Short abstract

Women's military experiences and post-service needs often differ from those of men. More research focused on this population will help ensure that policies and programs adequately support veteran women's transitions from military to civilian life.

Keywords: Female Populations, Veterans Health Care

Abstract

Women's military experiences and post-service needs often differ from those of men. More research focused on this population will help ensure that policies and programs adequately support veteran women's transitions from military to civilian life.

Women's military experiences and post-service needs often differ from those of men. The current U.S. veteran population includes 2 million women—and that number is growing. However, policies and programs to support veterans’ transitions to civilian life often fall short in meeting the needs of veteran women.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) adopted its mission statement in 1959: “To care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan” (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, undated b, emphasis added). The origins of the phrase date back even further—to President Abraham Lincoln's second inaugural address in 1865. Each year since 2018, the U.S. House of Representatives has introduced legislation to make VA's motto more inclusive of veteran women, a move backed by recommendations from the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services. The most recent—the Honoring All Veterans Act (H.R. 2806, 2021)—would clarify that VA's mission extends to veterans—including women—as well as veterans’ families, caregivers, and survivors.

Meeting the Needs of a Growing Population of Veteran Women

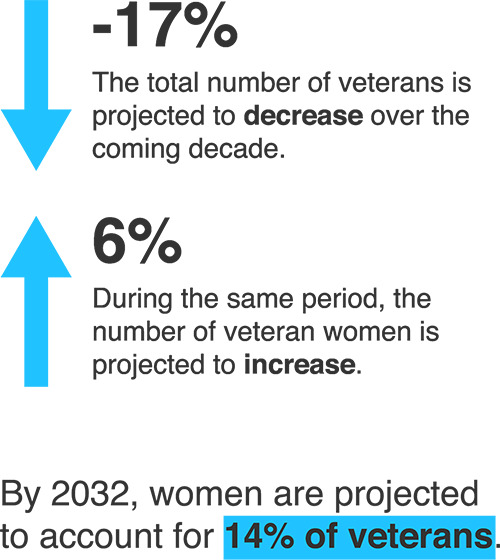

The VA mission statement is a symptom of a broader tendency to associate veteran status with men. Public debates about women's service in combat units and their historic “firsts,” like completing Ranger School, have brought attention to women service members and made them very visible to the public. Women have also historically been the most visible within the military; because of their limited numbers and differential dress and grooming standards, they do not “blend in” with their peers. Women service members often face scrutiny from commanders and peers who are men and find it difficult to fully assimilate with their units. Yet, when they transition to civilian life, they become “invisible,” not recognized as veterans in the same way as their male peers (Goldstein, 2018; Thomas and Hunter, 2019). As a result, their presence has historically been overlooked, their contributions underappreciated, and their needs underexamined and underresourced (VA Center for Women Veterans, 2022). Women are the fastest-growing population of service members and veterans and, according to the Veterans Health Administration, they account for 30 percent of new patients (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022b). As Figure 1 indicates, even as the overall number of veterans declines, the population of veteran women is projected to increase over the coming decade. By 2032, at least 14 percent of veterans will be women, compared with approximately 10 percent today (VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2021).

Figure 1.

Projected Changes in the Number of Veterans and the Number of Veteran Women by 2032

SOURCE: VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2021.

NOTES: Between 2022 and 2032, the overall number of veterans was expected to decline from 18.8 million to 15.6 million, while the number of veteran women was expected to increase from 2.06 million to almost 2.17 million.

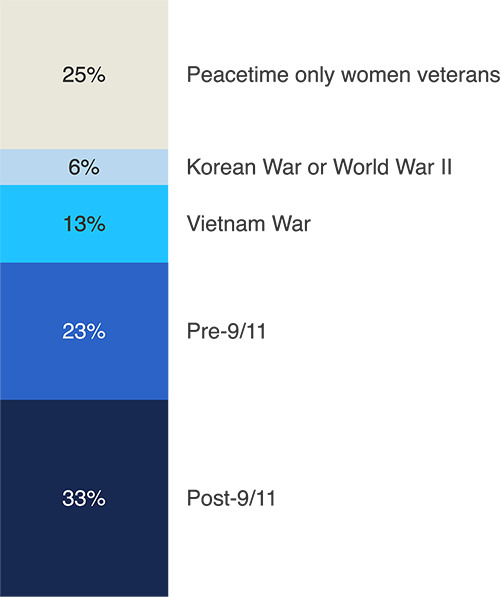

After September 11, 2001, more than 300,000 women deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, where they accounted for more than 11 percent of all U.S. service members deployed to those theaters (VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2017, p. 5). Approximately one-third of veteran women served in the post-9/11 era, as shown in Figure 2 (VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2017, p. 12).

Figure 2.

Veteran Women, by Service Era

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017, p. 12.

Pressing Issues

Veteran women differ from veteran men and their nonveteran peers—and so do their needs.

