Abstract

5-Fluorouracil and 5-fluorouracil-based prodrugs have been used clinically for decades to treat cancer. Their anticancer effects are most prominently ascribed to inhibition of thymidylate synthase (TS) by metabolite 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate (FdUMP). However, 5-fluorouracil and FdUMP are subject to numerous unfavorable metabolic events that can drive undesired systemic toxicity. Our previous research on antiviral nucleotides suggested that substitution at the nucleoside 5′-carbon imposes conformational restrictions on the corresponding nucleoside monophosphates, rendering them poor substrates for productive intracellular conversion to viral polymerase-inhibiting triphosphate metabolites. Accordingly, we hypothesized that 5′-substituted analogs of FdUMP, which is uniquely active at the monophosphate stage, would inhibit TS while preventing undesirable metabolism. Free energy perturbation-derived relative binding energy calculations suggested that 5′(R)-CH3 and 5′(S)-CF3 FdUMP analogs would maintain TS potency. Herein, we report our computational design strategy, synthesis of 5′-substituted FdUMP analogs, and pharmacological assessment of TS inhibitory activity.

Keywords: 5-fluorouracil, FdUMP, nucleoside, nucleotide, thymidylate synthase, anticancer

Introduction

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is a pyrimidine-based antimetabolite approved in 1962 for treating various malignancies, including colorectal, breast, pancreatic, stomach, esophageal, and cervical cancers.1−4 It exerts its anticancer activity most notably through inhibition of the thymidylate synthase (TS) enzyme via its active metabolite 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate (FdUMP, Figure 1).5−7 Under physiological conditions, the TS enzyme plays an essential role in catalyzing the de novo synthesis of deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP) from deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) in the presence of the 5,10-CH2-tetrahydrofolate (mTHF) cofactor and a TS active site cysteine residue.8,9 FdUMP covalently inhibits this catalytic cycle, leading to the depletion of dTMP levels, DNA damage, and cell death.10−12 5-FU additionally generates two other cytotoxic metabolites, 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate (FdUTP) and 5-fluorouridine 5′-triphosphate (FUTP), which incorporate into growing oligonucleotides as substrates for DNA and RNA polymerases, respectively (Figure 1).1

Figure 1.

Metabolic activation of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) to 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate (FdUMP, TS inhibitor), 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate (FdUTP, DNA polymerase substrate), and 5-fluorouridine 5′-triphosphate (FUTP, RNA polymerase substrate). TP, thymidine phosphorylase; TK, thymidine kinase; OPRT, orotate phosphoribosyl transferase; PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate; RNR, ribonucleotide reductase; TS, thymidylate synthase (PDB ID 1HZW).

Although 5-FU effectively treats a fraction of cancer patients with these unique mechanisms of action, its widespread clinical utility is significantly limited by catabolic degradation in the liver (up to 85%) by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) as well as by poor oral bioavailability.13,14 To circumvent the undesired metabolic degradation and improve systemic exposure, several 5-FU prodrugs, such as capecitabine, doxifluridine, floxuridine, tegafur, and carmofur, have been developed and used in the clinic.2,14−17 However, the productive metabolism of these prodrugs to FdUMP proceeds via the generation of 5-FU, subsequently resulting in DPD-mediated degradation and systemic toxicity, among other undesirable consequences (Figure 2). Alternatively, the 5-FU prodrug NUC-3373 (currently in Phase 1b/2a clinical trials for the treatment of colorectal malignancies) releases the active FdUMP metabolite without generating 5-FU (Figure 2).18−21 While this approach offers several potential advantages over 5-FU and approved prodrugs thereof, NUC-3373 requires intravenous administration and is still responsible for the production of FdUTP and FUTP, which indiscriminately target both healthy tissue and tumor tissue.

Figure 2.

Early prodrug strategies rely on release of 5-FU to generate FdUMP, whereas other strategies (e.g., NUC-3373) generate FdUMP directly without 5-FU release.

