Abstract

Objective

To compare demographic characteristics, clinical features, and outcomes of children hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza, or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 during their cocirculation 2021-2022 respiratory virus season.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using Colorado's hospital respiratory surveillance data comparing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-, influenza-, and RSV-hospitalized cases < 18 years of age admitted and undergoing standardized molecular testing between October 1, 2021, and April 30, 2022. Multivariable log-binomial regression modeling evaluated associations between pathogen type and diagnosis, intensive care unit admission, hospital length of stay, and highest level of respiratory support received.

Results

Among 847 hospitalized cases, 490 (57.9%) were RSV associated, 306 (36.1%) were COVID-19 associated, and 51 (6%) were influenza associated. Most RSV cases were <4 years of age (92.9%), whereas influenza hospitalizations were observed in older children. RSV cases were more likely to require oxygen support higher than nasal cannula compared with COVID-19 and influenza cases (P < .0001), although COVID-19 cases were more likely to require invasive mechanical ventilation than influenza and RSV cases (P < .0001). Using multivariable log-binomial regression analyses, compared with children with COVID-19, the risk of intensive care unit admission was highest among children with influenza (relative risk, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.22-3.19), whereas the risk of pneumonia, bronchiolitis, longer hospital length of stay, and need for oxygen were more likely among children with RSV.

Conclusions

In a season with respiratory pathogen cocirculation, children were hospitalized most commonly for RSV, were younger, and required higher oxygen support and non-invasive ventilation compared with children with influenza and COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, influenza, RSV, bronchiolitis, croup, respiratory infection

Acute respiratory tract infections from viral pathogens are one of the leading causes of hospitalization in children. Presentations can include croup, bronchiolitis, asthma exacerbations, and pneumonia, which can lead to more serious outcomes including respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome.1 Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza are viruses associated with some of the highest mortality in children.2 , 3 Children at risk include the very young (<2 years of age) and those with underlying medical conditions including immunocompromising conditions and prematurity.4, 5, 6 Since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, respiratory infections owing to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are being recognized as another important cause of morbidity in children. Since February 2022, which corresponds with the Omicron period, SARS-CoV-2-related hospitalizations have increased 5-fold in children <5 years of age.7

To date, there has been little direct comparison of the severity and clinical presentations of RSV and influenza with SARS-CoV-2 infection in hospitalized children, particularly during a time period in which all 3 pathogens were cocirculating. Understanding the impact of SARS-CoV-2 in children, relative to influenza and RSV, can help to inform the healthcare response during future respiratory seasons and optimize patient management. Therefore, the overall objectives of this study were to compare demographic characteristics, clinical features, and outcomes of children with RSV, influenza, or SARS-CoV-2 in hospitalized children.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of children hospitalized with RSV, SARS-CoV-2, or influenza using public health surveillance data collected by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment per the Colorado Board of Health reportable condition regulations. Colorado participates in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Emerging Infections Program (EIP) Respiratory Virus Hospitalization Surveillance Network (RESP-NET), which gathers data on laboratory-confirmed influenza, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 infections among hospitalized residents of the 5-county Denver metropolitan catchment area (Adams, Arapahoe, Denver, Douglas, and Jefferson counties), which is primarily suburban. We restricted our population to children admitted to Children's Hospital Colorado (CHCO) in Aurora, Colorado, from October 1, 2021, to April 30, 2022, during a time in which the SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants were circulating. CHCO is a large academic quaternary care center serving children in the Denver metropolitan area and greater Colorado area, and the 7 surrounding states and is the largest provider or pediatric care in the EIP catchment area. The main hospital campuses in Aurora and Colorado Springs, in conjunction with 6 satellite locations, have 560 beds and admit >15 000 inpatients per year.

The time period of evaluation in our study coincided with an institutional policy requiring all inpatients to undergo universal SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing on admission, using a combined RSV/influenza/SARS-CoV-2 platform. Our cohort included symptomatic and asymptomatic children who were hospitalized and underwent RSV/influenza/SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing, with ≥1 positive SARS-CoV-2, RSV, or influenza test within 14 days of admission or during admission. Subsequent admissions within 24 hours of a prior hospitalization were counted as a single admission, and encounters that were ≥14 days apart were counted as separate admissions. We excluded children who were >18 years of age at the time of admission, had a discharge diagnosis of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or were coinfected with influenza, RSV, or SARS-CoV-2. Cases with known coinfection of other viral respiratory pathogens were not excluded.