Research on veteran women and the policies and programs intended to support them must account for the many ways in which this subpopulation is distinct and how these differences could affect veteran women's post-service needs. Table 1 highlights some key characteristics of veteran women compared with veteran men and nonveteran women that should be considered when developing, implementing, and monitoring the impact of initiatives to support veteran women.

Table 1.

Comparing Veteran Women, Veteran Men, and Nonveteran Women on Key Characteristics

| Characteristic | Veteran Women | Veteran Men | Nonveteran Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (average) | 51 | 65 | 47 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Nonwhite, non-Hispanic | 25.3% | 14.8% | 21.0% |

| Hispanic | 9.5% | 7.1% | 16.6% |

| Household composition | |||

| Divorced or separated | 22.8% | 15.2% | 12.5% |

| Children living in the household | 30.4% | 15.3% | 33.0% |

| Employment and financial status | |||

| Unemployed | 4.2% | 4.4% | 5.1% |

| Living in poverty | 9.4% | 6.4% | 13.7% |

| Median earnings among those working full-time year-round ($) | $40,939 | $50,986 | $29,999 |

SOURCES: Unless otherwise indicated, data are from the 2017 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample and reported in VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2019. Data on unemployment are from 2021 and reported in U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2022a and 2022b.

These differences can have a range of implications for programs and services that aim to be inclusive of today's veterans and the support that would provide the most benefit to veteran women as they transition from military to civilian life:

The average veteran woman is 51 years old—14 years younger than the average veteran man but four years older, on average, than women who have not served. Veteran women's needs change over their lifetimes, and programs and interventions that target the “typical veteran” might fall short in addressing those needs.

Veteran women are more racially and ethnically diverse than veteran men. The largest share of those who identify as a racial/ethnic minority are Black or African American (18.9 percent) or Hispanic (9.5 percent) (VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2019).

-

Veteran women are more likely than veteran men and nonveteran women to be divorced or separated, and they tend to marry at younger ages than nonveteran women:

According to 2015 U.S. Census data, veteran women were less likely than their nonveteran peers to marry more than once in their lifetimes (16.2 percent versus 28.5 percent) (VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2017, p. 16). Although this data point does not capture the range of possible long-term partnerships, it does imply that veteran women are more likely than their peers who never served to bear baseline day-to-day costs (such as for housing) on their own.

Veteran women were less likely to follow the prevailing U.S. trend of marrying at later ages. Thirty percent were married by the age of 24, compared with 8 percent of their nonveteran peers (VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2017, p. 16).

Those who marry young are more likely to experience divorce (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Although veteran women ages 18–34 were more likely than nonveteran women to be married (45.1 percent versus 29.6 percent), this trend reversed with age: Veteran women ages 35–64 were less likely to be married than their nonveteran peers (Lofquist, 2017).

The overall share of veteran and nonveteran women with children living at home was similar. However, nearly half (49.1 percent) of veteran women ages 18–34 had at least one child in their household, compared with 33.4 percent of nonveteran women (Lofquist, 2017). This implies that veteran women are responsible for caring for children at younger ages when their income and careers may be less stable. On the flip side, veteran women are less likely to be balancing childcare needs during their peak earning years later in life.

Some differences between veteran women and men highlight a potential need for policies and programs that address the higher prevalence of risk factors among veteran women that contribute to their 9.4-percent poverty rate (compared with 6.4 percent for veteran men) and the growing rates of homelessness among veteran women (Montgomery, 2020). For example, around half of veteran women have a bachelor's degree or higher, compared with around 30 percent of veteran men (Wenger and Ward, 2022); despite the greater tendency to invest time and money (for those who do not qualify for military education benefits) in attaining a college degree, veteran women who work full-time earn less pay. It is worth noting, however, that the unemployment rate among veteran women and men is similar.

A one-size-fits-all approach to military-to-civilian transition support often fails to meet women's needs.

The federal Transition Assistance Program connects outgoing military personnel with education and employment opportunities, housing resources, health care benefits, and other services. It was designed to meet the transition needs of as many veterans as possible. A 2020 review found that, despite reforms, the program continued to have a “narrow focus on employment, education, and benefits” while overlooking complex challenges and barriers that can have a significant impact on veterans’ transition experiences, such as establishing and maintaining social connections after military service and coping with the effects of trauma exposure (Whitworth et al., 2020).

In 2020, the Wounded Warrior Project surveyed and conducted roundtable discussions with its veteran women members to get their views on their transition experiences. Participants reported that they often learned about available services strictly by chance, through conversations with commanders or other veterans. Many found that the information they received through the Transition Assistance Program “was not relevant to their needs, especially as it relates to care and services for women's health and for those experiencing military sexual trauma” (Wounded Warrior Project, 2021, p. 22). However, they indicated that the program was most useful when it came to preparing them for the civilian workforce by providing résumé-writing help and opportunities to practice interviewing for jobs.

