Objectives

Noninvasive, affordable, and reliable mapping of brain glucose metabolism is of critical interest for clinical research and routine application as metabolic impairment is linked to numerous pathologies, for example, cancer, dementia, and depression. A novel approach to map glucose metabolism noninvasively in the human brain has been presented recently on ultrahigh-field magnetic resonance (MR) scanners (≥7T) using indirect detection of deuterium-labeled glucose and downstream metabolites such as glutamate, glutamine, and lactate. The aim of this study was to demonstrate the feasibility to noninvasively detect deuterium-labeled downstream glucose metabolites indirectly in the human brain via 3-dimensional (3D) proton (1H) MR spectroscopic imaging on a clinical 3T MR scanner without additional hardware.

Materials and Methods

This prospective, institutional review board–approved study was performed in 7 healthy volunteers (mean age, 31 ± 4 years, 5 men/2 women) after obtaining written informed consent. After overnight fasting and oral deuterium-labeled glucose administration, 3D metabolic maps were acquired every ∼4 minutes with ∼0.24 mL isotropic spatial resolution using real-time motion-, shim-, and frequency-corrected echo-less 3D 1H-MR spectroscopic Imaging on a clinical routine 3T MR system. To test the interscanner reproducibility of the method, subjects were remeasured on a similar 3T MR system. Time courses were analyzed using linear regression and nonparametric statistical tests. Deuterium-labeled glucose and downstream metabolites were detected indirectly via their respective signal decrease in dynamic 1H MR spectra due to exchange of labeled and unlabeled molecules.

Results

Sixty-five minutes after deuterium-labeled glucose administration, glutamate + glutamine (Glx) signal intensities decreased in gray/white matter (GM/WM) by −1.63 ± 0.3/−1.0 ± 0.3 mM (−13% ± 3%, P = 0.02/−11% ± 3%, P = 0.02), respectively. A moderate to strong negative correlation between Glx and time was observed in GM/WM (r = −0.64, P < 0.001/r = −0.54, P < 0.001), with 60% ± 18% (P = 0.02) steeper slopes in GM versus WM, indicating faster metabolic activity. Other nonlabeled metabolites showed no significant changes. Excellent intrasubject repeatability was observed across scanners for static results at the beginning of the measurement (coefficient of variation 4% ± 4%), whereas differences were observed in individual Glx dynamics, presumably owing to physiological variation of glucose metabolism.

Conclusion

Our approach translates deuterium metabolic imaging to widely available clinical routine MR scanners without specialized hardware, offering a safe, affordable, and versatile (other substances than glucose can be labeled) approach for noninvasive imaging of glucose and neurotransmitter metabolism in the human brain.

Key Words: magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging, deuterium labeling, quantitative exchange label turnover, downstream glucose metabolism, neurotransmitter, brain, glutamate, glutamine, deuterium metabolic imaging

Impairment of glucose (Glc) metabolism in the human brain, that is, a shift from aerobic Glc utilization toward anaerobic pathways (Warburg effect), has been linked to several pathologic conditions observed in, for example, ischemia and tumors.1 Anaerobic glycolysis plays an important role during early stages of dementia2 and neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and depression.3

[18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) is the current gold standard in clinical routine for assessing tissue-specific Glc uptake, but it requires invasive administration of unstable radioactive tracers and does not provide information on the dynamics of Glc downstream metabolites, for example, oxidative neurotransmitter synthesis of glutamate (Glu) and glutamine (Gln), or anaerobic lactate production, in, for example, tumors due to Glc trapping of [18F]FDG. Therefore, a fully noninvasive approach to reliably map the brain Glc metabolism is of critical interest for clinical research and routine application.4

Deuterium metabolic imaging (DMI)5,6 and quantitative exchanged label turnover (QELT)7–10 are novel magnetic resonance (MR) techniques to noninvasively image Glc metabolism in animals and the human brain using deuterium-labeled Glc as tracer, which are able to separate healthy oxidative from pathologic anaerobic pathways, by simultaneously detecting the respective metabolic products Glu + Gln and lactate.4 Deuterium metabolic imaging detects deuterium enrichment in the brain tissue directly via 2H-MR spectroscopy (MRS), whereas, indirectly, QELT detects a decrease in signal intensities in conventional 1H-MR spectra due to deuterium-to-proton exchange of labeled and unlabeled molecules, comparably as already performed using 13C-labeled Glc.11 Recently, DMI has been translated to clinical field strength of 3T12 with a nominal isotropic resolution of 33 mL and an acquisition time of 10 minutes for each 3-dimensional (3D) dataset. Quantitative exchanged label turnover features higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spatial resolution (0.12 mL) with shorter acquisition times (~3 minutes7) compared with DMI, while additionally detecting nonlabeled metabolites, but so far has been applied in humans only at ultrahigh field strength of ≥7T.7,8

Translating this QELT method to widely available clinical MR scanners (≤3T) without the need for additional expensive hardware would offer radiologists immediate access to a fully noninvasive and affordable approach to map Glc downstream metabolism.

This study demonstrates the feasibility to noninvasively image Glc downstream metabolism in the human brain on a clinical 3T MR scanner using the QELT approach with time-resolved 3D proton (1H) MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) and deuterium-labeled Glc.

METHODS

Participants

This study was approved by the ethic commission of the Medical University of Vienna and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Seven healthy participants (mean age, 31 ± 4 years; 5 men; body mass index, 22 ± 1 kg/m2) were recruited consecutively at the Department of Biomedical Imaging and Image-Guided Therapy of the Medical University Vienna with the following inclusion criteria: no contraindication to 3T MR imaging (MRI), history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, claustrophobia, metabolic disorders, or metal implants.

