ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To identify lifestyle-related, sociodemographic, and mental health characteristics of people with insomnia symptoms and people without insomnia during the pandemic.

METHODS

A case-control study was conducted with data collected by snowball sampling using an online questionnaire. From November 2020 to April 2021, 6,360 people with a mean age of 43.5 years (SD = 14.3) participated in the survey. For this study, we considered 158 cases of insomnia disorder and 476 controls (three controls per case) randomly selected from the participants without sleep problems.

RESULTS

The results of the comparative analysis between cases and controls showed that sleeping less than six hours daily (OR = 3.89; 95%CI 2.50–6.05), feeling sadness frequently (OR = 2.95; 95%CI 1.69–5.17), residing in metropolitan areas (OR = 1.71; 95%CI 1.04–2.84), being 40 years or older (OR = 1.93; 95%CI 1.22–3.06), and the interaction between occupation and poorer education (OR = 2.12; 95%CI 1.22–3.69) were predictors for symptoms of insomnia disorder during the pandemic.

CONCLUSIONS

In addition to confirming the hypothesis that mental health problems are associated with insomnia symptoms, the results point to insomnia as an important outcome for studies on the effects of unemployment, vulnerability and low education of the population, especially in large cities, highlighting that the effects of the crisis on health and the economy are extremely unequally distributed.

Keywords: Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders, epidemiology; Risk Factors; Socioeconomic Factors; Case-Control Studies; COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

The covid-19 pandemic by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus has, since the first case reports, presented challenges for maintaining global health. Different social dynamics imposed by the health crisis induced people to confront a series of abrupt changes in their social routines and life habits1.

Studies prior to the covid-19 pandemic have already shown that home isolation recommendations or quarantines imposed on people potentially exposed to a contagious disease can cause manifestations of psychological illness, including symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, confusion, anxiety, depression, and burnout2-5. This condition of social withdrawal can also disrupt sleep, which is known to be associated with mental health6.

The pandemic context of covid-19 is already measured as an independent factor affecting sleep in the population, in which the most commonly self-reported complaint is insomnia7. Insomnia disorder is characterized by complaints of persistent and frequent difficulty falling asleep, maintaining sleep, frequent awakenings during sleep, or early morning awakenings, which occur despite the opportunity for sleep and reflect in daytime consequences or impairments8,9. Besides insomnia being the most recurrent complaint among people with sleep problems, it is also a risk factor for depression10.

In a previous study, 70% of the participants reported sleep problems and 80% anxiety symptoms during the pandemic. The most frequently reported symptom was difficulty falling asleep three or more times a week. Considering that sleep is crucial for the morphofunctional and emotional maintenance of the human body, our hypothesis is that people with mental health related problems were more likely to experience symptoms of insomnia during the pandemic11. In this context, the aim of this study was to identify lifestyle-related, sociodemographic, and mental health characteristics of people with insomnia symptoms (cases) and people without symptoms (controls) during the covid-19 pandemic. The cases were identified from a previous study11.

METHODS

Study Population

This is a case-control study nested within a population-based survey11 conducted by the Faculdade de Saúde Pública of Universidade de São Paulo, in collaboration with the Associação Brasileira do Sono (ABS) and the Associação Brasileira de Medicina do Sono (ABMS). Data were collected by snowball sampling via an online questionnaire during the covid-19 pandemic by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Invitations to participate were sent via the ABS social networks to the general population. Data collection was conducted from November 2020 to April 2021, in which 6,360 participants aged 10 to 87 years were included (mean age 43.5 years; SD = 14.3)11. From this database, cases and controls were randomly selected for the present study.

The sample size for this case-control study was calculated assuming an outcome frequency (insomnia symptoms) of 30%12, α = 5.0%, (1-β) = 90%, and a replacement rate of 20%. People who reported symptoms of insomnia were considered cases (158 cases). Three controls per case (476 controls) were randomly selected from the participants without sleep problems. No matching was performed between case and control according to education, occupation, age, or gender. This procedure was adopted to meet the objective of identifying the factors that could contribute to increasing the chance of developing insomnia in the sample studied.

The Ethics Committee of the Faculdade de Saúde Pública of the Universidade de São Paulo approved the study (#39395520.8.0000.5421) and participants were informed about its purpose and data use.