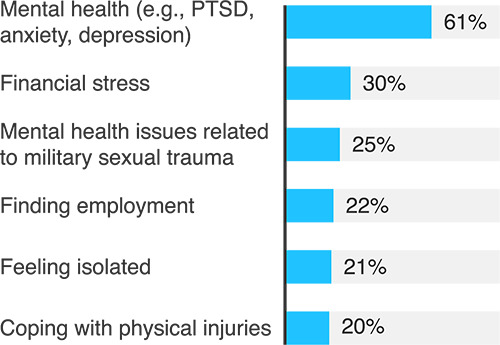

Figure 3 shows the top transition-related challenges highlighted by veteran women surveyed by the Wounded Warrior Project. Mental health, both in general and related to military sexual trauma, was a serious concern. And nearly one-third of respondents indicated that financial stress was a top concern and had negatively affected their transition to civilian life (Wounded Warrior Project, 2021).

Figure 3.

Top Transition-Related Challenges Cited in a 2020 Survey of Veteran Women

SOURCE: Wounded Warrior Project, 2021, pp. 4, 21.

NOTES: Respondents were asked to indicate their top three challenges. The survey data reflect responses from 4,871 veteran women who were affiliated with the Wounded Warrior Project, 2 percent of whom were serving in the reserve component and 1 percent of whom were on active duty in the military.

Overall, research on the military-to-civilian transition needs and experiences of women, specifically, remains limited (Thomas and Hunter, 2019). Data collection efforts that have included needs assessments of veteran women have documented shortfalls in services targeting this group—as well as among racial/ethnic minority veterans, veterans who live in rural areas, and other veteran subpopulations (Perkins, Aronson, and Olson, 2017). It is clear that the status quo is not necessarily addressing the diverse needs of a changing veteran population.

Growing awareness of health care access barriers prompted Congress to mandate the expansion of the Women's Health Transition Training that supplements and attempts to address gaps in the Transition Assistance Program, first piloted in 2018 (Pub. L. 116-92, 2020). The training serves as a starting point in meeting the gender-specific health care needs of veteran women, and the online format enhances access to the training. However, with an exclusive focus on health care, the program is limited in addressing some of the social and economic factors that can affect women's transitions to civilian life.

VA might not be meeting veteran women's needs for mental health care, including for combat trauma and military sexual trauma.

Until 2013, women were subject to the combat exclusion policy, which restricted them from serving in ground combat arms units or positions (Miller et al., 2012). In reality, the blurred lines of the battlefield and women's integration across military occupational specialties meant that women were participating in combat operations long before the policy officially changed (Miller et al., 2012). The post-9/11 generation of veteran women is leaving the military at a time when perspectives on women's military service are still catching up to this reality. Despite deploying to the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, many veteran women still feel that they are not viewed as “real” combat veterans (Hunter, 2021).

In 2009, nearly 75 percent of a representative sample of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans reported being exposed to multiple traumatic situations while deployed, such as seeing a friend wounded or killed or being injured (data were not presented for men and women separately; Tanielian, 2009). Men and women alike experienced combat trauma in those conflicts, leaving 11–20 percent with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (VA National Center for PTSD, 2022). The VA system was not originally structured to provide specialized care for veteran women with combat trauma, and there has been little research on how women's combat experiences affect their support needs or the extent to which existing treatment options address women's combat experiences.

Veteran women experience PTSD at higher rates than veteran men. In an analysis of a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, the past-year prevalence of PTSD was 11.7 percent for veteran women compared with 6.7 percent for veteran men and 6 percent for nonveteran women (Lehavot, 2018).

PTSD can also result from military sexual trauma. Sexual trauma is associated with PTSD symptoms at rates equal to or higher than combat experiences or civilian sexual assault (Burkhart and Hogan, 2015; Street et al., undated). In 2014, RAND researchers surveyed 170,000 service members about their experiences with sexual assault, sexual harassment, and gender discrimination in the military. Nearly 5 percent of women reported being sexually assaulted in the year prior to the survey, often by a peer or supervisor, and 22 percent of women reported experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace (Morral et al., 2015). These rates were even higher in the 2018 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active-Duty Members, with 6.2 percent of women reporting being sexually assaulted in the previous year (U.S. Department of Defense, Office of People Analytics, 2019). VA also screens all veterans who seek care for a history of military sexual trauma; one in three women and one in 50 men report having experienced military sexual trauma in these screenings (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2021).

Compared with veteran men, veteran women also have higher rates of depression, eating disorders, and other mental and behavioral health conditions (Rivera and Johnson, 2014). In 2018, the suicide rate among veteran women was 14.8 per 100,000—almost twice the rate for nonveteran women (Ramchand, 2021).

