Abstract

Racial trauma refers to experiences related to threats, prejudices, harm, shame, humiliation, and guilt associated with various types of racial discrimination, either for direct victims or witnesses. In North American, European, and colonial zeitgeist societies, Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) experience racial microaggressions and interpersonal, institutional, and systemic racism on a repetitive, constant, inevitable, and cumulative basis. Although complex trauma differs from racial trauma in its origin, the consistency of racist victimization beyond childhood, and the internalized racism associated with it, strong similarities exist. Similar to complex trauma, racial trauma surrounds the victims’ life course and engenders consequences on their physical and mental health, behavior, cognition, relationships with others, self-concept, and social and economic life. There is no way to identify racial trauma other than through a life-course approach that captures the complex nature of individual, collective, historical, and intergenerational experiences of racism experienced by BIPOC communities in Western society. This article presents evidence for complex racial trauma (CoRT), a theoretical framework of CoRT, and guidelines for its assessment and treatment. Avenues for future research, intervention, and training are also presented.

Keywords: racial trauma, complex trauma, racial discrimination, Black, Indigenous, people of color, assessment and treatment

Defined as the cumulative impact of race-based traumatic experiences at individual, institutional, and systemic levels, racial trauma has significant effects on mental and physical health as well as on social and economic aspects of victims’ lives (Comas-Díaz, 2016; Helms et al., 2010). The purpose of this article is to present a new theoretical framework of racial trauma. It is based on the real-life experiences of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) in the face of repetitive and current racial discrimination in Western societies, as well as clinical and social issues related to the expression of related psychological distress. Indeed, the experiences of racial discrimination that BIPOC individuals face affect different spheres of their lives, including their physical and mental health, ability to study and work, relationships, family life, finances, behaviors in daily life, and interactions with others (Williams & Mohammed, 2013; Dominguez et al., 2008; Epstein, 2005; Gee et al., 2012; Harris & Lieberman, 2015; Hope et al., 2021; Katz & Joseph, 2014; Paradies, 2006; Trent et al., 2019). These impacts are amplified by the intersectional aspects of social and gender conditions (Cole, 2009; Crenshaw, 1989; Shaw et al., 2012), as well as the institutional and systemic pervasiveness of racism in Western societies and even in other societies in which BIPOC populations constitute a majority (Delgado & Stefancic, 2018; DiAngelo, 2018; Feagin & Bennefield, 2014; Kendi, 2019). The new framework presented in this article, the complex racial trauma (CoRT) framework, provides evidence portraying how racial trauma can be understood only through the complexities associated with (a) the repetitive, constant, inevitable, and cumulative victimization of race-based stress, everyday and major racial discrimination, and microaggressions in racist systems and (b) the major consequences on victims’ lives. The article is divided into five sections providing evidence and a theoretical framework of complex racial trauma, guidelines necessary for assessing and treating complex racial trauma, and elements for further research.

Evidence of Complex Racial Trauma

What is complex trauma?

Various studies have defined complex trauma as the exposure to multiple, recurring interpersonal traumatic events over an extended period of time (Briere & Scott, 2015; Felitti et al., 1998; The National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 2020). Forms of complex trauma often cited in the scientific literature include sexual, physical, and psychological abuse; maltreatment experiences during childhood; and experiences of war and torture (Cook et al., 2005). These traumas often have a major impact on the physical and mental health of victims and the types of interpersonal relationships they have in different social contexts throughout their lives (Lewis et al., 2021; McCormack & Thomson, 2017; Wong et al., 2016). Studies of complex trauma have shown that it affects the lives of children over the long term on many levels, encompassing problems with attachment and relationships, physical health, emotional responses, dissociative attitudes, behaviors, cognitive aspects, self-concept, long-term health, and finances (Cook et al., 2005; Courtois, 2004). Studies conducted among individuals who have experienced complex trauma have shown consequences on their mental health, including a higher prevalence of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, sleep problems, suicidal ideation and behavior, and alcohol and substance use, as well as affect dysregulation, impulsivity, and personality disorders (Briere et al., 2010, 2015; Briere & Scott, 2015; Karam et al., 2014; McCormack & Thomson, 2017; Nickerson et al., 2012; Zyromski et al., 2018). Other studies have also shown a significant association between complex trauma and impaired physical health, including hypertension, diabetes, digestive disorders, obesity, poor heart health and cardiovascular risk, and high cortisol production (Isohookana et al., 2016; Klassen et al., 2016; Monnat & Chandler, 2015; Park et al., 2016). Moreover, the experience of complex trauma increases the risk of experiencing further trauma over the long term, including violence in romantic relationships (Cook et al., 2005; Courtois, 2004). Other studies have also shown that complex trauma is associated with dysfunctional behaviors, brain-development alterations, identity disturbance, and learning problems (Beers & De Bellis, 2002; Gabowitz et al., 2014). In addition, people who have experienced racial trauma have more insecure attachment, relational dysfunction, and complicated interpersonal relationships, including higher rates of divorce, separation, and marital problems (Briere & Scott, 2015; Zyromski et al., 2018). All of these consequences and issues surrounding complex trauma demonstrate that it is an issue that permeates victims’ lives, structures their relationships with others, and engenders consequences for their health and socioeconomic life (Cook et al., 2005). In this sense, complex trauma is reminiscent of what people who have experienced racial trauma experience.

What is racial trauma?

Racial trauma refers to dangerous experiences related to threats, prejudices, harm, shame, humiliation, and guilt associated with various types of racial discrimination either of victims directly or through witnesses (Comas-Díaz, 2016; Helms et al., 2010). Experiences related to racial trauma at different stages of life for BIPOC individuals can include microaggressions, inappropriate behaviors that encompass physical and verbal attacks, violence, death threats, being beaten and left for dead by attackers, as well as witnessing racist murders (Jernigan & Daniel, 2011; Saleem et al., 2020; M. T. Williams, Metzger, et al., 2018). One of the important aspects of racial trauma is its ubiquity and omnipresence in the life of racialized people. Studies conducted in the United States showed that racialized groups, including Black, Hispanic, Indigenous, and Asian individuals, are very commonly victims of microaggressions and racial discrimination (Hudson et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2019; Seaton et al., 2008). According to a national survey in the United States, 50% to 70% of Black, Hispanic, and Asian people stated they had been victims of racial discrimination (Lee et al., 2019). In Canada, a recent study showed that most Black people experienced different types of racial trauma (Cénat et al., 2022). More than 70% of the participants declared having experienced everyday racial discrimination in the past month, and more than 60% and 53% of them reported experiencing major racial discrimination in education and health services. 1 The same study highlighted that more than 90% of participants said they had experienced racial microaggressions. Referred to in the scientific literature under various terms, including ethnoviolence, racial-based stress, racial-based trauma, racism-based trauma, race-based traumatic stress, and racist incident–based trauma (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2005; Carter, 2007; M. T. Williams, Metzger, et al., 2018), racial trauma produces similar clinical symptoms to that of PTSD (Carter, 2007). Over the last few years, empirical research has corroborated this claim (Roberson & Carter, 2022; Sibrava et al., 2019).

