Abstract

Purpose

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a highly prevalent and potentially serious sleep disorder, requires effective screening tools. Saliva is a useful biological fluid with various metabolites that might also influence upper airway patency by affecting surface tension in the upper airway. However, little is known about the composition and role of salivary metabolites in OSA. Therefore, we investigated the metabolomics signature in saliva from the OSA patients and evaluated the associations between identified metabolites and salivary surface tension.

Methods

We studied 68 subjects who visited sleep clinic due to the symptoms of OSA. All underwent full-night in-lab polysomnography. Patients with apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) < 10 were classified to the control, and those with AHI ≥ 10 were the OSA groups. Saliva samples were collected before and after sleep. The centrifuged saliva samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography with high-resolution mass spectrometry (ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; UPLC-MS/MS). Differentially expressed salivary metabolites were identified using open source software (XCMS) and Compound Discoverer 2.1. Metabolite set enrichment analysis (MSEA) was performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0. The surface tension of the saliva samples was determined by the pendant drop method.

Results

Three human-derived metabolites (1-palmitoyl-2-[5-hydroxyl-8-oxo-6-octenoyl]-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine [PHOOA-PC], 1-palmitoyl-2-[5-keto-8-oxo-6-octenoyl]-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine [KPOO-PC], and 9-nitrooleate) were significantly upregulated in the after-sleep salivary samples from the OSA patients compared to the control group samples. Among the candidate metabolites, only PHOOA-PC was correlated with the AHI. In OSA samples, salivary surface tension decreased after sleep. The differences in surface tension were negatively correlated with PHOOA-PC and 9-nitrooleate concentrations. Furthermore, MSEA revealed that arachidonic acid-related metabolism pathways were upregulated in the after-sleep samples from the OSA group.

Conclusions

This study revealed that salivary PHOOA-PC was correlated positively with the AHI and negatively with salivary surface tension in the OSA group. Salivary metabolomic analysis may improve our understanding of upper airway dynamics and provide new insights into novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets in OSA.

Keywords: Sleep apnea, obstructive; saliva; metabolomics; phosphatidylcholines; surface tension; biomarkers; airway resistance; sleep

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a very common but potentially serious sleep disorder. OSA is characterized by repetitive partial or complete cessation of airflow due to the closure and re-opening of the upper airway during sleep. Therefore, OSA patients experience rapid fluctuations in oxygen concentration during sleep, increasing their risk for cardiovascular diseases (CVD), metabolic syndrome, and neurocognitive problems.1 Various screening tools have been developed for the early detection of OSA, including anatomical indices such as the Mallampati and Friedman indices, as well as questionnaires including the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and STOP-Bang. However, due to the limited diagnostic accuracy of these methods, novel methods for screening OSA are still highly needed.2 A recent review article summarizing the available evidence on OSA biomarkers suggested that an optimal screening test should be clinically sensitive, specific, simple, timely, inexpensive, and correlated to disease severity.3 Furthermore, biomarkers should be able to reflect the functional changes that accompany OSA, as well as making pathophysiological sense.4,5 Thus, many researchers have sought to find biomarkers that satisfy the aforementioned criteria using various biological fluids, including blood, urine, and saliva. Several candidates in blood and urine have been suggested, including C-reactive protein, erythropoietin, interleukin (IL)-6, uric acid, and hemoglobin A1c.6,7,8,9,10 However, the diagnostic efficacy of these candidate biomarkers has not yet been successfully confirmed.

Saliva is an important resource for evaluating physical conditions, as it originates from the salivary glands and blood. The thin layer of epithelial cells separating the salivary duct from the systemic circulation allows various substances to be transferred to the saliva through multiple transport systems.11 Other studies have reported that monitoring salivary metabolites contributes to diagnosing or predicting both systemic changes and oral conditions. Thus, saliva may reflect the state of whole-body metabolism.12 In addition, saliva is a major component of the upper airway lining liquid (UALL). The surface tension of saliva controls the adhesion between the walls of the upper airway, and this surface tension is regulated by the phospholipids in saliva.13 Therefore, we speculated that salivary fluids could be a meaningful specimen for identifying OSA biomarkers.

Metabolomics has recently emerged in the field of “omics,” a scientific and technological field ranging from the characterization of metabolites to the study on metabolism in biological systems.14,15 The goal of untargeted metabolomics in biomarker research is to measure as many metabolites as possible from a sample without bias.16 The wide range of applications of metabolomics is increasingly expanding with the goals of diagnosing diseases, understanding their mechanisms, finding novel drug targets, individualizing treatments, and monitoring therapeutic outcomes.14

In this study, we investigated the salivary metabolic signature reflecting OSA by mass spectrometry-based untargeted metabolomics and evaluated its potential as a diagnostic and/or therapeutic surrogate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

From July 2013 to June 2015, a total of 70 subjects aged 20 to 66 were enrolled in this study among patients with suspected OSA at the otolaryngology-head and neck surgery department of St. Vincent’s Hospital in Suwon, Republic of Korea. The exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: 1) severe airway obstruction such as diffuse nasal polyposis, 2) craniofacial anomalies, 3) neuromuscular and cerebrovascular disease, and 4) a prior operation or diagnostic history of cardiopulmonary disease. The final participants had not previously been diagnosed with OSA. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Catholic Medical Center Clinical Research Coordinating Center approved this study protocol. (VC15TISI0079)

Collection of saliva samples

Approximately 500 µL saliva samples were collected in polypropylene vials before and after full-night polysomnography (PSG) test (within 30 minutes before sleep, and after waking up), as recommended by the manufacturer (Part number 5016.02 and 5004.01-06; Salimetrics LLC, State College, PA, USA). The collected saliva samples were immediately refrigerated and frozen at −80°C within 4 hours of collection for long-term storage.

In-lab polysomnography

PSG was performed in a fully attended manner with RemLogic-E version 3.4.1 software and Embla N7000/S7000 hardware (Embla Systems Inc., Broomfield, CO, USA). Physiological variables were recorded with 4 EEG channels, 2 EOG channels, 1 ECG lead, 3 EMG channels (chin, anterior tibialis muscles, right and left), and 1 body position sensor. Respiratory variables were monitored with a nasal pressure transducer, an oral thermistor, thoracic and abdominal belts (piezo type), a pulse oximeter, and a snoring sensor. Sleep stages, EEG arousals, and respiratory events were scored according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines.17 The Apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was calculated as the total number of apnea and hypopnea episodes divided by the total sleep time (hours). In this study, subjects were divided based on the AHI into control (< 10 events per hour) and OSA (≥ 10 events per hour) groups.

