Abstract

Bioadhesives are an important class of biomaterials for wound healing, hemostasis, and tissue repair. To develop the next generation of bioadhesives, there is a societal need to teach trainees about their design, engineering, and testing. This study designed, implemented, and evaluated a hands-on, inquiry-based learning (IBL) module to teach bioadhesives to undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral trainees. Approximately 30 trainees across three international institutions participated in this IBL bioadhesives module, which was designed to last approximately 3 h. This IBL module was designed to teach trainees about how bioadhesives are used for tissue repair, how to engineer bioadhesives for different biomedical applications, and how to assess the efficacy of bioadhesives. The IBL bioadhesives module resulted in significant learning gains for all cohorts; whereby, trainees scored an average of 45.5% on the pre-test assessment and 69.0% on the post-test assessment. The undergraduate cohort experienced the greatest learning gains of 34.2 points, which was expected since they had the least theoretical and applied knowledge about bioadhesives. Validated pre/post-survey assessments showed that trainees also experienced significant improvements in scientific literacy from completing this module. Similar to the pre/post-test, improvements in scientific literacy were most significant for the undergraduate cohort since they had the least amount of experience with scientific inquiry. Instructors can use this module, as described, to introduce undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral trainees to principles of bioadhesives.

Keywords: Bioadhesive, Biomaterials, Tissue repair, Inquiry-based learning, Hands-on experiment, Engineering education

INTRODUCTION

Bioadhesives and Biomedical Engineering Education

Biomaterials is an interdisciplinary field that uses principles of biology, chemistry, medicine, materials science, and engineering to develop materials capable of interacting with biological systems.40 Since the 1940s, biomaterials have found use as medical implants, methods to promote tissue healing, molecular probes and biosensors, drug delivery systems, and scaffolds to regenerate human tissues.6 As a result of their profound benefits to human health, biomaterials are projected to have global revenues of $348.4 billion by 2027.18 Additionally, there is a projected increase in the employment of bioengineers up to 6% by 2030.5 One important class of biomaterials for tissue healing and repair is bioadhesives, which are designed to adhere biological components together.26 Clinically, bioadhesives are used to stop internal fluid leaks52 and aid in surgical wound healing.29 Furthermore, experimental bioadhesives are designed to seal soft tissue defects and repair orthopaedic tissues.36,46 Of note, the current state of bioadhesives for orthopaedic tissue repair does not result in complete healing, or regeneration.19 However, bioadhesives may be used to deliver cells37,51 or other bioactive factors12,30 for improved repair. To meet these societal and economic demands for biomaterials that repair tissues, there is a need to educate trainees about biomaterial design, engineering, and testing.7,24

Numerous education modules exist to supplement lectures and provide students with formative, hands-on experiences to learn about biomaterials. For example, educational modules were designed to teach trainees about films,42 fiber-reinforced ceramic composites, polyvinyl alcohol polymers,48 and alginate-polyacrylamide hydrogels.20 These types of hands-on modules are crucial for solidifying concepts of biomaterials and connecting theoretical content to practical applications.44 To the authors’ knowledge, there are no published modules to teach trainees about bioadhesives. This lack of published educational modules on bioadhesives represents a major gap in biomaterials education. The lack of bioadhesives modules limits early exposure of trainees to the field and ultimately may limit advances made in the field of bioadhesives for tissue repair.

Pedagogical Framework

Traditional learning involves direct instruction by teachers who provide knowledge to students through lectures.28 Teachers structure lectures to satisfy curriculum requirements and students take exams to benchmark their knowledge.14,39 Critiques of traditional learning highlight numerous limitations with this pedagogical model. First, traditional learning is a teacher-centered approach that creates a power imbalance between the instructor and the student. The instructor holds the authority due to their expertise and students receive knowledge that they cannot question.25 Furthermore, direct instruction typically lacks opportunities for student engagement, which produces active and non-active learners, depending on the student’s interests and abilities. Another drawback is that exams can lead to superficial learning, as students can perform very well by memorizing and repeating tested material, rather than truly internalizing and understanding the content.4 This leads to students obtaining a superficial understanding of the material and not developing the critical thinking skills necessary for careers in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).4 Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is one pedagogical model that is suggested to overcome these challenges.

In the IBL model, students communicate with one another and work collaboratively to construct their own knowledge as they are learning the material.10 IBL encourages students to communicate the material in discussions with teachers and fellow students, cite evidence and outside observations, generate explanations based on prior scientific knowledge along with what is being taught in the course, and communicate their findings through written work and presentations.3 In a study performed with middle school students, it was found that learning outcomes were significantly greater for students taught with an IBL approach, compared to those who learned from a traditional learning model.17 Inspired by successes with middle school students, the Promoting Inquiry in Mathematics and Science Education Across Europe (PRIMAS) Project was conducted across 14 institutions in 12 European countries to test the efficacy of IBL in STEM at the primary and secondary education levels. The outcomes of the project showed that IBL fostered superior learner competence to traditional learning techniques.13 For these reasons, the bioadhesive module described was created using an IBL approach.

Research Objectives

This study designed, implemented, and evaluated an IBL module about bioadhesives for tissue repair that would last approximately 3 h. This module was designed to teach trainees about how bioadhesives are used for tissue repair, how to engineer bioadhesives for different biomedical applications, and how to assess the efficacy of bioadhesives. This module focused on two broad mechanisms of bioadhesion: (1) mechanical interlocking and (2) chemical interactions at the tissue-bioadhesive interface.11 Cyanoacrylate was chosen as a mechanical interlocking bioadhesive because it is FDA-approved and commonly used for surgical applications.16 Gelatin was chosen as a bioadhesive that adheres through chemical interactions because it is biocompatible, biodegradable, and easily tunable via additional crosslinking agents.1 Glutaraldehyde (GTA) was chosen to crosslink gelatin because it is the crosslinking agent in BioGlue (Cryolife, Atlanta, GA), a commercially available bioadhesive.8 These bioadhesives were used to adhere two different substrates together: (1) chamois, which has a protein-rich surface necessary for chemical crosslinking and (2) 3D-printed polylactic acid (PLA), which is bioinert. Trainees tested their bioadhesives quantitatively using a lap-shear configuration according to ASTM 2255-05 testing protocol.45 This testing configuration was chosen to teach students about standardized materials testing methods through the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), an internationally-recognized standards organization.

This IBL bioadhesives module was implemented with an undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral cohort to test its effectiveness at multiple education levels. This module was implemented at multiple education levels because of the potential benefits that could be achieved for trainees with different backgrounds. For example, undergraduate trainees would have had little previous exposure to bioadhesives or scientific inquiry; thus, it was hypothesized that completing this module could educate undergraduate trainees about bioadhesives and enhance their scientific literacy. While master’s and PhD/postdoctoral trainees would have had more experience with scientific inquiry, their training would be specialized and does not necessarily include knowledge of bioadhesives. Therefore, it was hypothesized that completing this module could introduce master’s and PhD/postdoctoral trainees with different backgrounds to principles of bioadhesives. In doing so, these more advanced trainees could benefit by incorporating principles of bioadhesives into their primary research focus.

This IBL bioadhesives module was evaluated to determine if it (1) promoted positive learning outcomes and (2) enhanced scientific literacy for cohorts at multiple education levels. Learning gains were assessed using pre/post-test assessments and scientific literacy was assessed using validated pre/post-survey assessments. Overall, the goal was for this module to promote positive learning gains and enhance scientific literacy for a wide-range of trainees with limited knowledge of bioadhesives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Instructors at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art prepared the following solutions for the undergraduate cohort prior to the start of the module: 5% (w/v) gelatin (Knox Unflavored Gelatin, Amazon, Amazon Standard Identification Number (ASIN): B001UOW7D80) in deionized (DI) water, 2% (v/v) glutaraldehyde (GTA, Glutaraldehyde Grade II, Sigma Aldrich, G6257-1L) in DI water, and cyanoacrylate (Gorilla Gel Super Glue, Amazon, ASIN: B08FXWWMCM) diluted in a 1:7 volumetric ratio with acetone (Acetone, ACS, 99.5+%, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 30698). In addition, instructors pre-prepared 2 × 6 cm pieces of two different substrates: chamois (Car Nature Chamois Real Leather Washing Cloth Cleaning Towel Wipes Clean Cham H88, Amazon, ASIN: B06XNPFDK3) and polylactic acid (PLA, True Black Filament - 1.75 mm, 1 kg Spool, HATCHBOX 3D). PLA samples were designed using SOLIDWORKS® 2021 (SOLIDWORKS®, Vélizy, France) and 3D-printed using an Original Prusa i3 MK3 machine with 0.4 mm nozzle (Prusa Research, Prague, Czech Republic). Both substrates had plastic safety ties (Plastic Tag Fastener Snap Lock 3” Pin, Amazon, ASIN: B074W3V1KD) threaded through a small hole 5 mm from the top of the substrate.