Data Collection and Tabulation

Participants answered questions about quality, duration, and symptoms related to the sleep-wake cycle (including timing) before and during the pandemic. Sociodemographic data on age, gender, education, and occupation were included in the questionnaire, as well as lifestyle data such as alcohol consumption, smoking, and their respective frequency. The nutritional status information was used to calculate the body mass index (BMI). Nutritional status was characterized according to the WHO classification. In addition, the questionnaire included questions related to habits before going to sleep, such as the use of electronic equipment, reading, exercising, among others.

The symptoms of insomnia included difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, and waking up early in the morning and not going back to sleep, according to a scale taken from the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire12. Sleep time was accessed by means of an open-ended question, adopting a Likert scale to assess satisfaction with sleep duration. The survey also included questions about the occurrence and frequency of nightmares, snoring, sleep apnea, bruxism, restless leg symptoms, sleepwalking, and napping before and during the pandemic period12.

The outcome “insomnia symptoms” was structured from the affirmative response to one of the three conditions that characterize it (difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and/or early morning awakening), with a frequency of three or more times per week12. Insomnia symptoms were considered a case when the first episode occurred during the pandemic.

Regarding mental health, the survey included questions about anxiety, depression, and burnout symptoms before and during the pandemic. Questions related to anxiety symptoms included feeling nervous, anxious, or not being able to stop or control worry. These anxiety symptoms were addressed using the Generalized anxiety disorder-2 (GAD-2) scale13. The questionnaire also included the frequency of depressed mood and anhedonia, addressing little interest or pleasure in doing things and feeling depressed, down or hopeless (Patient health questionnaire-2)14. The frequencies of both symptoms were classified into “not at all, several days, more than half of the days, almost every day.” In addition, the questionnaire also included a scale addressing burnout symptoms before and during the pandemic15. Chronotype was assessed by the final item of the morning-evening scale16, in which the respondent makes a self-assessment of their chronotype. The response was evaluated by the individual score of the respective item.

Participants who were employed, business owners, employers, or self-employed were grouped into the “active worker” category. Retired, student, and unemployed participants were grouped into the “non-working” category. For the analyses regarding occupation and education, the participants were divided into the following groups: active worker/no college degree; active worker/higher education; non-worker/no college degree; non-worker/ higher education.

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test of association was used to analyze the factors associated with insomnia. Then, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed, considering the variables with p < 0.200 in the univariate analysis. The risk measure was the odds ratio (OR) and multiple analysis by the stepwise forward method with the descriptive level p < 0.050. The fit of the models was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The software STATA version 14 was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 488 women and 146 men, totaling 634 participants, of whom 158 had symptoms of insomnia. The participants were adults between the ages of 18 and 79 from various regions of Brazil, with a higher concentration of respondents from Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. There was a statistically significant association between the presence of insomnia symptoms and age group (p = 0.013), education (p = 0.030), occupation (p < 0.001), and State (p = 0.019). Insomnia symptoms were more frequent among older participants, people with less education, and the unemployed (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of participants according to sociodemographic data and insomnia symptoms.

| Variable | Symptoms of insomnia | pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No | Yes | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender identity | |||||

