Abstract

The incidence of liver cancer, the third cause of cancer-associated death, has been growing, worldwide. The increasing trend of liver cancer incidence and mortality indicates the inefficiency of current therapeutic approaches, especially anticancer chemotherapy. Owing to the promising anticancer potential of Thiosemicarbazone (TSC) complexes, this work was conducted to synthesize titanium oxide nanoparticles conjugated with TSC through glutamine functionalization (TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs) and characterize their anticancer mechanism in HepG2 liver cancer cells. Physicochemical analyses of the synthesized particles, including FT-IR, XRD, SEM, TEM, Zeta potential and DLS, and EDS-mapping confirmed the proper synthesis and conjugation of TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs. The synthesized NPs were almost spherical, with a size range of 10–80 nm, a zeta potential of − 57.8 mV, a hydrodynamic size of 127 nm, and without impurities. Investigation of the cytotoxic effect of TiO2@Gln-TSC in HepG2 and HEK293 human normal cells indicated significantly higher toxicity in cancer cells (IC50 = 75 µg/mL) than normal cells (IC50 = 210 µg/mL). Flow cytometry analysis of TiO2@Gln-TSC treated and control cells showed that the population of apoptotic cells considerably increased from 2.8 to 27.3% after treatment with the NPs. Moreover, 34.1% of the TiO2@Gln-TSC treated cells were mainly arrested at the sub-G1 phase of the cell cycle, which was significantly greater than control cells (8.4%). The Hoechst staining assay showed considerable nuclear damage, including chromatin fragmentation and the appearance of apoptotic bodies. This work introduced TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs as a promising anticancer compound that could combat liver cancer cells through apoptosis induction.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Liver cancer, Titanium oxide, Thiosemicarbazone

Introduction

In recent years, the burden of cancer incidence and mortality has been rapidly growing, worldwide and treating cancer is considered a main human health challenge (Sung et al. 2021). With more than annual 900,000 new cases and 830,000 new deaths, liver cancer ranks as the sixth most prevalent and third cause of cancer death, worldwide (Sung et al. 2021). Several risk factors, including chronic viral hepatitis, aflatoxin, alcohol intake, and excessive body weight, are considered the major risk factors for liver cancer (London and McGlynn 2006). Late detection and inefficiency of current treatments, especially for late-diagnosed cases, are two critical factors in the high mortality of liver cancer. Therefore, finding novel therapeutic options, including safe and more efficient anticancer drugs, has been the aim of many studies.

The use of nano-scale particles in biomedical applications is rapidly growing. Due to the tiny size and large surface area, nanoparticles (NPs) could be easily transported in the body, retained in host tissues, and directed toward the tumor sites (Khan et al. 2019). However, many NPs failed to be used in anticancer chemotherapy due to their high toxicity and low anticancer efficiency (Awasthi et al. 2018). Therefore, a large number of studies focused on the preparation of novel nano compounds with higher anticancer potential and reduced toxicity. Conjugation of metal nanoparticles to various ligands is a novel and promising approach for the preparation of more efficient, stable, and safer compounds to be used against various cancers.

Due to their chemical stability and high biocompatibility, titanium dioxide (TiO2) NPs have received significant interest in being used in biomedical applications (Ai et al. 2017). Previous studies revealed that TiO2 NPs could exert DNA damage in human and animal cells and also induce apoptosis through lipid peroxidation and destabilization of the lysosomal membrane (Cui et al. 2011). In addition, the antitumor potential of TiO2 NPs has been reported via the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Pan et al. 2009; Jin et al. 2008).

Conjugation of TiO2 NPs to different ligands could be used to enhance their antitumor potential, accumulation in the tumor site, and stability of the drug (Cui et al. 2011). Thiosemicarbazones (TSCs) have shown considerable therapeutic potential as antiviral, antibacterial, and anticancer agents (Anjum et al. 2019). Conjugation of TSCs with a variety of NPs has been investigated to increase the stability and anticancer efficacy of the drug (Cui et al. 2011; Hosseinkhah et al. 2021).

In this work, we aimed to prepare TiO2 NPs conjugated to TSC through the functionalization with glutamine and characterize the anticancer mechanism of the synthesized compound in the human liver cancer cell line (HepG2).

Materials and methods

Reagents

All chemicals were of analytical grade, used without further purification, and obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Company. All solutions were prepared with deionized water.

