Abstract

Context

Lower 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels have consistently been associated with higher mortality among participants with colorectal cancer (CRC).

Objective

To investigate whether the association between 25(OH)D and CRC mortality differs according to vitamin D binding protein (also known as Gc) isoforms.

Methods

We examined the association between prediagnostic 25(OH)D levels and overall and CRC-specific mortality among participants with CRC within 2 prospective US cohorts. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs.

Results

588 participants with CRC were observed until the date of death or last follow-up (2018), whichever came first. Deficient vs sufficient 25(OH)D concentrations (<30 vs ≥50 nmol/L) were associated with higher overall mortality (HR 2.06; 95% CI 1.34-3.18) but not with CRC-specific mortality (HR 1.51; 95% CI 0.75-3.07). The HRs for overall mortality comparing deficient vs sufficient concentrations were 2.43 (95% CI 1.26-4.70) for those with the Gc1-1 isoform (rs4588 CC) and 1.63 (95% CI 0.88-3.02) for those with the Gc1-2 or Gc2-2 (rs4588 CA or AA) isoform (P for interaction = .54). The HRs for CRC-specific mortality were 1.18 (95% CI 0.27-5.14) for those with the Gc1-1 isoform and 1.41 (95% CI 0.62-3.24) for those with the Gc1-2 or Gc2-2 isoform (P for interaction = .94).

Conclusion

In these 2 US cohorts, we found that lower 25(OH)D levels were associated with higher overall mortality, but this association did not differ by Gc isoforms.

Keywords: vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein, Gc2 isoform, cancer survival, colorectal cancer survival

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer among men and second among women worldwide (1). In the United States, it is the third most common cancer and third leading cause of cancer deaths among both men and women (2).

Vitamin D has been extensively studied as a protective factor against CRC development and progression (3–8). Lower 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels have been associated with higher mortality among patients with CRC (9–12). However, the dose–response relationship is not well characterized. Further, it is unclear whether this association differs depending on functional variants in the vitamin D binding protein (DBP, also known as Gc or group-specific component) gene, which could influence vitamin D bioavailability and metabolism. There are 2 common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in DBP, rs4588 and rs7041, which give rise to 3 predominant haplotypes: Gc1f, Gc1s, and Gc2 (13).

Recently, Gibbs et al examined whether the association of prediagnostic circulating 25(OH)D with survival among participants with CRC from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) and the Cancer Prevention Study-II (CPS-II) cohort studies differed by Gc isoform (14). The multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for CRC-specific mortality associated with deficient (<30 nmol/L) relative to sufficient (≥50 nmol/L) 25(OH)D concentrations were 2.24 (95% CI 1.44-3.49) among cases with the Gc2 isoform (determined by the rs4588 genotype), and 0.94 (95% CI 0.68-1.22) among cases without Gc2 (P for interaction = .0002). The corresponding HRs for all-cause mortality were 1.80 (95% CI 1.24-2.60) among those with Gc2, and 1.12 (95% CI 0.84-1.51) among those without Gc2 (P for interaction = .004).

Our main objective was to assess whether this strong interaction by Gc2 isoform is present in an independent study population. We examined the dose response of prediagnostic 25(OH)D and mortality in participants with CRC as well as the interaction by Gc2 isoform in 2 US cohorts, the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS).

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The NHS was initiated in 1976 among 121 700 US female registered nurses aged 30 to 55 years. Between 1989 and 1990, blood samples were collected from 32 826 NHS participants. The HPFS was established in 1986 among 51 529 US male health professionals aged 40-75 years. Between 1993 and 1995, blood samples were collected from 18 225 HPFS participants. In both cohorts, participants received questionnaires every 2 years to update information on lifestyle factors and medical diagnoses. In both cohorts, a high follow-up rate of more than 90% was achieved. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and those of participating registries as required.

