Abstract

Background/Aim: Breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) are involved in the development of breast cancer and contribute to therapeutic resistance. This study aimed to investigate the anticancer stem cell (CSC) mechanism of 13-Oxo-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-Oxo-ODE) as a potent CSC inhibitor in breast cancer.

Materials and Methods: The effects of 13-Oxo-ODE on BCSCs were evaluated using a mammosphere formation assay, CD44high/CD24low analysis, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) assay, apoptosis assay, quantitative real-time PCR, and western blotting.

Results: We found that 13-Oxo-ODE suppressed cell proliferation, CSC formation, and mammosphere proliferation and increased apoptosis of BCSCs. Additionally, 13-Oxo-ODE reduced the subpopulation of CD44high/CD24low cells and ALDH expression. Furthermore, 13-Oxo-ODE decreased c-myc gene expression. These results suggest that 13-Oxo-ODE has potential as a natural inhibitor targeting BCSCs through the degradation of c-Myc.

Conclusion: In summary, 13-Oxo-ODE induced CSC death possibly through reduced c-Myc expression, making it a promising natural inhibitor of BCSCs.

Keywords: Breast cancer stem cells, 13-Oxo-ODE, c-Myc, natural compound, Salicornia herbacea L

Triple-negative breast cancer cells (TNBCs) are found in 10%-15% of breast cancer patients (1) and lack the expression of the estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (2). Cancer stem cells (CSCs) exhibit self-renewal and tumorigenic properties (3), and breast CSCs (BCSCs) have distinct properties including aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) 1 and CD44 expression (4,5). Treating CSCs is crucial in cancer therapy (6), and many studies have focused on targeting CSCs to improve cancer treatment outcomes (7).

The transcription factor c-Myc dimerizes with myc-associated factor X and binds to enhancer box sequences (8,9). The transcription of c-myc is initiated at three different sites, and c-Myc1, c-Myc2, or c-MycS are transcribed depending on the site (10). Importantly, c-Myc is associated with the maintenance and metabolism of CSCs (11), and several studies have indicated that c-Myc plays an important role in CSC regulation (12,13). For example, c-Myc is involved in the maintenance of colon CSCs (14), and the down-regulation of c-Myc expression leads to glioma cancer stem cell apoptosis (15) as well as the inhibition of BCSC formation (16). Therefore c-Myc is considered a promising therapeutic target for treating CSCs (17).

Salicornia herbacea L. (glasswort) is a plant found in salt marshes and at coastal locations in Korea, China, and the United States (18). This species contains many components that are used by humans, including saponins and flavonoids (19-22), and exhibits antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory activities (23-25). Solvent-extracted samples inhibit the growth of melanoma via the phosphorylated ERK and phosphorylated p38 signaling pathways in mice (23). The oxooctadecadienoic acid 13-Oxo-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-Oxo-ODE) has an anti-inflammatory effect (26) and acts as an agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (27). The effects of 13-Oxo-ODE on BCSCs and the mechanisms underlying these effects have not been studied.

In the present study, 13-Oxo-ODE was investigated as a promising compound for targeting BCSCs. We assessed the anti-BCSC effects of the isolated compound, finding that 13-Oxo-ODE inhibited the gene and protein expression levels of c-myc and c-Myc, respectively, as well as the formation of MDA-MB-231 BCSCs.

Materials and Methods

Materials, kits, and equipment. 60A silica gels, thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates, and Sephadex LH-20 resin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using a Shimadzu 20A system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Cancer cell proliferation was assayed using a CellTiter 96® Aqueous Solution Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). A BCSC inhibitor was purified from S. herbacea, and 13-Oxo-ODE was isolated.

Plant specimens. Salicornia herbacea specimens were purchased from Dasarang Ltd. (Sinan, Republic of Korea). This sample (no. 2020_10) was deposited at the Department of Biomaterial, Jeju National University Core-facility Center, Jeju, Republic of Korea.