Preparation of TiO2 NPs functionalized by glutamine (TiO2 @Gln)

To prepare TiO2 NPs functionalized by glutamine (TiO2 @Gln), at first, 300 mg of potassium hexafluorotitanate (iv) and 152 mg of glutamine were suspended in 150 mL of distilled water (dH2O). The mixture was heated to 50 °C, and the pH was gradually increased to 11.0 using a NaOH 10% solution (w/v) by stirring. Then, the temperature was increased to 80 °C, and after two hours, the TiO2@Gln nanoparticles were harvested by centrifugation at 6000 RPM for 10 min. The pellet was washed consecutively using dH2O and 96% ethanol and dried at 70 °C for eight hours in an oven (UN110 model, Memmert Company, Germany).

To synthesize titanium dioxide NPs functionalized by glutamine, and conjugated with thiosemicarbazone (TiO2 @Gln-TSC), 500 mg of TiO2@Gln and 200 mg of TSC were suspended in 96% ethanol and sonicated at 40 °C for 45 min. Then, the mixture was shaken (100 RPM) at 40 °C for 24 h, and the synthesized TiO2@Gln-TSC was harvested, washed, and dried, as described above (Nejabatdoust et al. 2019).

Physicochemical features of nanoparticles

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed (Model 6100, Shimadzu, Japan), and the crystalline structure of the TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs was determined (Co-Ka X-radiation, k = 1.79 Å). Also, the Fourier-transform infrared (FT–IR) pattern of TiO2@Gln and TiO2@Gln-TSC was compared using the Nicolet IR 100 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Company, USA) in a range of 500–4000 cm−1. The Zeta potential and particle hydrodynamic size were measured by a zeta sizer instrument (Ver. 6.32, Malvern Instruments company, UK). EDX-mapping was used to investigate the purity of the synthesized TiO2@Gln-TSC by an FE-SEM device (TESCAN MIRA3, Czech Republic). Scanning and transmission electron microscopes (SEM and TEM) were used to evaluate the morphology, size range, and aggregation level of the particles (TESCAN MIRA3 FE-SEM, Czech Republic and Zeiss-EM10C-100 kV TEM, Germany).

Cytotoxicity analysis

Cytotoxicity of TiO2@Gln-TSC toward human liver cancer cells (HepG2) and normal human cells (HEK293) was investigated. Cisplatin was also used as an approved anticancer drug against HepG2 cells. After the preparation of cell monolayers in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), the cells were sub-cultured in 96-well plates. Then they were treated with different concentrations of TiO2@Gln-TSC or Cisplatin (15.6–500 µg/mL) for 24 h. Then, MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) was added to the wells, incubated for four hours and the medium was replaced with 200 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The plates were shaken for 30 min, and the OD590 of the wells was measured (Bio-Rad microplate reader, Hercules, CA, USA). Finally, the 50% inhibitory concentration of each agent was calculated as follows (Zhao et al. 2017):

| 1 |

Flow cytometry analysis

Cell cycle analysis of TiO2@Gln-TSC treated and untreated HepG2 cells was performed using a flow cytometry assay. The cells were prepared in 6-well plates and incubated with TiO2@Gln-TSC for 24 h, while control cells were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, the cells were harvested, fixed using cold ethanol, stained with propidium iodide, and treated with RNase A 100 µg/mL. Finally, the DNA content of the cells was quantified by a BD Accuri flow cytometry device (BD Bioscience company, USA).

After treatment with TiO2@Gln-TSC, the population of apoptotic and necrotic HepG2 cells in NPs treatment and control groups was also compared. After treating the cells with the NPs or PBS for 24 h, the cells were washed and stained with propidium iodide, and Annexin V (Roche, Germany) and the population of apoptotic cells in NPs treated and untreated cells was determined using flow cytometry analysis (BD Accuri model, BD Bioscience company, USA).

Hoechst staining

To determine the nuclear damage, the HepG2 cells were treated with TiO2@Gln-TSC for 24 h, while control cells were treated with PBS. After incubation, the cells were stained with the Hoechst 33258 solution for 5 min. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and examined under a fluorescent microscope (Hosseinkhah et al. 2021).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 16.0. Significant differences were evaluated using the one-way ANOVA analysis and the p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Physicochemical properties of TiO2@Gln-TSC