| Female | 361 | 74 | 127 | 26 | 0.24 |

| Male | 115 | 78.8 | 31 | 21.2 | |

| Age Group | |||||

| 18 to 30 | 90 | 82.6 | 19 | 17.4 | 0.013 |

| 30 to 39 | 133 | 81.1 | 31 | 18.9 | |

| 40 to 49 | 95 | 66.9 | 47 | 33.1 | |

| 50 to 59 | 95 | 73.1 | 35 | 26.9 | |

| 60 to 79 | 63 | 70.8 | 26 | 29.2 | |

| Having children | |||||

| No | 211 | 75.1 | 70 | 24.9 | 0.996 |

| Yes | 265 | 75.1 | 88 | 24.9 | |

| Education | |||||

| High school complete or less | 78 | 67.2 | 38 | 32.8 | 0.03 |

| Incomplete higher education | 56 | 70 | 24 | 30 | |

| Higher education complete | 129 | 74.6 | 44 | 25.4 | |

| Postgraduate | 213 | 80.4 | 52 | 19.6 | |

| Occupation | |||||

| Retired | 47 | 66.2 | 24 | 33.8 | < 0.001 |

| Unemployed | 47 | 58 | 34 | 42 | |

| Employed | 192 | 80.7 | 46 | 19.3 | |

| Entrepreneur/employer | 31 | 86.1 | 5 | 13.9 | |

| Student | 42 | 65.6 | 22 | 34.4 | |

| Liberal professional | 117 | 81.3 | 27 | 18.8 | |

| State (place of residence) | |||||

| São Paulo | 149 | 81.4 | 34 | 18.6 | 0.019 |

| Rio de Janeiro | 97 | 67.8 | 46 | 32.2 | |

| Other | 230 | 74.7 | 78 | 25.3 | |

| Nutritional statusb | |||||

| Underweight or eutrophic | 207 | 77.5 | 60 | 22.5 | 0.365 |

| Overweight | 151 | 71.9 | 59 | 28.1 | |

| Obesity | 118 | 75.6 | 38 | 24.4 | |

|

| |||||

| Total | 476 | 75.1 | 158 | 24.9 | |

a Chi-square test.

b Total less than 634 due to no response.

The results of the univariate analysis showed that the participants most likely to have symptoms of insomnia were those who slept less than six hours daily (p < 0.001), were dissatisfied with sleep duration before and during the pandemic (p < 0.001), were dissatisfied with sleep quality before and during the pandemic (p < 0.001), experienced excessive daytime sleepiness (p = 0.021), reported sleep apnea (p = 0.012), woke up with a headache (p = 0.001), had nightmares (p = 0.010), felt discomfort in their legs or needed to move their legs at bedtime (p < 0.001), and woke up feeling tired (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Distribution of participants according to sleep characteristics and insomnia symptoms.

| Variable | Symptoms of insomnia | pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No | Yes | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Self-perception of chronotype | |||||

| Definitely active in the morning | 224 | 77.2 | 66 | 22.8 | 0.508 |

| Somewhat active in the morning | 77 | 76.2 | 24 | 23.8 | |

| Definitely active at night | 108 | 73.5 | 39 | 26.5 | |

| Somewhat active at night | 65 | 70.7 | 27 | 29.3 | |

| No information | 2 | 50 | 2 | 50 | |

| Total sleep time during the pandemicb | |||||

| 6 hours or more | 394 | 84 | 75 | 16 | < 0.001 |

| Less than 6 hours | 75 | 50 | 75 | 50 | |

| Satisfaction with sleep duration (≥ 6 hours)b | |||||

| Had enough sleep before and during | 372 | 85.1 | 65 | 14.9 | < 0.001 |

| Had insufficient sleep before and got better during | 20 | 66.7 | 10 | 33.3 | |

| Had enough sleep before and got worse during | 63 | 52.1 | 58 | 47.9 | |

| Had insufficient sleep before and during | 12 | 41.4 | 17 | 58.6 | |

| Satisfaction with sleep quality (before and during the pandemic)b | |||||

| Good quality before and after | 320 | 88.9 | 40 | 11.1 | < 0.001 |

| Poor quality before and good quality after | 31 | 88.6 | 4 | 11.4 | |

| Good quality before and bad quality after | 92 | 56.8 | 70 | 43.2 | |

| Poor quality before and after | 25 | 37.9 | 41 | 62.1 | |

| Snoring | |||||

| No | 342 | 76.2 | 107 | 23.8 | 0.323 |

| Yes | 134 | 72.4 | 51 | 27.6 | |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | |||||

| No | 339 | 77.8 | 97 | 22.2 | 0.021 |

| Yes | 137 | 69.2 | 61 | 30.8 | |

| Sleep Apnea | |||||

| No | 432 | 76.6 | 132 | 23.4 | 0.012 |

| Yes | 44 | 62.9 | 26 | 37.1 | |

| Grinding or clenching of teeth during sleep | |||||

| No | 334 | 75.7 | 107 | 24.3 | 0.563 |

| Yes | 142 | 73.6 | 51 | 26.4 | |

| Waking up with a headache | |||||

| No | 304 | 79.6 | 78 | 20.4 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 172 | 68.3 | 80 | 31.7 | |

| Nightmares | |||||

| No | 376 | 77.5 | 109 | 22.5 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 100 | 67.1 | 49 | 32.9 | |

| Leg discomfort or the need to move legs at bedtime | |||||

| No | 393 | 80.7 | 94 | 19.3 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 83 | 56.5 | 64 | 43.5 | |

| Waking up feeling tired | |||||

| No | 235 | 87.4 | 34 | 12.6 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 241 | 66 | 124 | 34 | |

| Sleepwalking | |||||

| No | 470 | 92.2 | 40 | 154 | 0.266 |

| Yes | 6 | 13 | 40 | 4 | |

| No problem | |||||

| No | 475 | 75 | 158 | 25 | 0.564 |

| Yes | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

|

| |||||

| Total | 476 | 75.1 | 158 | 24.9 | |

a Chi-square test.

b Total less than 634 due to no response.