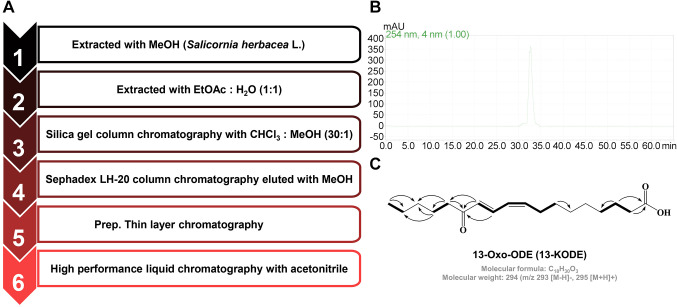

Isolation of 13-Oxo-ODE. The 13-Oxo-ODE used in this study was prepared as previously reported (26) and isolated as follows. Salicornia herbacea (1,000 g) was incubated with 100% methanol at 32˚C overnight in a shaking incubator. The isolation procedure is shown in Figure 1A. Briefly, methanol-extracted samples were combined with water at a 1:1 ratio. All methanol was evaporated, and the remaining sample was combined with the same volume of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate extracts were evaporated, dissolved with methanol, loaded onto a column filled with silica gel (3×30 cm), and isolated with a chloroform: methanol (30:1) solvent mixture. The active fractions were then separated and tested for anti-BCSC effects. Briefly, active fractions were loaded onto a column filled with Sephadex LH-20 gel (2.5×30.0 cm), isolated, and loaded onto a preparatory glass TLC plate (20×20 cm) in a chamber filled with a hexane:ethyl acetate:acetic acid (15.0:5.0:1.0) solvent mixture. The active fraction was analyzed via preparatory HPLC (Shimadzu). An ODS C18 column (10×250 mm) was used with a flow rate of 3 ml/min (acetonitrile proportion: 0%-60% for 20 min; 60%-100% for 10 min; 100% for 10 min; 100%-60% for 10 min, 60%-0% for 10 min; and 0% for 5 min). The peak of the purified sample was detected at a retention time of 32.8 min (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Procedure for isolating 13-Oxo-ODE from S. herbacea. (A) Flowchart of the purification of the BCSC inhibitor. (B) HPLC analysis of the BCSC inhibitor derived from S. herbacea. (C) Molecular structure of 13-Oxo-ODE, i.e., the CSC inhibitor isolated from S. herbacea.

Breast cancer cell lines and mammosphere culture. Two breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). BCSCs were cultured under humidified conditions (37˚C and 5% CO2) in MammoCult™ medium (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) in ultralow-attachment plates at 3×104 and 4×104 cells/well for MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, respectively. To determine mammosphere formation efficiency (MFE), BCSC formation was assayed using the NICE program (28).

Cell viability assay. Breast cancer cells were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates and incubated with various concentrations (0, 20, 40, 80, 100, 150, 200, 300, and 400 μM) of 13-Oxo-ODE for 24 h. Cell viability was determined using CellTiter 96™ solution according to the manufacturer’s protocol (29). Optical density (OD490) was measured using a VersaMax ELISA microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry analysis. After treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE for 24 h, breast cancer cells were treated with trypsin/EDTA (30). The detached cells were incubated with CD44-FITC and CD24-PE antibodies (BD, San Jose, CA, USA) for 20 min at 4˚C. The cells were then centrifuged, washed with 1X FACS buffer, and analyzed using an Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (BD). An ALDEFLUOR assay was conducted using cultured cells treated with 13-Oxo-ODE for 24 h, and the detached cells were assayed according to the manufacturer’s methods. ALDH1-positive cell populations were assayed using the Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (31).