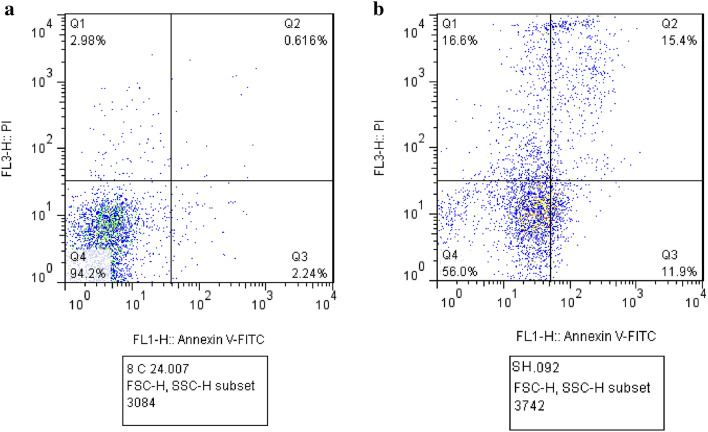

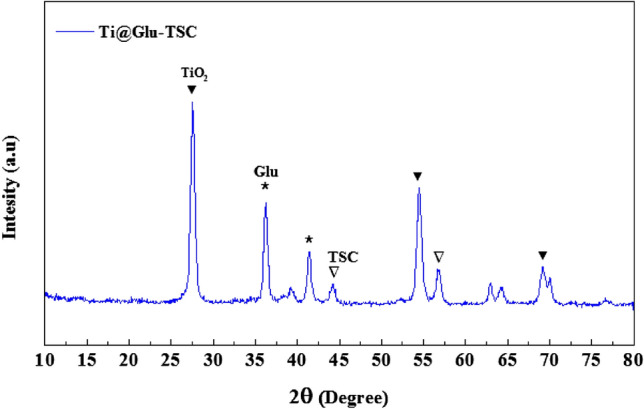

The XRD pattern showed reflection peaks at 2θ of 28, 54, and 68° correspond to TiO2 NPs at the anatase phase and comply with the JCPD number 1764-01073 (Al-Taweel and Saud 2016). Also, the peaks at 2θ of 36 and 41° are related to the glutamine molecules (González et al. 2018). Finally, the peaks at 2θ of 45 and 70° suggest the presence of amorphic TSC molecules (Yang et al. 2018). Figure 1 displays the XRD pattern of TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs.

Fig. 1.

XRD pattern of the synthesized TiO2@Gln-TSC. The peaks associated with the presence of each component were shown by symbols

FT-IR analysis (Fig. 2) was performed to compare the functional groups of TiO2, Gln, TSC, TiO2@Gln, and TiO2@Gln-TSC. In the spectrum related to Gln, the peaks in wavenumber between 500 cm−1 and 2000 cm−1 are related to the C–C, C–O, C–H, C=O, and N–H bonds, and also, the 2641 cm−1 peak is related to the C–N and 3421 cm−1 is related to O–H stretching bond (Sheela et al. 2017).

Fig. 2.

FT-IR spectra of Gln, TiO2, TSC, TiO2@Gln, and TiO2@Gln-TSC. The functional groups associated with different components could be observed in the respecting spectrogram

In the spectrum related to the TiO2 NP, the presence of a peak at wavenumber 763.3 cm−1 confirms the existence of a metal bond between Ti–O (León et al. 2017).

In the spectrum related to TSC, peaks 657 cm−1 and 798 cm−1 correspond to C–H and N–H bonds, and the peaks at 1008, 1166, and 1538 cm−1 correspond to C–H, C=S, and N–H bonds, respectively. Also, the peak at 1642 cm−1 is related to the C-N bond, and the peaks in the range between 3000 and 4000 cm−1 are related to the O–H bond (Jarestan et al. 2020).