Given the shortcomings discussed above, there is a need to develop novel analogs and/or prodrugs of FdUMP that limit the formation of promiscuous triphosphate metabolites while efficiently releasing FdUMP (or efficacious analogs thereof) and avoiding 5-FU generation. Previous results from our laboratory using cell-based hepatitis C virus (HCV) replicon assays revealed that functionalization of 2′-C-methyluridine at the 5′-carbon (i.e., 5′-CH3) significantly compromised antiviral activity of the corresponding mono- and diphosphate prodrugs (Figure 3).22 In this assay, the antiviral activity of nucleoside mono- and diphosphate prodrugs is dependent upon: (1) conversion of prodrug to the corresponding nucleoside monophosphate or diphosphate; (2) conversion of nucleoside monophosphate or diphosphate to the corresponding nucleoside triphosphate; and (3) substrate recognition by and concomitant inhibition of HCV RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP). Importantly, conversion of these prodrugs to the corresponding mono- and diphosphates relies on enzyme-mediated activation at positions relatively distal from the 5′ carbon. Therefore, the lack of antiviral activity of 5′-CH3 derivatives is much more likely to be controlled by slow conversion of mono- and diphosphate metabolites to the corresponding triphosphates and/or poor substrate recognition of these triphosphates by HCV RdRP.

Figure 3.

Repurposing the nucleoside/nucleotide 5′-functionalization strategy for FdUMP. R groups of interest include small substituents, such as CH3, CF3, etc.

While these results indicated that our 5′-functionalization strategy would clearly not be effective for nucleoside-based therapeutics requiring efficient conversion to (and target recognition of) the corresponding triphosphates, FdUMP is uniquely active at the monophosphate stage.2 Accordingly, we hypothesized that 5′-functionalized FdUMP analogs could maintain potent inhibition of TS and associated antitumor efficacy while reducing undesired side effects and systemic toxicity by limiting the generation of 5-FU and the corresponding nucleoside triphosphates (Figure 3). We report herein our approach to testing this hypothesis using a combination of molecular modeling, organic synthesis, and biochemical techniques.

Initially, molecular modeling was employed to assess whether 5′-substituted FdUMP analogs could be well accommodated within the human TS (hTS) binding pocket. Utilizing the available X-ray cocrystal structure of hTS in complex with FdUMP (PDB ID 6QXG), several FdUMP analogs featuring small 5′-substituents (Table S1) were docked (Schrödinger’s Glide-SP) into the FdUMP binding pocket. Initial binding energy calculations using Prime MM-GBSA suggested that three different substitutions, 5′(R)-CH3, 5′(S)-CHF2, and 5′(S)-CF3, would maintain TS inhibitory activity comparable to FdUMP. The predicted binding poses of FdUMP analogs featuring these substitutions also aligned very closely (Table S2) with the conformation of FdUMP cocrystallized in this pocket (PDB ID 6QXG). We further investigated relative binding free energy values using the FEP-based methodology (Desmond – D. E. Shaw research group).23,24 The resulting FEP-calculated binding energies suggested that two of these three substitutions, 5′(R)-CH3 and 5′(S)-CF3, would effectively inhibit TS function (Table S3). Consistent with these results are poor conformational alignments and poor FEP-predicted binding energies of FdUMP analogs featuring 5′(S)-CH3, 5′(CH3)2, and 5′(R)-CF3 motifs, relative to FdUMP and the 5′(R)-CH3- and 5′(S)-CF3-substituted analogs. As illustrated in Figure 4, a general observation from these computational experiments can be described: Small 5′-substituents occupying the green region of the TS catalytic site were much more likely to be tolerated compared to small 5′-substituents occupying the red region (Figure 4C). This is highlighted by the predicted stereochemical preference of hTS for 5′(R)-CH3 and 5′(S)-CF3 substituents (better relative binding energies, green region) over their epimeric counterparts, 5′(S)-CH3 and 5′(R)-CF3-bearing congeners (poorer relative binding energies, red region). This predicted diastereopreference can be ascribed to unfavorable intramolecular steric interactions as well as clashes with the catalytic Cys195, ultimately leading to an unsuitable binding conformation. In contrast, the green region highlights a small pocket that could nicely accommodate 5′-substituents, such as 5′(R)-CH3 and 5′(S)-CF3. It is also notable that, even with the preferred stereoconfiguration, larger substituents (e.g., ethyl) were disfavored (Table S3) relative to smaller substituents (e.g., methyl).

