Abstract

Background/Aim: Lacrimal sac tumors are rare tumor types, with a long time interval from disease onset to diagnosis. We aimed to investigate the characteristics and outcomes of patients with lacrimal sac tumors.

Patients and Methods: The medical records of 25 patients with lacrimal sac tumors initially treated at the Kyushu university hospital from January 1996 to July 2020 were reviewed.

Results: Our analysis included 3 epithelial benign tumors (12.0%) and 22 malignant (88.0%) tumors (squamous cell carcinoma, n=6; adenoid cystic carcinoma, n=2; sebaceous adenocarcinoma, n=2; mucoepidermoid carcinoma, n=1; malignant lymphoma, n=10). The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis was 14.7 months (median=8 months; range=1-96 months). The analysis of patients revealed that lacrimal sac mass (22/25, 88.0%) was the most frequent symptom and a possible tumor marker. Most epithelial benign (n=3) and malignant epithelial (n=12) tumors were treated surgically (14/15, 93.3%). One malignant case was treated with heavy ion beam therapy. Eight patients were treated with postoperative (chemo)radiation therapy because of positive surgical margins (including one unanalyzed case). Local control was ultimately achieved in all but one case. The patient survived for 24 months with immune checkpoint inhibitors and subsequent chemotherapy for local and metastatic recurrence.

Conclusion: We report our experience in the diagnosis and treatment of lacrimal sac tumors and analyze the clinical trends in cases involving these tumors. Postoperative radiotherapy and pharmacotherapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, may be useful for recurrent cases.

Keywords: Dacryocystitis, dacryocystorhinostomy, lacrimal sac tumors, lacrimal sac carcinoma

The lacrimal duct is composed of a lacrimal punctum, lacrimal duct, lacrimal sac, and nasolacrimal duct. While tumor development is rare (1), lacrimal sac tumors are the most common lacrimal duct tumor (2-5). There are few coherent reports, with most being case reports. Lacrimal sac tumors are usually malignant (55%-100%), (2-4,6) and early detection is desirable. Symptoms are unlikely to occur unless the tumor is enlarged. Tumor detection often occurs when there is obstruction of the lacrimal canal, such as tears, or lacrimal sac symptoms, such as reddening and pain in the skin. These non-specific clinical manifestations can cause misdiagnosis of lacrimal sac tumor as dacryocystitis, and patients continue to receive treatment for dacryocystitis, such as nasolacrimal duct cleaning, for a prolonged period of time (2,4).

Because of the various histological systems of lacrimal sac tumors, treatment should be based on histological type and degree of pathologic progression (3). Papillomas are the most common epithelial tumor (36%) and tend to recur (10%-40%), particularly inverted papilloma, due to its high rate of malignant transformation. Among malignant tumors, squamous cell carcinomas occur most frequently. Other malignancies include adenocarcinomas, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma. Despite treatment, however, rates of carcinoma recurrence and mortality are approximately 50% and approximately 37%-100%, respectively, with mortality rates increasing with recurrence. Local recurrence occurs because of inadequate resection margins due to adjacent anatomical structures. Multidisciplinary treatment, such as radiotherapy, is most effective. If the pathology requires resection, depending on the extent of tumor progression, adjacent structures, such as the eyeball, nasal bone, maxillary bone, or sinus, may have to be removed (1).

Advanced medical treatments such as heavy particle ion beam therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are used to treat malignancies. We herein report our experience in diagnosing and treating lacrimal sac tumors and analyze the clinical trends in lacrimal sac tumor cases in our hospital. We aimed to investigate the characteristics and outcomes of patients with lacrimal sac tumors.