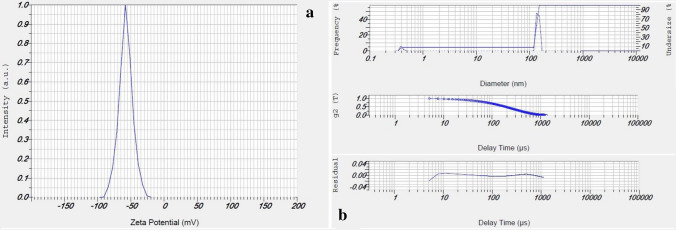

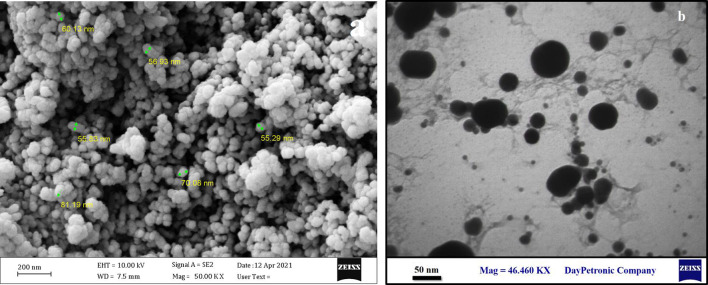

The FT-IR spectra of TiO2@Gln revealed two peaks at 427 and 535 cm−1 that are associated with the Ti–O bond. Moreover, the peaks at 837.8 and 1387 cm−1 correspond to the C–H and C=O bonds, respectively. In addition, the peaks at 1607 and 3634 cm−1 contributed to the N–H and 0–H stretching bonds of glutamine. In contrast, the FT-IR spectrogram of TiO2@Gln-TSC had two peaks at 430.96 and 535.03 cm−1, corresponding to the Ti–O bond. Moreover, the peaks at 837.6, 1339.2, and 1389.9 cm−1 are associated with the C–H, C=S, and C–N bonds. Also, two bonds observed at 1607.1 and 1955.2 cm−1 that are associated with N=O and C=N bonds, respectively. Finally, the peaks that were observed in the range of 3000 to 4000 cm−1 may result from the O–H bond (Ustunol et al. 2019). The zeta potential and hydrodynamic size (Fig. 3) of TiO2@Gln-TSC were − 57.8 mV and 127 nm, respectively. The SEM and TEM analyses (Fig. 4) revealed that the TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs were spherical, with low aggregation, and also with a size range of 10–80 nm.

Fig. 3.

Zeta potential (a) and DLS (b) analyses of the synthesized TiO2@Gln-TSC. The zeta potential of the NPs was − 57.8 mV which shows suitable repulsive force between the particles. The hydrodynamic size of the particles was 127 nm

Fig. 4.

Electron microscopy imaging of the synthesized TiO2@Gln-TSC. (a) SEM, (b) TEM. The Particles were spherical with low aggregation and with a size range of 10–80 nm

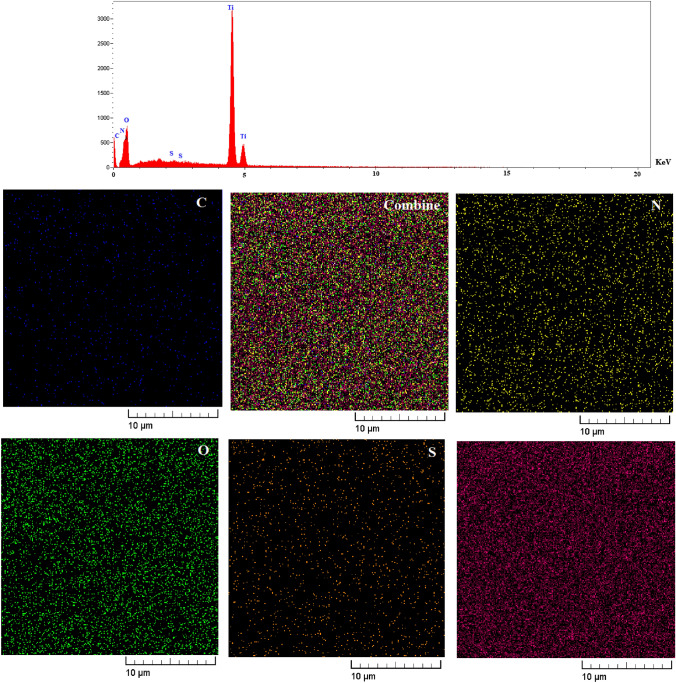

The purity of synthesized TiO2@Gln-TSC was investigated by EDX-mapping (Fig. 4) analysis. The results confirmed the purity of the particles. The elemental composition of TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs includes C, N, O, S, and Ti.

