Abstract

Music interventions are effectively used to reduce anxiety in patients on maintenance hemodialysis (HD). The purpose of this review was to identify the methodological quality and examine the effectiveness of music interventions on anxiety in patients requiring maintenance HD. Articles were searched through 10 electronic databases, and relevant articles were systematically reviewed. Seven studies were analyzed for this study, and the combined seven studies revealed a medium effect size (pooled standardized mean differences [SMD] = 0.76; 95% CI: 0.55, 0.98). This study found that music interventions effectively reduce anxiety in patients on maintenance HD.

Keywords: Anxiety, hemodialysis, meta-analysis, music intervention, systematic review

Hemodialysis (HD) is the most common renal replacement therapy to maintain the lives of patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) (United States Renal Data System [USRDS], 2014). Yet patients requiring maintenance HD often have a negative perception of HD treatment. A patient who participated in a study by Hagren, Pettersen, Severinsson, Lützén, and Clyne (2001, p. 199) astutely named HD his “other job” because he spent at least four hours, three times a week receiving HD treatments, as well as extra hours traveling to and from the HD center, waiting for the machine at the center, and undergoing post-HD care (e.g., vascular access site hemostasis, weighing post-HD) (Hagren et al., 2001). Patients have negatively described their time spent in HD treatment as not worthwhile (Moran, Scott, & Darbyshire, 2009). They also often report psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, stress, depression, and a low quality of life (Feroze et al., 2012; Feroze, Martin, Reina-Patton, Kalantar-Zadeh, & Kopple, 2010).

Anxiety is a common emotion affecting patients on maintenance HD (Cukor et al., 2008; Janiszewska, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko, Gołebiewska, Majkowicz, & Rutkowski, 2013). Patients may experience anxiety because of anticipation of the treatment, feelings of stress, loss of control, or potential risk of complications (Gillen, Biley, & Allen, 2008). Anxiety is a state manifesting as apprehension, discomfort, and tension (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; Spielberger, 1972). Anxiety can be divided into state and trait anxiety; state anxiety is characterized by feelings of worry, nervousness, and muscle tension when confronting a stressful situation, whereas trait anxiety reflects a personal tendency in terms of responding to stressful situations (Spielberger, 1972). It is important to manage anxiety because untreated anxiety correlates with negative outcomes, such as reduced quality of life, poor adherence to HD treatment, and increased mortality (Birmelé, Le Gall, Sautenet, Aguerre, & Camus, 2012; Cukor et al., 2008; Johnson & Dwyer, 2008).

Various studies on anxiety reduction have been done using pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods. Pharmacological methods using sedatives or antianxiety medicines may have side effects (Beathard, Urbanes, Litchfield, & Weinstein, 2011). Consequently, alternatives to the pharmacological methods, such as music intervention, relaxation techniques, and hypnosis, have been introduced (Cantekin & Tan, 2013; Mahdavi, Gorji, Gorji, Yazdani, & Ardebil, 2013; Pyo, 2011; Untas et al., 2013). Music interventions, which are non-invasive and non-pharmacological approaches, are widely used for patients to reduce anxiety while waiting for surgeries and various procedures, such as coronary angiography (Kemper & Danhauer, 2005; McDonald, Zauszniewski, Bekhet, Dehelian, & Morris, 2011; Moradipanah, Mohammadi, & Mohammadil, 2009; Pittman & Kridli, 2011). Music interventions can be defined as “listening to music through music device or live music” (Chan, Wong, & Thayala, 2011, p. 334). Music interventions are also effectively used to improve physiopsychological signs and symptoms among patients on maintenance HD. They decrease anxiety in patients on maintenance HD (Cantekin & Tan, 2013; Kim, Lee, & Sok, 2006; Pothoulaki et al., 2008) because music acts as relaxation and diversion to others (Colwell, 1997).

Although there are a number of studies on using music interventions in reducing anxiety, they vary in terms of characteristics of the music interventions (e.g., type, frequency, dose, and/or interval of music interventions) and methodological quality, which may confound scientific research in this area. A systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizing multiple relevant studies can provide a useful guide for clinical decisions (Garg, Hackam, & Tonelli, 2008; Glass, McGaw, & Smith, 1981). However, despite its potential benefits, to date, there has been no systematic review of research studies that used music interventions for anxiolytic effects in patients on maintenance HD. Thus, the present study aims to systematically review research studies that used music interventions in this specific area and identify the effects of music interventions. The specific purposes of the study were to 1) investigate the overall characteristics of music interventions, 2) identify the methodological quality of research involving the use of music interventions, and 3) examine the effectiveness of music interventions on anxiety in patients requiring maintenance HD. This systematic review and meta-analysis provides information to better understand the impact of music interventions on reducing anxiety in patients on maintenance HD.

Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Literature Search

To identify study eligibility of this systematic review, the PICO (participants, intervention, comparison, and outcomes) framework was used. Experimental studies with randomized or clinical controlled trials that involved both treatment and control groups were included. Observational studies and intervention studies without control groups were excluded. Target populations (P) were adult patients 18 years and older on maintenance HD. Intervention (I) was defined as music therapy provided during HD, and comparison (C) was defined as routine HD. The principal outcome (O) was state anxiety measured by the State Anxiety scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983). Studies were excluded when the primary outcomes were something other than state anxiety, or anxiety was not measured by Spielberger’s state anxiety scale. No restrictions on publication time period and language were imposed. The included setting was incenter HD.

