic evidence of disease progression[51,52]. Expanded ctDNA testing will be necessary to better characterize its role as an indicator of treatment benefit.

Objectives of ongoing and future trials include identifying the optimal sequence of treatment between tebentafusp and checkpoint blockade, as well as the benefit of combining the two modalities. NCT02535078 is an ongoing phase 1b/2 study of combination tebentafusp with durvalumab and/or tremelimumab in metastatic cutaneous melanoma that is refractory to prior PD-1 inhibitors. Within uveal melanoma, phase I data showed that tebentafusp led to an increase in tumor PD-L1 expression[46], suggesting a potential benefit of administering immunotherapy after tebentafusp. Thirty-five percent of patients who received tebentafusp in the phase III trial subsequently received a PD-1 inhibitor[53]; subgroup analysis of patients by subsequent systemic therapy received may be informative.

Six percent of patients in the phase III tebentafusp arm underwent subsequent liver-directed local therapy. While regional therapies have shown benefit in carefully selected patients with oligometastatic liver disease, prospective data is largely limited to single-institution trials. It is still unclear whether they will have an increasing role as concurrent or subsequent therapies for patients treated with tebentafusp, but as discussed above, they may provide benefit as upfront treatment prior to tebentafusp for patients with bulky disease. The safety and efficacy of tebentafusp in combination or in sequence with liver-directed therapies is an important area of future investigation. Given the survival benefit achieved with tebentafusp in advanced disease as well as the association of benefit with lower overall disease burden, the evaluation of tebentafusp in the adjuvant setting after definitive therapy of primary disease is also of high priority.

Finally, in addition to gp100, other therapeutic targets in metastatic uveal melanoma have emerged and are being studied. PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) is highly expressed in Class 1 uveal melanomas and is an independent biomarker for increased metastatic risk[65]. Immunocore recently developed IMC-F106C, an ImmTAC with a T-cell receptor that targets PRAME, which is being studied in an ongoing Phase 1 and 2 study for HLA-A*0201-positive patients with PRAME-positive tumors.

While there are some limitations to its use, tebentafusp is an exciting new drug for metastatic uveal melanoma. The unsettled questions that remain, including proper disease response monitoring and benefit in other treatment settings, should be subjects of future investigation.

Article highlights.

Uveal melanoma is a rare disease with effective therapies for local disease but with a high risk of metastasis that is influenced by disease stage, tumor cytogenetics, and tumor gene expression.

There are few treatment options for metastatic uveal melanoma, as chemotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and targeted therapies have had disappointing results.

Tebentafusp is a first-in-class immune-mobilizing monoclonal T cell receptor against cancer (ImmTAC) that has a high binding affinity for the melanoma-associated antigen gp100 presented by HLA-A*0201 and relatively low binding affinity for CD3.

In preclinical studies, tebentafusp was shown to have high tumor antigen specificity and a wide therapeutic window.

In phase I and II trials, treatment with tebentafusp using a dose escalation regimen was feasible with an acceptable toxicity profile and showed activity in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma.

In a randomized phase III trial, first-line tebentafusp showed superior PFS and OS compared to single-agent chemotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitor.

In 2022, tebentafusp became the first FDA- and EMA- approved agent for metastatic uveal melanoma.

In most cases, tebentafusp should be the preferred front-line agent for the treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma. However, it is limited to patients with HLA-A2*0201 positivity and may not be the preferred upfront agent in patients with rapidly progressing disease or high tumor burden.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

RD Carvajal has received consultancy fees from; Alkermes, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Castle Biosciences, Eisai, Ideaya, Immunocore, InxMed, Iovance, Merck, Novartis, Oncosec, Pierre Fabre, PureTech Health, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sorrento Therapeutics, Trisalus. RD Carvajal has served omn the clinical and scientific advisory boards of; Aura Biosciences, Chimeron, Rgenix and has received research funding to Columbia University from; Amgen, Astellis, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corvus, Ideaya, Immunocore, Iovance, Merck, Mirati, Novartis, Pfizer, Plexxikon, Regeneron and Roche/Genentech.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (*) or of considerable interest (**) to readers.