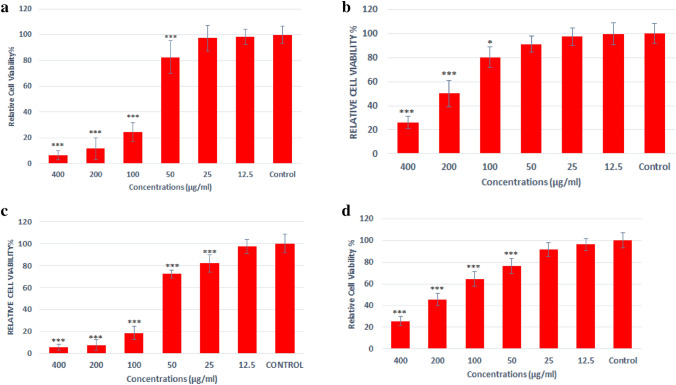

Cytotoxicity for HepG2 and HEK293 cells

The MTT assay (Fig. 5) was used to evaluate the toxicity of different concentrations of TiO2@Gln-TSC for human liver cancer cells (HepG2) and human normal HEK293 cells. Cisplatin was also used as the positive control. Also, the cytotoxicity of TiO2 NPs was evaluated alone. We found that at concentrations greater than 50 µg/mL, TiO2@Gln-TSC significantly decreased the survival of HepG2 cells. Although the cytotoxicity was dose-dependent, at 100 µg/mL and more, the survival of HepG2 cells dramatically reduced. The IC50 of TiO2@Gln-TSC and TiO2 NPs for HepG2 cells were 75 µg/mL and 161 µg/mL, respectively, while the IC50 of Cisplatin was 65 µg/mL. Evaluation of the cytotoxic effect of TiO2@Gln-TSC showed that at concentrations greater than 125 µg/mL, the survival of HEK293 cells was significantly reduced, and the IC50 was calculated 210 µg/mL.

Fig. 5.

EDS-mapping of the synthesized TiO2@Gln-TSC. The synthesized NPs contained C, N, S, O, and Ti atoms, and no elemental impurity was found

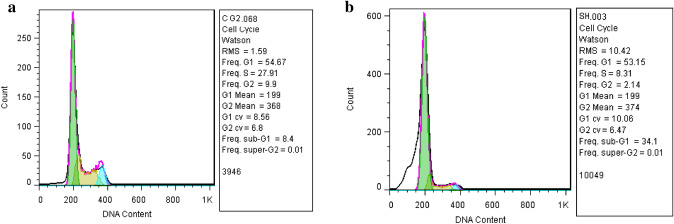

Flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of treating with TiO2@Gln-TSC on the frequency of apoptotic cells in HepG2 cells. The results (Fig. 6) revealed that after treatment with the NPs, 15.4 and 11.9% of HepG2 cells had primary and late apoptosis, respectively. Moreover, the frequency of necrotic cells in NPs treated cells was 16.6%. In contrast, the flow cytometry analysis showed that the frequency of the cells with primary and late apoptosis was 0.6 and 2.24% in the control group, respectively. The results were displayed in Fig. 7.

Fig. 6.

Viability of HepG2 (a) and HEK293 (b) cells after treating with TiO2@Gln-TSC. (c) Viability of HepG2 cells after treatment with Cisplatin and (d) Viability of HepG2 cells after treatment with TiO2 NPs (n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). At concentrations greater than 50 µg/mL, TiO2@Gln-TSC significantly decreased the survival of HepG2 cells in a dose-dependent manner. The IC50 of TiO2@Gln-TSC and TiO2 NPs for HepG2 cells were 75 µg/mL and 161 µg/mL respectively, while the IC50 of Cisplatin was 65 µg/mL. At concentrations greater than 125 µg/mL, the survival of HEK293 cells was significantly reduced and the IC50 was calculated 210 µg/mL

Fig. 7.

Flow cytometry analysis of HepG2 cells. a Control, b TiO2@Gln-TSC treatment. Q1–Q4 represents cell necrosis, primary apoptosis, late apoptosis, and viable cells. Treating with the NPs, caused 15.4, 11.9%, and 16.6% of primary and late apoptosis, and cell necrosis, respectively which are considerably greater than control cells

Cell cycle analysis of TiO2@Gln-TSC treated and control cells (Fig. 8) was also performed using flow cytometry analysis. The results showed that only 8.4% of control cells were at the sub-G1 phase, while 34.1% of HepG2 cells were arrested after treatment with the NPs, which was significantly higher than the control group.

Fig. 8.

Cell cycle analysis of a Control and b TiO@Gln-TSC treated HepG2 cells. The frequency of the cells arrested at the sub-G1 cycle significantly increased to 34.1% following exposure to the NPs

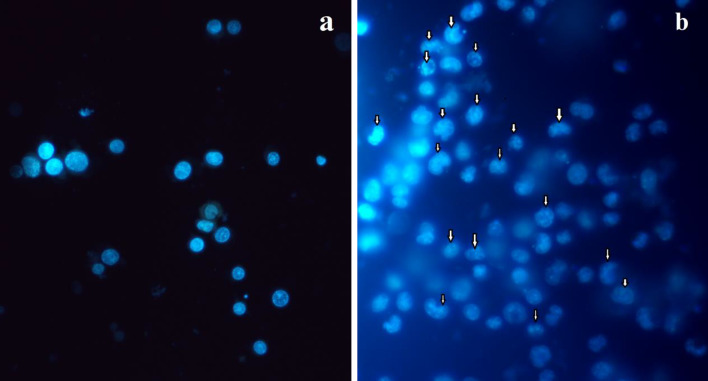

Hoechst staining

Evaluation of the nuclear damages in TiO2@Gln-TSC treated HepG2 cells (Fig. 9) revealed apparent nuclear damage and apoptotic features. The main observed characteristics include chromatin condensation and fragmentation. Also, apoptotic bodies were observed in the NPs treated cells. In contrast, no noticable nuclear changes were found in the control group.