Search Methods

Articles were searched in January 2014 through 10 electronic databases: Cochrane Library, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, Medline, PubMed, and five Korean databases (KMbase, KoreaMed, Korea National Assembly Library, National Discovery for Science Leaders [NDSL], and RISS4U). Unpublished master’s theses or doctorate dissertations were included. Other articles were found from reviewing references of relevant full-text manuscripts on similar topics.

Study Data Extraction

All searched articles from the 10 databases were reviewed and extracted by two reviewers (investigators YK and YP). The reviewers selected studies by reviewing titles and abstracts based on the predefined selection criteria after excluding duplicated studies. Subsequently, the reviewers extracted the final studies by reading the full text of the articles. The study extraction processes and the final studies were reviewed and confirmed by all reviewers.

Data Analysis and Quality Assessment

Characteristics of the included studies.

Study characteristics were analyzed under the categories of type, frequency, dose, duration, and outcome of music intervention in the treatment group. The characteristics of the control group were also analyzed.

Methodological quality assessment.

A study quality assessment was performed by two investigators (YK & YP) and confirmed by the other investigator (LSE) using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QATQS) (National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools, 2008; Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins, & Micucci, 2004). The re viewers evaluated study quality independently using the QATQS criteria and a user’s guideline called a QATQS dictionary. Six components (selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals/dropouts) were rated as strong, moderate, or weak. In addition, intervention integrity (e.g., percentage of participants receiving the allocated intervention or exposure of interest) and analysis (e.g., use of appropriate statistical methods) were evaluated using multiple choice answers.

If there were no clear data on study methodology, data were obtained by emailing the primary study author. The two reviewers compared their individual assessment results. Discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion to reach an agreement.

Measurement of Treatment Effect and Assessment of Heterogeneity/Publication Bias

Meta-analysis was performed using the Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Standardized mean differences (SMD) were used for the effect size of anxiety, and 95% confidential intervals (CI) were computed to report the significance of the effect size. Cohen (1988) suggested criteria for interpreting effect sizes; small, medium, and large effect sizes are 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80, respectively.

Levels of heterogeneity were evaluated using a Q-statistic and I-squared (I2) test (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). I-squared test results of about 25%, 50%, and 75% indicate low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009; Higgins & Green, 2011). In order to obtain the pooled SMD estimate and its 95% CI, a fixed effects model rather than random effects model was used because of absence of heterogeneity. In addition, a funnel plot was created to evaluate possible publication bias; symmetry in the plot signifies a low possibility of publication bias.

