Abstract

Objectives. To compare rural versus urban local public health workforce competencies and training needs, COVID-19 impact, and turnover risk.

Methods. Using the 2021 Public Health Workforce Interest and Needs Survey, we examined the association between local public health agency rural versus urban location in the United States (n = 29 751) and individual local public health staff reports of skill proficiencies, training needs, turnover risk, experiences of bullying due to work as a public health professional, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms attributable to COVID-19.

Results. Rural staff had higher odds than urban staff of reporting proficiencies in community engagement, cross-sectoral partnerships, and systems and strategic thinking as well as training needs in data-based decision-making and in diversity, equity, and inclusion. Rural staff were also more likely than urban staff to report leaving because of stress, experiences of bullying, and avoiding situations that made them think about COVID-19.

Conclusions. Our findings demonstrate that rural staff have unique competencies and training needs but also experience significant stress.

Public Health Implications. Our findings provide the opportunity to accurately target rural workforce development trainings and illustrate the need to address reported stress and experiences of bullying. (Am J Public Health. 2023;113(6):689–699. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307273)

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed considerable strain on the US public health workforce. High turnover of local health department (LHD) personnel has occurred, creating concern about workforce needs and capacity.1,2 These circumstances have compounded stressors that LHDs faced before the pandemic, including inadequate funding and support, insufficient staffing, and gaps in competencies for promoting community health.3–5 This strain has been particularly severe among rural LHDs through an historical lack of investment and limited workforce capacity relative to their urban counterparts.6 Rural LHDs provide essential community services, operating as safety net providers and engaging in population-based services. A deeper understanding of rural LHD workforce assets and needs is critical to providing effective support for strengthening our rural public health systems.7,8

The public health workforce—including nurses, environmental health professionals, epidemiologists, and others—engages in population-focused interventions, individual-level direct services, and policy development to protect the public’s health and reduce disparities.9 As public health systems have shifted efforts toward population-based services, required workforce competencies have also shifted: skills are needed in community engagement, cross-sectoral partnerships, systems thinking, and policy development, along with capacity to promote health equity.10–12 The pandemic further highlighted needs for data science and evaluation skills, which may be underdeveloped among rural LHDs.7,13 Research is needed to understand rural workforce competencies and gaps as part of supporting provision of more population-based services.14

Rural LHD personnel confront unique challenges in improving population health in communities with limited resources. Rural LHDs and their staff, compared with their urban neighbors, are the least well-resourced component of our public health systems, with less funding, fewer staff, and less training because funding often depends, in part, on an area’s tax base and local wealth.6 Rural LHDs also have smaller networks of organizations with whom to partner, further limiting their capacity, yet they serve communities with higher rates of risky behaviors and poor health outcomes than urban areas.8,15 Furthermore, rural LHDs tend to rely on clinical service revenue, complicating their ability to transition to providing more population-based services.8 Larger threats to LHD workforce supply and development may also exist, including geographical differences in staff turnover risk and the impact of COVID-19.

Previous LHD workforce research has been largely limited to medium-sized and large LHDs and overall has lacked rural–urban comparisons because of data limitations.4,16–19 For example, initial analyses from the 2021 Public Health Workforce Interest and Needs Survey (PH WINS) show that approximately 27% of respondents intended to leave their agency in the next year; it is unknown, however, how this differs between rural and urban staff.1 One study of local competency gaps examined rural–urban differences but focused on 1 state.16 Other studies exploring competencies and training needs have centered on or included state public health employees without sufficient attention to local jurisdictions.20–23 Furthermore, most studies exploring workforce competencies, training needs, intent to leave, and other outcomes using PH WINS have not incorporated additional LHD organizational factors such as leadership background (e.g., physician, nurse) or public health workforce supply. In this study, we aimed to fill these gaps by comparing rural versus urban LHD workforce competencies and training needs, COVID-19 impact, and turnover risk to enable targeted investments, training, and support for the rural LHD workforce to serve their communities.