Fig. 9.

Hoechst staining of a Control and b TiO2@Gln-TSC treated HepG2 cells. Apoptotic morphological features, including, chromatin condensation and fragmentation and the presence of apoptotic bodies could be observed in NPs treated cells

Discussion

Thiosemicarbazide complexes have shown promising anticancer potentials for treating a variety of cancer cells. Many metals ion and TSC complexes have been designed to improve the anticancer potential and stability of metal NPs (Palanimuthu et al. 2013; Afrasiabi et al. 2004; Padhye et al. 2005). However, low efficacy and undesirable toxicity are regarded as the major limitations of these compounds for anticancer chemotherapy. Due to their great biocompatibility and low toxicity, titanium oxide NPs have gained interest in biomedical applications. Many studies focused on increasing the stability and efficacy of titanium via the conjugation of the NPs to different compounds. Therefore, the current work was performed to prepare TiO2 NPs conjugated with TSC and characterize their cytotoxic mechanism in liver cancer cells.

Physiochemical characterization of TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs revealed the proper synthesis of the complex. The electron microscopy analyses confirmed the nano-scale size and low aggregation level of the NPs. Moreover, the zeta potential of the NPs was − 57.8 mV, which indicates the good stability and low aggregation of the particles. Also, the purity of the NPs was confirmed by EDX-mapping analyses.

The IC50 value of the NPs for the HepG2 and HEK293 cells was 75 and 210 µg/mL, respectively. Therefore, our results showed that the fabricated NPs were significantly more toxic for cancer cells than normal cells. Also, the IC50 of Cisplatin, as a standard anticancer drug, for HepG2 cells was 65 µg/mL, which indicates the promising anticancer potential of the TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs. The cytotoxicity of TiO2@Gln-TSC contributes to both metal ions and TSC components of the fabricated complex. Similar to other metal NPs, the cytotoxic effect of TiO2 is mainly related to the generation of radical oxygen species (ROS) (Hosseinkhah et al. 2021). The generation of oxidative stress is considered the most important antiproliferative mechanism of titanium NPs. Upon production of ROS, a large number of normal cellular functions, including metabolic pathways, DNA replication, and gene expression, are interrupted. Moreover, the generated ROS could damage cellular components, especially cytoplasmic membrane and nucleic acids (Vandamme et al. 2012).

Previous studies reported the cytotoxic potential of TSC derivatives. It was reported that TSC derivatives could inhibit the activity of the enzymes responsible for cell proliferation and DNA replication, including DNA topoisomerases. In addition, the inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase, the enzyme responsible for synthesizing of deoxyribonucleotides, by TSC complexes has been reported (Zaltariov et al. 2017; Zeglis et al. 2011). It was reported that copper and TSC complex could strongly inhibit cellular ribonucleotide reductase, which results in the failure of DNA synthesis. Overall, it could be suggested that the inhibition of cell proliferation is the primary cytotoxicity mechanism of TSC complexes.

We found that the cancer cells were significantly more susceptible to TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs than normal human cells. The higher susceptibility of cancer cells could be related to their higher metabolic and proliferation rate than normal cells. Generally, the continuous and fast proliferation of cancer cells results in the higher permeability of the cell membrane to increase the uptake of nutrients (Kettler et al. 2014). The increased permeability of the cell membrane could cause increased drug uptake and accumulation in the cytoplasm, where TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs could interrupt normal cellular functions.

Compared with the non-cancerous cells, the higher susceptibility of cancer cells to TiO2@Gln-TSC could also be associated with the presence of Glutamine in the formulation of the NPs. Glutamine is an important amino acid that plays essential roles in cell proliferation, such as a nitrogen and carbon donor, and amino acid precursor (Yoo et al. 2020). Due to its versatile usage in cell proliferation, glutamine-containing drugs could be prepared to increase the penetration and susceptibility of cancer cells to anticancer compounds. Moreover, cancer cells have a higher proliferation rate and so higher metabolic rate than normal cells, which results in a high nutrient demand (Papalazarou and Maddocks 2021). In our work, Glutamine was used to functionalize TiO2 NPs to enhance their conjugation with TSC molecules. Considering this, glutamine not only participates in forming the structure of NPs but can also play a role as a substrate for cancer cells. Therefore, the high susceptibility of cancer cells to TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs may be associated with their dependence on Glutamine for cell reproduction.