Sample preparation

Seventy subjects provided saliva samples before and after sleep; these samples are hereinafter referred to as before-sleep and after-sleep samples, respectively. In order to prepare samples for ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis, frozen saliva samples were thawed at room temperature, vortexed for 30 seconds, and then sonicated for 1 minute. To precipitate proteins, 150 µL of saliva was added to 450 µL of methanol, mixed by vigorous vortexing for 30 seconds, and then sonicated for 1 minute. The sample was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and then a supernatant of about 600 µL was transferred to a new 1.5-mL tube. The supernatant was concentrated using SpeedVac at room temperature for 4 hours. The residue was reconstituted in 30 µL of 50% methanol. Four quality control samples were obtained from a mixture of equal volumes from all the samples and analyzed together to ensure the quality of the experiment.

Among 70 pairs of collected saliva samples, two were excluded because they did not meet the minimum amount for analysis; therefore, 68 pairs of saliva samples were analyzed in this study (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Flow chart of subject selection and identification of metabolites. (A) Flow chart of subject selection and exclusion. (B) Workflow of untargeted metabolomic analysis. (C) Study flow of metabolite set enrichment analysis.

AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; PHOOA-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-hydroxyl-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; KPOO-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-keto-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; MSEA, metabolite set enrichment analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

UPLC-MS/MS

Mass-grade methanol, acetonitrile, water, and formic acid were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Saliva sample separation was performed on a Hypersil GOLD C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) using an Ultimate 3000 (Dionex, Idstein, Germany). The column was maintained at 30°C and a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The injection volume was 5 μL for each run. The mobile phase was 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B). The elution gradient was as follows: 0-1.0 min, 10% B; 1.0-16.5 min, linearly increasing from 10%–100% B; 16.5–17.5 minutes, 100% B isocratic; 17.5–18.0 minutes, linearly decreasing from 100%–10% B; 18.0–20.0 minutes, 10% B isocratic. The UPLC system was coupled to a Q-Exactive Plus (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with a heated electrospray ionization (HESI) source. The MS was operated in positive ion mode and the scan range was from m/z 100 to 1,000 in the full scan-ddMS2 mode. The working conditions for the HESI source were as follows; spray voltage, 3.5 kV; capillary temperature, 253°C; and sheath gas and auxiliary gas, 46 and 11 arbitrary units, respectively. The automatic gain control target was 3 × 10−6 with a maximum injection time of 100 ms.

Data processing

XCMS online software (https://xcmsonline.scripps.edu/),18 and Compound Discoverer 2.1 software (Thermo Scientific; https://planetorbitrap.com/compound-discoverer)19 were used to characterize the metabolites. In XCMS, a pairwise job was used to compare the control and patient samples. Metabolite and fragment identification was performed using the METLIN database based on their m/z signature and isotope patterns. In addition, raw data were processed using the Compound Discoverer 2.1 software. The processing procedure involved the selection of spectra, retention time alignment, and unknown compound detection and grouping using mzCloud.

Measurement of surface tension

Surface tension was measured by capturing images of 2–3 μL saliva samples from the patients or normal control hanging at the edge of a syringe needle (200 μm outer diameter) as a pendant shape using a commercial contact angle measurement apparatus (Smartdrop; FemtoBiomed, Inc., Seongnam, Korea). The surface tension of saliva was calculated by using the theoretical model of the pendant drop method, which is based on the Young-Laplace equation.20

Metabolite set enrichment analysis

Pathway analysis was performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca) to identify altered metabolic pathways by comparisons between various combinations of saliva samples.21 All m/z peaks, P values, and t-scores identified by XCMS, were input into the “Functional Analysis” module. The mummichog or gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) algorithms were selected to generate pathway scatter plots and bar graphs with normalized enriched scores (NES), respectively. In addition, a combination of the mummichog and GSEA algorithms was used to conduct the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) global network analysis. In the mummichog algorithm, pathway significance was calculated using the default top 10% of peaks by P value (automatically calculated by MetaboAnalyst) with the Homo sapiens (human) [MFN] option selected as the pathway library.

Statistical analysis

To compare the levels of candidate metabolites among samples, the 2-sided, unpaired t-test or paired t-test was used in Graph Pad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA). Principal coordinate analysis was performed with the XCMS package in R software.22 In addition, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated with the cor function and ppcor package in R software. The area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves of candidate metabolites was conducted using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The optimal cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity were determined using SPSS. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study flow and population

The entire study flow is illustrated in Fig. 1. The general characteristics of the study subjects are presented in Table 1. As in the analysis of subjects’ general characteristics, the 68 subjects were divided into control (AHI < 10, n = 21) and patient (10 ≤ AHI, n = 47) groups based on the AHI. There were no significant differences in age or BMI between the two groups. Most of the PSG parameters related to apnea and hypopnea were different between the control and patient groups. We analyzed raw MS data files using XCMS and Compound Discoverer 2.1; both software programs jointly identified the following three metabolites (Fig. 1B): 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-hydroxyl-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine (PHOOA-PC), 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-keto-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine (KPOO-PC), and 9-nitrooleate (Supplementary Table S1). The flow of the metabolite set enrichment analysis (MSEA) is illustrated in Fig. 1C.

Table 1. Demographic and sleep characteristics of participants according to the presence of OSA.

| Variables | Control (n = 21) | OSA (n = 47) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Male; Female) | ||||

| Male | 20 (95.2) | 39 (83.0) | ||

| Female | 1 (4.8) | 8 (17.0) | ||

| Age (yr) | 40.9 ± 14.1 | 47.0 ± 13.6 | 0.085 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 ± 3.1 | 26.4 ± 4.2 | 0.540 | |

| Total sleep time (min) | 428.8 ± 65.5 | 420.4 ± 53.4 | 0.685 | |

| Sleep-onset latency (min) | 7.4 ± 6.5 | 16.0 ± 24.8 | 0.147 | |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 88.0 ± 13.4 | 85.4 ± 11.3 | 0.490 | |

| AHI | 4.6 ± 3.1 | 39.4 ± 27.2 | < 0.001 | |

| Apnea index | 1.4 ± 2.1 | 19.3 ± 21.2 | < 0.001 | |

| Apnea duration (sec) | 112.4 ± 208.3 | 2,362.2 ± 3,105.9 | 0.002 | |

| Hypopnea index | 3.7 ± 2.7 | 21.6 ± 21.6 | < 0.001 | |

| Hypopnea duration (sec) | 552.8 ± 453.6 | 3,099.5 ± 2,203.6 | < 0.001 | |

| Respiratory disturbance index | 5.0 ± 3.3 | 39.7 ± 27.1 | < 0.001 | |

| Oxygen desaturation index | 2.8 ± 2.7 | 33.5 ± 29.1 | < 0.001 | |

| Snoring time (%) | 27.7 ± 17.2 | 33.9 ± 18.3 | 0.227 | |

| Respiratory arousal index | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 5.8 | 0.006 | |

| Spontaneous arousal index | 0 | 0.1 ± 0.6 | 0.524 | |

| RERA | 0.4 ± 1.3 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.301 | |

| Total arousal index | 20.4 ± 20.7 | 45.7 ± 24.1 | < 0.001 | |

| Mean oxygen saturation (%) | 96.8 ± 1.2 | 94.4 ± 3.6 | 0.007 | |

| Lowest oxygen saturation (%) | 89.8 ± 4.4 | 80.4 ± 11.3 | < 0.001 | |

Definition of OSA patient: Control, AHI < 10; patients AHI ≥ 10; Values are presented as number of patients (%) or mean ± standard deviation; 2-sided, unpaired t-test was used to compare between control and patient group.

OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; BMI, body mass index; AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; RERA, respiratory effort-related arousal.

Differentially expressed metabolites in OSA patients

Next, we compared the intensity of metabolite between the control and patient groups. In both groups, PHOOA-PC increased in the after-sleep samples (P = 0.045 for the control group; P < 0.001 for the patient group). In the after-sleep samples, PHOOA-PC levels were higher in the patient group than in the control group (P = 0.039) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Intensity comparison of identified metabolites in the OSA group.

Comparison of (A) PHOOA-PC, (B) KPOO-PC, and (C) 9-nitrooleate intensities between control and OSA in both the before-sleep and after-sleep samples. (D) PHOOA-PC, (E) KPOO-PC, and (F) 9-nitrooleate intensities according to the severity of OSA in both the before-sleep and after-sleep samples. The control group (n = 21) was defined as AHI < 10; the OSA group (n = 47) was 10 ≤ AHI in before-sleep and after-sleep groups (A-C). The OSA group was divided according to OSA severity: control (AHI < 10, n = 21); mild to moderate OSA (10 ≤ AHI < 30, n = 21); and severe OSA (30 ≤ AHI, n = 26) in before-sleep and after-sleep groups (D-F). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation with P values.

OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PHOOA-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-hydroxyl-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; KPOO-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-keto-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; AHI, apnea-hypopnea index.

The 2-sided unpaired t-test was used for comparative analyses within the before- and after-sleep sample groups, respectively (statistical significance is denoted with asterisks, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). The paired t-test was used for comparative analyses between the control and patient groups (statistical significance is denoted with daggers, †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01; †††P < 0.001).

The levels of KPOO-PC increased in the after-sleep samples of both groups (P = 0.013 for the control group; P = 0.009 for the patient group). In the before-sleep samples, KPOO-PC was lower in the patient group than in the control group (P = 0.033); however, in the after-sleep samples, KPOO-PC was higher in the patient group (P = 0.038) (Fig. 2B). The levels of 9-nitrooleate decreased in the after-sleep samples of the patient group (P = 0.006). In the after-sleep samples, 9-nitrooleate was present at higher levels in the patient group than in control group (P = 0.009) (Fig. 2C). We also compared the metabolite intensities according to OSA severity (control group: AHI < 10, n = 21; mild to moderate group: 10 ≤ AHI < 30, n = 21; severe group: AHI ≥ 30, n = 26). PHOOA-PC and 9-nitrooleate levels were higher in the severe group than in the control group in the after-sleep samples (P = 0.017 for PHOOA-PC, and P = 0.019 for 9-nitrooleate) (Fig. 2D and F). Next, we analyzed changes in the PHOOA-PC, KPOO-PC, and 9-nitrooleate intensities of paired before- and after-sleep samples. Compared to the before-sleep samples, PHOOA-PC and KPOO-PC levels increased in the after-sleep samples of all groups (control group, P = 0.045; mild to moderate group, P < 0.001; severe group, P = 0.003 for PHOOA-PC and control group, P = 0.013; mild to moderate group, P < 0.001; severe group, P = 0.028 for KPOO-PC) (Fig. 2D and E). In the mild to moderate group, 9-nitrooleate levels decreased in the after-sleep samples compared to the before-sleep samples (P = 0.009) (Fig. 2F).

Table 2 shows Pearson correlation coefficients between the three metabolites and PSG variables. In our results, only PHOOA-PC showed a correlation with AHI. However, PHOOA-PC and KPOO-PC showed correlations with several PGS parameters, including the hypopnea index, hypopnea duration, respiratory disturbance index, and snoring time.

Table 2. Correlation between metabolites and polysomnographic variables.

| Independent variables | PHOOA-PC | KPOO-PC | 9-Nitrooleate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | r | P | |

| Total sleep time (min) | 0.021 | 0.864 | 0.042 | 0.731 | 0.124 | 0.313 |

| Sleep-onset latency (min) | −0.122 | 0.326 | −0.023 | 0.855 | −0.092 | 0.456 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | −0.026 | 0.836 | −0.058 | 0.641 | 0.153 | 0.212 |

| AHI | 0.244 | 0.045 | 0.232 | 0.057 | 0.059 | 0.634 |

| Apnea index | 0.069 | 0.577 | −0.057 | 0.645 | 0.071 | 0.568 |

| Apnea duration (sec) | 0.061 | 0.630 | −0.035 | 0.781 | −0.01 | 0.937 |

| Hypopnea index | 0.283 | 0.019 | 0.373 | 0.002 | 0.089 | 0.470 |

| Hypopnea duration (sec) | 0.420 | < 0.001 | 0.296 | 0.016 | 0.185 | 0.138 |

| Respiratory disturbance index | 0.255 | 0.036 | 0.240 | 0.049 | 0.058 | 0.636 |

| Oxygen desaturation index | 0.194 | 0.113 | 0.192 | 0.117 | 0.047 | 0.703 |

| Snoring time (%) | 0.272 | 0.025 | 0.257 | 0.034 | 0.093 | 0.453 |

| Respiratory arousal index | 0.010 | 0.939 | 0.083 | 0.499 | −0.014 | 0.910 |

| Spontaneous arousal index | −0.101 | 0.412 | −0.015 | 0.902 | −0.046 | 0.712 |

| RERA | 0.007 | 0.956 | −0.054 | 0.665 | −0.056 | 0.650 |

| Total arousal index | 0.180 | 0.142 | 0.201 | 0.100 | 0.010 | 0.938 |

| Mean oxygen saturation (%) | −0.120 | 0.331 | −0.087 | 0.479 | 0.035 | 0.780 |

| Lowest oxygen saturation (%) | −0.189 | 0.122 | −0.121 | 0.327 | −0.057 | 0.643 |

Pearson correlation method was used to analyzed correlation coefficient.

PHOOA-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-hydroxyl-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; KPOO-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-keto-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; RERA, respiratory effort-related arousal.