Study Protocol

The study included an MRI protocol and blood Glc sampling. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed in the morning after overnight fasting and immediately after oral tracer administration using deuterium-labeled Glc ([6,6′]-2H-Glc; 0.8 g/kg body weight in 200 mL water). Six subjects were remeasured within 6 to 9 months to assess the repeatability of the method. All subjects consumed the labeled Glc under 1 minute shortly before being moved into the scanner. Capillary puncture blood sampling from the toe (ie, most accessible sampling site in the MR scanner) was performed 6 times over the course of ~90 minutes (we aimed for standardized time points of 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, and 100 minutes) using 2 standard strip glucometers (Verio, OneTouch) for cross-checking.

MRI Protocol

All measurements were conducted on clinical routine 3T MR systems (Prisma-FIT and Prisma for test and retest measurements, respectively) using a 64-channel receive head coil (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen). Preparation scans included an automated alignment localizer followed by echo planar imaging reference scans to set up the volumetric navigator sequence used for real-time motion correction.13 A previously developed 3D echoless (free induction decay [FID]) MRSI sequence with automatic interleaved real-time motion-, shim-, and frequency drift-correction and fast concentric ring trajectory readout14,15 was used to acquire 14 consecutive 3D datasets over the course of ~60 minutes: 0.8 milliseconds acquisition delay, 950 milliseconds repetition time, 0.24 mL isotropic nominal voxel volume (matrix size, 32 × 32 × 21; field of view, 200 × 200 × 130 mm3; volume of interest, 200 × 200 × 55 mm3 centered around the posterior cingulate region), and 4 minutes 14 seconds acquisition time per repetition (for details, see table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/RLI/A79816). Water suppression was performed using conventional water suppression Enhanced through T1 effects scheme,17 whereas unsuppressed water reference signals (20 FID points) were acquired during each TR for determination of coil sensitivities.

After the MRSI scan, a 3D T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo readout scan was performed: 1800 milliseconds repetition time, 2.27 milliseconds echo time, 900 milliseconds inversion time, 1 mm3 isotropic nominal voxel volume (field of view, 250 × 250 × 350 mm; matrix size, 256 × 256 × 208), 3-fold parallel acquisition acceleration (Generalized Autocalibrating Partial Parallel Aquisition), and 2 minutes 38 seconds acquisition time.

Data Reconstruction

An in-house developed software pipeline (MATLAB R2021, Python 3.10) was used for automatic data processing, including k-space in-plane convolutional gridding,18 noise decorrelation, channel-wise lipid decontamination,19 coil combination,20 and spectral fitting (4.2–1.8 ppm) using LCModel (version 6.3). Voxel-wise spectral fitting was performed for all 3D datasets and time points, without the use of spectral subtraction. Quantification results of voxels that did not fulfill the quality control criteria, that is, full width at half maximum <0.1 ppm, signal-to-noise ratio >15, and Cramer-Rao Lower Bounds (CRLBs) <20%, were excluded from the analysis.

Metabolite Quantification

A modified basis set was used featuring 17 typical metabolites (ie, creatine, glycerophosphocholine, glutathione, myo-inositol, N-acetylaspartate, N-acetylaspartylglutamate, phosphocholine, phosphocreatine, taurine, aspartate, γ-aminobutyric acid, Glcα, Glcβ Glu, Gln, and lactate) of neurochemical profile (including measured macromolecular contributions),21 but this work focuses on few selected metabolites of interest: Glu + Gln (Glx), total creatine (tCr), and total N-acetylaspartate (tNAA). During metabolic utilization of deuterium-labeled Glc ([6,6′]-2H-Glc), downstream metabolites incorporate deuterium at specific carbon positions. In case of oxidatively synthesized Glu and Gln, deuterium labeling occurs only at the fourth carbon position (Glu4: 2.34 ppm, Gln4: 2.44 ppm), eventually leading to a signal intensity decrease of the respective resonances, whereas resonances associated with protons at the second and third position (Glu2: 3.75 ppm, Glu3: 2.10 ppm, Gln2: 3.77 ppm, and Gln3: 2.13 ppm) remain stable.

Therefore, resonances representing Glu and Gln in the basis set were separated into Glu4 and Glu2 + 3 and Gln4 and Gln2 + 3, respectively, and then summed to Glx4 and Glx2 + 3, representing labeled and unlabeled resonances, respectively. Separation was performed by simulating Glu and Gln with fully deuterated Glu4 and Gln4 (equals Glu2 + 3 and Gln2 + 3: both protons at the fourth carbon position are replaced with deuterons) and subtracting it from regular Glu and Gln to obtain Glu4 and Gln4. Therefore, a linear combination equals regular Glu and Gln molecules taking J-coupling effects into account. Similarly, only the sixth carbon position of Glc is labeled, and therefore, Glc6 (labeled) and Glc1–5 (unlabeled) components were introduced. Labeling of Glc on other carbon positions than [6,6] is lost during metabolic utilization and is not detectable. Metabolic maps for Glx4 were calculated as a voxel wise ratio reference to tCr. Metabolite concentration estimates of regionally averaged Glx4 for gray (GM) and white (WM) matter are given in absolute units (mM), referenced to assumed concentrations of tCr (GM: 7.5 mM, WM: 5.7 mM) and relaxation times from literature (T1: tCrGM/WM = 1.46/1.24 seconds, GlxGM/WM = 1.27/1.24 seconds, T2: tCrGM/WM = 201 milliseconds/198 milliseconds, GlxGM/WM = 134 milliseconds/148 milliseconds).22–24 Glx2 + 3, tCr, and tNAA concentrations are given in arbitrary units.

