Abstract

Objectives:

To examine how outpatient mental health (MH) follow-up after a pediatric MH emergency department (ED) discharge varies by patient characteristics, and to evaluate the association between timely follow-up and return encounters.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective study of 28,551 children aged 6–17 years with MH ED discharges from January 2018 to June 2019, using the IBM Watson MarketScan Medicaid database. Odds of non-emergent outpatient follow-up, adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, were estimated using logistic regression. Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the association between timely follow-up and risk of return MH acute care encounters (ED visits and hospitalizations).

Results:

Following MH ED discharge, 31.2% and 55.8% of children had an outpatient MH visit within 7 and 30 days, respectively. The return rate was 26.5% within 6 months. Compared to children with no past year outpatient MH visits, those with ≥14 past year MH visits had 9.53 odds of accessing follow-up care within 30 days (95% CI 8.75, 10.38). Timely follow-up within 30 days was associated with a 26% decreased risk of return within 5 days of the index ED discharge (hazard ratio 0.74, 95% CI 0.63, 0.91), followed by an increased risk of return thereafter.

Conclusions:

Connection to outpatient care within 7 and 30 days of a MH ED discharge remains poor, and children without prior MH outpatient care are at highest risk for poor access to care. Interventions to link to outpatient MH care should prioritize follow-up within 5 days of an MH ED discharge.

Article Summary

Following a pediatric mental health emergency department discharge, we report rates of 7- and 30-day outpatient follow-up and return acute encounters, using Medicaid claims data.

Introduction

Pediatric emergency department (ED) visits for mental health (MH) conditions are rising in the United States, with the majority culminating in discharge.1–3 Timely outpatient follow-up after a MH ED discharge may facilitate continuity and ongoing engagement in MH care.4,5 Nevertheless, fewer than two-thirds of children receive outpatient MH follow-up within 30 days of a MH ED discharge.6,7 Follow-up within 7 and 30 days of a MH ED visit for children ages 6 to 17 was added to the National Child Core Set of quality measures in 2022, and state Medicaid agencies will be mandated to report annual adherence rates starting in 2024.6,8,9

Despite increased attention to follow-up as a quality measure, there is limited evidence linking timely follow-up after a MH ED discharge with meaningful outcomes, such as decreased return MH ED visits or hospitalizations.10 Many previous studies have focused on follow-up after MH hospitalizations as opposed to ED discharges.7,11–13 While some of these studies have demonstrated a protective effect of outpatient follow-up care on subsequent MH ED visits and hospitalizations, several studies paradoxically suggest higher return rates among children who receive timely outpatient follow-up.7,11–15 In contrast to children discharged from a MH hospitalization, children discharged from the ED are likely to have lower clinical severity and greater family supports, thus these children may have different follow-up rates and risk of return.

Follow-up rates may also differ by child sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, but this variation has primarily been explored following hospitalization rather than after ED discharges. Black and Hispanic children are less likely to receive timely outpatient follow-up after a MH hospitalization compared to White children, consistent with known inequities in receipt of outpatient MH care.7,16,17 Studies that did examine variation in follow-up after ED discharges were limited to ED visits for a specific MH symptom, such as suicidal ideation or anxiety, precluding examination of differences by MH diagnosis types.7,14,15 An understanding of variation in follow-up rates after ED discharge across socioeconomic and clinical characteristics is needed to improve equitable access to MH care and reduce subsequent acute MH care use.

Using a large sample of Medicaid-enrolled children, our objectives were (1) to examine rates of outpatient follow-up within 7 and 30 days after a MH ED discharge and variation in rates by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and (2) to determine if receipt of timely outpatient follow-up care is associated with reduced risk of a return MH ED visit or hospitalization. We hypothesized that outpatient follow-up visits within 7 and 30 days of a MH ED discharge would be associated with decreased risk of return MH acute care encounters, after adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 28,551 children aged 6–17 years enrolled in Medicaid with at least one MH ED discharge from January 2018 to June 2019. We used the IBM Watson MarketScan Medicaid Database, which contains patient-level demographic, enrollment, and health care claims data for Medicaid enrollees in 11 geographically dispersed and de-identified states.18 We excluded children with no MH and substance use coverage (4.6%), children without continuous Medicaid enrollment for six months following index ED visit (7.4%), and children with only MH ED visits resulting in admission, defined as a hospitalization claim on the same or next calendar day as the ED visit (4.5%) (Supplemental Figure).7,19

The child’s first MH ED discharge from January 2018 to June 2019 was classified as the index ED discharge. The date of the index ED discharge served as the anchor point to identify past year MH service use, follow-up outpatient MH care within 7 and 30 days of the index ED discharge, and return MH acute care encounters (ED visits or hospitalizations) during the six months after the index ED discharge. We presumed that additional ED claims within one calendar day of the index ED visit mainly represented ED-to-ED transfers, thus we analyzed these ED claims together with index ED visit claims rather than as return visits.