Testing sources could include mid-turbinate swabs, nasopharyngeal samples, nasal washes, tracheal aspirates, and bronchoalveolar lavage samples. PCR testing was conducted at the CHCO microbiology laboratory using the GeneXpert Xpress CoV-2/Flu/RSV (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA) or the Simplexa COVID-19 Direct and Flu A/B & RSV Direct (Diasorin Molecular, Cypress, CA); additional SARS-CoV-2 testing was conducted with the Abbott m2000 Real time assay (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL). Respiratory panel testing was conducted using the Biofire RP 2.1, which tests for SARS-CoV-2; adenovirus; coronaviruses HKU1, NL63, 229E, and OC43; human metapneumovirus; rhinovirus/enterovirus; RSV; influenza A, A/H1-2009, A/H3, and B; parainfluenza virus 1, 2, 3, and 4; Bordetella pertussis; and parapertussis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae; and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Per CHCO institutional protocol, respiratory panel testing was restricted to children with immunocompromising conditions, medical complexity including chronic pulmonary conditions, or children admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Trained abstractors conducted chart review according to established RESP-NET methods using standardized case report forms that included sociodemographic, clinical, vaccination, and other outcome data. SARS-CoV-2 and influenza vaccination status were obtained through the Colorado Immunization Information System state vaccine registry data and electronic health record (EHR) data abstraction, which incorporates parental report, and primary care provider outreach. An individual fully vaccinated against COVID-19 was defined as a child who was eligible for and received ≥2 doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and ≥2 weeks had elapsed since the second dose. A partially vaccinated individual was defined as a child who received only 1 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine or received a second dose within 2 weeks of the test date. Unvaccinated individuals were identified as not having received any SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Influenza vaccination status was defined as follows: a vaccinated individual was defined as a child ≥6 months of age who received ≥1 dose of influenza vaccine for a given season. An unvaccinated individual was defined as a child ≥ 6 months of age who did not receive any influenza vaccines for a given season. Underlying medical conditions were collected based on the CDC's RESP-NET protocols. Prematurity was defined (for children <2 years of age) as a gestational age of <37 weeks at birth. Viral coinfection was defined as detection of influenza, RSV, or SARS-CoV-2 and ≥1 additional respiratory virus aside from influenza, RSV, or SARS-CoV-2 in the 14 days before admission or 7 days after the date of admission. Bacterial coinfection was defined as the detection of a bacterial pathogen via culture from a normally sterile or respiratory (sputum or endotracheal) site from a specimen collected within 7 days of admission, per CDC RESP-NET criteria, in addition to the detection of influenza, RSV, or SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The main exposure was influenza, RSV, or SARS-CoV-2 infection based on PCR detection. The primary outcome of interest was ICU admission. Secondary outcomes of interest included final diagnosis, hospital length of stay, and highest level of respiratory support received. The study was approved for exemption from research by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (COMIRB #22-2211). Descriptive statistics were performed to describe the sample population's sociodemographic characteristics and clinical and diagnostic outcomes. Multivariable log-binomial regression modeling was used to evaluate the association between pathogen type and ICU admission, pneumonia and bronchiolitis diagnosis, hospital length of stay, and highest level of respiratory support received. Confounding variables that were assessed for use in model adjustment included age, sex, prematurity, immunocompromising conditions, chronic lung disease, and race/ethnicity. Regression models separately adjusted for confounding according to bivariate analysis (χ2 test P < .05; Fisher's exact test P < .05; Kruskal-Wallis test P < .05) and clinical relevance. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