Time Course Analysis

Three-dimensional metabolic maps were created for all 14 time points representing the metabolic dynamics over ~60 minutes with a high time resolution of ~4 minutes. Maps were coregistered to anatomical T1-weighted images. Regional segmentation for GM and WM was automatically performed using the Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Automated Segmentation Tool algorithm25 on T1-weighted 3D images and down-sampled to 32 × 32 using MINC tools (MINC tools, v2.0, McConnell Brain Imaging Center, Montreal, QC, Canada). Partial volume effects were minimized using a threshold of 80% for GM and WM voxels, respectively.

Temporal metabolite signal evolution was investigated voxel-wise and over the whole GM or WM in each participant, given as mean ± standard deviation. To estimate temporal stability of metabolite concentration fits, coefficients of variation were calculated over the entire MRSI scan (60 minutes and 14 time points) for stable nonlabeled metabolites (Glx2 + 3, tCr, tNAA).

Statistical Analysis

Linear regression analysis was performed between time and quantified metabolite signals, for example, deuterium-labeled resonances (Glx4). Differences between the first and last time points and between GM and WM groups were evaluated using Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Mann-Whitney U test between segmented GM and WM voxels. The statistical significance threshold was P < 0.05. Linear fitting and statistical tests were performed using Python 3.10 (www.python.org, packages: scipy.stats).

RESULTS

Study Protocol

All preparation scans were completed 6 ± 2 minutes after tracer administration. The subsequent MRSI sequence acquired 3D datasets consecutively every ~4 minutes without interruption or operator interaction. Capillary blood sampling and analysis were performed in 5 participants.

Time Course Analysis

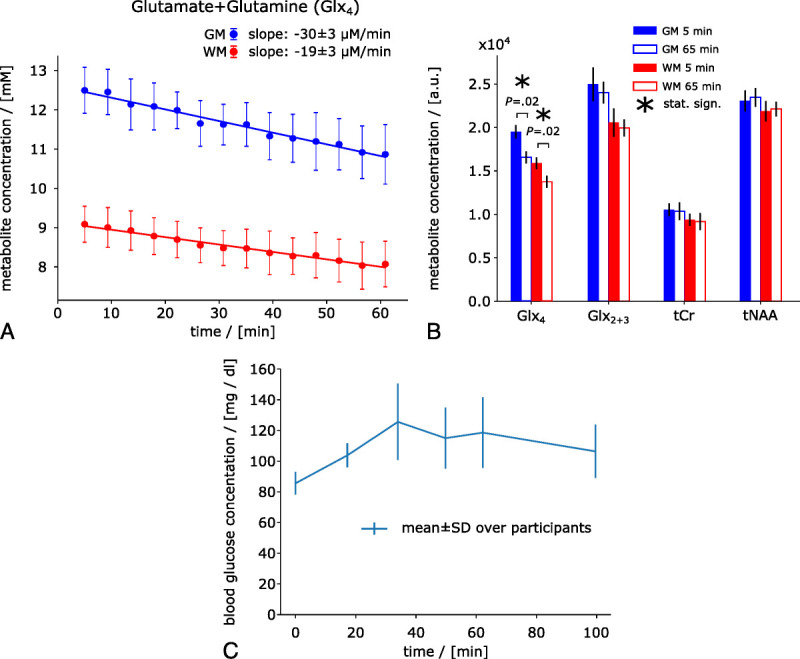

Moderate to strong negative correlation with time was observed for Glx4 in GM (r = −0.64, P < 0.001) and WM (r = −0.54, P < 0.001), with 60% ± 18% steeper slopes in GM compared with WM (P = 0.02), representing faster signal decay (Fig. 1a). Individual results of linear regression analysis are listed for test and retest measurements (see Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Time courses of deuterium-labeled Glx (Glx4) signal concentrations in mM (from whole GM and WM averaged over all participants). A decrease in Glx4 over time can be observed in both GM and WM. The decrease in Glx4 was 60% ± 18% faster in GM compared with WM (A). First and last measurement (first at ~5 minutes, last at ~65 minutes) of deuterium-labeled (Glx4) and unlabeled (Glx2 + 3, tCr, tNAA) resonances shown as regional means over whole GM and WM and over all participants (B). Averaged time course of blood Glc concentration over all participants increasing from 86 ± 7 mg/dL to 126 ± 25 mg/dL at 34 minutes (averaged sampling time points) after tracer administration before gradually decreasing toward baseline (C).

TABLE 1.

Initial Concentrations and Linear Regression Results per Participant and Region for Test and Retest Measurement Bouts

| Metabolite | Initial Concentrations, mM | Slopes, μM/min | Correlation Coefficient, r | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glx4 | ||||

| Test | ||||

| Participant 1 | 11.5/8.6 | −31.6/−23.3 | −0.99/−0.98 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 2 | 13.3/9.6 | −31.2/−20.4 | −0.96/−0.97 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 3 | 12.8/9.6 | −24.0/−15.1 | −0.89/−0.86 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 4 | 13.0/9.5 | −27.7/−17.3 | −0.94/−0.87 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 5 | 11.9/8.4 | −30.8/−21.9 | −0.95/−0.95 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 6 | 12.3/8.9 | −35.2/−19.8 | −0.93/−0.96 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 7 | 12.7/9.0 | −27.0/−14.1 | −0.97/−0.92 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Retest | ||||

| Participant 1 | 11.2/8.2 | −13.5/−11.6 | −0.64/−0.72 | 0.014/0.003 |

| Participant 2 | 11.8/8.7 | −25.2/−14.9 | −0.93/−0.86 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 3 | 12.1/9.1 | −33.8/−26.8 | −0.88/−0.81 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 4 | 13.2/9.8 | −37.0/−27.8 | −0.96/−0.96 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 5 | 11.3/8.2 | −22.6/−14.5 | −0.87/−0.89 | <0.001/<0.001 |

| Participant 6 | – | – | – | – |

| Participant 7 | 12.5/8.9 | −20.2/−16.8 | −0.85/−0.97 | <0.001/<0.001 |

Data are from gray/white matter.