Results

Study Selection

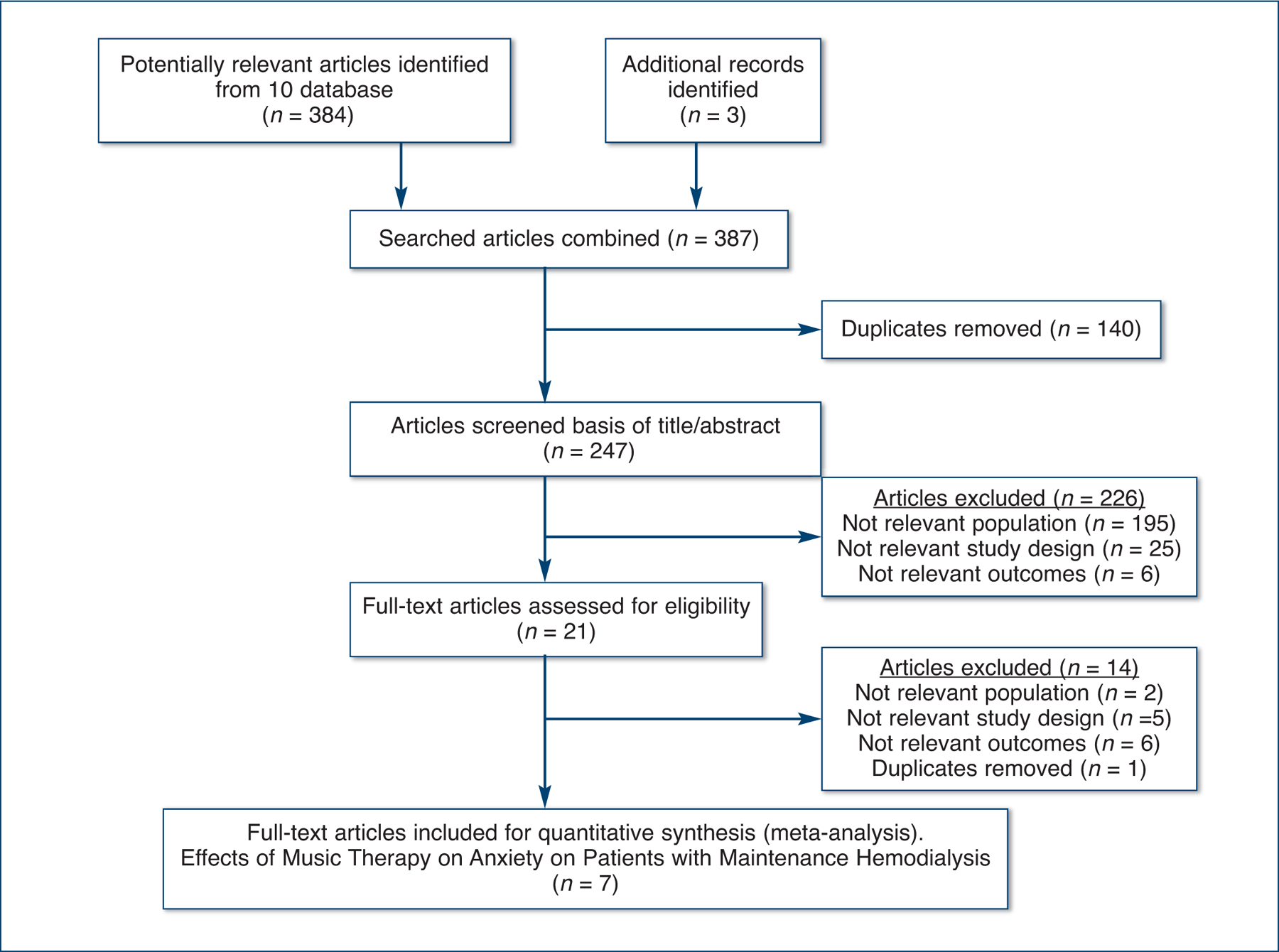

Figure 1 illustrates the process of searching relevant articles for the present meta-analysis. The study search initially yielded 384 articles from 10 electronic databases and reference review from relevant full-text manuscripts. One hundred forty duplicated articles were excluded. The titles and abstracts of 247 articles were reviewed, and 226 articles were then excluded because of an irrelevant study population (no patients on chronic HD), study design (no RCT or CCT using music interventions), or outcome (not anxiety). Subsequently, 21 full-text articles were evaluated for eligibility, and 14 articles were excluded again, namely studies having no control group, studies having different outcomes (stress, depression, etc.), and a duplicate study. Finally, a total of seven studies were included in the meta-analysis. The seven selected studies were reported in English or Korean between 1996 and 2013. Five studies were conducted in Korea (Choi, 1996; Chung, 2004; Kim et al., 2006; Lim, 2004; Pyo, 2011), one in Greece (Pothoulaki et al., 2008), and one in Turkey (Cantekin & Tan, 2013).

Figure 1. Process of Searching Relevant Articles.

Study Characteristics and Nature of Music Interventions

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies. Three studies (42.9%) were published, and four studies (57.1%) were unpublished master’s theses or doctoral dissertations. A total of 351 patients on maintenance HD participated in the seven studies: 176 patients were in the treatment group, and 175 patients were in the control group. All study participants in the treatment group had music interventions during their HD treatment, while the participants in the control group received routine HD care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author(s) (Published Year) | Stud Sources | Sample Size | Research Design | Music Intervention (MI) Description | MI Duration | Control Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG | CG | ||||||

| Choi (1996) | Master’s thesis in nursing | 15 | 17 | CCT | Routine HD with MI. Characteristics of music: Selected music by patients. Individual music listening of pop, native, and gospel song using cassette tape player. |

30 minutes during HD *for 3 weeks **6 times |

Routine HD |

| Lim (2004) | Master’s thesis in public health | 15 | 15 | CCT | Routine HD with MI. Characteristics of music: Selected music by patients. Individual music listening of pop, native, and gospel song using cassette tape or CD player. |

30 to 60 minutes during HD *3 weeks **6 to 9 times |

Routine HD |

| Chung (2004) | Doctoral dissertation in nursing | 24 | 23 | CCT | Routine HD with MI. Characteristics of music: Selected music by patients. Individual music listening of pop, native, gospel, and classical music using CD player. |

180 minutes during HD *4 weeks **12 times |

Routine HD |

| Kim, Lee, & Sok (2006) | Journal of nursing | 18 | 18 | CCT | Routine HD with MI. Routine HD with MI. Characteristics of music: Selected music by patients. Individual music listening using CD player. | 30 to 50 minutes during HD *3 weeks **9 times |

Routine HD |

| Pothoulaki et al. (2008) | Journal of health psychology | 30 | 30 | RCT | Routine HD with MI: Patients listened to the selected music from musical collection which included Greek fork music, ethnic music, jazz, classical, film soundtracks, and new age music. | NR | Routine HD |

| Pyo (2011) | Master’s thesis in nursing | 23 | 23 | CCT | Routine HD with MI. Routine HD with MI. Characteristics of music: Selected music by patients. Individual music listening using CD player. | 30 to 40 minutes during HD *4 weeks **12 times |

Routine HD |

| Cantekin & Tan (2013) | Journal of heart failure | 50 | 50 | CCT | Regular HD with MI: Downloaded Turkish art music songs (so-called Rast and Usak melody) using MP3 player. |

*1 week ** 3 times *** 30 minutes during HD |

Routine HD |

Period (weeks).

Total doses.

Music intervention time was verified through email with the primary author.