- [1].Singh AD, Turell ME, Topham AK. Uveal Melanoma: Trends in Incidence, Treatment, and Survival. Ophthalmology [Internet]. 2011;118:1881–1885. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016164201100073X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jager MJ, Shields CL, Cebulla CM, et al. Uveal melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim [Internet]. 2020;6. Available from: http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/uveal-melanoma-primer/docview/2620846017/se-2?accountid=10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Damato B, Eleuteri A, Fisher AC, et al. Artificial Neural Networks Estimating Survival Probability after Treatment of Choroidal Melanoma. Ophthalmology [Internet]. 2008;115:1598–1607. Available from: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cunha Rola A, Taktak A, Eleuteri A, et al. Multicenter External Validation of the Liverpool Uveal Melanoma Prognosticator Online: An OOG Collaborative Study. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Amin M, Edge S, Greene F. AJCC Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [6].International Validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s 7th Edition Classification of Uveal Melanoma. JAMA Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2015;133:376–383. Available from: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dogrusöz M, Bagger M, van Duinen SG, et al. The Prognostic Value of AJCC Staging in Uveal Melanoma Is Enhanced by Adding Chromosome 3 and 8q Status. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci [Internet]. 2017;58:833–842. Available from: 10.1167/iovs.16-20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Robertson AG, Shih J, Yau C, et al. Integrative Analysis Identifies Four Molecular and Clinical Subsets in Uveal Melanoma. Cancer Cell [Internet]. 2017;32:204–220.e15. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1535610817302957. **Comprehensive molecular analysis of uveal melanoma

- [9].Jager MJ, Brouwer NJ, Esmaeli B. The Cancer Genome Atlas Project: An Integrated Molecular View of Uveal Melanoma. Ophthalmology [Internet]. 2018;125:1139–1142. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0161642018305013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vichitvejpaisal P, Dalvin LA, Mazloumi M, et al. Genetic Analysis of Uveal Melanoma in 658 Patients Using the Cancer Genome Atlas Classification of Uveal Melanoma as A, B, C, and D. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:1445–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Harbour JW. A Prognostic Test to Predict the Risk of Metastasis in Uveal Melanoma Based on a 15-Gene Expression Profile BT - Molecular Diagnostics for Melanoma: Methods and Protocols. In: Thurin M, Marincola FM, editors. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2014. p. 427–440. Available from: 10.1007/978-1-62703-727-3_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kath R, Hayungs J, Bornfeld N, et al. Prognosis and treatment of disseminated uveal melanoma. Cancer. 1993;72:2219–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lane AM, Kim IK, Gragoudas ES. Survival Rates in Patients After Treatment for Metastasis From Uveal Melanoma. JAMA Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2018;136:981–986. Available from: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rietschel P, Panageas KS, Hanlon C, et al. Variates of Survival in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2005;23:8076–8080. Available from: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Rantala ES, Hernberg M, Kivelä TT. Overall survival after treatment for metastatic uveal melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Melanoma Res [Internet]. 2019;29. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/melanomaresearch/Fulltext/2019/12000/Overall_survival_after_treatment_for_metastatic.1.aspx. *Large meta-analysis of outcomes of metastatic uveal melanoma

- [16]. Khoja L, Atenafu EG, Suciu S, et al. Meta-analysis in metastatic uveal melanoma to determine progression free and overall survival benchmarks: an international rare cancers initiative (IRCI) ocular melanoma study. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1370–1380. *Large meta-analysis of outcomes of metastatic uveal melanoma

- [17].Klingenstein A, Haug AR, Zech CJ, et al. Radioembolization as locoregional therapy of hepatic metastases in uveal melanoma patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gonsalves CF, Eschelman DJ, Adamo RD, et al. A Prospective Phase II Trial of Radioembolization for Treatment of Uveal Melanoma Hepatic Metastasis. Radiology. 2019;293:223–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Leyvraz S, Piperno-Neumann S, Suciu S, et al. Hepatic intra-arterial versus intravenous fotemustine in patients with liver metastases from uveal melanoma (EORTC 18021): a multicentric randomized trial. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:742–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hughes MS, Zager J, Faries M, et al. Results of a Randomized Controlled Multicenter Phase III Trial of Percutaneous Hepatic Perfusion Compared with Best Available Care for Patients with Melanoma Liver Metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1309–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Agarwala SS, Eggermont AMM, O’Day S, et al. Metastatic melanoma to the liver: a contemporary and comprehensive review of surgical, systemic, and regional therapeutic options. Cancer. 2014;120:781–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mariani P, Piperno-Neumann S, Servois V, et al. Surgical management of liver metastases from uveal melanoma: 16 years’ experience at the Institut Curie. Eur J Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2009;35:1192–1197. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S074879830900078X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zager JS, Orloff MM, Ferrucci PF, et al. FOCUS phase 3 trial results: Percutaneous hepatic perfusion (PHP) with melphalan for patients with ocular melanoma liver metastases (PHP-OCM-301/301A). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bagge RO, Nelson A, Shafazand A, et al. Isolated hepatic perfusion as a treatment for uveal melanoma liver metastases, first results from a phase III randomized controlled multicenter trial (the SCANDIUM trial). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Carvajal RD, Schwartz GK, Tezel T, et al. Metastatic disease from uveal melanoma: treatment options and future prospects. Br J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2017;101:38 LP – 44. Available from: http://bjo.bmj.com/content/101/1/38.abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zimmer L, Vaubel J, Mohr P, et al. Phase II DeCOG-Study of Ipilimumab in Pretreated and Treatment-Naïve Patients with Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015;10:e0118564. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Joshua AM, Monzon JG, Mihalcioiu C, et al. A phase 2 study of tremelimumab in patients with advanced uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res [Internet]. 2015;25. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/melanomaresearch/Fulltext/2015/08000/A_phase_2_study_of_tremelimumab_in_patients_with.11.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Algazi AP, Tsai KK, Shoushtari AN, et al. Clinical outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies. Cancer [Internet]. 2016;122:3344–3353. Available from: 10.1002/cncr.30258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Pelster MS, Gruschkus SK, Bassett R, et al. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma: Results From a Single-Arm Phase II Study. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2020;39:599–607. Available from: 10.1200/JCO.20.00605. *Phase II trial of dual checkpoint inhibitor therapy in metastatic uveal melanoma