Study Variable Construction

We defined MH encounters following specifications in the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) quality measure definition for MH follow-up after ED visits.6 Primary MH diagnoses were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) HEDIS diagnosis code sets for “mental health illness” or “intentional self-harm.” The MH encounter location (outpatient visit, ED visit, or hospitalization) was determined by procedure and place of service (POS) codes. We identified MH ED visits using POS code 23 and CPT E/M codes 98281–98285, and MH hospitalizations based on POS codes for inpatient hospitals and inpatient psychiatric facilities (codes 21 and 51, respectively). We defined outpatient MH visits based on POS codes for outpatient settings (e.g., school, home, office, health clinic) or outpatient visit procedure codes (e.g., CPT 99211 “Office or other outpatient visit for E/M of an established patient….”), which included care provided by MH specialists and non-specialists.

We used a systematic method to assign each ED discharge, which may have multiple claims and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes, to a single MH diagnosis group. We first considered ED discharges with any claims matching the HEDIS “intentional self-harm” code set as their own MH diagnosis group. For the remaining ED discharges, we used the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Disorders Classification System (CAMHD-CS) to assign a MH diagnosis group.20,21 If the ICD-10-CM codes for an ED discharge corresponded to multiple CAMHD-CS groups, we assigned the ED discharge to the most prevalent matching MH diagnosis group in the overall sample. We then removed ED discharges with assigned MH diagnosis groups and repeated the process until <20% of all ED discharges remained, which were then categorized as “other.” This process resulted in assignment of each ED discharge to one of 5 MH diagnosis groups: intentional self-harm; depressive disorders; disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders; trauma and stressor-related disorders; and other.

The sociodemographic variables included were age group (6–11 or 12–17 years), sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, other, missing), and insurance type (fee-for-service or managed care). We assessed race and ethnicity using a health equity framework, considering both as social constructs rather than biologic determinants.22 As markers of the complexity of the index ED discharge, we included the number of distinct CAMHD-CS MH diagnosis groups identified from ICD-10-CM codes during the index ED discharge, and the number of calendar days in the ED during the index ED discharge encounter.7,11,20,21 To define non-MH comorbid conditions, we used non-MH body systems from the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA) to group patients into 3 categories using ICD-10-CM codes: no chronic conditions, non-complex chronic conditions, or complex chronic conditions.11,23,24 As markers of prior MH service use, we included the number of MH outpatient visits, MH ED visits, and MH hospitalizations in the year preceding the index ED visit.

Statistical Analysis

We described outpatient follow-up rates after MH ED discharges by sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and used adjusted multivariable logistic regression to determine characteristics associated with outpatient follow-up within 7 or 30 days. We used Chi-squared tests to determine socioeconomic and clinical characteristics associated with having a return MH acute care encounter. To assess for engagement in outpatient MH care, we determined the number of follow-up visits between 8 days and 6 months for children who followed up within 7 days, and the number of follow-up visits between 31 days and 6 months for children who followed up within 30 days.

The association of having a follow-up visit within 7 and 30 days and risk of return MH acute care encounters was assessed using Cox proportional hazards multivariable models, adjusted for socioeconomic and clinical characteristics. Days between the index ED discharge and first return acute care encounter contributed to the Cox models, at which point contributions to the model stopped and further outpatient follow-up visits or acute care encounters were not considered in the analysis. For example, if a child had an index ED discharge on day 0, a return ED visit on day 4, and a follow-up outpatient visit on day 6, the child would be counted in the model as not having had an outpatient follow-up visit from days 0 to 4, their contributions to the Cox model would stop at day 4, and their follow-up outpatient visit on day 6 would not be included in the analysis.