In addition to the pervasiveness and consistency of racial discrimination and trauma in racialized people’s personal lives at systemic and institutional levels, they occur in their neighborhoods, schools, workplace, social and health services, and economic and financial services on a repetitive, multiple, and cumulative basis (Cénat et al., 2022; Feagin, 2013; Harrell, 2000; Lee et al., 2019). People exposed to instances of racial trauma do not experience an isolated incident but rather repeated incidents of both the same and new forms of racial trauma. The work of Awad and colleagues demonstrated how Americans of Middle Eastern and North African descent have experienced racial trauma cumulatively while exploring this on both micro- and macrolevels, including individual accounts of their experiences (Awad et al., 2019). The authors highlighted how historical trauma; the harmful national context; societal, institutional, and interpersonal discrimination; and microaggressions overlap and are interconnected in their impact on the lives of these Americans. The cumulative impact of racial trauma was demonstrated in BIPOC communities in North America, Europe, and Oceania (Becares et al., 2016; Hollinsworth, 2006; Wallace et al., 2016; Williams, Metzger, et al., 2018). According to various studies, what sets racial trauma apart from PTSD is the constant and cumulative impact of microaggressions and other forms of racial discrimination that BIPOC communities are exposed to (Comas-Díaz et al., 2019; Harrell, 2000; Williams, Metzger, et al., 2018). Likewise, the aspect of “post” outlined in PTSD does not reflect racial trauma because BIPOC individuals continue to consistently live through societal oppression. Although these victimizations are micro, they are a constant reminder of other major discrimination they experienced. They are also associated with pervasive consequences on multiple aspects of the victim’s life.

Consequences of racial trauma and similarities with complex trauma

Williams and Mohammed elucidated the framework of the impact of racial trauma on the lives of BIPOC individuals (Williams & Mohammed, 2013). This framework of the process and impact of racial discrimination is similar to complex trauma in the sense that racism is experienced at a sufficiently young age for BIPOC individuals, and it continues over the course of their lives (Cook et al., 2005; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). More importantly, racial trauma surrounds their lives in the same way that complex trauma does. There are biological impacts (central nervous system, endocrine, metabolic, immune, cardiovascular), interpersonal consequences (conduct problems, adjustment problems, externalizing problems, difficulty in romantic relationships), cognitive effects (internalizing problems, self-esteem), socioeconomic consequences (difficulty maintaining a job, unemployment, poverty), and major long-term health impacts (Beach et al., 2022; Brondolo et al., 2008; Carter et al., 2021; Cénat, Kogan, et al., 2021; Hart et al., 2021; Levine et al., 2014; Metzger et al., 2018; Seaton & Carter, 2020; Walker et al., 2014; Williams, 1999; Williams et al., 1997; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). In fact, racial trauma is considered as a major risk factor for victims in terms of physical health (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, endocrine and cardiovascular illness) and mental-health concerns (i.e., depression, anxiety, PTSD, substance abuse, suicidal ideation and behaviors), in addition to premature death (Cardarelli et al., 2010; Chae et al., 2012; Dolezsar et al., 2014; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). Moreover, children and adolescents who experienced different forms of racial discrimination faced developmental concerns and experienced major internalized and externalized problems that may interfere with significant aspects of their lives later on (Brody et al., 2006, 2014; Zimmerman & Miller-Smith, 2022).

Regardless of how racial trauma is defined, in individual experiences of those who have faced it, and in the biological, cognitive, interpersonal, socioeconomic, and health-related consequences, there are apparent similarities between the experiences of those who face racial trauma and those who face complex trauma. More importantly, it is clear that racial trauma itself must be considered complex as a whole given its cumulative and pervasive character and its intrusive and destructive consequences throughout the lives of victims (Carter et al., 2021). Like complex trauma, there is no way to identify racial trauma apart from a life-course approach that allows us to capture the complex nature of individual, collective, and intergenerational experiences of BIPOC individuals in society (Gee et al., 2012).

Theoretical Framework of Complex Racial Trauma

As I explained in a recent article, I was particularly intrigued by a volume of request for psychotherapeutic interventions from Black men aged 30 to 40 years old (Cénat, 2022). Recently, while checking my voicemail, I came across this message: “Brother, I am having trouble breathing. I am at work and they just hired the person I left my previous job for as my boss. It took me years to get out of the depression I had because of his racist comments. In 5 years, despite being their best engineer, I have not been promoted at all. Brother, I think I am going to die. Can you take me in today? Please do.” I could hear in his trembling voice the turmoil he was facing and the feeling that the sky had fallen, at the thought that he would either have to run away from his job where he was thriving after years of depression or face his aggressor. Although I know well the serious consequences of racism, I could not imagine with this message the impact that this man’s experiences of racial discrimination had on him and his family. Indeed, the racist insults and microaggressions experienced in his last job, particularly from his former boss who was just hired as his new boss in his new position, reminded him of other racist experiences in primary school, secondary school, and university. His severe depression led to a stay in a psychiatric hospital, was the main reason for his divorce, the loss of custody of his children for about 2 years, a long period of sick leave, moving back in with his parents for 2 years, his financial insolvency, the loss of his house, and the inability to obtain a bank loan for several years. The impacts of his racist experiences surrounded all spheres of his life and went far beyond what the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnostic criteria for PTSD can capture.