Measurement of Plasma 25(OH)D and DBP Isoforms

Blood samples that were shipped overnight in chilled containers were centrifuged, aliquoted, and stored in liquid nitrogen freezers at ≤−130 °C. Plasma total 25(OH)D was measured in the laboratory of Dr. Bruce Hollis (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) and Heartland Assays (Ames, IA) by radioimmunoassay (15). Plasma DBP was measured at Heartland Assays in 2013 by a monoclonal antibody–based, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems). The mean intra-assay coefficients of variation for total 25(OH)D and DBP were 13.5% and 12.7% respectively (13).

Using the TaqMan OpenArray SNP Genotyping Platform (Applied Biosystems), we genotyped rs4588 among 588 participants with CRC. Details are described elsewhere (13).

Assessments of Covariates, CRC, and Mortality

Cancer stage, tumor site, and year of diagnosis were extracted from medical records. From the questionnaire returned before blood collection, information on body mass index, smoking status, and physical activity was obtained.

Participants who were diagnosed with CRC within 2 years after blood collection were excluded to minimize bias associated with the presence of occult cancer. When incident CRC was identified from self-report or during follow-up of participant deaths, we asked permission to obtain hospital records and pathology reports. Physicians who were blinded to exposure data reviewed medical records, death certificates, or cancer registry data to ascertain the diagnosis of CRC and record information on important tumor characteristics.

Participants were observed until the date of death or last follow-up (June 2018 for NHS; January 2018 for HPFS), whichever came first. Ascertainment of deaths included reporting by family or postal authorities, and interrogation of names of persistent nonrespondents in the National Death Index, which has been shown to capture approximately 98% of deaths (16). The primary outcome was overall mortality, and the secondary outcome was CRC-specific mortality. Study physicians reviewed all available data including medical records to ascertain cause of death.

Statistical Analysis

Individuals with the Gc rs4588 CC, CA, and AA genotypes were classified as having Gc1-1, Gc1-2, and Gc2-2 isoforms, respectively (14) . Participants with a minor allele at rs4588 (A) (rs4588*CA or rs4588*AA genotypes) were defined as having the Gc2 isoform. Participants with no minor allele at rs4588 (A) (rs4588*CC) were defined as not having the Gc2 isoform. For our primary analysis, the effect modification by Gc2 was evaluated using a “dominant inheritance model” given the low frequency of Gc2-2 homozygotes; here, 25(OH)D levels were categorized according to the Institute of Medicine recommendations (deficient, <30 nmol/L; insufficient, 30-<50 nmol/L; sufficient, ≥50 nmol/L). The dominant inheritance model was adapted from Gibbs et al, which compared “No Gc2 (rs4588*CC)” with “Gc2 (rs4588*CA or AA)” (14). For our secondary analysis, we coded Gc2 using a “codominant inheritance model” as we would expect the 25(OH)D-CRC survival association to be stronger with an increasing number of Gc2-encoding alleles; here, 25(OH)D levels were dichotomized at 50 nmol/L to maximize statistical efficiency. The codominant inheritance model was adapted from Gibbs et al, which compared Gc1-1 (rs4588*CC), Gc1-2 (rs4588*CA), and Gc2-2 (rs4588*AA) (14). In addition, we evaluated potential nonlinear associations using the restricted cubic splines (17, 18). Interaction was assessed by entering the cross product of continuous 25(OH)D and Gc2 isoform in the model.

Follow-up time was calculated from CRC diagnosis to death or censoring. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to calculate HRs and 95% CIs for overall mortality and CRC-specific mortality. We stratified by 5-year age groups at diagnosis in the Cox model. We tested for a linear trend using 25(OH)D concentration as a continuous variable in the model. Covariates included were year of diagnosis, sex, tumor site, body mass index, physical activity, smoking status, and stage (14). We additionally adjusted for season of blood collection, which may affect the 25(OH)D levels. We performed subgroup analyses stratified by factors including time from blood collection to CRC diagnosis (≤5 years vs >5 years), calendar year diagnosed (1991-2000 vs 2001-2011), sex, and tumor subsite (proximal colon vs distal colon vs rectum).