METHODS

We compiled a national data set including individual-level LHD staff competencies, training needs, COVID-19 experiences, and staff turnover risk as well as LHD characteristics and county-level demographics. Individual-level staff variables came from the 2021 PH WINS, a nationally representative survey of individual state and local governmental public health staff administered by the de Beaumont Foundation and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials.1 The 2021 PH WINS was sent to 137 446 nonsupervisors (tier 1 staff), supervisors and managers (tier 2 staff), and executives (tier 3 staff) in 47 state health departments; 29 big city health departments; 497 LHDs in states with centralized, shared, or mixed public health governance; and 259 decentralized LHDs. The response rate for the national sample was 35% (n = 44 732). The same survey included respondents from the US Department of Health and Human Services Regions 5 (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin) and 10 (Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington) in the pilot program “PH WINS for All.” This pilot program collected PH WINS data through a census of all LHDs in these regions, including LHDs that had fewer than 25 full-time equivalent employees (FTEs), that served populations of fewer than 25 000, or both.24 These small LHDs had not been included previously in PH WINS. The methods for this census survey portion of PH WINS are described elsewhere,24 but these PH WINS data representing staff serving small population sizes are generally rural communities. Data on LHD organizational characteristics came from the 2019 National Profile of Local Health Departments Survey (hereafter called Profile) conducted by the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). We derived county demographic data from the 2020 Area Health Resource File (AHRF). We linked PH WINS and Profile data using NACCHO identifiers and AHRF data via county-level Federal Information Processing System (FIPS) codes.

Our data set included only LHD respondents to PH WINS (not state-level respondents). The final sample consisted of 29 751 tier 1–3 staff respondents from 742 LHDs.

Measures

Independent variables

The key independent variable was the rural–urban classification of respondents’ LHDs. “Urban” was the reference category in all regression analyses. We classified LHDs as rural or urban using 2019 Profile urban–rural designations for LHDs, based on the National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification scheme and frontier and remote area (FAR) codes.14 LHD characteristics included were whether the LHD director was a clinician (physician, nurse, dentist, veterinarian), whether the LHD was accredited by the Public Health Accreditation Board, and FTEs per 1000 population.25,26

Individual-level LHD staff indicators included public health practice tenure (0–5 years, > 5 years) and education level (master’s degree or higher, less than a master’s). County-level characteristics of the LHD’s jurisdiction included percentages of population unemployed, persons in poverty, and persons older than 25 years with less than a high school diploma, as well as percentages of Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native populations.

We examined other variables included in past PH WINS analyses and other research, such as whether an agency’s local board of health had policymaking authority and LHD staff respondents’ race, ethnicity, and age. Because their inclusion did not substantially affect our results, these variables were not retained in final models.

Dependent variables

We examined dependent variables measuring skills, training needs, COVID-19 impact, and turnover risk. Tier 1, 2, and 3 respondents reported proficiency in and importance of skills in their day-to-day work across 9 domains (e.g., “Data-Based Decision-Making” and “Effective Communication”; Figure 1). Skills and training needs were measured by staff tiers; all other outcomes were examined across all staff. Because of the small number of tier 3 respondents and the similar skills listed for tiers 2 and 3, we combined these tiers for each tier-based outcome (“tier 2/3”).

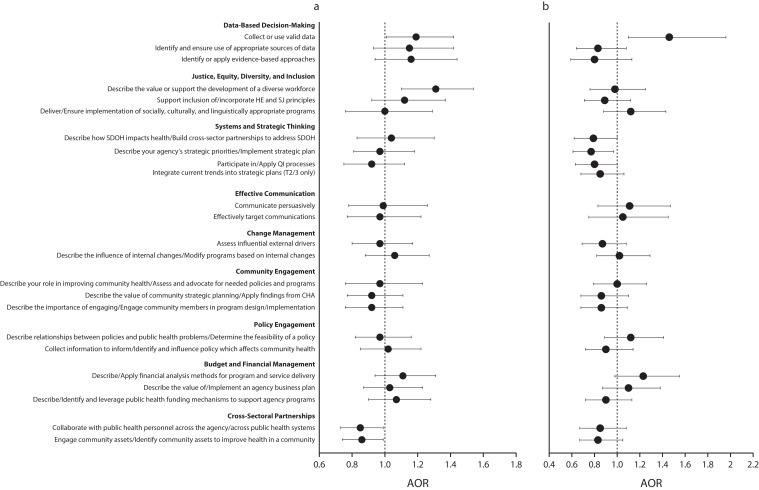

FIGURE 1—

Rural vs Urban Skill Proficiency Among Nonsupervisors and Supervisors/Executives in Local Health Departments by (a) Tier 1 Skill Proficiency and (b) Tier 2/3 Skill Proficiency: United States, 2021

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CHA = community health assessment; HE = health equity; QI = quality improvement; SDOH = social determinants of health; SJ = social justice. All results of the logistic regression are presented in their exponentiated form as odds ratios with urban as the reference category; AOR = 1.0 is not statistically significant. All outcomes are adjusted for local health department organizational variables (clinician-led, accreditation, full-time equivalent employees per 1000 population), staff variables (tenure, education level), and community-level variables (% unemployed, % in poverty, % older than 25 years with < high school diploma, % Black population, % Hispanic population, and % American Indian/Alaska Native population). Numerical values are available in Table C (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Skill names are abbreviated; full names are available in online Table C. Skills with a “/” indicate tier 1 and tier 2/3 wording; tier 2/3 wording follows the “/.”