Patients and Methods

Patients. Out of 547 cases of orbital-related tumors and lacrimal duct tumors treated at the Kyushu University Hospital from January 1996 to December 2019, 25 were diagnosed as lacrimal sac tumors. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients with lacrimal sac tumor treated at Kyushu University Hospital from January 1996 to December 2019; and 2) age ≥20 years. Patients who were <20 years of age were excluded from the study. This was a retrospective study with clinical data collected from medical records. All of these patients with lacrimal sac tumors were diagnosed by our ophthalmologist and head and neck surgeon based on the examination, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging findings, where the primary locus of the tumor was located in the lacrimal sac. Lacrimal sac tumors were diagnosed when the tumors were most predominantly located in the lacrimal sac region of the lacrimal duct. Pathological diagnoses were made by a pathologist in our hospital. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional review board of our hospital (reference number: 29-43) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

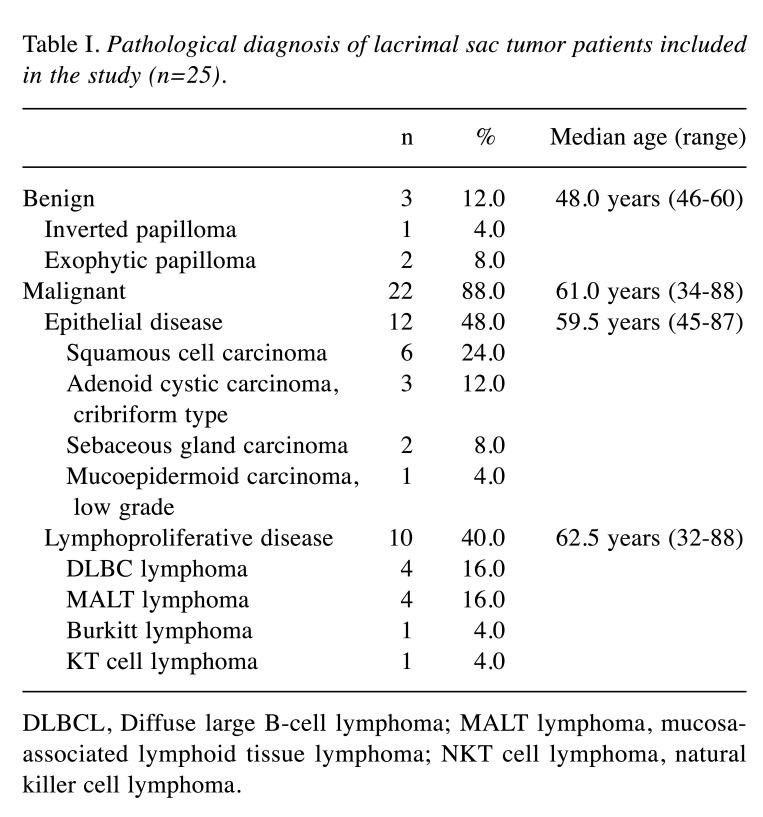

Patient information is summarized in Table I. There were no marked differences in the rate of males and females (14 males, 11 females). The average age was 58.7 (32-88) years for all cases, 51.3 (46-60) years old for benign epithelial tumors, 61.6 (45-87) years old for epithelial malignancies, and 57.5 (32-88) years old for non-epithelial malignancies.

Table I. Pathological diagnosis of lacrimal sac tumor patients included in the study (n=25).

DLBCL, Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MALT lymphoma, mucosaassociated lymphoid tissue lymphoma; NKT cell lymphoma, natural killer cell lymphoma.