All symptoms associated with characteristics of mental health impairment showed statistically significant association with insomnia symptoms (p < 0.001). Participants who reported increased stress or anxiety symptoms during the pandemic had a higher frequency of insomnia symptoms (29.7%) than the others (8.4%).

The frequency of insomnia symptoms was highest among those who reported little interest/enjoyment in doing things and/or feeling sadness/depression/lack of hope at an almost daily frequency (49.6%), followed by those who reported frequency on more than half of the days of the week (30.4%), and lowest among those who reported frequency a few times a week or once in a while (16.0%) or not at all (9.5%).

Insomnia symptoms were present in 52.5% of the participants who complained about nervousness/anxiety on an almost daily basis; 24% of those who reported it on more than half of the days of the week; 17.6% on an occasional basis; and 5.1% of those who reported not having any. The presence or absence of burnout syndrome symptoms also pointed to statistically significant differences in terms of frequency of insomnia symptoms (40.0% versus 17.2%, respectively).

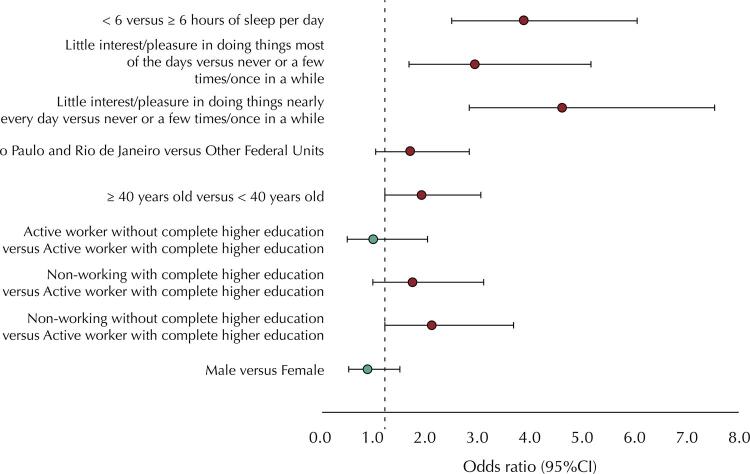

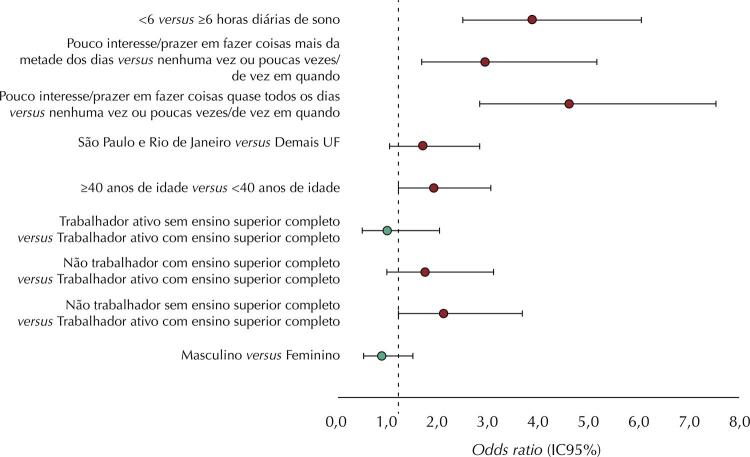

Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the independent characteristics statistically associated with the presence of insomnia symptoms were: total sleep time less than 6h (OR = 3.89; 95%CI 2.50–6.05), depression symptoms on more than half of the days (OR = 2.95; 95%CI 1.69–5.17) or almost daily (OR = 4.62; 95%CI 2.84–7.53), States of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (OR = 1.71; 95%CI 1.04–2.84), age group over 40 years (OR = 0.93; 95%CI 1.22–3.06), and the interaction between occupation and poorer education (retired/unemployed/student and without complete college education) (OR = 2.12; 95%CI 1.22–3.69). The model was controlled for gender, and residual analysis using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (c2= 3.64; p = 0.888) showed good model fit (Figure).