Diagnostic potential and predictive values of salivary biomarkers

Next, we analyzed the diagnostic potential of the 3 metabolites. As a result of ROC analysis for OSA diagnosis prediction, the sensitivity and specificity were 61.7% and 62.9% for PHOOA-PC, 68.1% and 66.7% for KPOO-PC, and 63.8% and 61.9% for 9-nitrooleate, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Diagnostic significance of PHOOA-PC, KPOO-PC, 9-nitrooleate and combinations of 3 metabolites.

| Metabolites | Cutoff value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC (P) | PPV % | NPV % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHOOA-PC | 8,473,946 | 2.62 (0.91–7.55) | 0.075 | 61.7 | 62.9 | 0.677 (0.021) | 78.38 | 41.94 |

| KPOO-PC | 625,615 | 4.27 (1.43–12.76) | 0.009 | 68.1 | 66.7 | 0.720 (0.004) | 82.05 | 48.28 |

| 9-Nitrooleate | 281,983 | 2.88 (0.99–8.30) | 0.052 | 61.7 | 61.9 | 0.683 (0.017) | 78.95 | 43.33 |

| PHOOA-PC + KPOO-PC | 0.60 | 4.72 (1.57–14.19) | 0.006 | 70.2 | 71.4 | 0.716 (0.005) | 84.61 | 51.72 |

| KPOO-PC + 9-Nitrooleate | 0.59 | 4.74 (1.58–14.21) | 0.005 | 70.2 | 71.4 | 0.743 (0.001) | 84.61 | 51.72 |

| PHOOA-PC + 9-Nitrooleate | 0.60 | 3.14 (1.09–9.13) | 0.035 | 66.0 | 66.7 | 0.706 (0.007) | 81.58 | 46.67 |

| All 3 metabolites | 0.58 | 6.55 (2.11–20.28) | 0.001 | 74.5 | 76.2 | 0.758 (0.001) | 87.5 | 57.14 |

PHOOA-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-hydroxyl-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; KPOO-PC, 1-palmitoyl-2-(5-keto-8-oxo-6-octenoyl)-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; CI, confidence interval; AUC, area under the curve; PPV, positive predictive value (probability that the disease is present when the test is positive); NPV, negative predictive value (probability that the disease is not present when the test is negative).

Combinations of the three salivary metabolites were analyzed using a logistic regression model with stepwise selection. When pairs (i.e., combinations of two of the three metabolites) were analyzed, the resulting three ROC curves generated AUCs ranging from 0.706 to 0.743 (Table 3), and the full combination of PHOOA-PC, KPOO-PC, and 9-nitrooleate yielded the highest AUC (0.758), with a sensitivity of 74.5% and a specificity of 76.2% (Table 3). The ROC curves analyzed from before-sleep samples provided AUCs ranging from 0.384 to 0.687 (Supplementary Fig. S1).

To estimate the odds ratio of OSA in relation to the cutoff values of the three metabolites, we conducted logistic regression analysis (Table 3). Subjects above the cutoff value of KPOO-PC (cutoff = 625,615) were 4.27 times more likely to have OSA than subjects below the cutoff value.

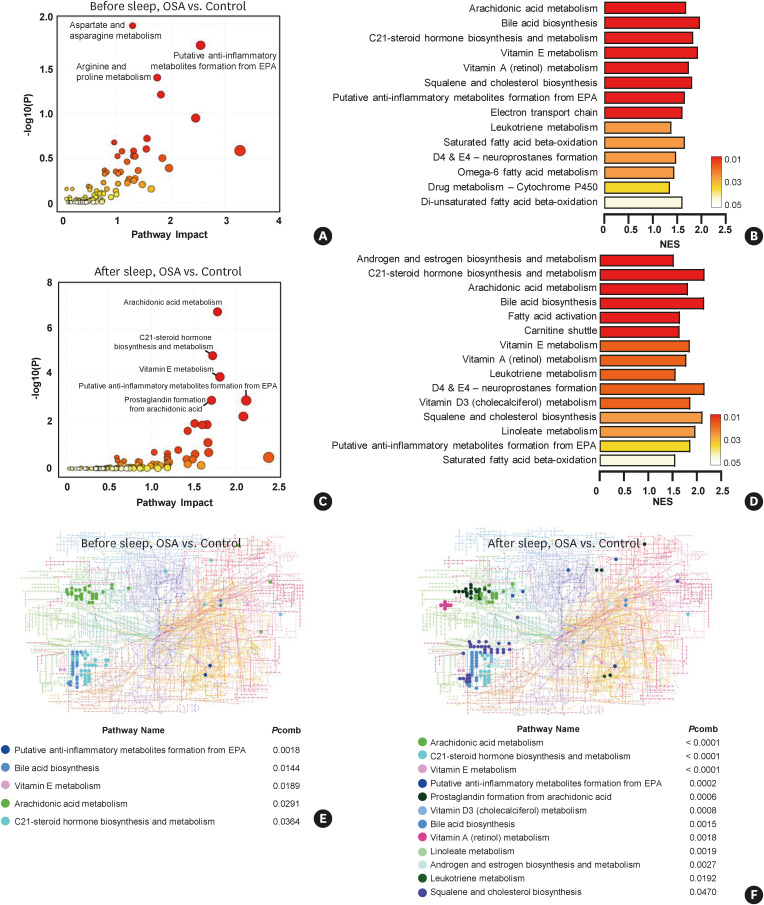

Metabolite set enrichment analysis in OSA patients compared to controls

MSEA of the differentially expressed metabolites showed altered metabolic pathways in OSA patients. The pathway analysis was conducted using the ‘Functional analysis – MS peaks’ module of the MetaboAnalyst website. The aim of this option is to leverage the power of known metabolic pathways to gain functional insights and biological meaning directly from m/z features. For the input data, m/z peaks, P values, and t-scores obtained from the XCMS results were used.

We first checked the enriched pathway changes in saliva samples obtained before and after sleep in the OSA group compared to the control group. In total, 18,935 m/z peaks identified in the before-sleep samples from both the control and OSA groups were analyzed. The aspartate and asparagine metabolism, putative anti-inflammatory metabolites formation, and arginine and proline metabolism pathways were determined as significant pathways by the mummichog algorithm (Fig. 3A). Fourteen pathways were determined as enriched pathways by the GSEA algorithm (Fig. 3B). Next, 21,717 m/z peaks identified in the after-sleep samples from the control and OSA groups were analyzed, and 10 pathways were determined to be enriched by mummichog algorithm (Fig. 3C). Fifteen pathways were determined to be enriched by the GSEA algorithm (Fig. 3D). A KEGG global metabolic network analysis was performed to map significant metabolites selected by combining the mummichog and GSEA algorithms. Four pathways were significantly altered in the before-sleep samples from the OSA group (Fig. 3E), and twelve pathways were altered in the after-sleep OSA samples (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3. Analysis of enriched metabolic pathways in OSA group.

Significantly upregulated pathways were analyzed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0. Pathway analysis was performed between the before-sleep samples from the OSA and the control groups using (A) the mummichog algorithm, or (B) the GSEA algorithm. After-sleep samples from OSA were compared to control subjects using (C) the mummichog algorithm (figure shows the top 5 pathways), or (D) the GSEA algorithm. Upregulated metabolites were mapped on the KEGG global network map. Solid circles denote significant metabolites in (E) before-sleep samples, and (F) after-sleep samples from OSA group compared to the control group. Combined P values (combination of mummichog and GSEA P values) were calculated by the Fisher combined probability test.

OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; NES, normalized enrichment score; Pcomb, combined P value.

As depicted in the KEGG global network map, lipid metabolism (e.g., arachidonic acid metabolism, prostaglandin formation from arachidonic acid, linoleate metabolism, and leukotriene metabolism) pathways were significantly increased in after-sleep samples compared to the before-sleep samples from the OSA group. A full list of positively or negatively enriched metabolic pathways with all information is provided in the Supplementary Table S2.

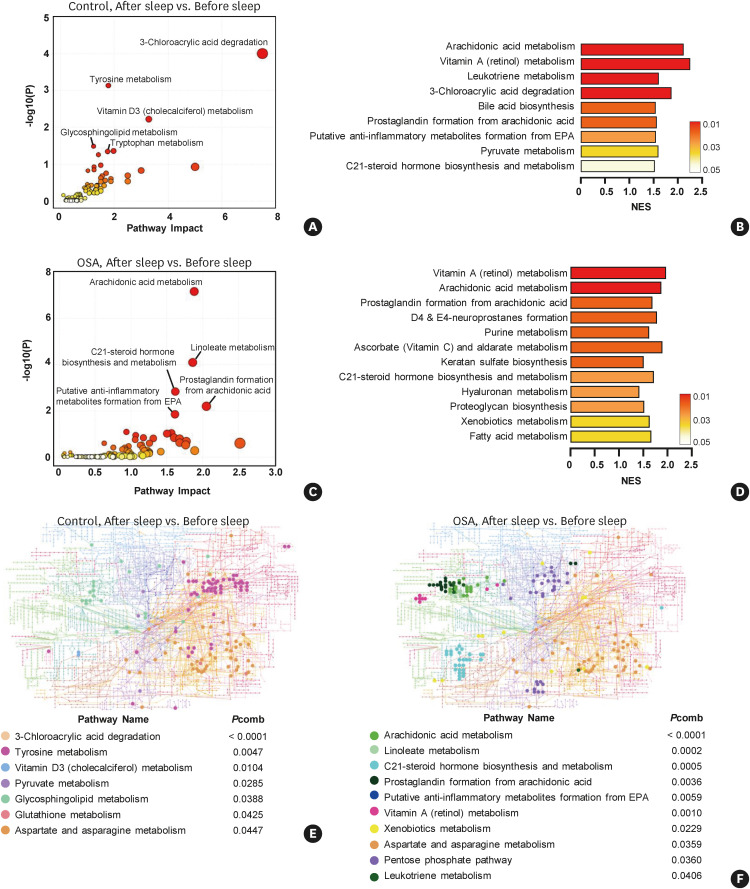

Metabolite enrichment analysis in the after-sleep samples

Next, we analyzed the enriched pathways in the after-sleep samples from the control and OSA groups, respectively. In total, 19,601 m/z peaks were used in the time-dependent analysis of the control group. Four pathways were determined to be significant by the mummichog algorithm (Fig. 4A), while nine pathways were determined to be altered according to the GSEA algorithm (Fig. 4B). Next, 24,436 m/z peaks were used in the time-dependent analysis of the OSA group. Five enriched pathways were significantly altered by the mummichog algorithm (Fig. 4C), and 12 pathways were determined to be altered according to the GSEA algorithm (Fig. 4D) in the after-sleep samples from the OSA group.

Fig. 4. Analysis of enriched metabolic pathways in the after-sleep samples from the control and OSA groups.

Pathway analysis was performed between paired samples. In the control group, altered pathways in the after-sleep samples compared to the before-sleep samples were analyzed using (A) the mummichog, or (B) the GSEA algorithm. In the OSA group, altered pathways in the after-sleep samples compared to the before-sleep samples were analyzed using (C) the mummichog, or (D) the GSEA algorithm. Upregulated metabolites were mapped on the KEGG global network map. Solid circles denote significant metabolites in the after-sleep samples from (E). the control group, or (F) OSA group. Combined P values (combination of mummichog and GSEA P values) were calculated by the Fisher combined probability test.

OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; NES, normalized enrichment score; Pcomb, combined P value.

A KEGG global metabolic network analysis was performed to map the significant metabolites selected by the combined P value. Seven and 10 pathways were significantly enriched in after-sleep samples from the control (Fig. 4E) and OSA (Fig. 4F) groups, respectively. Similar to the KEGG network analysis results in Fig. 4, the lipid metabolism pathway was clearly enriched in the after-sleep samples from OSA patients compared to the control group. A full list of positively or negatively enriched metabolic pathways with all information is provided in the Supplementary Table S2.

Measurement of the surface tension of saliva

Subsequent surface tension analysis of saliva samples was performed with 50 patient samples, excluding 18 that had insufficient sample volume either before or after sleep (Fig. 1A). Before measurement of patients’ saliva samples, validation of the pendant drop method using high purity deionized (DI) water (up to 18.3 MΩ) was performed. The surface tension value was calculated through the Young-Laplace equation based on the pendant drop method, and for DI water, the value of 71.9 mN/m was consistent with that reported in the literature (Fig. 5A and B).23

Fig. 5. Decreased surface tension of saliva in the after-sleep samples of the OSA group.

(A) Geometry of the pendant drop for the calculation of surface tension. (B) Validation check of the pendant drop model theory with deionized water (up to 18.3 MΩ). (C) Measured surface tension of patients’ saliva before and after sleep. (D) Comparison of the surface tension of saliva samples between the control and OSA groups in both the before-sleep and after-sleep samples. The control group (n = 14) was defined as AHI < 10; the OSA group (n = 36) was 10 ≤ AHI in before-sleep and after-sleep groups.

OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; DI, deionized; Ctrl, control group; n.s., not significant.

†Denotes P < 0.05 between the indicated groups by the paired t-test.

Fig. 5C shows an example of the measurement of the surface tension of a patient’s saliva, and it was observed that the surface tension of the after-sleep saliva was lower than that of before-sleep saliva (31.9 mN/m vs. 37.5 mN/m). The overall mean values of salivary surface tension were 45.5 mN/m (range: 32.5–61.4 mN/m, n = 50) for before-sleep samples and 43.5 mN/m (range: 25.0–56.8, n = 50) for after-sleep samples, respectively, corresponding to the average measurement range reported in the existing literature (38–56 mN/m).24,25,26 However, in the OSA group (10 ≤ AHI, n = 36), the mean surface tension of saliva showed a statistically significant decrease by3.39% in after-sleep samples, compared to before-sleep (P = 0.018, 42.7 ± 8.1 mN/m vs. 44.2 ± 7.8 mN/m), while in the control group (AHI < 10, n = 14), no significant change in surface tension of saliva was observed between before- and after-sleep samples (P = 0.558, 46.4 ± 7.3 mN/m vs. 45.5 ± 7.9 mN/m) (Fig. 5D). Next, we compared the correlation between the relative intensities of the three metabolites selected in the previous (Fig. 2) and surface tension of saliva across the control and OSA groups. Both PHOOA-PC and 9-nitrooleate levels showed negative correlations with the surface tension of saliva in the before-sleep and after-sleep samples (Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2E). However, the surface tension of saliva showed a positive correlation with KPOO-PC in the before-sleep samples; in contrast, the surface tension showed a negative correlation with KPOO-PC in the after-sleep samples (Supplementary Fig. S2C).

