ABSTRACT

Staphylococcus aureus bears a type 7b secretion system (T7bSS) that assembles in the bacterial envelope to promote the secretion of WXG-like proteins and toxic effectors bearing LXG domains. Cognate immunity proteins bind cytosolic effectors to mute their toxicity prior to secretion. T7b-secreted factors have been associated with the pathogenesis of staphylococcal disease and intraspecies competition. We identified earlier strain WU1, an S. aureus ST88 isolate that caused outbreaks of skin and soft tissue infections in mouse breeding facilities. WU1 was also found to persistently colonize the nasopharynx of animals, suggesting a strong host adaptation. In this manner, WU1 colonization and infectivity in mice resembles that of methicillin-sensitive and -resistant S. aureus strains in humans, where nasal carriage is a major risk factor for invasive infections. Here, animals were colonized with wild-type or T7-deficient WU1 strains or combinations thereof. Absence of the T7bSS did not affect colonization in the nasopharynx of animals, and although fluctuations were observed in weekly samplings, the wild-type strain did not replace the T7-deficient strain in cocolonization experiments. Bloodstream infection with a T7b-deficient strain resulted in enhanced survival and reduced bacterial loads and abscesses in soft tissues compared to infection with wild-type WU1. Together, experiments using a mouse-adapted strain suggest that the T7bSS of S. aureus is an important contributor to the pathogenesis of invasive disease.

KEYWORDS: Staphylococcus aureus, type 7 secretion system, bloodstream infections, colonization, polymorphic toxins

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive bacterium that can be found in the environment, yet humans represent its natural habitat. Between 20% and 41% of the human population is colonized with S. aureus while the remaining is intermittently colonized (1). S. aureus primarily occupies the anterior nasal vestibule (vestibulum nasi) and axillae but is also commonly isolated from the oropharynx and gastrointestinal tract, which may serve as reservoirs or intermediate organs for the spread to new hosts (2–4). Nasal colonization occurs during the first days of life with maternal transmission accounting for up to 80% of colonized infants (5–7). After birth, horizontal transmission and colonization with S. aureus is thought to occur through contact with colonized individuals or contaminated surfaces (8, 9). Nasal colonization raises the risk for infections, and strains isolated from infection sites are often indistinguishable from the colonizing strain (10, 11). Only 6.6% of individuals carry more than one S. aureus strain in their nares (12) and infections with more than one strain are highly uncommon (13, 14).

In S. aureus, the specialized type 7b secretion system (T7bSS), known as ESAT-6-like secretion system (ESS), has been linked to bacterial antagonism (15, 16). The T7bSS is encoded within the ESS genomic locus, which specifies a translocation apparatus (translocon) comprised of membrane proteins, EsaA, EssA, and EssB, and the ATPase EssC (17, 18), small secreted proteins EsxA, EsxB, EsxC, EsxD belonging to the WXG100 family of proteins (19–21), and a large secreted LXG polymorphic toxin (EssD, also named EsaD) with its cognate immunity factor often referred to as antitoxin (22, 23) (Fig. 1A). A second LXG polymorphic toxin, TspA, is encoded outside the ESS locus (16). The LXG domain has been proposed to serve as a secretion module that is appended to various toxin-bearing domains (24, 25). EssD is endowed with nonspecific double-stranded DNA nuclease activity (15, 23) while TspA displays membrane depolarizing activity (16). In the cell cytosol, EssD and TspA interact with cognate immunity factors EssI (also named EsaG) and TsaI, respectively, to prevent self-intoxication (15, 16, 23). Sequence variability starting at the 3′ end of essC defines four kinds of ESS clusters in S. aureus (26). Sequence diversity extends to the downstream genes encoding the EssD product along with several copies of immunity (antitoxin) proteins (EssI) which led to the hypothesis that T7bSS could mediate bacterial antagonism (24, 27). In S. aureus, such antagonism has been reported between wild type and T7b- or LXG-defective strains in vitro and in vivo using a zebrafish model of infection (15, 16).

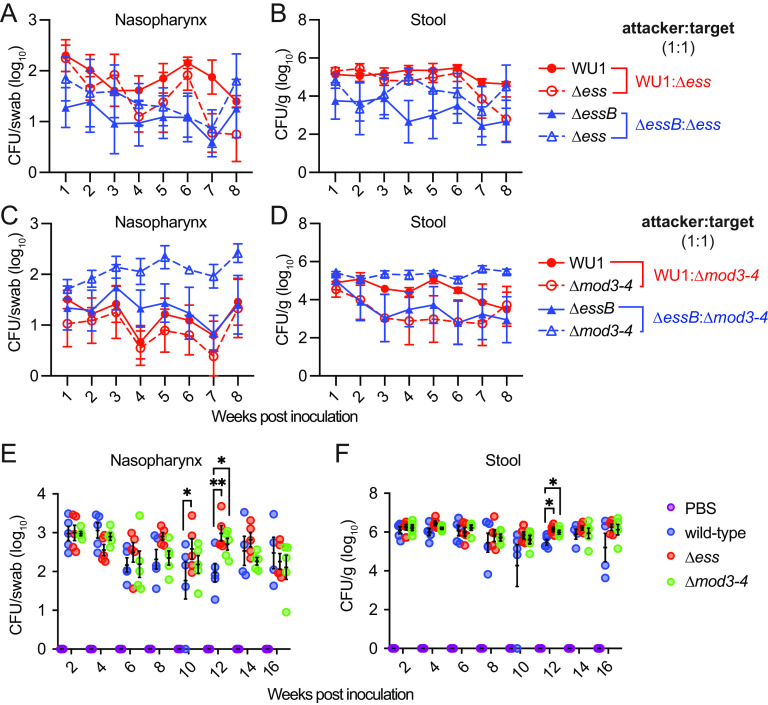

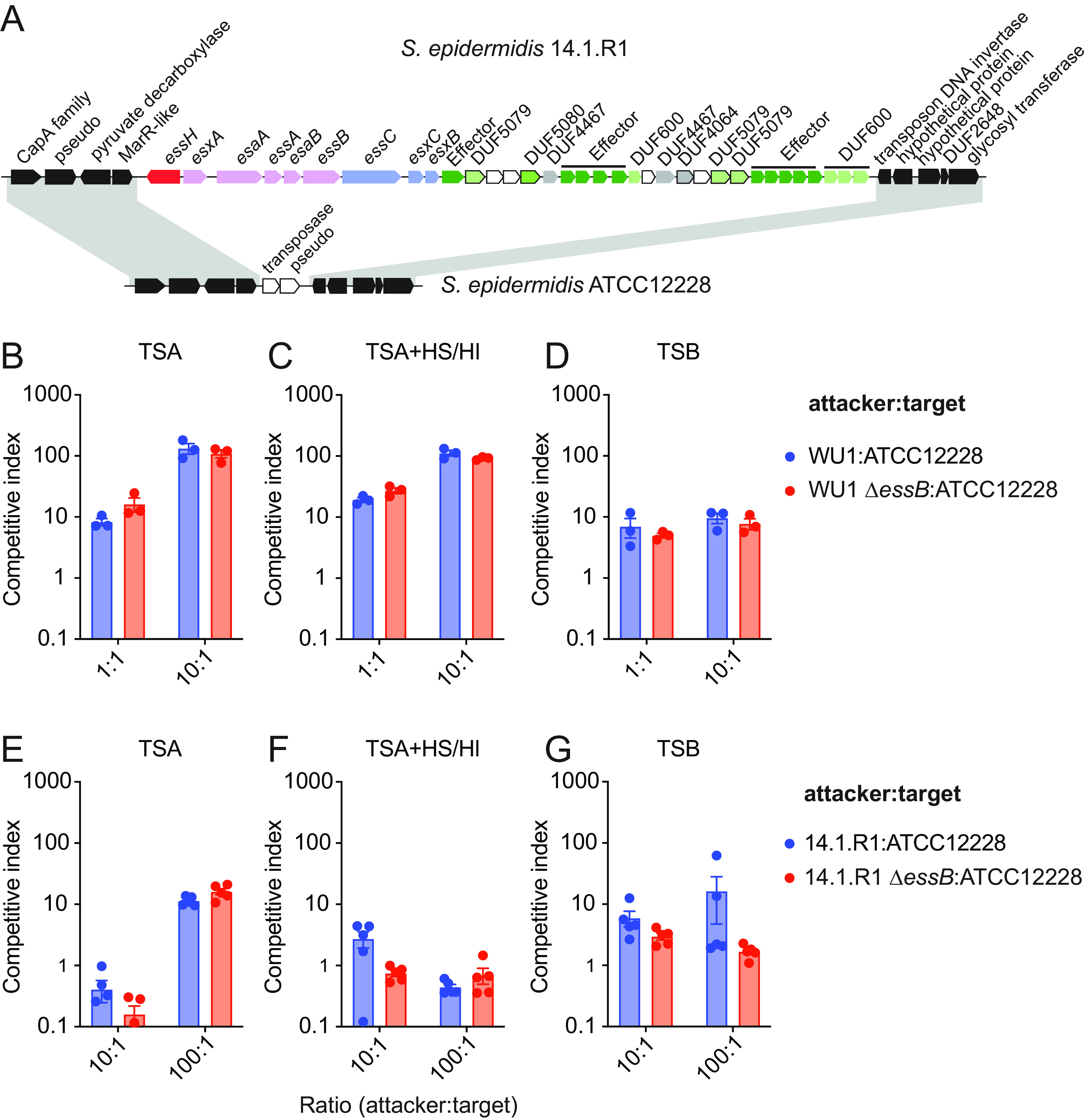

FIG 1.