Glx indicates glutamate + glutamine.

Sixty-five minutes after tracer administration, Glx4 had decreased by −1.63 ± 0.3 mM (−13% ± 3%, P = 0.02) and −1.0 ± 0.3 mM (−11% ± 3%, P = 0.02) compared with the initial time point in GM and WM, respectively, whereas no changes were found for Glx2 + 3, tCr, or tNAA (GM/WM: Glx2 + 3, P = 0.08/0.16; tCr, P = 0.47/0.30; tNAA, P = 0.16/0.81) (Fig. 1b).

Blood Glc concentration increased from 86 ± 7 mg/dL at baseline to 126 ± 25 mg/dL (P = 0.068) at 34 minutes (averaged sample time points) after tracer administration, followed by a gradual decrease toward baseline (Fig. 1c).

Nonlabeled metabolite resonances, for example, Glx2 + 3, tCr, and tNAA, featured high temporal stability with coefficients of variation <2% (Glx2 + 3, 1.9% ± 0.6%; tCr, 1.5% ± 0.8%; and tNAA, 1.1% ± 1%).

Comparison between results from test and retest experiments including a Bland-Altman comparison for absolute Glx4 in mM is shown in Supplementary Digital Content, Figures 1 and 2, http://links.lww.com/RLI/A798 and http://links.lww.com/RLI/A798, respectively.

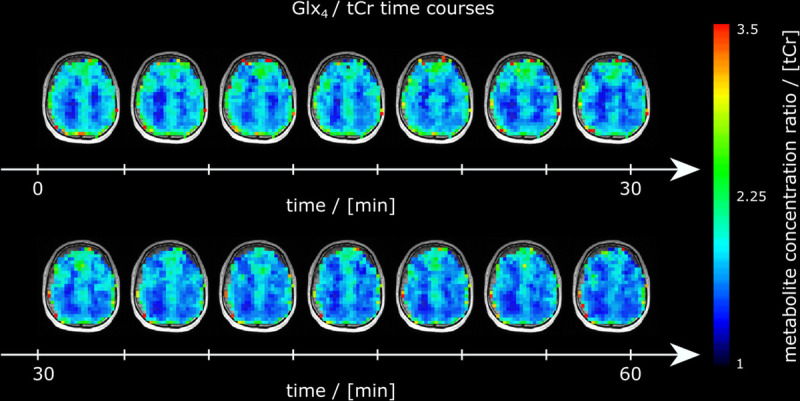

Representative axial Glx4/tCr ratio maps are shown for all time points from 1 representative subject (Fig. 2). A continuous signal intensity decrease over time due to deuterium labeling was visually discernable. Metabolic map time courses (Glx4/tCr ratio maps) from all participants are shown in Supplemental Digital Content Figure 3, http://links.lww.com/RLI/A798.

FIGURE 2.

Time courses of axial Glx ratio maps referenced to tCr (Glx4/tCr) maps from 1 representative subject over the entire measurement visualizing the image intensity decrease over time due to deuterium labeling.