We also analyzed the correlations between changes in surface tension and the three metabolites together. The changes in PHOOA-PC and 9-nitrooleate between before- and after-sleep saliva samples were negatively correlated with those in the surface tension of saliva (Supplementary Fig. S2B and S2F). However, the changes in KPOO-PC levels between before- and after-sleep saliva samples did not show a statistically significant correlation with those in the surface tension of saliva (Supplementary Fig. S2D).

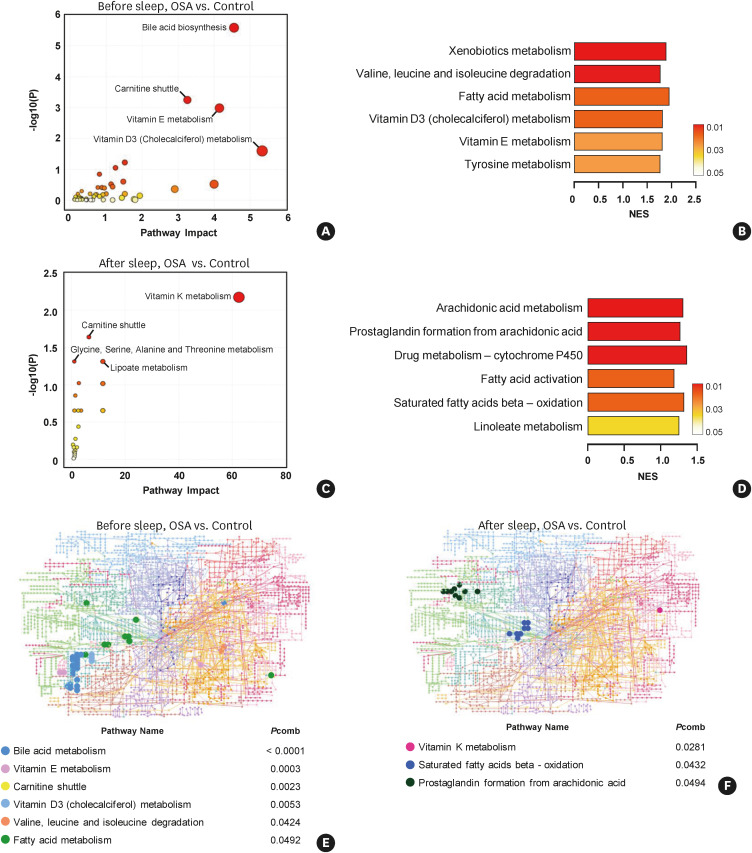

The arachidonic acid metabolism pathway was significantly upregulated in saliva from OSA patients

To analyze the upregulated pathways related to changes in surface tension, we performed MSEA for the metabolites identified from 50 patients (total identified metabolites from the before-sleep and after-sleep samples: 18,935 and 21,717 respectively). Among all identified m/z peaks, we selected metabolites according to the correlation with saliva surface tension (r > 0.7 for positive correlations; r < −0.7 for negative correlations with P values < 0.05). In total, 6,522 peaks correlated with surface tension were used to determine the metabolic pathways that were enriched in OSA patients in before-sleep samples compared to normal. Four metabolic pathways, including the bile acid biosynthesis pathway, were enriched in the before-sleep samples from OSA patients (Fig. 6A). The GSEA algorithm identified six metabolic pathways as being significantly enriched in the before-sleep samples from OSA patients (Fig. 6B). In total, 5,807 m/z peaks identified in the after-sleep samples from OSA patients, were analyzed using the mummichog (Fig. 6C) or GSEA (Fig. 6D) algorithm. The arachidonic acid metabolism and prostaglandin formation from arachidonic acid pathways were highly enriched in the after-sleep samples from OSA patients (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6. Altered metabolic patterns of before- and after-sleep saliva samples in the OSA group.

Pathway analysis was performed between before-sleep samples from the OSA and control groups using (A) the mummichog algorithm, or (B) the GSEA algorithm. After-sleep samples from the OSA group was compared to the control subjects using (C) the mummichog, or (D) the GSEA algorithm. Upregulated metabolites were mapped on the KEGG global network map. Solid circles denote significant metabolites in (E) the before-sleep samples, and (F) the after-sleep samples from the OSA group compared to the control group. Combined P values (combination of mummichog and GSEA P values) were calculated by the Fisher combined probability test. Highly correlated (r > 0.7 for positive correlations; r < −0.7 for negative correlations, with P values < 0.05) metabolites were used in MSEA. OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; NES, normalized enrichment score; Pcomb, combined P value.

DISCUSSION

Our untargeted metabolomic analysis suggested PHOOA-PC, KPOO-PC, and 9-nitrooleate as candidate biomarkers for oxidative stress in the OSA patients. PHOOA-PC and its 5-hydroxy keto-analogue KPOO-PC are classified as oxidatively truncated phosphatidylcholines (PCs) generated by free radical oxidation of arachidonic acid.27 9-Nitrooleate is one of 2 regioisomers of nitrooleate, which is formed by nitration, a patho-biochemical process mediated by reactive nitrogen oxides derived from the oxidation of NO by oxygen or superoxide, from oleic acid (NO2-OA).28 Therefore, it would be reasonable to infer that these increased PHOOA-PC, KPOO-PC and 9-nitrooleate levels may have been due to oxidative stress, which is frequently increased in patients with OSA. It is well known that OSA patients are exposed to oxidative stress and an inflammatory environment due to a lack of oxygen, which leads the unsaturated fatty acid chains of cellular phospholipids to be oxidized and modified. This process produces structurally very diverse oxidized phospholipids (OxPLs). It has recently been reported that OxPLs are effector molecules that elicit a biological response, not just byproducts of a pathologic condition.29,30 OxPLs stimulate airway smooth muscle cells to secrete pro-inflammatory molecules, including IL-6, IL-8, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, and diverse oxylipins.31 Since PHOOA-PC and KPOO-PC are types of OxPLs,32,33 they may also act as effectors in the inflammatory conditions reported in OSA. Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate their precise roles under conditions of oxidative stress or inflammation in OSA.