Likert scales measured skill proficiency (0 = not applicable, 1 = unable to perform, 2 = beginner, 3 = proficient, 4 = expert) and importance (1 = not important, 2 = somewhat unimportant, 3 = somewhat important, 4 = very important). We transformed skill area variables (23 skills for tier 1 and 24 for tier 2/3) into binary variables (0 = unable to perform or beginner and 1 = proficient or expert). We excluded “not applicable” responses, which ranged from 5% to 15% depending on skill area. We defined “training need” to mean when respondents reported skills as “somewhat important” or “very important” to their day-to-day work and they reported their competency level for those skills as “unable to perform” or “beginner,” similar to how previous studies have defined training needs.18,19,23 We transformed training needs into binary variables (1 = high importance and low skill and 0 = all other combinations, e.g., high importance and high skill).

We assessed turnover risk by the question, “Are you considering leaving your organization in the next year?” Those reporting intentions to leave were asked to select among reasons. A separate question asked whether COVID-19 influenced their intention to leave. We examined turnover risk and influence of COVID-19 using binary variables, including intent to leave in the next year (excluding retirement), reasons for intending to leave, and feeling bullied, threatened, or harassed.

Two additional questions examined COVID-19 impact in terms of COVID-19 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and experiences of being bullied or harassed due to being a public health professional.1 Measures of PTSD symptoms used survey items from an existing primary care PTSD screen.1

Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics and used the χ2 test for bivariate analyses, evaluating significance at P < .01. We used multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess odds ratios of skill proficiency, training needs, turnover risk, and impact of COVID-19 for rural versus urban staff; skill proficiency and training needs were analyzed in separate tier 1 and tier 2/3 models. We constructed models using a phased approach, starting with bivariate associations between each outcome and rural–urban location followed by other staff, organizational, and community characteristics. We present fully adjusted models, displaying coefficients for all analyses, along with 95% confidence intervals, in exponentiated form.

Because our full PH WINS participant sample included census survey respondents from LHDs serving small populations or with small staffs, we did not use the balanced repeated replication weights included with the survey; inclusion of weights would have decreased our rural sample and removed small LHDs.24,27 Approximately 5000 PH WINS respondents did not have corresponding LHD Profile data. The proportions of rural and urban respondents missing Profile data were relatively similar (rural: 827 [20%]; urban: 4011 [16%]). We analyzed models with and without these respondents; results were not substantially different, and we included respondents with missing Profile data in our analyses. Sensitivity testing also included analyses using multilevel modeling techniques to account for clustering within and between LHDs; clustering at this level accounted for a small level of variance, with outcomes similar to those in the logistic regression analyses.

RESULTS

Most respondents self-identified as female, were 31 to 50 years old, had bachelor’s or lower degrees, and had worked in public health for 5 or more years (Table 1). In rural areas, 75% of respondents self-identified as White, a much larger proportion than urban staff (48%). Staffing relative to population size was higher in rural LHDs (0.9 FTEs per 1000 population) compared with urban LHDs (0.6 FTEs per 1000 population). More urban than rural LHDs were accredited (64% vs 32%). On average, a higher percentage of urban versus rural populations were at or below the federal poverty level according to US Census criteria (15% vs 12%), with lower median household incomes ($51 200 vs $65 000) and lower percentages identifying as Black (9% vs 12%) or Hispanic/Latinx (6% vs 10%).