For all statistical analyses, a 2-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

There was a total of 634 participants with CRC (372 from the NHS and 262 from the HPFS) and all these participants had information on 25(OH)D levels. Our analysis included 588 participants with CRC who had rs4588 genotype data. Plasma samples were collected at a median of 9.1 years (interquartile range 6.0-13.2) before CRC diagnosis. At baseline, those with higher 25(OH)D concentrations were more likely to be male, physically active, have stage III cancer, have tumor in the proximal colon, and more likely to have blood collected in the summer but less likely to have blood collected in the spring (Table 1). More details on the characteristics of the participants are presented elsewhere (13).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among participants with colorectal cancer by 25(OH)D concentration

| Characteristics | 25(OH)D concentration | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <30 nmol/L (deficient) | 30-<50 nmol/L (insufficient) | ≥50 nmol/L (sufficient) | |

| No. of participants with colorectal cancer | 31 | 115 | 442 |

| Age at blood collection, years, mean (SD) | 61 (7.0) | 61 (7.9) | 61 (8.2) |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 73 (7.2) | 71 (8.3) | 71 (8.4) |

| Time from blood collection to cancer diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 12 (4.3) | 9.4 (4.8) | 10 (4.8) |

| Male, n (%) | 4 (13) | 36 (31) | 208 (47) |

| Ever smokers, n (%) | 21 (68) | 59 (52) | 252 (57) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 26 (4.6) | 28 (5.5) | 26 (3.8) |

| Physical activity, MET-h/wk, mean (SD) | 14 (16) | 20 (34) | 27 (29) |

| Cancer stage, n (%) | |||

| ȃI | 9 (29) | 35 (30) | 115 (26) |

| ȃII | 9 (29) | 33 (29) | 101 (23) |

| ȃIII | 4 (13) | 19 (17) | 98 (22) |

| ȃIV | 5 (16) | 12 (10) | 66 (15) |

| ȃUnknown | 4 (13) | 16 (14) | 62 (14) |

| Year of diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| ȃ1991-2000 | 10 (32) | 59 (51) | 212 (48) |

| ȃ2001-2011 | 21 (68) | 56 (49) | 230 (52) |

| Location of primary tumor, n (%) | |||

| ȃProximal colon | 13 (42) | 51 (44) | 197 (45) |

| ȃDistal colon | 8 (26) | 31 (27) | 121 (27) |

| ȃRectum | 10 (32) | 25 (22) | 96 (22) |

| ȃUnknown | 0 (0) | 8 (7.0) | 28 (6.3) |

| Season of blood collection, n (%) | |||

| ȃSummer (June, July, August) | 4 (13) | 32 (28) | 156 (35) |

| ȃFall (September, October, November) | 5 (16) | 17 (15) | 144 (33) |

| ȃWinter (December, January, February) | 11 (35) | 40 (35) | 57 (13) |

| ȃSpring (March, April, May) | 11 (35) | 26 (23) | 85 (19) |

Abbreviation: MET, metabolic equivalent.