Notes: EG = experimental group; CG = control group; CCT = controlled clinical trials; RCT = randomized controlled trials; NR = not reported; MI = music intervention; CD = compact disc.

Six studies provided pre- and patient-selected music. For all interventions, the patients individually listened to music from pop, native, gospel, classical, culturally based, jazz, film soundtracks, or new age music genres on pre-recorded tapes, compact discs (CDs), or MP3 players during HD. The length and duration of the music interventions varied; 30 to 180 minutes of music interventions were delivered, but most interventions involved 30 to 60 minutes of music interventions per HD treatment session for 1 to 3 weeks (see Table 1). None of the studies used live music or indicated that they used certified music therapists for the music interventions.

Study Outcomes

Table 2 shows the outcomes of the included studies. Six studies (85.7%) reported a significantly decreased state anxiety after the music intervention. In one study, state anxiety had decreased after three weeks of music intervention, but the change was not statistically significant (p = 0.36) (Choi, 1996). Other outcomes, such as depression, perceived psychological stress, immune function, pain, blood pressure, and/or boredom, were also analyzed. Four out of five studies showed significant decreases in depression. Perceived psychological stress and boredom were found to be significantly lower after music interventions in two studies and one study, respectively.

Table 2.

Outcomes of the Selected Studies

| Author (Published year) | Anxiety Outcomes | Other Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Choi (1996) | State anxiety was decreased, but not statistically significant (p = 0.36). | Depression: Not significantly changed. |

| Lim (2004) | State anxiety was significantly decreased (p = 0.008). | Depression: Significantly decreased. |

| Chung (2004) | State anxiety was significantly decreased (p = 0.001). | Depression: Significantly decreased. Perceived psychological stress: Significantly decreased. Immune function (Number of total B and T lymphocytes, subtypes of T lymphocytes (CD4+ and CD 8+), and the ratio between CD4+ and CD8+): B lymphocytes were significantly increased. Others were not significantly changed; Vital signs: Systolic blood pressure: Decreased, but not statistically significant. Diastolic blood pressure: Significantly decreased. Pulse and respiratory rates: Not significantly changed. |

| Kim, Lee, & Sok (2006) | State anxiety was significantly decreased (p = 0.002). | Depression: Significantly decreased. |

| Pothoulaki et al. (2008) | State anxiety was significantly decreased (p < 0.005). | Pain: Not significantly changed. Blood pressure: Not significantly changed. |

| Pyo (2011) | Anxiety decreased (p = 0.007). | Depression: Significantly decreased. Boredom: Significantly decreased. |

| Cantekin & Tan (2013) | Both state and trait anxiety levels decreased (p < 0.01). | Perceived psychological stress: Significantly decreased. |

Methodological Study Quality Assessment

Table 3 displays the results of our methodological quality assessment using the QATQS and the QATQS dictionary (user’s guide). Six studies (85.7%) were rated “moderate” for selection bias, which assesses sample representativeness of the target population and percentages of selected individuals that agreed to participate in the study. All seven studies were rated “strong” for study design, which requires either randomized clinical trials or clinical controlled trials. Five studies were rated “moderate” for confounders, which evaluates percentages of relevant confounders that were controlled. All studies were rated “weak” for blinding, which examines blinding of the outcome to assessors and participants. All studies were rated “strong” for data collection methods, which identifies reliable and valid tools for primary outcomes. Five studies were rated ‘moderate’ for withdrawals/dropouts, which evaluates reports of the percentage of participants that completed the interventions.

Table 3.

Study Quality Assessment Using the QATQS

| Terms of bias | Degrees of Bias Risk | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Selection bias | Strong | 0 (0.0) |

| Moderate | 6 (85.7) | |

| Weak | 1 (14.3) | |

| Study design | Strong | 7 (100.0) |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0) | |

| Weak | 0 (0.0) | |

| Confounders | Strong | 0 (0.0) |

| Moderate | 5 (71.4) | |

| Weak | 2 (28.6) | |

| Blinding | Strong | 0 (0.0) |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0) | |

| Weak | 7 (100.0) | |

| Data collection methods | Strong | 7 (100.0) |

| Moderate | 0 (0.0) | |

| Weak | 0 (0.0) | |

| Withdraws and dropouts | Strong | 5 (71.4) |

| Moderate | 2 (28.6) | |

| Weak | 0 (0.0) |

Notes: QATQS = Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies.

Besides the six rating components, an evaluation of intervention integrity and analysis was performed. Six studies reported that 80% to 100% of participants received the allocated intervention or exposure of interest, while one study did not report this information (Intervention integrity). All seven studies used appropriate statistical methods (Analysis).

