Abstract

Advancements in chimeric antigen receptor engineered T-cell (CAR-T) therapy have revolutionized treatment for several cancer types over the past decade. Despite this success, obstacles including the high price tag, manufacturing complexity, and treatment-associated toxicities have limited the broad application of this therapy. Chimeric antigen receptor engineered natural killer cell (CAR-NK) therapy offers a potential opportunity for a simpler and more affordable “off-the-shelf” treatment, likely with fewer toxicities. Unlike CAR-T, CAR-NK therapies are still in early development, with few clinical trials yet reported. Given the challenges experienced through the development of CAR-T therapies, this review explores what lessons we can apply to build better CAR-NK therapies. In particular, we explore the importance of optimizing the immunochemical properties of the CAR construct, understanding factors leading to cell product persistence, enhancing trafficking of transferred cells to the tumor, ensuring the metabolic fitness of the transferred product, and strategies to avoid tumor escape through antigen loss. We also review trogocytosis, an important emerging challenge that likely equally applies to CAR-T and CAR-NK cells. Finally, we discuss how these limitations are already being addressed in CAR-NK therapies, and what future directions may be possible.

Keywords: natural kill cell, T cell, chimeric antigen receptor, trogocytosis, immunotherapy, cancer

Introduction

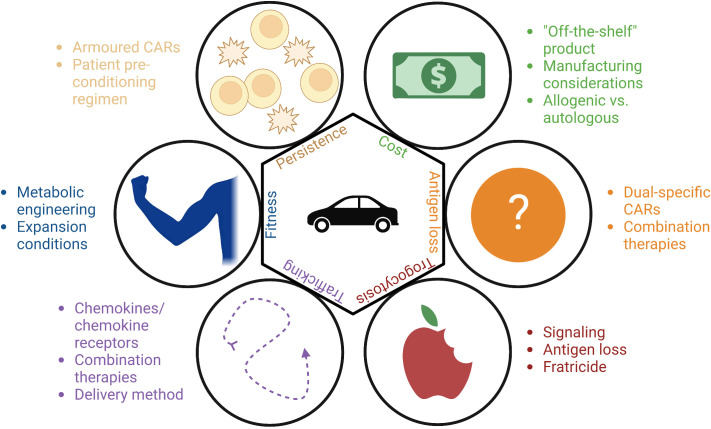

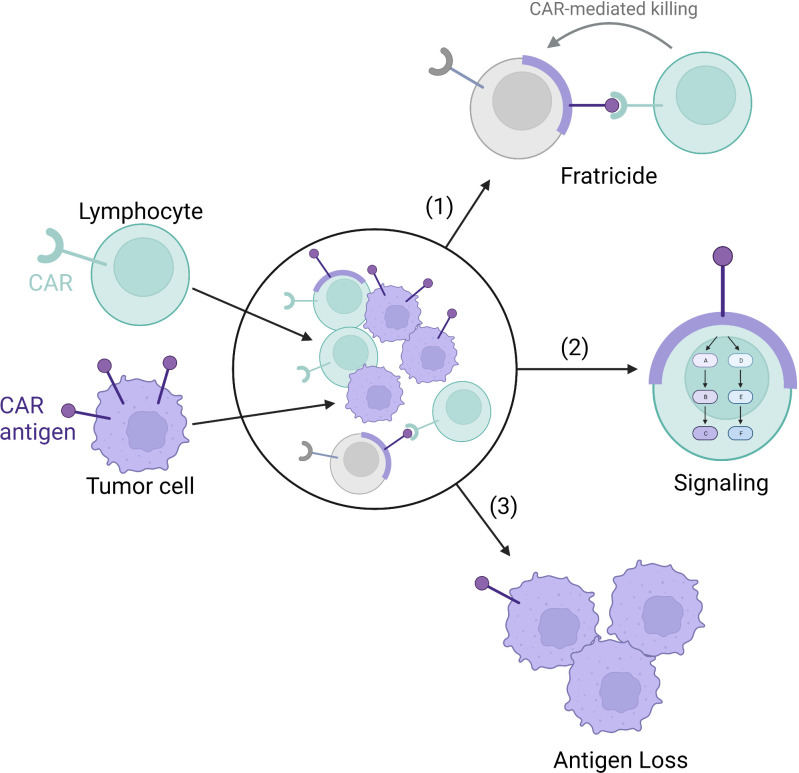

Although chimeric antigen receptor engineered T-cells (CAR-T) have produced astounding remission rates in patients with hematological cancers, response rates have been much lower in patients with solid tumors (1). Furthermore, long-term follow up has shown that approximately half of the patients achieving an initial complete response with CAR-T will ultimately relapse (2, 3). Key barriers leading to suboptimal CAR therapy responses include limited persistence of transferred cells, poor metabolic fitness of cellular products, issues with trafficking of CAR-T cells to sites of disease, and loss of target antigen on malignant cells ( Figure 1 ) (4). Another emerging challenge for CAR therapies is trogocytosis, wherein cell membranes are transferred from target cells to immune cells, resulting in antigen loss on target cells and fratricidal destruction of CAR cells ( Figure 2 ) (5). Importantly, as clinical experience with CAR-NK is very limited compared to CAR-T, how much each of these factors contribute to CAR-NK clinical efficacy remains unclear. This offers researchers and clinicians a unique opportunity to proactively apply lessons learned while developing CAR-T products to the CAR-NK field. For the remainder of this mini review, we will provide updates on the well-identified barriers and then discuss at length the concept of trogocytosis and the work that has been done to address this increasingly recognized phenomenon.

Figure 1.

Methods to overcome the barriers to the CAR-T and CAR-NK fields: cost, antigen loss, trogocytosis, trafficking, fitness, and persistence.

Figure 2.

Trogocytosis-mediated antigen procurement leads to trogocytosis-mediated signaling, antigen loss leading to tumor escape, and fratricide. The tumor cell membrane (purple) and CAR antigen is transferred to the CAR-lymphocytes (green) via trogocytosis. (1) The transferred membrane acts as a target for CAR-mediated fratricide leading to lymphocyte cell death (grey). (2) The transferred membrane can also signal within the CAR-lymphocyte. (3) Finally, the transfer of the cell membrane results in antigen loss on the tumor cells themselves.

Manufacturing and cost

CD19-targeted CAR-T has achieved unprecedented clinical response in leukemia and lymphoma, and now B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-targeted CAR-T is yielding remarkable results in patients with multiple myeloma (6, 7). High cost and complex manufacturing for these personalized CAR-T limit access to these therapies (8). Recently, studies have reported the use of distributed and highly automated CAR-T manufacturing as a strategy to significantly reduce manufacturing costs relative to centralized processes (9–11). An alternative cost-reduction strategy would be to develop an “off the shelf” therapeutic, wherein modified cells are manufactured in large numbers at a central location and used allogeneically to treat many patients (12).

Currently, CAR-T products approved for commercial use are all produced using lentiviral or retroviral vector transduction, and are only used autologously due to the risk of graft versus host disease (GvHD). It is important to note though that it may be possible to safely apply donor derived allogenic CAR-T molecules in post-haematopoietic cell transplantion (HCT) settings without acute GvHD (13). Gene editing to remove T cell receptor expression from CAR-T cells has been employed to eliminate the risk of GvHD with TCR-edited allogeneic CAR-T products. However, this increases manufacturing complexity and cost, and the safety profile of such gene-edited CAR-T cells is not yet fully understood (14–16). Unlike CAR-T cells, CAR-NK cells do not cause GvHD and can thus be applied allogeneically without such gene editing (17).

To maximize the benefit of an off-the-shelf therapy, as with gene-edited CAR-T, it will also be vital to identify manufacturing approaches that can scale up CAR-NK products to treat as many patients as possible per product batch (18–20). Like CAR-T cells, cytokines alone can achieve expansion of NK cells to clinically relevant doses (21, 22). NK expansion can be greatly increased with the use of feeder cells, however, feeder cells can be difficult to completely remove from the culture, therefore leading to safety concerns (23–26). An alternative feeder-free method being explored involves the use of dissolveable polymer-based microspheres that slowly release growth factors and nutrients to facilitate cell expansion (27).