Often, the mental health impact of trauma and physical stress responses resulting from those experiences manifest many years later, well after a veteran has left the military (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2021). Veterans who have experienced combat and/or sexual trauma may require various degrees of support at different times in their lives, highlighting a need for ongoing support after veterans’ transition to civilian life. Regardless of their eligibility for VA benefits, most veterans can receive free treatment for the effects of military sexual trauma, and all VA medical centers and community-based vet centers offer these services (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2021). To supplement the care veterans receive, VA recently launched Beyond MST, a self-service mobile app for survivors of military sexual trauma, along with toolkits for private-sector providers who treat veteran women. Furthermore, every VA medical center has a women's mental health champion, and VA has begun to provide training in gender-specific care for combat and other types of trauma (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022b).

Although VA is well positioned to provide culturally competent care—that is, to approach veterans’ needs with an adequate level of familiarity with military and veteran culture—it remains an open question whether VA providers are consistently equipped to provide culturally competent care to veteran women, specifically. On the other hand, community care providers often lack military and veteran cultural competency generally and for veteran women specifically (Tanielian et al., 2014). VA does address the needs of veteran women as part of its Community Provider Toolkit (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, undated a), but there is a need to evaluate the structure and impact of initiatives to improve the cultural competency of veteran women's mental health care across settings.

Despite the progress toward inclusion across the U.S. Department of Defense and VA, a 2021 study of VA care access and availability found that women still often felt unwelcome at VA facilities and even experienced harassment while seeking care (Marshall, 2021). One study randomly sampled veteran women who were receiving care through VA, finding that 25 percent had experienced harassment at a VA facility (Klap et al., 2019). On a 2015 VA survey, 60 percent of women who used VA care indicated that women-only clinics were very important, but only 30 percent currently received care at a VA women's clinic (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015b, p. 110).

Veteran women continue to face barriers to gender-specific physical health care through VA.

VA has been taking steps to better address the health care needs of veteran women. A 2021 Congressional Research Service report recounted the progress that VA had made from a nearly exclusive focus on veteran men to providing a wide range of gender-specific physical and mental health care for women, although it noted that VA continued to offer only limited maternity and newborn care (Sussman, 2021). The VA's Office of Women's Health oversees enhancements to women's services and collects significant amounts of data on those who use them. However, despite this progress, gaps remain in terms of research, support, and understanding of veteran women's health care needs.

Legislation passed in 2020 and 2021 has attempted to address gaps in VA care for veteran women. The Deborah Sampson Act of 2020, signed into law as part of a broader package of improvements to veteran services at the federal level, promoted the VA office dedicated to monitoring access, quality, and disparities in the care and services provided to veteran women (Pub. L. 116-315, 2021). The Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act required VA to improve access to information about available mental health care resources (Pub. L. 116-171, 2020). The recently signed Making Advances in Mammography and Medical Options (MAMMO) for Veterans Act (Pub. L. 117-135, 2022) requires VA to improve access to mammograms and related care and to create a strategic plan to monitor its progress. The Protecting Moms Who Served Act of 2021 (Pub. L. 117-69) requires the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) to report on the mortality and morbidity of pregnant and postpartum veteran women. These reforms are recent, so there is little research on their implementation, and data are only beginning to be collected on their impact. However, so much legislative focus on improving women's health care in VA highlights policymakers’ concerns that women's needs are not being addressed.

On the Wounded Warrior Project's 2020 survey of veteran women, fewer than half (49 percent) of respondents agreed that VA met their health care needs in general (Wounded Warrior Project, 2021, p. 23). Consistent themes in the research on women's access to and satisfaction with VA care have been that the gender-specific care they need is not available through VA and that there are barriers to accessing care when it is available. Studies indicate that a lack of VA providers trained in women's health and insufficient coordination with community providers are two significant factors that limit veteran women's access to VA care (Marshall et al., 2021). Nonetheless, veteran women are more likely than veteran men to receive all their health care from VA providers (18.9 percent versus 11.4 percent) (VA National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2019).

Despite a slew of headlines over the previous decade, a 2020 report from the VA Office of the Inspector General found that one of the nation's largest VA health systems had no full-time gynecologist for almost two years, and the system's primary care providers dedicated to women's health were so short-staffed and responsible for so many patients that appointment times did not allow them to deliver what they viewed as adequate gender-specific care (VA Office of the Inspector General, 2020). Patients were often referred to community-based providers because of a lack of appointments and providers at their nearest VA facility, but there was no systematic process for sharing records with VA afterward. In the absence of these records, there is a risk that patients will not receive adequate follow-up care and treatment, nor will their care be coordinated in an integrated manner, which is a noted benefit of VA health care. In addition to long timelines to fill staff vacancies, the report also found deficiencies in supplies, equipment, and space allocated for women's health care (VA Office of the Inspector General, 2020).