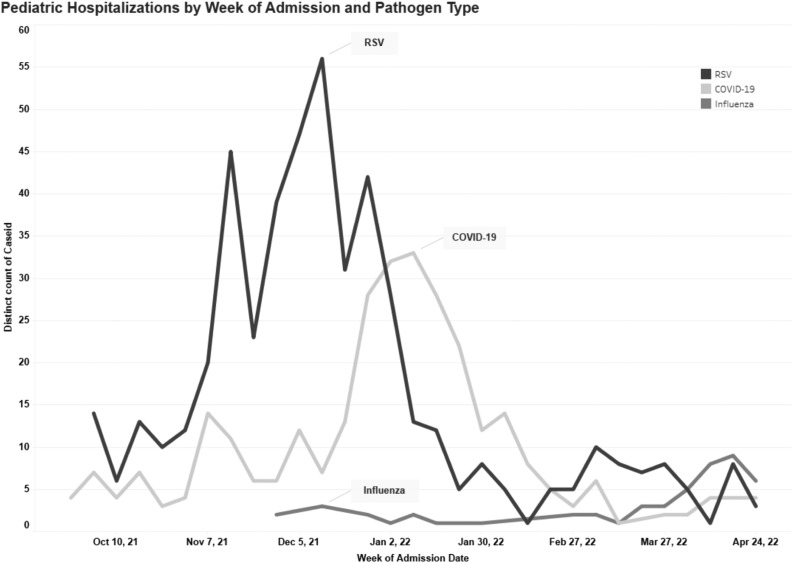

Among 1300 inpatient stays (representing 1260 children) at 2 hospitals between October 1, 2021, and April 30, 2022, within the EIP catchment area, 899 (867 children) had available data extracted from the electronic health record. Fifty-two coinfected cases (30 unique individuals) were excluded for analyses. The median age of these coinfected cases was 0.88 years (IQR, 0.54-2.86 years). Of the remaining cases, 490 (490 children) had RSV (57.9%), 306 (303 children) had SARS-CoV-2, and 51 (47 children) had influenza. The median age of children was 1.5 years (IQR, 0.4-4.1 years). The epidemic curve demonstrating the number of hospitalizations per week by pathogen is shown in the Figure . The peak of RSV, SARS-CoV-2, and influenza was in early December, early to mid-January, and April respectively. Table I demonstrates sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by pathogen. Children with RSV were younger (median age, 1 year) compared with SARS-CoV-2 (median age, 2.7 years) and influenza (median age, 6.1 years). A greater proportion of children with influenza were Hispanic/Latino/a/x (43.1%) compared with children with RSV (31.2%) and SARS-CoV-2 (35.3%; P = .0143). There was a greater proportion of children with private insurance with RSV infection (48.7%) compared with SARS-CoV-2 (32.3%) and influenza (29.8%). A higher proportion of children with influenza had ≥1 underlying medical condition, in particular chronic lung disease, neurological disorders, and obesity (60.8%), compared with children with RSV (36.5%) and SARS-CoV-2 (50.3%). Among hospitalized children with influenza with known vaccination status, 28 (68%) were either partially or fully vaccinated. Among children with SARS-CoV-2 infection, 36 (32.4%) were either partially vaccinated or received their primary series. Clinical outcomes of children with COVID-19 and influenza by vaccination status are summarized in Supplemental Tables I and II respectively in the Supplemental Material.

Figure.

Epidemic curve of RSV, influenza, and SARS-CoV-2 infections from hospitalized children in Colorado from October 1, 2021, to April 30, 2022. Line graphs represent number of cases by week. Black line represents RSV, medium grey line represents influenza, light grey line represents COVID-19.

Table I.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of children admitted to CHCO with RSV, influenza, or COVID-19 from October 1, 2021, to April 30, 2022

| Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics | All cases (n = 837) | RSV (n = 487 [58.2%]) | COVID-19 (n = 303 [36.2%]) | Influenza (n = 47 [5.6%]) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 1.5 (0.4-4.1) | 1.0 (0.2-2.4) | 2.7 (0.6-10.1) | 7.1 (2.9-9.6) | <.0001 |

| Age | <.0001 | ||||

| <6 months | 248 (29.6) | 183 (37.6) | 64 (21.1) | 1 (2.1) | |

| 6 months-1 year | 217 (25.9) | 146 (30.0) | 65 (21.5) | 6 (12.8) | |

| 2 years-4 years | 196 (23.4) | 123 (25.3) | 60 (19.8) | 13 (27.7) | |

| 5 years-11 years | 103 (12.3) | 30 (6.2) | 55 (18.2) | 18 (38.3) | |

| 12 years-17 years | 73 (8.7) | 5 (1.0) | 59 (19.5) | 9 (19.2) | |

| Female sex | 375 (44.8) | 213 (43.7) | 136 (44.9) | 26 (55.3) | .31 |

| Race/ethnicity | .03 | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 25 (3.0) | 19 (3.9) | 5 (1.7) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Black | 63 (7.5) | 30 (6.2) | 28 (9.2) | 5 (10.6) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 280 (33.4) | 153 (31.4) | 106 (35.0) | 21 (44.7) | |

| Multiracial | 15 (1.8) | 7 (1.4) | 7 (2.3) | 1 (2.1) | |

| White | 371 (44.3) | 226 (46.4) | 134 (44.2) | 11 (23.4) | |

| Unknown | 79 (9.4) | 51 (10.5) | 21 (6.9) | 7 (14.9) | |

| Insurance status | <.0001 | ||||

| Government Insurance | 461 (55.1) | 238 (48.9) | 191 (63.0) | 32 (68.1) | |

| Private | 350 (41.8) | 239 (49.1) | 98 (32.3) | 13 (27.7) | |

| Uninsured | 10 (1.2) | 3 (0.6) | 5 (1.7) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Unknown | 16 (1.9) | 7 (1.4) | 9 (3.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Underlying medical conditions | |||||

| At least 1 underlying medical condition | 358 (42.8) | 179 (36.8) | 152 (50.2) | 27 (57.5) | <.0001 |