TABLE 1—

Selected Local Health Department (LHD) Personnel and Organizational Characteristics and Community Demographics, Stratified by Rural–Urban Designation: United States, 2021

| Total, No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Rural, No. (%) or Mean ±SD | Urban, No. (%) or Mean ±SD | P | |

| LHD Personnel | ||||

| Total sample | 29 751 (100) | 4 845 (16) | 24 906 (84) | |

| Gender | < .001 | |||

| Male | 5 355 (18) | 662 (14) | 4 693 (19) | |

| Female | 23 518 (79) | 4 037 (83) | 19 481 (79) | |

| Nonbinary/other | 488 (2) | 77 (2) | 411 (2) | |

| Age, y | .1 | |||

| < 31 | 3 877 (13) | 588 (12) | 3 289 (15) | |

| 31–50 | 12 995 (44) | 2 077 (43) | 10 918 (44) | |

| ≥ 50 | 9 936 (33) | 1 708 (35) | 8 228 (33) | |

| Race/ethnicity | < .001 | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 276 (1) | 69 (1) | 207 (1) | |

| Asian | 1 810 (6) | 86 (2) | 1 724 (7) | |

| Black or African American | 4 327 (15) | 306 (6) | 4 021 (16) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 749 (19) | 504 (10) | 5 245 (21) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 95 (0.3) | 9 (0.2) | 86 (0.4) | |

| White | 15 484 (52) | 3 627 (75) | 11 857 (48) | |

| ≥ 2 races | 1 238 (4) | 132 (3) | 1 106 (4) | |

| Supervisory status | .001 | |||

| Nonsupervisor (tier 1) | 22 316 (75) | 3 704 (76) | 18 612 (75) | |

| Supervisor/manager (tier 2) | 6 700 (23) | 1 003 (21) | 5 697 (23) | |

| Executive (tier 3) | 735 (2) | 138 (3) | 597 (2) | |

| Education level | < .001 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree or less | 20 582 (69) | 3 788 (78) | 16 794 (67) | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 8 732 (29) | 985 (20) | 7 747 (31) | |

| Tenure in public health practice, y | .002 | |||

| 0–5 | 10 746 (36) | 1 846 (38) | 8 900 (36) | |

| ≥ 5 | 17 376 (58) | 2 711 (56) | 14 665 (59) | |

| LHD organizational characteristics | ||||

| Lead executive is a clinician | 10 812 (36) | 1 058 (22) | 9 754 (39) | < .001 |

| Accredited | 17 619 (59) | 1 572 (32) | 16 047 (64) | < .001 |

| Organizational Characteristics | ||||

| FTEs per 1000 populationa | 0.73 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 0.6 (1) | < .001 |

| Community demographics | ||||

| Population, 1000s | 238 (585) | 33 (23) | 410 (751) | < .001 |

| Median household income, $1000s | 59 (16) | 51 (10) | 65 (17) | < .001 |

| % persons at or below federal poverty levelb | 14 (5) | 15 (5) | 12 (4) | < .001 |

| % unemployed | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | < .001 |

| % > 25 y with < high school diploma | 8 (4) | 9 (4) | 7 (3) | < .001 |

| % Black | 11 (14) | 9 (15) | 12 (13) | < .001 |

| % American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (5) | 3 (6) | 1 (3) | <.001 |

| % Hispanic/Latinx | 8 (10) | 6 (8) | 10 (12) | < .001 |

Note. FTE = full-time equivalent employee; LHD = local health department.

This was calculated using LHD FTEs reported in the 2019 National Association of City and County Health Officials Profile of Local Health Departments survey and the 2020 population for that area (FTEs/population × 1000).

According to US Census criteria.

Distribution of Outcomes of Interest

Tier 1 (nonsupervisors) and tier 2/3 (supervisors and executives) rural staff reported lower proficiency than urban staff in corresponding tiers in almost all skills; training needs aligned with responses indicating low proficiency. A lower proportion of rural than urban staff reported an intention to leave in the next year for reasons other than retirement (19% vs 25%, respectively). However, higher proportions of rural than urban staff reported an intent to leave because of COVID-19 (18% vs 15%), being bullied or harassed because of their work as public health professionals (22% vs 16%), and avoiding situations that made them think about COVID-19 (a PTSD symptom; 40% vs 36%).1 Descriptive statistics regarding differences in rural versus urban responses to each skill, training need, intent to leave, and impact of COVID-19 are in Tables A and B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Regression