PTSD, as conceptualized in the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) fails to capture three fundamental aspects of racial trauma: its cumulative nature; the constant and inevitable concern surrounding interpersonal, institutional, and systemic racism; and developmental hindrance. Criterion A in the DSM-5 allows for the identification of an element defined as the “stressor” that is a prerequisite for the development of PTSD symptoms. BIPOC individuals rarely identify with one single occurrence of racial trauma. Instead, they generally find themselves within two main categories of traumatic experiences based on their skin color: major racial trauma and everyday racial trauma (Carter, 2007; Saleem et al., 2020; Williams, Metzger, et al., 2018). First, BIPOC individuals identify various key events that they tend to remember: openly racist remarks by classmates, teachers, acquaintances, and even strangers with whom they may interact; rejection based on the color of their skin (e.g., refusing to offer services, refusal of a job or a promotion, benefits of job seniority, admittance to university, bank loans, being able to rent an apartment or home); threats; physical injuries; and so on (Carter, 2007; Carter et al., 2017; Cénat et al., 2022; David et al., 2019; Hollinsworth, 2006; Kirkinis et al., 2021). Second, they also experience daily inconveniences, inappropriate comments, and actions based on race, as well as racial microaggressions (Garcia & Johnston-Guerrero, 2016; Metinyurt et al., 2021; Ogunyemi et al., 2020). These behaviors, intentional or not, given their repetitive, intrusive, and pernicious nature, cause hypervigilance within BIPOC individuals (Carter & Forsyth, 2010). These microaggressions, as well as systemic racism, surround the lives of BIPOC communities living in Western societies (Cénat et al., 2022; DiAngelo, 2018; Kendi, 2017; Williams, 2020). These two types of racial discrimination, based on their cumulative nature, do not correspond with the criteria of the DSM-5, but they contain important stressors that cause psychological distress for BIPOC individuals. Moreover, they negatively affect their well-being, how they view others, and even how they view their own selves without social support and personal and community resilience (Cénat, Dalexis, et al., 2021; Derivois, 2017). Moreover, racial discrimination is not limited to an interpersonal level. In fact, BIPOC communities face a pattern of racist acts and barriers in educational, health, judicial, and social institutions; child-protection services; and systems that reinforce the ongoing nature of racism (Cénat et al., 2020; Cénat, Noorishad, et al., 2021; Feagin, 2013; Hill, 2004; Phillips-beck et al., 2020). In addition to the cumulative nature of racism and the consistency of interpersonal, institutional, and systemic racism, racial trauma also creates developmental barriers for BIPOC communities. Research over the last 3 decades has shown that racial trauma not only causes symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and so on but also significantly and intrusively affects the life course of BIPOC individuals. Like complex trauma, it affects their lives in many facets, including attachments and interpersonal relationships, physical health, emotional responses, dissociative attitudes, general behaviors, cognitive aspects, self-esteem, long-term mental- and physical-health concerns, and economic impact.

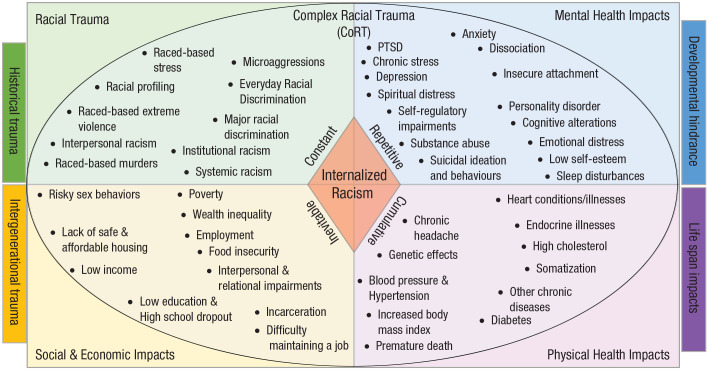

Some researchers can argue that racial trauma is simply a complex trauma like any other and does not need a separate category. However, racial trauma differs from complex trauma in three fundamental ways: its origin, constancy beyond childhood, and internalization. Effectively, racial trauma is founded on an outdated attempt to classify the “human race” and a racist ideology based on White supremacy (DiAngelo, 2018; Dunbar-Ortiz, 2019; Firmin, 2000; Gobineau, 1915; Kendi, 2017, 2019). As highlighted in the critical-race literature, even race is a myth (Sussman, 2014), and the beliefs in race have resulted in dire social, economic, and health outcomes for BIPOC individuals. Racism is a pervasive element that surrounds individuals’ lives, institutions, the social system, and even the social contract in North America, Europe, and beyond (Bussolo et al., 2018; Rockich-Winston et al., 2021). Some studies have shown that BIPOC individuals experience different forms of racial discrimination in schools, churches, housing, bank loans, hospitals, and health services (within health care and medications) and in the judicial and correctional system (Cénat et al., 2022; Hollinsworth, 2006; Kirkinis et al., 2021). Beyond its impact on individuals, racist ideologies have permeated institutions and shaped policy and many domains, including social, economic, and educational systems; public health care; judicial and correctional systems; and policing and security systems in ways that significantly interfere with the lives of BIPOC communities (Barber et al., 2020; Feagin & Bennefield, 2014; Kendi, 2019). This foundation of racial trauma that is based on skin color and other physical and cultural characteristics is the first element that sets it apart from complex trauma. The second difference is that racial trauma is constant in the lives of BIPOC individuals and does not end in childhood or adolescence. Indeed, racial trauma is repetitive (beyond adolescence) and accumulates throughout the lives of BIPOC communities. This constant characteristic of racial trauma creates a racial hypervigilance that surrounds the lives of racialized people and threatens their psychological integrity (Carter & Forsyth, 2010). A concrete example is the fact that Black men in Western countries often ask their female partners to drive when they are taking longer trips to reduce the risk of being stopped by police. The third and final element that makes racial trauma even more complex but that still differentiates it from complex trauma is internalized racism. Internalized racism is a consequence of racial trauma that Bivens (2005) defined as the process by which racialized individuals internalize the thoughts of the dominant group over that of the racial group that they belong to, leading to the reproduction of attitudes, behaviors, and ideologies that have now created a system of oppression and privilege. It is important to differentiate internalized racism from low self-esteem issues. Internalized racism goes beyond self-esteem and establishes itself among BIPOC individuals and hinders their capabilities to be resilient and their ability to help members of their community be resilient when they face experiences of discrimination (Bivens, 2005; David et al., 2019). Considering evidence related to the complexities that surround racial trauma while keeping in mind the similarities and differences to complex trauma, I propose to conceptualize race-based trauma as CoRT. This conceptualization allows for the related aspects of racial trauma to be taken into account, namely its origin (a race-based trauma), its cumulative and repetitive character, its constant character (in contrast to complex trauma, it continues past childhood/adolescence), and the consequences that go beyond those of “normal” trauma and that become entrenched in many facets of the lives of victims, altering and hindering their self-perception and that of their own communities. Figure 1 presents the CoRT theoretical framework and its related complexities. It applies to countries in which BIPOC individuals constitute a minority. It also applies to countries in which BIPOC individuals are a majority but face the predominance of a White minority that establishes a racist economic and social system that ostracizes them.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical framework of the complex racial trauma.

Assessment of Complex Racial Trauma

In general, the assessment of racial trauma does not align with the conceptualization of Criterion A (stressor) of the DSM-5 or previous versions of the DSM. Criterion A allows only for the integration of certain aspects of racial trauma to which people are exposed to (e.g., death threats, physical assault) that affect their physical and mental health as well as their life in the long term. Moreover, it does not allow for the consideration of the repetitive aspect of racial trauma. The same concerns are presented for complex trauma (Cook et al., 2005). Over the last 10 years, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) developed a guide to help mental-health professionals evaluate complex trauma (NCTSN, 2018). It allows for the consideration of various forms of trauma (e.g., abuse, neglect, natural disaster, school and community violence, war), the duration or timeline of these incidents, how they continue to affect the victim, the consideration of adverse effects of these traumas, and their assessment. Various scales currently allow assessing multiple traumas, including life-event scales and traumatic experiences assessed prior to the assessment of PTSD (Hamby et al., 2005; Weathers et al., 2013). Nevertheless, none integrate the destructive characteristics of racial trauma and the long-term consequences for victims. Although the complex experiences of BIPOC individuals are not yet integrated, there are various measures that were developed over the last few years (Carter et al., 2013; Loo et al., 2001; Williams, Metzger, et al., 2018; Williams, Printz, et al., 2018). Among these measures, the Race-Based Traumatic Stress Symptom Scale (RBTSSS) and the UConn Racial/Ethnic Stress and Trauma Survey (UnRESTS) deserve special consideration (Carter et al., 2013; Carter & Muchow, 2017, 2018; M. T. Williams, Metzger, et al., 2018).

