Abstract

HBsu, the Bacillus subtilis homolog of the Escherichia coli HU proteins and the major chromosomal protein in vegetative cells of B. subtilis, is present at similar levels in vegetative cells and spores (∼5 × 104 monomers/genome). The level of HBsu in spores was unaffected by the presence or absence of the α/β-type, small acid-soluble proteins (SASP), which are the major chromosomal proteins in spores. In developing forespores, HBsu colocalized with α/β-type SASP on the nucleoid, suggesting that HBsu could modulate α/β-type SASP-mediated properties of spore DNA. Indeed, in vitro studies showed that HBsu altered α/β-type SASP protection of pUC19 from DNase digestion, induced negative DNA supercoiling opposing α/β-type SASP-mediated positive supercoiling, and greatly ameliorated the α/β-type SASP-mediated increase in DNA persistence length. However, HBsu did not significantly interfere with the α/β-type SASP-mediated changes in the UV photochemistry of DNA that explain the heightened resistance of spores to UV radiation. These data strongly support a role for HBsu in modulating the effects of α/β-type SASP on the properties of DNA in the developing and dormant spore.

Dormant spores of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis are relatively resistant to killing by a variety of agents including heat, UV radiation, and oxidizing agents (42). One important component of spore resistance to these agents is the protection of spore DNA from potentially lethal damage, and the major factor in spore DNA protection is the saturation of the spore DNA by α/β-type small acid-soluble proteins (SASP) (42). These α/β-type SASP are produced only in the forespore (42), and their degradation is initiated in the first minute of germination by the germination protease (42). The binding of α/β-type SASP has major effects on DNA properties in vitro (25, 26, 40, 42), and many of these effects appear to be exerted in spores as well (27, 39, 42). In particular, α/β-type SASP binding to DNA both in vitro and in vivo causes marked changes in DNA supercoiling (10, 25) and UV photochemistry (26, 39), and in vitro α/β-type SASP binding increases DNA persistence length tremendously (10). This latter effect is particularly notable, because if the in vitro data are extrapolated to the in vivo situation, this effect of α/β-type SASP on DNA seems potentially inconsistent with the genome fitting into the spore. Consequently, it seems possible, and perhaps even likely, that other proteins may, either directly or indirectly, modulate the effect of α/β-type SASP on DNA properties such as persistence length.

One abundant DNA binding protein that might modulate the effects of α/β-type SASP on DNA properties is HBsu (41, 42). This protein is the homolog of the HU proteins of Escherichia coli which play a role in chromosome structure and function in this organism (32, 34), and this nonspecific DNA binding protein (4) has been shown to reduce DNA persistence length in vitro (14). Studies with vegetative cells of B. subtilis have shown that HBsu is associated with the cell nucleoid (16) and that a mutant lacking the single gene encoding HBsu is inviable (23, 24). This latter result differs from the situation in E. coli, in which a mutant lacking both genes encoding HU is viable but exhibits significant growth defects (8, 15, 47). This difference in the requirement for HU or HBsu in these two species may reflect the presence of a number of additional general chromosome binding proteins in E. coli, including integration host factor and H-NS, homologs of which appear to be absent from B. subtilis (17). In B. subtilis, HBsu appears to be the chromosomal protein present at by far the highest levels in growing cells and is thus a prime candidate for a modulator of the effects of α/β-type SASP on DNA properties in spores. Consequently, in this study we determined the levels of HBsu in the spore and the localization of HBsu in the forespore, and we explored the ability of HBsu to modulate the effects of α/β-type SASP on the DNase digestion, persistence length, supercoiling, and UV photochemistry of DNA in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

PCR was used to generate the coding sequence of the hbs gene, which encodes HBsu. The primers used were 5′-GGCATGCATATGAACAAAACAGAACT-3′ and 5′-CCGGATCCAATTATTTTCCGGCAAC-3′, encoding nucleotides 1 to 17 and 282 to 265 of the hbs sequence (23) and containing extra residues including NdeI and BamHI sites (underlined), respectively. The 298-bp PCR product was cloned into the TA cloning vector (Invitrogen), and the BamHI-NdeI fragment containing the coding sequence was ligated between the BamHI and NdeI sites of pET11a (Novagen), creating pHBsu. The cloned fragment was sequence verified. Bacterial strains used were E. coli BL21(DE3)[pLysS] (43), B. subtilis PS832 (laboratory wild-type strain), B. subtilis PS356 (lacking the genes encoding SASP-α and -β [termed α−β−]) (42), and B. subtilis 618:spoIIIC (46) (obtained from J. Errington, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom).

Protein and DNA.