Figure 4.

Glide-SP docking poses of (A) the 5′(R)-CH3 and (B) the 5′(S)-CF3 analogs of FdUMP in hTS (PDB 6QXG) overlaid with FdUMP (in yellow) from the cocrystal structure. (C) Graphical representation of the “substitution tolerant” zone (green sphere) and the “substitution intolerant” zone (red sphere).

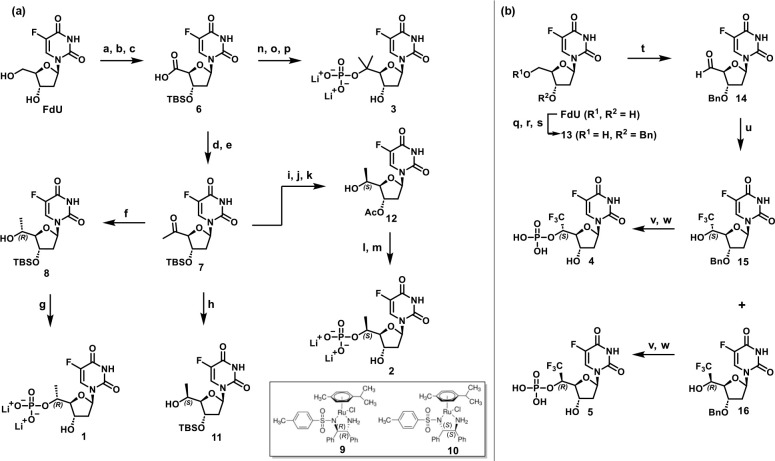

To empirically interrogate this computationally predicted stereochemical preference, we synthesized a series of FdUMP analogs functionalized with 5′(R)-CH3, 5′(S)-CH3, 5′-gem-(CH3)2, 5′(R)-CF3, or 5′(S)-CF3 motifs (Figure 5) and implemented a cell-free enzymatic assay to measure TS inhibition. Synthesis of the 5′(R/S)-CH3, 5′(R/S)-CF3, and 5′-gem-(CH3)2 analogs is presented in Scheme 1. As depicted in Scheme 1a, the two 5′-CH3 epimers were obtained using a highly diastereoselective approach involving key synthetic intermediate 7, which was prepared from commercially available 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FdU). First, FdU was converted to carboxylic acid 6 in 49% yield over three steps by (1) protecting both 3′- and 5′-FdU alcohols as TBS ethers using TBSCl, imidazole, and DMAP, (2) selectively removing the 5′-OTBS moiety using PPTS, and (3) oxidizing the resulting 5′-hydroxyl group using (diacetoxyiodo)benzene and catalytic TEMPO. Intermediate 6 was next converted to the corresponding Weinreb amide using propylphosphonic anhydride (T3P) and Weinreb’s salt. The resulting crude material was treated with methylmagnesium bromide to afford the methyl ketone 7 as a key intermediate in 71% yield over two steps. Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation (ATH) of methyl ketone 7 using Noyori’s chiral catalyst, RuCl(p-cymene)[(R,R)-Ts-DPEN] (9), furnished the 5′(R)-CH3-functionalized alcohol 8 in 75% yield and 98:2 dr.22,25,26 The absolute configuration of the 5′(R) stereocenter was determined by X-ray crystal analysis (Table S5). The secondary alcohol 8 was further converted to the monophosphate 1 over three synthetic steps in 7% overall yield. Treatment of 8 with POCl3 and pyridine afforded the corresponding monophosphate, which was then silyl-deprotected using aqueous NH4F to afford the desired product as the triethylammonium salt. Counterion exchange using Dowex-Li+ furnished the final 5′(R)-CH3 FdUMP analog 1 as the bis-lithium salt.

Figure 5.

Novel 5′-substituted FdUMP analogs 1–5.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 5′-Functionalized FdUMP Analogs.