The RBTSSS

Developed by Carter and his team, the RBTSSS is a measure that was created to evaluate the reactions of emotional and psychological stress associated with the experiences of racial trauma and racism (Carter et al., 2013). The scale is based on the race-based traumatic stress injury theory previously developed by Carter (2007). This scale of 52 items contains 7 subscales that evaluate depression, anger, physical reactions, avoidance, intrusion, hypervigilance/arousal, and low self-esteem. Although the items are similar to the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5, this scale is different in how the stressors or traumatic events in question are linked to racial challenges (Carter et al., 2013, 2018; Carter & Muchow, 2017). In addition to items on intrusive, arousal, and avoidance symptoms of PTSD, this scale also contains items addressing anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, shame, and guilt, which are feelings that often accompany the experience of racial trauma among BIPOC individuals. At the beginning of the RBTSSS, people are asked to specify three major racial-based traumas that they have experienced. Next, they respond to items assessing emotional and psychological reactions while keeping in mind the most significant racial-based trauma they have experienced. That said, the scale does not consider the repetitive or cumulative nature of complex racial trauma, but it specifically addresses psychological distress related to the most important race-based trauma experienced by the person. This scale can be very useful in terms of clinical intervention, but it cannot be used to make a diagnosis.

The UnRESTS

The UnRESTS aims to evaluate PTSD related to race-based trauma (racial discrimination, acts of racism; Williams, Metzger, et al., 2018). This scale consists of seven sections: an introduction to the interview, racial and ethnic identity development, experiences of direct overt racism, experiences of racism by loved ones, experiences of vicarious racism, experiences of covert racism, racial trauma assessment (symptoms of reexperiencing, avoidance, negative changes in cognition and mood, physiological arousal and reactivity, dissociative symptoms, distress and interference, and duration of disturbance are evaluated on a “Yes” or “No” scale). The Racial Trauma Assessment subscale instructions dealing with symptoms of PTSD addresses the repetitive and cumulative nature of complex racial trauma. It is the only scale that allows posing a diagnosis: racial PTSD.

Nevertheless, the consequences of complex racial trauma extend beyond PTSD in terms of mental health. These consequences include other mental-health concerns (e.g., anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, psychological distress, behavior and relationship problems, diet, and nutritional concerns), alcohol and substance abuse, physical-health problems (diabetes, hypertension, overweight). Social and economic aspects, among others, must also be evaluated to understand the harmful effects of complex racial trauma and address those that can be treated in clinical care. Although scales such as the RBTSSS and UnRESTS contain significant advancements to understand the consequences of racial trauma in terms of mental health, further efforts are needed. These efforts must integrate the repetitive, cumulative, and constant nature of racial trauma and its various impacts on physical and mental health throughout the lives of BIPOC communities.

Treatments of Complex Racial Trauma

Although the scientific literature has become more focused on race-based trauma, few studies have been devoted to treatments that can adequately address these issues (Chioneso et al., 2020; Metzger et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the literature contains many attempts to develop treatments for racial trauma (Bryant-Davis & Ocampo, 2006; Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019; Chioneso et al., 2020; Comas-Díaz, 2016; Markin & Coleman, 2021; Metzger et al., 2021). Bryant-Davis and Ocampo (2006) underlined a combination of factors that traditional therapies should integrate before being able to address instances of racial trauma that their clients have dealt with in an appropriate way: acknowledgment (therapists must recognize that their clients have to face the reality of the racist instances that they have dealt with); sharing (creating a supportive and compassionate environment to help clients share their experiences without shame); safety and self-care (creating a secure and stable environment to help clients protect themselves against new occurrences of racist aggression without blaming them for a situation that they did not create and to provide them with resources for self-care); grieving/mourning the losses (helping clients identify the dimensions of the loss and to define a new representation of self); shame and self-blame/internalized racism (helping clients to question the cognitive distortions that lead them to feel shameful, blame themselves, or to develop internalized racism and work with them to move past this stage); anger (being nonjudgmental and supportive, therapists are supposed to address clients’ anger, which is crucial in the case of racial-trauma therapists of the same race as the perpetrators who must be careful not to defend the perpetrators or become defensive); coping strategies (helping clients identify their own personal adaptation strategies that will allow them to acquire adaptive skills and stress management); and resistance strategies (inspired by liberation psychology, empowering the client to improve their life and the lives of those around them; Comas-Díaz, 2020; Quiñones-Rosado, 2020). Comas-Díaz (2016) designed a race-informed therapeutic approach that integrates systems of ethnic healing, liberation psychology, and culturally appropriate traditional therapies to address racial trauma. This approach consists of five phases: evaluation and stabilization, desensitization, reprocessing, psychological decolonization, and social action. This approach makes it possible to address both racial trauma and stress based on race by empowering survivors to render themselves more capable of expressing and transforming their reality. Chavez-Dueñas et al. (2019) developed the Healing Ethno-Racial Trauma (HEART) framework that aims to create a culturally adapted treatment to address racial trauma for people with Latin origins living in the United States. He stated:

Healing from the fear of danger that results from experiencing or witnessing discrimination, threats of harm, violence, and intimidation directed at ethnic and racial minority groups requires that individuals, families, and communities create and hold some level of control and power over the ways in which they are internally and externally oppressed. (p. 55)

The HEART framework contains four phases: establishing sanctuary spaces for Latinx experiencing ethnoracial trauma; acknowledging, reprocessing, and coping with symptoms of ethnoracial trauma; strengthening and connecting individuals, families, and communities to survival strategies and cultural traditions that heal; and liberation and resistance. Although other attempts to design therapies or adaptations of existing treatments to promote culturally adapted interventions among victims of racial trauma have been developed (Chavez-Dueñas et al., 2019), very few have been evaluated and published.