In our initial models, the proportional hazard assumption failed, as we found that the hazard ratio (representing the likelihood of return among children with vs. without outpatient follow-up) was not constant over time. To overcome this, we examined hazard ratios by day and empirically stratified the study time period into two groups, such that each would have constant hazard ratios. We identified these groups as ≤5 days post-index ED discharge and >5 days post index ED discharge, and we stratified each analysis into two models based on these time periods so as to fulfill the proportional hazard assumption. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina). This study was deemed exempt by the Lurie Children’s Hospital institutional review board.

Results

Follow-up Visits within 7 and 30 Days

Of 28,551 children aged 6 to 17 years old with a MH ED discharge, three-fourths were aged 12–17 years (75.5%), 51.6% female, 57.0% Non-Hispanic White, and 31.7% non-Hispanic Black) (Table 1). The most common MH diagnoses were depressive disorders (39.1%), disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders (25.0%), and trauma and stressor-related disorders (14.2%). After the index ED discharge, 31.2% of children had follow-up within 7 days and 55.8% had follow-up within 30 days. Of patients who followed up within 7 days, a median of 8 additional outpatient visits occurred (interquartile range [IQR] 3, 16) between 8 days and 6 months. Of patients who followed up within 30 days, a median of 6 additional outpatient visits occurred (IQR 2, 12) between 31 days and 6 months.

Table 1.

Outpatient Follow-Up within 7 and 30 Days of Mental Health ED Discharges by Medicaid-Enrolled Children, by Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Children with Mental Health ED Discharges, N, %a | Outpatient Follow-up within 7 days, %b | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Outpatient Follow-up within 30 days, %b | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 28,551 | 31.2 | 55.8 | ||

| Age | |||||

| 6–11 | 6937 (24.3) | 33.3 | 1.17 (1.1, 1.25) | 59.3 | 1.26 (1.18, 1.35) |

| 12–17 | 21614 (75.7) | 30.5 | Ref | 54.7 | Ref |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 14725 (51.6) | 31.9 | Ref | 56.4 | Ref |

| Male | 13826 (48.4) | 30.4 | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98) | 55.2 | 0.91 (0.86, 0.96) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 16275 (57.0) | 33.3 | Ref | 59.5 | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9056 (31.7) | 27.3 | 0.89 (0.84, 0.94) | 49.2 | 0.78 (0.74, 0.83) |

| Hispanic | 1417 (5.0) | 30.9 | 1.19 (1.05, 1.35) | 56.0 | 1.15 (1.02, 1.31) |

| Other | 724 (2.5) | 30.9 | 0.94 (0.8, 1.12) | 53.7 | 0.84 (0.71, 0.99) |

| Missing | 1079 (3.8) | 31.5 | 0.98 (0.85, 1.13) | 57.5 | 0.90 (0.78, 1.03) |

| Insurance Plan Type | |||||

| Capitated | 18078 (63.3) | 33.4 | Ref | 57.2 | Ref |

| Fee-for-service | 10473 (36.7) | 27.3 | 0.72 (0.68, 0.77) | 53.4 | 0.83 (0.79, 0.88) |

| Mental Health Diagnosis, Index ED Visit | |||||

| Depressive Disorders | 11155 (39.1) | 34.2 | Ref | 59.5 | Ref |

| Disruptive, Impulse Control and Conduct Disorders | 7126 (25.0) | 28.4 | 0.67 (0.62, 0.72) | 52.4 | 0.61 (0.57, 0.65) |

| Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders | 4058 (14.2) | 30.5 | 0.89 (0.82, 0.97) | 52.0 | 0.78 (0.72, 0.84) |

| Intentional Self-Harm | 2351 (8.2) | 29.6 | 0.85 (0.76, 0.94) | 55.0 | 0.89 (0.80, 0.98) |