Reagents and conditions: (a) TBSCl, imidazole, DMAP, DMF, rt, 87%; (b) PPTS, MeOH, rt, 67%; (c) TEMPO, PhI(OAc)2, MeCN/THF/H2O, rt, 85%; (d) Me(OMe)NH-HCl, T3P, EtOAc/pyridine, rt (e) MeMgBr, THF, −78°C, 71%, over 2 steps; (f) 9, HCO2Na, H2O/EtOAc, rt, 75%, 98:2 dr; (g) i, POCl3, pyridine, MeCN/H2O, 0°C to rt; ii, NH4F, H2O, rt; iii, Dowex-Li+, rt, 7%; (h) 10, HCO2Na, H2O/EtOAc, rt, 83%, 7:3 dr; (i) TBAF, THF, 0°C; (j) Ac2O, DMAP, pyridine, rt, 47% over 2 steps; (k) 10, HCO2Na, H2O/EtOAc, rt, 67%, 99:1 dr; (l) POCl3, pyridine, MeCN/H2O, 0°C to rt, 20%; (m) i, NH3(aq), H2O, rt; ii, Dowex-Li+, rt, 27% over 2 steps; (n) TMSCHN2, toluene, MeOH, rt, 86%; (o) MeMgBr, THF, 0°C to rt, 72%; (p) i, POCl3, trimethyl phosphate, 0°C to rt, 14%; ii, Dowex-Li+, rt, 12%; (q) TrCl, pyridine, μwave, 100°C, 78%; (r) NaH, BnBr, THF, rt, 67%; (s) 80% AcOH/H2O, rt, 81%; (t) DMP, DCM, rt; (u) TMSCF3, TBAF, THF, 0 °C to rt, then 0.5 N HCl, rt, silica gel chromatography (EtOAc/hexanes; 0–80%), 45% over 2 steps, 15 (S), 27%; 16 (R), 18%; (v) POCl3, pyridine, MeCN/H2O, 0°C to rt; (w) Pd(OH)2, H2, MeOH, rt (4 (S), 12%, over 2 steps; 5 (R), 6%, over 2 steps).

To synthesize the epimeric 5′(S)-CH3 FdUMP analog (2, Scheme 1), key intermediate 7 was first subjected to ATH conditions using the same metal catalyst with the opposite enantiomeric ligand, RuCl(p-cymene)[(S,S)-Ts-DPEN] (10). Although this procedure generated the 5′(S)-CH3 alcohol 11 in 83% yield, the diastereoselectivity (7:3 dr) was suboptimal. In an attempt to enhance stereoselectivity, a small set of chiral transition metal catalysts was screened,25 albeit with limited success, as each of these conditions failed to substantially improve 5′(S)-CH3 diastereoselectivity, affording either predominantly the 5′-(R)-isomer or a diastereomeric mixture (Table S4). These results suggested that a mixture of substrate-controlled and catalyst-controlled diastereopreferential reactivity is operative. We then hypothesized that reducing the steric bulk of the 3′-OH protecting group from TBS to acetyl (Ac) would allow catalyst-controlled reactivity to predominate. Accordingly, key intermediate 7 was converted in 47% yield over two steps to its 3′-O-acetyl derivative, which was then subjected to ATH using Noyori’s chiral catalyst 10 to deliver the desired 5′(S)-CH3 alcohol 12 in 67% yield and 99:1 dr. The absolute configuration of the 5′(S) stereocenter was determined by single crystal X-ray analysis (Table S5). Alcohol 12 was then converted to the corresponding monophosphate 2 using a three-step procedure in which 12 was first treated with POCl3 to give the monophosphate in 20% yield. Next, removal of the 3′-O-acetyl protecting group using aqueous NH3, followed by counterion exchange using Dowex-Li+ afforded 5′(S)-CH3 FdUMP 2 as the bis-lithium salt in 27% yield over two steps. The 5′-gem-(CH3)2 analog 3 was synthesized in three steps from the intermediate 6. The acid 6 was first converted to its methyl ester in 86% using TMSCHN2, followed by Grignard methylation using methylmagnesium bromide to give the tertiary alcohol in 72% yield. Subsequent phosphorylation conditions involving POCl3 additionally facilitated contaminant TBS deprotection to give the monophosphate in 14%. Counterion exchange using Dowex-Li+ afforded the 5′-gem-(CH3)2 FdUMP 3 in 12% isolated yield.