Four years earlier, a GAO study found that 27 percent of VA facilities had no onsite gynecologist. The agency inspected six VA medical centers and flagged several examples of inadequate practices, particularly for outpatient care, including a lack of privacy curtains in examinations and acoustics that made it possible to overhear provider-patient conversations (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2016, p. 16). The report also noted that 40 percent of examination and procedure spaces inspected had unsecured doors or were otherwise accessible to those who were not authorized staff, providers, or patients (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2016, pp. 16–17).

Veteran women have family planning needs that are often unmet.

A gap in veteran women's health care that has not been addressed is the need for family planning services. Most women who serve in the military are in their prime childbearing years, and they often face difficult choices about when to start a family. Research indicates that, by the time women leave the military, they are significantly more likely to experience infertility than U.S. women overall but only half as likely to receive treatment (Coloske, 2021). VA offers extensive infertility services, though veterans face strict eligibility criteria for in vitro fertilization (IVF) under current law, including a requirement to be married and to not have an injury that requires the use of an egg or sperm donor (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017). These limitations mean that many veteran women who wish to pursue parenthood via IVF must decide whether to take on a significant financial burden (Coloske, 2021).

Abortion care is an additional component of family planning. The U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization in June 2022, which overturned Roe v. Wade, prompted concerns about access to abortion services for service members and their families, as well as for veterans. TRICARE, the military health insurance program, pays for abortions for service members and their eligible dependents in cases of rape, incest, or life-threatening complications (TRICARE, 2022). Historically, VA benefits have not covered abortion services or counseling on abortion, with no exceptions for rape, incest, or life-threatening complications (38 C.F.R. 17.38). VA also has not been paying for abortion services performed by private providers or travel expenses related to the procedure (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015a). This policy was based on a narrow interpretation of the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992 (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2022a; Schwartz et al., 2018; Pub. L. 102–585, 1992). With states implementing their own laws on abortion, service members and veterans are facing a patchwork of availability and access barriers across the United States (Myers, 2022).

Providing a glimpse at the potential impact of state-level policies, a 2018 survey of almost 2,300 veteran women found that they were slightly more likely to report having an abortion than their civilian peers and that abortion rates were higher among veteran women who were low-income and had experienced homelessness or housing instability (Schwartz et al., 2018). Economically vulnerable veterans are likely to face financial and logistical barriers, such as limited access to transportation to see out-of-state providers, that could compound the impact on this population as state-level policies banning abortion take effect. The White House and the Secretary of Veterans Affairs have come under pressure from veterans’ groups to take executive action (“Biden Faces Pressure to End Abortion Ban Within the Department of Veterans Affairs,” 2022; Shane, 2022). On September 1, 2022, VA announced that it had submitted an interim final rule to allow abortion counseling and access to abortion services when the life or health of a pregnant veteran was in danger or when the pregnancy was a result of rape or incest (VA Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, 2022).

Directions for Future Research

Many veterans have difficulty transitioning to civilian life, but women are more likely to face certain challenges, such as dismissive assumptions about their service, the effects of military sexual trauma, and the need to balance work and caregiving responsibilities. Veteran women differ from veteran men demographically, in their needs, and in the issues they face.

Although research focused on veteran women is expanding, many surveys and needs assessments suffer from small sample sizes, sampling bias, or limited geographic coverage (for example, a single VA health system). Military and VA administrative records include data on the characteristics of this population, but it can be difficult to determine whether and to what extent community-based providers, programs, and services are meeting women veterans’ needs because of limitations on data collection from these sources.

Women overall remain underrepresented in many types of research (Perez, 2019), but that is beginning to change for veteran women. Compounding the barriers of limited services, poor experiences at VA health care facilities, and the need to balance caregiving and other responsibilities is the dearth of research into the associations between veteran women's mental and physical health, post-service transition challenges, and long-term outcomes. The following lines of research may lead to targeted improvements in the well-being of veteran women and can benefit post-service support for veterans overall.

Collect more feedback on women's transition experiences and explore opportunities to customize transition support in response to their needs. For example, the federal Transition Assistance Program is intended to serve as many transitioning service members as possible. As a result, it was developed primarily on men's experiences in the military and their common post-transition needs. Ongoing data collection and program evaluation would improve understanding of where needs are not being met—among both women and other veteran subpopulations.

Examine the root causes of disparities in labor force representation and earnings between veteran women and men. Despite higher levels of educational attainment, veteran women report more difficulty finding employment after military service, and they earn significantly less than veteran men. There is a need to examine whether employment support services are meeting women's needs and to identify opportunities to better support their career transitions.

Identify how combat exposure affects veteran women's mental and physical health. The historical legacy of the combat exclusion policy may limit understanding of how women are affected by combat exposure and increase the risk of underdiagnosis. Additional research would help providers better identify how mental and physical health conditions associated with combat trauma present in women compared with men, including PTSD and traumatic brain injury.