Music Intervention Effects on Anxiety and Publication Bias

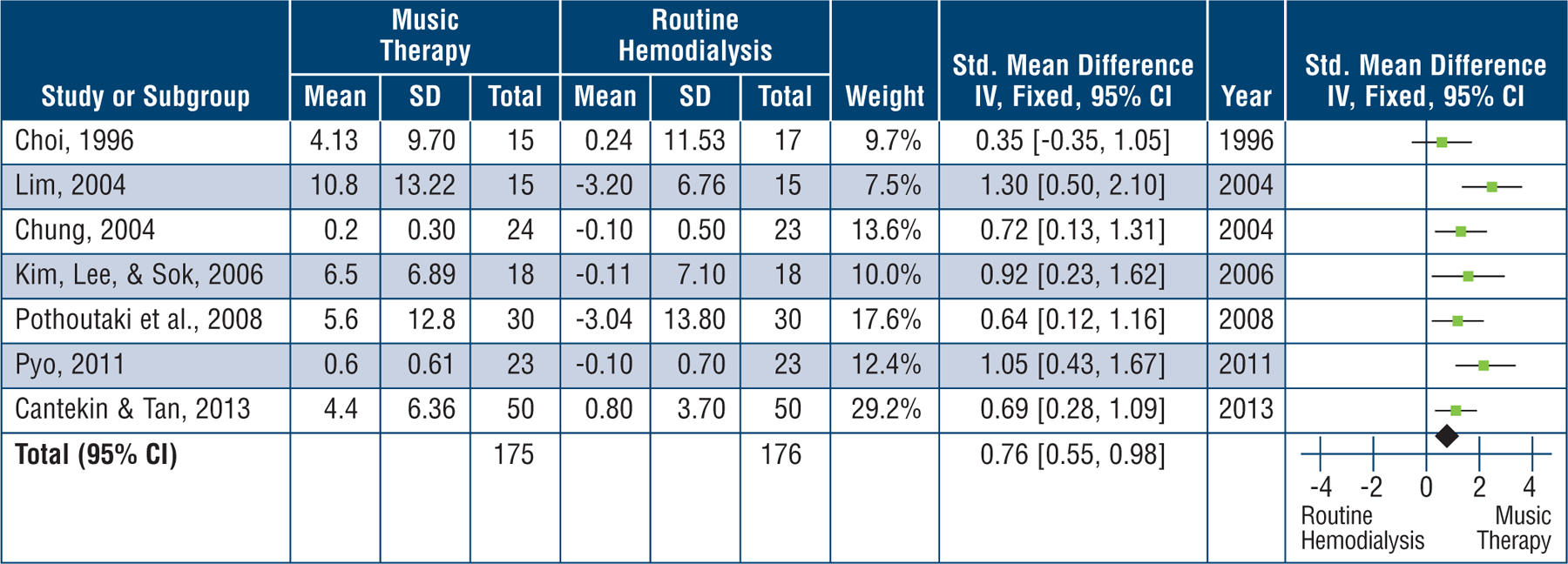

The heterogeneity test indicated no significant differences across the studies (Cochrane’s Q [Chi-squared, p = 0.62]; I2 = 0%), and thus, the fixed effects model was used for pooled estimates. Figure 2 shows the music intervention effects; the combined seven studies revealed a medium effect size (pooled SMD = 0.76; 95% CI: 0.55, 0.98), indicating that music intervention across the seven studies effectively improved anxiety.

Figure 2. Effect Size and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) by Music Intervention on Anxiety.

Heterogeneity: Chi2 = 4.43, df = 6 (p = 0.62); I2 = 0%.

Test for overall effect: Z = 6.87 (p < 0.00001).