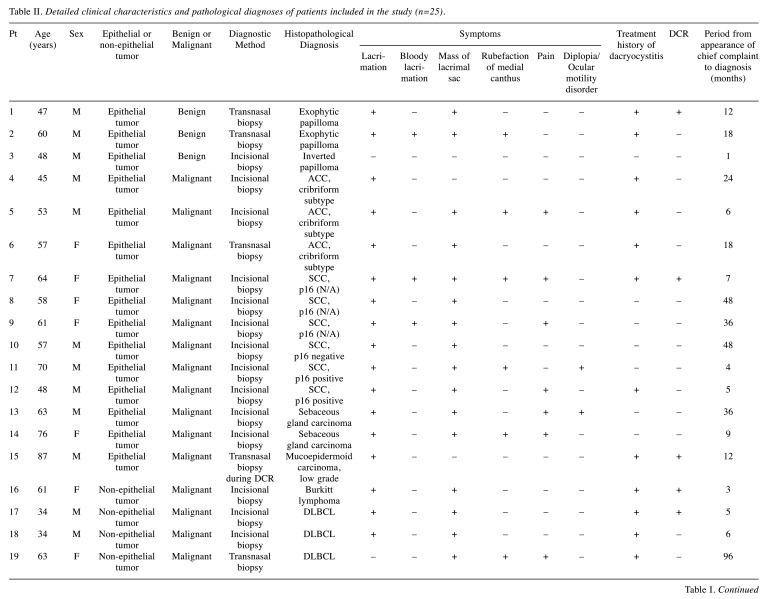

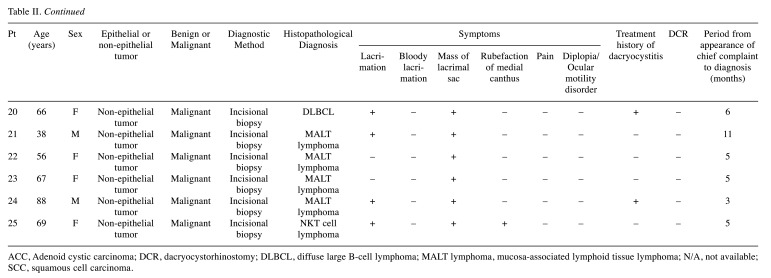

Pathological results are summarized in Table II. Malignancies accounted for 23 (88.0%) cases compared to 3 benign (12.0%) cases. All benign cases were papilloma. There were 12 epithelial malignancies (48.0%) and 10 non-epithelial malignancies (40.0%). Malignant epithelial tumors included six squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) of undetermined papilloma origin and various cancers. All non-epithelial malignancies were lymphomas.

Table II. Detailed clinical characteristics and pathological diagnoses of patients included in the study (n=25).

ACC, Adenoid cystic carcinoma; DCR, dacryocystorhinostomy; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MALT lymphoma, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma; N/A, not available; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

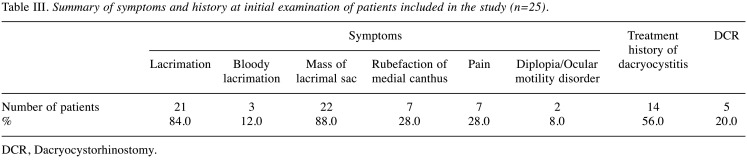

Detailed data for the 25 primary patients were obtained from medical records (Table II). In 22 of the 25 cases (88.0%), the most common subjective symptom at diagnosis was a mass in the lacrimal sac (Table III). Twenty-one patients (84.0%) presented with lacrimation. One of the three patients presenting with bloody lacrimation was diagnosed with benign epithelial tumor. Fourteen patients (56.0%) had a history of chronic dacryocystitis, and 5 had undergone dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR). Diagnoses were made by an external incision biopsy (n=20, 80.0%) or a transnasal biopsy (n=5, 20.0%). Only one case was diagnosed by a biopsy during DCR. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis was 17.2 months (median=8 months, range=1-96 months).

Table III. Summary of symptoms and history at initial examination of patients included in the study (n=25).

DCR, Dacryocystorhinostomy.