The B. subtilis minor α/β-type SASP SspC was overexpressed in E. coli and purified as described elsewhere (13). HBsu was purified by a modification of the method of Padas et al. (29). E. coli BL21(DE3)[pLysS] containing pHBsu was grown at 37°C in 3 liters of 2×YT medium (36) containing ampicillin (200 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml) to an optical density of 0.5 at 600 nm and adjusted to 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. After 1.5 h of further incubation, cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 400 ml of cold 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–100 mM NaCl–0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and recentrifuged, and the pellet was frozen and stored at −80°C. The frozen pellet (∼20 g) was resuspended in 30 ml of cold 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–1 mM EDTA–0.1 mM PMSF–20 mM NaCl–10% (vol/vol) glycerol–0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and cells were disrupted by sonication on ice for 10 min. Unless noted, all subsequent steps were performed at 10°C; ammonium sulfate concentrations are those at 0°C. Sonicated cells were centrifuged for 20 min at 27,000 × g followed by 30 min at 48,000 × g, and the supernatant fraction was adjusted to 1.0% streptomycin sulfate and stirred on ice for 20 min. After centrifugation (10 min, 10,000 × g), the supernatant fraction was adjusted to 60% ammonium sulfate and centrifuged at 35,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant fraction was then adjusted to 70% ammonium sulfate and centrifuged again at 35,000 × g for 20 min. The final supernatant fraction was dialyzed in Spectra/Por 3 dialysis tubing against two changes of 14 liters of buffer B (10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.0], 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF). The dialysate was adjusted to 50 μg of RNase A per ml, 10 mM MgCl2, and 50 μg of DNase I per ml, incubated on ice for 1 h, and again dialyzed overnight against 14 liters of buffer B. The dialysate was applied to a 20-ml carboxymethyl-Sepharose CL-6B column equilibrated in buffer B and eluted using a 400-ml 0 to 0.5 M NaCl linear gradient in buffer B, with HBsu eluting at approximately 0.3 M NaCl. The peak fractions identified by Tris-Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (16.5% gel) (37) were pooled and dialyzed overnight against 14 liters of buffer B and concentrated at room temperature by adsorption to a 1-ml carboxymethyl-Sepharose CL-6B column in buffer B, followed by elution with 0.4 M NaCl in buffer B. The concentrated protein was dialyzed against 1 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) to produce the final purified HBsu preparation, which gave a single (>99% of total stained protein) Coomassie blue-stained band of the expected molecular mass of 9.8 kDa upon SDS-PAGE (16.5% gel) (37). The purity of the HBsu protein was also verified by the presence of only a phenylalanine UV absorption peak (11) (data not shown) and by lack of tryptophan fluorescence (data not shown). Gel shift assays (16) using HaeIII-digested φX174 DNA demonstrated that the purified protein retained its DNA binding ability. For topoisomerase assays and polyclonal antiserum production in guinea pigs, HBsu was further purified on a 1-ml Mono S column in buffer C (10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 6.0], 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF) and eluted with a 20-ml 0.2 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient in buffer C to remove small amounts of a contaminating DNase. Fractions from this column were dialyzed separately against 1 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), lyophilized, and resuspended in 1 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5). All HBsu concentrations were measured by the method of Lowry et al. (21) after calibrating the results in this assay with HBsu concentrations determined by amino acid analysis.

Cesium chloride gradient-purified pUC19 was used in analytical procedures (36). [3H]thymidine-labeled pUC19 was prepared as described elsewhere (26).

Quantitation of HBsu and DNA levels.

Lyophilized spores and vegetative cells (optical density of 0.6 to 0.9 at 600 nm) of the wild-type B. subtilis strain (PS832) and a derivative lacking the two major α/β-type SASP (PS356) (42) were prepared from cultures grown in 2×SG medium (28) at 37°C and disrupted in a Wig-L-Bug dental amalgamator; extracts were prepared in 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4)–5 mM EDTA–0.3 mM PMSF as described elsewhere (2). HBsu in the supernatant fraction was quantitated by Western blot analysis by comparison to HBsu protein standards. Aliquots of various supernatant fractions were subjected to PAGE on 16.5% Tris-tricine-SDS-containing gels (37), and proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). Membranes were then incubated with either a 1:103 dilution of rabbit polyclonal antiserum prepared against His6-HBsu (16) (a gift from M. Marahiel, Phillipps Universität, Marburg, Germany) or a 1:104 dilution of guinea pig polyclonal antiserum prepared (Pocono Rabbit Farms, Canadensis, Pa.) against HBsu purified by the method described above. The secondary antibody used was alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig immunoglobulin G (IgG; Sigma), and Lumi-PhosS30 (Boehringer) was used as an immunodetection agent as directed by the manufacturer.

DNA quantitation was by pentose analysis using diphenylamine (38) or using a Fluorescent DNA Quantitation kit (Bio-Rad 170-2480) and a VersaFluor fluorometer.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Cells in which HBsu and α/β-type SASP were to be localized by immunofluorescence were grown in 2×SG medium (28) at 37°C. Fixation and permeabilization of cells was as described elsewhere (12), with the following modifications: (i) fixed cells were resuspended in 300 μl of GTE (50 mM glucose, 25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]); (ii) the methanol and acetone treatments were omitted; and (iii) blocking was with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.4]) (36) for 20 min at room temperature. After blocking, cells were incubated with a 1:2 × 103 dilution of rabbit anti-SspC serum prepared against purified SspC as described previously (6) and a 1:5 × 102 dilution of guinea pig anti-HBsu serum in 2% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and rinsed six times with PBS. Samples were then incubated with a 1:100 dilution of biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes) in 2% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and washed six times with PBS. The final incubation was with a 1:100 dilution of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and indocarbocyanine (Cy3)-conjugated streptavidin (0.2 μg/μl; Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 h at room temperature followed by six more PBS rinses. Slides were washed once with equilibration buffer (Molecular Probes), mounted in Slow-Fade in PBS-glycerol (Molecular Probes), and stored at −20°C. Parallel samples with immunostaining for only HBsu or only α/β-type SASP were also processed, and their analysis ensured that the observed colocalization of HBsu and α/β-type SASP was not an artifact of filter bleedthrough (data not shown). Slides were viewed with a Zeiss Axiovert 100 fluorescence microscope with a 63× 1.25 oil immersion Plan NEOFLUAR lens (Optivar 1.6×) using a standard filter block for visualizing Cy3 and FITC. Exposure times were 2 s for FITC and ranged from 0.3 to 0.5 s for Cy3. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop version 4.0. FITC and Cy3 components of the overlay were aligned by eye, using the colored/black edges created by the Cy3 background staining of the mother cell and the FITC staining of HBsu in the mother cell against the black background.

Analytical procedures.