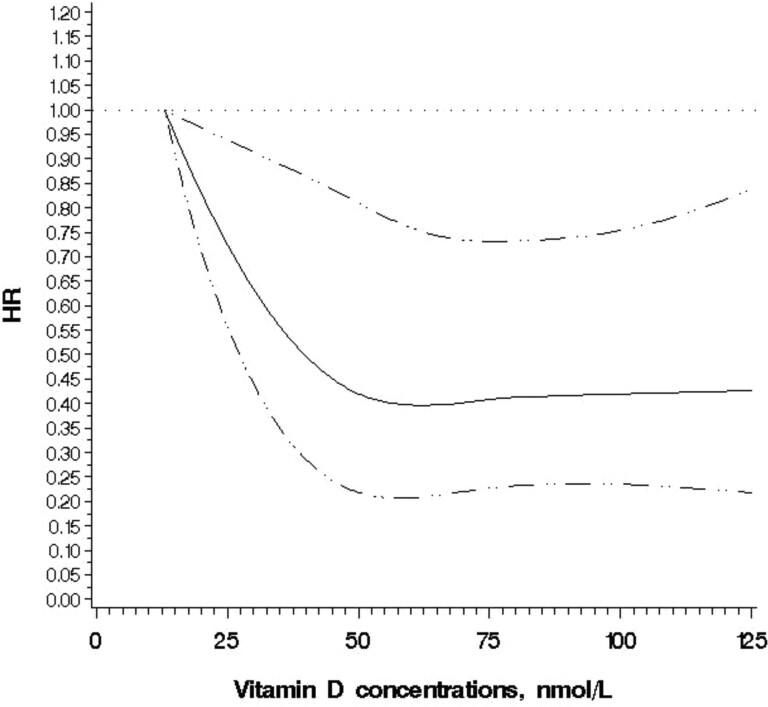

In the multivariable-adjusted analysis, deficient vs sufficient 25(OH)D concentrations (<30 vs ≥50 nmol/L) were associated with higher overall mortality (HR 2.06; 95% CI 1.34-3.18) but not with CRC-specific mortality (HR 1.51; 95% CI 0.75-3.07) (Table 2). Besides the high risk at deficient levels, there was no overall trend. Furthermore, in an additional analysis, compared with those with deficient levels, HR for overall mortality was 0.49 (95% CI 0.32-0.77) for those with levels of ≥50 to 75 nmol/L and 0.47 (95% CI 0.30-0.74) for >75 nmol/L, suggesting that the potential beneficial role of vitamin D concentrations plateaus around 50 nmol/L. A cubic spline regression confirmed that the potential beneficial role of vitamin D flattens around 50 nmol/L (P for nonlinearity = .04; Fig. 1). The results remained largely unchanged when we ran models among all the participants (n = 634) including those without rs4588 genotype information.

Table 2.

Association between 25(OH)D concentration and overall and CRC-specific mortality among participants with CRC, assuming a dominant inheritance model

| 25(OH)D concentration | P for trendb | P for interactionc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 nmol/L (deficient) | 30-<50 nmol/L (insufficient) | ≥50 nmol/L (sufficient) | |||||||||

| Cases | Deaths | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | Deaths | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | Deaths | HR (95% CI)a | |||

| Overall mortality | |||||||||||

| ȃOverall population | 31 | 25 | 2.06 (1.34-3.18) | 115 | 75 | 0.95 (0.72-1.25) | 442 | 293 | 1 | .29 | |

| ȃGc1-1 (rs4588 CC) | 16 | 12 | 2.43 (1.26-4.70) | 44 | 30 | 1.14 (0.74-1.76) | 245 | 158 | 1 | .34 | .54 |

| ȃGc1-2 or Gc2-2 (rs4588 CA or AA) | 15 | 13 | 1.63 (0.88-3.02) | 71 | 45 | 0.77 (0.52-1.12) | 197 | 135 | 1 | .996 | |

| CRC-specific mortality | |||||||||||

| ȃOverall population | 31 | 9 | 1.51 (0.75-3.07) | 115 | 28 | 0.79 (0.51-1.24) | 442 | 148 | 1 | .49 | |

| ȃGc1-1 (rs4588 CC) | 16 | 2 | 1.18 (0.27-5.14) | 44 | 13 | 1.19 (0.61-2.35) | 245 | 72 | 1 | .97 | .94 |

| ȃGc1-2 or Gc2-2 (rs4588 CA or AA) | 15 | 7 | 1.41 (0.62-3.24) | 71 | 15 | 0.53 (0.28-0.98) | 197 | 76 | 1 | .64 | |

Abbreviations: 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CRC, colorectal cancer; HR hazard ratio.

Adjusted for season of blood collection (summer, fall, winter, spring), sex, body mass index (continuous), smoking status (never, ever), physical activity (continuous), cancer stage (I to IV or unknown), location of primary tumor (proximal colon, distal colon, rectum, unknown), and year of diagnosis (continuous).

As a continuous variable.

P for interaction between Gc isoforms (Gc1-1 vs Gc1-2 or Gc2-2) and continuous 25(OH)D concentration.

Figure 1.