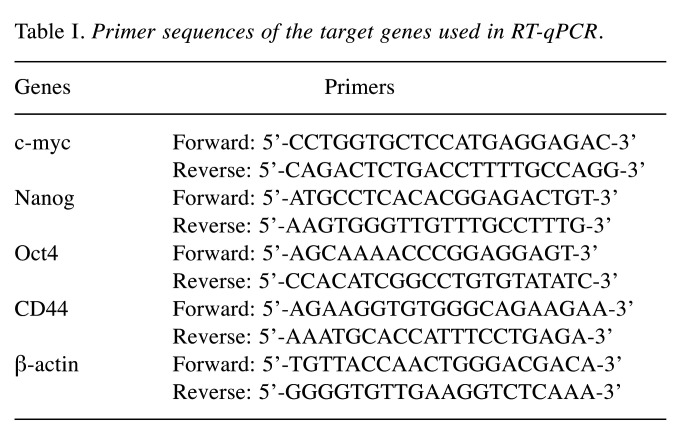

Quantitative real-time PCR. We extracted the total RNA from MDA-MB-231-derived mammospheres and performed quantitative real-time PCR using a Real-time One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The relative mRNA levels of genes were analyzed using the comparative CT method (30). The primers used in this analysis are listed in Table I. β-actin was used as an internal control gene.

Table I. Primer sequences of the target genes used in RT-qPCR.

Western blot analysis. Proteins were extracted from MDA-MB-231-derived mammospheres, subjected to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The membranes were incubated with Odyssey Blocking Buffer for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies against c-Myc (5605), lamin B (12586, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and β-actin (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) for >4 h at room temperature. The PVDF membranes were then washed twice with PBS-Tween 20 (0.1%, v/v) and incubated with secondary antibodies (IRDye 680RD- and IRDye 800W-labeled) for 1 h at room temperature. Western blot data were analyzed using an Odyssey CLx Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) (32).

Statistical analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All data are represented as mean±standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed via one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-hoc test. p-Values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

BCSC inhibitor purified from Salicornia herbacea. The preparation of 13-Oxo-ODE has been reported previously (26). The compound extracted from S. herbacea inhibited BCSC formation, and was purified based on a CSC inhibition assay (Figure 1A). The 13-Oxo-ODE was isolated using solvent extraction, column chromatography, and preparatory TLC. Finally, the compound was purified using preparatory HPLC (Figure 1B, C).

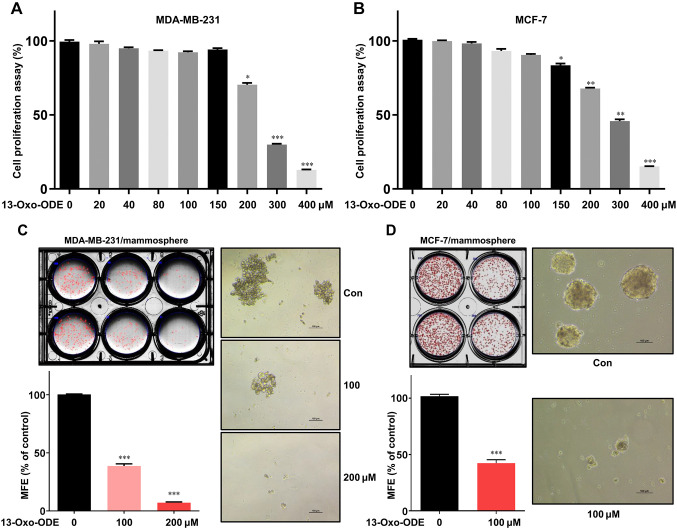

Breast cancer cell growth and mammosphere formation are inhibited by 13-Oxo-ODE. Breast cancer cells were cultured with a range of 13-Oxo-ODE concentrations (0-400 μM) for 24 h. The antiproliferative effects of 13-Oxo-ODE were tested using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay. The viability of both breast cancer cell lines was reduced by 13-Oxo-ODE treatment (Figure 2A, B). Additionally, in primary BCSCs treated with 13-Oxo-ODE, the compound reduced the number and size of mammospheres (Figure 2C, D).