| Prematurity | 97 (27.1) | 77 (43.0) | 19 (12.5) | 1 (3.7) | <.0001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 142 (39.7) | 60 (33.5) | 65 (42.8) | 17 (63.0) | .0084 |

| Asthma/RAD | 96 (26.8) | 37 (20.7) | 44 (29.0) | 15 (55.6) | .0005 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 12 (3.4) | 7 (3.9) | 5 (3.3) | 0 (0) | .57 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 29 (8.1) | 11 (6.2) | 16 (10.5) | 2 (7.4) | .34 |

| Oxygen dependent | 33 (9.2) | 19 (10.6) | 14 (9.2) | 0 (0) | .21 |

| Chronic metabolic disease | 23 (6.4) | 7 (3.9) | 15 (9.9) | 1 (3.7) | .07 |

| Blood disorders/hemoglobinopathy | 21 (5.9) | 9 (5.0) | 12 (7.9) | 0 (0) | .22 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 67 (18.7) | 36 (20.1) | 30 (19.7) | 1 (3.7) | .11 |

| Neurological disorder | 97 (27.1) | 38 (21.2) | 52 (34.2) | 7 (25.9) | .03 |

| Immunocompromised condition | 23 (6.4) | 4 (2.2) | 19 (12.5) | 0 (0) | .0003 |

| History of transplant | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) | .67 |

| Gastrointestinal/liver disease | 4 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) | .84 |

| Renal disease | 6 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (3.7) | .24 |

| Dialysis | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) | <.0001 |

| Rheumatologic condition | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) | .35 |

| Obesity | 24 (6.7) | 3 (1.7) | 17 (11.2) | 4 (14.8) | .0006 |

| Hypertension | 6 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 5 (3.3) | 1 (3.7) | .047 |

| Feeding tube dependent | 58 (16.2) | 25 (14.0) | 32 (21.1) | 1 (3.7) | .04 |

| Trach/vent dependent | 9 (2.5) | 5 (2.8) | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0) | .68 |

| Wheelchair dependent | 6 (1.7) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (3.3) | 0 (0) | .12 |

| Abnormality of airway | 22 (6.2) | 10 (5.6) | 12 (7.9) | 0 (0) | .26 |

| Chronic lung disease of prematurity | 29 (8.1) | 17 (9.5) | 11 (7.2) | 1 (3.7) | .52 |

Values are number (%) unless otherwise noted.

There was a greater proportion of asymptomatic children with SARS-CoV-2 (7.2%) compared with influenza (2.0%) and RSV (0.2%; P < .0001). Seventy percent of children with influenza presented with fever, compared with 56.9% of children with RSV. Children with SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to present with diarrhea (20.4%), headache (13.4%) and abdominal pain (18%) compared with children with RSV and influenza. Most children with RSV presented with respiratory symptoms (98.8%), compared with children with SARS-CoV-2 (81.3%) and influenza (84.0%) infection. Among children ≤2 years of age, children with SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to have stridor or decreased vocalization (16.9%), whereas children with RSV were more likely to present with inability to eat or poor feeding and dehydration.

Table II summarizes the outcomes of hospitalized children by pathogen. The most common reasons for admission varied by pathogen. Most children with RSV were diagnosed with bronchiolitis (69.2%), followed by pneumonia (16.1%), asthma exacerbation (8.8%), and acute respiratory failure (9.2%). Most children with COVID-19 were diagnosed with bronchiolitis (15.0%), acute respiratory failure (13.7%) and pneumonia (10.1%). The top 3 diagnoses for influenza were acute asthma exacerbation (21.6%), pneumonia (7.8%), and acute respiratory failure (7.8%).

Table II.

Diagnoses and clinical outcomes (encounter level) of children admitted to CHCO with RSV, influenza, or COVID-19 from October 1, 2021, to April 30, 2022

| Variables | All cases (n = 847) | RSV (n = 490 [57.9%]) | SARS-CoV-2 (n = 306 [36.1%]) | Influenza (n = 51 [6.0%]) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for admission | <.0001 | ||||

| Viral-related illness | 729 (86.1) | 473 (96.5) | 218 (71.2) | 38 (74.5) | |

| Other/Unknown | 118 (13.9) | 17 (3.5) | 88 (28.8) | 13 (25.5) | |

| Discharge Diagnosis | |||||

| Asthma exacerbation | 74 (8.7) | 43 (8.8) | 20 (6.5) | 11 (21.6) | <.0001 |

| Bronchiolitis | 390 (46.0) | 339 (69.2) | 46 (15.0) | 5 (9.8) | <.0001 |

| Bronchitis | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | .64 |

| Pneumonia | 114 (13.5) | 79 (16.1) | 31 (10.1) | 4 (7.8) | .03 |

| Acute encephalopathy | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | .25 |