| Other | 3861 (13.5) | 29.1 | 0.66 (0.61, 0.72) | 56.2 | 0.64 (0.59, 0.70) |

| Number of Distinct Mental Health Diagnosis Groups, Index ED Visit | |||||

| 1 | 7576 (26.5) | 26.5 | Ref | 47.9 | Ref |

| 2 | 9245 (32.4) | 30.4 | 1.12 (1.04, 1.2) | 54.4 | 1.18 (1.10, 1.26) |

| 3 | 6404 (22.4) | 33.4 | 1.15 (1.06, 1.24) | 60.2 | 1.31 (1.21, 1.41) |

| 4+ | 5326 (18.7) | 36.3 | 1.16 (1.07, 1.26) | 64.5 | 1.33 (1.22, 1.44) |

| Calendar Days in ED during Index Visit | |||||

| 1 day | 22766 (79.7) | 30.3 | Ref | 54.7 | Ref |

| 2 days | 3886 (13.6) | 34.0 | 1.20 (1.11, 1.30) | 59.1 | 1.15 (1.07, 1.25) |

| 3+ days | 1899 (6.7) | 35.2 | 1.24 (1.11, 1.38) | 62.2 | 1.22 (1.10, 1.36) |

| Non-Mental Health Comorbid Conditionc | |||||

| Non-Chronic | 15749 (55.2) | 29.2 | Ref | 53.0 | Ref |

| Non-Complex Chronic | 8256 (28.9) | 33.1 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.14) | 58.4 | 1.08 (1.01, 1.14) |

| Complex Chronic | 4546 (15.9) | 34.3 | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) | 60.9 | 1.05 (0.98, 1.13) |

| Prior Year Mental Health Outpatient Visits | |||||

| 0 | 9118 (31.9) | 17.4 | Ref | 33.5 | Ref |

| 1 | 2341 (8.2) | 24.4 | 1.55 (1.39, 1.73) | 46.4 | 1.71 (1.56, 1.88) |

| 2–6 | 6441 (22.6) | 30.3 | 2.15 (1.99, 2.33) | 59.1 | 2.97 (2.77, 3.18) |

| 7–13 | 4083 (14.3) | 41.1 | 3.50 (3.21, 3.82) | 72.6 | 5.49 (5.04, 5.99) |

| 14+ | 5845 (20.5) | 51.3 | 5.37 (4.96, 5.82) | 81.8 | 9.53 (8.75, 10.38) |

| Not enrolled throughout prior year | 723 (2.5) | 14.8 | 0.58 (0.43, 0.79) | 35.4 | 0.56 (0.42, 0.76) |

| Prior Year Mental Health ED Visits | |||||

| 0 | 25651 (89.8) | 31.3 | Ref | 55.7 | Ref |

| 1 | 1226 (4.3) | 35.3 | 0.94 (0.83, 1.07) | 63.9 | 0.99 (0.87, 1.13) |

| 2+ | 571 (2.0) | 30.6 | 0.75 (0.62, 0.91) | 59.9 | 0.77 (0.64, 0.93) |

| Not enrolled throughout prior year | 1103 (3.9) | 24.3 | 1.61 (1.00, 2.57) | 48.5 | 1.33 (0.83, 2.14) |

| Prior Year Mental Health Hospitalizations | |||||

| 0 | 23195 (81.2) | 30.6 | Ref | 54.8 | Ref |

| 1 | 2886 (10.1) | 35.5 | 0.87 (0.80, 0.95) | 62.9 | 0.85 (0.77, 0.93) |

| 2+ | 1457 (5.1) | 36.4 | 0.77 (0.68, 0.86) | 64 | 0.70 (0.62, 0.79) |

| Not enrolled throughout prior year | 1013 (3.5) | 23.4 | 0.93 (0.56, 1.55) | 48.1 | 1.52 (0.91, 2.51) |

ED: Emergency Department

Column percentages

Row percentages

Defined based on non-mental health conditions in the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm

Non-Hispanic Black children were less likely to have follow-up within 7 days (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.89, 95% CI 0.84, 0.94) and within 30 days (aOR 0.78, 95% CI 0.74, 0.83) than Non-Hispanic White children. Compared with children with capitated insurance, children with fee-for-service insurance were less likely to have follow-up within 7 days (aOR 0.72, 95% CI 0.68, 0.77) and within 30 days (aOR 0.83, 95% CI 0.79, 0.88). Follow-up visit rates increased as the number of prior year MH outpatient visits increased. Children with 14 or more prior year MH outpatient visits had 5.37 times higher adjusted odds of follow-up within 7 days (95% CI 4.96, 5.82) and 9.53 higher odds of follow-up within 30 days (95% CI 8.75, 10.38) compared to children with no prior year outpatient MH visits.