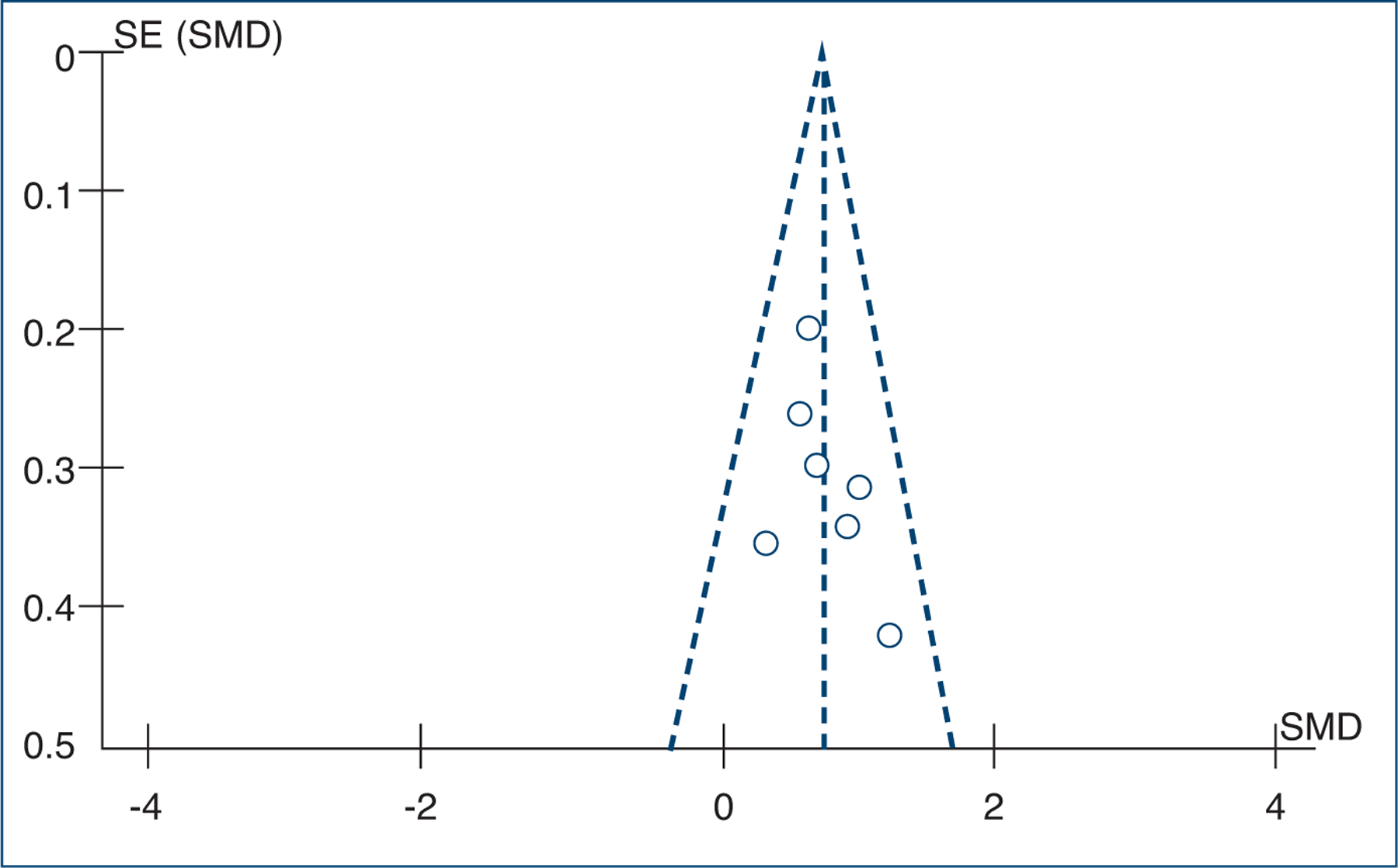

Figure 3 shows a funnel plot for evaluating publication bias. The plot is symmetrical, implying no publication bias in the seven studies selected for this meta-analysis.

Figure 3. Funnel Plot of the Included Studies.

Notes: SE = standard error; SMD = standardized mean difference.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to examine methodological quality and the effects of music intervention on anxiety for patients requiring chronic HD. Although this systematic review included a small number of studies (n = 7), we nonetheless found trends in music interventional studies for patients receiving in-center HD. A fair number of music interventional studies have reported benefits to music intervention, such as reducing depression and anxiety, and increasing quality of life in patients with ESRD. This meta-analysis also clarified the positive effects of music intervention in de creasing anxiety in patients on maintenance HD.

The selected studies used Spielberger’s STAI to measure anxiety and reported the Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.80 to 0.93. A study was excluded during the process of selecting articles for this study because it used a different instrument called Volicer & Bohannon’s Anxiety Questionnaire (Bae, 2009). Considering the number of participants – 175 and 176 patients participated in the intervention and control groups, respectively – an average of 25 persons (range: 15 to 50) participated in each study group, but none of the studies reported sample sizes based on an appropriate power calculation.

Six of the seven selected studies (85.7%) reported that music intervention has significant effects on reducing anxiety, while one study (Choi, 1996) showed no effects. Choi (1996) explained that the possible reasons could be 1) the pre-mean anxiety score was not high enough in the treatment group (treatment group’s pre-mean anxiety score, 47.13 ± 11.16, and post-mean anxiety score, 43.00 ± 6.36 vs. control group’s pre-mean anxiety score, 47.76 ± 10.56, and post-mean anxiety score, 47.52 ± 12.39; z = 0.09); and 2) the small sample size (treatment group, n = 15 vs. control group, n = 17). Yet the study did not report what a proper sample size would be for the intervention.

The frequency and interval of music provided to the participants varied in the selected studies. Listening durations ranged from 30 to 180 minutes, and frequencies ranged from 3 to 12 times. In a study conducted by Cantekin and Tan (2013), participants listened to pre-recorded music for 30 minutes three times, but despite the short music intervention duration compared to the other selected studies, they reported significantly reduced anxiety. Similarly, an integrative review on music intervention for pre-operative anxiety pointed out the variability in the duration of the music intervention; a minimum of 15 to 20 minutes (once) of music intervention appears to reduce pre-operative anxiety (Pittman & Kridli, 2011).

Chan and colleagues (2011) also reported music interventions that were diverse in duration or frequency in their systematic review evaluating the effectiveness of listening to music in reducing depressive symptoms in adults. It seems there is a lack of clear standards or guidelines for music interventions. Hence, more studies are required to ascertain the most appropriate music treatment modalities to reduce anxiety in patients on maintenance HD.

To avoid contamination or compensatory rivalry (threats to internal validity) in the selected studies, three studies assigned treatment groups and control groups to a different hospital and the other three studies to different HD schedules (e.g., Monday, Wednesday, and Friday vs. Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday). One study did not report on how to avoid the possibility of the treatment and control groups co-mingling and possibly affecting study outcomes.

Considering regional distribution, five studies were conducted in Korea, one in Greece, and one in Turkey. More studies written in Korean were included. The reason might be that five extra Korean databases were used to search for relevant studies, and a few unpublished studies, such as master’s or doctoral theses, were included.