Williams et al. (2014) described the development of cultural adaptation of prolonged exposure therapy to prevent PTSD among African Americans by providing evidence through two clinical cases. Carlson et al. (2018) reported a race-based stress and trauma intervention for veterans of color in four states in the United States, but it does not quantify the benefits. Conway-Phillips et al. (2020) outlined qualitative evidence to address race-based stress, through focus groups, with women who have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and who participated in the Resilience, Stress, and Ethnicity (RiSE) program. Saban et al. (2021) highlighted preliminary quantitative evidence for the RiSE program from a larger sample of women with cardiovascular risk. M. T. Williams et al. (2020) reported essential improvements in the symptoms of racial trauma, traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression for people of color in North America after experiences with psychedelics. Bhambhani and Gallo (2021) developed a mindfulness program adapted for people of color. They recommended the importance of adding elements that specifically address race-based stress and trauma because the people of color they received in 2020 repeatedly reported facing various forms of race-based discrimination.

Theoretical and empirical studies developed to culturally address racial trauma have a common set of elements (Chioneso et al., 2020; Comas-Díaz, 2016; Metzger et al., 2021). These studies have shown the need for clinicians to recognize race-based trauma victimization, empower victims, integrate trauma-focused therapeutic aspects, consider cultural aspects in the expression of trauma as well as cultural systems of care, amplify clients’ social support and connection to their communities (spirituality, culture, religion), and integrate liberation psychology into the care and empowerment process of clients to help them navigate future racist incidents and help those around them (Comas-Díaz, 2020; Quiñones-Rosado, 2020). However, these studies have also shown the need to continue to develop, implement, and evaluate programs that improve the well-being of people of color who experience racial trauma. For youth, although a few programs exist (Saleem et al., 2020), there is a need to consider the development of racial-trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy that can address the racial issues of trauma faced by youth of color. All treatment provided to BIPOC individuals should also integrate the antiracism framework for mental-health care to better integrate developmental hindrance caused by racial trauma (Cénat, 2020). However, therapeutic settings need to start by providing a safe space, free from any kind of racial discrimination, to clients and patients from BIPOC communities. In a research conducted in Canada, 53.1% of Black participants declared having experienced major racial discrimination in health-care settings (Cénat et al., 2022). It is important to be clear: Racist health-care settings cannot provide antiracist mental health care.

Conclusions and Further Research

As highlighted throughout this article, racial trauma is always complex. Therefore, understanding, identifying, assessing, and treating it requires consideration and integration of the complexities surrounding it. Further research is needed to reveal other aspects of the complexities surrounding racial trauma. Two areas of research should be the focus of intensive study in the coming years: the assessment of racial trauma and the treatment of racial trauma. Indeed, instruments that consider the different aspects of racial trauma (repetitive, constant, collective/cumulative, inevitable, etc.) are needed. Likewise, there is a critical need to develop appropriate treatments and specially to evaluate their efficacy. Future research in these two areas will pave the way for a third practical area, which is the training of clinicians already working in different areas of mental health and of students in psychology, psychiatry, social work, family medicine, nursing, and other mental-health-related fields. This third area should not be ignored. It must be an important step in achieving mental-health care that no longer discriminates against BIPOC communities. If we want to create an inclusive and antiracist society, training efforts must be broadened to reach social, personality, and organizational psychologists; human resources professionals; teachers; scholars; researchers; physicians; schools and universities; health settings; workplaces; social services; housing; and so on. Ultimately, the best response to all the issues surrounding racism, including complex racial trauma, will be its eradication in society. Although racism is not inevitable, the analysis of the current situation in Western societies shows that this will not happen overnight. Even if racism were over (which is not at all the case), understanding these issues would remain vital for repairing the damage that has been caused, avoid the transgenerational transmission of complex racial trauma, and consolidate the gains made.

Everyday racial discrimination refers to daily race-based insults, hassles, and unfair treatment in daily interpersonal interactions, including receiving poorer services, being treated with less courtesy, being followed in stores, and so on (Essed, 1991; Mouzon & McLean, 2017). Major racial discrimination refers to experiences of blatant instances of unfair treatment in different spheres such as health services, hiring, employment, and education.

Transparency

Action Editor: Tina M. Lowrey

Editor: Klaus Fiedler

The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Funding: This work was partially funded by Public Health Agency of Canada Grant 1920-HQ-000053, Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant 469050, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Grants 430-2019-00041 and 1036-2021-00702.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). [Google Scholar]

- Awad G. H., Kia-Keating M., Amer M. M. (2019). A model of cumulative racial-ethnic trauma among Americans of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) descent. American Psychologist, 74(1), 76–87. 10.1037/AMP0000344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber P. H., Hayes T. B., Johnson T. L., Márquez-Magaña L. (2020). Systemic racism in higher education. Science, 369(6509), 1440–1441. 10.1126/SCIENCE.ABD7140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach S. R. H., Gibbons F. X., Carter S. E., Ong M. L., Lavner J. A., Lei M. K., Simons R. L., Gerrard M., Philibert R. A. (2022). Childhood adversity predicts black young adults’ DNA methylation-based accelerated aging: A dual pathway model. Development and Psychopathology, 34(2), 689–703. 10.1017/S0954579421001541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becares L., Wallace S., Nazroo J. (2016). Cumulative exposure to racial discrimination across time and domains: Exploring racism’s long term impact on the mental health of ethnic minority people in the UK. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70, Article A101. 10.1136/jech-2016-208064.206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beers S. R., De Bellis M. D. (2002). Neuropsychological function in children with maltreatment-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(3), 483–486. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhambhani Y., Gallo L. (2021). Developing and adapting a mindfulness-based group/intervention for racially and economically marginalized patients in the Bronx. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. Advance online publication. 10.1016/J.CBPRA.2021.04.010 [DOI]