Skills and training needs

Figure 1 presents logistic regression results on reported skill proficiencies. When we controlled for staff-, organizational-, and community-level factors, tier 1 rural staff, compared with urban staff, had significantly higher odds of reporting proficiency in 2 of 3 skill areas within the Community Engagement domain: “Describe the value of community strategic planning” (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.17; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.01, 1.35) and “Describe the importance of engaging community members in program design and implementation” (AOR = 1.17; 95% CI = 1.01, 1.35; skill names are abbreviated; full names are available in online Table C). Similarly, tier 1 rural staff had greater odds of reporting proficiency in the 2 skill areas specific to Cross-Sectoral Partnerships: “Collaborate with public health personnel across the agency” (AOR = 1.22; 95% CI = 1.05, 1.41) and “Engage community assets to improve health in a community” (AOR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.07, 1.42). However, tier 1 rural staff had lower odds of reporting proficiency in the following skills: “Describe the value of a diverse workforce” (AOR = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.72, 0.99) and “Collect data for use in decision-making” (AOR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.71, 0.99). Tier 1 rural staff skill deficiencies or proficiencies tended to be consistent with the presence or absence of training needs; specifically, in skill areas where rural staff were more likely than urban staff to report proficiencies (e.g., cross-sectoral partnerships), they were less likely to report training needs and vice versa with regard to areas where they were less likely to report proficiencies (e.g., data for use in decision-making; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Rural vs Urban Training Needs Among Nonsupervisors and Supervisors/Executives in Local Health Departments by (a) Tier 1 Training Needs and (b) Tier 2/3 Training Needs: United States, 2021

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CHA = community health assessment; HE = health equity; QI = quality improvement; SDOH = social determinants of health; SJ = social justice. All results of the logistic regression are presented in their exponentiated form as odds ratios with urban as the reference category; AOR = 1.0 is not statistically significant. All outcomes are adjusted for local health department organizational variables (clinician-led, accreditation, full-time equivalent employees per 1000 population), staff variables (tenure, education level), and community-level variables (% unemployed, % in poverty, % older than 25 years with < high school diploma, % Black population, % Hispanic population, and % American Indian/Alaska Native population). Numerical values are available in Table C (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Skill names are abbreviated; full names are available in online Table C. Skills with a “/” indicate tier 1 and tier 2/3 wording; tier 2/3 wording follows the “/”.

In adjusted models, rural tier 2/3 staff had higher odds than urban staff of reporting proficiency in 7 of 24 skill areas (Figure 1). Similar to tier 1 rural staff, tier 2/3 rural staff had higher odds of reporting proficiency in 2 of 3 skill areas in the Community Engagement domains: “Engage community members in program design and implementation” (AOR = 1.27; 95% CI = 1.01, 1.60) and “Apply findings from a community health assessment” (AOR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.00, 1.59). Tier 2/3 rural staff also had significantly higher odds of reporting skill proficiency in 3 of 4 areas related to Systems and Strategic Thinking: “Create a culture of/Apply quality improvement processes” (AOR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.03, 1.64); “Implement/Ensure successful implementation of an organizational strategic plan” (AOR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.09, 1.71); and “Build cross-sector partnerships to address social determinants of health” (AOR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.08, 1.70). Furthermore, tier 2/3 staff were significantly less likely to have training needs in the latter 2 skill areas (AOR = 0.77 and 0.79, respectively; Figure 2). Skill proficiencies and training needs were also aligned in the Data-Based Decision-Making domain: rural tier 2/3 staff had significantly lower odds of reporting proficiency in “Use valid data” (AOR = 0.70; 95% CI = 0.53, 0.93) and significantly higher odds of having a training need in this area (AOR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.10, 1.55).