Synthesis of 5′(R)-CF3 and 5′(S)-CF3 substituted FdUMP analogs are described in Scheme 1b. First, the FdU 3′-OH group was protected as the corresponding benzyl ether 13 using a three-step protocol involving: (1) protection of the 5′-OH group as a trityl ether in 78% yield using trityl chloride in pyridine under MW irradiation at 100 °C; (2) protection of the 3′-OH as the corresponding benzyl ether in 67% yield using benzyl bromide and sodium hydride; and (3) removal of the trityl group using 80% aqueous acetic acid to afford intermediate 13 in 81% yield (42% yield over 3 steps). Next, alcohol 13 was oxidized to aldehyde 14 using DMP. The resulting crude material was then treated with Ruppert–Prakash’s reagent (TMSCF3) and catalytic TBAF to furnish a diastereomeric mixture of 5′-CF3-substituted alcohols (15 and 16) in 45% yield over two steps.27−29 Fortunately, this diastereomeric mixture could be cleanly resolved using silica gel column chromatography to deliver 5′(S)-CF3 (15, 27% yield) and 5′(R)-CF3 (16, 18% yield) derivatives, respectively. The absolute stereochemical assignment was determined using X-ray crystallography, indicating that alcohol 15 featured the 5′(S)-CF3 motif (Table S5). These intermediate alcohols were further converted to the corresponding monophosphates in two steps: (1) treatment of 15 and 16 with POCl3 in pyridine gave the 3′-OBn monophosphates; and (2) hydrogenolysis of the 3′-OBn groups using Pd(OH)2 on carbon afforded 5′(S)-CF3 FdUMP analog 4 in 12% yield and 5′(R)-CF3 FdUMP analog 5 in 6% yield over two steps.

Next, we evaluated the efficacy of FdUMP, as well as all five 5′-substituted FdUMP analogs, using a cell-free hTS inhibition assay.30−34 This assay measures TS-catalyzed conversion of dUMP and mTHF to dTMP and dihydrofolate (DHF), the latter of which uniquely absorbs strongly at 340 nm (Figures S1 and S2). This allows reaction monitoring by measuring absorbance at 340 nm over time in the presence of decreasing concentrations of FdUMP or analog thereof (Figure S3). Concentration–response curves were constructed by plotting the normalized reaction rates (calculated using data from the first 100 s after reaction initiation) versus log[inhibitor]. Figure 6 illustrates the concentration–response curves of three of the monophosphates, including 5′(R)-CH3 FdUMP (1, IC50 = 1.21 μM, Figure 6b) and 5′(S)-CF3 FdUMP (4, IC50 = 1.24 μM, Figure 6c), both of which exhibited equimolar potency to FdUMP (IC50 = 1.13 μM, Figure 6a). In contrast, the 5′-epimeric isomers, 5′(S)-CH3 (2) and 5′(R)-CF3 (5), as well as the 5′-gem-dimethyl analog (3) were shown to be completely inactive even at higher concentrations (>20 μM). These results directly support the docking results (Figure 4) as well as the FEP calculations (Table S3), both of which suggested a strong stereochemical and steric preference for 5′(R)-CH3 (1) and 5′(S)-CF3 (4) FdUMP derivatives over the other three 5′-substituted congeners.

Figure 6.

Concentration–response curves of FdUMP (a) and active 5′-functionalized analogs (b and c) against recombinant hTS-mediated conversion of 2′-deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) and 5,10-methylene tetrahydrofolate (mTHF) to deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP) and dihydrofolate (DHF), respectively. The final concentrations of hTS, dUMP, and mTHF in the reaction systems were 0.84 μM, 50 μM, and 250 μM, respectively. The reaction rates were determined by following the change in the optical absorbance at 340 nm, which corresponded to the formation of the coproduct, DHF.