Figure. Independent factors associated with insomnia symptoms by multiple regression analysis.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study showed that sleeping less than six hours a day, feeling sad frequently, residing in a metropolis, being 40 years old or older, and the interaction of occupation and poorer education were predictors for insomnia symptoms during the pandemic. In addition to confirming the hypothesis that mental health symptoms are associated with insomnia symptoms, this study revealed, in an unprecedented way, the interaction between education and occupation as a risk factor for the development of insomnia symptoms. This result was evident in a pandemic scenario, in which people with low education and unemployed were the ones who suffered the most from economic restrictions with the reduction of informal work and, in many cases, the impossibility of obtaining income. In June 2020, for example, the period prior to the present study, the National Household Sample Survey (Pnad) revealed that the level of occupation of the population was around 49% in the first three weeks of the month17 .This represents an increase of 1.3 points in the unemployment rate in relation to the quarter before the lockdown decree, reaching a record level of the population outside the labor market18.

The increase in job insecurity during the pandemic and its consequent impact on the most vulnerable population, not only from a financial point of view, but also in terms of mental and physical health, including the effects of prejudice and domestic violence, is undeniable19. A recent systematic review with 7,744,469 participants from 110,249 different regions of the world demonstrated the association between inadequate income and poor mental health20. Considering the association between insomnia and mental health, the present study places insomnia as an important outcome for studies on the effects of unemployment, vulnerability, and low education of the population, especially in large metropolises, emphasizing that the effects of the crisis on health and the economy are extremely unequally distributed18.

A recent study conducted in Hong Kong with 3,000 participants21 identified that the sociodemographic factors associated with impairment in pandemic-related psychological experience were: middle age, low education, unemployment, low income, and watching pandemic news reports daily for more than one hour. Brooks et al.3 identified as stressors longer duration of lockdown, fears about infection, frustration, boredom, inadequate supply, disorientation, financial losses, and stigma. The results of these and the present study reinforce the thesis that prolonged isolation and lack of support exacerbated existing vulnerabilities and contributed to the emergence of stress-related disorders, suggesting that the covid-19 pandemic period should be considered from the perspective of a mass traumatic event21,22 Furthermore, these studies point out that, besides the need for public actions to promote financial assistance to vulnerable populations, it is of utmost relevance to offer mental health assistance in health emergencies.

It is worth noting that the increase in mental health problems and insomnia during the pandemic has been evidenced in studies conducted in various countries and population groups. A cutoff study that followed for 10 years the natural course of insomnia in 1434 adults in Canada contacted participants for a survey on insomnia, perceived stress, and other psychological symptoms during the pandemic. The data revealed an incidence of insomnia about four times higher than that reported in a similar interval in the pre-pandemic period23. A study in Sweden showed similar results with 45% of people meeting criteria for depression, anxiety, or insomnia24. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania conducted a longitudinal study conducted over 2020 in which they included 3560 participants. The results suggest that concerns about covid-19 were a more consistent predictor of insomnia than exposure to the virus itself25. A meta-analysis of 66 studies (n = 221,970) was conducted to assess the prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia, during the pandemic in different population groups26. The authors noted that patients with chronic illnesses, people in lockdown, patients with suspected covid, doctors and nurses had a higher prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress and insomnia. In another meta-analysis (68 studies; n = 189,159) the mental health consequences of covid-19 were found to be equally high in all affected countries and for all genders27.

Such data indicate that the mode of coping in the face of covid-19 was important in mental health and sleep issues of the population. The association between hopelessness/ sadness/depression and the presence of insomnia symptoms in the present study supports the relevance of this two-way street between mental health and insomnia.

The present study also revealed an increased chance of developing insomnia symptoms starting at age 40. The reduction in sleep duration in this age group corroborates the literature in the area. A US population survey, for example, shows that sleep duration over the life course is U-shaped, i.e., it decreases with aging, reaching a minimum at age 40, and increases around age 5028. However, insomnia may not be the only hypothesis for reduced sleep in this age group. In addition, it is important to note that the prevalence of insomnia symptoms in the adult population is associated with conditions of vulnerability, such as low socioeconomic status, poor health status, including physical and psychiatric aspects, and low quality of life29.