- Bivens D. K. (2005). What is internalized racism? In Leiderman S., Bivens D., Major B. (Eds.), Flipping the script: White privilege and community building? (pp. 43–51). MP Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J., Godbout N., Dias C. (2015). Cumulative trauma, hyperarousal, and suicidality in the general population: A path analysis. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 16(2), 153–169. 10.1080/15299732.2014.970265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J., Hodges M., Godbout N. (2010). Traumatic stress, affect dysregulation, and dysfunctional avoidance: A structural equation model. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(6), 767–774. 10.1002/jts.20578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J., Scott C. (2015). Complex trauma in adolescents and adults: Effects and treatment. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 38, 515–427. 10.1016/j.psc.2015.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody G. H., Chen Y. F., Murry V. M. B., Simons R. L., Ge X., Gibbons F. X., Gerrard M., Cutrona C. E. (2006). Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development, 77(5), 1170–1189. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody G. H., Lei M. K., Chae D. H., Yu T., Kogan S. M., Beach S. R. H. (2014). Perceived discrimination among African American adolescents and allostatic load: A longitudinal analysis with buffering effects. Child Development, 85(3), 989–1002. 10.1111/cdev.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E., Libby D. J., Denton E. G., Thompson S., Beatty D. L., Schwartz J., Sweeney M., Tobin J. N., Cassells A., Pickering T. G., Gerin W. (2008). Racism and ambulatory blood pressure in a community sample. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(1), 49–56. 10.1097/PSY.0B013E31815FF3BD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T., Ocampo C. (2005). Racist incident–based trauma. The Counseling Psychologist, 33(4), 479–500. 10.1177/0011000005276465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T., Ocampo C. (2006). A therapeutic approach to the treatment of racist-incident-based trauma. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 6(4), 1–22. 10.1300/J135v06n04_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bussolo M., Davalos M. E., Peragine V., Sundaram R. (2018). Toward a new social contract: Taking on distributional tensions in Europe and Central Asia. World Bank. 10.1596/978-1-4648-1353-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardarelli R., Cardarelli K. M., Fulda K. G., Espinoza A., Cage C., Vishwanatha J., Young R., Steele D. N., Carroll J. (2010). Self-reported racial discrimination, response to unfair treatment, and coronary calcification in asymptomatic adults—The North Texas Healthy Heart study. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 1–11. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-285/TABLES/4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M., Endlsey M., Motley D., Shawahin L. N., Williams M. T. (2018). Addressing the impact of racism on veterans of color: A race-based stress and trauma intervention. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 748–762. 10.1037/VIO0000221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105. 10.1177/0011000006292033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. T., Forsyth J. (2010). Reactions to racial discrimination: Emotional stress and help-seeking behaviors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(3), 183–191. 10.1037/A0020102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. T., Lau M. Y., Johnson V., Kirkinis K. (2017). Racial discrimination and health outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 45(4), 232–259. 10.1002/jmcd.12076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. T., Mazzula S., Victoria R., Vazquez R., Hall S., Smith S., Sant-Barket S., Forsyth J., Bazelais K., Williams B. (2013). Initial development of the Race-Based Traumatic Stress Symptom Scale: Assessing the emotional impact of racism. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(1), 1–9. 10.1037/a0025911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. T., Muchow C. (2017). Construct validity of the race-based traumatic stress symptom scale and tests of measurement equivalence. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(6), 688–695. 10.1037/tra0000256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R. T., Muchow C., Pieterse A. L. (2018). Construct, predictive validity, and measurement equivalence of the race-based traumatic stress symptom scale for black Americans. Traumatology, 24(1), 8–16. 10.1037/trm0000128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S. E., Gibbons F. X., Beach S. R. H. (2021). Measuring the biological embedding of racial trauma among Black Americans utilizing the RDoC approach. Development and Psychopathology, 33(5), 1849–1863. 10.1017/S0954579421001073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J. M. (2020). How to provide anti-racist mental health care. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(11), 929–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J. M. (2022). A letter from Ottawa, Canada (on Black Mental Health). The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(1), 19. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00471-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J. M., Dalexis R. D., Derivois D., Hébert M., Hajizadeh S., Kokou-Kpolou C. K., Guerrier M., Rousseau C. (2021). The Transcultural Community Resilience Scale: Psychometric properties and multinational validity in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, Article 3103. 10.3389/FPSYG.2021.713477/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J. M., Hajizadeh S., Dalexis R. D., Ndengeyingoma A., Guerrier M., Kogan C. (2022). Prevalence and effects of daily and major experiences of racial discrimination and microaggressions among Black individuals in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37, 16750–16778. 10.1177/08862605211023493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J. M., Kogan C., Noorishad P. G., Hajizadeh S., Dalexis R. D., Ndengeyingoma A., Guerrier M. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of depression among Black individuals in Canada: The major role of everyday racial discrimination. Depression and Anxiety, 38(9), 886–895. 10.1002/da.23158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J. M., McIntee S.-E., Mukunzi J. N., Noorishad P.-G. (2020). Overrepresentation of Black children in the child welfare system: A systematic review to understand and better act. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, Article 105714. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat J. M., Noorishad P.-G., Czechowski K., Mukunzi J. N., Hajizadeh S., McIntee S.-E., Dalexis R. D. (2021). The seven reasons why Black children are overrepresented in the child welfare system in Ontario (Canada): A qualitative study from the perspectives of caseworkers and community facilitators. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 10.1007/s10560-021-00793-6 [DOI]

- Chae D. H., Nuru-Jeter A. M., Adler N. E. (2012). Implicit racial bias as a moderator of the association between racial discrimination and hypertension: A study of midlife African American Men. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(9), 961–964. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182733665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Dueñas N. Y., Adames H. Y., Perez-Chavez J. G., Salas S. P. (2019). Healing ethno-racial trauma in Latinx immigrant communities: Cultivating hope, resistance, and action. American Psychologist, 74(1), 49–62. 10.1037/AMP0000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chioneso N. A., Hunter C. D., Gobin R. L., McNeil Smith S., Mendenhall R., Neville H. A. (2020). Community healing and resistance through storytelling: A framework to address racial trauma in Africana communities. Journal of Black Psychology, 46, 95–121. 10.1177/0095798420929468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64(3), 170–180. 10.1037/A0014564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L. (2016). Racial trauma recovery: A race-informed therapeutic approach to racial wounds. In Alvarez A. N., Liang C. T. H., Neville H. A. (Eds.), The cost of racism for people of color: Contextualizing experiences of discrimination (pp. 249–272). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/14852-012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L. (2020). Liberation psychotherapy. In Comas-Díaz L., Rivera E. Torres. (Eds.), Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice (pp. 169–185). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/0000198-010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L., Hall G. N., Neville H. A. (2019). Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 74(1), 1–5. 10.1037/amp0000442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway-Phillips R., Dagadu H., Motley D., Shawahin L., Janusek L. W., Klonowski S., Saban K. (2020). Qualitative evidence for Resilience, Stress, and Ethnicity (RiSE): A program to address race-based stress among Black women at risk for cardiovascular disease. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 48, Article 102277. 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A., Spinazzola J., Ford J., Lanktree C., Blaustein M., Cloitre M., DeRosa R., Hubbad R., Kagan R., Liautaud J., Mallah K., Olafson E., van der Kolk B. (2005). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois C. A. (2004). Complex trauma, complex reaction: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41(4), 412–425. 10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/uchclf1989&id=143&div=10&collection=journals

- David E. J. R., Schroeder T. M., Fernandez J. (2019). Internalized racism: A systematic review of the psychological literature on racism’s most insidious consequence. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1057–1086. 10.1111/josi.12350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado R., Stefancic J. (2018). Critical race theory (3rd ed.). NYU Press. 10.2307/j.ctt1ggjjn3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derivois D. (2017). Clinique de la mondialité: Vivre ensemble avec soi-même, vivre ensemble avec les autres [Globality as a Clinical Posture: Living together with oneself, living together with others]. De Boeck Supérieur. [Google Scholar]