Since the activity was deployed at multiple institutions in multiple countries, it was not possible to purchase the exact same materials for each cohort. Instructors at ETH Zürich and the Riga Technical University prepared almost identical materials for the master’s and PhD/postdoctoral cohorts, respectively. All materials were identical, except the following: chamois (Fruugo®, Fruugo ID: 54959165–111733109) and nylon string tag hang fasteners (Fruugo®, Fruugo ID: 41722887–85150056). These materials were chosen for their similarity to those used in the undergraduate cohort.

Trainee Demographics and Lab Groups

Trainees in the undergraduate cohort were enrolled in a multidisciplinary elective engineering course called Biomaterials, which was open to all students at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art as early as their sophomore year. Thirteen trainees took the course in Fall 2021 and most of these trainees were chemical engineering majors (one master’s, two seniors, and six juniors). Additionally, the cohort included two mechanical engineering majors (one junior and one sophomore), one sophomore general engineering major, and one junior art major. Trainees chose their own laboratory groups of 3–4 trainees.

Trainees in the master’s cohort were enrolled in a course called Practical Methods in Tissue Engineering, which was open to master’s students at ETH Zürich. Twelve trainees took the course in Fall 2021. The cohort included seven biomedical engineering majors and five health science and technology majors. Trainees chose their own laboratory groups of 3–4 trainees.

Trainees in the PhD/postdoctoral cohort were participants in the RISEus2 1st Winter School, which was a program open to early-stage researchers and other interested parties from Rudolfs Cimdins Riga Biomaterials Innovations and Development Centre of Riga Technical University (RTU RBIDC) and other RTU RBIDC national long-term collaboration partners. All trainees in this cohort were studying materials science and chemical technology and did not have a specific background in biomaterials. Twenty-two trainees participated in the program. Ten of the trainees were first and second year PhD students, eight were postdoctoral trainees, and four were master’s students. Trainees chose their own laboratory groups of 3–4 trainees.

Pre-Laboratory Lecture and Exercise

The entire IBL bioadhesives module was designed to last approximately 3 h. This 3 h session included a pre-laboratory lecture and exercise, bioadhesives application, and bioadhesives testing. One instructor led the pre-laboratory exercise for the undergraduate cohort and a different instructor led the pre-laboratory exercise for the master’s and PhD/postdoctoral cohorts. For the pre-laboratory exercise, instructors presented each cohort with a brief background on bioadhesives that included an introduction to the topic and the common mechanisms of adhesion. The presentation was similar for all cohorts. After this lecture, trainees formed their laboratory groups and instructors guided trainees through a pre-laboratory exercise using an inquiry-based learning (IBL) approach. During these sessions, trainees discussed the independent variables they would be manipulating (e.g., gelatin concentration), their mechanical testing scheme, quantifiable output measurements, and specific hypotheses they would test. These trainee-led discussions ensured all group members had an appropriate level of background knowledge to conduct this bioadhesive modules and were comfortable using IBL techniques. Additionally, the IBL module was trainee-led, meaning that instructors were facilitators of the hands-on activity and answered questions, but trainees were responsible for manipulating independent variables and recording quantifiable output measurements.