Spline regression model for the hazard ratios (HRs) of overall mortality among participants with CRC according to 25(OH)D concentrations. A restricted cubic spline regression model using 4 knots at 25, 50, 75, and 100 nmol/L.

Associations between 25(OH)D concentrations and overall and CRC-specific survival were not different by Gc isoforms. For overall mortality, the HR comparing deficient vs sufficient 25(OH)D concentrations was 2.43 (95% CI 1.26-4.70) for those with Gc1-1 isoform (rs4588 CC) and 1.63 (95% CI 0.88-3.02) for those with Gc1-2 or Gc2-2 (rs4588 CA or AA) isoforms (P for interaction = .54) (Table 2). For CRC-specific mortality, the corresponding HR was 1.18 (95% CI 0.27-5.14) for those with Gc1-1 isoform and 1.41 (95% CI 0.62-3.24) for those with Gc1-2 or Gc2-2 isoforms (P for interaction = .94) (Table 2). In the secondary analysis where we coded Gc2 using a codominant inheritance model, overall mortality for those with nonsufficient concentrations (<50 nmol/L), compared with sufficient (≥50 nmol/L), was not statistically significant for all isoforms but seemingly the strongest for Gc2-2 (rs4588 AA) with 70% higher mortality (P for interaction = .27) (Table 3). For CRC-specific mortality, the corresponding HR was not statistically significant for all types of isoforms (P for interaction = .60) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between 25(OH)D concentration and overall and CRC-specific mortality among participants with CRC, assuming a codominant inheritance model

| 25(OH)D concentration | P for interactionb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 nmol/L (not sufficient) | ≥50 nmol/L (sufficient) | ||||||

| Cases | Deaths | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | Deaths | HR (95% CI)a | ||

| Overall mortality | |||||||

| ȃOverall population | 146 | 100 | 1.10 (0.86-1.42) | 442 | 293 | 1 | |

| ȃGc1-1 (rs4588 CC) | 60 | 42 | 1.33 (0.90-1.96) | 245 | 158 | 1 | .27 |

| ȃGc1-2 (rs4588 CA) | 69 | 45 | 0.82 (0.55-1.21) | 166 | 117 | 1 | |

| ȃGc2-2 (rs4588 AA) | 17 | 13 | 1.70 (0.57-5.13) | 31 | 18 | 1 | |

| CRC-specific mortality | |||||||

| ȃOverall population | 146 | 37 | 0.90 (0.61-1.35) | 442 | 148 | 1 | |

| ȃGc1-1 (rs4588 CC) | 60 | 15 | 1.19 (0.63-2.27) | 245 | 72 | 1 | .60 |

| ȃGc1-2 (rs4588 CA) | 69 | 17 | 0.70 (0.38-1.30) | 166 | 66 | 1 | |

| ȃGc2-2 (rs4588 AA) | 17 | 5 | 0.43 (0.05-3.41) | 31 | 10 | 1 | |

Abbreviations: 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CRC, colorectal cancer; HR hazard ratio.

Adjusted for season of blood collection (summer, fall, winter, spring), sex, body mass index (continuous), smoking status (never, ever), physical activity (continuous), cancer stage (I to IV or unknown), location of primary tumor (proximal colon, distal colon, rectum, unknown), and year of diagnosis (continuous).

P for interaction between Gc isoforms (Gc1-1 vs Gc1-2 vs Gc2-2) and continuous 25(OH)D concentration computed using a likelihood ratio test.

In subgroup analyses for time, sex, and tumor subsite, we see that males, those with ≤5 years since blood collection to CRC diagnosis, and those with tumor in the distal colon may benefit more from sufficient 25(OH)D levels for prognosis, although more samples are warranted for future analyses (Table 4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses for the association between 25(OH)D concentration and overall and CRC-specific mortality among participants with CRC, assuming a dominant inheritance model

| 25(OH)D concentration | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 nmol/L (deficient) | 30-<50 nmol/L (insufficient) | ≥50 nmol/L (sufficient) | |||||||

| Cases | Deaths | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | Deaths | HR (95% CI)a | Cases | Deaths | HR (95% CI)a | |