| Seizures | 13 (1.5) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (2.9) | 3 (5.9) | <.0001 |

| Acute renal failure/AKI | 17 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 15 (4.9) | 2 (3.9) | <.0001 |

| ARDS | 5 (0.6) | 4 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | .75 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 91 (10.7) | 45 (9.2) | 42 (13.7) | 4 (7.8) | .10 |

| Sepsis | 8 (1.0) | 3 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) | 0 (0) | .38 |

| Coinfection with bacterial pathogens | 23 (12.4) | 2 (3.3) | 19 (7.1) | 2 (13.3) | .03 |

| Hospital length of stay median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.0 (2.0) | 3.0 (3.0) | 3.0 (2.0) | <.001 |

| Admitted to ICU | 231 (27.3) | 135 (27.6) | 79 (25.8) | 17 (33.3) | .52 |

| Received pressor support | 36 (4.3) | 10 (2.0) | 25 (8.2) | 1 (2.0) | <.0001 |

| Median ICU length of stay in days, (IQR) | 43.0 (2.0) | 3.0 (2.0) | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.0 (1.0) | <.0001 |

| Highest level of oxygen support | <.0001 | ||||

| ECMO | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 25 (3.0) | 5 (1.0) | 19 (6.2) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Positive pressure ventilation | 111 (13.1) | 91 (18.6) | 16 (5.2) | 4 (7.8) | |

| High flow | 135 (15.9) | 112 (22.9) | 21 (6.9) | 2 (3.9) | |

| Did not require high flow or ventilation support | 573 (67.7) | 281 (57.4) | 248 (81.1) | 44 (86.3) | |

| Died during hospitalization | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | .98 |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Values are number (%).

The median hospital length of stay was longer for children with RSV (4 days compared with 3 days for SARS-CoV-2 and influenza; P = .0009). ICU admission rates and length of stay were not significantly different, but children with SARS-CoV-2 more often received pressor support (8.2%) and invasive mechanical ventilation as their highest level of respiratory support (7.2%) compared with children with RSV and influenza (P < .001 for both). Among children admitted to the ICU, the median age was 1.86 years (IQR, 0.44-5.96 years) for SARS-CoV-2, 6.09 years (IQR, 2.05-8.68 years) for influenza, and 0.56 years (IQR, 0.11-1.61 years) for RSV. Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (18.6%) and high-flow use (22.9%) were highest in children with RSV (P < .0001). In our cohort, there were 2 deaths among children with RSV, 1 death in a child with SARS-CoV-2, and no deaths among children with influenza. The ages of the fatalities were 0.51 years, 2.56 years, and 0.95 years of age. Two of the 3 had underlying conditions (chronic metabolic disease, blood disorder, neurological disorder, renal disorder, prematurity).

There were 30 children with coinfection, including 20 children with COVID-19 and RSV coinfections, 3 children with COVID-19 and influenza coinfections, 2 children with influenza and RSV coinfections, and 1 child with COVID-19, RSV, and influenza coinfection. Children with influenza had a higher prevalence of bacterial coinfection (13.3%) compared with COVID-19 (7.1%) and RSV (3.3%).

Table III presents multivariable log-binomial regression analyses, with COVID-19 as the reference group. The risk of ICU admission was higher among children with influenza (relative risk [RR], 1.97; 95% CI, 1.22-3.19). The risk of pneumonia (RR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.54-3.52) and bronchiolitis (RR, 2.93; 95% CI, 2.28-3.78) was higher among children with RSV. A hospital length of stay of >4 days (RR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.12-1.76) and higher oxygen support (RR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.54-2.63) were also more likely among children with RSV.

Table III.

Multivariable log-binomial regression results of outcomes associated with children admitted to CHCO with RSV, influenza, or COVID-19 from October 1, 2021, to April 30, 2022, (n = 847)

| Outcomes | Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI (P value) | RR | 95% CI (P value) | |

| ICU admission∗ | ||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 1.0 (ref) | - | 1.0 (ref) | - |

| RSV | 1.07 | 0.84-1.35 (0.59) | 0.85 | 0.66-1.09 (0.19) |

| Influenza | 1.29 | 0.84-1.99 (0.25) | 1.97 | 1.22-3.19 (0.01) |

| Pneumonia diagnosis† | ||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 1.0 (ref) | - | 1.0 (ref) | - |

| RSV | 1.60 | 1.09-2.37 (0.018) | 2.32 | 1.54-3.52 (<.0001) |

| Influenza | 0.77 | 0.28-2.09 (0.61) | 1.05 | 0.39-2.85 (0.92) |

| Bronchiolitis diagnosis‡ | ||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 1.0 (ref) | - | 1.0 (ref) | - |