T7b secretion is dispensable for S. aureus colonization of mice. (A) Illustration of the genomic organization of ESS clusters of the human clinical isolate USA300 and the mouse-adapted strain WU1 (accession number: OQ102510). Name products of genes are indicated when known or otherwise annotated according to the Pubmed DataBank (DUF: domain of unknown function). Genes coding for conserved ESS components (modules 1 and 4) are shown in pink and maroon, respectively. Genes in blue demark sequence diversity in module 2. Genes in the highly variable module 3 are shown in dark green (LXG toxin), light green (DUF600/EssI/immunity factor) and gray (various DUFs). Black depicts genes flaking the ESS cluster. (B) ESS-dependent secretion of substrates by wild-type and ΔessB mutants of USA300 LAC and WU1 strains. Bacterial cultures were fractionated by centrifugation, and proteins in the cell and medium fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and identified by immunoblot using α-EssB, α-EsxA, α-EsxC, α-EssD, -Hla and α-L6 immune sera. (C–D) Cohorts of C57BL/6 mice (n = 10) were inoculated intranasally with 1 × 108 CFU (CFU) of S. aureus WU1 or its ΔessB variant. Bacterial loads in nasopharyngeal swabs (C) and feces (D) were enumerated by plating on MSA in weekly interval. Each dot indicates one animal. The average bacterial burden for a group of animals on a given day and the standard error are indicated by horizontal lines and error bars. Analysis of the data with two-way ANOVA using Sidak multiple-comparison test revealed no statistical significance between groups. The experiment was performed 4 times and one representative data set is shown.

In this study, we take advantage of the S. aureus ST88 strain WU1 that was isolated during an outbreak of skin and soft tissue infections in a mouse breeding facility (28). S. aureus WU1 was found to persistently colonize the nasopharynx of mice, unlike strains isolated directly from a human host (29). Thus, colonization and invasive disease by the mouse-adapted strain WU1 resemble human colonization and invasive disease by clinical isolates such as the common epidemic community-acquired methicillin resistant USA300 LAC strain (referred as USA300 herein). Strain WU1 encodes an ESS gene cluster similar to that of USA300. We sought to investigate the contribution of the T7bSS for colonization and virulence in mice and assess its role in bacterial antagonism using in vitro and in vivo competition experiments.

RESULTS

Genetic makeup of ESS clusters: a case for bacterial antagonism.

Genes of the S. aureus T7bSS are located mostly within the ESS locus initially named for its homology to ESX-1 (ESAT-6 like Secretion System) (20). An alignment of ESS loci from 153 clinical isolates revealed four genetic modules (26). Modules 1 (esxA-esaA-essA-esaB-essB) and 4 (DUF4467 and DUF4064) encode the most conserved genes (Fig. 1A). Although not noted at the time, essH upstream of esxA is also conserved and encodes a peptidoglycan hydrolase required for the secretion of T7b substrates (30). Sequence conservation in module 1 extends to the 5′-coding sequence of essC. The 3′-coding sequence of essC marks the start of sequence differences and module 2. Four alleles of essC have been distinguished (essC1 through essC4) with each allele followed by a distinct set of genes that define module 2. The essC1 allele occurs with the highest frequency and is found in sequence types (clonal complexes) associated with human invasive disease (26), including USA300 (CC8) as well as the mouse-adapted strain WU1 (ST88/CC88) (Fig. 1A). USA300 and WU1 share very similar module 2 genes that encode the secreted proteins EsxC, EsxB, EsxD, EssD, and EssE, a cytoplasmic protein required for secretion of EssD (19–22, 31). Module 3 encompasses a complex arrangement of immunity factors/antitoxins (essI), members of the DUF600 family, which vary in numbers even for isolates from the same sequence type and clonal complex (26) as exemplified with USA300 and WU1. In USA300, the EssI1 (DUF600) gene encoded immediately downstream of EssD acts as the key immunity factor that binds EssD and inhibits the DNase activity of the polymorphic toxin (15, 23). The two EssD proteins in WU1 and USA300 share 96% identity with the majority of amino acid substitutions located in the C-terminal toxin domain. None of the 11 DUF600 proteins in strain WU1 shows a 100% identity match with DUF600 proteins of USA300, suggesting that the two toxins may be sufficiently distinct to escape the antitoxin activity from the other strain. DUF600 genes are also found in strains that do not encode the essC1 allele, which has prompted the proposal that these genes represent orphan immunity factors for the preventive attack by essC1 type strains (32). In addition to DUF600 immunity factors, module 3 encodes other proteins with domains of unknown function (DUF). DUF5079 and DUF5080 are found in both WU1 and USA300 but repeated and amplified in strain WU1. Lastly, in strain WU1, module 3 also carries DUF5083 and DUF5084 that are not found in USA300 and could represent immunity factors of uncharacterized polymorphic toxins encoded by strains with other essC alleles (Fig. 1A).

The T7bSS of strain WU1 is a functional secretion system but is not required for mouse colonization.

Some proteins of the T7bSS can be found in the spent medium of bacterial cultures. Following centrifugation to isolate bacterial cells (cell) from the spent medium (medium), proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a membrane for identification with specific antibodies (Fig. 1B). Earlier studies using strain USA300 revealed that a mutant lacking essB (ΔessB) fails to secrete EsxA, EsxB, EsxC, EsxD, and EssD (21). Here, a similar mutant, ΔessB, was generated in strain WU1 and protein secretion profiles were compared with that of USA300 strains (Fig. 1B). Blotting with anti-hemolysin (α-Hla) and anti-ribosomal protein L6 (α-L6) polyclonal sera served as culture fractionation controls; Hla is secreted by the canonical Sec pathway and L6 is a cytoplasmic protein (Fig. 1B). Immune reactive species corresponding to EsxA, EsxC, and EssD were detected in the medium fractions of the USA300 and WU1 strains, but not the isogenic ΔessB mutants (Fig. 1B). This result indicated that T7bSS is functional in the mouse adapted WU1 strain (Fig. 1B). Next, strains WU1 and isogenic ΔessB were used to colonize C57BL/6 mice (n = 20). Suspensions of 1×108 CFU of bacteria in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were used to inoculate anesthetized animals into the right nostril. Colonization with bacteria was assessed in weekly intervals by swabbing the nasopharynx of animals and collecting fecal pellets. Swabs and feces were spread on mannitol salt agar (MSA) to enumerate CFU (CFU). Animals remained persistently colonized with both wild-type S. aureus WU1 or the isogenic ΔessB mutant (Fig. 1CD). As a control, mock (PBS) inoculated C57BL/6 animals maintained in the same facility did not become colonized with S. aureus (Fig. 1CD). Together these results indicate that neither nasopharyngeal colonization nor replication in the gastrointestinal tract require the T7bSS in this model.

Bacterial competition between related strains is not observed during colonization of mice.