Evaluate the effectiveness of community-based support options for veteran women. Despite the availability of multiple VA and community-based support options for veterans who have experienced trauma, there have been few evaluations of their effectiveness and veteran women's long-term outcomes, including their risk of experiencing homelessness.

Ensure that veteran women are aware of available support for combat and military sexual trauma. The VA policy extending care for military sexual trauma to all veterans has likely improved support for veterans who are not otherwise eligible for VA care. However, trauma during military service can remain a challenge for veterans long after they transition to civilian life. VA should develop strategies to engage veterans over the long term to maintain awareness of this benefit and encourage veterans to seek support when they need it.

Monitor barriers to veteran women's access to VA care and other sources of support. Research suggests that women's health providers are not consistently available across the VA system, and outsourcing of women's care remains a common practice. Women also report feeling unwelcome at VA facilities. Routine data collection on veteran women who receive VA care and those who seek care elsewhere, including through the VA Community Care Program, will give VA leaders and policymakers a clearer picture of the effects of recent congressional reforms to address these barriers, providing evidence to guide improvements and allocate resources in ways that will offer the greatest benefit to veteran women.

Additional Resources

Data on women veterans

VA's National Center for Veteran Analysis and Statistics (https://www.va.gov/vetdata/) is a clearinghouse for national and state-level data on the demographic characteristics of veteran populations, their use of benefits and services, their health and employment outcomes, and more.

The U.S. Department of Labor's Veterans’ Employment and Training Service (https://www.dol.gov/agencies/vets/womenveterans/womenveterans-relevant-research) collects the latest research and data on women veterans’ employment, education, housing and food security, transitions to civilian life, and other topics.

The U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Veterans Affairs has launched the Women Veterans Task Force (https://veterans.house.gov/women-veterans-taskforce/) to facilitate congressional oversight of VA culture, health care, employment opportunities, and equal access to benefits by women veterans. Task force hearings provide updates on the status of initiatives in these areas.

More information about VA benefits and services for veteran women

VA provides primary care and specialty services specifically for veteran women (https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/). Its Women Veterans Call Center can assist with benefit enrollment, scheduling appointments, and answering eligibility questions.

VA's Center for Women Veterans (https://www.va.gov/womenvet/) monitors and coordinates VA benefits, services, and programs specifically targeting veteran women. The center also collaborates with the U.S. Department of Defense to help women access VA health care services as they transition out of the military.

For veterans who have experienced military sexual trauma, VA offers a range of services (https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/msthome/index.asp) that are not restricted to those who meet the eligibility criteria for VA care, including the self-service mobile app Beyond MST (https://mobile.va.gov/app/beyond-mst).

Community-based support for veteran women

Several veteran-serving organizations offer resources and advocate for improved support for women who have served in the U.S. military. The following are a few examples:

Lifeline for Vets (https://nvf.org/women-veterans-support/), part of the National Veterans Foundation, offers support for veteran women as they transition from military service to civilian life, with a focus on overcoming traditional barriers to accessing benefits and other resources.

The Women Veterans Network (https://www.wovenwomenvets.org/) is a peer-support organization that provides virtual and in-person opportunities to network and learn from the experiences of other veteran women.

Women Vets on Point (https://womenvetsonpoint.org/) is a nonprofit organization that connects veteran women with local mental health services, VA benefits, and employment and housing support.

Notes

Funding for this article was made possible by a generous gift from Daniel J. Epstein through the Epstein Family Foundation, which established the RAND Epstein Family Veterans Policy Research Institute in 2021. The institute is dedicated to conducting innovative, evidence-based research and analysis to improve the lives of those who have served in the U.S. military. Building on decades of interdisciplinary expertise at the RAND Corporation, the institute prioritizes creative, equitable, and inclusive solutions and interventions that meet the needs of diverse veteran populations while engaging and empowering those who support them. For more information about the RAND Epstein Family Veterans Policy Research Institute, visit veterans.rand.org.

References

- Biden Faces Pressure to End Abortion Ban Within the Department of Veterans Affairs PBS NewsHour. July 7, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/biden-faces-pressure-to-end-abortion-ban-within-the-department-of-veterans-affairs “. ,” video and transcript, , . As of July 2022: .

- Burkhart Lisa, and Hogan Nancy Being a Female Veteran: A Grounded Theory of Coping with Transitions Social Work in Mental Health March 4, 2015;13(2):108. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2013.870102. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Code of Federal Regulations, Title 38, Pensions, Bonuses, and Veterans’ Relief, Section 17.38, U.S. . Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Benefits Package.

- Coloske Marissa Health Affairs Forefront. July 22, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210715.658223/full , “The Right to Serve, but Not to Carry: Expanding Access to Infertility Treatment for US Veterans,” . , . As of July 2022: .

- Goldstein Andrea N. Women Are the Most Visible Servicemembers, and the Most Invisible Veterans. March 8, 2018. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/women-are-the-most-visible-soldiers-and-the-most-invisible-veterans , “. ,” Center for a New American Security, . As of July 2022: .