Conclusion

In summary, the mechanism of antitumor activity of fluoropyrimidine-based therapeutics, including 5-FU, floxuridine, and capecitabine, relies heavily on inhibition of TS by the common metabolite FdUMP. However, most of the drugs and prodrugs in this class also cause significant toxicities that are driven by high systemic concentrations of 5-FU. We reported herein a novel application of our previously reported nucleoside 5′-functionalization strategy. Although this approach previously failed to deliver active anti-HCV agents, application of this concept to FdUMP, which is uniquely active at the nucleoside monophosphate stage, proved to be fruitful. As predicted by our modeling efforts and empirically corroborated by synthesizing and evaluating the TS inhibitory activity of these novel nucleoside monophosphates, a strong stereochemical preference for 5′(R)-CH3- and 5′(S)-CF3-substituted FdUMP analogs is apparent. Ongoing efforts involve mechanism of action determination and detailed metabolism experiments designed to test the hypothesis that 5′-functionalization of nucleoside and nucleotide therapeutics limits conversion to the corresponding triphosphate metabolites.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shaoxiong Wu and Dr. Bing Wang, Emory University NMR Center; Dr. Fred Strobel, Emory University Mass Spectrometry; and Dr. John Bacsa, Emory X-ray Crystallography facility for the X-ray structural analysis. We also acknowledge the use of the Rigaku SYNERGY diffractometer, supported by the National Science Foundation under grant CHE-1626172.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- FdUMP

5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate

- FdUTP

5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate

- FUTP

5-fluorouridine 5′-triphosphate

- FUDR

5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine

- TS

thymidylate synthase

- hTS

human thymidylate synthase

- dUMP

2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate

- dTMP

2′-deoxythymidine 5′-monophosphate

- DPD

dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- RdRP

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- MM-GBSA

molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area

- FEP

free energy perturbation

- FUDR

5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine

- TBSCl

tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- PPTS

pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate

- TEMPO

(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxy

- RuCl(p-cymene)[(R,R)-Ts-DPEN]

[N-[(1R,2R)-2-(amino-κN)-1,2-diphenylethyl]-4-methylbenzenesulfonamidato-κN]chloro[(1,2,3,4,5,6-η)-1-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)benzene]-ruthenium

- RuCl(p-cymene)[(S,S)-Ts-DPEN]

[N-[(1S,2S)-2-(amino-κN)-1,2-diphenylethyl]-4-methylbenzenesulfonamidato-κN]chloro[(1,2,3,4,5,6-η)-1-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)benzene]-ruthenium

- TrCl

triphenylmethyl chloride

- DMP

Dess-Martin periodinane

Supporting Information Available

Supporting Information includes: The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsptsci.2c00252.

Molecular modeling protocol and associated data (Table S1, list of 5′-substitutions; Table S2, Prime MM-GBSA; Table S3, FEP); detailed synthetic schemes for compounds 1–5 (Schemes S1–S4); ATH catalyst screen (Table S4); small molecule X-ray crystal structures (Table S5); synthetic procedures, spectroscopic characterization data, and copies of NMR spectra for all purified compounds; in vitro hTS inhibition assay protocol, associated UV absorption spectra (Figures S1 and S2), and representative enzyme inhibition data (Figure S3); summary table comprising tested compounds with IC50 potencies and FEP relative binding energy predictions (Table S6) (PDF)

Author Contributions

Organic synthesis: M.D., N.P., H.B.G., and K.T. Molecular modeling: S.C.P. Pharmacological assays: J.G., H.B.G., S.K.S., M.P.D., P.W.B., C.S., R.S.A., and E.J.M. Manuscript preparation: M.D., J.G., S.C.P., and E.J.M. Project management: L.X., Y.J., J.A.P., E.J.M., and D.C.L.