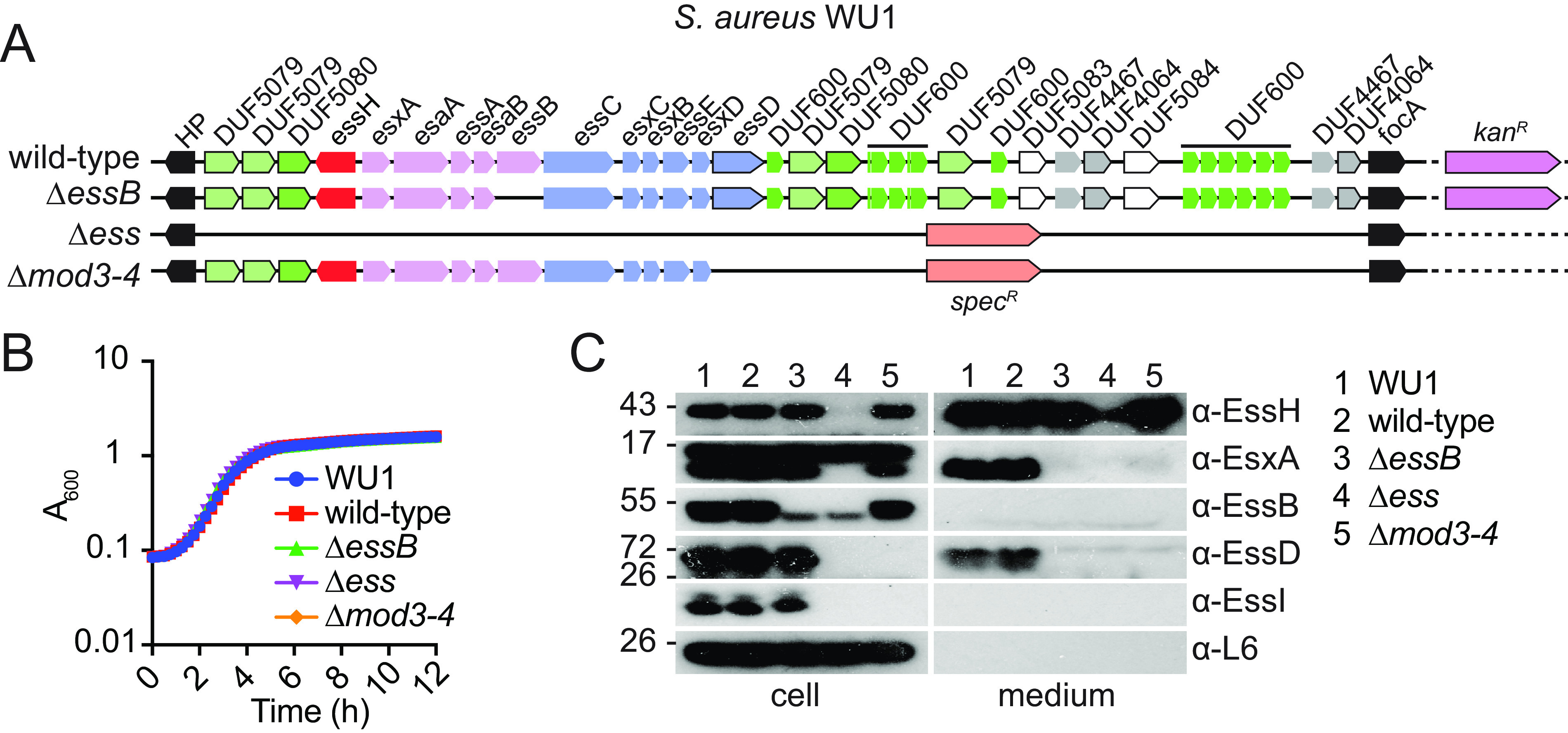

The mouse adapted strain WU1 does not require its T7bSS to colonize animals; both wild-type and T7b-defective bacteria colonize the nasopharynx of animals for weeks making it an ideal model to test bacterial competition. To achieve this goal, we generated WU1 and ΔessB variants marked with a kanamycin resistance gene. We also replaced the entire ESS locus (Δess) and modules 3 and 4 encompassing essD through DUF4064 (Δmod3-4) with a spectinomycin resistance marker (Fig. 2A). The four new strains replicated with growth rates indistinguishable from the WU1 strain when cultured in TSB (Fig. 2B). When analyzed by Western blotting, culture extracts separated between cell and medium fractions, revealed the expected protein production and secretion profiles (Fig. 2C). Deletion of essB abrogated production of EssB and secretion of EsxA and EssD but did not affect the production of EssH or candidate DUF600 antitoxins. Of note, DUF600 production is identified here by using the polyclonal serum raised against USA300 EssI1. DUF600 products of strain WU1 share between 68.1% and 78.5% identity with EssI1 of USA300. None of the probed ESS proteins were observed in extracts of the Δess mutant validating the genetic deletion (Fig. 2C). Also, as expected, deletion of modules 3 and 4 (Δmod3-4) resulted in the loss of EssD and cross-reactive EssI1/DUF600 species as well as the loss of EsxA secretion (Fig. 2C). This result corroborates our earlier findings showing that deletion of essD in strains Newman and USA300 also results in the complete loss of secretion by the T7bSS (21, 23).

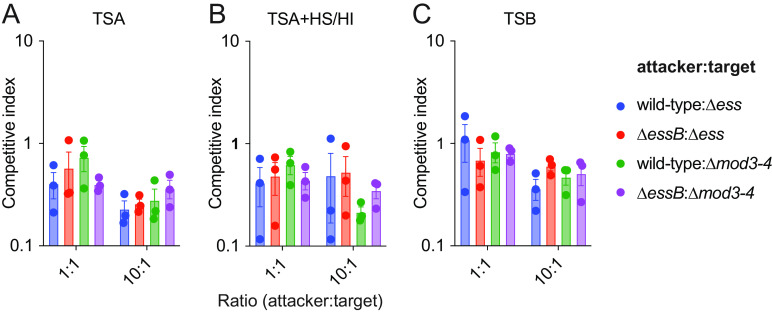

FIG 2.

Generation of marked and T7b defective variants of strain WU1. (A) Illustration of the genomic organization of ESS clusters of WU1 strains modified with antibiotic resistance markers. Color code was the same as in Fig. 1A. (B) Overnight cultures of bacteria were diluted 1:100 in fresh medium and grown at 37°C. Growth was monitored as increased absorbance (A600) in 15-minute intervals for 12 h. (C) Bacterial cultures were grown to A600~3.0 at 37°C in the presence of heat-inactivated horse serum, fractionated by centrifugation, and proteins in the cell and medium fractions were resolved by SDS-PAGE for immunodetection with α-EssH, α-EsxA, α-EssB, αα-EssD, α-EssI and α-L6 immune sera.

Co-colonization studies were set up in cohorts of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5). WU1 represented the candidate attacker strain that was inoculated in animals in a 1:1 ratio with candidate target strains Δess or Δmod3-4 (Fig. 3A to D). In anticipation of competition between isogenic strains, a second experiment was set up using ΔessB as the attacker with the rationale that this strain should not be able to outcompete mutants Δess or Δmod3-4 that lack polymorphic toxins (Fig. 3A to D). As a last control, each new strain was individually tested for animal colonization (Fig. 3E and F). Briefly, the experiments confirmed that the T7bSS is dispensable for colonization of animals (Fig. 3E and F), further no evidence of bacterial competition was observed (Fig. 3A to D). For example, both WU1 and the Δess mutant persisted in animals over 8 weeks (Fig. 3A and B; red lines). Occasionally, bacterial loads in weekly swabs and in the feces fluctuated between competing strains. But these differences were also observed upon co-infection with strains that were both defective for T7b secretion (Fig. 3 AD; blue lines). We cannot rule out that subtle competition events occur during cocolonization, yet such events do not lead to strain replacement in the mouse.

FIG 3.

Intraspecies competition between wild type and T7b defective strains is not observed during colonization of animals. (A–D) Presumed attacker and target strains were mixed at a 1:1 ratio before intranasal inoculation in cohorts of C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) as follows (A, B) WU1:Δess (red), ΔessB:Δess (blue) and (C, D) WU1:Δmod3-4 (red), ΔessB:Δmod3-4 (blue). Animals were monitored for colonization in weekly intervals. Bacterial loads in swabs (A, C) and homogenized fecal pellets (B, D) were recorded after plating on antibiotic selective media. The data are presented as the average CFU per group of animals with the standard error for each sampling (individual animals not shown). (E–F) Animals (n = 5) were inoculated intranasally with PBS or the individual isolates WU1, Δess and Δmod3-4, respectively. Data were obtained and analyzed as described in Fig. 1CD. Experiments were performed 4 times and one representative data set is shown. Data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA using Sidak multiple-comparison test and P values indicated when significant (*, <0.0332; **, P < 0.0021).

Examining bacterial competition in vitro.