- House Resolution 2806 Honoring All Veterans Act, 117th Congress. April 29, 2021. , , .

- Hunter Kyleanne 'In Iraq, We Were Never Neutral’: Exploring the Effectiveness of ‘Gender-Neutral’ Standards in a Gendered World Journal of Veterans Studies 2021;7(2):6. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [Google Scholar]

- Klap Ruth, Darling Jill E., Hamilton Alison B., Rose Danielle E., Dyer Karen, Canelo Ismelda, Haskell Sally, and Yano Elizabeth M. Prevalence of Stranger Harassment of Women Veterans at Veterans Affairs Medical Centers and Impacts on Delayed and Missed Care Women's Health Issues March–April 2019;29(2):107. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.12.002. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot Keren, Katon Jodie G., Chen Jessica A., Fortney John C., and Simpson Tracy L. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder by Gender and Veteran Status American Journal of Preventive Medicine January 2018;54(1):e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.09.008. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofquist Daphne A. Characteristics of Female Veterans: An Analytic View Across Age-Cohorts: 2015. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau; August 30, 2017. , , : , . [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Vanessa, Stryczek Krysttel C., Haverhals Leah, Young Jessica, Au David H., Ho P. Michael, Kaboli Peter J., Kirsh Susan, and Sayre George The Focus They Deserve: Improving Women Veterans’ Health Care Access Women's Health Issues July–August 2021;31(4):399. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2020.12.011. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Laura L., Kavanaugh Jennifer, Lytell Maria C., Jennings Keith, and Martin Craig . The Extent of Restrictions on the Service of Active-Component Military Women. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, MG-1175-OSD; 2012. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG1175.html , , : , . As of July 2022: . [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery Ann Elizabeth VAntage Point Blog. March 31, 2020. https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/73113/va-research-reveals-circumstances-can-lead-homelessness-women-veterans , “VA Research Reveals Circumstances That Can Lead to Homelessness Among Women,” . , . As of July 2022: .

- Morral Andrew, Gore Kristie L., Schell Terry L., Bicksler Barbara, Farris Coreen, Ghosh-Dastidar Bonnie, Jaycox Lisa H., Kilpatrick Dean, Kistler Steve, Street Amy, Tanielian Terri, and Williams Kayla M. Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment in the U.S. Military: Highlights from the 2014 RAND Military Workplace Study. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RB-9841-OSD; 2015. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9841.html , , : , . As of July 2022: . [Google Scholar]

- Myers Meghann Military Times. June 28, 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2022/06/28/dod-looks-to-protect-troops-civilian-employees-from-prosecution-over-new-abortion-laws , “DoD Looks to Protect Troops, Civilian Employees from Prosecution over New Abortion Laws,” . , . As of July 2022: .

- Perez Caroline Criado . Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. New York: Abrams Press; 2019. , , , , . [Google Scholar]

- Perkins D. F., Aronson K. R., and Olson J. R. Supporting United States Veterans: A Review of Veteran-Focused Needs Assessments from 2008–2017. University Park, Pa.: Clearinghouse for Military Family Readiness, Penn State University; November 2017. https://militaryfamilies.psu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/SupportUSVeterans_HQC.pdf , , : , . As of July 2022: . [Google Scholar]

- Public Law 102-585 Veterans Health Care Act of 1992. November 4, 1992. , , .

- Public Law 116-92 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. December 20, 2019. , , .

- Public Law 116-171 Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019. October 17, 2020. , , .

- Public Law 116-315 Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, M.D., Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020. January 5, 2021. , , .

- Public Law 117-69 Protecting Moms Who Served Act of 2021. November 30, 2021. , , .

- Public Law 117-135 Making Advances in Mammography and Medical Options (MAMMO) for Veterans Act. June 7, 2022. , , .

- Ramchand Rajeev . Suicide Among Veterans: Veterans’ Issues in Focus. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, PE-A1363-1; 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA1363-1.html , , : , . As of July 2022: . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Jessica C., and Johnson Anthony E. Female Veterans of Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom: Status and Future Directions Military Medicine February 2014;179(2):133. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00425. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Eleanor Bimla, Sileanu Florentina E., Zhao Xinhua, Mor Maria K., Callegari Lisa S., and Borrero Sonya Induced Abortion Among Women Veterans: Data from the ECUNN Study Contraception January 2018;97(1):41. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.09.012. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shane Leo III Military Times. June 29, 2022. https://www.militarytimes.com/veterans/2022/06/29/no-plans-to-increase-abortion-services-at-va-after-supreme-court-ruling , “No Plans to Increase Abortion Services at VA After Supreme Court Ruling,” . , . As of July 2022: .

- Street Amy, Skimore Chris, Gyuro Lisa, and Bell Margaret Military Sexual Trauma. , “. ,” National Center for PTSD, undated.