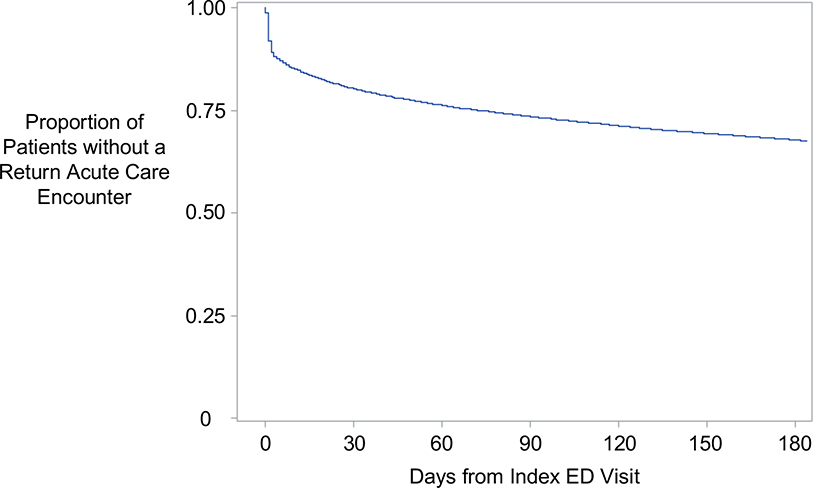

Return Mental Health Acute Care Encounters

Following the index ED MH discharge, 6.5% of children had a return acute care encounter within 7 days, 12.8% within 30 days, and 26.5% within 6 months (Table 2). The distribution of timing of return MH acute care encounters is illustrated in Figure 1. Of return MH acute care encounters, 49.7% were ED discharges (i.e., treat-and-release) and 50.3% were hospitalizations (with or without an associated ED visit). Rates of return MH acute care encounters varied significantly by socioeconomic and clinical characteristics including race/ethnicity, insurance plan type, number of comorbid MH conditions, and prior year MH ED visits and hospitalizations.

Table 2:

Return Mental Health Acute Care Encounters after Mental Health ED Discharges among Medicaid-Enrolled Children, by Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Return Acute Care Encounter within 7 days, % | P-value | Return Acute Care Encounter within 30 days, % | P-value | Return Acute Care Encounter within 6 months, % | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 6.5 | 12.8 | 26.5 | |||

| Age | 0.474 | 0.015 | 0.453 | |||

| 6–11 | 6.7 | 13.7 | 26.2 | |||

| 12–17 | 6.4 | 12.5 | 26.6 | |||

| Sex | 0.554 | 0.347 | 0.973 | |||

| Female | 6.6 | 12.6 | 26.5 | |||

| Male | 6.4 | 13 | 26.5 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.002 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 6.7 | 12.8 | 26.2 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6.2 | 12.8 | 26.9 | |||

| Hispanic | 7.1 | 11.7 | 24.0 | |||

| Other | 8.3 | 16.6 | 29.8 | |||

| Missing | 4.3 | 11.1 | 29.9 | |||

| Insurance Plan Type | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Capitated | 5.7 | 11.7 | 24.7 | |||

| Fee-for-service | 7.9 | 14.6 | 29.6 | |||

| Mental Health Diagnosis, Index ED Visita | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Depressive Disorders | 6.3 | 12.2 | 25.6 | |||

| Disruptive, Impulse Control and Conduct Disorders | 7.0 | 15.1 | 30.4 | |||

| Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders | 3.4 | 8.2 | 19.2 | |||

| Intentional Self-Harm | 11.7 | 15.4 | 25.7 | |||

| Other | 6.2 | 13.6 | 30.3 | |||

| Number of Distinct Mental Health Diagnosis Groups, Index ED Visit | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| 1 | 5.0 | 9.7 | 15.1 | |||

| 2 | 6.0 | 11.8 | 18.6 | |||

| 3 | 7.2 | 14.1 | 22.0 | |||

| 4+ | 8.7 | 17.4 | 27.7 | |||

| Calendar Days in ED during Index Visit | <.001 | 0.002 | <.001 | |||

| 1 day | 6.8 | 12.8 | 25.6 | |||

| 2 days | 4.8 | 11.6 | 28.0 | |||

| 3+ days | 6.1 | 14.8 | 34.3 | |||

| Non-Mental Health Comorbid Conditionb | 0.006 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Non-Chronic | 6.2 | 12.0 | 24.5 | |||

| Non-Complex Chronic | 6.5 | 13.0 | 27.9 | |||

| Complex Chronic | 7.5 | 15.1 | 31.1 | |||

| Prior Year Mental Health Outpatient Visits | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 4.6 | 8.0 | 12.2 | |||

| 1 | 5.7 | 11.7 | 18.8 | |||

| 2–6 | 6.6 | 13.7 | 21.6 | |||

| 7–13 | 7.3 | 14.8 | 24.2 | |||

| 14+ | 9.3 | 18.4 | 28.7 | |||

| Not enrolled throughout prior year | 5.4 | 11.9 | 18.5 | |||

| Prior Year Mental Health ED Visits | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 6.2 | 11.9 | 24.8 | |||