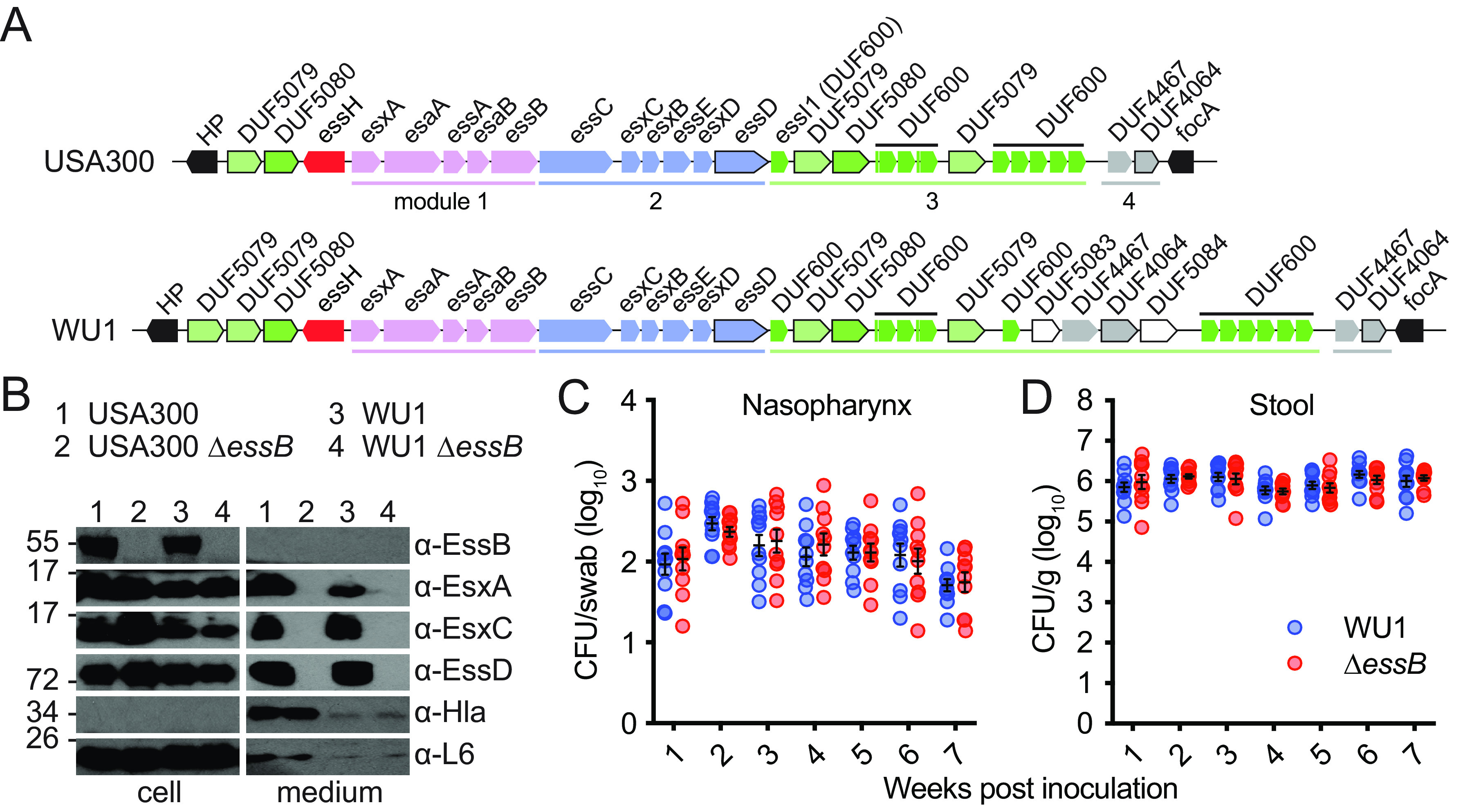

Colonization studies in animals can only be performed with the mouse-adapted WU1 strain. Any other human isolate fails to colonize, unless animals are pretreated with antibiotics to facilitate transient colonization that only lasts a few days (33). Thus, to further investigate bacterial competition, we used in vitro competition assays as described by others (15, 25). The wild-type WU1 or ΔessB and Δess or Δmod3-4 mutants carrying distinct antibiotic resistance markers were cocultured in attacker to prey ratios of 1:1 or 10:1. Briefly, cultures of each strain were grown in broth, mixed at different ratios, and spotted on solid tryptic soy agar (TSA) containing or not heat-inactivated horse serum (HS/HI), which was shown earlier to enhance T7b secretion activity in S. aureus (21, 22). This “spot” method allows to measure contact-dependent bacterial inhibition (34). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h and bacteria suspended in PBS and plated once more on antibiotic media for the selective enumeration of attacker and target strains (Fig. 4AB). In another experiment, pairs of bacteria were simply coinoculated in tryptic soy broth (TSB) instead of spotted on solid medium (Fig. 4C). A competitive index was calculated for each experiment. Wild-type and ΔessB strains coincubated with Δess strain had comparable competitive index in all three conditions explored (Fig. 4; target Δess). It is not known how polymorphic toxins traverse the envelope of target cells. To rule out the possibility that LXG toxins retro-translocate via the ESS translocon of the target cell, competition experiments were also set up with Δmod3-4 as the target (Fig. 4). Competitive index remained unchanged and bacterial antagonism was still not observed under these experimental conditions. Cao and colleagues used attacker to prey ratios of 20:1 to examine antagonistic effects exerted by the S. aureus strain RN6390 overproducing EssD against an isogenic strain lacking the DUF600 immunity factors (15). However, when the WU1 attacker strain was concentrated 20 times (A600 40) and coincubated at a 20:1 ratio with candidate prey strains Δess or Δmod3-4, no competitive advantage was observed for the strain endowed with an intact T7bSS. Unlike S. aureus, other staphylococci such as Staphylococcus epidermidis typically lack an ESS cluster. S. epidermidis is part of the normal human skin microbiota, and shares niches with S. aureus (Fig. 5A). Thus, we asked if S. aureus may antagonize the growth of S. epidermidis using the same assays as described above. However, coculturing S. aureus WU1 wild type or ΔessB with S. epidermidis ATCC12228 did not indicate T7b-dependent antagonism (Fig. 5B to D). To rule out the possibility that toxin transfer could require a T7b conduit elaborated by both species, we exploited strain S. epidermidis 14.1.R1 that encodes an ESS cluster and was isolated from the skin of an acne patient (35) (Fig. 5A). S. epidermidis 14.1.R1 encodes several DUF600 genes and various polymorphic toxins not found in strain WU1 (Fig. 5A). Coculturing S. epidermidis 14.1.R1 or isogenic ΔessB mutant with WU1 did not result in any competitive advantage regardless of the ratios or medium used (1:1, 10:1 or 100:1; TSA or TSA supplemented with HS/HI; data not shown). Lastly, when S. epidermidis 14.1.R1 or its isogenic ΔessB mutant were cocultured at ratios of 10:1 or 100:1 with strain ATCC12228, no competitive advantage was observed either (Fig. 5E to G).

FIG 4.

T7b-dependent secretion is not required for staphylococcal intraspecies competition in vitro. Presumed attacker and target strains were mixed at 1:1 or 10:1 ratio. Attacker:target pairs are indicated on each panel. At t = 0 h, initial bacterial mixtures were serially diluted and plated on TSA for enumeration, or spotted on TSA (A), TSA containing heat-inactivated horse (TSA+HS/HI) (B), or grown in TSB cultures (C), and incubated for 24 h to allow for growth and competition. At t = 24 h, spots were excised and bacteria were suspended in PBS, serially diluted, and plated on TSA containing kanamycin or spectinomycin for enumeration. The data are reported as calculated competitive index. Each experiment was performed at least 4 times. Analysis with the unpaired nonparametric Mann-Whitney t test did not identify any statistical differences between groups.

FIG 5.

T7b-dependent secretion is not required for staphylococcal interspecies competition in vitro. (A) Illustration of the genomic organization of the ESS cluster in S. epidermidis strain14.1.R1 and the same region in S. epidermidis ATCC12228 strain lacking the ESS locus. Shaded areas denote conserved genomic neighborhoods in both strains. (B–G) In vitro competition experiments were performed and analyzed as described in Fig. 4. Attacker:target pairs are indicated on each panel. Each experiment was performed at least 4 times. Analysis with the unpaired nonparametric Mann-Whitney t test did not identify any statistical differences between groups.

The T7bSS contributes to the virulence of strain WU1 in the mouse bloodstream infection model.