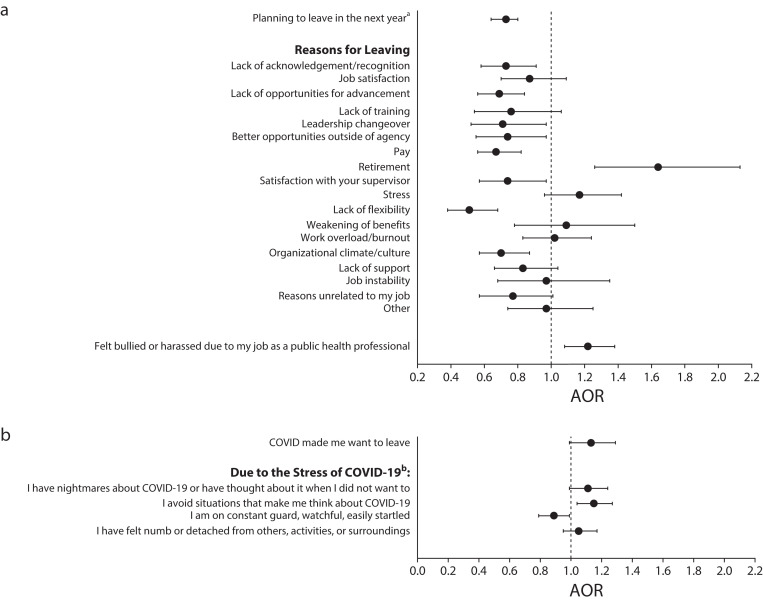

Turnover risk and COVID-19 impact

In logistic regression analyses of turnover risk and impact of COVID-19 (Figure 3), rural staff across all tiers were less likely than urban staff to report an intent to leave in the next year (AOR = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.64, 0.83). They were also less likely to report an intent to leave because of lack of acknowledgment or recognition (AOR = 0.73), lack of opportunities for advancement (AOR = 0.69), pay (AOR = 0.67), and lack of flexibility (AOR = 0.51). However, when we restricted the sample to staff intending to leave in the next year (excluding retirements, n = 7185), the odds of rural staff reporting an intent to leave because of stress were higher than those of urban staff (AOR = 1.29; 95% CI = 1.02, 1.60; results not shown); other relationships were unchanged in this analysis. The odds of rural participants reporting that they had been bullied or harassed because of their work were 1.22 times the odds for urban staff (95% CI = 1.04, 1.32). In addition, rural staff had higher odds than urban staff of reporting that they avoided situations that made them think about COVID-19 (AOR = 1.15; 95% CI = 1.04, 1.27).

FIGURE 3—

Regression Results Among Local Health Department Nonsupervisors, Supervisors, and Executives of (a) Rural vs Urban Intention to Leave and (b) Impact of COVID-19: United States, 2021

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio. All results are presented in their exponential form as AORs with urban as the reference category; AOR = 1.0 is not statistically significant. All outcomes are adjusted for local health department organizational variables (clinician-led, accreditation, full-time equivalent employees per 1000 population), staff variables (tenure, education level), and community-level variables (% unemployed, % in poverty, % older than 25 years with < high school diploma, % Black population, % Hispanic population, and % American Indian/Alaska Native population). Numerical values of AORs and confidence intervals can be found in Table D (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Results are presented at the total staff level (nonsupervisors, supervisors, and executives) rather than by staff tiers.

aExcludes retirement.

bPTSD screening tool. The lead-in for this question was: “Has the coronavirus or COVID-19 outbreak been so frightening, horrible, or unsettling that . . . .”

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide novel information regarding rural–urban differences in skills, training needs, turnover risks, and the impact of COVID-19 on the workforce. They also suggest areas of rural strength and concern. We found that compared with urban LHD staff, rural LHD staff reported greater proficiency in skills related to community engagement, cross-sectoral partnerships, and systems thinking, but had greater training needs in areas related to data-based decision-making and to justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. We also found that rural LHD staff were more likely than urban staff to report being harassed by individuals outside of their LHD because of their work. Despite harassment, rural staff were less likely than urban staff to report an intent to leave their organization. However, of staff reporting intentions to leave, rural participants were more likely to report stress as a reason for leaving; rural staff were also more likely to report avoiding situations reminding them of COVID-19, which is a PTSD symptom.

The rural–urban differences we identified highlight opportunities for public health workforce development. Rural staff proficiencies in community engagement, cross-sectoral partnerships, and systems and strategic thinking skills are important for accomplishing public health work—especially in rural communities3—providing an opportunity to build on these rural assets during staff trainings and offering lessons for urban LHDs. In addition, research examining general public health workforce capacity during and before the pandemic found training needs with regard to connecting effectively with populations that have negative perceptions of public health; our findings suggest that rural staff may be good resources in developing such training.28 Finally, previous research indicates that LHD directors with nursing backgrounds are skilled in communication, collaboration, and partnering with communities.14,26 Because many rural LHDs are led and staffed by nurses, our findings may reflect the presence of nurses and suggest the efficacy of nursing leadership, which has been found by others.14,26

At the same time, skill gaps among rural staff, such as those related to data-based decision-making and to justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion, point to priorities for focusing rural workforce development efforts. With respect to skill gaps in justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion, some rural communities have previously been predominantly White and relatively homogenous, but increasing rural diversity may be prompting rural staffs’ recognition of the need for these skills. The lack of diversity among rural staff themselves may also be contributing to, and prompting, this training need.3,15,29 Collectively, gaps in both data-based decision-making and justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion may have affected rural LHD staff’s preparedness for COVID-19 and contributed to their stress, because data collection and analysis as well as abilities to address diverse community needs were important skills needed during the pandemic.12,30,31 Given that rates of COVID-19 infections were high in rural areas, findings suggest that resources should be allocated to address known skill gaps, such as use of data in decision-making, and support growth of a more diverse workforce to enable rural staff to effectively serve marginalized members of increasingly diverse rural communities.30,32,33