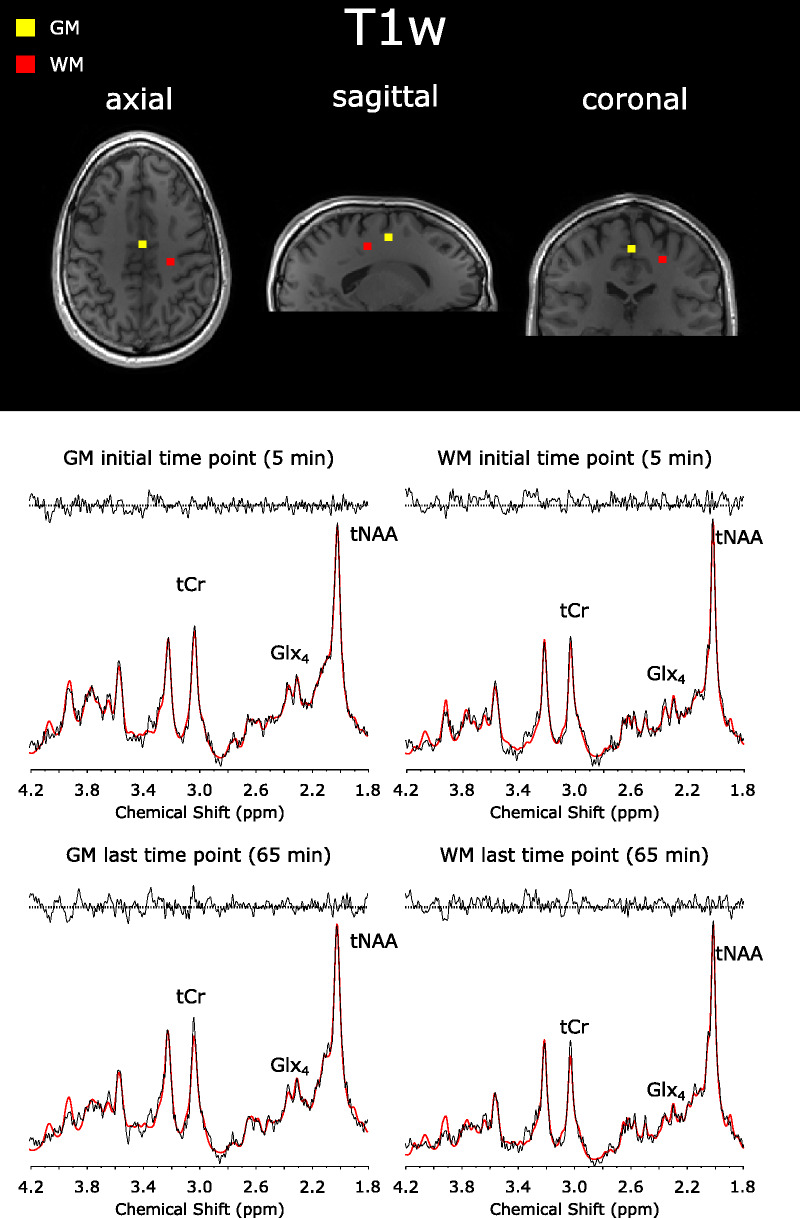

Sample spectra of single GM and WM voxels from the first and last time points of 1 representative subject are shown in Figure 3, with their respective metabolite concentrations and CRLBs (see Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

Sample spectra (black) and LCModel fit (red) from a single GM and WM voxel of 1 representative volunteer at the beginning (5 minutes) and the end (65 minutes) of the MRSI scan. Spectra were first-order corrected for illustration purposes. Relevant metabolites are total tCr, Glx, and tNAA. Spectral concentration fits of these particular voxels are shown in Supplemental Digital Content Table 1, http://links.lww.com/RLI/A798.

TABLE 2.

LCModel Spectral Fit Output of a Single Representative GM and WM Voxel for Selected Metabolites From the First (5 Minutes) and Last (60 Minutes) Time Points After d-Glucose Ingestion

| Metabolite | GM Voxel | WM Voxel | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration, a.u. (CRLB, %) | Concentration, a.u. (CRLB, %) | |||

| 5 Min | 65 Min | 5 Min | 65 Min | |

| tCr | 1.07E4 (4%) | 1.00E4 (5%) | 7.47E3 (5%) | 6.75E3 (4%) |

| tNAA | 2.25E4 (3%) | 2.25E4 (3%) | 1.90E4 (3%) | 2.03E4 (2%) |

| Glx4* | 2.10E4 (7%) | 1.53E4 (10%) | 1.09E4 (10%) | 9.00E3 (11%) |

| Glx23 | 2.68E4 (5%) | 2.76E4 (5%) | 1.36E4 (8%) | 1.44E4 (6%) |

| Glu4* | 1.44E4 (7%) | 1.06E4 (10%) | 7.77E3 (10%) | 6.21E3 (12%) |

| Glu23 | 1.83E4 (7%) | 1.82E4 (8%) | 8.51E3 (11%) | 6.60E3 (16%) |

| Gln4* | 6.55E3 (12%) | 4.63E3 (17%) | 3.11E3 (18%) | 2.80E3 (19%) |

| Gln23 | 8.46E3 (13%) | 9.36E3 (13%) | 5.11E3 (17%) | 7.76E3 (12%) |

| Cr | 7.13E3 (13%) | 5.84E3 (17%) | 5.58E3 (12%) | 4.00E3 (15%) |

| PCr | 3.60E3 (24%) | 4.19E3 (24%) | 1.89E3 (34%) | 2.75E3 (22%) |

| NAA | 2.12E4 (3%) | 2.21E4 (3%) | 1.69E4 (3%) | 1.68E4 (3%) |

| NAAG | 1.30E3 (30%) | 4.15E2(111%) | 2.17E3 (14%) | 3.54E3 (9%) |

Respective spectra and LCModel fits are shown in Figure 3. Data are for unlabeled metabolites unless otherwise indicated.

*Deuterium labeled.

GM indicates gray matter; WM, white matter; a.u., arbitrary units; tCr, total creatine; tNAA, total N-acetylaspartate; Glx, glutamate + glutamine; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; CRLB, Cramer-Rao lower bound; Cr, creatine; PCr, phosphocreatine; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; NAAG, N-acetylaspartylglutamic acid.

Voxel-wise linear fitting yielded moderate to strong (r < −0.5, P < 0.05) negative correlation between Glx4 signal intensity and time in 50% of GM and 44% of WM voxels from a 3D dataset of 1 representative participant (Supplementary Digital Content Fig. 4, http://links.lww.com/RLI/A798). Voxel-wise linear fitting was performed on data in arbitrary units to improve temporal stability. Slopes of the linear regression show a visible GM/WM contrast with 32% steeper slopes for Glx4 (P < 0.001) between GM and WM, representing a faster signal intensity decay, that is, higher metabolic activity.

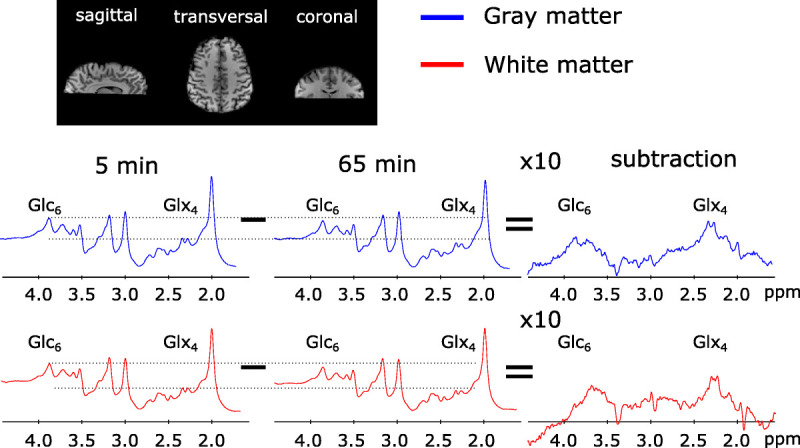

For illustration purposes, the subtraction spectra (first–last measurement) of averaged GM and WM voxels of 1 representative subject were calculated to visualize the signal drop of the Glx4 resonance 65 minutes after tracer administration as an increase of deuterium-labeled resonances only, similar to DMI (Fig. 4). Subtraction spectra showed Glx4 and Glc6 resonances. However, spectral fitting was performed voxel wise and without spectral subtraction.