Vesicular-stomatitis-virus-G protein (VSV-G) lentivirus is the most commonly used pseudotyping receptor applied in manufacturing CAR-T cells. Unlike T cells though, NK cells have low expression of the low density lipoprotein receptor, a major entry receptor for VSV-G (28). Baboon envelope pseudotyped lentiviral vector (BaEV-LV) has been shown to greatly improve transduction efficiency in NK cells (29), and can also be used for the delivery of CRISPR-genome editing components through viral like particles (30). We have recently shown that CRISPR-loaded BaEV-partcles can be used for efficient simultaneous genome editing of primary NK cells and CAR-transgene delivery, potentially offering a promising opportunity to clinical scale deployment of gene edited CAR-NK therapies (31).

The relative risk of insertional mutagenesis represents another potential issue for CAR-NK therapies manufactured via viral gene transfer. There are at least two cases of T-cell lymphomas arising from CAR-modified cells, though it is important to note that both of these occurred in transposon modified cells, a process that can lead to many insertion events within a single cell (32). In contrast to this, thousands of patients have now been treated with CAR-T therapies generated via retro- or lentiviral transduction, with follow-up times as long as 20-years, and no malignant T-cell lymphomas have yet been reported (33). There are at least two case reports of insertional disruption of a specific gene being associated with clonal CAR-T hyperexpansion (34, 35). Remarkably, in both cases CAR-T expansion drove a strong therapeutic response without creating a T-cell malignancy. Whether the impressive safety record of virally modified CAR-T cells can also be extended to CAR-NK cells remains to be seen. Publication of pre-clinical and clinical reports with insertion site mapping in CAR-NK cells will be critical to address this question in future.

Persistence

Dogma dictates that NK cells are inherently less likely to demonstrate long term persistence than T cells (36). Indeed, the short lifespan of transferred cells has been proposed as an explanation for the limited clinical efficacy of NK cell therapies in clinical trials (37–39). To date, much of the work in optimizing CAR constructs for NK cells has focused on improving cytotoxicity as opposed to evaluating persistence (18, 40, 41), though it is known that CAR-NK cell persistence can be improved by engineering cells with immunostimulatory cytokines such as IL-15 (42–49). A clinical trial employing IL-15 engineered CD19-targeted CAR-NK cells in relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies is currently underway, and has already reported to be safe and show at least short term efficacy in a cohort of patients [(50); NCT05092451].

Short-term exposure to IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 produces memory-like NK cells with longer persistence (51), which can be combined with CAR-NK to increase efficacy (52). In CAR-T products, expression of certain costimulatory domains is known to enrich for memory phenotype CAR-T cells and is associated with improved persistence and more durable responses in preclinical models and clinical trials (53–55). Engineering of CAR-T cells with immunostimulatory cytokines (secreted or membrane bound) such as IL-7, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-21, and IL-23, to create “armoured CARs”, has also been shown to improve persistence and is being explored in several clinical trials (56, 57).

Another method to increase CAR cell functionality, safety, and specificity is the use of inducible promoters, which become active upon recognition of a tumor associated antigen, metabolite, drug, or through activation of cell signaling pathways. Ultimately, the goal is to facilitate a more directed delivery of an additional transgene without systemic toxicity (58). This has been shown to be effective in CAR-T cells using a nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) promoter (59). This type of sense-and-respond engineering of CAR-T cells is extremely flexible and could be applied to deliver a wide variety of TME-modifying payloads to improve CAR-T or CAR-NK penetration and survival within tumours (60, 61). This approach has also been tried with CAR-NK cells; the use of a nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) inducible promoter to induce IL-12 secretion upon CAR-NK activation led to increased cytotoxicity and monocyte recruitment (62).

A major clinical determinant of NK cell persistence is the lymphodepleting pre-conditioning regimen used to prepare patients before cell infusion. Thusfar, the role of lymphodepletion with CAR-NK therapy has been extrapolated from CAR-T studies, where lymphodepletion has been shown to be vital for the efficacy of CAR-T (63). Typically, a combination of fludarabine/cyclophosphamide is used prior to receiving CAR-NK therapy to reduce NK cell rejection by the host, reprogram the immunosuppressive TME, and decrease tumor burden (18). Comparing high-dose and low-dose lymphodepletion regimens prior to adoptive transfer of unmodified NK cell therapies has demonstrated that high-dose regimens resulted in in vivo NK expansion and persistence while low-dose regimens did not (64). The use of CD52-targeting monoclonal antibodies in combination with CD52-knockout CAR-T cells is increasingly being employed as a selective lymphodepletion strategy which can be employed concurrently with cellular infusion (65), whether such an approach can work with CAR-NK cells has not yet been investigated. To our knowledge, there have been no clinical trials comparing lympdepleting regimens in CAR-NK therapies, and this is an area where further investigation will be needed. The need for further study will be even more critical when applying CAR-NK in solid tumours, where the question of the value of lymphodepletion is quite controversial due to the potential for such immune suppression to harm endogenous anti-tumor immune responses.

Ultimately, long-term persistence of CAR-NK cells may not be necessary to achieve long term remissions. While loss of functional CAR-T cells has been established in some clinical trials as the single best predictor of relapse, particularly in the setting of some acute and chronic B-cell leukemias (34, 66), persistence of CAR products may be less important in other malignancies, such as lymphomas (53, 67, 68). In diffuse large B cell lymphoma (a non-hodgkin lymphoma) for example, patients can have durable responses without prolonged CAR-T persistence (67, 69, 70). In line with these observations, optimization of CAR design to maximize short-term or long-term responses appears to be disease specific rather than a one size fits all approach (54). Given this evolution in thinking with regard to CAR-T persistence, it is likely that the need for longer term persistence of CAR-NK cells may similarly be disease specific (53). Clinical studies applying different CAR-NK approaches in different disease settinge will be vital to understand how CAR-NK persistence correlates with outcome. Furthermore, an off-the-shelf CAR-NK therapy could make it easier to compensate for lack of persistence through using multiple infusions to maintain a sufficient number of circulating cells for ongoing disease control.

Trafficking

Issues with CAR-T or CAR-NK cells in locating and penetrating into the tumor microenvironment (TME) are thought to be an important limit for the efficacy of the therapy in solid tumors (58). One method to improve CAR trafficking is to engineer cells to express chemokine receptors that can directly enhance their ability to track tumor sites. This strategy has been evaluated in pre-clinical studies (71) and is being explored in an early phase clinical trial where CXCR4 co-expression on an anti- B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) CAR-T was added to increase trafficking to the bone marrow (NCT04727008). Similar to CAR-T cells, NK cells could also benefit from engineered expression of chemokine receptors, as NK cells are known to use chemokine signaling in natural settings (72). NK cells modified to express CXCR2, CXCR4, CCR5, or CCR7 have all been shown to have enhanced tumor control in mice (73–76). In addition, CAR-NK cells engineered to express CXCR1 or CXCR4 also experienced enhanced trafficking to the tumor (74, 77).

Strategies to improve CAR-T trafficking also include attempts to combine with other therapies to make the tumor microenvironment more amenable to lymphocyte recruitment, or modifying the delivery method (direct tumoral injection or systemic delivery) of the CAR therapy (58, 78). The tumor microenvironment can be modified using tools such as oncolytic viruses (OVs) (79), or radiotherapy (80) to increase tumor inflammation (stimulating an immune response) and increase CAR efficacy. While there are substantial studies on combination therapies for CAR-T, combination studies in CAR-NK cells with radiotherapy or OVs are lacking (81). Finally, local injection of CAR-T cells to the tumour, rather than the peripheral blood, improved responses (82–84). This method has also been shown to be safe and efficacious for CAR-NK (85).