Analysis of the HBsu or SspC protection of PstI-digested pUC19 against DNase I digestion using agarose gel electrophoresis was done as described elsewhere (40). Assays of the effects of SspC and HBsu on cyclization of linear DNA molecules were carried out with PstI-linearized pUC19 as described elsewhere (10). Topoisomerase assays to examine the effects of SspC and HBsu on plasmid supercoiling were carried out as described previously (25), with a few modifications. Proteins were incubated with 1 μg of cesium chloride gradient-purified plasmid pUC19 in 20 μl of 25 mM Tris-maleate (pH 7.5)–50 mM potassium acetate–10 mM magnesium acetate–1 mM dithiothreitol–50 μg of BSA per ml overnight at 4°C. After addition of 20 U of wheat germ topoisomerase I (Sigma), reactions were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and samples were processed, analyzed by gel electrophoresis on chloroquine-containing agarose gels, and stained with ethidium bromide as described elsewhere (25). Assessment of the effect of SspC and HBsu on the UV photochemistry of DNA was carried out with [3H]thymidine-labeled pUC19 essentially as described elsewhere (26). Briefly, the DNA was exposed to UV radiation in the presence or absence of α/β-type SASP or HBsu, the DNA was acid hydrolyzed, photoproducts were separated by descending paper chromatography, the paper was cut into strips which were counted in a scintillation counter, and individual photoproducts were identified by their migration relative to thymine (26). Unless indicated otherwise, all protein/DNA and protein/protein ratios presented are weight/weight.

RESULTS

Levels of HBsu in growing cells and spores.

The abundance of HU in E. coli (∼30,000 dimers/genome) (32, 34), the association of HBsu with the B. subtilis nucleoid during vegetative growth (16), and the likely role of these proteins in chromosome structure and function make HBsu a prime candidate for a protein which might modulate the effects of α/β-type SASP on DNA properties in B. subtilis spores. However, we first needed to demonstrate that HBsu is indeed present in B. subtilis spores. Consequently, we performed quantitative Western blot analyses with aliquots of extracts from vegetative cells and spores of the wild-type B. subtilis strain (PS832); these analyses demonstrated that B. subtilis vegetative cells and spores had the same amount of HBsu relative to the amount of DNA, with an HBsu/DNA ratio of 0.2 corresponding to about 50,000 monomers/genome (data not shown). We also analyzed extracts from spores lacking the majority of their α/β-type SASP (α−β− spores, strain PS356) and found no significant difference in HBsu levels between the wild-type and α−β− spores (data not shown). The HBsu/DNA ratio in growing cells and spores is very similar to the value reported for E. coli (32, 34) and in combination with the size of the B. subtilis genome (17) and the reported α/β-type SASP/DNA ratio of 2 to 3 in spores (25) gives a calculated α/β-type SASP/HBsu ratio in spores of 10 to 15. The crystal structure of the Bacillus stearothermophilis HU homolog, HBst, indicates that this protein exists as dimers (44, 48), and 9 bp is thought to be covered by a dimer of E. coli HU (4, 5). Assuming conservation of binding traits between the homologs, these figures allow the calculation that there is approximately one HBsu dimer per 170 bp of B. subtilis genomic DNA, giving 5% chromosomal coverage if all HBsu molecules are bound to DNA. In comparison, previous work (25) has indicated that there is sufficient α/β-type SASP in spores to saturate the spore chromosome.

Localization of HBsu in forespores.

HBsu has been localized to the nucleoid in growing cells of B. subtilis (16), and the quantitation discussed above indicated that a significant amount of HBsu is present in spores. However, it is formally possible that HBsu is displaced from the spore nucleoid, possibly by α/β-type SASP, which have been shown to localize to the forespore nucleoid which adopts a ring-like structure (9, 31). Consequently it was essential to determine if HBsu, like α/β-type SASP, is associated with forespore DNA. We used immunofluorescence microscopy to localize both α/β-type SASP and HBsu, examining developing forespores after the time of α/β-type SASP synthesis but before full forespore development, as the impermeability of the mature spore core precludes the use of immunofluorescence to localize components in this compartment. Both the wild type (data not shown) and a spoIIIC strain (618) (46) (Fig. 1) were used for these analyses. While we saw the same localization patterns with both strains, the spoIIIC strain does not complete the full course of forespore development and thus is technically easier to analyze by immunofluorescence microscopy. In agreement with published work (31), we did observe α/β-type SASP ring-like structures of approximately 1 μm in diameter in developing forespores (Fig. 1A). However, not all sporulating cells in these fields contained α/β-type SASP rings, and some cells contained a more globular area of Cy3 staining for α/β-type SASP in the forespore compartment (Fig. 1A). Note that the weak Cy3 (anti-α/β-type SASP) staining of the mother cell compartment in this experiment is a nonspecific reaction, as it was present on slides prepared identically except for the omission of the primary anti-α/β-type SASP antiserum (data not shown). Localization of HBsu in the forespore both in the wild type (PS832) (data not shown) and in the spoIIIC strain (Fig. 1) showed HBsu to be also present in ring-like structures in some cells (Fig. 1B). The location of these HBsu ring-like structures overlapped significantly with the location of the α/β-type SASP ring-like structures in the forespores (Fig. 1C), and HBsu was also present in the α/β-type SASP globular areas (Fig. 1, 1 and C1). In the samples from which the cells shown in Fig. 1 were chosen, 30 to 40% of cells (n = 249) had clearly discernible rings or globular areas of FITC (HBsu) or Cy3 (α/β-type SASP) staining. In the majority (65 to 80%) of these rings or globular areas, staining for both HBsu and α/β-type SASP was observed and colocalized. We also noted that the Cy3 (α/β-type SASP) rings were usually complete rings (75% of Cy3-stained rings) while the FITC (HBsu) ring-like structures were often incomplete rings (80% of FITC-stained rings) with polar-facing gaps (97% of incomplete rings). It is not clear if these incomplete rings are precursors to complete rings or are the final localization pattern for HBsu. Since HBsu knockouts are inviable (23, 24), we used an alternate negative control to ensure the specificity of our anti-HBsu antiserum by including purified HBsu in the primary antibody step in the staining procedure. With slides prepared in this manner, FITC staining (HBsu) dropped to a very low level overall and no HBsu ring-like structures or globular structures could be discerned; however, this control treatment did not interfere with the detection of α/β-type SASP ring-like or globular structures in the forespores by Cy3 fluorescence (data not shown). Since previous work has shown that α/β-type SASP are on the forespore nucleoid (9, 31), the data given above indicate that HBsu is also located on the forespore nucleoid and thus likely also on the dormant spore nucleoid. While it appears that HBsu and α/β-type SASP are not distributed homogeneously on the forespore chromosome (note that the color of the merged images in Fig. 1C is not uniform), since both proteins are on the forespore nucleoid, HBsu could modulate the effects of α/β-type SASP on DNA properties in spores. Because a strain lacking HBsu is inviable (23, 24), we could not analyze the effects of the loss of HBsu on spore DNA properties in vivo and instead examined the effects of HBsu on α/β-type SASP-DNA interactions in vitro.