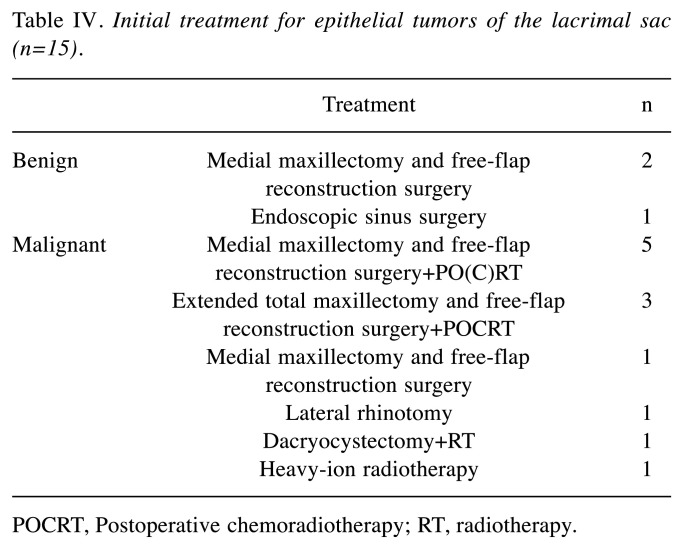

Treatment depended on the pathological diagnosis (Table IV). The initial treatment of benign (n=3) and epithelial malignancies (n=12) was surgery (14/15, 93.3%). Of the 11 patients with epithelial malignancies who underwent surgery, 8 were treated with postoperative (chemo) radiotherapy (Table V). Patients with sebaceous adenocarcinoma who did not receive surgical treatment chose heavy ion beam therapy but developed recurrence of neck lymph node metastasis and therefore underwent postoperative chemoradiation following neck dissection. Regarding the operated epithelial tumors, 11 of the 14 patients (78.6%) underwent free-flap mandibular reconstructions following resection, and 8 (57.1%) underwent simultaneous reconstruction with nonvascularized bone grafts with free bone grafting. Extended total maxillary resection with eyeball resection was performed in two squamous cell carcinoma patients and one sebaceous adenocarcinoma patient. Only two patients with SCC underwent neck dissection as the initial treatment, and one patient pathologically represented with neck lymph node metastases (submental and submandibular lymph node, no extranodal extension).

Table IV. Initial treatment for epithelial tumors of the lacrimal sac (n=15).

POCRT, Postoperative chemoradiotherapy; RT, radiotherapy.

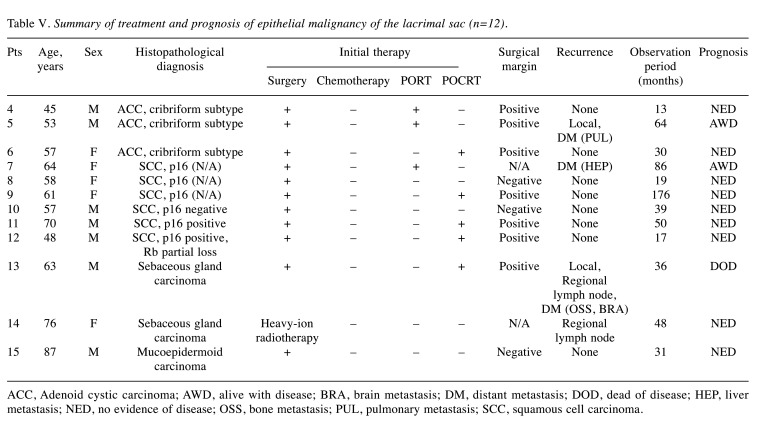

Table V. Summary of treatment and prognosis of epithelial malignancy of the lacrimal sac (n=12).

ACC, Adenoid cystic carcinoma; AWD, alive with disease; BRA, brain metastasis; DM, distant metastasis; DOD, dead of disease; HEP, liver metastasis; NED, no evidence of disease; OSS, bone metastasis; PUL, pulmonary metastasis; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Patient follow-up lasted until death or until the cut-off date (December 31, 2021). The median duration of follow-up from the diagnosis for epithelial malignancies was 37.5 (13-176) months. Three of the 12 patients had locoregional recurrence, but only one patient with sebaceous adenocarcinoma died of locoregional and brain/bone metastasis. Two patients survived with distant metastatic recurrences (one basaloid SCC and one ACC). Of the non-epithelial tumors, MALT lymphomas were treated with RT alone. Other malignant lymphomas were treated with chemotherapy and/or radiation (e.g., combination chemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone). No surgery other than a biopsy was performed for malignant lymphoma. The median follow-up was 39.5 (6-171) months, and all patients survived.

Discussion

To date, approximately 800 cases of rare lacrimal sac tumors have been reported (4). The present retrospective study summarized clinical data of 25 such cases treated at the Kyushu University Hospital. Two important concerns related to lacrimal sac tumors are as follows: 1) Most were malignant tumors but difficult to detect, and 2) R0 resection is often difficult because of the proximity of the eye to the tumor lesion and the facial changes that may result from surgical treatment. Therefore, multidisciplinary treatment combining surgery, radiation therapy, and drug therapy is considered necessary. Although a clinical view of lacrimal sac tumors has been proposed, the pathogenesis and effective treatment strategies are uncertain. Our study provides information on lacrimal sac tumors.