OSA patients have been reported to be at a higher risk of hypertension and CVD, which develop through vascular endothelial dysfunction.34 Nitrated fatty acids, such as 9-nitrooleate (NO2-OA) are formed through NO-dependent oxidation, and it is well known that NO2-OA has a protective function against vascular diseases, thought to be through a PPAR-mediated or non-PPAR pathway.35,36 NO2-OA has also been reported to prevent hypertension as an antagonist of angiotensin 2 receptor type 1,37,38 or to prevent pulmonary vascular endothelial dysfunction due to hypoxia.39 Collectively, we speculated that the increased levels of 9-nitrooleate in our findings might relate to cardiovascular protection against oxidative stress in OSA patients, but this possibility should be further studied.

Intermittent hypoxia is a hallmark of OSA and leads to systemic inflammation, although the exact mechanism linking OSA with the inflammatory cascade remains unclear.40,41 Several studies have reported inflammation-related proteins that are significantly altered in OSA patients.7,8,10,42 In addition, most studies seem to be insufficient to characterize OSA accompanying systemic metabolic changes by targeted analysis of proteins or transcripts.43,44 Therefore, studies on overall changes at the metabolite level are still needed. To achieve this goal, we performed MSEA. The enriched pathways were slightly different when the mummichog algorithm was used. However, when the 2 algorithms were integrated and analyzed, it was confirmed that arachidonic acid-related metabolism was enriched in the after-sleep samples from OSA patients, regardless of which analysis combination was used. Arachidonic acid is a substrate of oxygenases, such as cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, and cytochrome P450, which form inflammatory bioactive lipids or eicosanoids, prostanoids, or leukotrienes.45 Given that OSA evokes systemic inflammation, it is not surprising that arachidonic acid-related metabolites accumulate in OSA patients. The above results are also consistent with a previous report suggesting increased 5-HETE and 5-oxoETE as biomarkers of OSA patients.46

Upper airway patency is known to be affected by the surface tension of the UALL, which is mainly composed of saliva. Kirkness and colleagues47 have reported that the surface tension of human saliva and exogenous surfactants could regulate upper airway patency by decreasing the adherence between closed airway walls. To study the lowering effect of surface tension in saliva on upper airway patency, several studies analyzed Exosurf, a dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC)-based synthetic substance, or endogenous DPPC.25,47 PC is the main component (up to 80%) of pulmonary surfactant that mediates the reduction of surface tension. In addition, unsaturated phosphatidylcholines (USPC) made up to 21% of all PCs.48 Since PHOOA-PC and KPOO-PC are USPCs, we analyzed the correlations between PHOOA-PC, KPOO-PC, and 9-nitrooleate with surface tension in paired saliva samples, and confirmed that all of these candidates from the after-sleep samples showed negative correlations with surface tension. We suggest that these three metabolites could serve as endogenous surface-active agents to improve upper airway patency during sleep in OSA. Previous studies have shown that the dominant surface-active phospholipid species are USPCs, not saturated PCs, at non-lung sites.49,50 Thus, further investigation is needed to demonstrate how these metabolites lower the surface tension of saliva in the upper airway.

Since the candidate metabolites showed correlations with surface tension, we additionally performed MSEA using only the metabolites that showed significant correlations with the surface tension before or after sleep, respectively. Interestingly, the arachidonic acid-related pathways, including arachidonic acid metabolism (Fig. 6D) and prostaglandin formation from arachidonic acid (Fig. 6F), were enriched in the after-sleep samples from OSA patients. In previous studies, modulating surface tension was suggested as a method to reduce symptoms in OSA patients by providing force to widen an obstructive airway. Therefore, these results provide therapeutic insights into the surface-active role of arachidonic acid in biological fluids.

Increased oral breathing is characteristic of OSA patients and inevitably results in evaporation of saliva. Since there is no standardized internal control for salivary metabolite analysis, we suspected that a likely reason for the increase in PHOOA-PC and KPOO-PC only in the after-sleep samples was evaporation of saliva. However, the intensity of 9-nitrooleate decreased between the before- and after-sleep samples of OSA patients (Fig. 2C), which, therefore, suggests that our observations cannot be explained as the result of oral breathing, a characteristic of OSA. Nonetheless, finding a standardized internal standard that can be used for analysis will be necessary for further salivary metabolite studies.

Some limitations of our study need to be addressed. First, AHI less than 5 is generally classified as a control group, but in this study, disease groups were classified based on AHI 10 or higher so that metabolic changes caused by OSA could be sufficiently reflected. Second, we did not consider factors which could affect metabolites levels including smoking, nutrient intake and genetic backgrounds. These points should be further investigated in future follow-up studies.

In conclusion, untargeted metabolomics profiling identified diverse metabolites associated with OSA. In addition, increased metabolites contribute to upper airway patency by reducing the salivary surface tension in OSA. From a therapeutic perspective, PHOOA-PC and 9-nitrooleate might be potential surface-active drugs to improve the patency of the obstructed upper airway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

H.W.S appreciate the support by the National Research Foundation of Korea (No. 2020R1A4A2002903 and 2022R1A2C2006075). S.A. and W.J. appreciate the support by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2016R1A3B1908660).

Footnotes

Disclosure: There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Identified human derived metabolite candidates for OSA biomarkers

Results of the mummichog pathway, GSEA enrichment, and integrated pathway enrichment analysis

ROC curve of a single metabolites and their combinations in before-sleep samples.

Correlation analysis between the surface tension of saliva and PHOOA-PC, KPOO-PC and 9-nitrooleate.