FIGURE 4.

Averaged spectra over selected voxels in GM and WM 5 and 65 minutes after deuterium-labeled Glc administration visualizing a decrease in the Glx4 and Glc6 resonance, whereas other resonances were stable. Corresponding subtraction spectra showed an increase of the Glx4 and Glc6 resonance.

More than 90% of GM and WM voxels featured CRLBs <20%, whereas overall, more than 60% of GM and WM voxels fulfilled the entire standardized quality criteria (ie, full width at half maximum <0.1 ppm, signal-to-noise ratio >15, CRLBs <20%).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have targeted the need for a fully noninvasive clinically applicable technique to map the dynamics of Glc metabolism in the human brain. We demonstrated the feasibility of our MR technique to image oxidative downstream Glc metabolism almost over the entire human cerebrum, using orally administered deuterium labeled Glc on a clinical routine 3T MR system.

The ultrashort echo time of the 3D FID-MRSI method minimizes J-evolution for metabolites such as Glx and improves the SNR compared with spin-echo approaches. High SNR and integrated real-time motion correction15 provided a high temporal stability reflected by a coefficient of variation of lower than 2% over the course of 60 minutes (14 time points) for regional averages of nonlabeled metabolites, that is, Glx2 + 3, tCr, and tNAA. This allowed for a reliable detection of 10% to 20% changes in signal amplitude for labeled metabolites (Glx4) due to deuterium enrichment even for voxel-wise analysis. However, regional averaging over multiple voxels improved the robustness of the results.

Excellent intrasubject repeatability was observed across scanners for static results at the beginning of the measurement, representing the repeatability of the method itself, without the influence of physiological variation (intrasubject coefficient of variation, 4% ± 4%). The decrease in Glx4 over time due to deuterium enrichment featured higher intrasubject variation for individual data points, whereas on average it was comparable. This could be explained presumably by physiological variation in Glc metabolism, as repeated measurements were performed up to 9 months apart.

Other approaches, for example, spectral fitting of subtraction spectra between time points, were not feasible as the coefficient of variation on voxel-wise level is too high to reliably detect a signal decrease of a few percentage (per time point) under low SNR conditions and missing reference peaks.

A proof that the decrease in Glx4 is not an artifact or systematic error of the method and indeed reflects physiological incorporation of deuterium into downstream metabolites has been performed in a previous study by assessing the test-retest repeatability and control measurements using regular Glc (dextrose), using a similar MR sequence (without motion correction) at 7T.7 In addition, results were compared with DMI data acquired from the same cohort of subjects and on the same MR scanner. The absolute decrease of Glx4 by −1.63 ± 0.3 mM in GM and −1.0 ± 0.3 mM in WM 60 minutes after labeled Glc administration is in good agreement with recent DMI literature.5,26 Therefore, no control measurements using unlabeled Glc were performed in this study. The relative decrease of Glx4 in our study is in good agreement with QELT literature.6,8–10,27

A 60% faster metabolic activity in GM compared with WM in our study is in line with differences reported in the rate of tricarboxylic acid cycle(68%) measured in 13C-studies28,29 but higher than [18F]FDG-PET literature values, which reported ~33% higher oxidative Glc consumption in GM than in WM.30–32 A visible decrease in the Glc6 resonance could be observed in Figure 4, but reliable fitting of the Glc resonances (labeled Glc6 and unlabeled Glc1–5) was not possible on voxel-wise level with comparable quality, presumably because of overlapping resonances in the region 3.5–4.0 ppm. For illustration purposes, metabolic map time courses without quality control thresholds are shown for all subjects in figure, Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/RLI/A798. To calculate quantitative flux parameters of Glc metabolism, detection of the Glc uptake by detecting the decrease in Glc6 resonances needs to be improved, but the main aim of this study was a qualitative assessment of oxidative downstream metabolites, which directly reflects Glc utilization.

In contrast to a direct detection of labeled substrates using DMI (2H-MRS/MRSI), 13C-MRS, or [18F]FDG-PET the indirect 1H-based QELT approach allows for simultaneous detection of labeled and unlabeled metabolites to quantify an extended neurochemical profile and requires no additional hardware or radioactive tracers.8–10 In comparison with recent publications presenting QELT MRSI results in animals9 and humans7,8,10 at ultrahigh field(≥7T) research systems, our approach provides motion-corrected 3D metabolite maps with high temporal stability,33 which were acquired with high spatial and temporal resolution on widely available clinical 3T MR scanners. Further improvements in spatial and temporal stability can be anticipated considering the wide range of state-of-the-art undersampling or super-resolution techniques in MRSI.34–36

Similar to DMI, a separation of healthy oxidative and pathologic anaerobic metabolic pathways, via simultaneous detection of Glx and lactate, is theoretically feasible using 1H-MRSI. However, only 2% of Glc is anaerobically converted in the healthy human brain, and thus, we could not reliably quantify lactate concentrations in our study. Future applications could focus on pathologies involving anaerobic Glc utilization, for example, types of brain tumors, but as this introduces additional technical challenges, this would extend the scope of this study. A residual contamination from subcutaneous fat outside of the brain due to, for example, a suboptimal point spread function18 additionally limits the detection of lactate. Fat suppression,37,38 volume selective excitation using spin-echo approaches or higher spatial resolution,39 could improve lactate detection in future studies involving pathologies with high lactate production,40 but we will further investigate the feasibility of lactate detection using our 1H FID MRSI sequence via simulations and experimental validation in the future.