This study was supported using internal funds from Emory University.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of the ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science virtual special issue “Nucleosides, Nucleotides, and Nucleic Acids as Therapeutics”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Longley D. B.; Harkin D. P.; Johnston P. G. 5-Fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nature Reviews Cancer 2003, 3, 330–338. 10.1038/nrc1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton J.; Lu X.; Hollenbaugh J. A.; Cho J. H.; Amblard F.; Schinazi R. F. Metabolism, Biochemical Actions, and Chemical Synthesis of Anticancer Nucleosides, Nucleotides, and Base Analogs. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14379–14455. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker W. B.; Cheng Y. C. Metabolism and mechanism of action of 5-fluorouracil. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 1990, 48, 381–395. 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeriote F.; Santelli G. 5-Fluorouracil (FUra). Pharmacology & Therapeutics 1984, 24, 107–132. 10.1016/0163-7258(84)90030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezawa K.; Okamoto I.; Tsukioka S.; Uchida J.; Kiniwa M.; Fukuoka M.; Nakagawa K. Identification of thymidylate synthase as a potential therapeutic target for lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 354–361. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Chen D.; Jansson A.; Sim D.; Larsson A.; Nordlund P. Structural analyses of human thymidylate synthase reveal a site that may control conformational switching between active and inactive states. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13449–13458. 10.1074/jbc.M117.787267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters G. J.; Backus H. H. J.; Freemantle S.; van Triest B.; Codacci-Pisanelli G.; van der Wilt C. L.; Smid K.; Lunec J.; Calvert A. H.; Marsh S.; McLeod H. L.; Bloemena E.; Meijer S.; Jansen G.; van Groeningen C. J.; Pinedo H. M. Induction of thymidylate synthase as a 5-fluorouracil resistance mechanism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2002, 1587, 194–205. 10.1016/S0925-4439(02)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreras C. W.; Santi D. V. The Catalytic Mechanism and Structure ofThymidylate Synthase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64, 721–762. 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kholodar S. A.; Ghosh A. K.; Świderek K.; Moliner V.; Kohen A. Parallel reaction pathways and noncovalent intermediates in thymidylate synthase revealed by experimental and computational tools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 10311–10314. 10.1073/pnas.1811059115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer H.; Santi D. V. Purification and amino acid analysis of an active site peptide from thymidylate synthetase containing covalently bound 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridylate and methylenetetrahydrofolate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1974, 57, 689–695. 10.1016/0006-291X(74)90601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santi D. V.; McHenry C. S.; Sommer H. Mechanism of interaction of thymidylate synthetase with 5-fluorodeoxyuridylate. Biochemistry 1974, 13, 471–481. 10.1021/bi00700a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papamichael D. The Use of Thymidylate Synthase Inhibitors in the Treatment of Advanced Colorectal Cancer: Current Status. Stem Cells 2000, 18, 166–175. 10.1634/stemcells.18-3-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diasio R. B. The role of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) modulation in 5-FU pharmacology. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998, 12, 23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodenkova S.; Buchler T.; Cervena K.; Veskrnova V.; Vodicka P.; Vymetalkova V. 5-fluorouracil and other fluoropyrimidines in colorectal cancer: Past, present and future. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2020, 206, 107447. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukourakis G. V.; Kouloulias V.; Koukourakis M. J.; Zacharias G. A.; Zabatis H.; Kouvaris J. Efficacy of the Oral Fluorouracil Pro-drug Capecitabine in Cancer Treatment: a Review. Molecules 2008, 13, 1897–1922. 10.3390/molecules13081897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walko C.; Lindley C. Capecitabine: A review. Clinical Therapeutics 2005, 27, 23–44. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K.; Kinouchi M.; Ishida K.; Fujibuchi W.; Naitoh T.; Ogawa H.; Ando T.; Yazaki N.; Watanabe K.; Haneda S.; Shibata C.; Sasaki I. 5-FU Metabolism in Cancer and Orally-Administrable 5-FU Drugs. Cancers 2010, 2, 1717–1730. 10.3390/cancers2031717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusarczyk M.; Serpi M.; Ghazaly E.; Kariuki B. M.; McGuigan C.; Pepper C. Single Diastereomers of the Clinical Anticancer ProTide Agents NUC-1031 and NUC-3373 Preferentially Target Cancer Stem CellsIn Vitro. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 8179–8193. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c02194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Voorde J.; Liekens S.; McGuigan C.; Murziani P. G. S.; Slusarczyk M.; Balzarini J. The cytostatic activity of NUC-3073, a phosphoramidate prodrug of 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine, is independent of activation by thymidine kinase and insensitive to degradation by phosphorolytic enzymes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 441–452. 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan C.; Murziani P.; Slusarczyk M.; Gonczy B.; Vande Voorde J.; Liekens S.; Balzarini J. Phosphoramidate ProTides of the Anticancer Agent FUDR Successfully Deliver the Preformed Bioactive Monophosphate in Cells and Confer Advantage over the Parent Nucleoside. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 7247–7258. 10.1021/jm200815w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagden S.; Spiliopoulou P.; Spiers L.; Gnanaranjan C.; Qi C.; Woodcock V. K.; Moschandreas J.; Tyrrell H. E. J.; Griffiths L.; Butcher C.; Ghazaly E.; Evans T. R. J. A phase I first-in-human, dose-escalation and expansion study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of NUC-3373 in patients with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic solid malignancies. Annals of Oncology 2018, 29, viii145. 10.1093/annonc/mdy279.429. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dasari M.; Ma P.; Pelly S. C.; Sharma S. K.; Liotta D. C. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 5′-C-methyl nucleotide prodrugs for treating HCV infections. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127539. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers K. J.; Chow D. E.; Xu H.; Dror R. O.; Eastwood M. P.; Gregersen B. A.; Klepeis J. L.; Kolossvary I.; Moraes M. A.; Sacerdoti F. D.; Salmon J. K.; Shan Y.; Shaw D. E.. Scalable Algorithms for Molecular Dynamics Simulations on Commodity Clusters. In SC ’06: Proceedings of the 2006 ACM/IEEE Conference on Supercomputing, November 11–17, 2006, Tampa, FL; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, 2006; pp 43–43.