Figure 2. Effects of 13-Oxo-ODE on breast cancer cell viability and mammosphere-forming efficiency. MDA-MB-231 (A) and MCF-7 (B) cells were cultured with 13-Oxo-ODE for 24 h. The cytotoxicity of 13-Oxo-ODE was tested using a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay. Treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE suppressed mammosphere formation. To produce mammospheres, 3×104 MDA-MB-231 cells (C) and 4×104 MCF-7 cells (D) per well were plated in ultralow-attachment 6-well plates. The mammospheres were then cultured with 13-Oxo-ODE. Images of representative mammospheres were obtained via inverted light microscopy (scale bar: 100 μm). The mammosphere formation efficiency (MFE) was determined. Data represent the mean±SD from three experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 using t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-hoc test.

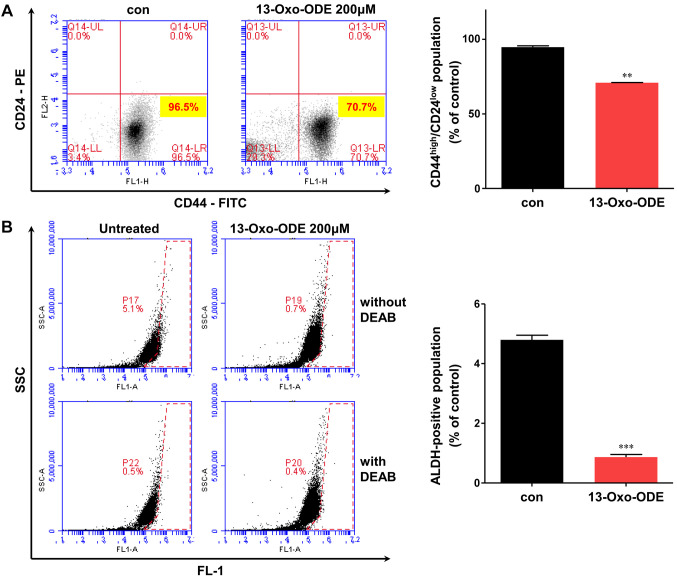

Treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE affects the properties of BCSCs. We examined two BCSC markers: CD44high/CD24low expressing and ALDH1-positive subpopulations. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 200 μM 13-Oxo-ODE, which reduced the CD44high/CD24low-expressing MDA-MB-231 cell subpopulation from 96.5% to 70.7% (Figure 3A) and the ALDH1-positive subpopulation from 5.1% to 0.7% (Figure 3B). Therefore, 13-Oxo-ODE modestly reduced the levels of BCSC markers.

Figure 3. Effects of 13-Oxo-ODE on CD44high/CD24low-expressing cells and ALDH1-positive cells. (A) CD44high/CD24low subpopulations treated with 13-Oxo-ODE (200 μM) or left untreated were tested via flow cytometry. (B) ALDH1-positive subpopulations were also assayed using flow cytometry. Red lines indicate the binding of an antibody without 13-Oxo-ODE. Data represent the mean±SD from three experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 using t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-hoc test.

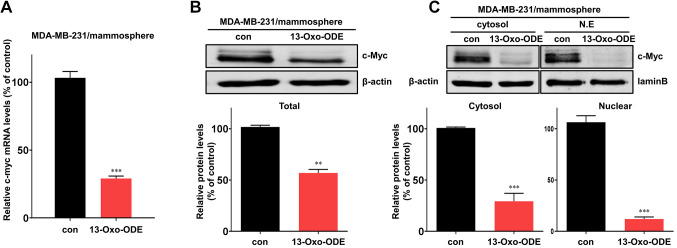

Treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE affects c-Myc regulation. c-Myc has been identified as a promising therapeutic target in breast cancer patients (33). Therefore, we examined the effects of 13-Oxo-ODE on c-myc transcription in BCSCs, finding that the compound decreased c-myc transcription levels in MDA-MB-231 mammospheres (Figure 4A). In addition, 13-Oxo-ODE reduced the total c-Myc protein expression level in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 4B). Nuclear proteins were isolated and c-Myc expression was measured. Levels of c-Myc in the cytosolic and nuclear fractions were decreased (Figure 4C). In summary, c-Myc is an important factor in mammosphere formation, and 13-Oxo-ODE inhibits c-Myc expression in MDA-MB-231 BCSCs.