Although our study shows only results for investigating Glc metabolism, deuterium labeling is not limited to Glc. A range of metabolites can be deuterium-labeled, for example, choline, acetate41 to study different metabolic pathways and pathologies—some of them even simultaneously using multiple tracers, for example, in tumors.42 This adds additional flexibility for designing clinical research studies. Deuterium-labeled Glc ([6,6′]-2H-Glc) is a safe and stable tracer and the price of the administered dose was under $1000 for each subject. However, this price is expected to drop upon mass production and the approval of cheaper approaches to synthesize, for example, deuterated Glc.43,44

Because of missing medical personnel, we were only able to sample blood Glc for 5 of 7 healthy participants for the initial measurement bout.

Oral administration was preferred over intravenous injection in favor of participant comfort. Compared with intravenous injection, an expected delayed response and slower increase in blood Glc isotopic enrichment after oral Glc uptake, together with a non-steady-state of blood Glc and relatively short measurement time limits possible calculation of quantitative flux rates,45 which was not the aim of this study. Intravenous tracer injection would allow additional blood sampling to estimate isotopic enrichment time courses as an input function to overcome those challenges in future studies.27 A previous study7 using DMI showed that the increase in deuterium-labeled Glx features an approximately linear behavior in the first 60 minutes after oral administration; therefore, our study used linear fitting as an approximation to estimate the dynamics of Glx, but this approach does not reflect real quantitative turnover rates. Other models, such as exponential fitting, has been applied previously but require longer scan times (eg, 2–3 hours) and the assessment of a true baseline. However, whether accurately quantifying flux rates via a lengthy acquisition provides sufficient added diagnostic value in patients remains to be shown.

In general, the presented measurement time of 60 minutes could still be considered too long for clinical application. Splitting the experiment into a short pre– (baseline) and post–Glc administration measurement after a defined pause would significantly reduce patient scan time.

We do not expect that subject repositioning would severely affect the quality and reliability of the data based on recent test-retest results at 7T46,47 and extrapolating expected quality changes from 7T to 3T based on comparison data.48,49

This study not only demonstrates the feasibility of dynamic 3D 1H-MRSI to noninvasively image Glc downstream metabolism in the human brain using deuterium-labeled Glc at widely available clinical 3T MR scanners but also suggests the possibility to map several other deuterated downstream metabolites of clinical interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding: WEAVE I 6037 and NIH R01EB031787. P.B. was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under a Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement, no. 846793, and by a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, no. 27238. This research was funded in whole, or part, by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) WEAVE I 6037. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.

Supplemental digital contents are available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.investigativeradiology.com).

Contributor Information

Lukas Hingerl, Email: lukas.hingerl@meduniwien.ac.at.

Bernhard Strasser, Email: bernhard.strasser@meduniwien.ac.at.

Petr Bednarik, Email: pbed.radiol@gmail.com.

Dario Goranovic, Email: dario.goranovic@meduniwien.ac.at.

Eva Niess, Email: eva.niess@meduniwien.ac.at.

Gilbert Hangel, Email: gilbert.hangel@meduniwien.ac.at.

Martin Krššák, Email: martin.krssak@meduniwien.ac.at.

Benjamin Spurny-Dworak, Email: benjamin.spurny-dworak@meduniwien.ac.at.

Thomas Scherer, Email: thomas.scherer@meduniwien.ac.at.

Rupert Lanzenberger, Email: rupert.lanzenberger@meduniwien.ac.at.