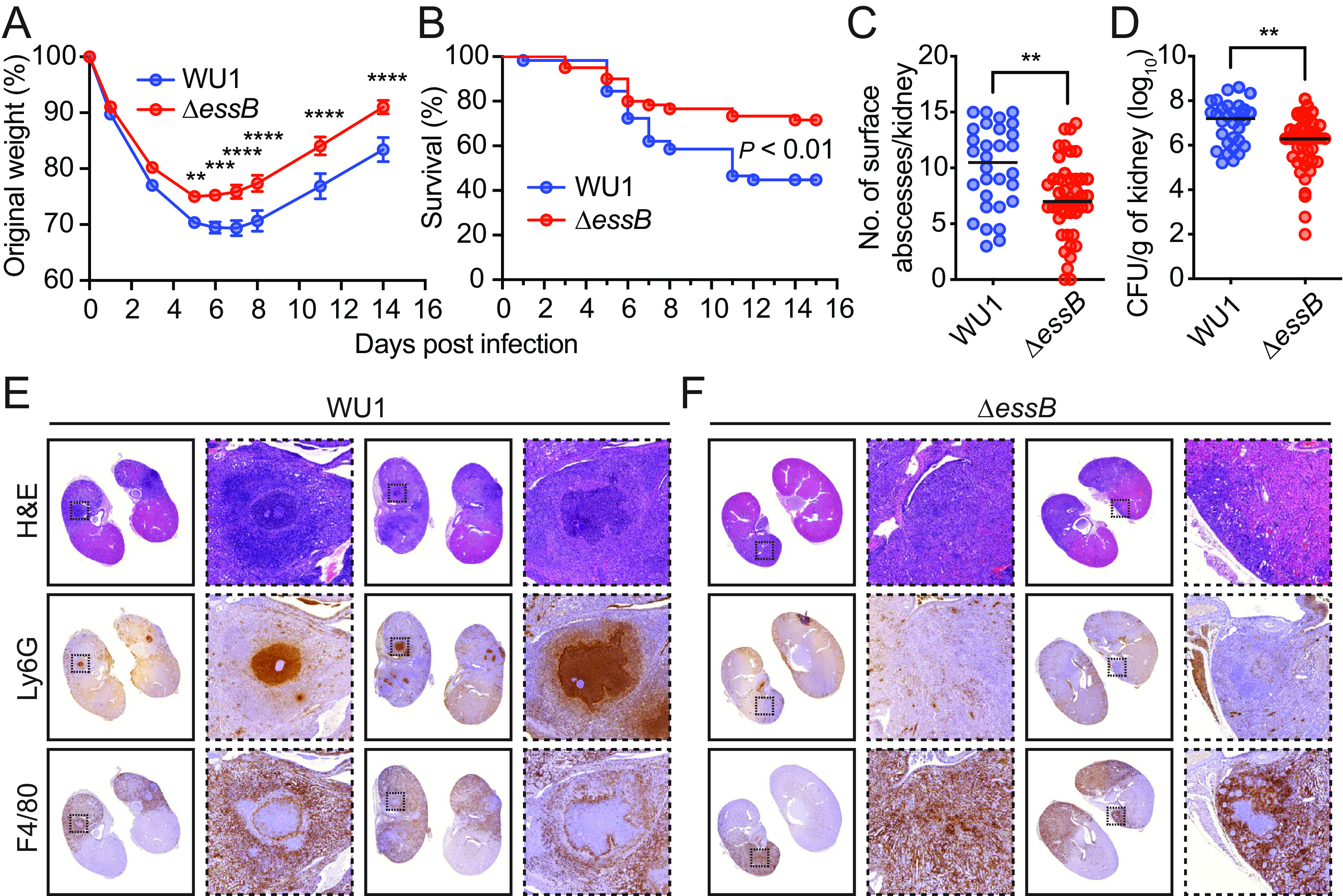

Previous experiments suggested that mutants defective for the T7bSS displayed a virulence defect in a mouse model of bloodstream infection (19, 20, 22). These studies were performed using the well-characterized human isolates methicillin sensitive S. aureus Newman and methicillin resistant USA300. Bacteria inoculated intravenously disseminate to organ tissues and form abscess lesions known as staphylococcal abscess communities (SAC) that persist in animals for weeks (36, 37). To ascertain the contribution of the T7bSS to the pathogenesis of the mouse adapted strain, cohorts of mice were infected by retro-orbital injection of strain WU1 or its isogenic ΔessB mutant. An infectious dose of 2 × 107 CFU of S. aureus resulted in a course of infection with initial weight loss that was statistically more pronounced with strain WU1 compared to ΔessB (Fig. 6A). Animals that lost ≥20% weight were removed from the study, and even after animal regained weight, other clinical signs prompted the removal of more WU1-infected animals than ΔessB-infected mice. To assess the significance of this finding, animal survival was graphed with Kaplan-Meier plots and a statistical difference was found between mice from the two cohorts (Fig. 6B; P = 0.0052). At 14 days following infection, animals in all cohorts were euthanized and necropsied to remove both kidneys. Abscesses visible on the surface of kidneys were enumerated, revealing more lesions in animals infected with WU1 (Fig. 6C; P = 0.0016). Kidneys were homogenized and serially diluted for plating. Mice infected with the ΔessB mutant showed decreased bacterial loads compared to those infected with WU1 (Fig. 6D; 6.3 log10 versus 7.2 log10 CFU, P = 0.0014), revealing defects in the ability of the ΔessB variant to replicate and persist in mouse organ tissues. Following necropsy, some of the kidneys were also fixed in formalin for hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. Staining revealed pathogenic lesions containing SAC, neutrophils, and macrophages (36, 37). Representative microscopy images are shown in Fig. 6E and F. Based on examination of sections, we find that at least 75% of WU1-infected animals (n = 8) developed clear SAC with defined margins (Fig. 6E). Sections from the remaining 25% animals showed diffuse cell infiltrates as would be expected upon clearance. This diffuse pattern was observed in >90% of the sections from ΔessB-infected animals (n = 8; Fig. 6F). Taken together, these data provide strong support for the role of T7b secretion during S. aureus infection of mice and agree with other studies using the human clinical isolates Newman, USA300 or ST398 (19, 20, 22, 31, 38).

FIG 6.

T7b-dependent secretion is required for S. aureus WU1 virulence in mice. (A–D) Cohorts of mice (n = 60) were inoculated intravenously with 2 × 107 CFU of S. aureus WU1 or ΔessB variant. Body weight (A) and survival (B) of infected mice were monitored over a period of 14 days. All surviving mice were euthanized on day 14 (WU1 n = 30, ΔessB n = 43), to enumerate kidney surface abscesses (C) and bacterial counts (CFU) in kidney tissues (D). The data in (A) is presented as the average weight in each group of animals with the standard error (individual animals not shown) and analyzed with two-way ANOVA using Sidak multiple-comparison test (**, P < 0.0021; ***, P < 0.0002; ****, P < 0.000). The data in (B) was analyzed with the Mantel-Cox test. In (C, D), each dot represents an animal and the average and standard error are indicated by the horizontal lines and error bars. The two data sets were analyzed using unpaired t test with two-tailed P value calculation (**, P < 0.0021). (E–F) Representative kidney tissue sections visualized using H&E and antibodies specific for F4/80 (macrophages) or Ly-6G (neutrophils).

DISCUSSION

The ESS locus of S. aureus has been linked to bacterial antagonism (15, 16) and to virulence in bloodstream infections both in humans and animals (19, 39, 40). In humans, infectivity associated with T7b secretion has been observed as a gain of expression of ess genes upon loss of agr function (39). Here, we show that the T7bSS contributes to the pathogenesis of the S. aureus mouse-adapted strain WU1. Animals infected with a ΔessB variant exhibited less weight loss and greater survival than mice infected with strain WU1. Following inoculation, S. aureus bacteria do not remain in the bloodstream, instead they invade soft tissues such as the kidneys to replicate in SAC, a pathogenic lesion driven by the bacterium (36, 37). SAC formed by WU1 were clearly encapsulated with neutrophils contained within the lesion and macrophages excluded from lesions. This clear demarcation was mostly lost in animals infected with ΔessB bacteria which resulted in a reduced number of lesions. Exclusion of macrophage from SAC has been linked to the activities of a secreted nuclease (Nuc) and surface bound exonucleotidase (AdsA). Nuc cleaves DNA released by neutrophils disabling its bactericidal activities (41). Nuc products are converted by AdsA into the immune suppressor adenosine (42) and deoxyadenosine (dAdo) (43–45). In turn, dAdo triggers apoptosis of macrophages which explains the absence of these phagocytes within the SAC (43, 45). We surmise that the DNA nuclease activity of EssD may play a role similar to Nuc. ESS genes have also been shown to be expressed during S. aureus skin infection (40) and ESS mutants of strain ST398 cause smaller skin abscess lesions in infected mice (46). This virulence defect has been proposed to correlate with the lytic activity of EsxX, the polymorphic LXG toxin of strain ST398, toward neutrophils (46). Toxin activities have also been reported for EsxA and EssD (31, 47). EsxA may interfere with the apoptotic pathway of epithelial cells thereby controlling spread and persistence in infected tissues (47). Mice infected with S. aureus USA300 secreting inactive EssD exhibited altered IL-12 and CCL5 proinflammatory responses, which could lead to a more effective T-cell response against infection (31). Primary human dendritic cells (DC) conditioned with supernatants from the ΔesxB mutant strain promoted a stronger IFN-γ and IL-17 responses in CD4+ T cells compared to DC cells conditioned with supernatant from wild-type USA300.

When tested in the WU1-mouse model of colonization, we found that animals remained persistently colonized independently of the presence of ESS genes suggesting that T7bSS-defective variants are not at a disadvantage for colonization. Streptococcaceae, Staphylococcaceae, and Enterococcaceae are the most abundant families of the nasopharyngeal microbiota of C57BL/6 mice (48). Members of these three families also encode ESS clusters with WXG100 proteins and LXG polymorphic toxins and in vitro experiments suggest that some of these species have the potential to compete in a T7b-dependent manner (25, 49). For example, Streptococcus intermedius uses a T7bSS to secrete two LXG polymorphic toxins, TelB and TelC, that degrade the NAD and cell wall precursor Lipid II, respectively (25). When mixed and cultured on a solid surface, TelB and TelC secreting strains impart a significant growth inhibition on other Gram-positive organisms such as Streptococcus pyogenes and Enterococcus faecalis suggesting that LXG toxins and T7bSS could contribute to interbacterial interactions in natural Firmicute-rich bacterial communities (25). E. faecalis was also found to exert bacterial antagonism against S. aureus, Enterococcus faecium, and Listeria monocytogenes in vitro (49). Interestingly, expression of ESS genes in E. faecalis appeared to be inducible following infection with VPE25 bacteriophage or exposure to antibiotics (49).