| RSV | 4.62 | 3.51-6.06 (<.0001) | 2.93 | 2.28-3.78 (<.0001) |

| Influenza | 0.65 | 0.27-1.56 (0.33) | 1.10 | 0.49-2.48 (0.82) |

| Hospital length of stay >4 days§ | ||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 1.0 (ref) | - | 1.0 (ref) | - |

| RSV | 1.31 | 1.06-1.62 (0.012) | 1.40 | 1.12-1.76 (0.00) |

| Influenza | 0.76 | 0.44-1.32 (0.33) | 0.91 | 0.51-1.62 (0.75) |

| High-flow oxygen support or mechanical ventilation (noninvasive and invasive)¶ | ||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 1.0 (ref) | - | 1.0 (ref) | - |

| RSV | 2.25 | 1.75-2.90 (<.0001) | 2.01 | 1.54-2.63 (<.0001) |

| Influenza | 0.72 | 0.35-1.50 (0.38) | 1.17 | 0.58-2.36 (0.66) |

ICU admission adjusted for prematurity, immunocompromised condition, and race/ethnicity.

Pneumonia diagnosis adjusted for CLD, and race/ethnicity.

Bronchiolitis diagnosis adjusted for prematurity, CLD, and neurological condition.

Hospital length of stay >4 days adjusted for prematurity and bacterial coinfection.

High-flow oxygen support or greater adjusted for prematurity and bacterial coinfection.

Discussion

In our retrospective study evaluating hospitalized children in Colorado with SARS-CoV-2, RSV, and influenza infections undergoing standardized molecular testing for these pathogens, we found that the greatest disease burden was for RSV, representing the greatest proportion of hospitalizations, longest median hospital length of stay and the highest need for respiratory support. Most children with RSV were <2 years of age, with a diagnosis of bronchiolitis, consistent with prior studies.8, 9, 10

Children with influenza were more likely to be febrile, and of school-age, with a higher prevalence of seizure diagnosis. Although children with influenza were admitted more commonly to the ICU, children with SARS-CoV-2 infection had a higher need for critical care support, including the need for vasopressors, invasive mechanical ventilation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

The need for diagnostic testing in children with respiratory symptoms to confirm infection with a particular virus has been debated.11, 12, 13, 14 However, with known treatments for influenza and SARS-CoV-2 and the possibility of future therapeutics for RSV, differentiating between these pathogens is important for children presenting with severe disease and/or those at high risk for complications who would warrant therapy. There were notable differences in disease presentation in our study. Children with RSV were more likely to present with congestion, cough, and shortness of breath and children with RSV <2 years of age were more likely to present with dehydration and/or poor feeding compared with those with SARS-CoV-2 or influenza. Children with influenza were more likely to be febrile and experience nausea and vomiting. In terms of clinical diagnosis, children with RSV more commonly had bronchiolitis, children with SARS-CoV-2 more commonly experienced acute respiratory failure, and children with influenza were more commonly diagnosed with seizures compared with the other viruses. In terms of demographic characteristics and comorbidities, children hospitalized with RSV were significantly younger than those with SARS-CoV-2 or influenza and were more likely to have no underlying medical conditions. Despite these important differences, however, there was a high degree of overlap in all of these categories, making a specific clinical diagnosis between these viruses challenging without testing, highlighting the need for sensitive and specific testing when treatment decisions are needed.

Our results demonstrated a longer hospital median length of stay for RSV (4 days) compared with influenza and SARS-CoV-2 (3 days). This median length of stay is slightly longer than prepandemic studies and another recent comparative study, which found a median length of stay of 3 days for RSV and SARS-CoV-2 and 2 days for influenza in a large cohort of pediatric patients from 11 states.15 , 16 These differences can likely be explained by the latter study, limiting their population to children ages 5-11 years old, excluding the youngest children at highest risk for severe disease. Another factor that may contribute to a longer length of stay in our study may include higher altitude, known to be associated with increased need for oxygen support to maintain saturations of >90% and increased morbidity.17

Similar to other studies, we also found a higher percentage of children hospitalized with RSV requiring some form of oxygen support, but a higher percentage of children with SARS-CoV-2 required invasive mechanical ventilation and a higher percentage of children with influenza required ICU admission, suggesting the overall potential for these viruses to cause severe disease.18 Our findings differ from another study comparing the clinical characteristics of adults and children by respiratory pathogen, which demonstrated relatively higher disease burden (30- day mortality, ICU admission) among adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with other respiratory viruses. These findings highlight important differences in how these pathogens present in children compared with adults.18