Fitness

For CAR-T therapy to be successful after finding the tumor, CAR-expressing cells need to also survive and function in the harsh TME, where considerable barriers prevent the normal function of immune cells. Barriers include: hypoxia, lack of nutrients, low pH, and elevated levels of various metabolic waste products (86). CAR-T cell products with optimized metabolic functions, such as higher oxidative phosphorylation, have been shown to be more efficacious in the clinic as they can overcome these limitations in the TME (87, 88). Two strategies to metabolically improve T cell function in the TME are: i) by direct manipulation of cell metabolism during ex vivo expansion, or ii) genetically engineering T cells to better cope with the TME (89). As in the case of CAR-T cells, NK cells can also be metabolically optimized during expansion either through genetic alterations or by manipulating expansion conditions (90–93).

Looking at examples of ex vivo metabolic engineering of T cells, CD8+ T cells cultured in glutamine restricted conditions had enhanced expression of pro-survival transcription factors and were able to expand better in mice upon reinfusion (94). T cells expanded with mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitors led to decreased tumor burden in mice (95). Finally, T cells were expanded in the presence of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor (PI3K) to enrich for memory T cells in an ongoing BCMA CAR-T clinical trial which is reported to show promising signs of improved efficacy (96). Even the choice of media can have a major impact on the function and metabolism of the T cells (97). Work in NK cells has been carried out to examine the impact of changing feeder cells used for expansion, and how this can affect metabolic fitness and cytotoxicity (98, 99).

Changes to the CAR itself are also known to alter metabolism, as different signaling domains can significantly change glucose or oxidative metabolism in CAR-T cells (100). Additionally, alteration of the cell by knock-out or overexpression of metabolic genes can increase CAR-T cell efficacy. For example, the TME contains low levels of arginine, so overexpressing enzymes for arginine synthesis in T cells has been shown to improve their efficacy in mouse models of leukemia and solid tumors (101). Similarly, overexpression of D-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase in CAR-T cells overcomes the immunosuppressive effects of D-2-hydroxyglutarate in tumors with isocitrate dehydrogenase mutation (102). Genetically engineering NK cells to overcome the immune suppressive effects of metabolites, such as hydrogen peroxide through the expression of peroxiredoxin-1 has been shown to improve NK cell function (103). Much opportunity remains to metabolically optimize CAR-NK therapeutics to thrive in the TME.

Antigen loss

Tumor intrinsic factors also contribute to suboptimal CAR-T responses. This can include immune suppression in the TME through the presence of immunosuppressive cells (e.g. due to cells such as regulatory T cells, myloid derived suppressor cells, tumor associated macrophages, and stromal cells) (104). It can also include resistance due to loss of adhesion molecules on the tumor cells, such as CD58 or ICAM-1 (105, 106), as well as increased expression of apoptotic moleucles (107). The tumor intrinsic factor we will focus on for this section is antigen loss.

Loss of target antigen on tumor cells is an obvious mechanism by which CAR-T therapies fail (108, 109). This may be exacerbated in solid tumors where there is a greater degree of inconsistency in antigen expression (110, 111). Several strategies are under development to circumvent this limitation. Dual-specificity CAR-T cells capable of targeting two separate antigens have achieved strong complete response rates in clinical trials (112–115). Even then, relapses following the loss of at least one antigen have been observed (113–115). Longer follow up and larger trials are needed to determine if these strategies are truly beneficial in reducing relapse and what effect multi-antigen targeting has on CAR-T persistence. Sequential administration of different CAR products has also been explored as a strategy to mitigate tumor antigen loss (116, 117). Furthermore, in preclinical models, combinations with oncolytic viruses, multi-antigen targeting using ankyrin repeat motif CARs, and engineering CAR-T cells to modulate the endogenous immune system are all strategies that have shown promise in limiting relapse by overcoming antigen loss (118–120).

Given the broader antigen independent killing capacity of NK cells, it is possible that CAR-NK cells would have a built-in mechanism for resisting tumor escape due to the loss of CAR target antigen (121, 122). That is, NK cells can rely on their innate killing capabilities rather than on antigen recognition through the CAR alone. However, it is also well established that tumors have the capacity to adapt and evade NK cells both in the context of immunoediting and NK-cell based immunotherapies (123, 124). The implementation of dual target approaches in CAR-NK cells is currently being explored in pre-clinical development (46, 125–128). Clinical experience will show whether loss of multiple antigens is a concern in the context of CAR-NK therapies. However, with either CAR-T or CAR-NKs, identifying better strategies to select the optimal antigen combinations will be critical to creating safe and effective therapies.

Trogocytosis

The term trogocytosis was used in the 1970s to describe the process in which the amoeba, Naegleria fowleri, destroys other cells (129). In 2002, it was adapted to describe the transfer of plasma membrane fragments and associated surface molecules from one cell to another (130). Since then, trogocytosis has been well studied in T and NK cells (131). It has been proposed that trogocytosis provides a mechanism for tissue adaptation of immune cells but can also act as a potent mechanism of immune cell deactivation (132). Trogocytosis has also been documented more recently with CAR-T and CAR-NK cells, causing fratricidal killing and potentially limiting therapeutic efficacy. We will review the consequences of trogocytosis-mediated antigen procurement. Specifically, how this leads to trogocytosis-mediated signaling, target cell antigen loss, and fratricide ( Figure 2 ).

Trogocytosis-mediated signaling

It has been shown that molecules can be transferred between cells via trogocytosis within minutes of contact, and these molecules retain their ability to signal (131), remaining on the cell surface for days (133). Thus, it is important to consider how these acquired proteins change the function of the receiving cell. On one hand, trogocytosis can have positive consequences on NK cell function. For example, NK cells can trogocytose chemokine receptors such as CCR5, CXCR4, or CCR7 (134–136). The acquisition of CCR7 leads to increased NK cell homing to the lymph nodes (135). The acquisition of some molecules, such as TYR03, also increases effector function and proliferation (137). In contrast, trogocytosis can also inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity through the acquisition of immunosuppressive proteins (138–142). In the context of cancer, we found that NK cells acquire PD-1 from leukemia cells (138). In ovarian cancer, NK cells acquire CD9 from ovarian cancer tumor cells, supressing cytotoxicity (139). Despite many studies investigating trogocytosis-mediated signaling, there are few studies proposing methods to counteract these effects. One method to overcome trogocytosis-mediated signaling is to use blocking antibodies against the target antigen. In the case of CD9, NK cell cytotoxicity was restored using a CD9 blocking antibody in vitro (139).

To the best of our knowledge, signaling from receptors transferred via trogocytosis to CAR-T and CAR-NK cells has not yet been explored. Given that antigens targeted by the CAR can be important signaling molecules in tumor cells (such as BCMA in plasma cells, or mesothelin in solid tumors) (143, 144). Acquisition of target molecules by T or NK cells through trogocytosis may also alter cell function in the CAR cells. Future studies could explore the signaling of trogocytosis-acquired molecules in CAR cells and determine if this is a necessary consideration in designing CAR therapies.

Antigen loss

Another consequence of trogocytosis is antigen loss on the target cells. While this has been shown in CAR-NK (145), it is more highly studied in the context of CAR-T (146–148). Since antigen density impacts CAR functionality, downregulation or internalization of the target antigen can lead to tumor escape. Therefore, methods to overcome trogocytosis-induced antigen loss could improve tumor clearance. Trogocytosis may be overcome by tweaking the affinity of the CAR for the target antigen, as low affinity constructs are thought to lead to less trogocytosis while maintaining efficacy (149). Several reports have shown that lower affinity CARs present increased efficacy by preventing tumor escape (147, 149–151); it is tempting to speculate that lower trogocytosis might contribute to this improved function.