Psycho-educational programs in crisis situations and/or among populations at high risk of burnout have shown that cultivating positive feelings, behaviors, and thoughts favors emotional resilience, inhibiting the development of symptoms of insomnia, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and burnout30. During the pandemic, programs of this nature demonstrated that careful counseling regarding healthy behaviors associated with strategies for early identification of emotional problems favored improvements in psychological parameters such as resilience, well-being, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, mood, as well as better pandemic management31. In Brazil, despite the large contingent of psychologists working at the Unified Health System (SUS) and Reference Centers for Social Assistance (Reference Center for Social Assistance - Cras and Specialized Reference Center for Social Assistance - Creas), approximately 40,000 and 8,000 professionals, respectively, the organization of task forces and the use of digital platforms and telepsychology for intervention and guidance of socioemotional skills among the population have not been adequately planned32.

This study has some limitations worth mentioning. Collecting data through social media may have generated the bias of attracting people with sleep problems, somatic symptom disorders, or simply interested in the topic. The use of the data collected for a case-control study sought to mitigate this possible bias. Despite this, there is a predominance of the female gender in the study. It is also important to mention that the sample is not representative of all regions in the country.

On the other hand, the results presented here are important to support actions and public policies for mental health care, especially in health emergencies. In addition, they reinforce the need for screening and early intervention of sleep problems, which are determinants for the health and quality of life of the population and point to the need for measures of attention to mental health and sleep in the post-isolation pandemic phase in order to shorten the suffering of the most vulnerable population.

Funding Statement

Funding: Associação Brasileira de Sono, 2021. Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (Capes - Funding code 001).

Footnotes

Funding: Associação Brasileira de Sono, 2021. Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (Capes - Funding code 001).

REFERENCES

- 1.1. Mesenburg MA, Hallal PC, Menezes AM, Barros AJ, Horta BL, Barros FC, et al. Chronic non-communicable diseases and covid-19: EPIcovid-19 Brazil results. Rev Saude Publica. 2021 Jun;55:38. 10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055003673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Mesenburg MA, Hallal PC, Menezes AM, Barros AJ, Horta BL, Barros FC, et al. Chronic non-communicable diseases and covid-19: EPIcovid-19 Brazil results. Rev Saude Publica. 2021 Jun;55:38. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055003673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2. Adler AB, Kim PY, Thomas SJ, Sipos ML. Quarantine and the U.S. military response to the Ebola crisis: soldier health and attitudes. Public Health. 2018 Feb;155:95-8. 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed]; Adler AB, Kim PY, Thomas SJ, Sipos ML. Quarantine and the U.S. military response to the Ebola crisis: soldier health and attitudes. Public Health. 2018 Feb;155:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.3. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020 Mar;395(10227):912-20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020 Mar;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.4. Lavie P. Sleep disturbances in the wake of traumatic events. N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec;345(25):1825-32. 10.1056/NEJMra012893 [DOI] [PubMed]; Lavie P. Sleep disturbances in the wake of traumatic events. N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec;345(25):1825–1832. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.5. White DP. Tragedy and insomnia. N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec;345(25):1846-8. 10.1056/NEJM200112203452513 [DOI] [PubMed]; White DP. Tragedy and insomnia. N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec;345(25):1846–1848. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200112203452513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.6. Freeman D, Sheaves B, Waite F, Harvey AG, Harrison PJ. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jul;7(7):628-37. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30136-X [DOI] [PubMed]; Freeman D, Sheaves B, Waite F, Harvey AG, Harrison PJ. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jul;7(7):628–637. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.7. Lin L yu, Wang J, Ou-yang X yong, Miao Q, Chen R, Liang F xia, et al. The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (covid-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Med 2021; 77: 348-354. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; yu Lin L, Wang J, yong Ou-yang X, Miao Q, Chen R, xia Liang F, et al. The immediate impact of the 2019 novel coronavirus (covid-19) outbreak on subjective sleep status. Sleep Med. 2021;77:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.8. Perez MN, Salas RM. Insomnia. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2020 Aug;26(4):1003-15. 10.1212/CON.0000000000000879 [DOI] [PubMed]; Perez MN, Salas RM. Insomnia. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2020 Aug;26(4):1003–1015. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.9. Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014 Nov;146(5):1387-94. 10.1378/chest.14-0970 [DOI] [PubMed]; Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014 Nov;146(5):1387–1394. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.10. Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011 Dec;135(1-3):10-9. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed]; Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011 Dec;135(1-3):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.11. Moreno CR, Conway SG, Assis M, Genta PR, Pachito DV, Tavares Junior A, et al. covid-19 pandemic is associated with increased sleep disturbances and mental health symptoms but not help-seeking: a cross-sectional nation-wide study. Sleep Sci. 2022;15(1):1-7. 10.5935/1984-0063.20220027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Moreno CR, Conway SG, Assis M, Genta PR, Pachito DV, Tavares A, Junior, et al. covid-19 pandemic is associated with increased sleep disturbances and mental health symptoms but not help-seeking: a cross-sectional nation-wide study. Sleep Sci. 2022;15(1):1–7. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20220027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.12. Nordin M, Åkerstedt T, Nordin S. Psychometric evaluation and normative data for the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2013;11(4):216-26. 10.1111/sbr.12024 [DOI]; Nordin M, Åkerstedt T, Nordin S. Psychometric evaluation and normative data for the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2013;11(4):216–226. doi: 10.1111/sbr.12024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.13. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, Chanpura T, Lopp L. Using generalized anxiety disorder-2 (GAD-2) and gad-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020 May;12(5):e8224. 10.7759/cureus.8224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, Chanpura T, Lopp L. Using generalized anxiety disorder-2 (GAD-2) and gad-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020 May;12(5):e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.14. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003 Nov;41(11):1284-92. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C [DOI] [PubMed]; Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003 Nov;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.15. Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, Joos S, Fihn SD, Nelson KM, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 May;30(5):582-7. 10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6 PMID:25451989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, Joos S, Fihn SD, Nelson KM, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 May;30(5):582–587. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6. PMID:25451989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.16. Horne JA, Östberg O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976;4(2):97-110. [PubMed]; Horne JA, Östberg O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976;4(2):97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.17. Lameiras MAP, Cavalcanti MAFH. PNAD covid-19: divulgação de 17/7/2020: principais destaques. Carta Conjuntura. 2020[cited 2022 Feb 10];(38,3º trimestre). Available from: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/10163/2/CC_48_pnad_covid-19.pdf ; Lameiras MAP, Cavalcanti MAFH. PNAD covid-19: divulgação de 17/7/2020: principais destaques. [cited 2022 Feb 10];Carta Conjuntura. 2020 http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/10163/2/CC_48_pnad_covid-19.pdf 38,3º trimestre. [Google Scholar]