Owing to our standardized testing practice, we were able to explore the percentage of hospitalized children who tested positive for each of these viruses who were asymptomatic. Not surprisingly, the highest percentage of asymptomatic patients were found in SARS-CoV-2 positive patients. In line with other studies in pediatric patients, close to 7% of patients with SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, supporting testing guidelines of asymptomatic patients during SARS-CoV-2 activity to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during times of known high circulation.19 , 20 Furthermore, in alignment with other studies that have demonstrated low rates of asymptomatic RSV and influenza infections,21 only 0.2% of RSV infections and 1.8% of influenza infections were asymptomatic at the time of detection.21

In our cohort, among children with known vaccination status, 32% of hospitalized children with influenza were not vaccinated and two-thirds of hospitalized children with SARS-CoV-2 were unvaccinated. Previous studies have shown both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are protective against severe disease in children.15 , 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Our study highlights the lower vaccination rates in our pediatric population and the need for improved strategies to increase vaccination rates for these pathogens in children. Furthermore, based on decreased uptake of existing vaccines, our findings also are relevant given the likely availability in the near future of monoclonal antibodies for infants and RSV vaccines for pregnant women and older adults.

As SARS-CoV-2 moves from the pandemic phase towards an endemic/epidemic phase, there is the potential for the virus to adopt a seasonal pattern similar to other endemic coronaviruses, resulting in co-circulation with RSV and influenza during the winter months.27 , 28 Respiratory season planning will, therefore, need to account for the additional burden of SARS-CoV-2. This added burden from SARS-CoV-2 may result in additional strain on pediatric healthcare systems that are already stressed during regular respiratory season months. Our study provides useful insights into the burden of disease from these respiratory pathogens during times of cocirculation, and how these manifestations differ by pathogen. Such studies can provide useful data to inform health system staffing and resource allocation, as well as institutional policies.

Our study strengths include a cohort of hospitalized patients who underwent universal testing for these 3 pathogens, which provides unique insight into the clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized children, without the risk of testing bias, and enables some exploration of coinfections with these 3 pathogens. We used an established systematic chart abstraction process using standardized data collection from the CDC RESP-NET case report forms, including detailed information on symptoms, demographics, clinical presentation, and outcomes. This careful chart abstraction also enabled determination whether hospitalization was a direct result of viral infection, rather than an incidental finding. Last, using RESP-NET enabled a rapid chart abstraction process and evaluation of these respiratory viral pathogen data.

There are several limitations of this study that warrant discussion. First, our data are retrospective and limited to a single center. Therefore, the applicability of the findings presented herein to other populations and seasons is unknown. Our analysis was limited to hospitalized children and, therefore, does not represent the full spectrum or burden of disease from these pathogens. We were unable to provide population-based estimates of disease burden. Next, our data captured hospitalization data from children with these 3 pathogens and did not include other viral pathogens such as rhinovirus, which is known to be a common cause of hospitalization in children. Finally, our dataset was limited to the Colorado EIP catchment area, which encompasses 5 counties in the Denver metropolitan area; thus, the overall numbers of children in each group are small, precluding more advanced statistical analyses.

In a season with pathogen co-circulation of RSV, influenza and SARS-CoV-2, hospitalizations were primarily RSV associated, predominantly owing to respiratory illnesses, with requirements for higher levels of oxygen and noninvasive respiratory support compared with the needs of children with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza. Although ICU admission rates were similar across all 3 pathogens, a greater proportion of children with SARS-CoV-2 required pressor support and invasive mechanical ventilation. Given the likely seasonal co-circulation of these pathogens, ongoing comparison of their clinical characteristics and evaluation of their overall disease burden is essential to optimize treatment and prevention strategies.

Declaration of Competing Interest

S. R. reports prior grant support from GSK and Biofire and is a former consultant for Sequiris.

S. R. D. reports grant support from Biofire and Pfizer and is a consultant for Biofire and Karius.

The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors do not necessarily represent the official position of the state of Colorado, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' institutions.

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through an Emerging Infections Program cooperative agreement (grant CK17-1701). A.T. is supported by grant number K08HS026512 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the chart abstractors at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, members of the CHCO clinical microbiology laboratory who performed all the clinical testing, and Debashis Ghosh, PhD, Professor of Biostatistics and Informatics at the University of Colorado School of Public Health for his advice on statistical analyses.