Our findings also show that COVID-19 significantly affected rural staff, compounding prepandemic stressors from underfunding and inadequate workforce capacity.34 Along with greater odds of reporting skill gaps in areas essential for COVID-19 responsiveness, proportionally more rural staff reported wanting to leave because of COVID-19 and overload or burnout. Further, burnout and stress were the second and third most common reasons rural LHD staff listed for wanting to leave. This is in contrast to state and large- or medium-sized health department respondents in the 2017 PH WINS national sample survey, where the second and third most common reasons for wanting to leave were lack of opportunities for advancement and workplace environment.20 Our study highlights the impact of stress and COVID-19 on rural LHD staff as evidenced by their greater odds of wanting to leave because of stress, of avoiding situations that made them think about COVID-19, and of experiencing bullying or harassment. At the same time, even as they appear to have suffered greater stress and harassment than urban counterparts, rural staff had less intention to leave their job soon. Rural staffs’ reasons for intending to remain in their positions, despite notable challenges, deserve further investigation.

Limitations

Our cross-sectional design limits the ability to determine causality. We also lack data on numbers of staff that have left their jobs, limiting a comprehensive understanding of the pandemic’s impact and how turnover risk translates to actual turnover. Furthermore, skill proficiencies and training needs may look different if formally assessed rather than self-reported. Finally, the inability to incorporate weights because of our inclusion of small LHDs in Regions 5 and 10 may affect generalizability. Despite these limitations, evidence here regarding rural public health workers can inform important future workforce research.

Public Health Implications

Rural LHD staff face multiple pressures and changes to practice while grappling with the long-term impacts of COVID-19 and increasing diversity in their communities. Rural staff have also been challenged both to provide clinical services and to increase their focus on population-based services while responding to a pandemic. They do this work with limited resources, including inadequate funds and staffing.8,15 Our findings offer novel evidence regarding rural staff skills and training gaps, providing evidence for effectively supporting and strengthening this workforce to ensure readiness for future emergencies. Greater investment is needed in rural public health workforce development that is based on the assets and needs of rural staff and rural communities, including areas related to data collection and use.16,35 Opportunities also exist to leverage rural staff competencies in systems thinking and community partnership for the lessons they can offer urban LHD staff. Finally, this study highlights urgent needs to address turnover risk and reported stress, burnout, and experiences of bullying and harassment that have taken place during the pandemic, especially for rural staff. Ensuring a resilient, prepared, and thriving rural workforce is critical to equitably addressing community health needs and responding to future pandemics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $536 449 with zero percentage financed with nongovernmental sources. Data for this study were obtained from the Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey, a project supported through a collaboration of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) and the de Beaumont Foundation.

Note. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, the HRSA, HHS, or the US Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov. The use of the data does not imply ASTHO or the de Beaumont Foundation’s endorsement of the research, research methods, or conclusions contained in this report.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The University of Washington institutional review board deemed this study exempt.

See also Harris, p. 607.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Beaumont Foundation and Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. 2022. https://debeaumont.org/phwins/2021-findings

- 2. Smith MR, Weber L. Associated Press. 2020. https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-u-s-news-ap-top-news-ok-state-wire-ca-state-wire-8ea3b3669bccf8a637b81f8261f1cd78