The two LXG polymorphic toxins, EssD (EsaD) and TspA of S. aureus have been proposed to contribute to intraspecies (interstrain) competition in vitro in experiments using pairs of strains derived from the same parent but either lacking toxin and immunity factors or overproducing one of the LXG toxins (15, 16). Bacterial competition was also observed following coinoculation into the hindbrain ventricle of Zebrafish larvae at a 1:1 ratio. Fewer counts of the target strain lacking EsaD (EssD) and its immunity factors were recovered compared to the wild-type strain, 15 h or 24 h after coinfection (16). It was also noted that Zebrafish larvae survived the single challenge with a T7b-defective (Δess) strain better than a challenge with the wild-type strain (16). Animals were able to clear the Δess strain (16). Because esaD (essD) mutants are defective for general T7b secretion just like Δess strains, it is unclear whether in the co-infection experiment, the target strain lacking EsaD was cleared by the wild-type strain or rather by the larvae’s immune defense (16). The Zebrafish larvae model is also not amenable to studying long term interactions between bacteria since older larvae are eventually killed similarly by wild type and variants unable to perform T7b secretion (16). Mice colonized with the mouse-adapted strain WU1 remain colonized for weeks. The T7bSS is not a requirement for colonization making it possible to study bacterial competition in a physiologically relevant model such as the nasopharynx and gastrointestinal tract of animals. However, much to our surprise, we failed to observe bacterial competition between strains that encode or lack ESS genes. When we examined bacterial antagonism in vitro, we also failed to observe competition on agar plate when strain WU1 was cocultured with an isogenic ESS mutant or with the related S. epidermidis ATTC12228 lacking a T7bSS. Similarly, S. epidermidis 14.1.R1 that carries an extended T7bSS did not yield any competitive advantage over S. epidermidis ATTC12228 or WU1 (35). Thus, while the genetic makeup of ESS clusters does point to intraspecies competition, the result of our experiments is vexing. The simplest explanation is that we have not yet captured conditions that would recapitulate LXG toxin-mediated competition which makes it extremely challenging to elucidate the mechanism of retro-translocation of toxins into target cells. In another instance, LXG toxin-mediated intercellular competition between B. subtilis strains was only observed when bacteria were grown in a biofilm medium (50). It was noted that B. subtilis strains can be distinguished based on the number and sets of LXG toxin–antitoxin genes and genetic experiments were used to show that a wild-type strain will outcompete any engineered variant that lacks any one of the LXG toxin–antitoxin operons under biofilm growth conditions; further, not all toxins had the same killing capacity (50). These observations suggested that the genetic composition of polymorphic toxins may define areas of growth for distinct strains within a biofilm without leading to the dominance of any given clone or the elimination of strains with weaker toxin activity (50).

It is well established that S. aureus exchanges genetic information, in particular antibiotic resistance modules, via mobilizable plasmids and transducing bacteriophages (51). Genetic transfers imply that multiple strains are present at a given time in the same location. Few studies have addressed the clonality of colonizing strains in humans and animals. Lowy and colleagues performed longitudinal sampling over 18 months and found that only 6.6% of colonized humans carry two different S. aureus strains in the nasopharynx, and cocarriage was transient (12). On the other hand, many studies support a highly clonal population of S. aureus with clear dominance of certain clones (52). The diversification of the core genome arises primarily by point mutation (53) with occasionally, recombination events involving large portions of the chromosome (54). Perhaps the ESS cluster favors such exchanges by promoting the lysis of some cells in mixed populations. It is equally possible that the ESS cluster could account for the striking clonality of S. aureus isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions.

S. aureus strains were cultured in tryptic soy broth (TSB) or agar (TSA) at 37°C, unless otherwise stated, and medium was supplemented with 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol for plasmid selection and 0.2% heat-inactivated horse serum (Gibco/Life Technologies) when indicated. Bacteria in nasopharyngeal swabs and feces were plated on Mannitol Salt Agar (Becton, Dickinson, and Company), or TSA supplemented with 200 μg/mL spectinomycin (Spec) or 10 μg/mL kanamycin (Kan) for selection of strains encoding appropriate antibiotic resistance genes. Escherichia coli was cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) medium or agar (LBA) plates at 37°C, supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin for plasmid selection.

Bacterial strain construction.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Allelic replacement via recombination of pKOR1 plasmid was used to generate S. aureus WU1 mutants. pKOR1 mediated allelic replacement was performed as previously published (55). To clone pKOR1 plasmid for construction of WU1 ΔessB strain two 1 kb-fragments, upstream and downstream of the essB gene, were amplified from WU1 chromosomal DNA template with primer pairs 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGGTGATTTTAACTATGATGGTCTTCGTACTTATTAATACG-3′/5′-ATGATTTTTAACCATCTATTTTTCCTCCTATAGTAACTTC-3′ and 5′-GGAAAAATAGATGGTTAAAAATCATGAAAGAAAAAAATAGTATAGGACTGAGGCAAAGACAATGC-3′/5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCTTTCGTTTCAACGATATCTTTAATTTCAGCAACCG-3′. Amplified fragments were fused in a subsequent PCR and cloned into pKOR1 using the BP Clonase II kit (Invitrogen). pKOR1 for construction of WU1 Δess strain was generated by PCR amplifying 1 kb-fragments, upstream of the first DUF5079 encoding gene and downstream of the DUF4064 gene (Fig. 2A), using primers 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCGTGACAGGTCTAACTTTGTACTTTTCAC-3′/5′-AAATTCATAATCTCCCCAATCTCACTTCAATATTTTTATAAG-3′ and 5′-CATCGTATATTGAAATTTCAAGATTTCTTAAGTAATTAAATAAAGTGC-3′/5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGGGTAAATAACGTAGTCGAAACAATAAGAACAAAAGATATATTAC-3′, and amplifying the spectinomycin resistance cassette using primers 5′-GATTGGGGAGATTATGAATTTATCGATTTTCGTTCGTGAATACATGTTATAATAACTATAAC-3′/5′-CTTGAAATTTCAATATACGATGTATGCAAGGGTTTATTGTTTTCTAAAATCTGATTACCAATTAG-3′. pKOR1 for construction of WU1 Δmod3-4 strain was generated by PCR amplifying 1 kb-fragments upstream of essD and downstream of the DUF4064 encoding gene (Fig. 2A) using primers 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCCAAATACGATACATTATCAATTAAGCAAGGGC-3′/5′-TTCAATATCTTTTGTCATGTCATGCACCTATCCC-3′ and 5′-CATCGTATATTGAAATTTCAAGATTTCTTAAGTAATTAAATAAAGTGC-3′/5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGGGTAAATAACGTAGTCGAAACAATAAGAACAAAAGATATATTAC-3′, and amplifying the spectinomycin resistance cassette using primers 5′-CATGACATGACAAAAGATATTGATCGATTTTCGTTCGTGAATACATGTTATAATAACTATAAC-3′/5′-CTTGAAATTTCAATATACGATGTATGCAAGGGTTTATTGTTTTCTAAAATCTGATTACCAATTAG-3′. Amplified fragments for generation of corresponding mutants were stitched by Gibson Assembly (New England BioLabs) and cloned into pKOR1. The kanamycin resistance marker was introduced into WU1 and ΔessB strains by PCR amplifying aphA gene from staphylococcal LAC-p03 plasmid using primers 5′-CTCAAATGAATTTAAGTTTATTACGTGATAAATCACAAATCTCTCCAACAAACGGGCCAGTTTGTTGAAGATTAG-3′/5′-GCATGATTTAATGGGAGACCTATCACATGACTCACGCATAAAATCCCCTTTCATTTTCTAATGTAAATC-3′, and 1 kb-fragments complementary to the sequence in the brnQ-SAUSA300_0307 intergenic region using primer pairs 5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGCTAACGCAGCAACAAGATCCATTGTAAAATAG-3′/5′-GAGAGATTTGTGATTTATCACGTAATAAACTTAAATTCATTTGAG and TCATGTGATAGGTCTCCCATTAAATCATGC-3′/5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGTACATGTAGACGTCCAATTCATATATTATTTAACTTCGC-3′. Three fragments were stitched by Gibson Assembly (New England BioLabs) and cloned into pKOR1. The resulting plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH5α, and then passed through S. aureus RN4220 and JSNZ strains before transforming into S. aureus WU1 strain. Growth temperature was shifted to 40°C in order to block plasmid replication and promote its integration into the chromosome at the homologous sites. Growth in the presence of 200 μg/mL anhydrotetracycline (Clontech) was used to promote allelic replacement and loss of the integrated plasmid. WU1 mutants were confirmed by PCR amplification using flanking primers and by sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | E. coli fhuA2 lacΔU169 phoA glnV44 Φ80' lacZΔM15 gyrA96 recA1 relA1 endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 | 56 |

| RN4220 | restriction deficient, cloning intermediate | 57 |

| JSNZ | A mouse-adapted strain of S. aureus | 33 |

| USA300 LAC* (referred as USA300 in the text) | S. aureus USA300 LAC lacking plasmid pUSA03 encoding the ermC gene for erythromycin resistance | 19, 58 |

| USA300 LAC* ΔessB | S. aureus USA300 LAC* ΔessB | 22 |

| WU1 | A mouse-adapted strain of S. aureus | 28 |

| WU1 ΔessB | S. aureus WU1 ΔessB | This study |

| WU1 Δess | S. aureus WU1 Δess | This study |

| WU1 Δmod3-4 | S. aureus WU1 ΔessD through the last gene of ESS | This study |

| ATCC12228 | S. epidermidis ATCC12228 | 59 |

| 14.1.R1 | S. epidermidis 14.1.R1 | 35 |

| 14.1.R1 ΔessB | S. epidermidis 14.1.R1 ΔessB | Laboratory collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKOR1 | E. coli/S. aureus shuttle vector for allelic replacement in S. aureus | 55 |

Protein secretion and cell culture fractionation.