Appendix

References

- 1.Orloff K.E., Turner D.A., Rehder K.J. The current state of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2019;32:35–44. doi: 10.1089/ped.2019.0999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen C.L., Chaves S.S., Demont C., Viboud C. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the US, 1999-2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson W.W., Shay D.K., Weintraub E., Brammer L., Cox N., Anderson L.J., et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:179–186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommer C., Resch B., Simoes E.A. Risk factors for severe respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infection. Open Microbiol J. 2011;5:144–154. doi: 10.2174/1874285801105010144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzpatrick T., McNally J.D., Stukel T.A., Lu H., Fisman D., Kwong J.C., et al. Family and child risk factors for early-life RSV illness. Pediatrics. 2021;147 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grohskopf L.A., Alyanak E., Ferdinands J.M., Broder K.R., Blanton L.H., Talbot H.K., et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices, United States, 2021-22 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep) 2021;70:1–28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7005a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks K.J., Whitaker M., Agathis N.T., Anglin O., Milucky J., Patel K., et al. Hospitalization of infants and children aged 0-4 Years with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 - COVID-NET, 14 states, march 2020-february 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:429–436. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7111e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall C.B., Simoes E.A., Anderson L.J. Clinical and epidemiologic features of respiratory syncytial virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;372:39–57. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall C.B., Weinberg G.A., Blumkin A.K., Edwards K.M., Staat M.A., Schultz A.F., et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalizations among children less than 24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e341–e348. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall C.B., Weinberg G.A., Iwane M.K., Blumkin A.K., Edwards K.M., Staat M.A., et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCulloh R.J., Andrea S., Reinert S., Chapin K. Potential utility of multiplex amplification respiratory viral panel testing in the management of acute respiratory infection in children: a retrospective analysis. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2014;3:146–153. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pit073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mattila S., Paalanne N., Honkila M., Pokka T., Tapiainen T. Effect of point-of-care testing for respiratory pathogens on antibiotic use in children: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao S., Lamb M.M., Moss A., Mistry R.D., Grice K., Ahmed W., et al. Effect of rapid respiratory virus testing on antibiotic prescribing among children presenting to the Emergency Department with acute respiratory illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lagace-Wiens P., Bullard J., Cole R., Van Caeseele P. Seasonality of coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses in Canada: implications for COVID-19. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2021;47:132–138. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v47i03a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldstein L.R., Ogokeh C., Rha B., Weinberg G.A., Staat M.A., Selvarangan R., et al. Vaccine effectiveness against influenza hospitalization among children in the United States, 2015-2016. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10:75–82. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun C., Lowe S., Wei B. Did we forget that masks, lockdowns, and other nonpharmaceutical interventions also play a role in respiratory viral disease? JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:825–826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choudhuri J.A., Ogden L.G., Ruttenber A.J., Thomas D.S., Todd J.K., Simoes E.A. Effect of altitude on hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Pediatrics. 2006;117:349–356. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedberg P., Karlsson Valik J., van der Werff S., Tanushi H., Requena Mendez A., Granath F., et al. Clinical phenotypes and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2, influenza, RSV and seven other respiratory viruses: a retrospective study using complete hospital data. Thorax. 2022;77:154–163. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-216949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaythorpe K.A.M., Bhatia S., Mangal T., Unwin H.J.T., Imai N., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., et al. Children's role in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of early surveillance data on susceptibility, severity, and transmissibility. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92500-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Overview of Testing for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/testing-overview.html#:∼:text=Based%20on%20evolving%20evidence%2C%20CDC,suspected%20or%20confirmed%20COVID%2D19 Accessed February 14, 2023.

- 21.Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health Study G Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet. 2019;394:757–779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30721-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan S.H.X., Cook A.R., Heng D., Ong B., Lye D.C., Tan K.B. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 vaccine against omicron in children 5 to 11 Years of age. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2203209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorabawila V., Hoefer D., Bauer U.E., Bassett M.T., Lutterloh E., Rosenberg E.S. Risk of infection and hospitalization among vaccinated and unvaccinated children and adolescents in New York after the Emergence of the omicron variant. JAMA. 2022;327:2242–2244. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.7319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segaloff H.E., Leventer-Roberts M., Riesel D., Malosh R.E., Feldman B.S., Shemer-Avni Y., et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization in fully and partially vaccinated children in Israel: 2015-2016, 2016-2017, and 2017-2018. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:2153–2161. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blyth C.C., Cheng A.C., Crawford N.W., Clark J.E., Buttery J.P., Marshall H.S., et al. The impact of new universal child influenza programs in Australia: vaccine coverage, effectiveness and disease epidemiology in hospitalised children in 2018. Vaccine. 2020;38:2779–2787. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalligeros M., Shehadeh F., Mylona E.K., Dapaah-Afriyie C., van Aalst R., Chit A., et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-associated hospitalization in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38:2893–2903. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belongia E.A., Osterholm M.T. COVID-19 and flu, a perfect storm. Science. 2020;368:1163. doi: 10.1126/science.abd2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Looi M.K. Covid-19: is a second wave hitting Europe? BMJ. 2020;371:m4113. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.