- DiAngelo R. (2018). White fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dolezsar C. M., McGrath J. J., Herzig A. J. M., Miller S. B. (2014). Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: A comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychology, 33(1), 20–34. 10.1037/A0033718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez T. P., Dunkel-Schetter C., Glynn L. M., Hobel C., Sandman C. A. (2008). Racial differences in birth outcomes: The role of general, pregnancy, and racism stress. Health Psychology, 27(2), 194–203. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar-Ortiz R. (2019). An indigenous peoples’ history of the United States. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein K. K. (2005). The whitening of the American teaching force: A problem of recruitment or a problem of racism? Social Justice, 32(3), 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Essed P. (1991). Understanding everyday racism. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J. R. (2013). Systemic racism: A theory of oppression. Routledge. 10.4324/9781315880938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J. R., Bennefield Z. (2014). Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Social Science and Medicine, 103, 7–14. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V. J., Anda R. F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D. F., Spitz A. M., Edwards V., Koss M. P., Marks J. S., Perma-Nente K. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firmin J.-A. (2000). The equality of the human races. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Gabowitz D., Dawna Gabowitz A., Zucker M., Cook A. (2014). Neuropsychological assessment in clinical evaluation of children and adolescents with complex trauma. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1(2), 163–178. 10.1080/19361520802003822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G., Johnston-Guerrero M. (2016). Challenging the utility of a racial microaggressions framework through a systematic review of racially biased incidents on campus. Journal of Critical Scholarship on Higher Education and Student Affairs, 2(1), Article 4. https://ecommons.luc.edu/jcshesa/vol2/iss1/4 [Google Scholar]

- Gee G. C., Walsemann K. M., Brondolo E. (2012. a). A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 967–974. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobineau A. (1915). The inequality of human races. William Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S., Finkelhor D., Ormrod R., Turner H. (2005). The Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ): Administration and scoring manual. Crimes against Children Research Center University of New Hampshire. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell S. P. (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(1), 42–57. 10.1037/h0087722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris F. C., Lieberman R. C. (2015). Racial inequality after racism: How institutions hold back African Americans. Foreign Affairs, 94(2). https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2015-03-01/racial-inequality-after-racism [Google Scholar]

- Hart A. R., Lavner J. A., Carter S. E., Beach S. R. H. (2021). Racial discrimination, depressive symptoms, and sleep problems among Blacks in the rural South. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(1), 123–134. 10.1037/cdp0000365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms J. E., Nicolas G., Green C. E. (2010). Racism and ethnoviolence as trauma: Enhancing professional training. Traumatology, 16(4), 53–62. 10.1177/1534765610389595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R. B. (2004). Institutional racism in child welfare. Race and Society, 7(1), 17–33. 10.1016/j.racsoc.2004.11.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinsworth D. (2006). Race and racism in Australia. Thomson/Social Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hope E. C., Brinkman M., Hoggard L. S., Stokes M. N., Hatton V., Volpe V. V., Elliot E. (2021). Black adolescents’ anticipatory stress responses to multilevel racism: The role of racial identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(4), 487–498. 10.1037/ORT0000547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson D. L., Neighbors H. W., Geronimus A. T., Jackson J. S. (2015). Racial discrimination, John Henryism, and depression among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 42(3), 221–243. 10.1177/0095798414567757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isohookana R., Marttunen M., Hakko H., Riipinen P., Riala K. (2016). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on obesity and unhealthy weight control behaviors among adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 71, 17–24. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan M. M., Daniel J. H. (2011). Racial trauma in the lives of Black children and adolescents: Challenges and clinical implications. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 4(2), 123–141. 10.1080/19361521.2011.574678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan C. S., Noorishad P. G., Ndengeyingoma A., Guerrier M., Cénat J. M. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of anxiety symptoms among Black people in Canada: A significant role for everyday racial discrimination and racial microaggressions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 308, 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam E. G., Friedman M. J., Hill E. D., Kessler R. C., McLaughlin K. A., Petukhova M., Sampson L., Shahly V., Angermeyer M. C., Bromet E. J., De Girolamo G., De Graaf R., Demyttenaere K., Ferry F., Florescu S. E., Haro J. M., He Y., Karam A. N., Kawakami N., . . . Koenen K. C. (2014). Cumulative traumas and risk thresholds: 12-month PTSD in the world mental health (WMH) surveys. Depression and Anxiety, 31(2), 130–142. 10.1002/DA.22169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz R. S., Joseph J. (2014). Economic Inequality, racism and trauma: Growing up in racist combat zones and living in racist prisons. Journal of Pan African Studies, 7(6), 25–36. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269710097 [Google Scholar]

- Kendi I. X. (2017). Stamped from the beginning: A definitive history of racist ideas in America. Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Kendi I. X. (2019). How to be an anti-racist. One World. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkinis K., Pieterse A. L., Martin C., Agiliga A., Brownell A. (2021). Racism, racial discrimination, and trauma: A systematic review of the social science literature. Ethnicity and Health, 26(3), 392–412. 10.1080/13557858.2018.1514453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen S. A., Chirico D., O’Leary D. D., Cairney J., Wade T. J. (2016). Linking systemic arterial stiffness among adolescents to adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse and Neglect, 56, 1–10. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. T., Perez A. D., Boykin C. M., Mendoza-Denton R. (2019). On the prevalence of racial discrimination in the United States. PLOS ONE, 4(1), Article e0210698. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D. S., Himle J. A., Abelson J. M., Matusko N., Dhawan N., Taylor R. J. (2014). Discrimination and social anxiety disorder among African-Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and non-Hispanic Whites. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(3), 224–230. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. J., Koenen K. C., Ambler A., Arseneault L., Caspi A., Fisher H. L., Moffitt T. E., Danese A. (2021). Unravelling the contribution of complex trauma to psychopathology and cognitive deficits: A cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 219(2), 448–455. 10.1192/BJP.2021.57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo C. M., Fairbank J. A., Scurfield R. M., Ruch L. O., King D. W., Adams L. J., Chemtob C. M. (2001). Measuring exposure to racism: Development and validation of a Race-Related Stressor Scale (RRSS) for Asian American Vietnam veterans. Psychological Assessment, 13(4), 503–520. 10.1037/1040-3590.13.4.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markin R. D., Coleman M. N. (2021). Intersections of gendered racial trauma and childbirth trauma: Clinical interventions for Black women. Psychotherapy. Advance online publication. 10.1037/PST0000403 [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCormack L., Thomson S. (2017). Complex trauma in childhood, a psychiatric diagnosis in adulthood: Making meaning of a double-edged phenomenon. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(2), 156–165. 10.1037/tra0000193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metinyurt T., Haynes-Baratz M. C., Bond M. A. (2021). A systematic review of interventions to address workplace bias: What we know, what we don’t, and lessons learned. New Ideas in Psychology, 63, Article 100879. 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2021.100879 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger I. W., Anderson R. E., Are F., Ritchwood T. (2021). Healing interpersonal and racial trauma: Integrating racial socialization into trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for African American youth. Child Maltreatment, 26(1), 17–27. 10.1177/1077559520921457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger I. W., Salami T., Carter S., Halliday-Boykins C., Anderson R. E., Jernigan M. M., Ritchwood T. (2018). African American emerging adults? experiences with racial discrimination and drinking habits: The moderating roles of perceived stress. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(4), 489–497. 10.1037/cdp0000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnat S. M., Chandler R. F. (2015). Long-term physical health consequences of adverse childhood experiences. Sociological Quarterly, 56(4), 723–752. 10.1111/tsq.12107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouzon D. M., McLean J. S. (2017). Internalized racism and mental health among African-Americans, US-born Caribbean Blacks, and foreign-born Caribbean Blacks. Ethnicity and Health, 22(1), 36–48. 10.1080/13557858.2016.1196652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2018). Screening and assessment of complex trauma. https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/complex-trauma/screening-and-assessment