FIG. 1.

Localization of α/β-type SASP and HBsu in developing spores by immunofluorescence. Rows 1 to 3 show three fields containing sporulating spoIIIC cells (strain 618 [46]) grown, fixed, and prepared for immunofluorescent localization as described in Materials and Methods. The same three fields are shown in panels A to C. Unlabeled arrows indicate the locations of ring-like structures in forespore compartments, and arrows labeled “a” indicate positions of more globular structures in forespore compartments. Column A shows α/β-type SASP localized using a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody; column B shows HBsu localized using a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody; column C is an overlay of columns A and column B; areas of colocalization are yellow-orange. Bar, 5μm.

HBsu modulates SspC protection of DNA from DNase digestion.

Previous work has shown that α/β-type SASP protect DNA from DNase digestion and that DNase digestion of α/β-type SASP-bound plasmid DNA gives a characteristic pattern of protected fragments (40). Consequently, we examined the effects of HBsu on the DNase protection pattern given by SspC, a minor α/β-type SASP that exhibits the same properties as major α/β-type SASP in vivo and in vitro (45). In this analysis and in those following, we generally used higher than physiological α/β-type SASP/DNA ratios to ensure saturation of the α/β-type SASP effect in each assay to allow analysis of the effects of HBsu on the α/β-type SASP-saturated DNA. These elevated α/β-type SASP/DNA ratios were needed to ensure saturation of the DNA in vitro because of the relatively weak binding between α/β-type SASP and DNA (25).

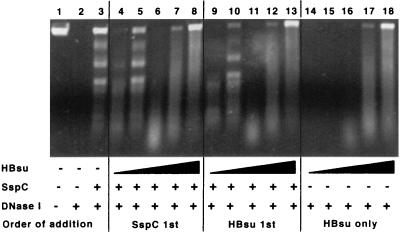

DNase treatment of PstI-linearized pUC19 complexed with SspC (SspC/DNA = 12) (Fig. 2, lane 3) resulted in the protection of distinct bands as reported previously (40), while complexes containing HBsu alone gave a much less distinct DNase protection pattern (Fig. 2, lanes 14 to 18). At a constant concentration of SspC, addition of increasing amounts of HBsu (Fig. 2, lanes 4 to 8) reproducibly modified the DNase protection pattern even at an α/β-type SASP/HBsu ratio of 12 (Fig. 2, lane 4). This latter value is within the estimated in vivo ratio of α/β-type SASP/HBsu of 10 to 15; hence at a physiological α/β-type SASP/HBsu ratio, HBsu can modify the DNase protection pattern given by SspC. As more HBsu was added (Fig. 2, lanes 5 to 8), the pattern initially resembled that in reactions with SspC only (Fig. 2, compare lanes 3 and 5) and then changed to that seen in reactions with HBsu alone (Fig. 2, compare lanes 6 to 8 and 16 to 18). While we cannot explain the return to an SspC-only-like pattern at a 6:1 ratio of SspC to HBsu, the pattern recurred when the experiment was repeated. Note that this effect is seen at SspC/HBsu ratios of 1 to 3 and HBsu/DNA ratios of 4 to 12; at these latter ratios, the DNA can potentially be saturated by HBsu. The fact that saturating levels of HBsu gave a DNase protection pattern identical to that given by saturating levels of HBsu and SspC (Fig. 2, compare lanes 7 and 12 with lane 17 and lanes 8 and 13 with lane 18) suggests that HBsu can displace SspC from DNA or that the HBsu effect on DNase protection is dominant when both proteins are bound.

FIG. 2.

Influence of HBsu on DNase protection by SspC. DNase protection experiments were performed with 0.5 μg of PstI-digested pUC19. The samples contained the following additions: lanes 3 to 13, 6 μg of SspC; lanes 4, 9, and 14, 0.5 μg of HBsu; lanes 5, 10, and 15, 1 μg of HBsu; lanes 6, 11, and 16, 2 μg of HBsu; lanes 7, 12, and 17, 4 μg of HBsu; and lanes 8, 13, and 18, 6 μg of HBsu. In lanes 4 to 8, SspC and DNA were incubated for 20 min before the addition of HBsu. In lanes 9 to 13, HBsu and DNA were incubated for 20 min before the addition of SspC.

Since HBsu is bound to DNA during vegetative growth (16) whereas α/β-type SASP are produced only during sporulation (42), we examined whether the presence of HBsu on the DNA before the addition of SspC had any effect on subsequent DNase digestion. However, reactions in which HBsu was incubated with DNA before the addition of SspC (Fig. 2, lanes 9 to 13) gave the same DNase protection patterns as reactions in which SspC was incubated with DNA prior to the addition of HBsu (Fig. 2, lanes 4 to 8). These data indicate that order of addition has little effect on the DNase protection pattern produced in the presence of HBsu and α/β-type SASP.