| Overall mortality | |||||||||

| Time from blood collection to CRC diagnosis | |||||||||

| ≤5 years | 2 | 2 | 7.84 (1.46-42.00) | 29 | 25 | 1.42 (0.77-2.60) | 83 | 61 | |

| ȃ>5 years | 29 | 23 | 1.88 (1.19-2.96) | 86 | 50 | 0.77 (0.55-1.07) | 359 | 232 | 1 |

| Calendar year diagnosed | 1 | ||||||||

| ȃ1991-2000 | 10 | 8 | 1.91 (0.91-4.02) | 59 | 44 | 0.98 (0.66-1.46) | 212 | 148 | |

| ȃ2001-2011 | 21 | 17 | 1.89 (1.09-3.26) | 56 | 31 | 0.81 (0.54-1.24) | 230 | 145 | 1 |

| Sex | 1 | ||||||||

| ȃFemale | 27 | 21 | 2.08 (1.29-3.38) | 79 | 48 | 0.87 (0.61-1.25) | 234 | 144 | |

| ȃMale | 4 | 4 | 3.17 (1.10-9.09) | 36 | 27 | 0.98 (0.63-1.55) | 208 | 149 | 1 |

| Tumor subsiteb | 1 | ||||||||

| ȃProximal colon | 13 | 10 | 1.28 (0.65-2.50) | 51 | 33 | 0.70 (0.46-1.07) | 197 | 146 | |

| ȃDistal colon | 8 | 8 | 4.10 (1.72-9.74) | 31 | 20 | 1.41 (0.77-2.57) | 121 | 67 | 1 |

| ȃRectum | 10 | 7 | 2.47 (1.04-5.87) | 25 | 15 | 1.27 (0.64-2.55) | 96 | 58 | 1 |

| CRC-specific mortality | |||||||||

| Time from blood collection to CRC diagnosis | |||||||||

| ȃ≤5 years | 2 | 1 | 6.08 (0.55-67.04) | 29 | 11 | 1.70 (0.68-4.26) | 83 | 35 | 1 |

| ȃ>5 years | 29 | 8 | 1.31 (0.62-2.79) | 86 | 17 | 0.57 (0.33-1.00) | 359 | 113 | 1 |

| Calendar year diagnosed | |||||||||

| ȃ1991-2000 | 10 | 3 | 1.23 (0.38-4.02) | 59 | 16 | 0.79 (0.42-1.46) | 212 | 82 | 1 |

| ȃ2001-2011 | 21 | 6 | 1.54 (0.62-3.87) | 56 | 12 | 0.82 (0.42-1.61) | 230 | 66 | 1 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| ȃFemale | 27 | 9 | 1.68 (0.82-3.46) | 79 | 21 | 0.72 (0.42-1.22) | 234 | 80 | 1 |

| ȃMale | 4 | 0 | — | 36 | 7 | 0.85 (0.35-2.04) | 208 | 68 | 1 |

| Tumor subsiteb | |||||||||

| ȃProximal colon | 13 | 2 | 0.61 (0.15-2.59) | 51 | 10 | 0.50 (0.24-1.05) | 197 | 76 | 1 |

| ȃDistal colon | 8 | 3 | 2.69 (0.69-10.55) | 31 | 9 | 1.49 (0.61-3.66) | 121 | 35 | 1 |

| ȃRectum | 10 | 4 | 1.58 (0.47-5.33) | 25 | 4 | 0.74 (0.20-2.70) | 96 | 24 | 1 |

Abbreviations: 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CRC, colorectal cancer; HR hazard ratio.

Adjusted for the same set of variables in Table 3 excluding the stratified variable.

Except unknowns.

Discussion

In these 2 US cohorts, among participants with CRC, those with lower prediagnostic 25(OH)D levels had a significantly higher overall mortality. However, we did not observe a significant interaction by Gc isoforms as shown in the previous study by Gibbs et al (14).