Lacrimal gland tumors often include symptoms of chronic dacryocystitis (4). Therefore, cases of dacryocystitis are often misdiagnosed as a tumor when a lacrimal sac biopsy is performed after a long period of chronic dacryocystitis. In our cases, the average time from the symptom onset to the diagnosis was 14.7 months (median=7 months, range=1-96 months), which is extremely long. A large percentage of patients showed epiphora and a history or symptoms of chronic dacryocystitis, such as running tears. However, adherent masses and masses beyond the medial canthal ligament were suspicious findings that should be noted (2,5). The percentage of cases with a mass above the lacrimal sac upon arrival at our hospital was 90.9%, and such lesions were not detected early. Masses in the lacrimal sac region progress after the diagnosis. Therefore, it is clinically difficult to differentiate from chronic dacryocystitis in the early stage.

Although DCR is commonly performed for chronic dacryocystitis, a neoplastic pathology was found in only 55 of 3,865 (1.42%) cases by a routine lacrimal sac wall biopsy performed at the time of DCR (7). The diagnostic rate of lacrimal sac tumors by a biopsy at the time of DCR is low, and a routine tear sac biopsy with DCR is not recommended unless a tumor is suspected. Therefore, imaging studies, such as magnetic resonance imaging, can help differentiate lacrimal sac tumors from chronic inflammatory diseases (4).

Our cases had a high rate of malignancy (22/25, 88.0%), similar to previous reports (>55%). Also similar to other studies was the high rate of malignant disease in patients >50 years old, while benign disease tended to occur in the younger age group (4,5). The pathological diagnosis of benign lacrimal sac tumors has been reported to include squamous cell papilloma, transitional epithelial papilloma, fibrous histiocytoma, and oncocytoma, in that order of frequency (2,4,8-10). Furthermore, the pathological diagnosis of malignant lacrimal sac tumors has been reported to include lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, transitional cell carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma, in that order of frequency. Our cases included sebaceous gland carcinomas, which are quite rare.

The main treatment of epithelial tumors is surgery, although the anatomical location of the tumor often does not allow for adequate resection margins. SCC is found in 5.0%-15.8% of cases reported for nasal sinus cancer and often coexists with inverted papilloma (11,12). Therefore, surgery is determined based on the presence of malignancy (13-15) Medial maxillectomy or extended maxillectomy was required in 11 cases in the present study, including 2 papilloma cases. After resection, 11 cases required free-flap reconstructive surgery. Advances in reconstructive surgery after resection can reduce the risk of postoperative infection and improve the cosmetic appearance. In the current treatment of epithelial malignancies, as head and neck cancer, multidisciplinary treatment, including postoperative (chemo)radiation therapy, is preferred. In 1982, Ni et al. reported a series of 71 patients from Shanghai with lacrimal sac carcinoma; the mortality rate was 43.7% despite orbital exenteration and other radical surgical measures being performed (2,4,16). However, recently, epithelial malignancy of the lacrimal sac has been treated with a multidisciplinary approach, as in our institution (3-5). Sawy et al. reported in 2013 that 3 cases of local recurrence in 14 patients were controllable with 100% locoregional control and a median follow-up time of 27 months (3). The overall survival rate for the same period was 79%, which was significantly better than in earlier reports. Multidisciplinary treatment in our 12 cases of epithelial malignancy resulted in good locoregional control (11/12; 91.7%). Distant metastasis occurred in three patients after initial treatment. One of the three patients had TNM recurrence of sebaceous carcinoma 12 months after initial treatment and died 36 months after initial treatment. Nivolumab, an ICI, was administered for six months until disease progression, and then paclitaxel was administered to stabilize the disease for nine months. ICIs and subsequent chemotherapy, which have been shown to be effective in other carcinomas, may be effective in treating recurrence and metastasis of lacrimal sac tumors (17,18). The aforementioned heavy particle therapy has also been reported as a treatment option for advanced local lesions of sinus tumors (19,20). Although an evidence base for these therapeutic modalities has not yet been established, their advent has led to dramatic changes in treatment approaches.