Figure 4. Treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE regulates c-myc mRNA and protein expression. (A) c-myc gene transcript levels in CSCs were measured in mammospheres with or without 13-Oxo-ODE treatment using real-time PCR. β-actin was used as the internal control. (B) Using immunoblotting, total c-Myc protein levels were assayed in MDA-MB-231 cell mammospheres with (150 μM) or without 13-Oxo-ODE treatment for 24 h. Total lysates were used to analyze immunoblots with an anti-c-Myc antibody. β-Actin was used as the internal control. (C) After treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE, c-Myc protein levels in the cytosolic and nuclear fractions were analyzed in mammospheres using western blotting. Nuclear and cytosolic proteins were separated via SDS–PAGE, which was followed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Myc, anti-β-actin, and anti-Lamin B antibodies. Data are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. the DMSO-treated control group, using t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-hoc test.

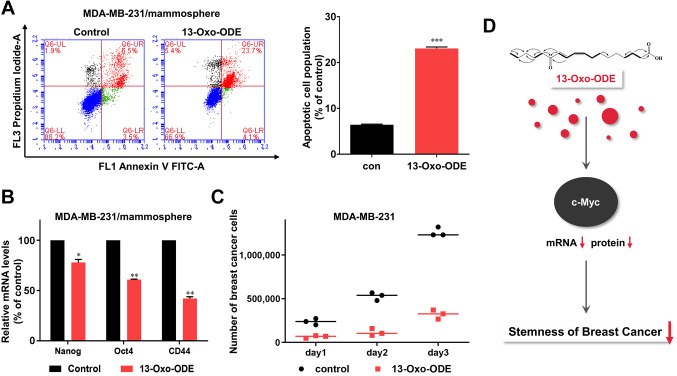

Treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE induces BCSC apoptosis and suppresses CSC marker gene transcription and mammosphere proliferation. BCSCs were treated with 150 μM 13-Oxo-ODE to assess the effects of the compound on apoptosis in mammospheres. Late apoptotic cell subpopulations increased from 6.5% to 23.7% (Figure 5A). Additionally, treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE down-regulated transcription levels of the CSC marker genes Nanog, CD44, and Oct4 (Figure 5B). Furthermore, 13-Oxo-ODE decreased BCSC proliferation (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Effects of 13-Oxo-ODE on apoptosis, cancer stem cell marker levels, and mammosphere growth. (A) Treatment with 13-Oxo-ODE increased apoptosis in BCSCs. Mammospheres were plated and cultured with 13-Oxo-ODE. Apoptosis was analyzed via Annexin V/propidium oxide (PI) staining after 13-Oxo-ODE treatment. (B) Transcriptional levels of CSC markers, including the Nanog, Oct4, and CD44 genes, were determined in mammospheres with or without 13-Oxo-ODE treatment using real-time PCR. β-actin was used as the internal control. Data represent the mean±SD of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 vs. the DMSO-treated control using t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post-hoc test. (C) Mammosphere growth was reduced by 13-Oxo-ODE treatment. Mammospheres treated with 13-Oxo-ODE or left untreated were separated into single cells, which were plated in equal numbers in 6 cm dishes. One, two, and three days later, the cells were counted. (D) Proposed model for 13-Oxo-ODE induced CSC death.