- Sussman Jared S. Veterans Health Administration: Gender-Specific Health Care Services for Women Veterans. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, IF11082; March 11, 2021. , , : , . [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian Terri . Assessing Combat Exposure and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Troops and Estimating the Costs to Society: Implications from the RAND Invisible Wounds of War Study, testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Veterans' Affairs, Subcommittee on Disability Assistance and Memorial Affairs. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; March 24, 2009. https://www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CT321.html , , : , CT-321, . As of July 2022: . [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian Terri, Farris Coreen, Batka Caroline, Farmer Carrie M., Robinson Eric, Engel Charles C., Robbins Michael W., and Jaycox Lisa H. Ready to Serve: Community-Based Provider Capacity to Deliver Culturally Competent, Quality Mental Health Care to Veterans and Their Families. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2014. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR806.html , , : , RR-806-UNHF, . As of July 2022: . [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Kate Hendricks, and Kyleanne Hunter eds . Invisible Veterans: What Happens When Military Women Become Civilians Again. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger; 2019. ., , : , . [Google Scholar]

- TRICARE Covered Services: Abortions. March 20, 2022. https://tricare.mil/CoveredServices/IsItCovered/Abortions , “. ,” webpage, last updated . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Table 2B. Employment Status of Men 18 Years and Over by Veteran Status, Age, and Period of Service, 2021 Annual Averages. April 21, 2022a. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/vet.t02B.htm , “. ,” . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Table 2C. Employment Status of Women 18 Years and Over by Veteran Status, Age, and Period of Service, 2021 Annual Averages. April 21, 2022b. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/vet.t02C.htm , “. ,” . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Census Bureau Number, Timing and Duration of Marriages and Divorces. April 22, 2021. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021/marriages-and-divorces.html , “. ,” press release, . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Defense Office of People Analytics 2018 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of the Active Duty Military: Results and Trends. May 2019. , , Washington, D.C., .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Community Provider Toolkit: Women Veterans. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/communityproviders/veterans-women.asp , “. ,” webpage, undated a. As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs The Origin of the VA Motto: Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/celebrate/vamotto.pdf , “. ,” Washington, D.C., undated b. As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Benefits Exclusions. June 3, 2015a. https://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/access/exclusions.asp , “. ,” webpage, last updated . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Study of Barriers for Women Veterans to VA Health Care: Final Report. April 2015b. , , Washington, D.C., .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs VA Infertility Services. November 2017. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/docs/InfertilityBrochure_FINAL_508.pdf , “. ,” factsheet, . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Women Veterans in Focus. October 30, 2020. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/VHA-WomensHealth-Focus-Infographic-v20-sm-508b.pdf , “. ,” factsheet, . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Military Sexual Trauma. May 2021. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/mst_general_factsheet.pdf , “. ,” factsheet, . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs VA Women's Health Services. February 15, 2022a. https://www.va.gov/health-care/health-needs-conditions/womens-health-needs , “. ,” webpage, last updated . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Women Veterans Health Care: About Us. May 25, 2022b. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/about-us.asp , “. ,” webpage, last updated . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Women Veterans I Am Not Invisible. March 10, 2022. https://www.va.gov/womenvet/iani/index.asp , “. ,” webpage, last updated . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD How Common is PTSD in Veterans? March 23, 2022. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp , “. ” webpage, last updated . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics Women Veterans Report: The Past, Present, and Future of Women Veterans. February 2017. , , Washington, D.C., .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics Profile of Veterans: 2017. March 2019. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2017.pdf , “. ,” briefing slides, . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, national veteran population tables, by age and gender. April 14, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp , , last updated . . As of July 2022: .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of the Inspector General Deficiencies in the Women Veterans Health Program and Other Quality Management Concerns at the North Texas Healthcare System. January 23, 2020. , , Washington, D.C., .

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Public and Affairs Intergovernmental VA Will Offer Abortion Counseling and—in Certain Cases—Abortions to Pregnant Veterans and VA Beneficiaries. September 2, 2022. , “. ,” press release, .

- U.S. Government Accountability Office VA Health Care: Improved Monitoring Needed for Effective Oversight of Care for Women Veterans. December 2016. , , Washington, D.C., GAO-17-52, .

- Wenger Jennie W., and Ward Jason M. The Role of Education Benefits in Supporting Veterans as They Transition to Civilian Life: Veterans’ Issues in Focus. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, PE-A1363-4; 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA1363-4.html , , : , . As of July 2022: . [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth James, Smet Ben, and Anderson Brian Reconceptualizing the U.S. Military's Transition Assistance Program: The Success in Transition Model Journal of Veterans Studies 2020;6(1):25. , “. ,” . , Vol. , No. , , pp. –. . [Google Scholar]

- Wounded Warrior Project Women Warriors Initiative Report. 2021. , , Jacksonville, Fla., .