- [30]. Piulats JM, Espinosa E, de la Cruz Merino L, et al. Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab for Treatment-Naïve Metastatic Uveal Melanoma: An Open-Label, Multicenter, Phase II Trial by the Spanish Multidisciplinary Melanoma Group (GEM-1402). J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2021;39:586–598. Available from: 10.1200/JCO.20.00550. *Phase II trial of dual checkpoint inhibitor therapy in metastatic uveal melanoma

- [31].Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Five-Year Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1535–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Najjar YG, Navrazhina K, Ding F, et al. Ipilimumab plus nivolumab for patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: a multicenter, retrospective study. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor Mutational Burden and Response Rate to PD-1 Inhibition. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2017;377:2500–2501. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29262275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Javed A, Arguello D, Johnston C, et al. Disparity in PD-L1 expression between metastatic uveal and cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2016;34:9541. Available from: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.9541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Javed A, Arguello D, Johnston C, et al. PD-L1 expression in tumor metastasis is different between uveal melanoma and cutaneous melanoma. Immunotherapy [Internet]. 2017;9:1323–1330. Available from: 10.2217/imt-2017-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Quevedo JF, et al. Effect of selumetinib vs chemotherapy on progression-free survival in uveal melanoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2397–2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Carvajal RD, Piperno-Neumann S, Kapiteijn E, et al. Selumetinib in Combination With Dacarbazine in Patients With Metastatic Uveal Melanoma: A Phase III, Multicenter, Randomized Trial (SUMIT). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1232–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nathan P, Needham A, Corrie PG, et al. LBA73 - SELPAC: A 3 arm randomised phase II study of the MEK inhibitor selumetinib alone or in combination with paclitaxel (PT) in metastatic uveal melanoma (UM). Ann Oncol [Internet]. 2019;30:v908–v910. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0923753419604308. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Oates J, Hassan NJ, Jakobsen BK. ImmTACs for targeted cancer therapy: Why, what, how, and which. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liddy N, Bossi G, Adams KJ, et al. Monoclonal TCR-redirected tumor cell killing. Nat Med. 2012;18:980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Boudousquie C, Bossi G, Hurst JM, et al. Polyfunctional response by ImmTAC (IMCgp100) redirected CD8(+) and CD4(+) T cells. Immunology. 2017;152:425–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].de Vries TJ, Trancikova D, Ruiter DJ, et al. High expression of immunotherapy candidate proteins gp100, MART-1, tyrosinase and TRP-1 in uveal melanoma. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1156–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Harper J, Adams KJ, Bossi G, et al. An approved in vitro approach to preclinical safety and efficacy evaluation of engineered T cell receptor anti-CD3 bispecific (ImmTAC) molecules. PLoS One [Internet]. 2018;13:e0205491. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Carvajal RD, Nathan P, Sacco JJ, et al. Phase I Study of Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Tebentafusp Using a Step-Up Dosing Regimen and Expansion in Patients With Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2022;JCO.21.01805. Available from: 10.1200/JCO.21.01805. **Phase I trial of tebentafusp that established a dose escalation regimen for metastatic uveal melanoma patients

- [45].FDA Approves KIMMTRAK for the Treatment of HLA-A*02:01-Positive Adult Patients with Unresectable or Metastatic Uveal Melanoma [Internet]. Off. Clin. Pharmacol Available from: https://accp1.org/Members/Publications_News/FDA_Bursts/ACCP1/5Publications_and_News/FDABurst2022/FDA-Approves-KIMMTRAK-Treatment-HLA-A0201-Positive-Adult-Patients.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Middleton MR, McAlpine C, Woodcock VK, et al. Tebentafusp, A TCR/Anti-CD3 Bispecific Fusion Protein Targeting gp100, Potently Activated Antitumor Immune Responses in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Clin cancer Res. 2020;26:5869–5878. **First-in man trial of tebentafusp for metastatic melanoma