| 1 | 9.5 | 20.9 | 44.5 | |||

| 2+ | 13.5 | 31.0 | 61.5 | |||

| Not enrolled throughout prior year | 6.3 | 14.4 | 28.7 | |||

| Prior Year Mental Health Hospitalizations | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 5.4 | 10.3 | 21.8 | |||

| 1 | 9.8 | 21.7 | 45.7 | |||

| 2+ | 17.2 | 35.1 | 62.8 | |||

| Not enrolled throughout prior year | 5.9 | 13.2 | 26.9 |

ED: Emergency Department

Defined based on non-mental health conditions in Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve for Return Mental Health Acute Care Encounters following an Index Mental Health ED Discharge.

Return mental health acute care encounters include mental health ED visits and hospitalizations. Following the index ED MH discharge, 6.5% of children had a return acute care encounter within 7 days, 12.8% within 30 days, and 26.5% within 6 months.

Having an outpatient follow-up visit within 7 days was associated with a 27% decreased risk of having a return MH acute care encounter within 5 days of the index ED discharge (hazard ratio 0.73, 95% CI 0.62, 0.86) and an increased hazard for a return MH acute care encounter after 5 days of the index ED discharge (hazard ratio 1.07, 95% CI 1.02, 1.13). Having an outpatient follow-up visit within 30 days was associated with a 26% decreased risk for a return MH acute care encounter within 5 days of the index ED discharge (hazard ratio 0.74, 95% CI 0.63, 0.91) and an increased hazard for a return MH acute care encounter after 5 days of the index ED discharge (hazard ratio 1.20, 95% CI 1.14, 1.27).

Discussion

In a large sample of Medicaid-enrolled children discharged from the ED for a MH condition, less than one-third of children had outpatient MH follow-up within 7 days of discharge and under 60% had follow-up within 30 days. The odds for follow-up care were lower for non-Hispanic Black children and children with fee-for-service insurance, while the odds for follow-up care progressively increased with the number of prior year MH outpatient visits. Timely follow-up was associated with a lower risk of return for 5 days following the index ED discharge, but an increased risk thereafter.

Rates of timely follow-up among non-Hispanic Black children were particularly low, with 10% fewer receiving follow-up within 30 days compared to non-Hispanic White children. This is consistent with prior literature demonstrating that Black children are less likely than White children to receive outpatient MH treatment and underscores the need to remove barriers to MH care for Black children.25 Strategies to address this disparity may include reducing stigma to seeking MH care, improving diversity in the MH workforce, and increasing availability of community and school-based MH services.25–27 In addition, children with fee-for-service Medicaid were less likely to have outpatient follow-up than children enrolled in a managed care Medicaid program. While characteristics of enrollees in these plans may differ, managed care payment structures may also work to promote population health management and incentivize performance on quality measures.28 The strongest predictor of outpatient-follow up was having prior year MH outpatient visits, which may represent having an established MH provider, access to a usual source of ambulatory MH care, or having regular outpatient MH visits already scheduled prior to the ED visit.7 Interventions to improve follow-up after MH ED visits should focus on children with new MH diagnoses who have not previously engaged in outpatient MH care.

More than one-quarter of children with MH ED discharges in our sample had a return MH ED visit or hospitalization within 6 months, which is consistent with prior estimates.13,29 These high return rates suggest that EDs may not be effective sources of care for management of mental health crises for children and adolescents. We found that return acute care encounters were much more common among children with prior ED visits or hospitalizations within the past year. These may be markers of increased clinical severity or other unmeasured markers of a family’s likelihood to seek care, and may indicate an opportunity for targeted intervention.13

We found timely follow-up was associated with increased returns after 5 days from the index ED discharge. This aligns with prior studies examining follow-up after MH hospitalization, which paradoxically demonstrated an increased risk of readmission among children who established outpatient follow-up.11,30–32 Similarly, in a Canadian study of ED visits for anxiety or acute stress reactions, children who had follow-up outpatient MH care had a shorter ED return time.14 Unaccounted clinical severity may partially explain these findings, as children with greater clinical severity may be scheduled for more frequent follow-up visits or families may be more likely to attend visits. Timely follow-up may be a marker for having an established MH provider, decreased stigma in seeking MH care, or increased family resources.7 Outpatient follow-up may also directly result in increased acute care utilization, if symptoms are recognized during follow-up visits (such as worsening of suicidal ideation) that prompt appropriate referrals for acute MH care. Poor engagement in outpatient MH care does not appear to explain the increased risk of return, as children who followed up within 7 and 30 days had a median of 8 and 6 outpatient MH visits within 6 months, respectively.