HBsu modulation of SspC effects on DNA supercoiling.

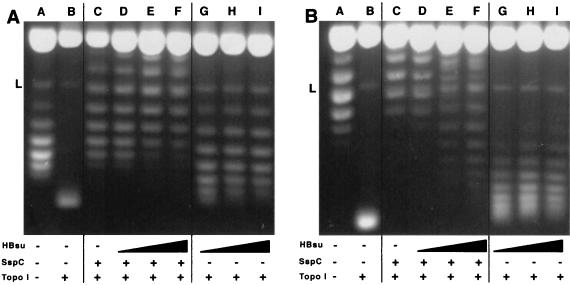

Continuing our investigation of the ability of HBsu to modulate the effects of SspC on DNA, we examined the combined effects of these proteins on DNA supercoiling using topoisomerase I treatment to trap supercoils induced by protein binding to covalently closed plasmid DNA (Fig. 3). Products from reactions containing SspC showed reduced migration during electrophoresis on agarose gels with increased chloroquine concentration (compare lanes C in Fig. 3A and B), consistent with the negative supercoiling induced by SspC seen in a similar assay in an earlier report (25). Since the deproteinization step following the topoisomerase treatment causes the plasmids to exhibit supercoiling of sign opposite that introduced by the protein, this result indicates that positive supercoiling is induced by SspC. In contrast, HBsu-containing reactions migrated further on agarose gels with increased chloroquine concentration (Fig. 3A and B, lanes G to I), indicating that HBsu added negative supercoils to the plasmid substrate, causing positive supercoils to be trapped in this assay. This is consistent with the effects of E. coli HU on DNA supercoiling (35) and thus HBsu and SspC introduce supercoiling of opposite sign. When both proteins were present in the same reaction (Fig. 3, lanes D to F), DNA species with supercoiling intermediate to that in reactions containing the individual proteins were produced (Fig. 3B, compare lanes E and F with lanes C, H, and I), demonstrating that HBsu and SspC can be bound to the same piece of DNA. Note also that DNAs with the intermediate levels of supercoiling (Fig. 3A, lanes E and F) are formed under conditions (SspC/HBsu) very similar to those used in the DNase protection assay (Fig. 2, lanes 6 and 7) where these conditions did not produce an intermediate DNase protection pattern; hence the HBsu-like DNase protection pattern produced by saturating levels of HBsu and SspC likely represents the dominance of the HBsu effect in this assay rather than complete displacement of SspC by HBsu. However, the protein/DNA ratios in the DNase protection assay are double those in the topoisomerase assay, leaving open the possibility that the conditions differ enough to affect which protein dominates DNA binding. Because of the somewhat limited resolution of the topoisomerase assay, it was necessary to use an α/β-type SASP/HBsu ratio of 3 to observe an effect of HBsu on SspC-induced supercoiling. While this value is significantly lower than the α/β-type SASP/HBsu ratio in vivo, this result does again demonstrate the ability of HBsu to modulate the effects of α/β-type SASP on DNA.

FIG. 3.

Effects of HBsu and SspC on DNA supercoiling, determined on chloroquine (2 [A] or 4 [B] μg/ml)-containing agarose gels with products of topoisomerase I (Topo I) assays stained with ethidium bromide after electrophoresis. Half of each reaction was run in corresponding lanes of each gel. Untreated substrate pUC19 was loaded in lane A. All reactions contained 1 μg of pUC19; reactions in lanes C to F contained 6 μg of SspC; reactions in lanes D and G, E and H, and F and I contained 1, 2, and 3 μg of HBsu, respectively. The strongly staining band at the top of each lane is nicked circular pUC19. The band labeled L is likely linear pUC19.

HBsu effects on DNA persistence length in the presence and absence of SspC.

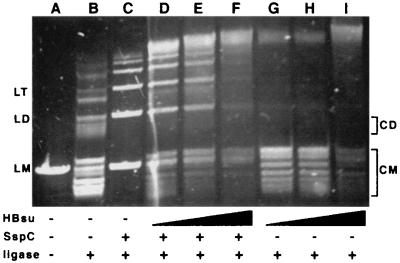

Having colocalized HBsu and SspC to the forespore nucleoid and demonstrated the ability of these proteins to bind to the same piece of DNA in vitro, we performed circularization assays to investigate whether HBsu can modulate the persistence length of DNA complexed with SspC. In these assays the persistence length/rigidity of a linear piece of DNA, here pUC19, is measured by adding T4 DNA ligase. Ligation products in the absence of SspC or HBsu are predominantly circular, with only small amounts of linear multimers (Fig. 4, lane B), as found previously (10). However, when SspC is added to this reaction, linear products dominate (Fig. 4, lane C), again as found previously (10), indicating that the presence of SspC has increased the persistence length of the DNA. Consistent with work using E. coli HU (14), HBsu alone has an effect opposite to that of SspC (Fig. 4, lanes G to I), as HBsu addition resulted in formation almost exclusively of circular monomers of varying superhelicity. This indicates that HBsu reduces the persistence length of DNA. When reactions contained both SspC and HBsu (Fig. 4, lanes D to F), the result was a reduction in formation of linear multimers relative to reactions containing only SspC. This indicates that HBsu can ameliorate the effect of α/β-type SASP on DNA persistence length. This reduction of persistence length was observed not only at SspC/HBsu ratios of 2 to 4 (Fig. 4, lane E) (SspC/DNA = 6) but also at SspC/HBsu ratios of 4 to 16 (data not shown). Thus, the effects of HBsu on DNA persistence length are observed within the estimated in vivo α/β-type SASP/HBsu ratio of 10 to 15. Cyclization assays using fragments of approximately 325, 850, and 1,300 bp also demonstrated the ability of HBsu to reduce the persistence length of these fragments in the presence of SspC (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effect of HBsu on DNA persistence length. PstI-linearized pUC19 (0.5 μg) (lane A) was treated with T4 DNA ligase in the presence or absence of SspC (3 μg) and 0.75 (lanes D and G), 1 (lanes E and H), and 1.5 (lanes F and I) μg of HBsu. Linear products are labeled LM (linear monomer), LD (linear dimer), and LT (linear trimer). Circular products run above and below the linear products and are labeled CM (circular monomer) and CD (circular dimer).