- 18.18. Castro D, Bosquerolli A, Fujarra B, Rodrigues G, Colaço H, Oliveira H, et al. Brasil e o mundo diante da crise econômica e da Covid-19. Universidade Federal do Parana. PET Economia UFPR. 2020[cited 2022 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.ufpr.br/portalufpr/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Brasil-e-o-mundo-diante-da-Covid-19-e-da-crise-economica.pdf ; Castro D, Bosquerolli A, Fujarra B, Rodrigues G, Colaço H, Oliveira H, et al. Brasil e o mundo diante da crise econômica e da Covid-19. Universidade Federal do Parana. PET Economia UFPR; 2020. [cited 2022 Feb 10]. https://www.ufpr.br/portalufpr/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Brasil-e-o-mundo-diante-da-Covid-19-e-da-crise-economica.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.19. Almondes KM, Bizarro L, Miyazaki MC, Soares MR, Peuker AC, Teodoro M, et al. Comparative analysis of psychology responding to covid-19 pandemic in Brics nations. Front Psychol. 2021 Jun;12:567585. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.567585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Almondes KM, Bizarro L, Miyazaki MC, Soares MR, Peuker AC, Teodoro M, et al. Comparative analysis of psychology responding to covid-19 pandemic in Brics nations. 567585Front Psychol. 2021 Jun;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.567585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.20. Tibber MS, Walji F, Kirkbride JB, Huddy V. The association between income inequality and adult mental health at the subnational level-a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022 Jan;57(1):1-24. 10.1007/s00127-021-02159-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Tibber MS, Walji F, Kirkbride JB, Huddy V. The association between income inequality and adult mental health at the subnational level-a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022 Jan;57(1):1–24. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02159-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.21. Cao Y, Siu JY, Shek DT, Shum DH. covid-19 one year on: identification of at-risk groups for psychological trauma and poor health-protective behaviour using a telephone survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2022 Apr;22(1):252. 10.1186/s12888-022-03904-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Cao Y, Siu JY, Shek DT, Shum DH. covid-19 one year on: identification of at-risk groups for psychological trauma and poor health-protective behaviour using a telephone survey. 252BMC Psychiatry. 2022 Apr;22(1) doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03904-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.22. Horesh D, Brown AD. Traumatic stress in the age of covid-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychol Trauma. 2020 May;12(4):331-5. 10.1037/tra0000592 [DOI] [PubMed]; Horesh D, Brown AD. Traumatic stress in the age of covid-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychol Trauma. 2020 May;12(4):331–335. doi: 10.1037/tra0000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.23. Morin CM, Vézina-Im LA, Ivers H, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Philip P, Lamy M, et al. Prevalent, incident, and persistent insomnia in a population-based cohort tested before (2018) and during the first-wave of covid-19 pandemic (2020). Sleep. 2022 Jan;45(1):1-6. 10.1093/sleep/zsab258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Morin CM, Vézina-Im LA, Ivers H, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Philip P, Lamy M, et al. Prevalent, incident, and persistent insomnia in a population-based cohort tested before (2018) and during the first-wave of covid-19 pandemic (2020) Sleep. 2022 Jan;45(1):1–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.24. McCracken LM, Badinlou F, Buhrman M, Brocki KC. Psychological impact of covid-19 in the Swedish population: depression, anxiety, and insomnia and their associations to risk and vulnerability factors. Eur Psychiatry. 2020 Aug;63(1):e81. 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; McCracken LM, Badinlou F, Buhrman M, Brocki KC. Psychological impact of covid-19 in the Swedish population: depression, anxiety, and insomnia and their associations to risk and vulnerability factors. Eur Psychiatry. 2020 Aug;63(1):e81. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.25. Brown LA, Hamlett GE, Zhu Y, Wiley JF, Moore TM, DiDomenico GE, et al. Worry about covid-19 as a predictor of future insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2022 Oct;31(5):e13564. 10.1111/jsr.13564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Brown LA, Hamlett GE, Zhu Y, Wiley JF, Moore TM, DiDomenico GE, et al. Worry about covid-19 as a predictor of future insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2022 Oct;31(5):e13564. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.26. Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Niu J, Yin X, Xie J, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021 Feb;281:91-8. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Niu J, Yin X, Xie J, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021 Feb;281:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.27. Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad PG, Mukunzi JN, McIntee SE, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021 Jan;295:113599. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad PG, Mukunzi JN, McIntee SE, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021 Jan;295:113599. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.28. Su S, Li X, Xu Y, McCall WV, Wang X. Epidemiology of accelerometer-based sleep parameters in US school-aged children and adults: NHANES 2011-2014. Sci Rep. 2022 May;12(1):7680. 10.1038/s41598-022-11848-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Su S, Li X, Xu Y, McCall WV, Wang X. Epidemiology of accelerometer-based sleep parameters in US school-aged children and adults: NHANES 2011-2014. 7680Sci Rep. 2022 May;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-11848-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.29. Dopheide JA. Insomnia overview: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and monitoring, and nonpharmacologic therapy. Am J Manag Care. 2020 Mar;26(4 Suppl):S76-84. 10.37765/ajmc.2020.42769 [DOI] [PubMed]; Dopheide JA. Insomnia overview: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and monitoring, and nonpharmacologic therapy. Am J Manag Care. 2020 Mar;26(4 Suppl):S76–S84. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2020.42769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.30. Sánchez-Hernández Ó, Barkavi-Shani M, Bermejo RM. Promotion of resilience and emotional self-care in families and health professionals in times of covid-19. Front Psychol. 2022 Mar;13:879846. 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Sánchez-Hernández Ó, Barkavi-Shani M, Bermejo RM. Promotion of resilience and emotional self-care in families and health professionals in times of covid-19. 879846Front Psychol. 2022 Mar;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.31. Sánchez-Hernández Ó, Canales A. Eficacia y Satisfacción del Programa Resiliencia y Bienestar: quédate en casa. Rev Psicoter. 2020;31(117):381-98. 10.33898/rdp.v31i117.389 [DOI]; Sánchez-Hernández Ó, Canales A. Eficacia y Satisfacción del Programa Resiliencia y Bienestar: quédate en casa. Rev Psicoter. 2020;31(117):381–398. doi: 10.33898/rdp.v31i117.389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.32. Almondes KM, Teodoro ML. Terapia on-line. Belo Horizonte: Artesã, 2021.; Almondes KM, Teodoro ML. Terapia on-line. Belo Horizonte: Artesã; 2021. [Google Scholar]