ESS-dependent secretion of substrates by wild-type and mutant strains was determined by growing S. aureus to an absorbance at 600 nm (A600) of ~3.0 at 37°C in 50 mL of TSB supplemented with heat-inactivated horse serum. Bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min and supernatant transferred to a clean tube. Cell pellets were treated with lysostaphin to release cellular contents. Proteins in the cell and medium fractions were precipitated with 12% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 min and washed with acetone. Dry protein pellets were suspended in 200 μL of 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 containing gel loading buffer and denatured at 90°C for 10 min.

Western blot analysis.

Protein samples were resolved on 12% or 15% SDS-PAGE and visualized either by direct staining with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 or Western blot. For Western blot, proteins were transferred from the gel to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, blocked for 1 h with 5% dry milk in PBST containing 80 μg/mL of human IgG to block protein A (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated with rabbit immune serum (primary polyclonal antibodies) for 16 h at 4°C. Membranes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 detergent (PBST) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit, HRP-linked; Cell Signaling Technology) in PBST containing 5% dry milk followed by 3 washes with PBST. Immune complexes were revealed with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions and developed on Amersham Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Animal experiments.

Overnight cultures of bacteria were diluted (1:100) in fresh TSB and grown at 37°C to A600 of ~0.6. Cells were washed and suspended in PBS. 7-week-old C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with 100 mg/mL ketamine and 20 mg/mL xylazine per kilogram of body weight. For colonization, a bacterial suspension of 1 × 108 CFU was pipetted into the right nostril of each mouse. Colonization was monitored in weekly intervals by gently swabbing the nasopharynx of animals and by collecting feces. Swabs were plated directly on MSA. Fecal pellets were weighed and homogenized in PBS before plating on MSA. Plates were incubated at 37°C for enumeration of CFU. For bacterial cocolonization experiments, two bacterial suspensions of 1 × 108 CFU were mixed at 1:1 ratio and pipetted into the right nostril of each mouse. TSA supplemented with 200 μg/mL spectinomycin or 10 μg/mL of kanamycin for selection was used instead of MSA.

For bloodstream infection, bacterial suspensions were prepared as described above and 5 × 107 CFU were injected into the periorbital venous plexus of anesthetized animals. Mice were weighed as indicated and health was monitored in intervals as short as 6 h. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation and necropsied on day 14 postinoculation. Kidneys were homogenized in PBS, and serial dilutions plated on TSB for CFU enumeration. For histological analysis, kidneys were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin and thin-sectioned. Tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated through xylenes and serial dilutions of EtOH to deionized water. Sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or with specific antibodies. Sections were incubated in antigen retrieval buffer (Dako) and heated in steamer at over 97°C for 20 min. Anti-mouse F4/80 (1:200, AbD Serotec) or Ly-6G (1:200, AbD Serotec) antibodies were applied on tissue sections and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Following washes with TBS, tissue sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-rat IgG (10 μg/mL, Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature. The antigen-antibody binding was detected by Elite kit (Vector Laboratories) and DAB (Dako) system.

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 9 (GraphPad Software). Bacterial colonization data sets were analyzed with two-way ANOVA using Sidak multiple-comparison test. Body weight data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA using Sidak multiple-comparison test, abscess numbers and bacterial loads in renal tissues were analyzed using the unpaired t test with two-tailed P value calculation. Survival curve data were analyzed with the Mantel-Cox test.

In vitro bacterial competition.

Bacterial strains were cultured in TSB and diluted to A600 of 0.25. Bacterial suspensions of arbitrarily designated attacker and target strains were mixed at specified ratios and an aliquot was plated on appropriate selective media for initial enumeration. The cocultures were either incubated in TSB or spotted on TSA or TSA supplemented with heat-inactivated horse serum when indicated. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, bacteria were suspended in PBS, and serially diluted to enumerate final CFU on TSA containing appropriate antibiotics for selection. Competitive index was calculated as (final attacker/final target)/(initial attacker/initial target) and data were analyzed for statistical significance by unpaired nonparametric Mann-Whitney t test using Prism 9 (GraphPad Software).

Sequence deposition.

The nucleotide sequence of the S. aureus WU1 ESS cluster and flanking genes were deposited in the GenBank data bank under accession number OQ102510.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Missiakas laboratory for discussion and comments and remember Olaf Schneewind for his invaluable insights early on during this project. We are grateful to Yan Sun for sharing her expertise in the mouse colonization model and to Ryan Ohr, who generated the S. epidermidis 14.1.R1 ΔessB strain. Research on S. aureus in the Missiakas laboratory is supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) under awards AI038897 and AI052474. M.B. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NIAID F32AI140643) and is currently a recipient of a NIH Pathway to Independence award (NIAID K99AI171164).

Contributor Information

Maksym Bobrovskyy, Email: mbobrovskyy@bsd.uchicago.edu.