Discussion

Salicornia herbacea is a salt-tolerant plant species that grows along the coastline of Korea, China, and the United States. Its extracts have several useful properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-CSC properties (34-36). In the present study, we purified the compound 13-Oxo-ODE from S. herbacea using bioassay-based fractionation and determined its anti-BCSC effects. Also known as 13-KODE, 13-Oxo-ODE exerts anti-inflammatory effects by regulating MAPK signaling pathways (26). However, this is the first study to reveal that 13-Oxo-ODE inhibits BCSCs.

BCSCs are found in many breast cancer patients and have distinct properties such as differentiation and self-renewal (37). Biomarkers used to study BCSCs include CD44high/CD24low expression and ALDH expression (38). Breast cancer patients with BCSCs typically have poor prognosis, so studying the molecular mechanism of BCSCs may facilitate the development of effective treatment strategies for these patients (39). In the present study, we evaluated the anti-BCSC effects of 13-Oxo-ODE, finding that the compound inhibits BCSC formation and proliferation (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The levels of BCSC biomarkers, i.e., CD44high/CD24low-expressing and ALDH1-positive subpopulations, were reduced by 13-Oxo-ODE-treatment (Figure 3). Therefore, we showed that 13-Oxo-ODE exerts anti-BCSC effects.

The transcription factor c-Myc is a proto-oncogene and CSC survival factor that has been associated with the maintenance and self-renewal of CSCs through the regulation of several target genes (40). c-Myc is a short-lived protein owing to its degradation in ubiquitin-dependent or ubiquitin-independent pathways (41,42). It has been associated with the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (43) and maintenance of TNBC-derived CSCs (44). In the present study, 13-Oxo-ODE reduced the transcription level of c-myc as well as the total and nuclear c-Myc protein levels in BCSCs (Figure 4). The compound also inhibited the growth of BCSCs and the transcription levels of CSC-related genes (Figure 5).

Conclusion

The compound 13-Oxo-ODE can be isolated from S. herbacea using bioassay-guided fractionation. In the present study, it inhibited the formation of BCSCs and breast cancer cell proliferation. It also decreased the levels of BCSC markers, namely CD44high/CD24low-expressing and ALDH1-positive subpopulations, and some CSC-related genes. Furthermore, 13-Oxo-ODE regulated the transcript and protein levels of c-Myc, which is a known BCSC survival factor. Overall, regulating the c-Myc may be a strategic target for BCSC treatment and the natural compound from S. herbacea may be useful for treating breast cancer.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

HS Choi and YC Ko designed the experiments and performed all experiments. HS Choi and YC Ko wrote the manuscript. SL Kim helped design and perform the experiments. DS Lee supervised the study.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2020R1A2C1006316, 2022R1I1A1A01068288, and NRF-2016R1A6A1A03012862). It was also supported by a Korea Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (grant No. 2020R1A6C101A188).