Bioadhesive Application Procedure

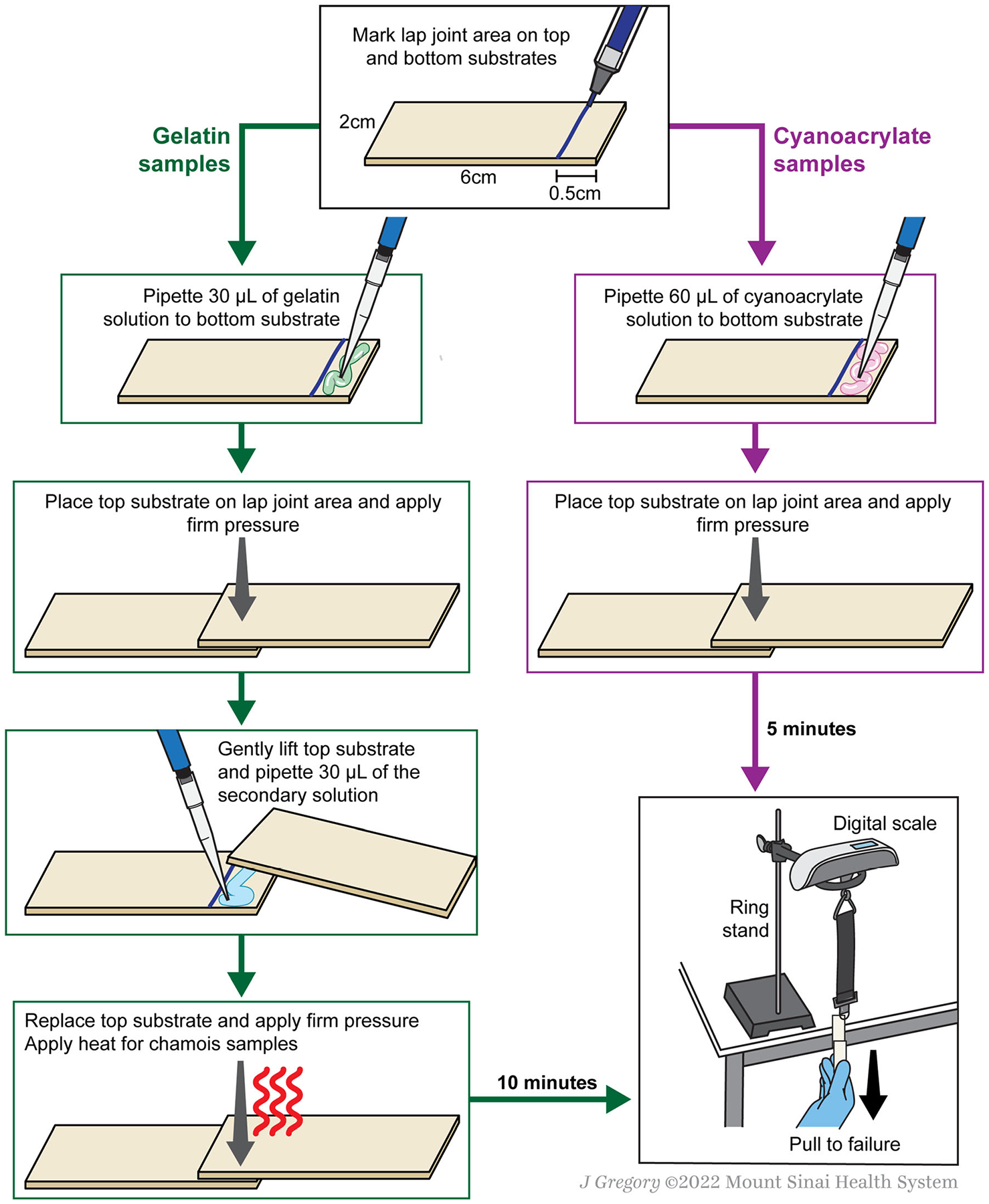

Trainees in all cohorts followed the procedure outlined in Fig. 1 for adhering two substrates. First, trainees drew a horizontal line 0.5 cm from the bottom of two pieces of the substrate to be tested (i.e., chamois or PLA). This line marked the lap joint area of the bioadhesive for each sample. For the GTA-crosslinked gelatin bioadhesives, the experimental procedure suggested trainees use a 1:1 volumetric ratio of the gelatin and GTA solutions for each sample. Thus, trainees pipetted 30 μL of the gelatin solution onto the lap joint area of the bottom substrate, placed the top substrate on the lap joint area, and applied firm pressure. Then, trainees gently lifted the top substrate and pipetted 30 μL of a secondary solution between the two substrates. The secondary solution for experimental conditions was 30 μL of the GTA solution. For uncrosslinked controls, the secondary solution was 30 μL of gelatin instead of the GTA solution. Trainees also included a control by pipetting 30 μL of DI water as the secondary solution instead of the GTA to account for dilution of gelatin by the GTA. After pipetting the secondary solution, trainees replaced the top substrate, applied firm pressure, and left samples to dry at room temperature for 10 min with a flat, weighted object (e.g., textbook) to hold the lap joint area together. For the chamois samples, heat was applied for a few seconds on both sides using a heat gun immediately after adding the secondary solution and placing the two substrates together. To modify adhesion strength, trainees varied the concentration of GTA from 0 to 2% (v/v) and the volumetric ratio of gelatin:GTA from 1:1 to 1:4, while holding the total volume constant at 60 μL. These concentration ranges were provided by instructors based on previous experimentation with the materials.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram showing the procedure of adhering two substrates together for the inquiry-based learning (IBL) bioadhesives module.

Trainees used a similar procedure for adhering chamois and PLA substrates using the prepared cyanoacrylate solution; however, there was no secondary solution. Trainees pipetted 60 μL of the cyanoacrylate solution to the bottom substrate in one step, placed the top substrate over the lap joint area, and applied firm pressure. Samples were left to dry at room temperature for 5 min with a flat, weighted object (e.g., textbook) to hold the lap joint area together. The cyanoacrylate solution was diluted 1:7 (v/v) with acetone to enable a more consistent application and to allow for measurable results before the safety tie or non-lap joint area broke.

Bioadhesive Testing Procedure

Trainees in the undergraduate and PhD/postdoctoral cohorts created a lap-shear testing apparatus to test the adhesive strength of their bioadhesives on different substrates (Fig. 1). The lap-shear configuration was chosen to mimic ASTM 2255-05, an internationally recognized protocol for testing the strength properties of tissue adhesives.45 The testing apparatus consisted of a digital luggage scale (Dr. Meter Backlit LCD Display Electronic Balance Digital Hanging Scale with Rubber Paint Handle, Amazon, ASIN: B07FR6M7M9) placed on top of a ring clamp connected to a ring stand. To test each sample, trainees looped the safety ties on the samples around the bottom hook of the luggage scale. Then, trainees pulled the bottom substrate of the sample in a slow, steady, vertical motion until failure. To collect the testing data, a device with a video camera (e.g., smartphone) was used to record the force reading from the luggage scale at failure.

A similar testing procedure was performed for the master’s cohort; however, no ring stands were used. Rather, the digital luggage scale was held manually by one team member while another team member pulled the opposite substrate of the sample. A third team member was responsible for recording the force reading from the luggage scale at the failure point.

Post-Laboratory Report and Exercise

After completing the module, all trainees were given the same rubric to guide post-laboratory data analysis and discussion. Trainees in the undergraduate and master’s cohorts completed a post-laboratory report. In the post-laboratory report, trainees introduced bioadhesives and mechanisms of adhesion, described their materials and methods for formulating and testing bioadhesives, summarized their results with appropriate statistical analysis, and discussed their findings in the context of applications of bioadhesives for tissue repair. Post-laboratory reports were graded using a rubric that assessed the quality to which trainees reported their findings; however, the results of these reports were not included in this manuscript. Since trainees in the PhD/postdoctoral cohort were enrolled in a 1-day workshop rather than a class, they were not asked to complete a post-laboratory report. Instead, PhD/postdoctoral trainees created oral presentations on the same day of the module that covered the same topics and participated in a group discussion.

Trainees in all cohorts used three replicates (N = 3) for each condition. The undergraduate cohort used their experimental data to calculate a theoretical sample size, then discussed whether their sample size was sufficient. Sample size calculations were conducted in R using the “ss.1way” function in the “pwr2” package. Of note, students were told that this type of post-hoc power analysis would not be advisable for a rigorous scientific experiment; however, instructors included this portion of the post-laboratory report to teach trainees about statistical power and how to calculate sample sizes using R.

Learning Module Evaluation

Trainees in all cohorts were given pre- and post-tests to evaluate the learning gains resulting from completing this IBL bioadhesives module. The pre/post-tests consist of five questions composed by the authors related to understanding the design variables and applications of bioadhesives for tissue repair (Appendix A). A pre/post-test length of five questions was chosen to cover all learning objectives of interest without being repetitive and placing extra burden on the trainees participating in this voluntary study. Additionally, pre/post-test assessments of a similar length have been previously used to evaluate learning gains from biomedical engineering education modules.15,34,48 The pre-test was administered to trainees prior to the pre-laboratory lecture and exercise, and the post-test was administered after trainees submitted their post-laboratory report or had their post-laboratory discussion. Trainees were not allowed to review their pre-test before taking the post-test. Only trainees who completed both tests were included in the data analysis.

Additionally, trainees were given pre- and post-surveys to assess changes in their scientific literacy as a result of completing this IBL bioadhesives module. The pre/post-survey questions included six questions based on those from the Scientific Literacy and Student Value in Inquiry-guided Lab Survey (SLIGS),2 along with a seventh question to allow for trainees to share additional comments or feedback. Each question was answered on a Likert Scale of “Confident” to “Not Confident.” Numerical values were assigned to each response (i.e., 0 = “Not Confident”, 1 = “Somewhat Not Confident”, 2 = “Somewhat Confident” and 3 = “Confident”) for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism® software Version 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The average scores for the pre/post-tests and pre/post-surveys were compared using paired t tests (p < 0.05), after confirming groups had equal variance using an F test. Statistical analysis was conducted for all cohorts individually and for the pooled set of all cohorts. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to compare the average learning gains between the three cohorts. All tests and surveys were voluntary and distributed using Microsoft Forms (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Trainees were anonymized prior to analysis.