Another option to overcome trogocytosis-mediated antigen loss is to adjust the signaling domain of the CAR, as trogocytosis has been shown to affect CARs with CD28 or 4-1BB signaling domain differentially (147). Finally, one interesting study showed that overexpression of cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (CH25H), can lower trogocytosis in CAR-T cells through altered cholesterol metabolism, leading to better outcomes in xenograft models (152). For both T and NK cells, it is not clear at this time whether CAR-expression increases trogocytic transfer by increasing the strength and length of CAR-target cell interaction, or if the antigen-specific binding of the CAR is directly implicated in the process of antigen transfer. More mechanistic studies of trogocytosis in the context of CAR signaling will be needed to better understand the underlying biological processes and how this applies to antigen loss.

Fratricide

In some cases, the ultimate consequence of trogocytosis-mediated antigen transfer to NK cells is NK-mediated killing of other NK cells, a process known as fratricide. In non-genetically modified NK cells trogocytosis of MHC class I-related chain A (MICA) in humans or retinoic acid early-inducible protein 1 (Rae-1) in mice has been shown to lead to fratricidal NK-mediated killing of NK cells (153, 154). This is also a common problem in CAR therapy, when the CAR target antigen is transferred from the tumor to the CAR-T or CAR-NK cell, leading to fratricide of CAR cells (145, 146). In the context of endogenous T or NK antigens like CD7 or CD38 respectively, knockout of the target antigen in the effector cell can overcome fratricidal killing (155, 156), but such an approach would not work for antigens which are transferred to effector cells via trogocytosis. As described above, design of the CAR to limit trogocytosis in CAR-T cells could not only improve antigen loss, but it can also prevent fratricide (147, 149, 152). In the case of NK-CARs, a recent elegant study used an inhibitory receptor targeting an NK-restricted antigen along with the tumour-targeted CAR in order to prevent trogocytosis and improve therapeutic activity (145). Future studies are needed to assess whether specific changes in the design of the various domains of the CAR construct can reduce trogocytosis mediated antigen loss and/or fratricide, and thereby improve the long-term efficacy of both CAR-T and CAR-NK therapies.

Conclusion

While not yet as well understood as CAR-T, CAR-NK have shown promise in early studies treating both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. However, despite the clear conceptual advantages to NK cell-based CAR therapies, and a robust clinical safety record for NK therapies in general, CAR-NK treatments have not had the strong efficacy and/or long-term persistence that are needed. The multiple reasons underlying the struggles for CAR-NK therapy have yet to be fully elucidated but certainly include many of the same challenges which limit CAR-T therapies. Hopefully by applying lessons learned over many years of experience in the CAR-T field, those working with CAR-NK cells will be able to capitalize on the unique assets offered by NK cell biology and create the next generation of revolutionary accessible and affordable cellular therapies.

Author contributions

MK, DB, SL, MA, SM, and AV wrote, edited, and conceptualized the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

SM was funded by the National Research Council Canada Disruptive Technology Solutions Cell and Gene Therapy challenge program. AV was funded by the Myeloma Canada Aldo Del Research Grant. MA was funded by CIHR and a Faculty of Medicine Translational Research Grant.