Effect of HBsu on DNA photochemistry.

HBsu modulation of the influence of α/β-type SASP on DNA persistence length certainly contributes to the understanding of the packaging of the α/β-type SASP-bound chromosome in the spore. One important consequence of the binding of α/β-type SASP to spore DNA is a change in the UV photochemistry of the DNA, one factor in the elevated UV resistance of spores (26, 39). The α/β-type SASP-mediated change in the UV photochemistry of DNA results in the production of the spore photoproduct, a thyminyl-thymine adduct, which is repaired in a relatively error-free process early in spore germination instead of the production of cyclobutane-type thymine-thymine (T-T) dimers which are subject to error-prone repair (42). Having found that HBsu modulates the effects of α/β-type SASP on several other DNA properties, we also considered whether HBsu might modulate the effects of α/β-type SASP on DNA photochemistry. To address this issue, we exposed [3H]thymidine-labeled pUC19 to UV radiation in the presence or absence of SspC and/or HBsu and determined the amount and type of photoproducts formed (Table 1). The major UV photoproducts formed were a cyclobutane-type T-T dimer with DNA alone and the spore photoproduct in the presence of SspC (SspC/DNA = 8), consistent with earlier work (26, 39). HBsu appears to have little effect on the UV photochemistry of DNA, as the major photoproduct upon irradiation of DNA plus HBsu was again the cyclobutane-type T-T dimer. Similarly, when HBsu and SspC were present with DNA at an SspC/HBsu ratio of 20 (HBsu/DNA = 0.4; note that this latter value is twofold higher than the HBsu/DNA ratio in spores), the major photoproduct remained the spore photoproduct. Thus, HBsu at physiological levels relative to α/β-type SASP and DNA did not interfere significantly with the change in UV photochemistry induced by the binding of α/β-type SASP to spore DNA. Increasing the amount of HBsu (SspC/HBsu ≤ 10; HBsu/DNA ≥ 0.8), did result in an increasing level of thymine dimer among the photoproducts, approaching the levels seen in reactions without SspC (data not shown), consistent with HBsu outcompeting SspC for DNA binding or with the effect of HBsu being dominant with both proteins bound. Samples (SspC/HBsu = 20, HBsu/DNA = 0.4) irradiated at pH 6.5 (the likely pH within the spore core [22]) or with less HBsu (SspC/HBsu = 40, HBsu/DNA = 0.2) gave a distribution of photoproducts essentially identical to that shown in Table 1 for irradiation of DNA with SspC alone (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Effects of HBsu on DNA photochemistrya

| Sample | % of total thymine

|

|

|---|---|---|

| T-T dimersb | Spore photoproduct | |

| DNA only | 6.0 | 1.0c |

| DNA + SspCd | 0.4 | 4.3 |

| DNA + SspC + HBsue | 0.8 | 4.1 |

| DNA + HBsuf | 5.6 | 1.4c |

[3H]thymidine-labeled pUC19 with or without SspC or HBsu was exposed to 15 min of UV radiation (2.7 J/cm2), and photoproducts were identified after acid hydrolysis of the DNA by descending paper chromatography as described in Materials and Methods.

Cyclobutane-type dimers.

This radioactivity represents a variety of nonspecific photoproducts formed at the high UV doses used in these experiments.

SspC/DNA = 8.

SspC/DNA = 8; SspC/HBsu = 20.

HBsu/DNA = 0.4.

DISCUSSION

Members of the HU family of DNA binding proteins are thought to play an important role in maintenance of the structure and/or stability of the bacterial chromosome. While the specific role played by these proteins has proven difficult to discern, a host of DNA-related activities in which these proteins can function have been identified. These include roles in transcription (1), DNA replication (7, 49), recombination (19), bacteriophage Mu transposition (15, 29), and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DNA inversion (29). In this report we have shown that B. subtilis HBsu also likely modulates the effects of α/β-type SASP on the structure of chromosomal DNA in the developing and dormant spore of B. subtilis.

We have found that in B. subtilis there are approximately 5 × 104 monomers of HBsu per genome, a level that is unchanged in the presence or absence of the α/β-type SASP. This level is clearly subsaturating, in contrast to the level of α/β-type SASP, which is sufficient to saturate the spore DNA, given that a single α/β-type SASP covers approximately 5 bp (42). Except for the supercoiling studies which are somewhat limited in their resolution, the various experiments reported in this work demonstrated effects consistent with HBsu modulating (DNase protection and circularization) or not modulating (photochemistry) the effects of α/β-type SASP on DNA at physiological α/β-type SASP/HBsu ratios. However, because of the higher than physiological levels of SspC needed to saturate the DNA in the various assays, a higher than physiological ratio amount of HBsu relative to DNA was used in some experiments in order to maintain a physiological SspC/HBsu value.

We supply support for the hypothesis that HBsu is bound to the spore chromosome in several ways: (i) HBsu is able to outcompete SspC for DNA binding or produces a dominant effect in DNase protection and UV photochemistry assays; (ii) HBsu and α/β-type SASP can be bound to the same piece of DNA despite cooperative binding of each protein (10, 30, 33) as shown by DNase protection and supercoiling assays; and (iii) immunofluorescence studies localize HBsu to the regions, whether rings or globular regions, to which α/β-type SASP localize (31). Since previous work has shown that α/β-type SASP are on the forespore DNA (9, 31), these data indicate that both HBsu and α/β-type SASP localize there. The impermeability of the mature spore core hinders attempts at localization of proteins (e.g., HBsu and α/β-type SASP) in this compartment, and so we have analyzed sporulating cells after the synthesis of α/β-type SASP in order to refute the hypothesis that α/β-type SASP binding displaces HBsu from the chromosome in the spore.