Another recent topic of interest is human papillomavirus (HPV)-related squamous cell carcinoma. In the field of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, the characteristics of HPV-infected cases in the oropharynx have attracted much attention over the past decade (21). HPV-related cancers in the nasal cavity have also been reported to have a good response to treatment and a good prognosis (22,23). Immunostaining results for p16 and Rb, which are surrogate markers for HPV-related cancers, can be combined to determine the presence or absence of HPV-related cancers (24). In the present study, one SCC case was also positive for p16 and Rb partial loss pattern, suggesting it to be an HPV-related cancer. Although this case had intraorbital extension and neck metastases, we assumed that it would respond to treatment as well as oropharyngeal and sinonasal cancers. With chemoradiotherapy (CRT) after eye-sparing surgery with neck dissection, the patient has been free from recurrence for 17 months since the treatment. In the future, there may be room to consider less-intense treatment or CRT alone for HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma of the lacrimal canal. The treatment strategy for malignant lacrimal sac tumors should be updated, which will require the accumulation of more case reports.

Several limitations associated with the present retrospective study warrant mentioning. Due to the small number of cases, variability of pathological diagnoses, and short follow-up period, caution should be practiced before applying these treatment approaches directly to clinical practice.

We reported our experience in treating lacrimal sac tumors at our Institution. At the time of initial diagnosis, a mass in the lacrimal sac region was observed in most cases, so subjective symptoms of lacrimal sac tumors may prove useful. Malignant tumors require multidisciplinary treatment, that was performed in our case, achieving good local control. In order to treat tumors in the fields of ophthalmology, head and neck surgery, plastic surgery, radiology, and oncology, cooperation among specialists in these fields is necessary. Postoperative radiotherapy as a local treatment may be useful. New options for making diagnoses and performing treatment are being introduced, and we need to take advantage of these advances to improve the patient prognosis. For this reason, we need to continue to examine these cases to help guide future treatment strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W.; Methodology, T.W. and R.Y.; Validation, T.W.; Investigation, T.W., M.T., H.T., R.J., K.H., M.M., and K.H.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, T.W.; Writing – Review & Editing, R.Y., M.T. and A.F.; Supervision, H.Y. and T.N.; Project Administration, R.Y.; Funding Acquisition, T.W. All Authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by a grant from JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP 20K09716 to Takahiro Wakasaki. We would like to thank Japan Medical Communication for the English language editing.