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2020). Complex trauma. https://www.nctsn.org/what-is-child-trauma/trauma-types/complex-trauma

- Nickerson A., Aderka I. M., Bryant R. A., Hofmann S. G. (2012). The relationship between childhood exposure to trauma and intermittent explosive disorder. Psychiatry Research, 197(1–2), 128–134. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunyemi D., Clare C., Astudillo Y. M., Marseille M., Manu E., Kim S. (2020). Microaggressions in the learning environment: A systematic review. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 13(2), 97–119. 10.1037/DHE0000107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y. (2006). A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(4), 888–901. 10.1093/ije/dyl056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H., Videlock E. J., Shih W., Presson A. P., Mayer E. A., Chang L. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences are associated with irritable bowel syndrome and gastrointestinal symptom severity. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 28(8), 1252–1260. 10.1111/nmo.12826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-beck W., Eni R., Lavoie J. G., Kinew K. A., Achan G. K., Katz A. (2020). Confronting racism within the Canadian Healthcare System: Systemic exclusion of first nations from quality and consistent care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), Article 8343. 10.3390/IJERPH17228343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiñones-Rosado R. (2020). Liberation psychology and racism. In Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice (pp. 53–68). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/0000198-004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson K., Carter R. T. (2022). The relationship between race-based traumatic stress and the Trauma Symptom Checklist: Does racial trauma differ in symptom presentation? Traumatology, 28(1), 120–128. 10.1037/trm0000306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rockich-Winston N., Taylor T. R., Richards J. A., White D. J., Wyatt T. R. (2021). “All Patients Are Not Treated as Equal”: Extending medicine’s social contract to Black/African American communities. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 34, 238–245. 10.1080/10401334.2021.1902816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saban K. L., Motley D., Shawahin L., Mathews H. L., Tell D., De La Pena P., Janusek L. W. (2021). Preliminary evidence for a race-based stress reduction intervention for Black women at risk for cardiovascular disease. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 58, Article 102710. 10.1016/J.CTIM.2021.102710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem F. T., Anderson R. E., Williams M. (2020). Addressing the “myth” of racial trauma: Developmental and ecological considerations for youth of color. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(1), 1–14. 10.1007/S10567-019-00304-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton E. K., Caldwell C. H., Sellers R. M., Jackson J. S. (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1288–1297. 10.1037/a0012747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton E. K., Carter R. (2020). Pubertal timing as a moderator between general discrimination experiences and self-esteem among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(3), 390–398. 10.1037/cdp0000305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw L. R., Chan F., McMahon B. T. (2012). Intersectionality and disability harassment: The interactive effects of disability, race, age, and gender. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 55(2), 82–91. 10.1177/0034355211431167 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sibrava N. J., Bjornsson A. S., Carlos A., Moitra E., Weisberg R. B., Keller M. B. (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder in African American and Latinx adults: Clinical course and the role of racial and ethnic discrimination. American Psychologist, 74(1), 101–116. 10.1037/AMP0000339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman R. W. (2014). The myth of race: The troubling persistence of an unscientific idea. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trent M., Dooley D. G., Dougé J., Trent M. E., Cavanaugh R. M., Lacroix A. E., Fanburg J., Rahmandar M. H., Hornberger L. L., Schneider M. B., Yen S., Chilton L. A., Green A. E., Dilley K. J., Gutierrez J. R., Duffee J. H., Keane V. A., Krugman S. D., McKelvey C. D., . . .Wallace S. B. (2019). The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics, 144(2), Article 20191765. 10.1542/PEDS.2019-1765/38466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R. L., Salami T. K., Carter S. E., Flowers K. (2014). Perceived racism and suicide ideation: Mediating role of depression but moderating role of religiosity among African American adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(5), 548–559. 10.1111/sltb.12089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace S., Nazroo J., Bécares L. (2016). Cumulative effect of racial discrimination on the mental health of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom. American Journal of Public Health, 106(7), 1294–1300. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F. W., Litz B. T., Keane T. M., Palmieri P. A., Marx B. P., Schnurr P. P. (2013). Life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) and criterion A. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_LEC_criterionA.PDF

- Williams D. R. (1999). Race, socioeconomic status, and health the added effects of racism and discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 173–188. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Mohammed S. A. (2013). Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1152–1173. 10.1177/0002764213487340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Yu Y., Jackson J. S., Anderson N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health. Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. T. (2020). Managing microaggressions: Addressing everyday racism in therapeutic spaces. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. T., Davis A. K., Xin Y., Sepeda N. D., Grigas P. C., Sinnott S., Haeny A. M. (2020). People of color in North America report improvements in racial trauma and mental health symptoms following psychedelic experiences. Prevention and Policy, 28(3), 215–226. 10.1080/09687637.2020.1854688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. T., Malcoun E., Sawyer B. A., Davis D. M., Nouri L. B., Bruce S. L. (2014). Cultural adaptations of prolonged exposure therapy for treatment and prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans. Behavioral Sciences, 4(2), 102–124. 10.3390/BS4020102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. T., Metzger I. W., Leins C., DeLapp C. (2018). Assessing racial trauma within a DSM–5 framework: The UConn Racial/Ethnic Stress & Trauma Survey. Practice Innovations, 3(4), 242–260. 10.1037/PRI0000076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. T., Printz D. M. B., DeLapp R. C. T. (2018). Assessing racial trauma with the trauma symptoms of discrimination scale. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 735–747. 10.1037/VIO0000212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. F., Clark L. F., Marlotte L. (2016). The impact of specific and complex trauma on the mental health of homeless youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(5), 831–854. 10.1177/0886260514556770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman G. M., Miller-Smith A. (2022). The impact of anticipated, vicarious, and experienced racial and ethnic discrimination on depression and suicidal behavior among Chicago youth. Social Science Research, 101, Article 102623. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zyromski B., Dollarhide C. T., Aras Y., Geiger S., Oehrtman J. P., Clarke H. (2018). Beyond complex trauma: An existential view of adverse childhood experiences. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 57(3), 156–172. 10.1002/johc.12080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]