The size of NPs usually increases in in-vivo conditions due to the adsorption of organic molecules, such as proteins, on the particle surface. Achieving complete nanoparticle (NP) clearance is a critical consideration in the design of safe nanomedicines. Due to their large size (> 5.5 nm), renal clearance of complex metal NPs is not possible, which raises concerns in this regard (Zhu et al. 2022). However, studies represented fecal elimination through the hepatobiliary route as the primary route for NP clearance (Poon et al. 2019). These findings have alleviated concerns about the therapeutic use of nanoparticles, although studies, especially in vivo, seem necessary.

Flow cytometry analysis of TiO2@Gln-TSC treated and control cells revealed that apoptosis induction was the significant outcome of the exposure of HepG2 cells to the NPs. Our results showed that apoptosis was induced in 27.3% of TiO2@Gln-TSC treated cells, while only 2.8% of control cells showed apoptosis. In addition, the cell cycle analysis showed that 34.1% of NPs treated cells were arrested at the sub-G1 cycle, favoring apoptosis induction in the treated cells. As described above, inhibition of DNA replication, and DNA damage could interrupt normal cell proliferation. We found a significantly increased level of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in TiO2@Gln-TSC treated cells. Therefore, apoptosis induction could be considered a significant outcome of the exposure of the studied cells to the synthesized complex. In agreement with this finding, we found nuclear damages, including chromatin fragmentation, and the appearance of apoptotic bodies, which indicated the apoptosis induction in NPs treated cells.

Conclusion

In this work, TiO2@Gln-TSC NPs were synthesized, and their cytotoxic effect on liver cancer cells was characterized. We found that TiO2@Gln-TSC is a potent anticancer agent with an IC50 value close to Cisplatin. Also, the liver cancer cells showed higher susceptibility to the NPs than normal human cells. Finally, nuclear damage, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis induction were found as the significant outcome of the exposure to TiO2@Gln-TSC in HepG2 cells.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: SSS, HH, and AS; Methodology: HH; formal analysis and investigation: SSS, and AS; writing original draft preparation: SSS, and HH; editing: HHNR, and AS; resources: SSS; supervision: NR, HH, and AS.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval statement

Not applicable.

Patient consent statement

Not applicable.

Clinical trial registration

Not applicable.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not applicable.

References

- Afrasiabi Z, Sinn E, Chen J, Ma Y, Rheingold AL, Zakharov LN, Padhye S. Appended 1, 2-naphthoquinones as anticancer agents 1: synthesis, structural, spectral and antitumor activities of ortho-naphthaquinone thiosemicarbazone and its transition metal complexes. Inorgan Chim Acta. 2004;357(1):271–278. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1693(03)00484-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ai JW, Liu B, Liu WD. Folic acid-tagged titanium dioxide nanoparticles for enhanced anticancer effect in osteosarcoma cells. Mater Sci Eng C. 2017;76:1181–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Taweel SS, Saud HR. New route for synthesis of pure anatase TiO2 nanoparticles via utrasound-assisted sol–gel method. J Chem Pharm Res. 2016;8(2):620–626. [Google Scholar]

- Anjum R, Palanimuthu D, Kalinowski DS, Lewis W, Park KC, Kovacevic Z, Richardson DR. Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro anticancer activity of copper and zinc bis (thiosemicarbazone) complexes. Inorg Chem. 2019;58(20):13709–13723. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b01281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi R, Roseblade A, Hansbro PM, Rathbone MJ, Dua K, Bebawy M. Nanoparticles in cancer treatment: opportunities and obstacles. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(14):1696–1709. doi: 10.2174/1389450119666180326122831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Liu H, Zhou M, Duan Y, Li N, Gong X, Hong F. Signaling pathway of inflammatory responses in the mouse liver caused by TiO2 nanoparticles. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;96(1):221–229. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González VJ, Rodríguez AM, León V, Frontiñán-Rubio J, Fierro JLG, Durán-Prado M, Vázquez E. Sweet graphene: exfoliation of graphite and preparation of glucose-graphene cocrystals through mechanochemical treatments. Green Chem. 2018;20(15):3581–3592. doi: 10.1039/C8GC01162A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinkhah M, Ghasemian R, Shokrollahi F, Mojdehi SR, Noveiri MJS, Hedayati M, Salehzadeh A. Cytotoxic potential of nickel oxide nanoparticles functionalized with glutamic acid and conjugated with thiosemicarbazide (NiO@ Glu/TSC) against human gastric cancer cells. J Clust Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10876-021-02124-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarestan M, Khalatbari K, Pouraei A, Sadat Shandiz SA, Beigi S, Hedayati M, Majlesi A, Akbari F, Salehzadeh A. Preparation, characterization, and anticancer efficacy of novel cobalt oxide nanoparticles conjugated with thiosemicarbazide. 3 Biotech. 2020;10:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-02230-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin CY, Zhu BS, Wang XF, Lu QH. Cytotoxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mouse fibroblast cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21(9):1871–1877. doi: 10.1021/tx800179f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettler K, Veltman K, Van de Meent D, Van Wezel A, Hendriks AJ. Cellular uptake of nanoparticles as determined by particle properties, experimental conditions, and cell type. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2014;33(3):481–492. doi: 10.1002/etc.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Ansari AA, Malik A, Chaudhary AA, Syed JB, Khan AA. Preparation, characterizations and in vitro cytotoxic activity of nickel oxide nanoparticles on HT-29 and SW620 colon cancer cell lines. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2019;52:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León A, Reuquen P, Garín C, Segura R, Vargas P, Zapata P, Orihuela PA. FTIR and Raman characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles coated with polyethylene glycol as carrier for 2-methoxyestradiol. Appl Sci. 2017;7(1):49. doi: 10.3390/app7010049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- London WT, McGlynn KA. Liver cancer. 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 635–660. [Google Scholar]