RESULTS

Pre/Post-Test Assessment

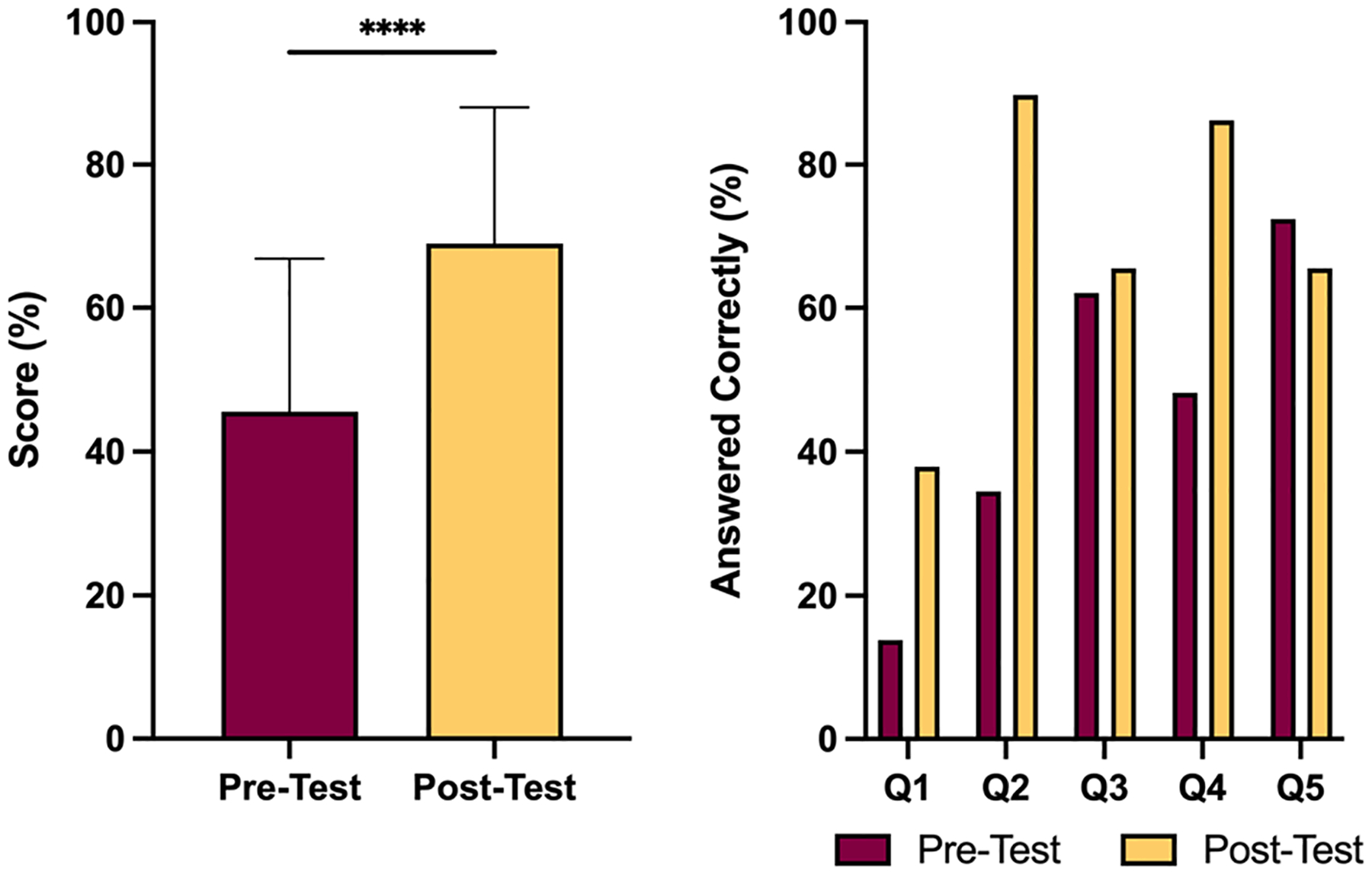

Across all three cohorts, twenty-nine trainees (N = 29) participated in the pre/post-test assessment. Questions were written to test understanding of adhesion mechanisms and biomedical applications of bioadhesives for tissue repair. The complete list of questions is found in Appendix A. The results of the assessment showed that test averages significantly increased from 45.5% on the pre-test to 69.0% on the post-test (Fig. 2). In addition to significant overall score increases, it was found that the percentage of trainees who correctly answered questions Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 was greater in the post-test than the pre-test. This was particularly striking for Q2 and Q4 because approximately double the participants answered these questions correctly in the post-test compared to the pre-test. These questions tested the understanding of the mechanisms of GTA-crosslinked gelatin adhesion. Q5 was the only question that showed a slight decrease in the percentage of trainees who answered correctly. This question was more exploratory and tested whether participants could apply their knowledge of bioadhesives to translational applications of biomaterials not explicitly taught in this module.

FIGURE 2.

Trainees showed significant learning gains via pre/post-test assessment. (a) Average trainee pre/post-test score. (b) Percentage of students who answered individual questions correctly on pre/post-test assessments. ****p<0.00001.

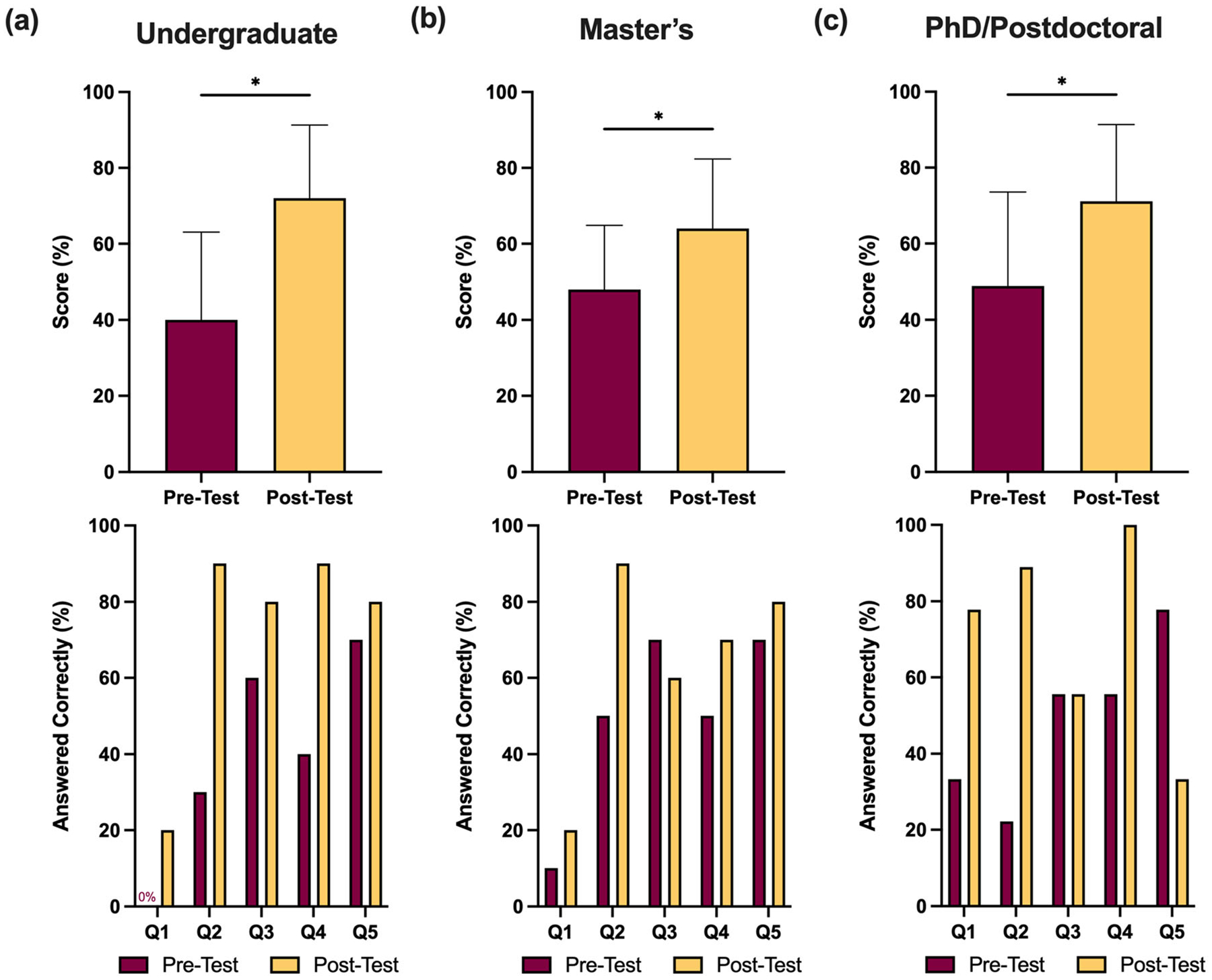

To understand the efficacy of this module at different education levels, follow-up analyses were conducted for undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral cohorts, separately. All cohorts demonstrated significant learning gains by pre/post-test assessment (Fig. 3). Undergraduates (N = 10) showed the largest learning gains, with an average increase of 34.2 points from pre- to post-test. Moreover, the percentage of undergraduates who answered each question correctly was higher in the post-test for all questions. Master’s (N = 9) and PhD/postdoctoral (N = 10) also had significant average learning gains. While not significantly lower than the undergraduate cohort, the average learning gains were 20.7 and 23.3 points, respectively. For the master’s cohort, the percentage of trainees who answered each question correctly on the post-test was greater than the pre-test for all questions, except Q3. The percentage of master’s students who answered Q3 correctly dropped slightly from 70% (7 students) in the pre-teest to 60% (6 students) in the post-test. The same held true for PhD/postdoctoral trainees, except for Q5. Approximately half the number of PhD/postdoctoral trainees answered Q5 correctly in the post-test, compared to the pre-test. As previously mentioned, Q5 was a more applied question that required trainees to apply the knowledge gained from this module to design a new experiment. On the contrary, the number of PhD/postdoc trainees who answered Q1, Q2, and Q4 was approximately double for the post-test, compared to the pre-tests. Overall, these results highlight the significant learning gains that undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral trainees can experience from completing this IBL bioadhesives module.