Wolfgang Bogner, Email: wolfgang.bogner@meduniwien.ac.at.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV. Otto Warburg's contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norat P Soldozy S Sokolowski JD, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurological disorders: exploring mitochondrial transplantation. NPJ Regen Med. 2020;5:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manji H Kato T Di Prospero NA, et al. Impaired mitochondrial function in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar M Nanga RPR Verma G, et al. Emerging MR imaging and spectroscopic methods to study brain tumor metabolism. Front Neurol. 2022;13:789355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Feyter HM Behar KL Corbin ZA, et al. Deuterium metabolic imaging (DMI) for MRI-based 3D mapping of metabolism in vivo. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaat7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruhm L Avdievich N Ziegs T, et al. Deuterium metabolic imaging in the human brain at 9.4 tesla with high spatial and temporal resolution. Neuroimage. 2021;244:118639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bednarik P Goranovic D Svatkova A, et al. Deuterium labeling enables non-invasive 3D proton MR imaging of glucose and neurotransmitter metabolism in the human brain at 7 T. Nat Biomed Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cember ATJ Wilson NE Rich LJ, et al. Integrating (1)H MRS and deuterium labeled glucose for mapping the dynamics of neural metabolism in humans. Neuroimage. 2022;251:118977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rich LJ Bagga P Wilson NE, et al. 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy of 2H-to-1H exchange quantifies the dynamics of cellular metabolism in vivo. Nat Biomed Eng. 2020;4:335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruhm L Ziegs T Wright AM, et al. Dynamic observation of 2H labeled compounds in the human brain with 1H versus 2H magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 9.4 T. bioRxiv. 2022. 2022.01.24.477582. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boumezbeur F Besret L Valette J, et al. NMR measurement of brain oxidative metabolism in monkeys using 13C-labeled glucose without a 13C radiofrequency channel. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaggie JD Khan AS Matys T, et al. Deuterium metabolic imaging and hyperpolarized (13)C-MRI of the normal human brain at clinical field strength reveals differential cerebral metabolism. Neuroimage. 2022;257:119284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogner W Hess AT Gagoski B, et al. Real-time motion- and B0-correction for LASER-localized spiral-accelerated 3D-MRSI of the brain at 3T. Neuroimage. 2014;88:22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hingerl L Strasser B Moser P, et al. Clinical high-resolution 3D-MR spectroscopic imaging of the human brain at 7T. Invest Radiol. 2020;55:239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moser P Eckstein K Hingerl L, et al. Intra-session and inter-subject variability of 3D-FID-MRSI using single-echo volumetric EPI navigators at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2020;83:1920–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin A Andronesi O Bogner W, et al. Minimum reporting standards for in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRSinMRS): experts' consensus recommendations. NMR Biomed. 2021;34:e4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogg RJ, Kingsley PB, Taylor JS. WET, a T1- and B1-insensitive water-suppression method for in vivo localized 1H NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson B. 1994;104:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hingerl L Bogner W Moser P, et al. Density-weighted concentric circle trajectories for high resolution brain magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:2874–2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilgic B Chatnuntawech I Fan AP, et al. Fast image reconstruction with L2-regularization. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40:181–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strasser B Chmelik M Robinson SD, et al. Coil combination of multichannel MRSI data at 7T: MUSICAL. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:1796–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Povazan M Hangel G Strasser B, et al. Mapping of brain macromolecules and their use for spectral processing of (1)H-MRSI data with an ultra-short acquisition delay at 7T. Neuroimage. 2015;121:126–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi C Coupland NJ Bhardwaj PP, et al. T2 measurement and quantification of glutamate in human brain in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasparovic C Song T Devier D, et al. Use of tissue water as a concentration reference for proton spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mlynarik V, Gruber S, Moser E. Proton T (1) and T (2) relaxation times of human brain metabolites at 3 tesla. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkinson M Beckmann CF Behrens TE, et al. FSL. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seres Roig E De Feyter HM Nixon TW, et al. Deuterium metabolic imaging of the human brain in vivo at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2023;89:29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreno A Bluml S Hwang JH, et al. Alternative 1-(13)C glucose infusion protocols for clinical (13)C MRS examinations of the brain. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan JW Stein DT Telang F, et al. Spectroscopic imaging of glutamate C4 turnover in human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shulman RG Rothman DL Behar KL, et al. Energetic basis of brain activity: implications for neuroimaging. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyder F Fulbright RK Shulman RG, et al. Glutamatergic function in the resting awake human brain is supported by uniformly high oxidative energy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:339–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hyder F, Rothman DL. Quantitative fMRI and oxidative neuroenergetics. Neuroimage. 2012;62:985–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu Y Herman P Rothman DL, et al. Evaluating the gray and white matter energy budgets of human brain function. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018;38:1339–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andronesi OC Bhattacharyya PK Bogner W, et al. Motion correction methods for MRS: experts' consensus recommendations. NMR Biomed. 2021;34:e4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bogner W, Otazo R, Henning A. Accelerated MR spectroscopic imaging—a review of current and emerging techniques. NMR Biomed. 2021;34:e4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iqbal Z Nguyen D Hangel G, et al. Super-resolution (1)H magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging utilizing deep learning. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hangel G Jain S Springer E, et al. High-resolution metabolic mapping of gliomas via patch-based super-resolution magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging at 7 T. Neuroimage. 2019;191:587–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tkac I Deelchand D Dreher W, et al. Water and lipid suppression techniques for advanced (1) H MRS and MRSI of the human brain: experts' consensus recommendations. NMR Biomed. 2021;34:e4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hangel G Strasser B Povazan M, et al. Lipid suppression via double inversion recovery with symmetric frequency sweep for robust 2D-GRAPPA-accelerated MRSI of the brain at 7T. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:1413–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hangel G Strasser B Povazan M, et al. Ultra-high resolution brain metabolite mapping at 7 T by short-TR Hadamard-encoded FID-MRSI. Neuroimage. 2018;168:199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maudsley AA Andronesi OC Barker PB, et al. Advanced magnetic resonance spectroscopic neuroimaging: experts' consensus recommendations. NMR Biomed. 2021;34:e4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polvoy I Qin H Flavell RR, et al. Deuterium metabolic imaging—rediscovery of a spectroscopic tool. Metabolites. 2021;11:570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veltien A van Asten J Ravichandran N, et al. Simultaneous recording of the uptake and conversion of glucose and choline in tumors by deuterium metabolic imaging. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujiwara Y Iwata H Sawama Y, et al. Method for regio-, chemo- and stereoselective deuterium labeling of sugars based on ruthenium-catalyzed C-H bond activation. Chem Commun (Camb). 2010;46:4977–4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W Rabeah J Bourriquen F, et al. Scalable and selective deuteration of (hetero)arenes. Nat Chem. 2022;14:334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreis F Wright AJ Hesse F, et al. Measuring tumor glycolytic flux in vivo by using fast deuterium MRI. Radiology. 2020;294:289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hangel G Spurny-Dworak B Lazen P, et al. Inter-subject stability and regional concentration estimates of 3D-FID-MRSI in the human brain at 7T. NMR Biomed. 2021;34:e4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heckova E Považan M Strasser B, et al. Effects of different macromolecular models on reproducibility of FID-MRSI at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2020;83:12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gruber S Heckova E Strasser B, et al. Mapping an extended neurochemical profile at 3 and 7T using accelerated high-resolution proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Invest Radiol. 2017;52:631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Motyka S Moser P Hingerl L, et al. The influence of spatial resolution on the spectral quality and quantification accuracy of whole-brain MRSI at 1.5 T, 3T, 7T, and 9.4 T. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82:551–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]