Given the binding of both α/β-type SASP and HBsu to the chromosome and to the same piece of DNA in vitro, we have looked for a close association between these two proteins in vitro in the presence and absence of DNA. However, despite varying many conditions and cross-linking agents, we have been unable to demonstrate a significant level of SspC-HBsu heterodimer formation (data not shown). The reasons for this negative result are not clear; possibilities include that cross-linkable residues are not available at the HBsu-SspC interface or that the two proteins bind preferentially in different DNA regions with α/β-type SASP in G-C rich areas and HBsu elsewhere. Possible differential binding to DNA regions by these two proteins is consistent with the discrete bands seen in the DNase protection pattern given by SspC, which appears to be a result of the preference of α/β-type SASP for binding to relatively G-C rich stretches (10, 40), while the more diffuse pattern given by HBsu is consistent with reports that HBsu has little sequence preference (4). However, it is certainly reasonable that both HBsu and α/β-type SASP are bound to the DNA at the same time, as the reported KD values for E. coli HU-DNA complexes are 10−6 to 10−7 (5, 20, 30) whereas the corresponding values for SspC-DNA complexes are 10−5 to 10−7 (25; C. Hayes, Z. Peng, and P. Setlow, unpublished data). Additionally, binding of the two proteins in the same stretches of the DNA is not out of the question; although definitive structural information is not available for the complexes formed with DNA by either protein, E. coli HU likely interacts with the minor groove (18) whereas α/β-type SASP are thought to interact primarily with the DNA backbone (40).

One potentially important role for HBsu in the spore is the reduction of the α/β-type SASP-mediated increase in persistence length of DNA which on its own would prevent the chromosome from fitting in the spore (although obviously DNA substrates in in vitro tests of persistence length do not approach chromosome size). Reduction of the α/β-type SASP-mediated increase in persistence length by HBsu could address this potential problem. One possible model has regions of DNA saturated with α/β-type SASP interspersed with regions of DNA bound to HBsu, thereby directing spore genome packaging. However, genome packaging may also be accomplished by intermingled α/β-type SASP and HBsu-bound regions.

The simplistic model in which the forespore chromosome is packed in sequential circles within the visualized chromosomal ring would require approximately 450 rounds, each of which would employ approximately 9 kb. Given the ability of physiological HBsu/DNA ratios to allow circularization of the 2.7-kb α/β-type SASP-stiffened DNA molecule, HBsu binding could certainly allow 360°C of bend in a section of the α/β-type SASP-stiffened chromosome over three times that size. The large side-by-side ring-like aggregates seen on electron microscopy of SspC and pUC19 in vitro at the higher than physiological α/β-type SASP/DNA ratio of 10 (10) might also indicate how the α/β-type SASP-bound chromosome is packaged into rings in the forespore. However, the biological relevance of these side-by-side aggregates has not been determined.