Conflict of interest

MA received monetary compensation from Alloy Therapeutics for consulting. MA is under a contract agreement to perform sponsored research with Actym Therapeutics and Dragonfly Therapeutics. Neither consulting nor sponsored research is related to the present article.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be constructed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Grigor EJM, Fergusson D, Kekre N, Montroy J, Atkins H, Seftel MD, et al. Risks and benefits of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfus Med Rev (2019) 33:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aamir S, Anwar MY, Khalid F, Khan SI, Ali MA, Khattak ZE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of CD19-specific CAR-T cell therapy in Relapsed/Refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the pediatric and young adult population: safety and efficacy outcomes. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk (2021) 21:e334–47. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grover P, Veilleux O, Tian L, Sun R, Previtera M, Curran E, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in adults with b-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv (2022) 6:1608–18. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J (2021) 11:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miao L, Zhang Z, Ren Z, Tang F, Li Y. Obstacles and coping strategies of CAR-T cell immunotherapy in solid tumors. Front Immunol (2021) 12:687822. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.687822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. June CH, O’Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, Milone MC. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science (2018) 359:1361–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roex G, Timmers M, Wouters K, Campillo-Davo D, Flumens D, Schroyens W, et al. Safety and clinical efficacy of BCMA CAR-t-cell therapy in multiple myeloma. J Hematol Oncol J Hematol Oncol (2020) 13:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-01001-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rebecca Borgert P. Improving outcomes and mitigating costs associated with CAR T-cell therapy (2021). Available at: https://www.ajmc.com/view/improving-outcomes-and-mitigating-costs-associated-with-car-t-cell-therapy. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9. Palani HK, Arunachalam AK, Yasar M, Venkatraman A, Kulkarni U, Lionel SA, et al. Decentralized manufacturing of anti CD19 CAR-T cells using CliniMACS prodigy®: real-world experience and cost analysis in India. Bone Marrow Transpl (2022) 58, 160–167. doi: 10.1038/s41409-022-01866-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kekre N, Hay KA, Webb JR, Mallick R, Balasundaram M, Sigrist MK, et al. CLIC-01: manufacture and distribution of non-cryopreserved CAR-T cells for patients with CD19 positive hematologic malignancies. Front Immunol (2022) 13:1074740. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1074740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ran T, Eichmüller SB, Schmidt P, Schlander M. Cost of decentralized CAR T-cell production in an academic nonprofit setting. Int J Cancer (2020) 147:3438–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cutmore LC, Marshall JF. Current perspectives on the use of off the shelf CAR-T/NK cells for the treatment of cancer. Cancers (2021) 13:1926. doi: 10.3390/cancers13081926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanber K, Savani B, Jain T. Graft-versus-host disease risk after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: the diametric opposition of T cells. Br J Haematol (2021) 195:660–8. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mailankody S, Matous JV, Chhabra S, Liedtke M, Sidana S, Oluwole OO, et al. Allogeneic BCMA-targeting CAR T cells in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: phase 1 UNIVERSAL trial interim results. Nat Med (2023) 29:422–429. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02182-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Depil S, Duchateau P, Grupp SA, Mufti G, Poirot L. ‘Off-the-shelf’ allogeneic CAR T cells: development and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discovery (2020) 19:185–99. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sidaway P. Allogeneic CAR T cells show promise. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2022) 19:748–8. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00703-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Daher M, Rezvani K. Next generation natural killer cells for cancer immunotherapy: the promise of genetic engineering. Curr Opin Immunol (2018) 51:146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xie G, Dong H, Liang Y, Ham JD, Rizwan R, Chen J. CAR-NK cells: a promising cellular immunotherapy for cancer. EBioMedicine (2020) 59:102975. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mueller S, Sohmen M, Kostyra J, Mekes A, Nitsche M, Luevano ME, et al. GMP-compliant, automated process for generation of CAR NK cells in a closed system for clinical use. Cytotherapy (2020) 22:S205–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2020.04.085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oberschmidt O, Morgan M, Huppert V, Kessler J, Gardlowski T, Matthies N, et al. Development of automated separation, expansion, and quality control protocols for clinical-scale manufacturing of primary human NK cells and alpharetroviral chimeric antigen receptor engineering. Hum Gene Ther Methods (2019) 30:102–20. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2019.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sutlu T, Stellan B, Gilljam M, Quezada HC, Nahi H, Gahrton G, et al. Clinical-grade, large-scale, feeder-free expansion of highly active human natural killer cells for adoptive immunotherapy using an automated bioreactor. Cytotherapy (2010) 12:1044–55. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.504770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wagner J, Pfannenstiel V, Waldmann A, Bergs JWJ, Brill B, Huenecke S, et al. A two-phase expansion protocol combining interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-21 improves natural killer cell proliferation and cytotoxicity against rhabdomyosarcoma. Front Immunol (2017) 8:676. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu S, Galat V, Galat4 Y, Lee YKA, Wainwright D, Wu J. NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy: from basic biology to clinical development. J Hematol Oncol J Hematol Oncol (2021) 14:7. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-01014-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gurney M, Kundu S, Pandey S, O’Dwyer M. Feeder cells at the interface of natural killer cell activation, expansion and gene editing. Front Immunol (2022) 13:802906. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.802906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lapteva N, Durett AG, Sun J, Rollins LA, Huye LL, Fang J, et al. Large-Scale ex vivo expansion and characterization of natural killer cells for clinical applications. Cytotherapy (2012) 14:1131–43. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.700767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fujisaki H, Kakuda H, Shimasaki N, Imai C, Ma J, Lockey T, et al. Expansion of highly cytotoxic human natural killer cells for cancer cell therapy. Cancer Res (2009) 69:4010–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson CDL, Zale NE, Frary ED, Lomakin JA. Feeder-Cell-Free and serum-free expansion of natural killer cells using cloudz microspheres, G-Rex6M, and human platelet lysate. Front Immunol (2022) 13:803380. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.803380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gong Y, Klein Wolterink RGJ, Wang J, Bos GMJ, Germeraad WTV. Chimeric antigen receptor natural killer (CAR-NK) cell design and engineering for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol J Hematol Oncol (2021) 14:1–35. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01083-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Colamartino ABL, Lemieux W, Bifsha P, Nicoletti S, Chakravarti N, Sanz J, et al. Efficient and robust NK-cell transduction with baboon envelope pseudotyped lentivector. Front Immunol (2019) 10:2873. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gutierrez-Guerrero A, Abrey Recalde MJ, Mangeot PE, Costa C, Bernadin O, Périan S, et al. Baboon envelope pseudotyped “Nanoblades” carrying Cas9/gRNA complexes allow efficient genome editing in human T, b, and CD34+ cells and knock-in of AAV6-encoded donor DNA in CD34+ cells. Front Genome Ed (2021) 3:604371. doi: 10.3389/fgeed.2021.604371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jo D-H, Kaczmarek S, Shin O, Wang L, Cowan J, McComb S, et al. Simultaneous engineering of natural killer cells for CAR transgenesis and CRISPR-Cas9 knockout using retroviral particles. Mol Ther - Methods Clin Dev (2023) 29:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2023.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Micklethwaite KP, Gowrishankar K, Gloss BS, Li Z, Street JA, Moezzi L, et al. Investigation of product-derived lymphoma following infusion of piggyBac-modified CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood (2021) 138:1391–405. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021010858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moretti A, Ponzo M, Nicolette CA, Tcherepanova IY, Biondi A, Magnani CF, et al. Present, and future of non-viral CAR T cells. Front Immunol (2022) 13:867013. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.867013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fraietta JA, Lacey SF, Orlando EJ, Pruteanu-Malinici I, Gohil M, Lundh S, et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Med (2018) 24:563–71. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0010-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shah NN, Qin H, Yates B, Su L, Shalabi H, Raffeld M, et al. Clonal expansion of CAR T cells harboring lentivector integration in the CBL gene following anti-CD22 CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv (2019) 3:2317–22. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lowry LE, Zehring WA. Potentiation of natural killer cells for cancer immunotherapy: a review of literature. Front Immunol (2017) 8:1061. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shaffer BC, Le Luduec J-B, Forlenza C, Jakubowski AA, Perales M-A, Young JW, et al. Phase II study of haploidentical natural killer cell infusion for treatment of relapsed or persistent myeloid malignancies following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transpl (2016) 22:705–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bachanova V, Burns LJ, McKenna DH, Curtsinger J, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Lindgren BR, et al. Allogeneic natural killer cells for refractory lymphoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother CII (2010) 59:1739–44. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0896-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nguyen R, Wu H, Pounds S, Inaba H, Ribeiro RC, Cullins D, et al. A phase II clinical trial of adoptive transfer of haploidentical natural killer cells for consolidation therapy of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. J Immunother Cancer (2019) 7:81. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0564-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xiao L, Cen D, Gan H, Sun Y, Huang N, Xiong H, et al. Adoptive transfer of NKG2D CAR mRNA-engineered natural killer cells in colorectal cancer patients. Mol Ther J Am Soc Gene Ther (2019) 27:1114–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu Y, Liu Q, Zhong M, Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang Y, et al. 2B4 costimulatory domain enhancing cytotoxic ability of anti-CD5 chimeric antigen receptor engineered natural killer cells against T cell malignancies. J Hematol Oncol J Hematol Oncol (2019) 12:49. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0732-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Christodoulou I, Ho WJ, Marple A, Ravich JW, Tam A, Rahnama R, et al. Engineering CAR-NK cells to secrete IL-15 sustains their anti-AML functionality but is associated with systemic toxicities. J Immunother Cancer (2021) 9:e003894. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Du Z, Ng YY, Zha S, Wang S. piggyBac system to co-express NKG2D CAR and IL-15 to augment the in vivo persistence and anti-AML activity of human peripheral blood NK cells. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev (2021) 23:582–96. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2021.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Morgan MA, Kloos A, Lenz D, Kattre N, Nowak J, Bentele M, et al. Improved activity against acute myeloid leukemia with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-NK-92 cells designed to target CD123. Viruses (2021) 13:1365. doi: 10.3390/v13071365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Teng K-Y, Mansour AG, Zhu Z, Li Z, Tian L, Ma S, et al. Off-the-Shelf prostate stem cell antigen–directed chimeric antigen receptor natural killer cell therapy to treat pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology (2022) 162:1319–33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cichocki F, Goodridge JP, Bjordahl R, Mahmood S, Davis ZB, Gaidarova S, et al. Dual antigen–targeted off-the-shelf NK cells show durable response and prevent antigen escape in lymphoma and leukemia. Blood (2022) 140:2451–62. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021015184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cichocki F, Bjordahl R, Goodridge JP, Mahmood S, Gaidarova S, Abujarour R, et al. Quadruple gene-engineered natural killer cells enable multi-antigen targeting for durable antitumor activity against multiple myeloma. Nat Commun (2022) 13:7341. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35127-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu D-L, He Y-Q, Xiao B, Si Y, Shi J, Liu X-A, et al. A novel sushi-IL15-PD1 CAR-NK92 cell line with enhanced and PD-L1 targeted cytotoxicity against pancreatic cancer cells. Front Oncol (2022) 12:726985. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.726985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu E, Tong Y, Dotti G, Shaim H, Savoldo B, Mukherjee M, et al. Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia (2018) 32:520–31. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu E, Marin D, Banerjee P, Macapinlac HA, Thompson P, Basar R, et al. Use of CAR-transduced natural killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors. N Engl J Med (2020) 382:545–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Foltz JA, Berrien-Elliott MM, Neal C, Foster M, McClain E, Schappe T, et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like (ML) NK cells persist for > 2 months following adoptive transfer into leukemia patients with a MHC-compatible hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT). Blood (2019) 134:1954. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-126004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gang M, Marin ND, Wong P, Neal CC, Marsala L, Foster M, et al. CAR-modified memory-like NK cells exhibit potent responses to NK-resistant lymphomas. Blood (2020) 136:2308–18. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gupta A, Gill S. CAR-T cell persistence in the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma (2021) 62:2587–99. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2021.1913146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weinkove R, George P, Dasyam N, McLellan AD. Selecting costimulatory domains for chimeric antigen receptors: functional and clinical considerations. Clin Transl Immunol (2019) 8:e1049. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Deng Q, Han G, Puebla-Osorio N, Ma MCJ, Strati P, Chasen B, et al. Characteristics of anti-CD19 CAR T cell infusion products associated with efficacy and toxicity in patients with large b cell lymphomas. Nat Med (2020) 26:1878–87. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1061-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang Z, Miao L, Ren Z, Tang F, Li Y. Gene-edited interleukin CAR-T cells therapy in the treatment of malignancies: present and future. Front Immunol (2021) 12:718686. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.718686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yeku OO, Brentjens RJ. Armored CAR T-cells: utilizing cytokines and pro-inflammatory ligands to enhance CAR T-cell anti-tumour efficacy. Biochem Soc Trans (2016) 44:412–8. doi: 10.1042/BST20150291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. White LG, Goy HE, Rose AJ, McLellan AD. Controlling cell trafficking: addressing failures in CAR T and NK cell therapy of solid tumours. Cancers (2022) 14:978. doi: 10.3390/cancers14040978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chmielewski M, Abken H, Talleur AC. TRUCKs: the fourth generation of CARs. Expert Opin Biol Ther (2015) 15(8):1145–54. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2015.1046430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Guo T, Ma D, Lu TK. Sense-and-Respond payload delivery using a novel antigen-inducible promoter improves suboptimal CAR-T activation. ACS Synth Biol (2022) 11:1440–53. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.1c00236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Choi BD, Yu X, Castano AP, Bouffard AA, Schmidts A, Larson RC, et al. CAR-T cells secreting BiTEs circumvent antigen escape without detectable toxicity. Nat Biotechnol (2019) 37:1049–58. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0192-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rudek LS, Zimmermann K, Galla M, Meyer J, Kuehle J, Stamopoulou A, et al. Generation of an NFκB-driven alpharetroviral “All-in-One” vector construct as a potent tool for CAR NK cell therapy. Front Immunol (2021) 12:751138. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.751138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Amini L, Silbert SK, Maude SL, Nastoupil LJ, Ramos CA, Brentjens RJ, et al. Preparing for CAR T cell therapy: patient selection, bridging therapies and lymphodepletion. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2022) 19:342–55. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00607-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, McNearney SA, Yun GH, Fautsch SK, et al. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood (2005) 105:3051–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Caldwell KJ, Gottschalk S, Talleur AC. Allogeneic CAR cell therapy–more than a pipe dream. Front Immunol (2021) 11:618427. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.618427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gardner RA, Finney O, Annesley C, Brakke H, Summers C, Leger K, et al. Intent-to-treat leukemia remission by CD19 CAR T cells of defined formulation and dose in children and young adults. Blood (2017) 129:3322–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-02-769208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, Miklos DB, Lekakis LJ, Oluwole OO, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large b-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol (2019) 20:31–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Majzner RG, Mackall CL. Clinical lessons learned from the first leg of the CAR T cell journey. Nat Med (2019) 25:1341–55. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0564-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kochenderfer JN, Somerville RPT, Lu T, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Feldman SA, et al. Long-duration complete remissions of diffuse Large b cell lymphoma after anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. Mol Ther (2017) 25:2245–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cappell KM, Sherry RM, Yang JC, Goff SL, Vanasse DA, McIntyre L, et al. Long-term follow-up of anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. J Clin Oncol (2020) 38:3805–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Foeng J, Comerford I, McColl SR. Harnessing the chemokine system to home CAR-T cells into solid tumors. Cell Rep Med (2022) 3:100543. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. He Ran G, Qing Lin Y, Tian L, Zhang T, Mei Yan D, Hua Yu J, et al. Natural killer cell homing and trafficking in tissues and tumors: from biology to application. Signal Transduction Targeting Ther (2022) 7:1–21. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01058-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kremer V, Ligtenberg MA, Zendehdel R, Seitz C, Duivenvoorden A, Wennerberg E, et al. Genetic engineering of human NK cells to express CXCR2 improves migration to renal cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer (2017) 5:73. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0275-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ng YY, Du Z, Zhang X, Chng WJ, Wang S. CXCR4 and anti-BCMA CAR co-modified natural killer cells suppress multiple myeloma progression in a xenograft mouse model. Cancer Gene Ther (2022) 29:475–83. doi: 10.1038/s41417-021-00365-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schomer NT, Jiang ZK, Lloyd MI, Klingemann H, Boissel L. CCR7 expression in CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-engineered natural killer cells improves migration toward CCL19-expressing lymphoma cells and increases tumor control in mice with human lymphoma. Cytotherapy (2022) 24:827–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2022.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Li F, Sheng Y, Hou W, Sampath P, Byrd D, Thorne S, et al. CCL5-armed oncolytic virus augments CCR5-engineered NK cell infiltration and antitumor efficiency. J Immunother Cancer (2020) 8:e000131. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ng YY, Tay JCK, Wang S. CXCR1 expression to improve anti-cancer efficacy of intravenously injected CAR-NK cells in mice with peritoneal xenografts. Mol Ther - Oncolytics (2020) 16:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2019.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lin Y-J, Mashouf LA, Lim M. CAR T cell therapy in primary brain tumors: current investigations and the future. Front Immunol (2022) 13:817296. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.817296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ma R, Li Z, Chiocca EA, Caligiuri MA, Yu J. The emerging field of oncolytic virus-based cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer (2023) 9:122–39. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2022.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Qin VM, Haynes NM, D’Souza C, Neeson PJ, Zhu JJ. CAR-T plus radiotherapy: a promising combination for immunosuppressive tumors. Front Immunol (2022) 12:813832. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.813832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lamers-Kok N, Panella D, Georgoudaki A-M, Liu H, Özkazanc D, Kučerová L, et al. Natural killer cells in clinical development as non-engineered, engineered, and combination therapies. J Hematol Oncol J Hematol Oncol (2022) 15:164. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01382-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sagnella SM, White AL, Yeo D, Saxena P, van Zandwijk N, Rasko JEJ. Locoregional delivery of CAR-T cells in the clinic. Pharmacol Res (2022) 182:106329. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Li H, Wang Z, Ogunnaike EA, Wu Q, Chen G, Hu Q, et al. Scattered seeding of CAR T cells in solid tumors augments anticancer efficacy. Natl Sci Rev (2022) 9:nwab172. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwab172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Agliardi G, Liuzzi AR, Hotblack A, De Feo D, Núñez N, Stowe CL, et al. Intratumoral IL-12 delivery empowers CAR-T cell immunotherapy in a pre-clinical model of glioblastoma. Nat Commun (2021) 12:444. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20599-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bae WK, Lee BC, Kim H-J, Lee J-J, Chung I-J, Cho SB, et al. A phase I study of locoregional high-dose autologous natural killer cell therapy with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol (2022) 13:879452. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.879452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Jenkins Y, Zabkiewicz J, Ottmann O, Jones N. Tinkering under the hood: metabolic optimisation of CAR-T cell therapy. Antibodies (2021) 10:17. doi: 10.3390/antib10020017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. van Bruggen JAC, Martens AWJ, Fraietta JA, Hofland T, Tonino SH, Eldering E, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells impair mitochondrial fitness in CD8+ T cells and impede CAR T-cell efficacy. Blood (2019) 134:44–58. doi: 10.1182/blood.2018885863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bai Z, Lundh S, Kim D, Woodhouse S, Barrett DM, Myers RM, et al. Single-cell multiomics dissection of basal and antigen-specific activation states of CD19-targeted CAR T cells. J Immunother Cancer (2021) 9:e002328. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-002328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. O’Sullivan D, Sanin DE, Pearce EJ, Pearce EL. Metabolic interventions in the immune response to cancer. Nat Rev Immunol (2019) 19:324–35. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0140-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Choi C, Finlay DK. Optimising NK cell metabolism to increase the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Stem Cell Res Ther (2021) 12:320. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02377-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Krug A, Martinez-Turtos A, Verhoeyen E. Importance of T, NK, CAR T and CAR NK cell metabolic fitness for effective anti-cancer therapy: a continuous learning process allowing the optimization of T, NK and CAR-based anti-cancer therapies. Cancers (2021) 14:183. doi: 10.3390/cancers14010183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Mangal JL, Handlos JL, Esrafili A, Inamdar S, Mcmillian S, Wankhede M, et al. Engineering metabolism of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) cells for developing efficient immunotherapies. Cancers (2021) 13:1123. doi: 10.3390/cancers13051123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Gardiner CM. NK cell metabolism and the potential offered for cancer immunotherapy. Immunometabolism (2019) 1(1):e190005. doi: 10.20900/immunometab20190005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Nabe S, Yamada T, Suzuki J, Toriyama K, Yasuoka T, Kuwahara M, et al. Reinforce the antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells via glutamine restriction. Cancer Sci (2018) 109:3737–50. doi: 10.1111/cas.13827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Verma V, Jafarzadeh N, Boi S, Kundu S, Jiang Z, Fan Y, et al. MEK inhibition reprograms CD8 + T lymphocytes into memory stem cells with potent antitumor effects. Nat Immunol (2021) 22:53–66. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00818-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Raje NS, Shah N, Jagannath S, Kaufman JL, Siegel DS, Munshi NC, et al. Updated clinical and correlative results from the phase I CRB-402 study of the BCMA-targeted CAR T cell therapy bb21217 in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood (2021) 138:548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-146518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97. MacPherson S, Keyes S, Kilgour M, Smazynski J, Sudderth J, Turcotte T, et al. “Clinically-relevant T cell expansion protocols activate distinct cellular metabolic programs and phenotypes”. Molecular Therapy - Methods & Clinical Development (2021), 24, 380–93. doi: 10.1101/2021.08.24.457536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Yang Y, Badeti S, Tseng H, Ma MT, Liu T, Jiang J-G, et al. Superior expansion and cytotoxicity of human primary NK and CAR-NK cells from various sources via enriched metabolic pathways. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev (2020) 18:428–45. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Liu E, Ang SOT, Kerbauy L, Basar R, Kaur I, Kaplan M, et al. GMP-compliant universal antigen presenting cells (uAPC) promote the metabolic fitness and antitumor activity of armored cord blood CAR-NK cells. Front Immunol (2021) 12:626098. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.626098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kawalekar OU, O’Connor RS, Fraietta JA, Guo L, McGettigan SE, Posey AD, et al. Distinct signaling of coreceptors regulates specific metabolism pathways and impacts memory development in CAR T cells. Immunity (2016) 44:380–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Fultang L, Booth S, Yogev O, Martins da Costa B, Tubb V, Panetti S, et al. Metabolic engineering against the arginine microenvironment enhances CAR-T cell proliferation and therapeutic activity. Blood (2020) 136:1155–60. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Yang Q, Hao J, Chi M, Wang Y, Li J, Huang J, et al. D2HGDH-mediated D2HG catabolism enhances the anti-tumor activities of CAR-T cells in an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Mol Ther (2022) 30:1188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Klopotowska M, Bajor M, Graczyk-Jarzynka A, Kraft A, Pilch Z, Zhylko A, et al. PRDX-1 supports the survival and antitumor activity of primary and CAR-modified NK cells under oxidative stress. Cancer Immunol Res (2022) 10:228–44. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Liu Z, Zhou Z, Dang Q, Xu H, Lv J, Li H, et al. Immunosuppression in tumor immune microenvironment and its optimization from CAR-T cell therapy. Theranostics (2022) 12:6273–90. doi: 10.7150/thno.76854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Yan X, Chen D, Ma X, Wang Y, Guo Y, Wei J, et al. CD58 loss in tumor cells confers functional impairment of CAR T cells. Blood Adv (2022) 6:5844–56. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022007891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ramkumar P, Abarientos AB, Tian R, Seyler M, Leong JT, Chen M, et al. CRISPR-based screens uncover determinants of immunotherapy response in multiple myeloma. Blood Adv (2020) 4:2899–911. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Rasche L, Vago L, Mutis T. Tumour escape from CAR-T cells. In: Kröger N, Gribben J, Chabannon C, Yakoub-Agha I, Einsele H, editors. The EBMT/EHA CAR-T cell handbook. Cham: Springer International Publishing; (2022). p. 15–22. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-94353-0_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ruella M, Maus MV. Catch me if you can: leukemia escape after CD19-directed T cell immunotherapies. Comput Struct Biotechnol J (2016) 14:357–62. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, Rives S, Boyer M, Bittencourt H, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with b-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med (2018) 378:439–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Majzner RG, Mackall CL. Tumor antigen escape from CAR T-cell therapy. Cancer Discovery (2018) 8:1219–26. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Martinez M, Moon EK. CAR T cells for solid tumors: new strategies for finding, infiltrating, and surviving in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol (2019) 10:128. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Mei H, Li C, Jiang H, Zhao X, Huang Z, Jin D, et al. A bispecific CAR-T cell therapy targeting BCMA and CD38 in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Hematol Oncol J Hematol Oncol (2021) 14:161. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01170-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Spiegel JY, Patel S, Muffly L, Hossain NM, Oak J, Baird JH, et al. CAR T cells with dual targeting of CD19 and CD22 in adult patients with recurrent or refractory b cell malignancies: a phase 1 trial. Nat Med (2021) 27:1419–31. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01436-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Dai H, Wu Z, Jia H, Tong C, Guo Y, Ti D, et al. Bispecific CAR-T cells targeting both CD19 and CD22 for therapy of adults with relapsed or refractory b cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol J Hematol Oncol (2020) 13:30. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00856-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Furqan F, Shah NN. Bispecific CAR T-cells for b-cell malignancies. Expert Opin Biol Ther (2022) 22:1005–15. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2022.2086043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Yan L, Qu S, Shang J, Shi X, Kang L, Xu N, et al. Sequential CD19 and BCMA-specific CAR T-cell treatment elicits sustained remission of relapsed and/or refractory myeloma. Cancer Med (2021) 10:563–74. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Meng Y, Deng B, Rong L, Li C, Song W, Ling Z, et al. Short-interval sequential CAR-T cell infusion may enhance prior CAR-T cell expansion to augment anti-lymphoma response in b-NHL. Front Oncol (2021) 11:640166. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.640166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Wing A, Fajardo CA, Posey AD, Shaw C, Da T, Young RM, et al. Improving CART-cell therapy of solid tumors with oncolytic virus-driven production of a bispecific T-cell engager. Cancer Immunol Res (2018) 6:605–16. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Balakrishnan A, Rajan A, Salter AI, Kosasih PL, Wu Q, Voutsinas J, et al. Multispecific targeting with synthetic ankyrin repeat motif chimeric antigen receptors. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2019) 25:7506–16. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Kuhn NF, Purdon TJ, van Leeuwen DG, Lopez AV, Curran KJ, Daniyan AF, et al. CD40 ligand-modified chimeric antigen receptor T cells enhance antitumor function by eliciting an endogenous antitumor response. Cancer Cell (2019) 35:473–488.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Valeri A, García-Ortiz A, Castellano E, Córdoba L, Maroto-Martín E, Encinas J, et al. Overcoming tumor resistance mechanisms in CAR-NK cell therapy. Front Immunol (2022) 13:953849. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.953849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Elahi R, Heidary AH, Hadiloo K, Esmaeilzadeh A. Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered natural killer (CAR NK) cells in cancer treatment; recent advances and future prospects. Stem Cell Rev Rep (2021) 17:2081–106. doi: 10.1007/s12015-021-10246-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Sordo-Bahamonde C, Vitale M, Lorenzo-Herrero S, López-Soto A, Gonzalez S. Mechanisms of resistance to NK cell immunotherapy. Cancers (2020) 12:893. doi: 10.3390/cancers12040893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Groth A, Klöss S, von Strandmann EP, Koehl U, Koch J. Mechanisms of tumor and viral immune escape from natural killer cell-mediated surveillance. J Innate Immun (2011) 3:344–54. doi: 10.1159/000327014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Davis Z, Cichocki F, Felices M, Wang H, Hinderlie P, Juckett M, et al. A novel dual-antigen targeting approach enables off-the-Shelf CAR NK cells to effectively recognize and eliminate the heterogenous population associated with AML. Blood (2022) 140:10288–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-168981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Roex G, Campillo-Davo D, Flumens D, Shaw PAG, Krekelbergh L, De Reu H, et al. Two for one: targeting BCMA and CD19 in b-cell malignancies with off-the-shelf dual-CAR NK-92 cells. J Transl Med (2022) 20:124. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03326-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Luanpitpong S, Poohadsuan J, Klaihmon P, Issaragrisil S. Selective cytotoxicity of single and dual anti-CD19 and anti-CD138 chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer cells against hematologic malignancies. J Immunol Res (2021) 2021:5562630. doi: 10.1155/2021/5562630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Wang J, Toregrosa-Allen S, Elzey BD, Utturkar S, Lanman NA, Bernal-Crespo V, et al. Multispecific targeting of glioblastoma with tumor microenvironment-responsive multifunctional engineered NK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2021) 118:e2107507118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107507118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Brown T. Observations by immunofluorescence microscopy and electron microscopy on the cytopathogenicity of naegleria fowleri in mouse embryo-cell cultures. J Med Microbiol (1979) 12:363–71. doi: 10.1099/00222615-12-3-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Joly E, Hudrisier D. What is trogocytosis and what is its purpose? Nat Immunol (2003) 4:815. doi: 10.1038/ni0903-815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Reed J, Reichelt M, Wetzel SA. Lymphocytes and trogocytosis-mediated signaling. Cells (2021) 10:1478. doi: 10.3390/cells10061478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Miyake K, Karasuyama H. The role of trogocytosis in the modulation of immune cell functions. Cells (2021) 10:1255. doi: 10.3390/cells10051255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Vanherberghen B, Andersson K, Carlin LM, Nolte-`t Hoen ENM, Williams GS, Höglund P, et al. Human and murine inhibitory natural killer cell receptors transfer from natural killer cells to target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2004) 101:16873–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406240101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Vo D-N, Leventoux N, Campos-Mora M, Gimenez S, Corbeau P, Villalba M. NK cells acquire CCR5 and CXCR4 by trogocytosis in people living with HIV-1. Vaccines (2022) 10:688. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Somanchi SS, Somanchi A, Cooper LJN, Lee DA. Engineering lymph node homing of ex vivo–expanded human natural killer cells via trogocytosis of the chemokine receptor CCR7. Blood (2012) 119:5164–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-389924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Marcenaro E, Cantoni C, Pesce S, Prato C, Pende D, Agaugué S, et al. Uptake of CCR7 and acquisition of migratory properties by human KIR+ NK cells interacting with monocyte-derived DC or EBV cell lines: regulation by KIR/HLA-class I interaction. Blood (2009) 114:4108–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-222265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Lu T, Ma R, Li Z, Mansour AG, Teng K-Y, Chen L, et al. Hijacking TYRO3 from tumor cells via trogocytosis enhances NK-cell effector functions and proliferation. Cancer Immunol Res (2021) 9:1229–41. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Hasim MS, Marotel M, Hodgins JJ, Vulpis E, Makinson OJ, Asif S, et al. When killers become thieves: trogocytosed PD-1 inhibits NK cells in cancer. Sci Adv (2022) 8:eabj3286. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj3286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Gonzalez VD, Huang Y-W, Delgado-Gonzalez A, Chen S-Y, Donoso K, Sachs K, et al. High-grade serous ovarian tumor cells modulate NK cell function to create an immune-tolerant microenvironment. Cell Rep (2021) 36(9):109632. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Caumartin J, Favier B, Daouya M, Guillard C, Moreau P, Carosella ED, et al. Trogocytosis-based generation of suppressive NK cells. EMBO J (2007) 26:1423–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. López-Cobo S, Romera-Cárdenas G, García-Cuesta EM, Reyburn HT, Valés-Gómez M. Transfer of the human NKG2D ligands UL16 binding proteins (ULBP) 1–3 is related to lytic granule release and leads to ligand retransfer and killing of ULBP-recipient natural killer cells. Immunology (2015) 146:70–80. doi: 10.1111/imm.12482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Roda-Navarro P, Vales-Gomez M, Chisholm SE, Reyburn HT. Transfer of NKG2D and MICB at the cytotoxic NK cell immune synapse correlates with a reduction in NK cell cytotoxic function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2006) 103:11258–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600721103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Avula LR, Rudloff M, El-Behaedi S, Arons D, Albalawy R, Chen X, et al. Mesothelin enhances tumor vascularity in newly forming pancreatic peritoneal metastases. Mol Cancer Res MCR (2020) 18:229–39. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Coquery CM, Erickson LD. Regulatory roles of the tumor necrosis factor receptor BCMA. Crit Rev Immunol (2012) 32:287–305. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v32.i4.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Li Y, Basar R, Wang G, Liu E, Moyes JS, Li L, et al. KIR-based inhibitory CARs overcome CAR-NK cell trogocytosis-mediated fratricide and tumor escape. Nat Med (2022) 28:2133–44. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02003-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Schoutrop E, Renken S, Micallef Nilsson I, Hahn P, Poiret T, Kiessling R, et al. Trogocytosis and fratricide killing impede MSLN-directed CAR T cell functionality. OncoImmunology (2022) 11:2093426. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2022.2093426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Hamieh M, Dobrin A, Cabriolu A, van der Stegen SJC, Giavridis T, Mansilla-Soto J, et al. CAR T cell trogocytosis and cooperative killing regulate tumour antigen escape. Nature (2019) 568:112–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1054-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Camviel N, Wolf B, Croce G, Gfeller D, Zoete V, Arber C, et al. And antibody-fragment-based CAR T cells for myeloma induce BCMA downmodulation by trogocytosis and internalization. J Immunother Cancer (2022) 10:e005091. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-005091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Olson ML, Mause ERV, Radhakrishnan SV, Brody JD, Rapoport AP, Welm AL, et al. Low-affinity CAR T cells exhibit reduced trogocytosis, preventing rapid antigen loss, and increasing CAR T cell expansion. Leukemia (2022) 36:1943–6. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01585-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Ghorashian S, Kramer AM, Onuoha S, Wright G, Bartram J, Richardson R, et al. Enhanced CAR T cell expansion and prolonged persistence in pediatric patients with ALL treated with a low-affinity CD19 CAR. Nat Med (2019) 25:1408–14. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0549-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Mao R, Kong W, He Y. The affinity of antigen-binding domain on the antitumor efficacy of CAR T cells: moderate is better. Front Immunol (2022) 13:1032403. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1032403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Lu Z, McBrearty N, Chen J, Tomar VS, Zhang H, Rosa GD, et al. ATF3 and CH25H regulate effector trogocytosis and anti-tumor activities of endogenous and immunotherapeutic cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cell Metab (2022) 34:1342–1358.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. McCann FE, Eissmann P, Onfelt B, Leung R, Davis DM. The activating NKG2D ligand MHC class I-related chain a transfers from target cells to NK cells in a manner that allows functional consequences. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 (2007) 178:3418–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Nakamura K, Nakayama M, Kawano M, Amagai R, Ishii T, Harigae H, et al. Fratricide of natural killer cells dressed with tumor-derived NKG2D ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2013) 110:9421–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300140110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Cooper ML, Choi J, Staser K, Ritchey JK, Devenport JM, Eckardt K, et al. An ‘off-the-shelf’ fratricide-resistant CAR-T for the treatment of T cell hematologic malignancies. Leukemia (2018) 32:1970–83. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0065-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Gurney M, Stikvoort A, Nolan E, Kirkham-McCarthy L, Khoruzhenko S, Shivakumar R, et al. CD38 knockout natural killer cells expressing an affinity optimized CD38 chimeric antigen receptor successfully target acute myeloid leukemia with reduced effector cell fratricide. Haematologica (2020) 107:437–45. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.271908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]