- Nejabatdoust A, Zamani H, Salehzadeh A. Functionalization of ZnO nanoparticles by glutamic acid and conjugation with thiosemicarbazide alters expression of efflux pump genes in multiple drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Microb Drug Resist. 2019;25(7):966–974. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padhye S, Afrasiabi Z, Sinn E, Fok J, Mehta K, Rath N. Antitumor metallothiosemicarbazonates: structure and antitumor activity of palladium complex of phenanthrenequinone thiosemicarbazone. Inorg Chem. 2005;44(5):1154–1156. doi: 10.1021/ic048214v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanimuthu D, Shinde SV, Somasundaram K, Samuelson AG. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of copper bis (thiosemicarbazone) complexes. J Med Chem. 2013;56(3):722–734. doi: 10.1021/jm300938r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Lee W, Slutsky L, Clark RA, Pernodet N, Rafailovich MH. Adverse effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on human dermal fibroblasts and how to protect cells. Small. 2009;5(4):511–520. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papalazarou V, Maddocks OD. Supply and demand: cellular nutrient uptake and exchange in cancer. Mol Cell. 2021;81(18):3731–3748. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon W, Zhang YN, Ouyang B, Kingston BR, Wu JL, Wilhelm S, Chan WC. Elimination pathways of nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2019;13(5):5785–5798. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b01383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheela GE, Manimaran D, Joe IH, Jothy VB. Studies on molecular structure and vibrational spectra of NLO crystal l-glutamine oxalate by DFT method. Indian J Sci Technol. 2017;10(31):1–23. doi: 10.17485/ijst/2017/v10i31/114486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustunol IB, Gonzalez-Pech NI, Grassian VH. pH-dependent adsorption of α-amino acids, lysine, glutamic acid, serine and glycine, on TiO2 nanoparticle surfaces. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;554:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme M, Robert E, Lerondel S, Sarron V, Ries D, Dozias S, Pape AL. ROS implication in a new antitumor strategy based on non-thermal plasma. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(9):2185–2194. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Jin Q, Xu C, Fan S, Wang C, Xie P. Synthesis, characterization and antifungal activity of coumarin-functionalized chitosan derivatives. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;106:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Yu YC, Sung Y, Han JM. Glutamine reliance in cell metabolism. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(9):1496–1516. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00504-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaltariov MF, Hammerstad M, Arabshahi HJ, Jovanovic K, Richter KW, Cazacu M, Arion VB. New iminodiacetate–thiosemicarbazone hybrids and their copper (II) complexes are potential ribonucleotide reductase R2 inhibitors with high antiproliferative activity. Inorg Chem. 2017;56(6):3532–3549. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b03178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeglis BM, Divilov V, Lewis JS. Role of metalation in the topoisomerase IIα inhibition and antiproliferation activity of a series of α-heterocyclic-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazones and their Cu (II) complexes. J Med Chem. 2011;54(7):2391–2398. doi: 10.1021/jm101532u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Guo C, Wang L, Wang S, Li X, Jiang B, Shi D. A novel fluorinated thiosemicarbazone derivative-2-(3, 4-difluorobenzylidene) hydrazinecarbothioamide induces apoptosis in human A549 lung cancer cells via ROS-mediated mitochondria-dependent pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;491(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu GH, Gray AB, Patra HK. Nanomedicine: controlling nanoparticle clearance for translational success. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2022.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.