Lower 25(OH)D levels have been associated with higher overall mortality among participants with CRC, but the dose response has not been well established (9–12). We had previously observed an inverse association between 25(OH)D levels and total mortality among 304 CRC cases and 123 deaths in the NHS and HPFS up to 2005, but the numbers were too low to examine the dose–response relationship reliably (9). In this article, based on 588 cases and 393 deaths up to 2018, we have confirmed an inverse association. However, the higher risk of mortality was only observed at levels <30 nmol/L, with no difference in risk across levels >30 mol/L. Although the sample size for the subgroup analyses is small, the association was strong for blood samples collected ≤5 years (HR for overall cancer mortality 7.84; 95% CI 1.46-42.00 for deficient vs sufficient 25(OH)D), potentially suggesting reverse causation for this group. In a meta-analysis of circulating 25(OH)D levels and CRC, a linear regression model suggested that a 10 ng/mL (25 nmol/L) increment in 25(OH)D levels was associated with HR of 0.20 (95% CI −0.01 to 0.42) (19). However, the P for linearity test was at an “ambiguous” level (P = .0662), suggesting a possibility of a nonlinear relationship. Our study showed a potential nonlinear relationship between 25(OH)D levels and CRC survival, with the beneficial role of vitamin D being the strongest for deficient levels and plateauing around 50 nmol/L.

Interaction by Gc2 isoforms has been supported not only by Gibbs et al (14) but also by other studies. While there is more evidence on cancer mortality, 1 study that evaluated CRC incidence showed that the association between 25(OH)D levels and CRC may differ by Gc isoform, and those with Gc2-linked vitamin D insufficiency may particularly benefit from adequate 25(OH)D levels for CRC prevention (20). A study in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial found that higher 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with lower overall cancer mortality (HR for overall cancer mortality 0.83; 95% CI 0.70-0.98 for highest vs lowest quintile of 25(OH)D), with the association limited to cases expressing the Gc2 isoform (21). Given their findings, they suggested that individuals with the Gc2 isoform could have better cancer prognosis by maintaining higher 25(OH)D levels.

Individuals with the Gc2 isoform usually have lower concentrations of DBP, 25(OH)D, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D than individuals with the Gc1f and Gc1s isoforms (21–24). It has been proposed that vitamin D sufficiency thresholds may vary by Gc isoforms (23), which may explain why only individuals with the Gc2 isoform appear to gain a cancer survival advantage by maintaining higher 25(OH)D concentrations (21).

Our results were not consistent with those from Gibbs et al (14), where there was a strong, significant interaction by Gc isoform. First, it could be because of the differences in confounders. We adjusted for the same set of covariates that Gibbs et al adjusted for in their analysis, except for additionally adjusting for season of blood draw in our analysis. In a sensitivity analysis excluding season of blood draw, the results remained unchanged. Second, we did not have many participants with deficient levels of 25(OH)D. A Mendelian randomization study suggested a causal relationship between low 25(OH)D concentrations and mortality only among individuals with low vitamin D status defined as <25 nmol/L (25). Here, in our study, we only had 31 out of 588 participants who had deficient levels of <30 nmol/L. Thus, we might not have had enough power to detect an interaction effect with such a small sample size for those with deficient 25(OH)D levels. Third, we used radioimmunoassay methods to measure 25(OH)D. Although liquid chromatography mass spectrometry is considered the most accurate method, radioimmunoassay is still adequate for ranking and relevant in understanding the current data. Almost no available epidemiologic evidence on 25(OH)D to date is based on liquid chromatography mass spectrometry, which should be used for refinement of the precise 25(OH)D levels in future studies.

In conclusion, while lower 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with increased overall mortality among participants with CRC, Gc2 isoforms did not modify the association. Further evaluation of this interaction should focus on populations with low vitamin D status.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge their colleagues in the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution to this study from central cancer registries supported through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and/or the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Central registries may also be supported by state agencies, universities, and cancer centers. Participating central cancer registries include the following: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, Rhode Island, Seattle SEER Registry, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wyoming.