FIGURE 3.

Trainees in all cohorts scored higher on post-test assessment, demonstrating significant learning gains. Average trainee pre/post-test score (top) and percentage of students who answered individual questions correctly on pre/post-test assessments (bottom) for (a) Undergraduate, (b) Master’s, and (c) PhD/postdoctoral trainees. *p<0.05.

Pre/Post-Survey Assessment

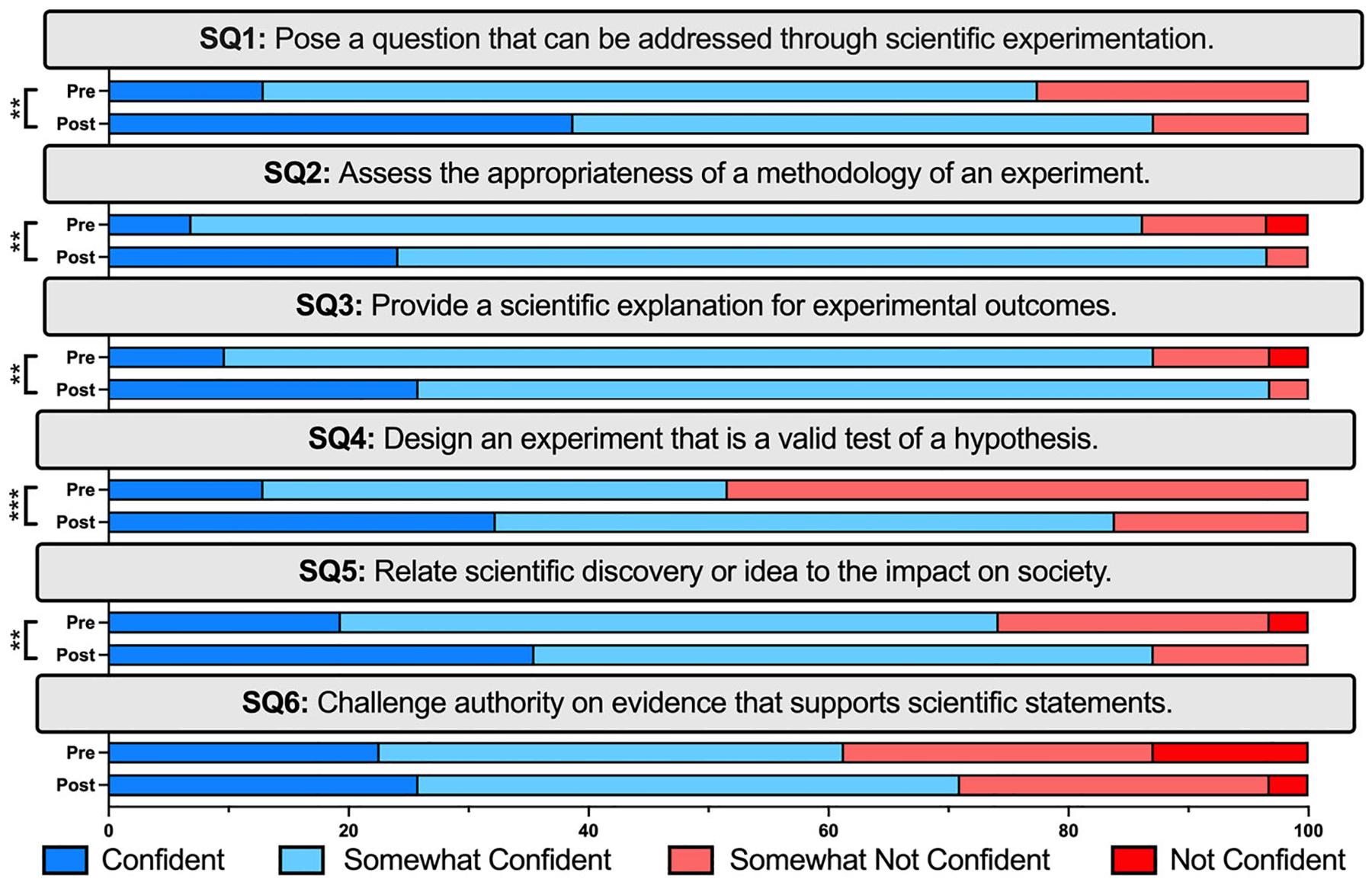

Validated questions from the Scientific Literacy and Student Value in Inquiry-guided Lab Survey (SLIGS) were used to assess improvements in scientific literacy.2 Pooled surveys of all cohorts (N = 29) were analyzed first to broadly understand how completing this IBL bioadhesives module impacts participants’ scientific literacy. Pre/post-survey assessments showed that participants felt more confident posing scientific questions (SQ1), assessing methodology (SQ2), providing scientific explanations (SQ3), designing experiments (SQ4), and relating scientific discovery to societal impact (SQ5) as a result of completing this IBL bioadhesives module (Fig. 4). While not significantly different, there was also an increase in the number of participants who felt more “Confident” or “Somewhat Confident” challenging authority on evidence that supports scientific statements (SQ6). Overall, these results demonstrate that completing this IBL bioadhesives module can improve scientific literacy for a wide range of trainees, and suggests that additional investigations would be required to have confidence to challenge authority on this topic.

FIGURE 4.

Trainees showed significant improvements in scientific literacy via pre/post-survey assessment. **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001.