Nancy E. Freitag, University of Illinois at Chicago

REFERENCES

- 1.van Belkum A, Melles DC, Nouwen J, van Leeuwen WB, van Wamel W, Vos MC, Wertheim HF, Verbrugh HA. 2009. Co-evolutionary aspects of human colonisation and infection by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Genet Evol 9:32–47. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kluytmans J, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H. 1997. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and associated risks. Clin Microbiol Rev 10:505–520. doi: 10.1128/CMR.10.3.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyce JM, Havill NL, Maria B. 2005. Frequency and possible infection control implications of gastrointestinal colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 43:5992–5995. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.5992-5995.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mertz D, Frei R, Periat N, Zimmerli M, Battegay M, Fluckiger U, Widmer AF. 2009. Exclusive Staphylococcus aureus throat carriage: at-risk populations. Arch Intern Med 169:172–178. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leshem E, Maayan-Metzger A, Rahav G, Dolitzki M, Kuint J, Roytman Y, Goral A, Novikov I, Fluss R, Keller N, Regev-Yochay G. 2012. Transmission of Staphylococcus aureus from mothers to newborns. Pediatr Infect Dis J 31:360–363. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318244020e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maayan-Metzger A, Strauss T, Rubin C, Jaber H, Dulitzky M, Reiss-Mandel A, Leshem E, Rahav G, Regev-Yochay G. 2017. Clinical evaluation of early acquisition of Staphylococcus aureus carriage by newborns. Int J Infect Dis 64:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peacock SJ, Justice A, Griffiths D, de Silva GD, Kantzanou MN, Crook D, Sleeman K, Day NP. 2003. Determinants of acquisition and carriage of Staphylococcus aureus in infancy. J Clin Microbiol 41:5718–5725. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5718-5725.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dancer SJ. 2008. Importance of the environment in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus acquisition: the case for hospital cleaning. Lancet Infect Dis 8:101–113. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MF, Iverson SA, Baron P, Vasse A, Silbergeld EK, Lautenbach E, Morris DO. 2012. Household transmission of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other staphylococci. Lancet Infect Dis 12:703–716. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. 2001. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N Engl J Med 344:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Verbrugh HA, Nouwen JL. 2005. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis 5:751–762. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cespedes C, Said-Salim B, Miller M, Lo SH, Kreiswirth BN, Gordon RJ, Vavagiakis P, Klein RS, Lowy FD. 2005. The clonality of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage. J Infect Dis 191:444–452. doi: 10.1086/427240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khatib R, Sharma M, Naqvi SA, Riederer K, Almoujahed MO, Fakih MG. 2003. Molecular analysis of Staphylococcus aureus blood isolates shows lack of polyclonal bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol 41:1717–1719. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1717-1719.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabijan AP, Ben Zakour NL, Ho J, Lin RCY, Iredell J, Westmead Bacteriophage Therapy T, AmpliPhi Biosciences C . 2019. Polyclonal Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Ann Intern Med 171:940–941. doi: 10.7326/L19-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao Z, Casabona MG, Kneuper H, Chalmers JD, Palmer T. 2016. The type VII secretion system of Staphylococcus aureus secretes a nuclease toxin that targets competitor bacteria. Nat Microbiol 2:16183. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulhuq FR, Gomes MC, Duggan GM, Guo M, Mendonca C, Buchanan G, Chalmers JD, Cao Z, Kneuper H, Murdoch S, Thomson S, Strahl H, Trost M, Mostowy S, Palmer T. 2020. A membrane-depolarizing toxin substrate of the Staphylococcus aureus type VII secretion system mediates intraspecies competition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:20836–20847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006110117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aly KA, Anderson M, Ohr RJ, Missiakas D. 2017. Isolation of a membrane protein complex for type VII secretion in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 199:e00482–17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00482-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bobrovskyy M, Oh SY, Missiakas D. 2022. Contribution of the EssC ATPase to the assembly of the type 7b secretion system in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 298:102318. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burts ML, DeDent AC, Missiakas DM. 2008. EsaC substrate for the ESAT-6 secretion pathway and its role in persistent infections of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 69:736–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burts ML, Williams WA, DeBord K, Missiakas DM. 2005. EsxA and EsxB are secreted by an ESAT-6-like system that is required for the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:1169–1174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405620102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson M, Aly KA, Chen YH, Missiakas D. 2013. Secretion of atypical protein substrates by the ESAT-6 secretion system of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 90:734–743. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson M, Chen YH, Butler EK, Missiakas DM. 2011. EsaD, a secretion factor for the Ess pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 193:1583–1589. doi: 10.1128/JB.01096-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohr RJ, Anderson M, Shi M, Schneewind O, Missiakas D. 2017. EssD, a Nuclease Effector of the Staphylococcus aureus ESS Pathway. J Bacteriol 199:e00528–16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00528-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang D, de Souza RF, Anantharaman V, Iyer LM, Aravind L. 2012. Polymorphic toxin systems: comprehensive characterization of trafficking modes, processing, mechanisms of action, immunity and ecology using comparative genomics. Biol Direct 7:18. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitney JC, Peterson SB, Kim J, Pazos M, Verster AJ, Radey MC, Kulasekara HD, Ching MQ, Bullen NP, Bryant D, Goo YA, Surette MG, Borenstein E, Vollmer W, Mougous JD. 2017. A broadly distributed toxin family mediates contact-dependent antagonism between gram-positive bacteria. Elife 6:e26938. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warne B, Harkins CP, Harris SR, Vatsiou A, Stanley-Wall N, Parkhill J, Peacock SJ, Palmer T, Holden MT. 2016. The Ess/Type VII secretion system of Staphylococcus aureus shows unexpected genetic diversity. BMC Genomics 17:222. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang D, Iyer LM, Aravind L. 2011. A novel immunity system for bacterial nucleic acid degrading toxins and its recruitment in various eukaryotic and DNA viral systems. Nucleic Acids Res 39:4532–4552. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Y, Emolo C, Holtfreter S, Wiles S, Kreiswirth B, Missiakas D, Schneewind O. 2018. Staphylococcal protein A contributes to persistent colonization of mice with Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 200:e00735–17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00735-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulz D, Grumann D, Trube P, Pritchett-Corning K, Johnson S, Reppschlager K, Gumz J, Sundaramoorthy N, Michalik S, Berg S, van den Brandt J, Fister R, Monecke S, Uy B, Schmidt F, Broker BM, Wiles S, Holtfreter S. 2017. laboratory mice are frequently colonized with Staphylococcus aureus and mount a systemic immune response-note of caution for in vivo infection experiments. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:152. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bobrovskyy M, Willing SE, Schneewind O, Missiakas D. 2018. EssH peptidoglycan hydrolase enables Staphylococcus aureus type VII secretion across the bacterial cell wall envelope. J Bacteriol doi: 10.1128/JB.00268-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson M, Ohr RJ, Aly KA, Nocadello S, Kim HK, Schneewind CE, Schneewind O, Missiakas D. 2017. EssE promotes Staphylococcus aureus ESS-dependent protein secretion to modify host immune responses during infection. J Bacteriol 199:e00527–16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00527-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowman L, Palmer T. 2021. The Type VII secretion system of Staphylococcus. Annu Rev Microbiol 75:471–494. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-012721-123600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holtfreter S, Radcliff FJ, Grumann D, Read H, Johnson S, Monecke S, Ritchie S, Clow F, Goerke C, Broker BM, Fraser JD, Wiles S. 2013. Characterization of a mouse-adapted Staphylococcus aureus strain. PLoS One 8:e71142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aoki SK, Pamma R, Hernday AD, Bickham JE, Braaten BA, Low DA. 2005. Contact-dependent inhibition of growth in Escherichia coli. Science 309:1245–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.1115109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christensen GJ, Scholz CF, Enghild J, Rohde H, Kilian M, Thurmer A, Brzuszkiewicz E, Lomholt HB, Bruggemann H. 2016. Antagonism between Staphylococcus epidermidis and Propionibacterium acnes and its genomic basis. BMC Genomics 17:152. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2489-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng AG, Kim HK, Burts ML, Krausz T, Schneewind O, Missiakas DM. 2009. Genetic requirements for Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation and persistence in host tissues. FASEB J 23:3393–3404. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-135467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng AG, DeDent AC, Schneewind O, Missiakas D. 2011. A play in four acts: Staphylococcus aureus abscess formation. Trends Microbiol 19:225-232. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Hu M, Liu Q, Qin J, Dai Y, He L, Li T, Zheng B, Zhou F, Yu K, Fang J, Liu X, Otto M, Li M. 2016. Role of the ESAT-6 secretion system in virulence of the emerging community-associated Staphylococcus aureus lineage ST398. Sci Rep 6:25163. doi: 10.1038/srep25163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altman DR, Sullivan MJ, Chacko KI, Balasubramanian D, Pak TR, Sause WE, Kumar K, Sebra R, Deikus G, Attie O, Rose H, Lewis M, Fulmer Y, Bashir A, Kasarskis A, Schadt EE, Richardson AR, Torres VJ, Shopsin B, van Bakel H. 2018. Genome plasticity of agr-defective Staphylococcus aureus during clinical infection. Infect Immun 86:e00331–18. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00331-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruz AR, van Strijp JAG, Bagnoli F, Manetti AGO. 2021. Virulence gene expression of Staphylococcus aureus in human skin. Front Microbiol 12:692023. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.692023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berends ET, Horswill AR, Haste NM, Monestier M, Nizet V, von Köckritz-Blickwede M. 2010. Nuclease expression by Staphylococcus aureus facilitates escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. J Innate Immun 2:576–586. doi: 10.1159/000319909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thammavongsa V, Kern JW, Missiakas DM, Schneewind O. 2009. Staphylococcus aureus synthesizes adenosine to escape host immune responses. J Exp Med 206:2417–2427. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thammavongsa V, Missiakas DM, Schneewind O. 2013. Staphylococcus aureus conversion of neutrophil extracellular traps into deoxyadenosine promotes immune cell death. Science 342:863–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1242255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winstel V, Missiakas D, Schneewind O. 2018. Staphylococcus aureus targets the purine salvage pathway to kill phagocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:6846–6851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805622115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winstel V, Schneewind O, Missiakas D. 2019. Staphylococcus aureus Exploits the Host Apoptotic Pathway To Persist during Infection. mBio 10:e02270–19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02270-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dai Y, Wang Y, Liu Q, Gao Q, Lu H, Meng H, Qin J, Hu M, Li M. 2017. A Novel ESAT-6 Secretion system-secreted protein EsxX of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus lineage ST398 contributes to immune evasion and virulence. Front Microbiol 8:819. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korea CG, Balsamo G, Pezzicoli A, Merakou C, Tavarini S, Bagnoli F, Serruto D, Unnikrishnan M. 2014. Staphylococcal Esx proteins modulate apoptosis and release of intracellular Staphylococcus aureus during infection in epithelial cells. Infect Immun 82:4144–4153. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01576-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schenck LP, McGrath JJC, Lamarche D, Stampfli MR, Bowdish DME, Surette MG. 2020. Nasal tissue extraction is essential for characterization of the murine upper respiratory tract microbiota. mSphere 5. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00562-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chatterjee A, Willett JLE, Dunny GM, Duerkop BA. 2021. Phage infection and sub-lethal antibiotic exposure mediate Enterococcus faecalis type VII secretion system dependent inhibition of bystander bacteria. PLoS Genet 17:e1009204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi K. 2021. Diverse LXG toxin and antitoxin systems specifically mediate intraspecies competition in Bacillus subtilis biofilms. PLoS Genet 17:e1009682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haaber J, Penades JR, Ingmer H. 2017. Transfer of Antibiotic Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol 25:893–905. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith JT, Eckhardt EM, Hansel NB, Eliato TR, Martin IW, Andam CP. 2021. Genomic epidemiology of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus from bloodstream infections. BMC Infect Dis 21:589. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06293-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feil EJ, Cooper JE, Grundmann H, Robinson DA, Enright MC, Berendt T, Peacock SJ, Smith JM, Murphy M, Spratt BG, Moore CE, Day NP. 2003. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus? J Bacteriol 185:3307–3316. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3307-3316.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spoor LE, Richardson E, Richards AC, Wilson GJ, Mendonca C, Gupta RK, McAdam PR, Nutbeam-Tuffs S, Black NS, O'Gara JP, Lee CY, Corander J, Ross Fitzgerald J. 2015. Recombination-mediated remodelling of host-pathogen interactions during Staphylococcus aureus niche adaptation. Microb Genom 1:e000036. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bae T, Schneewind O. 2006. Allelic replacement in Staphylococcus aureus with inducible counter-selection. Plasmid 55:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woodcock DM, Crowther PJ, Doherty J, Jefferson S, DeCruz E, Noyer-Weidner M, Smith SS, Michael MZ, Graham MW. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res 17:3469–3478. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kreiswirth BN, Lofdahl S, Betley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diep BA, Carleton HA, Chang RF, Sensabaugh GF, Perdreau-Remington F. 2006. Roles of 34 virulence genes in the evolution of hospital- and community-associated strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 193:1495–1503. doi: 10.1086/503777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang YQ, Ren SX, Li HL, Wang YX, Fu G, Yang J, Qin ZQ, Miao YG, Wang WY, Chen RS, Shen Y, Chen Z, Yuan ZH, Zhao GP, Qu D, Danchin A, Wen YM. 2003. Genome-based analysis of virulence genes in a non-biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis strain (ATCC 12228). Mol Microbiol 49:1577–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]