- Shaw D. E.Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, 2022; Schrödinger: New York.

- Bligh C. M.; Anzalone L.; Jung Y. C.; Zhang Y.; Nugent W. A. Preparation of both C5′ epimers of 5′- C -methyladenosine: Reagent control trumps substrate control. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 3238–3243. 10.1021/jo500089t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Astruc D. The Golden Age of Transfer Hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6621–6686. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash G. K. S.; Krishnamurti R.; Olah G. A. Fluoride-Induced Trifluoromethylation of Carbonyl Compounds with Trifluoromethyltrimethylsilane (TMS-CF3). A Trifluoromethide Equivalent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 393–395. 10.1021/ja00183a073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash G. K. S.; Wang F.; Zhang Z.; Haiges R.; Rahm M.; Christe K. O.; Mathew T.; Olah G. A. Long-Lived Trifluoromethanide Anion: A Key Intermediate in Nucleophilic Trifluoromethylations. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2014, 53, 11575–11578. 10.1002/anie.201406505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash G. K. S.; Yudin A. K. Perfluoroalkylation with Organosilicon Reagents. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 757–786. 10.1021/cr9408991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal N.; Hong B.; Mihai C.; Kohen A. Vibrationally Enhanced Hydrogen Tunneling in the Escherichia coli Thymidylate Synthase Catalyzed Reaction. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 1998–2006. 10.1021/bi036124g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam Z.; Strutzenberg T. S.; Gurevic I.; Kohen A. Concerted versus Stepwise Mechanism in Thymidylate Synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9850–9853. 10.1021/ja504341g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelace L. L.; Gibson L. M.; Lebioda Cooperative Inhibition of Human Thymidylate Synthase by Mixtures of Active Site Binding and Allosteric Inhibitors. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 2823–2830. 10.1021/bi061309j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo-Ahen O. M. H.; Tochowicz A.; Pozzi C.; Cardinale D.; Ferrari S.; Boum Y.; Mangani S.; Stroud R. M.; Saxena P.; Myllykallio H.; Costi M. P.; Ponterini G.; Wade R. C. Hotspots in an Obligate Homodimeric Anticancer Target. Structural and Functional Effects of Interfacial Mutations in Human Thymidylate Synthase. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3572–3581. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale D.; Guaitoli G.; Tondi D.; Luciani R.; Henrich S.; Salo-Ahen O. M. H.; Ferrari S.; Marverti G.; Guerrieri D.; Ligabue A.; Frassineti C.; Pozzi C.; Mangani S.; Fessas D.; Guerrini R.; Ponterini G.; Wade R. C.; Costi M. P. Protein–protein interface-binding peptides inhibit the cancer therapy target human thymidylate synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, E542-E549 10.1073/pnas.1104829108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.