This work has focused on HBsu as the main potential modulator of α/β-type SASP–DNA interaction because of the known abundance of HBsu in B. subtilis and because genes encoding homologs of other major DNA binding proteins of E. coli (integration host factor and H-NS) are absent from the B. subtilis genome (17). However, it is certainly possible that in B. subtilis there are abundant but as yet unknown DNA binding proteins, that a less abundant DNA binding protein is present, or that there are minor proteins unique to spores (3) that may bind to the spore chromosome and modulate the effects of α/β-type SASP on spore DNA properties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. Hla and L. Klobutcher for use of fluorescence microscopes, M. Marahiel for rabbit anti-HBsu antiserum, C. Hayes for early SspC preparations, J. Errington for strain 618, and G. Korza, L. Pederson, and B. Setlow for advice and assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM19698 (P.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aki T, Adhya S. Repressor induced site-specific binding of HU for transcriptional regulation. EMBO J. 1997;16:3666–3674. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagyan I, Noback M, Bron S, Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Characterization of yhcN, a new forespore-specific gene of Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1998;212:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00172-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagyan I, Setlow B, Setlow P. New small, acid-soluble proteins unique to spores of Bacillus subtilis: identification of the coding genes and regulation and function of two of these genes. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6704–6712. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6704-6712.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnefoy E, Rouviere-Yaniv J. HU and IHF, two homologous histone-like proteins of Escherichia coli, form different protein-DNA complexes with short DNA fragments. EMBO J. 1991;10:687–696. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07998.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cann J R, Pfenninger O, Pettijohn D E. Theory of the mobility-shift assay of nonspecific protein-DNA complexes governed by conditional probabilities: the HU:DNA complex. Electrophoresis. 1995;16:881–887. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501601148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connors M J, Setlow P. Cloning of a small, acid-soluble spore protein gene from Bacillus subtilis and determination of its complete nucleotide sequence. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:333–339. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.333-339.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon N E, Kornberg A. Protein HU in the enzymatic replication of the chromosomal origin of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:424–428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.2.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dri A-M, Rouvier-Yaniv J, Moreau P L. Inhibition of cell division in hupA hupB mutant bacteria lacking HU protein. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2852–2863. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2852-2863.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francesconi S C, MacAlister T J, Setlow B, Setlow P. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of small, acid-soluble spore proteins in sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5963–5967. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5963-5967.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith J, Makhov A, Santiago-Lara L, Setlow P. Electron microscopic studies of the interaction between a Bacillus subtilis α/β-type small, acid-soluble spore protein with DNA: protein binding is cooperative, stiffens the DNA, and induces negative supercoiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8224–8228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groch N, Schindelin H, Scholtz A S, Hahn U, Heinemann U. Determination of DNA-binding parameters for the Bacillus subtilis histone-like HBsu protein through introduction of fluorophores by site-directed mutagenesis of a synthetic gene. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:677–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harry E J, Pogliano K, Losick R. Use of immunofluorescence to visualize cell-specific gene expression during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3386–3393. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3386-3393.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes C S, Setlow P. Analysis of deamidation of small, acid-soluble spore proteins from Bacillus subtilis in vitro and in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6020–6027. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6020-6027.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodges-Garcia Y, Hagerman P J, Pettijohn D E. DNA ring closure mediated by protein HU. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14621–14623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huisman O, Faelen M, Girard D, Jaffe A, Toussaint A, Rouviere-Yaniv J. Multiple defects in Escherichia coli mutants lacking HU protein. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3704–3712. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3704-3712.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohler P, Marahiel M A. Association of the histone-like protein HBsu with the nucleoid of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2060–2064. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.2060-2064.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavoie B, Shaw G S, Millner A, Chaconas G. Anatomy of a flexer-DNA complex inside a higher-order transposition intermediate. Cell. 1996;85:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li S, Waters R. Escherichia coli strains lacking protein HU are UV sensitive due to a role for HU in homologous recombination. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3750–3756. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3750-3756.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Losso M A, Pawlik R T, Canonaco M A, Gualerzi C O. Proteins from the prokaryotic nucleoid. A protein-protein cross-linking study on the quaternary structure of Escherichia coli DNA-binding protein NS (HU) Eur J Biochem. 1986;155:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magill N G, Cowan A E, Leyva-Vazquez M A, Brown M, Koppel D E, et al. Analysis of the relationship between the decrease in pH and accumulation of 3-phosphoglyceric acid in developing forespores of Bacillus species. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2204–2210. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2204-2210.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Micka B, Groch N, Heinemann U, Marahiel M A. Molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis gene encoding the DNA-binding protein HBsu. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3191–3198. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.10.3191-3198.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Micka B, Marahiel M A. The DNA-binding protein HBsu is essential for normal growth and development in Bacillus subtilis. Biochimie. 1992;74:641–650. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicholson W L, Setlow B, Setlow P. Binding of DNA in vitro by a small, acid-soluble spore protein from Bacillus subtilis and the effect of this binding on DNA topology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6900–6906. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6900-6906.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholson W L, Setlow B, Setlow P. Ultraviolet irradiation of DNA complexed with α/β-type small, acid-soluble proteins from spores of Bacillus or Clostridium species makes spore photoproduct but not thymine dimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8288–8292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson W L, Setlow P. Dramatic increase in negative superhelicity of plasmid DNA in the forespore compartment of sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:7–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.7-14.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholson W L, Setlow P. Sporulation, germination and outgrowth. In: Harwood C R, Cutting S M, editors. Molecular biology methods for Bacillus. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1990. pp. 391–450. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Padas P M, Wilson K S, Vorgias C E. The DNA-binding protein HU from mesophilic and thermophilic bacilli: gene cloning, overproduction and purification. Gene. 1992;117:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90487-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinson V, Takahashi M, Rouviere-Yaniv J. Differential binding of the Escherichia coli HU, homodimeric forms and heterodimeric form to linear, gapped and cruciform DNA. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:485–497. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pogliano K, Harry E, Losick R. Visualization of the subcellular location of sporulation proteins in Bacillus subtilis using immunofluorescence microscopy. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:459–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rouviere-Yaniv J. Localization of the HU protein on the Escherichia coli nucleoid. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1978;42:439–447. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1978.042.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rouviere-Yaniv J, Gros F. Characterization of a novel, low-molecular-weight DNA-binding protein from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rouviere-Yaniv J, Kjeldgaard N O. Native Escherichia coli HU protein is a heterotypic dimer. FEBS Lett. 1979;106:297–300. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)80518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rouviere-Yaniv J, Yaniv M. E. coli DNA binding protein HU forms nucleosome-like structure with circular double-stranded DNA. Cell. 1979;17:265–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schagger H, Von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider W C. Determination of nucleic acids in tissues by pentose analysis. Methods Enzymol. 1957;3:680–684. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Setlow B, Setlow P. Thymine-containing dimers as well as spore photoproducts are found in ultraviolet-irradiated Bacillus subtilis spores that lack small acid-soluble proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:421–423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Setlow B, Sun D, Setlow P. Interaction between DNA and α/β-type small, acid-soluble spore proteins: a new class of DNA-binding protein. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2312–2322. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2312-2322.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Setlow P. Changes in the forespore chromosome structure during sporulation in Bacillus species. Semin Dev Biol. 1991;2:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Setlow P. Mechanisms for the prevention of damage to DNA in spores of Bacillus species. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:29–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka I, Appelt K, Dijk J, White S W, Wilson K S. 3-A resolution structure of a protein with histone-like properties in prokaryotes. Nature. 1984;310:376–381. doi: 10.1038/310376a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tovar-Rojo F, Setlow P. Effects of mutant small, acid-soluble spore proteins from Bacillus subtilis on DNA in vivo and in vitro. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4827–4835. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4827-4835.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner S M, Mandelstam J, Errington J. Use of a lacZ gene fusion to determine the dependence pattern of sporulation operon spoIIIC in spo mutants of Bacillus subtilis: a branched pathway of expression of sporulation operons. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:2995–3003. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-11-2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wada M, Ogawa T, Okazaki T, Imamoto F. Construction and characterization of the deletion mutant of hupA and hupB genes in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1988;204:581–591. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White S W, Appelt K, Wilson K S, Tanaka I. A protein structural motif that bends DNA. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1989;5:281–288. doi: 10.1002/prot.340050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yasukawa H, Ozaki E, Nakahama K, Masamune Y. HU protein binding to the replication origin of the rolling-circle plasmid pKYM enhances DNA replication. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:548–554. doi: 10.1007/s004380050450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]