References

- 1.Lévy P, Kohler M, McNicholas WT, Barbé F, McEvoy RD, Somers VK, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15015. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoon DW, Shin HW. Sleep tests in the non-contact era of the COVID-19 pandemic: home sleep tests versus in-laboratory polysomnography. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;13:318–319. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.01599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Luca Canto G, Pachêco-Pereira C, Aydinoz S, Major PW, Flores-Mir C, Gozal D. Diagnostic capability of biological markers in assessment of obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:27–36. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maeder MT, Mueller C, Schoch OD, Ammann P, Rickli H. Biomarkers of cardiovascular stress in obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;460:152–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montesi SB, Bajwa EK, Malhotra A. Biomarkers of sleep apnea. Chest. 2012;142:239–245. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirotsu C, Tufik S, Guindalini C, Mazzotti DR, Bittencourt LR, Andersen ML. Association between uric acid levels and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in a large epidemiological sample. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papanas N, Steiropoulos P, Nena E, Tzouvelekis A, Maltezos E, Trakada G, et al. HbA1c is associated with severity of obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome in nondiabetic men. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:751–756. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s7057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Punjabi NM, Beamer BA. C-reactive protein is associated with sleep disordered breathing independent of adiposity. Sleep. 2007;30:29–34. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winnicki M, Shamsuzzaman A, Lanfranchi P, Accurso V, Olson E, Davison D, et al. Erythropoietin and obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:783–786. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoe T, Minoguchi K, Matsuo H, Oda N, Minoguchi H, Yoshino G, et al. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome are decreased by nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Circulation. 2003;107:1129–1134. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052627.99976.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrett JR, Ekström Jr, Anderson LC. Glandular mechanisms of salivary secretion. Vol. 10. Basel: Karger; 1998. Frontiers of oral biology. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyvärinen E, Savolainen M, Mikkonen JJ, Kullaa AM. Salivary metabolomics for diagnosis and monitoring diseases: challenges and possibilities. Metabolites. 2021;11:587. doi: 10.3390/metabo11090587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam JC, Kairaitis K, Verma M, Wheatley JR, Amis TC. Saliva production and surface tension: influences on patency of the passive upper airway. J Physiol. 2008;586:5537–5547. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.159822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wishart DS. Emerging applications of metabolomics in drug discovery and precision medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:473–484. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeung PK. Metabolomics and biomarkers for drug discovery. Metabolites. 2018;8:11. doi: 10.3390/metabo8010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. Innovation: metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, Harding SM, Lloyd RM, Quan SF, et al. AASM scoring manual updates for 2017 (version 2.4) J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:665–666. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tautenhahn R, Patti GJ, Rinehart D, Siuzdak G. XCMS Online: a web-based platform to process untargeted metabolomic data. Anal Chem. 2012;84:5035–5039. doi: 10.1021/ac300698c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao L, Wang J, Page D, Asthana S, Zetterberg H, Carlsson C, et al. Comparative evaluation of ms-based metabolomics software and its application to preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9291. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27031-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarez NJ, Walker LM, Anna SL. A non-gradient based algorithm for the determination of surface tension from a pendant drop: application to low Bond number drop shapes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;333:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chong J, Soufan O, Li C, Caraus I, Li S, Bourque G, et al. MetaboAnalyst 4.0: towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W486–W494. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanai Y, Shimono K, Matsumura K, Vachani A, Albelda S, Yamazaki K, et al. Urinary volatile compounds as biomarkers for lung cancer. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2012;76:679–684. doi: 10.1271/bbb.110760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pallas N, Harrison Y. An automated drop shape apparatus and the surface tension of pure water. Colloids Surf. 1990;43:169–194. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foglio-Bonda PL, Laguini E, Davoli C, Pattarino F, Foglio-Bonda A. Evaluation of salivary surface tension in a cohort of young healthy adults. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:1191–1195. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201803_14457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawai M, Kirkness JP, Yamamura S, Imaizumi K, Yoshimine H, Oi K, et al. Increased phosphatidylcholine concentration in saliva reduces surface tension and improves airway patency in obstructive sleep apnoea. J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40:758–766. doi: 10.1111/joor.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazakov VN, Udod AA, Zinkovych II, Fainerman VB, Miller R. Dynamic surface tension of saliva: general relationships and application in medical diagnostics. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009;74:457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fruhwirth GO, Loidl A, Hermetter A. Oxidized phospholipids: from molecular properties to disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:718–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koppenol WH. The basic chemistry of nitrogen monoxide and peroxynitrite. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matt U, Sharif O, Martins R, Knapp S. Accumulating evidence for a role of oxidized phospholipids in infectious diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:1059–1071. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1780-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berliner JA, Watson AD. A role for oxidized phospholipids in atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:9–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penn RB. Honing in on the effectors of oxidative stress in the asthmatic lung: oxidised phosphatidylcholines. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2003736. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03736-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bochkov VN, Oskolkova OV, Birukov KG, Levonen AL, Binder CJ, Stöckl J. Generation and biological activities of oxidized phospholipids. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1009–1059. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stemmer U, Hermetter A. Protein modification by aldehydophospholipids and its functional consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1818:2436–2445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzaga C, Bertolami A, Bertolami M, Amodeo C, Calhoun D. Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29:705–712. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schopfer FJ, Lin Y, Baker PR, Cui T, Garcia-Barrio M, Zhang J, et al. Nitrolinoleic acid: an endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2340–2345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408384102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang G, Ji Y, Li Z, Han X, Guo N, Song Q, et al. Nitro-oleic acid downregulates lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 expression via the p42/p44 MAPK and NFκB pathways. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4905. doi: 10.1038/srep04905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Villacorta L, Chang L, Fan Z, Hamblin M, Zhu T, et al. Nitro-oleic acid inhibits angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107:540–548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudolph TK, Ravekes T, Klinke A, Friedrichs K, Mollenhauer M, Pekarova M, et al. Nitrated fatty acids suppress angiotensin II-mediated fibrotic remodelling and atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;109:174–184. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koudelka A, Ambrozova G, Klinke A, Fidlerova T, Martiskova H, Kuchta R, et al. Nitro-oleic acid prevents hypoxia- and asymmetric dimethylarginine-induced pulmonary endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2016;30:579–586. doi: 10.1007/s10557-016-6700-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garvey JF, Taylor CT, McNicholas WT. Cardiovascular disease in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: the role of intermittent hypoxia and inflammation. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1195–1205. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00111208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–2041. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho K, Yoon DW, Lee M, So D, Hong IH, Rhee CS, et al. Urinary metabolomic signatures in obstructive sleep apnea through targeted metabolomic analysis: a pilot study. Metabolomics. 2017;13:88. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thimgan MS, Toedebusch C, McLeland J, Duntley SP, Shaw PJ. Excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with changes in salivary inflammatory genes transcripts. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:539627. doi: 10.1155/2015/539627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghiciuc CM, Dima-Cozma LC, Bercea RM, Lupusoru CE, Mihaescu T, Cozma S, et al. Imbalance in the diurnal salivary testosterone/cortisol ratio in men with severe obstructive sleep apnea: an observational study. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed) 2016;82:529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sprecher H. The roles of anabolic and catabolic reactions in the synthesis and recycling of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;67:79–83. doi: 10.1054/plef.2002.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin HW, Cho K, Rhee CS, Hong IH, Cho SH, Kim SW, et al. Urine 5-eicosatetraenoic acids as diagnostic markers for obstructive sleep apnea. Antioxidants. 2021;10:1242. doi: 10.3390/antiox10081242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirkness JP, Madronio M, Stavrinou R, Wheatley JR, Amis TC. Relationship between surface tension of upper airway lining liquid and upper airway collapsibility during sleep in obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2003;95:1761–1766. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00488.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agassandian M, Mallampalli RK. Surfactant phospholipid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:612–625. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen Y, Crawford RW, Oloyede A. Unsaturated phosphatidylcholines lining on the surface of cartilage and its possible physiological roles. J Orthop Surg. 2007;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paananen R, Postle AD, Clark G, Glumoff V, Hallman M. Eustachian tube surfactant is different from alveolar surfactant: determination of phospholipid composition of porcine eustachian tube lavage fluid. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Identified human derived metabolite candidates for OSA biomarkers

Results of the mummichog pathway, GSEA enrichment, and integrated pathway enrichment analysis

ROC curve of a single metabolites and their combinations in before-sleep samples.

Correlation analysis between the surface tension of saliva and PHOOA-PC, KPOO-PC and 9-nitrooleate.