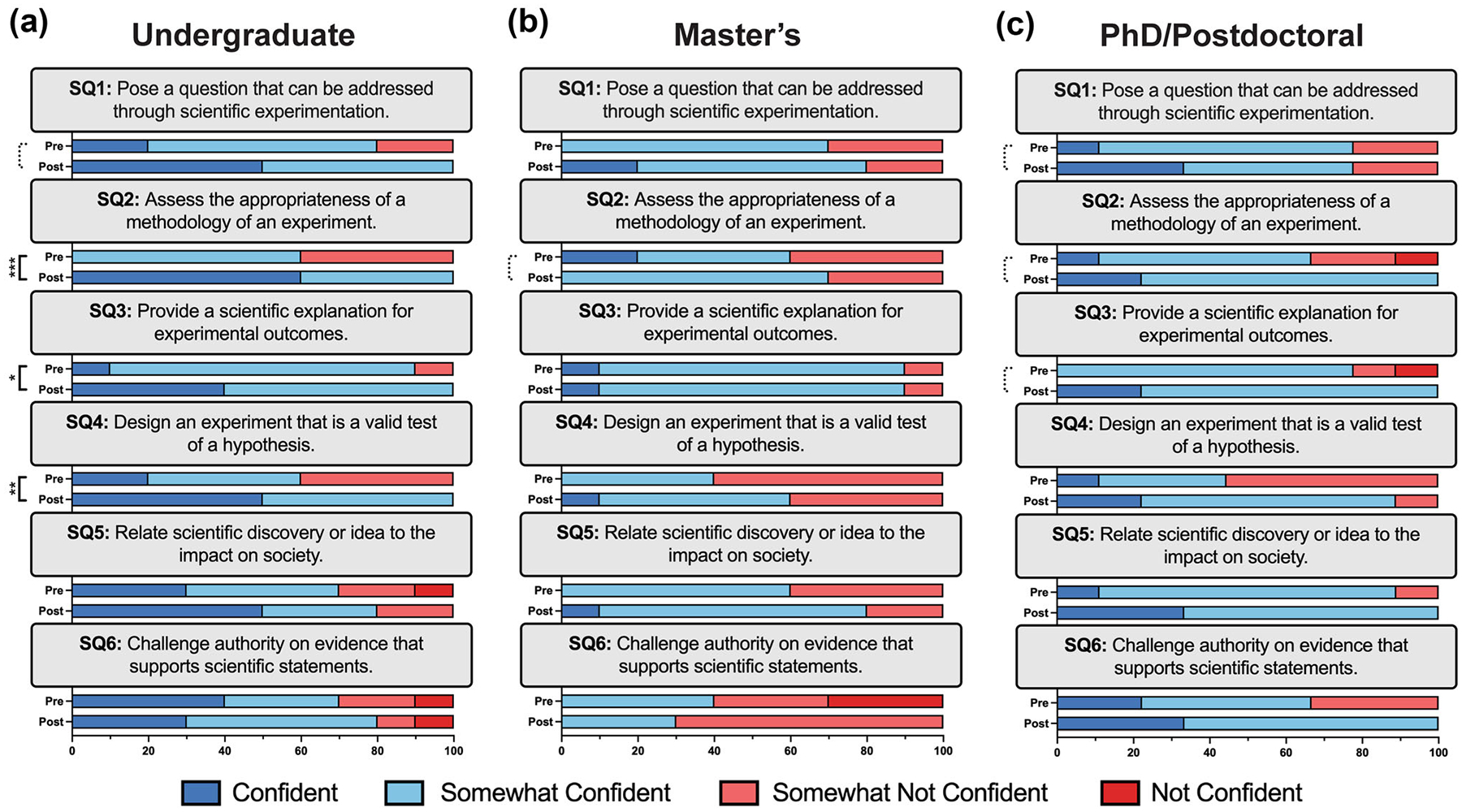

Similar to the pre/post-test assessments, follow-up analyses were conducted on the pre/post-survey assessments for each cohort separately to explore the efficacy of this module at different education levels. Undergraduates (N =10) had the greatest improvement in scientific literacy from completing this IBL bioadhesives module (Fig. 5a). Specifically, undergraduates were significantly more confident assessing methodology (SQ2), providing scientific explanations (SQ3), and designing experiments (SQ4). Undergraduates also displayed a trending, but not statistically significant, increase in their confidence posing scientific questions (SQ1). Master’s (N = 9) and PhD/postdoctoral (N = 10) cohorts displayed trending, but not statistically significant, increases in some categories of scientific literacy. For the master’s cohort, there was a trending, but not statistically significant, increase in confidence assessing methodology (SQ2) (Fig. 5b). PhD/postdoctoral trainees showed trending increases in their confidence posing scientific questions (SQ1), assessing methodology (SQ2), and providing scientific explanations (SQ3) (Fig. 5c). These cohort analyses show that this IBL bioadhesives module most effectively enhances scientific literacy for undergraduates with less education and training in open-ended experimental design.

FIGURE 5.

Undergraduate cohort showed significant improvements in scientific literacy, while master’s and PhD/postdoctoral trainees showed trending, but not statistically significant, improvements. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Dashed lines indicate trending, but not statistically significant, differences (0.05 < p < 0.10).

DISCUSSION

Bioadhesives are an important class of biomaterials with applications in wound healing, hemostasis, and tissue repair.11,46 The authors conducted a systematic literature review and found no published engineering education modules about bioadhesives. The closest relevant study used an IBL approach to teach students about principles of adhesives, but the adhesives used were not biologically relevant, trainees were not required to discuss their results in the context of clinical bioadhesives, the module was not deployed on master’s, PhD, and postdoctoral trainees, and improvements in learning and scientific literacy were not quantitatively assessed.50 Developing engaging experiments to teach principles of bioadhesives to a range of trainees with little prior knowledge is important because engineering students learn more effectively from these hands-on experiences.7,47 Herein, this study designed, implemented, and evaluated a module that effectively taught principles of bioadhesives to undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral trainees.

This IBL bioadhesives module was designed to teach trainees about how bioadhesives are used for tissue repair, how to engineer bioadhesives for different biomedical applications, and how to assess the efficacy of bioadhesives. Mechanical interlocking and chemical interactions at the tissue-bioadhesive interface are two major mechanisms of bioadhesion11; thus, this module incorporated one bioadhesive for each mechanism. Cyanoacrylate and GTA-crosslinked gelatin were chosen as the mechanical and chemical bioadhesives, respectively, because the components are biocompatible and commonly used for tissue repair applica tions.1,8,16 Additionally, two substrates were used: (1) chamois, which has a protein-rich surface and (2) 3D-printed PLA, which is bioinert. The inclusion of two substrates prompted trainees to consider both the bioadhesive and the substrate when engineering bioadhesives for tissue repair. Trainees tested their bioadhesives using a lap-shear configuration that mimicked ASTM 2255-005, an internationally recognized protocol for testing the strength of tissue adhesives.45 Introducing trainees to such standardized testing methods is important for combating the crisis of rigor and reproducibility in science.32

Evaluations demonstrated that trainees at all education levels experienced significant learning gains from completing this IBL bioadhesives module. Learning gains were the greatest for the undergraduate cohort (34.2 points), which was expected since they had the least exposure to theoretical concepts of biomaterials and very limited applied knowledge. Learning gains were slightly less, but not statistically lower, for the master’s cohort (20.7 points) because these trainees had more previous theoretical and applied knowledge of biomaterials; thus, they were more likely to score higher on the pre-test. Trainees in the PhD/postdoctoral cohort had materials science and chemical technology as their field of study at the Riga Technical University, with limited exposure to bioadhesive hydrogels. Therefore, their learning gains (23.3 points) were similar to the master’s cohort because they had limited previous theoretical and applied knowledge of biomaterials even though they were in a more advanced stage of their education. Overall, these findings are consistent with other studies that found learning gains of approximately 50 points for freshman engineering students,15,49 but lower learning gains of approximately 15 points for senior engineering students.48

A majority of trainees correctly answered almost all questions in the post-test. The highest percentage of trainees answered Q2 (89.7%) and Q4 (86.2%) correctly (Fig. 2). Q2 and Q4 tested the concept that GTA chemically crosslinks surfaces and will effectively crosslink protein-rich surfaces, like chamois. Less trainees answered Q1 (37.9%) correctly in the post-test, which tested the mechanism of cyanoacrylate adhesion. This finding is interesting because trainees varied the concentrations of gelatin and GTA in their experiments, but only used one concentration of cyanoacrylate. Thus, our findings suggest that allowing manipulation of the GTA-crosslinked gelatin material enhanced learning gains about the mechanisms of adhesion for this bioadhesive. Cyanoacrylate concentration was not included as a variable in this module because the module was intended to last approximately 3 h. Future iterations of this educational module could include the concentration of cyanoacrylate as an independent variable to promote additional learning gains about mechanical adhesive mechanisms, given instructors have more class time to run the module. Additionally, the technical breadth of this module could be extended by using more advanced testing equipment, like a load cell, for more precise calculation of force and adhesive strength. Such equipment was not utilized for this IBL bioadhesives module because the module was designed to use less expensive equipment for easier deployment throughout the world.

Follow-up analyses found that the percentage of trainees in each cohort who answered each question correctly on the post-test was greater than or equal to the pre-test for almost all questions. The only exceptions were Q3 for the master’s cohort and Q5 for the PhD/postdoctoral cohort. Given the sample size of the master’s cohort (N = 9), the approximately 10% reduction means that only one trainee answered this question correctly on the pre-test, but not the post-test. Since it was only one student, this likely does not represent a meaningful decrease in comprehension for this question in the master’s cohort. On the contrary, there was an approximately 40% reduction in the number of PhD/postdoctoral trainees who answered Q5 correctly from the pre-test to the post-test, which is likely a meaningful reduction. Q5 was an applied question, which tested the ability of trainees to design a bioadhesive in the biological context of skin repair. PhD/postdoctoral trainees likely performed worse on this question since they did not have a biomedical background and they did not complete a written post-laboratory report. Instead of a written report, PhD/postdoctoral trainees created oral presentations on the same day of the module and participated in a group discussion, which included applications of bioadhesives. Undergraduate and master’s students had outside class time to write a post-laboratory report, which specifically asked trainees to discuss their findings in the context of applied bioadhesives for tissue repair. Since undergraduate and master’s trainees completed this post-laboratory report and experienced slight learning gains from Q5, findings highlight the importance of outside class time and writing to teach more applied concepts of bioadhesives.