This study has several limitations. We defined MH ED and outpatient follow-up visits using administrative HEDIS code sets, which may result in misclassification of some visits. Misclassification may have also occurred in our assignment of MH diagnosis groups to visits, and we may have incompletely adjusted for the severity or complexity of illness. Past year MH care may have been underestimated because we only required continuous enrollment for 6 months following the ED discharge. We assumed that visits with additional ED claims within 24 hours represented transfers, but this approach may have excluded some visits resulting in discharge to home and return within 24 hours. We could not determine which outpatient MH visits were scheduled specifically in response to the ED visit versus which had been previously scheduled. While we included data from 11 states across U.S. regions, the results may not be generalizable to all states. Finally, while we identified contact with outpatient follow-up care, we could not assess the quality of care provided, which may influence return rates. To address these limitations, prospective studies are needed to understand how MH service utilization after MH ED discharges varies based on predisposing factors, enabling factors, and the need for ongoing MH care (including illness severity), and to assess how the type and quality of follow-up care may influence return rates. Future research should also assess specific interventions to promote outpatient follow-up, such as care coordination and use of telemedicine, to determine if they reduce return visits or promote cost savings.33–35

Conclusions

Among Medicaid-enrolled children, rates of outpatient follow-up after a MH ED discharge are low, particularly for children who are Black, with fee-for-service insurance, and without prior MH outpatient visits. Following a MH ED discharge, more than one quarter of children return to the ED or hospital within 6 months. In addition, timely follow-up was associated with reduced returns within 5 days of the ED discharge, but an increased risk of return thereafter. Interventions that promote connection to follow-up care after a MH ED discharge should target linkage to outpatient services within 5 days to maximize opportunities to reduce return visits.

Supplementary Material

What’s Known on This Subject

Emergency department (ED) visit rates by children for mental health conditions are rising and return encounters are common. It is unknown if timely outpatient follow-up after a mental health ED visit decreases return ED visits and hospitalizations.

What This Study Adds

Only 56% of Medicaid-enrolled children received any outpatient follow-up within 30 days after a mental health ED discharge. Timely follow-up is associated with reduced return encounters for 5 days following the index visit and with increased returns thereafter.

Funding/Support:

Dr. Hoffmann was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (5K12HS026385-03) during this study.

Abbreviations:

- ED

Emergency Department

- MH

Mental Health

- ICD-10-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

- HEDIS

Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

- CAMHD-CS

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Disorders Classification System

- PMCA

Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures (includes financial disclosures): The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Cutler GJ, Rodean J, Zima BT, et al. Trends in Pediatric Emergency Department Visits for Mental Health Conditions and Disposition by Presence of a Psychiatric Unit. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(8):948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.05.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers SC, Mulvey CH, Divietro S, Sturm J. Escalating Mental Health Care in Pediatric Emergency Departments. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56(5):488–491. doi: 10.1177/0009922816684609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santillanes G, Axeen S, Lam CN, Menchine M. National trends in mental health-related emergency department visits by children and adults, 2009–2015. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(12):2536–2544. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Critical Crossroads: Pediatric Mental Health Care in the Emergency Department. A Care Pathway Resource Toolkit.; 2019. Accessed September 30, 2019. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/critical-crossroads/critical-crossroads-tool.pdf

- 5.Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(6):423–434. doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.106.003202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Follow-Up After Emergency Department Visit for Mental Illness - NCQA. Accessed February 1, 2021. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/follow-up-after-emergency-department-visit-for-mental-illness/

- 7.Doupnik SK, Passarella M, Terwiesch C, Marcus SC. Mental Health Service Use Before and After a Suicidal Crisis Among Children and Adolescents in a United States National Medicaid Sample. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(7):1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Children’s Health Care Quality Measures: Core Set of Children’s Health Care Quality Measures. Published 2022. Accessed April 30, 2022. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/performance-measurement/adult-and-child-health-care-quality-measures/childrens-health-care-quality-measures/index.html