References

- 1.Gucalp A, Traina TA. Triple-negative breast cancer: adjuvant therapeutic options. Chemother Res Pract. 2011;2011:696208. doi: 10.1155/2011/696208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–1948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Brien CA, Kreso A, Jamieson CH. Cancer stem cells and self-renewal. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(12):3113–3120. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricardo S, Vieira AF, Gerhard R, Leitão D, Pinto R, Cameselle-Teijeiro JF, Milanezi F, Schmitt F, Paredes J. Breast cancer stem cell markers CD44, CD24 and ALDH1: expression distribution within intrinsic molecular subtype. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(11):937–946. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2011.090456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcato P, Dean CA, Giacomantonio CA, Lee PW. Aldehyde dehydrogenase: its role as a cancer stem cell marker comes down to the specific isoform. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(9):1378–1384. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.9.15486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabian CJ, Kimler BF, Hursting SD. Omega-3 fatty acids for breast cancer prevention and survivorship. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0571-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baccelli I, Trumpp A. The evolving concept of cancer and metastasis stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2012;198(3):281–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201202014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cosgrave N, Hill AD, Young LS. Growth factor-dependent regulation of survivin by c-myc in human breast cancer. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;37(3):377–390. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubik D, Dembinski TC, Shiu RP. Stimulation of c-myc oncogene expression associated with estrogen-induced proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1987;47(24 Pt 1):6517–6521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao DJ, Dickson RB. c-Myc in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000;7(3):143–164. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dang CV. c-Myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445(7123):106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ieta K, Tanaka F, Haraguchi N, Kita Y, Sakashita H, Mimori K, Matsumoto T, Inoue H, Kuwano H, Mori M. Biological and genetic characteristics of tumor-initiating cells in colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(2):638–648. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9605-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang HL, Wang P, Lu MZ, Zhang SD, Zheng L. c-Myc maintains the self-renewal and chemoresistance properties of colon cancer stem cells. Oncol Lett. 2019;17(5):4487–4493. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Wang H, Li Z, Wu Q, Lathia JD, McLendon RE, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. c-Myc is required for maintenance of glioma cancer stem cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko YC, Choi HS, Kim JH, Kim SL, Yun BS, Lee DS. Coriolic acid (13-(S)-hydroxy-9Z, 11E-octadecadienoic acid) from Glasswort (Salicornia herbacea L.) suppresses breast cancer stem cell through the regulation of c-Myc. Molecules. 2020;25(21):4950. doi: 10.3390/molecules25214950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbadawy M, Usui T, Yamawaki H, Sasaki K. Emerging roles of C-Myc in cancer stem cell-related signaling and resistance to cancer chemotherapy: a potential therapeutic target against colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2340. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn HJ, You HJ, Park MS, Li Z, Choe D, Johnston TV, Ku S, Ji GE. Microbial biocatalysis of quercetin-3-glucoside and isorhamnetin-3-glucoside in Salicornia herbacea and their contribution to improved anti-inflammatory activity. RSC Adv. 2020;10(9):5339–5350. doi: 10.1039/c9ra08059g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tikhomirova NA, Ushakova SA, Tikhomirov AA, Kalacheva GS, Gros J-B. Salicornia europaea L.(fam. Chenopodiaceae) plants as possible constituent of bioregenerative life support systems’ phototrophic link. Journal of Siberian Federal University. 2008;1(2):118–125. doi: 10.17516/1997-1389-0271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JK, Park DHJJoFS, Nutrition Development of Kanjang (traditional Korean soy sauce) supplemented with glasswort (Salicornia herbacea l.) Journal of Food Science and Nutrition. 2011;16(2):165–173. doi: 10.3746/jfn.2011.16.2.165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Im SA, Kim K, Lee CK. Immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides isolated from Salicornia herbacea. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6(9):1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Min J, Lee D, Kim T, Park J, Cho T, Park D. Chemical composition of Salicornia Herbacea L. Preventive Nutrition and Food Science. 2018;7(1):105–107. doi: 10.3746/jfn.2002.7.1.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen T, Heo SI, Wang MH. Involvement of the p38 MAPK and ERK signaling pathway in the anti-melanogenic effect of methyl 3,5-dicaffeoyl quinate in B16F10 mouse melanoma cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2012;199(2):106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Xu Z, Li X, Sun J, Yao D, Jiang H, Zhou T, Liu Y, Li J, Wang C, Wang W, Yue R. Extraction, preliminary characterization and antioxidant properties of polysaccharides from the testa of Salicornia herbacea. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;176:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han EH, Kim JY, Kim HG, Chun HK, Chung YC, Jeong HG. Inhibitory effect of 3-caffeoyl-4-dicaffeoylquinic acid from Salicornia herbacea against phorbol ester-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;183(3):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ko YC, Choi HS, Kim SL, Yun BS, Lee DS. Anti-inflammatory effects of (9Z,11E)-13-Oxooctadeca-9,11-dienoic acid (13-KODE) derived from Salicornia herbacea L. on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine macrophage via NF-kB and MAPK inhibition and Nrf2/HO-1 signaling activation. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022;11(2):180. doi: 10.3390/antiox11020180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi H, Kim YI, Hirai S, Goto T, Ohyane C, Tsugane T, Konishi C, Fujii T, Inai S, Iijima Y, Aoki K, Shibata D, Takahashi N, Kawada T. Comparative and stability analyses of 9- and 13-Oxo-octadecadienoic acids in various species of tomato. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2011;75(8):1621–1624. doi: 10.1271/bbb.110254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JH, Choi HS, Kim SL, Lee DS. The PAK1-Stat3 signaling pathway activates IL-6 gene transcription and human breast cancer stem cell formation. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(10):1527. doi: 10.3390/cancers11101527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi HS, Kim SL, Kim JH, Lee DS. The FDA-approved anti-asthma medicine ciclesonide inhibits lung cancer stem cells through Hedgehog signaling-mediated SOX2 regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):1014. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko YC, Choi HS, Liu R, Kim JH, Kim SL, Yun BS, Lee DS. Inhibitory effects of Tangeretin, a citrus peel-derived flavonoid, on breast cancer stem cell formation through suppression of Stat3 signaling. Molecules. 2020;25(11):2599. doi: 10.3390/molecules25112599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu R, Choi HS, Zhen X, Kim SL, Kim JH, Ko YC, Yun BS, Lee DS. Betavulgarin isolated from sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) suppresses breast cancer stem cells through Stat3 signaling. Molecules. 2020;25(13):2999. doi: 10.3390/molecules25132999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ko YC, Liu R, Sun HN, Yun BS, Choi HS, Lee DS. Dihydroconiferyl ferulate isolated from Dendropanax morbiferus H.Lév. suppresses stemness of breast cancer cells via nuclear EGFR/c-Myc signaling. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022;15(6):664. doi: 10.3390/ph15060664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryu DS, Kim SH, Lee DS. Anti-proliferative effect of polysaccharides from Salicornia herbacea on induction of G2/M arrest and apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;19(11):1482–1489. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0902.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ha BJ, Lee SH, Kim HJ, Lee JY. The role of Salicornia herbacea in ovariectomy-induced oxidative stress. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29(7):1305–1309. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho JY, Kim JY, Lee YG, Lee HJ, Shim HJ, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Ham KS, Moon JH. Four new dicaffeoylquinic acid derivatives from Glasswort (Salicornia herbacea L.) and their antioxidative activity. Molecules. 2016;21(8):1097. doi: 10.3390/molecules21081097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang F, Xu J, Tang L, Guan X. Breast cancer stem cell: the roles and therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(6):951–966. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2334-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghasemi F, Sarabi PZ, Athari SS, Esmaeilzadeh A. Therapeutics strategies against cancer stem cell in breast cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;109:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scioli MG, Storti G, D’Amico F, Gentile P, Fabbri G, Cervelli V, Orlandi A. The role of breast cancer stem cells as a prognostic marker and a target to improve the efficacy of breast cancer therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(7):1021. doi: 10.3390/cancers11071021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):976–990. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeh E, Cunningham M, Arnold H, Chasse D, Monteith T, Ivaldi G, Hahn WC, Stukenberg PT, Shenolikar S, Uchida T, Counter CM, Nevins JR, Means AR, Sears R. A signalling pathway controlling c-Myc degradation that impacts oncogenic transformation of human cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(4):308–318. doi: 10.1038/ncb1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murai N, Murakami Y, Tajima A, Matsufuji S. Novel ubiquitin-independent nucleolar c-Myc degradation pathway mediated by antizyme 2. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3005. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21189-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikeguchi M, Hirooka Y. Expression of c-myc mRNA in hepatocellular carcinomas, noncancerous livers, and normal livers. Pathobiology. 2004;71(5):281–286. doi: 10.1159/000080063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang A, Qin S, Schulte BA, Ethier SP, Tew KD, Wang GY. MYC inhibition depletes cancer stem-like cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(23):6641–6650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]