In the methodological study quality assessment, controlling confounders and blinding methods were found to be poor. None of the studies included studies in the review were rated “strong” for confounders, which evaluates the percentage of relevant confounders controlled for. Although the studies included pre-tested whether there were significant differences in sociodemographic characteristics between the intervention and control groups, future studies should analyze the effects of music interventions on anxiety according to various personal factors, such as age, gender, educational background, HD vintages, emotional status, music preference, and previous music experiences, or they should rigorously control possible confounding factors since they influence the patients’ responses to music (Bradt, Dileo, & Shim, 2013; Landreneau, Lee, & Landreneau, 2010; Pelletier, 2004). Further, medications such as anxiolytics can influence the effects of music interventions and be confounders in music interventions (Bradt et al., 2013). However, none of the studies included in the review described inclusion or exclusion of patients who took anxiolytics before or during HD. Other factors, such as noise or alarm sounds from machines, may influence music effects, but no study reported on this factor. These factors should also be analyzed and/or controlled in future studies.

Another poorly rated component in the study quality assessment (7 out of 7, “weak”) was blinding. As Bradt and colleagues (2013) pointed out, because of the nature of music interventions, it might be difficult or impossible for the outcome assessors not to be aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants, or for the participants not to be aware of the research questions or purposes.

Our study search initially yielded 387 articles from 10 electronic databases; 7 studies were included in the meta-analysis based on the study selection criteria. Considering the number of advantages associated with music intervention and no restrictions with times of publication, there were relatively few music interventional studies on anxiety in patients on maintenance HD. The reason may stem from the report by Cukor and colleagues (2008) that anxiety is often not perceived as a discrete condition, and consequently, has been relatively understudied in patients with ESRD.

As secondary outcomes of music interventions, physiological responses to music interventions (e.g., pain level perception, immune function, or blood pressure) were also evaluated in addition to psychological responses. Physical responses combined with the psychological effectiveness of music during HD warrants additional investigation.

All studies included in the review used pre-recorded music, not live music. In addition, there was no mention of using a music therapist for the interventions. Future research exploring differences in the effectiveness of using live music vs. pre-recorded music (Nightingale, Rodriguez, & Carnaby, 2013), or music therapists vs. clinicians, such as dialysis nurses (Kim, 2002), may provide valuable information to researchers and clinicians who plan to conduct music interventions in HD centers.

Two potential limitations should be considered when interpreting or generalizing the results from this study. First, there are possibilities of publication bias related to studies with non-significant findings not being published. Second, more articles written in Korean were included in the study, which might provide bias toward the results of this review.

Conclusions and Implications

This integrative review and meta-analysis identified a positive effect of music interventions on reducing anxiety among patients on maintenance HD, implying that patients’ music listening can relieve feelings of anxiety. The music interventions used in the selected studies varied in terms of treatment frequency, dose, and interval. The methodological quality of research also varied. Prior to further systematic evaluation, more numbers of well-controlled clinical studies to reduce anxiety in patients on maintenance HD are warranted so that appropriate music interventional modalities can be ensured for the patients and clinicians in this area.

Goal

To identify the methodological quality and examine the effectiveness of music interventions on anxiety in patients requiring maintenance hemodialysis.

Objectives

Discuss the impact anxiety has on patients requiring maintenance hemodialysis.

Explain the positive effects of music intervention for patients experiencing anxiety while on hemodialysis as outlined in this current study.

List the rationale for future research regarding music intervention with patients being treated for end stage renal disease with hemodialysis.

This offering for 1.3 contact hours is provided by the American Nephrology Nurses’ Association (ANNA).

American Nephrology Nurses’ Association is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center Commission on Accreditation.

ANNA is a provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, provider number CEP 00910.

This CNE article meets the Nephrology Nursing Certification Commission’s (NNCC’s) continuing nursing education requirements for certification and recertification.

Footnotes

Statement of Disclosure: The authors reported no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this continuing nursing education activity.

Note: Additional statements of disclosure and instructions for CNE evaluation can be found on page 348.

Contributor Information

Youngmee Kim, Chung-Ang University, Red Cross College of Nursing, Seoul, Korea, and a Virtual International Member of ANNA..

Lorraine S. Evangelista, University of California, Irvine (UCI), Program of Nursing Science, Irvine, CA..

Yong-Gyu Park, The Catholic University of Korea, Department of Biostatistics, Seoul, Korea..