References

- 1.Cochran ML, Aslam S, Czyz CN. Anatomy, head and neck, eye nasolacrimal. Treasure Island, FL, USA, StatPearls Publishing. 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ni C, D’Amico DJ, Fan CQ, Kuo PK. Tumors of the lacrimal sac: a clinicopathological analysis of 82 cases. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1982;22(1):121–140. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198202210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Sawy T, Frank SJ, Hanna E, Sniegowski M, Lai SY, Nasser QJ, Myers J, Esmaeli B. Multidisciplinary management of lacrimal sac/nasolacrimal duct carcinomas. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29(6):454–457. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31829f3a73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishna Y, Coupland SE. Lacrimal sac tumors—a review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2017;6(2):173–178. doi: 10.22608/APO.201713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song X, Wang J, Wang S, Wang W, Wang S, Zhu W. Clinical analysis of 90 cases of malignant lacrimal sac tumor. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;256(7):1333–1338. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-3962-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjö LD, Ralfkiaer E, Juhl BR, Prause JU, Kivelä T, Auw-Haedrich C, Bacin F, Carrera M, Coupland SE, Delbosc B, Ducrey N, Kantelip B, Kemeny JL, Meyer P, Sjö NC, Heegaard S, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Primary lymphoma of the lacrimal sac: an EORTC ophthalmic oncology task force study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(8):1004–1009. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.090589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koturović Z, Knežević M, Rašić DM. Clinical significance of routine lacrimal sac biopsy during dacryocystorhinostomy: A comprehensive review of literature. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2017;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2016.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elner VM, Burnstine MA, Goodman ML, Dortzbach RK. Inverted papillomas that invade the orbit. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113(9):1178–1183. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100090104030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madreperla SA, Green WR, Daniel R, Shah KV. Human papillomavirus in primary epithelial tumors of the lacrimal sac. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(4):569–573. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sjö NC, von Buchwald C, Cassonnet P, Flamant P, Heegaard S, Norrild B, Prause JU, Orth G. Human papillomavirus: cause of epithelial lacrimal sac neoplasia. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85(5):551–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustafson C, Einhorn E, Scanlon MH, Morgenstern KE, Howlett PJ, Cohen NA. Synchronous verrucous carcinoma and inverted papilloma of the lacrimal sac: case report and clinical update. Ear Nose Throat J. 2013;92(10-11):E1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasumatsu R, Nakashima T, Sato M, Nakano T, Kogo R, Hashimoto K, Sawatsubashi M, Nakagawa T. Clinical management of squamous cell carcinoma associated with sinonasal inverted papilloma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2017;44(1):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Afrogheh AH, Jakobiec FA, Hammon R, Grossniklaus HE, Rocco J, Lindeman NI, Sadow PM, Faquin WC. Evaluation for high-risk HPV in squamous cell carcinomas and precursor lesions arising in the conjunctiva and lacrimal sac. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(4):519–528. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furdová A, Stopková A, Kapitánová K, Kobzová D, Babál P. Conjuctival lesions - the relationship of papillomas and squamous cell carcinoma to HPV infection. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 2018;74(3):92–97. doi: 10.31348/2018/1/2-3-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Ford J, Esmaeli B, Langer P, Esmaili N, Griepentrog GJ, Couch SM, Nguyen J, Gold KG, Duerksen K, Burkat CN, Hartstein ME, Gandhi P, Sobel RK, Moon JY, Barmettler A. Inverted papilloma of the orbit and nasolacrimal system. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;37(2):161–167. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanyinda N, Soni S, Ramadan A, Kidwell E. Complete resolution of a large squamous cell carcinoma of the lacrimal duct in a young African American male after non-surgical management. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2020;19:100842. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, Harrington K, Kasper S, Vokes EE, Even C, Worden F, Saba NF, Iglesias Docampo LC, Haddad R, Rordorf T, Kiyota N, Tahara M, Monga M, Lynch M, Geese WJ, Kopit J, Shaw JW, Gillison ML. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wakasaki T, Yasumatsu R, Uchi R, Taura M, Matsuo M, Komune N, Nakagawa T. Outcome of chemotherapy following nivolumab treatment for recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2020;47(1):116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toyomasu Y, Demizu Y, Matsuo Y, Sulaiman NS, Mima M, Nagano F, Terashima K, Tokumaru S, Hayakawa T, Daimon T, Fuwa N, Sakuma H, Nomoto Y, Okimoto T. Outcomes of patients with sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma treated with particle therapy using protons or carbon ions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;101(5):1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu W, Hu J, Huang Q, Gao J, Yang J, Qiu X, Kong L, Lu JJ. Particle beam radiation therapy for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Front Oncol. 2020;10:572493. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.572493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tân PF, Westra WH, Chung CH, Jordan RC, Lu C, Kim H, Axelrod R, Silverman CC, Redmond KP, Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiromaru R, Yamamoto H, Yasumatsu R, Hongo T, Nozaki Y, Hashimoto K, Taguchi K, Masuda M, Nakagawa T, Oda Y. HPV-related sinonasal carcinoma: Clinicopathologic features, diagnostic utility of p16 and Rb immunohistochemistry, and EGFR copy number alteration. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(3):305–315. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiromaru R, Yasumatsu R, Yamamoto H, Kuga R, Hongo T, Nakano T, Manako T, Hashimoto K, Wakasaki T, Matsuo M, Nakagawa T. A clinical analysis of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a single-institution’s experience. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279(7):3717–3725. doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-07236-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiromaru R, Yamamoto H, Yasumatsu R, Hongo T, Nozaki Y, Nakano T, Hashimoto K, Nakagawa T, Oda Y. p16 overexpression and Rb loss correlate with high-risk HPV infection in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2021;79(3):358–369. doi: 10.1111/his.14337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]