Pooled pre/post-survey assessments showed that trainees generally experienced significant improvements in scientific literacy from completing this experiment. Pre/post-surveys were created using validated Scientific Literacy and Student Value in Inquiry-guided Lab Survey (SLIGS) questions to assess scientific literacy.2 These validated questions were employed to avoid self-reporting bias, which has been a previously reported challenge of self-reporting measures.21 Follow-up analysis of the SLIGS validated surveys demonstrated that scientific literacy improvements were only significant for the undergraduate cohort. Such findings were expected since the undergraduate cohort had the least experience leading scientific investigations and would likely benefit the most from an IBL experiment.

The only scientific literacy category that did not show a significant increase in pooled pre/post-survey assessments was “challenging scientific authority”. Activities such as concept maps, negotiation circles, reflection time, and writing letters to a younger audience are all documented strategies to enhance scientific argument skills9; thus, future iterations of this experiment could incorporate these deeper analyses, more refined methodologies, and training with post-lab discussions that enhance trainee ability to challenge scientific authority. That being said, scientific literacy is a skill that trainees continually develop throughout their scientific careers and one module cannot be the panacea for improved scientific literacy. To further develop these skills, trainees must complete numerous modules and other independent research projects, over the course of several years of training. This is especially true for “challenging scientific authority”, which likely requires a greater breadth of experiences than could be gained from completing a single IBL module. The IBL module presented is one example of an experiment with appropriate technical rigor to improve scientific literacy.

DIVERSITY, EQUITY, AND INCLUSION

Innovative outreach activities are important for increasing the number of trainees studying STEM.23,38 This is especially important for trainees who are underrepresented in STEM based on race, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or geographic location.27,33,41,43 To help address these gaps, the authors previously partnered with the Young Eisner Scholars, a program designed to empower middle and high school students from underserved communities, to adapt an undergraduate-level, at-home inquiry-based learning module for middle school outreach.34,35 The authors hypothesize that this IBL bioadhesives module can be similarly adapted to an outreach activity for middle and high school students. For an in-person middle or high school student outreach activity, instructors should provide supervision when using the GTA crosslinker and use the experience as an opportunity to teach about chemical safety. Additionally, instructors may exclude the PLA substrate if they do not have access to a 3D printer or if they wish to simplify the outreach activity. For an at-home experiment, students could compare the adhesion of common household adhesives that have the same mechanisms of adhesion (e.g., cyanoacrylate and polyvinyl acetate). These simplified iterations of this IBL bioadhesives module would still use the ASTM 2255–05 lap-shear testing method to teach about testing standards. Simplifying this IBL bioadhesives module with reduced variables of interest could still incorporate rigorous statistical analysis and discussions of designing bioadhesives for real-world applications; thus, adhering to Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) for high school students.22 Using NGSS for middle school students, this activity could be further simplified to use less groups, focus on basic statistical techniques and emphasize communicating information in evidence-based arguments.31

CONCLUSION

This study designed, implemented, and evaluated an inquiry-based learning (IBL) module to teach principles of bioadhesives to undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral trainees. This IBL bioadhesives module was designed as a 3 h activity to be completed within 1-day for easy deployment. This hands-on IBL bioadhesive module taught trainees about how bioadhesives are used for tissue repair, how to engineer bioadhesives for different biomedical applications, and how to assess the efficacy of bioadhesives through internationally recognized testing standards. Using pre/post-test assessments, it was found that undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral trainees all had significant learning gains and improvements in scientific literacy as a result of completing this IBL bioadhesives module. Improvements in learning and scientific literacy were most significant for the undergraduate cohort, which was likely due to this cohort having the least amount of experience with bioadhesives and scientific inquiry. Instructors can use this module to introduce and enhance undergraduate, master’s, and PhD/postdoctoral trainees’ knowledge of bioadhesives. Furthermore, the authors hypothesize that this IBL bioadhesives module could be modified with inexpensive deployment for middle school and high school outreach in-person and at-home, making it useful for addressing the systemic issues surrounding diversity, equity, and inclusion in STEM.

FUNDING

Part of this work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) grant F31AR077385 [CJP]. Materials purchased for The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art were supported by a grant from a foundation that wishes to remain anonymous [JRW]. Materials were purchased for the RISEus2 project “Rising competitiveness of early stage researchers and research management in Latvia” by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement 952347 [RISEus2]. Materials were purchased for ETH Zürich through the AO Foundation [AJV].

APPENDIX A: PRE/POST-TEST QUESTIONS

- What is the most important factor for determining if cyanoacrylate will adhere two surfaces together?

- Chemical bonding

- Mechanical interlocking

- Both

- Which material will have the greatest adhesive strength between two chamois (leather) cloths?

- Gelatin

- Glutaraldehyde

- Gelatin and glutaraldehyde

- Neither

- Increasing the concentration of glutaraldehyde in your gelatin-glutaraldehyde bioadhesive will:

- Increase adhesive strength by increasing the number of non-crosslinked units

- Increase adhesive strength by decreasing the number of non-crosslinked units

- Decrease adhesive strength by increasing the number of non-crosslinked units

- Decrease adhesive strength by decreasing the number of non-crosslinked units

- From the list below, what type of materials would be best to adhere together using a gelatin-glutaraldehyde bioadhesive?

- Inert materials with smooth surfaces

- Inert materials with rough surfaces

- Materials with protein-rich surfaces

- Materials with electrostatic charges

- You are designing a bioadhesive polymer for sealing surgical wounds on the skin. The best design plan would be:

- Measure ultimate tensile strength of the bioadhesive

- Chose a maximum value for the ultimate tensile strength of your bioadhesive and manipulate its composition until you achieve that value

- Manipulate the bioadhesive composition until the adhesive strength between skin and the bioadhesive is similar to the ultimate tensile strength of skin

- Manipulate the bioadhesive composition until the ultimate tensile strength of your bioadhesive is similar to that of skin

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

All questions were approved by The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Ethics Commission of ETH Zürich, and the Baltic Biomaterials Centre of Excellence.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Trainees provided informed consent to study participation, data collection, and dissemination prior to program engagement, and were informed of the capacity to revoke consent at any time.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Trainees provided informed consent to study participation, data collection, and dissemination prior to program engagement, and were informed of the capacity to revoke consent at any time.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All test and survey questions can be found in Appendix A. Additional data is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmady A, Abu Samah NH. A review: Gelatine as a bioadhesive material for medical and pharmaceutical applications. Int J Pharm. 2021;608:121037. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ankeny C, Stabenfeldt S. Cost-effective, inquiry-guided introductory biomaterials laboratory for undergraduates. In: 2015 ASEE annual conference and exposition proceedings, ASEE conferences; 2015, p. 26.412.1–26.412.16. 10.18260/p.23751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrow LH. A brief history of inquiry: from dewey to standards. J Sci Teacher Educ. 2006;17:265–78. 10.1007/s10972-006-9008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biggs J. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High Educ. 1996;32:347–64. 10.1007/BF00138871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bioengineers and Biomedical Engineers: Occupational Outlook Handbook: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics n.d. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/architecture-and-engineering/biomedical-engineers.htm#:~:text=Employment%20of%20bioengineers%20and%20biomedical,on%20average%2C%20over%20the%20decade. Accessed 11 Mar 2022.

- 6.Biomaterials n.d. https://www.nibib.nih.gov/science-education/science-topics/biomaterials. Accessed 11 Mar 2022.