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (DSM-5) (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bae YS (2009). The effects of music therapy in fatigue and anxiety in hemodialysis patients. Master’s thesis, Dong-Eui University, Busan, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Beathard GA, Urbanes A, Litchfield T, & Weinstein A (2011). The risk of sedation analgesia in hemodialysis patients undergoing interventional procedures. Seminars in Dialysis, 24(1), 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmelé B, Le Gall A, Sautenet B, Aguerre C, & Camus V (2012). Clinical, sociodemographic, and psychological correlates of health-related quality of life in chronic hemodialysis patients. Psychosomatics, 53(1), 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, & Rothstein HR (2009) Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex, UK: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bradt J, Dileo C, & Shim M (2013). Music interventions for preoperative anxiety. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006908.pub2/pdf/standard doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006908.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantekin I, & Tan M (2013). The influence of music therapy on perceived stressors and anxiety levels of hemodialysis patients. Renal Failure, 35(1), 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J (1996). Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression for hemodialysis patient. Master’s Thesis, Korea University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Chan MF, Wong ZY, & Thayala NV (2011). The effectiveness of music listening in reducing depressive symptoms in adults: A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 19(6), 332–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y (2004). The effects of music therapy on stress, anxiety, depression, and immune function in the hemodialysis patients. Doctor’s thesis, Catholic University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Lawrence Earlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell C (1997). Music as a distraction and relaxation to reduce chronic pain and narcotic ingestion: A case study. Music Therapy Perspectives, 15(1), 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cukor D, Coplan J, Brown C, Friedman S, Newville H, Safier M, … Kimmel PL (2008). Anxiety disorders in adults treated by hemodialysis: A single-center study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 52(1), 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feroze U, Martin D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kim JC, Reina-Patton A, & Kopple JD (2012). Anxiety and depression in maintenance dialysis patients: Preliminary data of a cross-sectional study and brief literature review. Journal of Renal Nutrition, 22(1), 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feroze U, Martin D, Reina-Patton A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, & Kopple JD (2010). Mental health, depression, and anxiety in patients on maintenance dialysis. Iranian Journal of Kidney Diseases, 4(3), 173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg AX, Hackam D, & Tonelli M (2008). Systematic review and meta-analysis: When one study is just not enough. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3, 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen E, Biley F, & Allen D (2008). Effects of music listening on adult patients’ pre-procedural state anxiety in hospital. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 6(1), 24–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass GV, McGaw B, & Smith ML (1981). Meta-analysis in social research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E, Lützén K, & Clyne N (2001). The haemodialysis machine as a life-line: Experiences of suffering from end-stage renal disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34(2), 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, & Green S (Eds.). (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 5.1.0. Retrieved from www.cochrane-handbook.org

- Higgins JPT, & Thompson SG (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21, 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiszewska J, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M, Gołebiewska J, Majkowicz M, & Rutkowski B (2013). Determinants of anxiety in patients with advanced somatic disease: Differences and similarities between patients undergoing renal replacement therapies and patients suffering from cancer. Interna tional Urology & Nephrology, 45, 1379–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, & Dwyer A (2008). Patient perceived barriers to treatment of depression and anxiety in hemodialysis patients. Clinical Nephrology, 69(3), 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper KJ, & Danhauer SC (2005). Music as therapy. Southern Medical Journal, 98(3), 282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S (2002). A meta-analysis of the effects of music therapy outcome. Master’s thesis, Sookmyung Women’s University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KB, Lee MH, & Sok SR (2006). The effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 36(2), 321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landreneau K, Lee K, & Landreneau MD (2010). Quality of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis and renal transplantation – A meta-analytic review. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 37(1), 37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SM (2004). The influence of music therapy on depression and anxiety in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Master’s thesis, Daejeon University, Daejeon, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi A, Gorji MA, Gorji AM, Yazdani J, & Ardebil MD (2013). Implementing Benson’s relaxation training in hemodialysis patients: changes in perceived stress, anxiety, and depression. North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 5(9), 536–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald PE, Zauszniewski JA, Bekhet AK, DeHelian L, & Morris DL (2011). The effect of acceptance training on psychological and physical health outcomes in elders with chronic conditions. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association, 22(2), 11–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradipanah F, Mohammadi E, & Mohammadil AZ (2009). Effect of music on anxiety, stress, and depression levels in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 15(3), 639–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran A, Scott PA, & Darbyshire P (2009). Existential boredom: The experience of living on haemodialysis therapy. Journal of Medical Humanities, 35(2), 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. (2008). Quality Assessment Tool for Qualitative Studies. Hamilton, ON, Canada: McMaster University. Retrieved from http://www.nccmt.ca/registry/view/eng/14.html [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale CL, Rodriguez C, & Carnaby G (2013). The impact of music interventions on anxiety for adult cancer patients: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 12(5), 393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier CL(2004). The effect of music on decreasing arousal due to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Music Therapy, 41(3), 192–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman S, & Kridli S (2011). Music intervention and preoperative anxiety: An integrative review. Inter - national Nursing Review, 58(2), 157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothoulaki M, Macdonald RA, Flowers P, Stamataki E, Filiopoulos V, Stamatiadis D, & Stathakis C (2008). An investigation of the effects of music on anxiety and pain perception in patients undergoing haemo dialysis treatment. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(7), 912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyo SJ (2011). The effect of music therapy on anxiety, depression and boredom in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Master’s thesis, Chonnam National University, Gwangju, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD (1972). Conceptual and methodological issues in anxiety research. In Spielberger CD (Ed.), Anxiety: Current trends in theory and research (pp. 481–492). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, & Jacobs GA (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, & Micucci S (2004). A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1(3), 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Renal Data System (USRDS). (2014). USRDS 2014 annual data report: Atlas of chronic kidney dis- ease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. Retrieved from http://www.usrds.org

- Untas A, Chauveau P, Dupré-Goudable C, Kolko A, Lakdja F, & Cazenave N (2013). The effects of hypnosis on anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleepiness in people undergoing hemodialysis: A clinical report. International Journal of Clinical & Experimental Hypnosis, 61(4), 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]