- 9.MACPAC. Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP. Chapter 2: State Readiness to Report Mandatory Core Set Measures; 2020. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/state-readiness-to-report-mandatory-core-set-measures/

- 10.Zima BT, Edgcomb JB, Shugarman SA. National Child Mental Health Quality Measures: Adherence Rates and Extent of Evidence for Clinical Validity. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(1). doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-0986-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bardach NS, Bardach NS, Doupnik SK, et al. ED visits and readmissions after follow-up for mental health hospitalization. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackburn J, Sharma P, Corvey K, et al. Assessing the Quality Measure for Follow-up Care After Children’s Psychiatric Hospitalizations. Published online 2019:2154–1671. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2019-0137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leon SL, Cloutier P, Polihronis C, et al. Child and Adolescent Mental Health Repeat Visits to the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(3):177–186. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newton AS, Rosychuk RJ, Niu X, Radomski AD, McGrath PJ. Predicting time to emergency department return for anxiety disorders and acute stress reactions in children and adolescents: a cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(8):1199–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1073-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soleimani A, Rosychuk RJ, Newton AS. Predicting time to emergency department re-visits and inpatient hospitalization among adolescents who visited an emergency department for psychotic symptoms: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1). doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1106-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newton AS, Rosychuk RJ, Dong K, Curran J, Slomp M, McGrath PJ. Emergency health care use and follow-up among sociodemographic groups of children who visit emergency departments for mental health crises. Cmaj. 2012;184(12):665–674. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sen BP, Blackburn J, Morrisey MA, et al. Impact of Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act on Costs and Utilization in Alabama’s Children’s Health Insurance Program. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IBM MarketScan Research Databases. Accessed November 23, 2021. https://www.ibm.com/products/marketscan-research-databases/databases

- 19.Lee S, Herrin J, Bobo WV, Johnson R, Sangaralingham LR, Campbell RL. Predictors of return visits among insured Emergency Department mental health and substance abuse patients, 2005–2013. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(5):884–893. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.6.33850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zima BT, Gay JC, Rodean J, et al. Classification System for International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification and Tenth Revision Pediatric Mental Health Disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(6):620–622. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mental Health Disorder Codes. Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Research-and-Data/Pediatric-Data-and-Trends/2019/Mental-Health-Disorder-Codes

- 22.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On Racism: A New Standard For Publishing On Racial Health Inequities. Health Affairs Forefront. Published 2020. Accessed February 18, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200630.939347/full/

- 23.Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, et al. Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: A new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1647. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon TD, Haaland W, Hawley K, Lambka K, Mangione-Smith R. Development and Validation of the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA) Version 3.0. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(5):577–580. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alegría M, Vallas M, Pumariega AJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19(4):759–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garb HN. Race bias and gender bias in the diagnosis of psychological disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;90:102087. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brent DA, Goldstein TR, Benton TD. Bridging Gaps in Follow-up Appointments After Hospitalization and Youth Suicide: Mental Health Care Disparities Matter. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2013100. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinton E, Stolyar L. 10 Things to Know About Medicaid Managed Care. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published 2022. Accessed May 24, 2022. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-medicaid-managed-care/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marr M, Horwitz SM, Gerson R, Storfer-Isser A, Havens JF. Friendly Faces: Characteristics of Children and Adolescents With Repeat Visits to a Specialized Child Psychiatric Emergency Program. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(1):4–10. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlisle CE, Mamdani M, Schachar R, To T. Aftercare, emergency department visits, and readmission in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(3):283–293.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fontanella CA. The Influence of Clinical, Treatment, and Healthcare System Characteristics on Psychiatric Readmission of Adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(2):187–198. doi: 10.1037/a0012557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gearing RE, Mian I, Sholonsky A, et al. Developing a risk-model of time to first-relapse for children and adolescents with a psychotic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(1):6–14. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31819251d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lynch S, Witt W, Ali MM, et al. Care Coordination in Emergency Departments for Children and Adolescents With Behavioral Health Conditions: Assessing the Degree of Regular Follow-up After Psychiatric Emergency Department Visits. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(4):e179–e184. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griswold KS, Zayas LE, Pastore PA, Smith SJ, Wagner CM, Servoss TJ. Primary care after psychiatric crisis: A qualitative analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(1):38–43. doi: 10.1370/afm.760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, Landrum MB, Zhou L, Busch AB. Disparities in outpatient visits for mental health and/or substance use disorders during the COVID surge and partial reopening in Massachusetts. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;67:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.