- 7.Black J, Shalaby SW, Laberge M. Biomaterials education: an academic viewpoint. J Appl Biomater. 1992;3:231–6. 10.1002/jab.770030311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao H-H, Torchiana DF. BioGlue: albumin/glutaraldehyde sealant in cardiac surgery. J Card Surg. 2003;18:500–3. 10.1046/j.0886-0440.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y-C. Constructing and critiquing arguments: the use of talk and writing to. Sci Child. 2013;50:40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dewey J Science as subject-matter and as method. Sci Educ. 1995;4:391–8. 10.1007/BF00487760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiStefano TJ, Shmukler JO, Danias G, Iatridis JC. The Functional role of interface tissue engineering in annulus fibrosus repair: bridging mechanisms of hydrogel integration with regenerative outcomes. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2020;6:6556–86. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiStefano TJ, Vaso K, Panebianco CJ, et al. Hydrogel-embedded Poly(Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid) microspheres for the delivery of hMSC-derived exosomes to promote bioactive annulus fibrosus repair. CARTILAGE. 2022;13(3). 10.1177/19476035221113959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorier J, Maab K. The PRIMAS Project: Promoting inquiry-based learning in mathematics and science education across Europe. Seventh Framework Programme; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelmann S. Direct instruction (the Instructional Design Library; V. 22) Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Educational Technology Pubns; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell S, Cavanagh E. An introduction to life cycle assessment with hands-on experiments for biodiesel production and use. Educ Chem Eng. 2014;9:e67–76. 10.1016/j.ece.2014.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García Cerdá D, Ballester AM, Aliena-Valero A, Carabén-Redaño A, Lloris JM. Use of cyanoacrylate adhesives in general surgery. Surg Today. 2015;45:939–56. 10.1007/s00595-014-1056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson HL, Chase C. Longitudinal impact of an inquiry-based science program on middle school students’ attitudes toward science. Sci Educ. 2002;86:693–705. 10.1002/sce.10039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grand Review Research. Biomaterials Market Size, Share, Analysis | Industry Report, 2027. Grand Review Research; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314–21. 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houben S, Quintens G, Pitet LM. Tough hybrid hydrogels adapted to the undergraduate laboratory. J Chem Educ. 2020;97:2006–13. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard GS. Response-shift bias. Eval Rev. 1980;4:93–106. 10.1177/0193841X8000400105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HS-ETS1 Engineering Design | Next Generation Science Standards n.d. https://www.nextgenscience.org/dci-arrangement/hs-ets1-engineering-design. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- 23.Jeffers AT, Safferman AG, Safferman SI. Understanding K–12 engineering outreach programs. J Prof Issues Eng Educ Pract. 2004;130:95–108. 10.1061/(ASCE)1052-3928(2004)130:2(95). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karp JM, Friis EA, Dee KC, Winet H. Opinions and trends in biomaterials education: report of a 2003 Society for Biomaterials survey. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;70:1–9. 10.1002/jbm.a.30087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalaf BK, Zin ZBM. Traditional and inquiry-based learning pedagogy: a systematic critical review. Int J Instr. 2018;11:545–64. 10.12973/iji.2018.11434a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Yu X, Martinez EE, Zhu J, Wang T, Shi S, et al. Emerging biopolymer-based bioadhesives. Macromol Biosci. 2022;22:e2100340. 10.1002/mabi.202100340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linley JL, Renn KA, Woodford MR. Examining the ecological systems of lgbtq stem majors. J Women Minor Sci Eng. 2018;24:1–16. 10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.2017018836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luisa M, Renau R. A review of the traditional and current language teaching methods. Int J Innov Res Educ Sci. 2016;3:82–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehdizadeh M, Yang J. Design strategies and applications of tissue bioadhesives. Macromol Biosci. 2013;13:271–88. 10.1002/mabi.201200332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mikos AG, Herring SW, Ochareon P, Elisseeff J, Lu HH, Kandel R, et al. Engineering complex tissues. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3307–39. 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MS-ETS1 Engineering Design | Next Generation Science Standards n.d. https://www.nextgenscience.org/dci-arrangement/ms-ets1-engineering-design. Accessed 8 April 2021.

- 32.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Policy and Global Affairs; Committee on Science, Engineering, Medicine, and Public Policy; Board on Research Data and Information; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; Committee on Applied and Theoretical Statistics; Board on Mathematical Sciences and Analytics; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Nuclear and Radiation Studies Board; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Committee on National Statistics; Boa. Reproducibility and replicability in science. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2019. 10.17226/25303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oyana TJ, Garcia SJ, Haegele JA, Hawthorne TL, Morgan J, Young NJ. Nurturing diversity in STEM fields through geography: the past, the present, and the future. JSTEM 2015;16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panebianco CJ, Iatridis JC, Weiser JR. Development of an at-home metal corrosion laboratory experiment for STEM outreach in biomaterials during the COVID-19 pandemic. In: 2021 ASEE annual conference and exposition proceedings, ASEE conferences; 2021. https://peer.asee.org/36966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panebianco CJ, Iatridis JC, Weiser JR. Teaching principles of biomaterials to undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic with at-home inquiry-based learning laboratory experiments. Consortium for Energy Efficiency (CEE), (2022) vol. 56(1). 10.18260/2-1-370.660-125552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panebianco CJ, Meyers JH, Gansau J, Hom WW, Iatridis JC. Balancing biological and biomechanical performance in intervertebral disc repair: a systematic review of injectable cell delivery biomaterials. ECM. 2020;40:239–58. 10.22203/eCM.v040a15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panebianco CJ, Rao S, Hom WW, Meyers JH, Lim TY, Laudier DM, et al. Genipin-crosslinked fibrin seeded with oxidized alginate microbeads as a novel composite biomaterial strategy for intervertebral disc cell therapy. Biomaterials. 2022;287:121641. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poole SJ, deGrazia JL, Sullivan JF. Assessing K-12 pre-engineering outreach programs. In: FIE’99 frontiers in education. 29th annual frontiers in education conference. Designing the future of science and engineering education. Conference proceedings (IEEE Cat. No.99CH37011, Stripes Publishing L.L.C; 1999, p. 11B5/15–11B5/20. 10.1109/FIE.1999.839234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rashty D. Traditional Learning vs. eLearning 1999. http://www.click4it.org/images/f/f5/Traditional_Learning_vs_eLearning.pdf. Accessed 25 Dec 2020.

- 40.Ratner BD, editor. Biomaterials Science. 3rd ed. Elsevier;2013. 10.1016/C2009-0-02433-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riegle-Crumb C, King B, Irizarry Y. Does STEM stand out? examining racial/ethnic gaps in persistence across postsecondary fields. Educ Res. 2019;48:133–44. 10.3102/0013189X19831006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saterbak A Laboratory courses focused on tissue engineering applications. In: 2002 annual conference proceedings, ASEE conferences; 2002, p. 7.786.1–7.786.13. 10.18260/1-2-10325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scull S, Cuthill M. Engaged outreach: using community engagement to facilitate access to higher education for people from low socio-economic backgrounds. High Educ Res Dev. 2010;29:59–74. 10.1080/07294360903421368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spencer JA, Jordan RK. Learner centred approaches in medical education. BMJ. 1999;318:1280–3. 10.1136/bmj.318.7193.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Standard Test Method for Strength Properties of Tissue Adhesives in Lap-Shear by Tension Loading. ASTM International; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarafder S, Park GY, Felix J, Lee CH. Bioadhesives for musculoskeletal tissue regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2020;117:77–92. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veazie D Laboratory experiment in engineering materials for upper-level undergraduate and graduate students. In: 2013 ASEE annual conference & exposition proceedings, ASEE conferences; 2013, p. 23.845.1–23.845.13. 10.18260/1-2-19859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vernengo J, Dahm KD. Two challenge-based laboratories for introducing undergraduate students to biomaterials. Educ Chem Eng. 2012;7:e14–21. 10.1016/j.ece.2011.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vernengo J, Purdy C, Farrell S. Undergraduate laboratory experiments teaching fundamental concepts of rheology in context of sickle cell anemia. Chem Eng Educ. 2014;48:149. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Fang A, Johnson M. Enhancing and assessing life long learning skills through capstone projects. In: 2008 annual conference & exposition proceedings, ASEE conferences; 2008, p. 13.536.1–13.536.12. 10.18260/1-2-3244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan Z, Yin H, Nerlich M, Pfeifer CG, Docheva D. Boosting tendon repair: interplay of cells, growth factors and scaffold-free and gel-based carriers. J Exp Ortop. 2018;5:1. 10.1186/s40634-017-0117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu W, Chuah YJ, Wang D-A. Bioadhesives for internal medical applications: a review. Acta Biomater. 2018;74:1–16. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All test and survey questions can be found in Appendix A. Additional data is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.