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)D

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- DBP

vitamin D binding protein

- HPFS

Health Professionals Follow-Up Study

- HR

hazard ratio

- NHS

Nurses’ Health Study

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

Contributor Information

Hanseul Kim, Clinical and Translational Epidemiology Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Department of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Chen Yuan, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Long H Nguyen, Clinical and Translational Epidemiology Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Department of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Kimmie Ng, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Edward L Giovannucci, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02115, USA; Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (UM1 CA186107, P01 CA87969, R01 CA49449, U01 CA167552, R01 CA205406) and by the Project P Fund.

Disclosures

K.N. has potential financial conflict of interest as follows: research funding to institution: Pharmavite, Evergrande Group, Janssen, Revolution Medicines; Consulting/Advisory boards: Bayer, GSK, Pfizer.

Data Availability

The details about the data that support the findings of this study are available at: http://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/ and https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/hpfs/for-collaborators/. These data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions. The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feskanich D, Ma J, Fuchs CS, et al. Plasma vitamin D metabolites and risk of colorectal cancer in women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(9):1502‐1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu K, Feskanich D, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Hollis BW, Giovannucci EL. A nested case control study of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and risk of colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(14):1120‐1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(7):684‐696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Otani T, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Tsugane S. Plasma vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: the Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(3):446‐451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jenab M, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Ferrari P, et al. Association between pre-diagnostic circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of colorectal cancer in European populations: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:b5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Woolcott CG, Wilkens LR, Nomura AM, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of colorectal cancer: the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(1):130‐134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Wu K, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):2984‐2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fedirko V, Riboli E, Tjønneland A, et al. Prediagnostic 25-hydroxyvitamin D, VDR and CASR polymorphisms, and survival in patients with colorectal cancer in western European populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(4):582‐593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wesa KM, Segal NH, Cronin AM, et al. Serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D and survival in advanced colorectal cancer: a retrospective analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67(3):424‐430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zgaga L, Theodoratou E, Farrington SM, et al. Plasma vitamin D concentration influences survival outcome after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(23):2430‐2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yuan C, Song M, Zhang Y, et al. Prediagnostic circulating concentrations of vitamin D binding protein and survival among patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(11):2323‐2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gibbs DC, Bostick RM, McCullough ML, et al. Association of prediagnostic vitamin D status with mortality among colorectal cancer patients differs by common, inherited vitamin D-binding protein isoforms. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(10):2725‐2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hollis BW. Quantitation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D by radioimmunoassay using radioiodinated tracers. Methods Enzymol. 1997;282:174‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the national death index and Equifax nationwide death search. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(11):1016‐1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Pollock BG. Regression models in clinical studies: determining relationships between predictors and response. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988; 80(15):1198‐1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8(5):551‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu J, Yuan X, Tao J, Yu N, Wu R, Zhang Y. Association of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with colorectal cancer: an updated meta-analysis. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2018;64(6):432‐444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gibbs DC, Song M, McCullough ML, et al. Association of circulating vitamin D with colorectal cancer Depends on vitamin D-binding protein isoforms: a pooled, nested, case-control study. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020;4(1):pkz083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weinstein SJ, Mondul AM, Layne TM, et al. Prediagnostic serum vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein isoforms, and cancer survival. JNCI Cancer Spectrum. 2022;6(2):pkac019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chun RF. New perspectives on the vitamin D binding protein. Cell Biochem Funct. 2012;30(6):445‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lauridsen AL, Vestergaard P, Hermann AP, et al. Plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D are related to the phenotype of Gc (vitamin D-binding protein): a cross-sectional study on 595 early postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;77(1):15‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sollid ST, Hutchinson MY, Berg V, et al. Effects of vitamin D binding protein phenotypes and vitamin D supplementation on serum total 25(OH)D and directly measured free 25(OH)D. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174(4):445‐452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sofianopoulou E, Kaptoge SK, Afzal S , et al. Estimating dose-response relationships for vitamin D with coronary heart disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality: observational and Mendelian randomisation analyses. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(12):837‐846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The details about the data that support the findings of this study are available at: http://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/ and https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/hpfs/for-collaborators/. These data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions. The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.