- 3.Grimm B, Ramos AK, Maloney S, et al. The most important skills required by local public health departments for responding to community needs and improving health outcomes. J Community Health. 2022;47(1):79–86. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robin N, Castrucci BC, McGinty MD, Edmiston A, Bogaert K. The first nationally representative benchmark of the local governmental public health workforce: findings from the 2017 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S26–S37. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck AJ, Leider JP, Coronado F, Harper E. State health agency and local health department workforce: identifying top development needs. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(9):1418–1424. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leider JP, Meit M, McCullough JM, et al. The state of rural public health: enduring needs in a new decade. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(9):1283–1290. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekemeier B, Park S, Backonja U, Ornelas I, Turner AM. Data, capacity-building, and training needs to address rural health inequities in the Northwest United States: a qualitative study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8–9):825–834. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leider J, Henning-Smith C. Resourcing public health to meet the needs of rural America. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(9):1291–1292. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeSalvo K, Wang Y, Harris A, Auerbach J, Koo D, O’Carroll P. Public health 3.0: a call to action for public health to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:170017. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.170017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamatakis KA, Baker EA, McVay A, Keedy H. Development of a measurement tool to assess local public health implementation climate and capacity for equity-oriented practice: application to obesity prevention in a local public health system. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0237380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Academy of Medicine. Emerging Stronger From COVID-19: Priorities for Health System Transformation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brownson RC, Burke TA, Colditz GA, Samet JM. Reimagining public health in the aftermath of a pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(11):1605–1610. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogg‐Graham R, Graves E, Mays GP. Identifying value‐added population health capabilities to strengthen public health infrastructure. Milbank Q. 2022;100(1):261–283. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. 2019 National Profile of Local Health Departments . 2020.

- 15.Harris JK, Beatty K, Leider JP, Knudson A, Anderson AJ, Meit M. The double disparity facing rural local health departments. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37(1):167–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sainkhuu S, Cunha-Cruz J, Knerr S, Rogers M, Bekemeier B. Evaluation of training gaps among public health practitioners in Washington State. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(5):473–483. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leider JP, Sellers K, Owens-Young J, et al. Determinants of workplace perceptions among federal, state, and local public health staff in the US, 2014 to 2017. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1654. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFarlane TD, Dixon BE, Grannis SJ, Gibson PJ. Public health informatics in local and state health agencies: an update from the public health workforce interests and needs survey. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S67–S77. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeager VA, Balio CP, Kronstadt J, Beitsch LM. The relationship between health department accreditation and workforce satisfaction, retention, and training needs. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S113–S123. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogaert K, Castrucci BC, Gould E, et al. The Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (PH WINS 2017): an expanded perspective on the state health agency workforce. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S16–S25. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harper E, Castrucci BC, Bharthapudi K, Sellers K. Job satisfaction: a critical, understudied facet of workforce development in public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(suppl 6):S46–S55. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sellers K, Leider JP, Bogaert K, Allen JD, Castrucci BC. Making a living in governmental public health: variation in earnings by employee characteristics and work setting. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2019;25(suppl 2):S87–S95. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor HL, Yeager VA. Core competency gaps among governmental public health employees with and without a formal public health degree. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(1):20–29. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulik P, Leider JP, Rogers R, et al. PH WINS for all: the critical role of partnerships for engaging all local health departments in the Public Health Workforce Interest and Needs Survey. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2023;29(suppl 1):S48–S53. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bekemeier B, Grembowski D, Yang Y, Herting JR. Leadership matters: local health department clinician leaders and their relationship to decreasing health disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18(2):E1–E10. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318242d4fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kett PM, Bekemeier B, Herting JR, Altman MR. Addressing health disparities: the health department nurse lead executive’s relationship to improved community health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(2):E566–E576. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robins M, Leider J, Schaffer K, Gambatese M, Allen E, Hare Bork R. WINS 2021 Methodology Report. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2023;29(suppl 1):S35–S44. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zemmel DJ, Kulik PKG, Leider JP, Power LE. Public health workforce development during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a qualitative training needs assessment. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022;28(suppl 5):S263–S270. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rowlands D, Love H. The Avenue. 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/09/28/mapping-rural-americas-diversity-and-demographic-change

- 30.Czabanowska K, Kuhlmann E. Public health competences through the lens of the COVID‐19 pandemic: what matters for health workforce preparedness for global health emergencies. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(S1):14–19. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callaghan T, Lueck JA, Trujillo KL, Ferdinand AO. Rural and urban differences in COVID‐19 prevention behaviors. J Rural Health. 2021;37(2):287–295. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dearinger AT. COVID-19 reveals emerging opportunities for rural public health. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(9):1277–1278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dobis EA, McGranahan D. Amber Waves 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2021/february/rural-residents-appear-to-be-more-vulnerable-to-serious-infection-or-death-from-coronavirus-covid-19

- 34.Melvin SC, Wiggins C, Burse N, Thompson E, Monger M. The role of public health in COVID-19 emergency response efforts from a rural health perspective. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:200256. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.200256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Backonja U, Park S, Kurre A, et al. Supporting rural public health practice to address local-level social determinants of health across Northwest states: development of an interactive visualization dashboard. J Biomed Inform. 2022;129:104051. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2022.104051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]