- [47].Carvajal R, Sato T, Shoushtari A, et al. Safety, efficacy and biology of the gp100 TCR-based bispecific T cell redirector, IMCgp100 in advanced uveal melanoma in two Phase 1 trials VO - 5 RT - Conference Paper. J. Immunother. Cancer OP -. BioMed Central; [Google Scholar]

- [48].Middleton M, Corrie P, Sznol M, et al. Abstract CT106: A phase I/IIa study of IMCgp100: Partial and complete durable responses with a novel first-in-class immunotherapy for advanced melanoma. Cancer Res. 2015;75:CT106–CT106. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Middleton MR, Steven NM, Evans TJ, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and efficacy of IMCgp100, a first-in-class soluble TCR-antiCD3 bispecific t cell redirector with solid tumour activity: Results from the FIH study in melanoma. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2016;34:3016. Available from: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.3016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sato T, Nathan PD, Hernandez-Aya L, et al. Redirected T cell lysis in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma with gp100-directed TCR IMCgp100: Overall survival findings. J Clin Oncol [Internet]. 2018;36:9521. Available from: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.9521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Sacco J, Carvajal R, Butler M, et al. 64MO - A phase (ph) II, multi-center study of the safety and efficacy of tebentafusp (tebe) (IMCgp100) in patients (pts) with metastatic uveal melanoma (mUM). Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S1441–S1451. *Phase II trial of tebentafusp in metastatic uveal melanoma patients

- [52]. Shoushtari A, Collins L, Espinosa E, et al. Early reduction in ctDNA, regardless of best RECIST response, is associated with overall survival on tebentafusp in previously treated metastatic uveal melanoma patients. ESMO Congr. 2021; **Phase II trial of tebentafusp in metastatic uveal melanoma patients with ctDNA analysis

- [53]. Nathan P, Hassel JC, Rutkowski P, et al. Overall Survival Benefit with Tebentafusp in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1196–1206. **Randomized phase III trial of tebentafusp in metastatic uveal melanoma patients; findings led to FDA and EMA approval

- [54].Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].FDA approves tebentafusp-tebn for unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-tebentafusp-tebn-unresectable-or-metastatic-uveal-melanoma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].European Commission Approves KIMMTRAK® (tebentafusp) for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://ir.immunocore.com/node/7521/pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zimmer L, Vaubel J, Mohr P, et al. Phase II DeCOG-Study of Ipilimumab in Pretreated and Treatment-Naïve Patients with Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Perez-Gracia JL, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2022 Apr 7];10:e0118564. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Valpione S, Aliberti C, Parrozzani R, et al. A retrospective analysis of 141 patients with liver metastases from uveal melanoma: a two-cohort study comparing transarterial chemoembolization with CPT-11 charged microbeads and historical treatments. Melanoma Res. 2015;25:164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gonsalves CF, Eschelman DJ, Thornburg B, et al. Uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver: Chemoembolization with 1,3-bis-(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Patel K, Sullivan K, Berd D, et al. Chemoembolization of the hepatic artery with BCNU for metastatic uveal melanoma: results of a phase II study. Melanoma Res. 2005;15:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ellis JM, Henson V, Slack R, et al. Frequencies of HLA-A2 alleles in five U.S. population groups: Predominance of A*02011 and identification of FILA-A*0231. Hum Immunol [Internet]. 2000;61:334–340. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S019888599900155X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Gragert L, Madbouly A, Freeman J, et al. Six-locus high resolution HLA haplotype frequencies derived from mixed-resolution DNA typing for the entire US donor registry. Hum Immunol [Internet]. 2013;74:1313–1320. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0198885913001821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Maiers M, Gragert L, Klitz W. High-resolution HLA alleles and haplotypes in the United States population. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].New Data Uncover Deeper Insight into Tebentafusp (IMCgp100) Clinical Activity in Patients with Advanced Melanoma, Including Uveal [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://ir.immunocore.com/news-releases/news-release-details/new-data-uncover-deeper-insight-tebentafusp-imcgp100-clinical. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Field MG, Decatur CL, Kurtenbach S, et al. PRAME as an Independent Biomarker for Metastasis in Uveal Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res [Internet]. 2016;22:1234–1242. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26933176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Lowe KL, Cole D, Kenefeck R, et al. Novel TCR-based biologies: mobilising T cells to warm ‘cold’ tumours. Cancer Treat Rev [Internet]. 2019;77:35–43. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305737219300799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2375–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Rivière I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:388–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN. Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: recognition and management. Blood [Internet]. 2016;127:3321–3330. Available from: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-703751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]